Abstract

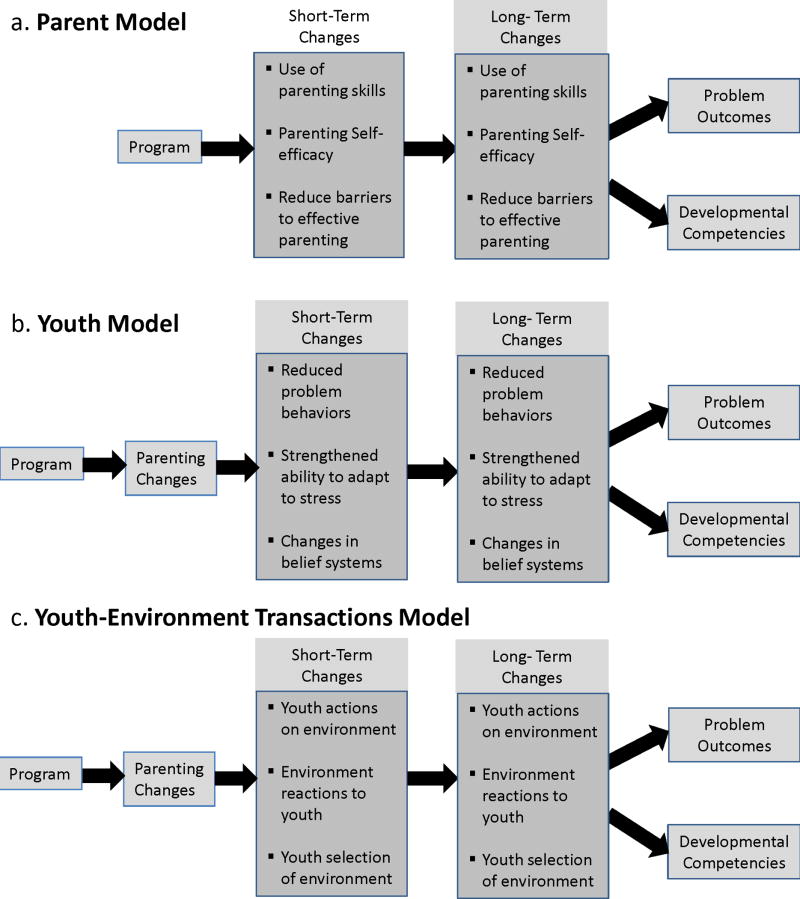

This chapter reviews findings from 46 randomized experimental trials of preventive parenting interventions. The findings of these trials provide evidence of effects to prevent a wide range of problem outcomes and to promote competencies from one to twenty years later. However, there is a paucity of evidence concerning the processes that account for program effects. Three alternative pathways are proposed as a framework for future research on the long-term effects of preventive parenting programs; 1) through program effects on parenting skills, perceptions of parental efficacy and reduction in barriers to effective parenting; 2) through program-induced reductions in short-term problems of youth that persist over time, improvements in youth adaptation to stress, and improvements in youth belief systems concerning the self and their relationships with others; and 3) through effects on contexts in which youth become involved and on youth-environment transactions.

Keywords: Parenting, prevention, promotion, mediation, long-term effects

Introduction

This review addresses two issues concerning the effects of preventive parenting programs. What are the long-term effects of such programs on child outcomes? What processes account for these long-term effects? The review goes beyond prior reviews of the efficacy of parenting interventions (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle et al., 2008; Taylor & Biglan, 1998) in three ways. First, it focuses exclusively on long-term outcomes, defined as those assessed one year or longer after the program. Second, it focuses on a broad array of outcomes across developmental periods, including promoting competencies as well as preventing problem outcomes. Third, because of the focus on prevention and health promotion, the review only includes programs for families of youth who were not selected on the basis of experiencing clinical problems at program entry. This review does not provide a quantitative summary of the effect sizes of interventions. Rather, it describes the range of parenting interventions that have been employed across developmental levels, provides a summary of the research on long-term program effects and of mediating processes that account for program effects and provides a conceptual framework of alternative pathways that may mediate long-term effects to guide future research.

The review addresses a critical, but somewhat neglected question: What are the pathways by which parenting interventions bring about long-term change in youth outcomes? Understanding the pathways through which parenting programs have long-term effects draws on theory from normal development and developmental psychopathology, and has implications both for advancing theory and for enhancing the long-term effects of future programs. Prevention scientists and developmental researchers have recognized the scientific opportunity of integrating theoretical and intervention research (Cicchetti & Hinshaw, 2002; Rutter, Pickles, Murray & Eaves, 2001). For example, Cicchetti and Hinshaw (2002) proposed that “preventive intervention research can be conceptualized as true experiments in modifying the course of development, thereby providing insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of disordered outcomes” (pp. 667–668). Similarly, Collins et al. (2000) articulated research designs that address recent critiques of the causal effect of parenting on child socialization, particularly as compared with the alternative causal explanations, such as genetic or peer influences. They proposed that studies that demonstrated that a program led to a change in parenting, which in turn was associated with a subsequent change in youth outcomes, provide particularly strong evidence for the causal effect of parenting.

Preventive intervention researchers have in a complementary fashion proposed that well-specified theoretical models of developmental processes provide the foundation on which effective preventive interventions are built (Coie, et al., 1993; Mrazeck & Haggerty, 1994). In the prevention research cycle (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994), a “small theory” is specified concerning the putative mediating processes that lead to the problems to be prevented and a preventive intervention is designed to change these putative mediators and thus prevent the problems. A recent report on prevention from the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (NRC/IOM, 2009) extended this model to mental health promotion in which theoretical models about the development of competencies “inform the development of interventions to promote mental, emotional and behavioral health” (pp. 110). Randomized prevention trials provide experimental tests of whether changing these processes accounts for reductions in problem outcomes and increases in competencies, which in turn should lead to the design of more effective and efficient interventions.

Below, we define some key constructs used in the review and present a conceptual framework of alternative theoretical pathways through which parenting interventions might lead to long-term effects on youth outcomes. We then review findings of the effects of randomized experimental trials with a minimum of one year follow-up. The studies are discussed by developmental level during which the intervention was delivered. Studies that focus on families in stressful situations and include youth in more than one developmental level are discussed in the final section. We then discuss those studies that formally test parenting as a mediator of program effects on long-term outcomes. Finally, using our conceptual framework, we describe directions for future research.

Defining key constructs

Parenting interventions

We defined parenting interventions as those in which at least one component of the intervention involved activities designed to promote some aspect of effective parenting. Because most problem outcomes are associated with multiple risk and protective factors, many interventions that included a parenting component also included one or more other components designed to change other potential mediators (e.g. children’s coping skills) or to reduce barriers to using effective parenting (e.g., parental depression, economic strain).

Effective parenting

We defined parenting to include a broad range of functions that parents engage in to promote their offspring’s accomplishment of culturally and age appropriate developmental tasks and to reduce problem behaviors. These functions include having a positive affective relationship with the child, providing advice and information, being aware of the youth’s activities and interactions, supporting behaviors that promote effective adaptation (e.g., homework), and discouraging behaviors that hinder positive adaptation (e.g., association with deviant peers). Effective parent-child relationships are most often characterized as ones that include high levels of nurturance, use of effective control strategies and supporting children in accomplishing normative developmental tasks (e.g., Bornstein, 2002; Collins, Madsen, & Susman-Stillman, 2002). However, there are differences across researchers about which aspect of parenting is most responsible for affecting youth developmental outcomes, with some researchers emphasizing attachment and self-regulatory capabilities (Dozier, Albus, Fisher, & Sepulveda, 2002), some emphasizing positive exchanges (Zisser & Eyberg, 2010), and others emphasizing a coercive reinforcement cycle (Patterson & Fisher, 2002).

