Abstract

Over the past several decades, the number of youth with parents in prison in the U.S. has increased substantially. Findings thus far indicate a vulnerable group of children. Using prospective longitudinal data gathered as part of the population-based Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT) randomized controlled trial, adolescents who had an incarcerated parent during childhood are compared to those who did not across four key domains: family social advantage, parent health, the parenting strategies of families, and youth externalizing behavior and serious delinquency. Past parental incarceration was associated with lower family income, parental education, parental socioeconomic status, and parental health, and with higher levels of parental depression, inappropriate and inconsistent discipline, youth problem behaviors and serious delinquency. The effect sizes for significant associations were small to moderate.

Keywords: children, delinquency, discipline, externalizing behavior, incarcerated parents

Since 1980, the number of imprisoned adults has quadrupled in the United States, increasing from 320,000 to nearly 1,420,000 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2004), a rate which far surpassed the estimated 23% general population growth in the United States (Perry & Mackun, 2001). Since a majority of incarcerated adults are parents (Glaze & Maruschak, 2009), the population of children with incarcerated parents has also grown (Travis & Waul, 2003). Between 1991 and 2007, the number of minor children with a parent in a state or federal prison increased from about 1 million to over 1.7 million children (Glaze & Maruschak, 2009), or 2.3% of all the children in the United States. A similar number of children have parents who were released from prison or jails within the last few years (Mumola, 2002). Absent from either count are the over 5 million children whose parents have been involved in the corrections system in the more distant past but are not currently under supervision (Reed & Reed, 1997). Taken together, over 8 million minor children (roughly 11% of all children in the United States) may be affected by parental incarceration.

Findings to date indicate a vulnerable group of children at risk for mental health problems, substance abuse, delinquency, school difficulties, and future criminal behavior (Johnston, 1995; Murray & Farrington, 2005; Myers, Smarsh, Amlund-Hagen, & Kennon, 1999). A recent meta-analysis of research on children with incarcerated parents found that children of inmates are twice as likely to exhibit antisocial behaviors as children without incarcerated parents, and that this increased risk is present even when controlling for other established risk factors for these problems (Murray, Farrington, Sekol, & Olsen, 2009). In light of the association of antisocial behaviors to poor outcomes later in life, particularly future delinquency and criminal behavior, understanding the etiology of this antisocial behavior for children whose parents were incarcerated is crucial in breaking potential intergenerational cycles of antisocial behavior and criminality.

Using prospective, longitudinal, population-based data, this study compares adolescents who experienced parental incarceration during childhood versus those who did not. Specifically, it focuses on differences in three general areas of family risk (family social advantage, parent health, and parenting strategies) and two related areas of adolescent adjustment (externalizing behavior and serious delinquency). While many studies have documented the important role of family and parenting factors in child adjustment, few studies have used population-based data to investigate these relationships in the context of children of incarcerated parents. Population-based data not only contains built-in comparison groups, it also provides an estimate of the incidence of parental incarceration for children. While there have been several point-in-time prevalence estimates of children with incarcerated parents (Glaze & Maruschak, 2009; Mumola, 2000), there are few estimates within the United States of the overall number of children who have experienced parental incarceration across their childhood.

The incarceration of a family member is unlikely to mark the beginning of problems for a child and family. Rather, it is often a continuation or exacerbation of an already challenging situation in lives marked by little education, poverty, unstable home life, substance abuse difficulties, mental health problems, abuse, trauma, and community violence (Johnston, 1995; Travis & Waul, 2003). Not surprisingly, a recent study of children of incarcerated parents (Poehlmann, 2005) found that a majority were exposed to four or more risk factors in the areas of child and family risk. A growing body of research indicates that the presence of multiple risk factors increases a child’s likelihood of developing problems including substance abuse, delinquency, violence, and other antisocial behavior (Dallaire, 2007; Farrington, Jolliffe, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Kalb, 2001; Poehlmann, 2005). In research on the general population, low socio-economic status (SES), parent antisocial behavior, poor parent mental health, poor parent-child relationships and poor parenting are all predictors of higher externalizing behaviors, and serious delinquency (Ackerman, Brown, & Izard, 2004; Connell & Goodman, 2002; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998).

While facing the numerous risks associated with parental incarceration may increase the chance that a child will have poor outcomes, such a situation does not mean that child maladjustment is inevitable. Findings from a variety of studies suggest that a stimulating, safe, and responsive family environment, including the use of effective parenting strategies, not only cultivates children’s cognitive and language development, but also can be a key protective factor for a child’s emotional and behavioral health during a stressful period (Eddy & Chamberlain, 2000; Knutson, DeGarmo, & Reid, 2004). In their meta-analysis focusing on the effect of parenting specifically on child externalizing behaviors, Rothbaum and Weisz (1994) found that praise, positive motivational strategies, synchrony and the absence of coercive control were associated with fewer child externalizing behaviors. Several studies on the children of incarcerated parents have found similar protective roles of the family environment and parenting (Poehlmann, 2005; Mackintosh, Myers, & Kennon, 2006).

