Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) is the only potentially curative therapy for many patients with high risk or recurrent acute lymphoblastic (ALL) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The success of the procedure is now understood to be due in large part to a graft versus leukemia (GVL) effect mediated by donor immune cells.1–7 However, leukemia recurs following HCT in many patients and strategies to augment the GVL effect to prevent and treat leukemic relapse continue to be a focus of research. Immune effector cells that have been implicated in the GVL response include CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, each of which may contribute more or less to the GVL effect depending on the type of HCT. After T cell depleted haploidentical HCT, donor NK cells can mediate a potent GVL effect against AML in the small subset of recipients that do not express donor class I human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules required to engage donor NK-inhibitory receptors.8–12 After haploidentical HCT in which small numbers of donor T cells are administered to the patient, T cells that recognize major HLA differences participate in the GVL effect.13 In allogeneic HLA-identical HCT either from related or unrelated donors, the GVL effect is thought to be mediated primarily by T cells that recognize recipient minor histocompatibilty (H) antigens, which are distinct HLA binding peptides encoded by polymorphic genes that differ between the donor and recipient. Specifically, an HLA-matched individual who is homozygous for the minor H antigen ‘negative’ allele may have T cells in their repertoire that recognize recipient cells that are homozygous or heterozygous for a polymorphism that encodes a minor H antigen. A key feature of minor H antigen recognition is that the tissue expression of the antigen(s) determine whether the alloreactive T cell responses that develop after HCT cause graft versus host disease (GVHD), in which cells in the skin, gastrointestinal tract and other tissues are targeted, a GVL effect, or both. This review will focus on recent developments in T cell recognition of human minor H antigens, and efforts to translate these discoveries to reduce leukemia relapse after allogeneic HCT.

The Basis for Immunogenicity of Minor H Antigens

Minor H antigens are by definition non-self peptides, therefore the donor T cell repertoire is not subject to tolerance mechanisms that limit self-reactivity and as a result the T cell responses that are elicited to these determinants are typically of high avidity (Figure 1).2–7 Most commonly, immunogenicity originates from one or more nucleotide polymorphisms in the coding sequences of homologous donor and recipient genes that alter peptide-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) binding and/or T cell receptor (TCR) recognition of the peptide-MHC complex. There are at least 90,000 non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the human genome,14 providing a potentially large number of minor H antigens, based on minor alterations in protein sequence. Copy number variation, specifically homozygous gene deletion of a member of a polymorphic gene family (UGT2B17) in the donor, has also been shown to result in T cell recognition of peptides derived from this protein in recipient cells that express one or both copies of the gene.15–18 For the majority of minor H antigens, only unidirectional recognition has been demonstrated, either because the corresponding donor peptide is not generated15, 19 or transported by the antigen processing machinery,20–21 does not bind stably to MHC molecules,22–25 or is not recognized by T cells 22–23, 26–27 (Table 1).

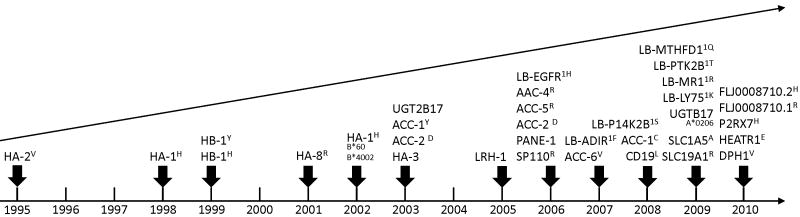

Figure 1.

The cartoon illustrates the pathways of generation and presentation of minor H antigens, and the recognition of minor H antigens by donor T cells during allogeneic HCT. Minor H antigens arise as a consequence of the normal cellular mechanisms for processing and presenting foreign antigens to T cells. Polymorphic genes are transcribed and translated and short peptide sequences are generated by proteolytic digestion of longer precursors in the proteosome. The peptides are transported into the endoplasmic reticulum by the peptide transporter (TAP) and loaded onto MHC class I molecules. The peptide-MHC complex is subsequently presented on the cell surface. In the setting of allogeneic HCT, polymorphisms in the recipient genome can result in the expression of proteins and peptides that are distinct from those in donor cells. Donor T cells fail to recognize self-peptides presented on the cell surface of donor cells due to thymic and peripheral tolerance mechanisms. However, there are high avidity T cells in the donor repertoire that can recognize recipient minor H antigens and these cells become activated following allogenic HCT and contribute to GVHD and to the GVL effect.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of immunogenicity of human minor histocompatibility antigens

