Abstract

Lobeline attenuates the behavioral effects of methamphetamine via inhibition of the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2). To increase selectivity for VMAT2, chemically defunctionalized lobeline analogs, including lobelane, were designed to eliminate nicotinic acetylcholine receptor affinity. The current study evaluated the ability of lobelane analogs to inhibit [3H]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) binding to VMAT2 and [3H]dopamine (DA) uptake into isolated synaptic vesicles and determined the mechanism of inhibition. Introduction of aromatic substituents in lobelane maintained analog affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site on VMAT2 and inhibitory potency in the [3H]DA uptake assay assessing VMAT2 function. The most potent (Ki = 13–16 nM) analogs in the series included para-methoxyphenyl nor-lobelane (GZ-252B), para-methoxyphenyl lobelane (GZ-252C), and 2,4-dichlorphenyl lobelane (GZ-260C). Affinity of the analogs for the [3H]DTBZ binding site did not correlate with inhibitory potency in the [3H]DA uptake assay. It is noteworthy that the N-benzylindole-, biphenyl-, and indole-bearing meso-analogs 2,6-bis[2-(1-benzyl-1H-indole-3-yl)ethyl]-1-methylpiperidine hemifumarate (AV-1-292C), 2,6-bis(2-(biphenyl-4-yl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride (GZ-272B), and 2,6-bis[2-(1H-indole-3-yl)ethyl]-1-methylpiperidine monofumarate (AV-1-294), respectively] inhibited VMAT2 function (Ki = 73, 127, and 2130 nM, respectively), yet had little to no affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site. These results suggest that the analogs interact at an alternate site to DTBZ on VMAT2. Kinetic analyses of [3H]DA uptake revealed a competitive mechanism for 2,6-bis(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride (GZ-252B), 2,6-bis(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride (GZ-252C), 2,6-bis(2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride (GZ-260C), and GZ-272B. Similar to methamphetamine, these analogs released [3H]DA from the vesicles, but with higher potency. In contrast to methamphetamine, these analogs had higher potency (>100-fold) at VMAT2 than DAT, predicting low abuse liability. Thus, modification of the lobelane molecule affords potent, selective inhibitors of VMAT2 function and reveals two distinct pharmacological targets on VMAT2.

Introduction

Methamphetamine abuse continues to escalate on a national level (Drug and Alcohol Services Information System Report; http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k8/methamphetamineTx/meth.htm). Currently, no efficacious pharmacotherapies are available to treat methamphetamine addiction. Neurochemical mechanisms underlying the rewarding properties of methamphetamine include activation of the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway (Wise and Hoffman, 1992; Di Chiara et al., 2004). Methamphetamine is a substrate at presynaptic dopamine transporters (DATs). Within the presynaptic terminal, methamphetamine interacts with the vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2) located on synaptic vesicles, inhibiting dopamine (DA) uptake and promoting vesicular DA release, leading to increased cytosolic DA concentrations (Sulzer and Rayport, 1990; Pifl et al., 1995; Brown et al., 2000). Methamphetamine-induced inhibition of the mitochondrial enzyme monoamine oxidase further elevates cytosolic DA concentrations (Mantle et al., 1976). Through reverse transport of DAT, methamphetamine releases cytosolic DA into the extracellular space, resulting in postsynaptic DA receptor stimulation (Liang and Rutledge, 1982; Sulzer et al., 1995; Takahashi et al., 1997; Patel et al., 2003). Thus, the interaction of methamphetamine with multiple presynaptic protein targets, including VMAT2, contributes to increased extracellular DA concentrations and ultimately methamphetamine-induced reward.

Lobeline, a major lipophilic, alkaloidal constituent of Lobelia inflata, is currently in development as a treatment for methamphetamine abuse, and a phase 1B clinical trial, which demonstrated its safety after oral administration to individuals addicted to methamphetamine, has been completed. In preclinical studies, lobeline was shown to attenuate the hyperactivity and reinforcing effects of methamphetamine (Harrod et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2001). Furthermore, lobeline was not self-administered, indicating that it does not serve as a substitute reinforcer and probably has low abuse liability (Harrod et al., 2003). The lobeline-induced decrease in methamphetamine self-administration was not surmounted by increasing the unit dose of methamphetamine, suggesting that lobeline acts noncompetitively (Harrod et al., 2003).

Lobeline, however, is a relatively nonselective alkaloid, and has been classified previously as both a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) agonist (Decker et al., 1993) and antagonist (Teng et al., 1997, 1998; Briggs and McKenna, 1998; Toth and Vizi, 1998; Miller et al., 2000; Lim et al., 2004). In addition, lobeline inhibits [3H]DA uptake at DAT and more potently inhibits [3H]DA uptake and [3H]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) binding at VMAT2. Lobeline also reduces methamphetamine-evoked DA release in vitro (Miller et al., 2001; Wilhelm et al., 2008). Collectively, the neurochemical mechanisms underlying the behavioral effects of lobeline are hypothesized to be through an interaction with nAChRs and/or VMAT2 (Dwoskin and Crooks, 2002).

Several prior structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies have focused on altering the chemical structure of lobeline with the aim of improving both the affinity and selectivity for VMAT2 (Zheng et al., 2005a,b). Structural modification of lobeline afforded lobelane, a saturated defunctionalized analog. These studies revealed that removal of the oxygen-containing functional groups of lobeline, such as with lobelane, diminished affinity for [3H]nicotine and [3H]methyllycaconitine binding sites (α4β2* and α7* nAChRs, respectively, where * indicates the putative nAChR subtype assignment) (Miller et al., 2004) and retained affinity for VMAT2 at the [3H]DTBZ binding site on VMAT2 (Zheng et al., 2005a). Furthermore, lobelane retained the ability to decrease methamphetamine self-administration (Neugebauer et al., 2007). Thus, the findings that methamphetamine interacts with VMAT2 to increase extracellular DA and ultimately methamphetamine-induced reward, the selective interaction of lobelane with VMAT2, and the observations that lobelane inhibits the effects of methamphetamine provide support for VMAT2 as a pharmacological target for the development of novel treatments for methamphetamine abuse.

Further altering the chemical structure of lobelane resulted in a series of analogs with affinity for the [3H]DTBZ site on VMAT2 (Zheng et al., 2005a,b). The ability of these lobelane analogs to inhibit VMAT2 function (i.e., DA uptake) has not been evaluated. As such, the objective of the present study was to assess the ability of this series of phenyl-substituted lobelane analogs to inhibit [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2 and elucidate the mechanism of inhibition (i.e., competitive versus noncompetitive). In addition, the most potent analogs in the series inhibiting VMAT2 function were evaluated for their ability to evoke [3H]DA release from synaptic vesicles and inhibit [3H]DA uptake at DAT as a preliminary assessment of potential for abuse liability.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g upon arrival) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). Rats were housed in the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources at the University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY) and had ad libitum access to food and water. Experimental protocols involving the animals were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky.

Chemicals.