Social Interaction Learning Theory (Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989) is helpful in conceptualizing how parental incarceration, family functioning, parenting strategies, and child adjustment might be related. The theory suggests that children and their families are in continual interaction with one another, mutually influencing one another over time. It is through this interaction that behavior (both prosocial and antisocial) is learned, strengthened, and maintained. In the early stages of child development, risk factors influence child behavior to the degree that they affect family functioning and parenting practices. In later years, additional proximal groups such as peers, mentors, and teachers influence child’s behavior, yet parents remain influential through their monitoring and supervision of a youth’s day-to-day activities.

The current study is a first step in exploring these potentially critical associations between parental incarceration, family functioning, parental health, parenting, and youth problem behavior. We hypothesize that adolescents who experienced parental incarceration during their childhood are more likely to experience family risk in the areas of social advantage, parent health, and parenting as well as have higher levels of problem behavior across adolescence than those adolescents who did not experience childhood parental incarceration.

Methods

Participants

Participating families (N = 655) for these analyses include all of the original families from the longitudinal Linking Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT) study (Reid, Eddy, Fetrow, & Stoolmiller, 1999) who were involved in the study at 5th grade. LIFT is an ongoing, population-based, randomized controlled school-based preventive intervention trial, which began in 1991. The trial recruited first and fifth graders and their families from 12 public elementary schools within the Eugene-Springfield metropolitan area (population 200,000) of Oregon. These schools were located in the top 50% of local neighborhoods in terms of police contacts with juveniles. Approximately half of the target youth were females (n = 334) and half were males (n = 321). Similar to the local population, youth and their families were primarily Caucasian and from the lower to middle socio-economic classes (for complete details see Reid et al., 1999).

Measures

All the measures, excluding serious youth delinquency, were assessed when the target youth were in the 5th grade where the average age of the children was approximately 10 years (M = 10.21, SD = .61). In addition to being assessed in 5th grade, adolescent problem behavior was additionally measured when the youth were in 8th and 10th grades. Serious youth delinquency was measured at 10th grade. In 8th grade, the youth were slightly less than 14 years (M = 13.87, SD = .54) and, in 10th grade, the youth were slightly less than 16 years (M = 15.74, SD = .53). Multiple sources were used to measure many of the constructs to reduce the possibility of a reporting bias that can occur when only one reporting agent is used. The specific sources are listed under each measure.

Parental incarceration

The current study focused on the effect of parental incarceration during the first 10 years of the child’s life. Information on parental incarceration was gathered from two main sources: a) official records from city, county and state correction departments, and b) the most recent wave (wave 15) of data collection in the LIFT investigation where the target youth (who ranged in age from 20 to 25 years old at this wave) were asked several questions about the arrest and incarceration history of their parents. From these two sources of data, a dichotomous variable was developed that indicated if a parent was incarcerated at least one day at any time during the children’s first ten years of life. This particular child developmental period and definition of the parental incarceration were chosen to directly map on to the work of Murray (2006), a study which used a similar population-based sample (from the U.K.) to examine the effects of parental incarceration.

Social advantage

Five aspects of a family’s social advantage were examined: the family household income, the number of hours worked by parents in the household, parents’ education level, parents’ occupational level, and parents’ socioeconomic status (SES). All of these measures were based, when possible, on each parents’ report. These components were all measured when the children were in 5th grade through self-reported data obtained from the parents in the Parent Major Interview (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990). Family household income was broken down into 10 categories ranging from 1 (less than $5,000) to 10 ($60,000 or more). The number of hours worked was calculated for each parent. Parents’ educational level had 7 categories ranging from 1 (less than 7th grade) to 7 (graduate with professional training). Parents’ occupation level was broken down into 9 categories (1 = “Farm/menial work” to 9 = “Executive/major professional”). The parents’ SES was measured by Hollingshead’s Four Factor Index of Social Status (1975).

Parent health

Two dimensions of parental health were examined: parental depression and parental physical health. Both of these measures were based, when possible, on each parents’ report. The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D scale) was used to assess each parent’s level of depression (Radloff, 1977). The 20-item questionnaire focuses on feelings and symptoms of depression (e.g. respondents were bothered by things, felt like life was a failure). Cronbach’s alphas for this sample ranged from .80 to .91 across cohorts. The parents’ physical health was assessed through the Physical Health Inventory (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990), in which parents were asked to rate their current state of health (1 = “excellent” to 4 = “poor”). The measure was reverse coded so that a higher score reflected better physical health.

Effective parenting

Six dimensions of parenting were examined: monitoring, parent involvement, quality of parent/child relationship, praise, inappropriate discipline, and inconsistent discipline. Data on these different dimensions of parenting were obtained from the Parent Major Interview (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990), the House Rules Questionnaire (French & Weih, 1990) and the Family Activity List (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990). With each instrument, mothers and fathers were interviewed separately on different parenting strategies. The separate scores were averaged to arrive at the final score for each dimension. What follows are explanations of each of these aspects of effective parenting.

