Abstract

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PHEOs/PGLs) are rare, usually sporadic, catecholamine-producing tumors. However, about 30% of these tumors have been identified of inherited origin. Up to date, nine genes have been confirmed to participate in PHEOs/PGLs tumorigenesis. Germline mutations used to be found in 100% of syndromic cases and in about 90% of patients with positive familial history. In non-syndromic patients with apparently sporadic tumors the frequency of genetic mutations has been recorded up to 27%. Nowadays, genetic testing is recommended for all patients with PHEOs/PGLs. Patients with syndromic lesions and/or positive family history should be tested for appertaining gene. Latest discoveries have shown that the proper order of tested genes in non-syndromic, non-familial cases could be based on histological evaluation, localization and biochemical phenotype of PHEOs/PGLs – the “rule of three”. Identification of gene mutation may lead to early diagnosis, treatment, regular surveillance and better prognosis for patients and their relatives.

Keywords: genetic testing, paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, von Hippel-Lindau disease, neurofibromatosis type 1, succinate dehydrogenase complex genes, immunohistochemistry, catecholamines

Introduction

Although most pheochromocytomas (PHEOs) are sporadic, genetics in the development of these tumors is becoming more and more crucial these days. According to the latest discoveries, already nine genes play an important role in the pathogenesis of PHEOs. These genes include: REarrandged during Transfection (RET) proto-oncogene, von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene (VHL), neurofibromatosis type 1 tumor suppressor gene (NF 1), genes encoding four succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDH) subunits (SDHx; i.e. SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD genes), gene encoding the enzyme responsible for flavination of the SDHA subunit (SDHAF2 or SDH5 gene, for its yeast ortholog), and newly described tumor suppressor TMEM127 gene [1-3,4••,5••,6••,7••]. Furthermore, although previously about 24% of sporadic PHEOs presented genetic mutations [8], nowadays this number is about 30% or more [3,9••,10,11••]. Finally, there are new data linking specific genotype of these tumors to the specific localization, typical biochemical phenotype or future clinical behavior (e.g. SDHB gene mutations are associated with extra-adrenal localization, overproduction of norepinephrine and of dopamine, and a high risk of malignancy) [12••,13••, Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations].

PHEOs are associated with the following familial syndromes: multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2), von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL), von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF 1) and familial paragangliomas (PGLs). Hereditary forms of PHEOs/PGLs can differ in age of diagnosis, localization, malignant potential and catecholamine phenotype – see table 1.

Table 1.

Main familial syndromes associated with pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas

| Syndrome | MEN 2 | VHL | NF 1 | PGL 1 | PGL 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | RET | VHL | NF 1 | SDHD | SDHB |

| Mean age of diagnosis | 30-40 | 20-40 | 40-50 | 30-40 | 20-40 |

| Adrenal PHEOs | +++ | ++ | +++ | -/+ | ++ |

| Bilateral PHEOs | +++ | +++ | + | -/+ | -/+ |

| Extra-adrenal sPGLs | -/+ | + | -/+ | + | +++ |

| Head and neck pPGLs | - | -/+ | - | +++ | + |

| Biochemical profile | E/MN NE/NMN | NE/NMN | E/MN NE/NMN | DA/MT | DA/MT NE/NMN |

| Malignant | -/+ | -/+ | -/+ | -/+ | +++ |

PHEOs = pheochromocytomas; sPGLs = sympathetic paragangliomas; pPGLs = parasympathetic paragangliomas; MEN 2 = multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2; VHL = von Hippel-Lindau disease; NF 1 = neurofibromatosis type 1; PGL 1 = paraganglioma syndrome type 1; PGL 4 = paraganglioma syndrome type 4; RET = Rearrandged during transfection proto-oncogene; VHL = von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene; NF 1 = neurofibromatosis type 1 tumor suppressor gene; SDHD = succinate dehydrogenase subunit D gene; SDHB = succinate dehydrogenase subunit B gene; E = epinephrine; NE = norepinephrine; MN = metanephrine; NMN = normetanephrine; DA = dopamine; MT = methoxytyramine

Familial syndromes associated with PHEOs/PGLs

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2

MEN 2 is an autosomal-dominant syndrome caused by activating germline mutations in the RET proto-oncogene located on chromosome 10q11.2, which encodes a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis [1,2,14]. This syndrome is usually divided into three subgroups: MEN 2A is characterized by medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) in 95%, PHEO in 50%, and hyperparathyroidism (caused by parathyroid hyperplasia/adenoma) in 15-30% of cases. MEN 2B is characterized by MTC in 100%, PHEO in 50% of cases, marphanoid habitus, and multiple mucosal ganglioneuromas. The third group is represented by familial MTC that occurs alone [1,14]. In most cases, MTC is the first presentation of MEN 2. Approximately 90% of MEN 2 cases are of the MEN 2A subtype [1,2,14-16]. More than 85% of patients with MEN 2A have mutations in codon 634, exon 11, and about 95% of MEN 2B cases are caused by a single missense mutation in codon 918, exon 16 of RET proto-oncogene [1,2,15,16].