| Minor H Antigen (gene) | HLA allele | Immunogenic Peptide Epitope | Genetic mechanisms | Molecular mechanisms preventing recognition of the alternative allelic peptide | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altered peptide binding to MHC and/or TCR | Altered peptide binding to MHC | AAC-4R (Cathepsin H) 200625 | A*3101 | ATLPLLCAR | exonic nsSNP | Δ peptide MHC binding |

| AAC-5R (Cathepsin H) 200625 | A*3303 | WATLPLLCAR | exonic nsSNP | Δ peptide MHC binding | ||

| HA-2V (MYO1G) 199528–29 | A*201 | YIGEVLVSV | exonic nsSNP | Δ peptide-MHC binding (+possible additional factors) | ||

| Altered TCR recognition of MHC-peptide complex | HA-1H (HMHA1) 199822 200730 |

A*0201 A*0206 |

VLHDDLLEA | exonic nsSNP | Δ peptide- MHC binding Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex |

|

| HA-1H (HMHA1) 200231 | B*60 B*40012 |

KECVLHDDL(L) | exonic nsSNP | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| # HB-1H (HMHB1) 199932–33 | B*4402 B*4403 |

EEKRGSLHVW | exonic nsSNP | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| # HB-1Y (HMHB1) 199934 | B*4402 B*4403 |

EEKRGSLYVW | exonic nsSNP | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| # ACC-1Y (BCL2A1) 200335 | A*2402 | DYLQYVLQI | exonic nsSNP | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| ACC-2D (BCL2A1) 200335 | B*4403 | KEFEDDIINW | exonic nsSNP | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| # ACC-1C (BCL2A1) 200836 | A*2402 | DYLQCVLQI | exonic nsSNP | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| LB-ECGF1-1H (ECGF1) 200626 | B*0702 | RPHAIRRPLAL | exonic nsSNP in alternative ORF | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| SP110R (SP110) 200637 | A*0301 | SLPRGTSTPK | exonic nsSNP | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex, reverse splicing non contiguous peptides | ||

| LB-ADIR-1F (ADIR/TOR3A) 200727 | A*0201 | SVAPALALFPA | exonic nsSNP in alternative ORF | Δ T cell recognition of MHC-peptide complex | ||

| Altered protein transport and/or processing | Altered transport in TAP | HA-8R (KIAA0020) 200120 | A*0201 | RTLDKVLEV | exonic nsSNP | Δ peptide transport TAP leading to absent peptide presentation in donor cells |

| Proteosomal cleavage | HA-3 (Lbc/AKAP13) 200321 | A*0101 | VTEPGTAQY | exonic nsSNP | proteosomal cleavage leading to precursor peptide destruction | |

| Unknown | SLC1A5A 200916 | B*4002 | AEATANGGLAL | exonic nsSNP | possible Δ TAP transport | |

| Altered transcription | Gene deletion | UGT2B17 200315, 17 | A*2902 B*4403 |

AELLNIPFLY | gene deletion | no transcribed sequence |

| UGTB17 200916 | A*0206 | CVATMIFMI | gene deletion | no transcribed sequence | ||

| Frame shift mutation | LRH-1 (P2X5) 200538–40 | B*0702 | TPNQRQNVC | frame-shift mutation | major difference in transcribed sequence | |

| Nonsense mutation | PANE1 (CENPM) 200619 | A*0301 |

RVWDLPGVLK termination |

nonsense mutation | Mutation related stop codon, transcription aborted, truncated transcript. | |

| mRNA splicing | ACC-6v (HMSD) 200741 | B*4402 B*4403 |

MEIFIEVFSHF HMSD variant |

intronic SNP | Δ mRNA splicing leads to a different transcript | |

Bi-allelic recognition has been demonstrated

Rationale for Targeting Lineage-Restricted Minor H Antigens Using T Cell Immunotherapy Following Allogeneic HCT

