Abstract

The product of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL28 gene is essential for cleavage of concatemeric viral DNA into genome-length units and packaging of this DNA into viral procapsids. To address the role of UL28 in this process, purified UL28 protein was assayed for the ability to recognize conserved herpesvirus DNA packaging sequences. We report that DNA fragments containing the pac1 DNA packaging motif can be induced by heat treatment to adopt novel DNA conformations that migrate faster than the corresponding duplex in nondenaturing gels. Surprisingly, these novel DNA structures are high-affinity substrates for UL28 protein binding, whereas double-stranded DNA of identical sequence composition is not recognized by UL28 protein. We demonstrate that only one strand of the pac1 motif is responsible for the formation of novel DNA structures that are bound tightly and specifically by UL28 protein. To determine the relevance of the observed UL28 protein–pac1 interaction to the cleavage and packaging process, we have analyzed the binding affinity of UL28 protein for pac1 mutants previously shown to be deficient in cleavage and packaging in vivo. Each of the pac1 mutants exhibited a decrease in DNA binding by UL28 protein that correlated directly with the reported reduction in cleavage and packaging efficiency, thereby supporting a role for the UL28 protein–pac1 interaction in vivo. These data therefore suggest that the formation of novel DNA structures by the pac1 motif confers added specificity on recognition of DNA packaging sequences by the UL28-encoded component of the herpesvirus cleavage and packaging machinery.

The herpes simples virus type 1 (HSV-1) genome is composed of two segments of unique sequence, designated as long (UL) and short (US), that are flanked by inverted repeats (denoted ba and ca, respectively), such that the genome structure can be represented as anb-UL-b′a′mc′-US-ca, where n and m vary from 1 to more than 10 (1). Generation of linear unit-length genomes from concatemeric viral DNA occurs through specific DNA cleavage within the terminally repeated a sequences (as shown in Fig. 2A), which contain all of the cis-acting signals required for genome maturation (2–6). The a sequence is composed of a copy of the 20-bp direct repeat (DR1) at each end and two segments of unique sequence Uc (58 bp) and Ub (64 bp) that are separated by a series of directly repeated (DR) elements. The composition of the internal direct repeats varies between HSV-1 strains but always includes an array of 12-bp DR2 sequences.

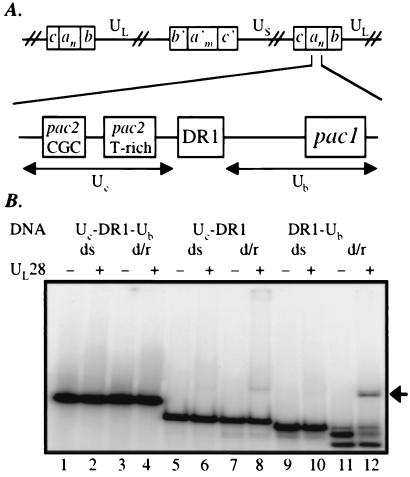

Figure 2.

(A) Diagram of the cis-acting sequences required for viral DNA cleavage/packaging. (Upper) One possible arrangement of an HSV-1 concatemer (as described in the introduction). (Lower) A detailed representation of the junction between two linear genomes and the sequences required for DNA cleavage/packaging. (B) EMSA analysis of the interaction between UL28 protein and DNA bearing pac sequences. DNA fragments spanning the regions Uc-DR1-Ub (lanes 1–4), Uc-DR1 (lanes 5–8), or DR1-Ub (lanes 9–12) were radiolabeled and either stored at −20°C [yielding the double-stranded (ds) probes present in lanes 1–2, 5–6, and 9–10] or boiled for 3 min and quickly transferred to ice before storage (probes labeled d/r, for denatured and reannealed; lanes 3–4, 7–8, and 11–12). The resultant DNA species were incubated at 5 nM in the absence or presence of UL28 protein (50 nM), and complexes were analyzed by EMSA. An arrow denotes the position at which the UL28 protein-DNA complexes migrate.

The specific signals for DNA cleavage and packaging, termed pac1 and pac2, are located within the Ub and Uc regions, respectively. The pac motifs, which were identified by their conservation 30–35 bp from the termini of mature herpesvirus genomes, have been implicated directly in mediating the cleavage and packaging reaction (7–10). pac1 is characterized primarily by two stretches of five to eight G residues separated by a 3- to 7-nt T-rich region, whereas pac2 contains a conserved CGCCGCG motif located near a run of 5 to 10 T's (8). The DR1 element contains the site of DNA cleavage, although this sequence itself is not required for double-stranded break formation (5, 11). The DR2 repeats are also dispensable for the cleavage/packaging process, although the sequences flanking both the Uc and Ub regions have been shown to enhance cleavage/packaging activity (9).

