Abstract

This study was conducted to confirm our previous reports that group housing lowered basal heart rate and various evoked heart-rate responses in Sprague–Dawley male and female rats and to extend these observations to spontaneously hypertensive rats. Heart rate data were collected by using radiotelemetry. Initially, group- and single-housed rats were evaluated in the same animal room at the same time. Under these conditions, group-housing did not decrease heart rate in undisturbed male and female rats of either strain compared with single-housed rats. Separate studies then were conducted to examine single-housed rats living in the room with only single-housed rats. When group-housed rats were compared with these single-housed rats, undisturbed heart rates were reduced significantly, confirming our previous reports for Sprague–Dawley rats. However, evoked heart rate responses to acute procedures were not reduced universally in group-housed rats compared with either condition of single housing. Responses to some procedures were reduced, but others were not affected or were significantly enhanced by group housing compared with one or both of the single-housing conditions. This difference may have been due, in part, to different sensory stimuli being evoked by the various procedures. In addition, the variables of sex and strain interacted with housing condition. Additional studies are needed to resolve the mechanisms by which evoked cardiovascular responses are affected by housing, sex, and strain.

Group housing of rodents is recommended on grounds that it reduces stress that accompanies isolated housing and therefore improves animal wellbeing. Experimental evidence supporting this recommendation depends on methods that can monitor stress levels or wellbeing effectively. Several techniques to detect stress in rodents are currently in use. Radiotelemetry methods have allowed for minute-to-minute determination of cardiovascular and body temperature responses.2,4,17,20,22,23,25,27,33,34,38,39,46,47,50 Chronic blood sampling through indwelling catheters makes it possible to monitor the blood levels of stress hormones (for example, glucocorticoids, prolactin) in conscious animals,18,28,31,35,36,45 whereas serial collection of feces has allowed for the noninvasive monitoring of fecal corticosterone metabolites in rats.15

To reduce stress and improve wellbeing, several methods that alter the animal's environment have been studied. These include the addition of enrichment devices to the animal's home cage,41 increased cage size,43 and reduced ambient illumination3. Extending the dark phase of the photocycle has been shown to decrease blood pressure and heart rate in rats3,51 and may prove to be yet another method to reduce stress. Finally and directly related to the current studies, social enrichment by group or colony housing has been reported to reduce cardiovascular parameters in rats,5,14,42,44 suggesting a reduced level of stress, but this method actually can contribute to stress if the number of rats housed together produces crowding or if aggressive interaction between animals occurs.5

The initial objectives of the current study were to confirm our previous reports of the effects of group housing on basal heart rate and evoked heart rate responses in Sprague–Dawley rats and to determine whether the effects of housing generally extend to male and female rats of other strains. We chose to evaluate the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) strain because it is very susceptible to stress.26,29,30,32 Both sexes were included for completeness of the comparisons. As the study progressed, results indicated that group- and single-housed rats living in the same room at the same time may interact with each other. Therefore, a third objective was added to determine whether our previous results could be replicated when group- and single-housed rats are in close proximity to each other.

The hypotheses tested in the current studies were: that group-housing reduces heart rate in undisturbed rats; that compared with single housing, group housing reduces heart-rate responses induced by acute procedures; and that housing effects are influenced by sex and strain.

Materials and Methods

Adult male and female Holtzman Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats were purchased from Harlan Sprague–Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). Body weights were 175 to 200 gm on arrival. All rats were obtained from colonies reported by the vendor to be free from adventitious viruses, mycoplasma, respiratory and enteric bacteria (except several strains of Helicobacter), and parasites (except nonpathogenic commensal protozoa). Potential animal room exposure to infectious agents during the study was evaluated by standard serology screening of blood samples collected at the end of the study from sentinel rats housed in the same room. The results of these assessments showed no changes from the initial screening report provided by the vendor.

Husbandry during experiments.

The rats were allowed to acclimate to the animal room conditions and husbandry procedures for 2 wk prior to surgical implantation of the radiotelemetry transmitters. The environmental conditions in the animal room where the telemetry data were collected were as follows: temperature, 22 to 26 °C; relative humidity, 30% to 60%; lighting, 200 lm/m2 at cage level; lights on, 0700 to 1900 h.

In the initial set of experiments, instrumented rats were housed individually or with 3 noninstrumented cage mates in the same animal room at the same time. Analysis of the data suggested potential interaction between group- and single-housed rats living in the same room at the same time, resulting in only a few significant differences in basal heart rate between group- and single-housed rats—results that were different than we reported previously for Sprague–Dawley male and female rats.42,44 Therefore, an additional set of experiments was conducted in which separate rats were housed individually in the same animal room as used previously except that the room contained only singly housed rats. For both sets of experiments, Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive rats were examined in the same room at the same time, and female rats of both strains were examined in the same room but at a different time than male rats.

Rats were housed in conventional solid-bottom polycarbonate cages (nominal floor area, 930 cm2) with standard stainless steel lids and hardwood chip bedding (depth, 3 to 4 cm; Sanichip, PJ Murphy Forest Products Corporation, Montville, NJ). Cages were changed twice each week (Mondays and Thursdays) in the first set of experiments or once weekly in the second set. Pelleted rat chow (no. 5001, Purina Mills, Richmond, IN) was provided ad libitum, and tap water was provided in a water bottle with a sipper tube.

Surgical procedures.

In preparation for the abdominal and femoral incisions necessary for the implantation of the radiotelemetry transmitter, these areas were clipped free of hair, scrubbed with a 7.5% povidone–iodine solution (Betadine Surgical Scrub, Purdue-Frederick Company, Norwalk, CT), and rinsed with sterile 0.9% NaCl. The transmitter (model TA11PA-C40, Data Sciences International Corporation, St Paul, MN) was implanted aseptically through a 5- to 6-cm ventral midline incision in the abdominal cavity of each rat under ketamine (80 mg/kg IP; Ketaset, Ft Dodge Animal Health, Ft Dodge, IA) and xylazine (7 mg/kg IP; Rompun, Bayer Corporation, Shawnee Mission, KS) anesthesia. The catheter attached to the telemetry transmitter was tunneled through the abdominal muscle wall and then subcutaneously to the skin incision in the left femoral triangle and inserted into the femoral artery centrally to a depth of 3.0 cm. The catheter was secured with sutures and the femoral incision closed. Just prior to closure of the abdominal incision, 20 mL sterile saline containing 20 mg antibiotic (Cefazolin, West-Ward Pharmaceutical, Eatontown, NJ) was flushed into the peritoneal cavity for fluid replacement and to prevent postsurgical infection. We have observed that this procedure also eliminates intraabdominal adhesions, which were common before introduction of this peritoneal flush. Each telemetry implantation procedure was completed in 30 to 45 min.

