Abstract

Cryopreserved amniotic membrane modulates adult wound healing by promoting epithelialization while suppressing stromal inflammation, angiogenesis and scarring. Such clinical efficacies of amniotic membrane transplantation have been reported in several hundred publications for a wide spectrum of ophthalmic indications. The success of the aforementioned therapeutic actions prompts investigators to use amniotic membrane as a surrogate niche to achieve ex vivo expansion of ocular surface epithelial progenitor cells. Further investigation into the molecular mechanism whereby amniotic membrane exerts its actions will undoubtedly reveal additional applications in the burgeoning field of regenerative medicine. This article will focus on recent advances in amniotic membrane transplantation and expand to cover its clinical uses beyond the ocular surface.

Keywords: amniotic membrane, cryopreservation, fibrosis, inflammation, ocular surface, reconstruction, regenerative medicine, tissue engineering, wound healing

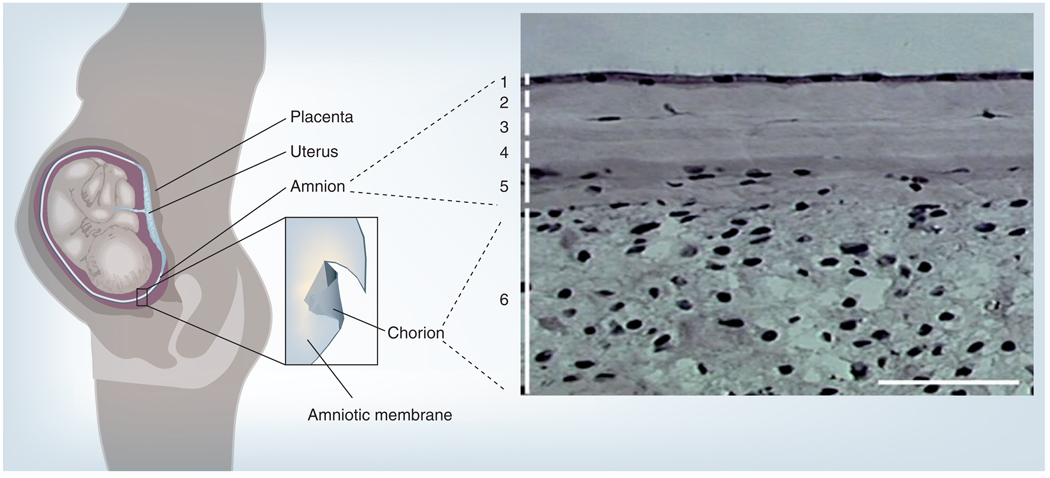

The amniotic membrane (AM) shares the same cell origin as the fetus (i.e., the fertilized egg). Embryologically, the AM, together with the placenta, is derived from the epiblast – the outer cell mass – while the fetus is derived from the inner cell mass. Histologically, AM consists of a single epithelial layer, a thick basement membrane and an avascular stroma (Figure 1). A number of mechanisms have been put forth to explain the AM’s biological actions in modulating adult wound healing toward the fetal direction with anti-inflammation, antiscarring and antiangiogenesis (for a review see [1]).

Figure 1. The amniotic membrane in the uterus and its histology.

The placental membrane consists of the outer chorion (depicted in dark grey) and the inner amniotic membrane (depicted in light grey). Histologically, amniotic membrane is composed of (1) a monolayer of simple epithelium with a basement membrane, and an avascular stroma, which can further be subdivided into (2) compact, (3) fibroblast, (4) sponge and (5) reticular layers. Amniotic membrane is fused with (6) the cytotrophoblast layer of the chorion.

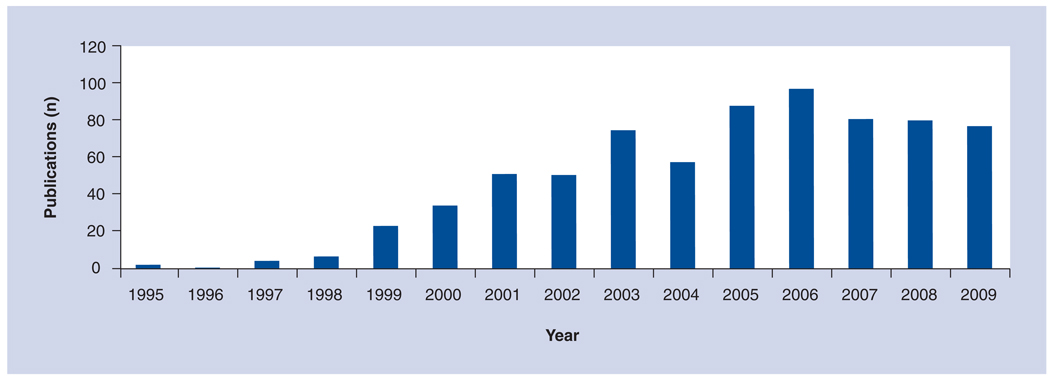

When properly processed and preserved, preferably using the patented cryopreservation method, this semitransparent and resilient tissue has been successfully used as a surgical graft for a wide range of ophthalmic indications (for reviews see [1–5]). Specifically, over the last 15 years, over 800 peer-reviewed publications have been put forward describing how AM transplantation (AMT) has been performed to treat a variety of ophthalmic indications (Figure 2). The majority of the studies testify to the clinical efficacy of AMT in gearing adult wound healing toward regeneration with minimal inflammation and scarring, suggesting that AM, like fetal tissue, carries a similar feature that may not only promote healing but also facilitate regeneration [6,7]. To be familiar with AMT uses for ocular surface reconstruction, readers are encouraged to consult other reviews [1–5]. Owing to space limitations, it has not been possible to cite all of the relevant publications. This article will focus on recent advances in AMT and expand to cover its clinical uses beyond the ocular surface.

Figure 2. Publications released between 1995 and 2009 describing the use of amniotic membrane transplantation in ophthalmology.

Mechanism of action

Adult wound healing is triggered by activating innate immunity and is characterized by inflammation in the acute phase, granulation tissue formation in the intermediate phase, and scarring in the chronic phase. This wound-healing process is mediated by a number of cell types and orchestrated by complex arrays of growth factors, cytokines, chemokines and nonprotein mediators. A number of studies have been conducted to explore the mechanism whereby the AM may exert its therapeutic action to suppress inflammation and scarring (reviewed in [1]). Herein, we will update recent reports regarding AM’s anti-inflammatory and antiscarring actions, and extend our discussion to its antiangiogenic action. It remains unclear whether such therapeutic actions are directly or indirectly linked to promote epithelial healing, differentiation and regeneration.

Anti-inflammatory action

Previous studies have demonstrated that the AM contains anti-inflammatory mediators and its action may require close contact with its stromal matrix. When AM was used as a temporary patch, polymorphonuclear cells rapidly adhered to its stromal side in rabbit models [8] and in human patients with chemical burns [9,10], where these adherent cells underwent rapid apoptosis [9,11]. Similarly, mononuclear cells including lymphocytes and macrophages also underwent rapid apoptosis when adhered to the AM stroma in a murine model of herpes simplex virus-induced necrotizing keratitis [12–15]. Such a unique anti-inflammatory action of the AM by promoting cellular apoptosis has been recapitulated in an in vitro culturing system using murine macrophages [16]. He et al. recently reported that such an inhibitory activity was retained in the water-soluble AM extract (AME) [17]. Their results showed that AME downregulates the expression of CD80, CD86 and major histocompatibility complex class II antigen, inhibits cell viability, and enhances cell apoptosis. Recently, HC•HA, a covalent-linked complex formed by hyaluronan (HA) and a heavy chain (HC) of inter-α-inhibitor, has been biochemically purified from AME and was found to exert more potent anti-inflammatory action than HA in the same in vitro model [18].

Antiscarring action

Although the aforementioned anti-inflammatory actions may indirectly contribute to AM’s antiscarring actions, several lines of experimental evidence also support the notion that the AM stromal matrix exerts a direct antiscarring effect on ocular tissue fibroblasts by suppressing TGF-β signaling at the transcriptional level [19,20]. Human AM transplanted into the rabbit corneal stromal pocket reduces myofibroblast differentiation elicited by invading epithelial cells and in a tissue culture model of collagen gel contraction [21]. The AM stromal matrix is also capable of maintaining the characteristic dendritic morphology and keratocan expression of human [22,23], murine [24] and monkey [25] keratocytes in culture. Therefore, the suppressive effect of TGF-β signaling is not only pathologically important in preventing scar formation, but also physiologically important in maintaining the normal keratocyte phenotype. Recently, He et al. further demonstrated that HC•HA purified from AME, as well as reconstituted from defined components, exerts a potent suppressive effect on the activity of the TGF-β promoter. These data suggest that both the anti-inflammatory and antiscarring actions might be mediated by HC•HA [18].