Given that the critical developmental tasks change over time, the content of effective parenting differs across developmental stage. Further, effective parenting involves facilitating children’s ability to meet the demands of social contexts beyond the family, including the school environment and peer relationships, and to avoid potentially dangerous and high risk situations, so that the characteristics of effective parenting and the difficulty of being an effective parent differ across the social contexts in which families live (e.g., Mason, Cauce, Gonzales and Hiraga, 1996). The effects of parenting may also differ as a function of biological differences in children, including genetic risk for development of problem outcomes (e.g., Edwards et al., 2009; Kaufman et al., 2004; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006).

Youth outcomes

We use the term problem outcomes to refer to the problems that have been targeted by prevention programs such as mental health problems, substance use and abuse, high-risk sexual behavior and delinquency. There is also a growing focus on promotion interventions designed to increase positive outcomes. A recent report on the state of prevention research defined mental health promotion as “efforts to enhance individuals’ ability to achieve developmentally appropriate tasks (developmental competence), increase a sense of self-esteem, mastery, well-being, and social inclusion, and strengthen their ability to cope with adversity” (pp. 74). We will use the term competencies to refer to the positive outcomes targeted by promotion programs.

Conceptual framework of the processes that account for the long-term effects of parenting interventions

Our conceptualization of the processes that might account for the long-term effects of parenting interventions will be guided by two complementary propositions. The first is that intervention-induced improvements in parenting are causally related to youth competencies and problem outcomes. The second is that the long-term effects of program-induced changes in parenting are due to social, cognitive, behavioral and biological processes that occur in parents, youth, and the transactions between youth and their social contexts.

Proposition 1: Intervention-induced improvements in parenting are causally related to the development of youth competencies and problem outcomes

Similar to other researchers, we use the term “cause” (e.g., Kraemer et al., 1997) to denote that experimentally induced changes in parenting lead to improvements in youth outcomes. This is the central hypothesis of the “small theory” that underlies parenting interventions. However, as noted above, researchers have challenged inferences concerning causal relations between parenting and youth outcomes that are based on correlational studies, and have proposed randomized intervention trials as a way to disentangle the effects of parenting from alternative explanations (Collins et al., 2000; Rutter et al., 2001). Several steps have been proposed in the design of these trials (Patterson & Fisher, 2002). First, the theoretical processes should be specified a priori in which the intervention effects on youth outcomes are mediated through their effects on parenting. Second, both parenting and youth outcomes should be measured with reliable and valid measures that are sensitive to change. Third, the intervention should improve both parenting and the youth outcomes. Fourth, experimentally-induced changes in parenting must be shown to mediate (or account for) the changes in youth outcomes. Although there are limitations on the causal mediation inferences that can be drawn based on the findings of randomized trials (MacKinnon, 2008), these trials have the distinct methodological advantage of ruling out rival explanations such as shared pre-existing third variables including genetic factors.

Proposition 2: The long-term effects of intervention-induced changes in parenting are due to changes in social, cognitive, behavioral, and biological processes in parents, youth and in the transactions between youth and their social contexts

Although mediational analyses provide evidence that changes in parenting are involved in improving youth outcomes, they do not identify the processes through which parenting interventions affect child outcomes over time. Theoretically, these processes may involve program-induced changes within parents, youth, and in the transactions between youth and their environment, and research is needed to test which of these alternative pathways account for intervention effects.

Changes in parents

The most parsimonious change in parents that may account for long-term effects of parenting programs is that parents learned new skills through participating in the program and use of these skills is maintained by positive responses from children. A second, related change in parents that may maintain positive parenting and lead to improvements in youth outcomes over time involves parenting self-efficacy. Parenting self-efficacy refers to parents’ beliefs in their ability to influence their children in ways that foster their development and success (Ardelt & Eccles, 2001). Theoretically, a higher sense of parental self-efficacy leads parents to be more persistent in the use of parenting skills that are associated with desirable outcomes. Although the causal nature of the relations between parental self-efficacy and parenting behaviors is not established, several researchers have found that higher levels of parental self-efficacy are associated with more effective parenting and lower child mental health problems (e.g., Jones & Prinz, 2005). It is also possible that reduction of barriers to effective parenting, (e.g., parental depression [e.g., Brennan, Le Brocque, & Hammen, 2003]) enables parents to implement and maintain the skills they learned in the programs.

Changes in youth

One explanation of the long-term effects of parenting programs on youth outcomes is that improvements in parenting cause short-term changes in youth behavior and these changes persist over time. For example, externalizing problems are stable from early childhood to adolescence (Loeber & Hay, 1997), so that intervention-induced reductions in externalizing problems that occur at early stages of development are maintained in subsequent developmental stages.

Program-induced changes in parenting may also affect youth’s cognitive, biological, or affective processes involved in adapting to stress. For example, there is considerable research indicating that parental support and consistent discipline are associated with children’s emotion regulation skills, such as active coping, social support seeking, attentional control and cognitive reappraisal (Eisenberg, Spinrad & Eggum, in press), which in turn are related to mental health and physical health outcomes in childhood (Eisenberg, Spinrad & Eggum, in press) and adulthood (Luecken, Kraft, et al., 2009). Biological processes underlying emotion regulation, such as HPA axis functioning, also may be affected by parenting and influence the development of youth internalizing and externalizing problems (Blair, et al., 2008).

Changes in parenting may also lead to improved youth outcomes through their effects on youth belief systems, such as beliefs in self-worth, control beliefs and beliefs concerning the parent-child relationship. For example, parental warmth and contingent responses to youth are related to youth beliefs in their ability to control their environment (Bandura, 1997). Beliefs about the parent-child relationship may be particularly important in explaining the long-term effects of parenting interventions. Rosenberg and McCullough (1981) defined the construct of “mattering” as the belief that one is noticed, is an object of concern and needed by significant others. Research has demonstrated that children’s belief that they matter to their parents is related to their internalizing and externalizing problems (e.g., Schenck et al., 2009). The related construct of fear of abandonment refers to children’s beliefs that their parents may not want to or be able to take care of them in the future. Research has found that fear of abandonment mediates the relation between mother-child relationship quality and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems (Wolchik et al., 2002) in a sample of children following parental divorce.

Changes in youth-environment transactions

Parenting interventions may lead to long-term effects on youth outcomes by influencing the environmental contexts in which youth become involved or youth transactions within these contexts. Caspi et al. (1989) used the concept of interactional continuity to refer to the process in which parenting affects child behaviors during one developmental stage, which in turn affect the responses they receive from others in different social contexts, (e.g., schools and peer groups), and these responses maintain the changes in behavior. For example, parenting involving ineffective contingencies for child non-compliance can lead to increases in the child’s aggressive and non-compliant behavior, which in turn leads to more aversive behavior on the part of the parent (Patterson & Fisher, 2002). Children who are aggressive and non-compliant may experience rejection by peers and teachers in the school context, leading them do more poorly in this context (Patterson & Fisher, 2002). Similarly, Masten et al. (2005) referred to “cascading pathways” in which change in one area of functioning trigger a progression of consequences that can have extensive effects on other areas of adaptation in later developmental periods.

The concept of “cumulative continuity” (Caspi et al., 1989) refers to the process by which youth select into contexts that reinforce their behavior. Kaplan (1983) proposed that adolescents who are devalued in groups that hold conventional values find esteem and value in their relationships in deviant groups and engage in antisocial behavior or drug use behaviors that are valued by these groups. Longitudinal research has shown that adolescents with conduct disorder or depression as compared to those who do not have such problems are likely to spend less time in conventional contexts and have greater exposure to contexts that maintain their problem behaviors into young adulthood (e.g., Bardone, Moffitt, Caspi, & Dickson, 1996).

Review of experimental trials of programs to promote effective parenting

We identified 46 randomized experimental trials of parenting interventions that met the following three criteria: 1. Participants were randomly assigned to a program that included an intervention component to promote effective parenting versus a comparison condition; 2. There was a minimum of one-year follow-up during which there was no intervention; and 3. The trial could be considered a universal, selective or indicated prevention or promotion intervention (NRC/IOM, 2009).

