Abstract

Endogenous fluorescence provides morphological, spectral, and lifetime contrast that can indicate disease states in tissues. Previous studies have demonstrated that two-photon autofluorescence microscopy (2PAM) can be used for noninvasive, three-dimensional imaging of epithelial tissues down to approximately 150 μm beneath the skin surface. We report ex-vivo 2PAM images of epithelial tissue from a human tongue biopsy down to 370 μm below the surface. At greater than 320 μm deep, the fluorescence generated outside the focal volume degrades the image contrast to below one. We demonstrate that these imaging depths can be reached with 160 mW of laser power (2-nJ per pulse) from a conventional 80-MHz repetition rate ultrafast laser oscillator. To better understand the maximum imaging depths that we can achieve in epithelial tissues, we studied image contrast as a function of depth in tissue phantoms with a range of relevant optical properties. The phantom data agree well with the estimated contrast decays from time-resolved Monte Carlo simulations and show maximum imaging depths similar to that found in human biopsy results. This work demonstrates that the low staining inhomogeneity (∼20) and large scattering coefficient (∼10 mm−1) associated with conventional 2PAM limit the maximum imaging depth to 3 to 5 mean free scattering lengths deep in epithelial tissue.

Keywords: nonlinear microscopy, two-photon, autofluorescence microscopy, deep imaging, optical biopsy

Introduction

Two-photon autofluorescence microscopy (2PAM) has emerged as a versatile technique for noninvasive three-dimensional imaging of turbid biological samples with subcellular resolution.1, 2, 3, 4 Spectral and morphological information obtained from intravital 2PAM of unstained epithelial tissues has shown promise for diagnosing and monitoring of carcinoma.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Typically, carcinoma originates and is most clearly distinguished from normal tissue at the basal layer, which can be several hundreds of micrometers below the skin surface. Additionally, the quantification of epithelial layer thickness can be used as an indicator of dysplasia and carcinoma.5 Thus, in 2PAM of carcinoma, it is particularly important to understand and extend the maximum achievable imaging depth.

In general, optical imaging depth in skin can be extended by using near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths of 700 to 1300 nm, which are minimally attenuated in biological tissues. Confocal microscopy can image many hundreds of micrometers into epithelial tissue using NIR wavelengths and contrast from scattering or exogenous contrast agents.10, 11 However, the dominant fluorophores naturally present in skin have ultraviolet and blue linear absorption bands.4, 12, 13 Confocal autofluorescence microscopy requires the use of highly scattered excitation and emission light to image these endogenous fluorophores. Though confocal autofluorescence microscopy has been used for imaging shallow regions of epithelial tissue, it has not been demonstrated more than a few tens of micrometers below the surface.14 Two-photon imaging, on the other hand, has three working principles that make it particularly advantageous for deep microscopy of endogenous skin fluorescence: 1. the natural fluorophores in epithelial tissues can be excited nonlinearly with NIR light; 2. fluorescence generation in a sample is inherently confined to the focal volume, enabling three-dimensional sectioning while collecting both ballistic and scattered emission light; and 3. resolution is negligibly degraded from scattering because the fluorescence in the perifocal volume is generated almost entirely from ballistic photons.15, 16

Deep nonlinear imaging can be achieved by maintaining or increasing the excitation intensity delivered to the focal spot as the imaging depth is increased. This can be achieved in biological samples, where the attenuation of NIR photons is dominated by scattering processes, by increasing the pulse energy delivered to the sample surface exponentially with imaging depth, with a length constant of approximately one mean free scattering length (ls). In practice, the excitation intensity is increased at a slightly higher rate to compensate for increased losses from fluorescence collection and the longer path length encountered by large-angle excitation photons.15

Although increasing excitation power with imaging depth can maintain fluorescence generation at arbitrarily large imaging depths, the approximation that two-photon excited fluorescence is generated only within the perifocal volume does not hold beyond ∼3 mean free scattering lengths deep.17 Out-of-focus (background) fluorescence gradually reduces the image contrast.18, 19 The ratio of collected signal fluorescence (Fs) to background fluorescence (Fb) then decays with increasing imaging depth. In cylindrically symmetric tissue, with a distance from the optical axis, r, and an axial distance from the tissue surface, z, this ratio can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where the signal volume, Vs, is the volume of the feature of interest (a fluorescent bead, for instance), the background volume, Vb, is the volume within the sample but outside of the signal volume, ϕ is the collection efficiency, C is the fluorophore concentration, and I is the excitation intensity.

The maximum imaging depth, zm, can be defined as the depth at which the Fs∕Fb ratio falls to one.18 Previous studies have described the maximum imaging depth in units of optical depths, defined as zm∕ls, for homogeneously stained tissue with similar excitation parameters. Theer and Denk found a zm of 3 to 4 scattering lengths when ls = 200 μm using an analytical model.18 On the other hand, Leray et al. found a zm of 5 to 6 optical depths when ls = 350 μm using a Monte Carlo model.19 This difference suggests that zm is dependent on ls. Experimentally, zm has also been measured, but only in stained brain tissue and phantoms with ls ≈ 200 to 350 μm.18, 19, 20 Autofluorescence imaging in epithelial tissues presents a particularly challenging set of optical properties for deep two-photon imaging. First, the scattering length of epithelial tissues is much smaller than those considered in previous studies, typically in the range of 40 to 200 μm. Second, endogenous fluorophores are typically much dimmer and more homogeneously distributed than exogenous fluorophores, resulting in inherently low contrast imaging. Previous 2PAM reports in epithelial tissues have not reached zm, and imaging depths have, to the best of our knowledge, been limited to 80 to 150 μm below the surface.2, 3, 6, 8, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

In this paper, we present 2PAM images of a human tongue biopsy down to and beyond zm. We show that this limit can be reached with a few hundred milliwatts of excitation power available from conventional, high repetition rate oscillators in phantoms with optical properties in the range typically found in epithelial tissues. We describe the gradual contrast decay of 2PAM for increasing imaging depths as a function of the fluorescence staining inhomogeneity and a ratio of integrated intensities. We find that zm∕ls exhibits a logarithmic dependence on ls. Finally, the Fs∕Fb ratio is calculated with time-resolved Monte Carlo simulations and predicted contrast profiles are compared with measurements from tissue phantoms and ex vivo human epithelial tissue.

Methods

2PAM Contrast

In the absence of fluorescence saturation, photobleaching, and sample movement, the effective fluorophore concentration is independent of time. Assuming the concentration of fluorophores within Vs is a constant, Cs, and that the out-of-focus fluorophore concentration is diffuse enough to be approximated by the average fluorophore concentration, Cb, we can remove the concentration terms from the integral in Eq. 1. We define the staining inhomogeneity, χ, as the ratio of the fluorophore concentrations, and R as the ratio of integrated intensities:

| (2) |

| (3) |

We can then express the ratio of signal to background fluorescence as the product of χ and R:

| (4) |

Though our definition for Fs∕Fb is the same as previous reports, our definition of χ and R differ from that described previously.18 Our definition of the staining inhomogeneity relies on the absolute concentrations of fluorophores inside and outside a signal volume and does not depend on the perifocal intensity distribution (i.e., the numerical aperture). Additionally, our R value is defined by the volume of a feature of interest rather than the volume of the focal spot. Our approach has the distinction that the χ value is an intrinsic, system-independent property of the sample that scales linearly with changes in background or signal fluorophore concentration.

