Abstract

The mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system is involved in the rewarding process of drugs of abuse and is activated during the anticipation of drug availability. However, the neurocircuitry that regulates ethanol (EtOH)-seeking has not been adequately investigated. The objectives of the present study were to determine 1) whether the posterior ventral tegmental area (p-VTA) mediates EtOH-seeking, 2) whether microinjections of EtOH into the p-VTA could stimulate EtOH-seeking, and (3) the involvement of p-VTA DA neurons in EtOH-seeking. Alcohol-preferring rats were trained to self-administer 15% EtOH and water. After 10 weeks, rats underwent extinction training, followed by 2 weeks in their home cages. During the home-cage period, rats were then bilaterally implanted with guide cannulae aimed at the p-VTA or anterior ventral tegmental area (a-VTA). EtOH-seeking was assessed by the Pavlovian spontaneous recovery model. Separate experiments examined the effects of: 1) microinjection of quinpirole into the p-VTA, 2) EtOH microinjected into the p-VTA, 3) coadministration of EtOH and quinpirole into the p-VTA, 4) microinjection of quinpirole into the a-VTA, and 5) microinjection of EtOH into the a-VTA. Quinpirole microinjected into the p-VTA reduced EtOH-seeking. Microinjections of EtOH into the p-VTA increased EtOH-seeking. Pretreatment with both quinpirole and EtOH into the p-VTA reduced EtOH-seeking. Microinjections of quinpirole or EtOH into the a-VTA did not alter EtOH-seeking. Overall, the results suggest that the p-VTA is a neuroanatomical substrate mediating alcohol-seeking behavior and that activation of local DA neurons is involved.

Introduction

Alcohol addiction is complex disorder characterized by high rates of relapse to alcohol-seeking and alcohol-taking behaviors. Given that relapse is a major obstacle in the treatment of alcohol addiction, attention has been focused on animal models to further our understanding of alcohol relapse and craving (Koob, 2000; Spanagel, 2003; Rodd et al., 2004b).

There are animal models of drug-seeking that have elucidated the neural systems and mechanisms that underlie drug-seeking behavior. The cue-induced model provided evidence that EtOH-seeking behavior is associated with increased c-fos expression in the nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex (Dayas et al., 2007), whereas the stress-induced model of EtOH-seeking behavior showed increased c-fos expression in the nucleus accumbens shell and core (Funk et al., 2006). Taken together, the two studies suggest that neural substrates in the mesocorticolimbic system may be activated during EtOH-seeking behavior.

Pharmacological studies have provided further support that the dopamine (DA) system may play a role in EtOH-seeking behavior. Cue-induced EtOH-seeking studies have shown that systemic administration of D1, D2, or D3 receptor antagonists or a D3 partial agonist can dose-dependently decrease EtOH-seeking behavior (Liu and Weiss 2002; Vengeliene et al., 2006). Antagonism of the D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens reduced EtOH-seeking behavior in the appetitive/consummatory model (Samson and Chappell, 2004). Studies using the model of context-induced drug-seeking have indicated that the D1 receptors in the nucleus accumbens may also be involved in mediating EtOH-seeking behavior (Chaudhri et al., 2009).

The activation of DA neurons in the VTA has been indicated to be involved in mediating EtOH intake and the reinforcing properties of EtOH. For instance, the reduced activity of DA neurons in the VTA with a D2 receptor agonist via local application or systemic administrations can reduce EtOH intake (Hodge et al., 1993; Nowak et al., 2000). Intracranial self-administration studies, which elucidate specific neuroanatomical sites that support drug self-administration, have provided evidence that the VTA is also involved in the reinforcing effects of EtOH (Gatto et al., 1994; Rodd et al., 2004a,c). Our previous studies have shown that the posterior VTA (p-VTA), but not the anterior VTA (a-VTA), is a neuroanatomical site mediating the reinforcing actions of EtOH (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000). Moreover, the reinforcing effects of p-VTA require the activation of dopaminergic neurons (Rodd et al., 2004c, 2005c).

Spontaneous recovery is a learning phenomenon in which reintroduction to an environment previously paired with drug self-administration reinstates response-contingent behaviors for a previously obtainable reinforcer after extinction and a period of rest (Macintosh 1977). Spontaneous recovery has been used to examine seeking behaviors for both cocaine and heroin, but the learning phenomenon has been coined the “incubation model” (Grimm et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2009). Pavlovian spontaneous recovery (PSR) is a unique phenomenon in that it is time-dependent, and the behavior seems to depend on the re-exposure of the organism to all the cues in the behavioral environment associated previously with the reinforcer. The expression of a PSR is directly correlated to reward saliency (Robbins 1990), contextual cues associated with first-learned signals, and the amount of first- and second-learned associations (Brooks, 2000). The PSR phenomenon has been asserted to be the result of an intrinsic shift away from the recent extinction (second) learning to the initial reinforced learning responses, which reflects a motivation to obtain the previously administered reward (Rescorla 2001; Bouton 2002, 2004). Therefore, the PSR model may represent a unique paradigm for studying EtOH-seeking behaviors.

Research assessing EtOH-seeking behavior through the expression of the PSR paradigm has been conducted in alcohol-preferring rats (P rats) (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b). P rats will readily express a PSR (EtOH-seeking) for EtOH (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b; Rodd et al., 2006), and this expression of EtOH PSR can be enhanced by exposure to EtOH odor or EtOH priming (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b).

The p-VTA is a neuroanatomical site mediating the reinforcing effects of EtOH, and DA neuronal activity is involved (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000; Rodd et al., 2004a,c, 2005c). Sensitivity of the p-VTA to the reinforcing effects of EtOH increases with alcohol drinking, and this enhanced sensitivity persists in the absence of alcohol for several weeks (Rodd et al., 2005a,b). These latter results suggest that long-term neuroadaptations occurred in the p-VTA. These neuroadaptations may increase EtOH-seeking and contribute to vulnerability to relapse. The objective of the present study was to test the hypothesis that p-VTA is a neuroanatomical site mediating EtOH-seeking behavior.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Adult EtOH naive female P rats from the 62nd generation, weighing 250 to 325 g at the start of the experiment, were used. Female rats were used because they maintain their body and head size better than male rats for more accurate and reliable stereotaxic placements. Previous research indicated that EtOH intake of female P rats was not affected by the estrus cycle (reviewed in McKinzie et al., 1998). Rats were maintained on a 12-h reversed light-dark cycle (lights off at 9:00 AM). Food and water were available in the home cage ad libitum throughout the experiment. All research protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee and are in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council 1996).