Monitoring was assessed with the House Rules Questionnaire (French & Weih, 1990) and consisted of a summative score based on parents’ responses to six 5-point Likert scaled items (1 = “always true” to 5 = “always false”), reflecting different aspects of monitoring (e.g., “child is allowed to have friends over when a parent is not home”, “parent knows most of the child’s neighborhood friends”). The scores ranged from 6 to 30 and were reversed coded so that higher scores reflected higher monitoring. Cronbach’s alphas were not calculated for this variable as the score was a sum of items that are not necessarily correlated with one another.

Involvement was measured through two instruments: the Parent Major Interview (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990) and the Family Activity List (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990). In the Parent Major Interview, parents were asked four questions that assessed how often the parents talked or spent time with their child. Two of the questions used 5-point Likert scaled items (1 = “never”, to 5 = “every day”) and the other two involved parents estimating the number of hours per week the parent and child interacted (e.g., “talked with one another”, “did things with one another”). In these latter questions, the number of hours was capped at 40 and then divided by 10 to scale down the item to the 1 - 4 range to be more in line with the 1 – 5 scale of the other items. The score from the Parent Major Interview was the mean response of all items. The measure demonstrated adequate reliability with alpha scores ranging from .60 to .71 across cohorts. The Family Activity List consisted of 22 questions that reflected whether a parent had participated (e.g., “yes” or “no”) in different positive activities with the child (e.g., “read a book”, “played a game”, “watched a movie”). The Family Activity List index consisted of a sum of items, which were then divided by 10 to scale down items. Cronbach’s alphas were not calculated for family activities as the score was a sum of items that are not necessarily correlated with one another. However, the Family activity score correlated strongly (r = .40 - .44 across waves) with the score obtained the Parent Major interview. The mean of scores from the Parent Major Interview and the Family Activity List was calculated to arrive at the final “involvement” score for each parent.

The quality of the parent/child relationship was measured through the Parent Major Interview (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990) and was based on two 5-point Likert scaled questions. Each parent rated how well they got along with the child (from 1 = “not well”, to 5 = “very well”) as well as how enjoyable were the activities with the child (1 = “not enjoyable”, to 5 = “very enjoyable”). The final score was a mean response from the two questions. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .58 to .64 across cohorts.

Praise was measured through the Parent Major Interview (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990), in which parents were asked to rate how often they praised their child for doing a good job (1 = “never, almost never” to 4 = “often”).

Inappropriate discipline was measured through the Parent Major Interview (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990) and consisted of a sum of inappropriate discipline techniques (e.g., “raise voice”, “yell”, “slap”, “spank”) used in different scenarios (e.g., “the child argued or talked back”, “the child hit another child”, “the child lied about breaking a household object”). Parents were able to specify two discipline techniques for each question. A lower score indicated that more appropriate discipline was used. Cronbach’s alphas were not calculated for this variable as the score was a sum of items that are not necessarily correlated with one another.

Inconsistent discipline was measured through the Parent Major Interview (Oregon Social Learning Center, 1990) and was a Likert scaled score of 11 items that reflected inconsistent discipline. The items included questions such as “How often does child get away with things you feel the child should have been punished for?”; “If you have asked the child to do something, how often do you give up trying to get him/her to do it”. Parents rated each item as 1 = “never”, to 5 = “always”. The final score was a mean response from the 11 questions. Higher numbers reflected more inconsistent discipline. The measure demonstrated adequate reliability with alphas ranging from .71 to .79 across cohorts.

Child outcomes

Two child outcomes were examined for this study: child problem behavior (which was assessed at three time points, 5th, 8th, and 10th grades) and serious youth delinquency (which was assessed at 10th grade). Child problem behavior was measured via the externalizing behavior scale on the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991). This scale includes two subscales, aggressive behavior and delinquent behavior, in which parents and teachers are asked to rate the child on 30 antisocial behaviors (e.g., child “argues a lot”, “destroys things”, “physically attacks people”). Parents and teachers rated each item as 0 = “not true” to 2 = “very true”. Cronbach’s alphas for this study ranged from .89 to .96 across the different ages. Both mother and father reports (r = .46 to .61) as well as parent and teacher reports (r = .33 to .46) were highly correlated across waves. At each grade level, the child’s problem behavior score consisted of the mean response from the child’s mother, father, and teacher at that specific grade. Serious youth delinquency was assessed when the youth were in the 10th grade through ratings on the subscale of major offenses in the Elliot Delinquency Scale (Elliott, 1983). With this instrument, the youth indicated their involvement in 11 serious antisocial behaviors over the past year behaviors (e.g., “used force to rob a person, store, bank, or business”; “sold hard drugs”; “raped someone”). This amount was recoded into categories from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “over 15 times”. The final score was the sum of responses to the 11 questions. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .67 to .68 across cohorts.

