Abstract

The Color of My Skin is an instrument developed to assess children’s internalized idea (abstraction) of the color of their skin; their satisfaction with that color; the desire, if any, to change the color of their skin; and their affect regarding their skin color. The assessment is part of a questionnaire utilized in a 3-year longitudinal study that examines psychosocial development, physical health, and behavioral adjustment of Puerto Rican children (N = 257) reared in the Greater Boston area. The results demonstrate that children’s internalized representation of their skin color is a construct that can be reliably and validly measured. The children’s ratings of their skin color were not associated with their sex, school grade, ethnic identity, the child’s or the parent’s nativity, or the racial or ethnic compositions of 3 social contexts: their neighborhood, their classmates, and their closest friends. Puerto Rican children did not show a preference for light-colored skin. Moreover, there were no significant differences in self-esteem based on the child’s self-reported skin color. The lack of association between self-esteem and skin color was interpreted in light of a developmental tendency prevalent in early to middle childhood to place a positive value on different aspects of one’s self. Whereas almost all children (96%) reported being happy or very happy with their color, 16% of the children would like to change their skin color if they could (51% to a lighter and 46% to a darker color).

The Color of My Skin is an instrument developed to assess children’s internalized idea (abstraction) of the color of their skin; satisfaction with that color; desire, if any, to change the color of their skin; and their affect regarding their skin color. The assessment is part of a questionnaire utilized in a 3-year longitudinal study that examines psychosocial development, physical health, and behavioral adjustment of Puerto Rican children raised in the greater Boston area. The study has a normative focus with a special interest in studying the effects of migration, prejudice, and discrimination on the development of Puerto Rican children raised in the mainland (see Alarcón, Erkut, García Coll, & Vázquez Garcia, 1994).

The research question that has guided the focus on skin color is whether children’s internalized representation of their skin color is a construct that can be reliably and validly measured. If so, the study will test two hypotheses: (a) Puerto Rican children prefer light skin colors, and (b) there is no relation between children’s perceptions of their skin color and their self-esteem.

The Issue of Skin Color for Puerto Ricans

We are interested in studying skin color as an aspect of mainland Puerto Rican children’s normative development because growing up as immigrants, or as the children of immigrants, these children are potentially exposed to two different cultural systems regarding skin color. Because the implications of color assignment can be different in their household culture and the larger mainland culture in which they are growing up, we need a tool to examine how these children construct their skin color and what is their affect toward that construction.

Although Puerto Ricans are native-born Americans, they become a minority by virtue of their color, culture, and language when they settle on the mainland. Similar to other immigrants, they face the challenges of acculturation and learning English to make their way in the mainstream Anglo society. Moreover, because they come from a culture that recognizes a spectrum of color or racial types, they need to come to terms with the racial or ethnic system that operates on the mainland of the United States.

The spectrum of color or racial types of Puerto Ricans includes blancos, the equivalent of Whites; indios, with dark skin and straight hair; morenos, dark skinned with a mix of features including Negroid and Caucasian; trigueños, often considered brunettes on the mainland, but also a term applied to dark-skinned people who have high social status; and finally, negros, who are dark skinned with Negroid features (Rodriguez, 1995). This spectrum of racial types is further complicated by the fact that racial classifications are based not only on skin color, facial features, and texture of hair, but also on social class and behavior (Rodriguez, 1995). Racial implications have to do with both the color words associated with race and also with the higher value attached to lighter skin color that exists in Puerto Rico (Rodriguez, 1995). However, race and color prejudice are not as pronounced on the island as they are on the mainland (Fitzpatrick, 1987). The designation of a person as White, or Black, or trigueño for Puerto Ricans is a characteristic of that individual and the individual’s culture-based behaviors and social class (Fitzpatrick, 1987), but not so much of only the individual’s ancestry, that is, the “one-drop rule.” As Comas-Díaz (1989) summarized: “Puerto Ricans have been called the ‘rainbow people,’ denoting their wide variations of color, ranging from Black to White within Puerto Rican families. Thus, racism in Puerto Rico is covert and does not have implications for genetic inferiority” (p. 182).

In the contiguous United States, the changing sociopolitical construction of race has its roots in the racial distinction between White and non-White (see Hirschfeld, 1996). Even though the non-White designation includes people of Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American ancestry, and many Spanish-speaking groups, the non-White category has historically referred generally to African Americans or Blacks (Davis, 1991; Hirschfeld, 1996; Rothbart & Taylor, 1992). This dichotomous distinction—that is, the designation of a person as either White or non-White—is not so much determined by physical characteristics or socioeconomic status as it is by racial ancestry (Davis, 1991). Hirschfeld (1996) noted that on the mainland both adults and school-aged children understand the one-drop rule that defines a person as non-White on the basis of having even a remote African ancestor.

In Puerto Rico, one’s color is a cultural designation that has racial implications. On the mainland, race is an ancestry-based designation that has color implications. The sociopolitical constructions of race on the mainland are, by and large, defined by a dichotomous distinction between White and non-White, which places most Puerto Ricans into the non-White category due to their mixed ancestry. Many Puerto Rican adults are reluctant to accept a dichotomous system where they are classified as non-White both because it negates Puerto Rican’s culture, language, and its socially constructed color heterogeneity, and also because of the extent of prejudice against non-Whites that permeates mainstream social institutions.

Rodriguez (1995) suggested that when people think of themselves as Puerto Rican and are suddenly only perceived as “people of color,” a perceptual dissonance in self-image can arise. As Fitzpatrick (1987) suggested, nothing is so complicating to the Puerto Ricans in their effort to adjust to American life as the problem of color.

The two contrasting systems of color previously discussed—the one operating in Puerto Rico and the one operating on the mainland—have been described primarily from the perspectives of adults. We acknowledge that individuals and some families may not subscribe to the color system associated with their culture group. However, even for children of Puerto Rican parents who do not subscribe to either color system, we believe that the larger Puerto Rican and mainland communities’ dual sociocultural influences will provide the social context of their development. There is a need for an instrument to document the implications of growing up exposed to these two contrasting systems. The measurement of Puerto Rican children’s internal concept of their skin color and their affect toward it is an important developmental topic that needs to be studied.

Skin Color and Affect

Most research on the relation between self-perceived skin color, skin color preference, and affect toward skin color was a component of studies of racial identity and prejudice among children (Clark & Clark, 1947; Goodman, 1952; Harvey, 1995; Horowitz, 1939; Phinney, 1990; Porter, 1991; Robinson & Ward, 1995; Spencer & Horowitz, 1973). In Cross’s (1991) discussion of the Clarks’s (Clark & Clark, 1947) and Horowitz’s (Horowitz, 1939) early research, he pointed out that the preference for light skin color these researchers observed was mistakenly interpreted as evidence for low self-esteem. He argued that later research (e.g., Beuf, 1977; Powell, 1985; Spencer, 1984) demonstrated that a pro- White choice, observed in some dark-skinned children, is not necessarily associated with low self-esteem. Rather, it is an indication that minority children are aware of mainstream society’s preference for lighter skin color. Spencer and Markstrom-Adams (1990), in their synthesis of the literature related to identity processes among American ethnic and racial minority children, noted that “African American children’s pro- White racial attitude and preference patterns appear to represent cultural–ecological variables (i.e., negative stereotypes about Blacks) and not psychological characteristics” (p. 296).