In MEN 2 patients the PHEOs are usually of adrenal localization, benign and bilateral in more than 50% of patients [1,2,9••,10,17]. The frequency of malignant transformation is less than 5%, but children with MEN 2B-associated PHEOs have a higher risk of malignancy compared to those with MEN 2A or sporadic disease [15]. PHEOs are most commonly diagnosed between the age of 30 and 40 years [2,9••,10,15,17]. MEN 2-related tumors overexpress phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (the enzyme that converts norepinephrine to epinephrine), thus the biochemical phenotype is consistent with hypersecretion of epinephrine in large amounts, resulting in an early clinical phenotype characterized by attacks of palpitations, nervousness, anxiety, and headaches rather than more common patterns of hypertension to be seen in other hereditary tumors [17,18]. The increased plasma and urinary levels of catecholamine O-methylated metabolite of epinephrine – metanephrine in MEN 2 patients distinguish them from those with VHL and SDHx mutations [Eisenhofer G, Pacak, K et al.; unpublished observations].

Von Hippel-Lindau disease

VHL is an autosomal-dominant inherited syndrome with (VHL type 2) or without (VHL type 1) PHEOs [1,2,19]. VHL type 1 is the most common form with predisposition to develop retinal angiomas, central nervous system hemagioblastomas and clear cell renal carcinomas; there could be also other tumors: islet tumors of the pancreas, endolymphatic sac tumors, cysts and cystadenomas of the kidney, pancreas, epididymis, and broad ligament. VHL type 2 is characterized by a predisposition to develop PHEO: without renal carcinoma, and with infrequent other VHL type 1 tumors – type 2A; or with all VHL type 1 tumors – type 2B; and or rarely without all VHL type 1 tumors – type 2C, developing PHEO alone, as apparently sporadic tumor [2,3,17,19-21]. VHL is caused by heterozygous germline mutations in the VHL tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 3p25.5. The gene encodes a VHL protein, which is involved in blood vessel formation by regulating activity of hypoxia inducible factor -1 alpha (HIF-1α). Loss of VHL protein function predisposes the VHL carriers to both benign and malignant tumors in multiple organs [2,3,20,22]. More than 300 mutations of the VHL gene have been identified [1,21]. Approximately 20 % of families with VHL carry de novo mutations, highlighting the need for mutation analysis in patients with apparently sporadic PHEOs [21].

VHL catecholamine-producing tumors are most commonly intra-adrenal PHEOs, although rare extra-adrenal sympathetic PGLs, and parasympathetic head and neck PGLs use to be found too [9••,10,23,24••,25•]. PHEOs associated with VHL are more likely to be bilateral (up to 50%) and more than half of the VHL patients with PHEOs have multiple tumors [2,9••,10,23,24••]. V H L-associated PHEOs appear to undergo malignant transformation less frequently than sporadic PHEOs (< 5 % of patients) [2,17,22,24••]. PHEOs develop in 10%-20% of VHL patients with a mean age of presentation of 30 years [3,9••,10,15]. The biochemical profile of VHL patients differs from those with MEN 2 and NF 1. PHEOs in VHL mostly produce only norepinephrine due to a low expression of phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase [18]. So, VHL patients usually show solitary increases in plasma and urinary normetanephrine levels [Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations].

Neurofibromatosis type 1

NF 1 or von Recklinghausen’s disease is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder caused by inactivating mutations of a tumor suppressor NF 1 gene being localized on chromosome 17q11.2. This large gene encodes a neurofibromin, which is a GTPase-activating protein involved in the inhibition of Ras activity, which controls cellular growth and differentiation. Up to 50% of NF 1 patients with indentified germline mutations carry a de novo mutation [1,2,20]. PHEOs occur in 0.1%–5.7% of patients with NF 1 and in 20%–50% of NF 1 patients with hypertension [26,27]. The clinical diagnosis of NF 1 requires two of the following seven criteria: six or more café-au-lait spots; two or more cutaneous neurofibromas or a plexiform neurofibroma, inguinal, or axillary freckles; two or more benign iris hamartomas (Lish nodules); at least one optic-nerve glioma; dysplasia of sphenoid bone or pseudoarthrosis; and a first degree relative with NF 1, according to the preceding criteria [28]. In addition, a variety of tumors including MTC, carcinoid tumors of the duodenal wall, parathyroid tumors, peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and leukemia, particularly chronic myeloid leukemia have been described with higher frequency in NF 1 than in the general population [2,20].

In NF 1, the mean age of PHEO diagnosis is in the fifth decade (mean age 42 years), the same as in the general population [9••,10,27,29]. On occasion, NF 1 can be diagnosed concurrently with PHEO; however, the skin lesions typical of NF 1 usually lead to the diagnosis of NF 1 in childhood, whereas PHEOs is usually diagnosed in adulthood [26]. In most cases, PHEOs are benign and unilateral, followed by seldom bilateral PHEOs, and rare extra-adrenal sympathetic PGLs. Malignant PHEOs have been identified in up to 12% of cases, similar to the frequency of malignancy in the general population [2,9••,10,27,29]. NF 1-related PHEOs produce both epinephrine and norepinephrine. The increased plasma and urinary levels of metanephrine (indicating epinephrine overproduction) help to discriminate NF 1 patients from those with VHL and SDHx mutations [Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations].

