Abstract

Background

Resilience research has gained increased scientific interest and political currency over the last ten years.

Objective

To set this volume in the wider context of scholarly debate conducted in previous special theme issue and/or special section publications of refereed journals on resilience and related concepts (1998–2008).

Method

Peer reviewed journals of health, social, behavioral, and environmental sciences were searched systematically for articles on resilience and/or related themes published as a set. Non-English language publications were included, while those involving non-human subjects were excluded.

Results

A total of fifteen journal special issues and/or special sections (including a debate and a roundtable discussion) on resilience and/or related themes were retrieved and examined with the aim of teasing out salient points of direct relevance to African social policy and health care systems. Viewed chronologically, this series of public discussions and debates charts a progressive paradigm shift from the pathogenic perspectives on risk and vulnerability to a clear turn of attention to health-centered approaches to building resilience to disasters and preventing vulnerability to disease, social dysfunction, human and environmental resource depletion.

Conclusion

Resilience is a dynamic and multi-dimensional process of adaptation to adverse and/or turbulent changes in human, institutional, and ecological systems across scales, and thus requires a composite, multi-faceted Resilience Index (RI), in order to be meaningfully gauged. Collaborative links between interdisciplinary research institutions, policy makers and practitioners involved in promoting sustainable social and health care systems are called for, particularly in Africa.

Keywords: Adaptive learning, Disaster mitigation, Human resilience, Resilience Index, Social-ecological resilience, sustainability of human and natural resource management systems

Introduction

An overview of recent developments and current direction of international research and policy discourse on resilience is presented here with the aim of setting this volume in the wider context of ongoing discussion and debate among scholars, policy makers, and practitioners.

Method

Multiple systematic searches were conducted to identify peer-reviewed journal articles published as sets belonging to special theme issue volumes and/or special sections of journal volumes on resilience and related terms in the human, social, behavioral, and environmental sciences. No limits were set on languages or dates of publication, but those reporting on nonhuman subjects were excluded.

Results and Discussion

Fifteen journal special issues and/or special sections on resilience and/or related themes published over the last ten years were found and reviewed with a view to summarizing their salient points of direct relevance to African health care and social systems. All of these discussions and debates were conducted in the English language.1–15 The analysis yielded a rich body of knowledge and shared insights among seemingly unrelated scholars and practitioners who have considered the concept of resilience from a wide range of perspectives, often with divergent aims and objectives stemming from their own individual/independent research and/or policy/practice priorities.

The majority of these scholarly discussions and debates demonstrate a concerted move away from the usual emotional/mental distress and trauma-focused psychopathology to a positive psychology of human strengths, encapsulated by the term resilience in its multi-faceted forms (see Table). During the second half of the 1990s, galvanized by the imminent close of the 20th century, psychologists and others had decided to take stoke and re-think prevailing assumptions and claims on the nature of the human capacity to adapt, and even thrive and/or grow in the face of adversity of different types and levels of magnitude. Viewed chronologically, this series of public discussions and debates charts a progressive paradigm shift from the disease-driven inquiries on risk and vulnerability to a clear turn of attention towards health-centered approaches to building resilience to disasters and preventing vulnerability to disease, social dysfunction, human and environmental resource depletion.

Table.

Public discussion and debate in journal special issue volumes or sections on resilience and related themes (1998–2008)

| Journal (year) Title, Volume (pages) — Editor/s and Salient points of direct relevance to current African health research, policy, and practice (Ref) |

|

The Journal of Social Issues (1998, Vol. 54) put the topic of “Thriving” on the spotlight. At that time, the notion of post-traumatic growth (PTG) came as a refreshing change of subject from the then highly controversial diagnostic category of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), particularly with respect to humanitarian policy and practice in non-western settings.16, 17 Although the post-traumatic growth inventory, PTGI, was originally developed and tested among American college students, and not disaster-affected communities, it was later successfully employed in a study of displaced people in Sarajevo, exploring the dynamic process of transformation and growth following recovery from the trauma of the Balkan war.18 Karakashian's interdisciplinary analysis of the historical, geo-political, social and cultural dimensions of human resilience in Armenia, a small nation that had experienced collective trauma of genocidal proportions was featured in this volume; presenting interesting parallels with Almedom et al.'s study of human resilience in Eritrea (featured in discussion # 9, Table), another small country for whom human and institutional resilience, particularly in the extraordinary levels of adaptive learning and transformations that took place within the self-organized systems health care, education, and social affairs under prolonged conditions of war and displacement.19

