Abstract

Background

Findings regarding the influence hemodynamic factors, such as increased arterial blood flow or venous abnormalities, on breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema are mixed. The purpose of this study was to compare segmental arterial blood flow, venous blood return, and blood volumes between breast cancer survivors with treatment-related lymphedema and healthy normal individuals without lymphedema.

Methods and Results

A Tetrapolar High Resolution Impedance Monitor and Cardiotachometer were used to compare segmental arterial blood flow, venous blood return, and blood volumes between breast cancer survivors with treatment-related lymphedema and healthy normal volunteers. Average arterial blood flow in lymphedema-affected arms was higher than that in arms of healthy normal volunteers or in contralateral nonlymphedema affected arms. Time of venous outflow period of blood flow pulse was lower in lymphedema-affected arms than in healthy normal or lymphedema nonaffected arms. Amplitude of the venous component of blood flow pulse signal was lower in lymphedema-affected arms than in healthy or lymphedema nonaffected arms. Index of venular tone was also lower in lymphedema-affected arms than healthy or lymphedema nonaffected arms.

Conclusions

Both arterial and venous components may be altered in the lymphedema-affected arms when compared to healthy normal arms and contralateral arms in the breast cancer survivors.

Introduction

Lymphedema of the arm following breast cancer treatment continues to be a distressing and frequent problem despite an increase in the use of sentinel lymph node procedures and other conservative measures. The development of lymphedema after breast cancer treatment is most likely multifactorial. There is general agreement that events that damage the lymphatic system, such as surgical procedures and radiation therapy, can alter or damage the lymphatic system and reduce lymph transport capacity.1 More controversial, and less understood, is the influence that hemodynamic factors, such as increased arterial blood flow or venous blood return, have on lymphedema development.

Hemodynamics and lymphedema

To-date, examination of hemodynamic factors in breast cancer survivors with lymphedema has primarily compared affected to contralateral nonaffected arms in breast cancer survivors with existing lymphedema2,3 or the arms of breast cancer survivors without lymphedema to those of breast cancer survivors with lymphedema.4 Techniques such as venous occlusion plethysmography,5 strain gauges,6 and color duplex ultrasound2,3 have been used. Most studies have found increased arterial blood flow in swollen arms.2,3,5 Reports on venous flow, however, are not as clear. Venous abnormalities, such as outflow obstruction, have been found in varying percentages of breast cancer survivors with lymphedema. Svennson et al. reported venous obstruction in 57% and venous congestion in an additional 14% of 81 breast cancer survivors studied using color Doppler ultrasound.7 Subsequent work by this same group in healthy volunteers (n = 14) and lymphedema volunteers (n = 22) did not support a significant hemodynamic contribution to lymphedema development.6 Martin and Földi reported venous occlusion in 14.5% of the 48 breast cancer survivors in a study using color duplex ultrasound.3 Another study of breast cancer survivors with (n = 39) and without (n = 16) lymphedema found no venous abnormalities.4

Various physiologically-based explanations for the arterial and venous findings have been postulated. Some of these include: 1) possible increased formation of A–V shunts and capillaries in the skin and muscle increase blood flow;8 2) increased circulatory load on the already impaired outflow system weakens the vascular system over time, causing additional accumulation of fluid in the lymphedema arm;9 4) the loss of vasoconstrictor control due to radiotherapy treatment or the underlying surgery;2 and 5) normal sympathetic neural control and local vasoconstrictor control affected arms, but locally-mediated vasodilator control is impaired in the affected arm.5,10,11 Thus, the findings to-date suggest that further exploration of the hemodynamics of lymphedema is needed.

Blood flow measurement

Venous occlusion plethysmography (VOP), Doppler ultrasound, and electrical bioimpedance2,7,12,13 have all been used as noninvasive methods to measure blood flow in human arms. They generally depend upon either determining the amount of volume change that takes place during venous occlusion or upon measuring the velocity of the blood flowing in discrete vessels. A basic understanding of these measurement techniques is essential to gain an insight into previous studies and the data provided in this article.

Venous occlusion plethysmography (VOP)

During VOP procedures, a venous occlusion cuff is applied to the body segment proximal to the volume measuring device. Venous blood return is obstructed by inflating the cuff to just above the diastolic pressure of the segment, thereby causing blood pooling in the distal segment, but not restricting arterial flow. It is assumed that the volume increase in the segment immediately following cuff inflation is indicative of continued normal arterial blood inflow to the segment. Blood flow is then calculated from the known segmental volume increase that occurs over a given time period. Segmental volume changes during VOP have been measured using displacement of air13 or water,5 Whitney Strain Gauges,12 and the Perometer, an infrared optical sensing device.6

Water or air VOPs have inherent disadvantages.14 The volume of water can vary depending on container and arm size, and impose hydrostatic forces on the tissues that can impede capillary flow into the enclosed segment. Due to its high heat capacity and intimate body contact, water also introduces thermal problems that can alter the responses being studied. The high thermal expansion coefficient of an air-filled system introduces problems of drift. Motion artifacts; occluding cuff configuration and placement, body orientation, and the effects of both the cuff and volume container upon the internal hemodynamics of the segment being studied are also problematic. VOPs are also difficult to use on more than one body segment at the same time (i.e., contralateral arms or legs).

Whitney Strain Gauge techniques do not require the segment being monitored to be sealed in a fluid-filled container.15 When the tube is stretched, the column of mercury is narrowed, changing its electrical resistance in proportion to its increase in length. If the filled tube is placed circumferentially around a given body segment, it is possible to measure the increase in segment girth produced by inflation of the venous cuff placed proximally to the strain gauge. The strain gauge must be free to expand and contract during measurement and the segment being monitored cannot be supported during testing. Limbs must be relaxed and not under muscle tension. Use of the Whitney Strain Gauge eliminates some of the problems encountered when using a fluid-filled plethysmograph; however, mercury is a toxic substance and there are stringent limitations upon its use.

Doppler ultrasound

Doppler techniques2,7 use an ultrasound emitting sensor and receiving transducer to transmit an ultrasonic beam down the central axis of a blood vessel or artery. The sonic signal is reflected by the blood cells flowing away from the sensor. The transmission time between the emitted and reflected signal can be used to determine the velocity of the flowing blood. Dual beam ultrasonic measurements can be made to measure both blood flow velocity and the cross-sectional area of the vessel. It is therefore possible to obtain both the velocity and quantity of the blood flowing within the vessel.

