Abstract

As is generally true with other age-related diseases, Alzheimer's disease (AD) involves oxidative damage to cellular components in the affected tissue, in this case the brain. The causes and consequences of oxidative stress in neurons in AD are not fully understood, but considerable evidence points to important roles for accumulation of amyloid β-peptide upstream of oxidative stress and perturbed cellular Ca2+ homeostasis and energy metabolism downstream of oxidative stress. The identification of mutations in the β-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 as causes of some cases of early onset inherited AD, and the development of cell culture and animal models based on these mutations has greatly enhanced our understanding of the AD process, and has greatly expanded opportunities for preclinical testing of potential therapeutic interventions. In this regard, and of particular interest to us, is the elucidation of adaptive cellular stress response pathways (ACSRP) that can counteract multiple steps in the AD neurodegenerative cascades, thereby limiting oxidative damage and preserving cognitive function. ACSRP can be activated by factors ranging from exercise and dietary energy restriction, to drugs and phytochemicals. In this article we provide an overview of oxidative stress and AD, with a focus on ACSRP and their potential for preventing and treating AD. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1519–1534.

Introduction

Alzheimer's Disease (AD) was first described as a relatively rare disorder by Alois Alzheimer in 1906 and now, ∼1 century later, nearly 5 million Americans are living with AD and the numbers are rapidly rising as baby boomers enter the AD danger zone of >65 years of age. Clinically, AD is diagnosed by (progressive) memory impairment and reduced size of the hippocampus, temporal, and frontal lobes as detected by magnetic resonance imaging analysis. One of the hallmark pathologies in AD is the altered proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) that leads to accumulation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) in extracellular plaques (112). Another prominent alteration is the presence of the so-called neurofibrillary tangles that are fibrillar bundles of the microtubule-associated protein tau A-beta plaques and tangles (17). There is abundant evidence that oxidative stress plays a role in nerve cell dysfunction and death in AD. Because this evidence has been reviewed previously (25, 117), we will briefly describe the salient features of the events that appear to play major roles in generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) in AD on the one hand, and the mechanisms by which ROS contribute to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal degeneration.

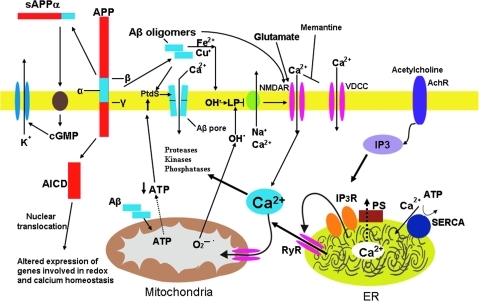

Large spherical (hundreds of micrometers in diameter) extracellular accumulations of Aβ, known as amyloid plaques, are a defining feature of AD. There is considerable evidence that Aβ can damage and kill neurons by a mechanism involving oxidative stress (Fig. 1). In AD, Aβ self-aggregates, and when small oligomers of Aβ are forming in the early stages of aggregation, hydrogen peroxide is generated from the peptide itself in a process requiring oxygen and trace amounts of Fe2+ and Cu+ (25). Aβ aggregation tends to occur on cell membranes resulting in membrane lipid peroxidation and the generation of the toxic aldehyde 4-hydroxynonenal, which can impair synaptic function and disrupt cellular Ca2+ and energy metabolism by covalently modifying proteins on cysteine, lysine, and histidine residues. Proteins whose functions have been shown to be impaired by 4-hydroxynonenal are plasma membrane Na+/K+- and Ca2+-ATPases, and glucose and glutamate (glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain) transporters (113). As a consequence, neurons become unable to maintain cellular ion homeostasis, energy is depleted, and the neurons may degenerate as the result of Ca2+ overload and triggering of apoptosis (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Molecular and cellular alterations involved in neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease (AD). The β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) is cleaved by β-secretase (β) and γ-secretase (γ), resulting in the liberation of the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ). Aβ may interact with Fe2+ and Cu+ to generate hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical, resulting in membrane lipid peroxidation that generates toxic aldehydes that impair the function of membrane Na+ and Ca2+ ATPases (ion pumps). The membrane then depolarizes, and glutamate receptor channels (N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor) and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCC) open and Ca2+ enters the cytoplasm. Aβ may also form Ca2+-permeable pores in the plasma membrane; the interaction of Aβ with the plasma membrane may be facilitated by binding to phosphatidylserine (PtdS). Aβ may also act directly on mitochondria to induce superoxide anion radical (O2•−) production, Ca2+ overload, and decreased ATP production. Amyloidogenic APP processing prevent α-secretase (α) cleavage of APP, which normally generates an activity-dependent secreted form of APP (sAPPα) that engages a signaling pathway involving cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) that activates K+ channels, thereby hyperpolarizing the membrane and reducing Ca2+ influx and free radical production. Amyloidogenic processing also generates an intracellular APP domain (AICD) that can translocate to the nucleus and modify gene transcription in ways that perturb redox and Ca2+ homeostasis. Presenilin-1 (PS) functions as a Ca2+ leak channel in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and PS mutations may impair this Ca2+ leak channel function resulting in excessive accumulation of Ca2+ in the ER and enhanced Ca2+ release through ryanodine receptor (RyR) and IP3 receptor (IP3R) channels. There is also evidence that PS can interact directly or indirectly with RyR and smooth ER Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) to alter ER Ca2+ release and uptake. Altogether, the cascade of events described here first impairs synaptic transmission and may ultimately kill neurons in AD. Modified from Bezprozvanny and Mattson (16). For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars.

Although Aβ plays an important role in oxidative stress and neuronal degeneration in AD, the presence of Aβ plaques is not sufficient for a diagnosis of AD. The reason is that some individuals with perfectly normal cognitive function exhibit large amounts of plaques (84), suggesting that neurons in these individuals are able to withstand any oxidative attack by Aβ. We are learning that there may be mechanisms by which brain cells respond adaptively to aging and counteract disease processes. This concept falls under the broader definition of hormesis, a process in which cells respond to low levels of stress by activating adaptive cellular stress response pathways (ACSRP) that promote cell repair and survival (110). In this situation hormesis acts to precondition cells, so they are better prepared when larger insults strike. Studies have shown that mental and physical activity can stimulate ACSRP in the brain, which may be the reason physically and mentally active individuals are at a reduced risk for AD. On the other hand, factors such as obesity and diabetes may increase the risk for AD by impairing ACSRP. The notion of failed ACSRP as a pivotal factor in AD, and of lifelong activation of ACSRP conferring resistance to AD, is the subject of the remainder of this article. While the present article focuses on adaptive cellular stress responses, there are many other molecular and cellular processes that are not stress responses, whose dysfunction has been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, including the amyloid cascade, oxidative stress, accumulation of damaged proteins, and mitochondrial impairment (112).

Evidence That ACSRP Are Impaired in AD

Studies of neurons in culture and in vivo have elucidated mechanisms by which the cells can increase their resistance to a range of adverse conditions, including oxidative stress. One mechanism involves the activity-dependent production of neurotrophic factors that activate receptors coupled to kinases and transcription factors that induce expression of genes encoding cytoprotective proteins. Three growth factors known to support the survival of neurons that are vulnerable in AD are fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), nerve growth factor (NGF), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). FGF2 can protect neurons from the pathogenic actions of mutant presenilin-1 (PS1) and Aβ, and may do so by suppressing oxidative stress and stabilizing cellular calcium homeostasis (65). FGF2, NGF, and BDNF have all been shown to increase the resistance of neurons to oxidative stress, most likely by upregulating expression of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutases (SOD) and antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2.

