Abstract

Aging and Alzheimer's disease (AD) are associated with declines in the visual perception of self-movement that undermine navigation and independent living. We studied 214 subjects' heading direction and speed discrimination using the radial patterns of visual motion in optic flow. Young (YA), middle-aged (MA), and older normal (ON) subjects, and AD patients viewed optic flow in which we manipulated the motion coherence, spatial texture, and temporal periodicity composition of the visual display. Aging and AD were associated with poorer heading and speed perception at lower temporal periodicity, with smaller effects of spatial texture. AD patients were particularly impaired by motion incoherence created by adding randomly moving dots to the optic flow. We conclude that visual motion processing is impaired by distinct mechanisms in aging and the transition to AD, implying distinct neural mechanisms of impairment.

Keywords: Aging, Alzheimer's disease, vision, spatio-temporal integration, optic flow

Introduction

Aging and AD impair the perception of the radial patterns of visual motion in optic flow [Tetewsky and Duffy 1999] that inform us about the direction and speed of our movement through the environment [Gibson 1957]. Impaired optic flow perception is associated with declines in navigational performance as tested in both real world [Monacelli et al. 2003] and virtual reality [Cushman et al. 2008] environments.

Optic flow perception is linked to dorsal posterior cortical visual processing by the selective activation of this region seen in human imaging studies, although it is unclear exactly which areas play the most critical roles [Greenlee 2000] [Dukelow et al. 2001] [Peuskens et al. 2001]. Visual motion evoked potentials elicited by optic flow show a similar distribution of activation that is diminished in early AD patients with visuospatial impairments [Kavcic et al. 2006]. A specific link to the navigational impairments of early AD has been established by evidence of focal atrophy in right posterior superior temporal cortex [delpolyi et al. 2007].

The dorsal posterior cortical localization of optic flow analysis is consistent with the presence of optic flow selective neurons in homologous monkey dorsal posterior parietal areas [Tanaka et al. 1989] [Duffy and Wurtz 1991a]. Single neurons in this region integrate motion cues across wide spatial segments of the visual field [Duffy and Wurtz 1991b] and prolonged temporal periods of stimulation [Duffy and Wurtz 1997]. These response properties support visual heading direction selectivity [Duffy and Wurtz 1995] [Lappe 1996] that is combined with vestibular signals to create a comprehensive cortical representation of self-movement [Duffy 1998] [Gu et al. 2007]. Neurons in this dorsal extrastriate pathway for visual motion processing may be vulnerable to age-related declines in direction and speed selectivity [Yang et al. 2010] [Liang et al. 2010] in a manner consistent with the loss of intra-cortical inhibitory control mechanisms [Schmolesky et al. 2000]. Such changes may underlie perceptual changes in human aging in which motion perception [Betts et al. 2005] and orientation discrimination [Betts et al. 2007] may depend on high contrast, being impaired under low contrast [Karas and McKendrick 2009], promoting debate over the role in intracortical inhibitory mechanisms serving center-surround interactions.

In young people, the visual motion processing of naturalistically large stimuli is supported by spatial and temporal cue integration that influence direction [Graham and Robson 1987] [Fredericksen et al. 1994] and speed discrimination [Andersen and Saidpour 2002]. Declines in motion coherence, created by the addition of random motion, impairs the processing of such stimuli [Zanker and Hupgens 1994]. Aging has been associated with increases in optic flow heading thresholds, thought to be attributable to declines in central visual processing [Warren, Jr. et al. 1989] [Atchley and Andersen 1998] [Atchley and Andersen 1999]. However, comparison to other forms of visual motion processing have shown that optic flow perception is relatively resistant to the detrimental effects of both brain aging [Billino et al. 2008] and focal cortical lesions [Billino et al. 2009]. In previous studies of both aging and AD, we have found evidence of impaired spatial [O'Brien et al. 2001] and temporal [Kavcic and Duffy 2003] visual cue integration as well as sensitivity to motion incoherence [Tetewsky and Duffy1999].

All of our previous work focused on the effects of aging and AD on optic flow motion coherence thresholds. However, we had not made direct comparisons of our conventional motion coherence approach to alternative approaches. We considered this to be a necessary step to directly test, in a single group of human subjects, whether the effects of motion coherence are simply part of a broader, generalized decline in perceptual processing in aging and AD.

The inherently spatial and temporal integrative nature of optic flow analysis, lead us to hypothesize that declines in spatio-temporal integration may be the best candidate for contributing to impaired optic flow perception in aging and AD. In particular, changes in the spatio-temporal composition of stimuli might have the same effect as adding motion incoherence, suggesting a non-specific decline in visual sensitivity in aging and AD. We have now compared the effects of spatio-temporal composition and motion incoherence finding that spatio-temporal composition effects are mainly related to aging, whereas motion incoherence distinguishes aging and AD.

Methods

Subject Groups

Forty five normal young (YN), 25 middle-age (MA), 115 normal older adult (ON) control subjects and 29 early Alzheimer's disease (AD, MMSE: mn=26., se=.55) patients participated in the study. AD patients were mildly impaired according to the Mini Mental State Exam [Folstein et al. 1975]. All of these patients met NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for probable AD [McKhann et al. 1984] operationalized as functionally significant anterograde memory impairment, reported by patient or caregiver report and confirmed by results on memory tests. Additional impairments included either aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, inattention, visuospatial disorientation, or executive incapacity. Neuro-imaging studies and laboratory tests were employed to support the diagnosis, and reject alternative diagnoses, as indicated by the circumstances of each patient's presentation. We excluded participants with ophthalmological or other neuropsychiatric disorders.

AD patients were recruited from the clinical programs of the University of Rochester Medical Center after being diagnosed by a neurologist or psychiatrist specializing in dementia care, chiefly the senior author. ON subjects were recruited from programs for the healthy elderly or were the spouses of AD subjects, while MA and YN subjects were recruited form University of Rochester employees or students. All of these subjects function without assistance or evidence of neurological or psychiatric disease. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before their enrollment. All procedures were approved by the Research Subjects Review Board at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Most of the ON subjects, and all AD patients, are participating in ongoing psychophysical and neurophysiological studies in our laboratory and in the laboratories of our colleagues at the University of Rochester.

Behavioral Testing

Neuropsychological Tests

To characterize the AD and aging effects, we administered a battery of neuropsychological tests to all subjects. That battery included: 1) The Wechsler Memory Scale – Revised (WMS-R) [Wechsler 1987] Verbal Paired Associates Test I to evaluate immediate and delayed recall for word pairs; 2) Categorical Name Retrieval of animal names to test verbal fluency; 3) The Money Road Map test [Money 1976] to evaluate topographic orientation on a route map with subjects using a pencil to trace the route while identifying left and right turns; 4) The WMS-R Figural Memory test to evaluate immediate visual recognition.; 5) The Judgment of Line Orientation test to evaluate the visual processing of simple spatial relations [Benton et al. 1983]; 6) The Facial Recognition test was used to evaluate the visual processing of complex figures [Benton, Hamsher, Varney, and Spreen1983]. At the initial clinical evaluation, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [Folstein et al. 1975] was used to support the diagnosis of AD. Group comparisons confirmed the presence of broad-based impairments in AD patients (Table 1). The relatively high MMSE scores of our AD patients attest to their being mildly impaired and the fact that we find that subjects with higher pre-morbid achievement levels tend to be more consistent participants in all of the research studies at our laboratory.

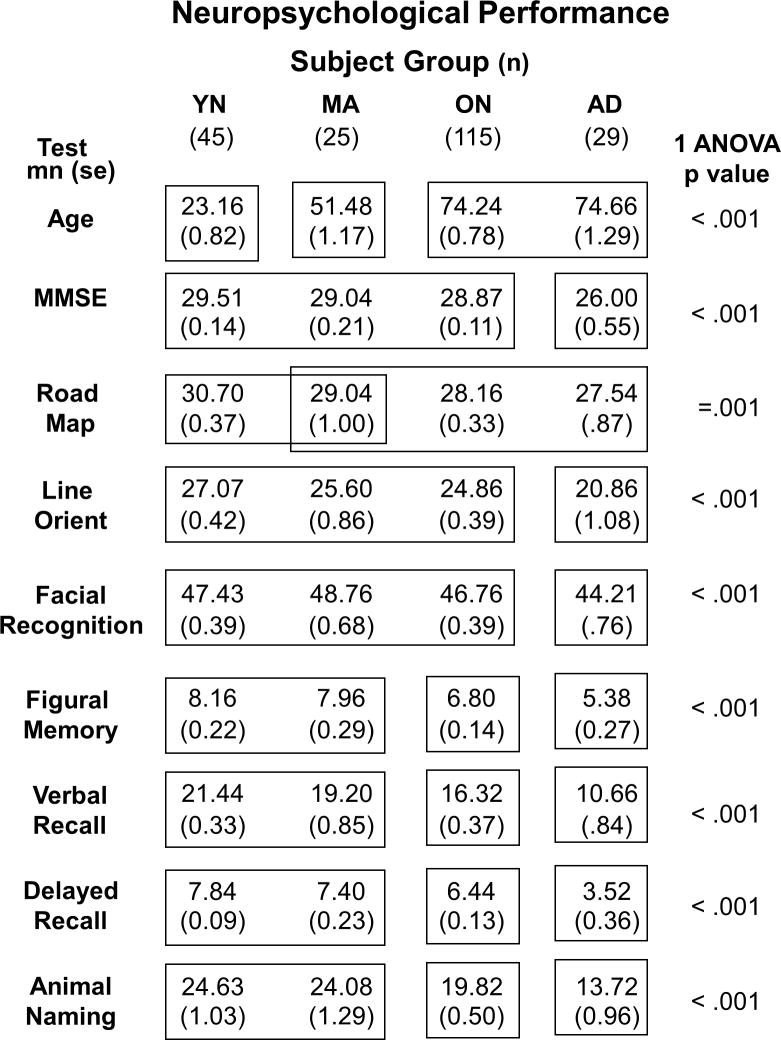

Table 1. Neuropsychological Performance.

