Abstract

Viral encephalitis is a significant cause of human morbidity and mortality in large part due to suboptimal diagnosis and treatment. Murine reovirus infection serves as a classic experimental model of viral encephalitis. Infection of neonatal mice with T3 reoviruses results in lethal encephalitis associated with neuronal infection, apoptosis, and CNS tissue injury. We have developed an ex vivo brain slice culture (BSC) system that recapitulates the basic pathological features and kinetics of viral replication seen in vivo. We utilize the BSC model to identify an innate, brain-tissue specific inflammatory cytokine response to reoviral infection, which is characterized by the release of IL6, CXCL10, RANTES, and murine IL8 analog (KC). Additionally, we demonstrate the potential utility of this system as a pharmaceutical screening platform by inhibiting reovirus-induced apoptosis and CNS tissue injury with the pan-caspase inhibitor, Q-VD-OPh. Cultured brain slices not only serve to model events occurring during viral encephalitis, but can also be utilized to investigate aspects of pathogenesis and therapy that are not experimentally accessible in vivo.

Keywords: reovirus, virus, viral, apoptosis, caspase, encephalitis, neuron, ex vivo, organotypic, brain slice, cytokine, MCP-1, IL6, KC, IL8, CXCL10, RANTES, Q-VD-OPh

INTRODUCTION

Viral encephalitis is a major cause of hospitalization, disability, and death throughout the world (Tan et al., 2008). The morbidity and mortality of viral encephalitis is due to the lack of effective therapies. For example, there is no therapy of proven benefit for encephalitis caused by Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV; the most common cause of viral encephalitis worldwide) or West Nile virus (WNV; the most common cause of epidemic encephalitis in the United States) (Solomon, 2004). Even when specific antiviral therapy is available, as exemplified by acyclovir treatment of herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis, mortality and morbidity remain substantial (Raschilas et al., 2002; Tyler, 2004). Thorough understanding of the cellular and molecular events occurring within the encephalitic brain will provide a rational basis for identifying novel targets for antiviral and neuroprotective therapy.

Reovirus infection is an established in vivo model for the study of viral-induced neuropathogenesis (Clarke et al., 2005; Oberhaus et al., 1997; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002; Richardson-Burns and Tyler, 2004; Richardson-Burns and Tyler, 2005). Intracranial inoculation of neonatal mice with neurotropic T3 reoviruses results in rapidly progressive encephalitis and death (Schiff et al., 2007). Reovirus encephalitis is characterized by brain injury and Caspase 3-dependant neuronal apoptosis (Beckham et al., 2007; Beckham et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 2005; Goody et al., 2007; Oberhaus et al., 1997; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002; Richardson-Burns et al., 2004). Apoptotic neuronal death is also a central pathological feature of encephalitis caused by a diverse group of important neurotropic viruses including cytomegalovirus, HSV, WNV, and Sindbis virus (Debiasi et al., 2002; Griffin, 2005; Michaelis et al., 2007; Perkins et al., 2003; Samuel et al., 2007). In vitro studies of WNV, JEV, and reovirus have identified Caspase 3-dependant apoptosis as a major mechanism underlying viral neuropathogenesis (Clarke et al., 2009; Kleinschmidt et al., 2007; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002; Tsao et al., 2008). Defining the molecular events that contribute to viral encephalitis has proven challenging in vivo. In vitro models of viral infection (e.g. primary neuronal cultures) offer advantages in terms of experimental flexibility, however these systems fail to replicate the complex multicellular milieu of brain tissue.

Culturing brain tissue is a uniquely powerful methodology for the study of neurological diseases. Explanted brain slices maintain relevant tissue form (i.e. cellular composition and tissue architecture) and function (i.e. local synaptic connectivity), yet may be subjected to a broad range of experimental conditions otherwise impossible in the intact animal (Cho et al., 2007; Gahwiler et al., 1997). Brain slice models of stroke/ischemia (Cho et al., 2004; Finley et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2004), epilepsy (Akimitsu et al., 2000; Khosravani et al., 2003; Losi et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010), Alzheimer’s disease (Harris-White et al., 2004; Lambert et al., 1998), and Parkinson’s disease (Bywood and Johnson, 2003; Gille et al., 2004; Sherer et al., 2003; Shimizu et al., 2003) have been established previously. Cultured brain tissue has also been utilized to study viral tropism (Braun et al., 2006; Mayer et al., 2005; Tsutsui et al., 2002) and virus-mediated gene transfer (Ehrengruber et al., 1999). However, ex vivo modeling of pathologic (Chen et al., 2004; Mayer et al., 2005) and immunologic (Friedl et al., 2004) events related to CNS viral infection is underdeveloped; and, brain slices have not yet been utilized for screening therapeutic agents for potential efficacy against viral encephalitis.

We now describe a method of ex vivo coronal brain slice culture (BSC) preparation and viral infection, which replicates pathogenesis known to occur during encephalitis. Through assessment of viral titer, tissue injury, and apoptosis, we show that the basic virologic and pathologic features of in vivo reovirus infection are readily recapitulated in the BSC model. Analysis of CNS-specific innate immune responses to viral infection in vivo is complicated by the presence of both peripheral immune reactions and brain-infiltrating inflammatory cells. We use BSCs to identify specific cytokine responses to viral infection that occur in the complete absence of the systemic immune system and depend only on resident CNS cells. The screening of potential neuroprotective compounds in vivo is confounded by problems related to bioavailability, systemic metabolism, and the presence of the blood-brain barrier. Although these factors are ultimately critical for drug design and delivery, it would be useful to have a platform to screen for the neuroprotective capacity of compounds independent of these considerations. We now demonstrate, using pan-caspase inhibitor (Q-VD-OPh), that BSCs can be used for this purpose.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of organotypic brain slice cultures (BSCs)

Brain slice cultures were prepared from 2–3 day old NIH Swiss Webster mice in compliance with institutional guidelines. Mice were euthanized by decapitation and brains rapidly removed into ice-cold slicing media (MEM, 10mM Tris, 28mM D-glucose, pH 7.2, equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2). Under semi-sterile conditions, the frontal cortex and cerebellum were removed and 400µm coronal sections cut through cerebral regions containing hippocampus and thalamus using a Vibratome (Classic 1000; Bannockburn, IL). Four slices from a single animal were carefully positioned onto a single semi-porous membrane insert (Millipore #PICMORG50, Billerica, MA) according to the method of Stoppini et al. (Stoppini et al., 1991). Membranes were placed in 35mm tissue culture dishes containing 1.2ml serum-containing media (Neurobasal supplemented with 10mM HEPES, 1x B-27, 10% FBS, 400µM L-glutamine, 600µM Glutamax, 60U/mL Penicillin, 60µg/mL Streptomycin, 6U/mL Nystatin), such that slices were at the media-air interface. Media was refreshed with 5% serum-containing media (5% FBS) approximately 12h after slicing. All subsequent media changes were made with serum-free media every two days (i.e. 3dpi, 5dpi, 7dpi, and 9dpi). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 and 36.5°C.