HSV-1 encodes six proteins that are required for DNA cleavage and packaging (UL6, UL15, UL17, UL28, UL32, UL33, reviewed in refs. 12 and 13). The fact that each of these proteins is indispensable for cleavage of the viral concatemer suggests that many or all of the proteins act together in a multicomponent complex. However, the respective functions of these cleavage/packaging proteins have yet to be elucidated. Inferences from preliminary genetic and biochemical data and comparisons drawn with double-stranded DNA bacteriophages suggest that the cleavage/packaging reactions are initiated through recognition of the pac1 and pac2 sequences within concatemeric viral DNA (reviewed in refs. 12, 14, and 15). Thus, identification of the protein factor(s) involved in these initial DNA-binding events represents a fundamental step toward understanding the cleavage/packaging process.

Recent studies of human cytomegalovirus indicated that crude cell lysates containing the human cytomegalovirus homolog of the HSV-1 UL28 protein possess a pac sequence-specific DNA-binding activity (16). The use of unpurified cell lysates, however, made it difficult to characterize this putative interaction or to determine whether the observed DNA binding was a direct or indirect effect of the viral protein.

To investigate the possibility that there is a direct and specific interaction between the HSV-1 UL28 protein and pac DNA sequences, we have purified UL28 protein to homogeneity and begun an analysis of its properties in vitro. Our data reveal that the UL28 protein possesses a pac1 DNA-binding activity that is both sequence and structure specific and suggest that this interaction plays an essential role in the cleavage/packaging reactions.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and Protein Purification.

The coding region of UL28 (excluding the stop codon) was amplified by PCR of HSV-1 DNA (F strain) with the use of the following primers: 5′-AAGGATCCATGGCCGCCCCGGTGTCCGAGCCC-3′, which contains a BamHI site followed by the N-terminal coding sequence of UL28, and 5′-TTTAAGCTTATACGGGGGCCCGTCGTGCC-3′, which harbors both the C terminus of UL28 and an EcoRI site. The PCR product was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, gel purified, and cloned into the same sites of the vector pET30a-collapse. This vector was derived from pET30a (Novagen), which had been collapsed between the NdeI and EcoRV sites to remove the N-terminal tags and protease cleavage sites. The resulting construct contained the entire coding sequence of UL28 cloned in-frame with the C-terminal six histidine tag encoded by the vector. Plasmids were sequenced to confirm the predicted genotype, followed by transformation into BL21 λDE3 Codon-Plus bacteria (Stratagene). Transformed bacteria were grown in LB medium with 30 μg/ml kanamycin to an OD600 of 0.5. Protein production was induced by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside, and incubation of the bacterial cultures continued for 2.5 h. Cells were harvested and frozen at −80°C.

Cell pellets were lysed by Dounce homogenization in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme. The insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation, and this pellet was washed with the above buffer lacking lysozyme. The material remaining in inclusion bodies was solubilized in the above buffer containing 6 M guanidine HCl. After stirring for 1 h at 4°C, this protein fraction was centrifuged, and the supernatant was passed through a 0.8-μm filter to remove any remaining insoluble material. Preequilibrated Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) were added and incubated with the solubilized protein fraction for 30 min at 4°C. The unbound protein was removed, and the beads were washed extensively. UL28 protein was renatured by dilution of the guanidine HCl and eluted from the beads with 250 mM imidazole according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Soluble eluates were dialyzed extensively against storage buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.9), 200 mM KCl, 50% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM l-arginine, and 0.5% Tween-20. Soluble protein samples were aliquoted, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C until use.

DNA Probes.