Characteristics of each subject group (columns) showing sample size, age, and the results of neuropsychological tests. Each row shows the means and standard errors for the given measure (MMSE = Mini Mental Status Examination). All measures yielded highly significant group effects (p values shown at right). Group differences in each test were identified using post-hoc Tukey's Honestly Significant Differences (THSD, p < .05); groups not significantly different from one another are enclosed in the same box frame, groups that are significantly different from one another are not.

|

Basic Visual Assessment

Visual acuity for all subjects was evaluated by Snellen tables to confirm monocular acuity of at least 20/40 without significant group differences. Contrast sensitivity was evaluated at five spatial frequencies from 0.5 to 18 cycles/° (VisTech Consultants, Dayton, OH, USA). These tests demonstrated that the subjects groups were not significantly different in this respect.

Psychophysical Testing

Visual Motion Stimuli

Subjects sat facing an 8′ × 6′ rear-projection tangent screen on which a TV projector (Electrohome, ON, Canada) presented animated sequences of 2000 white single pixel dots (.13° × .08°, 7.36 cd/m2) presented on a dark background (60° × 40°, 0.7 cd/m2) yielding a Michelson contrast ratio of .83 presented at a 60 Hz frame rate. Where the spatial composition of the stimuli was manipulated by clustering dots, the resulting sizes were multiple of the single pixel size. Individual dots within radial optic flow patterns accelerated in proportion to their distance from the focus of expansion with dot movement speed averaging 30°/s.

At the creation of each moving element, single dots or clusters, that element was randomly assigned a lifetime ranging from 1 to 60 frames; that is, from .0166s to 1s. At lifetime expiration, or when an element moved out of the viewing area, it was pseudo-randomly replaced within areas of that stimulus that had the lowest element density in the upcoming frame to best maintain uniform dot density across the stimulus area. All stimuli had the same, constant and homogenous dot density, luminance, contrast, and average dot speed throughout the stimulus presentation period.

Psychophysical Testing Paradigms

Psychophysical testing was conducted with subjects seated in a light-tight enclosure while engaged in left/right two-alternative forced-choice button press testing. All trials began with an audible tone that prompted the subject to establish centered fixation on the target cross (.5° × .5°). Eye position was monitored by infrared oculometry (ASL, Boston, MA, USA) and was used to abort trials in which gaze went beyond the central 10°. All subjects maintained stable fixation during testing with few aborted trials. During central fixation, a visual motion stimulus was presented for 1 s and was followed an audible tone prompting the subject's left or right button press. Subjects were asked to make their best guess if unsure.

Three types of psychophysical tasks were administered to determine motion coherence thresholds, heading discrimination thresholds, and speed discrimination thresholds. All psychophysical thresholds were obtained using parameter estimation by sequential testing (PEST) technique [Pentland 1980] [Harvey 1997] using a logistic model for the psychometric function was used to estimate the 80% threshold. This selects stimulus values that are near the current estimate of the threshold level and could be characterized as a PEST procedure with fixed stimuli. After the data was collected, a post-analysis verified the best psychometric fit to the data and produced the final threshold and slope for each condition. Usually the heading and speed sessions were done on separate days for the AD and ON subjects. Many MA and YN subjects were able to do both sessions within one day.

Three Visual Motion Testing Paradigms

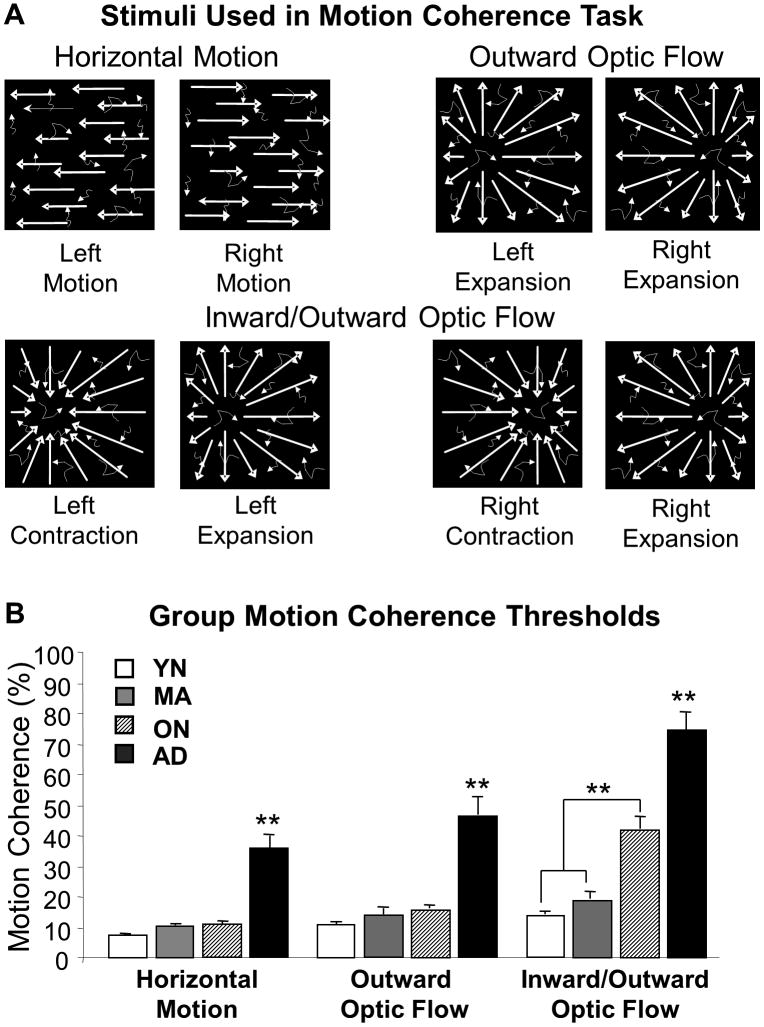

Motion Coherence Heading Discrimination Testing

We determined left/right motion coherence thresholds for three types of visual motion stimuli: left/right horizontal motion coherence, left/right focus of expansion (FOE) outward radial motion coherence, and left/right outward FOE or inward focus of contraction radial motion coherence (Figure 1A). In all three cases, we used a dual testing paradigm in which we initially conduct 20 trials with the preliminary threshold estimate set at a seed value that is based on pilot data from that subject group (80% coherence for AD subjects and 50% coherence for older adults). Thereafter, each subject's preliminary threshold is used to seed a second round of 50 trials to obtain a final threshold estimate. These perceptual thresholds reflect the percentage of dots in coherent motion in stimuli ((coherently moving dots/(coherently moving dots + random dots)) * 100). The percentage of coherently and randomly moving dots varied between trials for the determination of motion coherence thresholds. In each stimulus frame, all dots had an equal probability of being assigned to random or pattern motion. Dots assigned to random motion were then randomly re-positioned in the display area whereas the pattern dots underwent algorithmic re-positioning to form the motion coherent stimulus.

Figure 1.

Visual motion coherence thresholds determined using the highest spatial and temporal periodicity stimuli as an orthogonal measure of motion perception. A. Left/right horizontal motion contained either leftward or rightward moving dots (upper left panel) along with randomly moving dots; Left/right outward radial optic flow stimuli contained an FOE 30 deg to the left or right of center along with randomly moving dots (upper right panel); Left/right inward/outward radial optic flow stimuli contained an FOE 30 deg to the left or right of center along with randomly moving dots (lower panel). Left- and rightward motion was used to determine a horizontal motion threshold. Left/right FOE inward/outward radial motion was used to determine left/right center of motion discrimination thresholds. B. Motion discrimination coherence thresholds (ordinate) horizontal, left/right outward FOE motion stimuli, left/right FOE inward/outward motion stimuli for YNC (open bars), MNC (grey filled bars), ONC (hash filled bars), and EAD (black filled bars) subjects (abscissa). These data yielded significant group X threshold interactions attributable to increased radial thresholds in the ON and AD groups.

