Abstract

A practical way to reduce the cost of surveying single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in a large number of individuals is to measure the allele frequencies in pooled DNA samples. PyrosequencingTM has been frequently used for this application because signals generated by this approach are proportional to the amount of DNA templates. The PyrosequencingTM pyrogram is determined by the dispensing order of dNTPs, which is usually designed based on the known SNPs to avoid asynchronistic extensions of heterozygous sequences. Therefore, utilizing the pyrogram signals to identify de novo SNPs in DNA pools has never been undertook. Here, in this study we developed an algorithm to address this issue. With the sequence and pyrogram of the wild-type allele known in advance, we could use the pyrogram obtained from the pooled DNA sample to predict the sequence of the unknown mutant allele (de novo SNP) and estimate its allele frequency. Both computational simulation and experimental PyrosequencingTM test results suggested that our method performs well. The web interface of our method is available at http://life.nctu.edu.tw/∼yslin/PSM/.

INTRODUCTION

In human genomes, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) compose the majority of genetic variation, and may, therefore, largely determine the differences among individuals. SNPs among human populations have been extensively explored in this decade (1,2). Their abundance and high potential for automation make them become a powerful tool for identifying genetic factors, especially those contributing to complex disease susceptibility.

However, it is still expensive and time consuming to perform SNP genotyping in a large number of individuals (3). An efficient and low-cost method is important for large-scale SNP scoring. The application of current genotyping platforms for pooled DNA samples might be a practical way (3), because allele frequencies in a group of individuals could be measured using far fewer reactions (4). DNA pooling combined with whole genome analysis is usually considered as the first step to identify potential genetic markers for subsequent genotyping of individuals (5–7). Several genotyping methods suitable for measuring frequencies of SNPs in DNA pools have been proposed in the literatures (3,8).

PyrosequencingTM, which was first described in 1988 (9), might be one of the most successful non-Sanger methods developed in the two decades (10). Instead of using 3′-modified dNTPs to terminate DNA polymerization, PyrosequencingTM adds dNTP bases one at a time in limiting amounts to control DNA synthesis. The dNTPs are dispensed in a specific order. DNA polymerase extends the primer while the complementary dNTP is added and pauses when it encounters a noncomplementary base. The reinitiation of DNA synthesis follows the addition of the next complementary dNTP (10). As a nonfluorescence technique, PyrosequencingTM measures the release of inorganic pyrophosphate, which is proportionally transformed into visible light by a cascade of enzymatic reactions (11,12). The generated light is recorded as a series of peaks called a pyrogram, which represents the order of complementary dNTPs and implies the underlying DNA sequence (10).

Because the light generated by the PyrosequencingTM reactions is proportional to the amount of DNA template, this technique was frequently used to measure allelic gene expression (13,14) or allele frequency, including in tumor tissue (15), in parasites or microbial community (16,17) and in DNA pools (18–22). PyrosequencingTM has been recommended for allele frequency studies because of its high reliability in detecting variations between populations (23,24).

The ‘next-generation’ sequencing technology, including the array-based pyrosequencing (454 sequencing platform), has recently been applied for high-throughput resequencing and SNP genotyping (8,25). However, although this strategy is powerful, the expense makes it less applicable when our research interest only focuses on specific genes in specific populations. At present, most clinical laboratories use the low-throughput PyrosequencingTM platform to identify known alleles (among organisms, strains or SNPs) (26). In this study, ‘PyrosequencingTM’ refers to this core technology but not the array-based 454 sequencing platform. No study has applied PyrosequencingTM for de novo SNP discovery (10). It is because base-calling for de novo SNPs is difficult and still performed manually (27). The PyrosequencingTM pyrogram is determined by the dispensing order of dNTPs. To avoid asynchronistic extensions of heterozygous sequences, the dispensing order used to be carefully designed (10). Current sequencing software cannot detect new polymorphisms in pooled DNA samples (27), including the application of multiplex genotyping techniques (27–30).

Here, in this study, we developed an algorithm based on the normality test and dynamic programming to automatically read the pyrogram profile when unexpected mutations occurred. The performance of our method was evaluated using both computational simulation and experimental PyrosequencingTM assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

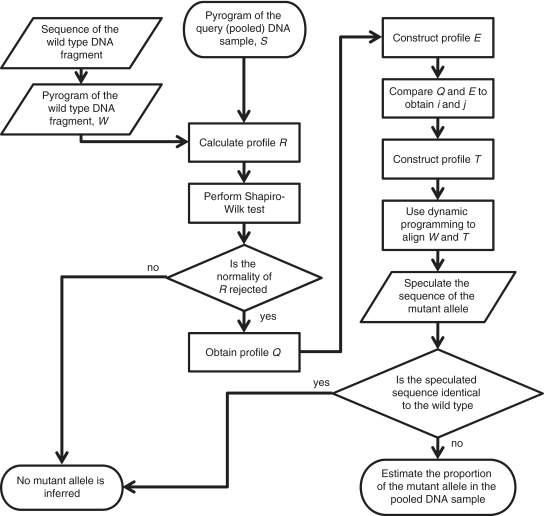

The object of our method is using a pyrogram of a pooled DNA sample to estimate the frequency of the mutant allele in the sample and predict its sequence. The sequence and pyrogram from the wild-type allele have to be known in advance. The flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the algorithm developed in this study.

The expected pyrogram

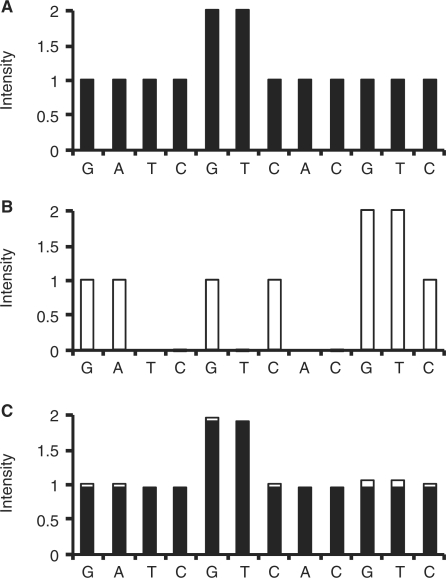

To illustrate our method, we used a DNA fragment, GATCGGTTCACGTC, as an example, and assumed that this is the wild-type allele. The PyrosequencingTM dispensing order of dNTPs, GATCGTCACGTC, was designated to complement this DNA fragment. Figure 2A shows the pyrogram profile, W, for this wild-type fragment. The signal intensity for the nth dispensed dNTP in W is represented as wn. To simulate the real experiments, we defined coefficient of variation (CV) here as the standard deviation divided by the mean, and therefore obtained wn:

CV reflects the degree of precision for the PyrosequencingTM experiments. In this example, we let CV = 0.5%.

Figure 2.

(A) The hypothetical pyrogram profile, W, for the wild-type DNA fragment, GATCGGTTCACGTC; (B) the hypothetical pyrogram profile, M, for the mutant allele, GAGCGGTTCACGTC; (C) the expected pyrogram profile, S, for the pooled DNA sample with 95% wild-type allele and 5% mutant allele (95% black bars + 5% white bars). All the three pyrogram profiles were simulated under the same PyrosequencingTM dispensing order of dNTPs, GATCGTCACGTC, with CV = 0.5%.

For a mutant allele with a thymine-to-guanine substitution at the third nucleotide, GAGCGGTTCACGTC, asynchronistic extensions would occur under the designated dispensing order of dNTPs described above. Figure 2B displays the pyrogram profile, M, for this mutant allele. Similarly, we could also obtain mn:

In this circumstance, for a pooled DNA sample with 95% wild-type allele and 5% mutant allele, the expected pyrogram profile, S, would be nonsynchronistic as shown in Figure 2C. The pyrogram could be predicted using the equation

where sn is the signal intensity at the nth dispensing site for S, and a represents the proportion of wild-type allele in the DNA sample. In this example, a = 0.95.