Many of these programs focused on helping parents to facilitate their offspring’s accomplishment of developmental tasks. Thus, we organized our review by developmental period, infancy and toddlerhood (0 – 3), early childhood (4–7), middle childhood (8–12) and adolescence (13–18). Several programs that focused primarily on helping families deal with stressful situations and targeted children across developmental periods are described separately. In each section, we first describe the role of effective parenting in promoting accomplishing the tasks for healthy adaptation. We then describe the interventions including the population that was targeted, the goals and objectives of the interventions, the program components and the formats used in the interventions. We then summarize the findings concerning outcomes achieved by the interventions, with an emphasis on long-term youth outcomes. Finally, we more fully describe one intervention and its’ long-term impact.

Infancy and toddlerhood

Interventions that target parenting during the prenatal period, infancy, or toddlerhood teach parents to support their infant in achieving the developmental tasks of healthy physical development, early cognitive development, and behavior and emotional regulation. The first three years of life are a time of great physical growth and development, and during this time, parents play a key role in providing appropriate care and nutrition, and ensuring their infant’s safety. Abuse, neglect, or accidents are a leading cause of death for infants and toddlers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau, 2009), making parent education about basic childcare tasks, developmental milestones, and ways to create a safe home environment crucial to promoting healthy development. Infancy and toddlerhood are also marked by the development of functional language, cognitive skills such as representational thinking, and basic self-regulation skills such as following rules, focusing attention and appropriately expressing emotion (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000). The development of each of these skills creates demands on the parent, including engaging in warm and supportive social interactions, cognitively stimulating the infant, and supporting their understanding of their environment (Bornstein, 2002).

The 13 experimental trials that met our criteria involved mothers who were pregnant or parents whose offspring were 3 years old or younger. The majority of programs targeted families who were low-income or were experiencing another risk factor, such as being a single teenage mother (e.g. Olds, Robinson et al., 2004). Half of the programs included primarily ethnic minority families (e.g., Olds, Kitzman, et al., 2004). Over half of the interventions included a component consisting of home visitation by nurses or professionals (e.g., Brooks-Gunn et al., 1994), with a majority of these interventions beginning in pregnancy. Other formats included multi-level interventions with self-directed components, individual family appointments with practitioners and parenting groups. Most of these programs were designed to educate parents about child development and teach parenting behaviors that promote healthy development and home safety. One-third of the programs also included child-based components, such as educationally-enriched daycare or socio-emotional training. Comparison conditions were typically no-intervention conditions, brief (one- to three-session) interventions, or screening and referring families to community resources.

Three quarters of the studies reported improvements in parenting skills within one year after the intervention ended, including increases in positive parenting and responsiveness (Sanders, Markie-Dadds, Tully & Bor, 2000), reductions in coercive or corporal discipline, increases in effective discipline (Gross et al., 2003), increases in the safety of the home environment (Kitzman et al., 1997; Olds et al., 1994) and reductions in the incidence of child abuse and neglect (Kitzman et al., 1997; Olds et al., 1994; Olds, Robinson et al, 2004), Researchers also reported program effects on factors that might influence positive parenting, including increases in parenting self-efficacy, parenting satisfaction, positive affect (Gross et al., 2003; Plant & Sanders, 2007), parenting competence (Sanders, et al., 2000), and reductions in parenting stress (Cowan, Cowan, Pruett, & Pruett, 2007) and inter-parental conflict or domestic violence (Olds, 2002; Sanders, et al., 2000). Approximately one-third of the studies reported long-term program effects on parenting including increased father involvement 18 months later (Cowan, Cowan, Pruett, Pruett, & Wong, 2009), higher levels of maternal sensitivity two years later (Olds, Robinson, et al., 2004), parenting competence and positive affect three years later (Sanders, Bor & Morawska et al., 2007), as well as reduced rates of child abuse between two and 13 years later (Olds, Kitzman, et al., 2007). In addition, studies reported long-term effects on factors that affect parenting, such as fewer subsequent pregnancies, higher maternal employment, less maternal involvement with the law, longer romantic relationships (Olds et al., 1997; Olds, Kitzman, et al., 2007), and improvements in parental adjustment (Sanders et al., 2007).

A majority of the studies reported program effects to reduce child behavior problems between one and two years after the intervention ended (e.g., Gross et al., 2003; Sanders, et al., 2000). Other effects included fewer child injuries or ingestions of hazardous substances (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2003), improved cognitive and emotional behaviors (Johnson & Breckenridge, 1982) higher executive functioning (as evidenced by the ability to sustain attention, inhibit motor control, and display less overly-sensitive emotional behavior), more advanced language skills, and greater social competence (Olds, Kitzman et al., 2004; Olds, Robinson et al., 2004) for those in the intervention versus control condition. Several follow-ups in early childhood found program effects to improve child behavior at home and in the classroom one year later (Gross et al., 2003; Plant & Sanders, 2007) and to reduce the incidence of diagnosis of externalizing disorders (Gross et al., 2009; Sanders, et al., 2000; Sanders et al, 2007). Two studies that followed their samples from infancy to adolescence found reduced risk behaviors, such as involvement in the legal system and risky sexual behavior (Olds et al., 1997), and greater language and math skills (McCormick et al., 2006) in the intervention than control condition.

The Nurse Family Partnership is a home-visiting intervention for first-time mothers that has been tested in three large-scale randomized trials. Nurses visited mothers at home during pregnancy and/or during the first two years of the child’s life to provide education about healthy prenatal behaviors, competent early child-care, and strategies to improve the maternal life-course, such as planning future pregnancies and seeking education and employment. In the first trial all first-time pregnant women in the area were invited to participate in the study. Women were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: screening and referral only; screening/referral and free transportation to childcare; screening/referral with free transportation to childcare and home visits by a nurse during pregnancy; or all of the former services plus home-visits by a nurse until the child was two years old (Olds, Henderson, & Kitzman, 1994). When the children were 4 years old, nurse-visited mothers were found to have lower rates of abuse and neglect, and home environments that were safer and more supportive of child learning than mothers who were not visited (Olds, Henderson, & Kitzman, 1994). Children born to nurse-visited mothers who smoked during pregnancy had less of a decline in IQ by age four than control children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy (Olds, Henderson, & Tatelbaum, 1994). Follow-up assessments showed that adolescents whose mothers were visited by nurses during pregnancy and/or infancy were less likely to have been abused, neglected or arrested, to use drugs or alcohol regularly, or to participate in risky sexual behavior than those in the other conditions (Olds, Henderson, Cole, et al., 1998). Program effects were stronger for youth born to low-income, unmarried teenage mothers. At age 19, daughters of low-income mothers who were visited by nurses had fewer arrests and convictions, less Medicaid use, and fewer children themselves (Eckenrode et al., 2010) than those in the other conditions. A second trial recruited primarily low-income African American first-time mothers who were mostly adolescent and unmarried and assigned them to receive prenatal nurse home-visits, post-natal nurse home visits for two years, or no nurse visits (Olds, Kitzman et al, 2004). Four years later when the children were six years old, nurse-visited mothers had fewer subsequent births, longer romantic relationships, and less reliance on welfare than the mothers in the control conditions. Children whose mothers were in the nurse-visited condition had a greater ability to mentally process information and provide coherent stories in response to stems, had higher receptive vocabulary and fewer behavior problems in the borderline or clinical range at age six (Olds, Kitzman et al., 2004). When the children were nine years old, those in the nurse-visited condition had higher GPAs and achievement test scores in math and reading than those in the control conditions (Olds, Kitzman, et al., 2007). A third trial compared the effects of home visits by paraprofessionals to home visits by nurses. When the children were four years old, nurse-visited mothers were more sensitive, provided safer and more learning-supportive home environments and were involved in less domestic violence than the mothers visited by paraprofessionals (Olds, Robinson et al., 2004). Further, their children showed a greater ability to sustain attention, inhibit motor control and adapt their behavior and control their emotions during behavioral tasks, and used more advanced language than children whose mothers were visited by paraprofessionals (Olds, Robinson, et al., 2004).