Each rat also received 5 mL sterile 5% dextrose containing ketoprofen (Ketofen, Fort Dodge Animal Health) at 16 mg/kg SC immediately after surgery for analgesia and to provide a short-term glucose supplement. Postsurgical monitoring for signs of pain indicated that additional doses of ketoprofen were not needed. Rats were placed on clean paper toweling in their home cages immediately after surgery, and the cages were placed on circulating warm water pads until the animals were moving in the cage (approximately 1 to 2 h after surgery), at which point the cages were placed on telemetry receiver pads on the cage rack. Rats that were group housed were placed in individual cages during recovery and then transferred back to their original home cage once they began moving in the recovery cage.

Postsurgical recovery was monitored by daily visual examination of the incisions and overall condition of the rats, including observing for signs of pain (for example, lack of movement, vocalization when handled, ruffled coat). Water intake (measured daily), body weight gain (determined every other day), and blood pressure, heart rate, and movement in the cage (measured every 5 min by telemetry beginning about 2 h postsurgery) also were used to assess recovery. Water intake and body weight gain returned to presurgical values by 3 to 5 d whereas heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and activity showed stable circadian patterns by 7 d.

Animal procedures.

Beginning 11 to 14 d after surgery, heart rate and blood pressure were monitored at times when the animals were undisturbed (from 0800 to 0900 and from 1300 to 0700, when no humans were present in the room) and during and for approximately 3 h after exposure to each of a battery of acute procedures (from 1000 to 1300 h). These procedures were selected to be representative of the following functional categories: husbandry procedures (routine cage change, 1 min of gentle handling, 1 h of exposure to an unfamiliar conspecific, removal of a familiar conspecific after 5 d of cohabitation); experimental procedures (manual restraint and subcutaneous injection, transport from animal room to lab and subcutaneous injection with manual restraint, 1 to 2 min of restraint in a rat restrainer with tail-vein injection, manual restraint with intraperitoneal injection); and stressful procedures (15 min of exposure to the odors of urine and feces from stressed male or female rats, 15 min of exposure to the odor of dried rat blood, 60 min of restraint in a rat restrainer in the home cage). Six rats of each strain, sex, and housing condition were subjected individually to the acute procedures beginning at 1000 on alternate days (Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays). Over the course of the study, each instrumented rat was subjected to every procedure once. The alternate-day schedule was established to reduce any carryover effects that may exist from one procedure to the next. There were no indications that the rats became conditioned to procedures being conducted on this schedule (that is, there were no changes in heart rate at 1000 on intervening nonexperimental days in the current and no differences in heart rate responses to some of the same procedures applied on the Monday–Wednesday–Friday schedule for 2 consecutive weeks in a separate study). All routine animal care and experimental procedures were performed by the same 2 persons, with care taken to ensure that both used the same techniques.

All procedures were approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Collection of radiotelemetry data.

Output from the telemetry transmitters was collected by using hardware and software from Data Sciences International Corporation. Data were sampled for 10 s at 1- or 5-min intervals after the various acute procedures and during undisturbed periods, respectively. These data were saved to the hard drive of a desktop computer and subsequently transferred as spreadsheet files by using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) to other computers for summarization and statistical analyses. Because of the large number of comparisons, only heart rate data are presented in the Results section.

Statistical analysis.

The heart rate data collected at 5-min intervals during undisturbed periods were averaged across each respective time period (0800 to 0900, 1300 to 1900, and 1900 to 0700 h) for each of the 6 animals in a particular group and then mean ± SEM was calculated from these 6 values. Heart rate data during the 3 undisturbed periods were analyzed separately because we thought that time of day or lights-on or -off might be confounding if the undisturbed data were grouped and analyzed together. The heart rate responses to the various acute procedures are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the area under the response curve values obtained from the 6 rats in each group. The value for area under the response curve for each rat was computed as the sum of changes in heart rate, corrected for the mean heart rate obtained across the 0800-to-0900 undisturbed control period for that rat, from the onset of the procedure to the point when the response returned to the 0800 to 0900 mean value. Three-factor ANOVA followed by Tukey posthoc testing was done for each undisturbed period and for each acute manipulation by using SigmaStat statistical software (Systat Corporation, Point Richmond, CA) to determine whether significant main effects of housing condition, strain, or sex or significant interactions between housing condition, strain, or sex were present. This analysis was followed by comparisons of the housing conditions within each strain and sex by using one-factor ANOVA followed by Tukey posthoc testing. In addition, comparisons of male and female rats (within strains and housing conditions) and comparisons of Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive rat strains (within sex and housing conditions) were made by using one-factor ANOVA. Differences were declared statistically significant at a P level of 0.05 or less.

Results

Undisturbed conditions.

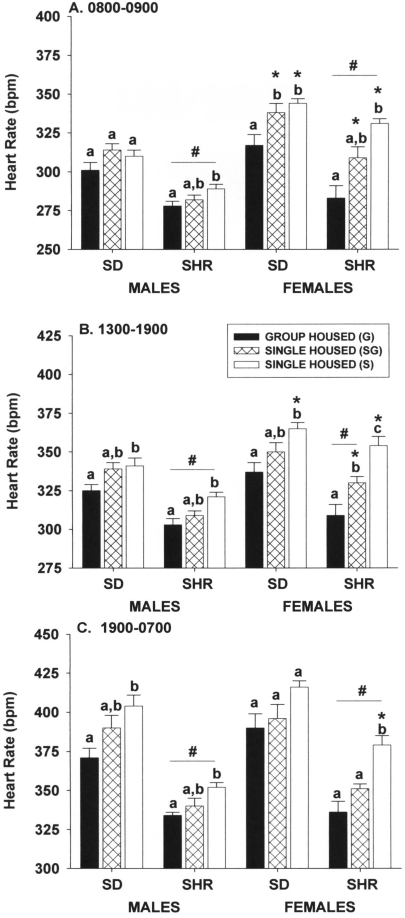

During times of the experimental days when rats were undisturbed by the research staff (0800 to 0900, 1300 to 1900, and 1900 to 0700 h), group housing did not significantly (P > 0.05) reduce heart rate in male rats of either strain when compared with rats single housed in the room at the same time (Figure 1). However, undisturbed heart rate in group-housed male rats of both strains were significantly (P < 0.05) lower than those of rats single-housed in a room where no group-housed rats were present. This same general pattern of differences between housing conditions was observed for female rats also.