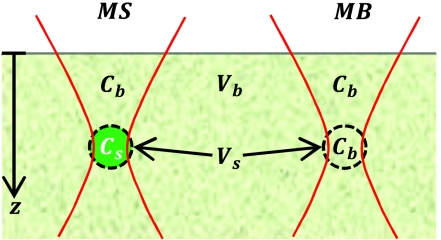

In this paper, we explore the gradual decay of image contrast, Q, versus depth due to out-of-focus fluorescence. We define the contrast in terms of the measured signal (MS) when the focal spot concentrically overlaps with Vs and the measured background (MB) when the focal spot is in a volume at the same imaging depth that produces a relatively weak signal (Fig. 1), such that:

| (5) |

where

| (6) |

| (7) |

Note that our measured background includes a fluorescence contribution from within the defined signal volume. This term becomes important for samples where the fluorophore is relatively homogeneously distributed and there are few regions without fluorophores, which is typically the case for 2PAM of epithelial tissues. Rearranging Eqs. 5, 6, 7 and using the definitions in Eqs. 2, 3, we can express the contrast as a function of χ and R:

| (8) |

This relation shows that the contrast approaches zero as the staining inhomogeneity approaches one (i.e., a uniformly stained sample), or as R approaches zero. If the fluorophore concentration is zero in the focal volume for the MB measurement, Q is exactly equal to Fs∕Fb. In the more general case, with some fluorescent signal present in the focal volume of the MB measurement, Q becomes approximately equal to Fs∕Fb for small values of R. In this paper, we define zm as the depth at which the contrast falls to one, which is approximately equal to the maximum imaging depth defined by Theer and Denk.18

Figure 1.

Diagram of the parameters used in quantifying the contrast in 2PAM. The signal and background volumes (Vs and Vb, respectively) and signal and background fluorophore concentrations (Cs and Cb, respectively) are indicated. MS is defined as the fluorescence detected when the geometric focal point of the excitation light is at the center of Vs. MB is defined as the fluorescence detected when the excitation is focused at the same imaging depth as MS, but outside of the feature of interest.

2PAM System

We built a two-photon microscope specifically designed for deep tissue autofluorescence imaging. An 80-MHz repetition rate, Ti:Saphire laser oscillator (Spectra Physics, Mai Tai) generated the excitation pulses with energies of up to 10 nJ. We used 760-nm excitation wavelength because it yielded the brightest autofluorescence signal with minimal excitation light bleed-through in our system. Two half-waveplate∕polarizing beam cube pairs attenuated the excitation beam and a pair of galvanometer scanning mirrors (Cambridge Technologies, 6215h) scanned the laser into an upright microscope. We used a high numerical aperture (NA), water dipping objective with a large field of view and a 2-mm working distance (0.95∕20x Olympus XLUMPFL). The large field of view is especially important for high collection efficiency at large imaging depths.27 The physical radii of the back aperture, rBA, and front aperture, rFA, of this objective are 8.5 and 2 mm, respectively. The measured beam 1∕e2 radius of the excitation beam, wBA, was 6 mm at the objective back aperture, giving a fill factor of 0.7. The transmission of 760-nm light was measured to be 70% by measuring the laser power before and after the objective with a power meter.

We optimized the collection optics for maximum collection of emission photons from the diffusive regime using Zemax-EE (2009 Version), similar to a previous approach.28 Excess stray and scattered excitation light were filtered through two low pass filters (3-mm thick BG-39, Schott Glass and FF01–750, Semrock). We used a high-sensitivity, cooled, GaAsP photomultiplier tube (PMT) module (Hamamatsu, H7422–40) as our detector. The current from the PMT was sent through a 1-MHz bandwidth transimpedance amplifier (Stanford Research Systems SR570) and sampled at 1 MHz with 12-bit digitization on a data acquisition card (National Instruments PCI-6115). We used a modified version of MPScan software29 to control the laser power and scanning mirrors, and acquire 512×512 pixel images at 3 frames∕s. All images presented and analyzed in this paper are the average of 8 frames to minimize other sources of noise. In biopsy and phantom measurements, we increased the excitation power manually with depth to maintain an approximately constant level of collected signal at levels just below the saturation limit of the system.

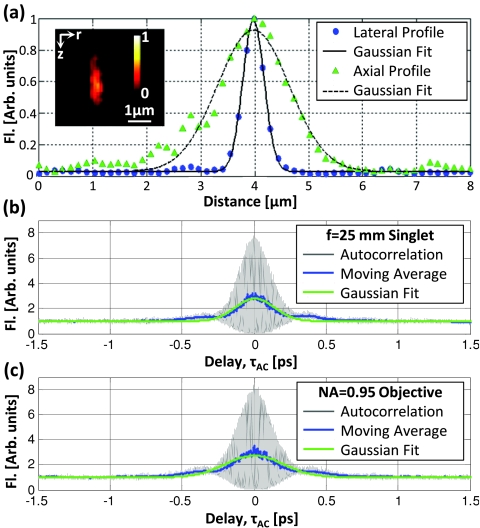

We characterized the spatial intensity distribution of the excitation light at the focal volume by measuring the intensity-squared point spread function (IPSF2) of our system with 100-nm diameter fluorescent beads embedded in agar. A representative IPSF2 measurement is shown in Fig. 2a. We found lateral and axial FWHMs of rFWHM = 460±60 nm and zFWHM = 1760±130 nm (mean ± standard deviation), respectively, by fitting Gaussian functions to the profiles drawn through the centroids of 20 beads. These values are approximately 50% larger than theoretical values expected with a diffraction-limited spot from a 0.95 NA water dipping objective,30 and closer to what would be expected from diffraction-limited focusing from an NA of 0.75. The difference between measured and diffraction-limited IPSF2 is too large to be accounted for by our underfilling of the back aperture,31, 32 and is likely due to lens aberrations at NIR wavelengths. Similarly large IPSF2 have been previously reported from this objective.27, 33, 34 We found that the IPSF2 was independent of imaging depth through the full working distance of the lens (2 mm) in a sample of 100-nm fluorescent beads embedded in an agar gel. The constant spot size indicates that specimen-induced aberrations negligibly affect the shape of the intensity distribution in the perifocal volume in agar phantoms, which is consistent with other studies.15, 16, 35

Figure 2.

A representative lateral, r, and axial, z, ISPF2 from a 100-nm fluorescent bead (a), indicating average lateral and axial FWHMs of 460 and 1760 nm, respectively. The inset shows the two-photon image of a typical bead in the rz-plane. Autocorrelation measurements with a 1 in. singlet lens (b) and with a 20x∕0.95 objective lens (c) indicated duration FWHMs of 185 ± 10 and 270 ± 10 fs, respectively. Double-headed arrows in each plot indicate where the FWHM was measured. Fluorescent signal (Fl) is normalized to 1 at the center of the bead in (a), and at 1.5 ps in (b) and (c).

We characterized the temporal intensity distribution at the focal plane by incorporating a Michelson interferometer with a variable delay arm in the excitation path, and measuring the autocorrelation function of the focused excitation beam within a sample of 25-μM fluorescein.36, 37 We calculated the pulse duration at the imaging plane from autocorrelations measured with the objective as a focusing lens and also when replacing the objective lens with a 1 in. diameter singlet lens with a 1 in. focal length. These two measurements [Figs. 2b, 2c] allow us to estimate the group delay dispersion (GDD) of the objective lens. We recorded the FWHM of a Gaussian fit, , to the moving average of our interferometric autocorrelation function over five measurements in each configuration. Assuming the original pulse shape is a Gaussian, the FWHM of the original pulse shape, , is related to the autocorrelation trace by: , we estimate the pulse duration at the sample plane to be 185 ± 8 fs with the singlet lens and 270 ± 10 fs with the 20x∕0.95 objective lens. Using the measured spectral bandwidth of 7.5-nm FWHM, and assuming a modest GDD of 250 fs2 from the 1 in. singlet lens, we estimate that the GDD of our objective lens is approximately 4300 fs2 at 760 nm. This GDD is significantly larger than reports of other similar NA objectives,37 but not unexpected, given the long physical length of the lens (75-mm long).

Monte Carlo Model

We used two independent Monte Carlo simulations to find the spatiotemporal distribution of the squared excitation intensity, I2(r, z, t), and the spatial dependence of the collection efficiency, ϕ(r, z). These results were then combined using Eqs. 3, 8 to calculate R and determine image contrast, Q, as a function of imaging depth for a variety of sample and system parameters.

For the excitation simulation, the trajectories of photon packets were traced through a cylindrically symmetric three-dimensional grid with coordinates for depth z, radius r, and time t. All simulations used a Henyey–Greenstein scattering phase function with a scattering anisotropy, g, set to 0.85, which is the expected value from Mie theory for 760 nm light interacting with 1-μm diameter polystyrene spheres.38 We used an absorption mean free path length of 5 mm in all simulations.