Viral stocks and BSC infection

Reovirus serotype 3 strain Abney (T3A) reovirus used for all experiments is an ultrapure laboratory stock derived via plaque purification, double passage in L929 cells, and cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation. Immediately after plating, slices were infected with 106 pfu T3A/slice. Virus was diluted into 20µl PBS and applied dropwise to the top (air interface) of each slice. Mock infections were performed in a similar manner with PBS alone.

Cryosectioning of BSCs

At 5dpi, slices were washed three times with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Fixed slices were then carefully separated from culture membranes and cryoprotected by overnight submersion in 15% sucrose/PBS, followed by overnight submersion in 30% sucrose/PBS. Slices were embedded in Tissue Freezing Media (Triangle Biomedical Sciences; Durham, NC) and resliced at 20µm with a cryostat (Cryotome E; Thermo Shandon; Waltham, MA). Resultant sections were affixed to Colorfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher; Pittsburgh, PA) and stored at room temperature until processing for immunohistochemistry.

Fluorescence immunohistochemistry

To visualize infected cells within the resliced tissue, sections were desiccated at 50°C for 15 min then rehydrated in PBS over 30 min. Tissue was subjected to antigen retrieval (antigen unmasking solution; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) and permeabilization/blocking (5% fetal bovine serum and 5% normal goat serum in 0.3% Triton/PBS) prior to incubation with primary antibodies: monoclonal reovirus σ3 antibody (4F2; 1:100), mouse anti-neuronal nuclear antibody (NeuN; 1:100; Millipore; Billerica, MA), and/or mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:300; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). Sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) and/or Cy3-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:300; Jackson ImmunoResearch; West Grove, PA). Nuclei were Hoechst stained (10 µg/ml; Immunochemistry Technology; Bloomington, MN) prior to mounting sections with VectorShield Hard Mount (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA). Slides were imaged on a MarianasTM imaging workstation (Intelligent Imaging Innovation Inc, Denver, CO) based on a Zeiss 300M inverted microscope and CoolSnap HQ2 CCD camera, all controlled by Slidebook 4.2 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovation). Images are presented as obtained in Slidebook without changing “gamma” settings and without cropping.

RT-qPCR analysis

Experimentally similar slices were washed three times in PBS and triturated in RLT buffer (Qiagen; Germantown, MD) containing 1% β-mercaptoethanol. Lysate was processed through a QIAshredder (Qiagen; Germantown, MD) and loaded onto an RNeasy spin column (Qiagen; Germantown, MD) for mRNA purification according to manufacture protocol. RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) were assessed on an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA) to confirm mRNA quality.

Two primers designated RV-1 (CCATTTATGGGGGTTCCTGC) and RV-2 (CTTTAAGTATTCGGCAGTCCC) were synthesized (Invitrogen; San Diego, CA) to amplify a 497-bp segment of the reovirus L1 gene (Tyler et al., 1998). Quantification of viral burden relative to a housekeeping gene was achieved by concurrent amplification of mouse β-actin (primer #PPM02945A SABiosciences, Frederick, MD). Purified RNA template, primers, RT-PCR master mix, and reverse transcriptase (iScript One-Step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR Green) were mixed into a total volume of 20µL. Fourty cycles of PCR amplification were performed on an Opticon 2 C1000 Thermocycler (Bio-rad; Hercules, CA) as follows: cDNA synthesis at 50°C for 10 min, reverse transcriptase inactivation at 95°C for 5 min, denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec. Melt curve analysis confirmed absence of non-specific products and primer-dimers. C(t) values were converted to relative expression values on Biorad CFX Manager analysis software.

Viral titer plaque assays

Viral titers were determined by plaque assays as previously described (Debiasi et al., 1999). Briefly, L929 mouse fibroblasts, used for viral titer assays, were maintained in DMEM medium (supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 4mM L-glutamine). All four slices from a single well were washed three times with PBS and placed into 1mL PBS, before being subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles and brief sonication with an ultrasonic processor set at 35% amplitude (Cole -Parmer; Vernon Hills, IL). Serial dilutions of the BSC homogenate were prepared in gel saline to a total inoculum volume of 200uL. Viral adsorption proceeded for 1h before L929s were overlayed with 1.5% Agar/2X199 media. Cells were overlayed again at 4dpi. On 7dpi, both layers of agar/media were gently removed and remaining cells fixed and stained with 0.3% methylene blue in 5% formalin. Plaques were counted and the reported pfu/mL value was calculated by correcting for inoculum volume and dilution factors.

Propidium iodide (PI) assay

PI is excluded by the intact plasma membranes of live cells; whereas, the molecule permeates dead/dying cells to intercalate with DNA and become fluorescent (Cho et al., 2004). PI uptake has previously been established as a reliable means of detecting cellular death in brain slice cultures (Noraberg et al., 1999). On 7dpi, fresh media containing 3µM propidium iodide (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) was added to each well before plates were returned to a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 and 36.5°C. After incubating for 1h, experimentally similar slices were washed three times with PBS and Dounce homogenized in 500µL of PBS. Individual 150µL samples were pipetted in triplicate into a 96-well plate. To precipitate cells, the plate was centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 5 min. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 24h. The desiccated samples were read on a Cytofluor Series 4000 spectrofluorometer (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, California) at excitation wavelength of 530nm and emission wavelength of 645nm.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay

LDH efflux is commonly used as a measurement of injury in organotypic slices (Bruce et al., 1995; Noraberg et al., 1999). BSC media was collected at various times post-infection and triplicate 10µl samples were analyzed with the LDH-Cytotoxicity Assay Kit II (Biovision; Mountain View, CA) in which water was used as a blanking control and purified LDH used as a positive control. LDH activity was quantified on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices Emax; Sunnyvale, CA) as a function of the optical density (OD) measured at 450nm with wavelength correction at 650nm.