Early childhood

The acquisition of self-regulation skills, such as paying attention, appropriately expressing emotions, planning, and problem solving and developing social competencies, such as joint play with peers and perspective taking are developmental task of early childhood, ages four through seven (NRC/IOM, 2000). Critical developmental tasks include adapting successfully to school and developing non-aggressive relations with peers (Hinshaw, 1992). Children who have difficulty regulating their behavior or who are aggressive toward others are at elevated risk for a wide range of problems throughout childhood and into adulthood, including academic failure, conduct disorder, delinquency and criminality, and substance abuse (Broidy, et al., 2003; Fergusson, Horwood, 1998). A common theme of interventions during early childhood is the promotion of parenting practices that decrease aggression and facilitate healthy transition into school.

We identified eight experimental trials for parents of children ages four through seven that met our criteria. One of these interventions was universal and was designed to promote a healthy transition to kindergarten (Cowan, Cowan, & Heming, 2005); several targeted parents in high-risk families (e.g., poor, lived in high crime areas, or had a child who was incarcerated (e.g., Brotman et al., 2008); others targeted children whose parents’ rated them as having high levels of externalizing behavior problems (e.g., August, Realmuto, Hektner & Bloomquist., 2001). Roughly half of these programs included primarily ethnic minority families. The majority of the programs used a group format and many included additional components for parents designed to increase parental involvement in school (e.g., McDonald, et al., 2006), help parents obtain health or family services (August et al., 2001; Tolan, Gorman-smith & Henry, 2004), or help parents manage living in a neighborhood with high levels of violence (Tolan et al., 2004). Some included components for children, such as skills training or academic tutoring (e.g., August, et al., 2001; Bernat, August, Hecktner & Boomquist, 2007). Control conditions typically consisted of no-intervention conditions, brief informational parent sessions, or mailings of printed information on behaviorally oriented parenting skills.

About half of the studies assessed program effects on parenting within one year of completing the program. These studies found that the programs improved aspects of positive parenting such as responsiveness (e.g. Brotman et al., 2008) and warmth (Cowan, Cowan, & Heming, 2005), as well as increased the use of effective discipline strategies (e.g. Bernat et al., 2007; Brotman et al., 2008; Reid, Webster-Stratton & Beauchaine, 2001;Tolan et al., 2004). Several interventions increased parents’ support for a positive transition to school by teaching strategies to support child learning at home (Brotman et al., 2008) or become more involved in school (Reid et al., 2001; Tolan et al., 2004;Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Henry & Schoeny, 2009). About one-third of the studies found that program effects on parenting practices were maintained between one and six years after the program ended (e.g., improved discipline [Brotman et al., 2008], increased parental support of child learning [Brotman et al., 2008], and increased supervision [Tremblay, Pagani-Kurtz, Masse, Vitaro, & Pihl, 1995]). In two thirds of the studies, researchers did not report on long-term program effects on parenting.

Nearly all of the studies found program effects on child outcomes assessed a year or more after the intervention ended. Several studies reported reduced externalizing problems (Bernat et al., 2007; Strayhorn & Weidman, 1991), decreased internalizing problems (e.g., Cowan, Cowan, & Heming, 2005; Strayhorn & Weidman 1991), higher academic achievement and engagement in school (e.g., Cowan, et al., 2005; Tremblay, et al., 1995), and increased social competence (e.g., Brotman et al., 2008). When assessed in middle childhood (two or more years after the intervention), children whose parents received the programs were found to have less externalizing problems (e.g. Tolan et al., 2004; 2009), fewer delinquent behaviors (McCord, Tremblay, Vitaro, & Desmarais-Gervas, 1994), fewer internalizing problems (Cowan, Cowan, & Heming, 2005), and better school adjustment (McDonald et al., 2006; Tolan et al., 2004; 2009) compared to children whose parents were in the control conditions. When assessed in adolescence, youth whose parents received early childhood parenting interventions had fewer behavior problems (Cowan & Cowan, 2006), less substance use (Tremblay et al. 1995), and engaged in less delinquent behavior (Tremblay et al., 1995) than those whose parents were in the control conditions. Several studies found the effects of the programs were greater for high risk families that had high levels of family problems or child behavior problems at program entry (e.g. Reid et al., 2001).

The Incredible Years (IY) program was designed to reduce child behavior problems through parent training, which focused on improving parent competencies, parent involvement in school, and effective management of child behavior problems (Webster-Stratton, 1987). The program also focuses on helping parents support effective behavioral regulation skills and social competencies which are seen as important for preventing the development of child externalizing problems. Although the program has primarily been tested with parents of children whose behavior problems exceeded the clinical threshold, adapted versions of this program have been incorporated in several prevention trials (Bernat et al., 2007; Brotman et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2009).

One of the prevention trials of the IY program included 634 low-income mothers with a child enrolled in a Head Start program (Reid et al., 2001). Mothers were randomly assigned to an 8–12 session parenting program or a no-intervention control condition. One year later, mothers who received the program showed more positive parenting practices, used fewer critical statements and commands, and were more consistent in their interactions with their children, and reported greater parenting competence than those in the control group. Children whose mothers received the program showed fewer behavior problems and more positive behaviors at one-year follow-up as compared to those in the control group. A program for parents with preschoolers (age 4) whose older siblings were incarcerated included an adaption of the IY (Brotman et al., 2008). Families were randomly assigned to the intervention (i.e., 22 parent group sessions, 20 child group sessions, 10 home visits over eight months and three monthly booster sessions) or a no-intervention control condition. Sixteen months after the program ended (one year after the booster sessions), parents in the intervention condition used more responsive parenting and less harsh parenting, and provided more stimulation for learning in interactions with their children than those in the control condition. Children whose parents participated in the intervention had five times fewer aggressive acts than those whose parents were in the control condition.

Middle Childhood

Middle childhood (ages eight to twelve) is marked by growth in cognitive competencies (e.g., problem solving, perspective taking), social relationships, self-concept, self-regulation and social responsibility (Collins et al., 2002). Children in this age range increasingly deal with influences beyond the family such as bullying, violence and peers who use substances. Relative to parenting at earlier ages, effective parenting includes greater effort to have children regulate their own behavior; greater monitoring of children’s behavior; more emphasis on helping children increase goal-directed behaviors, develop a sense of social responsibility, and engage in prosocial behavior; and greater attention to decreasing antisocial behavior (Collins et al., 2000).

We identified 11 trials that met our criteria. The majority of the studies were designed to prevent adolescent substance use and conduct problems or delinquency. The programs included parent components such as parenting groups (e.g., Kosterman, Hawkins, Spoth, Haggerty, & Zhu, 1997), mailed educational materials (e.g., Jackson & Dickinson, 2003), or in-home family visits (e.g., Hostetler & Fisher, 1997). Nearly all of the interventions also included a classroom-based, family-based, or group-based youth component that included education about drugs, tobacco, and alcohol; anger management; social problem solving; or family communication. Some studies found that the child component increased the program effects on child behavior relative to the parent component (Lochman & Wells, 2004; Schinke, Schwinn, DiNoia, & Cole, 2004), but one study found that the addition of a teen group component to the parent group was associated with an iatrogenic effect (Dishion & Andrews, 1995). About one-third of the studies were universal interventions; close to half were selected interventions targeting youth at-risk because of poverty, and one-quarter were indicated interventions that targeted youth with externalizing behavior problems or low grades. Comparison conditions included no-intervention conditions, mailed information on adolescent development or monetary payments to control schools.

Three quarters of the evaluations reported effects on parenting within a year after the intervention was completed, including improvements in family communication (Kosterman, et al., 1997), family problem solving (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005), management of child behavior (Redmond, Spoth, Shin & Lepper, 1999) discipline (Lochman & Wells, 2004), and quality of parent-youth relationships (Dishion & Andrews, 1995; Kosterman, et al., 1997) as well as parent attitudes about youth substance use (Jackson & Dickinson, 2003). Only one study found effects on parenting more than a year after the program ended. This study found that parents who participated in a substance use prevention program as compared to those in the control condition strengthened their norms against substance use across the two years after the program ended (Park et al., 2000).