Double-stranded DNA fragments were obtained by restriction digestion of plasmids bearing the desired DNA packaging sequences (a gift from Bernard Roizman, University of Chicago). The fragment spanning Uc-DR1-Ub was excised with the use of the restriction enzymes BamHI and PstI, whereas fragments comprising regions Uc-DR1 and DR1-Ub were released with BamHI and filled in with Klenow polymerase in the presence of [α-32P]dGTP (Amersham Pharmacia) and 33 μM dCTP, dATP, and dTTP. The denaturation/renaturation procedure was performed by boiling each fragment (present at 50 nM) for 3 min, followed by rapid cooling on ice. An aliquot of each fragment was analyzed on a denaturing gel to ensure that the DNA was uniformly of the expected length. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by GIBCO/BRL and purified by PAGE. Oligonucleotide probes were end-labeled with the use of T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Pharmacia), and free nucleotides were removed with P6 Micro-Spin columns (Bio-Rad). Labeled DNA was stored at −20°C in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 50 mM KCl until use. Synthetic DNA strands were denatured by transfer to a heating block at 95°C, followed by slow reannealing as the block came to room temperature. A comparison of the DNA species present before and after this process demonstrated that heat treatment of the Ub upper and pac1 oligonucleotides significantly enhanced the population of slowly migrating DNA species (shown by asterisks in Figs. 3 and 4). Subsequent gel purification of the species labeled Ub upper* or pac1* (Figs. 3 and 4), followed by heat treatment, allowed for equilibration of some of these slowly migrating species back to single-stranded DNA.

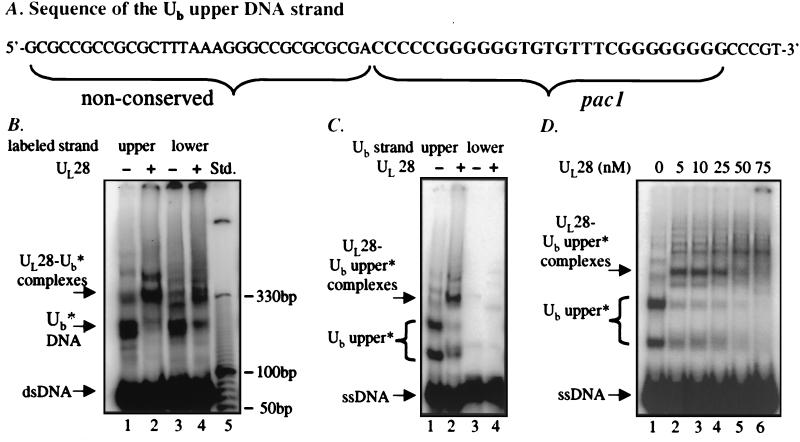

Figure 3.

(A) The sequence of the Ub upper strand probe (63 nt), depicting components of nonconserved sequence as well as the conserved pac1 motif. (B) Analysis of UL28 protein binding to Ub DNA. DNA species formed by annealing complementary oligonucleotides corresponding to the Ub region were assayed for binding by UL28 protein. The labeled Ub upper strand was annealed to the unlabeled lower strand (lanes 1 and 2) or the labeled Ub lower strand annealed to an unlabeled upper strand (lanes 3 and 4). The DNA substrates (5 nM) were incubated in the presence or absence of 25 nM UL28 protein, and complexes were analyzed by EMSA. The relative mobility of the double-stranded DNA fragment (dsDNA), slowly migrating DNA species (Ub*), and specific complexes formed (UL28- Ub* complexes) are noted at the Left and can be compared with the DNA molecular size standard present in lane 5. (C) Investigation of strand specificity for the UL28 protein–Ub interaction. DNA species formed by the individual oligonucleotides corresponding to the upper (lanes 1 and 2) and lower (lanes 3 and 4) strands of the Ub region were assayed for interaction with UL28. The DNA probes (5 nM) were incubated in the absence or presence of the UL28 protein (10 nM), and complexes were analyzed EMSA. The slowly migrating species formed by the upper strand are labeled as Ub upper*. (D) Increasing concentrations of UL28 protein incubated with the Ub upper strand. A constant 5 nM Ub upper strand oligonucleotide DNA was incubated with UL28 at the final concentrations noted above each lane.

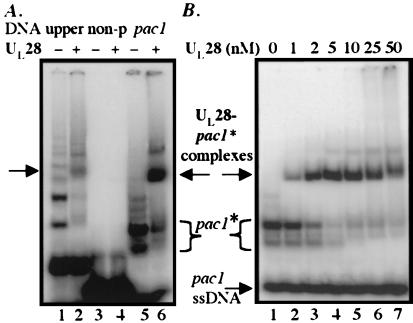

Figure 4.

(A) Localization of the binding site for UL28 protein. Comparison was made between UL28 protein binding to oligonucleotides bearing the 63-nt Ub upper strand (lanes 1 and 2) and binding to probes comprising a 31-nt nonconserved sequence component (non-p, lanes 3 and 4) and the 27-nt pac1 motif (lanes 5 and 6). DNA present at 5 nM was incubated in the absence or presence of 10 nM UL28 protein and complexes analyzed by EMSA. The slowly migrating DNA species formed by the pac1 oligonucleotide are denoted as pac1*. (B) Determination of the binding affinity of UL28 protein for pac1* DNA. The pac1 oligonucleotide, present at 5 nM, was incubated with increasing concentrations of UL28 protein (as noted), and complexes were visualized by EMSA.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA).