[3H]DA (dihydroxyphenylethylamine, 3,4-[ring-2,5,6-3H]; specific activity, 28.0 Ci/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Waltham, MA). [3H]DTBZ ((±)-α-[O-methyl-3H]dihydrotetrabenazine; specific activity, 20.0 Ci/mmol) was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). EDTA, EGTA, l-(+) tartaric acid, HEPES, 3-hydroxytyramine (dopamine, DA), sucrose, magnesium sulfate, polyethyleneimine, sodium chloride, d-methamphetamine hydrochloride (methamphetamine), and ATP magnesium salt were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). l-Ascorbic acid, α-d-glucose, and sodium bicarbonate were obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). All other chemicals used in the assay buffers were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

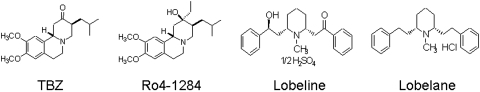

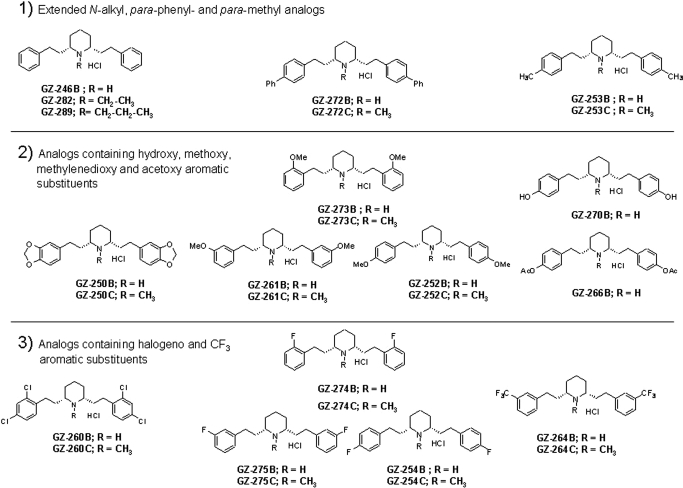

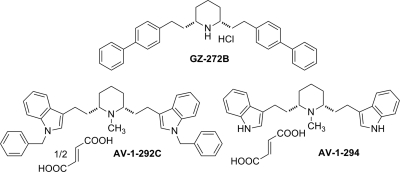

(2R,3S,11bS)-2-ethyl-3-isobutyl-9,10-dimethoxy-2,2,4,6,7,11b-hexahydro-1H-pyrido[2,1a]isoquinolin-2-ol (Ro4-1284), a benzoquinolizine compound, and tetrabenazine (TBZ), also belonging to the benzoquinolizine family, were gifts from F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd. (Basel, Switzerland). Lobeline hemisulfate was purchased from Valeant Pharmaceuticals (Costa Mesa, CA). Lobelane, a defunctionalized, saturated meso-analog of lobeline, was synthesized as described previously (Zheng et al., 2005a, b) (Fig. 1). Additional meso lobelane analogs (Fig. 2) were synthesized as described previously (Zheng et al., 2005a,b). 2,6-Bis[2-(1-benzyl-1H-indole-3-yl)ethyl]-1-methylpiperidine hemifumarate (AV-1-292C) and 2,6-bis[2-(1H-indole-3-yl)ethyl]-1-methylpiperidine monofumarate (AV-1-294) were synthesized in-house in the laboratories of the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky and are shown in Fig. 3. Chemical structures of the analogs were verified by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallography.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of standards. TBZ is a benzoquinolizine compound that depletes vesicular neurotransmitter content by reversibly inhibiting VMAT2. Ro4-1284 is also a compound belonging to the benzoquinolizine family that influences storage of catecholamines in a similar manner. Lobeline is a lipophilic, nonpyridino alkaloid present in L. inflata. Lobelane is a defunctionalized, saturated meso-analog of lobeline.

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of lobelane and derivative analogs bearing phenyl ring substituents. For clarity of presentation, compounds are grouped according to structural similarity of phenyl ring substituents: 1) compounds with an extended distance between the N-methyl and piperidine ring and analogs containing phenyl and methyl substituents; 2) compounds bearing moieties that contain oxygen; and 3) analogs bearing highly electronegative atoms/groups on the phenyl rings. GZ-246B, 2,6-bis[2-phenylethyl]piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-282, 2,6-bis(2-phenylethyl)-1-ethylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-289, 2,6-bis(2-phenylethyl)-1-n-propylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-253B, 2,6-bis(2-(4-methylphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-253C, 2,6-bis(2-(4-methylphenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-273B, 2,6-bis(2-(2-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-273C, 2,6-bis(2-(2-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-270B, 2,6-bis(2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-250B, 2,6-bis(2-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-250C, 2,6-bis(2-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-261B, 2,6-bis(2-(3-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-261C, 2,6-bis(2-(3-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-266B, 2,6-bis(2-(4-acetoxyphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-274B, 2,6-bis(2-(2-fluorophenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-274C, 2,6-bis(2-(2-fluorophenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-260B, 2,6-bis(2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-275B, 2,6-bis(2-(3-fluorophenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-275C, 2,6-bis(2-(3-fluorophenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-254B, 2,6-bis(2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-254C, 2,6-bis(2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride; GZ-264B, 2,6-bis(2-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride; GZ-264C, 2,6-bis(2-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride.

Fig. 3.

Lobelane analogs containing bulky aromatic moieties. Compounds GZ-272B, AV-1-292C, and AV-1-294, which, respectively contain bulky biphenyl, N-benzylindole, and indole moieties, are shown.

[3H]DTBZ Binding Assay.

Lobelane- and analog-induced inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding was determined using modifications of a previously described method (Teng et al., 1998). Rat whole brain (excluding cerebellum) was homogenized in 20 ml of ice-cold 0.32 M sucrose solution with seven up-and-down strokes of a Teflon pestle homogenizer (clearance ≈ 0.003 inch). Homogenates were centrifuged at 1000g for 12 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatants were centrifuged at 22,000g for 10 min at 4°C. Resulting pellets were incubated in 18 ml of ice-cold MilliQ water (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) for 5 min. Then, 2 ml of a solution of HEPES (25 mM) and 2 ml of a solution of potassium tartrate (100 mM) were added. Samples were centrifuged (20,000g for 20 min at 4°C), and 20 μl of MgSO4 (1 mM) solution was added to the supernatants. Solutions were centrifuged (100,000g for 45 min at 4°C), and pellets were resuspended in ice-cold assay buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM potassium tartrate, 5 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.05 mM EGTA, pH 7.5). Assays were performed in duplicate using 96-well plates. An aliquot of vesicular suspension (15 μg protein/100 μl) was added to each well, which contained 5 nM [3H]DTBZ, 50 μl of inhibitor (1 nM–1 mM), and 50 μl of assay buffer. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of Ro4-1284 (10 μM). In addition, lobeline, lobelane, TBZ, and Ro4-1284 were evaluated as positive controls, with well established pharmacological profiles (Zheng et al., 2005a), for comparison with the novel analogs. Reactions were terminated by filtration (Filtermate harvester; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences) onto Unifilter-96 GF/B filter plates (presoaked in 0.5% polyethyleneimine). Filters were washed subsequently five times with 350 μl of ice-cold buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM potassium tartrate, 5 mM MgSO4, and 10 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). Filter plates were dried and bottom-sealed, and each well was filled with 40 μl of scintillation cocktail (MicroScint 20; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). Radioactivity on the filters was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry (TopCount NXT; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences).

Vesicular [3H]DA Uptake Assay.