Familial paragangliomas syndromes

Hereditary PGLs syndromes are caused by mutations in the genes encoding the SDH complex subunits [3,4••,30-32]. Inactivation of SDH is associated with the accumulation of succinate, increased oxygen free radical production and resulting in the stabilization of HIF-1α [3,33]. It has been suggested that loss of SDH function mimics chronic hypoxia leading to cellular proliferation. In contrast to normal differentiated cells, which rely primarily on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to generate the energy needed for cellular processes, the most of malignant tumor cells instead rely on aerobic glycolysis, this phenomenon is termed “the Warburg effect” [34]. SDH enzyme complex consists of four subunits encoded by four SDHx genes – SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD genes. Mutation of SDHD gene is responsible for PGL 1 syndrome. SDHC gene mutation is causative for PGL 3 syndrome and SDHB gene for PGL 4 syndrome. Succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 2 (SDHAF2) encoded by SDHAF2 gene (or SDH5, for its yeast ortholog) plays the main role in flavination of SDHA, that is necessary for correct function of this subunit. Loss of SDHAF2 results in loss of SDHA subunit function and leads to reduction in stability of the whole SDH enzyme complex. Mutation of SDHAF2 gene has been discovered to be responsible for PGL 2 syndrome [5••,6••].

PGL 1 is an autosomal-dominant syndrome characterized by familial parasympathetic head and neck PGLs, less frequently by sympathetic extra-adrenal PGLs and rare unilateral or bilateral PHEOs [3,9••,10,11••,29], caused by inactivating mutations in SDHD gene located on chromosome 11q23 [2,3,32]. The mean age of the diagnosis is about 35 years. SDHD mutation carriers should be observed especially for head and neck PGLs, often multifocal, sometimes recurrent and rarely malignant [3,9••,10,11••,29]. Family history in SDHD mutations patients could be inconclusive because of maternal genomic imprinting [3,20,35].

PGL 2 is a very rare autosomal-dominant syndrome defined by familial head and neck PGLs. No cases of PGL 2 syndrome presenting as PHEOs have been described yet. Hereditary transmission occurs exclusively in children of fathers carrying the gene, pointing to the importance of maternal imprinting [36]. The causative gene has been identified as SDHAF2 gene [5••,6••]. The gene was mapped to chromosome 11q13.1 by genomic sequence analysis [5••].

PGL 3 is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome linked to the mutations in SDHC gene, which is located on chromosome 1q21 [2,3,31]. It is characterized by benign and seldom multifocal head and neck PGLs [9••,10,36]. SDHC mutations were originally believed to be associated with parasympathetic head and neck PGLs only [2,36]. However, extra-adrenal sympathetic PGLs and PHEOs have been already reported [9••,11,37•]. No genomic imprinting use to be found in PGL 3 and PGL 4 [21,36].

PGL 4 is an autosomal-dominant syndrome characterized by sympathetic extra-adrenal PGLs, followed by intra-adrenal PHEOs and parasympathetic head and neck PGLs [3,9••,10,11••,29]. The syndrome is caused by inactivating mutations of the tumor suppressor SDHB gene located on chromosome 1p35-p36 [2,3,30]. An increased risk for renal cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), breast and papillary thyroid carcinoma in SDHB mutation carriers may be expected [38•,39•,40,41]. The mean age at the moment of diagnosis of PGL 4 is approximately 30 years. Typically, SDHB-related PGLs originate in extra-adrenal locations (abdomen – Zuckerkandl organ, thorax – mediastinum, and pelvis), use to be often large, mostly solitary and have strong tendency for metastatic spread [9••,10,11••,29,41,42]. Diagnosis is frequently delayed due to an atypical clinical presentation. Symptoms are caused by tumor mass effect rather by catecholamine excess [12••,41,44]. SDHB gene mutations have been implicated as the most common cause in the pathogenesis of malignant PHEOs/PGLs in both children and adults [9••,10,11••,12••,13••,33,41,42]. Recently, SDHB-related PGLs have been observed to be malignant in about 38% of cases [11••]. Even if there is no previous history of familial syndrome related to PHEOs/PGLs, all patients with metastatic tumors should be considered for SDHB gene mutation testing. No clear genotype-phenotype correlations were detected for SDHB mutations. Genotype–phenotype correlations failed to distinguish differences in tumor size, location, malignant potency, aggressive behavior, hypersecretion of dopamine, and metastatic disease at presentation of SDHB-related PGLs between different mutations. Identical SDHB mutations of family members may result in tumors of variable localization and severity [33,42,43••,44].

The predominant biochemical phenotype of SDHB and SDHD related PHEOs/PGLs consisted of dopamine hypersecretion alone or of both dopamine and norepinephrine hypersecretion (SDHB-related tumors) [12••]. Thus increased plasmatic levels of methoxytyramine (indicating dopamine hypersecretion) could discriminate patients with SDHB and SDHD mutations from those with VHL, RET and NF 1 mutations [Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations].

Recently, immunohistochemistry staining for SHDB of removed tumors has been observed as a cost-effective approach for distinguish SDHx related PHEOs/PGLs (the negative staining due to absent of SDHB) from other forms (the positive staining for MEN 2, VHL and NF1 due to present of SDHB) [45••,46••]. Completely absent staining is more commonly found with SDHB mutation, whereas weak diffuse staining often occurs with SDHD mutation [45••]. The sensitivity and specificity of the SDHB immunohistochemistry to detect the presence of SDHx mutation in the prospective series were 100% and 84%, respectively [46••].

New genes related to PHEOs/PGLs

Except above mentioned SDHAF2 gene, the other two genes have been recently detected to be causative for familial PHEOs/PGLs. Previously, SDHA gene was thought to be associated only with a neurodegenerative disorder known as Leigh syndrome, but not with PHEOs/PGLs [3,20,21]. Now the specific mutation of SDHA linked with catecholamine-secreting abdominal PGL has been described. This mutation was present in 4.5% of a large series of PHEOs/PGLs [4••]. Recently, tumor suppressor gene TMEM127 has been identified as a new PHEO susceptibility gene. This gene located on chromosome 2q11 encodes transmembrane protein 127 (TMEM 127), which dynamically associates with a subpopulation of vesicular organelles, Golgi complex and lysosomes, suggesting a subcompartmental-specific effect. Germline TMEM127 mutation was detected in approximately 3% of sporadic-appearing PHEOs [7••].