MTT assay

MTT, a yellow tetrasolium salt, is cleaved to purple formazan crystals by metabolically active cells. We have utilized this assay to confirm the viability BSCs at various times post-plating and to qualitatively identify anatomical areas of tissue injury induced by reovirus infection. For the latter studies, BSC media was replaced with fresh media containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT (Roche Applied Science; Boulder, CO) at 11dpi. BSCs absorbed MTT from the media and produced formazan for a span of 45 mins before BSCs were photographed. Dark purple tissue was identified as alive, whereas pale/white tissue was identified as dead.

Fluorogenic Caspase 3 activity assay

Caspase 3 activity was determined by utilizing a fluorogenic assay (B&D Biosciences; San Jose, CA). Activated Caspase 3 hydrolyzes the synthetic peptide substrate Ac-DEVD-AFC resulting in the generation of a fluorescent reporter molecule 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin (AFC). The reaction product was measured on a Cytofluor Series 4000 spectrofluorometer (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, California) at excitation wavelength of 450nm and emission wavelength of 530nm.

Western blot analysis

Slices from a single well were rinsed three times with PBS and triturated in lysis buffer (1% Triton-X, 10mM triethanolamine-HCl, 150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 1mM PMSF, 1X Halt protease & phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific; Rockford, IL). Lysates were cleared, electrophoresed through 10% polyacrylamide gels at a constant 65V, and transferred to Hybond-C nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences; Pittsburgh, PA). Immunoblotting was performed with rabbit, anti-mouse antibodies directed against cleaved Caspase 3 (cC3), cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (cPARP) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and monoclonal IgM actin (Calbiochem; Sunnyvale, CA). Following washes and 1h incubation with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch; West Grove, PA), images were obtained on a FluorochemQ MultiImage III imaging workstation (Cell Biosciences; Santa Clara, CA) and images processed with manufacture software (Alphaview v3.0).

Cytokine ELISA

BSC media was screened for cytokine release with Multi-Analyte ELISArray Kits (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, for individual BSC preps (N≥3) media from experimentally similar wells was pooled and pipetted into ELISArray plates for a 2h binding incubation. The plates were washed three times prior to 1h incubation with detection antibody. Following another series of three washes, bound secondary antibody was detected by streptavidin-HRP and quantified on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices Emax; Sunnyvale, CA). Absorbance was read at 450nm (with wavelength correction at 560nm). Individual cytokines identified as being released in response to reovirus infection were further characterized on single analyte ELISA plates (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) following a similar protocol. Quantification of cytokine concentration was performed by placing absorbance values upon a standard curve specific to each cytokine.

Q-VD-OPh treatment

The pan-caspase inhibitor, Q-VD-OPh, and the negative control peptide were purchased from Biovision (Mountain View, CA). Approximately 12h after being infected, negative control peptide or Q-VD-OPh was applied to the top (air-interface) of slices at a concentration of 500 µg/mL (in 10% DMSO) to yield a final concentration of 36.4 µg/mL upon entering the media. Additional treatments were made every two days thereafter (coinciding with media changes). At 7dpi or 11dpi, media and slices were collected for analysis of Caspase 3 cleavage by Western blot, tissue injury by LDH and MTT assays, and relative viral titer by RT-PCR.

Statistical analysis

Data are graphically presented as mean ± SD. Numbers of independent experiments are indicated by the N value. All statistical analyses were performed using Instat and Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical comparisons between two groups (i.e. mock vs. infected or negative control peptide vs. Q-VD-OPh) were made using a two-tailed, unpaired t test with Welch correction. Probability values of p<0.05 were considered significant differences and denoted as such with asterisks.

RESULTS

BSCs support viral replication

To determine whether reovirus infects ex vivo cultured mouse brain tissue, BSCs were prepared from 2–3 day old neonatal mice (Fig. 1A) and immediately inoculated with 106 pfu/slice of T3A. At 5dpi, slices were cryosectioned and immunochemistry was performed with a monoclonal antibody specific for the reovirus major outer capsid protein σ3 (Fig. 1B). Reovirus staining was only apparent in cells with neuronal morphology. To confirm neuronal specificity of infection, σ3 stained slices were co-labeled with the neuron-specific marker, NeuN, or the astrocyte-specific marker, GFAP (Fig. 1C). The cytoplasmic pattern of antigen staining only within reovirus-infected neurons is identical to that seen during viral encephalitis in vivo and in primary neuronal cultures in vitro (Richardson-Burns et al., 2002). To determine the kinetics of reovirus replication in BSCs, viral load was quantified over a time course by RT-PCR detection of reovirus RNA using primers specific for the viral L1 gene (Fig. 1D) and traditional plaque assay (Fig. 1E). Both assays revealed exponential viral growth during the first 5dpi. Viral replication peaked at 7–9dpi with both RNA expression (Fig. 1D) and the amount of infectious virus (Fig. 1E) having increased ~1 million-fold from the time of inoculation (t=0). The kinetics of replication and the end-point viral titer (~109 pfu/ml) closely resembled values detected during in vivo reovirus encephalitis.

Figure 1. BSCs support viral replication.

(A) Anatomical organization of a freshly cut brain slice containing thalamic, hippocampal, and cortical tissue. Red inset delineates the frontoparietal cortical area pictured in Figure 1B. (B) At 5dpi, BSCs were removed from media and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before being cryosectioned. Resliced sections were stained with anti-reovirus monoclonal σ3 primary antibodies and anti-mouse Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies. High levels of reovirus antigen were found within cells of the cortex, localized to discrete foci. 100X magnification. (C) 5dpi BSCs were fixed and cryosectioned prior to incubation with primary antibodies: monoclonal reovirus σ3 antibody and mouse anti-neuronal nucleus antibody (NeuN) or anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and/or Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Reovirus antigen is located specifically within the cytoplasm of neurons, as represented by white arrows. 630X magnification. (D) RNA was purified from BSCs at stated times post-infection (N≥2). Quantification of L1 gene of reovirus relative to β-actin transcript revealed exponential viral growth in the first week in culture, yielding significant differences (p≤0.014) between early (dpi≤1) and late (dpi≥3) timepoints. t=0 was defined as a reference value equal to 1. (E) BSCs (N≥3) were harvested at given time points and processed for absolute viral titer determination by plaque assay on L929 mouse fibroblasts. Titers of all later time points were significantly higher (p≤0.0071) than the titer at the time of inoculation (t=0).