Doppler sonography can be used without venous occlusion and can be used on clothed patients in different positions. However, Doppler techniques have certain disadvantages that may limit their use when studying lymphedema. The subject must remain very still during the examination period, and the Doppler probe must be held in the same position relative to the blood vessel during sequential or repeated tests. A well-trained examiner must do the ultrasound testing since the transducer must be aimed correctly relative to the artery or vein. Additionally, whether a single or dual beam Doppler is used to measure the flow velocity or quantity of blood, the values represent the blood flow taking place in a specific vessel. Therefore, Doppler techniques cannot be used to monitor the average blood flow in a segment or in various types of tissue within the segment. Doppler scans take a relative large amount of time to conduct, making simultaneous measurements on two arms difficult.

Electrical bioimpedance

The Impedance Plethysmograph (IPG) measures electrical impedance signal changes that vary with the blood content of the segment during each pulse.2,16,17 Previous research studies13,16,17–22 have shown the IPG technique to be both reliable and reproducible for use in the quantification of peripheral blood flow.

Based upon the assumption that an arm can be grossly represented by a cylinder when using a tetra-polar arrangement; four electrodes are placed on or around the given segment separated by various axial distances. A high frequency, low amperage electrical current is input between the outer two electrodes. Simultaneously, the impedance produced by the electrically conductive tissue and blood is measured between the inner electrodes. Blood entering the segment between the two inner electrodes during a pulse has the effect of placing a second resistor between the two recording electrodes that is parallel with the baseline (prior to the pulse) tissue resistance. This, in turn, decreases the total segmental resistance between the recording electrodes proportionally to the pulse blood flow.

Electrical bioimpedance provides a measure of the total conductive volume in the segment between the two sensing electrodes, rather than that of a discrete vessel or of a narrow cross-sectional slice of the segment. The subject should lie relatively still, but can move if necessary without adversely affecting the average results. In addition, the subject can be fully clothed during a given test sequence. The instrumentation is simple to use as the four electrodes are simply applied and the unit is turned on. The transducer does not have to be held in an exacting position to beam the signal down an artery or vein. Measurement takes 15–20 seconds. Impedance plethysmography, when used in conjunction with an electrocardiogram (ECG), can be used to obtain measurements of segmental circulation: volume; vascular tone; and the balance between arterial inflow and outflow from the monitored segment. A two-channel impedance instrument can be used to acquire simultaneous beat-by-beat flow measurements in two segments (i.e., right and left arm) at the same time.

Even though impedance plethysmography may be considered ideal for use in studies as the current one, several factors must be kept in mind regarding its application. It should not be used when other external electrical or magnetic signals are being introduced into the tissue. It should be used cautiously when the subject has implanted devices such as pacemakers, stimulators, etc. In addition, the subject should not have contact with metal surfaces or other conductive media that would affect the current flow path between the two input electrodes. To ensure good signal quality and reproducibility of sequential measurements, the impedance electrodes must be applied to clean dry tissue and replaced in the same locations during repeated test sessions. It is recommended that any protocol should be tested under operational conditions in the desired location before being made on subjects or patients to assess the affect of environmental conditions and the compatibility of the impedance device with other experimental instrumentation.

Study purpose

The purpose of this study was to compare segmental arterial blood flow, venous blood return, and blood volumes between breast cancer survivors with treatment-related lymphedema and healthy normal individuals without lymphedema using a Tetrapolar High Resolution Impedance Monitor (THRIM) and Cardiotachometer. Specifically, lymphedema-affected arms of volunteers were compared to nonaffected arms in breast cancer survivors with lymphedema and to nonlymphedematous arms in healthy normal volunteers. Since previous research has found there to be slight difference in impedance ratios between dominant and nondominant arms in healthy normal controls, we also compared dominant and nondominant arms in all participants.18

Materials and Methods

Participants

Approval was obtained from Institutional Review Boards in two University Medical Center settings to recruit healthy normal volunteers and breast cancer survivors with unilateral lymphedema from a parent study comparing arm measurement methods, the results of which have been published elsewhere.18 The protocol was tested in the laboratory prior to data collection. The 24 participants in this study represent women, 11 with lymphedema, and 13 healthy normal volunteers who completed blood flow analyses. Healthy normal volunteers were age 18 or older, had no history of lymphedema or breast cancer, and were capable of giving informed consent. Volunteers with lymphedema were age 18 or older and had a confirmed diagnosis of lymphedema in one limb only following breast cancer. Informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment.

Volunteers with conditions that would impact the measurement of limb volume, such as infection or skin lesions on limbs to be measured, metal implants, pacemakers, and allergy or other known sensitivity to electrode adhesive were excluded. Pregnant women were excluded due to possible normal fluid balance fluctuations that occur during pregnancy.

Recruitment

Flyers were posted in university and hospital/clinic settings, distributed to breast cancer and lymphedema support groups, and study information was posted on a Missouri School of Nursing website. Referrals for potential participants were accepted from physicians, nurses, physical therapists, and other study participants. Participants were compensated $10.00 for their time and effort.

Data collection procedures

Participants completed demographic self-report forms. During physiological data collection, participants were resting (for a period of 30 min) in a supine position on a non-metal massage table, and disposable ECG electrodes were placed on the backs of the right and left hands 1 cm proximal from the peak of the knuckle of the middle finger, at the right and left wrist between the process of the radial and the ulnar bone, and at the right and left shoulder joints after palpation. Thus, the hand was not included in this measurement. The same team member applied all electrodes to insure consistency of placement across all participants.

A two-channel THRIM IPG was then used to obtain continuous records of right and left arms' base resistances and pulsatile resistance changes. The THRIM IPG was a custom built (two channel) instrument similar in nature to the single channel units commercially available from UFI, Inc. (Morro Bay, CA). It operated at a constant fixed frequency of 50 KHz with an input current amplitude of 0.1 mAmp.