Analytic Strategy

All data were cleaned and, when appropriate, checked for univariate normality. Descriptive summary statistics were calculated for all variables of interest. Bivariate analyses were then completed that examined differences between youth who had experienced parental incarceration during childhood with those who had not. The differences between the groups were evaluated using chi-square (χ2) test of independence (for the categorical items), Mann-Whitney U test (for the categorical, ordered items), or an independent t-test (for the continuous items). The Levene’s test was used to evaluate the variance of each group in the independent t-test to determine the appropriate t-values to use in assessing the results. For all significant results, a corresponding effect size statistic was calculated. Depending on the specific test, Cramer’s V, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), or Cohen’s d were used to evaluate the size of the effect. Qualitative descriptions of the relative size of the effects were noted using Gravetter and Wallnau’s (2004) criteria for Cramer’s V (small = .01, medium = .30, and large = .50), and Cohen’s (1992) criteria for r (small = .10, medium = .30 and large = .50) and d (small = .20, medium = .50, and large = .80).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

In this study, twenty-one adolescents had a mother who had been incarcerated, and fifty-three had a father who had been incarcerated. Because seven of the adolescents had both a mother and a father who had been incarcerated, 67 out of 655 (10.2%) youth had at least one parent incarcerated during their childhood. The majority of the mothers and fathers in families who had an incarcerated parent were Caucasian (84% of fathers, 92% of mothers), reflecting the general demographics of the region at the beginning of the study.

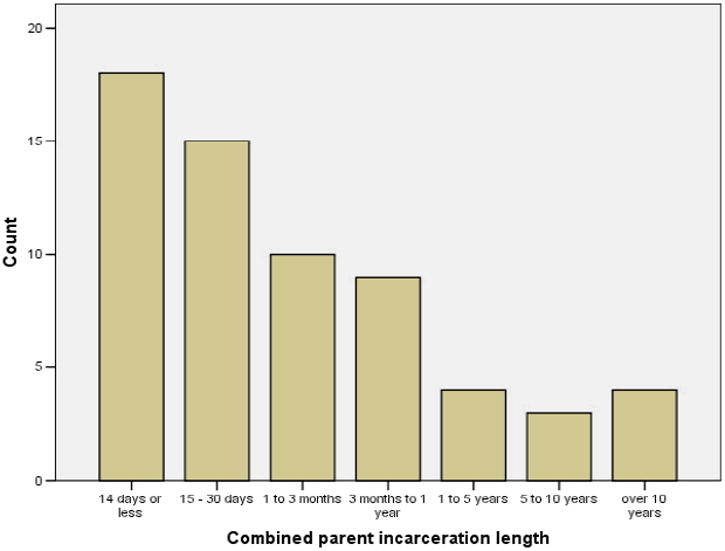

The ages of the children when a parent was incarcerated ranged from 0 to 10.5 years with a mean of 4.78 (SD = 3.07). The length of the parents’ incarceration ranged from 1 day to 22.5 years with a mean of 1.65 years (SD = 4.45). While all the incarcerations began during the child’s first 10 years, the sample includes parents who were incarcerated for shorter as well as longer durations (see Figure 1). Most (82.5%) of the incarcerations were a year or less. The average incarceration length for mothers (M = .84 years, SD = 2.79) was roughly half of the average incarceration length for fathers’ (M = 1.76 years, SD = 4.67).

Figure 1.

Length of Time Parent Incarcerated

The majority of parents of the youth with a history of parental incarceration had a high school education or less (67.4% of fathers, 59.7% of mothers). Very few of the parents had a college degree (4.3% of fathers, 6.5% of mothers), although roughly a third of mothers and fathers had some college. The majority of parents were employed in occupations that required less formal education (85.4% of fathers, 81.0% of mothers). While the majority of mothers and fathers worked at least part-time (91.3% of fathers, 69.3 % of mothers), many families were also in or near poverty. Three quarters of the families with a history of parental incarceration had household incomes less than $30,000/year, a third of the families with an incarcerated parent had incomes less than $15,000/year (roughly the poverty line for a family of four during this period), and half of the families received financial assistance of some sort. The type of family in which children with incarcerated parents lived was evenly split across categories with 37.3% living in a two parent biological or adopted family, 34.3% living in a two parent step family, and 28.4% living in a single parent household (a majority with a single mother).

Bivariate Analyses

Bivariate analyses revealed several significant differences between youth who had experienced parental incarceration during childhood versus those who had not (see Tables 1 and 2). In terms of family social advantage, the parents in families with a history of parental incarceration had less education, worked fewer hours, had less household income, received more financial assistance and had a lower overall SES than parents in families without such a history. The magnitude of these differences ranged from small to large; however, the majority of effect sizes fell within the moderate range.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Parents in Families with an Incarcerated Parent when Children are in the 5th Grade

| Variable | % in Families with Inmate Parents (n = 67) | % in Families without Inmate Parents (n = 588) | Test Statistic | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father’s Education | |||||

| < HS | 30.4 | 10.7 | U = 6326, z = -4.29 | < .001 | r = -.19 |

| HS | 37.0 | 30.9 | |||

| Some college | 28.3 | 35.7 | |||

| College graduate/Post | 4.3 | 22.7 | |||

| Mother’s Education | |||||

| < HS | 25.8 | 13.4 | U = 13895, z = -2.73 | .006 | r = -.11 |

| HS | 33.9 | 33.5 | |||

| Some college | 33.9 | 36.7 | |||

| College graduate/Post | 6.5 | 16.4 | |||

| Family Income | |||||

| <$15,000 | 32.2 | 18.2 | U = 12204, z = -4.63 | < .001 | r= -.18 |

| $15,000 - $29,999 | 43.1 | 30.8 | |||

| $30,000 - $50,000 | 21.6 | 35.3 | |||

| > $50,000 | 3.1 | 15.6 |

Table 2.