In AD, FGF2 may be sequestered in Aβ plaques, thereby reducing the amount of FGF2 available to activate its receptors in neurons. NGF supports the survival and plasticity of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain; these neurons innervate the hippocampus where their axon terminals release acetylcholine, a process critical for learning and memory (172). The acetylcholinesterase inhibitors used to treat AD patients can enhance learning and memory by increasing the amount of synaptic acetylcholine. Studies of postmortem brain tissue from AD patients demonstrated a depletion of NGF in brain regions affected by the disease, including the hippocampus. The potential therapeutic benefit of NGF was tested in clinical trials in which NGF was infused into the lateral ventricle of AD patients; unfortunately, the NGF caused intolerable back pain, presumably because of actions in the spinal cord, and the trial was halted. BDNF is a particularly important neurotrophic factor because it is produced and released from neurons in an activity-dependent manner, and plays pivotal roles in synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, neuron survival, and neurogenesis (118, 156). Brain tissue samples from AD patients exhibit reduced levels of both BDNF and activated cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor that induces BDNF production (157). BDNF production is stimulated by at least three different behaviors that are believed to reduce the risk for AD, namely, exercise, cognitive stimulation, and dietary energy restriction (see next section below).

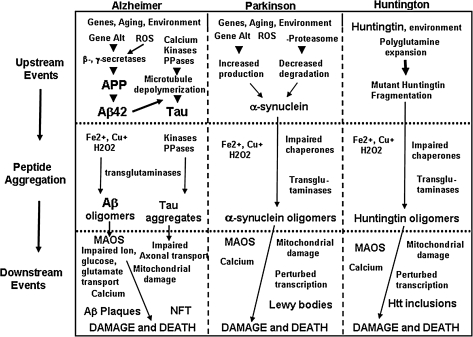

Three additional ACSRP that may be compromised in aging and AD are antioxidant response systems, protein chaperone systems, and protein degradation pathways. The increase in oxidative stress that occurs in brain cells with aging and early in the course of AD is associated with compensatory upregulation of some antioxidant enzymes (187), but also the impairment of other antioxidant defenses such as the plasma membrane redox system (78), and depletion of low-molecular-weight antioxidants, including glutathione (102). Protein chaperones such as heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), and HSP27 have been reported to modify one or more processes involved in AD, including Aβ aggregation, Aβ toxicity, and oxidative stress (88). The accumulation of Aβ, tau, and other proteotoxic proteins may normally be prevented, in part, by degradation of the aberrant proteins in the proteasome (Fig. 2). However, in AD the function of the proteasome is impaired, apparently as the result of oxidative damage to the proteasome proteins themselves (29, 85). So, it appears that beginning early in the disease process neurons in AD suffer from increased oxidative and proteotoxic stress, adaptive responses to this cellular stress are engaged, but ultimately the ACSRPs fail.

FIG. 2.

Working model for the mechanisms of proteotoxic damage to neurons in AD, Parkinson's disease (PD), and Huntington's disease (HD). Oxidative stress resulting from the aging process, combined with environmental and genetic factors, promotes disease-specific molecular perturbations that play key roles in the neurodegenerative cascades in AD, PD, and HD. In each disorder there are one or more pathogenic, self-aggregating proteins involved: Aβ and tau in AD, α-synuclein in PD, and huntingtin in HD. Events involving oxidative stress upstream and downstream of pathogenic protein aggregations are illustrated. Aβ42, amyloid β-peptide 1-42; Htt, huntingtin; MAOS, membrane-associated oxidative stress; NFT, neurofibrillary tangles; PPases, protein phosphatases; ROS, reactive oxygen species. Modified from Mattson and Magnus (117).

Protection of Neurons Against Oxidative Stress by Three Behaviors that Reduce the Risk of AD

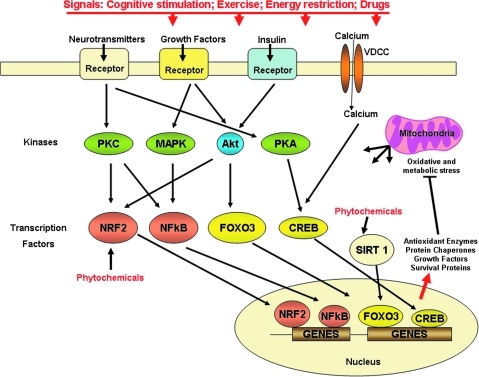

In this section we describe the now considerable evidence that the risk of AD can be reduced by three behaviors that activate ACSRP (cognitive stimulation, exercise, and dietary energy restriction). In the following section we then present evidence that these three behaviors exert their beneficial effects, at least in part, by protecting neurons against oxidative stress (Figs. 3 and 4).

FIG. 3.

Adaptive stress response pathways that may be compromised in AD. The increased synaptic activity in nerve cell networks involved in cognition engages several signal transduction pathways that ultimately lead to the production of proteins that protect neurons against oxidative and metabolic stress. Mental and physical exercise and dietary energy restriction are three examples of AD risk-reducing behaviors that activate neurotransmitter (e.g., glutamate, serotonin, and norepinephrine), growth factor (e.g., brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF], nerve growth factor, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor), and hormone (e.g., insulin, GLP-1, and ghrelin) receptors. Cognitive stimulation, exercise, and dietary energy restriction all increase activity in neuronal circuits, resulting in the activation of neurotransmitter (particularly glutamate) receptors, calcium influx, and production of growth factors. Specific kinases and transcription factors are activated that mediate adaptive cellular stress responses. The transcription factors induce expression of genes encoding, for example, antioxidant enzymes, protein chaperones, neurotrophic factors, and cell survival proteins. Certain phytochemicals may stimulate one or more adaptive cellular stress response pathways, either directly by interacting with kinases or transcription factors, or indirectly by inducing oxidative and/or metabolic stress. Modified from Mattson and Cheng (114). For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars.

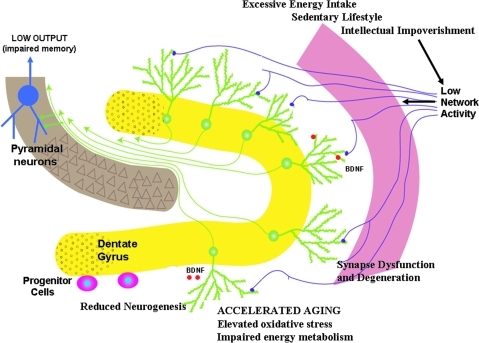

FIG. 4.

Adverse consequences of lifestyles that disengage adaptive cellular stress responses in the hippocampus. A continuous positive energy balance resulting from overeating and physical underactivity, and a cognitively impoverished lifestyle all result in relatively low levels of integrated input to the hippocampus. As a result of suboptimal levels of activation of adaptive neuronal stress response pathways, network activity, there is reduced production of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF and fibroblast growth factor 2, protein chaperones, and antioxidants. Neurons are thereby rendered vulnerable to aging and metabolic stress resulting in oxidative damage, reduced synaptic plasticity, synapse loss, and impaired neurogenesis. Modified from Lazarov et al., 2010 (94). For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars.

Human studies

In 1988 Katzman et al. observed that some subjects failed to develop dementia despite postmortem evidence of advanced AD pathology and suggested that this phenomenon may be due to these subjects having a greater reserve in both brain mass and neuronal number (84). The idea of brain or cognitive reserve has since expanded to refer to the ability of as yet unknown genetic factors and/or increased brain use during early and midlife to afford neuroprotection in the face of aging and neurodegenerative disease. At the cellular level there is evidence for greater numbers of neurons and synapses in individuals deemed to have a high cognitive reserve (53, 127, 163). Various epidemiological studies have shown that individuals with higher levels of education can tolerate more AD brain pathology without the corresponding levels of dementia seen in individuals with less education (12, 13, 52, 136). Studies have also shown a reduced risk of dementia in patients with high job complexity or with a cognitively active lifestyle (164). Increased mental activity has been shown to be correlated with a reduced incidence of AD (174) and reduced age-associated hippocampal atrophy (164). Also, mental training has been shown to positively influence cognition longitudinally (162). Some studies even suggest that having an active social life can be protective against AD (52) and that the risk of AD doubles in lonely individuals (173). Taken together, the data suggest that cognitive reserve can be increased, but that to do so requires considerable effort, at least for those not inclined to exercise or challenge their mind.