As assessed one or more years after participation, positive program effects were found on youth delinquency (Eddy, Reid, Stoolmiller, & Fetrow, 2003; Lochman & Wells; 2004), substance use (Dishion, Kavanagh, Schneiger, Nelson, & Kaufman, 2002; Hostetler & Fisher, 1997; Spoth, Reyes, Redmond, & Shin, 1999), and social competence and appropriate behavior at school (Lochman & Wells, 2004). A number of the studies also found program effects in adolescence (from three to seven years after the intervention), including decreases in delinquency, conduct problems, internalizing problems (Mason et al., 2007; Trudeau, Spoth, Randall & Azevedo, 2007), risky sexual behavior (Brody, Kogan, Chen, & Murry, 2008), and substance use (e.g. Connell, Dishion, Yasui, & Kavanagh, 2007; DeGarmo, Eddy, Reid, & Fetrow, 2009); reductions in susceptibility to negative peer influence (Brody et al., 2008; Schinke et al., 2004); and increases in academic success (Spoth, Randall, & Shin, 2008; Stormshak, Connell & Dishion., 2009). Several studies found the intervention effects were greater for youth who were at-risk because of existing behavior problems or family stressors (Brody et al., 2008; Connell & Dishion, 2008), boys (Lochman & Wells, 2004).

The Iowa Strengthening Families Program (ISFP: Molgaard & Spoth, 2001) was designed to prevent substance use and other risky behaviors during the transition to adolescence. The program consists of six separate sessions for parents and children and one joint session for parents and children. One universal trial of sixth graders compared the ISFP and another family intervention (Preparing for the Drug Free Years: Park et al., 2000) to a control group that received materials via mail. One year after the program, parents in the ISFP condition were found to have improved skills to manage child behavior and improved parent-child relationship quality as compared to those in the control condition (Redmond et al., 1999). Six years after the program, adolescence whose parents were in the ISFP condition also initiated substance use later (Spoth, Shin, Guyll, Redmond, & Azevedo, 2006), and had fewer internalizing disorders (Trudeau et al., 2007), greater academic engagement and success (Spoth, Randall, & Shin, 2008) and less delinquent behavior (Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 2000) than those in the control condition.

The ISFP was adapted for rural African American youth and tested with 284 11-year-old rural African American youth and their parents (Brody et al., 2004). The Strong African American Families program (SAAF) was designed to prevent adolescent substance use and early sexual behavior by promoting vigilant parenting, which involves increasing parental involvement in the child’s life, parent-child communication about alcohol and sex, use of inductive and consistent discipline, and parental monitoring. The program also included a component to promote racial socialization of the youth by the parents. At the end of the program, parents in the intervention condition had better adaptive parenting in terms of limit setting, monitoring, inductive discipline, racial socialization, and communication about sex and alcohol than parents in the no-intervention control group. Twenty-nine months later, youth whose families participated in the intervention were less influenced by peers, engaged in less risky sexual behaviors, and showed a decrease in conduct problems over time compared to those in the control group (Brody et al, 2008). A particularly intriguing aspect of the evaluation involved testing a program x gene interaction. The program reduced growth in risky behavior (drug or alcohol use or sexual intercourse) over 29 months for youth who were at genetic risk due to a polymorphism in the HTTLPR gene. Those at genetic risk in the control group had two times the increase in risky behavior compared with those at genetic risk whose families participated in SAAF (Brody, Beach, Philibert, Chen & Murry, 2009).

Adolescence

Adolescence marks a period of sexual and physical maturation, which in turn affects how youth see themselves and are seen by their parents and peers (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Adolescents think more abstractly and hypothetically than they did when in middle childhood, and are developing an increased sense of autonomy and identity. Adolescents are increasingly influenced by peers, and are exposed to more opportunities for risky behavior. Despite the increasing salience of these influences outside the family and the challenges that the adolescent’s physical, social and cognitive changes pose for parents, adolescents continue to be greatly influenced by their parents (for a review see Steinberg & Silk, 2002).

We identified six trials that met our criteria, all of which focused on preventing adolescent substance use or risky sexual behavior by educating parents about such risks and promoting parent-adolescent communication about these topics. The programs included components for parents, such as parent groups (e.g. Villarruel, Cherry, Cabriales, Ronis & Zhou, 2008) or mailed information (Ennett et al., 2001), and components that included teens, such as family sessions (Pantin, et al., 2009) or adolescent group sessions (e.g. Goldberg, et al., 2000). Comparison conditions were no-intervention control groups, self-administered programs, or a combination of existing community programs or English classes for native speakers of languages other than English. Four of the six studies measured program effects on parenting and reported that parents who received an intervention as compared to controls were more likely to discuss drugs, alcohol, tobacco, and sex with their teenagers (Ennett et al., 2001), had better overall communication with their teenagers (Pantin et al., 2009; Villarruel et al., 2008), and reported more positive parenting up to one year following the intervention (Prado et al., 2007). One year after the intervention, teens whose families participated were less likely to drink alcohol, smoke, or participate in unsafe sexual behavior (Pantin et al., 2009), and reported less intention to use illegal drugs (Goldberg et al., 2000) than those whose families did not receive an intervention. Two years later, programs were found to reduce drug use (Prado et al., 2007), decrease favorable attitudes about substance use (Haggerty et al., 2007), increase safe sexual practices (Pantin et al., 2009), and reduce the rate of externalizing disorders (Pantin et al., 2009) relative to the control conditions.

Familias Unidas is an intervention for Hispanic families that targets facilitating parent-adolescent communication and bonding, supporting parental involvement in extra-familial contexts in which adolescents participate, and building supportive relationships between parents to reduce their isolation (Pantin et al., 2003). The program includes parent groups that meet weekly over a nine-month period and home visits focused on implementing the skills taught in the program. The program has been tested with both selected and indicated samples of 8th graders with at least one parent born in a Spanish-speaking country. In the selected trial, families were randomly assigned to the Familias Unidas program combined with an HIV-Prevention program that promoted parent communication about HIV risk, English language classes for Spanish-speaking parents and the HIV prevention program, or language classes plus another health intervention (Prado et al., 2007). Families that participated in Familias Unidas combined with the HIV prevention program showed improvements in positive parenting and parent-adolescent communication at posttest. Adolescents whose parents received this intervention reported less cigarette use compared to those in the other two conditions and less illicit drug use relative to the other health intervention across 24 months following the intervention. Another trial targeted families of 8th graders with adolescents who had high behavior problems as reported by parents (Pantin et al., 2009). The intervention was found to improve positive parenting, parent-teen communication, and parental monitoring at six months after the program relative to the control group that was referred to community services. Youth whose parents participated in the program had less of an increase in substance use approximately two years after the study, had fewer symptoms of externalizing disorders, and were more likely to use condoms than youth whose parents did not receive the intervention (Pantin et al., 2009).