Independent T-Test Results Comparing Families with a History of Parental Incarceration during Childhood and Families without a History of Parental Incarceration

| Parental incarceration | No parental incarceration | DF | t | p | Cohen’s d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| Parent SES | ||||||||

| Hours father worked | 32.5 | 26.1 | 41.6 | 16.2 | 462 | -3.26 | .030 | -.42(m/s) |

| Hours mother worked | 23.5 | 22.4 | 22.4 | 18.3 | 597 | .432 | .714 | |

| Father SES | 28.7 | 10.0 | 36.9 | 11.8 | 462 | -4.3 | <.001 | -.75(m/l) |

| Mother SES | 29.8 | 10.4 | 33.7 | 12.7 | 565 | -2.3 | .05 | -.34(s) |

| Sources of financial aid | 49.3 | 74.6 | 649 | 3.75 | <.001 | .54(m) | ||

| Parent Health | ||||||||

| Parent alcohol problems | 0.20 | 0.78 | 0.11 | 0.53 | 601 | 1.16 | .397 | |

| Parent depression | 13.14 | 9.34 | 10.21 | 7.56 | 597 | 2.80 | .021 | .34(m/s) |

| Parent health | 3.02 | 0.62 | 3.23 | 0.62 | 601 | -2.47 | .014 | -.34(m/s) |

| Parenting Strategies | ||||||||

| House rules | 27.91 | 2.17 | 28.01 | 2.16 | 605 | -.35 | .726 | |

| Inconsistent discipline | 2.3 | 0.58 | 2.12 | 0.51 | 607 | 2.69 | .007 | .33(m/s) |

| Inappropriate discipline | 3.13 | 0.95 | 2.79 | 1.02 | 607 | 2.44 | .015 | .34(m/s) |

| Praise | 3.07 | 0.61 | 3.05 | 0.68 | 607 | .26 | .795 | |

| Parent/child relationship | 4.33 | 0.64 | 4.40 | 0.57 | 607 | -.98 | .326 | |

| Parent involvement | 1.62 | 0.33 | 1.60 | 0.33 | 607 | .386 | .700 | |

| Youth Outcomes | ||||||||

| 5th grade externalizing | 8.71 | 5.53 | 7.05 | 6.42 | 637 | 1.99 | .047 | .28(m/s) |

| 8th grade externalizing | 9.98 | 8.24 | 7.43 | 8.26 | 568 | 2.21 | .028 | .31(m/s) |

| 10th grade externalizing | 9.51 | 8.64 | 5.70 | 6.72 | 512 | 3.13 | .003 | .49(m/s) |

| Serious youth delinquency | 0.74 | 1.17 | 0.40 | 0.90 | 538 | 2.56 | .042 | .32(m/s) |

Note. The following qualitative descriptions of the relative size of the effects used Cohen’s (1992) criteria for d (small = .20, medium = .50, and large = .80).

There were no significant differences between families with and without a history of parental incarceration in regards to the number of children in a family and the overall family size. However, a greater percentage of youth with a history of parental incarceration lived in either single parent or stepfamilies than youth who had not experienced parental incarceration. The magnitude of this difference was moderate to small. While there was limited racial and ethnic diversity in the sample, a disproportionate number of African American, Hispanic, Native American children experienced parental incarceration during their first 10 years. Within this sample, 9.1% of Caucasian, 25% of African American, 30% of Native American, and 18.2% of Hispanic children had parents who had been incarcerated.

Several significant differences were found in the parents’ health as well. On average, parents in families with a history of parental incarceration experienced more depression and rated their physical health as worse than parents without a history of parental incarceration. The magnitude of the differences in both depression and health between these two types of families was moderate to small. The study found no significant differences in the number of alcohol problems reported by either group of families.

Parenting strategies were similar between the two types of families with the exception of disciplinary practices. On average, parents from families with an incarcerated parent used inappropriate discipline and inconsistent practices more frequently than parents from families without incarcerated parents. The magnitude of this difference was moderate to small for both practices. In all other aspects of parenting the differences between the two groups were not significant.

The final area examined was youth adjustment, where, once again, significant differences were found. Adolescents with a history of parental incarceration consistently had higher levels of problem behaviors between the 5th and 10th grades. The magnitude of this difference of means was moderate to small across all three grades, however, the strength of this association increased slightly over time. Serious delinquency in the 10th grade was also higher for adolescents with a history of parental incarceration than for adolescents without this history. The magnitude of this difference was also in the small to moderate range.

Discussion

Similar to findings from earlier studies (Glaze & Maruschak, 2009; Murray et al., 2009; Poehlmann, 2005), youth in this sample with a history of parental incarceration were not only more likely than other youth to be exposed to many parenting and family risk factors but were also at higher risk for poor adjustment across adolescence. Because the study used population-based data, the study also provides an estimate of overall incidence of parental incarceration in the United States as well as within specific racial and cultural groups. While the processes through which parental incarceration and its associated risks affect youth are unclear, the mounting evidence of both the vulnerability and high incidence of youth with a history of parental incarceration underscores the urgency for an intensified and coordinated research effort to address the current knowledge gaps that still exist about this population. Without this information, our ability to effectively meet the needs of these youth and their families is limited.