The right and left hand electrodes served as the input sites for the IPG carrier signal. The wrist and shoulder electrodes served as the pickup electrodes for the right and left arm segments. A continuous lead one electrocardiogram was also recorded using a UFI, Inc. Cardiotachometer. All physiologic parameters were recorded onto a PC computer using a Windaq (DATAQ, Inc) A/D conversion system at a rate of 200 Hz/channel. The digitized nonfiltered signals were then submitted to a custom program, Rheoencephalographic Impedance Trace Scanning System (RheoSys) for post-test analysis.19 The parameters calculated by the RheoSys program are based upon parameters established in previous studies.20–30 An appendix detailing this technology and defining the terms used in the in the rest of this article is included.

Whole arm volume was ascertained using perometric measurement (Perometer 350S).31 Each arm was measured in the horizontal position three times and a three-dimensional graph of the affected and nonaffected extremity was generated. This measurement was taken 15 minutes prior to the blood flow measurements.

Statistical procedures

Statistical summaries and analyses were performed using STATA Version 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Mann–Whitney were used to test for differences in age, education, and BMI between the healthy normal volunteers and those with lymphedema. Because several of the blood flow data distributions were severely skewed (e.g., BF ML/MIN, TOUT-Sec), the interquartile range (IQR) or 25th and 75th percentile values are presented in addition to mean and standard deviation (M ± SD) summaries. Associations between arm volume and blow flow values were assessed using Spearman Rank correlations. Bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals were generated for the continuous variables. These confidence intervals were then used to determine the statistical significance of the comparisons of lymphedema volunteers' affected arms to their nonaffected arms and to the dominant and nondominant limbs of the healthy normal volunteers. General Linear Modeling (GLM) that incorporated lymphedema status as a between subjects variable and arm measured as a within-subjects variable was used to test for global and specific differences in the blow flow measures. Generalized Estimation Equations (GEE) for parameter estimation of correlated data within the GLM methods were used to adjust for the lack of independence in the assessments of the arms. Due to the exploratory nature of this research and because the size of the apparent effects of lymphedema on the blood flow parameters were of most interest in this study, an alpha of 0.10 was used for determining the likelihood that there were statistically significant effects of either limb or lymphedema status or both (results from the GLM). If such an effect was found, this finding provided license for drilling down (via the use of the previously described confidence intervals) to see where specific differences might be (e.g., affected limb vs. all other sets). Because we used 95% confidence intervals for these pairwise post-hoc comparisons, the alpha level was 0.05 for those conclusions. A maximum alpha level of 0.05 was also used for conclusions based on standard tests (e.g., independent and dependent t-tests used for comparisons of sample characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics*

| Healthy (N = 13) | Lymphedema (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years ) | 45.5 (16.7) | 53.6 (8.9) |

| Education (years ) | 17.4 (2.6) | 16.4 (3.8) |

| Body mass index | 27.1 (5.7) | 30.8 (7.2) |

| Nondominant | Dominant | Unaffected | Affected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perometer arm volume (ml) | 2768.2 (763.3) | 2876.8 (746.9) | 3329.7 (1084.7) | 3812.3 (1399.1) |

Values in the cells are mean (SD).

A statistically significant difference (dependent t-tests) between arms was detected within both groups. Healthy (mean difference = 108.6, SD = 104.0, p = 0.007); Lymphedema (mean difference = 482.6, SD = 372.3, p = 0.006)

Results

Sample

Characteristics of the study participants are listed in Table 1. With the exception of a single volunteer with lymphedema, all participants were Caucasian. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups of healthy normal and lymphedema volunteers in terms of age, education, or BMI. Healthy volunteers' dominant to nondominant whole arm volume was significantly different, as was lymphedema volunteers affected to nonaffected whole arm volume.

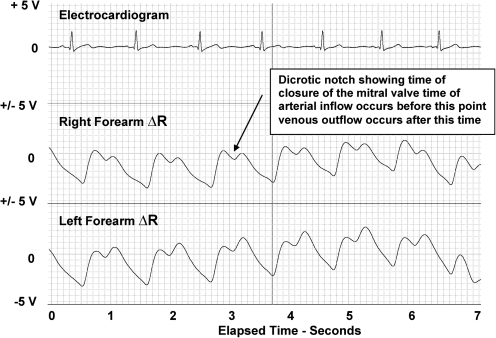

Pulsatile waveform

Figures 1 and 2 are shown for illustrative purposes with the x axis representing elasped time recorded at 25 mm/sec and the y axis representing each trace set at + and – 5 volts. These figures portray the differences in the typical blood flow pulse waveforms of the healthy normal female control group (Fig. 1) and those of a typical female lymphedema volunteer (Fig. 2). The traces (top to bottom) illustrate the subjects' ECG, right arm blood flow, and left arm blood flow. Note the absence of the dicrotic notch and the elevated venous component of the pulse in the lymphedema subject's blood flow pulses.

FIG. 1.

Healthy female arm.

FIG. 2.

Lymphedema female arm. The pulses from both the right and left arms of the lymphedema show an absence of a dicrotic notch and a large increase in the post-dicrotic venous component of the pulse waveform. Both characteristics indicate an increase in the relative amount of venous blood present.

Volume

When using whole arm volume as determined by the Perometer, an infrared scanning device, there was a positive correlation (0.60) between blood flow and whole arm volume (p = 0.002). Moderate negative correlations (−0.50) in time of venous outflow period of blood flow pulse (TOUT-Sec) (p = 0.001) and (−0.52) amplitude of the venous component of blood flow pulse signal (C-Ohm) (p = 0.040) were noted.

Arterial blood flow

Measures of blood flow that demonstrated an overall statistically significant difference among arm assessments (main effect of lymphedema, main effect of arm dominance, and/or interaction effect of lymphedema and arm dominance) are summarized in Table 2 (p < = 0.10). Observed effect sizes for the magnitude of the differences are also presented in the table. A subset of those summaries is also presented for further clarity in Table 3. As anticipated, average arterial blood flow (in units of ml/min) in lymphedema-affected arms was higher (p < = 0.001) than in arms of healthy normal volunteers or lymphedema nonaffected arms. Specifically, initial average arterial inflow angle of blood flow pulse (LI-DEG) was lower (p < = 0.069) in lymphedema-affected arms than in healthy normal or lymphedema nonaffected arms. The mean blood flow in the affected arm, in units of ml/min, was 28.3% greater than that in the contralateral unaffected arm. The mean affected arm blood flow was also greater, 9.2%, than that in the unaffected arm when blood flow in both arms was divided by the patients' arm volumes and expressed in units of ml/100 ml/min. No statistically significant differences were noted in blood flow between dominant and nondominant arms in the healthy normal controls.