Inhibition of [3H]DA uptake was conducted using isolated synaptic vesicle preparations (Teng et al., 1997). In brief, rat striata were homogenized with 10 up-and-down strokes of a Teflon pestle homogenizer (clearance ∼ 0.003 inch) in 14 ml of 0.32 M sucrose solution. Homogenates were centrifuged (2000g for 10 min at 4°C), and then the supernatants were centrifuged (10,000g for 30 min at 4°C). Pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of 0.32 M sucrose solution and subjected to osmotic shock by adding 7 ml of ice-cold MilliQ water to the preparation. After 1 min, osmolarity was restored by adding 900 μl of 0.25 M HEPES buffer and 900 μl of 1.0 M potassium tartrate solution. Samples were centrifuged (20,000g for 20 min at 4°C), and the supernatants were centrifuged (55,000g for 1 h at 4°C), followed by addition of 100 μl of 10 mM MgSO4, 100 μl of 0.25 M HEPES, and 100 μl of 1.0 M potassium tartrate solution before the final centrifugation (100,000g for 45 min at 4°C). Final pellets were resuspended in 2.4 ml of assay buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM potassium tartrate, 50 μM EGTA, 100 μM EDTA, 1.7 mM ascorbic acid, 2 mM ATP-Mg2+, pH 7.4). Aliquots of the vesicular suspension (100 μl) were added to tubes containing assay buffer, various concentrations of inhibitor (0.1 nM–10 mM), and 0.1 μM [3H]DA in a final volume of 500 μl and incubated at 37°C for 8 min. Nonspecific uptake was determined in the presence of Ro4-1284 (10 μM). Reactions were terminated by filtration, and radioactivity retained by the filters was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry (Tri-Carb 2100TR liquid scintillation analyzer; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences).

To determine the mechanism of inhibition of [3H]DA uptake for the analogs and standards, kinetic analyses were performed on selected compounds. Lobeline, lobelane, and TBZ were selected as standard compounds. para-Methoxyphenyl nor-lobelane (GZ-252B), para-methoxyphenyl lobelane (GZ-252C), and 2,4-dichlorphenyl lobelane (GZ-260C) were selected for their high inhibitory potency in the [3H]DA uptake assay and moderate potency inhibiting [3H]DTBZ binding. 2,6-Bis(2-(biphenyl-4-yl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride (GZ-272B) was selected for its moderate inhibitory potency in the [3H]DA uptake assay and lack of affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site. Kinetic analyses were conducted in the absence (control) and presence of analog concentration based on Ki values obtained from the inhibition studies: lobeline (0.47 μM), lobelane (0.045 μM), TBZ (0.054 μM), GZ-252B (0.013 μM), GZ-252C (0.015 μM), GZ-260C (0.016 μM) and GZ-272B (0.127 μM). Incubations were initiated by the addition of 100 μl of vesicular suspension to 300 μl of assay buffer, 50 μl of inhibitor and 50 μl of a range of [3H]DA concentrations (0.001–5.0 μM). Nonspecific uptake was determined in the presence of Ro4-1284 (10 μM). After an incubation period of 8 min, [3H]DA uptake was terminated by filtration, and radioactivity retained by the filters was determined as described previously.

Vesicular [3H]DA Release Assay.

Striatal synaptic vesicle preparations were isolated as described previously, with the final pellet resuspended in 2.7 ml of assay buffer. Vesicles were preloaded with [3H]DA via the application of 300 μl of 0.3 μM [3H]DA solution added to the 2.7 ml containing the resuspended vesicles, followed by incubation at 37°C for 8 min. Samples containing the vesicle suspension were centrifuged at 100,000g for 1 h at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in a final volume of 4.2 ml of assay buffer. Aliquots of [3H]DA-preloaded vesicular suspension (180 μl) were added to tubes in the absence or presence of various concentrations of inhibitor (1 nM–1 mM), and incubated at 37°C for 8 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 2.5 ml of ice-cold assay buffer, followed by rapid filtration. Radioactivity retained by the filters represents [3H]DA remaining in the vesicles after exposure to analog. Analog-evoked [3H]DA release was calculated for each analog concentration by subtracting the radioactivity remaining on the filter in the presence of analog from the amount of radioactivity in the control samples.

Synaptosomal [3H]DA Uptake Assay.

Inhibition of [3H]DA uptake into rat striatal synaptosomes through DAT was conducted according to previously reported methods (Teng et al., 1997). Striata from individual rats were homogenized in ice-cold sucrose solution containing 5 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4, with 16 up-and-down strokes of a Teflon pestle homogenizer (clearance ≈ 0.003 inch). Homogenates were centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatants were centrifuged at 20,000g for 17 min at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in 2.4 ml of assay buffer (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM α-d-glucose, 25 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM pargyline, and 0.1 mM ascorbic acid, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4). Assays were performed in duplicate in a total volume of 500 μl. Aliquots of the synaptosomal suspension (25 μl) were added to tubes containing assay buffer and various concentrations of analog (100 μM–1 nM), and incubated at 34°C for 5 min. Nonspecific uptake was determined in the presence of nomifensine (10 μM). Samples were placed on ice, and 50 μl of 0.1 μM [3H]DA was added to each tube and incubated for 10 min at 34°C. Reactions were terminated by addition of 3 ml of ice-cold assay buffer and subsequent filtration. Radioactivity retained by the filters (presoaked for 2 h in assay buffer) was determined as described previously.

Data Analysis.

For inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding, specific binding was determined by subtracting nonspecific binding from total binding. For inhibition of [3H]DA uptake, specific uptake was determined by subtracting nonspecific uptake from total uptake. Concentrations of analog that produced 50% inhibition of maximal binding or uptake (IC50 values) or elicited 50% of [3H]DA release (EC50 values) were determined from the concentration-response curves via an iterative curve-fitting program (Prism 4.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Inhibition constants (Ki values) were determined by using the Cheng-Prusoff equation (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973). For analysis of [3H]DA uptake kinetics, Km and Vmax values were determined from concentration-response curves for specific [3H]DA uptake. Paired two-tailed t tests were performed on the log Km and arithmetic Vmax values to determine differences between analog and control and for comparison of Ki values between analogs within either the [3H]DA uptake or [3H]DTBZ binding assays. Saturation experiments to determine Km and Vmax values for lobeline, lobelane, and TBZ were conducted in a different series of experiments than those for GZ-252B, GZ-252C and GZ-260C; separate contemporaneous controls were included in the design of each of the series of experiments. Because no significant difference in the control values between the two series of experiments were found, the values for controls were collapsed for clarity of presentation in Table 2. Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between Ki values for [3H]DA uptake and [3H]DTBZ binding.

TABLE 2.

Km and Vmax values from kinetic analysis of [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2 for lobelane analogs and standard inhibitors

Concentrations of compounds used for kinetic analyses were the Ki concentrations from the inhibition curves illustrated in Fig. 5 (lobeline, 470 nM; lobelane, 45 nM; TBZ, 54 nM; GZ-252B, 13 nM; GZ-252C, 15 nM; GZ-272B, 127 nM and GZ-260C, 16 nM). b Control represents the absence of compound. Saturation experiments to determine Km and Vmax values for lobeline, lobelane, and TBZ were conducted in a different series of experiments than those for GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C; separate contemporaneous controls were included in the design of each of the series of experiments. Because no significant difference in the control values between the two series of experiments was found, the values for control were collapsed for clarity of presentation. Data are mean (± S.E.M.) for Km and Vmax values.

| Compound | Km | Vmax |

|---|---|---|

| μM | pmol/min/mg | |

| Control | 0.14 ± 0.014 | 43.0 ± 3.61 |

| Lobeline | 0.34 ± 0.049* | 43.2 ± 5.38 |

| Lobelane | 0.49 ± 0.027* | 51.6 ± 3.10 |

| TBZ | 0.44 ± 0.072* | 53.2 ± 6.21 |

| GZ-252B | 0.40 ± 0.077* | 37.1 ± 3.71 |

| GZ-252C | 0.34 ± 0.052* | 33.9 ± 2.73 |

| GZ-272B | 1.27 ± 0.40* | 54.8 ± 5.33 |

| GZ-260C | 0.68 ± 0.13* | 65.1 ± 10.9 |

P < 0.05 vs. control based on two-tailed t test (n = 6–8 rats/compound).