Social Interaction Theory highlights the importance of family functioning and parenting in both mediating and moderating the effect of risks on child adjustment. The study calls attention to several difficulties within these two broad areas that youth in families with a history of parental incarceration are more likely to experience than youth without a history of parental incarceration. In terms of family context and functioning, the parents in families with a history of incarceration tended to have less education, to work fewer hours and to be employed in lower level occupations than parents in families without a history of parental incarceration. Not surprisingly, families with an incarceration history also struggled financially, with a majority of the families in or near poverty. Because of the links between low socio-economic status and poor child and family well-being (Knutson et al., 2004; Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, Yeung & Smith, 1998), these challenges are likely to render families with a history of parental incarceration at a marked disadvantage. What is not known from this study is if an existing socioeconomic disadvantage increased the likelihood of parental incarceration, or if the socioeconomic disadvantage was a result of the parent’s incarceration. The research to date would argue that it is a little of both. Numerous studies have identified considerable socio-economic risk in the lives of parents prior to their imprisonment as well as disparities in the numbers of arrested and incarcerated adults based on class and race (Glaze & Maruschak, 2009; Mauer, 2007; Wildeman, 2009). On the other hand, studies have found that incarceration can worsen the financial situation of a family during the incarceration through the loss of family income and increased costs associated with the incarceration such as attorney fees, collect calls, and cash for inmates (Arditti, Lambert-Shute, & Joest, 2003). These financial difficulties can continue after the inmate parent is released when the returning parent may have fewer employment possibilities due to a criminal record and a gap in employment (Bushway, 1998; Petersilia, 2003).

Not only were there differences in terms of social disadvantage, but parents in families with a history of parental incarceration reported being more depressed and having worse physical health than parents in families without an incarceration history. These findings are consistent with other studies, which have found similar health risks in the lives of inmate parents and their partners (Mumola, 2000; Murray & Farrington, 2005; Myers et al., 1999; Poehlmann, 2005). While this study found no significant difference in reports of the number of alcohol-related problems, the measure used in the current study was limited. Parental arrest records for this sample indicate a high rate of involvement in drugs and alcohol, as has been found in other studies focusing on adults involved with the criminal justice system (Dallaire, 2007; Glaze & Maruschak, 2009; Mumola, 2000). Substance use needs to be examined more fully to understand its association with incarceration, family functioning, parenting, and youth adjustment.

In addition to these differences in family context and functioning, differences were found in parenting where parents in families with a history of incarceration were less likely to use effective parenting strategies. While there were no significant differences between the two types of families in the areas of monitoring, praising, involvement, and the overall quality of the parent-child relationship, the two types of families differed in the use of inconsistent and inappropriate discipline. In families with a history of parental incarceration, the use of inconsistent and inappropriate discipline was, on average, greater than in families who had not experienced parental incarceration. To date, there have been few studies that have looked at parenting differences between families with and without a history of parental incarceration. Murray and Farrington’s study (2005), one of the few to examine this issue, found that youth in families with a history of parental incarceration were more likely to be poorly supervised by their parents and to have a father who used “harsh or erratic” discipline. Because of the link between ineffective discipline techniques and child behavior problems (e.g., Reid, Patterson, & Snyder, 2002), this finding is of particular concern. What might be causing these differences in parenting is unclear from this study. The higher incidence of inconsistent discipline in families with an incarcerated parent may in part be explained by the parents’ involvement in criminality, and the subsequent attention to and consequences of that criminality. Inappropriate discipline may reflect parental strain where normal irritations may more often lead to an escalation of anger, frustration, and overreaction to a child’s behavior. These two aspects of parenting and their relationship to parental incarceration need to be examined as they might be crucial pieces to address in any program working to improve parenting skills among families with an incarcerated parent.

While causal relationships cannot be determined from this study due to the nature of the analyses, the study highlights associations between family functioning and parenting with youth problem behavior in 5th, 8th, and 10 grades. The higher rates of problem behaviors and serious delinquency for the children of incarcerated parents which were revealed in this study are consistent with other earlier studies (Kinner, Alati, Najman, & Williams, 2007; Murray et al., 2009). The current study found not only higher levels of problem behaviors and serious delinquency for the youth across adolescence, but that the association between parental incarceration and problem behaviors strengthened slightly over time. This slight increase in the risk of antisocial behavior across adolescence was seen in Murray and Farrington’s study (2005) as well. Again, however, what is unclear from either study is how parental incarceration is specifically linked to these higher levels of problem behaviors and serious delinquency, which appear to increase over adolescence. Because the parental incarceration preceded the assessment of the family and parenting variables, which in turn preceded the assessment of the later adolescent outcomes, there is reason to believe parental incarceration may be influencing the subsequent family and parenting which may be influencing later youth outcomes. Such an increase in problem behaviors across time could indicate a decreasing influence of childhood protective factors (i.e. parenting as suggested in the Social Interaction Learning Theory) or a maturational process whereby stresses are asymptomatic earlier in child development but give rise to more problems in later adolescent development. Further studies need to examine this, more vigorously, particularly the specific processes prior to, during, and/or after parental incarceration that may account for these ongoing and intensifying relationships across development.