Antiangiogenic activity

The antiangiogenic function of cryopreserved AM was first recognized by Kim and Tseng when human AM was transplanted to reconstruct the corneal surface in a rabbit model of chemical injuries [26]. Besides a reduction of inflammation and scarring, AM-transplanted corneal surfaces also show reduced vascularization [26,27]. A randomized, prospective clinical study demonstrated that graft vascularization after pterygium surgery was more delayed in AMT than in conjunctival autograft [28]. This antiangiogenic action has also been exploited during corneal surface reconstruction in conjunction with transplantation of corneal epithelial stem cells from the limbus [2–31]. Angiogenesis involves the activation of vascular endothelium or endothelial progenitor cells through a series of cellular events including survival, migration, proliferation and tube formation. Kobayashi et al. noted that the conditioned medium of cultured amniotic epithelial and mesenchymal cells contains antiangiogenic activity, although the identity of this activity remains obscure [32]. Pigment epithelium-derived factor, a potent antiangiogenic factor [33], was predominantly found in the AM basement membrane [34]. Transcripts and proteins of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase and transcript of thrombospondin-1 – that is, potential antiangiogenic factors – are expressed by both human amniotic epithelial and mesenchymal cells [35]. However, the roles of these three proteins in delivering antiangiogenic actions in the AM cannot be ascertained because their protein levels are negligible in the medium following the incubation of human AM [36]. A soluble AM extract prepared by boiling and homogenization was shown to prevent angiogenesis in a rat model of corneal neovascularization induced by alkali burn, and by suppressing the viability and tube formation of cultured human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) [27]. Recently, we have noted that HC•HA suppresses HUVEC viability more significantly than HA and AME, and that such suppression is not mediated by CD44 [Shay et al. 2010, Manuscript Submitted]. HC•HA also causes HUVEC to become small and rounded, with a decrease in spreading and filamentous actin. Without promoting cell detachment or death, HC•HA dose-dependently inhibits HUVEC proliferation and is 100-fold more potent than HA. Migration triggered by VEGF and tube formation are also significantly inhibited by HC•HA. These effects explain why AM is developmentally avascular. Collectively, the aforementioned results also indicate that HC•HA is a promising candidate serving as an active component responsible for AM’s anti-inflammatory, antiscarring and antiangiogenic actions when transplanted to the ocular surface. Further investigation is underway to explore the therapeutic potential of HC•HA in diseases manifesting pathogenic angiogenesis. However, due to the complexity of the angiogenesis pathway network, there are likely other factors that may exert AM’s antiangiogenic action. Further study is necessary to delineate how these factors may interplay in exerting the inhibitory action of angiogenesis.

Antipain action

A rapid relief of pain by AMT has been clinically observed in treating chemical burns [10], severe bacterial keratitis [37], Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) with or without toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) [38,39], and acute stage of painful bullous keratopathy [40]. In addition, recently the insertion of a sheet of cryopreserved AM has also been shown to reduce pain that is frequently incurred during irradiation therapy for ocular tumors [41]. This could be an important factor in choosing AMT over the conjunctival autograft for pterygium surgery. Although one may attribute AM’s effect in relieving pain to its anti-inflammatory action, we suspect that such a rapid action in pain relief may be mediated by an as-yet unknown antipain action that deserves further investigation.

AM as a surrogate niche or substrate for ex vivo expansion of ocular surface epithelial progenitor cells

The combination of the aforementioned effects may explain why AM has been used as an ideal substrate to cultivate epithelial progenitor cells of the conjunctival epithelium [42–46], corneal epithelium [47–50], limbus [45,51–59], oral mucosa [49,60–62] and corneal endothelium [63,64]. The techniques used in these studies include using either explants or suspension culture method to isolate epithelial cells, and then culture on intact or denuded AM with or without a mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line (3T3) feeder layer. Recently, Chen et al. reported a novel finding that AM epithelial cells can function as a surrogate feeder layer to support the growth of corneal epithelial stem cells [65]. The resultant cultivated cells and AM were transplanted in normal rabbits [61,66], as well as in limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) rabbits [61,67] and rat models for short-term study [68]. It has also been used in limbal deficient rabbits for long-term study [69]. Currently, this composite tissue is being transplanted to restore vision as well as the structure and the function of damaged ocular surfaces in humans [45,62,70–72]. These clinical effects are based on the premise that AM facilitates epithelialization, prolongs epithelial stem cell survival, and reduces inflammation and scarring. It remains unclear which ex vivo expansion protocols are the most effective. Further investigation of the molecular mechanism whereby AM exerts these therapeutic actions should help us unravel other therapeutic potentials in the burgeoning fields of reconstruction, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Clinical ophthalmic indications

Transplantation of human AM in ocular disorders was introduced into ophthalmology more than 60 years ago. Since 1995, AMT has been successfully applied for ocular surface reconstruction in patients with a variety of ophthalmic indications. The increasing popularity of AMT is likely influenced by the method of cryopreservation, which was introduced in 1997 [73]. There are two major modes of transplanting AM as a permanent surgical graft or a temporary biological bandage/patch (Boxes 1 & 2).

Box 1. Indications for amniotic membrane as a permanent graft.

Corneal surface reconstruction

Neurotrophic persistent epithelial defect with ulceration

Sterile corneal stromal thinning, descemetocele and perforation

Infectious keratitis and scleritis

Symptomatic bullous keratopathy

Band keratopathy, scar or tumor

Partial limbal stem cell deficiency

Conjunctival surface reconstruction

Pterygium and pinguecula

Symblepharon

Fornix reconstruction

Conjunctivochalasis

Tumors

In conjunction with other surgeries

Limbal conjunctival autograft for unilateral total limbal stem cell deficiency

Keratolimbal allograft for bilateral total limbal stem cell deficiency

Tenonplasty for scleral melt

Glaucoma (high-risk trabeculectomy, leaking blebs, tube exposure)

Strabismus

Box 2. Indications for amniotic membrane as a temporary biological bandage/patch.

Neurotrophic persistent epithelial defect without ulceration

Acute chemical/thermal burn

Acute SJS/TEN

High-risk corneal graft

Postinfectious keratitis

Recurrent epithelial erosion

Following superficial keratectomy to remove abnormal epithelium, scar or calcium

SJS: Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN: Toxic epidermal necrolysis.

First, when AM is used as a permanent graft, AM is used to fill in the tissue defect, which is caused by tissue that is destroyed by the disease process or created by surgeries, so that host cells will grow over or into the membrane, and the membrane will subsequently be integrated into the host tissue. The tissue can be a part of the ocular surface or a tissue plane underneath. The tissue planes of interest are a Tenon substitute between the conjunctiva and the sclera (Tenon replacement or covering a glaucoma drainage tube), a muscle sheath substitute between the conjunctiva and the muscle, and underneath the scleral flap of a trabeculectomy. The main goal of this mode is to prevent scarring so as to restore the tissue integrity and function, including vision, or to maintain ocular motility and aqueous fluid filtration. In this mode, AM can be used as a single or multiple layers, and secured to the host tissue by sutures or fibrin glue in a sutureless manner.

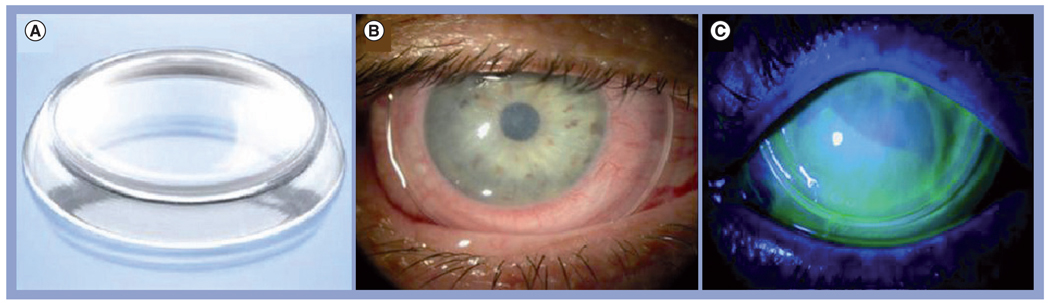

Second, when AM is used as a temporary biological bandage/patch, the main goal is to suppress acute or chronic host tissue inflammation caused by diseases or surgery so as to promote healing with minimal scarring. AM can be sutured as a bandage (lens), dressing or patch to cover both healthy host tissue and the site of interest at the same time so that the host epithelium heals underneath. Recently, AM has also been delivered to cover the corneal surface via a US FDA-approved medical device, termed ProKera® (Bio-Tissue, Inc., FL, USA) without sutures (Figure 3). Upon healing, AM is usually dissolved or removed in the practitioner’s office. Occasionally, both a patch and a graft are used together, in which case the patch is used as a protective shield to ensure epithelialization of the AM used as a graft.

Figure 3. Prokera® and its application in ocular surface.

(A) ProKera® is a dual-ring system that fastens a sheet of semitransparent cryopreserved amniotic membrane. It enhances the ease of patient care in many difficult corneal diseases. It is inserted under topical anesthesia into the upper fornix first, and then tucked under the lower lid. (B) A slit-lamp photograph depicts its appearance when inserted in the eye. (C) The status of epithelialization can be monitored by fluorescein staining and the intraocular pressure can be measured by Tonopen™ without having ProKera removed.