Genetic testing approaches in clinical practice

Genetic testing in patients with known or suspected familial syndrome

There are two main reasons for genetic testing in these cases. First, the familial syndromes are associated with other malignant tumors, so an early diagnosis of the syndrome (confirmed by the genetic testing) may lead to regular surveillance and early treatment. Second, hereditary forms of PHEOs are often multiple, extra-adrenal, recurrent and sometimes malignant, so a strict follow-up is recommended for better prognosis of the patients [17]. This approach could extend to other family members with the similar benefits. Personal, family history and clinical examination are starting points before the assessing of an appropriate germline mutation. In case of positive family history or of evidence for specific features of above mentioned familial syndromes (see table 1 and table 2), targeted genetic testing should be performed (see figure 2). Germline mutations used to be found in 100% of syndromic patients [9••,47••] and in 41-64% of non-syndromic patients [9••,48••] with positive familial history. Overall, about 90% of patients with positive familial history have a chance to find specific gene mutation [9••]. Whenever a specific germline mutation has been identified, screening for associated disorders should be performed in the patient. Moreover, genetic testing should be offered to patient’s first degree relatives to ascertain the presence or absence of this gene mutation. Predictive testing helps to identify asymptomatic individuals at risk of developing the familial syndrome and early identification of such individuals allows targeted biochemical and radiological screening, which reduces morbidity and mortality [3,17,49].

Table 2.

Clinical features of familial PHEOs/PGLs

| Familial or personal history suspected from PHEOs: |

|

| MEN 2: MEN 2A - MTC, hyperparathyroidism; MEN 2B - MTC, marphanoid habitus, mucosal ganglioneuromas |

| VHL: retinal angiomas, central nervous system hemagioblastomas, renal cell carcinomas, islet tumors of the pancreas, cysts and cystadenomas of the kidney, pancreas, epididymis |

| NF 1: café-au-lait spots, mucosal and cutaneous neurofibromas, inguinal, or axillary freckles, benign iris hamartomas (Lish nodules), optic-nerve glioma, dysplasia of sphenoid bone |

| PGL 1,2,3: usually benign, multiple head and neck tumors, with symptoms mainly related to their location, with maternal imprinting (only in PGL 1 and 2) |

| PGL 4: mostly extra-adrenal tumors (abdomen – Zuckerkandl organ, thorax and pelvis), with symptoms caused by large tumor mass effect rather by catecholamine excess, frequently malignant |

PHEOs = pheochromocytomas; PGLs = paragangliomas; MEN 2 = multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2; MTC = medullary thyroid carcinoma; VHL = von Hippel-Lindau disease; NF 1 = neurofibromatosis type 1; PGL 1,2,3 or 4 = paraganglioma syndrome type 1,2,3 or 4

Genetic testing in patients with non-familial, apparently sporadic PHEOs/PGLs

The majority of PHEOs/PGLs are usually sporadic tumors without known family history, or other symptoms of above mentioned familial syndromes. However, familial nature of the disease may not be recognized due to genomic imprinting, incomplete penetrance, de novo mutation, or incomplete familial history [2,36]. Previous studies displayed that a significant number (7.5-27.0%) of patients with apparently sporadic PHEOs/PGLs were carriers for germline mutations of genes associated with familial syndromes. The frequency of genetic mutations in non-familial PHEOs/PGLs without an obvious syndrome varied significantly (VHL 3.5%-11.1%, RET 0.4%-5.0%, SDHD 0.8%-10.0%, SDHB 1.5%-10.0%) and showed geographical differences [49]. Recently, two large studies have found the frequency of germline mutations in non-syndromic patients with negative family history about 18-19% [47••,48••]. But in the case of multiple or recurrent PHEOs/PGLs, the frequency has been estimated about 39% [9••].

These findings led to the recommendation that all patients with apparently sporadic PHEOs/PGLs should be screened for hereditary causes. Routine testing of all genes is expensive and time consuming, but the proper order of tested genes can reduce the financial expenses. In general the presence of a germline mutation is likely in patients with any of the following features: early onset (<45 years), bilateral, multifocal or extra-adrenal tumors (especially head and neck PGLs), recurrent or malignant disease [9••,36,47••,48••,49].