Chemical Agents and Vehicle.

Ethyl alcohol (190 proof; McCormick Distilling Co., Weston, MO) was diluted to 15% with distilled water for operant oral self-administration sessions or diluted with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) solution to 50 and 100 mg% EtOH for microinfusions. Quinpirole (Quin; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in the aCSF solution, and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 ± 0.1 for microinjections. The aCSF consisted of 120.0 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM Mg SO4, 25.0 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 10.0 mM d-glucose.

Operant Apparatus.

EtOH self-administration procedures were conducted in standard two-lever experimental chambers (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) contained within ventilated, sound-attenuated enclosures. Two operant levers, located on the same wall, were 15 cm above a grid floor and 13 cm apart. A trough was directly beneath each lever, from which a dipper cup could raise to present fluid. Upon a reinforced response on the respective lever, a small light cue was illuminated in the drinking trough and 4 s of dipper cup (0.1 ml) access was presented. A personal computer controlled all operant chamber functions while recording lever responses and dipper presentations.

Operant Training.

Naive P rats were placed into the operant chamber without prior training. Operant sessions were 60 min in duration and occurred daily for 10 weeks (Rodd et al., 2006). The EtOH concentration used for operant administration was 15% (v/v). During the initial 4 weeks of daily operant access, both solutions (water and EtOH) were reinforced on an FR-1 schedule. At the end of that time, the response requirement for EtOH was increased to a FR-3 schedule for 3 weeks, and then to a FR-5 schedule for 3 weeks. After the P rats had established stable levels of responding on the FR-5 schedule for EtOH and FR1 for water, they underwent 7 days of extinction (60 min/day), when neither water nor EtOH was available (Rodd et al., 2006). Water was not available during the extinction procedure because water is a primary reinforcer and has been shown to influence responding during extinction testing, i.e., superstitious behaviors (Macintosh, 1977). With the exception of no fluid being presented, the delivery system operated exactly as the preceding EtOH self-administration sessions.

Saccharin Operant Training.

The operant procedure for saccharin (SACC) self-administration was similar to the EtOH procedure but 2 weeks shorter. Operant sessions were 60 min in duration and occurred daily for 8 weeks. The SACC concentration used for operant administration was 0.025% (g/v). During the initial 4 weeks of daily operant access, both solutions (water and SACC) were reinforced on a FR-1 schedule. At the end of that time, the response requirement for SACC was increased to a FR-3 schedule for 3 weeks, and then to a FR-5 schedule for 1 week.

Stereotaxic Surgeries.

After extinction training, all rats were maintained in their home cages for 14 days. Previous research has shown that 2 weeks in a home cage produce a robust PSR (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b; Rodd et al., 2006). Stereotaxic implantation was performed after the animals had been in their home cage for 7 days. While under isoflurane anesthesia, rats were prepared for bilateral stereotaxic implantation of 22-gauge guide cannula (Plastic One, Roanoke, VA) into the p-VTA or a-VTA; the guide cannula was aimed 1.0 mm above the target region. Coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 1998) for placements to target the p-VTA were −5.6 mm posterior to bregma, +2.1 mm lateral to the midline, and −8.5 mm ventral from the surface of the skull at a 10° angle to the vertical. Coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 1998) for placements to target a-VTA were −4.8 mm posterior to bregma, +2.1 mm lateral to the midline, and −8.5 mm ventral from the surface of the skull at a 10° angle to the vertical. A 28-gauge stylet was placed into the guide cannula and extended 0.5 mm beyond the tip of the guide. After surgery, rats were individually housed and allowed to recover for 7 days in their home cages. Animals were handled for at least 5 min daily beginning on the fourth recovery day and were habituated for 2 consecutive days to the handling procedures necessary for microinjections.

For the SACC experiment, stereotaxic implantation into p-VTA was performed on the first day of the ninth week. On the day after surgery, rats were returned to the operant chambers. After seven consecutive operant sessions after surgery, all rats were habituated to the handling procedures necessary for microinjections before placement in operant chambers.

Pavlovian Spontaneous Recovery Test.

The PSR sessions were identical to the extinction protocol conditions. The FR5–FR1 schedule, lever contingencies, and dipper functioning were maintained, but EtOH and water were absent. Rats were given four consecutive PSR test sessions, because previous studies have shown that adult P rats PSR start to return to baseline by the second session compared with periadolescence that show a more prolonged PSR (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b; Rodd et al., 2006).

Experiment 1: Microinjection of Quinpirole into the Posterior VTA.

Rats (n = 6–7/group) were microinjected bilaterally with vehicle (aCSF-control) or Quin (0.1 or 0.3 μg) as described previously (Nowak et al., 2000). In addition, bilateral microinjections of 1.0 μg of Quin into the VTA did not alter sucrose responding (Hodge et al., 1993) or prevent the acquisition of the behaviors associated with conditioned fear (de Oliveira et al., 2009). The current series of experiments did not use doses of Quin higher than 0.3 μg; therefore, any effects cannot be assigned to suppression of behaviors. Quin was administered consecutively to both sides of the p-VTA through 28-gauge injectors inserted bilaterally to a depth of 1 mm beyond the end of the guide cannulae connected to a Hamilton 10-μl syringe driven by a microinfusion syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Inc., Holliston, MA). A total volume of 0.5 μl was administered over a 30-s period per side; the injector tip was left in place for an additional 30 s per side. Quin was given 2 min before only the first 60-min PSR session.