Resilience promotion programs for youth in stressful situations

Seven trials evaluated the effects of parenting interventions with families of children spanning multiple developmental periods who were exposed to stressful situations. Most of these programs were designed to help families facing a specific stressor such as parental divorce or separation (Braver, Griffin, & Cookston, 2005; DeGarmo, Forgatch, & Martinez, 1999; Wolchik et al., 2002;), parental methadone treatment (Catalano, Gainey, Fleming, Haggerty, & Johnson, 1999), parental depression (Beardslee, Gladstone, Wright, & Cooper, 2003), or parental bereavement (Sandler et al., in press). Based on empirical support for parenting as a resilience resource (Luthar, 2006), these programs taught parents to use effective parenting techniques and to deal with stressor-specific issues (e.g., reducing interparental conflict following divorce, Braver et al., 2005; dealing with parental grief following death of a spouse, Sandler et al., in press; dealing with depression of a parent, Beardslee et al., 2003). Several of the programs also included a child-focused coping enhancement component (e.g., Beardslee et al., 2003; Sandler et al., in press; Wolchik et al., 2002). Typical comparison conditions included no-treatment control groups, mailed literature concerning how to adapt to the stressful situation, or a brief lecture only condition. One program targeted school children and adolescents exposed to multiple sources of stress in an economically impoverished community with a high crime rate and high rates of substance abuse (LoSciuto, Freeman, Harrington, Altman, & Lanphear, 1997). The parenting program consisted of monthly parenting classes and home visits to encourage parent participation in other aspects of the multi-component community-focused program (LoSciuto et al., 1997). Evaluations of these programs have shown program effects on multiple aspects of parenting including improvements in the quality of the parent-child relationship, increases in effective discipline (DeGarmo et al., 1999; Sandler et al., 2003; Wolchik et al., 2007) and improvements in family rule-setting (Catalano et al., 1999; Ennett, et al, 2001). Several programs reported that improvements in parenting lasted one year following program completion (e.g., Forgatch et al., 2009). The interventions reduced a wide range of child and adolescent problems between two and nine years after the program, including diagnosed mental disorder (Wolchik et al., 2002), externalizing behavior problems (DeGarmo et al., 1999; Sandler, Ayers et al., in press; Wolchik et al., 2002), police arrests (Forgatch et al., 2009), internalizing problems (Braver et al., 2005; Sandler, Ayers et al., in press; Wolchik et al., 2002; Wolchik et al., 2007), substance use (Wolchik et al., 2002), cortisol dysregulation (Luecken et al, 2009) and grief (Sandler, Ma et al., in press). A few programs reported long-term effects on school performance, self-esteem and active coping (e.g., Sandler, Ayers et al., 2003; in press; Wolchik et al., 2002; 2007).

The New Beginnings Program (NBP, Wolchik et al., 2000; 2002) is an 11-session program designed to improve parenting by the residential mother following divorce. One of the two experimental trials of the NBP compared the NBP to the NBP plus a child coping program and a literature control condition. No significant additive effects were found for the child coping component as compared to the NBP only condition at post-test or short- or long-term follow-ups. At 6-year follow-up, youth whose mothers participated in the NBP had lower rates of meeting criteria of diagnosed mental disorder, fewer internalizing and externalizing problems, less substance use and risky sexual behavior, and higher self-esteem and school grades (Wolchik et al., 2002) than those in the literature control condition, with stronger effects occurring for those who were at higher risk at program entry. The Family Bereavement Program (FBP, Sandler et al., 2003) is a 12-session program that included a caregiver group based on the NBP program, a child coping group, and two individual sessions for the caregivers. At 6-year follow-up, youth in the FBP as compared to those in the literature control condition had lower youth and caregiver report of externalizing disorders, lower externalizing problems, lower internalizing problems, higher self-esteem, lower problematic grief, and less HPA axis dysregulation as assessed by evening cortisol (Luecken et al., 2009; Sandler, Ayers et al., in press; Sandler, Ma et al., in press). Caregivers in the FBP as compared to those in the control condition had lower rates of depression at 6-year follow-up (Sandler, Ayers et al., in press).

Summary

The findings of the 46 randomized trials provide evidence that interventions that include a parenting component led to improvements across a broad range of youth problem outcomes and competencies from one to 20 years following the intervention. The outcomes that have been changed include problems with high individual and societal costs, such as mental disorder, child abuse, substance use, delinquency, risky sexual behaviors and academic difficulties. The parenting components differed across development periods to address differences in the key developmental tasks facing youth, and long-term program effects have been demonstrated for interventions that were delivered during each developmental period. Teasing out the specific effects of the parenting components of these programs is complicated by the fact that 25 of the 46 studies included components in addition to parenting. To date, few researchers have used experimental designs such as sequential dismantling designs that would allow the assessment of the independent effects of the parenting components or the additive effects of other components (West & Aiken, 1997). In several studies researchers have compared the effects of their parenting component to those of other intervention conditions, and have demonstrated the positive contribution of the parenting components (e.g., Bodenmann, Cina, Ledermann, & Sanders, 2008; Cowan, et al., 2007; Prado, et al., 2007) and some have found that adding other components to the parenting component did not yield additional benefits (e.g., Wolchik et al., 2002). Given differences in costs for single versus multiple component programs and the importance of identifying combinations of components with maximal effects, additional research is needed to examine the effects of parenting versus other components.

Twenty studies tested the long-term effects of a parent intervention when used without other components, of which eight found support for long-term effects to strengthen parenting and 13 found support for long-term effects on youth outcomes, such as behavior problems (Sanders et al., 2007; Wolchik et al., 2002), delinquency (Eckenrode, 2010; Forgatch et al., 2009), substance use (Pantin et al., 2009; Wolchik et al., 2002), and academic performance (McDonald et al., 2006; Olds, Kitzman et al., 2006; Wolchik et al., 2002). These findings support the efficacy of parenting interventions to improve long-term outcomes for youth. However, they tell us little about how these programs have their effects, including whether their effects are due to the skills taught in the program or to nonspecific effects of the intervention (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1997).

Integrating Theoretical Propositions About the Long-term Effects of Parenting Interventions into the Analysis of Prevention Trials

In this section, we describe research on the pathways by which these programs have long-term effects on youth outcomes. The discussion is structured along the lines of the two theoretical propositions about factors that account for the long-term effects of parenting programs discussed earlier in the chapter.

Proposition 1: The long-term effects of parenting interventions are due to program effects to improve parenting

This proposition can be tested by mediational analysis in which the program is the exogenous variable, change in parenting is the putative mediator and the analysis tests whether the program effects on parenting account for program effects on the outcomes. Ten of the trials reported analysis of mediation (see Table 1). Nearly half of the studies that included meditational analyses involved interventions that took place during middle childhood, and one quarter were stressor-specific interventions delivered to parents with offspring at multiple developmental stages. The parenting variables that were found to mediate program effects on youth outcomes included parental warmth (Zhou, Sandler, Millsap, Wolchik, & Dawson-McClure 2008), authoritative parenting (Cowan, Cowan, & Hemming, 2005), effective and consistent discipline (Bernat et al., 2007; Lochman & Wells, 2002; Zhou, et al., 2008), parental monitoring (Dishion, Nelson, & Kavanagh, 2003), and good family communication and problem solving (Brody et al., 2008; DeGarmo et al., 2009). Parenting was found to mediate program effects on a variety of youth outcomes, including academic success (Spoth, et al, 2008; Zhou et al., 2008), substance use (Dishion et al., 2003; Pantin et al., 2009; Prado et al., 2007), delinquency (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005; Forgatch et al., 2009), internalizing and externalizing problems (Zhou et al., 2008), and conduct problems (Brody et al., 2008). There is a pattern of findings across studies for parenting to mediate program effects on externalizing problems and/or substance abuse, a complex of problems that has been labeled as “problem behaviors” (Biglan, Brennan, Foster & Holder, 2004).

Table 1.

Mediation analysis of long-term program effects on child problems and competencies

| PROGRAM and SAMPLE | CONDITIONS COMPARED IN MEDIATIONAL MODEL | PROGRAM EFFECTS ON MEDIATOR (S) | MEDIATOR EFFECTS ON OUTCOME (S) | TEST OF MEDIATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Schoolchildren and their Families Project To facilitate child transition to school n = 100 families with child preparing to start kindergarten (mean age = 5) Programs included 16-week couples groups focused either on marital skills (Marital Intervention) or parenting skills Parenting Intervention) compared to control group receiving yearly parent consultation Cowan, Cowan, & Hemming, 2005 (in Cowan & Cowan, Ablow, & Johnson, 2005) |

Marital intervention vs. Control |

Posttest: Reduced mother and father authoritarian parenting Posttest: Reduced father authoritarian parenting 1 yr: Reduced marital conflict 1 yr: Reduced mother and father authoritarian parenting |

1 yr: Mediated effects on children’s perceived academic and social competence 1 yr: Mediated effects on increased child academic achievement (Peabody Individual Achievement Test) 1 yr: Mediated effects on increased teacher-reported academic competence 2 yr: Mediated effects on increased social competence and higher academic achievement |