Research on skin color preference of Latinos is not abundant. On the whole, it tends to affirm that Puerto Ricans and Mexicans prefer lighter skin colors and that they tend to assimilate greater society’s values and attitudes associated with race and skin color (Boswick, 1973; Cota Robles de Suárez, 1971; Gimelli, 1978). Rodriguez (1995) speculated that Puerto Ricans might think they have a darker skin color than they actually do and suggests that this might reflect their internalization of the label “non-White” utilized in the mainland.

Based on the recent studies on African Americans and the available literature on Hispanics, we hypothesize that mainland Puerto Rican children will also demonstrate a preference for light skin colors, but that this preference will not be associated with low self-esteem.

The Need for a New Instrument

As Aboud (1988) pointed out, most instruments that pertain to children’s color preference were designed to measure either prejudice or ethnic awareness and identification. Prejudice has been assessed in three different ways: First, there is the forced-choice format of Clark and Clark (1947) developed in the 1930s and 1940s for Black American children, which included seven items, four of which measured attitudes. The children were shown a black doll (sometimes a brown one) and a white doll and were asked: “Which would you like to play with? Which is the good doll? Which has a nice color?” This technique has been modified and widely used by different investigators (Beuf, 1977; Goodman, 1952; Spencer, 1984). Second, attitudes were assessed by way of the multiple-item tests of Williams, Best, and Boswell (1975), known as Preschool Racial Attitude Measure, and the Katz–Zalk Projective Prejudice Test (Katz & Zalk, 1978). In these instruments the child is shown a picture of two persons, one with light and another with dark skin, and is asked to label them in different scenarios as being good or bad. Again, these have been modified and used widely (Clark, Hocevar, & Dembo, 1980; Johnson, 1992; Neto & Paiva, 1998). Third, instruments that use continuous rating scales that provide many response alternatives (rather than two) have been used. For example, a child is asked how much he or she likes a person or how close he or she would sit next to them (Aboud, 1981; Aboud & Mitchell, 1977; Verna, 1981).

Similarly, ethnic awareness and identification have been measured in a variety of ways: (a) by assessing recognition or identification—in other words, having the child recognize the person that belongs to a group by simply asking him or her to point to the person that belongs to a group (Black, White, Asian, Native American, Hispanic); (b) by measuring perceived similarities and dissimilarities (Aboud & Christian, 1979; Aboud & Mitchell, 1977; Genesee, Tucker, & Lambert, 1978); and (c) by having a child categorize persons that belong together (Vaughn, 1963).

None of these instruments, however, serve our purpose of identifying a child’s internal construction of his or her skin color and the affect associated with it as a psychological characteristic. Closer to our goal of studying internal construction is Cota-Robles de Suárez’s (1971) study of skin color as a factor of racial identification and preference among young Chicano children. She studied Chicano preschool children’s awareness of their skin color with a coloring task using a wide range of colored crayons that included nonskin color tones such as green or red. We have judged the inclusion of the nonskin color tones among the color stimuli to be confusing to the children and decided to use a measure that presents only skin tones as stimuli.

Holmes (1995) carried out a study that used skin color as a factor of racial identification. She used participant observation techniques, supplemented by a taped interview where she obtained spontaneous data from children stating what color their skin is and how they feel about it. This methodology, however, is very time consuming and needs trained observers with an ethnographic or anthropological background, which makes it difficult to use with a large sample.

Methods

Construction of the Measure

The measure was designed to evaluate children’s (a) internalized idea (abstraction) of the color of their skin; (b) satisfaction with that color; (c) desire, if any, to change the color of their skin; and (d) their affect regarding their skin color.

Development of the Color of My Skin measure began with the piloting of a variety of ways of representing color as described in the following. The data for the validation study reported comes from the third wave of data collection as it was in the third wave that we obtained the interviewers’ external assessment of the children’s skin color to examine concurrent validity.

The measure was created simultaneously in English and Spanish utilizing the dual-focus technique developed by the research team (Erkut, Alarcón, García Coll, Tropp, & Vázquez, 1999). In this technique, a team of monolingual and bilingual researchers selected the constructs to be measured, keeping in mind conceptual equivalencies of the cultures being studied. They developed the questions to be asked in both languages simultaneously, paying attention to the difficulty, affect, clarity, and purity of both languages. The questions were then evaluated by successive focus groups that provided feedback for revisions. The instrument was completed when the last focus group and the research team reached a consensus that the measure was conceptually and linguistically equivalent. The measure was then field tested in both languages to assess its psychometric qualities. A good example of the use of this method is the adaptation of one of Harter and Pike’s (1984) items measuring physical competence which reads: “I am good at running,” which in a literal translation would become the awkward phrase “Yo soy bueno corriendo.” We changed it into “Yo corro bien,” which in English translated to “I run well.” Then we had to ask ourselves what “well” means in early to middle childhood. Is it speed, endurance, or style? We took into consideration the developmental stage of the children in the sample and came up with “I run fast,” which translated to “Yo corro rápido.” Thus the original “I am good at running” became “I run fast,” which is developmentally appropriate for assessing physical competence and is correct and meaningful in both languages. Compared with the commonly used back-translation method, this method has the advantage of being both concept- and language-driven. Thus, it reflects the subtleties of both languages and the conceptual purity of both cultures, rather than using the English version as the standard and then translating and adapting it to Spanish.

Two challenges were encountered in constructing the measure. The first had to do with the physical materials used to depict skin color. We began by asking children to color in a blank face using Crayola’s multicultural crayon set (Binney and Smith, Easton, PA) to match their own skin color. Immediately we ran into the problem that the shade of the color would vary, depending on the pressure a child put on the crayon. We tried to use house paint and then cosmetics color chips but gave up on both of them because the colors looked too artificial. After many focus group trials, we settled on a set of color cards designed to depict multiple skin tones ranging from white to black with many different shades of brown in between. These color stimulus cards were made from paper stock called “People Color” developed by Lakeshore of California and offered more realistic-looking colors.1 The cards were 4 in. long × 3 in. wide.

The second challenge was obtaining the children’s inner image of their skin color. Initially we tested a set of 10 to 12 different cards with shades from white to black in focus groups. The three focus groups consisted of 10 children each. They were Hispanic children not included in the study sample, mainly of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent. The variety of choices available seemed to entice children to attempt matching their actual skin color to the cards rather than projecting the abstraction they had of their skin color.

Next, we asked the children to pick one card that fit best into the skin color categories “white (bianco),” “light brown (trigueño),” “brown (moreno claro),” “dark brown (moreno),” and “black (negro).” We then selected the cards that were chosen most frequently for each of the five categories and assigned them their corresponding label. Therefore, the color distance between each card is not uniform. It has to be noted that the “white” card chosen by the children was a pink-cream-white card and that the “black” card was a brown–black color. In this article white will refer to the pink-cream-white color the children chose and black will refer to the brown-black color they chose. Giving children only these five options (chosen by the focus groups)—white, light brown, medium brown, dark brown, and black—and not allowing them to hold the cards against any part of their body to compare, led them to choose a color that we believe is the internalized color of their skin. The final form of the measure consists of 13 items, incorporating 3 closed- and 10 open-ended questions (see Appendix for the complete measure). It is easy to administer; it takes 3 to 5 min to answer, and the children reported enjoying it.