Table 2.

Measures Blood Flow Demonstrating Statistically Significant Differences

| |

|

|

Control (N = 13)* |

LE (N = 11)* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Overall Test | Effect Size | Dominant | Nondominant | Unaffected | Affected |

| BF (ml/min) | P < 0.001 | 0.254 | 109.05 ± 15.26 | 85.73 ± 14.24 | 146.59 ± 24.98 | 188.13 ± 24.56 |

| (81.36–141.22) | (62.01–117.64) | (105.40–203.25) | (139.02–235.66) | |||

| C-Ohm | P = 0.005 | 0.190 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| (0.18–0.31) | (0.21–0.36) | (0.16–0.23) | (0.10–0.17) | |||

| TRATIO % | P = 0.014 | 0.180 | 0.79 ± 0.10 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.17 | 1.34 ± 0.23 |

| (0.62–1.00) | (0.56–0.87) | (0.71–1.38) | (0.89–1.78) | |||

| TOUT-Sec | P = 0.007 | 0.173 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.04 |

| (0.49–0.66) | (0.51–0.67) | (0.41–0.57) | (0.34–0.52) | |||

| VOI % SEC | P = 0.053 | 0.148 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| (0.20–0.32) | (0.14–0.29) | (0.25–0.35) | (0.30–0.40) | |||

| AVE R-Ohm | P = 0.006 | 0.124 | 236.88 ± 9.09 | 244.64 ± 9.27 | 234.28 ± 10.53 | 207.36 ± 13.76 |

| (218.43–253.04) | (225.52–261.16) | (214.43–254.81) | (178.27–233.77) | |||

| DCI-% Ohm | P = 0.038 | 0.122 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.76 ± 0.05 | 0.70 ± 0.05 |

| (0.72–0.83) | (0.78–0.90) | (0.67–0.85) | (0.62–0.79) | |||

| LI-DEG | P = 0.069 | 0.121 | 41.67 ± 2.63 | 42.39 ± 2.12 | 39.13 ± 2.82 | 33.58 ± 3.09 |

| (36.64–46.65) | (38.34–46.52) | (33.79–44.61) | (26.83–39.05) | |||

| DSI-% Ohm | P = 0.049 | 0.121 | 0.80 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 0.61 ± 0.08 |

| (0.65–0.94) | (0.75–1.11) | (0.60–0.97) | (0.46–0.77) | |||

| VE-L | P < 0.001 | 0.112 | 1.15 ± 0.11 | 1.11 ± 0.11 | 1.22 ± 0.10 | 1.48 ± 0.14 |

| (0.99–1.41) | (0.95–1.38) | (1.05–1.45) | (1.29–1.83) | |||

| C Index | P = 0.050 | 0.090 | 91.92 ± 4.74 | 91.99 ± 5.58 | 95.39 ± 4.91 | 104.87 ± 3.63 |

| (81.70–99.70) | (79.55–101.20) | (86.26–104.89) | (97.93–112.10) | |||

| BFVE (BF/VE) | P = 0.001 | 0.088 | 103.29 ± 16.70 | 83.45 ± 13.53 | 118.91 ± 16.53 | 129.89 ± 16.82 |

| (73.22–139.63) | (60.06–112.70) | (90.03–154.34) | (93.95–160.21) | |||

| BFPct (BFVE/100) | P = 0.001 | 0.088 | 10.33 ± 1.79 | 8.35 ± 1.47 | 11.89 ± 1.64 | 12.99 ± 1.74 |

| (7.18–14.02) | (5.71–11.29) | (9.33–15.80) | (9.60–16.33) | |||

| B-Ohm | P = 0.050 | 0.086 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.02 |

| (0.17–0.34) | (0.20–0.34) | (0.17–0.26) | (0.13–0.22) | |||

| TIN-Sec | P = 0.051 | 0.056 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.05 |

| (0.34–0.47) | (0.32–0.43) | (0.34–0.51) | (0.38–0.57) | |||

| PDNPTT-Sec | P = 0.058 | 0.055 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.64 ± 0.05 |

| (0.51–0.65) | (0.50–0.61) | (0.50–0.68) | (0.54–0.74) | |||

Numbers in cells are M ± SD (25th and 75th interquartile ranges representing the middle 50% of each sample). See Appendix for definition of terms.

Table 3.

Bioimpedance Parameters Found to be Statistically Significant at p < 0.05

| Parameters* | Findings |

|---|---|

| BF ML/MIN | Affected Lymphedema > All Others |

| C-Ohm | Affected Lymphedema < All Others |

| TRATIO- % | Affected Lymphedema > All Others |

| TOUT-Sec | Affected Lymphedema < All Others |

| VOI -% SEC | Affected Lymphedema > Control Dominant and Nondominant |

| AVE R-Ohm | Affected Lymphedema < Lymphedema Unaffected and Control Dominant |

| DCI-% Ohm | Affected Lymphedema < Control Dominant |

| LI-DEG | Affected Lymphedema < All Others |

| DSI-% Ohm | Affected Lymphedema < Control Dominant |

| VE-L | Affected Lymphedema > Lymphedema Unaffected, Control Dominant and Nondominant |

| C Index | Affected Lymphedema > All Others |

| BFVE (BF/VE) | Affected Lymphedema > Control Dominant |

| BFPct (BFVE/100) | Affected Lymphedema > Control Dominant |

| B-Ohm | Affected Lymphedema < Control Dominant |

| TIN-Sec | Affected Lymphedema > Lymphedema Unaffected |

| PDNPTT-Sec | Affected Lymphedema > Lymphedema Unaffected |

See Appendix for definition of parameter terms.

Venous return

The mean time of venous outflow period of blood flow pulse (TOUT-sec) was lower (p < = 0.007) in lymphedema-affected arms than healthy (0.15 sec, dominant: 0.17 sec, dominant) or lymphedema-unaffected arm (0.06 sec), suggesting there was less time for venous blood return in the lymphedema arms. The mean amplitude of the venous component of blood flow pulse signal, (C-Ohm), was lower (p < 0.05) in lymphedema-affected arms than healthy (0.10 Ohm, dominant; 0.13 Ohm, nondominant) or lymphedema nonaffected arms (0.06). The mean index of venular tone (DSI-% Ohm) was also lower (p < 0.049) in lymphedema-affected arms than in healthy, normal (0.19% Ohm, dominant; 0.32% Ohm, nondominant) or lymphedema-unaffected arms (0.16% Ohm).