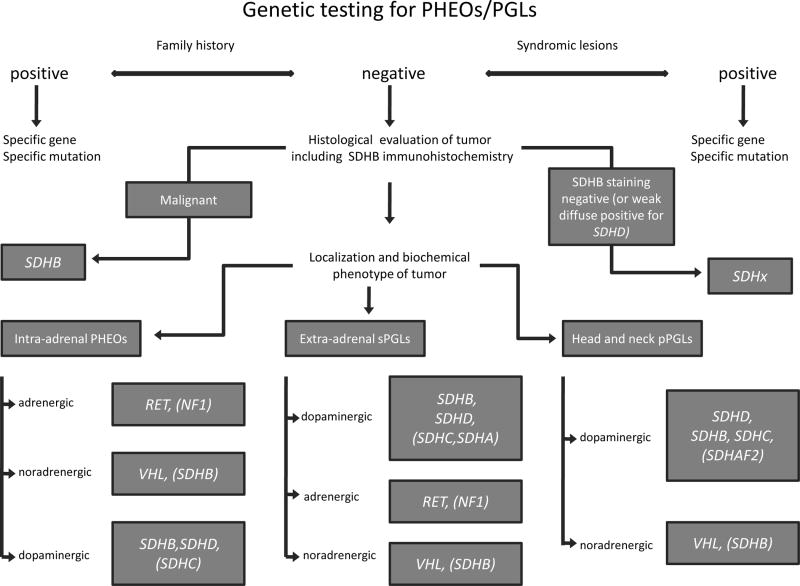

PHEOs associated with NF1 can be identified by a careful physical examination or positive family history, so the genetic testing for NF1 gene is not necessary in principle. Other genes (RET, VHL, SDHB, SDHD, SDHC, rarely SDHA, SDHAF2 and potentially TMEM127) remain to be involved for subsequent mutation analysis. Patients with positive personal history and/or presenting specific syndromic lesions (i.e. syndromic patients, see table 2) should be tested for correspondent genes. Decision-making for gene testing of nonsyndromic patients with sporadic PHEOs/PGLs could be based on histological evaluation, localization and catecholamine production of the tumor – see figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart for genetic testing.

In patients with syndromic lesions and/or positive family history the appropriate specific gene should be tested. In non-syndromic patients with apparently sporadic tumors the immunohistochemistry staining for SDHB presentation could discriminate SDHx-related tumors (SDHB staining is negative, or weak diffuse positive for SDHD mutations) from others (SDHB staining is positive). In case of tumor malignancy the patient is probably carrier for SDHB mutation. If patient with intra-adrenal PHEO have increased levels of metanephrine (indicating hypersecretion of epinephrine), he is probably RET proto-oncogene carrier or suffers from NF 1, but this disease used to be diagnosed in previous clinical evaluation. VHL-related PHEOs produce only norepinephrine (detected by solitary increased normetanephrine levels). Presence of dopamine hypersecretion (detected by increased methoxytyramine levels) could distinguish SDHx-related PHEOs from other inherited forms. SDHx-related PHEOs are mostly associated with SDHB, less frequently with SDHD and very rarely with SDHC mutations. Sympathetic extra-adrenal PGLs of SDHx origin usually overproduce dopamine; SDHB-related tumors produce often norepinephrine and/or dopamine. The genetic testing should start with SDHB (especially in case of solitary large extra-adrenal tumors or of simultaneous extra-adrenal PGL and PHEO occurrence) prior than SDHD gene. Rarely SDHC and very rarely SDHA related extra-adrenal PGLs were described. Sympathetic extra-adrenal PGLs with epinephrine/metanephrine hypersecretion would be probably associated with RET mutations (NF 1 patients use to be clinically diagnosed before). Patients with solitary increased normetanephrine levels (indicating hypersecretion of norepinephrine) would have sympathetic extra-adrenal PGLs due to VHL mutations, or SDHB mutations. Parasympathetic head and neck PGLs are predominantly associated with SDHx mutations and may overproduce dopamine. The genetic testing should start with SDHD gene (especially in multiple tumors). Less frequently SDHB or SDHC mutations are related to these tumors. In case of absence of SDHD, SDHB and SDHC mutations, respectively, SDHAF2 gene mutation should be tested, especially in young age of onset. VHL-related, head and neck PGLs are relatively rare and do not produce dopamine. RET or NF 1 related head and neck PGLs are extremely rare.

Biochemical phenotype: dopaminergic: >10% of plasmatic methoxytyramine levels; adrenergic: >6% of plasmatic metanephrine levels, noradrenergic: everything else [Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations].

PHEOs = pheochromocytomas; sPGLs = sympathetic paragangliomas; pPGLs = parasympathetic paragangliomas; MEN 2 = multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2; VHL = von Hippel-Lindau disease; NF 1 = neurofibromatosis type 1; SDHB = succinate dehydrogenase subunit B; RET = Rearrandged during transfection proto-oncogene; VHL = von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene; NF 1 = neurofibromatosis type 1 tumor suppressor gene; SDHx = succinate dehydrogenase subunits genes; SDHA = succinate dehydrogenase subunit A gene; SDHB = succinate dehydrogenase subunit B gene; SDHC = succinate dehydrogenase subunit C gene; SDHD = succinate dehydrogenase subunit C gene; SDHAF2 = succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 2 gene.

Histological evaluation of PHEOs/PGLs

Malignant PHEOs/PGLs, especially extra-adrenal PGLs, used to be associated mostly with SDHB germline mutations [10,11••,12••,13••,29,33,41,43•,44,48••]. On contrary, malignant tumors in SDHD or SDHC mutation carriers have been described rarely (in less than 5 % of cases) [3,10••,11••,29,33,41,44,48••]. Malignant NF 1-related PHEOs were identified with similar frequency of malignancy like sporadic PHEOs in the general population [2,9••,10••,27,29]. Like VHL-associated PHEOs, MEN 2-associated PHEOs appear to undergo malignant transformation less frequently than sporadic PHEOs, only children with MEN 2B-associated PHEOs have a higher risk of malignancy compared to those with MEN 2A [2,15,17,22,24••].

Immunohistochemistry staining for SDHB positivity could distinguish between SDHx related PHEOs/PGLs and other familial syndromes (MEN 2, VHL, NF 1), or true sporadic tumors with high sensitivity and specificity [45••,46••].