Figure 1.

Effect of single and group housing on heart rate of male and female Sprague–Dawley (SD) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats during undisturbed periods (A) in the morning (0800 to 0900), (B) in the afternoon (1300 to 1900), and (C) at night (1900 [lights off] to 0700 [lights on]). Solid bars, rats housed 4 per cage; open bars, rats housed individually in a room with only single-housed rats; hatched bars, rats housed individually in the same room and at the same time group-housed rats. Means (n = 6 per group) with different letters within a sex and strain are statistically different (P < 0.05). *, Value for female rats significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of males of the same strain. #, Value for SHR significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of SD rats of the same sex.

Strain and sex affected heart rate under undisturbed conditions (Figure 1). Spontaneously hypertensive male or female rats had significantly (P < 0.05) lower heart rates than did Sprague–Dawley male or female rats, respectively. Sex differences were not as uniform as strain differences, in that significant housing × sex interactions were evident during the light phase of the photocycle. Heart rates of group-housed female rats of both strains were not different from those of male rats at any time of the day or night. However, under both single-housing conditions, heart rate in the morning (0800 to 0900) in Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive female rats was significantly (P ≤ 0.05) higher than that in male rats (Figure 1 A). These sex-associated differences disappeared in Sprague–Dawley rats as the day progressed, whereas in spontaneously hypertensive rats, the differences observed in the morning continued into the afternoon period (1300 to 1900; Figure 1 B). During the night (1900 to 0700), only female rats housed singly in a room with only single-housed rats had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) higher heart rate than similarly housed male rats (Figure 1 C).

Exposure to acute husbandry, experimental, and stressful procedures.

When heart rate responses to acute procedures were examined, the effects of housing conditions, strain, and sex varied with procedure (Figures 2 through 7).

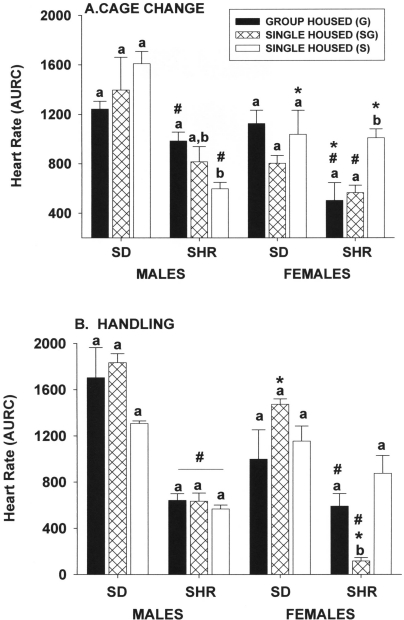

Figure 2.

Effect of single and group housing on heart rate responses (area under response curve) of male and female Sprague–Dawley (SD) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats after (A) a routine cage change or (B) 1 min of gentle handling. Solid bars, rats housed 4 per cage; open bars, rats housed individually in a room with only single-housed rats; hatched bars, rats housed individually in the same room and at the same time group-housed rats. Means (n = 6 per group) with different letters within a sex and strain are statistically different (P < 0.05). *, Value for female rats significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of males of the same strain. #, Value for SHR significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of SD rats of the same sex.

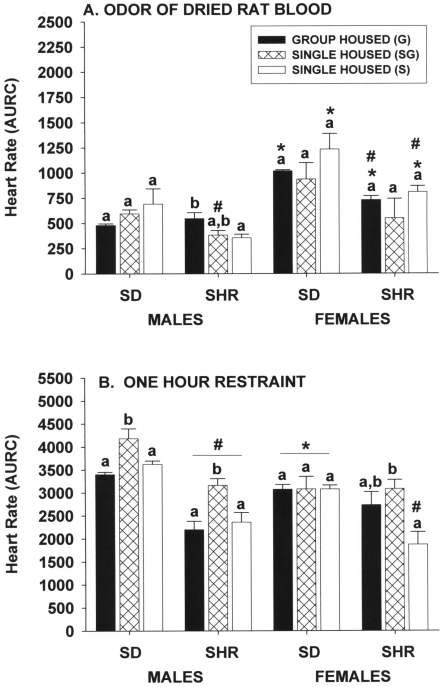

Figure 7.

Effect of single and group housing on heart rate responses (area under response curve) of male and female Sprague–Dawley (SD) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats after (A) 15 min of exposure to the odors of dried rat blood absorbed into a paper towel that was placed on the cage lid or (B) 60 min of restraint in a rodent restrainer placed in the home cage. Solid bars, rats housed 4 per cage; open bars, rats housed individually in a room with only single-housed rats; hatched bars, rats housed individually in the same room and at the same time group-housed rats. Means (n = 6 per group) with different letters within a sex and strain are statistically different (P < 0.05). *, Value for female rats significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of males of the same strain. #, Value for SHR significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of SD rats of the same sex.

Husbandry procedures.

Routine cage change.

Heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley male and female rats to routine cage changes were not different across housing groups (Figure 2 A). However, group housing significantly increased the heart-rate response of spontaneously hypertensive male rats compared with those housed singly in a room with only single-housed rats, whereas group housing significantly (P ≤ 0.05) decreased the heart-rate response of spontaneously hypertensive female rats compared with single-housed female rats. Rats of either strain or sex that were singly housed in the same room as group-housed rats did not have significantly (P ≤ 0.05) different heart-rate responses than those of group-housed rats or those single housed in a room with only single-housed rats (with the exception of spontaneously hypertensive female rats). Heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive male and female rats were generally lower than those of Sprague–Dawley rats, and heart rate responses of female rats were often, but not always, lower than male rats within the same strain.

Housing condition had no significant effect on heart-rate responses to 1 min of gentle handling of male or female Sprague–Dawley or male spontaneously hypertensive rats (Figure 2 B). The heart-rate response of spontaneously hypertensive female rats housed singly in the same room as group-housed animals was significantly (P ≤ 0.05) decreased compared that of group-housed rats or those housed singly. Heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive rats were generally less than those of Sprague–Dawley rats, but there were minimal male–female differences within strains.