We modeled the focusing of the excitation light using the hyperbolic focusing method described by Tycho et al.39 By skewing the initial trajectory of each photon off of a z-r plane by an angle depending on r, a focused Gaussian beam is exactly reconstructed in all three dimensions with photons that travel in straight paths. In a Gaussian beam focused at an imaging depth of z0, the lateral 1∕e2 beam radius as a function of depth, w(z), is defined by two parameters: the lateral 1∕e2 beam waist at the focal plane (w0) and the Rayleigh range (zR):

| (9) |

The intensity distribution can then be defined as:

| (10) |

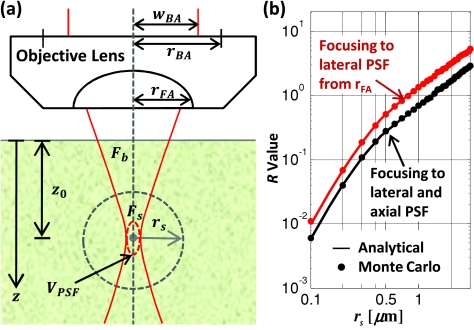

We measured three parameters experimentally that characterize the excitation light distribution: the beam profile at the back aperture, the axial extent of the focal spot, and the lateral extent of the focal spot. With only two parameters that define the shape of a Gaussian focus, all three measurements of our excitation beam shape cannot be simultaneously modeled. Since the purpose of this model is to simulate the ratio of in-focus to out-of-focus fluorescence, it is important that the simulated beam shape matches experimental observations both close and far from the focal plane. Therefore we choose w0 so that the lateral Gaussian shape is correctly simulated at the focal plane, and zR such that the lateral Gaussian shape is correctly simulated at the front aperture of the objective.

Excitation photons were launched to a w0 equal to times the 1∕e2 radius of the measured IPSF2 at the focal plane. To find the zR to match the profile of the excitation beam at the front aperture, we assume that the fill factor at the back aperture of the objective is linearly transferred to the front aperture of the objective—that is that wBA∕rBA = wFA∕rFA [Fig. 3a]. The resulting parameters describing the Gaussian distribution of the excitation photons are:

| (11) |

In our simulations, w0 = 552 nm and zR = 0.78 μm for working distance of WD = 2 mm and rfa = 2.04 mm. The FWHM of the axial dimension of the two-photon excited focal spot is linearly related to the Rayleigh range by zFWHM = 1.29·zR = 1.06 μm. Thus the axial resolution of our simulation is 40% smaller than the measured resolution. The effect of this discrepancy in calculating the R value is shown in Fig. 3b. For a transparent medium, the R value calculated by these parameters is approximately twice that if the IPSF2 is exactly simulated. In our application, we are studying the change in signal when imaging many mean free scattering lengths deep in turbid media. Imaging five mean free scattering lengths deep, for instance, we will see that the signal decays by over 4 orders of magnitude. So this inaccuracy in R value has a small effect on calculating the maximum imaging depth.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic of parameters used in modeling signal and background fluorescence generation for a focused Gaussian beam in turbid media. (b) The ratio of signal fluorescence to background fluorescence in a homogeneously stained, R, is a function of the signal volume size, defined here as the volume of a sphere with radius rs. The lines shown are exact analytical solutions and solid points are Monte Carlo results for focusing to a spot size equal to the measured ISPF2 of our system (blue line), and for focusing to the conditions used in our model (red line) in the limiting case where the scattering and absorption of the media are zero.

We obtained the temporal impulse response of the system by setting initial photon times such that ballistic photons intercept the focal plane at exactly the same instant. The intensity distribution was determined by convolving the impulse response with the Gaussian pulse envelope measured in Sec. 2B. Finally, the fluorescence generated per voxel was calculated by multiplying the integrated intensity squared by the volume of the voxel.

A second, time-independent, Monte Carlo simulation was used to model the effect of heterogeneous collection efficiency on maximum imaging depth. We implemented the approach outlined by Beaurepaire and Mertz, where the maximum radius and exiting angle of a photon escaping the tissue are coupled to conserve beam étendue.40 We used an effective field of view radius of rf = 1 mm.27 We created a set of collection efficiency maps by launching photons with an isotropic initial angle distribution and a wavelength of 515 nm. The ratio of scattering length at 760 and 515 nm found to be 1.7 by Mie simulations for 1-μm polystyrene beads (see Sec. 2E). Thus, for each excitation simulation set, we then used a scattering length of to create a matching collection efficiency map. We used an of 2 mm. To calculate R, the fluorescence grid created from the excitation simulation was integrated over time and every element was multiplied by an interpolated value from the spatial collection efficiency grid.

Analytical Model

We applied the analytical model developed by Theer and Denk to calculate the fluorescence distributions for different optical system and sample parameters.41 In short, we consider the ballistic and scattered light distributions in turbid media independently and then combine the resulting intensities to calculate total fluorescence. The intensity from ballistic photons assumes an incident beam with Gaussian spatial and temporal distributions. The scattered light is modeled using a small angle approximation and statistical methods to calculate an effective temporal and transverse spatial beam width. We used an NA of 0.75, which produces a similar spot size to that measured from our IPSF2. All other parameters used in the analytical model were the same as those used in the Monte Carlo model.

Tissue Phantom Preparation

To measure the experimental contrast decay of two-photon imaging in a turbid media, we prepared 12 scattering agar phantoms with a range of optical properties similar to what is typically observed in epithelial tissues. Low melting point agarose (1.0%, Sigma) was prepared with 0.95-μm diameter polystyrene beads (Bangs Labs, PS03N) to vary scattering coefficient, 1-μm diameter fluorescent polystyrene beads (Invitrogen F-8823) to provide features for contrast measurements, and fluorescein (Fluka 46955) to control staining inhomogeneity. Polystyrene beads were ultrasonicated for 30 min to reduce aggregations before they were mixed into the agar phantoms. To increase the two-photon action cross-section of fluorescein, we mixed the agar solution with 2% pH 12 buffer. Polystyrene concentrations of 1.7×1010, 0.9×1010, and 0.6×1010 particles per mL provided scattering mean free paths of 40, 80, and 120 μm at 760 nm excitation, and 23, 46, and 69 μm at 515 nm emission, respectively. We determined the scattering coefficient with a Mie calculation using polystyrene sphere and agar gel refractive indices of 1.58 and 1.33, respectively.42 To verify the scattering lengths of our polystyrene solution matched Mie predictions, we measured attenuation of collimated 760-nm light through dilute solutions of polystyrene beads in a cuvette. Fluorescent beads were added at a constant concentration of 3.5×108 particles per mL in all phantoms.

We added increasing amounts of fluorescein to get final concentrations of 0, 4, 10, and 25 μM for each scattering length tested, creating a total of 12 phantoms. This approach allows the formation of phantoms with low staining inhomogeneities without an increase in scattering coefficient that would result from adding high concentrations of fluorescent polystyrene beads. An additional benefit of using this method is that we can increase the background fluorescence immediately adjacent to the fluorescent beads. In contrast, previous studies that varied fluorescent bead concentration could control the fluorescence only in volumes many micrometers away from the signal volume.18 Thus our approach provides a more appropriate model for studying autofluorescence contrast decay, where the local staining inhomogeneity changes rapidly in short distances from the nucleus to cytoplasm to extracellular matrix. The disadvantage of this approach is that the out-of-focus background fluorescence cannot be measured directly because there is no region without some fluorescent signal—when the focal spot does not overlap with a fluorescent bead, the measured background still includes some contribution from the fluorescein in the focal volume.

We obtained lateral phantom images at 1 μm depth increments from the surface to the depth where the image contrast fell to approximately 0.1. The contrast for each of the 16 phantoms was analyzed using an automated bead-finding script written in MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc.). The MS for each bead was then calculated as the average of the maximum 4 voxels (150×150×1000 nm∕voxel) within each region and the MB was calculated as the average pixel value of the nonconnected regions at the depth determined by the centroid of the bead.

