Abstract

EMBO J 30 6, 1093–1103 (2011); published online February 18 2011

The erythroid versus myeloid lineage fate decision controlled by cross-antagonism between GATA1 and PU.1 serves as a mechanistic paradigm for transcription factor interplay during lineage specification. In this issue of The EMBO Journal, Monteiro et al (2011) examined this paradigm in blood populations in zebrafish embryos, and demonstrated that, unexpectedly, the regulatory interactions between GATA1 and PU.1 lead to different outcomes depending on the cellular contexts and the development stages. GATA1/PU.1 cross-antagonism is also modulated by a third factor transcriptional intermediate factor 1γ (TIF1γ), a chromatin-associated haematopoietic regulator.

Vertebrate haematopoiesis is a highly orchestrated process coordinated by a complex regulatory network of lineage-restricted transcription factors (Orkin and Zon, 2008). The cross-antagonism between GATA1 and PU.1 during erythroid–myeloid lineage bifurcation represents one of the earliest decisions during haematopoietic development and serves as a paradigm for the transcription factor interplay underlying cell fate switching and lineage reprogramming (Graf and Enver, 2009). GATA1 is a critical factor for erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation and controls the expression of genes specific for these lineages. In contrast, PU.1 is required for myeloid cell differentiation and mediates the induction of myelomonocytic genes. From overexpression studies in both cell lines and primary cells, it is evident that GATA1 and PU.1 can specify erythroid and myeloid lineages by antagonizing each other's transcriptional activity (Graf, 2002). GATA1 and PU.1 also control their own expression by forming autoregulatory loops. Genetic studies have validated the mutual antagonism between GATA1 and PU.1 by loss-of-function studies in zebrafish embryos (Galloway et al, 2005; Rhodes et al, 2005) and by using GATA1 and PU.1 transcriptional reporters in mice (Arinobu et al, 2007).

The cross-antagonistic model between GATA1 and PU.1 provides a simplified scheme for lineage commitment for the erythroid/myeloid branch point during haematopoietic development. However, the presence of additional binding partners for both proteins may create a far more complex regulatory network that includes additional inputs (Chickarmane et al, 2009). The study by Monteiro et al (2011) has demonstrated that one such factor, TIF1γ, is involved in erythroid/myeloid lineage fate decision by way of modulating GATA1 and PU.1 expression.

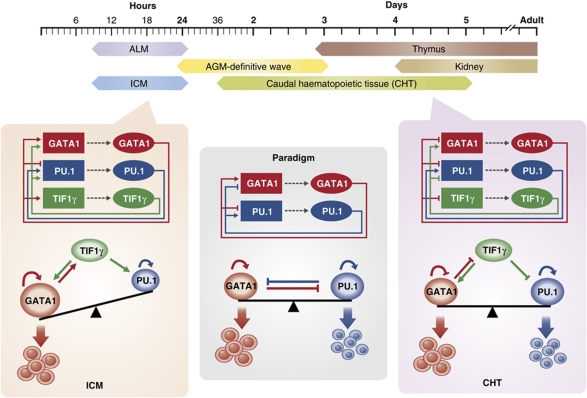

The findings build on a careful analysis of moonshine (montg234), a mutant zebrafish with defects in erythroid maturation due to loss of TIF1γ (Ransom et al, 2004). In the caudal haematopoietic tissue (CHT, analogous to fetal liver in mammals), deficiency in TIF1γ leads to loss of definitive erythroid cells accompanied by a dramatic increase in myeloid cells (Monteiro et al, 2011). As loss of TIF1γ affects erythroid versus myeloid outcomes from haematopoietic progenitors in CHT, the researchers investigated the epistatic relationships between TIF1γ, GATA1 and PU.1. By morpholino-mediated knockdown followed by gene expression analysis, Monteiro et al demonstrated that there is a deviation from the GATA1/PU.1 cross-antagonistic paradigm in this population of blood precursors. Specifically, PU.1 antagonizes GATA1 activity and regulates itself positively, while GATA1 antagonizes PU.1 expression, consistent with the paradigm. However, GATA1 regulates itself negatively, in contrary to the paradigm (Figure 1). Moreover, TIF1γ modulates the GATA1/PU.1 interplay by favouring GATA1 expression over PU.1 expression, consistent with the expansion of myeloid output in the TIF1γ-deficient moonshine embryos. These findings indicate that the GATA1/PU.1 regulatory interplay may be cell context-dependent and is modulated by TIF1γ.

Figure 1.

GATA1/PU.1 cross-antagonistic paradigm takes different forms during haematopoiesis in zebrafish embryos. A scheme of developmental time windows for haematopoiesis sites in the zebrafish is shown on the top. A schematic representation of the classical GATA1/PU.1 cross-antagonistic paradigm is shown in the middle panel. In the ICM, TIF1γ is required for the expression of both GATA1 and PU.1 (left panel). Here, GATA1 antagonizes PU.1, but PU.1 does not repress GATA1 expression. In the CHT, TIF1γ favours the expression of GATA1 over PU.1, while GATA1 and PU.1 antagonize each other's activity (right panel). Note that while PU.1 positively autoregulates in all the haematopoietic progenitors, the autoregulatory status of GATA1 varies from stimulatory (in ICM) to repressive (in CHT). The interplay among GATA1, PU.1 and TIF1γ affects erythroid/myeloid lineage output at different haematopoietic sites in zebrafish embryos.