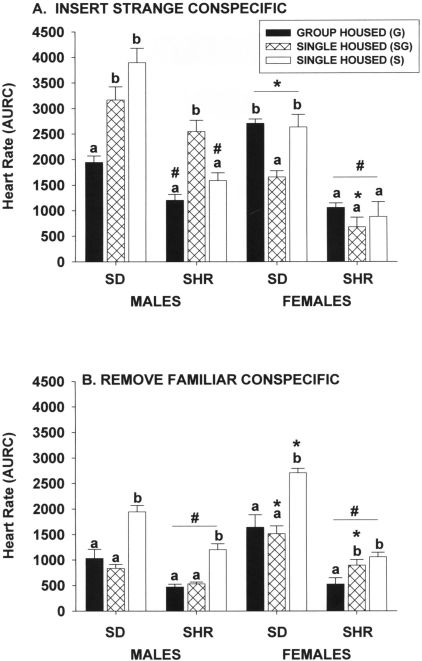

Exposure to a strange conspecific.

Inserting a strange male into cages of both groups of singly housed Sprague–Dawley male rats for 1 h significantly increased (P ≤ 0.05) heart rates compared with those of group-housed Sprague–Dawley male rats (Figure 3 A). However, this pattern of responses was not observed in spontaneously hypertensive male rats or in female rats of either strain. The heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive male rats housed singly in a room with only single-housed rats were not significantly different from those of group-housed male rats but did differ (P ≤ 0.05) from those of singly housed rats in the same room as group-housed rats. The heart rate responses of Sprague–Dawley female rats singly housed in the same room as group-housed rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) lower than those of female rats in either of the other 2 housing conditions. Housing condition had no significant effect on the heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive female rats.

Figure 3.

Effect of single and group housing on heart rate responses (area under response curve) of male and female Sprague–Dawley (SD) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats after the (A) insertion of a strange conspecific into home cage for 1 h or (B) removal of a familiar conspecific from home cage. For the single-housed groups in panel B, a single conspecific was added to the home cage for 5 d prior to its removal. Solid bars, rats housed 4 per cage; open bars, rats housed individually in a room with only single-housed rats; hatched bars, rats housed individually in the same room and at the same time group-housed rats. Means (n = 6 per group) with different letters within a sex and strain are statistically different (P < 0.05). *, Value for female rats significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of males of the same strain. #, Value for SHR significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of SD rats of the same sex.

The heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive male and female rats were reduced compared with those of Sprague–Dawley rats. Male–female differences were minimal in the spontaneously hypertensive strain. A significant (P ≤ 0.05) interaction with housing condition yielded mixed differences in the Sprague–Dawley strain in that group-housed female rats showed greater responses than did group-housed male rats, whereas single-housed female rats showed reduced responses compared with those of respective single-housed male rats.

Removal of a familiar conspecific.

The patterns of heart-rate responses after removal of a familiar cage mate were very similar across both strains and sexes. Rats housed singly in a room with only single-housed rats exhibited a significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater heart-rate response than did rats in the other 2 housing groups (except for spontaneously hypertensive female rats, for which the responses of rats in both single-housed conditions were greater [P ≤ 0.05] than those of group-housed rats). The magnitudes of the heart-rate responses in spontaneously hypertensive male and female rats were less (P ≤ 0.05) than those of Sprague–Dawley rats, and in some housing conditions, female rats had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater responses than did male rats of the same strain.

Experimental procedures.

Subcutaneous injection.

Heart-rate responses of male and female Sprague–Dawley rats to manual restraint and subcutaneous injection of saline did not differ among the 3 housing groups (Figure 4 A). However, within the spontaneously hypertensive strain, heart-rate responses of group-housed male rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than those of single-housed rats in the same room as group-housed animals but did not differ from those in a room with only single-housed rats, whereas group-housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater responses than those of either of the single-housed groups. Rats of the spontaneously hypertensive strain had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) reduced responses compared those of with Sprague–Dawley rats. Intrastrain differences due to sex were minimal.

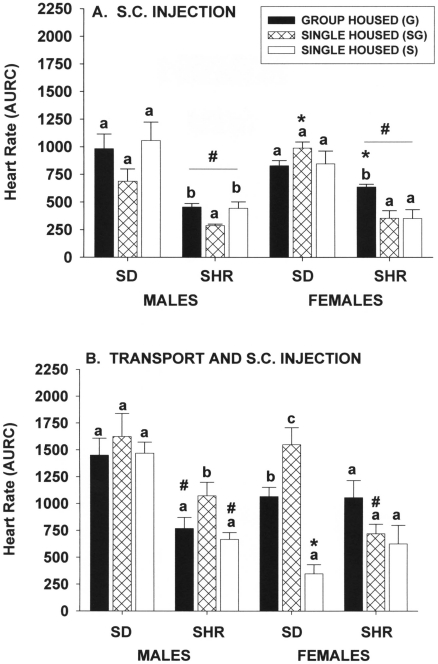

Figure 4.

Effect of single and group housing on heart rate responses (area under response curve) of male and female Sprague–Dawley (SD) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats after (A) hand restraint and subcutaneous injection of saline or (B) transport in the home cage from animal room to experimental lab followed by manual restraint and subcutaneous injection of saline. Solid bars, rats housed 4 per cage; open bars, rats housed individually in a room with only single-housed rats; hatched bars, rats housed individually in the same room and at the same time group-housed rats. Means (n = 6 per group) with different letters within a sex and strain are statistically different (P < 0.05). *, Value for female rats significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of males of the same strain. #, Value for SHR significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of SD rats of the same sex.

Transport and subcutaneous injection.

Moving Sprague–Dawley male rats from the animal room to the laboratory and then injecting them with saline subcutaneously induced heart-rate increases (P ≤ 0.05), but these responses were not significantly different among the 3 housing groups (Figure 4 B). In contrast, the heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive singly housed male rats kept in the same room as group-housed rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than those of rats in either of the other 2 groups, which did not differ from each other. When applied to Sprague–Dawley female rats, this procedure induced the greatest response in singly housed female rats kept in the same room as group-housed rats, and this response was significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than those of female rats in either of the other 2 groups, with singly housed Sprague–Dawley female rats kept with only singly housed rats showing the least response of the 3 housing groups. In contrast, the heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive female rats were not different among the 3 housing groups. Strain effects were more prevalent in male rats, with spontaneously hypertensive male rats generally exhibiting smaller responses than those of Sprague–Dawley male rats. Sex-associated differences within strains were minimal.

Tail-vein injection.

The heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley or spontaneously hypertensive male rats to restraint and tail-vein injection were not significantly affected by housing conditions (Figure 5 A). In contrast, heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley female rats that were group housed or singly housed in the same room as group-housed animals were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) less than those of singly housed animals kept in a room containing only singly housed rats. In spontaneously hypertensive female rats, the effect of housing was almost the inverse of that observed for Sprague–Dawley female rats, in that spontaneously hypertensive female rats kept in a dedicated single-housing room had a significantly (P ≤ 0.05) reduced heart-rate response compared with those of the other single-housing group. The response of group-housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats was not different from that of either of the single-housed groups. Despite significant strain- and sex-associated effects, the interactions of each of these variables with housing condition made straightforward conclusions difficult. For example, male spontaneously hypertensive rats in all housing groups exhibited lower (P ≤ 0.05) heart rate responses than did male Sprague–Dawley rats. In contrast, group-housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats showed greater (P ≤ 0.05) responses than did group-housed Sprague–Dawley female rats, but single-housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats kept with only individually housed rats showed significantly (P ≤ 0.05) lower responses than those of similarly housed Sprague–Dawley female rats. Similarly, group-housed Sprague–Dawley female rats had a significantly (P ≤ 0.05) lower response than did group-housed Sprague–Dawley male rats, but group-housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats had a significantly (P ≤ 0.05) lower response than did group-housed spontaneously hypertensive male rats.

Figure 5.

Effect of single and group housing on heart rate responses (area under response curve) of male and female Sprague–Dawley (SD) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats after (A) 1 to 2 min of restraint in a rodent restrainer and injection of saline into the tail vein or (B) manual restraint and intraperitoneal injection of saline. Solid bars, rats housed 4 per cage; open bars, rats housed individually in a room with only single-housed rats; hatched bars, rats housed individually in the same room and at the same time group-housed rats. Means (n = 6 per group) with different letters within a sex and strain are statistically different (P < 0.05). *, Value for female rats significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of males of the same strain. #, Value for SHR significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of SD rats of the same sex.

Intraperitoneal injection.

The heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley male and female rats to manual restraint and intraperitoneal injection of saline were not significantly affected by housing conditions (Figure 5 B). In contrast, the heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive male rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) affected, in that those of group-housed rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than those of either of the singly housed groups, and those of singly housed rats exposed to group-housed animals were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater that those of rats kept in a dedicated single-housing room. The heart-rate responses of singly housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats exposed to group-housed animals were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than those of rats the other single-housing group but not from those of group-housed rats. Spontaneously hypertensive male and female rats had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) less prominent responses than did Sprague–Dawley rats, but there were minimal sex-associated differences within strains.

Stressful procedures.

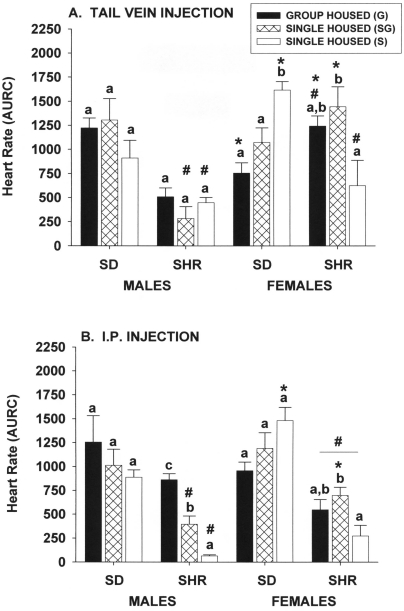

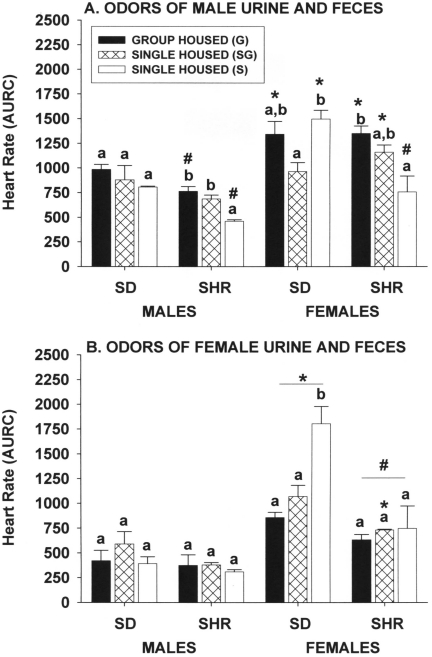

Odors of urine and feces from stressed male rats.

Housing conditions did not significantly affect heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley male rats to 15-min exposure to the odors of urine and feces (Figure 6 A). However, the heart-rate responses of group-housed spontaneously hypertensive male rats and those singly housed but kept in the same room as group-housing cages were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than those of rats maintained in a dedicated single-housing room. The heart-rate responses of female rats were quite different between the strains, in that singly housed Sprague–Dawley female rats in a dedicated housing room had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater responses than did those exposed to group-housed rats but not to those of group-housed animals. In spontaneously hypertensive female rats, those in group housing had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater responses than those of rats in dedicated single housing but not those kept in the room with group-housed rats. Spontaneously hypertensive male rats were generally less responsive than were Sprague–Dawley male rats (for example, responses of group-housed and one single-housed group of spontaneously hypertensive rats were significantly less [P ≤ 0.05] than those of respective Sprague–Dawley male rats), but strain-associated differences within female rats were minimal. Female rats of both strains had greater responses to the odors of male urine and feces than did male rats.

Figure 6.

Effect of single and group housing on heart rate responses (area under response curve) of male and female Sprague–Dawley (SD) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats after 15 min of exposure to the odors of urine and feces from (A) stressed male rats absorbed into a paper towel that was placed on the cage lid or (B) stressed female rats absorbed into a paper towel that was placed on the cage lid. Solid bars, rats housed 4 per cage; open bars, rats housed individually in a room with only single-housed rats; hatched bars, rats housed individually in the same room and at the same time group-housed rats. Means (n = 6 per group) with different letters within a sex and strain are statistically different (P < 0.05). *, Value for female rats significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of males of the same strain. #, Value for SHR significantly (P < 0.05) different from that of SD rats of the same sex.

Odors of urine and feces from stressed female rats.

Housing condition had no significant effect on the heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley or spontaneously hypertensive male rats or spontaneously hypertensive female rats (Figure 6 B). However, heart-rate responses in singly housed Sprague–Dawley female rats kept only with other singly housed rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than those of rats in either of the other 2 groups, which were not different from each other. Female Sprague–Dawley rats had significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater heart-rate responses than did Sprague–Dawley male rats, but this sex-associated effect was minimal in the spontaneously hypertensive strain. There were no significant strain-associated differences within male rats, but heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive female rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) less than those of Sprague–Dawley female rats.