Biopsy Preparation

Human oral cavity biopsies were obtained from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center as part of an ongoing project for two-photon diagnosis of oral malignancies. The study was reviewed and approved by the internal review boards at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and the University of Texas at Austin. Biopsies were excised from suspicious regions and contralateral normal tissue in the oral cavity and submitted for histopathology. We present two-photon images from the normal biopsy in this paper. The biopsy was approximately 3 mm in diameter and 5-mm thick, delivered in chilled culture media (Phenol Red-free DMEM High, Fisher Scientific), and imaged within 6 h of excision. The biopsy was stabilized on a Petri dish with low melting point agar and imaged at room temperature in a culture media bath.

Results and Discussion

Monte Carlo Simulations

To validate our Monte Carlo model, we verified that for a transparent tissue, in the absence of scattering and absorption, the expected Gaussian profile is maintained from the sample surface to the full working distance of the lens. The value of R calculated from Monte Carlo simulations and the exact solution are shown in good agreement in Fig. 3b. Select Monte Carlo simulations were rerun with half the chosen grid spacings of r, z, and t (and corresponding eight times more grid elements for constant grid size), to verify the grid spacing was sufficiently small to capture the spatiotemporal changes in fluence. No significant changes were found in R calculations for smaller grid spacings, indicating the grid choice was sufficiently small to capture dynamic and spatial changes in intensity distribution. Finally, we verified that focal plane fluorescence generation scales inversely with pulse duration.

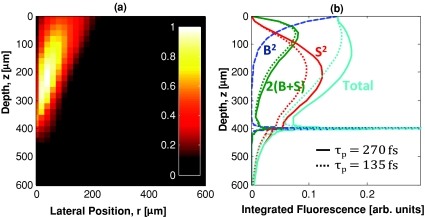

We used our Monte Carlo model to calculate R as a function of depth for each phantom. For these calculations, Vs was set to the volume of the 1 μm diameter fluorescent beads which provide the signal in the phantoms. Figure 4 presents the fluorescence distribution for imaging 400 μm deep in a homogeneously labeled sample with an ls of 80 μm. In this case, the collected background fluorescence overwhelms the signal fluorescence by approximately 30 times. When the fluorescence is integrated circumferentially, we observe that the cumulative background fluorescence generation peaks slightly off-axis because the off-axis fluorescence is generated in larger volumes [Fig. 4a]. Finally, integration of this fluorescence radially shows that the total fluorescence generation at each transverse plane is relatively constant through the first two ls, and monotonically decreasing at larger depths [Fig. 4b].

Figure 4.

Monte Carlo simulations are used to calculate the expected fluorescence distribution for an imaging depth of 400 μm in a sample with a 460-nm FWHM lateral spot size, τp = 270 fs, ls = 80 μm, and g = 0.85. These parameters resulted in an R value of 1∕30. (a) shows the lateral and axial distribution of the circumferentially integrated background fluorescence distribution. In this case, most of the background fluorescence comes from above the imaging plane and within 200 μm of the optical axis. (b) shows the contributions from ballistic (B2), scattered (S2), and combined 2(B+S) photons separately. The total fluorescence generation per transverse slice is relatively constant through the first three ls deep. The solid and dotted lines represent simulations with excitation pulse durations of 270 and 135 fs, respectively. (a) is normalized so that the maximum out-of-focus fluorescence is one, (b) is normalized so the maximum fluorescence is one.

The contributions from ballistic (B) and scattered (S) fluence were separated by tagging scattered photons in the Monte Carlo simulations [Fig. 4b]. The fluorescence generation at each voxel will then be proportional to (S+B)2. These results can provide some insight into how certain parameters affect the generation of background fluorescence. For instance, previous studies have shown that the R value can be increased by using shorter pulses.18, 19 Looking at the individual components, as the pulse duration is decreased, it is entirely the scattered (S2) and combined (2BS) terms that show a relative reduction in contribution of background fluorescence. Scattering can be thought of as a source of temporal dispersion from the sample on the scattered fluence. Furthermore, as the pulse duration is decreased, the dispersion from scattering reduces the fluorescence generated from scattered photons relative to the peak fluorescence generated within the focal volume, resulting in an increase in R for shorter pulse durations.

Though high collection efficiency is important for reaching large imaging depth with limited excitation power, we found that heterogeneous collection efficiency generally had a small effect on our calculations of R. In the ls = 80-μm simulation (), the collection efficiency only reduced R by 12% at z0 = 400 μm, and by 60% at z0 = 800 μm. The radial dependence of the collection efficiency had an especially weak effect on R, since the majority of the fluorescence generated in the excitation simulations was within 200 μm of the optical axis.

Phantom Imaging

For all phantoms, we had sufficient power to reach contrast levels below one. Typically, excitation powers smaller than 1 mW were sufficient to image at the surface, while several hundreds of megawatts were required at the largest depths. For the phantom with ls = 80 μm and χ = 300, for example, the excitation power was increased from 0.7 mW at the sample surface to 483 mW at the sample surface when imaging 510-μm deep. We identified an average of 190 beads per 77×77×100 μm3 field of view in each of the 12 phantoms using the automated bead-finding script. This number of beads corresponds to a bead concentration of 3.2×108 beads per mL, slightly less than the expected value of 3.5×108 beads per mL.

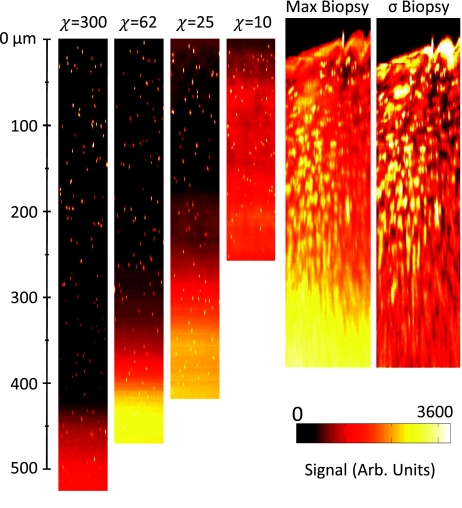

Figure 5 shows XZ images of the ls = 80 μm phantom set for different staining inhomogeneities. Each XZ reconstruction is created from a maximum projection through 15 μm (45 pixels) of Y. The accompanied biopsy images are discussed in Sec. 3E. We estimated the staining inhomogeneity of phantoms using the measured contrast at the surface of each phantom and the R values found from Monte Carlo simulations. The R value since it only changes slightly for shallow imaging depths in our Monte Carlo model—a decrease from 0.51 at the surface to approximately 0.46 at one ls deep. Substituting an R value of 0.5 in Eq. 8, the staining inhomogeneity, χ, becomes approximately equal to three times the measured contrast at shallow depths, for large values of χ. Using this approximation, we estimate the average staining inhomogeneities to be χ = 300, 62, 25, and 10, by using the average contrast from beads identified within the first 20 to 40 μm of the three phantoms at each staining inhomogeneity.

Figure 5.

Comparison of XZ images of phantoms with constant scattering length of ls = 80 μm for increasing staining inhomogeneity, χ, and a human tongue biopsy. Phantom cross sections are maximum projections through 15 μm of Y. Biopsy cross-sections shown are a maximum projection “max Biopsy” and a standard deviation projection “σ Biopsy” through 15 μm of Y. The standard deviation projection is normalized so that the maximum value is white.

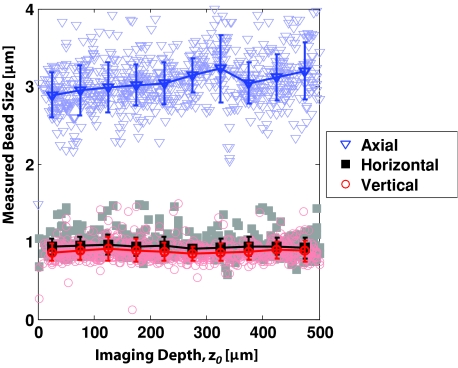

The measured bead size remained constant with imaging depth for all phantoms. Figure 6 shows a representative case for the measured bead size versus depth for ls = 80 μm, χ = 300 phantom. We determined the FWHMs of bead sizes by fitting a Gaussian function through the centroid of each bead found in the phantom. We found a slightly smaller bead sizes in the direction of our fast moving mirror (horizontal), indicating a slightly smaller resolution in that direction, possibly due to a slight ellipticity of the beam shape at the back aperture of the objective. The apparent axial resolution measured from the 1-μm beads was noticeably larger than that measured from the IPSF2 with 100-nm beads. We attribute this increased measured axial resolution to sparse sampling (axial spacing between images was 1 μm) and long times between imaging the top and bottom of the beads (the time elapsed between the first image and the last image 3-μm apart was approximately 10 s). Nonetheless, the constant lateral and axial size of the measured beads does indicate minimal specimen-induced aberrations with increasing imaging depth. This result is in contrast to studies without index matching, where spherical aberrations are commonly observed.43, 44

Figure 6.