The potency of the GVL effect mediated by donor T cells is illustrated by analysis of outcome data after allogeneic HCT, which demonstrates a dramatically lower relapse rate in patients that develop acute and/or chronic GVHD.5 There is also a reduction in relapse in recipients of allogeneic HCT that do not develop GVHD compared to recipients of syngeneic HCT, suggesting that the GVL effect may be separated from GVHD. One strategy to accomplish this separation has been demonstrated in murine models in which leukemia was eradicated by the adoptive transfer of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) specific for a single recipient minor H antigen without GVHD.42 After allogeneic HCT in humans, both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells that recognize minor H antigens on recipient cells are activated in vivo and can be isolated in vitro, suggesting a similar approach to that taken in mice would be feasible in man. 7, 43–47 Human CD8+ minor H antigen-specific T cell clones have been demonstrated to lyse primary AML and ALL leukemic cells and inhibit the growth of AML colonies in vitro. Moreover, these T cells prevent the engraftment of AML in immunodeficient mouse models, demonstrating that the earliest leukemic progenitors are targets for minor H antigen-specific T cells.47–50 Unfortunately, most minor H antigen-specific T cells that have been isolated from patients and screened for recognition of cells derived from non-hematopoietic tissues also recognize at least some non-hematopoietic cells, raising concern that they would cause toxicity if adoptively transferred. A small subset of minor H antigens discovered are predominantly or exclusively on hematopoietic cells and several of these are being evaluated as targets for immunotherapy to facilitate a selective GVL effect (Table 2).43, 51–53 The potential for a few of these “hematopoietic restricted” minor H antigens described below to serve as targets for immunotherapy to augment the GVL effect is supported by analysis of T cell responses in patients that have responded to allogeneic HCT, or to a donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) to treat relapse.

Table 2.

Minor H antigens selectively expressed in hematopoietic cells

| Minor H Antigen | Gene/Chromosome | HLA allele | Polymorphism | Immunogenic Peptide Epitope | Genotype frequencies (%) | Estimated Disparity MSD (%) | Estimated Disparity MUD (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic | HA-1H 199822 200730 |