Horizontal motion stimuli consisted of a full-screen display consisting of leftward or rightward moving dots moving at 30°/s, variably intermixed with random dot motion. Radial motion stimuli consisted of dots moving in a radial pattern out from or in to a center of motion on the horizontal meridian, 15° to the left or right of center, variably intermixed with random dot motion. The horizontal and radial coherent motion patterns were intermixed with random dot motion, variably intermixed with random dot motion.

Spatio-temporal Composition Heading Discrimination Testing

In heading discrimination testing for the effects of spatio-temporal stimulus composition, the FOE in 100% motion coherence outward radial optic flow stimuli was displaced varying distances along the horizontal meridian, maintaining the mean speed of 30°/s across all stimuli. FOE displacement was randomly directed to either the left or right side of the screen center. Such stimuli simulate the self-movement scene while the observer moves in various straight line heading directions to the left or right of centered gaze.

The PEST algorithm randomly presented the FOE on the left or right side, varying the eccentricity of the FOE to determine the 80% correct left/right heading discrimination threshold. Subjects responded by pressing the button on the side corresponding to the side on which they perceived the location of the FOE. Thresholds were determined at each of nine spatio-temporal stimulus compositions in a fully randomized sequence of stimulus conditions (see next section on Spatio-Temporal Stimulus Composition). There were 54 trials for each spatio-temporal stimulus condition, with the first eight trials presenting the largest heading differences to accommodate subjects to the stimuli in the task and determine initial threshold estimates.

The left or right eccentricity of the focus of expansion (FOE) was determined on a logarithmic scale; that is, log(θ), where θ is the deviation in degrees from the central axis. The log scale for heading discrimination was sampled at twelve points which covered a broad range of FOE eccentricities with a minimum eccentricity of 0.135° and the maximum eccentricity of 32°, where the central angle of 0 degrees was from the observer to the screen center.

In all stimuli presented in this task, moving dots were excluded from 5 deg wide band along the vertical meridian, extending from the bottom to the top of the display area. This motion exclusion band was imposed to promote stable fixation on the centered fixation point and to discourage the use of vertical motion above and below the FOE in making peri-central heading estimates.

Spatio-temporal Composition Speed Discrimination Testing

In speed discrimination testing for the effects of spatio-temporal stimulus composition, a 100% coherence outward radial motion stimulus, with its FOE at the center of the screen, was manipulated to symmetrically decrease the speed of motion on one side of the stimulus while increasing the speed of motion on the other side. Symmetrical speed changes were randomly selected to increase the speed on the left or right side, while decreasing speed on the other side, maintaining the mean speed of 30°/s across all stimuli. Such stimuli simulate the self-movement scene which can occur during turning paths of the observer's self-movement heading direction with fixed head and gaze position.

The PEST algorithm randomly varied the speed difference between the sides to determine the subject's left/right speed discrimination threshold. Subjects responded by pressing the button corresponding to the side on which they perceived the faster motion. Speed discrimination thresholds were determined at each of nine spatio-temporal stimulus compositions in a fully randomized sequence of stimulus conditions (see next section on Spatio-Temporal Stimulus Composition). There were 54 trials for each spatio-temporal stimulus condition, with the first eight trials presented the largest speed differences to accommodate subjects to the stimuli and determine initial threshold estimates.

The left/right speed ratio was determined on a logarithmic scale; that is, log(Δs) where Δs is in pixels shift per second along the z-axis such that one side would have a speed of s0 + (Δs)/2 and the other s0 - (Δs)/2. The log scale for speed discrimination was sampled at twelve points which covered a broad range of speed differences with a minimum speed difference of 30 pixels shift per second (2.1°/s) and the maximum difference of 300 (8.6°/s), where the central speed was 420 pixels shift per second (30°/s).

In all stimuli presented in this task, moving dots were excluded from a 5 deg wide band along the vertical meridian, extending from the bottom to the top of the display area. This motion exclusion band was imposed to promote stable fixation on the centered fixation point and to discourage the use of kinetic edge effects in making relative speed estimates.

Spatio-Temporal Stimulus Composition

We used random dot stimuli to probe the effects of spatio-temporal decomposition so that they might be comparable to the motion coherence stimuli we have used in studies of aging and AD [Mapstone and Duffy 2010], and the human [Kavcic, Fernandez, Logan, and Duffy2006] and monkey [Yu et al. 2010] neurophysiological studies that we have used to probe the neural mechanisms of optic flow analysis. We used three levels of spatial stimulus composition and three levels of temporal stimulus composition to create a 3 × 3 array of nine spatio-temporal stimulus conditions. (Supplemental Figure 1). In all frames, of all conditions, the total number of illuminated pixels was the same and the total display area was the same, so that the pixel density was the same.

Spatial Composition

Spatial composition of the stimuli was manipulated by varying the size of the white dots in optic flow display. We used 3 element sizes: 1 pixel (.1 × .1°), 9 pixels (.3 × .3 °) and 20 pixels (.5 × .5°). The 3 sizes of elements yielded 3 different spatial frequencies: 2D Fourier analysis of the stimulus images showed that the high spatial texture stimuli (1 pixel) contain spatial frequencies concentrated at 5 – 7.5 cycles/°, the medium spatial texture (9 pixels) at 2.1 - 3.1 cycles/°, and the low spatial texture (21 pixels) at 1.4 - 2. cycles/°. The number of elements was varied in inverse proportion to the number of pixels composing each element, to maintain a constant number of 1197 illuminated pixels per frame to fix overall illumination across all frames. Thus, the number of stimulus elements varies across the three levels of spatial texture: at the highest spatial texture with single pixel elements, there are 1197 elements per frame; at the intermediate spatial texture of nine pixel elements, there are 133 elements per frame; at the lowest spatial texture of 21 pixels elements, there are 57 elements per frame. Elements were placed randomly and moved in the radial expanded pattern dictated by self-movement simulation in heading and speed tasks. Elements that left the display area were replaced randomly by elements in the background region so that a consistent element density across the screen was maintained.

Temporal Composition

Changes in temporal periodicity were created by repeating frames, i.e., varying the dwell time of the elements pattern across display frames. In the highest temporal periodicity the optic flow was presented at normal speed as allowed by video frame rate of 60 Hz, i.e., the elements were radially expanding in the predetermined hop distance in each frame, dwell time 16.7 ms, temporal periodicity 60 Hz. At intermediate and lowest temporal periodicity there were repeating display images in multiple video frames, e.g, increased dwell time: for intermediate temporal periodicity the same display was “frozen” in 3 frames, dwell time 50 ms, temporal periodicity 15 Hz, and in the lowest temporal periodicity the display was “frozen” 7 times, dwell time 117 ms, temporal periodicity 7.5. Subjectively, the medium temporal periodicity appeared choppy, and the low temporal periodicity appeared overtly discontinuous. Nevertheless, most everyone saw the radial pattern in every stimulus, although they expressed uncertainty about difficult heading and speed discriminations.

Statistical Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducting using commercial software SPSS [SPSS 2000]. Differences between the YN, MA, ON, and AD groups were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVAs) tests separately for each neuropsychological and psychophysical tests. Each neuropsychological test score was entered in one-way ANOVA with Group (YN, MA, ON, AD) as a between subjects factor. For psychophysical tests, the heading and speed thresholds were entered in mixed measures ANOVA designs with Group (YN, ON, AD) as a between subjects factor, and levels of each condition as a within subjects factors. Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment for the degrees of freedom was used for the recording site factor due to the inherent violations of the repeated measures assumptions of sphericity. Where appropriate, post-hoc analyses were conducted using Tukey's Honestly Significant Differences (THSD) tests and a family-wise Type I error rate of .05.

We also analyzed the subject group differences by contrasting their score distributions. For graphical presentations we used cumulative quantile plots whereas we tested the differences between these distributions with non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p < .05).

We generated quadratic surface fits to the threshold data for each task and subject group to characterize task and group specific effects of the spatio-temporal composition of the optic flow stimuli. The fit equation is:

| (1) |

where k is a constant reflecting the overall surface level across spatio-temporal frequencies, βSF is the regression co-efficienct for spatial texture, which is multiplied by the stimulus spatial texture (coded -1 [low frequency], 0 [medium frequency], +1 [high frequency]), βTF is the regression co-efficienct for temporal periodicity, which is multiplied by the stimulus temporal periodicity (coded -1 [low frequency], 0 [medium frequency], +1 [high frequency]), and βSF*TF is the regression co-efficienct for a spatio-temporal multiplicative factor, which is multiplied by that spatio-temporal multiplicative factor (coded as the product of the SF and TF terms).

Discriminant function analysis was used to evaluate our ability to classify subjects' group membership based-on neuropsychological measures. Psychophysical measures were combined with neuropsychological, and basic visual performance measures in stepwise multiple linear regression analysis using the F probability of .05 for entry and of .10 for rejection with a constant included in the regression model. This analysis selected measures that were significant predictors of visual perceptual capacities. The multiple linear regression provided β weights that serve as quantitative assessments of the relative contribution of independent factors to a composite measure.