Miscellaneous findings

Additionally, three other findings are worth noting. First, there was a trend towards the time of arterial inflow period of blood flow pulse being slightly higher in lymphedema-affected arms than healthy or lymphedema nonaffected arms. Second, the index of arteriolar tone trended slightly lower in lymphedema-affected arms than healthy or lymphedema nonaffected arms. Finally, the local pulse transit time (PDNPTT-sec) appeared higher in lymphedema-affected and unaffected arms than that of healthy normal arms.

Discussion

The nonsignificant volume ratio value of 3.6% when comparing the dominant to nondominant arms of the healthy normal control subjects is similar to volume ratios of 2%–4% in healthy control subjects found in other studies.11,32 Findings regarding arterial blood flow are supported by early work using venous occlusion plethysmography that found arterial flow, as expressed in ml/100 ml/min, resting blood flow at 34°C to be 35.3% higher in the lymphedema-affected arm than in the unaffected arm and at 44°C was 113% higher in the affected arm.5 Additionally, upon examination of lymphedema patients using intramuscular injection of Xe-133; the clearance rate of I-125 labeled 4-iodo-antipyrine, when injected into the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and intra-arterial injections of Krypton-85 found the blood flow in the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the lymphedema-affected arm was significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that in the unaffected forearm.5 More recently, mean percentage blood flow was reported 68% higher in the lymphedema-affected arms than the nonaffected arms of breast cancer patients and 38% increase on the breast cancer treatment side of the breast cancer patients as compared to the nontreatment side.2 In this study, 54% of participants with lymphedema had a greater than 50% increase of low in the affected limb. Similarly, another study4 using Doppler ultrasound found the mean (+sem) arterial blood flow in lymphedema arms to be higher (689.73 + 44.6 ml/sec) than that in the unaffected arm (427.73 + 30.8 ml/sec) and in patients without arm swelling (447.75 + 37.8 ml/sec). Venous abnormalities were not detected in either group of patients.

In contrast, one study using venous occlusion plethysmography with a conventional mercury strain gauge and an optical volumeter (Perometer™) found lower arterial blood flow in the affected arm of lymphedema patients when compared to the contralateral unaffected arm.33 Blood flow using the strain gauge was 86.5% lower in the affected arm than in the unaffected arm when expressed in units of ml/100 ml/min. However, when the increased volume of the swollen arm was factored into the measurement (blood flow expressed in units of ml/min) the blood flow in both the affected arm and unaffected arms were found to be essentially the same. The mean volume of the affected forearm (1488 ml) was reported to be 1.52 times (p < 0.0001) that of the control forearm (979 ml). The authors attributed the apparent decrease in percentage total blood flow (ml/100 ml/min) into the swollen arm, as compared to the insignificant difference in total blood flow (ml/min), to be due to the “dilution” effect of the larger nonperfused interstitial volume in the affected arm.

Several factors must be taken into consideration when comparing the blood flow results of different studies or the results of the current investigation to those published in the open literature. Two variables that influence the blood flow measurements of the affected arm of lymphedema patients are the protocols used to measure the blood flow and the amount of swelling in the arm at the time of measurement. For example, in protocols are the hands and arms both included in the monitored segment? Does the measurement procedure include blood flow in all tissues of the segment or just through specific major vessels or tissue (skin, muscle, etc.) or does it impose changes in the blood flow as is done when cuffs are inflated around the arm or around both the arm and hand? The segmental volume of the swollen arm at the time of the blood flow measurement may also explain the variance among blood flow studies. In the present study, blood flow into the affected arm was found to be 28.3% greater in the swollen arm than in the contralateral unaffected arm. The lymphedemic arm volume was found to be 21.3% greater than that of the unaffected arm. In contrast, other studies reported increased blood flow in the affected arm to be greater when the arm volume ratio was higher than that of the present study. Other studies of the circulatory effects of lymphedema were done on patients with much higher volume ratios of between ∼1.50 to 1.90 (56%, Stanton et. al., 1996; 80%, Jacobsson, 1967; 90%, Jacobsson, 1967).5,11

An additional important consideration is whether the blood flow is reported as total blood flow into the segment (ml/min) or as flow per unit volume (ml/100 ml/min). Most of the above studies report a significant percentage increase of total blood flow (ml/min) in the swollen arm compared to the contralateral unaffected arm varying between ∼30 and ∼100%. In turn, they report lower percentage increased blood flow in the swollen arm when the arterial inflow is measured or calculated in units of ml/100 ml/min. This finding may be the result of dividing the given arterial inflow by a larger segmental volume as the fluid content of the lymphedemic arm increases over time.

As stated by Stanton et al. (1996, p. 1435) “any form of edema arises from an imbalance between input (capillary filtration) and output (lymphatic drainage).” There is general agreement in the literature that the occurrence of lymphedema following cancer treatment is a complex phenomenon whose pathophysiology can not be explained by a simple “stopcock” approach.34,35

Several of the indices derived from the impedance pulse waveforms identified in this study are consistent with findings that venous function may be impaired by lymphedema. One study using Doppler ultrasonography assessed status of the axillary vein before and at 3 and 12 months after surgery.32 The researchers identified significant reduction in vein wall movement after surgery and significant alterations to venous flow patterns in those patients with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema. In our study, the pulse height at the dicrotic notch (B-Ohm), amplitude of the venous wave component (C-Ohm), and the index of venular tone (DSI-Ohm) were all found to be significantly lower in the affected arm than the similar values in the control dominant arms. The amplitude of the venous wave component (C-Ohm) and the time of venous outflow (TOUT-sec) were found to be significantly less in the affected arm than in the nonaffected arm or the dominant and nondominant arms of healthy normal volunteers.

The consensus of several studies is that the general sympathetic system is not affected by lymphedema and that the circulatory impairment resides predominately in the local vascular control of the lymphedematous arm. Our findings that: 1) PTT-sec (an index of systemic vascular state) of the affected arm was not significantly different than that of the unaffected arm; and 2) that PDNPTT-sec (an index of local vascular state) is significantly greater in the affected arm support this conclusion. Additionally, the findings that the initial arterial inflow angle (LI-DEG) and the index of arterial tone (DCI-% Ohm) were both significantly lower in the swollen arm is suggestive of vasodilator impairment in the affected arm. This may contribute to the greater arterial blood flow into the affected arm, as indicated by the significantly greater time of arterial inflow (TIN-sec) found in the swollen arm.