Although diffusion is a concern in all microinjection studies, previous studies using the current microinfusion technique demonstrated that Quin microinjections 2 mm dorsal to the VTA did not change either EtOH or saccharin drinking behavior, which suggested that the actions of Quin were the result of activating receptors within the VTA and not caused by diffusion along the outside of the guide cannula (Nowak et al., 2000).

Experiment 2: Microinjection of EtOH into the Posterior VTA.

Rats (n = 7–8/group) were microinjected bilaterally with vehicle (aCSF) or EtOH (50 or 100 mg%). Doses of EtOH were selected based on previous research that shows P rats will self-administer 50 to 200 mg% EtOH into the p-VTA (Gatto et al., 1994; Rodd et al., 2004b). EtOH was administered using the electrolytic microinfusion transducer system (Rodd et al., 2004b). This procedure was used to administer EtOH because this technique was successfully used in self-infusion and microinjection experiments to determine behavioral and physiological responses of EtOH (Rodd et al., 2000, 2004b,c; Ding et al., 2009). EtOH was administered consecutively to both sides of the p-VTA for 10 min/side using three 5-s pulses/min; each 5-s pulse infused 100 nl. The microinjections were given before only the first 60-min PSR session starting approximately 20 min before the session.

The use of the electrolytic microinfusion transducer system has been shown to give relatively good neuroanatomical specificity. Previous studies with GABAA receptor antagonists or D1/D2 receptor agonists (Ikemoto et al., 1997a,b), cocaine (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a), and EtOH (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000a) demonstrated that diffusion away from the injection site did not seem to contribute to the reinforcing effects attributed to the target site.

Experiment 3: Microinjection of Quinpirole and EtOH into the Posterior VTA.

Rats (n = 5–6/group) were microinjected bilaterally with Quin (0.01, 0.03, 0.1, or 0.3 μg) following the same procedure as described in experiment 1. Immediately after Quin infusion, rats were microinjected bilaterally with EtOH (100 mg%), using the same procedure as described in experiment 2. The microinjections were given before only the first 60-min PSR session starting approximately 20 min before the session.

Experiment 4: Microinjection of Quinpirole into the Anterior VTA.

The same procedure for experiment 1 was used for the microinjections of Quin into the a-VTA. Rats (n = 7/group) were microinjected bilaterally with vehicle (aCSF-control) or Quin (0.1 or 0.3 μg). The microinjections were given before only the first 60-min PSR session starting approximately 2 min before the session.

Experiment 5: Microinjection of EtOH into the Anterior VTA.

The same procedure for experiment 2 was used for the microinjection of EtOH into the a-VTA. Rats (n = 7/group) were microinjected bilaterally with vehicle (aCSF) or EtOH (100 mg%). The microinjections were given before only the first 60-min PSR session starting approximately 20 min before the session.

Experiment 6: Microinjection of Quinpirole into the Posterior VTA on Saccharin Responding During Maintenance.

The same procedure for experiment 1 was used for the microinjections of Quin into the p-VTA. Rats (n = 5–7/group) were microinjected bilaterally with vehicle (aCSF-control) or Quin (0.3 μg). On the 11th consecutive operant session after surgery, microinjections were given before only the first 60-min SACC maintenance test session starting approximately 2 min before the session.

Histology.

At the termination of the experiment, 1% bromophenol blue (0.5 μl) was injected into the infusion site. Subsequently, the animals were given a fatal dose of Nembutal and then decapitated. Brains were removed and immediately frozen at −70°C. Frozen brains were subsequently equilibrated at −15°C in a cryostat microtome and then sliced into 40-μm sections. Sections then were stained with cresyl violet and examined under a light microscope for verification of the injection site using the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998).

Statistical Analysis.

Overall operant responding (60 min) data were analyzed with a mixed-factorial ANOVA with a between-subject factor of dose and a repeated measure of session. For the PSR experiments, the baseline measure for the factor of session was the average number of responses on the EtOH lever for the last three extinction sessions. Post hoc Tukey's B test was performed to determine individual differences. All analyses that were p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Histology Placements.

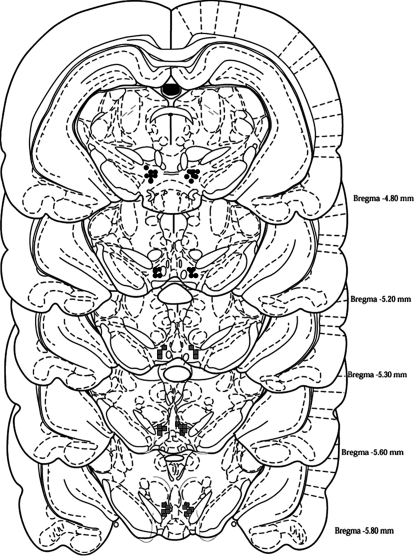

The p-VTA is defined as the VTA region at the level of the interpeduncular nucleus at 5.3 to 6.3 mm posterior to bregma (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000). In the current study, only animals that had correct injector placements were used in data analysis. As seen in Fig 1, the a-VTA injector placements were at 4.8 to 5.2 mm posterior to bregma, and the p-VTA injector placements were at 5.3 to 5.8 mm posterior to bregma. The success rate for correct a-VTA placements was 90%, and for p-VTA placements the success rate was 80%. The incorrect injections sites were located in substantia nigra or red nucleus. Those cannula placements that were found outside the VTA were excluded from analysis. Microinjections of EtOH into these areas did not have any effect on EtOH-seeking behavior, which is line with previous studies that show animals will not self-administer EtOH in these areas (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000; Rodd et al., 2004).

Fig. 1.

Representative placements for the microinfusions of aCSF, EtOH, or Quin into the a-VTA or p-VTA of adult female P rats are shown. Black circles represent placements of injection sites within the a-VTA (defined as −4.8 to −5.2 mm bregma), and gray squares represent placements of injection sites within the p-VTA (defined as −5.3 to −5.8 mm bregma).

Effects of Quinpirole Microinjection into the Posterior VTA on Responding in the PSR Test.