Measured sizes of 1 μm diameter fluorescent beads versus depth for ls = 80 μm, χ = 300 phantom in the lateral and axial directions. The trend and error bars are calculated by the mean and standard deviations of sizes obtained by binning the beads at 50-μm depth increments. We observed no significant increase in bead size and, thus, in system resolution with increasing imaging depth in any of our phantoms.

Fluorescence Decay

We measured the decay of the signal, background, and total fluorescence with increasing imaging depth in our 12 phantoms. By increasing the excitation power exponentially with imaging depth and normalizing the measured signal at each imaging depth by the expected quadratic increase with the excitation power, P(z = 0)2∕P(z = z0)2, we could accurately measure fluorescence decays far beyond the limited dynamic range of our detection system.

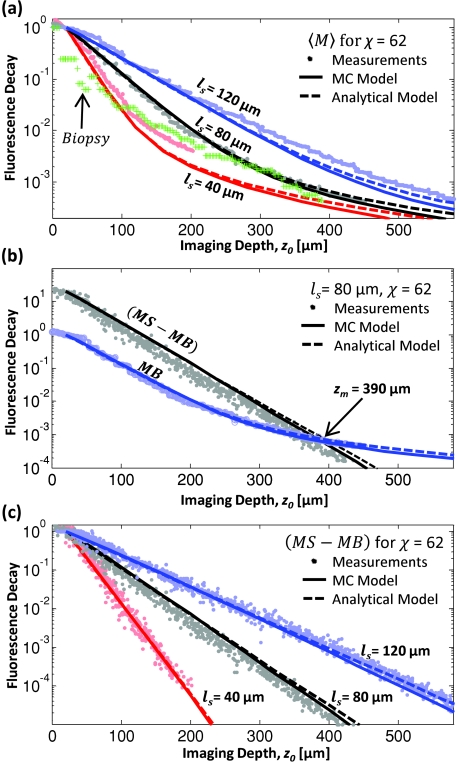

Figure 7 shows the measured and calculated fluorescence decays of the three χ = 62 phantoms. Looking at the χ = 62, ls = 80 μm phantom, Fig. 7a shows the decays of the average value of the measured background at each imaging plane (MB), the measured signal for each fluorescent bead (MS), and the difference (MS-MB). Note that the slopes of the (MS-MB) and MB decays are approximately equal for imaging depths down to three mean free scattering lengths. This result suggests that the contrast, defined as the ratio of (MS-MB) to MB, is relatively constant for shallow depths. At larger imaging depths (z > 4ls) the measured signal, which decays exponentially, is overcome by the background, which decays with .18 Comparing the fluorescence decay in phantoms with different scattering lengths, we found good agreement between the measured data and the Monte Carlo predictions [Figs. 7b, 7c ]. The decay of the fluorescent signal from the biopsy is discussed in Sec. 3E.

Figure 7.

Plots of normalized fluorescence decays versus imaging depth for constant staining inhomogeneity (χ = 62). Points are data from phantom measurements and lines are the decays predicted by our Monte Carlo simulation with homogeneous (solid lines) and heterogeneous (dashed lines) collection efficiency. (a) The average fluorescence decay, 〈M〉, represents the average pixel value of a 512×512 pixel image recorded at each imaging depth. For comparison, the average fluorescence decay of the biopsy is also shown. (b) Examining relative decays for the MS, MB, and difference (MS-MB) versus depth for the χ = 62, ls = 80 μm phantom, we found a maximum imaging depth of zm = 390 μm. (c) The background-subtracted fluorescence decay exhibits exponential decay for the entire measured range. Monte Carlo simulations agree well with experiments for homogeneous collection efficiency (dashed lines) and heterogeneous collection efficiency (solid lines). Decays are normalized to one at 20-μm deep in (a) and (c). In (b), the background is normalized to one at 20-μm deep.

The effect of heterogeneous collection efficiency has little effect on the calculated decay curves, indicated by the overlap of the Monte Carlo results for shallow and moderate imaging depths. We also found that changing the staining inhomogeneity had little effect on the observed fluorescence decay rate, as summarized in Table 1. As expected, the staining inhomogeneity had the effect of raising or lowering the initial MB value relative to the MS values.

Table 1.

Summary of fluorescence signal decay length constants from exponential fits to measured phantom data (from z0 = 0 to 3ls) and predicted in Monte Carlo data, with and without including the effect of heterogeneous collection efficiency.

| Measured length constants, |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phantom measurements |

Monte Carlo data |

|||||

| ls (μm) | χ = 10 | χ = 25 | χ = 62 | χ = 300 | Homogeneous collection | Heterogeneous collection |

| 40 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| 80 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.44 |

| 120 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.43 |

Table 1 summarizes the measured length constants, , obtained from the exponential decay rates of the background-subtracted fluorescence in each phantom, and the corresponding decay constants predicted by Monte Carlo models. In all phantoms, the actual scattering length could be estimated to within 10% accuracy by using the approximation: . This result is reasonable considering a previous report, which found a factor of 2.5 relation between and ls using an NA of 1.2.15

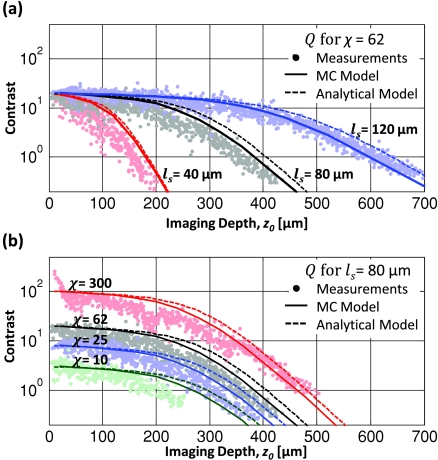

Contrast Decay

The measured contrast decay from tissue phantoms showed similar trends to those predicted by Monte Carlo and analytical models (Fig. 8). The Monte Carlo model matches the analytical model relatively well for the higher χ values tested. For the χ = 10 phantom, the measurements demonstrate shorter zm than predicted, likely due to the high concentration of fluorescein in these phantoms beginning to absorb significant amounts of emission (the “inner filter” effect). If the absorption mean free path length is known at the emission wavelength, this effect could be accounted for using a shorter mean free absorption length in our collection efficiency calculations.

Figure 8.

Contrast decays of phantoms with (a) constant staining inhomogeneity and (b) constant scattering length. Monte Carlo simulations (solid lines) agree well with the analytical model (dashed lines) and the phantom contrast measurements (solid dots). Both models slightly overestimate the maximum imaging depth, increasingly at lower staining inhomogeneities.

We observed that for the χ = 300 phantoms, the contrast was higher than the expected values at shallow depths [Fig. 8b]. We attribute this large contrast to an effective increase in χ at shallow depths. Because no fluorescein was added in this set of phantoms, the staining inhomogeneity was determined by the influence of background fluorescent beads. For the shallowest beads, there are no background fluorescent beads directly above them, effectively increasing their apparent staining inhomogeneity. For deeper beads, the fluorescent beads that are present above the imaging plane produce background fluorescence.