To obtain an independent assessment of the child’s skin color, the interviewers were asked to record the number of the card which, in their view, corresponded to the child’s skin color before the child had given his or her answer. Interviewers were given specific training for the external assessment of skin color. Each interviewer was trained to a criterion of 90% agreement with two experts on the research team that developed the measure.

Sample

The sample is composed of 257 Puerto Rican children who participated in the third wave of data collection for a longitudinal study of health and growth in 1998. The children (127 girls and 130 boys) lived in the greater Boston area. The majority of them were in the third to fifth grade (see Table 1) with a mean age of 9.6 years. The criteria for selection for the study were the child’s self-identification as Puerto Rican, as having at least one parent who was born in Puerto Rico, or both. Both the child and his or her primary caregiver were interviewed for the study. The caregivers provided the information on the child’s family background. They were paid $10 for their time and the children received an age-appropriate book. The recruitment was done in public elementary schools, parochial schools, community health centers, colleges, and professional organizations. Flyers were distributed at different community locations. Informational flyers with prepaid return envelopes were distributed to several of the aforementioned locations. Interviewers who had been engaged in the recruitment process also utilized word-of-mouth and door-to-door recruitment. The recruitment effort yielded a sample of 291 families. We experienced minimal attrition over the 3 years of data collection: 7% between Wave 1 and 2, and 5% between Wave 2 and 3 (Erkut, García Coll, & Alarcón, 1999). Therefore, we have reasonable confidence that the third-wave sample of 257 families has not been biased due to selective attrition.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Puerto Rican Children and Their Familiesa

| n | % | M Age | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Boys | 130 | 9.7 | 1.11 | 8 | 12 | |

| Girls | 127 | 9.5 | 1.05 | 8 | 12 | |

| Grade in School | ||||||

| Second | 7 | 2.7 | ||||

| Third | 84 | 32.9 | ||||

| Fourth | 75 | 29.4 | ||||

| Fifth | 83 | 32.5 | ||||

| Sixth | 6 | 2.4 | ||||

| Born on Mainland | 195 | 75.9 | ||||

| Parents Born in Puerto Rico | ||||||

| Mother | 213 | 82.9 | ||||

| Father | 203 | 79.0 | ||||

| Completed Interview in Spanish | 160 | 62.3 |

N = 257.

The majority of the children were born on the mainland (75.9%), whereas the majority of their mothers and fathers (82.9% and 79%, respectively) were born in Puerto Rico. This may explain the predominance of Spanish as the home language (children reported that 63.1% of parents speak Spanish only with their child) and the fact that 62.3% of the children preferred to answer the questionnaire in Spanish (Table 1).

More than half of the sample, 55.6%, lived in a two-parent home, 42.4% with one parent, almost always a mother,2 and 3% with both parents and another relative. The self-reported income level of the families was quite low (see Table 2), with more than half of the families living on incomes of $19,999 or less. Two thirds of the sample resided in subsidized housing (67.3%) and 44.4% received government economic assistance in the form of Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Social Security Income, or Social Security Disability income.

Table 2.

Economic Characteristics of the Families in the Samplea

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Household Composition | ||

| Two-Parent Homes | 143 | 55.6 |

| Single Mother Homes | 109 | 42.4 |

| Government Assistance | ||

| Receive Welfareb | 114 | 44.4 |

| Receive Food Stamps | 100 | 38.9 |

| Receive WICc | 37 | 14.4 |

| Receive Subsidized Housing | 173 | 67.3 |

| Income Distribution | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 93 | 36.2 |

| $10,000–$ 19,999 | 67 | 26.1 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 40 | 15.6 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 25 | 9.7 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 7 | 2.7 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | 12 | 4.7 |

| $60,000 and Above | 13 | 5.0 |

N = 257.

This indicates Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Social Security income, and Social Security Disability income.

Aid to Women, Infants, and Children.

When asked to identify the child’s race, 39.6% identified their child’s race as a mix of White and Native; 13.2% as a mix of Black and Native; 11.2% as a mix of Black and White; 10.5% as White; and .007% as Black. One fourth of the caregivers (25.5%), however, chose “other” and, when asked to specify, they responded that their child was Puerto Rican, Hispanic, or Latino.

The self-reported racial or ethnic composition of the children’s social networks was predominantly Puerto Rican (41.2%) or Hispanic or Latino (23.0%) with respect to best friends. However, it was only 10.9% Puerto Rican and 18.3% Hispanic or Latino in terms of classmates and 18.7% Puerto Rican and 17.9% Hispanic or Latino in terms of the neighborhood’s racial or ethnic composition. Only 3.9% of the children reported having mostly White best friends, 6.6% mostly White classmates, and 9.3% mostly White neighbors. The majority of the children reported their neighborhood to be made up of a mixture of people from all races (60.7%) and 48.6% said the same thing about their classmate whereas 26.8% reported their best friends to be made up of a mixture of children from all races.

Our sample is similar to the Puerto Rican mainland population in household composition and economic level. The United States Census Current Population Reports (1993) show 58.7% of the mainland Puerto Rican population to be living below the poverty level. In our sample of families, 63.8% of the caregivers report incomes that place them below the poverty level. Given the underreporting bias of self-report data, the slight difference is not critical. Regarding family composition, 55.6% of the children in our sample live with both parents and 42.4% with a single mother. The census data show 51.7% of Puerto Rican children aged 0 to 18 living with both parents and 43.5% with a single mother, which is, again, similar to our sample.

Procedures

The Color of My Skin measure was administered by specially trained bilingual interviewers as part of the face-to-face interview protocol. Before the interview began the interviewer explained the purpose of the study to the caregiver, its procedures, possible risks and benefits, and the measures taken to protect confidentiality. The caregiver was encouraged to ask questions before signing the informed consent form and was given the telephone numbers of the principal investigators for any follow-up questions or concerns. The interview was conducted in the child’s home and in the language chosen by the child. The child was also given an explanation of the study and its procedures in the beginning of the interview.

Before beginning the administration of the measure, the interviewer recorded, without the knowledge of the child, the number of the color card that, according to the child, corresponded to the child’s skin color to obtain an external assessment of the child’s skin color.

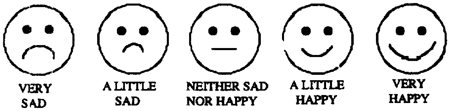

To obtain the children’s perceptions of the color of their skin, each child was presented with a set of five color cards: white (1), light brown (2), brown (3), dark brown (4), and black (5). The children were instructed to pick the card that they thought was most like the color of their skin and were not allowed to match the color cards with any body part. This was done as a further precaution to obtain only the internalized image of the child’s skin color rather than a matched visual perception. This procedure was repeated until the children were comfortable with their choice. Next, the satisfaction with that color was obtained by asking the children how they felt about the skin color with the aid of “happy faces” (see Reynolds, Anderson, & Bartell, 1985). Lastly, children were asked whether they would like to have a different skin color. If they wanted a change, the children were asked what the new choice of color would be. In each instance, reasons were elicited regarding why they liked or disliked the color they chose and why they would like or not like to change skin color if that were feasible. Answers to the open-ended questions were recorded verbatim by the interviewer.