Examining the number of responses on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH (Fig. 2A) indicated a significant effect of session (F4,13 = 7.9; p = 0.002), dose (F2,16 = 6.7; p = 0.008), and session by dose interaction (F8,28 = 3.4; p = 0.007). The interaction term was decomposed by holding session constant. Therefore, individual ANOVAs were performed for each PSR session with the between-group variable of dose. There was only a significant effect of dose during the first PSR test session (F2,16 = 62.1; p < 0.0001). Post hoc comparisons (Tukey's B test) indicated that during the first PSR session aCSF-treated rats responded more than the groups administered 0.1 or 0.3 μg of Quin. Baseline level of responding was compared with responding during PSR testing within each group (t tests).

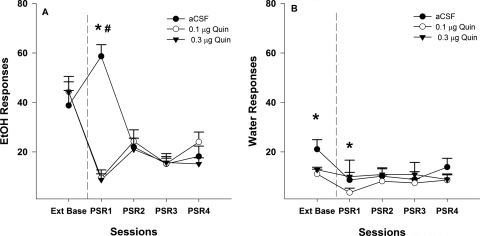

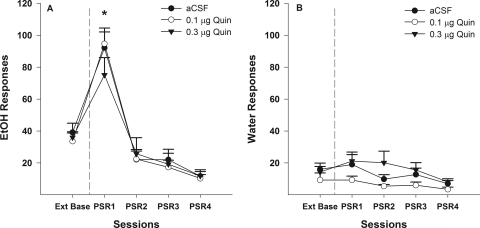

Fig. 2.

A, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH in P rats (n = 6–7/group) microinjected with aCSF or 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin into the p-VTA before only the first PSR session. * indicates that rats administered aCSF responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline levels, whereas rats administered 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin responded significantly less than extinction baseline. # indicates that both doses of Quin reduced EtOH responding during the first PSR session compared with the aCSF group (p < 0.05). B, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of water in P rats (n = 6–7/group) microinjected with aCSF and 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin into the p-VTA before only the first PSR sessions. * indicates that rats administered aCSF or 0.1 μg/0.5 μl of Quin responded significantly less on the water lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline. There were no significant differences among the three groups with regard to responses on the water lever during PSR session 1.

In P rats treated with aCSF, there was a significant increase in responding on the EtOH lever during the initial PSR session compared with extinction baseline (p = 0.04). There was significant decrease in responding on the EtOH lever below extinction baseline levels in rats administered 0.1 or 0.3 μg of Quin (p = 0.002). Responses on the EtOH lever were very similar for all three groups during PSR sessions 2 to 4.

Baseline extinction responding on the lever previously associated with water was significantly higher in the aCSF group compared with extinction baseline values for the Quin groups (p = 0.026). In addition, there was a significant decrease in water responding for the initial PSR session for the aCSF compared with extinction baseline values (Fig. 2B). The reduction that was observed for the aCSF group may be caused by the significantly higher extinction baseline for this group and may not be caused by aCSF affecting water responding. There was a significant decrease in water responding for the initial PSR session for the 0.1-μg Quin groups compared with extinction baseline values (Fig. 2B); however, there was no significant difference between extinction baseline and the initial PSR session for the group given a higher dose of Quin (0.3 μg) (p > 0.69). Moreover, there were no significant differences on water lever responses between groups given aCSF, 0.1 μg Quin, and 0.3 μg Quin during the initial PSR sessions (p > 0.50). Responses on the water lever during sessions 2 to 4 were similar for all three groups.

Effects of Microinjecting EtOH into the Posterior VTA on Responding in the PSR Test.

Examining the number of responses on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH (Fig. 3A) indicated a significant effect of session (F4,16 = 42.01; p < 0.001) and session by dose interaction (F8,34 = 4.68; p = 0.010). Decomposing the interaction term by holding the session constant allowed for ANOVAs to be performed on each session. During the first PSR session there was a significant effect of dose (F2,19 = 7.91; p = 0.003). Post hoc comparisons indicated that P rats administered 50 or 100 mg% EtOH directly into the p-VTA responded more than P rats administered aCSF during the first PSR test session. Within-group comparisons (t tests) performed indicated that all groups of rats responded more on the EtOH lever during the first PSR test session compared with those observed during extinction responding. Responses on the EtOH lever during sessions 2 to 4 were similar for all three groups.

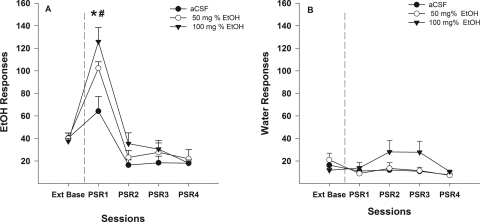

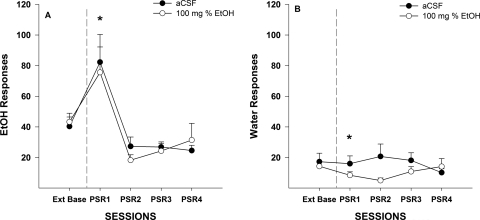

Fig. 3.

A, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH in P rats (n = 7–8/group) microinjected with aCSF or 50 or 100 mg% EtOH into the p-VTA before only the first PSR session. * indicates that rats administered aCSF or 50 or 100 mg% EtOH responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline levels. # indicates that rats administered 50 or 100 mg% EtOH responded significantly more during the first PSR session than rats administered aCSF (p < 0.05). B, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of water in P rats (n = 7–8/group) microinjected with aCSF or 50 or 100 mg% EtOH into the p-VTA before only the first PSR session. There were no significant differences.

The analysis performed on the responses on the lever previously associated with the delivery of water indicated that responding on this lever was low (less than 15–30 responses per session) and did not differ from baseline (p > 0.40) across PSR test sessions. There were also no differences between dose groups during the initial PSR sessions (p > 0.70).

Effects of Coadministration of Quin and EtOH into the Posterior VTA on Lever Responses in the PSR Test.