Viral infection induces tissue injury in BSCs

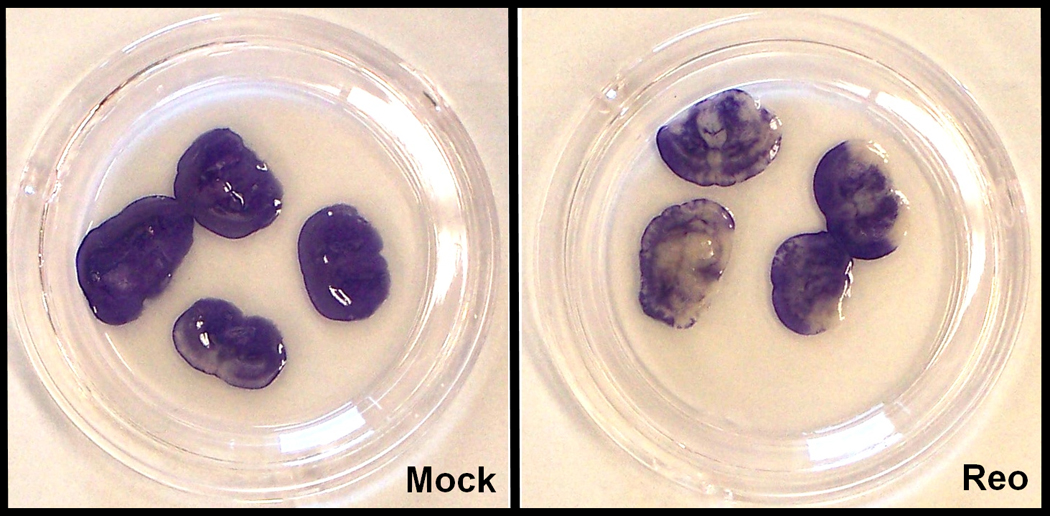

Having shown that virus replicates in BSCs, we next wished to determine whether viral infection was associated with tissue injury by quantitatively analyzing cellular membrane breakdown via propidium iodide (PI) staining and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. PI is a fluorescent molecule that is excluded by viable cells, but penetrates cellular membranes and intercalates into the DNA of damaged cells (Cho et al., 2004). Given that viral titers peak approximately one week after infection and injury correlates with high titers in vivo, 7dpi BSCs were selected for initial PI studies. Slices were placed in fresh media containing 3µM PI for 1h before being homogenized for quantification of cell death on a spectrofluorometer. PI fluorescence was 2.6-fold greater (p=0.004) in infected 7dpi BSCs compared to mock-infected controls (Fig. 2A). Since BSCs must be sacrificed for PI staining, we next sought to utilize a non-destructive means of quantifying tissue injury. Therefore, we measured leakage of LDH into BSC media over time. Because LDH is rapidly released from cells when membrane integrity is compromised (Bruce et al., 1995; Noraberg et al., 1999), LDH assay of culture media is a practical means of detecting cytotoxicity over time in the a single BSC sample without ever sacrificing the sample itself. LDH was released in mock BSCs at early time points, reflecting injury induced by the slice preparation procedure (Huuskonen et al., 2005). Beginning at 5dpi, media collected from T3A-infected BSCs showed an increasing amount of LDH release compared to mock (Fig. 2B). To identify the anatomical distribution of virus-induced tissue injury, BSCs were exposed to MTT and photographed. Focal patches of tissue injury (pale/white areas) were noted in both cortical and subcortical structures of reovirus infected BSCs (Fig. 2C).These studies indicated that reovirus replication in BSCs is associated with tissue injury and that such injury can be quantitatively and qualitatively measured in both slices and slice-associated tissue culture media.

Figure 2. Viral infection induces tissue injury in BSCs.

(A) At 7dpi, slices were incubated with 3µM propidium iodide for 1h prior to fluorescence determination by plate reader (N=3). Fluorescence was significantly greater (p=0.004) in reovirus-infected samples, suggesting viral-induced tissue injury. (B) Media was taken at specified time points and LDH was detected via colorimetric assay (N≥3). In mock samples, tissue injury was evident in the days following slicing, but decreased progressively. However, tissue injury was sustained in reovirus-infected BSCs, suggesting injury induced by the virus. (C) At 11dpi, BSC media was replaced with fresh media containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT and photographs were taken 45 minutes later. Live tissue cleaved the substrate to form purple formazan crystals, whereas dead tissue remained pale/white. Cortical and subcortical tissue death is evident in reovirus-infected BSCs.

Viral infection induces apoptosis in BSCs

Although LDH release is generally considered an index of necrosis, apoptosis followed by secondary necrosis can also result in LDH efflux (Zhan et al., 1999). To quantitatively determine if apptosis occurred in mock- and T3A- infected slices, time course fluorogenic Caspase 3 activity assays were performed on BSC lysates. Both mock- and T3A- infected BSCs showed early (1–3 dpi) activation of Caspase 3; however, at all time points taken after 5dpi, T3A-infected samples had significantly higher (p≤0.029) Caspase 3 activity compared to time-matched mock controls (Fig. 3A). To confirm reovirus-induced apoptosis in BSCs, cleaved Caspase 3 (cC3) was detected by Western blot of BSC lysates prepared at 4, 5, 6, and 7dpi (Fig. 3B). At these time points, T3A-infected BSCs consistently showed greater amounts of cC3 than controls. Activated Caspase 3 cleaves a number of downstream proteins including poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). Consistent with the fluorogenic substrate assays and detection of cC3 on Western blots, we found increased PARP cleavage in T3A-infected BSCs, as compared to mock samples from 4dpi onward (Fig 3C). These studies in cultured brain tissue establish that viral infection in BSCs is associated with apoptosis, as is the case in vivo (Beckham et al., 2007; Beckham et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 2005; Goody et al., 2007; Oberhaus et al., 1997; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002; Richardson-Burns et al., 2004).

Figure 3. Viral infection induces apoptosis in BSCs.