Results

We conducted neuropsychological and psychophysical studies of 214 subjects (Table 1). All subjects showed neuropsychological test scores consistent with group membership. The ON and AD subjects were of similar ages and differed by all other measures except the Money Road Map test. MA, ON, and AD subjects were well differentiated by tests of figural and verbal memory and verbal fluency.

Motion Coherence Threshold Determination

Psychophysically determined motion coherence thresholds were obtained for left vs. rightward horizontal planar motion, left vs. right side foci-of-expansion (FOE) for outward radial motion, and interleaved left vs. right side inward and outward radial motion (Figure 1A). These tests showed significant group differences (two-way ANOVA F 1.55, 283 = 46.36, p < .001), as well as differences between the tests (F3, 183 = 55.58, p < .001) and interaction effects (F4.64, 283 = 8.42, p < .001) (Figure 1B). These effects are greatly driven by the AD group being significantly different from all others on all tests (THSD, P < .01). The mixed in-out radial motion stimuli also showed a significant difference between the ON and the younger groups. Thus, our motion coherence psychophysical measures demonstrate both aging and AD effects.

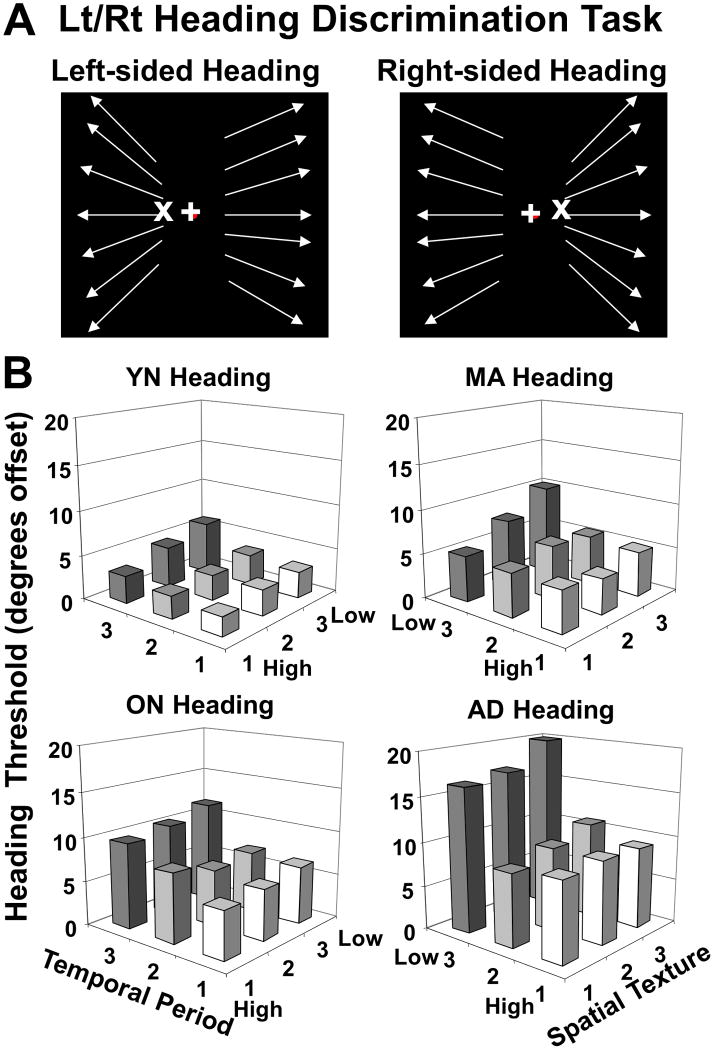

Spatio-Temporal Integration in Heading Discrimination

We assessed the effects of the spatio-temporal composition of motion stimuli on our subjects' ability to see the direction of self-movement simulated by outward radial optic flow. Optic flow stimuli were presented in which the heading direction was displaced by varying degrees to determine two-alternative forced choice left/right heading discrimination thresholds (Figure 2A). The moving elements of the optic flow stimuli were independently altered in size to vary spatial texture composition, and in frame duration to vary temporal periodicity composition.

Figure 2.

Effects of spatio-temporal decomposition on left-right heading discrimination thresholds for YN, MA, ON, and AD subjects. A. Schematic representation of heading task with left panel representing left-sided heading stimulus and right panel representing right-sided heading stimulus; arrows indicate the local direction of dot motion, their angular difference exaggerated here for illustrative clarity. The eccentricity of the simulated heading direction was varied to determine a left-right heading discrimination threshold for each subject under each stimulus condition. Moving dots were excluded from a 5 degree wide band along the vertical meridian to promote stable fixation and discourage the use of the vertical local motion cue above and below peri-central FOEs. B. Averaged heading discrimination thresholds for the nine spatio-temporal periodicity conditions in the heading discrimination task in the four subject groups. These data yielded significant main effects of group, temporal, and spatial texture, as well as temporal periodicity X group and temporal X spatial interaction effects. Post-hoc analyses for subject groups showed AD > ON > MA = YN.

Subject groups showed significantly different heading direction thresholds (mixed model ANOVA, group effect F3,164 = 15.97, p < .001) with age and AD causing elevations of mean thresholds (post-hoc THSDs, AD > ON > MA = YN). Both temporal (F1.42, 233.5 = 8.88, p < .001) and spatial (F1.64, 269.4 = 14.52, p < .001) frequency had significant effects on heading thresholds across all groups. Temporal periodicity also showed a significant interaction with group (F3.37, 233.5 = 8.88, p < .001) and with spatial texture (F3.58, 552.4 = 5.47, p < .001), but spatial texture did not show a significant group interaction. (Figure 2B, see also Supplemental Figure 2) Thus, group comparisons show age and AD related declines in heading perception as greater sensitivity to the spatio-temporal composition of optic flow.

To better visualize spatio-temporal composition effects on aging and AD, we plotted mean thresholds for each stimulus condition across age (decade), considering AD subjects separately (Figure 3). All nine stimulus conditions yielded significant linearly increasing trends with age (p < .05). AD subjects were distinguished in this task, by the low temporal periodicity conditions. This effect was evident in all of the spatial texture conditions, but most evident in the lowest spatial texture condition. AD subjects showed the same range of thresholds as age-matched non-AD subjects in the other temporal periodicity conditions.

Figure 3.

Left-right heading discrimination thresholds across decades, separately showing results for normal controls and AD subjects. Separate line graphs represent thresholds for the nine spatio-temporal composition conditions. These results show significant age-related increases of heading discrimination thresholds for all conditions. The low temporal periodicities yield the highest thresholds at all ages with the roughly parallel lines reflecting the absence of significant spatial X temporal interactions. In AD subjects, heading discrimination thresholds were significantly higher with low temporal periodicity stimuli, across all spatial texture conditions.