Human Biopsy Imaging

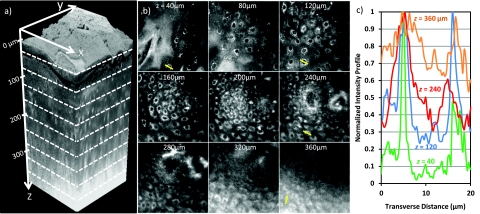

Figure 9 presents a summary of the 200 autofluorescence images collected at 2-μm depth increments from a biopsy of healthy human tongue tissue. The water-dipping objective allowed us to visualize the natural surface roughness of the tissue, which plays a role in collection efficiency40 [Fig. 9a]. We defined the surface (z = 0 μm) as the depth at which half of the field of view had signal. We increased the excitation power delivered to the tissue surface gradually from 3 mW at the surface to 30 mW at 170-μm deep. At larger imaging depths, we could maintain constant signal detected while increasing the excitation power less rapidly. We used a maximum of 160 mW of excitation power delivered to the sample surface when imaging 380-μm deep.

Figure 9.

(a) Three-dimensional rendering of a sequence of 200 lateral 2PAF images acquired from healthy human tongue biopsy. (b) Selection of lateral images from an imaging depth of 40 to 360 μm. Field of view in all lateral images is 170 μm. (c) Normalized signal profile from manually identified cells at imaging depths of 40, 120, 240, and 360 μm. Profiles are taken from lateral lines indicated in (b).

Lateral images show subcellular resolution and cellular morphology with bright cytoplasm to dark nucleus contrast [Fig. 9b]. Contrast is presumably due to high concentrations of NADH, NAD, and FAD in the cytoplasm, which have been shown to be the dominant endogenous fluorophores in confocal autofluorescence imaging of cervical and oral epithelial tissues,45, 46 and are efficiently excited in 2PAM at 760-nm excitation.4 We found especially high signal levels from the stratum corneum, which, based on our Monte Carlo model, would strongly contribute to the out-of-focus fluorescence found at large imaging depths.

A maximum XZ projection through 15 μm of Y shows that at large depths, bright pixels in the background substantially degrade the contrast beyond 300 μm [Fig. 5]. A normalized standard deviation projection through 15 μm of Y gives values similar to the measured contrast—it shows bright regions where there are large changes in pixel values. At shallow depths, this projection shows large values where there is variation between the bright cytoplasm signal and dark nuclei. At large depths, the increase in low-spatial-frequency, out-of-focus background fluorescence reduces the lateral variation in signal, and the corresponding standard deviation along Y decreases.

We examined the total fluorescence decay with imaging depth to estimate the scattering coefficient of the biopsy. Though fluorescence decay accurately predicted the scattering coefficient in phantoms, extending this method to the biopsy can be complicated by several effects. 1. The scattering length and fluorophore concentrations are likely to change with depth. Previous studies have observed brighter signal coming from the stratum corneum and basal membrane than at the intermediate epithelial layers.46, 47 2. As the excised tissue dies, the autofluorescence signal levels gradually decay with time. We observed that the superficial regions of the tissue begin losing fluorescence signal more rapidly than the interior regions, creating a time-dependent change in relative fluorescence density. 3. Specimen induced aberrations typically become more severe with increasing imaging depths,48 and would result in a higher apparent rate of fluorescence decay. Though we verified aberrations played a minimal role in degradation of signal in the phantom, without a constant-size point source in our biopsy, we were unable to monitor our excitation spot size with depth in the biopsy. Nevertheless, we can obtain an estimate of the biopsy scattering coefficient by comparing our measured biopsy fluorescence decay to phantom experiments [Fig. 7a]. We fit an exponential curve to the first 200 μm of fluorescence decay obtained from the biopsy and found a length constant of 39 μm, corresponding to a scattering length of 89 μm, assuming . At larger depths, the fluorescence decayed less rapidly, showing a similar slope to the ls = 120-μm phantom.

Figure 9c presents typical contrast levels obtained at different imaging depths. We examined the contrast in line profiles drawn through manually identified epithelial cells marked by the lines drawn in the lateral images displayed in Fig. 9b. At 40-μm deep, the brightest signal from the cytoplasm is approximately 20 to 40 times larger than the minimum signal from within the nucleus, while the average signal from the cytoplasm is approximately 5 to 10 times the average signal from the nucleus [Fig. 9c]. Using averaged signal and background as contrast, and employing the same method used with the phantoms, we estimate the χ of the biopsy to be 15 to 30. The contrast falls to 1 in our biopsy around 320 μm below the tissue surface, approximately 3 to 4 mean free scattering lengths deep.

Fluorescence Saturation and Photobleaching

The analysis presented in this paper has assumed that the intensity ranges used in our experiments are low enough to assume negligible fluorescence saturation and photobleaching—that is, that the fluorescence generation is quadratically dependent on the excitation intensity and is time-independent. However, at high intensities, these assumptions no longer hold. We performed a series of tests to verify that we do not experience any saturation and photobleaching in our experiments.

The average powers used for surface imaging in the phantoms and biopsy were 1 to 3 mW, respectively. Using our measured spot size and pulse duration, these powers correspond to peak intensities of 5 to 15 GW∕cm2 generated at the focal spot. These intensities and the estimated ∼320 overlapping pulses per spot used in our study, are well below imaging conditions found in the literature to have no affect cell viability, as summarized by Hoy et al.49 Furthermore, we found in phantom experiments and Monte Carlo simulations that the rate of power increase necessary for maintaining constant fluorescence detected is close to that required to deliver constant fluence to the focal point. Though when imaging deep inside scattering media, average powers greater than 100 mW are delivered to the sample surface, it is unlikely that the fluence delivered to the imaging plane at large depths is significantly greater than that delivered to the imaging plane when imaging the sample surface.

Fluorescence saturation can broaden the point spread function, as fluorophores in the highest intensity regions no longer generate a greater emission signal than fluorophores further away. The resulting decrease in resolution has been previously demonstrated, but is expected to have a significant effect only under a combination of high intensities and especially large two-photon action cross-section50 (>1000 GM cross-section at 1 mW of excitation power delivered to the imaging plane, where 1 GM unit equals 10−50 cm4 s). Our observation of constant measured bead size with increasing imaging depth indicates a negligible influence of fluorescence saturation in our phantom experiments [Fig. 6]. To test for fluorescence saturation in our biopsy experiments, we verified that our detected signal scales quadratically with excitation at select imaging depths. We measured power dependencies of 1.94, 2.00, 1.97, and 1.99 at increasing imaging depths of z0 = 290, 300, 326, and 356 μm, respectively. In phantoms, we also observed that the signal from the identified beads scaled to the power of 1.98±0.05 at each 100 μm imaging depth increment.

We also tested for the presence of photobleaching in 2PAM of the biopsy by measuring the ratio of the average signal of the first and last image taken at every image plane. Each imaging plane was raster scanned 8 times at 3 frames per second. We found an average ratio of 1.00 ± 0.02 for the biopsy, and no trend for photobleaching at larger imaging depths. In conclusion, we expect that fluorescence saturation and photobleaching did not appreciably influence the results presented herein.

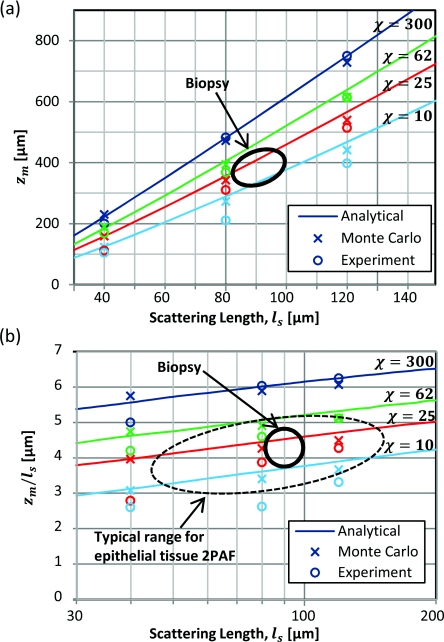

Maximum Imaging Depth

Figure 10a summarizes the maximum imaging depth found in phantom experiments, Monte Carlo simulations, and the analytical model for samples with different scattering lengths and staining inhomogeneities. We found reasonable agreement between the three approaches, with experiments matching the models slightly better for longer scattering lengths and higher staining inhomogeneities. This difference is likely due to the increasing influence of small heterogeneities in our shorter scattering length phantoms, such as spatial variations in fluorescein and polystyrene bead concentrations. The Monte Carlo model showed a slightly weaker dependence of maximum imaging depth on scattering length, partially due to the effect of inhomogeneous collection efficiency.