(A) BSCs (N≥3) were harvested into lysis buffer at indicated times before Caspase 3 activity was determined by fluorogenic activity assay. At all time points Caspase 3 activity was increased in reovirus-infected BSCs when compared to mock samples, with significant differences (p≤0.029) occurring at 7, 9, and 11dpi. (B) BSCs were harvested into lysis buffer at indicated times and ran on SDS-PAGE gel. Cleaved Caspase 3 (cC3), an apoptotic marker, was markedly increased in reovirus-infected BSCs. (C) BSCs were harvested into lysis buffer at specified times and ran on SDS-PAGE gel. PARP cleavage, a downstream result of Caspase 3 activation, was detected in reovirus-infected samples to a significant degree.

Inflammatory cytokines are released into the media of virus-infected BSCs

Our gene-expression studies on reovirus-infected brain tissue have revealed that a large group of cytokine and chemokine genes are upregulated during reovirus infection (Tyler et al., 2010). Cytokines act as important mediators of the host defense against viral infection by triggering intracellular antiviral pathways, initiating cell death, and/or modulating the immune response. We next wished to utilize BSCs to identify a brain-specific, virus-induced cytokine response. ELISArrays were performed on pooled media obtained from mock and reovirus-infected BSCs at 3dpi (media from 12hpi-3dpi), 5dpi (media from 3–5 dpi), and 9dpi (media from 7–9dpi). We initially screened for the presence of 17 cytokines (6Ckine, CXCL10, IFNγ, IL1α, IL1β, IL6, IL10, IL12, IL17A, KC, MCP-1, MIG, RANTES, SDF-1, TARC, TGFβ1, and TNFα). Of those 17, five cytokines (KC, RANTES, CXCL10, IL6, and MCP-1) were released into BSC media at detectable levels and four of these (KC, RANTES, CXCL10, and IL6) showed qualitative differences between T3A and mock-infected BSCs (data not shown). Absolute quantification of these four cytokines was carried out on 9dpi media (exposed to BSCs between 7–9dpi). Viral-infected BSCs released 5.9-fold greater KC (p=0.005), 13.5-fold greater RANTES (p=0.037), 30-fold greater CXCL10 (p=0.027), and 42-fold greater IL6 (p=0.006) when compared to mock-infected samples (Fig. 4). These data indicate that cells resident in brain tissue, are capable of producing KC, RANTES, CXCL10, and IL6 in response to viral infection and that this does not depend on systemic immune responses or non-resident, infiltrating immune cells.

Figure 4. Inflammatory cytokines are released into the media of virus-infected BSCs.

The four cytokines identified to be released in response to reovirus infection by ELISArray were quantified on individual ELISA plates. At 9dpi, media from experimentally similar wells was pooled into a single aliquot for independent experiments (N≥3) and serially diluted for quantification of cytokines based on standard curves (R2 >0.97). The release of KC (murine IL8 analog), RANTES, CXCL10, and IL6 was significantly greater (p≤0.037) in reovirus-infected BSCs.

Q-VD-OPh treatment limits tissue injury and apoptosis, but not viral replication, in virus-infected BSCs

We have recently shown in mice with transgenic knockout of the Caspase 3 gene (Caspase 3 −/−) that reovirus-induced CNS tissue injury is Caspase 3 dependant (Beckham et al., 2010). However, because of issues related to bioavailabilty and poor blood-brain penetration (Karatas et al., 2009), the outcomes of pharmacologic caspase inhibition in the virus-infected brain are unknown. We utilized the BSC system to test whether treatment of infected BSCs with the pan-caspase inhibitor, Q-VD-OPh, could limit viral-induced CNS tissue injury. Q-VD-OPh or a negative control peptide was applied to slices 12h after infection. Retreatment occurred with each media change (3dpi and 5dpi) and both slices and media were harvested on 7dpi or 11dpi. Q-VD-OPh treatment abrogated Caspase 3 activation as detected by immunoblot (Fig. 5A) and significantly reduced (p=0.008) viral-induced tissue injury as determined by LDH release (35% decrease versus negative control peptide-treated; Fig. 5B). Q-VD-OPh-mediated inhibition of virus-induced tissue injury was confirmed at a later time point by qualitative MTT assay (Fig. 5C). The caspase inhibitor had no significant effect on viral replication (Fig. 5D), a result paralleling that reported in vivo in which pharmacological inhibitors of apoptosis can be tissue protective without having a significant effect on viral replication (Kleinschmidt et al., 2007; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002; Samuel et al., 2007). These studies provide the first evidence that a pharmacological caspase inhibitor can inhibit reovirus-induced CNS tissue injury, and suggest that BSCs may be effectively used to screen potentially neuroprotective compounds for efficacy.

Figure 5. Q-VD-OPh treatment limits tissue injury and apoptosis, but not viral replication, in virus-infected BSCs.

Approximately 12h after being infected, negative control peptide or Q-VD-OPh was applied dropwise to the top of each slice at a concentration of 500 µg/mL to yield a final media concentration of 36.4 µg/mL. In a similar manner, additional treatments were made at each subsequent media change. (A) BSCs were harvested into lysis buffer at 7dpi and ran on SDS-PAGE gel. Cleaved Caspase 3 (cC3), an apoptotic marker, was detected in negative control treated samples but not in Q-VD-OPh treated samples. Western blot is representative of two independent experiments. (B) BSC media from mock (no virus/no peptide treatment), infected/negative control peptide treatment, and infected/O-VD-OPh treated samples (N=5) was harvested at 7dpi for LDH assay determination of tissue injury. With mock samples defined as a 0% injury reference and infected/negative control peptide defined as a 100% injury reference, infected/Q-Vd-OPh-treated BSCs had a 35% reduction (p=0.008) in terms of virus-induced injury. (C) At 11dpi, BSC media was replaced with fresh media containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT and photographs were taken 45 minutes later. Live tissue cleaved the substrate to form purple formazan crystals, whereas dead tissue remained pale/white. Virus-induced tissue death was evident in infected/negative control peptide-treated BSCs, but was inhibited in infected/Q-VD-OPh-treated samples. (D) BSCs were harvested at 7dpi for qRT-PCR determination of relative viral load, which was unchanged by Q-VD-OPh treatment (N=4). The infected/negative control peptide treated condition was defined as a reference value equal to 1.

DISCUSSION

Culturing brain tissue offers great promise for investigators of neurological disease because slices maintain brain cytoarchitecture, connectivity, and functional interactions between different cells types; yet, are extremely amendable to experimental manipulation (Cho et al., 2007; Gahwiler et al., 1997). We have adapted a brain slice culture model to the study of pathogenesis induced by a neurotropic virus, and by doing so have created powerful methods for the study of encephalitis. We demonstrate that pathological events known to occur in the murine models of encephalitis and human encephalitic patients are well replicated in the BSC system.