HMHA1/19p13.3 | A*0201 A*0206 |

rs1801284 | VLHDDLLEA | HH=13 HR=45.8 RR=41.2 | 6.4 +A*0206 < 1 |

11.6 +A*0206 <1 |

| LRH-1 200538 | P2X5/17p13.3 | B*0702 | rs5818907 | TPNQRQNVC | +/+ =4 +/− =50 −/− =46 | 4.9 | 7.5 | |

| ACC-2D 200335 | BCL2A1/15q24.3 | B*4403 | rs3826007 | KEFEDDIINW | DD=6.4 DG=38.1 GG=55.5 | 3.6 | 6.7 | |

| HEATR1E 201054 | HEATR1/1q43 | B*0801 | rs2275687 | ISKERAEAL | E/E= 10 E/G= 45 G/G= 45 | 3.1 | 5.6 | |

| ACC-1Y 200335 | BCL2A1/15q24.3 | A*2402 | rs1138357 | DYLQYVLQI | YY=6.7 YC= 39.5 CC=53.5 | 2.8 | 5.2 | |

| ACC-6v 200741 | HMSD/18q21.3 | B*4402 B*4403 |

rs9945924 |

MEIFIEVFSHF HMSD varient |

V/V=10 V/wt=23 wt/wt=66.7 | 2.3 | 5.9 | |

| HA-2V 199528–29 | MYO1G/7p13-p11.2 | A*0201 | rs61739531 | YIGEVLVSV | VV=56.8 VM=37.7 MM=5.5 | 1.8 | 2.5 | |

| SP110R 200637 | SP110/2q37.1 | A*0301 | rs1365776 | SLPRGTSTPK | RR=37.0 RG=48.3 GG=14.7 | 1.6 | 2.5 | |

| LB-LY75-1K 200955 | LY75/2q24 | DRB1 *1301 | rs12692566 | GITYRNKSLM | K/K=6.7 K/N =33 N/N=60 | 1.2 | 2.4 | |

| HA-1H 200231 | HMHA1/19p13.3 | B*60 B*40012 |

rs1801284 | KECVLHDDL(L) | HH=13 HR=45.8 RR=41.2 | <1 | <1 | |

| ACC-1C 200836 | BCL2A1/15q24.3 | A*2402 | rs1138357 | DYLQCVLQI | CC=53.8 YC=39.5 YY=6.7 | <1 | <1 | |

| B Cell | CD19L 200856 | CD19/16p11.2 | DQ A1*05 B1*02 |

rs2904880 | WEGEPPCLP | L/L=3.4 L/V=50 V/V=46.6 | 10.4 | 15.9 |

| HB-1Y 199934 | HMHB1/5q31.3 | B*4402 B*4403 |

rs161557 | EEKRGSLYVW | YY=5.2 HY=41.2 HH=53.7 | 3.9 | 6.8 | |

| HB-1H 199932–33 | HMHB1/5q32 | B*4402 B*4403 |

rs161557 | EEKRGSLHVW | HH=53.7 HY=41.2 YY=5.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

HA-1 and HA-2

HA-1 was the first molecularly characterized autosomal human minor H antigen and has been comprehensively investigated as a potential target for GVL therapy. HA-1 is a nonamer peptide (VLHDDLLEA, called HA-1H) that arises as a consequence of a SNP in the HMHA1 gene and is presented by HLA-A*0201. The corresponding non-immunogenic sequence, or ‘null allele’ is VLRDDLLEA, called HA-1R, and two groups have studied the basis for differential immunogenicity of these peptides in depth.22–24 The proteasomal cleavage and transport of the two peptides into the endoplasmic reticulum via TAP is similar, and both variants can bind to the HLA-restricting allele. However, the arginine (R) variant has lower affinity and less stable binding to HLA-A*0201 likely related to the relatively large size of the arginine molecule that results in steric and electrostatic hindrance with HLA-A*0201 D pocket residues.22–24 The interaction between soluble HA-1H-specific TCRs and the HA-1H and HA-1R peptides has also been analyzed, and it was observed that the TCR bound the HA-1H as expected, albeit with relatively low affinity (35 μM) and rapid dissociation, but completely failed to bind HA-1R.23 Thus, differences in both MHC and TCR binding account for the immunogenicity of HA-1H. The immunogenicity of HA-2 (sequence YIGEVLVSV, called HA-2V), which is also presented in association with HLA-A*0201, arises from a SNP in the MYOG1 gene that results in altered binding of the encoded peptides to HLA-A*0201. Like HA-1, HA-2 has a hematopoietic- restricted tissue distribution,52 although it has been less extensively studied than HA-1 and has a less favorable phenotypic distribution in the population.

It is well established that HA-1 and HA-2-specific CTL can kill leukemic blasts and prevent the growth of leukemic progenitors in vitro.48–49, 57–59 The first example of an in vivo effect of HA-1-specific T cells was reported by Kircher and colleagues, in which a patient with a chemotherapy refractory relapse of BCR-ABL positive ALL one year after HCT received a DLI from the original HLA-identical sibling HCT donor.57 The patient achieved a complete cytogenetic and molecular remission, and clonal analysis of the specificity of a minor H antigen-specific CTL line established from patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) revealed sole specificity for HLA-A2+ HA-1H+ target cells, and recognition of primary leukemic cells that endogenously presented the HA-1H minor H antigen. The Goulmy group performed an analysis of three additional patients who received DLI to treat post-transplant relapse using MHC/peptide tetramers to quantify HA-1 and/or HA-2 specific T cells.60–61 They observed an expansion of CD8+ T cells specific for HA-1 and/or HA-2 in the blood after DLI, and the emergence of HA-1 and HA-2 specific T cells coincided with remission of the malignancies (chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and multiple myeloma) and restoration of complete donor hematopoietic cell chimerism. HA-1 and HA-2-specific T cells were also isolated from these patients and shown to lyse recipient leukemic cells and inhibit leukemic colony formation in vitro.60–61 In one additional report, the emergence of HA-1H-specific CTL in patients treated with DLI for relapse of CML appeared to coincide with elimination of the CML.23