Taken together, our results suggest that a decrease in local vascular tone in the swollen arm, together with an increase in the arterial blood flow into the affected limb, coupled with reduced venous function, will produce an imbalance between arterial and venous flow and thereby promote edema in the affected arm. This imbalance is also indicated by the fact that the TRATIO index obtained from the swollen arm was significantly greater than that of the contralateral control arms in this study.

One unexpected observation from this study that is worth noting is the possible indication that the pathophysiology of the affected arm may alter the hemodynamic characteristics of the unaffected arm of lymphedema patients. As noted in Table 2, many of those parameters that were found to be significantly lower or higher in the swollen limb than the contralateral limb of the lymphedema patients also exhibit a similar mean difference (although not significant) between the unaffected limb of the patients and that of either arm of the healthy normal control subjects. For example, consider the amplitude of the venous component of the pulse waveform (C-Ohm). C-Ohm of the affected arms (0.14–Ohm) is significantly (p < 0.005) lower than that of the opposite arms of the lymphedema patients (0.20–Ohm) whose mean value is still lower (not significantly) than the values for the dominant and nondominant arms of healthy normal volunteers (0.24–Ohm and 0.27–Ohm, respectively). Many of the other waveform parameters (which may be compared across subject populations) show this possible interaction between the affected and unaffected arms of lymphedema patients.

The results of the current and past investigations should be interpreted in light of the type of blood flow measurement techniques used, the tissue monitored by the various techniques, and the characteristics of the subject population tested. Since impedance plethysmography measures the total instantaneous volume of the monitored segment, these blood flow values represent the average value in all tissues located between the instrumentation “pickup” electrodes. In this way, the measured blood flow cannot be attributed to any individual tissue component in the arm. The empirical indices obtained in this study were calculated from the amplitudes, angles, areas, and time increments of the pulse waveforms and, as such, are not dependent upon electrical transmission properties of the monitored segment. Similar indices could thus be obtained from other pulse waveform recordings (i.e., photoelectric sensors and pulse pressures). In this way, the derived indices may be compared across body segments and subject populations.

A strength of this study design was the clear, dichotomous sample of breast cancer survivors with known lymphedema and healthy normal volunteers with no known history of breast cancer or lymphedema. Limitations of this study include use of a single method to measure blood flow, small sample size, and lack of representation of individuals at risk for lymphedema (e.g., breast cancer survivors without known lymphedema). Many authors have used different techniques to investigate various aspects of the time course and pathophysiology of lymphedema. Although a detailed discussion of the pathophysiology of lymphedema is beyond the scope of the present article, the results obtained from bioimpedance instrumentation might be of value in such research and provide additional insight into the hemodynamic state of lymphedema. For those interested in additional information regarding the pathophysiology of lymphedema, we recommend the article by Mortimer.10 A recent article by Stanton et al.35 reviews the current advances and understanding of breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that, when compared to healthy normal arms and contralateral unaffected arms, lymphedema-affected arms in the breast cancer survivors may experience alterations in both arterial and venous components. Findings from this study should be considered in light of the limitations imposed by a small sample size and therefore, future research in a larger sample is needed to fully explore these issues.

Appendix

Impedance Plethysmography Data Analysis

Principles of impedance plethysmography from physical characteristics to body volume

The resistance (R) of a length of homogeneous conductive material of uniform cross-sectional area is proportional to its length (L) and inversely proportional to its cross sectional area (A).

Therefore:

|

and the actual resistance of the conductor is given by:

|

where:

|

Multiplying the equation by L/L provides:

|

where: V = A * L = the volume of the conductive medium.

Transposing the V and R provides:

|

Using this relation the volume of a conductor can be calculated, at a given point in time, by measuring the resistance of a current that is passed through the conductor and the conductive path length and knowing the resistivity of the conductive medium. This relation forms the basis of impedance plethysmographic measurement of segmental volumes within the human body. It also allows the quantification of the segmental volume changes that take place between two points in time (i.e., blood flow into the body segment between times t = 0 and t = 1). As set forth by Nyboer. 25 The segmental volume at t = 0 is;

|

and the segmental volume at t = 1 is

|

Therefore, the volume change between times t = 0 and t = 1 is given by:

|

or

|

and, assuming the absolute values of R0 and R1 are nearly equal, compared to the difference between the two resistances, ΔR, the relation can be rewritten as:

|

which gives the volume change (ml) that takes place in the segment between times t = 0 and t = 1 (sec). In this way the relation yields the rate of volume change in units of ml/sec or ml/min.

As stated earlier, an impedance plethysmograph is used to pass an external signal through a body segment and to measure the resistance that the segment imposes upon that signal at different points in time. When taken in conjunction with the ECG and knowing the length of the body segment and the respective values of R, it is possible to quantify both segmental volume and blood flow using the above equations. Other physiologic and hemodynamic indices can also be calculated from the impedance pulsatile recordings and event times as explained below.

Analysis of impedance plethysmographic recordings

An example of the four traces recorded and displayed by the WinDaq Waveform Browser data acquisition system for one arm during the investigation is shown in Figure A1: (from top to bottom) forearm base electrical resistance (Ro), electrocardiogram (ECG), forearm electrical resistance changes (ΔR), and first derivative of forearm electrical resistance changes (dR/dT). This trial was completed with the subject lying quietly in a supine position.

FIG. A1.

An example of four traces using the WinDaq Waveform Browser data acquisition system. Ro, base resistance; ECG, electrocardiogram; ΔR, change in base resistance during cardiac cycle; dR/dt, final derivative of ΔR trace.

Quantitative measures of monitored segment blood flow and hemodynamic status were computed ex post facto for each arm using a custom program, Rheoencephalographic Impedance Scanning System (RheoSys), developed by LDM Associates. The analysis proceeds from a graphical display of the overall impedance ΔR and ECG traces. The operator first selects individual impedance pulse waveforms from which blood flow and other hemodynamic parameters are to be calculated. RheoSys then proposes the placement of seven vertical reference lines in each selected pulse waveform, as displayed by the computer for one selected IPG pulse in Figure A2.