In recent years it has become evident that like mental exercise, physical exercise is important for healthy brain function. There have been a variety of studies in humans that have shown that physical activity can benefit brain health (137). Fitness training has been shown to increase performance on cognitive tasks in older individuals (33). Exercise has also been associated with reduced cognitive impairment over a 2-year span in elderly individuals (47). Regular exercise is associated with a delay in the onset of dementia and AD (93, 140) and a reduced risk of developing AD (99). In particular, it was found that AD patients tend to be less active during midlife than healthy controls, suggesting that low activity level in midlife could be a risk factor for AD (54). While exercise intensities vary among individuals and from study to study, it was reported that a regular walking routine in elderly men was associated with a reduced risk of dementia (1). Colcombe et al. showed that both gray and white matter increased in healthy older adults as a function of fitness level, but the same correlation was not seen in younger subjects (34). Also, cardiorespiratory fitness was shown to be positively correlated with medial temporal cortex volume in AD patients, but not in healthy controls, suggesting that cardiorespiratory fitness may modify AD-related brain atrophy (75). Most of the studies on fitness and cognition look at leisure time activities, but one study showed that work-related physical activity alone was not protective against dementia or AD later in life (141).

In addition to keeping physically active there is evidence that maintaining a healthy body weight can also benefit cognition. Studies have shown that increased body mass index (BMI) is associated with a decrease in cognitive performance in healthy individuals (63) and that long-term adult obesity is associated with lower cognition scores (143). Gunstad et al. observed that whole brain and gray matter volumes were reduced in obese individuals compared with normal or moderately overweight controls (62). One complication of relating BMI or body fat levels to cognition is that many overweight subjects also have diabetes, which has been shown to adversely affect cognition. Several studies have shown that the risk of dementia and AD is increased in individuals with diabetes (5, 20, 131). Even impairment in glucose regulation that leads to borderline diabetes has been shown to increase the risk of dementia and AD regardless of the future progression to diabetes proper (177). The most effective intervention for both diabetes and obesity is dietary energy restriction. It was reported that individuals with relatively low caloric intakes are at reduced risk for AD (104) and adherence to a Mediterranean diet has been associated with a lower risk for mild cognitive impairment and AD (144).

Animal studies

The usual housing conditions for laboratory mice and rats result in animals with relatively little cognitive reserve as they age; the animals are overfed, sedentary, and cognitively unchallenged (105). This is readily apparent by the results of studies in which the animals are fed less, exercise, and/or are maintained in enriched environments. Environmental enrichment (EE) paradigms vary, but usually involve housing the animals in large cages with a variety of objects to explore and increased opportunities for social interactions (166). In the late 1940s Hebb documented behavioral differences between rats kept at his home compared with rats kept in the laboratory, and since then a number of studies have established behavioral, anatomical, and molecular changes in rodents following EE (166). The changes seen include improved performance in learning and memory tasks, increased brain mass, enhanced neurogenesis, and changes in dendrite numbers (166). Studies looking at older dogs have shown that when fed a diet high in antioxidants and exposed to EE, the dogs exhibit enhanced cognitive performance, less oxidative protein damage, and high endogenous antioxidant activity than either treatment alone (35a). Enrichment alone was able to improve cognition in older dogs compared with nonenriched controls.

EE has also been studied in transgenic models of AD (6, 14, 35, 40, 80). Several investigators have reported reductions in Aβ levels (6) and amyloid deposits (95) in transgenic AD mouse models after EE, whereas one study reported an increase in amyloid burden (81). Learning and memory was improved after EE in single-mutant APPswe and PS1 mice, whereas double-mutant APPswe/PS1 mice had a more limited improvement (81). Both cognitive function improvements and decreases in neuropathology have been seen in mice that are exposed to an enriched environment at a young age; this is seen in PS1/DAPP mice (35), AD11 mice (14), and PS1 and PS2 KO mice (40). APPswe mice placed in EE at a later age (16 months) showed improvements in cognitive function compared with home cage controls, but without a decrease in Aβ levels (10). Similar findings were reported for APP23 mice that started EE at 10 weeks of age and showed improved water maze performance but stable Aβ levels (175). These results suggest at least two different effects of EE on AD pathogenesis, a reduction Aβ accumulation when EE is initiated early in life, and improvement of cognitive function when EE is started before or after Aβ pathology has already developed.

EE has also been shown to improve neurogenesis in AD mouse models and boost hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) (76). Herring et al. found that after cognitive stimulation there was an increase in the number of newborn and mature hippocampal neurons and in molecules associated with plasticity in a mouse model of AD. The levels of neurogenesis in AD mice raised in an enriched environment were comparable to those of nontransgenic control mice (71). Changes in oxidative stress have also been reported after EE, with decreases in ROS and markers of oxidative damage, and increases in antioxidant defense mechanisms (72).

In an alternative form of cognitive stimulation, Billings et al. used serial trainings of 3xTgAD mice in the water maze mice and obtained improvements similar to those achieved with EE. Improved memory performance was seen in these mice compared with control animals that were allowed to swim without learning a platform location, but like the EE studies training had to be initiated early, before overt pathology developed (21).

One of the complications of EE is that many paradigms involve the addition of running wheels. Some studies have looked at EE compared with running alone and saw no enhancement of spatial learning or neurogenesis with running alone (175). Others have looked at different combinations of social, physical, and cognitive stimulation and found that physical and social interaction were alone not enough to protect against cognitive decline in APP mutant transgenic mice (36). On the contrary, it has been shown in young C57BL/6 females that neurogenesis, as measured by BrdU incorporation, induced by running alone was equivalent to that in mice exposed to EE with access to a running wheel (167).

Comparing exercise and enrichment in young C57BL/6 female mice, Harburger et al. showed that only exercise improved spatial memory in young mice, whereas both exercise and enrichment improved memory in middle-aged or old mice (68). Other studies have shown an increase in neurogenesis after 3 but not 1 h of running (74). The actual number of new cells born was positively correlated with the distance run among mice (135), but there were no significant correlations between the amount of running and a variety of behaviors, including emotionality, exploratory activity, sensory-motor processing, and spatial memory, suggesting that, at least within the limits of this study, running does not have major effects on the behavior of young mice (132). In young C57BL/6 mice, 7–10 days' running was enough to enhance LTP expression (169). Long-term running for 94 weeks in male rats reduced oxidation levels of DNA and lipids in the cerebellum; reduction of lipid oxidation was seen as early as 3 months of running and correlated with forelimb grip strength (37). Radak et al. observed similar findings, increased memory, decreased protein carbonyls, and increased proteasome complex activity in the brains of middle-age rats that were allowed to swim for an hour a day, 5 days a week for 9 weeks (134).

Exercise has also been shown to be beneficial to mouse models of AD (3, 124–126). In old Tg2576 mice, access to a running wheel for 13 weeks improved memory to levels similar to nontransgenic animals (125). Other studies found that as little as 3 weeks' running in 15–19-month-old Tg2576 mice, a time point where significant AD pathology has begun, was able to improve spatial learning (129) and decrease level soluble forms of A beta (126). One month of running in young TgCRNDA mice resulted in decreased proteolytic fragments of APP and after 5 months decreased Aβ plaques in cortex and hippocampus (3). The benefits seen with exercise appear to be greater with voluntary exercise compared with forced exercise. While both forced and voluntary running in Tg2576 mice result in larger hippocampal volumes, only voluntary runners show an increase in memory function and a decreased in Aβ plaques (183).