The aforementioned sutureless approaches shorten the surgical time, permit topical anesthesia and eliminate suture-induced inflammation. More importantly, they also facilitate patient care by delivering the aforementioned AM’s biological actions in the clinic or at the bedside without delay. As a result, they may radically change the outcome in such diseases as chemical burns and SJS/TEN that require acute intervention. Other new therapeutics will be unveiled once we gain a better understanding of how AM works at the molecular level.

Corneal surface reconstruction

Persistent epithelial defect

Please refer to Boxes 1 & 2. Persistent epithelial defect (PED) is often caused by microtrauma, neurotrophic keratopathy and exposure. Conventional treatment includes correcting the underlying condition, suppressing the inflammation, and promoting the healing process using tears. Because PED is usually ‘neurotrophic’, which disrupts the neural reflexes that control tear secretion and blinking, resulting in a severe form of dry eye, the first-line management should start with punctal occlusion [74], followed by autologous serum or the insertion of a high DK bandage contact lens. If PED still does not respond to the aforementioned treatment, the next approach is AMT. If the epithelial defect has no/minimal stromal loss, AM can be used as a biological bandage by either inserting ProKera or suturing a single layer of AM after debridement of the loose epithelium. A small temporary tarsorrhaphy may be required to narrow the lid fissure in patients with decreased and incomplete blinking (exposure).

If there is notable stromal loss, AM (one or multiple layers) can be used as a permanent graft to restore this loss. A piece of AM with stromal surface facing down is secured to the healthy stroma next to the ulcer edge with 10-0 sutures (either interrupted or running). Another layer of AM may be used to cover the entire cornea, limbus and part of the conjunctiva in the same manner as a bandage lens, and suture it in the same way. Healing can be monitored by fluorescein staining through the membrane, which is expected to stay in place for 2 weeks. If the AM somehow dissolves within 1 week while PED shows minimal improvement, it means that there is still unwanted exposure. After complete healing, the application of a high DK contact lens for 1–2 weeks is recommended. If there is a recurrence of superficial punctate keratopathy on the exposure zone, another option would be an extended wear of a high DK bandage contact lens or a permanent tarsorrhaphy. In addition, the patient is encouraged to blink with complete closure. AMT has shown an average success of 79% (range: 67–91%), with rapid and complete healing of PED within 1–4 weeks [75–80]. Recently, Seitz et al. used a sandwich technique to successfully treat PED after penetrating keratoplasty [81]. Using laser scanning in vivo confocal microscopy, Nubile et al. disclosed epithelial migration under rather than over the membrane during the period of 1–4 weeks of epithelialization in patients with chemical burns and PED when AMT is used as a temporary biological bandage [82].

Deep corneal ulcer, descemetocele & perforation

Conventional surgical treatments to descemetocele and perforation usually include lamellar or full-thickness corneal transplantation, tarsorrhaphy and conjunctival flap. AMT offers the advantage of avoiding potential allograft rejection and postoperative astigmatism of tectonic corneal grafts. Even if corneal transplantation is needed, the success rate is improved if performed on an eye that underwent AMT to reduce inflammation. For deeper stromal ulcers down to descemetocele, multiple layers of AM were used to restore the normal corneal thickness as well as in corneal perforations from 0.5 to 3 mm with or without additional tissue adhesive with high success rates (73–93%) [76,77,79,80,83,84]. Recently, Kim et al. used fibrin glue-assisted augmented AMT in ten patients with large corneal perforations up to 5 mm and noted 90% success in complete epithelialization over the AM [85].

Infectious keratitis

The principal therapeutic goals for infectious keratitis are to eliminate pathogens and to prevent irreversible corneal structural damage. Corneal destruction may be caused directly by infectious agents and/or by the associated inflammatory response. Severe bacterial keratitis requires immediate treatment with intensive topical broad-spectrum antibiotics, which are potentially toxic to the corneal epithelium and contribute to a prolonged corneal epithelial defect. AMT with sutures has been used as an adjuvant treatment for acute severe infectious keratitis [86,87]. AM counterbalances the epithelial toxicity of fortified antibiotic eye drops while exerting as-yet unclear antimicrobial actions and acting as a long-term drug-delivery system. Sheha et al. recently reported the successful use of ProKera in three cases with severe microbial keratitis [37]. Pain was significantly relieved and inflammation was markedly reduced within 96 h in all cases. The corneal epithelial defect and stromal ulceration rapidly healed, resulting in visual improvement. Clinically, we were assured by the findings that AMT itself does not impede the penetration of topical antibiotics [86], and that AM soaked with antibiotics actually prolong the bactericidal effect [88], thus allowing one to use less topical antibiotics but also avoiding the antimicrobial’s potential cytotoxic effect.

Symptomatic bullous keratopathy

Bullous keratopathy is a disorder caused by corneal endothelial decompensation due to degeneration (Fuch’s endothelial dystrophy), surgical trauma, intractable glaucoma or previous corneal graft failure. Corneal transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with visual potential. Recently, Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty has been shown to be a promising procedure to achieve the goal of restoring vision without replacing the cornea stroma. Thus, for patients that will receive Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty, either AMT or anterior stromal puncture is contraindicated. However, for those without visual potential, relief of pain and recurrent erosion relies on several surgical treatments, including cauterization, anterior stromal puncture, excimer laser photoablation and conjunctival flap. As an effective alternative, AMT can achieve pain relief with an overall success rate of more than 85% [4,89–92]. The AM-covered corneal surface heals in 3 weeks with reduced inflammation, and only fewer than 10% of eyes show recurrent surface breakdown. Recently, Chansanti et al. noted postoperative relief of pain in 14 eyes (82.4%) and complete corneal epithelial healing in 15 eyes (88.2%) after AMT [93]. Sonmez et al. performed anterior stromal micropuncture and AMT in five eyes with painful bullous keratopathy [40]. All showed an intact, smooth corneal epithelial surface 1 month after the procedure, and no patients developed recurrent bullae formation during an average follow-up period of 21 months.

Acute SJS/TEN

Amniotic membrane can also be used to suppress inflammation, promote healing, and prevent scarring in patients suffering from SJS with or without TEN at the acute stage [38,39,94–97]. The conventional managements at intensive care and burn units are usually reserved for life-threatening problems, and thus are frequently inadequate to address ocular inflammation and ulceration. As a result, patients suffering are frequently left with a blinding disease owing to scarring-induced late complications. To cover the entire ocular surface from lid margin to lid margin, AM is secured to the fornix with a bolster on the lid skin. Gregory et al. [98] and Shay et al. [99] have reviewed the literature up to 2009 and found that AMT performed within 2 weeks after the onset of disease effectively aborts inflammation and facilitates rapid healing in AM-covered areas, thus preventing pathogenic cicatricial complications at the chronic stage in 12 eyes. Recently, Shay et al. [99] and Shammas et al. [97] reported several case of SJS/TEN that received ProKera at the acute stage, and noted restoration of normal corneal vision. However, because this devastating ocular surface disease usually elicits inflammation and ulceration in such hidden areas as the lid margin, the tarsus and the fornix, AM extended to cover the entire ocular surface is necessary. Future improvement to expand the size of ProKera to reach the fornix and the tarsus is important.

Limbal stem cell deficiency

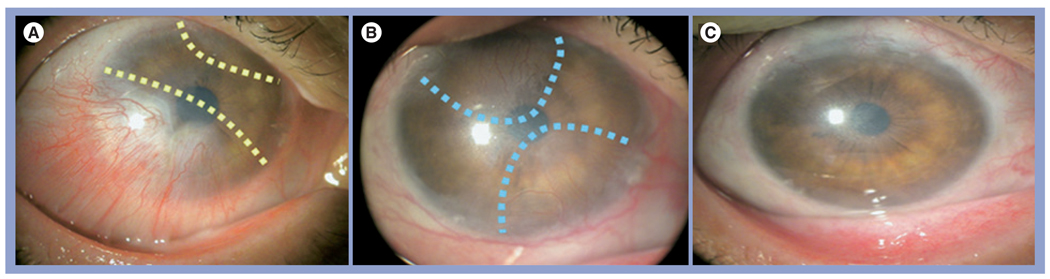

When limbal epithelial stem cells are destroyed or become dysfunctional, a pathological state known as LSCD manifests. The hallmark of LSCD is the conjunctivalization of the cornea, and is frequently associated with superficial vascularization and compromised corneal surface (reviewed in [100]). LSCD can be found with a number of corneal diseases such as chemical burns, SJS, aniridia, peripheral keratitis and severe limbitis (reviewed in [101]). Patients with LSCD suffer from a severe loss of vision and bothersome photophobia, and their vision cannot be corrected by conventional penetrating keratoplasty. Therefore, it is important to accurately diagnose LSCD because erroneous diagnosis may subject the patient to unnecessary surgeries. Correct diagnosis requires impression cytology. For eyes with partial LSCD, the corneal surface can be reconstructed by debridement of the conjunctivalized epithelium with [102–104] or without [105] AMT with sutures. Previous studies have shown that in eyes with partial LSCD, AM promotes expansion of remaining limbal epithelial stem cells [29,102–104]. To avoid suture-related disadvantages and complications, Kheirkhah et al. recently reported successful reconstruction of the corneal surface in nine patients with nearly total LSCD using fibrin glue [106]. The first stage begins with the removal of conjunctivalized pannus from the more severely involved limbal/corneal area, placement of the AM by fibrin glue and the insertion of ProKera on the top (Figure 4). Afterwards, the less severely involved area is reconstructed in the same manner.