Examining the number of responses on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH (Fig. 4A) indicated a significant effect of session (F4,14 = 25.19; p < 0.001) and session by treatment interaction (F12,48 = 2.24; p = 0.024). Individual ANOVAs performed for each session indicated a significant effect of dose during the first PSR test session (F = 35.15; p < 0.0001). Post hoc comparisons indicated that P rats administered 100 mg% EtOH and 0.01 or 0.03 μg of Quin responded more than P rats administered 100 mg% EtOH and 0.1 and 0.3 μg of Quin directly into the p-VTA. P rats administered 100 mg% EtOH and 0.01 or 0.03 μg of Quin directly into the p-VTA responded more during the first PSR test session than during the last three sessions of extinction training (p < 0.016). In contrast, administration of 100 mg% EtOH and 0.1 and 0.3 μg of Quin directly into the p-VTA reduced the number of EtOH lever responses during the first PSR test session compared with extinction baseline (p < 0.009).

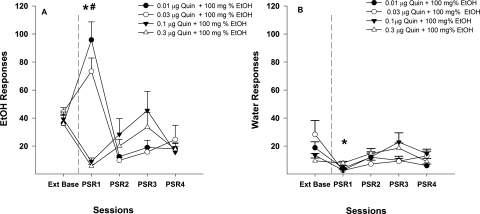

Fig. 4.

A, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH in P rats (n = 5/group) microinjected with 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin plus 100 mg% EtOH into the p-VTA before only the first PSR session. * indicates that rats administered 0.01 or 0.03 μg/0.5 μl plus 100 mg% responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline levels, whereas rats administered 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl Quin plus 100 mg% EtOH responded significantly less than extinction baseline. # indicates that rats administered 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin plus 100 mg% EtOH responded significantly less during the first PSR session than rats administered 0.01or 0.03 μg/0.5 μl of Quin plus EtOH (p < 0.05). B, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of water in P rats (n = 5/ group) microinjected with 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, or 0.3 μg/5 μl of Quin plus 100 mg% EtOH into the p-VTA before only the first PSR sessions. * indicates that rats administered 0.01 or 0.1 μg/0.5 μl of Quin plus 100 mg% EtOH responded significantly (p < 0.05) less on the water lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline. There were no significant differences among any of the groups in the first PSR session with regard to responses on the water lever.

Compared with extinction baseline values, responding on the lever previously associated with water was significantly decreased during the initial PSR testing for rats administered 0.01 μg of Quin with 100 mg% EtOH (p = 0.038) and 0.1 μg of Quin with 100 mg% EtOH (p = 0.018; see Fig. 4B). However, there were no significant differences on water lever responding for 0.03 μg of Quin with 100 mg% EtOH (p = 0.053) and 0.3 μg of Quin with 100 mg% EtOH (p = 0.407; see Fig. 4B). In addition, there were no significant differences between dose groups during PSR session 1 (p > 0.05).

Effects of Quinpirole Microinjection into the Anterior VTA on Responding in the PSR Test.

Examining the number of responses on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH (Fig. 5A) indicated a significant effect of session (F4, 15 = 54.8.11; p = 0.000). However, the session by dose interaction was not significant (F8, 28 = 0.289; p = 0.964). Baseline level of responding was compared with responding during PSR testing within each group (t tests).

Fig. 5.

A, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH in P rats (n = 7/group) microinjected with aCSF or 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin into the a-VTA before only the first PSR session. * indicates that rats administered aCSF and 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline levels. B, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of water in P rats (n = 7/group) microinjected with aCSF and 0.1 or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin into the a-VTA before only the first PSR sessions. There were no significant differences.

In P rats treated with aCSF and 0.1 and 0.3 μg of Quin there was a significant increase in responding on the EtOH lever during the initial PSR session compared with extinction baseline (p = 0.006, 0.002, and 0.019, respectively). There were no significant differences in EtOH responding between the aCSF and 0.1 and 0.3 μg of Quin during the initial PSR test session. Responses on the EtOH lever were also very similar for all three groups during PSR sessions 2 to 4.

Baseline extinction responding on the lever previously associated with water was not significantly different for any group (p ≥ 0.26). In addition, there were no significant differences between dose groups during the initial PSR sessions (p = 0.24). Responses on the water lever during sessions 2 to 4 were similar for all three groups.

Effects of Microinjecting EtOH into the Anterior VTA on Responding in the PSR Test.

Examining the number of responses on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH (Fig. 6A) indicated a significant effect of session (F4,9 = 6.595; p < 0.009). The session by dose interaction was not significant (F4,9 = 1.226; p = 0.365). Baseline level of responding was compared with responding during PSR testing within each group (t tests). In P rats treated with aCSF and 100 mg% EtOH, there was a significant increase in responding on the EtOH lever during the initial PSR session compared with extinction baseline (p = 0.014 and 0.029, respectively). There were no significant differences on EtOH responding between the aCSF and 100 mg% EtOH during the initial PSR (p = 0.79). Responses on EtOH lever were also very similar for all three groups during PSR sessions 2 to 4.

Fig. 6.

A, Mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of EtOH in P rats (n = 7/group) microinjected with aCSF or 100 mg% EtOH into the a-VTA before only the first PSR session. * indicates that rats administered aCSF and 100 mg% EtOH responded significantly (p < 0.05) more on the EtOH lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline levels. B, mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever previously associated with the delivery of water in P rats (n = 7/group) microinjected with aCSF or 100 mg% EtOH into the a-VTA before only the first PSR sessions. *, rats administered 100 mg% EtOH responded significantly (p < 0.05) less on the water lever during the first PSR session compared with extinction baseline levels. There were no significant differences among any of the groups in the first PSR session with regard to responses on the water lever.

Compared with extinction baseline values, responding on the lever previously associated with water was significantly decreased during the initial PSR testing for rats administered 100 mg% EtOH (p = 0.025; see Fig. 6B). However, there were no significant differences between dose groups during the initial PSR sessions (p >0.05).

Effects of Quinpirole Microinjection into the Posterior VTA on Saccharin Responding During Maintenance.