While our knowledge is growing about children who have parents who have been incarcerated, we still do not have many estimates of the number of children in the United States who experience parental incarceration across their childhood. Within the LIFT study area, 10.3% of the children had experienced parental incarceration during the first 10 years of their lives. Not surprising, this rate is substantially higher than cross-sectional estimates of 2.3% of children with an incarcerated parent (Glaze & Maruschak, 2009). This incidence of parental incarceration in the current study was also substantially higher than the 5.6% rate that Murray and Farrington’s (2005) found in their U.K. study, although Murray’s study, in addition to occurring in a different country, followed a cohort from a much earlier period (men born in the 1950’s). However, this rate is remarkably close to our rough estimate of the incidence of children who have experienced parental incarceration (11%) mentioned in the opening of the paper; an estimate based partially on less precise statistics.

When broken down by racial and ethnic background, the current study revealed a disproportionate amount of children from African American, Native American, and Hispanic backgrounds had experienced parental incarceration during their first 10 years. In this study, 9.1% for Caucasian, 25% of African American, 30% for Native American, and 18.2% for Hispanic children experienced parental incarceration during their childhood. This overrepresentation of minority parents who have been imprisoned is similar to Johnson’s findings (2009) who found 10.1% of Caucasian and 18.7% of African American children experienced parental incarceration by the time the children were 18 years. This overrepresentation is also found in the general population at large, where African American, Hispanic, and Native American parents are at elevated risk for incarceration compared to their representation in the population at large (Bonczar, 2003; Mumola, 2000). While the disparities in incarceration in part reflect different crime rates, they may also be indicative of disparities in criminal justice processing and decision making which has been known to discriminate against racial minorities through such practices as racial profiling, harsher sentencing, inaccessibility to legal counsel, and inaccessibility to quality representation (Mauer, 2007). If parental incarceration increases the likelihood for negative outcomes for children, then the disproportionate amounts of parental incarceration within African American, Native American, and Hispanic communities may become a mechanism that further exacerbates racial disparities experienced by these communities.

While this study has many strengths, there are two major limitations. The first centers on characteristics of the sample and possible limitations in generalizability. The data were collected from mostly Caucasian children and families who lived in a moderately sized urban area in the Pacific Northwest. It is unclear whether and to what degree the findings here are relevant to other populations in other geographic areas at different historical times. The second limitation has to do with the lack of measurement complexity surrounding the variable of parental incarceration. The variable did not capture the many differences within an incarceration experience including such elements as the frequency and length of the incarceration, the specific age of the child at the time of incarceration, nor the level of disruption the incarceration caused. Additional research needs to focus on these specific aspects of parental incarceration, and examine what impact each has on youth.

Despite these limitations, these findings provide valuable information for service providers and policy makers alike. First, this study provides a more accurate estimate of the number of youth, both overall and by race and ethnicity, who have experienced parental incarceration during childhood. While this number is from a specific region, it is a start in estimating the actual incidence of parental incarceration within the United States. Second, the study highlights the many challenges that adolescents in families with a history of parental incarceration face in the areas of family social advantage, parent health, and effective parenting. The connections between depleted financial resources, depression, ineffective parenting and poor outcomes for children have been well documented in research on the general population (e.g. Grant, Compas, Stuhlmacher, Thurm, McMahon, & Halpert, 2003). The findings here suggest that the connections between family, parenting and youth adjustment are noteworthy for adolescents with a history of parental incarceration. The mounting evidence suggests that not only are many children affected by parental incarceration, but they and their families have multiple needs. The breadth and depth of problems suggest a need for comprehensive, multilevel policy and practice approaches to address the multiple family challenges that the children of incarcerated parents face (e.g., Eddy, Kjellstrand, Martinez, & Newton, 2010). These strategies should focus not only on the youth, but also on the financial hardship, educational and occupational disadvantage, poor health, and parenting issues that their families’ experience.