The pyrogram to be tested

Assume that we have two unknown pooled DNA samples to be tested, and that one is actually composed of 95% wild-type allele and 5% mutant allele as in Figure 2C, while the other is composed of 100% wild-type allele as in Figure 2A. Their pyrograms, Sblue and Sred, respectively, were simulated with CV = 0.5% and represented in Figure 3A. To distinguish Sblue and Sred, we calculated the ratio profile, R:

The obtained Rblue and Rred are shown in Figure 3B. Note that pyrogram Sblue has nonsynchronistic extensions. Therefore, when the added nucleotide during PyrosequencingTM is not complementary to the mutant allele (for Sblue, n = 3, 4, 6, 8 and 9), decreased signal would be detected. For these dispensing sites,  ; while for the other sites,

; while for the other sites,  because

because  > 0. As a result, the values of Rblue would not be normally distributed. By contrast, the distribution of the values of Rred should be normal, and

> 0. As a result, the values of Rblue would not be normally distributed. By contrast, the distribution of the values of Rred should be normal, and  . We performed the Shapiro–Wilk test (31) on the normality of R, and sorted the values of R to obtain another profile, Q:

. We performed the Shapiro–Wilk test (31) on the normality of R, and sorted the values of R to obtain another profile, Q:

The relative cumulative frequencies of Qblue and Qred are shown in Figure 3C. When the normality of R is rejected, possible nonsynchronistic extensions are implied. We therefore constructed an expected cumulative normal distribution, E, with the same mean and standard deviation as Q, and compared Q with E. In our example, the blue circles and the blue crosses represent Qblue and Eblue, respectively (Figure 3C). As described above, for certain dispensing sites,  , which corresponds to a group of the smallest values of Qblue. To estimate the value of ablue, we looked for a variable i that can maximize

, which corresponds to a group of the smallest values of Qblue. To estimate the value of ablue, we looked for a variable i that can maximize  , and then found another variable j that can minimize

, and then found another variable j that can minimize  . We then speculated that

. We then speculated that

In our example, i = 5, j = 4, and  (Figure 3C).

(Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

(A) The blue bars represent the pyrogram, Sblue, of a pooled DNA sample composed of 95% wild-type allele and 5% mutant allele as in Figure 2C. The red bars represent the pyrogram, Sred, of a DNA sample composed of 100% wild-type allele. The two pyrogram profiles were simulated with CV = 0.5%. (B) The ratio profiles Rblue and Rred. (C) The relative cumulative frequencies of profiles Qblue (blue circles) and Qred (red triangles). The blue crosses represent the expected cumulative normal distribution, Eblue, which has the same mean and standard deviation as Qblue. See the main text for the details.

The sequence of the mutant allele

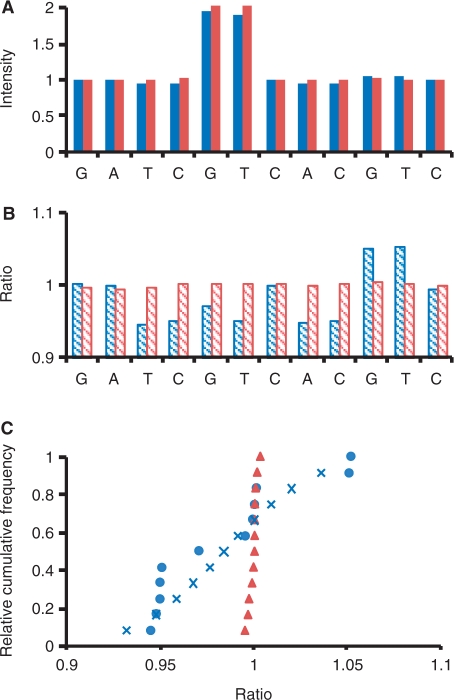

Because a ≈ qj, we used qj to construct another profile, T:

The obtained Tblue is shown in Figure 4A. T is basically proportional to M, and could be used to infer it. However, it is inappropriate to read the sequence of the mutant allele directly from profile T, because its values are highly influenced by the coefficient of variation. Since profiles W and M could be perfectly aligned by adding gaps to W (Figure 2A and B), we used T to replace the unknown profile M, and used dynamic programming to align W and T (Figure 4). The obtained alignment was thus used to speculate the sequence of the mutant allele.

Figure 4.

The alignment between (A) the profile Tblue, which is basically proportional to the unknown profile M, and (B) the profile W. See the main text for the details.

Before we perform the dynamic programming, it is worth to emphasize the ad hoc nature of PyrosequencingTM:

We can only add gaps to profile W, because the dispensing order was designated to complement the wild-type DNA fragment.

The implied sequence of the mutant allele is the set of nucleotides in T that are aligned to nucleotides in W (skipping nucleotides in T that are aligned to the added gaps). In our example, the implied sequence is GAGCGGTTC according to the alignment result in Figure 4.

When one gap is added to W, the corresponding nucleotide in T is suggested to be the added dNTP during PyrosequencingTM that is noncomplementary to the mutant allele. The extension was therefore paused at that time. In our example (Figure 4), the third and fourth nucleotides in T (thymine and cytosine) are aligned to the gap in W. This alignment implies that both thymine and cytosine are not complementary to the third nucleotide of the mutant allele.

When the gap added to W is elongated, the set of the corresponding nucleotides in T cannot include all the four dNTPs. Otherwise, all the four dNTPs are suggested to be noncomplementary to the next base of the mutant allele. In our example (Figure 4), for the first gap in W, only two dNTPs, thymine and cytosine, are included in the set of the corresponding nucleotides in T.

When the extension is reinitiated, the added dNTP (the nucleotide in T that is aligned to the current nucleotide in W) should be complementary, and therefore cannot be one of these noncomplementary dNTPs that have appeared in the positions of T that correspond to the adjacent prior gap of W. In our example (Figure 4), when the extension is reinitiated following the first gap in W, the added complementary dNTP is guanine. This dNTP cannot be thymine or cytosine.

For the two sites flanking the gap, the corresponding nucleotides in T cannot be the same, because the second added dNTP should be noncomplementary to the first nucleotide. In our example (Figure 4), for the two sites flanking the first gap in W, the corresponding nucleotides in T are adenine and guanine.

It should be noted that the dynamic programming is performed when the normality of profile R has been rejected, which implies possible nonsynchronistic extensions. The nonsynchronistic extensions could result from either substitutions or insertions in the mutant allele. On the other hand, mutations are rare. We do not expect that a mutant allele with more than one de novo SNP in the short fragment would frequently be discovered. Therefore, the scoring scheme for the dynamic programming used in this study is defined as follows:

The match score:

;

;  and

and  are used to even the values of the two profiles.

are used to even the values of the two profiles.The mismatch score: −∞

The gap penalty for profile W:

The gap penalty for profile T: −∞

One mismatch site with score

or one gap inserted to profile W with penalty 0 is allowed.

or one gap inserted to profile W with penalty 0 is allowed.

The estimated proportion of the wild-type allele in the pooled DNA sample

In the previous example, we assumed that the DNA quantity used for the pyrograms, W and S, are the same. However, this may not always hold. We therefore introduced another parameter, c, to represent the DNA quantity ratio:

Similar to previous sections, we speculated that  . We could also obtain two equations:

. We could also obtain two equations:

|

Although  is unknown, we could use the alignment result to infer it. Assume that there are x elements in the pyrogram W, and y of them are aligned to profile T, which suggests that there are (x – y) gap sites in the alignment. We could speculate that

is unknown, we could use the alignment result to infer it. Assume that there are x elements in the pyrogram W, and y of them are aligned to profile T, which suggests that there are (x – y) gap sites in the alignment. We could speculate that  . Therefore, the proportion of the wild-type allele in the pooled DNA sample was estimated as

. Therefore, the proportion of the wild-type allele in the pooled DNA sample was estimated as

|

Considering that in some cases the predicted mutant alleles may be derived from insertions, for example, an insertion at site z, we modified the equation as the following for these alleles:

|

The position of the mutation site

It should be noted that the value of i, which maximizes ei – qi, depends on the position of the mutant site. When the mutant site is located close to the end of the pyrogram, the value of i (and the proportion of i to x) would be small. In this circumstance, the normality of profile R may not be rejected because the signals of nonsynchronistic extensions are likely to be diluted. To overcome this problem, we tested the normality in a sliding window. The window size was designated as 30 in our study. As the window slides, if the normality is rejected for a certain window, we would use this window and its downstream pyrogram to derive the profile Q, and variables i, j and qj.