Results

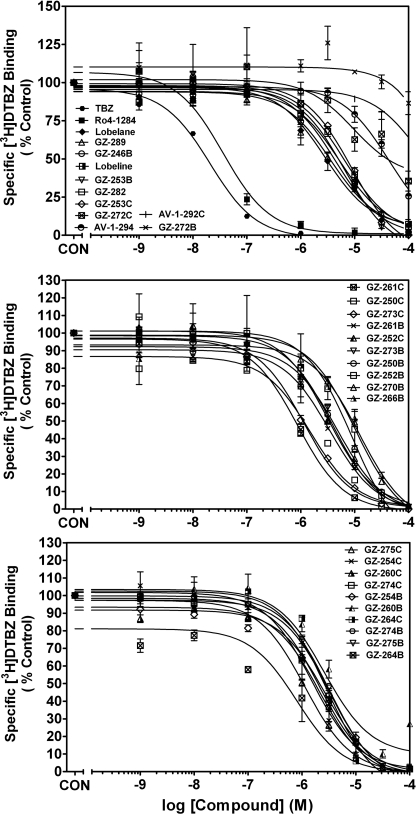

Inhibition of [3H]DTBZ Binding.

Lobelane and its analogs inhibited [3H]DTBZ binding to synaptic vesicle membranes obtained from rat whole brain (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The majority of analogs exhibited maximal inhibition (> 90%) of [3H]DTBZ binding, with the exception of GZ-272B and GZ-272C (Imax = 23.0 ± 10.4 and 64.6 ± 6.56%, respectively). The majority of analogs exhibited affinity for VMAT2 in the 1- to 10-μM range. Increasing the size of the n-alkyl group from N-methyl (lobelane) to N-ethyl (GZ-282) to N-propyl (GZ-289) did not alter potency at the binding site. Generally, there were no significant differences between the N-methylated and respective N-demethylated compounds with respect to affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site. However, the meta-CF3 nor-lobelane analog (GZ-264B) had a lower affinity (Ki = 9.90 ± 2.01 μM, p < 0.05) than its corresponding N-methyl analog (GZ-264C; Ki = 1.51 ± 0.07 μM). Likewise, the biphenyl analog (GZ-272B) showed no affinity (Ki > 100 μM) for the binding site, but the corresponding N-methylated analog (GZ-272C) had higher affinity (Ki = 10.7 ± 6.60 μM, p < 0.05) relative to GZ-272B. Also of note, the indole-bearing analog (AV-1-294) and the extensively aromatized analog containing N-benzylindole moieties (AV-1-292C) had low affinity (Ki = 25.4 ± 2.36 and 97.3 ± 6.36 μM, respectively) for the [3H]DTBZ binding site on VMAT2.

Fig. 4.

Lobelane and phenyl-substituted lobelane analogs inhibit [3H]DTBZ binding to striatal vesicle membranes. Top, inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding by VMAT2 standards and lobelane analogs whose structures share an extended distance between the N-methyl and the piperidine ring and contain phenyl, N-benzylindole, indole, and methyl substituents. Middle, inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding by analogs bearing moieties that contain oxygen. Bottom, concentration-response curves for analogs bearing highly electronegative atoms or groups on the phenyl rings. Insets, the order of presentation for the analogs is from high to low affinity at the [3H]DTBZ binding site. Control represents [3H]DTBZ binding in the absence of compound. Data are mean (± S.E.M.) specific [3H]DTBZ binding as a percentage of control (1431 ± 97.24 fmol/mg; n = 3–4 rats/compound).

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding and [3H]DA uptake by VMAT2 standards and phenyl-substituted lobelane analogs

Data represent mean (+ S.E.M.; n = 3–5 rats/compound).

| Compound | [3H]DTBZ Binding |

VMAT2 [3H]DA Uptake |

Binding/Uptake Ki Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki | Imax | Ki | Imax | ||