Tumor localization and biochemical phenotype

Identification of intra-adrenal PHEOs suggests mutation of either the RET or VHL gene, than followed by NF 1, SDHB and rarely by SDHD or very rarely by SDHC genes [1,2,9••,10,11••,17,23,25•,27,29,37•]. If the biochemical profile shows elevated metanephrine values (indicating epinephrine overproduction), then RET should be tested first (NF 1 patients are usually diagnosed by clinical investigation). Tumors due to mutations of VHL and SDHx are not characterized by increase of epinephrine/metanephrine hypersecretion. Additional measurement of plasma methoxytyramine (indicating dopamine production) could discriminate patient with SDHx mutations from those with VHL mutations [Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations].

When extra-adrenal PGLs are diagnosed, the germline mutations in SDHx genes used to be are found most commonly [3,9••,10,11••,29,47••,48••], particularly in case of dopamine hypersecretion (detected by increased levels of methoxytyramine) [Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations]. SDHx- related parasympathetic head and neck PGLs are mostly associated with SDHD (especially multiple tumors) and less frequently with SDHB or SDHC mutations [3,4••,9••,10,11••,29,47••,48••]. In the case of negative testing for SDHD, SDHB, and SDHC, respectively, testing for SDHAF2 gene mutation should be performed, especially in young age of diagnosis [6••]. If the tumors do not overproduce dopamine/methoxytyramine, thereafter the testing for VHL gene mutations should be made first, because parasympathetic head and neck PGLs are extremely rare in patients with MEN 2 or NF 1 [9••,10,25•,29,47••,48••].

Extra-adrenal sympathetic PGLs (in abdomen, thorax and pelvic localization) are usually related to SDHB (especially solitary, large tumors), less frequently to SDHD, rarely to SDHC and very rarely to SDHA mutations [9••,10,11••,37•,41,47••,48••]. SDHB-related tumors usually overproduce dopamine and norepinephrine (detected by increased plasmatic levels of methoxythyramine and normetanephrine, respectively). The increased levels of metanephrine (indicating epinephrine hypersecretion) are specific for MEN 2 (or NF 1) patients and could distinguish them from those with VHL and SDHx mutations. VHL-related tumors produce only norepinephrine/normetanephrine [Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, et al.; unpublished observations].

Conclusion

Now, it has been proved that about 30% or more of PHEOs/PGLs may be of inherited origin. Up to day, nine genes have been established to cause the familial PHEOs/PGLs. These tumors might be a part of the complex clinical syndromes or could be found alone as apparently sporadic neoplasmas. The clinical, histological and biochemical evaluation (the “rule of three”) could help with the decision-making for subsequent gene analysis. Genetic testing for appropriate germline mutation leads to the correct diagnosis and by this way to regular surveillance, early treatment and better prognosis for the patients with PHEOs/PGLs. This approach could extend to other family members with the similar benefit.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Mr. Tobias Engel for his technical help with the figure.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

-

•

Of importance

-

••

Of major importance

- 1.Koch CA, Vortmeyer AO, Huang SC, et al. Genetic aspects of pheochromocytoma. Endocr Regul. 2001;35:43–52. Erratum in: Endocr Regul 2001, 35:94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant J, Farmer J, Kessler LJ, et al. Pheochromocytoma: the expanding genetic differential diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1196–1204. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benn DE, Robinson BG. Genetic basis of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:435–450. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Burnichon N, Brière JJ, Libé R, et al. SDHA is a tumor suppressor gene causing paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq206.. Authors identified a heterozygous germline SDHA mutation, p.Arg589Trp, in a woman suffering from catecholamine-secreting abdominal PGL. They also investigated 202 PHEOs/PGLs for loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the SDHA, SDHB, SDHC and SDHD loci. LOH was detected at the SDHA locus in the patient’s tumor but was present in only 4.5% of a large series of PHEOs/PGLs.

- 5••.Hao HX, Khalimonchuk O, Schraders M, et al. SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science. 2009;325:1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.1175689.. Authors investigated a mitochondrial protein named SDH5, which interact with the catalytic subunit of the SDH complex. SDH5 is required for SDH-dependent respiration and for SDHA flavination (incorporation of the flavin adenine dinucleotide cofactor). Germline loss-of-function mutations in the human SDH5 gene, located on chromosome 11q13.1, segregate with disease in a family with hereditary PGLs.

- 6••.Bayley JP, Kunst HP, Cascon A, et al. SDHAF2 mutations in familial and sporadic paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:366–372. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70007-3.. Authors identified a pathogenic germline DNA mutation of SDHAF2, 232G-->A (Gly78Arg) in family with head and neck PGLs with a young age of onset.

- 7••.Qin Y, Yao L, King EE, et al. Germline mutations in TMEM127 confer susceptibility to pheochromocytoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:229–233. doi: 10.1038/ng.533.. Authors identified the transmembrane-encoding gene TMEM127 on chromosome 2q11 as a new PHEO susceptibility gene. In a cohort of 103 samples, they detected truncating germline TMEM127 mutations in approximately 30% of familial tumors and about 3% of sporadic-appearing PHEOs.

- 8.Neumann HP, Bausch B, McWhinney SR, et al. Germ-line mutations in nonsyndromic pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1459–1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Mannelli M, Castellano M, Schiavi F, et al. Clinically guided genetic screening in a large cohort of italian patients with pheochromocytomas and/or functional or nonfunctional paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1541–1547. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2419.. Authors examined 501 consecutive patients with PHEOs/PGLs (secreting or nonsecreting). Germline mutations were detected in 32.1% of cases, but frequencies varied widely depending on the classification criteria and ranged from 100% in patients with associated syndromic lesions to 11.6% in patients with a single tumor and a negative family history.