FIG. A2.

A selected impedance plethysmography pulse. ΔR, change in base resistance during cardiac cycle; dR/dt, first derivative of ΔR trace; ECG, electrocardiogram.

The seven lines mark the following features of the selected pulse waveform:

| M1. | Peak of the ECG QRS complex immediately preceding the selected IPG pulse, |

| M2. | Start of the systolic upslope of the IPG pulse, |

| M3. | Maximum amplitude of the IPG pulse, |

| M4. | Position of the dicrotic notch in the IPG pulse, |

| M5. | Maximum amplitude of the post-dicrotic segment of the IPG pulse, |

| M6. | Peak of the ECG QRS complex immediately after the systolic upslope of the selected IPG pulse, and |

| M7. | Start of the systolic upslope of the next IPG pulse. |

Landmarks in an impedance pulse, marked by vertical lines labeled M1, M2, …,M7. Traces from top to bottom: IPG ΔR waveform, calculated first derivative of the ΔR waveform (dR/dt) in the top trace, ECG waveform, and dR/dt waveform provided directly by the THRIM hardware. (Only the dR/dt waveform computed from the IPG ΔR waveform is used in RheoSys.) The horizontal dotted line in the computed dR/dt trace is the dR/dt = 0 line. The time at each landmark is tM1, tM2,…, and tM7, respectively, and the corresponding IPG ΔR amplitude is RM1, RM2, …, and RM7, respectively.

The seven reference lines used by RheoSys for calculation of the various parameters must be placed in the precise locations listed above. The RheoSys program may not locate a given reference line in the correct location due to noise or artifact in the trace waveform. To ensure proper location of the reference lines and to eliminate any subjectivity in the analysis, the operator must review the selected reference points for each point. The operator is then asked to accept the proposed reference points as shown by RheoSys or relocate them to their proper location.

After the operator accepts the placement of these reference lines, the times and signal amplitudes at the selected points are used to calculate the following cardiovascular and hemodynamic parameters for each pulse:

| HR (beats/min) |

, with tM1 and tM6 in seconds , with tM1 and tM6 in seconds |

| A (Ohm) | Rheographic Index of pulse volume as determined from the maximum height of the systolic portion of the IPG waveform (A) when converted to Ohm resistance |

|

|

| B (Ohm) | Height of the IPG waveform at the dicrotic notch when converted to Ohm resistance |

|

|

| C (Ohm) | Height of the IPG waveform at the dicrotic notch when converted to Ohm resistance |

|

|

| DCI (% Ohm) | Dicrotic Index of arteriolar tone calculated as the ratio of C/A |

| DSI -(% Ohm) | Diastolic Index of venular tone calculated as the ratio of B/A |

| ST (Ohm-sec) | Total area under the selected IPG pulse waveform from the start of the pulse at tM2 to the start of the next pulse at tM7: |

|

|

| Where j is the index for the IPG resistance datum at tM2, k is the corresponding index at tM7, and Sr is the sample rate (s–1) | |

| R0 (Ohm) | Average base resistance of the monitored segment during the IPG pulse given by

|

| EXHT (Ohm) | Extrapolated IPG pulse amplitude given by the Nyboer25 back-projection: |

|

|

| BF (ml/min) | BF segmental blood flow (calculated according to Nyboer)25 |

| BF = HR * EXHT * ρ *L2/R02 | |

| where ρ is the specific resistivity of blood 150 Ohm-cm22,25 and L (cm) is the separation distance between the two segmental sensing electrodes | |

| BFN (ml/min · ml) | Normalized segmental blood flow given by |

| BFN = BF/Vg | |

| where Vg = C2 L/4π is the segmental geometric volume with C (cm) as the measured maximum circumference of the monitored segment | |

| PTT (sec) |

, is the time interval between the ECG QRS complex immediately preceding the selected IPG pulse and the start of the selected IPG pulse.24 , is the time interval between the ECG QRS complex immediately preceding the selected IPG pulse and the start of the selected IPG pulse.24

|

| PDNPTT (sec) | Post dicrotic notch pulse transit time = (tM5 − tM1) calculated as the time interval between the ECG QRS complex and the time of the occurrence of the maximum IPG pulse amplitude following the dicrotic notch |

| TIN (sec) |

, the time period from start of the IPG pulse until the occurrence of the dicrotic notch27 , the time period from start of the IPG pulse until the occurrence of the dicrotic notch27

|

| TOUT (sec) |

, the time period from the dicrotic notch until the end of the IPG pulse27 , the time period from the dicrotic notch until the end of the IPG pulse27

|

| TRATIO (%) | Ratio of TIN to TOUT |

| C Index | Jacquy's Capacitance—C Index20 1/sec or regional vasomotor capacitance. |

| AVE R–Ohm | Average base resistance during the IPG pulse duration |

| LI–DEG | Initial angle (between 0 and 10% of systolic amplitude) of IPG systolic rise |

| VOI–% SEC | Ratio of the time period between the maximum IPG pulse amplitude and the dicrotic notch to the total IPG cycle time |

| BFVE (ml/min.L) | Blood flow rate (ml/min) per liter of total arm segment volume (Ve) monitored during each test = BF/Ve |

| BFPct (ml/100 ml/min) | Percent blood flow rate (ml/min) per 100 ml of arm tissue = BFVE/100 |

| Note that A, ST, and EXHT are measures of pulse morphology independent of heart rate. In contrast, BF includes the influence of heart rate. The calculated output parameter values from RheoSys were stored in Excel spreadsheet format for statistical analysis. |