| μM | % | nM | % | ||

| TBZ | 0.013 ± 0.0010 | 100 | 54 ± 15 | 92 ± 3.7 | 0.24 |

| Ro4-1284 | 0.028 ± 0.0030 | 100 | 106 ± 11 | 97 ± 2.4 | 0.26 |

| Lobeline | 2.8 ± 0.64 | 100 | 470 ± 45 | 97 ± 3.2 | 6 |

| Lobelane | 0.97 ± 0.19 | 90 ± 2.7 | 45 ± 2.0 | 100 | 22 |

| GZ-246B | 2.3 ± 0.21 | 98 ± 0.53 | 43 ± 8.0 | 99 ± 0.76 | 53 |

| GZ-282 | 3.4 ± 0.67 | 94 ± 0.75 | 60 ± 5.0 | 100 | 57 |

| GZ-289 | 1.9 ± 0.25 | 98 ± 0.59 | 87 ± 4.0 | 98 ± 0.62 | 22 |

| GZ-274B | 1.6 ± 0.10 | 100 | 42 ± 11 | 100 | 38 |

| GZ-274C | 1.1 ± 0.070 | 100 | 57 ± 10 | 100 | 19 |

| GZ-275B | 1.6 ± 0.080 | 100 | 36 ± 6.0 | 100 | 44 |

| GZ-275C | 0.57 ± 0.050 | 100 | 93 ± 18 | 97 ± 1.8 | 6 |

| GZ-254B | 1.3 ± 0.080 | 100 | 21 ± 4.0 | 98 ± 0.95 | 62 |

| GZ-254C | 0.98 ± 0.31 | 98 ± 2.4 | 30 ± 8.0 | 99 ± 1.5 | 33 |

| GZ-253B | 3.2 ± 0.10 | 100 | 59 ± 10 | 96 ± 2.5 | 54 |

| GZ-253C | 4.4 ± 0.18 | 100 | 154 ± 8.0 | 100 | 29 |

| GZ-272B | >100 | 23 ± 10 | 127 ± 34 | 96 ± 1.5 | 787 |

| GZ-272C | 11 ± 6.6 | 65 ± 6.6 | 34 ± 8.0 | 96 ± 1.7 | 323 |

| GZ-264B | 9.9 ± 2.0 | 96 ± 2.2 | 836 ± 361 | 97 ± 2.4 | 12 |

| GZ-264C | 1.5 ± 0.070 | 100 | 190 ± 15 | 96 ± 1.9 | 8 |

| GZ-266B | 6.0 ± 1.8 | 97 ± 0.44 | 247 ± 42 | 99 ± 0.83 | 24 |

| GZ-273B | 1.9 ± 0.19 | 99 ± 0.44 | 26 ± 4.0 | 100 | 73 |

| GZ-273C | 0.58 ± 0.040 | 100 | 26 ± 4.0 | 99 ± 1.5 | 22 |

| GZ-261B | 1.7 ± 0.070 | 98 ± 0.20 | 40 ± 6.0 | 98 ± 1.6 | 43 |

| GZ-261C | 0.43 ± 0.030 | 100 | 30 ± 5.0 | 99 ± 1.2 | 14 |

| GZ-252B | 3.3 ± 0.82 | 100 | 13 ± 3.0 | 97 ± 1.1 | 254 |

| GZ-252C | 1.7 ± 0.20 | 100 | 15 ± 2.0 | 98 ± 1.7 | 113 |

| GZ-270B | 5.3 ± 0.47 | 98 ± 1.5 | 47 ± 17 | 99 ± 0.74 | 113 |

| GZ-260B | 1.3 ± 0.18 | 88 ± 1.6 | 182 ± 5.0 | 100 | 7 |

| GZ-260C | 1.0 ± 0.060 | 98 ± 0.35 | 16 ± 5.0 | 100 | 63 |

| GZ-250B | 2.3 ± 0.16 | 100 | 48 ± 010 | 100 | 48 |

| GZ-250C | 0.52 ± 0.25 | 100 | 43 ± 11 | 100 | 12 |

| AV-1-292C | 98 ± 6.4 | 100 | 73 ± 27 | 100 | 1342 |

| AV-1-294 | 25 ± 2.4 | 100 | 2130 ± 280 | 100 | 12 |

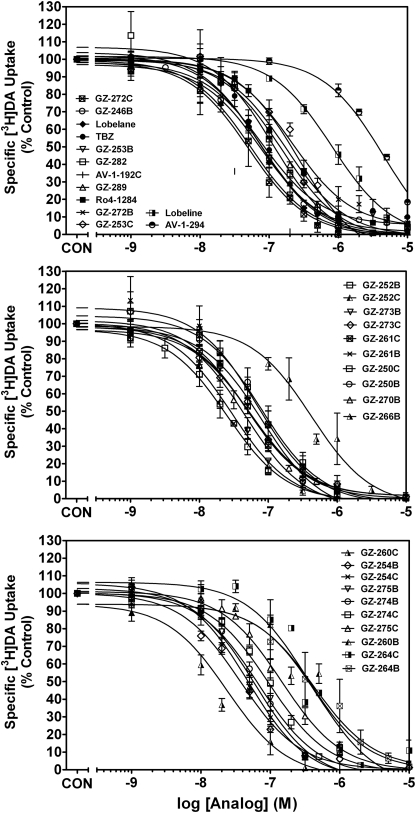

Inhibition of [3H]DA Uptake into Synaptic Vesicles.

Analog-induced inhibition of [3H]DA uptake by VMAT2 and the relationship to inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding was evaluated (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Analogs in this sublibrary exhibited maximal inhibition (> 90%) of [3H]DA uptake into isolated vesicles. The majority of the analogs had similar potency compared with lobelane inhibiting VMAT2 function. Two exceptions with 5- to 18-fold lower affinity than lobelane include GZ-264B, a nor-analog bearing meta-trifluoromethyl phenyl substituents (Ki = 840 ± 361 nM), and GZ-266B, a nor-analog bearing para-acetoxy phenyl substituents (Ki = 247 ± 15.0 nM).

Fig. 5.

Lobelane and its phenyl ring-substituted analogs inhibit [3H]DA uptake in rat striatal synaptic vesicle preparations. Top, data are representative of inhibition of [3H]DA uptake by the VMAT2 standards, analogs with an extended distance between the N-methyl and the piperidine ring, and analogs containing phenyl, N-benzylindole, indole, and methyl substituents. Middle, inhibition of [3H]DA uptake by analogs bearing moieties that contain oxygen. Bottom, concentration response curves of analogs bearing highly electronegative atoms or groups on the phenyl rings. Insets, the order of presentation for the analogs is from high to low affinity for the [3H]DA uptake site. Control represents [3H]DA uptake in the absence of compound. Data are mean (± S.E.M.) specific [3H]DA uptake as a percentage of control (50.7 ± 2.59 pmol/min/mg; n = 3–5 rats/compound).

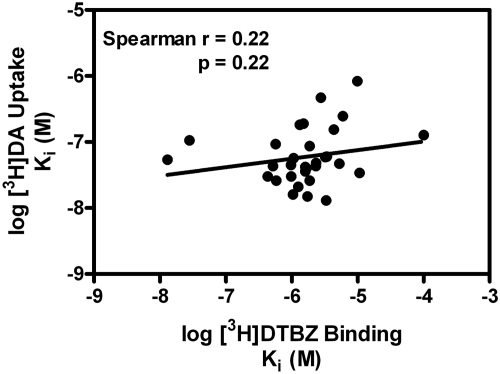

The high-affinity standard compounds, TBZ and Ro4-1284, which are structurally distinct compared with the phenyl-substituted lobelane analogs, exhibited Ki values not different between VMAT2 binding and uptake assays. In contrast, the phenyl-substituted lobelane analogs displayed one to two orders of magnitude greater potency inhibiting [3H]DA uptake compared with [3H]DTBZ binding (see affinity ratio, Table 1), although no correlation between the Ki values in these two VMAT2 assays was found (Spearman, r = 0.22; p = 0.25; Fig. 6). Three compounds exhibited little to no affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site on VMAT2, but had moderate affinity in inhibiting [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2 (Table 1): GZ-272B (binding Ki > 100 μM; uptake Ki = 127 ± 34 nM), AV-1-292C (binding Ki = 97.3 ± 6.36 μM; uptake Ki = 73 ± 27 nM) and AV-1-294 (binding Ki = 25.4 ± 2.36 μM; uptake Ki = 2130 ± 280 nM).

Fig. 6.

Lack of correlation between phenyl ring-substituted lobelane analog inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding and [3H]DA uptake. Data presented are Ki values obtained from concentration-response curves for analog-induced inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding and [3H]DA uptake (Figs. 4 and 5, respectively). Spearman analysis of these data indicates a lack of correlation (Spearman r = 0.22; p = 0.22) between the ability of the compounds of this series to inhibit [3H]DTBZ binding to VMAT2 and inhibit [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2.

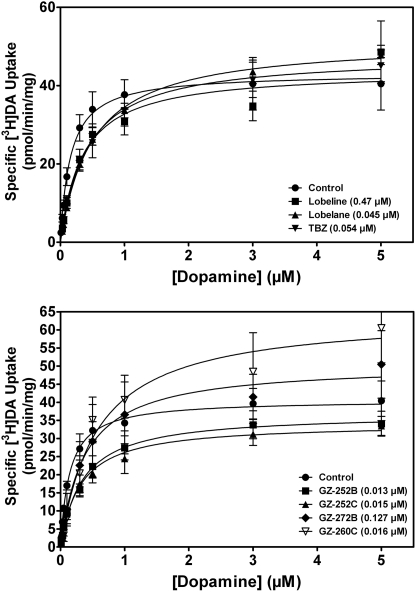

To elucidate the mechanism of action (i.e., competitive versus noncompetitive) for inhibition of VMAT2 function, kinetic analyses of [3H]DA uptake were conducted (Fig. 7 and Table 2). In comparison to the analogs, lobeline, lobelane, and TBZ increased the Km value for DA (0.34 ± 0.049, 0.49 ± 0.027, and 0.44 ± 0.072 μM, respectively; p < 0.05) compared with control (Km = 0.18 ± 0.017 μM), without altering Vmax, suggesting a competitive inhibition of VMAT2 function. Analogs with highest potency in the [3H]DA uptake assay and moderate potency in the [3H]DTBZ binding assay (i.e., GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C) increased the Km value (0.40 ± 0.077, 0.34 ± 0.052, and 0.68 ± 0.13 μM, respectively; p < 0.05) for DA uptake compared with control (Km = 0.10 ± 0.012 μM), without altering Vmax, indicating competitive inhibition of VMAT2 function. GZ-272B, which exhibited moderate potency inhibiting [3H]DA uptake and no affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding assay, also increased the Km value (1.27 ± 0.40 μM; p < 0.05) and did not alter Vmax compared with control, consistent with competitive inhibition of VMAT2 function.

Fig. 7.