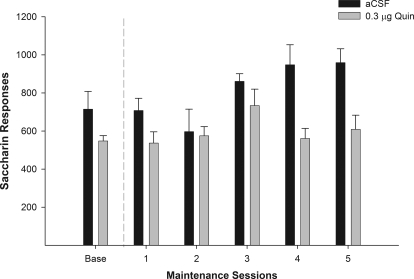

As a control we examine the effects of Quin microinjected into the p-VTA on SACC responding. Examining the number of responses on the lever associated with the delivery of SACC (Fig. 7) indicated that there was no significant effect of session (F5,6 = 1.80; p = 0.251) and there was no significant session by dose interaction (F5,6 = 0.754; p = 0.613). Baseline level of responding was compared with responding during maintenance testing within each group (t tests). In P rats treated with aCSF or 0.3 μg of Quin, there was no significant difference in responding on the SACC lever during the initial maintenance test session compared with baseline (p = 0.948 and 0.891, respectively). Responses on the SACC lever were also very similar for all groups during maintenance test sessions 2 to 5.

Fig. 7.

Mean (±S.E.M.) responses per session on the lever associated with the delivery of SACC in P rats (n = 5–7/group) microinjected with aCSF or 0.3 μg/0.5 μl of Quin into the p-VTA before only the first maintenance test session. There were no significant differences.

Baseline responding on the lever associated with water was not significantly different for any group compared with water lever responding during maintenance testing (p ≥ 0.113; data not shown). The average number of responses on the water lever was ≤15.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are that local EtOH microinfusions into the p-VTA, and not the a-VTA, increased responding on the EtOH lever during the PSR test (Fig. 3A), whereas local infusions of Quin into the same site reduced responding on the EtOH lever (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the p-VTA is a neuroanatomical site mediating EtOH-seeking behavior and that the activation of local DA neurons may be involved.

Electrophysiological studies have shown that local application of a D2 receptor agonist can decrease firing rates of the VTA by activating D2 cell body autoreceptors, whereas D2 receptor antagonists will increase the firing rates of DA neurons in the VTA (Wang 1981; White and Wang 1984; Robertson et al., 1991). In addition, local applications of a D2 receptor agonist can reduce extracellular concentrations of DA in the VTA and the nucleus accumbens (Kalivas and Duffy, 1991), whereas the infusion of a D2 receptor antagonist into the VTA can enhance the release of DA in the nucleus accumbens (Westerink et al., 1996). The coinfusion of a D2 receptor agonist with EtOH can prevent the acquisition and extinguish the maintenance of EtOH self-infusion into the p-VTA (Rodd et al., 2004c, 2005c), whereas sulpiride, a D2 receptor antagonist, reinstated EtOH self-administration into p-VTA (Rodd et al., 2004c). The results of these studies, together with the present findings (Figs. 2 and 3), suggest that VTA DA neuronal activity is needed for the expression of EtOH-seeking behavior.

In the present study, the PSR paradigm was used, which measures the relative strength of reinforcer-seeking behavior (i.e., possibly reflecting “alcohol craving”) to assess EtOH-seeking behavior. The present findings showed that microinfusion of Quin into the p-VTA can inhibit responding on the EtOH lever in the PSR test (Fig. 2A) and also inhibit the local EtOH-stimulated responding in the PSR test (Fig. 4A). In contrast, microinfusion of Quin into the a-VTA did not have any effect on responding on the EtOH lever in the PSR test (Fig. 5A). The doses of Quin administered in the current study were similar to doses used by Hodge et al. (1993), who reported that even the highest dose of Quin (10 μg/0.5 μl) infused into the VTA did not impair motor activity. Our previous research demonstrated that microinjections of 2 to 4 μg of Quin into p-VTA or 2 to 6 μg of Quin into a-VTA did not alter motor activity in female P rats (Nowak et al., 2000). The results of the present study also indicated that Quin did not reduce motor activity when infused into the p-VTA or a-VTA, because the highest dose of Quin did not alter responding on the water lever and responses on the water lever after Quin infusions were similar to aCSF infusions (Figs. 2B and 5B, respectively). As a control we examined the effects of Quin on SACC maintenance. The results revealed that the highest dose of Quin (0.3 μg) did not alter responses on SACC lever (Fig. 7). This is in line with Hodge et al. (1993), who reported that bilaterally microinjection of Quin as high as 1.0 μg into the VTA did not significantly reduce sucrose self-administration. Collectively, these results indicate that Quin's effects in the p-VTA on EtOH responding are not caused by a nonspecific inhibition on lever pressing.

The results of microinfusing EtOH alone into the p-VTA also provide support that the activation of local DA neurons is involved in mediating expression of EtOH-seeking behavior (Fig. 3A). There is evidence suggesting that EtOH can activate VTA DA neurons. Gessa et al. (1985), using single-cell recordings, demonstrated that EtOH can enhance the dopaminergic neurotransmission by increasing the firing rate of DA neurons in vivo. EtOH excitation of DA neurons was also observed in vitro for both extracellular and intracellular single-unit studies in brain slices (Brodie et al., 1990; Brodie and Appel 1998). Moreover, Brodie et al. (1999) provided evidence, using an acutely dissociated cell model, that the dopaminergic VTA neurons can be directly excited by EtOH. Another study (Ding et al., 2009) indicated that direct microinjections of EtOH into the p-VTA increases DA release in the nucleus accumbens shell. Overall, these results support the idea that EtOH can stimulate VTA DA neurons.

Compared with the vehicle group, a single microinfusion of 50 or 100 mg% of EtOH significantly increased responding on the EtOH lever during the initial PSR session (1.6- and 2.0-fold higher, respectively). These results are in agreement with previous studies that demonstrated that oral EtOH priming significantly enhanced responding on the EtOH lever compared with control responding in the PSR test (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b). The EtOH concentrations administered in the present study were in range with previous EtOH self-infusions into the p-VTA (Gatto et al., 1994; Rodd et al., 2004b). Likewise, blood EtOH levels attained under free-choice drinking conditions have been reported to be 50 to 200 mg% for P rats (Murphy et al., 1986). Therefore, the doses of EtOH used in the present study were within relevant pharmacological concentrations. Moreover, the enhanced EtOH responses did not seem to be a result solely of general locomotor activity because the animals were able to discriminate between the EtOH and the water levers.