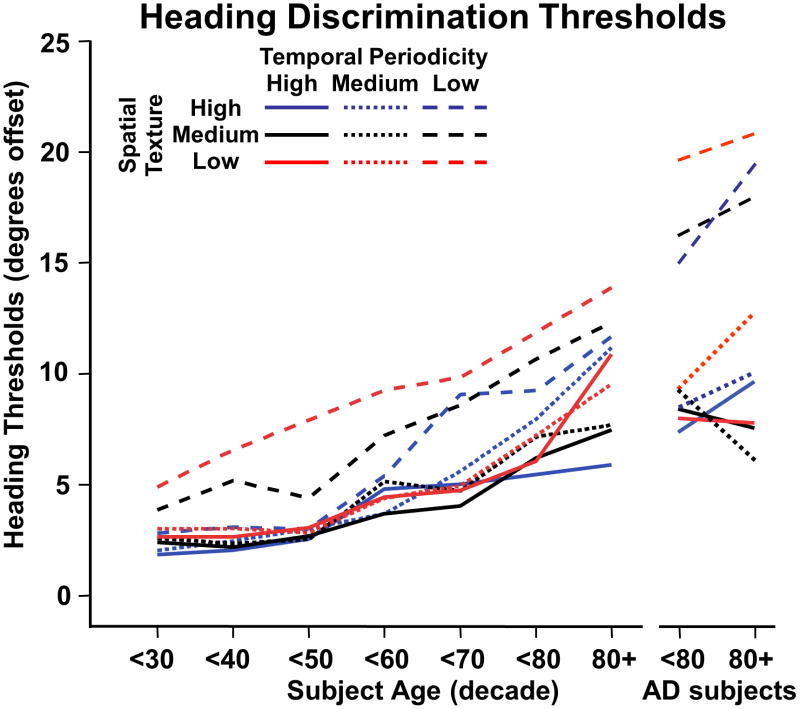

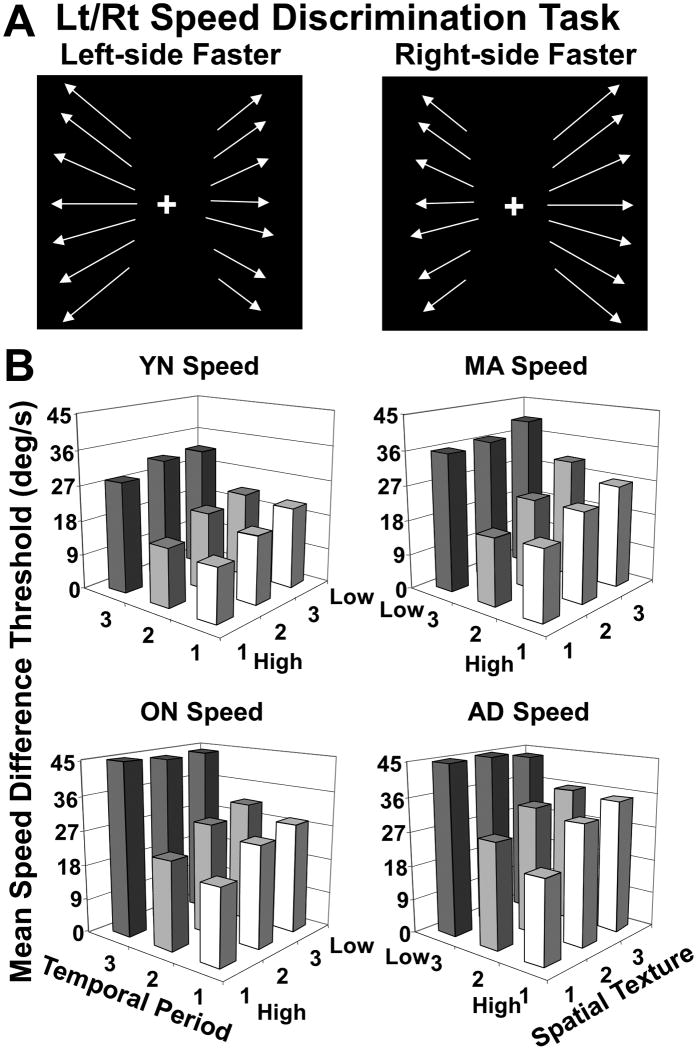

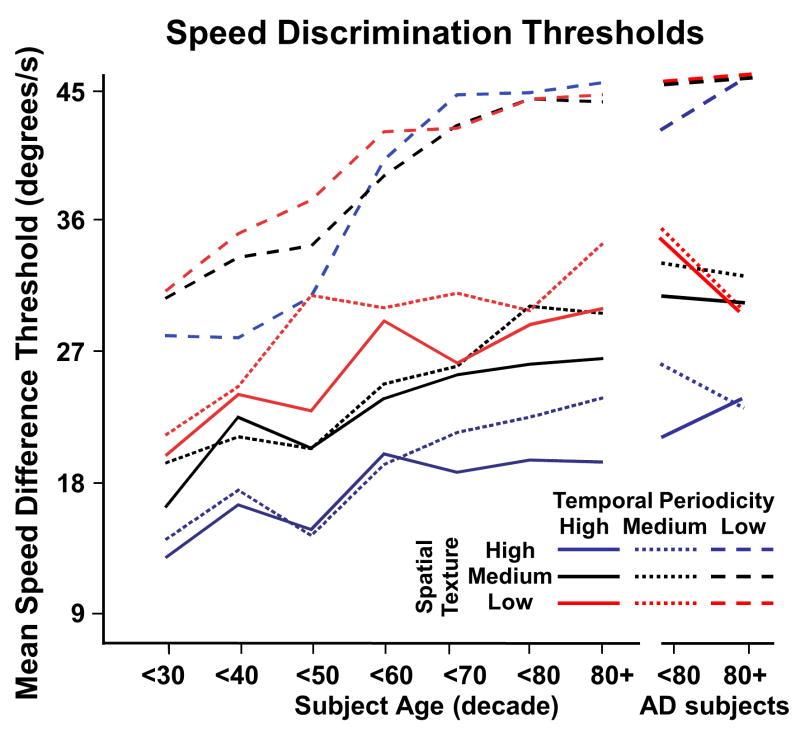

Spatio-Temporal Integration in Speed Discrimination

We assessed the effects of the spatio-temporal composition of motion stimuli on our subjects' ability to see the relative speed of self-movement on the left and right sides of outward radial optic flow. Optic flow stimuli were presented in which the speed on the left and right sides was symmetrically changed to varying degrees to determine two-alternative forced choice left/right faster speed discrimination thresholds (Figure 4A). This ability is used to judge changes in path curvature, as when cornering in a vehicle, and demands the integration of motion information from both sides of the visual field. As in the heading discrimination test, the moving elements in the optic flow were independently altered in size to vary spatial texture composition, and in frame duration to vary temporal periodicity composition.

Figure 4.

Effects of spatio-temporal decomposition on left-right relative speed discrimination thresholds for YN, MA, ON, and AD subjects. A. Schematic representation of speed task with left panel representing left-sided speed stimulus and right panel representing right-sided speed stimulus; arrows indicate the local direction of dot motion, their length representing relative dot speed, with the same angles on the left and right to illustrate the centered FOE. The relative speed of motion in the left and right visual field was varied to determine a left-right relative speed discrimination threshold for each subject under each stimulus condition. Moving dots were excluded from a 5 degree wide band along the vertical meridian to promote stable fixation and discourage the use of kinetic edge effects in making relative speed estimates. These stimuli simulated curved paths, or an symmetric surrounding environment, during observer self-movement toward a centered heading direction. B. Averaged speed discrimination thresholds for the nine spatio-temporal composition conditions in the speed discrimination task in the four subject groups. These data yielded significant main effects of group, temporal, and spatial texture, as well as a significant three-way interaction of subject group, spatial texture, and temporal periodicity. Post-hoc analyses for subject groups showed AD = ON > MA > YN.

Subject groups showed significantly different relative speed thresholds (mixed model ANOVA, group effect F3, 188 = 36.66, p < .001) with age and AD causing similar, significant elevations of mean thresholds (post-hoc THSDs, AD = ON > MA > YN). Both temporal (F1.67, 314.3 = 355.13, p < .001) and spatial (F1.94, 365.6 = 11.33, p < .001) frequency had significant effects on relative speed thresholds across all groups. Temporal periodicity also showed a significant interaction with group (F1.67, 314.3 = 5.6, p < .001) and with spatial texture (F3.84, 722.6 = 24.01, p < .001). In the speed task, spatial texture did not show a significant group interactions, but there was a significant three-way interaction of group X spatial texture X temporal periodicity (F11.53, 722.6 = 2.23, p = .002) (Figure 4B, see also Supplemental Figure 3). Thus, group comparisons show aging, but not AD, related declines in relative speed perception with greater sensitivity to the spatio-temporal composition of optic flow

The substantial effects of aging, but not AD, on susceptibility to temporal periodicity effects is best seen in line plots of mean thresholds for each stimulus condition across age by decade, the AD groups being shown separately (Figure 5). Except for the motion discrimination task with high spatial and temporal periodicity (e.g., single pixel elements at 60 Hz presentation rate) (p = .06), all conditions yielded significant linearly increasing trends (p < .05) across decades; thresholds increased linearly with subject in all stimulus conditions. In this relative speed discrimination task, aging showed the dominant effect, especially with low temporal periodicity stimuli. Unlike our finding in the heading task, the AD group was not readily distinguished from the older subjects in the speed task in any of the spatio-temporal composition conditions.

Figure 5.

Left-right relative speed discrimination thresholds across decades, separately showing results for normal controls and AD subjects. Separate line graphs represent thresholds for the nine spatio-temporal composition conditions. These results show significant age-related increases of relative speed discrimination thresholds in the younger decades with the upper limit of the threshold range reached at low temporal frequencies in the sixth and seventh decade. In AD subjects, relative speed discrimination thresholds were significantly linked to temporal periodicity, across all spatial texture conditions. In contrast with heading discrimination, speed discrimination was relatively insensitive to AD effects.