We have previously established an in vivo model of reovirus encephalitis, whereby infected animals develop rapidly progressive neurological disease accompanied by neuronal apoptosis and brain tissue injury (Beckham et al., 2007; Beckham et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 2005; Goody et al., 2007; Oberhaus et al., 1997; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002; Richardson-Burns et al., 2004). Reovirus infection of BSCs ex vivo recapitulates pathological events known to occur in the brains of reovirus-infected neonatal mice. In both in vivo and ex vivo models, reovirus specifically infects neurons (Fig. 1C), replicates to high titers (Fig. 1D & E), and induces apoptotic tissue injury (Fig. 2 and 3). The kinetics of viral replication and peak titers achieved are similar in the in vivo and ex vivo systems, with viral replication peaking in infected BSCs at 7–9dpi with titers in excess of 109 pfu/ml.

In both ex vivo and in vivo systems, the end of exponential phase of viral replication temporally correlates with the commencement of apoptotic tissue injury, here identified by virus-induced PI uptake (Fig. 2A), LDH release (Fig. 2B), reductions in tissue metabolic activity as assessed by MTT assay (Fig. 2C), and Caspase 3 activation (Fig. 3). We have previously shown that apoptosis in the reovirus-infected mouse brain occurs predominantly in infected neurons with limited bystander injury (Oberhaus et al., 1997; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002). Non-neuronal cells are not infected to any significant degree in the in vivo and ex vivo settings (Fig. 1). Because ex vivo BSCs do not allow for migration of extraneural inflammatory cells, we can now definitively conclude that reovirus-induced neuronal apoptosis can occur in the absence of an infiltrating host cell inflammatory response. This finding is consistent with observations in vivo, indicating that tissue injury precedes the development of any substantial cellular inflammatory response.

Having demonstrated that the BSC system reproduces in vivo viral pathogenesis in the absence of an adaptive immune response, we next utilized this system to characterize the innate, “brain-specific” release of cytokines in response to viral infection. In the in vivo setting, it is virtually impossible to distinguish the relative contributions of innate CNS cytokine responses produced by resident cells from those which depend on systemic events or are mediated via infiltrating inflammatory cells. Using an unbiased screen for cytokines, we found significantly higher levels of IL6, CXCL10, RANTES, and KC (murine IL8 analog), in the media of reovirus-infected BSCs, when compared to mock-infected media (Fig. 4).

A recent analysis of human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples revealed that IL6, IL8, and RANTES were present at significantly higher levels in patients with encephalitis compared to healthy controls; whereas, all other cytokines screened were similar between groups (Kalita et al., 2010). Elevation of CSF CXCL10 and IL8 also occurs in adults during the acute phase of influenza A-associated encephalopathy (Lee et al., 2010). Several other studies have confirmed that encephalitis of varying viral etiologies is associated with high levels of IL6 in CSF and/or serum (Aiba et al., 2001; Ichiyama et al., 2009; Kamei et al., 2009) and it was found that the vast majority of patients afflicted with Japanese encephalitis had increased levels of CSF IL8 in comparison to healthy controls (Singh et al., 2000). Notably, individuals with lethal Japanese encephalitis generally had higher levels of CSF or plasma IL8 levels than those who recovered. Further suggestive of the prognostic value of elevated cytokines, a large study of patients with Japanese encephalitis found that nonsurvivors, in comparison to survivors, had raised levels of CSF IL6 and IL8 in addition to raised plasma levels of RANTES (Winter et al., 2004). In aggregate, these studies suggest that the same cytokines we have shown are produced in reovirus-infected BSCs (IL6, CXCL10, RANTES, and IL8) are important regulators of encephalitis in human patients.

Differentiating cytokines produced by CNS resident cells from those produced by peripheral inflammatory cells in the context of encephalitis may prove useful for diagnosis and treatment. The exact source of any given cytokine (CNS vs. peripheral) is often inferred by calculation of CSF to plasma concentration ratio. This strategy has led one group to conclude that during enterovirus 71-associated encephalitis, IL8 and CXCL10 are synthesized within the brain, whereas RANTES is not (Wang et al., 2008). The present study unequivocally demonstrates that virus-infected brain tissue is capable of synthesizing IL6, CXCL10, RANTES, and IL8 (Fig. 4).

We have previously shown that following reovirus infection, Caspase 3 knockout mice (Caspase 3 −/−) have a significant survival benefit and less CNS tissue injury when compared to wild-type controls, suggesting that pharmacologic inhibition of Caspase 3 could be an effective treatment for viral encephalitis (Beckham et al., 2010). Although we have demonstrated that reovirus-induced cardiac injury is effectively reduced with peptide-based caspase inhibitors (Debiasi et al., 2004), effective delivery of such agents to the intact brain is challenging due to issues related to drug solubility and blood-brain barrier permeability (Karatas et al., 2009). We now demonstrate that Q-VD-OPh treatment limits apoptosis and injury in reovirus-infected BSCs (Fig. 5A, B, and C). Q-VD-OPh-mediated tissue protection was independent of any parallel effect on viral replication (Fig. 5D). Studies using both pharmacological and genetic approaches, have demonstrated similar protection against virus-induced neuronal death in the absence of any effect on viral load (Kleinschmidt et al., 2007; Richardson-Burns et al., 2002; Samuel et al., 2007). We conclude that the BSC system allows chemical compounds to be initially evaluated without confounding effects of bioavailability and systemic metabolism. These studies establish the feasibility of using BSCs, as a disease-relevant model, to screen potential anti-viral and neuroprotective agents for efficacy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by RO1NS050138 (K.L.T), RO1NS051403 (K.L.T), and a VA Merit Grant (K.L.T).

J.D.B. was supported by a Mentored Clinical Science Development award (5K08AI076518, 5K08AI076518-02S1 and 5K08AI076518-03S1).

K.R.D. was supported by an institutional MST Program training grant (T32 GM008497) and a National Research Service Award for Predoctoral MD/PhD Fellows (F30 NS071630).