Labeled DNA (5 nM) and purified UL28 protein (at the concentrations noted) were incubated in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.6), 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 100 nM ZnCl2, 1 mM DTT, with 0.1 μg/μl acetylated BSA and nonspecific DNA competitor. For the double-stranded DNA templates (Figs. 2 and 3B), 1 μg poly(dA-dT) (Amersham Pharmacia) was used as the competitor species, whereas the N-terminal UL28-BamHI oligonucleotide (described above) was present at a final concentration of 1 μM in the experiments shown in Figs. 3C–5. Reactions in 10 μl were incubated at 37°C for 30 min before loading onto a 4.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel, and complexes were separated from free DNA by electrophoresis at room temperature for 2 h at 200 V in TBE buffer. Quantitation was performed using a PhosphorImager and imagequant software (Molecular Dynamics). Values were expressed as the ratio of DNA bound to free DNA versus the concentration of UL28 protein. DNA bound was defined as the quantity of DNA that migrated within the bracket denoting UL28 protein–DNA complexes, and free DNA was all DNA that migrated faster than the bound species.

Results

Purification of the HSV-1 UL28 Protein.

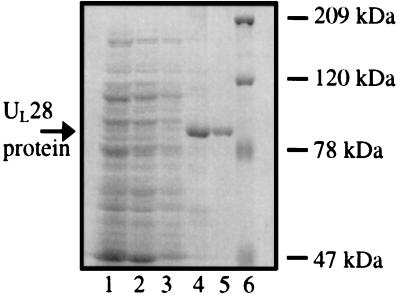

To facilitate purification, a plasmid (pJB233) was constructed that encodes full-length UL28 protein tagged with six histidine residues at the C terminus. The resultant protein was affinity purified as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 1, the UL28 protein remained insoluble during lysis of the bacterial pellet (lane 2) and a subsequent washing step (lane 3). Insoluble material was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 6 M guanidine HCl, and the solubilized fraction was incubated with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose beads. The bound protein (lane 4) was renatured, eluted from the beads, and dialyzed extensively. The final protein preparation (lane 5) was aliquoted and frozen until use. Analysis of this protein sample by gel filtration yielded one discrete peak that eluted as predicted by the molecular weight of UL28 (data not shown), indicating that refolded UL28 protein was present as a homogeneous, monomeric species.

Figure 1.

Purification of the HSV-1 UL28 protein. Protein samples from each major step in the purification procedure were analyzed by SDS/PAGE. Lane 1, initial cell lysate; lane 2, supernatant after lysis; lane 3, supernatant from wash of the insoluble material; lane 4, Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose beads, after incubation with the solubilized protein fraction and extensive washing; lane 5, eluate, after dialysis; lane 6, Bio-Rad high-molecular-weight protein marker.

Analysis of DNA Binding Activity.

The minimal cis-acting elements necessary for efficient cleavage/packaging of concatemeric HSV-1 DNA are located within the reiterated a sequences (diagrammed in Fig. 2A) in the region containing Uc-DR1-Ub (5–9). To investigate the possibility of a specific interaction between UL28 protein and pac sequences, we isolated several DNA fragments bearing various segments of the Uc-DR1-Ub region and tested each of these for recognition by UL28 protein with the use of electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) followed by PhosphorImager analysis.

The DNA probes used in this study contained the regions Uc-DR1-Ub (211 bp), Uc-DR1 (130 bp), or DR1-Ub (115 bp). As shown in Fig. 2B, there was very little interaction between UL28 protein and the double-stranded fragments containing regions Uc-DR1-Ub (lanes 1 and 2), Uc-DR1 (lanes 5 and 6), or DR1-Ub (lanes 9 and 10), indicating that the DNA packaging sequences within this context were not efficiently recognized by UL28 protein.