The children’s responses to the open-ended questions of “Why do you like (or not like) having this skin color? ” and “Tell me why you would want (or not want) another skin color” were thematically open-coded (Straus & Corbin, 1990), generating numerous categories for each such as “to be like my family” and “because God made me that way.” Based on the frequencies of the responses, these categories were then reduced to eight. The responses were subsequently double-blind coded using these eight categories; interrater reliability was high (Cohen’s κ=.84). Although there was too little narrative to develop within-child themes, we grouped the children’s responses by choice of skin color (1–5) and by sex to examine if there were any differences across the groups.

Instruments

In addition to the Color of My Skin measure, the children’s interview protocol included a measure of the child’s ethnic identity (Alarcón, 1999), the Puerto Rican Child Self-Esteem Scale (Szalacha, 1997, 1999), Reynolds’ Child Depression Scale (Reynolds et al., 1985), and Helms and Gable’s (1989) School Situation Survey that measures school stresses in such domains as peer interactions, teacher interactions, and academic self-concept. Next we describe the ethnic identity and self-esteem measures, which were developed for this study.

Ethnic identity

We measured children’s ethnic identity by asking them to choose any one or a combination of ethnic identities presented serially (Alarcón, 1999). The first question asks, “Are you Puerto Rican?” If they answer, “Yes,” the children are asked for their rationale as to why they chose that label, whether they are happy about their ethnicity, what they like and do not like about it, and to identify some things they do that correspond to the ethnicity or ethnicities chosen. Next they are asked if they are “Hispanic,” then if they are “American,” and finally if they are from another group, each time with the accompanying questions regarding the reasons for their choice and their satisfaction with it. Therefore, children can choose more than one ethnic identification. Test–retest reliability scores obtained at 1-month interval in a pilot study of 25 Hispanic children yielded a 94% item-by-item agreement in the English version and 93% in the Spanish version of the ethnic-identity questions.

Self-esteem

The self-esteem scale consists of 32 items measuring six different domains of self-esteem: academic, physical skill, friendship, character, responsibility, and behavior (see Szalacha, 1997, 1999). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (always) to 5 (never). The internal consistency estimates for each of the subscales ranges from a Cronbach’s alpha = .62 to .79 with the English and Spanish versions not varying more than .02 for each domain. The internal consistency of the summed scale, as a whole, is estimated to be .88 in the English version and .87 in the Spanish version.

To examine the convergent validity of the self-esteem scale, during the third year of data collection, we took a stratified random subsample (30% of the total sample, n = 78) and concurrently administered Harter’s (1985) Self-Perception Profile for Children. We sampled 20 children in each of four categories, controlling for sex and language preference for the previous two waves of data collection. The estimated validity coefficients between the various subscales of the two measures ranged from .42 to .66.

Finally, to examine the discriminant validity of this new scale, we estimated the relation of self-esteem with two other established measures in the questionnaire: Reynolds’ Child Depression Scale (Reynolds et al., 1985), and Helms and Gable’s (1989) School Situation Survey. We predicted that scores on the self-esteem measure would correlate negatively with both depression and school stresses. As hypothesized, self-esteem was appropriately negatively correlated with child depression (r = −.34, p < .05), with peer interaction stress (r = −.29, p < .001), with teacher interaction stress (r = −.34, p < .05), and with academic negative self-concept (r = −.54, p < .001), thus providing evidence for the discriminant validity of the self-esteem scale.

Results

The results are presented in two parts. The first focuses on the reliability and validity of the children’s internal representation of their skin color as a psychological construct measured by the Color of My Skin instrument, whereas the second contains the substantive findings from the use of the Color of My Skin measure in this sample of Puerto Rican children.

Reliability and Validity

Test–retest reliability

The Color of My Skin measure was pilot-tested in a sample of 25 children of different Hispanic backgrounds (Puerto Rican, Dominican, Central American, mixed Puerto Rican and Dominican) who were retested after 1 month. The children ranged from 6 to 12 years of age. Thirteen children completed the interview in Spanish, and 12 in English. The item-by-item analysis of the test–retest data yielded a 95% agreement in responses in the Spanish version and a 98% agreement in the English version.

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity is the distinctiveness of constructs demonstrated by the divergence of methods designed to measure different constructs (Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991). It was analyzed by examining whether the measure does or does not document distinctions where none are predicted. We predicted no relations between Puerto Rican children’s skin color choice and their sex, their school grade, their place of birth, or their parents’ place of birth. The contingency table analyses examining the independence of the choice of skin color and the children’s sex, χ2(3, N = 257) = 7.49, p > .05, their school grade, χ2(12, N = 257) = 11.34, p > .05, their nativity (born in Puerto Rico or mainland United States), χ2(3, N = 257) = 3.11, p > .05, and their parents’ nativity (born in Puerto Rico, mainland United States, or elsewhere), χ2(6, N = 257) = 11.37, p > .05, are not statistically significant at the .05 level. They confirm that the measure does not yield discriminations where none were expected.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity—how well different measures of the same or related constructs agree—was examined with respect to both the interviewers’ external identification of the children’s skin color and the caregivers’ identification of the child’s race. We predicted a moderate-to-strong correlation between the interviewers’ and the children’s assessments because both refer to the children’s skin color. However, we did not predict a perfect correlation because the interviewers, having been trained to criterion level, were assessing what they saw, whereas the children were identifying their internal representation of their skin color. The estimated correlation of .71 confirmed our prediction of a moderately strong correlation. It should be noted that there were eight interviewers in the study whose own skin colors ranged from 1 (white) to 4 (dark brown). We found no systematic differences among interviewers’ color identification of the children, χ2(9, N = 257) = 6.64, p > .05.

We predicted a weak correlation between caregivers’ identification of their children’s race (operationalized as White, mixed White and Native, mixed White and Black, mixed Native and Black, or Black) and children’s self-chosen skin color from light to dark. There are two reasons to predict a weak correlation. The first is that although race and skin color can be related, they remain different constructs. The second reason is that both the respondents (caregivers vs. the children themselves) and methods through which the information was obtained were different. Caregivers responded to a closed-ended question regarding the children’s race whereas the children picked a color from an array of five color cards. Accordingly, although the constructs are not independent of one another, χ2(12, N = 257) = 32.20, p < .001, we found the relation between the two to be weak, ϕ coefficient = .31.

Substantive Results From Color of My Skin Measure

Regarding the color of their skin, the majority of the children (62.0%) chose light brown (2), 20.0% chose brown (3), 11.2% chose white (1), and 5.4% chose dark brown (4), with no child choosing black (5) (see Table 3). In response to the closed-ended questions, 96% of the children answered that it was not hard to pick a color and 96% liked having skin that color. When asked how they felt about their skin color, 95.3% said that they were either very happy or happy about it. Finally, the level of satisfaction with their skin color did not differ significantly by color, F(3, 256) = 1.43, p = .233.

Table 3.

Skin Colors Chosen by the Puerto Rican Childrena

| Card Number/Color | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 White | 29 | 11.2 |

| 2 Light Brown | 161 | 62.0 |

| 3 Brown | 53 | 20.0 |

| 4 Dark Brown | 14 | 5.4 |

| 5 Black | 0 | 0.0 |

N = 257.