Intracranial self-administration studies have indicated that the p-VTA is involved in mediating reinforcing properties of EtOH by activation of the dopaminergic systems (Rodd et al., 2000, 2004b,c, 2005c). The neuroadaptations that occur after chronic drinking and repeated alcohol deprivations seem to produce further increases in the reinforcing effects and the sensitivity of EtOH within the p-VTA (Rodd et al., 2005a,b). Furthermore, it is thought that drugs of abuse can prime responding by activating the mesolimbic DA system, which has become sensitized upon repeated drug use in a long-lasting manner (Robinson and Berridge 1993). Thus, our findings seem to suggest that local EtOH activation produces a priming effect in the p-VTA, but not the a-VTA, that promotes EtOH-seeking behavior (Figs. 3A and 6A) by activating the DA neurons. It is noteworthy that studies have observed selective abnormalities in the P rats' DA system projecting from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens (McBride et al., 1993) and increased VTA DA burst firing rates (Morzorati, 1998), suggesting that abnormalities underlying the high EtOH drinking behavior of the P line may reside within the VTA (Morzorati, 1998). Hence, further alterations of this system after chronic drinking and abstinence may also contribute to the enhancement of EtOH-seeking behavior observed in these animals.

It is noteworthy that there are several neuroanatomical differences between the p-VTA and a-VTA. For example, there are more DA neurons in the p-VTA than a-VTA projecting to the nucleus accumbens (Olson et al., 2005), there is a higher proportion of DA to GABA neurons in the p-VTA than a-VTA (Olson et al., 2005), and p-VTA has higher serotonin innervations (Hervé et al., 1987). Lastly, the VTA containing DA neurons with topographical afferent and efferent projections may also differ between the anterior and posterior sites (Kalen et al., 1988; Brog et al., 1993; Tan et al., 1995). Collectively, these studies provide evidence that DA activity may be greater in the p-VTA than in a-VTA.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that the p-VTA may be a neuroanatomical site mediating EtOH-seeking behavior in P rats and that activation of DA neurons is involved in this process. Therefore, the development of pharmacotherapeutics to reduce alcohol craving should include a profile that regulates the activity of p-VTA DA neurons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tylene Pommer and Victoria McQueen for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [Grants AA07462 AA07611, AA10721, AA12262].

The preliminary findings of this article have been presented previously: Hauser SR, Ding ZM, Getachew B, Dhaher R, Toalston JE, Oster SM, McQueen VK, McBride WJ, and Rodd ZA (2008) Involvement of the posterior ventral tegmental area (p-VTA) in mediating alcohol-seeking behavior in alcohol-preferring (P) rats, at the Research Society on Alcoholism 2008 Annual Meeting; 2008 June 29-July 2; Washington, DC. Research Society on Alcoholism, Austin, TX. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (2008) 32(Suppl):166A.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.110.168260.

Abbreviations:

- EtOH

- ethanol

- VTA

- ventral tegmental area

- p-VTA

- posterior VTA

- a-VTA

- anterior VTA

- Quin

- quinpirole

- PSR

- Pavlovian spontaneous recovery

- DA

- dopamine

- aCSF

- artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- SACC

- saccharin

- P rats

- alcohol-preferring rats

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- FR

- fixed ratio.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Hauser, Ding, McBride, and Rodd.

Conducted experiments: Hauser, Ding, Getachew, Toalston, Oster, and Rodd.

Performed data analysis: Hauser and Rodd.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Hauser and McBride.

Other: McBride and Rodd acquired funding for the research.

References

- Bouton ME. (2002) Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biol Psychiatry 52:976–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. (2004) Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learn Mem 11:485–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Appel SB. (1998) The effects of ethanol on dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area studied with intracellular recording in brain slices. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22:236–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Pesold C, Appel SB. (1999) Ethanol directly excites dopaminergic ventral tegmental area reward neurons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23:1848–1852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Shefner SA, Dunwiddie TV. (1990) Ethanol increases the firing rate of dopamine neurons of the rat ventral tegmental area in vitro. Brain Res 508: 65–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brog JS, Salyapongse A, Deutch AY, Zahm DS. (1993) The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J Comp Neurol 338:255–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DC. (2000) Recent and remote extinction cues reduce spontaneous recovery. Q J Exp Psychol B 153:25–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Sahuque LL, Janak PH. (2009) Ethanol seeking triggered by environmental context is attenuated by blocking dopamine D1 receptors in the nucleus accumbens core and shell in rats. Psychopharmacology 207:303–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas CV, Liu X, Simms JA, Weiss F. (2007) Distinct patterns of neural activation associated with ethanol seeking: effects of naltrexone. Biol Psychiatry 61:979–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira AR, Reimer AE, Brandão ML. (2009) Role of dopamine receptors in the ventral tegmental area in conditioned fear. Behav Brain Res 199:271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding ZM, Rodd ZA, Engleman EA, McBride WJ. (2009) Sensitization of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons to the stimulating effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33:1571–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D, Li Z, Lê AD. (2006) Effects of environmental and pharmacological stressors on c-fos and corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA in rat brain: Relationship to the reinstatement of alcohol seeking. Neuroscience 138:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto GJ, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK. (1994) Ethanol self-infusion into the ventral tegmental area by alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol 11:557–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessa GL, Muntoni F, Collu M, Vargiu L, Mereu G. (1985) Low doses of ethanol activate dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res 348:201–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA, Shaham Y. (2001) Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature 412:141–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervé D, Pickel VM, Joh TH, Beaudet A. (1987) Serotonin axon terminals in the ventral tegmental area of the rat: fine structure and synaptic input to dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res 435:71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Haraguchi M, Erickson H, Samson HH. (1993) Ventral tegmental microinjections of quinpirole decrease ethanol and sucrose-reinforced responding. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 17:370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Kohl RR, McBride WJ. (1997a) GABAA receptor blockade in the anterior ventral tegmental area increase extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats. J Neurochem 69:137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. (1997b) Self-infusion of GABAA receptor antagonists directly into the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions. Behav Neurosci 111:369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalén P, Skagerberg G, Lindvall O. (1988) Projections from the ventral tegmental area and mesencephalic raphe to the dorsal raphe nucleus in the rat. Exp Brain Res 73:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Duffy P. (1991) A comparison of axonal and somatodendritic dopamine release using in vivo dialysis. J Neurochem 56:961–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. (2000) Animal models of craving for ethanol. Addiction 95(Suppl 2):S73–S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Weiss F. (2002) Reversal of ethanol-seeking behavior by D1 and D2 antagonists in an animal model of relapse: differences in antagonist potency in previously ethanol-dependent versus nondependent rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300:882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Wang X, Wu P, Xu C, Zhao M, Morales M, Harvey BK, Hoffer BJ, Shaham Y.(2009) Role of ventral tegmental area glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in incubation of cocaine craving. Biol Psychiatry 66:137–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh JJ. (1977) Stimulus control: attentional factors, in Handbook on Operant Behavior (Honig WK, Staddon JER. eds) pp 162–241, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ [Google Scholar]