Performance testing by computational simulation

We utilized simulation tests to evaluate the performance of our algorithm. The tested DNA fragments are listed below:

ACACCAAGTCGTGTTCACAGTGGCTAAGTTCCGCCAGCCTCAC—the wild-type allele;

ACGCCAAGTCGTGTTCACAGTGGCTAAGTTCCGCCAGCCTCAC—the mutant allele with an adenosine-to-guanine substitution at the third nucleotide;

ACAGCCAAGTCGTGTTCACAGTGGCTAAGTTCCGCCAGCCTCAC—the mutant allele with a guanine inserted between the third and fourth nucleotides;

ACACCAAGTCGTGTTCACAGTGGCTAAGTTCCGCCATCCTCAC—the mutant allele with a guanine-to-thymine substitution at the 37th nucleotide; and

ACACCAAGTCGTGTTCACAGTGGCTAAGTTCCGCCAGCCACAC—the mutant allele with a thymine-to-adenosine substitution at the 40th nucleotide.

The PyrosequencingTM dispensing order of dNTPs, ACACAGTCGTGTCACAGTGCTAGTCGCAGCTCAC, was designated to complement the wild-type allele. The tested DNA pools contained 0%, 1%, 2%, 4%, 8%, 16%, 32% or 64% mutant allele. The pyrograms of these pooled DNA samples were simulated with different degrees of experimental precision (CV = 0.01%, 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.08%, 0.16%, 0.32%, 0.64%, 1.28%, 2.56%, 5.12%, 10.24% and 20.48%). When the normality of profile R was rejected (P < 0.01, Shapiro–Wilk test), dynamic programming was performed to speculate the sequence of the mutant allele; otherwise, no mutant allele was inferred. If the speculated sequence of the mutant allele was identical to the wild-type (except for the last couple nucleotides, which may not be well aligned when CV is high), no mutant allele was inferred, either. The simulation tests were repeated 10 000 times. If our method positively identified a mutant allele, we estimated the proportion of the wild-type allele in the DNA pool, despite whether the speculated sequence is correct or not. The mean and standard deviation of the estimated proportion of the wild-type allele in the DNA pool were thus calculated.

Performance testing by real PyrosequencingTM

We first used a real PyrosequencingTM assay as an example. The DNA samples were obtained from mitochondrial cytochrome b gene of Pseudorasbora parva specimens. The test region was amplified using a specific primer pair: forward – GTGTGAAGTTGTCGGGGTCT; reverse – CCGCAACGGTTATCCATCTT. The Biotin tag was attached on the reverse primer. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted using Taq DNA polymerase (Biokit Biotechnology, Taiwan) in a reaction mixture containing 25 ng of DNA template, 100 nM of biotin-labeled reverse primer and 100 nM of the forward primer. The PCR cycling program consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 20 s, annealing at 60°C for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 15 s; and the final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were purified with PCR clean-up kit (Biokit Biotechnology). The pooled DNA sample contained 90% PCR products of one allele (CCTAACAGGTTAGGGGAAAATAGCGCTAGAGATGTAAGGGCCAACAATATTAATACAAAGCCAAGAAGGTCTTTGT for the first 76 bases) as the wild-type and 10% PCR products of another allele with a cytosine-to-thymine substitution at the 6th nucleotide (CCTAATAGGTTAGGGGAAAATAGCGCT for the first 27 bases) as the mutant allele. The concentrations of the DNA samples were measured using ND-1000 (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) at OD260. Biotinylated single-stranded DNA in 40 µl PCR solution containing 600 ng pooled DNA samples and the forward primer were used for the PyrosequencingTM reaction, which was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (www.pyrosequencing.com) using Pyro Gold SQA Reagents (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) by model PyroMark ID (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

To reveal how practical our method is in real experiments, another large-scale PyrosequencingTM assay was conducted. A partial region of YBR114W gene was amplified for both the two yeast strains, BY4741 (BY, a laboratory strain) and RM11-1a (RM, a wild strain) with a specific primer pair: forward – AAGCAAAGTATTGTTAGCCGTCTA; reverse – ATCCAGCTCTTTTCAATCTCC. The Biotin tag was also attached on the reverse primer. Another forward sequencing primer, GCCGTCTAAACATGAGT, was used for the PyrosequencingTM reaction. The sequences to be read in the PyrosequencingTM reactions for BY and RM are GGCAAGTGGCAATCATCAACGAAAATCGAAGCACT and GGTAAGTGGCAATCATCAACGAAAATCGAAGCACT, respectively. A cytosine-to-thymine substitution is at the third nucleotide. We prepared the wild-type sample using 100% RM and the unknown pooled DNA sample using 90% RM + 10% BY. Both samples were repeated 12 times. One hundred and forty-four sample pairs could therefore be obtained. The derived pyrograms are represented in Supplementary Data.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The simulation results are listed in Tables 1 and 2. When the variation in the pyrogram signals was limited (the level of precision was high), e.g. CV < 0.1%, in most cases, our method could perfectly predict the DNA sequence of the mutant allele, either a substitution or an insertion, and its proportion in the DNA pools. However, when the signal variation was high (the level of precision was low), the prediction power of our method decreased with the proportion of the mutant allele in the DNA pool. For example, in Table 1, when CV = 2.56%, we precisely estimated the proportion of the mutant allele (with one substitution at the third nucleotide) in the DNA pool while its real proportion is 16% (estimated as 16.00 ± 2.87%); however, when the real proportion decreased to 1%, our method tended to overestimate its value (3.32 ± 2.69%). Similarly, in Table 2, when CV = 2.56%, we accurately predicted the sequence of the mutant allele (with one substitution at the third nucleotide) in all the 10 000 repeats while its proportion in the DNA pool is 32%; however, when the real proportion decreased to 1%, we only identified a mutant allele 507 times from the 10 000 repeats, and only nine of them had their sequence accurately predicted. Note that the standard deviation of the estimated allele frequencies also increased with CV (Table 1). These results suggested that the performance of our method is highly correlated to the variation in the pyrogram signals (the level of experimental precision) and the proportion of the mutant allele in the DNA pool. We also examined the possibility that we inaccurately predicted the existence of a mutant allele in a DNA pool consisting of 100% wild-type allele. The false positive ratio was <5% when CV < 5% (Table 2). Moreover, even in these cases, the estimated proportion of the wild-type allele in the DNA pool did not deviate from 100% too much when the signal variation was limited (Table 1).

Table 1.