Figure 10.

(a) The maximum imaging depth determined by the depth at which Q = 1. (b) Expressing the maximum imaging depth in terms of scattering mean free paths, we observed a linear dependence of maximum imaging depth on log(ls). Data are plotted from phantom measurements, as well as analytical and Monte Carlo models, with homogeneous collection, and real heterogeneous collection.

The approximate position of our biopsy is also indicated, based on extraction of optical properties from biopsy images. The maximum imaging depth achieved in the biopsy was 320 μm, which was approximately 20% less than that expected from phantoms with similar ls and χ. This difference is likely due to greater specimen-induced aberrations in biopsy imaging.

Normalizing the maximum imaging depth by , we find a logarithmic dependence on ls [Fig. 10b]. Though this is a reasonable approximation for small fractional changes in ls, it leads to an overestimate of maximum imaging depth by 1 scattering length when extrapolating maximum imaging depths found in samples with ls = 200 μm to samples with an ls of 40 μm. The origin of the dependence of zm on ls is that as the distances are scaled down by ls, the photons responsible for the background fluorescence are confined to smaller volumes while the photons generating focal volume signal pass through a constant size signal volume.

Conclusions

With recent technological advances in 2PAM, including the development of 2PAM systems more relevant for in vivo optical biopsy,49, 51, 52 it is increasingly important to understand how out-of-focus background fluorescence affects image contrast and ultimately limits imaging depth. In this paper, we presented experimental data and a computation model that describes the gradual contrast decay of two-photon fluorescence imaging with increasing imaging depth for samples with a variety of scattering lengths and staining inhomogeneities relevant to 2PAM of epithelial tissues. We found the maximum imaging depth, even when normalized by scattering length, is significantly smaller in epithelial tissue than those observed brain tissue, due to a dependence on maximum imaging depth on scattering length and very low staining inhomogeneities. Based on this analysis, we expect that given a range of optical properties typical of epithelial tissue, the 2PAM image contrast decays to 1 at imaging depths of 3 to 5 ls, or, approximately 150 to 400 μm.

In this paper, we only considered conventional 2PAM. However, more sophisticated approaches could extend 2PAM imaging depth and contrast by temporal focusing,53, 54 differential aberration imaging,55 optical clearing,56 and∕or spatial filtering.18 It would conceivably also be possible to extend imaging depth by using longer wavelength excitation light57 to probe dimmer intrinsic fluorophores that have higher wavelength absorption bands, or by using higher order excitation (e.g., three-photon excited fluorescence).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Anne Gillenwater and Leslie Zachariah from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center for providing the tissue biopsy. We also thank Dr. Quoc Nguyen for providing the source code for the MPScan program and Christopher Hoy and Dr. Frederic Bourgeois for their help in implementing our 2PAM and autocorrelation systems, and useful discussions. We acknowledge support by the National Institutes of Health NIH Grant RO3 CA125774–01 and National Science Foundation Grants BES-0508266 and Career Award: CBET-0846868. N. J. Durr was partially supported by an NSF IGERT fellowship.

References

- Denk W., Strickler J., and Webb W., “2-Photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy,” Science 248, 73–76 (1990). 10.1126/science.2321027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters B. R., So P. T., and Gratton E., “Multiphoton excitation fluorescence microscopy and spectroscopy of in vivo human skin,” Biophys. J. 72, 2405–2412 (1997). 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78886-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig K. and Riemann I., “High-resolution multiphoton tomography of human skin with subcellular spatial resolution and picosecond time resolution,” J. Biomedi. Opt. 8, 432–439 (2003). 10.1117/1.1577349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel W. R., Williams R. M., Christie R., Nikitin A. Y., Hyman B. T., and Webb W. W., “Live tissue intrinsic emission microscopy using multiphoton-excited native fluorescence and second harmonic generation,” Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7075–7080 (2003). 10.1073/pnas.0832308100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skala M. C., Squirrell J. M., Vrotsos K. M., Eickhoff J. C., Gendron-Fitzpatrick A., Eliceiri K. W., and Ramanujam N., “Multiphoton microscopy of endogenous fluorescence differentiates normal, precancerous, and cancerous squamous epithelial tissues,” Cancer Res. 65, 1180–1186 (2005). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder–Smith P., Osann K., Hanna N., Abbadi N. El, Brenner M., Messadi D., and Krasieva T., “In vivo multiphoton fluorescence imaging: a novel approach to oral malignancy,” Lasers Surg. Med. 35, 96–103 (2004). 10.1002/lsm.20079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Jee S., Kuo C., Wu R., Lin W., Chen J., Liao Y., Hsu C., Tsai T., et al. “Discrimination of basal cell carcinoma from normal dermal stroma by quantitative multiphoton imaging,” Opt. Lett. 31, 2756–2758 (2006). 10.1364/OL.31.002756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoli J., Smedh M., Wennberg A., and Ericson M. B., “Multiphoton laser scanning microscopy on non-melanoma skin cancer: Morphologic features for future non-invasive diagnostics,” J. Investig. Dermatol. 128, 1248–1255 (2007). 10.1038/sj.jid.5701139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Li F., Wu R., Hovhannisyan V. A., Lin W., Lin S., So P. T. C., and Dong C., “Differentiation of normal and cancerous lung tissues by multiphoton imaging,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14, 044034 (2009). 10.1117/1.3210768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajadhyaksha M., Anderson R. R., and Webb R. H., “Video-rate confocal scanning laser microscope for imaging human tissues in vivo,” Appl. Opt. 38, 2105–2115 (1999). 10.1364/AO.38.002105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. T. C., Mandella M. J., Crawford J. M., Contag C. H., Wang T. D., and Kino G. S., “Efficient rejection of scattered light enables deep optical sectioning in turbid media with low-numerical-aperture optics in a dual-axis confocal architecture,” J. Biomed. Opt. 13, 034020 (2008). 10.1117/1.2939428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman D. L., Utzinger U., Fuchs H., Zuluaga A., Gossage K., Gillenwater A. M., Jacob R., Kemp B., and Richards-Kortum R. R., “Optimal excitation wavelengths for in vivo detection of oral neoplasia using fluorescence spectroscopy,” Photochem. Photobiol. 72, 103–113 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drezek R., Brookner C., Pavlova I., Boiko I., Malpica A., Lotan R., Follen M., and Richards-Kortum R., “Autofluorescence microscopy of fresh cervical-tissue sections reveals alterations in tissue biochemistry with dysplasia,” Photochem. Photobiol. 73, 636 (2001). 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)0730636AMOFCT2.0.CO2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters B., “Three-dimensional confocal microscopy of human skin in vivo: autofluorescence of human skin,” Bioimaging 4, 13–19 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Dunn A. K., Wallace V. P., Coleno M., Berns M. W., and Tromberg B. J., “Influence of optical properties on two-photon fluorescence imaging in turbid samples,” Appl. Opt. 39, 1194–1201 (2000). 10.1364/AO.39.001194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C. Y., Koenig K., and So P., “Characterizing point spread functions of two-photon fluorescence microscopy in turbid medium,” J. Biomed. Opt. 8, 450–459 (2003). 10.1117/1.1578644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying J., Liu F., and Alfano R. R., “Spatial distribution of two-photon-excited fluorescence in scattering media,” Appl. Opt. 38, 224–229 (1999). 10.1364/AO.38.000224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theer P., and Denk W., “On the fundamental imaging-depth limit in two-photon microscopy,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 23, 3139–3149 (2006). 10.1364/JOSAA.23.003139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leray A., Odin C., Huguet E., Amblard F., and Grand Y. L., “Spatially distributed two-photon excitation fluorescence in scattering media: Experiments and time-resolved Monte Carlo simulations,” Opt. Comm. 272, 269–278 (2007). 10.1016/j.optcom.2006.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Theer P., Hasan M. T., and Denk W., “Two-photon imaging to a depth of 1000 μm in living brains by use of a Ti:Al2O3 regenerative amplifier,” Opt. Lett. 28, 1022–1024 (2003). 10.1364/OL.28.001022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radosevich A. J., Bouchard M. B., Burgess S. A., Chen B. R., and Hillman E. M. C., “Hyperspectral in vivo two-photon microscopy of intrinsic contrast,” Opt. Lett. 33, 2164–2166 (2008). 10.1364/OL.33.002164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Zheng W., and Qu J. Y., “Imaging of epithelial tissue in vivo based on excitation of multiple endogenous nonlinear optical signals,” Opt. Lett. 34, 2853–2855 (2009). 10.1364/OL.34.002853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Shilagard T., Bell B., Motamedi M., and Vargas G., “In vivo multimodal nonlinear optical imaging of mucosal tissue,” Opt. Express 12, 2478–2486 (2004). 10.1364/OPEX.12.002478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palero J. A., de Bruijn H. S., van der Ploeg-van den Heuvel A., Sterenborg H. J. C. M., and Gerritsen H. C., “In vivo nonlinear spectral imaging in mouse skin,” Opt. Express 14, 4395–4402 (2006). 10.1364/OE.14.004395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchi R., Massi D., Sestini S., Carli P., Giorgi V. De, Lotti T., and Pavone F. S., “Multidimensional non-linear laser imaging of Basal Cell Carcinoma,” Opt. Express 15, 10135–10148 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.010135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters B. R., So P. T. C., and Gratton E., “Multiphoton excitation microscopy of in vivo human skin: Functional and morphological optical biopsy based on three-dimensional imaging, lifetime measurements and fluorescence spectroscopy,” Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 838, 58–67 (1998). 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oheim M., Beaurepaire E., Chaigneau E., Mertz J., and Charpak S., “Two-photon microscopy in brain tissue: Parameters influencing the imaging depth,” J. Neurosci. Methods 111, 29–37 (2001). 10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00438-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinter J. T. and Levene M. J., “Optimizing fluorescence collection in multiphoton microscopy,” Biomed. Opt. OSA Tech. Dig., BMD70 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q., Tsai P. S., and Kleinfeld D., “MPScope: A versatile software suite for multiphoton microscopy,” J. Neurosci. Methods 156, 351–359 (2006). 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel W., Williams R. and Webb, W. “Nonlinear magic: Multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences,” Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1368–1376 (2003). 10.1038/nbt899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urey, H. “Spot Size, Depth-of-Focus, and Diffraction Ring Intensity Formulas for Truncated Gaussian Beams,” Appl. Opt. 43, 620–625 (2004). 10.1364/AO.43.000620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F. and Denk W., “Deep tissue two-photon microscopy,” Nat. Methods 2, 932–940 (2005). 10.1038/nmeth818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen V., Alexander S., Heupel W., Hirschberg M., Hoffman R. M., and Friedl P., “Infrared multiphoton microscopy: Subcellular-resolved deep tissue imaging,” Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 54–62 (2009). 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Vinegoni C., Ralston T. S., Luo W., Tan W., and Boppart S. A., “Spectroscopic spectral-domain optical coherence microscopy,” Opt. Lett. 31, 1079–1081 (2006). 10.1364/OL.31.001079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starosta M. S. and Dunn A. K., “Three-dimensional computation of focused beam propagation through multiple biological cells,” Opt. Express 17, 12455–12469 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.012455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M., Squier J., and Brakenhoff G. J., “Measurement of femtosecond pulses in the focal point of a high-numerical-aperture lens by two-photon absorption,” Opt. Lett. 20, 1038–1040 (1995). 10.1364/OL.20.001038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guild J. B., Xu C., and Webb W. W., “Measurement of group delay dispersion of high numerical aperture objective lenses using two-photon excited fluorescence,” Appl. Opt. 36, 397–401 (1997). 10.1364/AO.36.000397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaurepaire E., Oheim M., and Mertz J., “Ultra-deep two-photon fluorescence excitation in turbid media,” Opt. Commun. 188, 25–29 (2001). 10.1016/S0030-4018(00)01156-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tycho A., Jørgensen T. M., Yura H. T., and Andersen P. E., “Derivation of a Monte Carlo method for modeling heterodyne detection in optical coherence tomography systems,” Appl. Opt. 41, 6676–6691 (2002). 10.1364/AO.41.006676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaurepaire E. and Mertz J., “Epifluorescence collection in two-photon microscopy,” Appl. Opt. 41, 5376–5382 (2002). 10.1364/AO.41.005376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theer P., “On the fundamental imaging-depth limit in two-photon microscopy,” Dissertation, University of Heidelberg (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzler C., Matlab Functions for Mie Scattering and Absorption, Institut fur Angewandte Physik: University of Bern; (2006). [Google Scholar]