The children’s choice of skin color was independent of their self-reported ethnic identity, χ2(8, N = 257) = 11.2, p > .05, and the racial or ethnic compositions of three social contexts: their neighborhood, χ2(9, N = 257) = 12.1, p > .05; their classmates, χ2(9, N = 257) = 10.6, p > .05; and their closest friends, χ2(9, N = 257) = 9.5, p > .05, where racial or ethnic composition was operationalized as mostly Puerto Rican, mostly Hispanic or Latino, mostly mixed from many different cultures, and mostly non-Hispanic or Latino. Moreover, children’s choice of skin color was also independent of the color of the interviewer, χ2(9, N = 257) = 14.3, p > .05.

When asked why they liked the color of their skin, 42% simply stated they liked the color. Examples of comments that were coded under this category are “porque es lindo” [because it is beautiful], “es un color bonito y es como suavecito” [because it is a pretty and soft color], and “es mi color favorito” [it’s my favorite color] (see Table 4). The next most frequently reported reason for liking one’s color (14.2%) was acceptance of being “born that way”; 8.1% of the children liked their color because it was similar to that of their families and friends; 4.9% stated that they liked their color because it was “in between,” for example, neither Black nor White. One comment coded under this category was, “Because I am a mixture. I’m made out of lots of colors.” Nine children (3.6%) stated that they liked their color “because it is a light color,” or “porque que es blanquito” [because it is white] and 6 children (2.4%) identified that it came from God, “porque Jesus me hizo asi” [because Jesus made me that way]. Four children (1.6%) specifically stated that they liked the color of their skin because it was a part of their Puerto Rican identity, “because I like my heritage, where I am from.” Two children (0.8%) said they liked their color because it was dark. Ten percent of the children did not know why they liked the color of their skin. Some of the other reasons given for liking the color of their skin included, “because people don’t make fun of my color. It is not dark,” and “because in the summer it changes darker and in the winter, lighter.”

Table 4.

Reasons Given for Liking the Color of Their Skin

| Reason | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Liked Their Color | 105 | 42.0 |

| Born That Way (Acceptance) | 35 | 14.2 |

| Liked to Be Like Family or Friends | 20 | 8.1 |

| Liked Being “In Between” (Color 3) | 12 | 4.9 |

| Liked Their Light Color | 9 | 3.6 |

| God Made Me This Way | 6 | 2.4 |

| Part of Puerto Rican Identity | 4 | 1.6 |

| Like Their Dark Color | 2 | 0.8 |

| Don’t Know | 24 | 9.7 |

| Other | 28 | 11.2 |

Note: Not all children answered this question (N = 248).

Seven children (3.0%) said they did not like their skin color. When they were asked, “Why do you not like having this skin color?” 5 children [all of whom had rated themselves as light brown (2)] responded that they wanted to be lighter. They said: “because I want to be White,” “porque yo quisiera ser mas blanca” [because I want to be whiter] and “porque la gente me llama ‘chocolate bar’” [because people call me chocolate bar]. Two children who understood themselves as white (1) wanted to be darker. They said, “porque me creo palida” [because I feel pale] and “porque yo quiero ser como Michael Jordan, ‘Black’” [because I want to be Black like Michael Jordan].

When specifically asked, “If you could have another skin color, would you want it?” 16% of the children (n = 41) responded affirmatively. There was no relation, however, between the self-reported colors of the children and their desire to change colors if possible, χ2(3, N = 257) = 3.81, p > .05. When asked what color they would like to change to, 51% wanted a lighter color, 46% a darker color, and 1 child eventually chose his original color. As delineated in Table 5, when asked an open-ended question on why they wanted a different skin color, 12 children (29.2%) gave the reason that they would like to be a lighter color, reporting, “porque me gusta bianco” [because I like white], “porque no me llamen nombres” [so they don’t call me names], and “I would like to change it to white skin because most people are White.” Nine children (21.9%) said that they would like to be a darker color, “porque con el que tengo parezco un fantasma” [because with the one I have I look like a ghost], and “because, with the color I have now, some people think I am White and they don’t believe that I am Puerto Rican.” Four children said that they wanted to be more like their family and friends; 4 children just liked the idea of a change, “para mirarme diferente” [to look different]; and 11 children gave other reasons such as “porque el sol no me queme” [so the sun won’t burn me].

Table 5.

Reasons Noted for Wanting to Have a Different Color of Their Skina

| Reason | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Would Like a Lighter Color | 12 | 29.2 |

| Would Like a Darker Color | 9 | 21.9 |

| Want to Be Like Their Family or Friends | 4 | 9.7 |

| Would Like a Change | 4 | 9.7 |

| Have Been Discriminated | 1 | 2.4 |

| Don’t Know | 11 | 26.8 |

N = 41.

When we grouped the children’s responses to the open-ended questions by sex and then by choice of skin color (1–4) to ascertain if there were any differences in the quality or types of responses, we did not find any differences across the sex or skin color groups.

The results of the children’s perceptions of their skin color were examined in association with their self-esteem. All the children reported very high levels of self-esteem (M = 4.50, SD = .43, on a 5-point Likert-type scale). As indicated in Table 6, there were no significant differences associated with skin color. These results were replicated with one third of the sample (n = 78) who had also taken Harter’s (1985) Self-Profile for Children. Once again, there were no significant differences in either the Global Self-Worth, F(3, 77) = 2.05, p = .11, or the Physical Appearance, F(3,77) = 2.69, p = .06, subscales of Harter that are associated with skin color.

Table 6.

Self-Esteem Scores By the Children’s Self-Report of the Color of Their Skina

| Card Number/Color | n | M | SD | F Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 White | 29 | 4.42 | .49 | F(3, 256) = .84; ns |

| 2 Light Brown | 161 | 4.55 | .37 | |

| 3 Brown | 53 | 4.57 | .50 | |

| 4 Dark Brown | 14 | 4.49 | .35 | |

| 5 Black | 0 |

Note Scale of 1 (very unhappy) to 5 (very happy).

N = 257.

On the other hand, children who would like to have a different skin color (n = 41; 46% wanted to be darker, 51% wanted to be lighter)3 had significantly, if only slightly, lower self-esteem (M= 4.38, SD = .46) than those who did not want to change the color of their skin even if they could (M = 4.55, SD = .45; t = 2.23, p = .02).

The interviewer’s external rating of the children’s skin colors was strongly correlated with the children’s perceptions, with 68% of the cases perfectly matched. Seven percent of the children were rated by the interviewers as one color category lighter and 25% were rated by the interviewers as one category darker than the children perceived themselves to be.

We did further analyses on self-esteem comparing children whose self-assessment of skin color agreed with the interviewer’s external assessment in contrast with those who viewed themselves as lighter or as darker than did the interviewer. The difference in self-perception and the interviewer’s external rating was related to the child’s sex, χ2(2, N = 257) = 6.47, p = .039. A greater proportion of the girls (31 %) than of the boys (19%) rated themselves lighter than did the interviewer. Moreover, children who perceived themselves as darker than did the interviewer had significantly lower self-esteem (n = 17, M = 4.28, SD = .45) than children whose perceptions matched the interviewer’s (n = 175, M = 4.57, SD = .44), F(2, 254) = 3.72, p = .025. The children who perceived themselves to be lighter did not have a significant difference in self-esteem (n = 65, M = 4.48, SD = .47) from the other two groups.

Additionally, the desire to change one’s skin color if one could and the self-assessment of one’s skin color as darker than the interviewer’s assessment are independent of one another. Thus we can conclude that, for the majority of the children, there was no association between skin color and self-esteem. However, wanting to change one’s color (lighter or darker), perceiving oneself as darker than did the interviewer, or both, which together, is true for 54 of the children (21 %), is a significant negative predictor of self-esteem (β = −.24, t =3.48, p < .001).