The estimated proportion of the wild-type allele in the DNA pool under various simulated conditions

| CV | The mean ± standard deviation of the estimated proportion of the wild-type allele in the DNA pool |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a = 1.00 | a = 0.99 | a = 0.98 | a = 0.96 | a = 0.92 | a = 0.84 | a = 0.68 | a = 0.36 | |

| Mutant allele with an adenosine-to-guanine substitution at the third nucleotide | ||||||||

| 0.01% | 0.9999 ± 0.0001 | 0.9900 ± 0.0001 | 0.9800 ± 0.0001 | 0.9600 ± 0.0001 | 0.9200 ± 0.0001 | 0.8400 ± 0.0001 | 0.6800 ± 0.0001 | 0.3600 ± 0.0001 |

| 0.02% | 0.9997 ± 0.0002 | 0.9900 ± 0.0003 | 0.9800 ± 0.0003 | 0.9600 ± 0.0003 | 0.9200 ± 0.0002 | 0.8400 ± 0.0002 | 0.6800 ± 0.0002 | 0.3600 ± 0.0001 |

| 0.04% | 0.9994 ± 0.0004 | 0.9900 ± 0.0006 | 0.9800 ± 0.0006 | 0.9600 ± 0.0005 | 0.9200 ± 0.0005 | 0.8400 ± 0.0004 | 0.6800 ± 0.0003 | 0.3600 ± 0.0002 |

| 0.08% | 0.9988 ± 0.0009 | 0.9900 ± 0.0011 | 0.9800 ± 0.0011 | 0.9600 ± 0.0011 | 0.9200 ± 0.0010 | 0.8400 ± 0.0009 | 0.6800 ± 0.0007 | 0.3600 ± 0.0004 |

| 0.16% | 0.9977 ± 0.0018 | 0.9899 ± 0.0024 | 0.9800 ± 0.0022 | 0.9600 ± 0.0021 | 0.9200 ± 0.0020 | 0.8400 ± 0.0018 | 0.6800 ± 0.0013 | 0.3600 ± 0.0008 |

| 0.32% | 0.9954 ± 0.0036 | 0.9898 ± 0.0059 | 0.9798 ± 0.0049 | 0.9599 ± 0.0042 | 0.9200 ± 0.0040 | 0.8400 ± 0.0035 | 0.6800 ± 0.0026 | 0.3600 ± 0.0017 |

| 0.64% | 0.9910 ± 0.0070 | 0.9881 ± 0.0086 | 0.9796 ± 0.0117 | 0.9598 ± 0.0092 | 0.9199 ± 0.0079 | 0.8399 ± 0.0069 | 0.6799 ± 0.0052 | 0.3600 ± 0.0033 |

| 1.28% | 0.9822 ± 0.0138 | 0.9830 ± 0.0142 | 0.9763 ± 0.0170 | 0.9593 ± 0.0229 | 0.9196 ± 0.0167 | 0.8401 ± 0.0138 | 0.6799 ± 0.0105 | 0.3599 ± 0.0066 |

| 2.56% | 0.9654 ± 0.0275 | 0.9668 ± 0.0269 | 0.9652 ± 0.0283 | 0.9541 ± 0.0340 | 0.9206 ± 0.0449 | 0.8400 ± 0.0287 | 0.6802 ± 0.0213 | 0.3599 ± 0.0132 |

| 5.12% | 0.9352 ± 0.0546 | 0.9336 ± 0.0528 | 0.9363 ± 0.0532 | 0.9335 ± 0.0565 | 0.9111 ± 0.0675 | 0.8437 ± 0.0837 | 0.6801 ± 0.0457 | 0.3597 ± 0.0267 |

| 10.24% | 0.8807 ± 0.1069 | 0.8871 ± 0.1073 | 0.8862 ± 0.1071 | 0.8848 ± 0.1076 | 0.8784 ± 0.1126 | 0.8395 ± 0.1387 | 0.6919 ± 0.1505 | 0.3603 ± 0.0526 |

| 20.48% | 0.8315 ± 0.2466 | 0.8314 ± 0.2546 | 0.8280 ± 0.2627 | 0.8282 ± 0.2467 | 0.8283 ± 0.2743 | 0.8130 ± 0.2543 | 0.7490 ± 0.3271 | 0.3464 ± 4.3826 |

| Mutant allele with a guanine inserted between the third and fourth nucleotides | ||||||||

| 0.01% | 0.9999 ± 0.0001 | 0.9900 ± 0.0001 | 0.9800 ± 0.0001 | 0.9600 ± 0.0001 | 0.9200 ± 0.0001 | 0.8400 ± 0.0001 | 0.6800 ± 0.0001 | 0.3600 ± 0.0001 |

| 0.02% | 0.9998 ± 0.0002 | 0.9900 ± 0.0003 | 0.9800 ± 0.0003 | 0.9600 ± 0.0003 | 0.9200 ± 0.0002 | 0.8400 ± 0.0002 | 0.6800 ± 0.0002 | 0.3600 ± 0.0001 |

| 0.04% | 0.9997 ± 0.0005 | 0.9900 ± 0.0005 | 0.9800 ± 0.0005 | 0.9600 ± 0.0005 | 0.9200 ± 0.0005 | 0.8400 ± 0.0004 | 0.6800 ± 0.0003 | 0.3600 ± 0.0002 |

| 0.08% | 0.9994 ± 0.0010 | 0.9900 ± 0.0011 | 0.9800 ± 0.0010 | 0.9600 ± 0.0010 | 0.9200 ± 0.0010 | 0.8400 ± 0.0008 | 0.6800 ± 0.0006 | 0.3600 ± 0.0004 |

| 0.16% | 0.9986 ± 0.0019 | 0.9899 ± 0.0023 | 0.9801 ± 0.0021 | 0.9600 ± 0.0020 | 0.9200 ± 0.0019 | 0.8400 ± 0.0017 | 0.6800 ± 0.0013 | 0.3600 ± 0.0008 |

| 0.32% | 0.9974 ± 0.0037 | 0.9903 ± 0.0059 | 0.9798 ± 0.0044 | 0.9601 ± 0.0041 | 0.9200 ± 0.0038 | 0.8399 ± 0.0034 | 0.6800 ± 0.0026 | 0.3600 ± 0.0016 |

| 0.64% | 0.9947 ± 0.0075 | 0.9888 ± 0.0089 | 0.9811 ± 0.0115 | 0.9597 ± 0.0093 | 0.9199 ± 0.0076 | 0.8399 ± 0.0067 | 0.6800 ± 0.0051 | 0.3600 ± 0.0032 |

| 1.28% | 0.9892 ± 0.0157 | 0.9867 ± 0.0159 | 0.9789 ± 0.0176 | 0.9615 ± 0.0220 | 0.9195 ± 0.0169 | 0.8400 ± 0.0134 | 0.6799 ± 0.0102 | 0.3600 ± 0.0063 |

| 2.56% | 0.9808 ± 0.0296 | 0.9756 ± 0.0289 | 0.9697 ± 0.0284 | 0.9580 ± 0.0342 | 0.9251 ± 0.0453 | 0.8393 ± 0.0291 | 0.6797 ± 0.0205 | 0.3601 ± 0.0128 |

| 5.12% | 0.9502 ± 0.0547 | 0.9538 ± 0.0560 | 0.9508 ± 0.0544 | 0.9413 ± 0.0606 | 0.9254 ± 0.0773 | 0.8492 ± 0.0863 | 0.6801 ± 0.0477 | 0.3599 ± 0.0257 |

| 10.24% | 0.9170 ± 0.1206 | 0.9188 ± 0.1193 | 0.9223 ± 0.1269 | 0.9144 ± 0.1222 | 0.9006 ± 0.1369 | 0.8573 ± 0.1565 | 0.7043 ± 0.1812 | 0.3556 ± 0.5902 |

| 20.48% | 0.8898 ± 0.3129 | 0.8969 ± 0.3699 | 0.9005 ± 0.5321 | 0.8804 ± 0.3253 | 0.8773 ± 0.3134 | 0.8779 ± 0.5953 | 0.7953 ± 1.6143 | 0.3580 ± 3.9309 |

| Mutant allele with a guanine-to-thymine substitution at the 37th nucleotide | ||||||||

| 0.01% | 0.9999 ± 0.0001 | 0.9900 ± 0.0001 | 0.9800 ± 0.0001 | 0.9600 ± 0.0001 | 0.9200 ± 0.0001 | 0.8400 ± 0.0001 | 0.6800 ± 0.0001 | 0.3600 ± 0.0000 |

| 0.02% | 0.9998 ± 0.0002 | 0.9900 ± 0.0002 | 0.9800 ± 0.0002 | 0.9600 ± 0.0002 | 0.9200 ± 0.0002 | 0.8400 ± 0.0002 | 0.6800 ± 0.0001 | 0.3600 ± 0.0001 |