Tested whether the program affected the mediators and whether the mediators were related to the outcome |

| Parenting intervention vs. Control | Posttest: Reduced father authoritarian parenting | 1 yr: Mediated effects on reduced child externalizing and internalizing problems | ||

|

Early Risers “Skills for Success” program To prevent conduct disorder and aggression n=151 “at-risk” 1st graders with high levels of teacher-rated aggression Program included 3 components delivered to all families in intervention condition (i.e., Summer program, child group, family skills parent groups) and 2 components delivered as needed by families (i.e., School Support program, Family Support program) Bernat, August, Hektner, & Bloomquist, 2007 |

Early Risers vs. No-intervention control |

3 yrs: Increased effective discipline 3 yrs: Improved social skills |

6 yrs: Mediated to decreased Oppositional-Defiant symptoms 6 yrs: Mediated to decreased Oppositional-Defiant symptoms |

Joint significance test and test of mediated effect (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Sobel, 1982; MacKinnon, 1994 method) |

|

Coping Power To prevent aggression and behavior problems n = 183 5th grade boys rated as aggressive by teachers, primarily low income Program consisted of Coping Power child groups (8 sessions in first year and 20 sessions in second year) or Coping power child groups plus Parent Program (16 monthly groups). In analyses, 2 intervention conditions were combined and compared to a no-intervention control group. Lochman & Wells, 2002 |

Child Program with/without Parent Program vs. Control |

Posttest: Improved parent and youth program targets (five-factor model consisting of parental inconsistent discipline, youth attributions, outcome expectations, internal control, and perceptions of others) Posttest: Improved parent and youth program targets (five-factor model, see above) Posttest: Improved parent and youth program targets (five-factor model, see above) |

1 yr: Three variables mediated to self-reported youth delinquency: Parental inconsistent discipline, youth outcome expectations, and youth internal control 1 yr: Mediated to decreased youth reports of substance use (no individual mediator was significant) 1 yr: Mediated to improved teacher-rated school behavior (no individual mediator was significant) |

Test of whether the program effect on outcome become nonsignificant when adjusted for mediator and mediator to outcome relations, did not cite any test of mediation |

|

Project LIFT: Linking the Interest of Families and Teachers To reduce the risk of delinquency n = 361 5th graders in schools within neighborhoods with high rate of juvenile delinquency 10-week program included a classroom-based social skills and problem solving curriculum, playground behavior modification program, and group parent training sessions weekly for six weeks versus no interventions for school and $2000 in unrestricted funds Degarmo, Eddy, Reid, & Fetrow, 2009 |

LIFT program vs. Control |

Posttest: Improved family interactions during observed problem solving task Posttest: Improved family problem solving and reduced observed playground aggressive behavior Posttest: Reduced observed playground aggressive behavior |

7 yrs: Partially mediated reductions in average tobacco use 7 yrs: Partially mediated effects on growth of tobacco use over 7 years 7 yrs: Partially mediated effects on reductions in acceleration of illicit drug use |

Path model, joint significance test of program on mediator and mediator on outcome and bootstrap test of mediated effect (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993; Preacher & Hayes, 2004) |

|

Strong African American Families To prevent substance use in African American youths n = 667 African American children, age 11, from semi-rural Southern U.S. Program consisted of 7-session parent group and separate 7-session youth group compared to no-intervention control group Brody, Murry, Gerrard, Gibbons, Molgaard, McNair, Brown, et al., 2004; Brody, Kogan, Chen, & Murry, 2008 |

SAAF program vs. control |

Posttest: Increased regulated, communicative parenting (variable consisted of involved-vigilant parenting, communication about sex, racial socialization, and expectations for alcohol use) Posttest: Improved scores on protective parenting index (consisted of regulated communicative parenting variables, see above) Posttest: Improved youth protective factor index (consisted of academic competence/engagement, self-esteem, future goals, risk attitudes) |

Posttest: Mediated increases in youth protective factors (consisted of goal-directed future orientation, negative images of drinkers, negative attitudes about alcohol/sex, and acceptance of parental influence) (Brody et al., 2004) 7 years: Partially mediated reductions in conduct problems for high-risk youths with deviant peer group or low self control at pretest (Brody et al., 2008) 7 years: Partially mediated reductions in conduct problems for high-risk youth (Brody et al., 2008) |

Baron & Kenny’s (1986) 4 conditions for mediation; test of joint significance (Brody et al., 2004) Baron and Kenny (1986)’s 4 conditions, joint significance and Freedman-Schatzkin test of mediated effect (Brody et al., 2008) |

|

Iowa Strengthening Families Program To prevent substance use and other problem behaviors. n = 667 families of 6th graders from low-income rural areas, 238 assigned to ISFP and 208 to control Program consisted of video-adapted version of ISFP program that included 6 parent and 6 child sessions and 1 joint session compared to condition with mailed materials about substance use Spoth, Randall, & Shin, 2008 |

Iowa Strengthening Families Program Vs. Control |

Multiple Linkage Model Posttest: Improved parenting competency (consisted of family rules, parental involvement of child in family activities and decisions, parent anger mangaement within the parent-child relationship, communication) ↓ 2 yrs: Improvements in parenting competency mediated increases in academic engagement |

6 years: Academic engagement at 2 years mediated increases in academic success | Path model with joint significance test and test of mediated effect |

|

Familias Unidas To prevent substance use and risky sexual behavior for Hispanic adolescents n=213 Hispanic 8th graders rated as at least 1 SD above nonclinical mean on Revised Behavior Problems Checklist by parents Program consisted of 9 2-hour parent group sessions and 10 1-hour family visits plus 1-hour booster sessions at 10, 16, 22, and 28 months after the program compared to no-intervention control group Pantin, Prado, Lopez et al., 2009 |

Familias Unidas vs. Control | Posttest: Improved family functioning (consisted of positive parenting, parent/teen communication, parental monitoring) | 30 mo: Partially mediated to growth trajectory of past 30-day substance use across the 30 month period | Joint significance test and test of whether program effect became nonsignificant after adding mediator |

|

Familias Unidas + Preadolescent Training for HIV Prevention (PATH) To prevent substance use and risky sexual behavior for Hispanic adolescents N=268 Hispanic 8th graders and their primary caregivers Familias Unidas program consisted of 9 2-hour parent group sessions and 10 1-hour family visits. PATH program consisted of 4 3-hour parent education sessions and one parent-child session. Two programs together were compared to PATH + English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes for parents or ESOL classes + HeartPower! For Hispanics program (educates parents about adolescent cardiovascular health). Prado, Pantin et al., 2007 |

Familias Unidas + PATH vs. ESOL + PATH | Posttest: Improved family functioning: (positive parenting, parent-teen communication) | 36 mo: Partially mediated to past 90-day cigarette use | Controlled for each mediator in predicting outcomes and determined that paths reduced to nonsignificance were mediated paths. No test of mediated effect |

| Familias Unidas + PATH vs. ESOL+HeartPower! | Posttest: Improved family functioning: (positive parenting, parent-teen communication) | 36 mo: Partially mediated to past 90-day cigarette use and past 90-day drug use | ||

|

New Beginnings Program To prevent mental health problems in children who experienced parental divorce n=240 children from divorced families, ages 9–12, Primarily non-Hispanic Caucasian Program consisted of 11-session mother group with or without 11-session child group. Intervention conditions were combined and compared to control group that received literature about children and divorce. Zhou, Sandler, Millsap, Wolchik, & Dawson-McClure, 2008; Bonds, Wolchik, Winslow, Tein, Sandler, & Millsap, in press |

Mother program with/without child program vs. Control |

Posttest: Improved maternal discipline, n/s for improved mother-child relationship quality Posttest: Improved mother-child relationship quality, n/s for improved discipline |

6 yrs: Mediated effects on grade point average 6 yrs: For high-risk group(externalizing problems and family adversity at baseline), partially mediated effects on externalizing, internalizing and symptoms of mental disorders (especially adolescent-reports) (Zhou et al., 2008) |