The new millennium was ushered in with the publication of special issues of both the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology (2000, Vol. 19) and American Psychologist (2000, Vol. 55) focusing respectively on human strength and positive psychology. These took the discussion on the nature of resilience a step forward by arguing that it is in fact not the (rare) phenomenon it was assumed to be, but in fact resilience is quite common, an “Ordinary Magic”. Between them, these two volumes explained the mechanisms whereby human resilience was demonstrated by self-control and mature adaptive defenses; and clarified the concept of hope as long-term goal-driven agency and pathways; a state of “realistic optimism” as perhaps more tangible than “positive illusions” or “unrealistic optimism” among those with life-threatening disease.

Views of resilience as an outcome identified by the absence of PTSD were challenged as simplistic and even misleading as the process of coping with trauma did not in fact preclude the experience of distress and narrative of trauma. As the debate continued in later issues of the American Psychologist (2001, Vol. 56; and 2005, Vol. 60), it became clearer that experiences of trauma and growth (vulnerability and resilience) were part and parcel of the same psychological dynamics of human adaptation to turbulent change, two sides of the same coin, as it were. Interestingly, the most recent systematic review, a meta-analysis of the question of acute distress and PTSD with reference to the response of Londoners to the bombings of July 7th 2005 came to the conclusion that “distress — a perfectly understandable reaction to a traumatic event — and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” should not be lumped together and medicalized… “Resilience is not about avoiding short-term distress — indeed resilient people include those who show their distress… “Resilient people may experience a period of distress and then recover with the support of their families and friends.”20

Most helpfully, The Journal of Clinical Psychology (2002, Vol. 58) provided the most comprehensive and clearly articulated set of articles on human (developmental) resilience with reference to children, youth, and families as social systems. As Richardson explained, the paradigm shift from pathogenic to salutogenic thinking had happened in three waves: Resilience as a phenomenon; resilience as a process; and resilience as the energy and motivation to re-integrate. These may conveniently be summed up as the three ‘P’s: a phenomenon, a process and the power (of re-integrating) that resilient children, youth, and families demonstrate. It is interesting to note that this third wave resonates with the resilience thinking in social-ecological terms as well.21

These discussions and debates were clearly accelerated by recent international political, social and economic concerns and priorities to promote, build, and maintain resilience at all levels — as we are faced with global threats to the health, social, economic, environmental, and geo-political sustainability of human lives and livelihoods. The practice-oriented journal Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention (2002, Vol. 2) focused on what happened after the terrorist attacks of September 11th 2001 in New York City and in Boston. It became evident that the traditional forms of mental health services had adapted to the changed climate of positive psychology to the extent that competence-based (rather than pathology-based) approaches were promoted. The argument for tailoring mental health services to prevent the worst outcomes by enhancing systems of social support was put forward.

Meanwhile, the Journal of Biosocial Science (2004,Vol. 36) published a special issue on mental well being in settings of ‘complex emergency’ following a panel discussion held at the Society for Applied Anthropology's Annual Meetings in Portland, Oregon, the previous year. As the panel discussion was held on the day after the Iraq war began (March 20, 2003) questions on the levels of PTSD to be expected and the relevance of mental health services with reference to counseling and talk therapy; the uses and limits of psychometric scales for the assessment of metal well-being in the context of protracted conflict and/or post-conflict settings; the role of social support in promoting positive aftermath in the process of psychosocial transition in displaced families and communities were debated from the perspectives of anthropology, sociology, and medical/clinical practice. The theoretical and empirical (qualitative) ground work was laid for measuring resilience in settings of complex emergency using the sense of coherence scale short-form (SOC-13) adapted for use in nine African languages.22

In the same year, the practitioner-focused journal Psychiatric Clinics of North America (2004, Vol. 27), and Substance Use & Misuse (2004, Vol. 39) also dedicated special issues respectively on disaster psychiatry and resilience. Again, evidence of the global paradigm shift was growing in previously seemingly unrelated fields as researchers, practitioners and policy makers continued to take a fresh look with a long-term approach to solving problems in the new millennium. This development was echoed in the World Health Organization's Round Table discussion published the following year in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization (2005, Vol. 83). Since then, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), a committee of executive heads of United Nations agencies, intergovernmental organizations, Red Cross and Red Crescent agencies and consortia of nongovernmental organizations responsible for global humanitarian policy established in response to United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/182, has developed guidelines for coordination of mental health and psychosocial support in emergencies. The guidelines were agreed and commended for adoption by all the parties concerned.23

