Report of a Case

A colleague asks for your suggestions on the evaluation and treatment of a 78-year-old woman whose chief complaint is that she awakens four to five times each night to urinate. Your colleague adds that the patient does not have diabetes mellitus, is not taking diuretics, and had a physical examination that produced normal findings.

Discussion

Nocturia is defined as the interruption of sleep by the need to urinate. While it is a relatively uncommon complaint among younger adults, the prevalence of nocturia increases with increasing age in both men and women. For patients who are age 60 to 70 years, the prevalence of nocturia is between 11% and 50%. For those who are age 80 years, the prevalence rises to between 80% and 90%, with nearly 30% experiencing two or more episodes nightly.1 The older adult already experiences more frequent arousals from sleep and less deep sleep compared with younger adults. The presence of nocturia further disrupts sleep, leading to daytime somnolence, symptoms of depression, cognitive dysfunction, and a reduced sense of well-being and quality of life. Moreover, nocturia is associated with a 1.8-fold increased risk of hip fracture.2 Men who arise more than three times a night to urinate also have a twofold increase in mortality compared with those with fewer episodes of nocturia.3 Nocturia is a frequent patient complaint leading to urologic and nephrologic consultations.

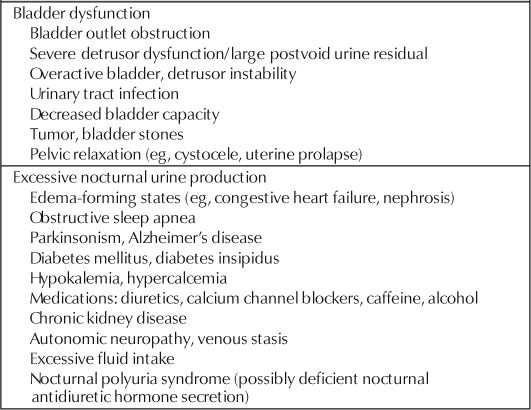

The causes of nocturia are many (Table 1). They can be divided into conditions affecting the storage of urine in the bladder and those involving the excessive production of urine by the kidneys. Although it is commonly assumed that the reason for nocturia is bladder dysfunction, particularly among elderly men, this assumption is not accurate. Bruskewitz et al noted that nocturia persisted in 25% of men who underwent prostate surgery for presumed bladder outlet obstruction and were monitored for three years, suggesting that the etiology of nocturia had not been addressed by surgery in these patients.4 A careful history and physical examination provide clues to the etiology. Symptoms such as decreased urinary stream, hesitancy, and a sense of incomplete voiding suggest bladder outlet obstruction. Frequency, urgency, and bladder spasms suggest bladder irritation, perhaps due to infection. Gross hematuria may be an indication of a bladder tumor or stones. The absence of such symptoms, however, does not rule out bladder pathology, because bladder outlet obstruction can be clinically subtle, with symptoms attributed to “old age.”

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of nocturia in the elderly

Many other medical conditions have been associated with nocturia. Important conditions to inquire about include diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic kidney disease, and neurologic conditions such as autonomic neuropathy, Parkinsonism, and Alzheimer's disease. In congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, and autonomic neuropathy, nocturia is due to the mobilization of pooled interstitial fluid on recumbency. With obstructive sleep apnea, high negative intrathoracic pressures during episodes of airway obstruction and systemic hypoxemia lead to solute and water excretion mediated in part through atrial natriuretic peptide. Chronic kidney disease is associated with tubular concentrating defects and large solute delivery through the remaining functional nephrons. Neurologic disease may affect central control over the circadian release of hormones, such as antidiuretic hormone. Use of medications, such as diuretics and calcium channel blockers, and habits, such as excessive fluid intake and alcohol and caffeine use, are important to note. Why calcium channel blockers have a diuretic effect in some but not all patients is not known.

During a physical examination, orthostatic vital signs should be obtained to evaluate for evidence of autonomic neuropathy. Evidence of heart failure or other edema-forming states, including venous insufficiency, should be sought. An abdominal examination may reveal a large distended bladder or evidence of fecal impaction. A careful genitourinary examination should include a search for prostatic enlargement in men, pelvic relaxation in women, detrusor dysfunction as manifested by a large postvoid residual, and evidence of neurologic deficits related to the sacral nerve roots, including sensory deficits, poor sphincter tone, or absent anal wink reflex.

Initial laboratory tests should include an assessment of renal function, glucose, electrolytes, and calcium and urinalysis with a microscopic examination of the urine. If symptoms suggest infection, a urine culture should be obtained. An ultrasound bladder evaluation before and after voiding should also be performed. If the patient manifests symptoms suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea, a polysomnogram is indicated. If, after initial assessment, no clear etiology is discovered, the patient should be asked to keep a careful voiding diary for at least three days. The volume and time of each void should be noted, as well as whether the voiding episode disrupted sleep. These data will allow the physician to determine the patient's functional bladder capacity and whether the patient passes a significant fraction of the daily urine output at night. The typical functional bladder capacity is approximately 350 to 400 mL. Urine production at night is usually less than one-third of the total daily urine output. If the nocturnal urine volume exceeds this amount, the patient is deemed to have nocturnal polyuria.