HA-1-specific CTL have been identified in PBMC samples obtained from patients who have received DLI without experiencing severe GVHD.30, 57, 60–61 However, analysis of transplant outcome based on donor/recipient disparity of HA-1 has provided conflicting data concerning a potential role of HA-1 in GVHD.62–64 This conflicting data could reflect the inherent limitations of analyzing GVHD outcomes in relation to a few known minor H antigen differences in population studies of highly outbred individuals. HA-1 is widely accepted to be selectively expressed on hematopoietic cells, and multiple publications have documented very low to absent HA-1 gene expression in non-hematopoietic cells,65–67 and lack of recognition of HA-1H positive non-hematopoietic cells by HA-1H-specific CTL in cellular assays.52 Furthermore, HA-1H-specific CTL induce little or no specific tissue damage when co-cultured with HA-1H positive skin biopsy specimens in a skin explant model of GVHD.68

BCL2A1/ACC-1 and ACC-2

BCL2A1 is a member of the bcl-2 family of anti-apoptotic genes and encodes the minor H antigens, ACC-1Y, ACC-1C and ACC-2D. Bi-allelic recognition of ACC-1 has recently been demonstrated such that both ACC-1Y (sequence DYLQYVLQI) and ACC-2C (DYLQCVLQI) are processed, bind the HLA-A*2402 restricting allele and are immunogenic.36 ACC-2D results from a different nucleotide polymorphism in the BCL2A1 gene and is presented by HLA-B*4403.35 The BCL2A1 gene is highly expressed in hematologic malignancies and may contribute to the survival of malignant cells, making minor H antigens encoded by this gene attractive for anti-leukemic immunotherapy.69 The immunogenicity of ACC-1Y, ACC-1C and ACC-2D have been attributed to physical differences in the peptide-MHC complex for TCR discrimination. ACC-1 Y and ACC-2D specific T cells were isolated from transplant recipients and lysed primary leukemic cells in vitro.35 Gene expression analysis by Northern blot,35 quantitative PCR,67 and database microarray data suggests a predominantly hematopoietic-restricted distribution (http://biogps.gnf.org) suggesting ACC-1Y, ACC-1C and ACC-2D may be useful targets for segregating the GVL effect from GVHD.70

P2X5/LRH-1

The P2X5 gene is a member of the P2X purinergic ATP-gated non-selective cation channels and encodes the HLA-B*0702-restricted LRH-1 minor H antigen.38 A frame shift mutation resulting from an insertion/deletion SNP underlies the immunogenicity of LRH-1. The cytosine deletion in exon 3 leads to the production of a truncated protein in the donor cells and a sequence disparity between the recipient and donor in the transcribed region, including a major partial disparity between recipient and donor for the amino acid sequence that gives rise to the minor H antigen peptide in recipient cells (TPNQRQNVC in the recipient, TPTSGRTSV in the donor).38 The fate of the donor transcript is not known.

Quantitative PCR data shows that P2X5 gene is expressed in normal lymphocytes, B and T lineage ALL, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, and the CD34+ fractions of CML and AML. P2X5 is expressed at lower levels in brain and skeletal muscle, but there is minimal if any expression in the target tissues of GVHD (small intestine, colon, liver, lung, skin),38 and skin fibroblasts that are positive by LRH-1genotyping, are not recognized in cellular assays.38 Although P2X5 is predominantly expressed on lymphocytes and there is little expression in normal myeloid cells, LRH-1-specific minor H antigens kill CD34+ ALL, AML, and CML cells, and CD138+ multiple myeloma cells in vitro.38–40 Dolstra’s group studied seven HLA-B7+ LRH-1+ positive patients who received HCT for a hematologic malignancy and subsequently DLI from a HLA-B7+ LRH-1−/− donor, and detected LRH-1-specific responses coinciding with clinical, molecular or cytogenetic responses in three of the seven patients. 38, 40

Progress in Development of Immunotherapy Targeting Minor H Antigens Following Allogeneic HCT

Despite the discovery of at least fourteen hematopoietic-restricted minor H antigens and observational data suggesting that certain minor H antigen-specific T cells may have the potential to induce a potent selective GVL effect, the translation of these discoveries into clinical trials that prospectively evaluate strategies such as adoptive T cell therapy or vaccination to augment specific T cell responses has been challenging. The challenges that have impeded clinical translation of minor H antigen-directed immunotherapy, and the progress in the field that provides optimism that the potential of this approach will be realized are described below.