Kinetic analysis of the inhibition of [3H]DA uptake by lobeline, lobelane, TBZ, GZ-252B, GZ-252C, GZ-272B, and GZ-260C. The mechanism of [3H]DA uptake inhibition for VMAT2 standards was determined for analogs exhibiting the highest potency inhibiting [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2 and the analog having no affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site, but which had moderate affinity inhibiting [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2. Concentration-response curves for VMAT2 standards are at the top, and those for the analogs are at the bottom. Concentrations of all compounds used for the kinetic analysis were the respective Ki concentrations from the inhibition curves illustrated in Fig. 5. The concentrations of inhibitor are included in parentheses adjacent to the compound name. Vmax and Km values (± S.E.M.) are presented in Table 2 (n = 6–8 rats/compound).

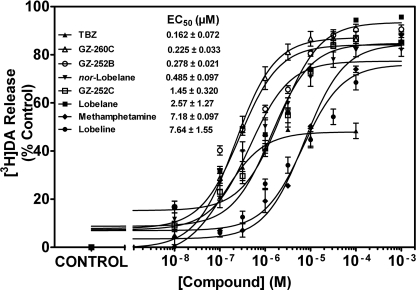

Analog-Evoked [3H]DA Release from Synaptic Vesicles.

Compounds evaluated for mechanism of action were also assessed for their ability to evoke concentration-dependent release of [3H]DA from isolated striatal synaptic vesicles and compared with methamphetamine (Fig. 8). At the plateau in the concentration response, Emax was ∼75% of vesicle [3H]DA content for each of the analogs and methamphetamine. The exception was TBZ, for which the plateau was reached at ∼50% of vesicle [3H]DA content.

Fig. 8.

Lobelane analog-evoked [3H]DA release from isolated synaptic vesicles. Data represent the ability of VMAT2 standards and the most potent compounds within this series in the [3H]DA uptake inhibition assay to evoke DA release from synaptic vesicles. Inset, the order of presentation of EC50 values for the analogs and standards is from high to low potency for the ability to release [3H]DA. Control represents [3H]DA release in the absence of compound. Data are mean (± S.E.M.) specific [3H]DA release as a percentage of the control (n = 3–4 rats/compound).

For the compounds evaluated in the vesicular [3H]DA release assay, a range of EC50 values was obtained (162 nM–7.64 μM). TBZ had the highest potency (0.162 ± 0.072 μM). The EC50 value for lobeline was not different from that of methamphetamine (7.64 ± 1.55 and 7.18 ± 0.097 μM, respectively). Lobelane was ∼3-fold more potent (2.57 ± 1.27 μM; p < 0.05) compared with lobeline and methamphetamine. nor-Lobelane exhibited a 5-fold increase in potency (0.49 ± 0.097 μM; p < 0.05) compared with lobeline. Likewise, N-demethylation of the para-methoxy compound GZ-252C (1.45 ± 0.32 μM) afforded a 6-fold increase (p < 0.05) in potency (GZ-252B; 0.225 ± 0.033 μM).

Inhibition of [3H]DA Uptake into Striatal Synaptosomes.

The ability to inhibit [3H]DA uptake into striatal synaptosomes through DAT was also evaluated for the three most potent analogs, GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C (Table 3). GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C exhibited maximal inhibition of 100% and were equipotent (1.05 ± 0.074, 1.89 ± 0.416, and 3.32 ± 1.49 μM, respectively) inhibiting [3H]DA uptake at DAT. It is noteworthy that each compound was two to three orders of magnitude more potent inhibiting DA uptake at VMAT2 than at DAT.

TABLE 3.

GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C inhibit specific [3H]DA uptake at DAT

Analogs having the highest potency for inhibition of [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2 using rat isolated vesicle preparations were used. Data are mean (± S.E.M.) Ki values for inhibition of [3H]DA uptake into rat striatal synaptosomes (n = 4 rats/analog).

| Analog | Ki |

|---|---|

| μM | |

| GZ-252B | 1.05 ± 0.074 |

| GZ-252C | 1.89 ± 0.416 |

| GZ-260C | 3.32 ± 1.49 |

Discussion

Lobeline decreases the behavioral effects of methamphetamine by inhibiting VMAT2 function and redistributing DA storage within the presynaptic terminal (Harrod et al., 2001, 2003; Dwoskin and Crooks, 2002). However, lobeline is nonselective, inhibiting nAChRs and plasmalemma neurotransmitter transporters (Miller et al., 2000, 2004). The objective of this study was to conduct SARs on a series of chemically defunctionalized, phenyl-substituted lobelane analogs, identify those with greater VMAT2 selectivity, and elucidate the mechanism underlying inhibition of VMAT2 function. Introduction of various aromatic substituents into lobelane afforded novel compounds that are more potent inhibitors of VMAT2 function relative to lobeline. These analogs show little affinity for nAChRs (Zheng et al., 2005b). No correlation was found between analog affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site and inhibition of [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2, suggesting that these analogs interact with two different sites on VMAT2. It is noteworthy that several analogs (GZ-272B, AV-1-292C, and AV-1-294) were identified, having little to no affinity for the [3H]DTBZ binding site, but competitively inhibiting VMAT2 function, suggesting selective interaction with the substrate site. Thus, structural modification of lobelane affords potent, selective VMAT2 inhibitors and reveals two distinct pharmacological targets on VMAT2.

[3H]DTBZ, an established ligand probing interactions with VMAT2, has been used clinically to evaluate severity of neuronal degeneration in numerous neurological diseases (Lehéricy et al., 1994; Wilson et al., 1996). The majority of analogs in the current series exhibited similar affinity (Ki = 1–10 μM) for the [3H]DTBZ binding site, indicating that the nature, substitution pattern, and electronic properties of the corresponding aromatic substituents had minimal influence on affinity at this site. However, GZ-272B lacked affinity at this site, and the closely related, structurally bulky analog 2,6-bis(2-(biphenyl-4-yl)ethyl)-1-methyl piperidine hydrochloride (GZ-272C) did not completely inhibit [3H]DTBZ binding. The extensively aromatized analogs, AV-1-292C and AV-1-294, also exhibited little or no affinity for this site. Thus, when the aromatic moiety is changed from a phenyl group to a more extended biphenyl, N-benzylindole, or indole group, the increased size of the aromatic moiety was detrimental to affinity at the DTBZ binding site.

Although [3H]DTBZ binding provides important information regarding the interaction of small molecules with VMAT2, this approach does not provide evidence regarding VMAT2 function, which can be determined directly. Similar to the binding assay, the nature, substitution pattern, and electronic properties of the aromatic substituents had little influence on affinity (Ki = 20–100 nM) in the functional assay. Exceptions include the most potent (Ki < 20 nM) analogs, the N-methyl-2,4-dichlorophenyl analog (GZ-260C) and the para-methoxy analogs (GZ-252B, GZ-252C). No differences in inhibitory potency were observed between the nor-analogs and their corresponding N-methyl analogs, with the exception of the 2,4-dichlorophenyl compounds, GZ-264B and GZ-264C, in which the N-methyl analog was 11-fold more potent than the nor-analog. Further SAR developed around the most potent analogs may provide even greater improvements in affinity.