To examine if children see themselves as “darker” due to variation in their exposure to White society (either immersion within or isolation from), we examined the racial or ethnic composition of the social networks of the subgroup of children who saw themselves as “darker” than the interviewer saw them. Sixty-one percent of the “darker” children reported having classmates of mixed cultures and 49% reported living in neighborhoods of mixed cultures. Although not statistically significant, 41% of the children reported that their closest friends were Puerto Rican. We cannot conclude that the children saw themselves as darker because of greater direct exposure to Whites or isolation from Whites.

Discussion

The results of the psychometric analyses demonstrate that the Color of My Skin measure has acceptable test–retest reliability. The validity of the construct of a child’s internal understanding of his or her skin color, as measured by the instrument, is also acceptable. The validity of the construct was confirmed through the measure’s predicted moderately strong correlation with external ratings given by trained interviewers and through the predicted low correlation with caregiver’s designation of the child’s race. Moreover, children’s ratings of their color are not associated with sex, grade, ethnic identity, or the child’s or the parent’s nativity. Although the validation of the measure will continue, these results lend confidence in the adequacy of the psychometric qualities of the measure to carry out further analyses.

The results demonstrate that mainland Puerto Rican children are able to choose a color that they believe represents their skin color. Almost all children report being happy or very happy with their color. Given this very high satisfaction rate, it is not surprising that we did not find satisfaction with one’s color to be associated with any particular color. Regardless of what color they see themselves, they are happy with that color.

The majority of the reasons children offered for being happy with their color were not associated with the particular colors (1, 2, 3, or 4) they chose for themselves. The reasons they gave—“I like this color,” “it is a pretty color,” “because I was born with this color,” and “because that is the skin color of my Mom”—can be viewed as self-enhancement. In other words, these children attach a positive value to what is theirs, which is developmentally appropriate (see Harter, 1999).

In response to the hypothetical question of whether they would change their skin color if they could, only 16% of the respondents answered affirmatively. There was no relation, however, between the self-reported colors of the children and their desire to change colors if possible. Fifty-one percent of the children said that they would like to be a lighter color in contrast with 46% of the children who said that they would like to be a darker color. Taken together these findings do not lend support to the hypothesis that Puerto Rican children prefer light skin colors. Rather, the reasons given for being happy with one’s color and the lack of interest in changing skin color both suggest the widespread operation of positive self-evaluation typical of early to middle childhood. This tendency to see as good what one is or has is corroborated by the sample’s generally high self-esteem scores.

That these Puerto Rican children do not show a preference for light skin colors for themselves may seem like a contradiction of previous research. This research had shown a pro-White cultural bias in children’s preference for white dolls or pictures of light-skinned children. Spencer and Markstrom-Adams (1990) interpreted these previous findings as being a reflection of children’s awareness and acceptance of majority culture’s stereotypes about race. In their overview of the research on racial and ethnic minority children’s identity processes (Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990), they distinguished between stereotype acceptance, which they called a cultural-ecological variable, and self-esteem, which they viewed as a psychological variable. Our own research is primarily at the psychological level of the children’s preference for their own skin color. What we have shown is that the vast majority of these Puerto Rican children do not show a pro-White bias when that construct is measured as a psychological characteristic of a child’s perception of his or her own skin color. Therefore, our results are consistent with Spencer and Markstrom-Adams’s interpretation that awareness and even acceptance of mainstream racial stereotypes are not necessarily associated with low self-esteem.

The second hypothesis predicted that there would be no relation between skin color and self-esteem. This hypothesis was confirmed. For the majority of the children, we did not find that self-esteem was associated with self-chosen skin color. This finding corroborates the findings with African American (Powell, 1985; Spencer, 1984) and Native American (Beuf, 1977) children. Beuf (1977) stated that Native American children’s preference for white dolls is not a measure of their low self-esteem but their desire for the status and power of Whites. Spencer’s (1984) study of 130 Black preschool children (M age = 60.91 months) showed that 80% of the sample obtained positive self-concept scores, all the while endorsing pro-White cultural values on a racial attitude and preference measure. Based on her findings Spencer concluded that Black children can have a pro-White bias yet maintain high self-esteem. This conclusion was also supported by Powell’s (1985) research. Spencer and Markstrom-Adams (1990) argued that young African American children can have high self-esteem while being cognizant of larger society’s devaluing of dark-skinned people because of the cognitive egocentrism characteristic of young children.

We have also interpreted the lack of an association between skin color and self-esteem to be consistent with a developmental tendency for positive self-evaluations found in early to middle childhood (Harter, 1999). In her overview of the development of the construction of self, Harter (1999) suggested that, as Higgins (1991), Selman (1980), Gesell and Ilg (1946), and Fischer (1980) pointed out, in early to middle childhood, children are aware that others are critically evaluating them. However, they lack the type of self-awareness that is needed to be critical of their own behavior (Harter, 1999). This suggests that even if they are aware that larger society devalues dark skin their self-esteem will not suffer, which is consistent with what we found.

In contrast to research summarized by Spencer and Markstrom-Adams (1990), we found that only a few children articulated negative associations with dark skin color. It appears that among Puerto Ricans there is no widespread awareness or internalization of mainstream society’s devaluation of non-Whites in early to middle childhood. The lack of negative association with dark skin color in this age group contrasts with the results of a study of 13- to 14-year-old Puerto Ricans that showed 50% of these early adolescents were aware of mainstream culture’s negative stereotypes of Puerto Ricans (Biggs, Erkut, Alarcón, & Szalacha, 1997). However, in this group of Puerto Rican adolescents, just as Powell (1985) and Spencer (1984) found for African American children and Beuf (1977) found for Native American children, awareness of negative stereotypes was not associated with lower self-esteem.

We can only speculate as to why Puerto Rican children in early to middle childhood do not show a widespread awareness of negative stereotypes about skin color. One possibility is that the level of overt racism has declined from the 1970s and 1980s (when the studies referring to African American and Native American children’s pro-White bias awareness were conducted) to the mid-1990s, when these data were collected. If this interpretation is correct, we can surmise that the pro-White bias does not enter most Puerto Rican youth’s conscious awareness until adolescence. Another explanation can be that, at this prepubescent age, Puerto Rican children are less concerned with appearance in terms of acceptance in peer groups or attraction to the opposite sex.

An alternative explanation for Puerto Rican children’s lack of awareness of negative associations with dark skin colors can be that they identify their skin color with their ethnicity, as Puerto Ricans, Hispanics, or Latinos, rather than with being non-White. However, we found that only 4 children mentioned the ethnic identity association with skin color. The low incidence of connecting ethnicity with color in this early-to-middle childhood sample contrasts with adults’ responses to questions on race. When the caregivers in the sample were asked about their child’s race, 25.5% chose the “other” option and stated the child’s ethnicity instead. Rodriguez and Cordero-Guzman (1992) reported that Puerto Rican adults’ tendency to prefer the “other” designation when asked about race has different roots, all of which indicated abstract reasoning. For some, it was a cultural response that carried a racial implication, indicating that they see race and culture as fused. For others it represented being a “mixed” people. For still others it meant that they viewed race and culture as independent concepts. None of the reasons Rodriguez and Cordero-Guzman (1992) found for asserting ethnicity are likely to be developmentally available to the prepubescent children in this sample.