Figure 4. Amniotic membrane transplant ‘stagewise approach’ for nearly total limbal stem cell deficiency.

(A) The first-stage surgery directed to conjunctivalized pannus marked by broken lines resulted in (B) a full recovery of the limbal and corneal surfaces 3 months after surgery. (B) The second-stage surgery was directed to the residual pannus from the remaining less-involved areas marked by broken lines. (C) As a result, the cornea recovered a stable and smooth epithelium without vascularization and much less cloudiness 21 months later.

Reprinted with permission from [106].

For eyes inflicted with total LSCD, the transplantation of limbal epithelial stem cells is required. When total LSCD involves only one eye, successful reconstruction can be achieved by transplanting autologous limbal epithelial stem cells from the fellow eye in a procedure termed ‘conjunctival limbal autograft’ (CLAU) [107] (also see references cited in reviews [108–111]). Because the source of limbal epithelial stem cells is autologous, there is no risk of immune rejection and hence no need for systemic immunosuppression. A number of studies have shown overwhelming (>80%) successful visual outcomes with regression of neovascularization and improvements in corneal transparency after CLAU (reviewed in [112]). AMT has been used not only to facilitate the growth of CLAU on the recipient eye, but also to restore the limbal integrity of the donor site [113–115]. To reduce the potential insult to the healthy donor in CLAU, Kheirkhah et al. reported successful corneal reconstruction in a patient with total LSCD using one strip of CLAU that spans only 2 clock hour limbal arc lengths [116]. The size of CLAU can be significantly reduced to this size because AMT has been used as a permanent surgical graft in both eyes with fibrin glue and as a temporary biological bandage via the insertion of ProKera.

For eyes with bilateral LSCD, Liang et al. reported the long-term outcomes of keratolimbal allograft (KLAL) when AMT was used as both surgical graft and biological bandage in conjunction with systemic combined immunosuppression [117]. They further noted that it is vital to take corrective measures before, during and after the surgery to restore the ocular surface defenses so that a stable tear film can be maintained. For eyes with conjunctival inflammation or cicatricial complications such as pathogenic symblepharon, it is important to correct these deficiencies before surgically transplanting limbal epithelial stem cells (for details, see ‘Conjunctival surface reconstruction’ section). These measures can augment AM’s therapeutic actions in restoring a healthy limbal stromal niche with less inflammation and scarring that may support the success of transplanted autologous or allogeneic limbal grafts.

Conjunctival surface reconstruction

When a large conjunctival lesion is surgically removed, the conjunctival defect is normally healed by the surrounding conjunctiva with granulation and scarring, which may lead to disfiguration and motility restriction of the extraocular muscles or the lid’s blinking action. To avoid such problems, conjunctival autograft from the same or the fellow eye is frequently used. However, some patients may not have healthy conjunctival tissue to spare, and further removal of the uninvolved conjunctiva might put the patient at additional risk. Therefore, AMT has been used as an alternative graft for conjunctival surface reconstruction. Studies showed that the defect covered by AM heals rapidly, and the resultant surface is less inflamed with minimal scarring in successful cases [118–120].

Pterygium

There are a wide variety of surgical methods but very few clinical guidelines on the optimal treatment of primary or recurrent pterygium. The most common complication of pterygium surgery is postoperative recurrence. Simple surgical excision has a high recurrence rate up to 82%. The use of conjunctival/limbal autografts or AMT, mytomycin C (MMC), β-irradiation, or other adjunctive therapies at the time of excision significantly decrease the recurrence of pterygium. AMT has been regarded as an alternative and effective method to treat primary and recurrent pterygium, with a recurrence rate ranging from 0 to 64% in primary pterygium [121,122] and 0 to 52.6% in recurrent pterygium [123,124]. The recurrence is known to be highly associated with postsurgical inflammation. Any form of inflammatory insult to the ocular surface environment may activate the transformation of remaining pterygial body fibroblasts into an invasive phenotype identical to that of the pterygium head fibroblasts [125], thereby increasing the risk of pterygium recurrence. Kheirkhah et al. observed postoperative inflammation in 27 eyes with primary or recurrent pterygia that underwent extensive removal of subconjunctival fibrovascular tissue and intraoperative application of 0.04% MMC in the fornix, followed by AMT by using either fibrin glue or sutures [126]. They found that conjunctival inflammation around the surgical site was noted in 40.7% of eyes and was significantly more common in eyes with sutures than in those with fibrin glue. If left untreated, persistent inflammation may lead to a poor surgical outcome such as granulation formation or recurrence.

It has been recognized that pterygium’s overgrowth of fibrovascular tissue extends from the caruncle and fornix region to flatten and stretch the caruncle/semilunar fold toward the limbus. A thorough removal of such fibrovascular tissue was first advocated by Barraquer in 1980 [127], regarded as a possible variable contributing to different outcomes when conjunctival autografts are used by different surgeons [108], mentioned as an important step when conjunctival autograft or AM graft was used [128], and recently shown to be essential to achieve a high success in conjunctiva autograft, named Pterygium Extended Removal Followed by Extended Conjunctival Transplantation (PERFECT) [129]. Following the removal of the pterygium head and body, we have discovered that an anatomic gap between the Tenon and the conjunctiva is invariably created in primary pterygium. We speculate that the variability of sealing such a gap may help explain the difference of recurrence rates achieved by different surgical approaches with or without adjunctive measures. Our unpublished observation noted that such a gap remains open in all recurrent pterygium. Therefore, future studies are needed to confirm whether sealing of the gap will not only reduce pterygium recurrence but also help restore the normal anatomy of the caruncle from a flattened morphology to an elevated dome shape. When the gap is successfully sealed by sutures (8-O vicryl for primary and 9-O nylon for recurrent), AMT may achieve a superior outcome for primary pterygium.

Symblepharon & fornix reconstruction

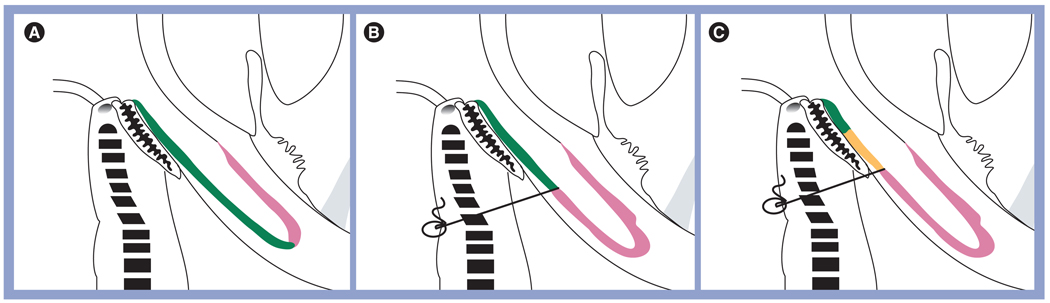

Symblepharon can be caused by any conjunctival infection (bacterial or viral conjunctivitis) or allergic conjunctivitis (vernal or atopic conjunctivitis) with secondary scarring. In addition, it can be a complication of a disease state, such as in dry eye syndrome, cicatricial pemphigoid, SJS, erythema multiforme or TEN, or secondary to chemical burn. It can also be seen in severe cases of recurrent pterygium. Various materials have been evaluated as a mechanical barrier to keep potentially adhesive surfaces apart after excision of the symblepharon, including conjunctival autograft [130], mucous membrane grafts [131] and AM [119,132–135]. The aforementioned procedures may also be combined by an additional measure to prevent readhesion, such as insertion of a conformer, symblepharon ring [136] or silicone sheet implant [137,138], or by postoperative application of β-irradiation [139] or MMC [134,135,140]. Furthermore, it has been shown that anchoring sutures to secure the released conjunctiva deep into the fornix may be useful for fornix reconstruction [119]. Recently, Kheirkhah et al. proposed a new surgical strategy for conjunctival surface reconstruction after symblepharon lysis by selectively using AMT, MMC, anchoring sutures and oral mucosal graft according to the severity of symblepharon [141]. For mild cases, the recessed conjunctiva is large enough to cover the entire palpebral area, where it is secured using fibrin glue. The bare sclera is covered with AM, with the stromal side facing down, using fibrin glue or sutures (Figure 5A). For moderate cases, the recessed conjunctiva is just large enough to cover the tarsal area. A double-armed 4-O black silk suture, secured to the skin with a bolster, is required to keep it in place. One such anchoring suture is needed per quadrant. The remaining bare sclera, fornix and palpebral area are covered by AM using fibrin glue (Figure 5B). For severe cases, there is not enough of the recessed conjunctiva to cover the tarsal area. Therefore, oral mucosal graft (OMG) is used to substitute the tarsal conjunctiva. OMG is secured to the tarsal plate with fibrin glue, sutured to the posterior lid margin using 8-O vicryl sutures, and then anchored to the skin with a bolster as previously described. The remaining bare sclera, fornix and palpebral area are covered with AM in the same manner (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. The three surgical strategies for fornix reconstruction.