- 10.Amar L, Bertherat J, Baudin E, et al. Genetic testing in pheochromocytoma or functional paraganglioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8812–8818. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11••.Burnichon N, Rohmer V, Amar L, et al. The succinate dehydrogenase genetic testing in a large prospective series of patients with paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2817–2827. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2504.. Authors examined 445 patients with head and neck and/or thoracic-abdominal or pelvic PGLs. A head and neck PGL was present in 97.7% of the SDHD and 87.5% of the SDHC mutation carriers, but in only 42.7% of the SDHB carriers; on contrary, a thoracic-abdominal or pelvic location was present in 63.5% of the SDHB, 16.1% of the SDHD, and in 12.5% of the SDHC mutation carriers. A malignant PGL was documented in 37.5% of the SDHB, 3.1% of the SDHD, and none of the SDHC mutation carriers.

- 12.Timmers HJ, Kozupa A, Eisenhofer G, et al. Clinical presentations, biochemical phenotypes, and genotype-phenotype correlations in patients with succinate dehydrogenase subunit B-associated pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:779–786. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2315.. Twenty-nine patients with SDHB-related abdominal or thoracic PGL were included. Mean age at diagnosis was 33.7+/-15.7 yr. Tumor-related pain was among the presenting symptoms in 54% of patients. Seventy-six percent had hypertension, and 90% lacked a family history of PGL. All primary tumors but one originated from extraadrenal locations. Mean +/- sd tumor size was 7.8 +/- 3.7 cm. Twenty eight percent presented with metastatic disease and all but one eventually developed metastases after 2.7 +/- 4.1 yr. The biochemical phenotype was consistent with hypersecretion of both norepinephrine and dopamine in 46%, norepinephrine only in 41%, and dopamine only in 3%. No obvious genotype-phenotype correlations were identified.

- 13••.Amar L, Baudin E, Burnichon N, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase B gene mutations predict survival in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;10:3822–3828. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0709.. Fifty-four patients with malignant PHEOs/PGLs were included. Germline mutations were identified in SDHB (n = 23, including 21 patients with apparent sporadic tumors) and VHL (n = 1) genes, and two patients had neurofibromatosis 1. Patients with SDHB mutations were younger, more frequently had extra-adrenal tumors, and had a shorter metanephrine excretion doubling time. The presence of SDHB mutations was significantly and independently associated with mortality.

- 14.Raue F, Frank-Raue K. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: 2007 update. Horm Res. 2007;68(Suppl 5):101–104. doi: 10.1159/000110589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Ilias I. Diagnosis of pheochromocytoma with special emphasis on MEN2 syndrome. Hormones (Athens) 2009;8:111–116. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulligan LM, Marsh DJ, Robinson BG, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: report of the International RET Mutation Consortium. J Intern Med. 1995;238:343–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366:665–675. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhofer G, Walther MM, Huynh TT, et al. Pheochromocytomas in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 display distinct biochemical and clinical phenotypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1999–2008. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, et al. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med. 1990;77:1151–1163. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.2.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elder EE, Elder G, Larsson C. Pheochromocytoma and functional paraganglioma syndrome: no longer the 10% tumor. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:193–201. doi: 10.1002/jso.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petri BJ, van Eijck CH, de Herder WW, et al. Phaeochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1381–1392. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–215. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hes FJ, Höppener JW, Lips CJ. Clinical review 155: Pheochromocytoma in Von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:969–974. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24••.Srirangalingam U, Khoo B, Walker L, et al. Contrasting clinical manifestations of SDHB and VHL associated chromaffin tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:515–525. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0239.. Thirty-one subjects with chromaffin tumours were assessed; 16 subjects had SDHB gene mutations and 15 subjects had a diagnosis of VHL. VHL-related tumours were predominantly adrenal PHEOs (84.6%), while SDHB-related tumours were predominantly extra-adrenal PGLs (76%). Multifocal disease was present in 60% of the VHL cohort (bilateral PHEOs) and only in 19% of the SDHB cohort, while metastatic disease was found in 31% of the SDHB cohort but not in the VHL cohort.

- 25•.Boedeker CC, Erlic Z, Richard S, et al. Head and neck paragangliomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1938–1944. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0354.. Twelve patients were found to have hereditary non-SDHx head and neck PGLs of a total of 809 head and neck PGLs, 11 in the setting of germline VHL mutations and one of a RET mutation.

- 26.Walther MM, Herring J, Enquist E, et al. von Recklinghausen’s disease and pheochromocytomas. J Urol. 1999;162:1582–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zöller ME, Rembeck B, Odén A, et al. Malignant and benign tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 in a defined Swedish population. Cancer. 1997;79:2125–2131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, et al. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA. 1997;278:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bausch B, Borozdin W, Neumann HP. European-American Pheochromocytoma Study Group: Clinical and genetic characteristics of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2729–2731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc066006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Astuti D, Latif F, Dallol A, et al. Gene mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase subunit SDHB cause susceptibility to familial pheochromocytoma and to familial paraganglioma. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:49–54. doi: 10.1086/321282. Erratum in: Am J Hum Genet 2002, 70:565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niemann S, Müller U. Mutations in SDHC cause autosomal dominant paraganglioma, type 3. Nat Genet. 2000;26:268–270. doi: 10.1038/81551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baysal BE, Ferrell RE, Willett-Brozick JE, et al. Mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in hereditary paraganglioma. Science. 2000;287:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Timmers HJ, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Clinical aspects of SDHx-related pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;2:391–400. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hensen EF, Jordanova ES, van Minderhout IJ, et al. Somatic loss of maternal chromosome 11 causes parent-of-origin-dependent inheritance in SDHD-linked paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma families. Oncogene. 2004;23:4076–4083. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiménez C, Cote G, Arnold A, Gagel RF. Review: Should patients with apparently sporadic pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas be screened for hereditary syndromes? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2851–2858. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Peczkowska M, Cascon A, Prejbisz A, et al. Extra-adrenal and adrenal pheochromocytomas associated with a germline SDHC mutation. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:111–115. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0726.. Authors presented family with adrenal pheochromocytoma and carotid body tumor as parts of a familial pheochromocytoma-paraganglioma syndrome associated with a germline mutation in SDHC gene.