| 0.04% | 0.9997 ± 0.0005 | 0.9900 ± 0.0004 | 0.9800 ± 0.0004 | 0.9600 ± 0.0003 | 0.9200 ± 0.0003 | 0.8400 ± 0.0003 | 0.6800 ± 0.0003 | 0.3600 ± 0.0002 |

| 0.08% | 0.9993 ± 0.0009 | 0.9900 ± 0.0007 | 0.9800 ± 0.0007 | 0.9600 ± 0.0007 | 0.9200 ± 0.0007 | 0.8400 ± 0.0006 | 0.6800 ± 0.0005 | 0.3600 ± 0.0004 |

| 0.16% | 0.9985 ± 0.0018 | 0.9900 ± 0.0015 | 0.9800 ± 0.0015 | 0.9600 ± 0.0014 | 0.9200 ± 0.0014 | 0.8400 ± 0.0012 | 0.6800 ± 0.0010 | 0.3600 ± 0.0008 |

| 0.32% | 0.9975 ± 0.0037 | 0.9900 ± 0.0047 | 0.9800 ± 0.0031 | 0.9601 ± 0.0028 | 0.9200 ± 0.0027 | 0.8400 ± 0.0024 | 0.6800 ± 0.0020 | 0.3600 ± 0.0016 |

| 0.64% | 0.9948 ± 0.0076 | 0.9916 ± 0.0085 | 0.9803 ± 0.0096 | 0.9598 ± 0.0058 | 0.9201 ± 0.0054 | 0.8400 ± 0.0049 | 0.6801 ± 0.0041 | 0.3600 ± 0.0032 |

| 1.28% | 0.9885 ± 0.0144 | 0.9881 ± 0.0146 | 0.9853 ± 0.0170 | 0.9595 ± 0.0172 | 0.9198 ± 0.0111 | 0.8401 ± 0.0098 | 0.6799 ± 0.0083 | 0.3600 ± 0.0065 |

| 2.56% | 0.9774 ± 0.0296 | 0.9774 ± 0.0276 | 0.9741 ± 0.0277 | 0.9700 ± 0.0342 | 0.9173 ± 0.0304 | 0.8395 ± 0.0198 | 0.6799 ± 0.0164 | 0.3601 ± 0.0129 |

| 5.12% | 0.9531 ± 0.0535 | 0.9590 ± 0.0577 | 0.9552 ± 0.0542 | 0.9533 ± 0.0567 | 0.9367 ± 0.0640 | 0.8463 ± 0.0670 | 0.6798 ± 0.0329 | 0.3600 ± 0.0255 |

| 10.24% | 0.9108 ± 0.1205 | 0.9112 ± 0.1175 | 0.9142 ± 0.1161 | 0.9162 ± 0.1199 | 0.9059 ± 0.1164 | 0.8901 ± 0.1305 | 0.6954 ± 0.1258 | 0.3595 ± 0.0516 |

| 20.48% | 0.8806 ± 0.3044 | 0.8952 ± 0.3788 | 0.8890 ± 0.3120 | 0.8957 ± 0.3257 | 0.8863 ± 0.3063 | 0.8816 ± 0.3128 | 0.8718 ± 0.3127 | 0.5032 ± 0.4090 |

| Mutant allele with a thymine-to-adenosine substitution at the 40th nucleotide | ||||||||

| 0.01% | 0.9999 ± 0.0001 | 1.0008 ± 0.0003 | 1.0015 ± 0.0005 | 1.0031 ± 0.0011 | 1.0061 ± 0.0021 | 1.0124 ± 0.0043 | 1.0250 ± 0.0088 | 1.0518 ± 0.0187 |

| 0.02% | 0.9998 ± 0.0002 | 1.0008 ± 0.0003 | 1.0015 ± 0.0006 | 1.0030 ± 0.0011 | 1.0061 ± 0.0021 | 1.0123 ± 0.0043 | 1.0248 ± 0.0088 | 1.0511 ± 0.0185 |

| 0.04% | 0.9997 ± 0.0005 | 1.0008 ± 0.0006 | 1.0015 ± 0.0007 | 1.0031 ± 0.0012 | 1.0061 ± 0.0022 | 1.0124 ± 0.0044 | 1.0250 ± 0.0088 | 1.0515 ± 0.0186 |

| 0.08% | 0.9992 ± 0.0009 | 1.0011 ± 0.0013 | 1.0016 ± 0.0012 | 1.0031 ± 0.0014 | 1.0061 ± 0.0023 | 1.0124 ± 0.0044 | 1.0251 ± 0.0089 | 1.0515 ± 0.0187 |

| 0.16% | 0.9985 ± 0.0018 | 1.0003 ± 0.0035 | 1.0022 ± 0.0025 | 1.0033 ± 0.0025 | 1.0062 ± 0.0027 | 1.0124 ± 0.0047 | 1.0252 ± 0.0091 | 1.0516 ± 0.0188 |

| 0.32% | 0.9974 ± 0.0038 | 0.9974 ± 0.0061 | 1.0004 ± 0.0070 | 1.0044 ± 0.0051 | 1.0066 ± 0.0047 | 1.0124 ± 0.0055 | 1.0250 ± 0.0095 | 1.0517 ± 0.0191 |

| 0.64% | 0.9947 ± 0.0073 | 0.9939 ± 0.0090 | 0.9948 ± 0.0124 | 1.0010 ± 0.0139 | 1.0089 ± 0.0098 | 1.0132 ± 0.0093 | 1.0249 ± 0.0109 | 1.0513 ± 0.0201 |

| 1.28% | 0.9881 ± 0.0141 | 0.9873 ± 0.0154 | 0.9869 ± 0.0187 | 0.9908 ± 0.0246 | 1.0037 ± 0.0269 | 1.0178 ± 0.0199 | 1.0263 ± 0.0177 | 1.0517 ± 0.0233 |

| 2.56% | 0.9757 ± 0.0298 | 0.9751 ± 0.0299 | 0.9751 ± 0.0285 | 0.9710 ± 0.0331 | 0.9808 ± 0.0487 | 1.0100 ± 0.0497 | 1.0358 ± 0.0380 | 1.0547 ± 0.0376 |

| 5.12% | 0.9578 ± 0.0584 | 0.9507 ± 0.0559 | 0.9510 ± 0.0544 | 0.9506 ± 0.0580 | 0.9489 ± 0.0625 | 0.9658 ± 0.0896 | 1.0293 ± 0.0910 | 1.0742 ± 0.0820 |

| 10.24% | 0.9179 ± 0.1261 | 0.9043 ± 0.1042 | 0.9236 ± 0.1298 | 0.9050 ± 0.1095 | 0.9180 ± 0.1220 | 0.9013 ± 0.1217 | 0.9420 ± 0.1700 | 1.0736 ± 0.1752 |

| 20.48% | 0.8923 ± 0.3268 | 0.8918 ± 0.3525 | 0.8920 ± 0.3403 | 0.8880 ± 0.3378 | 0.8931 ± 0.3038 | 0.8825 ± 0.2935 | 0.8715 ± 0.2986 | 0.9362 ± 0.3909 |

a indicates the real proportion of the wild-type allele in the DNA pool.

Table 2.