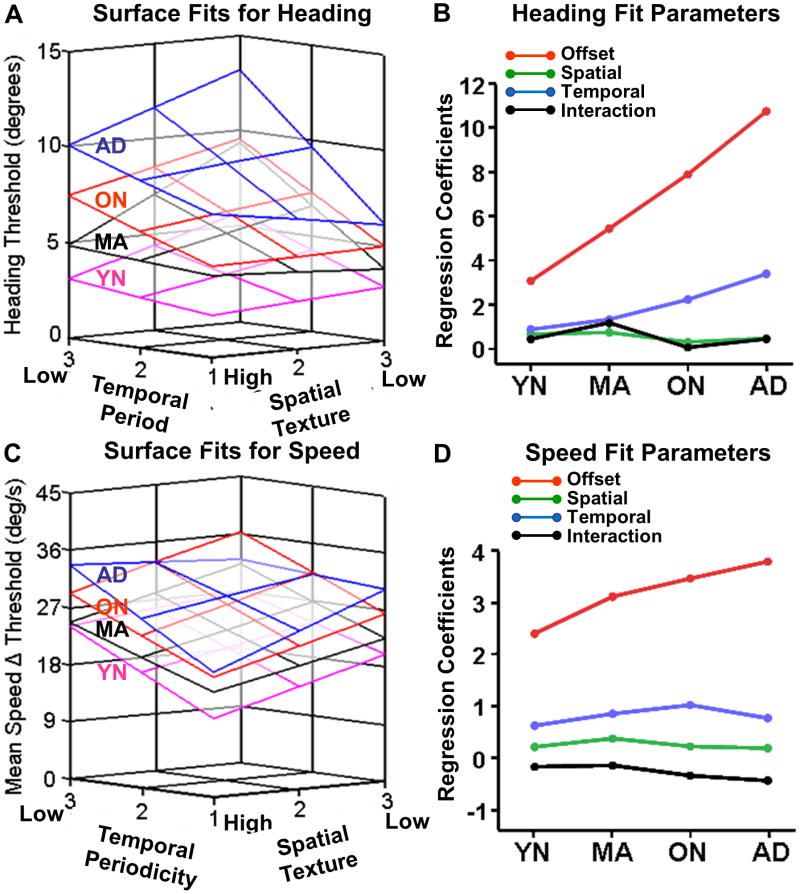

Visual Motion Characterizations of Subject Groups

We summarized the effects of the spatio-temporal composition of optic flow stimuli by generating a 2-D quadratic surface fit to the mean threshold data for each psychophysical task and subject group. The surface fits illustrate the greater distinction between the ON and AD groups in the heading discrimination task than in the speed discrimination task, especially at the low spatial and temporal stimulus composition frequencies (Figure 6A). In the speed discrimination task, the relationship between ON and AD thresholds at the lowest frequencies is reversed (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Surface fits to perceptual threshold data from the heading and speed discrimination tasks show substantial group differences. Threshold data from subjects in each group were separately fit to quadratic functions in relation to spatial and temporal stimulus frequency composition. A. Relations between spatio-temporal stimulus frequency (abscissa) and heading thresholds (ordinate) showed substantial separation of surface fits for the four subject groups. There is increasing surface offsets across groups with the largest separations between groups at the lowest temporal frequencies. B. Surface fit parameters for heading thresholds plotted by group (abscissa) and regression co-efficient (ordinate) showing greatest group differentiation by offset parameter, with substantial further group differentiation by temporal periodicity. C-D. Speed data as surface fits (C, as in A) and fit parameters (D, as in B) showing less evident group separation by offset and temporal periodicity.

The regression parameters of these surface fits (Figures 6B and D) highlight the heading tasks' efficacy in distinguishing subject groups. This display emphasizes that the group separation is mainly attributable to the offset of the surface fits, reflecting group differences in the overall average thresholds across all spatio-temporal frequencies. The surface offset is also the only fit parameter that is significantly correlated between the heading and speed tasks, both across all groups (r = .56, p < .001) and within all groups treated separately (largest p = .02).

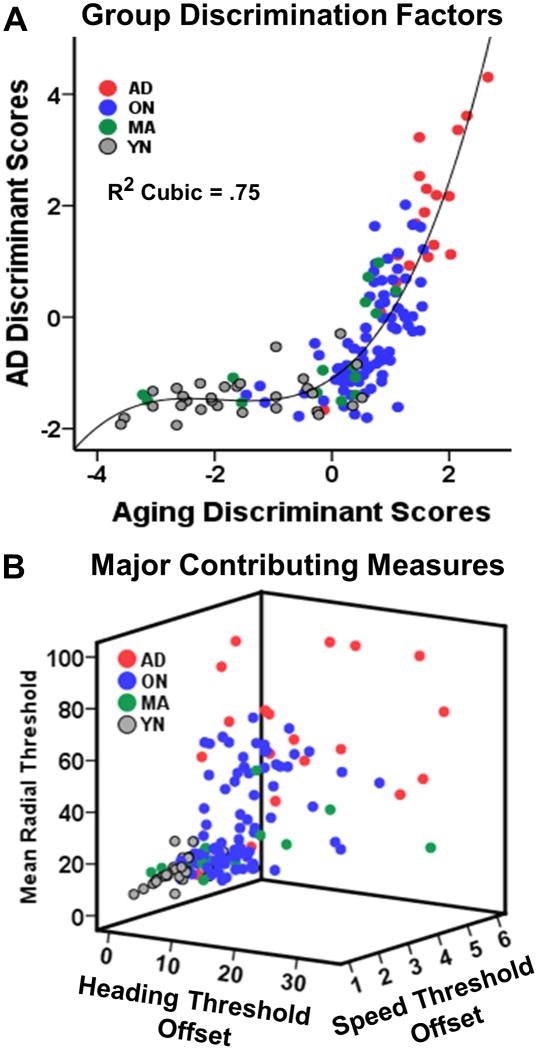

We use discriminant analysis for group classification to determine how we might best describe differences between subject groups. The analysis of aging effects compared YN, MA, and ON subjects and identified a single discriminant factor that loaded three discriminating variables: speed threshold offset (r = .65), the average of the two radial thresholds (r = .5), and speed temporal periodicity effects (r = .45). The analysis of AD effects compared the ON and AD subjects and identified a single discriminant factor that loaded two discriminating variables, the average of the two radial thresholds (r =.85) and heading threshold offsets (r = .60). This analysis classified 74% of subjects in to the correct group: YN (55.6% YN, 24.0% MA, 0% ON, and 0% AD), MA (28.9% YN, 32.0% MA, 7.8% ON, and 0% AD), ON (15.6% YN, 4.4% MA, 89.6% ON, and 20.7% AD), and AD (0% YN, 0% MA, 2.6% ON, and 79.3% AD). Including only the ON and AD groups yielded 93.8% correct classification: ON (96.5% ON and 17.2% AD) and AD (3.5% ON and 82.8% AD)

The finding that our two discriminant analyses each identified a single factor, and that these factors differed in the two analyses, suggests that aging and AD effects are distinguished by our psychophysical parameters. This point is highlighted by the co-plotting of all subjects by both the aging and AD effects (Figure 7A) which creates a continuum well fit by a cubic function (R2=.75). Critical parameters driving the discriminant factors are co-plotted to illustrate the raw data that contribute to distinguishing aging and AD (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Discriminant function analysis of aging and AD effects yield differentiation of subject groups across a two-dimensional continuum. A. Discriminant analysis of aging effects from YN, MA, and ON groups yielded a single factor (abscissa) as did discriminant analysis of AD effects from ON and AD groups (ordinate). Co-plotting each subject's discriminant factor score produced clear group differentiation with YN and AD at opposite extremes and the MA and ON overlapping in intermediate positions with the distribution fitting a cubic function (R2 = .75). B. Distribution of subjects in 3-space created by the variables that are the greatest contributors to group discriminant functions: the surface fit offset parameters and the radial motion coherence thresholds.

Discussion

Spatial Texture and Optic Flow Perception

We examined the impact of spatial texture on optic flow perceptual thresholds by clustering the pixels in radial optic flow. We find small, but significant, effects of spatial texture in all groups (Figures 2, 4, and 6) with higher heading and speed discrimination thresholds with low spatial frequencies. Thus, spatial texture effects in aging and AD yield better performance with many small motion elements.

Our findings are consistent with evidence that visual motion detection is supported by a broad range of spatial frequencies [Yang and Blake 1994] but motion discrimination is favored by high spatial frequencies [Watson and Turano 1995]. Motion detection and discrimination improves with increasing stimulus size (up to ∼9°) [Watamaniuk and Sekuler 1992] in a manner related to eccentricity scaling for cortical magnification [van de Grind 1990] [van and Koenderink 1982] [Fredericksen et al. 1993]. Spatial texture, spatial extent, and visual field location interact such that high spatial texture stimuli are seen as moving faster than speed matched low spatial texture stimuli, with identical stimuli seen as moving faster in central vision as compared to the periphery [Campbell and Maffei 1981] [Cavanagh et al. 1984].

There are significant perceptual benefits with increases in the spatial extent of optic flow, up to at least 60° [Burr and Santoro 2001], linked to improved navigation from visual motion with full-field stimuli [Riecke et al. 2002]. However, there is some special utility of the central visual field when it includes motion parallax cues [Andersen and Braunstein 1985] that may be integrated with better radial direction discrimination in the periphery [Crowell and Banks 1993] and better heading discrimination in the central visual field [Warren and Kurtz 1992].