However, recent studies have demonstrated that DNA fragments bearing the herpesvirus origin of replication, oriS, can be converted by heat denaturation into novel DNA conformations that are bound tightly by the HSV-1 origin binding protein (17) and OF-1 host proteins (18). To test the possibility that herpesvirus DNA packaging sequences could be recognized when treated in a similar manner, the pac-containing fragments were heat denatured, rapidly annealed on ice, and analyzed by EMSA. The migration of the DNA fragment spanning the region Uc-DR1-Ub was not altered by the denaturation/renaturation process (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 1 and 3), nor was the heat-treated probe bound by UL28 protein (lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, rapid annealing of the denatured DR1-Ub fragment produced little double-stranded DNA, instead yielding a number of single-stranded or alternate DNA species (Fig. 2B, lanes 11 and 12). Remarkably, the novel DNA species were recognized by UL28 protein, leading to the appearance of a band corresponding to nucleoprotein complexes (Fig. 2B, lane 12, denoted at right by an arrow) and a decrease in intensity of the bands migrating as free DNA. Although the results are much less dramatic with the Uc-DR1 fragment, a small amount of quickly migrating DNA formed upon denaturation/renaturation of this probe, and this DNA was bound by UL28 protein and shifted into discrete complexes (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 8). These data suggest that heat treatment, particularly of the shorter pac-containing DNA fragments, allows the DNA strands to adopt unique structures that serve as substrates for UL28 protein binding. Because the observed binding was more pronounced with the DNA fragment containing the DR1-Ub sequences than with that bearing UC-DR1, further analyses were focused on the putative interaction between UL28 protein and the Ub region.

Characterization of the UL28 Protein–Ub Interaction.

To conduct these investigations, complementary oligonucleotide probes consisting of Ub sequences were synthesized. The sequence of the upper DNA strand of Ub is shown in Fig. 3A. After the oligonucleotides comprising the upper and lower DNA strands were radiolabeled separately, each strand was mixed with unlabeled complementary oligonucleotide and heated to 95°C, and complementary strands were allowed to anneal while slowly returning to room temperature.

As shown in Fig. 3B (lanes 1 and 3), the electrophoretic profile of the annealed oligonucleotides consisted of several slowly migrating minor bands (labeled Ub*) in addition to the prominent band representing double-stranded Ub DNA. The migration pattern varied only slightly, depending on which strand was radiolabeled (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 3), indicating that virtually all of the DNA species contained both upper and lower DNA strands. The addition of UL28 protein shifted the slowly migrating DNA species (Ub*) into novel bands corresponding to nucleoprotein complexes (UL28-Ub* complexes), whereas the duplex DNA remained unchanged. This result was reproducibly obtained with UL28 protein concentrations up to 250 nM (data not shown), again suggesting that aspects of the Ub region are specifically recognized as nonduplex DNA structures.

To test the possibility that the determinants for UL28 protein binding were located preferentially in one of the Ub DNA strands, labeled single-stranded oligonucleotides corresponding to the upper or lower strands of Ub were incubated individually with UL28 protein and subjected to EMSA. These results are shown in Fig. 3C. Whereas the Ub lower strand probe migrated uniformly at the position anticipated for a single-stranded DNA of 63 nt (Fig. 3C, lane 3), the Ub upper strand probe formed a number of species that migrated more slowly than expected (lane 1, major bands labeled Ub upper*). These slowly migrating DNA species were specifically bound by UL28 protein, leading to the formation of discrete complexes (Fig. 3C, lane 2, denoted as UL28-Ub* complexes). In contrast, no complex formation was observed between UL28 protein and the lower Ub DNA strand (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 and 4). To verify the specificity of this interaction, increasing amounts of UL28 protein were added to binding reactions containing a constant concentration of Ub upper-strand DNA. As shown in Fig. 3D, the slowly migrating DNA species (Ub upper*) were depleted and shifted into nucleoprotein complexes at low concentrations of UL28 protein, whereas the quantity of single-stranded, presumably unstructured, Ub upper DNA was unaltered, even at 75 nM UL28 protein (lane 6). Quantitation by PhosphorImager analysis confirmed that the level of single-stranded Ub upper DNA remained constant for UL28 concentrations up to 250 nM (Fig. 3D and data not shown). Hence the novel conformations adopted by the Ub upper strand represent the specific targets of UL28 protein binding.

Localization of the Binding Site.