(A) After symblepharon lysis and removal of subconjunctival scar tissue, amniotic membrane (pink) is used to cover the denuded scleral surface with fibrin glue or sutures up to the recessed conjunctiva (green) in mild symblepharon. (B) One anchoring suture (gray) per quadrant is used to secure the recessed conjunctival edge (green) to the skin with a bolster (gray circle) in moderate symblepharon. (C) Additional oral mucosa (orange) is used to extend the epithelial covering from the (green) residual conjunctiva in severe symblepharon.

Reproduced with permission from [141].

Conjunctivochalasis

Conjunctivochalasis (CCh) is defined as a conjunctival redundancy, frequently seen in the older age group as wrinkled tissue lying along the lower lid margin and interfering with the tear meniscus (reviewed in [142]). CCh can cause a spectrum of symptoms, ranging from aggravation of dry eye at mild stages, to the disturbance of tear outflow at moderate stages, and exposure problems at severe stages. Di Pascuale et al. provided clinically useful tools that can help differentiate CCh-induced dry eye from conventional dry eye induced by aqueous tear deficiency [143]. For symptomatic patients, topical lubricants can be tried, but they are frequently unsuccessful, and surgical excision may be required. Meller et al. reported successful reconstruction of the conjunctival surface following the removal of CCh with resolution of ocular irritation [144]. Georgiadis et al. reported resolution of symptoms in 12 patients with chronic epiphora caused by CCh after the removal of excess conjunctiva followed by AMT during a mean follow-up of 8 months [145]. Recently, Kheirkhah et al. have reported the same outcome with reduced suture-related complications by performing sutureless AMT using fibrin glue for refractory CCh in 25 eyes [146]. For a mean follow-up of 10.6 months, all eyes achieved a smooth conjunctival surface with a complete or significant improvement of symptoms. Further study has shown that the loose and dissolved Tenon tissue is correlated with the development of superior CCh, which may result in an SLK-like appearance from blink-related microtrauma. Reinforcement of conjunctival adhesion onto the sclera by AM with either fibrin glue or sutures is effective in alleviating symptoms and signs in eyes with superior CCh [147].

Tumors

Amniotic membrane transplantation has been used in conjunctival surface reconstruction when different conjunctival tumors are removed to facilitate healing with less inflammation and minimal scarring. Tseng et al. first reported successful reconstruction in 11 out of 17 eyes (65%) during removal of melanoma (n = 1), melanosis (n = 1), conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (n = 3), conjunctival scarring without symblepharon (n = 3), and conjunctival scarring with symblepharon (n = 8) in a follow-up period of 10.9 ± 9.1 months [120]. The defect covered by AM healed in 3 weeks. In three patients, impression cytology confirmed the restoration of a normal conjunctival epithelial phenotype with goblet cells [148]. Paridaens et al. reported successful reconstruction of the conjunctival surface in three out of four eyes (75%) following the removal of malignant melanoma and primary acquired melanosis with atypia using AM transplantation [149]. Chen et al. referred AM transplantation as a very effective method to repair wounds after conjunctival tumor removal in 26 patients (26 eyes), including nine eyes with malignant tumors (conjunctival melanoma, corneal and conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma, and conjunctival lymphoma) and 17 eyes with benign tumors (conjunctival papilloma, conjunctival nevus, and so on) [150]. Dalla et al. reported the successful reconstruction of the conjunctival surface in four out of four patients with diffuse conjunctival melanoma after a minimum follow-up period of 48 months [151].

Scleral reconstruction

Scleral ischemia, thinning and melt can occur in the event of acute severe chemical or thermal burns, and after ocular surgeries such as bare sclera pterygium excision, especially if adjuvant therapies such as β-irradiation and MMC are used. In addition, scleral melt has been described after retinal detachment repair, glaucoma surgery and cataract surgery, and it can also affect patients with connective tissue disorders or idiopathic systemic vasculitis. Rodriquez-Ares et al. reported a single case of successful reconstruction of the conjunctival surface and sclera in a patient with Marfan’s syndrome with extensive scleral defect [152]. However, it is difficult for AMT to promote re-epithliazation on ischemic sclera; therefore, a combined tenonplasty is needed to bring back the vasculature. Casas et al. described the combined use of AMT with tenonplasty and lamellar corneal patch graft in managing scleral ischemia and/or melt using sutures or fibrin glue in five eyes of four patients [153]. These surgical measures were effective in resolving photophobia, halting scleral ischemia and/or melt, facilitating epithelialization, and preserving the globe integrity in all eyes except for one eye, in which a second attempt was needed to completely correct scleral ischemia.

Glaucoma applications

Several investigators have explored the clinical efficacy of deploying AMT as an adjunctive therapy to improve the surgical outcome of various glaucoma procedures by reducing their complications [154].

Trabeculectomy

Amniotic membrane transplantation has been used during trabeculectomy with or without MMC in both experimental and clinical studies with promising results. When AM is used as a single [155–159] or folded [160,161] sheet under the scleral flap [155,157–159] and/or under the conjunctiva [158–161] with [155,159,160] or without [156,157,160,161] additional application of MMC, IOPs can be reduced in human eyes with refractory glaucoma that are associated with variable high-risk factors. For example, in a randomized controlled clinical trial of 48 eyes, Zheng et al. reported that the success rate was similar in trabeculectomy with either AM or MMC [162]. Recently, in a randomized controlled clinical trial including 37 eyes, Sheha et al. added AM to trabeculectomy with MMC and achieved a significantly higher complete success (IOP ≤21 mmHg without medications) and qualified success (IOP ≤21 mmHg with or without additional medications) 6 and 12 months postoperatively, respectively [159]. Furthermore, over a period of 1-year follow-up, a better control of IOP and bleb morphology (i.e., diffuse and translucent bleb with normal vascularity) was also achieved with AMT. These beneficial effects may be attributed to the fact that AM inserted under the scleral flap effectively halted rapid drainage of aqueous humor from the trabeculectomy site to reduce immediate hypotony from overfiltration, and reduced scarring in the filtration site in the long term. Experimental rabbit data showed that AM reduced the number of subconjunctival fibroblasts at trabeculectomy sites even without MMC [163,164]. Moreover, numbers of both fibroblasts and macrophages around trabeculectomy sites in rabbits are significantly reduced by either MMC or AM [165], and such suppression of fibroblasts is comparable between AMT and MMC in rabbit eyes [166]. Collectively, these encouraging results warrant further investigation of AM’s possible utility to replace MMC in trabeculectomy.

Bleb leak

Bleb leak is one of the increasing complications following trabeculectomy with the adjunctive use of antimetabolites, and may lead to sight-threatening complications. Several authors have reported 83–96% of success rates in surgical revision with either conjunctival advancement or a free autologous conjunctival graft for repairing late-onset bleb leak. Although these types of surgical intervention can resolve bleb leak, they share the risk of loss of bleb function. An ideal procedure to repair bleb leak, therefore, is one that can both support the fragile conjunctival tissue and suppress exaggerated bleb scarring. In this regard, AMT has exhibited promising results in repairing bleb leak while maintaining the filtration function as single [167–171] or double [172] layers with the epithelial side up [169,171] or down [168,171], or over [168,169] or under [171] the conjunctiva with [167,171,172] or without [168,169,171] bleb excision.

As late bleb leaks often occur in avascular, thin-walled blebs after antimetabolite use, failure of AMT to heal bleb leaks after bleb excision is likely related to the devitalized and ischemic nature of the conjunctiva [167,170,173]. Such a complication has not been noted when AM has been used to reconstruct large conjunctival defects after the removal of pterygia and symblepharon [4,174,175]. If the bordering conjunctiva is not ischemic and has a normal epithelium and subconjunctival stroma, successful closure can be achieved by AM [176]. Other authors have reported the successful repair of late bleb leaks using AM without bleb excision. They apply a single layer of AM, epithelial side down, underneath the conjunctiva through a limbal-based flap while the pre-existing scleral flap is revised [171]. The AMT-assisted bleb revision not only halts bleb leak, but also maintains functioning blebs extending posteriorly beyond the conjunctival incision without bleb leak occuring. However, if there is severe ischemia, which may ultimately limit the success of any surgical attempt, AMT in conjunction with tenonplasty (as used in scleral melt) may be considered to augment the success rate.