We previously reported stronger effects of peripheral motion on heading discrimination in ON and AD subjects [Mapstone et al. 2008]. This is consistent with greater benefits of peripheral stimuli on planar motion perception in aging; possibly reflecting the loss of center-surround suppression from declining GABAergic intracortical interactions [Betts, Taylor, Sekuler, and Bennett2005] [Tadin and Blake 2005]. If we had found better relative sensitivity to lower spatial frequencies in aging we might have considered that to be an alternative cause for a greater emphasis on the periphery. As all age groups show similar effects of spatial texture, we reject that hypothesis.

Temporal Periodicity and Optic Flow Perception

We examined the impact of the temporal periodicity composition of visual motion stimuli on optic flow perceptual thresholds by manipulating the number of frames presenting motion in the 60 hz animation sequence. Lower temporal frequencies resulting in poorer performance for all subject groups, in both the heading and speed tasks (Figures 2 and 4), with significant temporal periodicity by group interaction effects showing different magnitudes of this effect across groups.

In the heading task, the low temporal periodicity composition distinguished the AD group from all others, regardless of spatial texture, whereas the AD and non-AD age matched groups were not substantially different in the other temporal periodicity conditions (Figure 3). In the speed task, the low temporal periodicity conditions distinguished both the ON and AD groups from younger subjects (Fig. 5). Thus, temporal periodicity effects distinguished between aging and AD subjects, but in a task-dependent manner.

Interactions between spatial texture, temporal periodicity, and subject group reflected synergistically detrimental effects in MA subjects. Conversely, MAs' decline in performance with lower spatial or temporal periodicity stimuli allows the potential for cue replacement; that is, a high frequency component in either the spatial or temporal domain compensates for a loss of low frequency sensitivity in the other domain. YN subjects do too well to benefit from such synergies, and older subjects do too poorly.

These findings are consistent with studies showing that temporal duration effects depend on the nature of a motion stimulus. Luminance [Allen and Derrington 2000] and contrast [Fredericksen, Verstraten, and van1994] [Burr and Santoro2001] motion detection improves with increasing stimulus duration to asymptote at 150 and 300 ms, respectively. Motion direction discrimination for luminance defined stimuli is optimized after ∼100 ms [Allen and Derrington2000], whereas patterned motion coherence thresholds require ∼440 ms [Watamaniuk and Sekuler1992]. In those settings, the specific task is not critical, with pattern stimuli requiring similar intervals during both direction [Watamaniuk and McKee 1995] and speed [Snowden 1991] discrimination. Still longer durations are required for the discrimination of optic flow patterns: heading discrimination from optic flow requiring ∼2000 ms [Allen and Derrington2000] [Burr and Santoro2001]. Thus, there is a substantial dependency of visual motion processing on the temporal composition of the stimuli, and we now see those effects are larger in aging.

Aging, Alzheimer's, and Optic Flow Perception

We used data from all spatio-temporal composition conditions to fit 2D quadratic surfaces for each subject group and task. Overall, the largest effect distinguishing subject groups was on baseline perceptual thresholds across all spatio-temporal periodicity conditions (Figure 6). This was evident in both the heading and speed tasks, but more clearly in the heading task. Thus, heading and speed thresholds increase with age and AD across spatial and temporal frequencies.

We do not find aging effects on horizontal planar motion coherence thresholds (Figure 1) as seen in an earlier study [Tetewsky and Duffy1999]. That experience is somewhat different than that of others who have found substantial aging effects on with planar motion [Trick and Silverman 1991]. This may be from those investigators using slower planar motion speeds (5.8 °/s) than in our stimuli (30 °/s), an explanation that is consistent with the speed dependency of aging effects on motion processing [Snowden and Kavanagh 2006]. In addition, aging effects may be concentrated in the central visual field [Wojciechowski et al. 1995], which could be de-emphasized by our large-field stimuli used to simulate the panoramic view of the self-movement scene.

In contrast, we see aging effects with left/right radial FOE motion coherence thresholds using interleaved inward and outward radial optic flow (Figure 1) with the largest effects in AD patients, confirming our earlier observations [Tetewsky and Duffy1999] [Mapstone et al. 2003]. We previously attributed this effect to a specific impairment in pattern motion coherence processing [O'Brien, Tetewsky, Avery, Cushman, Makous, and Duffy2001], which may be related to impaired structure from motion perception [Nawrot and Blake 1989].

Our current findings extends these results by showing that the degradation of visual motion signals by altering their spatio-temporal composition does not have the same effects as altering motion coherence composition. In particular, these two types of manipulation do not have the same effects across our subject groups: spatio-temporal composition mainly follows aging effects, whereas motion coherence composition mainly impacts on the transition from aging to the early stages of AD. This is important, for two reasons: First, it shows that all forms of motion signal degradation are not alike; spatial, temporal, and coherence effects are different. Second, it shows that aging and AD are not alike; aging effects are distinguishable from AD effects, implying that there are some differences in the underlying neural mechanisms of perceptual processing declines in aging and AD. These differences may allow us to more precisely identify the fateful transition from aging to AD, and better identify the pathophysiological events that drive that transition.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Spatial-temporal decomposition of optic flow. A. Spatial texture decomposition of optic flow: high spatial texture stimuli contained single pixel white dots, medium spatial frequencies had nine pixel dots, and low spatial frequencies had 21 pixel dots. B. Temporal periodicity decomposition of optic flow: in high temporal periodicity the white dots were coherently displaced in every frame, in medium temporal frequencies they were displaced in every third frame (e.g., existing frame was “frozen” across 4 frames), while in low temporal frequencies the white dots were displaced in every 7th frame (e.g., existing frame was “frozen” across 8 frames).

Supplemental Figure 2. Quartile plots of left-right heading discrimination thresholds for each spatio-temporal composition in the four subject groups. Each plot shows the probability (abscissas) of a subject's having a threshold less than or equal to the indicated value (ordinates) with each subject group plotted as a separate line. The results of Kolmogorov-Smirnov rank-order tests (p < .05) for group differences are indicated by group label enclosure in separate frames over each plot. The largest effects distinguished AD subjects from all others using low temporal periodicity stimuli. The medium and high spatial and temporal composition conditions suggest some synergistic benefits of these conditions all of which showed the best performance in YNs, the worst performance in ADs, and intermediate performance in MA and ONs.