The hypothesis that the UL28 protein–Ub DNA interaction observed in this work plays a role in vivo predicts that recognition by UL28 protein would be specific for the conserved sequences within this region, namely the pac1 motif. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized truncated oligonucleotides composed of either the pac1 element (27 nt) or 31 nt of nonconserved Ub sequence (as depicted in Fig. 2A). Fig. 4A shows an EMSA analysis of UL28 protein binding to these probes. As demonstrated previously, the full-length Ub upper oligonucleotide formed several slowly migrating species that were bound by UL28 protein (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2). The 27-nt probe comprising the pac1 motif also formed two major species with markedly low mobility, denoted as pac1* (Fig. 4A, lane 5). Upon the addition of UL28 protein, these DNA species were bound tightly and shifted into discrete complexes (lanes 5 and 6). However, there was no detectable binding of the UL28 protein to the oligonucleotide composed of the nonconserved, or non-pac1, component of the Ub region (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4). In confirmation of the observed binding specificity, an identical experiment was performed with the use of oligonucleotides bearing the two components of the Ub lower strand (i.e., the conserved pac1 motif and nonconserved segment); neither oligonucleotide was bound by UL28 protein (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that the specific determinants for UL28 protein binding lie within novel structures formed by the upper strand of the conserved pac1 element. To further characterize this interaction, increasing amounts of UL28 protein were incubated with 5 nM pac1 DNA, and the quantity of nucleoprotein complexes formed at each concentration was evaluated by EMSA (Fig. 4B). This analysis demonstrated that the pac1* species were bound with a very high affinity by UL28 protein [apparent dissociation constant (Kd) of 2.2 ± 0.7 nM], whereas the single-stranded pac1 DNA was not bound.

Correlation of in Vitro DNA Binding with in Vivo Cleavage and Packaging Activity.

To validate that the observed UL28 protein--pac1 interaction was relevant in herpesvirus-infected cells, we took advantage of the fact that a number of 4- to 6-nt changes in the pac1 motif of murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) had been tested for their effects on DNA cleavage/packaging in vivo (10 and Michael McVoy, personal communication). As mentioned above, the conserved characteristics of pac1 are a central T-rich region flanked by two strings of five to eight G residues (8). Using an in vivo cleavage/packaging assay, McVoy and coworkers demonstrated that the poly-G stretches were extremely important for efficient MCMV DNA cleavage/packaging, whereas the central T-rich segment was not (10 and M. McVoy, personal communication).

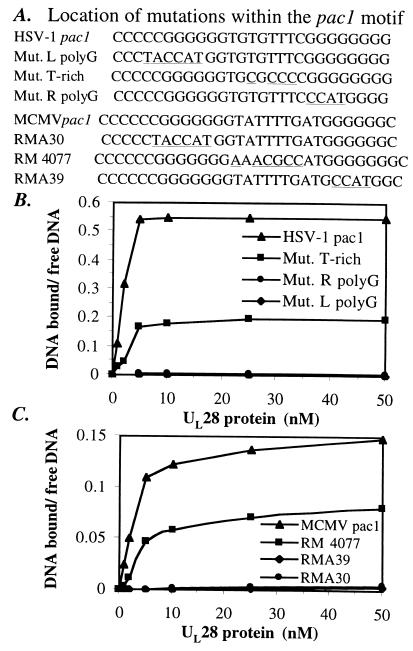

To determine whether or not the binding of UL28 protein to pac1 DNA in vitro would correlate with these observations, we synthesized oligonucleotides consisting of the wild-type and previously studied mutant MCMV pac1 sequences as well as the corresponding mutations within the context of the HSV-1 pac1 sequence (oligonucleotide sequences given in Fig. 5A). The affinity of UL28 protein for these DNA substrates was determined by performing titration experiments (such as that shown in Fig. 4B), using each of the described pac1 oligonucleotides. The results are summarized in Fig. 5B (for HSV-1 sequences) and Fig. 5C (for MCMV sequences) as the ratio of DNA bound to free DNA plotted against the concentration of UL28 protein.

Figure 5.

Correlation of in vitro binding affinity of UL28 protein with in vivo cleavage/packaging efficiency. (A) Sequence of the wild-type pac1 motif and mutant pac1 oligonucleotides. Nucleotide positions that differ from wild-type pac1 sequences are underlined. MCMV pac1 sequences are those that have been studied in vivo for their effects on cleavage/packaging (ref. 10 and Michael McVoy, personal communication). The relative efficiency of cleavage/packaging observed for each mutant sequence as compared with MCMV wild-type pac1 (set at 100%) is as follows: RMA30, <2.5%; RM4077, 33%; RMA39, ≈3%. Binding affinity for each of the HSV-1 (B) and MCMV (C) pac1 oligonucleotides was determined. A concentration of 5 nM of each oligonucleotide was incubated with increasing concentrations of UL28 protein, and free DNA was separated from bound DNA by EMSA. The level of complex formation was determined by calculating the ratio of DNA bound to free DNA as a function of UL28 protein concentration (nM). Values shown represent the average of two to four experiments.