- McBride WJ, Chernet E, Dyr W, Lumeng L, Li TK. (1993) Densities of dopamine D2 receptors are reduced in CNS regions of alcohol-preferring P rats. Alcohol 10:387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinzie DL, Nowak KL, Yorger L, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK. (1998) The alcohol deprivation effect in the alcohol-preferring P rat under free-drinking and operant access conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22:1170–1176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morzorati SL. (1998) VTA dopamine neuron activity distinguishes alcohol-preferring (P) rats from Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22:854–857 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Gatto GJ, Waller MB, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. (1986) Effects of scheduled access on ethanol intake by the alcohol-preferring (P) line of rats. Alcohol 3:331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak KL, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM. (2000) Involvement of dopamine D2 autoreceptors in the ventral tegmental area on alcohol and saccharin intake of the alcohol-preferring P rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:476–483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson VG, Zabetian CP, Bolanos CA, Edwards S, Barrot M, Eisch AJ, Hughes T, Self DW, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. (2005) Regulation of drug reward by cAMP response element-binding protein: evidence for two functionally distinct subregions of the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci 25:5553–5562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. (1998) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 4th ed, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. (2001) Experimental extinction, in Handbook of Contemporary Learning Theories (Mowrer RR, Klein SB. eds), pp 119–154, Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SJ. (1990) Mechanisms underlying spontaneous recovery in authoshaping. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Processes 16:235–249 [Google Scholar]

- Robertson GS, Damsma G, Fibiger HC. (1991) Characterization of dopamine release in the substantia nigra by in vivo microdialysis in freely moving rats. J Neurosci 11:2209–2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. (1993) The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 18:247–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, McQueen VK, Davids MR, Hsu CC, Murphy JM, Li TK, Lumeng L, McBride WJ. (2005a) Chronic ethanol drinking by alcohol-preferring rats increases the sensitivity of the posterior ventral tegmental area to the reinforcing effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:358–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, McQueen VK, Davids MR, Hsu CC, Murphy JM, Li TK, Lumeng L, McBride WJ. (2005b) Prolonged increase in the sensitivity of the posterior ventral tegmental area to the reinforcing effects of ethanol following repeated exposure to cycles of ethanol access and deprivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 315:648–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Melendez RI, Kuc KA, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. (2004a) Comparison of intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the posterior ventral tegmental area between alcohol-preferring and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:1212–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Sable HJ, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. (2004b) Recent advances in animal models of alcohol craving and relapse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 79:439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Zhang Y, Murphy JM, Goldstein A, Zaffaroni A, Li TK, McBride WJ. (2005c) Regional heterogeneity for the intracranial self-administration of ethanol and acetaldehyde within the ventral tegmental area of alcohol-preferring (P) rats: involvement of dopamine and serotonin. Neuropsychopharmacology 30:330–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, McKinzie DL, Bell RL, McQueen VK, Murphy JM, Schoepp DD, McBride WJ. (2006) The metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist LY404039 reduces alcohol-seeking but not alcohol self-administration in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Behav Brain Res 171:207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Melendez RI, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Zhang Y, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. (2004c) Intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the ventral tegmental area of male Wistar rats: evidence for involvement of dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 24:1050–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. (2002a) Effects of ethanol exposure on subsequent acquisition and extinction of ethanol self-administration and expression of alcohol-seeking behavior in adult alcohol-preferring (P) rats: I. Periadolescent exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:1632–1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. (2002b) Effects of ethanol exposure on subsequent acquisition and extinction of ethanol self-administration and expression of alcohol-seeking behavior in adult alcohol-preferring (P) rats: II. Adult exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:1642–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, McKinzie DL, Crile RS, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. (2000) Regional heterogeneity for the intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the ventral tegmental area of female Wistar rats. Psychopharmacology 149:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Chappell AM. (2004) Effects of raclopride in the core of the nucleus accumbens on ethanol seeking and consumption: the use of extinction trials to measure seeking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:544–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R. (2003) Alcohol addiction research: from animal models to clinics. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 17:507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y, Brog JS, Williams ES, Zahm DS. (1995) Morphometric analysis of ventral mesencephalic neurons retrogradely labeled with Fluoro-Gold following injections in the shell, core, and rostral pole of the rat nucleus accumbens. Brain Res 689:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengeliene V, Leonardi-Essmann F, Perreau-Lenz S, Gebicke-Haerter P, Drescher K, Gross G, Spanagel R. (2006) The dopamine D3 receptor plays an essential role in alcohol-seeking and relapse. FASEB J 20:2223–2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RY. (1981) Dopaminergic neurons in the rat ventral tegmental area. II. Evidence for autoregulation. Brain Res Rev 3:141–151 [Google Scholar]

- Westerink BH, Kwint HF, deVries JB. (1996) The pharmacology of mesolimbic dopamine neurons: a dual-probe microdialysis study in the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens of the rat brain. J Neurosci 16:2605–2611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FJ, Wang RY. (1984) Pharmacological characterization of dopamine autoreceptors in the rat ventral tegmental area: microiontophoretic studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 231:275–280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]