The accuracy of the mutant allele identification in the DNA pool under various simulated conditions

| CV | True positive/positive |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a = 1.00 | a = 0.99 | a = 0.98 | a = 0.96 | a = 0.92 | a = 0.84 | a = 0.68 | a = 0.36 | |

| Mutant allele with an adenosine-to-guanine substitution at the third nucleotide | ||||||||

| 0.01% | – / 387 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.02% | – / 370 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.04% | – / 380 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.08% | – / 401 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.16% | – / 371 | 9242 / 9504 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.32% | – / 363 | 1932 / 3057 | 9304 / 9568 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.64% | – / 363 | 209 / 1006 | 1978 / 3087 | 9436 / 9676 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 1.28% | – / 401 | 31 / 609 | 234 / 1084 | 2224 / 3311 | 9616 / 9801 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 2.56% | – / 445 | 9 / 507 | 38 / 718 | 285 / 1236 | 2742 / 3922 | 9818 / 9939 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 5.12% | – / 541 | 5 / 634 | 11 / 690 | 67 / 995 | 452 / 1697 | 3801 / 5166 | 9932 / 9997 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 10.24% | – / 1099 | 3 / 1158 | 10 / 1205 | 35 / 1391 | 117 / 1758 | 820 / 2856 | 6132 / 7503 | 9969 / 10 000 |

| 20.48% | – / 3287 | 15 / 3303 | 27 / 3400 | 45 / 3565 | 95 / 3909 | 361 / 4430 | 2058 / 5874 | 8086 / 9374 |

| Mutant allele with a guanine inserted between the third and fourth nucleotides | ||||||||

| 0.01% | – / 366 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.02% | – / 368 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.04% | – / 354 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.08% | – / 378 | 9995 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.16% | – / 366 | 8604 / 8882 | 9998 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10000 / 10 000 |

| 0.32% | – / 381 | 1351 / 2389 | 8667 / 8936 | 9994 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.64% | – / 384 | 166 / 946 | 1425 / 2385 | 8894 / 9138 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 1.28% | – / 358 | 19 / 604 | 181 / 1042 | 1571 / 2610 | 9184 / 9396 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 2.56% | – / 424 | 6 / 547 | 21 / 698 | 219 / 1188 | 1971 / 3104 | 9600 / 9793 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 5.12% | – / 573 | 0 / 663 | 7 / 699 | 31 / 903 | 260 / 1499 | 2829 / 4125 | 9856 / 9987 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 10.24% | – / 1032 | 1 / 1079 | 3 / 1221 | 15 / 1389 | 79 / 1795 | 621 / 2765 | 5134 / 6494 | 9934 / 10 000 |

| 20.48% | – / 3231 | 4 / 3288 | 6 / 3432 | 16 / 3553 | 32 / 3875 | 208 / 4513 | 1613 / 5737 | 7559 / 8853 |

| Mutant allele with a guanine-to-thymine substitution at the 37th nucleotide | ||||||||

| 0.01% | – / 402 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.02% | – / 382 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.04% | – / 394 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.08% | – / 393 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.16% | – / 385 | 8867 / 8944 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.32% | – / 427 | 918 / 1152 | 9005 / 9060 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 0.64% | – / 392 | 77 / 386 | 855 / 1091 | 9050 / 9107 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 1.28% | – / 394 | 24 / 397 | 76 / 401 | 869 / 1056 | 9220 / 9256 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 2.56% | – / 452 | 3 / 443 | 13 / 429 | 60 / 385 | 868 / 1026 | 9480 / 9497 | 10 000 / 10 000 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 5.12% | – / 552 | 3 / 529 | 3 / 576 | 17 / 521 | 99 / 504 | 947 / 1112 | 9767 / 9775 | 10 000 / 10 000 |

| 10.24% | – / 1048 | 2 / 1058 | 5 / 1054 | 11 / 1052 | 43 / 1111 | 160 / 963 | 1145 / 1332 | 9820 / 9824 |

| 20.48% | – / 3227 | 8 / 3282 | 9 / 3461 | 10 / 3260 | 31 / 3439 | 99 / 3428 | 480 / 3043 | 1901 / 2481 |

| Mutant allele with a thymine-to-adenosine substitution at the 40th nucleotide | ||||||||

| 0.01% | – / 367 | 111 / 10 000 | 111 / 10 000 | 95 / 10 000 | 82 / 10 000 | 96 / 10 000 | 116 / 10 000 | 97 / 10 000 |

| 0.02% | – / 372 | 100 / 10 000 | 112 / 10 000 | 99 / 10 000 | 98 / 10 000 | 96 / 10 000 | 126 / 10 000 | 122 / 10 000 |

| 0.04% | – / 379 | 110 / 10 000 | 109 / 10 000 | 118 / 10 000 | 100 / 10 000 | 117 / 10 000 | 91 / 10 000 | 110 / 10 000 |

| 0.08% | – / 384 | 115 / 10 000 | 121 / 10 000 | 123 / 10 000 | 99 / 10 000 | 109 / 10 000 | 92 / 10 000 | 118 / 10 000 |

| 0.16% | – / 379 | 934 / 7882 | 126 / 10 000 | 111 / 10 000 | 120 / 10 000 | 112 / 10 000 | 114 / 10 000 | 103 / 10 000 |

| 0.32% | – / 358 | 386 / 1438 | 921 / 7837 | 100 / 10 000 | 105 / 10 000 | 117 / 10 000 | 88 / 10 000 | 111 / 10 000 |

| 0.64% | – / 382 | 99 / 566 | 423 / 1465 | 929 / 7948 | 106 / 10 000 | 120 / 10 000 | 110 / 10 000 | 117 / 10 000 |

| 1.28% | – / 401 | 37 / 418 | 105 / 541 | 373 / 1460 | 806 / 8201 | 96 / 10 000 | 99 / 10 000 | 104 / 10 000 |

| 2.56% | – / 403 | 21 / 468 | 50 / 484 | 109 / 566 | 421 / 1523 | 663 / 8525 | 105 / 10 000 | 87 / 10 000 |

| 5.12% | – / 566 | 29 / 572 | 35 / 564 | 43 / 559 | 122 / 677 | 400 / 1592 | 479 / 9017 | 121 / 10 000 |

| 10.24% | – / 1083 | 30 / 1100 | 40 / 1063 | 58 / 1109 | 81 / 1092 | 184 / 1182 | 424 / 2003 | 253 / 9156 |

| 20.48% | – / 3238 | 62 / 3344 | 64 / 3271 | 86 / 3374 | 102 / 3374 | 183 / 3520 | 403 / 3644 | 550 / 4127 |

Positive: the total number of simulation repeats that positively identified a mutant allele in the DNA pool.

True positive: the number of simulation repeats that correctly identified the mutant allele.

a indicates the real proportion of the wild-type allele in the DNA pool.

Since sufficient signals of nonsynchronistic extensions are crucial for our algorithm, one might argue that it would be difficult to identify a mutant allele if its mutant site was located close to the end of the pyrogram. Our simulation revealed that, when the substitution was located at the 40th nucleotide, our algorithm almost did not have the identification power (Tables 1 and 2) because the generated profile R had only two sites with  . In this circumstance, it was difficult to obtain a reasonable i, and also the variables j, and qj. We therefore were unable to correctly align the profiles and predict the mutant sequence. However, when the substitution was located at the 37th nucleotide instead (with four sites

. In this circumstance, it was difficult to obtain a reasonable i, and also the variables j, and qj. We therefore were unable to correctly align the profiles and predict the mutant sequence. However, when the substitution was located at the 37th nucleotide instead (with four sites  ), our algorithm performed almost the same as when the substitution was located at the third nucleotide (Tables 1 and 2). This result suggested that our method should have a wide application.

), our algorithm performed almost the same as when the substitution was located at the third nucleotide (Tables 1 and 2). This result suggested that our method should have a wide application.