Supplemental Figure 3. Quartile plots of left-right relative speed discrimination thresholds for each spatio-temporal composition condition in the four subject groups. Each plot shows the probability (abscissas) of thresholds less than or equal to the indicated value (ordinates). Subject groups are plotted as separate lines and rank-order results for group differences are shown in frame, as in Supplemental Figure 2. Relative speed thresholds for each subject group reveal that low temporal periodicity stimuli evoke the largest separation of groups, in this task isolating the ON and AD groups from the YN and MA groups.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for Teresa Steffenella's contributions to data acquisition in all of these experiments. This work was supported by grants from NIA (AG17596) and NEI (EY10287).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen HA, Derrington AM. Slow discrimination of contrast-defined expansion patterns. Vision Research. 2000;40:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen GJ, Braunstein ML. Induced self-motion in central vision. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. 1985;11:122–132. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.11.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen GJ, Saidpour A. Necessity of spatial pooling for the perception of heading in nonrigid environments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. 2002;28:1192–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley P, Andersen GJ. The effect of age, retinal eccentricity, and speed on the detection of optic flow components. Psychology & Aging. 1998;13:297–308. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley P, Andersen GJ. The discrimination of heading from optic flow is not retinally invariant. Perception & Psychophysics. 1999;61:387–396. doi: 10.3758/bf03211960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton A, Hamsher K, Varney NR, Spreen O. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment: a clinical manual. New York: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Betts LR, Sekuler AB, Bennett PJ. The effects of aging on orientation discrimination. Vision Res. 2007;47:1769–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts LR, Taylor CP, Sekuler AB, Bennett PJ. Aging reduces center-surround antagonism in visual motion processing. Neuron. 2005;45:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billino J, Braun DI, Bohm KD, Bremmer F, Gegenfurtner KR. Cortical networks for motion processing: effects of focal brain lesions on perception of different motion types. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2133–2144. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billino J, Bremmer F, Gegenfurtner KR. Differential aging of motion processing mechanisms: evidence against general perceptual decline. Vision Res. 2008;48:1254–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr DC, Santoro L. Temporal integration of optic flow, measured by contrast and coherence thresholds. Vision Research. 2001;41:1891–1899. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FW, Maffei L. The influence of spatial frequency and contrast on the perception of moving patterns. Vision Res. 1981;21:713–721. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh P, Tyler CW, Favreau OE. Perceived velocity of moving chromatic gratings. J Opt Soc Am A. 1984;1:893–899. doi: 10.1364/josaa.1.000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Banks MS. Perceiving heading with different retinal regions and types of optic flow. Perception and Psychophysics. 1993:325–337. doi: 10.3758/bf03205187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman LA, Stein K, Duffy CJ. Detecting navigational deficits in cognitive aging and Alzheimer disease using virtual reality. Neurology. 2008;71:888–895. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326262.67613.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deIpolyi AR, Rankin KP, Mucke L, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML. Spatial cognition and the human navigation network in AD and MCI. Neurology. 2007;69:986–997. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271376.19515.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy CJ. MST neurons respond to optic flow and translational movement. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:1816–1827. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy CJ, Wurtz RH. Sensitivity of MST neurons to optic flow stimuli. I. A continuum of response selectivity to large-field stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1991a;65:1329–1345. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy CJ, Wurtz RH. Sensitivity of MST neurons to optic flow stimuli. II. Mechanisms of response selectivity revealed by small-field stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1991b;65:1346–1359. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.6.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy CJ, Wurtz RH. Response of monkey MST neurons to optic flow stimuli with shifted centers of motion. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:5192–5208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05192.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy CJ, Wurtz RH. Multiple temporal components of optic flow responses in MST neurons. Experimental Brain Research. 1997;114:472–482. doi: 10.1007/pl00005656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukelow SP, DeSouza JFX, Culham JC, van den Berg AV, Menon RS, Vilis T. Distinguishing subregions of the human MT + complex using visual fields and pursuit eye movements. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;86:1991–2000. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen RE, Verstraten FA, van d Spatio-temporal characteristics of human motion perception. Vision Research. 1993;33:1193–1205. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90208-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen RE, Verstraten FA, van d Spatial summation and its interaction with the temporal integration mechanism in human motion perception. Vision Research. 1994;34:3171–3188. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JJ. Optical motions and transformations as stimuli for visual perception. Psychological Review. 1957;64:288–295. doi: 10.1037/h0044277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham N, Robson JG. Summation of very close spatial frequencies: the importance of spatial probability summation. Vision Research. 1987;27:1997–2007. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee MW. Human Cortical Areas Underlying the Perception of Optic Flow: Brain Imagin Studies. International Review of Neurobiology. 2000;44:269–292. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. A functional link between area MSTd and heading perception based on vestibular signals. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1038–1047. doi: 10.1038/nn1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey LO. Efficient estimation of sensory thresholds with ML-PEST. Spatial Vision. 1997;11:121–128. doi: 10.1163/156856897x00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas R, McKendrick AM. Aging alters surround modulation of perceived contrast. J Vis. 2009;9:11–19. doi: 10.1167/9.5.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavcic V, Duffy CJ. Attentional dynamics and visual perception: Mechanisms of spatial disorientation in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2003;126:1173–1181. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavcic V, Fernandez R, Logan DJ, Duffy CJ. Neurophysiological and perceptual correlates of navigational impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2006;129:736–746. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappe M. Functional consequences of an integration of motion and stereopsis in area MT of monkey extrastriate visual cortex. Neural Computation. 1996;8:1449–1461. doi: 10.1162/neco.1996.8.7.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Yang Y, Li G, et al. Aging affects the direction selectivity of MT cells in rhesus monkeys. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31:863–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapstone M, Dickerson K, Duffy CJ. Distinct mechanisms of impairment in cognitive ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2008;131:1618–1629. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapstone M, Duffy CJ. Approaching objects cause confusion in patients with Alzheimer's disease regarding their direction of self-movement. Brain. 2010 doi: 10.1093/brain/awq140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapstone M, Steffenella TM, Duffy CJ. A visuospatial variant of mild cognitive impairment: Getting lost between aging and AD. Neurology. 2003;60:802–808. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000049471.76799.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS- ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monacelli AM, Cushman LA, Kavcic V, Duffy CJ. Spatial disorientation in Alzheimer's disease: the remembrance of things passed. Neurology. 2003;61:1491–1497. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.11.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Money J. A Standardized Road Map Test of Direction Sense. San Rafael, CA: Academic Therapy Publications; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrot M, Blake R. Neural Integration of information Specifying Structure from Stereopsis and Motion. 1989:716–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2717948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien HL, Tetewsky S, Avery LM, Cushman LA, Makous W, Duffy CJ. Visual mechanisms of spatial disorientation in alzheimer's disease. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:1083–1092. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.11.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentland A. Maximum likelihood estimation: The best PEST. Perception & Psychophysics. 1980;28:377–379. doi: 10.3758/bf03204398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peuskens H, Sunaert S, Dupont P, Van Hecke P, Orban GA. Human Brain Regions Involved in Heading Estimation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2451–2461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02451.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riecke BE, van Veen HA, Bulthoff HH. Visual homing is possible without landmarks: a path integration study in virtual reality. Presence. 2002;11:443–473. [Google Scholar]

- Schmolesky MT, Wang Y, Pu M, Leventhal AG. Degradation of stimulus selectivity of visual cortical cells in senescent rhesus monkeys. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:384–390. doi: 10.1038/73957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden RJ. Measurement of visual channels by contrast adaptation. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1991;246:53–59. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden RJ, Kavanagh E. Motion perception in the ageing visual system: minimum motion, motion coherence, and speed discrimination thresholds. Perception. 2006;35:9–24. doi: 10.1068/p5399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS I . SPSS v10. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tadin D, Blake R. Motion perception getting better with age? Neuron. 2005;45:325–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Fukada Y, Saito HA. Underlying mechanisms of the response specificity of expansion/contraction and rotation cells in the dorsal part of the medial superior temporal area of the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62:642–656. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetewsky S, Duffy CJ. Visual loss and getting lost in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1999;52:958–965. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trick GL, Silverman SE. Visual sensitivity to motion: Age-related changes and deficits in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurology. 1991;41:1437–1440. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.9.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Grind WA. Smart mechanisms for the visual evaluation and control of self-motion. In: Warren R, Wertheim AH, editors. Perception and Control of Self-Movement. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1990. pp. 357–94. [Google Scholar]

- van D, Koenderink JJ. Spatial properties of the visual detectability of moving spatial white noise. Experimental Brain Research. 1982;45:189–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00235778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WH, Jr, Blackwell AW, Morris MW. Age differences in perceiving the direction of self-motion from optical flow. Journal of Gerontology. 1989;44:P147–53. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.5.p147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WH, Kurtz KJ. The role of central and peripheral vision in perceiving the direction of self-motion. Perception & Psychophysics. 1992;51:443–454. doi: 10.3758/bf03211640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watamaniuk SN, McKee SP. Seeing motion behind occluders. Nature. 1995;377:729–730. doi: 10.1038/377729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watamaniuk SN, Sekuler R. Temporal and spatial integration in dynamic random-dot stimuli. Vision Research. 1992;32:2341–2347. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AB, Turano K. The optimal motion stimulus. Vision Research. 1995;35:325–336. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00182-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale, Revised Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corp.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski R, Trick GL, Steinman SB. Topography of the age-related decline in motion sensitivity. Optom Vis Sci. 1995;72:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhang J, Liang Z, et al. Aging affects the neural representation of speed in Macaque area MT. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;19:1957–1967. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Blake R. Broad tuning for spatial frequency of neural mechanisms underlying visual perception of coherent motion. Nature. 1994;371:793–796. doi: 10.1038/371793a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CP, Page WK, Gaborski R, Duffy CJ. Receptive field dynamics underlying MST neuronal optic flow selectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:2794–2807. doi: 10.1152/jn.01085.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanker JM, Hupgens IS. Interaction between primary and secondary mechanisms in human motion perception. Vision Research. 1994;34:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Spatial-temporal decomposition of optic flow. A. Spatial texture decomposition of optic flow: high spatial texture stimuli contained single pixel white dots, medium spatial frequencies had nine pixel dots, and low spatial frequencies had 21 pixel dots. B. Temporal periodicity decomposition of optic flow: in high temporal periodicity the white dots were coherently displaced in every frame, in medium temporal frequencies they were displaced in every third frame (e.g., existing frame was “frozen” across 4 frames), while in low temporal frequencies the white dots were displaced in every 7th frame (e.g., existing frame was “frozen” across 8 frames).

Supplemental Figure 2. Quartile plots of left-right heading discrimination thresholds for each spatio-temporal composition in the four subject groups. Each plot shows the probability (abscissas) of a subject's having a threshold less than or equal to the indicated value (ordinates) with each subject group plotted as a separate line. The results of Kolmogorov-Smirnov rank-order tests (p < .05) for group differences are indicated by group label enclosure in separate frames over each plot. The largest effects distinguished AD subjects from all others using low temporal periodicity stimuli. The medium and high spatial and temporal composition conditions suggest some synergistic benefits of these conditions all of which showed the best performance in YNs, the worst performance in ADs, and intermediate performance in MA and ONs.

Supplemental Figure 3. Quartile plots of left-right relative speed discrimination thresholds for each spatio-temporal composition condition in the four subject groups. Each plot shows the probability (abscissas) of thresholds less than or equal to the indicated value (ordinates). Subject groups are plotted as separate lines and rank-order results for group differences are shown in frame, as in Supplemental Figure 2. Relative speed thresholds for each subject group reveal that low temporal periodicity stimuli evoke the largest separation of groups, in this task isolating the ON and AD groups from the YN and MA groups.