One objective of the current study was to determine whether binding at the [3H]DTBZ site predicts ability of an analog to inhibit transporter function. No correlation between data from these two assays was found for this series of compounds, suggesting interaction at an alternative site on VMAT2. It is noteworthy that Ki values for TBZ and Ro4-1284 were not different between the two assays, suggesting that they interact at the [3H]DTBZ binding site to inhibit DA uptake at VMAT2. The majority of the analogs exhibited a 10- to 65-fold greater potency in the functional assay relative to the binding assay. However, exceptions were GZ-252B, GZ-252C, GZ-270B, and GZ-272C, exhibiting 100- to 300-fold greater potency inhibiting [3H]DA uptake than [3H]DTBZ binding. The extensively aromatized analogs, GZ-272B, AV-1-292C, and AV-1-294, had little to no affinity at the [3H]DTBZ binding site, but had moderate affinity in the functional assay, providing additional evidence for interaction at distinct sites on VMAT2. Alternatively, the analogs could bind primarily at the DTBZ site, yet invoke various conformational changes in VMAT2, which lead to different amounts of inhibition of DA uptake, resulting in a lack of correlation between binding and uptake. An example providing precedence for this interpretation is allosteric modulation of muscarinic receptors by various modulators acting at the same site, which leads to both potentiation and inhibition of activity, indicative of different allosteric conformational states (Jakubic et al., 1997; Kenakin, 2006).

Previous studies indicate that compounds that interact with VMAT2 can be classified as either uptake inhibitors or substrates based on differences in potency between binding and functional assays. Substrates deplete intravesicular DA content via a dual mechanism of uptake inhibition and release and exhibit higher potencies in functional versus binding assays; uptake inhibitors are equipotent in both assays (Andersen, 1987; Matecka et al., 1997; Rothman et al., 1999; Partilla et al., 2006). With respect to the current findings, TBZ and Ro4-1284 are equipotent in the binding and uptake assays, consistent with the interpretation that these standards are uptake inhibitors. In contrast, the remaining analogs in the current series, including GZ-252B, GZ-252C, GZ-270B, GZ-272C, GZ-272B, AV-1-292C, and AV-1-294, which were more potent at inhibiting DA uptake than interacting at the [3H]DTBZ binding site, are substrates for VMAT2.

To evaluate whether the analogs release DA as a component of their mechanism of presynaptic DA redistribution, analogs with the highest potency (< 20 nM) in the uptake assay were evaluated, along with standards, for their ability to evoke [3H]DA release from striatal vesicles. Methamphetamine and lobeline evoke [3H]DA release from vesicular preparations (EC50 = 11 and 25 μM, respectively; Teng et al., 1998; Partilla et al., 2006). Current results are in agreement with these previous findings. Relative to lobeline and methamphetamine, lobelane had both higher potency and efficacy releasing vesicular [3H]DA. Analogs with para-methoxyphenyl and 2,4-dichlorphenyl substituents had enhanced potency relative to lobelane and equivalent efficacy compared with lobelane. Nor-lobelane and GZ-252B were more potent than their corresponding N-methylated analogs in releasing [3H]DA. TBZ is prominent in exhibiting maximal [3H]DA release of ∼50% of that evoked by the majority of analogs evaluated, in agreement with previous findings (Partilla et al., 2006), supporting its mechanism as an uptake inhibitor. Thus, the current results using novel lobelane analogs support previous observations that substrates for VMAT2 release DA from synaptic vesicles.

To further evaluate mechanism of action of the analogs classified as VMAT2 substrates, kinetic analyses of DA uptake at VMAT2 were conducted. To further evaluate the mechanism of action of TBZ, kinetic analyses were conducted, as such data are not available in the literature. All compounds inhibited [3H]DA uptake in a competitive manner. TBZ has been classified previously as a noncompetitive inhibitor of VMAT2 (Scherman and Henry, 1984; Near, 1986); however, this is based on findings that the substrate concentration necessary to displace [3H]TBZ or [3H]DTBZ from its binding site was two to three orders of magnitude greater than that required to inhibit [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2. Collectively, the results demonstrating that TBZ binds to a site on VMAT2 distinct from the substrate recognition site and that inhibition of VMAT2 function is surmountable indicate that TBZ is a competitive allosteric inhibitor of VMAT2. In addition, the current results demonstrate the complexity of the mechanism of action of TBZ at VMAT2, in that it exhibits maximal release of [3H]DA that is ∼50% of that evoked by the majority of the current analogs. Thus, GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C may be attractive tools to evaluate VMAT2 function, because the existing compound library available to study VMAT2 is limited.

A study evaluating the ability of a series of lobelane and meso-transdiene stereoisomers to inhibit methamphetamine-evoked endogenous DA release from striatal slices determined that inhibition of DAT function may play a role in inhibiting the effect of methamphetamine (Nickell et al., 2010); several of the analogs that inhibited methamphetamine were equipotent at DAT and VMAT2. To determine the selectivity of the most potent VMAT2 inhibitors, GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C were evaluated for inhibition of [3H]DA uptake at DAT. These analogs displayed 80- to 200-fold greater selectivity for VMAT2 over DAT. The greater selectivity for VMAT2 increases the likelihood that GZ-252B, GZ-252C, and GZ-260C would not produce high extracellular DA concentrations and thus are not predicted to be rewarding, similar to lobeline and lobelane (Harrod et al., 2001; Neugebauer et al., 2007; Nickell et al., 2010).

In summary, the current findings demonstrate that introduction of various moieties into the phenyl rings of lobelane affords analogs with enhanced potency for inhibition of [3H]DA uptake at VMAT2 compared with lobelane. It is noteworthy that analogs with optimal inhibitory potency (Ki < 20 nM) are those bearing para-methoxyphenyl and 2,4-dichlorophenyl substituents, and these compounds also act as substrates for transport. These analogs also elicit DA release at concentrations 10- to 700-fold higher than those that inhibit uptake at VMAT2. GZ-252C is distinguished as the lead compound, acting as a substrate inhibitor at VMAT2, being 130-fold selective for VMAT2 over DAT, and 700-fold more potent inhibiting DA uptake at VMAT2 than releasing DA from the vesicle. Finally, [3H]DTBZ binding assays do not predict inhibition of DA uptake by VMAT2 for this series of compounds.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ashish Vartak (College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) for the synthesis of AV-1-292C and AV-1-294.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants DA013519, T32-DA016176].

The University of Kentucky holds patents on lobeline and the analogs described in the current work. A potential royalty stream to L.P.D., G.Z., and P.A.C. may occur consistent with University of Kentucky policy. Both L.P.D. and P.A.C. are founders of and have financial interest in Yaupon Therapeutics and have licensed University of Kentucky patents on some of the compounds evaluated in the current study.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.110.172882.

Abbreviations:

- DAT

- dopamine transporter

- DA

- dopamine

- DTBZ

- dihydrotetrabenazine

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- Ro4-1284

- (2R,3S,11bS)-2-ethyl-3-isobutyl-9,10-dimethoxy-2,2,4,6,7,11b-hexahydro-1H-pyrido[2,1-a]isoquinolin-2-ol

- SAR

- structure-activity relationship

- TBZ

- tetrabenazine

- VMAT2

- vesicular monoamine transporter-2

- AV-1-292C

- 2,6-bis[2-(1-benzyl-1H-indole-3-yl)ethyl]-1-methylpiperidine hemifumarate

- AV-1-294

- 2,6-bis[2-(1H-indole-3-yl)ethyl]-1-methylpiperidine monofumarate

- GZ-272B

- 2,6-bis(2-(biphenyl-4-yl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride

- GZ-272C

- 2,6-bis(2-(biphenyl-4-yl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride

- GZ-252B

- 2,6-bis(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)piperidine hydrochloride

- GZ-252C

- 2,6-bis(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride

- GZ-260C

- 2,6-bis(2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl)-1-methylpiperidine hydrochloride

- GZ-252B

- para-methoxyphenyl nor-lobelane

- GZ-252C

- para-methoxyphenyl lobelane

- GZ-260C

- 2,4-dichlorphenyl lobelane.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Nickell, Zheng, Crooks, and Dwoskin.