Finally, the last two years have seen increased visibility of the Resilience Alliance's public scientific discourse on resilience documented in the form of a special issue and a special theme section of the two leading academic research journals, respectively Global Environmental Change (2006, Vol. 16) and Ecology and Society (2008, Vol. 13). The former has brought to the fore the equal relevance of human and natural systems in the dynamics of adaptation and social-ecological resilience as a basis for sustainability, while the latter has focused on disaster management with reference to ‘surprises’ of environmental and public health consequence, particularly with reference to human security.

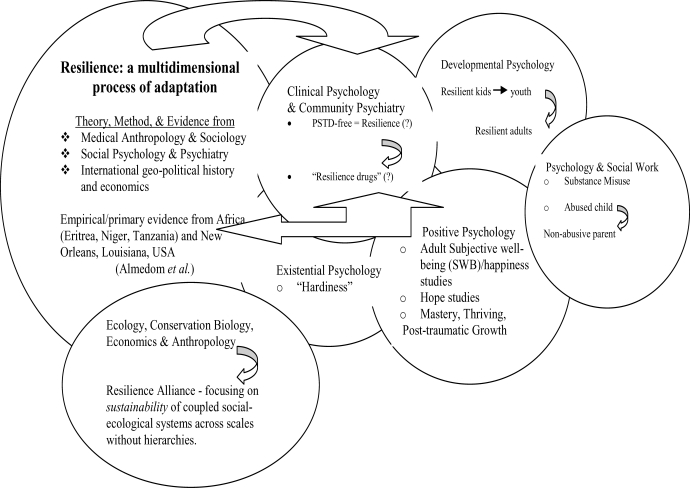

The linkages forged between the interdisciplinary research undertaken by Almedom et al, and disaster mental health research and practice, as well as the core elements of developmental, positive, and existential sub-disciplines of psychology; medicine/psychiatry; and last but not least resilience science founded in ecology and environmental studies are depicted in the above Figure. Some of these circles embrace more ambiguity and/or paucity of data than others. For example, while there is no shortage of studies in clinical psychology and community medicine/ psychiatry using PTSD or absence thereof as a measure of resilience, the development of psychotropic medication, “resilience drugs” designed to alleviate symptoms of acute distress in the aftermath of crises remains a cause for concern24 and may continue to perpetuate ambiguity in international mental health policy and practice. While it may be justifiable for medical practitioners to prescribe pharmaceutical remedies for those experiencing what may be normal levels of acute distress in the immediate aftermath of crisis, such practice may inhibit normal processes of re-integration and growth. Dependence on medication may militate against resilience building sustainable solutions, particularly in African countries, which continue to face rapid depletion of their human and material resources, rendering their systems of health and social care less than viable. Conversely, the multi-disciplinary fields of ecology, conservation biology and development economics and anthropology seem to have clear theoretical grounds on which to proceed with assessing social-ecological resilience, but there remains paucity of data. The Resilience Alliance's Resilience Assessment Work Books which are currently being field-tested may soon generate the data awaited by policy makers and practitioners seeking sustainable solutions to mitigate if not reverse the threats of climate change and rapid depletion of non-renewable resources coupled with ill governance and lack of accountability in the management of human resources.25 This is painfully relevant to African communities, scholars, and health care practitioners whose trained and qualified young health workers continue to be attracted to jobs in western health care services upon graduation from highly respected African institutions such as Makerere University Medical School.

Figure.

An interdisciplinary overview of resilience research in the interface between disaster mitigation/response, human development, sustainability of social-ecological systems, and human security.

Resilience thinking would be expected to reverse this tide by first changing the mindset of both western governments as well as non-governmental institutions which are already undergoing economic and political transitions that present real opportunities for adaptive learning. Collaborative efforts of both western and African policy makers can result in mutual gains in the long term if active measures are taken now to retain African health professionals in African systems of social and health care. However, this cannot be done by individual countries' independent efforts, unless the “International Community” of leaders and policy makers also re-think the terms of engagement with African countries and their natural and human resources.

Finally, it is important to note here that an increasing number of popular books and agency reports have also advanced our understanding of resilience by generating public discussion and debate through mass media channels.26–30 These are also timely and relevant to African health and social care systems analysis in its global context and are examined in a forthcoming publication.