The wild-type HSV-1 pac1 motif was bound by UL28 protein more tightly than was the MCMV pac1 sequence or any of the mutant pac1 oligonucleotides (Fig. 5 B and C); however, the MCMV pac1 motif was bound significantly by the UL28 protein (Fig. 5C). This result suggests that the characteristics of the pac1 motif recognized by UL28 protein are conserved between HSV-1 and MCMV. Both the HSV-1 and MCMV oligonucleotides bearing mutations within the central T-rich region were bound by UL28 protein (Fig. 5B, HSV-1 Mut. T-rich, and Fig. 5C, MCMV RM4077) at levels consistent with the 3-fold reduction in cleavage/packaging efficiency observed for RM4077 in vivo (10). Mutation of either the left (L) or right (R) poly-G stretches (corresponding to MCMV RMA30 and RMA39, respectively) severely impaired cleavage/packaging in vivo (<2.5% of wild-type activity for RMA30 and ≈3% of wild type for RMA39; ref. 10 and M. McVoy, personal communication). In agreement with these data, all of the pac1 oligonucleotides mutated in either the left or right poly-G regions yielded barely detectable levels of complexes with 1–100 nM UL28 protein (Fig. 5 B and C, and data not shown). Thus there is a remarkably good correlation between DNA-binding activity measured in vitro and the efficiency of the related mutant sequences to serve as substrates for cleavage/packaging in MCMV-infected cells.

Discussion

Although it has been known for some time that the cis-acting signals necessary for DNA cleavage and packaging are located within the pac1 and pac2 elements, the proteins that recognize these motifs have not been identified. The search for factors that bind pac sequences has detected several viral proteins (19) and a host protein (20) that interacted with DNA containing pac2, but the involvement of these proteins in cleavage/packaging has yet to be established. Recently, baculovirus-infected insect cell lysates containing the human cytomegalovirus homolog of the UL28 protein were reported to possess pac sequence-specific DNA-binding and nuclease activities (16). Our current work demonstrates a direct, specific interaction between UL28 protein and DNA bearing the pac1 motif; however, no UL28-dependent DNA cleavage activity was observed under the various conditions tested (data not shown). The difference in reported activities for UL28 protein and its human cytomegalovirus homolog may result from improper folding or lack of appropriate modifications of recombinant UL28 protein in bacteria or from the fact that the unpurified cell lysates used in the previous study contained additional factors that affected the results obtained (16).

Our data support the emerging concept that nonduplex DNA structures may form in vivo and serve as specific signals for recognition by DNA-binding proteins. The mode of interaction proposed herein for UL28 protein with pac1 DNA is reminiscent of the binding of the herpesvirus origin binding protein to its target site (17). Although recognition of the herpesvirus origin of replication sequence (oriS) by origin binding protein has been well established (21), it was determined only recently that high-affinity binding of the oriS site by origin binding protein involves the formation of novel DNA structures in which parts of the oriS sequence are extruded as single strands (17). Moreover, the two DNA strands appear to form different structures, only one of which is bound tightly by origin binding protein (17).

Similarly, our data demonstrate that denaturation/renaturation of double-stranded pac-containing DNA allows for the formation of novel, presumably single-stranded structures that are recognized by UL28 protein (see quickly migrating species, Lanes 11 and 12, Fig. 2). However, novel conformations are also present within partially double-stranded DNA (such as the slowly migrating Ub* species shown in Fig. 3B), thus suggesting that formation of the structural motif recognized by UL28 protein in vivo involves extrusion of the Ub upper DNA strand.

Although the formation of these novel structures appears to be thermodynamically unfavorable when the pac1 motif is located within linear duplex DNA, the complex nature of the viral concatemer and the presence of flanking sequences may facilitate pac1 structure formation in vivo. This possibility is supported by evidence that sequences flanking the Ub and Uc regions increase the efficiency of pac sequence recognition by the cleavage/packaging machinery (9). The sequences adjacent to the pac1 motif (≈18 bp away) are the DR2 repeats. Although the conformation adopted by the DR2 in vivo has yet to be defined precisely, under superhelical tension these sequences adopt anomalous conformations referred to as anisomorphic DNA (22). Strikingly, structural studies showed sites of S1 nuclease hypersensitivity (indicative of single-stranded DNA) located both within the DR2 repeats and at the junction between the DR2 and flanking sequences (22). Thus the formation of anisomorphic DNA structures within the DR2 could affect the conformation of nearby DNA sequences. Furthermore, structural analyses of DNA packaging sequences from human Herpesvirus-6 on supercoiled plasmids have detected several sites of S1 nuclease hypersensitivity located specifically within the pac elements, indicating that the pac motifs may also form novel structures (23). In light of these data, it is tempting to speculate that the configuration adopted by the DR2 repeats could aid in the formation of alternative, partially single-stranded pac1 structures in vivo, thereby stimulating recognition by UL28 protein.