- de Grauw C. J., Vroom J. M., Van Der Voort H. T., and Gerritsen H. C., “Imaging properties in two-photon excitation microscopy and effects of refractive-index mismatch in thick specimens,” Appl Opt 38, 5995–6003 (1999). 10.1364/AO.38.005995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen H., Hanninen P., and Hell S., “Refractive-index-induced aberrations in 2-photon confocal fluorescence microscopy,” J. Microsc.-Oxford 176, 226–230 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Drezek R., Sokolov K., Utzinger U., Boiko I., Malpica A., Follen M., and Richards-Kortum R., “Understanding the contributions of NADH and collagen to cervical tissue fluorescence spectra: Modeling, measurements, and implications,” J. Biomed. Opt. 6, 385 (2001). 10.1117/1.1413209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova I., Williams M., El-Naggar A., Richards-Kortum R., and Gillenwater A., “Understanding the biological basis of autofluorescence imaging for oral cancer detection: High-resolution fluorescence microscopy in viable tissue,” Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 2396–2404 (2008). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palero J. A., de Bruijn H. S., Van Der Ploeg Van Den Heuvel A., Sterenborg H. J. C. M., and Gerritsen H. C., “Spectrally resolved multiphoton imaging of in vivo and excised mouse skin tissues,” Biophys. J. 93, 992–1007 (2007). 10.1529/biophysj.106.099457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldbrand S., Simonsson C., Smedh M., and Ericson M. B., “Point spread function measured in human skin using two-photon fluorescence microscopy,” Proc. SPIE 7367, 73671R (2009). 10.1117/12.831542 [DOI]

- Hoy C. L., Durr N. J., Chen P., Piyawattanametha W., Ra H., Solgaard O., and Ben-Yakar A., “Miniaturized probe for femtosecond laser microsurgery and two-photon imaging,” Opt. Express 16, 9996–10005 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.009996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson D. R., Zipfel W. R., Williams R. M., Clark S. W., Bruchez M. P., Wise F. W., and Webb W. W., “Water-soluble quantum dots for multiphoton fluorescence imaging in vivo,” Science 300, 1434–1436 (2003). 10.1126/science.1083780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König K., Ehlers A., Riemann I., Schenkl S., Bckle R., and Kaatz M., “Clinical two-photon microendoscopy,” Microsc. Res. Tech. 70, 398–402 (2007). 10.1002/jemt.20445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. C., and Schnitzer M. J., “Multiphoton endoscopy,” Opt. Lett. 28, 902–904 (2003). 10.1364/OL.28.000902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G., van Howe J., Durst M., Zipfel W., and Xu C., “Simultaneous spatial and temporal focusing of femtosecond pulses,” Opt. Express 13, 2153–2159 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.002153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oron D., Tal E., and Silberberg Y., “Scanningless depth-resolved microscopy,” Opt. Express 13, 1468–1476 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.001468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leray A., Lillis K., and Mertz J., “Enhanced background rejection in thick tissue with differential-aberration two-photon microscopy,” Biophys. J. 94, 1449–1458 (2008). 10.1529/biophysj.107.111476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchi R., Sampson D., Massi D., and Pavone F., “Contrast and depth enhancement in two-photon microscopy of human skin ex vivo by use of optical clearing agents,” Opt. Express 13, 2337–2344 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.002337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobat D., Durst M. E., Nishimura N., Wong A. W., Schaffer C. B., and Xu C., “Deep tissue multiphoton microscopy using longer wavelength excitation,” Opt. Express 17, 13354–13364 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.013354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]