The authors extend their gratitude to the members of the K.L.T. and J.D.B. laboratories for many helpful discussions. We thank David Davis for his advice regarding cryosectioning of brain slices and Lai Kuan Goh for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BSC

brain slice culture

- pfu

plaque forming units

- T3

serotype 3 reovirus

- T3A

Reovirus serotype 3 strain Abney

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- dpi

days post-infection

- cC3

cleaved Caspase 3

- cPARP

cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- i.c.

intracerebral

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- WNV

West Nile virus

- HSV

herpes simplex virus

- JEV

Japanese encephalitis virus

- RANTES

regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted

- IL6

interleukin 6

- IL8

interleukin 8

- Q-VD-OPH

quinolyl-valyl-O-methylaspartyl-[-2,6-difluorophenoxy]-methyl ketone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba H, Mochizuki M, Kimura M, Hojo H. Predictive value of serum interleukin-6 level in influenza virus-associated encephalopathy. Neurology. 2001;57:295–299. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akimitsu T, Kurisu K, Hanaya R, Iida K, Kiura Y, Arita K, Matsubayashi H, Ishihara K, Kitada K, Serikawa T, Sasa M. Epileptic seizures induced by N-acetyl-L-aspartate in rats: in vivo and in vitro studies. Brain Res. 2000;861:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckham JD, Goody RJ, Clarke P, Bonny C, Tyler KL. Novel strategy for treatment of viral central nervous system infection by using a cell-permeating inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J. Virol. 2007;81:6984–6992. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00467-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckham JD, Tuttle KD, Tyler KL. Caspase-3 activation is required for reovirus-induced encephalitis in vivo. J. Neurovirol. 2010;16:306–317. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.499890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun E, Zimmerman T, Ben Hur T, Reinhartz E, Fellig Y, Panet A, Steiner I. Neurotropism of herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain organ cultures. Journal of General Virology. 2006;87:2827–2837. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce AJ, Sakhi S, Schreiber SS, Baudry M. Development of kainic acid and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid toxicity in organotypic hippocampal cultures. Exp. Neurol. 1995;132:209–219. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bywood PT, Johnson SM. Mitochondrial complex inhibitors preferentially damage substantia nigra dopamine neurons in rat brain slices. Exp. Neurol. 2003;179:47–59. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SF, Huang CC, Wu HM, Chen SH, Liang YC, Hsu KS. Seizure, neuron loss, and mossy fiber sprouting in herpes simplex virus type 1-infected organotypic hippocampal cultures. Epilepsia. 2004;45:322–332. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.37403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho S, Liu D, Fairman D, Li P, Jenkins L, McGonigle P, Wood A. Spatiotemporal evidence of apoptosis-mediated ischemic injury in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Neurochem. Int. 2004;45:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho S, Wood A, Bowby MR. Brain slices as models for neurodegenerative disease and screening platforms to identify novel therapeutics. Current Neuropharmacology. 2007;5:19–33. doi: 10.2174/157015907780077105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke P, Beckham JD, Leser JS, Hoyt CC, Tyler KL. Fas-mediated apoptotic signaling in the mouse brain following reovirus infection. J. Virol. 2009;83:6161–6170. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02488-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke P, Debiasi RL, Goody R, Hoyt CC, Richardson-Burns S, Tyler KL. Mechanisms of reovirus-induced cell death and tissue injury: role of apoptosis and virus-induced perturbation of host-cell signaling and transcription factor activation. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:89–115. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debiasi RL, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Richardson-Burns S, Tyler KL. Central nervous system apoptosis in human herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus encephalitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;186:1547–1557. doi: 10.1086/345375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debiasi RL, Robinson BA, Sherry B, Bouchard R, Brown RD, Rizeq M, Long C, Tyler KL. Caspase inhibition protects against reovirus-induced myocardial injury in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 2004;78:11040–11050. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11040-11050.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debiasi RL, Squier MK, Pike B, Wynes M, Dermody TS, Cohen JJ, Tyler KL. Reovirus-induced apoptosis is preceded by increased cellular calpain activity and is blocked by calpain inhibitors. J. Virol. 1999;73:695–701. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.695-701.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehrengruber MU, Lundstrom K, Schweitzer C, Heuss C, Schlesinger S, Gahwiler BH. Recombinant Semliki Forest virus and Sindbis virus efficiently infect neurons in hippocampal slice cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S A. 1999;96:7041–7046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finley M, Fairman D, Liu D, Li P, Wood A, Cho S. Functional validation of adult hippocampal organotypic cultures as an in vitro model of brain injury. Brain Res. 2004;1001:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedl G, Hofer M, Auber B, Sauder C, Hausmann J, Staeheli P, Pagenstecher A. Borna disease virus multiplication in mouse organotypic slice cultures is site-specifically inhibited by gamma interferon but not by interleukin-12. J. Virol. 2004;78:1212–1218. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1212-1218.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gahwiler BH, Capogna M, Debanne D, McKinney RA, Thompson SM. Organotypic slice cultures: a technique has come of age. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:471–477. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gille G, Hung ST, Reichmann H, Rausch WD. Oxidative stress to dopaminergic neurons as models of Parkinson's disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1018:533–540. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goody RJ, Beckham JD, Rubtsova K, Tyler KL. JAK-STAT signaling pathways are activated in the brain following reovirus infection. J. Neurovirol. 2007;13:373–383. doi: 10.1080/13550280701344983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin DE. Neuronal cell death in alphavirus encephalomyelitis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;289:57–77. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27320-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris-White ME, Balverde Z, Lim GP, Kim P, Miller SA, Hammer H, Galasko D, Frautschy SA. Role of LRP in TGFbeta2-mediated neuronal uptake of Abeta and effects on memory. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;77:217–228. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huuskonen J, Suuronen T, Miettinen R, van GT, Salminen A. A refined in vitro model to study inflammatory responses in organotypic membrane culture of postnatal rat hippocampal slices. J. Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichiyama T, Ito Y, Kubota M, Yamazaki T, Nakamura K, Furukawa S. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid levels of cytokines in acute encephalopathy associated with human herpesvirus-6 infection. Brain Dev. 2009;31:731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung YJ, Park SJ, Park JS, Lee KE. Glucose/oxygen deprivation induces the alteration of synapsin I and phosphosynapsin. Brain Res. 2004;996:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalita J, Srivastava R, Mishra MK, Basu A, Misra UK. Cytokines and chemokines in viral encephalitis: a clinicoradiological correlation. Neurosci. Lett. 2010;473:48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamei S, Taira N, Ishihara M, Sekizawa T, Morita A, Miki K, Shiota H, Kanno A, Suzuki Y, Mizutani T, Itoyama Y, Morishima T, Hirayanagi K. Prognostic value of cerebrospinal fluid cytokine changes in herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Cytokine. 