Having established TIF1γ as an important modifier of the GATA1/PU.1 interplay, Monteiro et al next examined this regulatory triad in other blood populations within the zebrafish embryos. Surprisingly, in the primitive haematopoietic tissue intermediate cell mass (ICM) and pro-definitive erythromyeloid progenitors (EMPs), the autoregulatory status of GATA1 varies from stimulatory (in ICM) to no autoregulation (in EMP). Therefore, there is an unappreciated complexity of the GATA1/PU.1 cross-antagonistic paradigm in haematopoietic progenitors in vivo. Although the model takes different forms in different blood-producing populations, a unified theme is still apparent. Particularly, PU.1 always antagonizes GATA1 along with stimulating its own expression wherever myelopoiesis occurs. Similarly, GATA1 always antagonizes PU.1 expression wherever erythropoiesis occurs. However, the autoregulatory status of GATA1 may vary from autostimulation to autorepression depending on the cellular context. Importantly, the erythroid/myeloid output is modulated by a third factor TIF1γ, which controls the differential expression of GATA1 and PU.1 in the definitive CHT. Regulation through TIF1γ differs in primitive erythroid and pro-definitive EMPs, in which it positively regulates both GATA1 and PU.1 (Figure 1). Thus, the work of Monteiro et al adds to the existing literature an important example of how overly simplified paradigms may need to be modified according to cellular context.

A better understanding of the erythroid versus myeloid lineage fate decision necessitates a more comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms underlying this sophisticated transcription factor interplay. Earlier studies from forced expression experiments demonstrated that GATA1 and PU.1 functionally cross-antagonize each other through direct physical interaction (Graf and Enver, 2009). Specifically, ectopically expressed GATA1 inhibits PU.1 activity by displacing c-Jun, an important cofactor of PU.1 for the myelomonocytic program. Conversely, PU.1 expressed in erythroid precursors interacts with GATA1 and recruits a repressive complex consisting of the RB protein and the histone methyltransferase SUV39H. The precise role of TIF1γ in transcriptional regulation is less defined. TIF1γ encodes an E3 ubiquitin–protein ligase composed of multiple conserved domains implicated in protein–protein interaction and chromatin association, including the RBCC domain, PHD finger and bromodomain. Recent work by Bai et al (2010) has demonstrated that TIF1γ controls erythroid gene expression by regulating transcription elongation. By a genetic suppressor screen, Bai et al initially demonstrated that loss of function of Pol II-associated factors PAF or DSIF rescued erythroid gene transcription in TIF1γ-deficient moonshine mutant. Further biochemical and genetic analysis established physical interactions among TIF1γ, erythroid-specific SCL complexes, and the positive elongation factors p-TEFb and FACT. Therefore, TIF1γ couples the blood-specific transcriptional complex with Pol II elongation machinery to promote the transcription elongation of erythroid-selective genes (Bai et al, 2010). It remains to be determined how TIF1γ mediates gene repression. TIF1γ may directly repress its target genes through yet-to-be-defined mechanisms. Alternatively, it may activate a set of intermediate repressor proteins. It will also need to be clarified, in future studies, whether GATA1 and PU.1 are involved in TIF1γ's activity, and if so, how. It is formally possible that all three factors can function through physical interactions within a chromatin environment. Thus, future genome-wide chromatin occupancy studies should provide some clues into the molecular understanding of this critical lineage bifurcation process. Regardless of the exact mechanisms, Monteiro et al's study reveals sophisticated transcription factor interplay during haematopoiesis. The interactions among key lineage-specifying regulators can be modulated depending on the cellular contexts and the development stages.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Xiaoying Bai and Leonard I Zon for their comments. Stuart H Orkin is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). Jian Xu is supported by the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation-HHMI Post-Doctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Arinobu Y, Mizuno S, Chong Y, Shigematsu H, Iino T, Iwasaki H, Graf T, Mayfield R, Chan S, Kastner P, Akashi K (2007) Reciprocal activation of GATA-1 and PU.1 marks initial specification of hematopoietic stem cells into myeloerythroid and myelolymphoid lineages. Cell Stem Cell 1: 416–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Kim J, Yang Z, Jurynec MJ, Akie TE, Lee J, LeBlanc J, Sessa A, Jiang H, DiBiase A, Zhou Y, Grunwald DJ, Lin S, Cantor AB, Orkin SH, Zon LI (2010) TIF1gamma controls erythroid cell fate by regulating transcription elongation. Cell 142: 133–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chickarmane V, Enver T, Peterson C (2009) Computational modeling of the hematopoietic erythroid-myeloid switch reveals insights into cooperativity, priming, and irreversibility. PLoS Comput Biol 5: e1000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JL, Wingert RA, Thisse C, Thisse B, Zon LI (2005) Loss of gata1 but not gata2 converts erythropoiesis to myelopoiesis in zebrafish embryos. Dev Cell 8: 109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T (2002) Differentiation plasticity of hematopoietic cells. Blood 99: 3089–3101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T, Enver T (2009) Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature 462: 587–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro R, Pouget C, Patient R (2011) The gata1/pu.1 lineage fate paradigm varies between blood populations and is modulated by tif1γ. EMBO J 30: 1093–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin SH, Zon LI (2008) Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell 132: 631–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom DG, Bahary N, Niss K, Traver D, Burns C, Trede NS, Paffett-Lugassy N, Saganic WJ, Lim CA, Hersey C, Zhou Y, Barut BA, Lin S, Kingsley PD, Palis J, Orkin SH, Zon LI (2004) The zebrafish moonshine gene encodes transcriptional intermediary factor 1gamma, an essential regulator of hematopoiesis. PLoS Biol 2: E237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, Hagen A, Hsu K, Deng M, Liu TX, Look AT, Kanki JP (2005) Interplay of pu.1 and gata1 determines myelo-erythroid progenitor cell fate in zebrafish. Dev Cell 8: 97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]