Prevention of tube exposure with glaucoma drainage devices

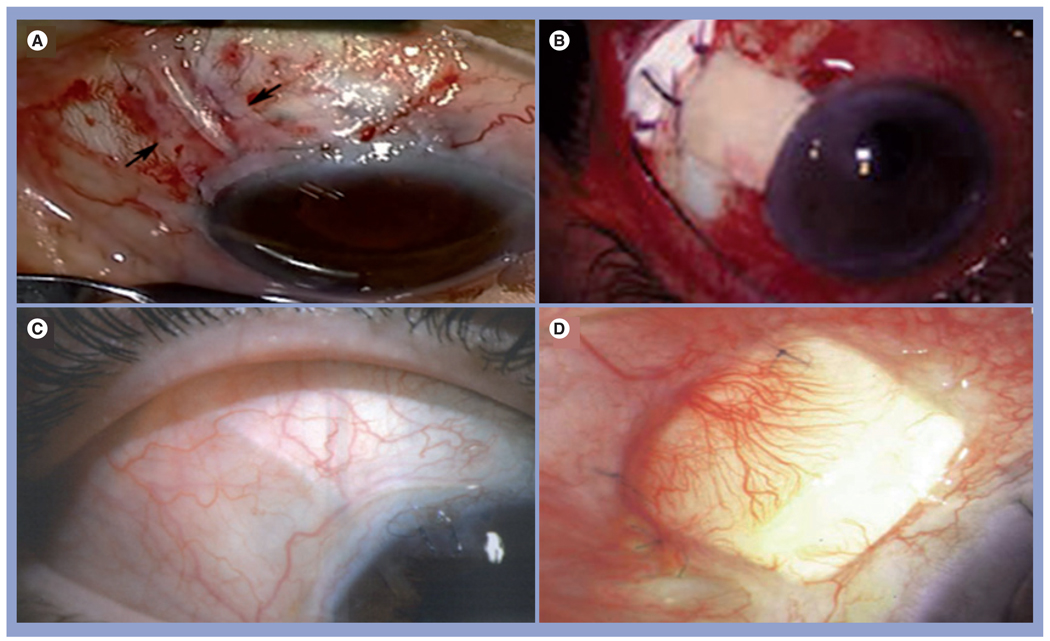

Glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs) are commonly used in the surgical management of glaucoma. If left uncovered, the extraocular portion of the tube may erode through the conjunctiva, conferring a risk of intraocular infection. Several patch grafts have been used for covering the glaucoma shunt tubes, including human sclera, pericardium, dura mater, fascia lata and cornea. The incidence of significant thinning and/or melting of graft materials can range from 15 to 25% within 2 years postoperatively. AM has been used as a conjunctival replacement, double [177] or single [178] layer, in conjunction with or without [179] a scleral patch to cover the exposed tube in cases with tube erosion. All these cases retained good short- and long-term results without re-exposure during a follow-up ranging from 6 months to 2.5 years. To circumvent the limitation of scleral or pericardial patch, a thicker cryopreserved AM with an average thickness of 300 µm or more has been produced (AmnioGuard®, Bio-Tissue, Inc., FL, USA). Preliminary results are promising in reducing tube exposure and supporting the hypothesis that AM patch can promote host cell infiltration into it to form a Tenon-like layer over the shunt tube [Anand et al. 2010, Manuscript Submitted]. Another advantage of using a thicker version of AM for covering the GDD tube is to achieve a better profile so as to avoid dellen formation. Furthermore, such an approach also produces a better esthetic appearance and allows laser suture lysis (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Representative intraoperative (A & B) and postoperative (C & D) photographs of amniotic membrane (A & C) and pericardium (B & D) covering the glaucoma drainage shunt tube.

Muscle indications

Scar tissue formation between extraocular muscles, conjunctiva, Tenon’s capsule and sclera is commonly found in strabismus reoperation cases despite properly performed strabismus surgery. Such adhesions may prevent the normal function of an extraocular muscle and render strabismus surgery ineffective. Various materials and pharmaceutical agents have been employed in an attempt to decrease the occurrence of postoperative adhesion and scar formation. However, none of them has been popularly accepted due to associated complications, unavailability or inconsistent results.

Amniotic membrane has been used successfully in four patients to repair severe conjunctival dehiscence after strabismus surgery [180]. Conjunctival re-epithelialization was complete by the fourth week, without evidence of scarring or motility restriction. Yamada et al. used AM in a patient with fat-adhesion syndrome after retinal surgery [181]. After removing the subconjunctival fibrosis, they recessed the extraocular muscle and put a piece of AM on the exposed sclera and the muscle. Eye movement improved after surgery and remained stable for more than 1 year of follow-up. Recently, Sheha et al. wrapped the muscle with AM to reduce the adhesion formation in a patient with consecutive exotropia without recurrence in a follow-up of more than 1 year [182].

Complications & limitations

There have not been any reports thus far demonstrating microbial infections directly linked with AMT. Marangon et al. reported the incidence and characteristics of post-AMT infection in 326 patients undergoing AMT from January 1994 to February 2001 at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (FL, USA) [183]. They subdivided these patients into two groups related to the submission or not of the AMT storage media for culture under an institutional review board-approval protocol. A total of 11 culture-positive infections (3.4%) were identified. Seven (9.2%) were from the first group and four (1.6%) were from the second group. All infections occurring within 1 month after AMT (n = 4) were exclusively from the first group. All AM storage media from the second group were culture negative. Gram-positive organisms were the most frequently isolated (64%). Finally, they concluded that AMT is a safe method for ocular surface reconstruction with a very low rate of microbial infections, especially if AM is prepared according to the Good Tissue Banking Practice set forth by the FDA.

Kim et al. reported complications such as submembrane hemorrhage (three out of 25 eyes; 12%) and early detachment of the membrane (one out of 25 eyes; 4%) [184]. The former is obviously related to the surgery and not AM. Gabler and Lohmann reported a case that developed sterile hypopyon (inflammation inside the anterior chamber) following repeated transplantation of AM [185]. They attributed this complication to an immunologic, toxic or hypersensitive effect of the membrane. No similar complication has been reported by others. Gomes et al. observed a granulomatous reaction unrelated to sutures a few days after ocular surface reconstruction combined with a living related conjunctival limbal allograft in a SJS patient [4].

Obviously, AMT is not a surgery that will work in every ocular surface disease. When performed for the same indication, the success of AMT can be limited by other factors that definitely affect the host wound healing response. For the ocular surface, the degree of desiccation and exposure is an important limiting factor to any surgery, including AMT. Because AM does not contain viable cells, reconstruction depends on the healthy status of the surrounding host tissues. Hence, several limiting factors have been recognized, and they include inflammation that has passed the acute stage and has become relentless, and ischemia where no viable cells can reside to flourish. Furthermore, if the host cells are intrinsically abnormal, for example during the loss of epithelial stem cells in the setting of LSCD or squmamous metaplasia, AMT alone cannot achieve successful reconstruction without also transplanting healthy epithelial or mesenchymal progenitors. Besides variation in donors and preparation methods that may affect AM quality and therapeutic action, non-uniformity in patient selection, disease severity, previous and concomitant treatments, and manner of AMT can further complicate data analyses. The impact of such studies is dampened because these studies rely on a retrospective review of the records using the outcome measure that was subjective and retrofit.

Expert commentary

Our literature review reveals that there has been a clear surge of increasing popularity of using AMT as a new surgical strategy for ocular surface reconstruction. Continuous advances in the surgical technique of AMT are multiple. Specifically, there is a growing interest in performing AMT in a sutureless manner, not only to increase surgical efficiency but also to improve the surgical outcome. Furthermore, cumulative clinical knowledge and experience has also propelled AMT into indications beyond ocular surface reconstruction. In view of the limitations of AMT, other adjunctive measures have also been recognized to foster ocular surface defense (e.g., via restoration of a stable tear film), to control host inflammation (via combined systemic immunosuppression and intraoperative application of MMC), to rectify ischemia (via tenonplasty) and to incorporate healthy host cells to the surrounding tissue (via transplantation of autologous and allogeneic epithelial stem cells). Recent basic research in exploring the molecular mechanism whereby AMT exerts its therapeutic actions has generated exciting findings and revelations. Specifically, the discovery of a single component (i.e., HC•HA) for suppressing inflammation, scarring and angiogenesis, is surprising, and indicates that a unique fetal strategy might have been built in AM to curtail innate immunity and gear up the wound-healing process toward regeneration.