2009;46:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karatas H, Aktas Y, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Bodur E, Yemisci M, Caban S, Vural A, Pinarbasli O, Capan Y, Fernandez-Megia E, Novoa-Carballal R, Riguera R, Andrieux K, Couvreur P, Dalkara T. A nanomedicine transports a peptide caspase-3 inhibitor across the blood-brain barrier and provides neuroprotection. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:13761–13769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4246-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khosravani H, Carlen PL, Velazquez JL. The control of seizure-like activity in the rat hippocampal slice. Biophys. J. 2003;84:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74888-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinschmidt MC, Michaelis M, Ogbomo H, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Inhibition of apoptosis prevents West Nile virus induced cell death. BMC. Microbiol. 2007;7:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee N, Wong CK, Chan PK, Lindegardh N, White NJ, Hayden FG, Wong EH, Wong KS, Cockram CS, Sung JJ, Hui DS. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza A infection in adults. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:139–142. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.090077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Losi G, Cammarota M, Chiavegato A, Gomez-Gonzalo M, Carmignoto G. A new experimental model of focal seizures in the entorhinal cortex. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1493–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer D, Fischer H, Schneider U, Heimrich B, Schwemmle M. Borna disease virus replication in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures from rats results in selective damage of dentate granule cells. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:11716–11723. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11716-11723.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michaelis M, Kleinschmidt MC, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Minocycline inhibits West Nile virus replication and apoptosis in human neuronal cells. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:981–986. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noraberg J, Kristensen BW, Zimmer J. Markers for neuronal degeneration in organotypic slice cultures. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 1999;3:278–290. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(98)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oberhaus SM, Smith RL, Clayton GH, Dermody TS, Tyler KL. Reovirus infection and tissue injury in the mouse central nervous system are associated with apoptosis. J. Virol. 1997;71:2100–2106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2100-2106.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perkins D, Gyure KA, Pereira EF, Aurelian L. Herpes simplex virus type 1-induced encephalitis has an apoptotic component associated with activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J. Neurovirol. 2003;9:101–111. doi: 10.1080/13550280390173427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raschilas F, Wolff M, Delatour F, Chaffaut C, De BT, Chevret S, Lebon P, Canton P, Rozenberg F. Outcome of and prognostic factors for herpes simplex encephalitis in adult patients: results of a multicenter study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35:254–260. doi: 10.1086/341405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richardson-Burns SM, Kominsky DJ, Tyler KL. Reovirus-induced neuronal apoptosis is mediated by caspase 3 and is associated with the activation of death receptors. J. Neurovirol. 2002;8:365–380. doi: 10.1080/13550280260422677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richardson-Burns SM, Tyler KL. Regional differences in viral growth and central nervous system injury correlate with apoptosis. J. Virol. 2004;78:5466–5475. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5466-5475.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson-Burns SM, Tyler KL. Minocycline delays disease onset and mortality in reovirus encephalitis. Exp. Neurol. 2005;192:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samuel MA, Morrey JD, Diamond MS. Caspase 3-dependent cell death of neurons contributes to the pathogenesis of West Nile virus encephalitis. J. Virol. 2007;81:2614–2623. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02311-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiff LA, Nibert ML, Tyler KL. In: Orthoeoviruses and their replication. Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Philadelphia, PA: Fields Virology Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1853–1915. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherer TB, Betarbet R, Testa CM, Seo BB, Richardson JR, Kim JH, Miller GW, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A, Greenamyre JT. Mechanism of toxicity in rotenone models of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:10756–10764. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10756.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimizu K, Matsubara K, Ohtaki K, Shiono H. Paraquat leads to dopaminergic neural vulnerability in organotypic midbrain culture. Neurosci. Res. 2003;46:523–532. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(03)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh A, Kulshreshtha R, Mathur A. Secretion of the chemokine interleukin-8 during Japanese encephalitis virus infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2000;49:607–612. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-7-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solomon T. Flavivirus encephalitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:370–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoppini L, Buchs PA, Muller D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous-tissue. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1991;37:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan K, Patel S, Gandhi N, Chow F, Rumbaugh J, Nath A. Burden of neuroinfectious diseases on the neurology service in a tertiary care center. Neurology. 2008;71:1160–1166. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327526.71683.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsao CH, Su HL, Lin YL, Yu HP, Kuo SM, Shen CI, Chen CW, Liao CL. Japanese encephalitis virus infection activates caspase-8 and -9 in a FADD-independent and mitochondrion-dependent manner. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:1930–1941. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/000182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsutsui Y, Kawasaki H, Kosugi I. Reactivation of latent cytomegalovirus infection in mouse brain cells detected after transfer to brain slice cultures. J. Virol. 2002;76:7247–7254. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7247-7254.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyler KL. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: encephalitis and meningitis, including Mollaret's. Herpes. 2004;11 Suppl 2:57A–64A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyler KL, Leser JS, Phang TL, Clarke P. Gene expression in the brain during reovirus encephalitis. J. Neurovirol. 2010;16:56–71. doi: 10.3109/13550280903586394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tyler KL, Sokol RJ, Oberhaus SM, Le M, Karrer FM, Narkewicz MR, Tyson RW, Murphy JR, Low R, Brown WR. Detection of reovirus RNA in hepatobiliary tissues from patients with extrahepatic biliary atresia and choledochal cysts. Hepatology. 1998;27:1475–1482. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang SM, Lei HY, Yu CK, Wang JR, Su IJ, Liu CC. Acute chemokine response in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid of children with enterovirus 71-associated brainstem encephalitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198:1002–1006. doi: 10.1086/591462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winter PM, Dung NM, Loan HT, Kneen R, Wills B, Thu lT, House D, White NJ, Farrar JJ, Hart CA, Solomon T. Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in humans with Japanese encephalitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;190:1618–1626. doi: 10.1086/423328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang XF, Schmidt BF, Rode DL, Rothman SM. Optical suppression of experimental seizures in rat brain slices. Epilepsia. 2010;51:127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhan Y, van de Water B, Wang Y, Stevens JL. The roles of caspase-3 and bcl-2 in chemically-induced apoptosis but not necrosis of renal epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:6505–6512. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]