In addition to physical and mental activity, body weight and energy intake have been shown to be correlated with health and life-span (105, 106). Young rats on a high-caloric diet for 6 weeks gained weight and exhibited learning and memory deficits (82). Diets with high saturated fat content impaired cognitive function in a delayed alternation task in young rats, and the percent of saturated fat in the diet correlated positively with behavioral impairment (61). Murray et al. showed that only 9 days of a high-fat diet was sufficient to cause physical impairment on a treadmill and cognitive impairment in the water maze (121). When 16-month-old rats were fed diets high in fat and cholesterol they made more errors in a test of working memory especially when memory loads were high, and they also showed altered hippocampal morphology (60). Similar studies of mice showed that high-fat diets worsen performance in learning and memory tests (49, 181). There is some evidence that the effects of obesity on neuroplasticity and cognitive function differ in males and females. After 4 weeks on a high-fat diet, hippocampal neurogenesis was impaired in male but not female rats (98). Obese male mice, but not obese female mice, showed memory deficits and impaired level of LTP and long-term depression (77). Evidence is emerging that the weight of the pregnant dam can increase dentate gyrus lipid peroxidation and impair neurogenesis in her offspring (160). Rats that were kept on a high-fat diet after being born to dams on high-fat diets had increased susceptibility to memory impairment and increase oxidative stress compared with rats that were either kept on a high-fat diet after being birthed by a dam on a normal diet, or rats kept on a normal fat diet after being birthed by a dam on a high fat (171).

The impact of energy intake on the brain is further appreciated when one considers the results of studies in which animals are maintained on reduced energy diets, affected either by limited daily feeding/caloric restriction (CR) or intermittent fasting (IF)/alternate day fasting (106). When the daily energy intake of mice was reduced by 20%, their performance on a learning and memory task was improved (69). IF for 6–8 months in mice resulted in enhanced learning and synaptic efficiency, which was associated with increased expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex (51). CR in rats prevents age-related cognitive decline in old but not young rats, and maintains levels of N-methyl-D-aspartate and alpha-amino-5-methyl-3-hydroxy-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors in the hippocampus, which otherwise decrease during aging (2, 148). On the other hand, CR lasting 7–24 months in rats was reported to increase longevity but had a negative impact on cognition (180). In the 3xTgAD mouse model of AD, IF and CR beginning at 5 months of age and lasting for 1 year improved water maze performance and exploratory behavior compared with mice fed AL (67). Mice on CR had lower levels of Aβ1-40, Aβ1-42, and phospho-tau in the hippocampus compared with mice on AL or IF diets (67).

One common complication of excess energy intake is diabetes, which itself has been shown to affect cognition adversely. Diabetic rats have been shown to have impaired spatial learning and LTP (18, 19). Treatment of the diabetic rats with insulin after cognitive decline was not able to ameliorate the deficits (19). Insulin-resistant rats also demonstrate reduced spine density in the hippocampus, reduced LTP, impaired spatial learning, and a reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis (151, 154). In the APP/PS1 mouse model of AD, insulin resistance can be induced by adding 10% sucrose to the drinking water, mimicking type II diabetes. Compared with control transgenic mice fed normal water the insulin-resistant group developed greater memory impairment and increases in Aβ deposition (26). In the Tg2576 mouse model of AD, diet-induced insulin resistance resulted in increase Aβ plaque formation and a decrease insulin receptor signaling (73).

Molecular Mechanisms of Adaptive Responses to Oxidative Stress

We believe and have proposed previously that cognitive stimulation, exercise, and dietary energy restriction promote neuronal survival and plasticity by activating adaptive cellular stress responses in neurons (105, 110). When neurons are engaged in cognitive processes or in controlling body movements, their electrical and synaptic activity results in Na+ and Ca2+ influx, and an increased energy demand. This ionic and energetic stress also results in increased production of ROS, including mitochondrial and extramitochondrial superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric oxide (115). Similar events occur in many neurons during exercise and when dietary energy intake is low. Normally, neurons respond to this mild stress adaptively, as indicated at the molecular level by their upregulation of expression of genes encoding neurotrophic factors such as BDNF and FGF2, protein chaperones such as HSP70 and GRP78, and antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1 (11). The mechanisms by which these cellular defenses are mobilized are beginning to be understood and are described below (Fig. 3).

Several signal transduction pathways have been implicated in the mechanisms by which neurons respond adaptively to mental and physical exercise, and dietary energy restriction. The transcription factors CREB, NF-κB, and Nrf2 are activated in response to vigorous synaptic activity, and by energetic and oxidative stress (100, 149, 168). CREB is activated by Ca2+ and then induces expression of several neuroprotective proteins, among which BDNF has been the most heavily studied with regards to roles in the adaptive responses of neurons to cognitive stimulation, exercise, and energy restriction (118).

Neurotrophic factors and the battle against oxidative stress: BDNF as a prototype

BDNF plays pivotal roles in synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis, and can protect neurons against excitotoxic, oxidative, and metabolic stress (32, 150). BDNF has been shown to increase the production of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase 1 (116) and the membrane-associated antioxidant protein Bcl-2 (23, 145). BDNF was originally identified as a neurotrophin that plays key roles in development of the nervous system, and has since been shown that BDNF and the high affinity BDNF receptor trkB are widely expressed in neurons throughout the brain and spinal cord (158). BDNF levels have been shown to be increase upon LTP induction (28) and BDNF promotes changes at dendritic spine structure (157). Suppression of BDNF production can block dendritic structural changes (157), and mice lacking BDNF in their forebrain neurons exhibit impaired LTP (89, 90) and learning and memory (59). Administration of exogenous BDNF to knockout hippocampal slices abrogated LTP impairment (130). Thus, there is strong evidence to implicate BDNF as an important mediator of synaptic plasticity.

BDNF has also been implicated to play a role in the age-related changes in brain morphology and memory decline. In some human studies BDNF levels in serum (188) or plasma (103) exhibited a negative correlation with age. An analysis of plasma BDNF levels in 496 middle-aged and elderly subjects from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging demonstrated a negative correlation between plasma BDNF levels and age in both males and females (56). The latter study further demonstrated that plasma BDNF levels are positively associated with risk factors for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, independently of age. Studies of the brain have shown that levels of BDNF (133) and its receptor TrkB (138) decrease over the lifespan. Although there have been some inconsistent results, most studies in animals have demonstrated similar decreases in BDNF and TrkB with age, and have also shown that decreased brain BDNF levels are correlated with impaired memory and decreased dendritic spine density in hippocampal neurons (157). Thus, reduced BDNF levels in the brain render neurons vulnerable to dysfunction and degeneration, whereas the functions of BDNF in the blood are unknown. In AD, BDNF and TrkB levels are reduced in several areas of the brain, even at preclinical stages of AD (157), although at least one study reported an increase in BDNF levels in the hippocampus of AD patients (45). BDNF levels in the APP23 transgenic mouse model of AD are dissimilar to human studies, whereas hippocampal BDNF levels are lower in APP23 mice, levels in the frontal cortex are elevated (70), and in cortex and striatum increases were age-dependent (146). Because neuronal death does not occur in the latter mouse models of AD, it is possible that the increased BDNF levels may protect the neurons against Aβ; BDNF can indeed protect neurons against Aβ toxicity in experimental models (9).