Tested mediated effect using confidence intervals (MacKinnon, Lockwood et al., 2002; MacKinnon et al., 2004) |

|

Multiple Linkage Model Posttest: Increased mother-child relationship quality ↓ 3 mo and 6 mo: Led to decreased child internalizing problems Multiple Linkage Model Posttest: Increased effective discipline ↓ 3 mo, 6 mo: Led to decreased child externalizing problems |

6 yr: Led to increased self-esteem and decreased internalizing symptoms 6 yr: Led to less substance use, better academic performance (Bonds et al., in press) |

Multiple linkage model, did not specifically test mediation | ||

|

Parenting Through Change To prevent mental health problems for youth who experienced parental divorce n = 238 divorced/separated mothers of boys ages 6–9, majority Caucasian Program consisted of 16-session parent management training (later condensed to 14 sessions) compared to no-intervention control group Fogatch & DeGarmo 1999; DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004; DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005; Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo, & Beldavs, 2009 |

Parenting Through Change vs. control |

6 mo: Increased positive parenting (consisted of positive involvement, skills encouragement) 1 yr: Improved positive parenting 1 yr: decreased maternal and child depression 1 yr: Improved positive parenting 1 yr: Improved positive parenting |

1 yr: Mediated effects on child, mother, and teacher-reported adjustment (Fogatch & DeGarmo 1999) 30 mo: Mediated effects on child problem behaviors (DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004) 30 mo: Mediated effects on child problem behaviors (DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004) 36 mo: Mediated effects to reduced delinquency (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005) 9 yr: Mediated effect on decreased adolescent delinquency (Forgatch et al., 2009) |

Path model, no explicit mention of mediation (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999) Tested joint significance of program to mediator and mediator to outcome (DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004) Tested whether the program effect was not significant when mediator was added (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005) Tested whether the program effect was not significant when mediator was added (Forgatch, et al., 2009) |

|

Multiple Linkage Model: 1 yr: Improved positive parenting ↓ 8 yr: Led to decreased association with deviant peers across 8 years |

9 yr: To decreased delinquency (Forgatch et al., 2009) | |||

Although these findings provide some evidence that supports parenting as a mediator of the long-term effects of parenting programs on youth outcomes, limitations in these studies present serious barriers to aggregating findings across studies. Most prominently, only 10 of the 46 studies reported findings on mediation. None of the 13 programs delivered to infants or toddlers reported results of mediational analyses. Ten of the 46 studies did not even report on whether program effects occurred on the parenting variables targeted in the program. Only 23 studies reported on long-term program effects on parenting variables one year or longer following the program, with significant effects reported in 17 studies. Also, the intervention components varied widely across the programs, including the presence of components to change other aspects of parents’ behavior (e.g., mental health problems, use of social services) or children’s behavior (e.g., coping, academic performance). There were also differences across studies in the measures of parenting and youth outcomes and in the time lags between the variables in the meditational models.

In addition there was considerable variability in the methods used in the mediation analyses. Many studies tested for mediation by assessing whether a program effect became nonsignificant after the mediator was included in the analysis. This test is not ideal because a mediated effect may be present whether or not the program effect is nonsignificant after adjustment for the mediator. The difference in the program effect coefficient before and after the mediator is added is an estimator of the mediated effect that is appropriately tested for significance, called a difference in coefficients test, and is equivalent to a product of coefficient test for normal theory models. Similarly, mediation effects may be present even when there is not a program effect on the outcome, which may be rare but can occur. More accurate tests are obtained by testing the significance of the program on the mediator and the mediator to outcome after adjustment for the program, known as a joint significance test (MacKinnon et al., 2002). The joint significance test is an easy test to conduct but does not explicitly estimate the mediated effect and its standard error to compute confidence intervals for the mediated effect. The product of coefficient test provides an estimate of the mediated effect and its standard error. A few studies reported the statistical significance of the product of coefficients estimate of the mediated effect using its standard error. Tests with the best balance of statistical power and Type I error rates are product of coefficients tests based on the distribution of the product and tests based on resampling methods and software is available for conducting these more accurate tests (for a complete review of methods to test mediation with examples see MacKinnon, 2008).

Optimally, tests of mediation would present effect size measures of the relation of the intervention to the mediator, the effect size for the mediator to the outcome variable adjusted for the program variable, and the effect size for the relation of the program variable to the outcome adjusted for the mediator. With this information, effect size measures could be combined across studies to yield quantitative evidence for a mediation relation. Additional estimates of mediated effects, effect sizes, and confidence limits would improve comparisons across studies. Reporting estimates and standard errors of mediation relations in each study for each potential mediator would allow for a richer integration of the mediation results across studies and is an important task for future studies. Although the aggregation of evidence for mediation across studies is only beginning, methods for conducting meta-analysis for program effects on outcomes can be extended to mediation effects in parenting programs (MacKinnon & Brown, 2010).

There are many critical theoretical issues that could be probed using meditational analysis. Below, we describe four issues we feel should be given high priority for future research. First, researchers should investigate the specificity of such effects, including whether a mediated effect occurs for one aspect of parenting but not another, whether an intervention effect is specific to one intervention and not another, and whether the mediated effect occurs for some outcome variables but not others. To date, very few researchers have tested whether different aspects of parenting account for changes in different outcomes (e.g., see Zhou et al., 2008 for an exception). Second, because many of the programs are designed to change multiple putative mediators, researchers should investigate multiple mediator models in which the effects on each potential mediator are tested within the same model. Only a few researchers have assessed multiple mediator models (e.g., Lochman & Wells, 2002). Third, researchers should examine whether there are multiple linkages in the meditational chain across development, such that a program has an immediate effect on parenting and that changes in parenting affect problem behaviors at a subsequent time point, and that changes in the problem behavior affect a different problem behavior (e.g., substance use, delinquency) as well as parenting at a later time point. To date, only three research groups have investigated multiple linkage models (Bonds et al., in press; Forgatch et al., 2009; Spoth et al., 2008). Fourth, given that program effects on outcomes are often moderated by other conditions (e.g., level of youth problems at baseline, gender), it is likely that the mediated effect might also be moderated. To date, very few researchers have investigated moderated mediation models (Zhou et al., 2006).

Proposition 2: The long-term effects of intervention-induced changes in parenting are due to changes in social, cognitive, behavioral, and biological processes in parents, youth and in the transactions between youth and their social contexts

Although the mediation findings reviewed above provide evidence that program effects on parenting account for long-term outcomes of some interventions, they do not address the intervening processes between improvements in parenting within one year of completing a parenting program and reductions in youth problem outcomes or improved competencies years later. Theoretically, understanding these processes goes beyond the question of whether there is a causal effect of parenting on child outcomes (Rutter et al., 2001; Collins et al., 2000) to shed light on more basic developmental issues concerning how competencies and disorder develop over time. Practically, understanding these intervening processes should facilitate the development of more effective and efficient interventions, by focusing interventions more strongly on processes that are most likely to maintain program effects over time.

In the first section of this chapter we described a three-level conceptual framework of the processes by which parenting programs might bring about long-term effects on competencies and problem outcomes; processes within parents, processes within youth and transactions between youth and their social contexts. Below, we use this framework as a guide to a research agenda and describe some findings that begin to shed light on these processes.

We proposed that processes that occur within parents might involve changes in parenting behaviors, parents’ sense of efficacy of their parenting and reductions in barriers to effective parenting. Although none of the studies tested these processes as mediators of long-term child outcomes, a number of studies demonstrated that programs effectively changed these processes more than one year following program delivery. Of the 46 trials, long-term effects were reported to change parenting (17 studies), parental efficacy (four studies) and barriers to effective parenting, such as parental mental health problems (seven studies), financial stress (two studies) and quality of the marital relationship (five studies). Intervention trials provide a unique opportunity to study the interrelations between long-term changes on these variables and how they impact child long-term outcomes. For example, it would be interesting to test how program-induced reductions in barriers to parenting, such as economic stress, impact subsequent parenting and whether such changes lead to improvements in child outcomes. Alternatively, it may be that program-induced improvements in parenting set off a cascade of effects involving improvements in youth behavior problems, which then leads to reductions in parental depression, which further improves parenting and leads to long-term effects on youth problem behaviors.