Odors of dried rat blood.

Housing condition did not significantly affect the heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley male and female rats and spontaneously hypertensive female rats to 15-min exposure to the odor of dried rat blood (Figure 7 A). However, in spontaneously hypertensive male rats, heart-rate responses of group-housed rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater than rats kept in dedicated single housing but not from those singly housed but exposed to group-housed rats. Strain-associated effects in male rats were minimal, but heart-rate responses of spontaneously hypertensive female rats were generally less than those of Sprague–Dawley female rats (for example, responses of group-housed and one single-housed group of spontaneously hypertensive female rats were significantly [P ≤ 0.05] less than those of respective groups of Sprague–Dawley female rats). Within each strain, heart-rate responses in female rats were generally greater than those of male rats (for example, responses of group- and one single-housed female rats from both strains were significantly [P ≤ 0.05] greater than respective male rats of both strains).

Restraint for 60 min.

The very large heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive male rats to 60 min of physical restraint were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater in singly housed rats kept with group-housed animals than in rats of either of the other 2 groups, which were not different from each other (Figure 7 B). Housing conditions did not significantly affect heart-rate responses of Sprague–Dawley female rats, but responses of single-housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats maintained in a room with only singly housed rats were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) less than those of singly housed spontaneously hypertensive female rats kept with group-housed animals but not different from those of group-housed rats. Strain effects were most evident in male rats, with spontaneously hypertensive male rats exhibiting significantly (P ≤ 0.05) reduced responses than those of Sprague–Dawley male rats, whereas sex-associated effects were limited to the Sprague–Dawley strain, with responses of female rats being significantly (P ≤ 0.05) less than those of male rats.

Discussion

The current observations on the effects of housing conditions on the heart rate of undisturbed male and female spontaneously hypertensive rats extend our earlier reports on the effects of group compared with single housing in Sprague–Dawley rats42,44 and generally support the hypothesis that group housing reduces one index of stress (heart rate under undisturbed conditions) relative to single housing. However, the present results only partially confirm our earlier observations in the Sprague–Dawley strain. The differences between the current and former studies with Sprague–Dawley rats are believed to be due, at least in part, to the presence of both single- and group-housed animals in the same room at the same time in the current study, whereas in our previous reports group- and single-housed rats were not living in the animal room at the same time. In support of this view, the current results show significant differences at many time points during the day and night between undisturbed group-housed male and female rats of both strains and similar rats housed alone in a room with only single-housed rats (Figure 1). In contrast, many fewer differences were observed between group-housed rats and singly housed animals exposed to group-housed rats. These results suggest that there may be some form of animal-to-animal communication between group- and individually housed rats living in close proximity to each other. Such communication could alter the neural mechanisms that control the cardiovascular system. Although we have no direct evidence for animal-to-animal communication in the current study, there is a fairly extensive literature on auditory (ultrasonic calls) and olfactory (pheromone) signals thought to be used by rats for communication.1,6-13,16,19,24,37,40,48,49 That such signals may be involved when single- and group-housed rats are living in the same animal room should be investigated in future studies.

An alternate interpretation of our current results is that group housing has no effect on undisturbed heart rates relative to single housing and that our previous reports were flawed in design because group-and single-housed animals were not living in the same room at the same time. However, the current results with Sprague–Dawley rats confirmed our previous reports, suggesting that experiments separated in time are not necessarily flawed in design by the time separation. Rather, differences between single- and group-housed rats may be absent or present depending on whether they are living together in the same room at the same time (or not).

In contrast to what was observed during undisturbed conditions, there were no consistent differences between group and single housing on heart-rate responses to acute husbandry, experimental, or stressful procedures. The effects of housing conditions varied by procedure, with interactions existing with sex and strain. For example, heart-rate responses to one procedure (removal of a familiar conspecific) were significantly reduced in group- compared with single-housed rats of both sexes and strains. In contrast, heart-rate responses of group-housed rats to several other procedures were significantly less than those of single-housed rats of one sex or one strain (for example, cage change [spontaneously hypertensive female rats], introduction of a strange conspecific [Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive male rats], transport and subcutaneous injection [spontaneously hypertensive male rats and Sprague–Dawley female rats], tail-vein injection [Sprague–Dawley female rats], odor of female urine and feces [Sprague–Dawley female rats], prolonged physical restraint [Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive male rats]). For other procedures, group-housed rats had greater responses than did those singly-housed (for example, cage change [spontaneously hypertensive male rats], handling [spontaneously hypertensive female rats], subcutaneous injection [spontaneously hypertensive male and female rats], transport and subcutaneous injection [Sprague–Dawley female rats], intraperitoneal injection [spontaneously hypertensive male rats], odors of urine and feces from stressed male rats [spontaneously hypertensive male and female rats], odor of dried rat blood [spontaneously hypertensive male rats]). Finally, there were no significant differences between group- and single-housed animals for many other procedures. Therefore, the hypothesis that group housing universally reduces evoked heart-rate responses compared with single housing was not supported by the current observations.

Several explanations for these inconsistent effects are possible. First, probably not all procedures were perceived by the rats in the same way, given that the modalities and intensities of the inducing stimuli were likely very different. For example, cage change involves some novelty (new bedding) in an otherwise familiar setting. Handling is also novel; in addition, the rat may perceive it as life-threatening analogous to capture by a predator, although to the research staff, it is a gentling technique. Some procedures involve strong olfactory stimuli (odors of urine and feces, odor of dried rat blood), some of which may be perceived by the rat as alarm signals.21 Other procedures prevent escape from a potentially threatening situation (restraint in a rodent restrainer, manual restraint, and subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection). Still others involve social interactions with other rats (introduction of strange conspecific, removal of a familiar conspecific). Therefore, the neural mechanisms activated (or inactivated) by these procedures may be modulated to varying degrees by group housing.

Second, the modulating effects of group housing may not be sufficiently strong to alter the intense heart-rate responses induced by some procedures. This explanation does not seem likely, in that the very large heart-rate responses to prolonged physical restraint were reduced by group housing relative to single housing in male Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive rats (Figure 7 B).

Last, the interactions between housing condition, sex, and strain possibly contributed to the heterogeneity of the effects on the heart-rate responses of the rats. For example, Sprague–Dawley male rats showed the fewest occurrences where group housing significantly lowered heart-rate responses to the battery of procedures compared with those seen with single housing. In addition, there were no occurrences in Sprague–Dawley male rats where group housing showed greater responses than did single housed rats. By contrast, there were a number of procedures that induced greater heart-rate responses in group-housed spontaneously hypertensive male rats compared with their single-housed counterparts.