In conjunction with increased memory performance and neurogenesis, EE has been shown to increase in hippocampal BDNF levels in both mice (186) and rats (79). In BDNF heterozygote mice with reduced levels of BDNF, the effectiveness of EE in inducing neurogenesis is reduced (139), and the BDNF+/− mice also exhibit reduced dendritic spine density in CA1 and dentate gyrus neurons compared with wild-type mice (185). In the APP23 mouse model of AD, improvements in water maze performance and hippocampal neurogenesis from EE are accompanied by increased hippocampal expression of BDNF (175). The data described above confirm the necessity of BDNF for the synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis induced by EE.

Exercise is beneficial for brain health in humans (165). In one study serum BDNF levels were elevated in response to exercise and the BDNF levels were positively correlated with cognitive performance (50). Voluntary running has also been shown to increase levels of BDNF in the hippocampus of rats (122). Increased BDNF levels in rats after exercise were also associated with increases in memory performance and increases in proteins involved in energy metabolism such as AMP-activated protein kinase, insulin-like growth factor 1, and ghrelin (57). These increases were prevented when BDNF was blocked during exercise. In mice there were positive correlations between BDNF, CREB, and learning rates after exercise (170). In the same study it was found that inhibition of BDNF during running prevents the enhanced memory function associated with running. Other studies in mice have shown that BDNF levels are increased in the hippocampus within 3 weeks of voluntary exercise and levels remain high up to 2 weeks after the end of the exercise period (15). BDNF levels did not return to baseline until after 3–4 weeks after the running period, and the performance in the radial arm maze was best when performed 1 week after the end of running. The SynRas transgenic mouse with permanently activated Ras is expressed under the neuronal synapsin I promoter and has been shown to have decreased neurogenesis and impaired short-term memory (92). When these mice were allowed to run, they showed increased basal BDNF levels comparable to running wild-type animals and also an amelioration of both neurogenesis and short-term memory deficits (92). In the same study the authors looked at TrkB and doublecortin costaining and found that TrkB staining occurred in immature proliferative cells and those with complex dendritic arbors, suggesting that BDNF can act on newly born neurons at multiple stages (92). In diabetic db/db mice, increased BDNF levels from running were accompanied by increase dendritic spine density in dentate granule neurons (153). In the NSE/APPsw mouse model of AD, after 16 weeks of voluntary running, increased brain BDNF levels were complemented by a decrease in Aβ42 peptide and decreased markers of apoptosis (161).

Emerging evidence has suggested that BDNF may regulate energy balance. Human studies have shown that serum BDNF levels are increased in obese women and decreased in women with anorexia nervosa compared with healthy individuals (119). Epidemiological evidence suggests that polymorphisms in BDNF may affect weight; the Val66Met BDNF polymorphism is associated with a lower BMI in healthy subject compared with healthy individuals with alternate polymorphisms (64). Mice with reduced BDNF levels (BDNF+/− mice) exhibit increased food intake, insulin resistance/diabetes, and obesity (43, 87). The metabolic abnormalities of BDNF+/− mice can be reversed with intraventricular infusion of BDNF in the brain and by dietary energy restriction (43, 87). BDNF+/− mice also display impaired hippocampal neurogenesis, which can be partially restored by dietary energy restriction (97). Diets high in saturated fat have been shown to decrease BDNF levels and impair cognitive function, and administration of the antioxidant Vitamin E in conjunction with the high-fat diet was able to restore levels of BDNF and CREB activity, and also reversed cognitive impairment, suggesting that oxidative stress mediates the adverse effects of a high-fat diet on BDNF signaling and cognitive function (176).

BDNF has also been shown to help regulate glucose metabolism in mouse models of diabetes. Subcutaneous administration of BDNF in db/db mice was able to decrease blood glucose and body weight; these changes remained for weeks after BDNF treatment, suggesting the induction of physiological changes (159). Subcutaneous administration of BDNF when started early (4 weeks) was able to prevent the age-related increases in blood glucose levels seen in db/db mice (179). Others have shown that intracerebroventricular administration of BDNF can lower glucose levels and increase insulin concentrations in the pancreas in db/db mice, suggesting the CNS had a role in glucose metabolism (128). CR in db/db mice increases hippocampal BDNF levels and is associated with increased dendritic spine density (153). Taken together, the data suggest that the cognitive impairment observed in diabetes may be a result of dysregulation of glucose metabolism due to decreased BDNF levels.

Protein Chaperones, Antioxidants, and Adaptive Cellular Stress Responses

As their name implies, a major function of protein chaperones is to bind to other proteins and protect them from being exposed to adverse factors, including oxidative stress. The prototypical protein chaperone is HSP70, which has been shown to be upregulated in neurons in response to a range of insults, including cerebral ischemia and epileptic seizures (22). Failure of protein chaperone-mediated neuroprotection is implicated in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson's disease, AD, and Huntington's disease (Fig. 2). Both dietary energy restriction and 2-deoxyglucose administration were reported to upregulate the expression of GRP78 and HSP70 and protect dopaminergic neurons against the toxicity of chemical inhibitors of mitochondrial complex I (44). Multiple protein chaperones, including HSPs 70, 40, and 90, can protect neurons against polyglutamine-induced degeneration in models relevant to Huntington's disease (55).

It was reported that the protein co-chaperone BAG2 forms a complex with HSP70, which then binds insoluble/hyperphosphorylated tau and delivers it to the proteasome for degradation (27). Others have demonstrated a role for HSP90 in the degradation of phosphorylated tau (38). HSP70 and HSP90 can inhibit the aggregation of Aβ1-42 in vitro (48), suggesting a potential role for these protein chaperones in protecting brain cells against AD by preventing the aggregation and neurotoxicity of Aβ. It was reported that addition of HSP90, HSP70, and HSP32 to the culture medium induces the production of interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor, and increases the phagocytosis and clearance of Aβ, by microglia (83). Impaired chaperone function and consequent proteotoxicity may play a role in the selective vulnerability of neurons in different brain regions in AD. As evidence, the levels of immunostaining for HSP72 and proteasomal subunits are weaker in neurons in brain regions affected in AD (4).

Not only does expression of HSPs increase in muscle after exercise (58, 120), but increased expression also occurs in neurons in response to exercise (31) and dietary energy restriction (11, 182). In an animal model of heat stroke-induced hyperthermia, 3 weeks of exercise induced HSP72 expression in the brain and protected neurons against damage and also increased the survival of the animals (31). Alternate day fasting for several weeks to months results in the upregulation of HSP70 and HSP40 in hippocampal pyramidal neurons in mice and rats, and protects those neurons against excitotoxic death in experimental models of severe epileptic seizures (24, 147). A moderate level of pharmacologically induced energetic stress has also been shown to upregulate protein chaperones and protect neurons against oxidative and excitotoxic injury. For example, treatment of hippocampal neurons with 2-deoxyglucose, a form of glucose that inhibits glycolysis, results in increased expression of HSP70 and GRP78, and protects the neurons from being killed by oxidative (Fe2+) and excitotoxic (glutamate) insults (96). Similarly, exposure of hippocampal neurons to iodoacetate, an inhibitor of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, induces expression of HSP70, HSP90, and the antioxidant protein Bcl-2, and protects the neurons against oxidative injury (66).

Mitochondrial Neurohormesis

Mitochondria produce a major portion of free radicals generated in nerve cells; during oxidative phosphorylation, superoxide anion radical is produced. SOD within mitochondria (SOD2) and in the cytosol (SOD1) convert superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (111). Hydrogen peroxide can be converted to water by the activities of catalase and glutathione peroxidase; however, in the presence of Fe2+ or Cu+, the hydrogen peroxide is converted to hydroxyl radical. Hydroxyl radical can be very damaging to proteins and nucleic acids, and to membranes in which it attacks double bonds in fatty acids to initiate a chain reaction called lipid peroxidation. Another chemical pathway that induces oxidative damage involves Ca2+-induced activation of nitric oxide synthase resulting in the production of nitric oxide, a free radical. Nitric oxide can, in turn, interact with superoxide to generate peroxynitrite, which damages proteins by causing the nitration of tyrosine residues; peroxynitrite can also induce membrane lipid peroxidation. Increased levels of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite have been suggested to contribute to the excessive oxidative damage to proteins, nucleic acids, and membranes documented in studies of postmortem tissue from AD patients, and in experimental models of AD (142, 155). SOD2 can protect neurons against insults relevant to AD, including Aβ, Fe2+, and nitric oxide-generating agents (86).