Conclusion

Resilience is a dynamic and multi-dimensional process of adaptation to adverse and/or turbulent changes in human, institutional, and ecological systems across scales, and thus requires a composite, multi-faceted Resilience Index (RI), in order to be meaningfully gauged. Collaborative links between interdisciplinary research institutions, policy makers and practitioners involved in promoting sustainable social and health care systems are called for, particularly in Africa.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Bob Sternberg (former President of the American Psychological Association) and Nick Stockton (Executive Director of Humanitarian Accountability Partnership-International) for their constructive comments and suggestions on earlier draft portions of her analyses. Thanks also to the Henry R. Luce Foundation (New York) for its support of Tufts University's Program in Science and Humanitarianism 2000–2007.

References

- 1.Ickovics J, Park C, editors. Special Issue. Thriving: Broadening the Paradigm Beyond Illness to Health. Journal of Social Issues. 1998;54:237–425. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCullough M, Snyder CR, editors. Special Issue. Classical Sources of Human Strength: Revisiting an old home and Building a New One. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19:1–160. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin EP, Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M, editors. Special Issue. Positive Psychology. American Psychologist. 2000;55:5–183. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheldon K M, King L, editors. Section on Positive Psychology. American Psychologist. 2001;56:216–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debate in the form of letters/commentaries on Bonanno's article (2004) including author's reply. American Psychologist. 2005;60:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkes G, editor. Special Issue. A Second Generation of Resilience Research. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:229–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts A, editor. Special Issue. Crisis Response, Debriefing, and Intervention in the Aftermath of September 11, 2001. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2002;2:1–104. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts A, editor. Section on Disaster Mental Health. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2004;6:130–170. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almedom A, editor. Special Issue. Mental Well-being in settings of “Complex Emergency”. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2004;36:381–491. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray MJ, editor. Special Issue. Risk and Resiliency Following Trauma and Traumatic Loss. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2004;9:1–111. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz C, Pandya A, editors. Special Issue. Disaster Psychiatry: A Closer Look. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;27:xi–602. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson J, Wiechelt S, editors. Special Issue. Resilience. Substance Use& Misuse. 2004;39:657–854. doi: 10.1081/ja-120034010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Headquarters, Geneva, author. Round Table. Mental and social health during and after acute emergencies: emerging consensus? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83:71–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen M, Ostrom E, editors. Special Issue. Resilience, vulnerability, and adaptation: A cross-cutting theme of the International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change. Global Environmental Change. 2006;16:235–316. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunderson L, Longstaff P, editors. Special Feature on Managing Surprises in Complex Systems: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Resilience. Ecology & Society. 2008:6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summerfield D. A critique of seven assumptions behind psychosocial programmes in war-affected areas. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:1449–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vries F. To make drama out of trauma is fully justified. Lancet. 351:1579–1580. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)11524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell S, Rosner R, Buttolo W, et al. Posttraumatic growth after war: A study of former refugees and displaced persons in Sarajevo. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:71–83. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fekadu Tekeste. The Tenacity and Resilience of Eritrea: 1979–1983. Asmara: Hidri; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams R. Lecture given at the Annual Meeting of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, Imperial College, London, July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson G E. The Metatheory of Resilience and Resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almedom AM, Tesfamichael B, Mohammed Z, Mascie-Taylor N, Alemu Z. Use of ‘Sense of Coherence (SOC)’ scale to measure resilience in Eritrea: Interrogating both the data and the scale. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39:91–107. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005001112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Ommeren M, Wessells M. Inter-agency agreement on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85:821. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.047894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almedom A M, Glandon D. Resilience is not the absence of PTSD anymore than health is the absence of disease. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2007;12:127–143. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Resilience Alliance, author. Resilience Assessment Work Books. 2008. http://resalliance.org/3871.php.

- 26.Walker B, Salt D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flynn S E. America the Vulnerable: How our Government is Failing to Protect us from Terrorism. New York: HarperCollins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flynn S E. On the Edge of Disaster: Rebuilding a Resilient Nation. New York: Random House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westley F, Zimmerman B, Patton M. Getting to Maybe: How the World is Changed. Toronto: Random House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homer-Dixon T. The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity, and the Renewal of Civilization. Toronto: Random House; 2006. [Google Scholar]