Regarding the influences of sex and strain, the results suggested that under undisturbed conditions, male rats had lower heart rate than did female rats when housed singly but not when housed in groups. This result suggests that male rats were less stressed by single housing than were female rats or that group housing reduced stress more in female rats than in male rats. A report showing that crowding calms female rats supports the latter possibility.5 In addition, Sprague–Dawley male and female rats had higher heart rate under undisturbed conditions than did their spontaneously hypertensive counterparts. This difference was expected, due to baroreceptor activation resulting from the ongoing hypertension in both male and female spontaneously hypertensive rats (data not shown).

The effects of sex on heart rate responses to acute procedures were mixed depending on the housing condition, procedure, and strain. Of the 36 possible housing–procedural comparisons within each strain, the heart-rate responses of male Sprague–Dawley rats were significantly greater than female rats 25% of the time, whereas heart-rate responses of female rats were significantly greater than male rats 33% of the time, with the sexes showing equal responses 42% of the time. A similar comparison within the spontaneously hypertensive strain showed 11%, 28%, and 61%, respectively. No clear pattern was evident across the types of procedures, except for those involving olfactory stimulation (odors of urine and feces from stressed male or female rats or the odor of dried rat blood), where female rats of both strains showed, if any, greater responses than did male rats. We believed initially that male rats may be more responsive to odors from stressed female rats if pheromones were involved, but the results did not support this view.

The effects of strain on the heart-rate responses to acute procedures were more homogeneous than were the effects of sex. However, the observation that Sprague–Dawley rats generally showed more prominent responses than did spontaneously hypertensive male rats or female rats was unexpected. Other reports have suggested that spontaneously hypertensive rats are more responsive to stress than are other strains,26,29,30,32,52 and we believed that procedurally induced changes in heart rate would be greater in the spontaneously hypertensive than Sprague–Dawley rats. The current results did not confirm these previously reported strain differences, and it is unclear why. Others have suggested that some methods used previously to measure cardiovascular parameters (for example, tail cuff) may have confounded the earlier studies; however, this explanation is not satisfactory, in that many of the reports cited used radiotelemetry methods to evaluate heart rate. Other factors, such as the source of the rats, different environmental conditions in the animal room (for example, light intensity, noise level, housing density), and dietary factors (for example, sodium levels or soy phytochemical content of the diet), may have contributed to the differences between the current and previously reported studies, but this possibility is only speculation and requires further experimentation.

In summary, group housing generally decreased the heart rate of undisturbed male and female rats relative to that of rats housed singly in a room with only single-housed rats but not relative to that of single-housed rats living in the room as group-housed animals. This outcome suggests some kind of signaling between group- and single-housed rats living in close proximity. Additional studies are required to confirm this hypothesis and to elucidate those signals. Additional studies also are needed to evaluate cardiovascular or other stress-related variables of group-housed rats living in a room with only group-housed animals and of both single- and group-housed animals living in rooms with various animal densities (that is, total number of animal in the room). In contrast to the observations in undisturbed conditions, heart-rate responses to acute procedures were not universally reduced by group housing. This difference is likely due to different modalities or intensities of the sensory stimuli evoked by the various procedures. In addition, sex and strain significantly interacted with housing condition. Additional studies are needed to determine the mechanisms by which housing, sex, and strain modulate evoked cardiovascular responses.

Acknowledgment

Supported by NIH grant RR13600.