In addition to SOD2, mitochondria contain several proteins that help protect neurons against oxidative damage. One class of such proteins are the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs), which are integral membrane proteins in the mitochondrial inner membrane that provide a conduit for leakage of protons across the membrane thereby reducing oxidative phosphorylation and the production of superoxide. Recent studies have shown that overexpression of UCP4 (101) and UCP2 (109) can protect neurons against oxidative insults relevant to AD, including glycolytic inhibitors and mitochondrial toxins. UCP4 was also shown to stabilize cellular and mitochondrial calcium homeostasis, which was associated with reduced levels of mitochondrial ROS and increased resistance of neural cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress (30). Neuronal UCPs can be activated by free fatty acids and oxidative stress, and UCPs may regulate cellular calcium homeostasis, free radical production and mitochondrial biogenesis (8). The latter article reviews additional findings further suggest roles for UCPs in synaptic plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders.

Environmental factors that protect the brain against cognitive impairment and AD have been shown to increase expression SOD2 and UCPs. For example, both exercise and CR have shown to increase levels of UCPs in the brain (39, 101).

Experimental reduction in SOD2 levels in a transgenic mouse model of AD resulted in an acceleration of the development of Aβ pathology and cognitive deficits (46). The function of SOD2 may be impaired in AD because it was shown that Aβ can induce the nitration of SOD2 in APP/PS1 double-mutant AD mouse model (7). When mice with AD-like pathology were maintained in an enriched environment, the amount of oxidative stress associated with the Aβ pathology was significantly reduced, a result that was apparently due to the upregulation of antioxidant defenses, including SOD1 and SOD2, in the brain cells (72).

In our study called atlas of gene expression in mouse aging project, male and female mice that had been maintained on either an ad libitum diet or a 40% CR diet beginning at 6 weeks of age were killed at 6, 16, and 24 months of age, and expression of nearly 17,000 genes was determined in 16 different tissues (178, 184). Our analyses of the CNS revealed that aging is associated with downregulation of genes encoding proteins involved in DNA repair, protein degradation, and inhibitory neurotransmission, and that CR counteracts these effects of aging (178). In another study we performed a gene array analysis of the hippocampus in male and female rats that had been maintained for 6 months on either ad libitum (control), 20% CR, 40% CR, IF, or high fat/high glucose diets. The CR diets significantly increased the size of the hippocampus of females, but not males, and this gender difference was associated with specific changes in hippocampal gene expression (107). The 20% CR diet downregulated genes involved in mitochondrial energy production in males, while upregulating these metabolic pathways in females. The 40% CR diet upregulated genes involved in glycolysis, protein deacetylation, PGC-1α, and mTor pathways in both sexes. Genes involved in energy metabolism, oxidative stress responses, and cell survival were affected by the high-energy diet in both males and females. Collectively, these findings suggest that aging results in dysregulation of mitochondrial energy and oxyradical metabolism resulting in reduced energy availability and increased ROS production and oxidative damage.

Exercise may protect the brain against AD by stimulating ACSRP. To elucidate the mechanisms by which exercise may benefit the brain during aging, we trained 16-month-old mice that had either run regularly during their adult life or led a sedentary lifestyle in the hippocampus-dependent water maze (152). We then analyzed expression of 24,000 genes in the hippocampus and found that runners show greater activation of genes associated with synaptic plasticity and mitochondrial function, and also exhibit significant downregulation of genes associated with oxidative stress and lipid metabolism. These results suggest that the enhancement of cognitive function by lifelong exercise is associated with preservation of mitochondrial function and suppression of oxidative stress.

Therapeutic Implications

While research on neuronal plasticity, aging, and AD is ever-expanding, a pharmacological cure for dementia is not imminent. The present mini-review of the current literature does, however, offer approaches that could be beneficial in preventing or delaying the onset of dementia. In line with the hormesis ideology—“what doesn't kill you makes you stronger”—upregulation of adaptive stress responses in cells via cognitive stimulation, exercise, and dietary restriction better prepare the brain for oxidative insults resulting from aging and disease (93, 110, 140, 164). On the other hand, lifestyles that include social isolation, low activity levels, and obesity may hasten the onset of cognitive impairment and AD (54, 63, 173). Upregulation of specific proteins that enhance neurogenesis and promote cell survival may be key modulators of the adaptive stress response. Data suggest that these molecular pathways may be impaired in certain disease states, including AD.

Activation of adaptive stress responses in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases have been able to provide benefits in cognition and motor function, and suggest that these molecular pathways maybe able to be activated through cognitive stimulation, exercise, and CR (41, 42, 67, 76, 108, 125). One of the key factors that may help protect against the decline of cognitive function in aging and disease is BDNF. Experiments have shown that increasing levels of BDNF either by exogenous administration or via cognitive stimulation, exercise, and CR can help enhance neurogenesis and promote cognitive function (9, 158, 179). Moreover, it may be possible to induce BDNF production with pharmacological agents as exemplified by the most widely used and efficacious antidepressants such as fluoxetine, seratraline, and paroxetine, which upregulate BDNF expression and preserve neuronal function in animal models of AD (123) and Huntington's disease (41, 44a, 61a). Further research will expand our understanding of how adaptive stress responses can modulate synaptic plasticity and improve cognitive decline with aging and disease, and how to tap into these pathways to suppress oxidative damage and protect the brain against AD.