In light of the growing number of incarcerated parents and the detrimental effects that their incarceration and its associated risks are likely to have on youth and families, we must continue to build a broad empirical foundation so we can learn how to better help these children and families. With an over-representation in the correctional system of people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and minority communities, and the possible role that parental incarceration may play in exacerbating racial and social disparities, the situation becomes even more urgent. Incarceration has a role in addressing criminality, but if we do not clearly understand its broader implications, we may inadvertently create a system that increases disadvantage for millions of youth whose only crime is to have been born into a family with an incarcerated parent.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was provided by Grant R01 MH 65553 from the Prevention and Behavioral Medicine Research Branch, Division of Epidemiology and Services Research, NIMH, NIH, U. S. PHS and Grant R01 MH 054248 from Prevention Research Branch, NIDA, NIH, U.S. PHS. This paper includes work done as part of the dissertation of Dr. Jean M. Kjellstrand within the School of Social Work at Portland State University (Oregon). We would like to express our deep appreciation and thanks to the Bethel, 4J, and Springfield school district personnel, principals, and teachers; and to the participating LIFT youth and their families for sharing their lives with us. We are also especially thankful to Dr. John B. Reid, Becky Fetrow, Kathy Jordan, Alice Holmes, Diana Strand, and all the other LIFT scientists and staff members who have worked on this project over the years. Dr. Kjellstrand is extremely grateful to her dissertation chair, Dr. Eileen Brennan, and the rest of her dissertation committee, for their helpful feedback, guidance, and comments on her dissertation.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman BP, Brown ED, Izard CE. The relations between contextual risk, earned income, and the school adjustment of children from economically disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(2):204–216. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditti JA, Lambert-Shute J, Joest K. Saturday morning at the jail: Implications of incarceration for families and children. Family Relations. 2003;52(3):195–204. Article. [Google Scholar]

- Bonczar TP United States Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prevalence of imprisonment in the U.S. population, 1974-2001. 2003 from http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS62432.

- Bushway SD. The impact of an arrest on the job stability of young White American men. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1998;35(4):454–479. [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(5):746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire DH. Incarcerated mothers and fathers: A comparison of risks for children and families. Family Relations. 2007;56:440–453. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Yeung WJ, Smith JR. How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Chamberlain P. Family management and deviant peer association as mediators of the impact of treatment condition on youth antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(5):857–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Kjellstrand J, Martinez CR, Jr, Newton R. Theory-based multimodal parenting intervention for incarcerated parents and their families. In: Eddy JM, Poehlmann J, editors. Multidisciplinary perspectives on children of incarcerated parents. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2010. pp. 237–261. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS. Interview schedule, National Youth Survey. Boulder, CO: Behavioral Research Institute; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Jolliffe D, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Kalb LM. The concentration of offenders in families, and family criminality in the prediction of boys’ delinquency. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24(5):579–596. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Weih S. House rules: A measure of parental monitoring. 1990. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Glaze LE, Maruschak LM. Parents in prison and their minor children. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2009. Special Report No NCJ 222984. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(3):447–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter FJ, Wallnau LB. Statistics for the behavioral sciences. 6. Belmont, CA: Wadworth; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. Effects of parental incarceration. In: Gabel K, Johnson D, editors. Children of incarcerated parents. New York: Lexington Books; 1995. pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. Ever-increasing levels of parental incarceration and the consequences for children. In: Raphael S, Stoll M, editors. Do prisons make us safer? The benefits and costs of the prison boom. New York: Russell Sage; 2009. pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kinner S, Alati R, Najman JM, Williams GM. Do paternal arrest and imprisonment lead to child behavior problems and substance use? A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Child Psychology. 2007;48(11):1148–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson JF, Degarmo DS, Reid JB. Social disadvantage and neglectful parenting as precursors to the development of antisocial and aggressive child behavior: Testing a theoretical model. Aggressive Behavior. 2004;30(3):187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious & violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh VH, Myers BJ, Kennon SS. Children of incarcerated mothers and their caregivers: Factors affecting the quality of their relationship. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15(5):581–596. [Google Scholar]

- Mauer M. Racial impact statements as a means of reducing unwarranted sentencing disparities. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. 2007;5(19):19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ. Incarcerated parents and their children. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Justice; 2000. Special Report No NCJ 182335. [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ. Incarcerated parents and their children; Paper presented at the National Center for Children and Families colloquium, Overcoming the Hidden Costs of Incarceration on Urban Children; Washington, DC. 2002. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington DP. Parental imprisonment: Effects on boys’ antisocial behavior and delinquency through the life-course. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2005;46(12):1269–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge; 2006. Parental imprisonment: Effects on children’s antisocial behaviour and mental health through the life-course. [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington DP, Sekol I, Olsen RF. Effects of parental imprisonment on child antisocial behaviour and mental health: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2009. 2009;4 Available at http://campbellcollaboration.org/lib/

- Myers BJ, Smarsh TM, Amlund-Hagen K, Kennon S. Children of incarcerated mothers. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 1999;8(1):11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Social Learning Center. Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers Investigation. Unpublished instruments; Eugene, OR: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44(2):329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry MJ, Mackun PJ. Population change and distribution: Census 2000 brief. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Commerce; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Petersilia J. When prisoners come home. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. Children’s family environments and intellectual outcomes during maternal incarceration. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2005;67(5):1275–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reed DF, Reed EL. Children of incarcerated parents. Social Justice. 1997;24(3):152–169. [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Eddy JM, Fetrow RA, Stoolmiller M. Description and immediate impacts of a preventive intervention for conduct problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(4):483–517. doi: 10.1023/A:1022181111368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder J. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:55–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis J, Waul M. Prisoners once removed: The children and families of prisoners. In: Travis J, Waul M, editors. Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families, and communities. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Justice. Correctional populations. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C. Parental imprisonment, the prison boom, and the concentration of childhood disadvantage. Demography. 2009;46(2):265–280. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]