- 38•.Ricketts C, Woodward ER, Killick P, et al. Germline SDHB mutations and familial renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1260–1262. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn254.. Authors investigated whether germline mutations in SDH subunit genes (SDHB, SDHC, SDHD) were associated with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) susceptibility in 68 patients with no clinical evidence of an RCC susceptibility syndrome. No mutations in SDHC, or SDHD were identified in probands, but 3 of the 68 (4.4%) probands had a germline SDHB mutation.

- 39•.Pasini B, McWhinney SR, Bei T, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of patients with the Carney-Stratakis syndrome and germline mutations of the genes coding for the succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:79–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201904.. Authors investigated 11 patients with the dyad of PGL and gastric stromal sarcoma; in eight, the GISTs were caused by germline mutations of SDHB, SDHC and SDHD genes, respectively.

- 40.Lee J, Wang J, Torbenson M, et al. Loss of SDHB and NF1 genes in a malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast as detected by oligo-array comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neumann HP, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, et al. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA. 2004;292:943–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.943. Erratum in: JAMA 2004 292:1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brouwers FM, Eisenhofer G, Tao JJ, et al. High frequency of SDHB germline mutations in patients with malignant catecholamine-producing paragangliomas: implications for genetic testing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4505–4509. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43••.Ricketts CJ, Forman JR, Rattenberry E, et al. Tumor risks and genotype-phenotype-proteotype analysis in 358 patients with germline mutations in SDHB and SDHD. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:41–51. doi: 10.1002/humu.21136.. Authors assessed 358 patients with SDHB (n=295) and SDHD (n=63) mutations. Risks of head and neck PGLs and PHEOs in SDHB mutation carriers were 29% and 52%, respectively, at age 60 years respectively, and 71% and 29%, respectively, in SDHD mutation carriers. Risks of malignant pheochromocytoma and renal tumors (14% at age 70 years) were higher in SDHB mutation carriers. No clear genotype-phenotype correlations were detected for SDHB mutations.

- 44.Benn DE, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Reilly JR, et al. Clinical presentation and penetrance of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma syndromes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:827–836. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45••.Gill AJ, Benn DE, Chou A, et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB triages genetic testing of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD in paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:805–814. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.12.005.. Authors defined positive, weak diffuse and negative immunohistochemistry staining for SDHB. All 12 SDH mutated tumors (6 SDHB, 5 SDHD, and 1 SDHC) showed weak diffuse or negative staining, nine of 10 tumors with known mutations of VHL, RET, or NF1 showed positive staining. One VHL associated tumor showed weak diffuse staining, one PGL with no known SDH mutation but clinical features suggesting familial disease was negative, and one showed weak diffuse staining. Completely absent staining is more commonly found with SDHB mutation, whereas weak diffuse staining often occurs with SDHD mutation.

- 46••.van Nederveen FH, Gaal J, Favier J, et al. An immunohistochemical procedure to detect patients with paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma with germline SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD gene mutations: a retrospective and prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:764–771. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70164-0.. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB was done on 220 tumors. SDHB protein expression was absent in all 102 PHEOs/PGLs with an SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD mutation, but was present in all 65 tumors related to multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, von Hippel–Lindau disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1. 47 (89%) of the 53 PHEOs/PGLs with no syndromic germline mutation showed SDHB expression. The sensitivity and specificity of the SDHB immunohistochemistry to detect the presence of an SDH mutation in the prospective series were 100% (95% CI 87–100) and 84% (60–97), respectively.

- 47••.Cascón A, Pita G, Burnichon N, et al. Genetics of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in Spanish patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1701–1705. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2756.. Two hundred thirty-seven nonrelated probands were analyzed for the major susceptibility genes: VHL, RET, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. All syndromic probands were genetically diagnosed with a mutation affecting either RET or VHL. A total of 79.1% and 18.4% of patients presenting with either nonsyndromic familial antecedents or apparently sporadic presentation were found to carry a mutation in one of the susceptibility genes.

- 48••.Erlic Z, Rybicki L, Peczkowska M, et al. Clinical predictors and algorithm for the genetic diagnosis of pheochromocytoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6378–6385. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1237.. Of 989 apparently nonsyndromic PHEOs, 187 (19%) harbored germline mutations. Predictors for presence of mutation were estimated: age <45 years, multiple PHEO, extra-adrenal location, and previous head and neck PGL.

- 49.Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Ahlman H, et al. International Symposium on Pheochromocytoma: Pheochromocytoma: recommendations for clinical practice from the First International Symposium. October 2005. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:92–102. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]