Abbreviations Used

- Aβ

amyloid β-peptide

- ACSRP

adaptive cellular stress response pathways

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AICD

intracellular amyloid precursor protein domain

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BMI

body mass index

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- CR

caloric restriction

- CREB

cyclic AMP response element binding protein

- EE

environmental enrichment

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- GRP78

glucose-regulated protein 78

- HD

Huntington's disease

- HSP70

heat-shock protein 70

- Htt

huntingtin

- IF

intermittent fasting

- IP3R

IP3 receptor

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MAOS

membrane-associated oxidative stress

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PPases

protein phosphatases

- PS1

presenilin-1

- PtdS

phosphatidylserine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SERCA

smooth endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- UCP

uncoupling protein

- VDCC

voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

References

- 1.Abbott RD. White LR. Ross GW. Masaki KH. Curb JD. Petrovitch H. Walking and dementia in physically capable elderly men. JAMA. 2004;292:1447–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams MM. Shi L. Linville MC, et al. Caloric restriction and age affect synaptic proteins in hippocampal CA3 and spatial learning ability. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adlard PA. Perreau VM. Pop V. Cotman CW. Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4217–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adori C. Kovács GG. Low P. Molnár K. Gorbea C. Fellinger E. Budka H. Mayer RJ. László L. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in Creutzfeldt-Jakob and Alzheimer disease: intracellular redistribution of components correlates with neuronal vulnerability. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akomolafe A. Beiser A. Meigs JB, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of developing Alzheimer disease: results from the Framingham study. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1551–1555. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambree O. Leimer U. Herring A, et al. Reduction of amyloid antipathy and abeta plaque burden after enriched housing in TgCRND8 mice: involvement of multiple pathways. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:544–552. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anantharaman M. Tangpong J. Keller JN. Murphy MP. Markesbery WR. Kiningham KK. St. Clair DK. Beta-amyloid mediated nitration of manganese superoxide dismutase: implication for oxidative stress in a APPNLH/NLH X PS-1P264L/P264L double knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1608–1618. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews ZB. Diano S. Horvath TL. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins in the CNS: in support of function and survival. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:829–840. doi: 10.1038/nrn1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arancibia S. Silhol M. Mouliere F, et al. Protective effect of BDNF against beta-amyloid induced neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo in rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arendash GW. Garcia MF. Costa DA. Cracchiolo JR. Wefes IM. Potter H. Environmental enrichment improves cognition in aged Alzheimer's transgenic mice despite stable beta-amyloid deposition. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1751–1754. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000137183.68847.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arumugam TV. Phillips TM. Cheng A. Morrell CH. Mattson MP. Wan R. Age and energy intake interact to modify cell stress pathways and stroke outcome. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:41–52. doi: 10.1002/ana.21798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett DA. Schneider JA. Wilson RS. Bienias JL. Arnold SE. Education modifies the association of amyloid but not tangles with cognitive function. Neurology. 2005;65:953–955. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176286.17192.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett DA. Wilson RS. Schneider JA, et al. Education modifies the relation of AD pathology to level of cognitive function in older persons. Neurology. 2003;60:1909–1915. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000069923.64550.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berardi N. Braschi C. Capsoni S. Cattaneo A. Maffei L. Environmental enrichment delays the onset of memory deficits and reduces neuropathological hallmarks in a mouse model of Alzheimer-like neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:359–370. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berchtold NC. Castello N. Cotman CW. Exercise and time-dependent benefits to learning and memory. Neuroscience. 2010;167:588–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bezprozvanny I. Mattson MP. Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bharadwaj PR. Dubey AK. Masters CL. Martins RN. Macreadie IG. Abeta aggregation and possible implications in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:412–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biessels GJ. Kamal A. Ramakers GM, et al. Place learning and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes. 1996;45:1259–1266. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.9.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biessels GJ. Kamal A. Urban IJ. Spruijt BM. Erkelens DW. Gispen WH. Water maze learning and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in streptozotocin-diabetic rats: effects of insulin treatment. Brain Res. 1998;800:125–135. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biessels GJ. Staekenborg S. Brunner E. Brayne C. Scheltens P. Risk of dementia in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:64–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billings LM. Green KN. McGaugh JL. LaFerla FM. Learning decreases A beta*56 and tau pathology and ameliorates behavioral decline in 3xTg-AD mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:751–761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4800-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown IR. Heat shock proteins and protection of the nervous system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:147–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruce-Keller AJ. Begley JG. Fu W. Butterfield DA. Bredesen DE. Hutchins JB. Hensley K. Mattson MP. Bcl-2 protects isolated plasma and mitochondrial membranes against lipid peroxidation induced by hydrogen peroxide and amyloid beta-peptide. J Neurochem. 1998;70:31–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruce-Keller AJ. Umberger G. McFall R. Mattson MP. Food restriction reduces brain damage and improves behavioral outcome following excitotoxic and metabolic insults. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butterfield DA. Reed T. Newman SF. Sultana R. Roles of amyloid beta-peptide-associated oxidative stress and brain protein modifications in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:658–677. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao D. Lu H. Lewis TL. Li L. Intake of sucrose-sweetened water induces insulin resistance and exacerbates memory deficits and amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36275–36282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrettiero DC. Hernandez I. Neveu P. Papagiannakopoulos T. Kosik KS. The cochaperone BAG2 sweeps paired helical filament-insoluble tau from the microtubule. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2151–2161. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4660-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castren E. Pitkanen M. Sirvio J, et al. The induction of LTP increases BDNF and NGF mRNA but decreases NT-3 mRNA in the dentate gyrus. Neuroreport. 1993;4:895–898. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cecarini V. Ding Q. Keller JN. Oxidative inactivation of the proteasome in Alzheimer's disease. Free Radic Res. 2007;41:673–680. doi: 10.1080/10715760701286159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan SL. Liu D. Kyriazis GA. Bagsiyao P. Ouyang X. Mattson MP. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein-4 regulates calcium homeostasis and sensitivity to store depletion-induced apoptosis in neural cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37391–37403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen YW. Chen SH. Chou W. Lo YM. Hung CH. Lin MT. Exercise pretraining protects against cerebral ischaemia induced by heat stroke in rats. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:597–602. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng B. Mattson MP. NT-3 and BDNF protect CNS neurons against metabolic/excitotoxic insults. Brain Res. 1994;640:56–67. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91857-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colcombe S. Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:125–130. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colcombe SJ. Erickson KI. Scalf PE. Kim JS. Prakash R. McAuley E. Elavsky S. Marquez DX. Hu L. Kramer AF. Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1166–1170. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.11.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costa DA. Cracchiolo JR. Bachstetter AD, et al. Enrichment improves cognition in AD mice by amyloid-related and unrelated mechanisms. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Cotman CW. Head E. The canine (dog) model of human aging and disease: dietary, environmental and immunotherapy approaches. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:685–707. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cracchiolo JR. Mori T. Nazian SJ. Tan J. Potter H. Arendash GW. Enhanced cognitive activity—over and above social or physical activity—is required to protect Alzheimer's mice against cognitive impairment, reduce abeta deposition, and increase synaptic immunoreactivity. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;88:277–294. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui L. Hofer T. Rani A. Leeuwenburgh C. Foster TC. Comparison of lifelong and late life exercise on oxidative stress in the cerebellum. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:903–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickey CA. Kamal A. Lundgren K. Klosak N. Bailey RM. Dunmore J. Ash P. Shoraka S. Zlatkovic J. Eckman CB. Patterson C. Dickson DW. Nahman NS., Jr. Hutton M. Burrows F. Petrucelli L. The high-affinity HSP90-CHIP complex recognizes and selectively degrades phosphorylated tau client proteins. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:648–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI29715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dietrich MO. Andrews ZB. Horvath TL. Exercise-induced synaptogenesis in the hippocampus is dependent on UCP2-regulated mitochondrial adaptation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10766–10771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2744-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong S. Li C. Wu P. Tsien JZ. Hu Y. Environment enrichment rescues the neurodegenerative phenotypes in presenilins-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:101–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duan W. Guo Z. Jiang H. Ladenheim B. Xu X. Cadet JL. Mattson MP. Paroxetine retards disease onset and progression in Huntingtin mutant mice. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:590–594. doi: 10.1002/ana.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan W. Guo Z. Jiang H. Ware M. Li XJ. Mattson MP. Dietary restriction normalizes glucose metabolism and BDNF levels, slows disease progression, and increases survival in huntingtin mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2911–2916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan W. Guo Z. Jiang H. Ware M. Mattson MP. Reversal of behavioral and metabolic abnormalities, and insulin resistance syndrome, by dietary restriction in mice deficient in brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2446–2453. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duan W. Mattson MP. Dietary restriction and 2-deoxyglucose administration improve behavioral outcome and reduce degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:195–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990715)57:2<195::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44a.Duan W. Peng Q. Masuda N. Ford E. Tryggestad E. Ladenheim B. Zhao M. Cadet JL. Wong J. Ross CA. Sertraline slows disease progression and increases neurogenesis in N171-82Q mouse model of Huntington's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durany N. Michel T. Kurt J. Cruz-Sanchez FF. Cervos-Navarro J. Riederer P. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 levels in Alzheimer's disease brains. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:807–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esposito L. Raber J. Kekonius L. Yan F. Yu GQ. Bien-Ly N. Puoliväli J. Scearce-Levie K. Masliah E. Mucke L. Reduction in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase modulates Alzheimer's disease-like pathology and accelerates the onset of behavioral changes in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5167–5179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0482-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Etgen T. Sander D. Huntgeburth U. Poppert H. Forstl H. Bickel H. Physical activity and incident cognitive impairment in elderly persons: the INVADE study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:186–193. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans CG. Wisén S. Gestwicki JE. Heat shock proteins 70 and 90 inhibit early stages of amyloid beta-(1–42) aggregation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33182–33191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farr SA. Yamada KA. Butterfield DA, et al. Obesity and hypertriglyceridemia produce cognitive impairment. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2628–2636. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferris LT. Williams JS. Shen CL. The effect of acute exercise on serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels and cognitive function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:728–734. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802f04c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fontan-Lozano A. Saez-Cassanelli JL. Inda MC, et al. Caloric restriction increases learning consolidation and facilitates synaptic plasticity through mechanisms dependent on NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10185–10195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2757-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fratiglioni L. Paillard-Borg S. Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:343–353. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fratiglioni L. Wang HX. Brain reserve hypothesis in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;12:11–22. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friedland RP. Fritsch T. Smyth KA, et al. Patients with Alzheimer's disease have reduced activities in midlife compared with healthy control-group members. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3440–3445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061002998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fujikake N. Nagai Y. Popiel HA. Okamoto Y. Yamaguchi M. Toda T. Heat shock transcription factor 1-activating compounds suppress polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration through induction of multiple molecular chaperones. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26188–26197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710521200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golden E. Emiliano A. Maudsley S. Windham BG. Carlson OD. Egan JM. Driscoll I. Ferrucci L. Martin B. Mattson MP. Circulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor and indices of metabolic and cardiovascular health: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gomez-Pinilla F. Vaynman S. Ying Z. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor functions as a metabotrophin to mediate the effects of exercise on cognition. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:2278–2287. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez B. Hernando R. Manso R. Stress proteins of 70 kDa in chronically exercised skeletal muscle. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:42–49. doi: 10.1007/s004249900234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gorski JA. Balogh SA. Wehner JM. Jones KR. Learning deficits in forebrain-restricted brain-derived neurotrophic factor mutant mice. Neuroscience. 2003;121:341–354. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Granholm AC. Bimonte-Nelson HA. Moore AB. Nelson ME. Freeman LR. Sambamurti K. Effects of a saturated fat and high cholesterol diet on memory and hippocampal morphology in the middle-aged rat. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;14:133–145. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-14202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenwood CE. Winocur G. Cognitive impairment in rats fed high-fat diets: a specific effect of saturated fatty-acid intake. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:451–459. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61a.Grote HE. Bull ND. Howard ML. van Dellen A. Blakemore C. Bartlett PF. Hannan AJ. Cognitive disorders and neurogenesis deficits in Huntington's disease mice are rescued by fluoxetine. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2081–2088. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gunstad J. Paul RH. Cohen RA, et al. Relationship between body mass index and brain volume in healthy adults. Int J Neurosci. 2008;118:1582–1593. doi: 10.1080/00207450701392282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gunstad J. Paul RH. Cohen RA. Tate DF. Spitznagel MB. Gordon E. Elevated body mass index is associated with executive dysfunction in otherwise healthy adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gunstad J. Schofield P. Paul RH, et al. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism is associated with body mass index in healthy adults. Neuropsychobiology. 2006;53:153–156. doi: 10.1159/000093341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo Q. Sebastian L. Sopher BL. Miller MW. Glazner GW. Ware CB. Martin GM. Mattson MP. Neurotrophic factors [activity-dependent neurotrophic factor (ADNF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)] interrupt excitotoxic neurodegenerative cascades promoted by a PS1 mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4125–4130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo Z. Lee J. Lane M. Mattson M. Iodoacetate protects hippocampal neurons against excitotoxic and oxidative injury: involvement of heat-shock proteins and Bcl-2. J Neurochem. 2001;79:361–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Halagappa VK. Guo Z. Pearson M, et al. Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction ameliorate age-related behavioral deficits in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harburger LL. Nzerem CK. Frick KM. Single enrichment variables differentially reduce age-related memory decline in female mice. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:679–688. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hashimoto T. Watanabe S. Chronic food restriction enhances memory in mice—analysis with matched drive levels. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1129–1133. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200507130-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hellweg R. Lohmann P. Huber R. Kuhl A. Riepe MW. Spatial navigation in complex and radial mazes in APP23 animals and neurotrophin signaling as a biological marker of early impairment. Learn Mem. 2006;13:63–71. doi: 10.1101/lm.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Herring A. Ambree O. Tomm M, et al. Environmental enrichment enhances cellular plasticity in transgenic mice with Alzheimer-like pathology. Exp Neurol. 2009;216:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herring A. Blome M. Ambree O. Sachser N. Paulus W. Keyvani K. Reduction of cerebral oxidative stress following environmental enrichment in mice with Alzheimer-like pathology. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:166–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ho L. Qin W. Pompl PN, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance promotes amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2004;18:902–904. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0978fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holmes MM. Galea LA. Mistlberger RE. Kempermann G. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and voluntary running activity: circadian and dose-dependent effects. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:216–222. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Honea RA. Thomas GP. Harsha A, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and preserved medial temporal lobe volume in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:188–197. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819cb8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu YS. Xu P. Pigino G. Brady ST. Larson J. Lazarov O. Complex environment experience rescues impaired neurogenesis, enhances synaptic plasticity, and attenuates neuropathology in familial Alzheimer's disease-linked APPswe/PS1{delta}E9 mice. FASEB J. 2010;24:1667–1681. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hwang LL. Wang CH. Li TL, et al. Sex differences in high-fat diet-induced obesity, metabolic alterations and learning, and synaptic plasticity deficits in mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:463–469. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hyun DH. Emerson SS. Jo DG. Mattson MP. de Cabo R. Calorie restriction up-regulates the plasma membrane redox system in brain cells and suppresses oxidative stress during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19908–19912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608008103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ickes BR. Pham TM. Sanders LA. Albeck DS. Mohammed AH. Granholm AC. Long-term environmental enrichment leads to regional increases in neurotrophin levels in rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2000;164:45–52. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jankowsky JL. Melnikova T. Fadale DJ, et al. Environmental enrichment mitigates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5217–5224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5080-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jankowsky JL. Xu G. Fromholt D. Gonzales V. Borchelt DR. Environmental enrichment exacerbates amyloid plaque formation in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1220–1227. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.12.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jurdak N. Lichtenstein AH. Kanarek RB. Diet-induced obesity and spatial cognition in young male rats. Nutr Neurosci. 2008;11:48–54. doi: 10.1179/147683008X301333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kakimura J. Kitamura Y. Takata K. Umeki M. Suzuki S. Shibagaki K. Taniguchi T. Nomura Y. Gebicke-Haerter PJ. Smith MA. Perry G. Shimohama S. Microglial activation and amyloid-beta clearance induced by exogenous heat-shock proteins. FASEB J. 2002;16:601–603. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0530fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Katzman R. Terry R. DeTeresa R, et al. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: a subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:138–144. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Keller JN. Hanni KB. Markesbery WR. Impaired proteasome function in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2000;75:436–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keller JN. Kindy MS. Holtsberg FW. St. Clair DK. Yen HC. Germeyer A. Steiner SM. Bruce-Keller AJ. Hutchins JB. Mattson MP. Mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase prevents neural apoptosis and reduces ischemic brain injury: suppression of peroxynitrite production, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 1998;18:687–697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00687.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kernie SG. Liebl DJ. Parada LF. BDNF regulates eating behavior and locomotor activity in mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:1290–1300. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koren J., 3rd Jinwal UK. Lee DC. Jones JR. Shults CL. Johnson AG. Anderson LJ. Dickey CA. Chaperone signalling complexes in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:619–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Korte M. Carroll P. Wolf E. Brem G. Thoenen H. Bonhoeffer T. Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8856–8860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]