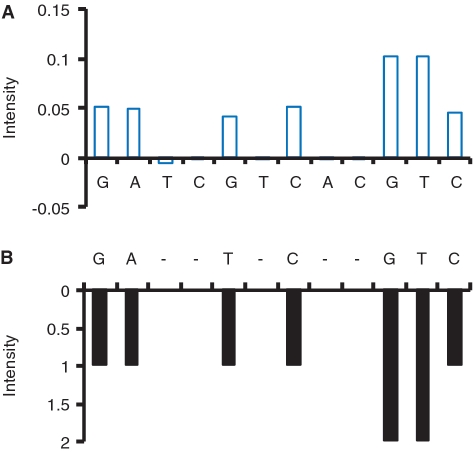

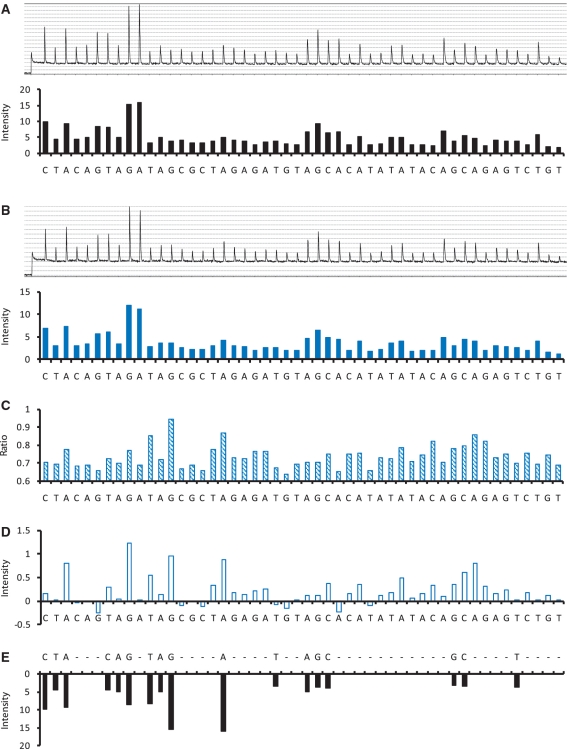

We also performed real PyrosequencingTM assays to reveal how our algorithm works. In our first example (Figure 5), the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene of P. parva was used. Figure 5A and B display the pyrograms for the wild-type DNA fragment and the pooled DNA sample containing 10% mutant allele, respectively. Although it might not be easy to distinguish these two pyrograms by eyes, our algorithm successfully identified the sequence of the mutant allele (Figure 5D and E), and estimated its proportion in the DNA pool as 12.0%. The deviation of this estimated value is likely due to the variation in the pyrogram signals. This variation could be revealed from the constructed profile T in Figure 5D. According to the PyrosequencingTM dispensing order of dNTPs and the sequence of the mutant allele, the 29th–39th and 42nd–45th sites were supposed to have no signal being detected; however, unexpected high values (due to the signal variation) were represented on some of these sites (Figure 5D). Our dynamic programming overcame this difficulty by considering the ad hoc nature of PyrosequencingTM. We were therefore able to correctly align the profiles T and W, and predicted the sequence of the mutant allele (Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5.

The real PyrosequencingTM examination of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene of P. parva: (A) the pyrogram of the wild-type DNA fragment, W; (B) the pyrogram of a pooled DNA sample containing 10% mutant DNA, S; (C) the profile R; (D) the profile T; (E) the profile W which is aligned to profile T. See the main text for the details.

Given that the performance of our algorithm heavily depends on the level of experimental precision as described above, it is worth to know the reproducibility of general PyrosequencingTM reactions. Previous studies indicated that, when the same PCR products were sequenced several times, the standard deviation of the signals ranged 0.006–0.024 (32) and 0.008–0.031 (15). Doostzadeh et al. (22) further suggested that it is possible to reduce the values of standard deviation to 0.0003–0.0018 if the signal intensity was appropriately measured. If the coefficient of variation was limited in this range, our method could easily be used to detect rare mutant alleles (Tables 1 and 2). It should be emphasized that the purpose of our study was not to improve the quality of PyrosequencingTM reactions and our experiments were not performed by experienced technicians. However, the result of our large-scale assay indicates that the proposed algorithm still performs well for such general PyrosequencingTM tests (Table 3). Among all the 144 sample pairs, only one pair failed to satisfy the criteria: Shapiro–Wilk test, P < 0.05. Moreover, we accurately predicted the sequence of BY strain (the unknown allele) for 141 of the rest 143 pairs. The proportion of BY strain in the pooled DNA sample was estimated as 12.82 ± 3.81%. We also tested the false-positive ratio using the 12 repeats with 100% RM as both wild-type sample and pooled DNA sample. In the possible 132 sample pairs, only three pairs were inaccurately predicted as with the existence of a mutant allele, i.e. W3/W6, W5/W8 and W6/W3 as the wild-type sample/the pooled sample, respectively. These examinations are consistent with our computational simulation results.

Table 3.

The estimated proportion of BY strain (the unknown allele) in the pooled DNA samples in our large-scale PyrosequencingTM assay

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | 0.0954 | 0.1851 | 0.0977 | 0.1434 | 0.0916 | 0.1443 | 0.0875 | 0.1662 | 0.1045 | 0.1387 | 0.1199 | 0.1587 |

| W2 | 0.1147 | 0.1387 | 0.1049 | 0.1380 | 0.1705 | 0.1417 | 0.1158 | 0.0755 | 0.1299 | 0.1026 | 0.1445 | 0.1651 |

| W3 | 0.1185 | 0.1469 | 0.1480 | 0.1312 | 0.0894 | 0.1361 | 0.1623 | 0.1638 | 0.1484 | 0.1349 | 0.1130 | 0.1665 |

| W4 | 0.1032 | 0.1774 | 0.1273 | 0.1281 | 0.1394 | 0.1655 | 0.1569 | 0.1593 | 0.1735 | 0.1668 | 0.1500 | 0.1456 |

| W5 | 0.1252 | 0.1979 | 0.1424 | 0.1154 | 0.1980 | 0.1651 | 0.1448 | 0.1583 | 0.1451 | 0.1165 | 0.1433 | 0.0787 |

| W6 | 0.0618 | 0.0412 | 0.0829 | 0.1335 | 0.1304 | 0.0330 | – | 0.2073 | 0.0708 | 0.2122* | 0.0909 | 0.1078 |

| W7 | 0.1084 | 0.1065 | 0.1460 | 0.1055 | 0.1099 | 0.1579 | 0.1553 | 0.1383 | 0.0756 | 0.1667 | 0.0901 | 0.1161 |

| W8 | 0.0702 | 0.1562 | 0.1979 | 0.1360 | 0.0464 | 0.1264 | 0.1452 | 0.0779 | 0.2001 | 0.1095 | 0.0779 | 0.1028 |

| W9 | 0.0704 | 0.0874 | 0.1002 | 0.1596 | 0.1459 | 0.1398 | −0.0616 | 0.1846 | 0.1994 | 0.1871 | 0.1551 | 0.0929 |

| W10 | 0.1262 | 0.1078 | 0.0904 | 0.1550 | 0.1237 | 0.1111 | 0.1274 | 0.0721 | 0.1249 | 0.1502* | 0.0993 | 0.1038 |

| W11 | 0.1183 | 0.1043 | 0.1240 | 0.1320 | 0.1162 | 0.1601 | 0.1049 | 0.1372 | 0.1226 | 0.1703 | 0.1256 | 0.1482 |

| W12 | 0.1136 | 0.1300 | 0.1408 | 0.1078 | 0.0983 | 0.1164 | 0.1195 | 0.1472 | 0.1366 | 0.1760 | 0.1414 | 0.1352 |

The 12 wild-type samples (100% RM) are denoted as W1–W12, while the 12 pooled DNA samples (90% RM + 10% BY) are denoted as S1–S12.

The sample pair failed to satisfy the criteria: Shapiro–Wilk test, P < 0.05, is marked with (–), and the two pairs we failed to identify the correct sequence of the unknown allele are marked with (*).

The deficiency of our algorithm is that it might fail if the pooled DNA sample contained more than one unexpected mutant allele (de novo SNP). Combining more than two pyrograms into one would make the derived pyrogram become too complicated to be decomposed. Fortunately, we could design a specific dispensing order of dNTPs for all the known haplotypes, and our method only has to deal with de novo SNPs. It is unlikely that we would frequently find two or more de novo SNPs in a short PyrosequencingTM read. The other difficulty is that one haplotype might include more than one mutant site. Modifying the scoring scheme of our dynamic programming (e.g. reducing the penalty for the second mismatch site) might help to identify some of these haplotypes. This is especially true if the mutant sites were located close to the start of the pyrogram, because sufficient signals of nonsynchronistic extensions could thus be provided to overcome the penalty of the mismatch sites. However, this kind of modifications would also increase the false-positive ratio and decrease the specificity of our prediction. Therefore, our method only focused on haplotypes with one mutant site, since mutations are supposed to be rare.