References

- 1.Agren G, Olsson C, Uvnas-Moberg K, Lundeberg T. 1997. Olfactory cues from an oxytocin-injected male rat can reduce energy loss in its cagemates. Neuroreport 8:2551–2555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson NH, Devlin AM, Graham D, Morton JJ, Hamilton CA, Reid JL, Schork NJ, Dominiczak AF. 1999. Telemetry for cardiovascular monitoring in a pharmacological study: new approaches to data analysis. Hypertension 33:248–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azar TA, Sharp JL, Lawson DM. 2008. Effect of housing rats in dim light or long nights on heart rate. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 47:25–34 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brockway BP, Mills PA, Azar SH. 1991. A new method for continuous chronic measurement and recording of blood pressure, heart rate, and activity in the rat via radiotelemetry. Clin Exp Hypertens A 13:885–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown KJ, Grunberg NE. 1995. Effects of housing on male and female rats: crowding stresses males but calms females. Physiol Behav 58:1085–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brudzynski SM. 2005. Principles of rat communication: quantitative parameters of ultrasonic calls in rats. Behav Genet 35:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brudzynski SM. 2007. Ultrasonic calls of rats as indicator variables of negative or positive states: acetylcholine–dopamine interaction and acoustic coding. Behav Brain Res 182:261–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brudzynski SM. 2009. Communication of adult rats by ultrasonic vocalization: biological, sociobiological, and neuroscience approaches. ILAR J 50:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brudzynski SM, Bihari F, Ociepa D, Fu XW. 1993. Analysis of 22-kHz ultrasonic vocalization in laboratory rats: long and short calls. Physiol Behav 54:215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brudzynski SM, Chiu EM. 1995. Behavioural responses of laboratory rats to playback of 22-kHz ultrasonic calls. Physiol Behav 57:1039–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brudzynski SM, Ociepa D. 1992. Ultrasonic vocalization of laboratory rats in response to handling and touch. Physiol Behav 52:655–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brudzynski SM, Pniak A. 2002. Social contacts and production of 50-kHz short ultrasonic calls in adult rats. J Comp Psychol 116:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgdorf J, Kroes RA, Moskal JR, Pfaus JG, Brudzynski SM, Panksepp J. 2008. Ultrasonic vocalizations of rats (Rattus norvegicus) during mating, play, and aggression: behavioral concomitants, relationship to reward, and self-administration of playback. J Comp Psychol 122:357–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caplea A, Seachrist D, Dunphy G, Ely D. 2000. SHR Y chromosome enhances the nocturnal blood pressure in socially interacting rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279:H58–H66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavigelli SA, Monfort SL, Whitney TK, Mechref YS, Novotny M, McClintock MK. 2005. Frequent serial fecal corticoid measures from rats reflect circadian and ovarian corticosterone rhythms. J Endocrinol 184:153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vry J, Benz U, Schreiber R, Traber J. 1993. Shock-induced ultrasonic vocalization in young adult rats: a model for testing putative antianxiety drugs. Eur J Pharmacol 249:331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fryer TB, Lund GF, Williams BA. 1978. An inductively powered telemetry system for temperature, EKG, and activity monitoring. Biotelem Patient Monit 5:53–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gala RR, Haisenleder DJ. 1986. Restraint stress decreases afternoon plasma prolactin levels in female rats. Influence of neural antagonists and agonists on restraint-induced changes in plasma prolactin and corticosterone. Neuroendocrinology 43:115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haney M, Miczek KA. 1993. Ultrasounds during agonistic interactions between female rats (Rattus norvegicus). J Comp Psychol 107:373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harkin A, Connor TJ, O'Donnell JM, Kelly JP. 2002. Physiological and behavioral responses to stress: what does a rat find stressful? Lab Anim (NY) 31:42–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauser R, Marczak M, Karaszewski B, Wiergowski M, Kaliszan M, Penkowski M, Kernbach-Wighton G, Jankowski Z, Namiesnik J. 2008. A preliminary study for identifying olfactory markers of fear in the rat. Lab Anim (NY) 37:76–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawley ES, Hargreaves EL, Kubie JL, Rivard B, Muller RU. 2002. Telemetry system for reliable recording of action potentials from freely moving rats. Hippocampus 12:505–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmquest DL. 1970. A digital recording system for body temperature telemetry from small animals. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 17:356–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kikusui T, Takigami S, Takeuchi Y, Mori Y. 2001. Alarm pheromone enhances stress-induced hyperthermia in rats. Physiol Behav 72:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer K, Grimbergen JA, van der Gracht L, van Iperen DJ, Jonker RJ, Bast A. 1995. The use of telemetry to record electrocardiogram and heart rate in freely swimming rats. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 17:107–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krukoff TL, MacTavish D, Jhamandas JH. 1999. Hypertensive rats exhibit heightened expression of corticotropin-releasing factor in activated central neurons in response to restraint stress. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 65:70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemaire V, Mormede P. 1995. Telemetered recording of blood pressure and heart rate in different strains of rats during chronic social stress. Physiol Behav 58:1181–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lestage P, Vitte PA, Rolinat JP, Minot R, Broussolle E, Bobillier P. 1985. A chronic arterial and venous cannulation method for freely moving rats. J Neurosci Methods 13:213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li SG, Lawler JE, Randall DC, Brown DR. 1997. Sympathetic nervous activity and arterial pressure responses during rest and acute behavioral stress in SHR versus WKY rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 62:147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundin S, Ricksten SE, Thoren P. 1983. Interaction between mental stress and baroreceptor control of heart rate and sympathetic activity in conscious spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive (WKY) rats. J Hypertens Suppl 1:68–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattheij JA, van Pijkeren TA. 1977. Plasma prolactin in undisturbed cannulated male rats: effects of perphenazine, frequent sampling, stress, and castration plus oestrone treatment. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 84:51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDougall SJ, Paull JR, Widdop RE, Lawrence AJ. 2000. Restraint stress: differential cardiovascular responses in Wistar–Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 35:126–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meehan WP, Tornatzky W, Miczek KA. 1995. Blood pressure via telemetry during social confrontations in rats: effects of clonidine. Physiol Behav 58:81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy HM, Wideman CH, Aquila LA, Nadzam GR. 2002. Telemetry provides new insights into entrainment of activity wheel circadian rhythms and the role of body temperature in the development of ulcers in the activity-stress paradigm. Integr Physiol Behav Sci 37:228–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pitman DL, Natelson BH, Pitman JB, Schilling AM, Ottenweller JE. 1989. A methodological improvement for experimental control and blood sampling in rats. Physiol Behav 45:205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Royo F, Bjork N, Carlsson HE, Mayo S, Hau J. 2004. Impact of chronic catheterization and automated blood sampling (Accusampler) on serum corticosterone and fecal immunoreactive corticosterone metabolites and immunoglobulin A in male rats. J Endocrinol 180:145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sachs BD. 1997. Erection evoked in male rats by airborne scent from estrous females. Physiol Behav 62:921–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato K, Chatani F, Sato S. 1995. Circadian and short-term variabilities in blood pressure and heart rate measured by telemetry in rabbits and rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 54:235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schierok H, Markert M, Pairet M, Guth B. 2000. Continuous assessment of multiple vital physiological functions in conscious freely moving rats using telemetry and a plethysmography system. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 43:211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarting RK, Jegan N, Wohr M. 2007. Situational factors, conditions, and individual variables which can determine ultrasonic vocalizations in male adult Wistar rats. Behav Brain Res 182:208–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharp J, Azar T, Lawson D. 2005. Effects of a cage enrichment program on heart rate, blood pressure, and activity of male Sprague–Dawley and spontaneously hypertensive rats monitored by radiotelemetry. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 44:32–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharp J, Zammit T, Azar T, Lawson D. 2003. Stress-like responses to common procedures in individually and group-housed female rats. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 42:9–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharp JL, Azar TA, Lawson DM. 2003. Does cage size affect heart rate and blood pressure of male rats at rest or after procedures that induce stress-like responses? Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 42:8–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharp JL, Zammit TG, Azar TA, Lawson DM. 2002. Stress-like responses to common procedures in male rats housed alone or with other rats. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 41:8–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith SW, Gala RR. 1977. Influence of restraint on plasma prolactin and corticosterone in female rats. J Endocrinol 74:303–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uemura K, Kawada T, Sugimachi M, Zheng C, Kashihara K, Sato T, Sunagawa K. 2004. A self-calibrating telemetry system for measurement of ventricular pressure–volume relations in conscious, freely moving rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287:H2906–H2913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van den Buuse M. 1994. Circadian rhythms of blood pressure, heart rate, and locomotor activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats as measured with radiotelemetry. Physiol Behav 55:783–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wohr M, Houx B, Schwarting RK, Spruijt B. 2008. Effects of experience and context on 50-kHz vocalizations in rats. Physiol Behav 93:766–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wohr M, Schwarting RK. 2007. Ultrasonic communication in rats: can playback of 50-kHz calls induce approach behavior? PLoS ONE 2:e1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu S, Talwar SK, Hawley ES, Li L, Chapin JK. 2004. A multichannel telemetry system for brain microstimulation in freely roaming animals. J Neurosci Methods 133:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang BL, Zannou E, Sannajust F. 2000. Effects of photoperiod reduction on rat circadian rhythms of BP, heart rate, and locomotor activity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279:R169–R178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W, Thoren P. 1998. Hyper-responsiveness of adrenal sympathetic nerve activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats to ganglionic blockade, mental stress, and neuronglucopenia. Pflugers Arch 437:56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]