We found two notable exceptions to the generally high levels of self-esteem in this sample.4 One was among children who said they would change their skin color if they could (n = 41, 16%). These children had significantly, albeit only slightly, lower self-esteem scores than children who did not want to change their color. It is not surprising that a desire for change is associated with a somewhat lower satisfaction with the self; conversely, those who are very pleased with themselves, which is the majority of the children, showed no desire to change their color.

The other exception was the children who rated themselves as darker than the interviewers (n = 17, 7%). This small group of children also had significantly, if only slightly, lower self-esteem than children whose self-designated skin color was lighter than the interviewers’ assessment or agreed with it. Rodriguez (1995) speculated that mainland Puerto Rican adults might think they have a darker skin color than they actually do because they have internalized the label “non-White.” Alternatively, perceiving one’s self as darker may be a by-product of isolation from Whites. Not having White best friends or neighbors may have accentuated the internalization of being dark or of being non-White.

We examined the validity of these alternative explanations by testing if greater exposure to racial or ethnic groups (Whites, Puerto Ricans, Hispanics or Latinos, African Americans, Asian Americans, mixed cultures) in the social context of these children’s lives may have created either a contrast effect, whereby they saw themselves as darker than the people in their social networks, or an isolation effect, which accentuated the internalization of “darkness.” Our results showed that rating oneself as darker than the interviewer was independent of the racial or ethnic composition of the children’s classmates, their neighborhoods, and their closest friends. The phenomenon of “internalizing a darker color” due to exposure to Whites may have developmental underpinnings such that it is more characteristic of older children and adults.

Finally, another alternative explanation as to why children rated themselves as being darker than did the interviewer, is the possibility that in their own families these children were designated as the dark one. Although one boy asserted in response to the open-ended questions that, “I am the negrito in my family. I get blamed for everything,” we do not have data on all of the children’s colors in comparison with each child’s family to test this hypothesis. Although intrafamily color variations are widely recognized and openly discussed (Rodriguez, 1995), the question of whether being labeled the dark one in the family is related to self-esteem has not been researched.

We have no direct information on the question of why children who view themselves as darker also report lower self-esteem scores. Having disconfirmed several alternative explanations, we question whether the children who are less pleased with themselves see themselves as darker because they have internalized color prejudices dominant in larger society. It may be that relatively low self-esteem is racialized, such that children who feel less well about themselves associate this with their skin color. That is, although perceiving oneself as darker may not cause lower self-esteem, having lower self-esteem may well cause children to locate that tension in a racial manner. This is a question future research should examine with multiple external assessments of a child’s skin color. We only had one external assessment provided by the interviewers. Future research should also employ a larger sample, keeping in mind that we observed this tendency only in 17 children, which constituted 7% of this sample.

A final noteworthy finding also comes from the comparison of the children and interviewers’ assessment of skin color. We found that girls were overrepresented in the group that rated themselves to have lighter skin color when compared with the interviewers’ assessments. Perhaps this is a reflection of mainland Puerto Rican girls’ tendency to be influenced by White beauty standards. In a study of Puerto Rican early adolescents, we found both psychological and behavioral acculturation to be associated with lower confidence in physical appearance in girls but not in boys (Erkut, Szalacha, García Coll, & Alarcón, in press). It may be that Puerto Rican girls have a greater desire to measure up to White beauty standards of fair skin than boys.

We have been interested in studying skin color as an aspect of mainland Puerto Rican children’s normative development because these children are potentially exposed to two different color or race classification systems through their Puerto Rican heritage and by virtue of living on the mainland. Our results show that, with the exception of a few children who reported negative associations to having a dark skin color, the majority of Puerto Rican children do not exhibit indications of experiencing conflict due to their skin color or due to being exposed to two different systems of color or race classification. Stated in another way, at this point in their lives, the two different systems of color and race do not appear to be generating conflict that can be detected by open- and closed-ended questions posed by a same-ethnicity interviewer in the language of the child’s choice.

Overall, this research suggests that the Color of My Skin instrument is a valid and reliable measure of children’s internal concept of their skin color. During early to middle childhood, Puerto Rican children do not show a preference for having a lighter skin color and their self-esteem is not related to their perception of the color of their skin. Indeed, almost all children reported being either happy or very happy with their skin color, and as a group, the sample had high self-esteem. We view these findings as consistent with the cognitive developmental tendency to place a high value on one’s self during early to middle childhood. A relatively small percentage of children (16%) who expressed a wish to change their color if they could had slightly lower self-esteem than children who did not want to change their color, and a small number of children (7%) who viewed themselves to be darker than the color assessment by the interviewer also reported slightly lower self-esteem scores.

In summary, with the exception of a few children’s responses, the children did not express an awareness of two differing systems of color or race classification in the closed-ended or open-ended responses. Regarding the detrimental effect of being exposed to mainstream society’s devaluation of non-Whites in this early-to-middle childhood sample, our research suggests that although being a minority may not cause a child psychological injury, being psychologically injured (as evidenced by low self-esteem) may lead one to focus precisely on the social injury inflicted by racism. The generalizability of these findings needs to be established with a direct examination of affect surrounding skin color among children from other non-White racial and ethnic groups and also Puerto Rican children living in other parts of the mainland.

Appendix

The Color Of My Skin

Before you begin this exercise, make sure that your set of colored cards is numbered from 1 to 5, and that the child’s set of colored cards has all the five colors.

Here are two sets of cards, one for me and one for you. Look at your set, mix it around. We’re going to play some games with them. (Give child his or her packet of colored cards numbers side down.)

First let’s play a matching game. I’ll put down one of my cards, then you find your card that is the same color and put it next to mine. (Place your colored cards one at a time in any order with the numbers facing down. Wait until child has put down the matching one Do this a few times, to make sure child understands matching. Stop as soon as child seems bored and put child’s set of cards away.)

*If child sees the numbers on your set of cards, say that we use them to identify the color on the cards.

Now, I would like you to pick a color that you think is most like the color of your skin. It’s ok to take your time, there are many different colors here and I just want you to pick the card that is most like the color of your skin. (Encourage the child to take his or her time. Do not permit the child to match the card with his or her hand. When the child has chosen a colored card move on to next question.)

Record the number of the colored card which you think best represents this child’s skin color. Please do this before child chooses his own color.

| 1. Let’s see what you picked. | Write the number that appears on the back of the colored card. |

| 2. Is this the color you think is most like the color of your skin? | [1] Yes (go to No. 5); [2] No (continue) |

If No, pick another color that you think is most like the color of your skin. Take your time. Remember, you want to pick the color that you think is most like the color of your skin.

| 3 Let’s see what you picked. | Write the number that appears on the back of the colored card. |

| 4. Is this the color you think is most like the color of your skin? | [1] Yes [2] No |

| 5. Was it hard for you to choose a color that is most like the color of your skin? | [1] Yes (if yes): Why? (record verbatim) [2] No |

| 6. Do you like having this skin color? | [1] Yes (go to No. 7a) [2] No (go to No. 7b) |

| 7a. Why do you like having this skin color? | (record verbatim; go to No. 8) |

| 7b. Why do you not like having this skin color? | (record verbatim) |

| 8. Which face on this card shows how you feel about the color of your skin? | (show faces card) [1] Very Sad [2] A Little Sad [3] Neither Sad Nor Happy [4] A Little Happy [5] Very Happy |

| 9. If you could have another skin color, would you want it? | [1] Yes (go to No. 10a) [2] No (go to No. 10b) |

| 10a. Tell me why you would want another skin color? | (record verbatim; go to No. 11) |

| 10b Tell me why you would not want another skin color? | (record verbatim) |

| 11. (Ask only if child wants to change skin color) What color skin would you want? Pick the card that is the color you would like your skin to be. | Write the number that appears on the back of the colored card. |

OK, let me collect the colored cards.