Conducted experiments: Nickell, Zheng, and Deaciuc.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Zheng and Crooks.

Performed data analysis: Nickell, Zheng, Deaciuc, Crooks, and Dwoskin.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Nickell, Zheng, Crooks, and Dwoskin.

References

- Andersen PH. (1987) Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of [3H]GBR 12935 binding in vitro to rat striatal membranes: labeling of the dopamine uptake complex. J Neurochem 48:1887–1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs CA, McKenna DG. (1998) Activation and inhibition of the human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by agonists. Neuropharmacology 37:1095–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. (2000) Methamphetamine rapidly decreases vesicular dopamine uptake. J Neurochem 74:2221–2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. (1973) Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol 22:3099–3108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MW, Majchrzak MJ, Arnerić SP. (1993) Effects of lobeline, a nicotinic receptor agonist, on learning and memory. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 45:571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, Acquas E, Carboni E, Valentini V, Lecca D. (2004) Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology 47:227–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. (2002) A novel mechanism of action and potential use for lobeline as a treatment for psychostimulant abuse. Biochem Pharmacol 63:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrod SB, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA, Klebaur JE, Bardo MT. (2001) Lobeline attenuates d-methamphetamine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298:172–179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrod SB, Dwoskin LP, Green TA, Gehrke BJ, Bardo MT. (2003) Lobeline does not serve as a reinforcer in rats. Psychopharmacology 165:397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubík J, Bacáková L, El-Fakahany EE, Tucek S. (1997) Positive cooperativity of acetylcholine and other agonists with allosteric ligands on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 52:172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin TP. (2006) A Pharmacology Primer: Theory, Applications, and Methods, 2nd Ed, Academic Press, Burlington, MA [Google Scholar]

- Lehéricy S, Brandel JP, Hirsch EC, Anglade P, Villares J, Scherman D, Duyckaerts C, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y. (1994) Monoamine vesicular uptake sites in patients with Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease, as measured by tritiated dihydrotetrabenazine autoradiography. Brain Res 659:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang NY, Rutledge CO. (1982) Comparison of the release of [3H]dopamine from isolated corpus striatum by amphetamine, fenfluramine and unlabelled dopamine. Biochem Pharmacol 31:983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DY, Kim YS, Miwa S. (2004) Influence of lobeline on catecholamine release from the isolated perfused rat adrenal gland. Auton Neurosci 110:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantle TJ, Tipton KF, Garrett NJ. (1976) Inhibition of monoamine oxidase by amphetamine and related compounds. Biochem Pharmacol 25:2073–2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matecka D, Lewis D, Rothman RB, Dersch CM, Wojnicki FH, Glowa JR, DeVries AC, Pert A, Rice KC. (1997) Heteroaromatic analogs of 1-[2-(diphenylmethoxy) ethyl]- and 1-[2-[bis(4-fluorophenyl)methoxy]ethyl]-4-(3-phenylpropyl)piperazines (GBR 12935 and GBR 12909) as high-affinity dopamine reuptake inhibitors. J Med Chem 40:705–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DK, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP. (2000) Lobeline inhibits nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow from rat striatal slices and nicotine-evoked 86Rb+ efflux from thalamic synaptosomes. Neuropharmacology 39:2654–2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DK, Crooks PA, Teng L, Witkin JM, Munzar P, Goldberg SR, Acri JB, Dwoskin LP. (2001) Lobeline inhibits the neuronal and behavioral effects of amphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296:1023–1034 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DK, Crooks PA, Zheng G, Grinevich VP, Norrholm SD, Dwoskin LP. (2004) Lobeline analogs with enhanced affinity and selectivity for plasmalemma and vesicular monoamine transporters. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:1035–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Near JA. (1986) [3H]Dihydrotetrabenazine binding to bovine striatal synaptic vesicles. Mol Pharmacol 30:252–257 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer NM, Harrod SB, Stairs DJ, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. (2007) Lobelane decreases methamphetamine self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 571:33–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickell JR, Krishnamurthy S, Norrholm S, Deaciuc G, Siripurapu KB, Zheng G, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP. (2010) Lobelane inhibits methamphetamine-evoked dopamine release via inhibition of the vesicular monoamine transporter-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332:612–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partilla JS, Dempsey AG, Nagpal AS, Blough BE, Baumann MH, Rothman RB. (2006) Interaction of amphetamines and related compounds at the vesicular monoamine transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319:237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J, Mooslehner KA, Chan PM, Emson PC, Stamford JA. (2003) Presynaptic control of striatal dopamine neurotransmission in adult vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) mutant mice. J Neurochem 85:898–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifl C, Drobny H, Reither H, Hornykiewicz O, Singer EA. (1995) Mechanism of the dopamine-releasing actions of amphetamine and cocaine: plasmalemmal dopamine transporter versus vesicular monoamine transporter. Mol Pharmacol 47:368–373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Ayestas MA, Dersch CM, Baumann MH. (1999) Aminorex, fenfluramine, and chlorphentermine are serotonin transporter substrates. Implications for primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 100:869–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherman D, Henry JP. (1984) Reserpine binding to bovine chromaffin granule membranes. Characterization and comparison with dihydrotetrabenazine binding. Mol Pharmacol 25:113–122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Rayport S. (1990) Amphetamine and other psychostimulants reduce pH gradients in midbrain dopaminergic neurons and chromaffin granules: a mechanism of action. Neuron 5:797–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Chen TK, Lau YY, Kristensen H, Rayport S, Ewing A. (1995) Amphetamine redistributes dopamine from synaptic vesicles to the cytosol and promotes reverse transport. J Neurosci 15:4102–4108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Miner LL, Sora I, Ujike H, Revay RS, Kostic V, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Uhl GR. (1997) VMAT2 knockout mice: heterozygotes display reduced amphetamine-conditioned reward, enhanced amphetamine locomotion, and enhanced MPTP toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:9938–9943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng L, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP. (1998) Lobeline displaces [3H]dihydrotetrabenazine binding and releases [3H]dopamine from rat striatal synaptic vesicles: comparison with d-amphetamine. J Neurochem 71:258–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng L, Crooks PA, Sonsalla PK, Dwoskin LP. (1997) Lobeline and nicotine evoke [3H]overflow from rat striatal slices preloaded with [3H]dopamine: differential inhibition of synaptosomal and vesicular [3H]dopamine uptake. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 280:1432–1444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth PT, Vizi ES. (1998) Lobeline inhibits Ca2+ current in cultured neurons from rat sympathetic ganglia. Eur J Pharmacol 363:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm CJ, Johnson RA, Eshleman AJ, Janowsky A. (2008) Lobeline effects on tonic and methamphetamine-induced dopamine release. Biochem Pharmacol 75:1411–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Levey AI, Rajput A, Ang L, Guttman M, Shannak K, Niznik HB, Hornykiewicz O, Pifl C, Kish SJ. (1996) Differential changes in neurochemical markers of striatal dopamine nerve terminals in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Neurology 47:718–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Hoffman DC. (1992) Localization of drug reward mechanisms by intracranial injections. Synapse 10:247–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Norrholm SD, Crooks PA. (2005a) Defunctionalized lobeline analogues: structure-activity of novel ligands for the vesicular monoamine transporter. J Med Chem 48:5551–5560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Zhu J, Jones MD, Crooks PA. (2005b) Lobelane analogues as novel ligands for the vesicular monoamine transporter-2. Bioorg Med Chem 13:3899–3909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]