Saito et al reviewed voiding diaries of 85 study subjects older than age 65 years and compared them to the diaries of 130 study subjects younger than age 65 years, all of whom had been referred for a complaint of nocturia.5 After exclusion of benign prostatic hypertrophy, neurogenic bladder, cystitis, diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, and chronic kidney disease, the most common condition accounting for nocturia among the elderly study subjects was nocturnal polyuria, seen in 37%. The second most common cause was an unstable bladder (small voiding volumes associated with urgency), seen in 34%.

Nocturnal polyuria is a syndrome seen in older patients where the usual ratio of day to night urine production is altered.6 Normally, after an individual reaches the age of seven years, urine volume produced during the day is twice as much as nightly urine volume. In patients with nocturnal polyuria, this ratio is altered such that >35% of the total daily urine output occurs at night despite a normal daily total urine output of 1000 to 1500 mL/day. In some individuals, nocturnal urine production exceeds that produced during the day. The reason for the excessive nocturnal urine production is not clear. Some suggest that antidiuretic hormone levels, typically elevated during sleep, are abnormally low in these individuals, resulting in diuresis. This finding is not universally seen, however, particularly among women with nocturnal polyuria. A relative nocturnal deficiency of antidiuretic hormone also does not explain the altered pattern of sodium and nonelectrolyte solute excretion that also occurs among these individuals. A full explanation of nocturnal polyuria syndrome has yet to be provided.

Nocturnal polyuria is a syndrome seen in older patients where the usual ratio of day to night urine production is altered.6

Several pharmacologic agents have been used to treat nocturnal polyuria with various degrees of success. Simple maneuvers such as reducing fluid intake for six hours before recumbency are usually not successful. Compression stockings may prevent dependent edema that can start when a patient lies down and results in nocturia. Loop diuretics taken approximately six to eight hours before the patient lies down induce transient volume depletion, thereby reducing nocturnal urine production once the diuretic effect has diminished. Other agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, melatonin, imipramine, and dried fruits, have been tried. The use of continuous positive airway pressure ventilation in patients with documented obstructive sleep apnea reduces symptoms of nocturia. Most studies have focused on the use of desmopressin, an antidiuretic hormone analogue, to reduce nocturnal polyuria. Multicenter, double blinded, placebo-controlled studies using oral desmopressin have demonstrated reduced nocturnal voiding among patients with nocturnal polyuria during a follow-up period of 10 to 12 months.7 Desmopressin was generally well tolerated; the most frequent adverse effects were headache, nausea, dizziness, and peripheral edema, seen in fewer than 5% to 10% of patients. Hyponatremia was seen in 14% of patients but was asymptomatic and mild (>130 mEq/L) in nearly all cases. In small case series, intranasal desmopressin has also been used successfully.

If the patient has symptoms suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction, a urologic referral is indicated. Detailed urodynamic evaluation and/or cystoscopy may be necessary. Anticholinergic agents may benefit those with an overactive bladder. In contrast, cholinergic agents or intermittent catheterization may be required in those with poor detrusor function and large postvoid residual. Alpha-adrenergic blocking agents and 5·-reductase inhibitors may help men with bladder outlet obstruction and prostatic hypertrophy. Surgery may be indicated if there is evidence of mechanical obstruction refractory to drug therapy.

Conclusion

This particular patient should be questioned about any symptoms of heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea. Her fluid intake habits, her medications, and her caffeine and alcohol use should be noted. A careful abdominal and genitourinary examination should be performed, specifically looking for cystocele, uterine prolapse, sensory neurologic findings, and fecal impaction. A postvoid residual measurement and screening laboratory tests, including those for electrolytes, creatinine, calcium, and glucose and a urinalysis, should be obtained. If the initial evaluation is unrevealing, she should be asked to maintain a voiding diary and minimize her fluid intake for six to eight hours before going to bed. Should her voiding diary demonstrate nocturnal polyuria syndrome, she can try eating some dried fruits before bedtime and consider a trial of a low-dose loop diuretic to be taken six hours before going to bed. Should she continue to have symptoms, a trial of 100 μg of oral desmopressin at night can be considered, with careful and frequent monitoring of her serum electrolytes.

Alpha-adrenergic blocking agents and 5·-reductase inhibitors may help men with bladder outlet obstruction and prostatic hypertrophy.

References

- Weiss JP, Blaivas JG. Nocturia. J Urol. 2000 Jan;163(1):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB, Moore MT, May FE, Marks RG, Hale WE. Nocturia: a risk factor for falls in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992 Dec;40(12):1217–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asplund R. Mortality in the elderly in relation to nocturnal micturition. BJU Int. 1999 Aug;84(3):297–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruskewitz RC, Larsen EH, Madsen PO, Dorflinger T. Three-year follow-up of urinary symptoms after transurethral resection of the prostate. J Urol. 1986 Sep;136(3):613–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44991-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Kondo A, Kato T, Yamada Y. Frequency-volume charts: comparison of frequency between elderly and adult patients. Br J Urol. 1993 Jul;72(1):38–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb06453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asplund R. The nocturnal polyuria syndrome (NPS) Gen Pharmacol. 1995 Oct;26(6):1203–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(94)00310-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lose G, Mattiasson A, Walter S, et al. Clinical experiences with desmopressin for long-term treatment of nocturia. J Urol. 2004 Sep;172(3):1021–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000136203.76320.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]