In recent years, PyrosequencingTM has been frequently utilized to estimate the frequencies or expression levels of known alleles (13–24,26). Because the dispensing order of dNTPs was designed based on the known SNPs, the de novo SNPs probably used to be ignored, especially if their frequencies were not high enough to generate obvious signals of asynchronistic extensions. For this kind of studies, our method could easily be applied to examine the existence of unexpected mutant alleles in the DNA samples by comparing the obtained pyrograms. This is a simple and economical strategy for SNP genotyping surveys. On the other hand, our algorithm also has the potential to be applied for the high-throughput PyrosequencingTM (454 platform) data. An appropriate DNA-to-bead ratio is essential for the 454 platform because only beads carrying single type of amplified templates could generate readable signals (flowgrams) (33–35). The mixed signals generated from either wells each containing multiple beads or beads each carrying multiple amplified templates are usually filtered out. In some of these cases, asynchronistic extensions may occur and our algorithm could be modified to identify these mixed DNA templates. More information could therefore be obtained. In other words, the method proposed in this study not only creates a new application for the low-throughput PyrosequencingTM platform, but also provides a possible strategy to improve the high-throughput PyrosequencingTM platform that might be useful in the future.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 97-2621-B-009-001 and 98-2621-B-009-001-MY3); NCTU under the grant from MoE ATU Plan. Funding for open access charge: National Science Council, Taiwan.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank C.-C. Chiou, J.-D. Luo, C.-H. Chang and H.-M. Sung for the assistance of PyrosequencingTM experiments, and M.-S. Shiao and J. Rest for suggestions and help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller RD, Phillips MS, Jo I, Donaldson MA, Studebaker JF, Addleman N, Alfisi SV, Ankener WM, Bhatti HA, Callahan CE, et al. High-density single-nucleotide polymorphism maps of the human genome. Genomics. 2005;86:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Stuve LL, Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Boudreau A, Hardenbol P, Leal SM, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarz G, Baumler S, Block A, Felsenstein FG, Wenzel G. Determination of detection and quantification limits for SNP allele frequency estimation in DNA pools using real time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sham P, Bader JS, Craig I, O'Donovan M, Owen M. DNA Pooling: a tool for large-scale association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:862–871. doi: 10.1038/nrg930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risch N, Teng J. The relative power of family-based and case-control designs for linkage disequilibrium studies of complex human diseases I. DNA pooling. Genome Res. 1998;8:1273–1288. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.12.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng J, Risch N. The relative power of family-based and case-control designs for linkage disequilibrium studies of complex human diseases. II. Individual genotyping. Genome Res. 1999;9:234–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher LM, Meaburn E, Knight J, Sham PC, Schalkwyk LC, Craig IW, Plomin R. SNPs, microarrays and pooled DNA: identification of four loci associated with mild mental impairment in a sample of 6000 children. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:1315–1325. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Tassell CP, Smith TP, Matukumalli LK, Taylor JF, Schnabel RD, Lawley CT, Haudenschild CD, Moore SS, Warren WC, Sonstegard TS. SNP discovery and allele frequency estimation by deep sequencing of reduced representation libraries. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:247–252. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyman ED. A new method of sequencing DNA. Anal. Biochem. 1988;174:423–436. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzker ML. Emerging technologies in DNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2005;15:1767–1776. doi: 10.1101/gr.3770505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronaghi M, Karamohamed S, Pettersson B, Uhlen M, Nyren P. Real-time DNA sequencing using detection of pyrophosphate release. Anal. Biochem. 1996;242:84–89. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronaghi M, Uhlen M, Nyren P. A sequencing method based on real-time pyrophosphate. Science. 1998;281:363, 365. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittkopp PJ, Haerum BK, Clark AG. Evolutionary changes in cis and trans gene regulation. Nature. 2004;430:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature02698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang Y-W, Liu F-GR, Yu N, Sung HM, Yang P, Wang D, Huang CJ, Shih MC, Li W-H. Roles of cis- and trans-changes in the regulatory evolution of genes in the gluconeogenic pathway in yeast. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:1863–1875. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, Yan L, Cantor M, Namgyal C, Mino-Kenudson M, Lauwers GY, Loda M, Fuchs CS. Sensitive sequencing method for KRAS mutation detection by Pyrosequencing. J. Mol. Diagn. 2005;7:413–421. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60571-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheesman S, Creasey A, Degnan K, Kooij T, Afonso A, Cravo P, Carter R, Hunt P. Validation of Pyrosequencing for accurate and high throughput estimation of allele frequencies in malaria parasites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007;152:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Lozupone C, Hamady M, Bushman FD, Knight R. Short pyrosequencing reads suffice for accurate microbial community analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasson J, Skolnick G, Love-Gregory L, Permutt MA. Assessing allele frequencies of single nucleotide polymorphisms in DNA pools by pyrosequencing technology. Biotechniques. 2002;32:1144–1152. doi: 10.2144/02325dd04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruber JD, Colligan PB, Wolford JK. Estimation of single nucleotide polymorphism allele frequency in DNA pools by using Pyrosequencing. Hum. Genet. 2002;110:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0722-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordfors L, Jansson M, Sandberg G, Lavebratt C, Sengul S, Schalling M, Arner P. Large-scale genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms by PyrosequencingTM and validation against the 5'nuclease (Taqman®) assay. Hum. Mutat. 2002;19:395–401. doi: 10.1002/humu.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andreasson H, Nilsson M, Budowle B, Frisk S, Allen M. Quantification of mtDNA mixtures in forensic evidence material using pyrosequencing. Int. J. Legal Med. 2006;120:383–390. doi: 10.1007/s00414-005-0072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doostzadeh J, Shokralla S, Absalan F, Jalili R, Mohandessi S, Langston JW, Davis RW, Ronaghi M, Gharizadeh B. High throughput automated allele frequency estimation by pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavebratt C, Sengul S, Jansson M, Schalling M. PyrosequencingTM-based SNP allele frequency estimation in DNA pools. Hum. Mutat. 2004;23:92–97. doi: 10.1002/humu.10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neve B, Froguel P, Corset L, Vaillant E, Vatin V, Boutin P. Rapid SNP allele frequency determination in genomic DNA pools by pyrosequencing. Biotechniques. 2002;32:1138–1142. doi: 10.2144/02325dd03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mardis ER. The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics. Trends Genet. 2008;24:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrosino JF, Highlander S, Luna RA, Gibbs RA, Versalovic J. Metagenomic pyrosequencing and microbial identification. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:856–866. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.107565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langaee T, Ronaghi M. Genetic variation analyses by Pyrosequencing. Mutat. Res. 2005;573:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pourmand N, Elahi E, Davis RW, Ronaghi M. Multiplex pyrosequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e31. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugozzoli LA. Multiplex assays with fluorescent microbead readout: a powerful tool for mutation detection. Clin. Chem. 2004;50:1963–1965. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.039784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou G-H, Gotou M, Kajiyama T, Kambara H. Multiplex SNP typing by bioluminometric assay coupled with terminator incorporation (BATI) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e133. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples) Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dupont JM, Tost J, Jammes H, Gut IG. De novo quantitative bisulfite sequencing using the pyrosequencing technology. Anal. Biochem. 2004;333:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandberg J, Stahl PL, Ahmadian A, Bjursell MK, Lundeberg J. Flow cytometry for enrichment and titration in massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng ZL, Advani A, Melefors O, Glavas S, Nordstrom H, Ye WM, Engstrand L, Andersson AF. Titration-free massively parallel pyrosequencing using trace amounts of starting material. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies – the next generation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.