Footnotes

Lakeshore Learning Materials, 2695 East Dominguez Street, P.O. Box 6261, Carson, CA 90749.

Only one child lived with a single father.

One child indicated a desire to change skin color but then chose to be the same color.

It is important to reiterate that the self-esteem levels, as a whole, were quite high. The mean self-esteem for those children who wanted to change their color was still a 4.3 on a 5-point scale.

Contributor Information

Odette Alarcόn, Wellesley College.

Laura A. Szalacha, Wellesley College

Sumru Erkut, Wellesley College.

Jacqueline P. Fields, Wellesley College

Cynthia García Coll, Brown University.

References

- Aboud FE. Egocentrism, conformity, and agreeing to disagree. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17:791–799. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE. Children and prejudice. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE, Christian JD. Development of ethnic identity. In: Eckensberger L, Poortinga Y, Lonner WJ, editors. Cross-cultural contributions to psychology. Lisse, Holland: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE, Mitchell FG. Ethnic role taking: The effects of preference and self-identification. International Journal of Psychology. 1977;12:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón O. Measuring ethnic identity of Puerto Rican children raised in the mainland; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Albuquerque, NM. 1999. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón O, Erkut S, García Coll C, Vázquez García HA. Engaging in culturally-sensitive research on Puerto Rican youth. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley College Center for Research on Women; 1994. (Working Paper No. 275) [Google Scholar]

- Beuf SH. Red children in White America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs A, Erkut S, Alarcón O, Szalacha L. Puerto Rican adolescents ' stereotype awareness, ethnic pride, and feelings of self worth; Poster session presented at the meeting of the Society for Child Development; Washington, DC. 1997. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Boswick B. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Hayward: California State University; 1973. Skin color perceptions of Black, Mexican-American and White children. [Google Scholar]

- Clark KB, Clark M. The development of consciousness of self and the emergence of racial identification in Negro preschool children. Journal of Social Psychology SPSSI Bulletin. 1947;10:591–599. [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Hocevar D, Dembo MH. The role of cognitive development in children’s explanations and preferences for skin color. Developmental Psychology. 1980;16:332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L. Puerto Rican women’s cross-cultural transitions: Developmental and clinical implications. In: García Coll C, de Lourdes Mattei M, editors. The psychosocial development of Puerto Rican women. New York: Praeger; 1989. pp. 166–199. [Google Scholar]

- Cota-Robles de Suárez C. Skin color as a factor of racial identification and preference of young Chicano children. Aztlan. 1971;2:107–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE., Jr . Shades of Black diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Davis F. Who is Black: One nation’s definition. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Erkut S, Alarcón O, García Coll C, Tropp L, Vázquez H. The dual-focus approach to creating bilingual measures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1999;30(2):206–218. doi: 10.1177/0022022199030002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkut S, García Coll C, Alarcón O. Doing research in an under-studied population: Methods of obtaining and retaining samples; Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Albuquerque, NM. 1999. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Erkut S, Szalacha L, García Coll C, Alarcón O. Puerto Rican early adolescent self-esteem patterns. Journal of Research on Adolescence. doi: 10.1207/SJRA1003_6. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer KW. A theory of cognitive development: The control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychological Review. 1980;87:477–531. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick JP. Puerto Rican Americans: The meaning of migration to the mainland. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee F, Tucker GR, Lambert WE. The development of ethnic identity and ethnic role-taking skills in children from different school settings. International Journal of Psychology. 1978;13:39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gesell A, Ilg F. The child from five to ten. New York: Harper & Row; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Gimelli JC. Influence of skin color and sex role identity of self-concept of Puerto Rican adolescents. Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilm International; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M. Race awareness in young children. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual: Self-Perception Profile for Children. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Pike R. The pictoral scale of perceived competence and racial acceptance for young children. Child Development. 1984;55:1962–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AR. The issue of skin color in psychotherapy with African Americans. Families in Society Journal. 1995;76(1):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Helms BJ, Gable RK. School situation survey. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Development of self-regulatory and self-evaluative processes: Costs, benefits, and tradeoffs. In: Gunnar MR, Sroufe LA, editors. Self processes and development: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Development. Vol. 23. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1991. pp. 125–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld L. Race in the making: Cognition, culture, and the child’s construction of human kinds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes RM. How young children perceive race. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz RE. Racial aspects of self-identification in nursery school children. Journal of Psychology. 1939;7:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DJ. Racial preference and biculturality in biracial preschoolers. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1992;38:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Katz PA, Zalk SR. Modification of children’s racial attitudes. Developmental Psychology. 1978;14:447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Neto F, Paiva L. Color and racial attitudes in White, Black and biracial children. Social Behavior & Personality. 1998;26:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur EJ, Schmelkin LP. Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of the research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter PC. Social reasons for skin tone preferences of Black school-age children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61:149–154. doi: 10.1037/h0079219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell GJ. Self-concept among Afro-American students in racially isolated minority schools: Some regional differences. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:142–149. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60439-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, Anderson G, Bartell N. Measuring depression in children: A multimethod assessment investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1985;13:513–526. doi: 10.1007/BF00923138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TL, Ward JV. African American adolescents and skin color. Journal of Black Psychology. 1995;21:256–274. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CE. Puerto Ricans: Between Black and White. In: Santiago R, editor. Boricuas: Influential Puerto Rican writings—An anthology. New York: Ballantine; 1995. pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CE, Cordero-Guzman H. Placing race in context. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1992;15:522–541. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M, Taylor M. Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds? In: Semin G, Fiedler K, editors. Language, interaction and social cognition. London: Sage; 1992. pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Selman RL. The growth of interpersonal understanding. New York: Academic; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Black children’s race awareness, racial attitudes and self-concept: A reinterpretation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1984;25:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1984.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Horowitz FD. Racial attitudes and color concept-attitude modification in Black and Caucasian preschool children. Developmental Psychology. 1973;9:246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Markstrom-Adams C. Identity process among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child Development. 1990;61:290–310. [Google Scholar]

- Straus A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park: CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA. Measuring self-esteem with Puerto Rican children on the mainland; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; Chicago. 1997. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA. The development of a self-esteem measure for Puerto Rican children; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Albuquerque, NM. 1999. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Current Population Reports. Washington DC: Author; The Hispanic population in the United States. 1993 March; (Series No. 20–475)

- Vaughn GM. Concept formation and the development of ethnic awareness. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1963;103:93–103. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1963.10532500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verna GB. Use of a free-response task to measure children’s race preferences. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1981;138:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JE, Best DL, Boswell DA. The measurement of children’s racial attitudes in the early school years. Child Development. 1975;46:494–500. [Google Scholar]