Five-year view

Based on the aforementioned analyses of the published literature, it is clear that continuous improvement in the surgical technique of AM is likely in the future. Such improvements can be derived from the way AM is prepared in terms of thickness, tensile strength and potency. Furthermore, the outcome of AMT can also be improved when additional new measures are taken to enhance the host tissue microenvironment. Thus, AM can not only be used in many tissue sites of the eye, but can also be extended to treat similar diseases beyond ophthalmology. The greatest potential of AM that remains to be harnessed lies in the continuous exploration of the molecular mechanism explaining AM’s biological actions. Furthermore, further characterization of AM’s components, the cells involved in producing such components, and the modulation of such cells in AM will unravel additional novel therapeutics that can significantly and fundamentally change the strategy to direct adult wound healing toward regeneration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by research grants (EY06819, EY14768, EY015735 and EY 017497 to Scheffer CG Tseng, and EY 019785 to Hosam Sheha) from the National Eye Institute, NIH (Bethesda, MD, USA), and grant no. 30801262 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Tseng SCG, Espana EM, Kawakita T, et al. How does amniotic membrane work? Ocul. Surf. 2004;2(3):177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sippel KC, Ma JJK, Foster CS. Amniotic membrane surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2001;12:269–281. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction. Bioscience Rep. 2002;21:481–489. doi: 10.1023/a:1017995810755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dua HS, Gomes JA, King AJ, Maharajan VS. The amniotic membrane in ophthalmology. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2004;49(1):51–77. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchard CS, John T. Amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of severe ocular surface disease: indications and outcomes. Ocul. Surf. 2004;2(3):201–211. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mast BA, Diegelmann RF, Krummel TM, Cohen IK. Scarless wound healing in mammalian fetus. Surgery. 1992;174:441–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adzick NS, Lorenz HP. Cells, matrix, growth factors, and the surgeon. The biology of scarless fetal wound repair. Ann. Surg. 1994;220:10–18. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199407000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JS, Kim JC, Na BK, Jeong JM, Song CY. Amniotic membrane patching promotes healing and inhibits proteinase activity on wound healing following acute corneal alkali burn. Exp. Eye Res. 2000;70(3):329–337. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, Ohashi Y, Tsubota K. Antiinflammatory effects of amniotic membrane transplantation in ocular surface disorders. Cornea. 2001;20(4):408–413. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200105000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kheirkhah A, Johnson DA, Paranjpe DR, Raju VK, Casas V, Tseng SC. Temporary sutureless amniotic membrane patch for acute alkaline burns. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008;126(8):1059–1066. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.8.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park WC, Tseng SC. Modulation of acute inflammation and keratocyte death by suturing, blood, and amniotic membrane in PRK. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41(10):2906–2914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiligenhaus A, Meller D, Meller D, Steuhl K-P, Tseng SCG. Improvement of HSV-1 necrotizing keratitis with amniotic membrane transplantation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42:1969–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heiligenhaus A, Li H, Hernandez Galindo EE, Koch JM, Steuhl KP, Meller D. Management of acute ulcerative and necrotising herpes simplex and zoster keratitis with amniotic membrane transplantation. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;87(10):1215–1219. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.10.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer D, Wasmuth S, Hermans P, et al. On the influence of neutrophils in corneas with necrotizing HSV-1 keratitis following amniotic membrane transplantation. Exp. Eye Res. 2007;85(3):335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer D, Wasmuth S, Hennig M, Baehler H, Steuhl KP, Heiligenhaus A. Amniotic membrane transplantation induces apoptosis in T lymphocytes in murine corneas with experimental herpetic stromal keratitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009;50(7):3188–3198. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W, He H, Kawakita T, Espana EM, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane induces apoptosis of interferon-g activited macrophages in vitro. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;82(2):282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He H, Li W, Chen SY, et al. Suppression of activation and induction of apoptosis in RAW264.7 cells by amniotic membrane extract. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49(10):4468–4475. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He H, Li W, Tseng DY, et al. Biochemical characterization and function of complexes formed by hyaluronan and the heavy chains of inter-α-inhibitor (HC•HA) purified from extracts of human amniotic membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(30):20136–20146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tseng SCG, Li D-Q, Ma X. Suppression of transforming growth factor isoforms, TGF-β receptor II, and myofibroblast differentiation in cultured human corneal and limbal fibroblasts by amniotic membrane matrix. J. Cell. Physiol. 1999;179:325–335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199906)179:3<325::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S-B, Li D-Q, Tan DTH, Meller D, Tseng SCG. Suppression of TGF-β signaling in both normal conjunctival fibroblasts and pterygial body fibroblasts by amniotic membrane. Curr. Eye Res. 2000;20:325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi TH, Tseng SCG. In vivo and in vitro demonstration of epithelial cell-induced myofibroblast differentiation of keratocytes and an inhibitory effect by amniotic membrane. Cornea. 2001;20:197–204. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200103000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espana EM, He H, Kawakita T, et al. Human keratocytes cultured on amniotic membrane stroma preserve morphology and express keratocan. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44(12):5136–5141. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espana EM, Kawakita T, Liu CY, Tseng SCG. CD-34 expression by cultured human keratocytes is downregulated during myofibroblast differentiation induced by TGF-β1. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(9):2985–2991. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakita T, Espana EM, He H, et al. Keratocan expression of murine keratocytes is maintained on amniotic membrane by downregulating TGF-β signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27085–27092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409567200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawakita T, Espana EM, He H, et al. Preservation and expansion of the primate keratocyte phenotype by downregulating TGF-β signaling in a low-calcium, serum-free medium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47(5):1918–1927. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JC, Tseng SCG. The effects on inhibition of corneal neovascularization after human amniotic membrane transplantation in severely damaged rabbit corneas. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 1995;9:32–46. doi: 10.3341/kjo.1995.9.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang A, Li C, Gao Y, et al. In vivo and in vitro inhibitory effect of amniotic extraction on neovascularization. Cornea. 2006;25(10 Suppl. 1):S36–S40. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000247211.78391.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kucukerdonmez C, Akova YA, Altinors DD. Vascularization is more delayed in amniotic membrane graft than conjunctival autograft after pterygium excision. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007;143(2):245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng SCG, Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Gray T, Meller D. Amniotic membrane transplantation with or without limbal allografts for corneal surface reconstruction in patients with limbal stem cell deficiency. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1998;116:431–441. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsubota K, Satake Y, Kaido M, et al. Treatment of severe ocular surface disorders with corneal epithelial stem-cell transplantation. N. Eng. J. Med. 1999;340:1697–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai RJF, Li L-M, Chen J-K. Reconstruction of damaged corneas by transplantation of autologous limbal epithelial cells. N. Eng. J. Med. 2000;343:86–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi N, Kabuyama Y, Sasaki S, Kato K, Homma Y. Suppression of corneal neovascularization by culture supernatant of human amniotic cells. Cornea. 2002;21(1):62–67. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stellmach V, Crawford SE, Zhou W, Bouck N. Prevention of ischemia-induced retinopathy by the natural ocular antiangiogenic agent pigment epithelium-derived factor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(5):2593–2597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031252398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao C, Sima J, Zhang SX, et al. Suppression of corneal neovascularization by PEDF release from human amniotic membranes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(6):1758–1762. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hao Y, Ma DH-K, Hwang DG, Kim WS, Zhang F. Identification of antiangiogenic and antiinflammatory proteins in human amniotic membrane. Cornea. 2000;19:348–352. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma DH, Yao JY, Yeh LK, et al. In vitro antiangiogenic activity in ex vivo expanded human limbocorneal epithelial cells cultivated on human amniotic membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(8):2586–2595. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheha H, Liang L, Li J, Tseng SC. Sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation for severe bacterial keratitis. Cornea. 2009;28(10):1118–1123. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181a2abad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.John T, Foulks GN, John ME, Cheng K, Hu D. Amniotic membrane in the surgical management of acute toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(2):351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi A, Yoshita T, Sugiyama K, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation in acute phase of toxic epidermal necrolysis with severe corneal involvement. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(1):126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonmez B, Kim BT, Aldave AJ. Amniotic membrane transplantation with anterior stromal micropuncture for treatment of painful bullous keratopathy in eyes with poor visual potential. Cornea. 2007;26(2):227–229. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000244876.92879.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finger PT. Finger’s amniotic membrane buffer technique: protecting the cornea during radiation plaque therapy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008;126(4):531–534. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ono K, Yokoo S, Mimura T, et al. Autologous transplantation of conjunctival epithelial cells cultured on amniotic membrane in a rabbit model. Mol. Vis. 2007;13:1138–1143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanioka H, Kawasaki S, Yamasaki K, et al. Establishment of a cultivated human conjunctival epithelium as an alternative tissue source for autologous corneal epithelial transplantation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47(9):3820–3827. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ang LP, Tan DT. Autologous cultivated conjunctival transplantation for recurrent viral papillomata. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2005;140(1):136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sangwan VS, Vemuganti GK, Singh S, Balasubramanian D. Successful reconstruction of damaged ocular outer surface in humans using limbal and conjuctival stem cell culture methods. Biosci. Rep. 2003;23(4):169–174. doi: 10.1023/b:bire.0000007690.43273.