The idea that there might be a correlation between the formation of novel structures by pac1 and enhanced cleavage/packaging efficiency is also supported by our investigations of the MCMV and HSV-1 pac1 mutant oligonucleotides. In these studies, it was noted that the pac1 mutants that were most severely impaired in UL28 protein binding were also those that adopted the least secondary structure, as defined by the quantity of oligonucleotide that migrated anomalously (such as the pac1* species, Fig. 4; data not shown). Specifically, and in agreement with the data of McVoy and coworkers, mutations that altered the sequence composition within the pac1 G-rich stretches drastically decreased both the formation of novel structures and binding by UL28 protein, whereas mutations within the central T-rich segment had less effect on the ability to form pac1*-like structures and the level of UL28 protein binding (Fig. 5 and data not shown).

In summary, the pac1 DNA-binding activity reported in this work represents an important step toward an understanding of the cleavage/packaging reactions. The cleavage and packaging proteins present themselves as particularly attractive targets for antiviral therapies, inasmuch as they perform functions essential to the viral life cycle yet have no homologues within host cells. Hence, further biochemical characterization of these proteins is hoped to provide insight into the development of novel therapeutics. Moreover, the discovery that the cleavage and packaging factors, like the proteins needed for viral replication, may bind their target sequences as non-B-form DNA suggests that the complex structure of viral DNA plays a role in modulating DNA–protein interactions within an infected cell. The nature of the novel pac1 structures, and whether they preexist within the context of the viral concatemer, or are induced to form during the cleavage and packaging process, have not yet been determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael McVoy for his communication of unpublished data, Bernard Roizman for plasmids containing DNA packaging sequences, Volker Vogt for his valuable insights, and Jeff Roberts for the use of equipment. We also thank Stephanie Rempel and Phillipa Beard for providing preliminary data relevant to these studies. This research was supported by Public Health Service Grant GMRO150740 to J.D.B.

Abbreviations

- HSV-1

herpes simplex virus type 1

- DR

direct repeats

- MCMV

murine cytomegalovirus

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Roizman B, Sears A E. In: Fundamental Virology. Fields B N, editor. New York: Raven; 1996. pp. 1048–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spaete R R, Frenkel N. Cell. 1982;30:295–304. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocarski E S, Roizman B. Cell. 1982;31:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stow N D, McMonagle E C, Davison A J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:8205–8220. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.23.8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varmuza S L, Smiley J R. Cell. 1985;41:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deiss L P, Frenkel N. J Virol. 1986;57:933–941. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.933-941.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasseri M, Mocarski E S. Virology. 1988;167:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deiss L P, Chou J, Frenkel N. J Virol. 1986;59:605–618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.3.605-618.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smiley J R, Duncan J, Howes M. J Virol. 1990;64:5036–5050. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5036-5050.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McVoy M A, Nixon D E, Adler S P, Mocarski E S. J Virol. 1998;72:48–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.48-56.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mocarski E S, Deiss L P, Frenkel N. J Virol. 1985;55:140–146. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.1.140-146.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homa F L, Brown J C. Rev Med Virol. 1997;7:107–122. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(199707)7:2<107::aid-rmv191>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salmon B, Cunningham C, Davison A J, Harris W J, Baines J D. J Virol. 1998;72:3779–3788. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3779-3788.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black L W. BioEssays. 1995;17:1025–1030. doi: 10.1002/bies.950171206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catalano C E. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:128–148. doi: 10.1007/s000180050503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogner E, Radsak K, Stinski M F. J Virol. 1998;72:2259–2264. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2259-2264.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aslani A, Simonsson S, Elias P. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5880–5887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker R O, Murata L B, Dodson M S, Hall J D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30050–30057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou J, Roizman B. J Virol. 1989;63:1059–1068. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1059-1068.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemble G W, Mocarski E S. J Virol. 1989;63:4715–4728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4715-4728.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elias P, O'Donnell M E, Mocarski E S, Lehman I R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6322–6326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wohlrab F, McLean M J, Wells R D. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:6407–6416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng H, Dewhurst S. J Virol. 1998;72:320–329. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.320-329.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]