Footnotes

Funding: NIH SBIR NHLBI Phase I Grant No. 1 R43 HL074524-01(Montgomery); Vanderbilt University Post-Doctoral Fellowship (Ridner); 1 R01 NR05342-01 (Armer); 07/15/01 – 4/30/06 (10/30/07 NCE); NIH/NINR and MU PRIME; Prospective Nursing Study of Breast Cancer Lymphedema – R01.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Missouri and Vanderbilt Research staff and all participants.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Tsai R. Dennis L. Lynch C. Snetselaar L. Zamba G. Scott–Conner C. The risk of developing arm lymphedema among breast cancer survivors: A meta-analysis of treatment factors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1959–1972. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svensson WE. Mortimer PS. Tohno E. Cosgrove DO. Increased arterial inflow demonstrated by Doppler ultrasound in arm swelling following breast cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30:661–664. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin KP. Földi I. Are hemodynamic factors important in arm lymphedema after treatment of breast cancer? Lymphology. 1996;29:155–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yildirim E. Soydinc P. Yildirim N. Berberoglu U. Yüksel E. Role of increased arterial inflow in arm edema after modified radical mastectomy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2000;19:427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsson S. Blood circulation in lymphoedema of the arm. Br J Plastic Surg. 1967;20:355–358. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(67)80066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanton AWB. Holroyd B. Mortimer PS. Levick JR. Comparison of microvascular filtration in human arms with and without postmastectomy oedema. Exp Physiol. 2001;84:405–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445x.1999.01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svensson WE. Mortimer PS. Tohno E. Cosgrove DO. Colour Doppler demonstrates venous flow abnormalities in breast cancer patients with chronic arm swelling. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1994;30:657–660. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solti F. Iskum M. Bános C. Salamon F. Arteriovenous shunt-circulation in lymphoedematous limbs. Acta Chirurg Hungarica. 1986;27:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton AWB. Svensson WE. Mellor RH. Peters AM. Levick JR. Mortimer PS. Differences in lymph drainage between swollen and non-swollen regions in arms with breast-cancer-related lymphoedema. Clin Sci. 2001;101:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mortimer PS. Trust W. Trust CSC. The pathophysiology of lymphedema. CA: Cancer J Clin. 1998;83:2798–2802. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12b+<2798::aid-cncr28>3.3.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanton AW. Levick JR. Mortimer PS. Cutaneous vascular control in the arms of women with postmastectomy oedema. Exp Physiol. 1996;81:447–464. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eickhoff JH. Engell HC. Local regulation of blood flow and the occurrence of edema after arterial reconstruction of the lower limbs. Ann Surg. 1982;195:474–478. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198204000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery LD. Comparison of an impedance device to a displacement plethysmograph for study of finger blood flow. Aviation Space Environ Med. 1976;47:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyman C. Winsor T. History of plethysmography. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1961;2:506–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qvarfordt P. Christenson JT. Eklöf B. Jönsson PE. Ohlin P. Intramuscular pressure, venous function and muscle blood flow in patients with lymphedema of the leg. Lymphology. 1983;16:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schraibman IG. Mott D. Naylor GP. Charlesworth D. Comparison of impedance and strain gauge plethysmography in the measurement of blood flow in the lower limb. Br J Surg. 1975;62:909–912. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800621113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van de Water JM. Indech RB. Laska ED. Mount BE. Yablonski MR. V CW. The calibrated impendance plethysmograph: Laboratory and clinical studies. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;21:463–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridner SH. Montgomery LD. Hepworth JT. Stewart BR. Armer JM. Comparison of upper limb volume measurement techniques and arm symptoms between healthy volunteers and individuals with known lymphedema. Lymphology. 2007;40:35–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery LD. Montgomery RW. Guisado R. Rheoencephalographic and electroencephalographic measures of cognitive workload: Analytical procedures. Biol Psychol. 1995;40:143–159. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(95)05117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacquy J. Charles P. Piraux A. Noël G. Relationship between the electroencephalogram and the rheoencephalogram in the normal young adult. Neuropsychobiology. 1980;6:341–348. doi: 10.1159/000117780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovett Doust JW. Barchha R. Lee RSY. Little MH. Watkinson JS. Acute effects of ECT on the cerebral circulation in man. Eur Neurol. 1974;12:47–62. doi: 10.1159/000114604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohapatra SN. Non-invasive Cardiovascular Monitoring by Electrical Impedance Technique. London: Pitman Medical Ltd.; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moskalenko YE. Cooper R. Crow HJ. Walter G. Variations in blood volume and oxygen availability in the human brain. Nature. 1964;202:159. doi: 10.1038/202159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nitzan M. Khanokh B. Slovik Y. The difference in pulse transit time to the toe and finger measured by photoplethysmography. Physiol Meas. 2002;23:85–94. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/23/1/308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyboer J. Kreider MM. Hannapel L. Electrical impedance plethysmography: A physical and physiologic approach to peripheral vascular study. Circulation. 1950;2:811–821. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.2.6.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Usochev V. Shinkarevskaya I. Functional changes in systemic and regional (intracranial) circulation accompanying low acceleration. Kosmicheskaya Biologiya I Aviakosmicheskaya Meditsina. 1973;19:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y. Gerth W. Montgomery L. Bioelectrical impedance indices decompression-induced bubble formation and hemodynamic changes in rats. UHMS Meeting Abstracts. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarullin KK. Benevolenskaya TV. Lobachik VI, et al. Studies of central and regional hemodynamics by isotope and impedence methods during LBNP. USSR Rept Space Biol Aerospace Med. 1980;14:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarullin KK. Gornago VA. Vasilyeva TD. Gugushvili MY. Studies of prognostic significance of antiorthostatic position. USSR Rept Space Biol Aerospace Med. 1980;14:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yarullin KK. Krupina TN. Vasil'yeva TD. Buyvolova NN. Changes in cerebral, pulmonary, and peripheral blood circulation. Kosmicheskaya Biologiya 1 Aviakosmicheskaya Meditsina. 1972;6:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tierney S. Aslam M. Rennie K. Grace P. Infrared optoelectronic volumetry, the ideal way to measure limb volume. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:412–417. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(96)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pain SJ. Vowler S. Purushotham AD. Axillary vein abnormalities contribute to development of lymphoedema after surgery for breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:311–315. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanton AWB. Holroyd B. Northfield JW. Levick JR. Mortimer PS. Forearm blood flow measured by venous occlusion plethysmography in healthy subjects and in women with postmastectomy oedema. Vasc Med. 1998;3:3–8. doi: 10.1177/1358836X9800300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellor RH. Stanton AW. Azarbod P. Sherman MD. Levick JR. Mortimer PS. Enhanced cutaneous lymphatic network in the forearms of women with postmastectomy oedema. J Vasc Res. 2000;37:501–512. doi: 10.1159/000054083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanton A. Modi S. Bennett Britton T, et al. Lymphatic drainage in the muscle and subcutis of the arm after breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treatment. 2009;117:549–557. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]