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meller D, Dabul V, Tseng SC. Expansion of conjunctival epithelial progenitor cells on amniotic membrane. Exp. Eye Res. 2002;74(4):537–545. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zakaria N, Koppen C, Van Tendeloo V, Berneman Z, Hopkinson A, Tassignon MJ. Standardized limbal epithelial stem cell graft generation and transplantation. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods. 2010 doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0634. DOI: 10.1089/ten. tec.2009.0634 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lekhanont K, Choubtum L, Chuck RS, Sa-ngiampornpanit T, Chuckpaiwong V, Vongthongsri A. A serum- and feeder-free technique of culturing human corneal epithelial stem cells on amniotic membrane. Mol. Vis. 2009;15:1294–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinoshita S, Nakamura T. Development of cultivated mucosal epithelial sheet transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction. Artif. Organs. 2004;28(1):22–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2004.07319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koizumi N, Fullwood NJ, Bairaktaris G, Inatomi T, Kinoshita S, Quantock AJ. Cultivation of corneal epithelial cells on intact and denuded human amniotic membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41(9):2506–2513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baharvand H, Ebrahimi M, Javadi MA. Comparison of characteristics of cultured limbal cells on denuded amniotic membrane and fresh conjunctival, limbal and corneal tissues. Dev. Growth Differ. 2007;49(3):241–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sudha B, Sitalakshmi G, Iyer GK, Krishnakumar S. Putative stem cell markers in limbal epithelial cells cultured on intact & denuded human amniotic membrane. Indian J. Med. Res. 2008;128(2):149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwab IR, Reyes M, Isseroff RR. Successful transplantation of bioengineered tissue replacements in patients with ocular surface disease. Cornea. 2000;19:421–426. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koizumi N, Cooper LJ, Fullwood NJ, et al. An evaluation of cultivated corneal limbal epithelial cells, using cell-suspension culture. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43(7):2114–2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meller D, Pires RTF, Tseng SCG. Ex vivo preservation and expansion of human limbal epithelial stem cells on amniotic membrane cultures. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002;86:463–471. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grueterich M, Tseng SCG. Human limbal progenitor cells expanded on intact amniotic membrane. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2002;120:783–790. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grueterich M, Espana E, Tseng SC. Connexin 43 expression and proliferation of human limbal epithelium on intact and denuded amniotic membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43(1):63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ban Y, Cooper LJ, Fullwood NJ, et al. Comparison of ultrastructure, tight junction-related protein expression and barrier function of human corneal epithelial cells cultivated on amniotic membrane with and without air-lifting. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;76(6):735–743. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramaesh K, Dhillon B. Ex vivo expansion of corneal limbal epithelial/stem cells for corneal surface reconstruction. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;13(6):515–524. doi: 10.1177/112067210301300602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Madhira SL, Vemuganti G, Bhaduri A, Gaddipati S, Sangwan VS, Ghanekar Y. Culture and characterization of oral mucosal epithelial cells on human amniotic membrane for ocular surface reconstruction. Mol. Vis. 2008;14:189–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakamura T, Endo K, Cooper LJ, et al. The successful culture and autologous transplantation of rabbit oral mucosal epithelial cells on amniotic membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44(1):106–116. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, Amemiya T, Kanamura N, Kinoshita S. Transplantation of cultivated autologous oral mucosal epithelial cells in patients with severe ocular surface disorders. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2004;88(10):1280–1284. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.038497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wencan W, Mao Y, Wentao Y, et al. Using basement membrane of human amniotic membrane as a cell carrier for cultivated cat corneal endothelial cell transplantation. Curr. Eye Res. 2007;32(3):199–215. doi: 10.1080/02713680601174165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ishino Y, Sano Y, Nakamura T, et al. Amniotic membrane as a carrier for cultivated human corneal endothelial cell transplantation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45(3):800–806. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen YT, Li W, Hayashida Y, et al. Human amniotic epithelial cells as novel feeder layers for promoting ex vivo expansion of limbal epithelial progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8):1995–2005. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koizumi N, Inatomi T, Quantock AJ, Fullwood NJ, Dota A, Kinoshita S. Amniotic membrane as a substrate for cultivating limbal corneal epithelial cells for autologous transplantation in rabbits. Cornea. 2000;19:65–71. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakamura T, Kinoshita S. Ocular surface reconstruction using cultivated mucosal epithelial stem cells. Cornea. 2003;22(7 Suppl.):S75–S80. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song E, Yang W, Cui ZH, et al. Transplantation of human limbal cells cultivated on amniotic membrane for reconstruction of rat corneal epithelium after alkaline burn. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2005;118(11):927–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Espana EM, Ti SE, Grueterich M, Touhami A, Tseng SC. Corneal stromal changes following reconstruction by ex vivo expanded limbal epithelial cells in rabbits with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;87(12):1509–1514. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.12.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakamura T, Koizumi N, Tsuzuki M, et al. Successful regrafting of cultivated corneal epithelium using amniotic membrane as a carrier in severe ocular surface disease. Cornea. 2003;22(1):70–71. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200301000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tan DT, Ang LP, Beuerman RW. Reconstruction of the ocular surface by transplantation of a serum-free derived cultivated conjunctival epithelial equivalent. Transplantation. 2004;77(11):1729–1734. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000127593.65888.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, Koizumi N, Kinoshita S. Successful primary culture and autologous transplantation of corneal limbal epithelial cells from minimal biopsy for unilateral severe ocular surface disease. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2004;82(4):468–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1395-3907.2004.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee S-H, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent epithelial defects with ulceration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1997;123:303–312. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Solomon A, Touhami A, Sandoval H, Tseng SCG. Neurotrophic keratopathy: basic concepts and therapeutic strategies. Comp. Ophthalmol. Update. 2000;3:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen H-J, Pires RTF, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for severe neurotrophic corneal ulcers. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000;84:826–833. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanada K, Shimazaki J, Shimmura S, Tsubota K. Multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation for severe ulceration of the cornea and sclera. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001;131(3):324–331. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Solomon A, Meller D, Prabhasawat P, et al. Amniotic membrane grafts for nontraumatic corneal perforations, descemetoceles, and deep ulcers. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(4):694–703. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)01032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Letko E, Stechschulte SU, Kenyon KR, et al. Amniotic membrane inlay and overlay grafting for corneal epithelial defects and stromal ulcers. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001;119:659–663. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodriguez-Ares MT, Tourino R, Lopez-Valladares MJ, Gude F. Multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation in the treatment of corneal perforations. Cornea. 2004;23(6):577–583. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000121709.58571.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hick S, Demers PE, Brunette I, La C, Mabon M, Duchesne B. Amniotic membrane transplantation and fibrin glue in the management of corneal ulcers and perforations: a review of 33 cases. Cornea. 2005;24(4):369–377. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000151547.08113.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seitz B, Das S, Sauer R, Mena D, Hofmann-Rummelt C. Amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent corneal epithelial defects in eyes after penetrating keratoplasty. Eye. 2009;23(4):840–848. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nubile M, Dua HS, Lanzini TE, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for the management of corneal epithelial defects: an in vivo confocal microscopic study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008;92(1):54–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.123026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Prabhasawat P, Tesavibul N, Komolsuradej W. Single and multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent corneal epithelial defect with and without stromal thinning and perforation. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2001;85(12):1455–1463. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.12.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duchesne B, Tahi H, Galand A. Use of human fibrin glue and amniotic membrane transplant in corneal perforation. Cornea. 2001;20(2):230–232. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200103000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim HK, Park HS. Fibrin glue-assisted augmented amniotic membrane transplantation for the treatment of large noninfectious corneal perforations. Cornea. 2009;28(2):170–176. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181861c54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim JS, Kim JC, Hahn TW, Park WC. Amniotic membrane transplantation in infectious corneal ulcer. Cornea. 2001;20(7):720–726. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gicquel JJ, Bejjani RA, Ellies P, Mercie M, Dighiero P. Amniotic membrane transplantation in severe bacterial keratitis. Cornea. 2007;26(1):27–33. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31802b28df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mencucci R, Menchini U, Dei R. Antimicrobial activity of antibiotic-treated amniotic membrane: an in vitro study. Cornea. 2006;25(4):428–431. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214207.06952.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pires RTF, Tseng SCG, Prabhasawat P, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for symptomatic bullous keratopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1291–1297. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.10.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mrukwa-Kominek E, Gierek-Ciaciura S, Rokita-Wala I, Szymkowiak M. Use of amniotic membrane transplantation for treating bullous keratopathy. Klin. Oczna. 2002;104(1):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mejia LF, Santamaria JP, Acosta C. Symptomatic management of postoperative bullous keratopathy with nonpreserved human amniotic membrane. Cornea. 2002;21(4):342–345. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Espana EM, Grueterich M, Sandoval H, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for bullous keratopathy in eyes with poor visual potential. J. Cat. Refract. Surg. 2003;29:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chansanti O, Horatanaruang O. The results of amniotic membrane transplantation for symptomatic bullous keratopathy. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2005;88 Suppl. 9:S57–S62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]