Molecular identification of minor H antigens

The Challenges

A rational assumption for the clinical investigation of minor H antigen-directed immunotherapy has been that minor H antigens that have a predominantly hematopoietic-restricted tissue distribution should be selected as targets. Analysis of the genotype frequency of the minor H antigens shown in Table 2 reveals an inherent difficulty, which is that the current list will only be relevant for a minor proportion of the transplant population, and that any study targeting a single minor H antigen would have difficulty accruing sufficient number of patients to be informative. Ideally, a large panel of minor H antigens would be available from which to select appropriate targets for the treatment of individual HCT recipients because of the need to have the appropriate HLA restricting molecule and the correct directional disparity between HCT recipient and donor.

The success in assembling an adequate selection of minor H antigens for clinical immunotherapy trials is likely to depend on the stringency of the criteria used to define ‘hematopoietic-restricted’ since the proportion of human genes that are expressed absolutely exclusively in hematopoietic cells is very small. It is uncertain whether it is essential that the expression of minor H antigens be absolutely exclusive to hematopoietic cells to prevent toxicity in the context of adoptive immunotherapy or vaccination, or what level of expression in nonhematopoietic cells might be tolerated. However, this issue is difficult to approach experimentally, thus there remains a strong case for selecting highly hematopoietic-restricted minor H antigens as targets for the initial immunotherapy clinical trials until safety is established.

The Progress

At the present time, 25 and 40% of recipients of HLA-identical related and unrelated donor HCT respectively would be eligible for immunotherapy targeting one of the molecularly characterized minor H antigens expressed predominantly on hematopoietic cells (Table 2).71 The discovery of minor H antigens is accelerating as a result of novel approaches for isolating minor H antigen-specific CTL clones that can be used for gene discovery; and the development of databases of human genetic polymorphisms and cell lines with characterized genotypes that facilitate dissection of T cell recognition (Figure 2). How these developments are being applied to minor H antigen gene discovery is discussed briefly below.

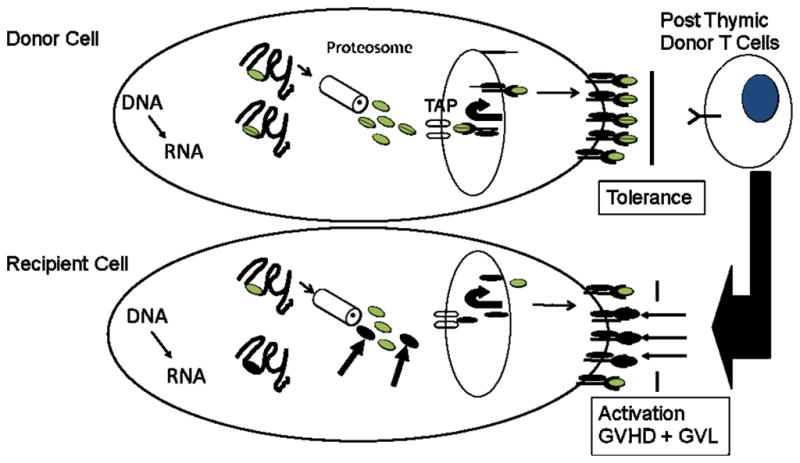

Figure 2.

The figure depicts the accelerating pace of minor H antigen discovery. Each year in which a molecularly characterized autosomal chromosome-associated human minor H antigen was discovered is marked on the horizontal time line by the vertical arrows. The name(s) of one or more minor H antigen identified in each discovery year is listed above the corresponding arrows.

a). Cellular tools: isolation of minor H antigen-specific CTL clones by primary in vitro stimulation

Minor H antigen-specific T cells provide essential reagents for the molecular identification and characterization of the polymorphic genes that encode the antigens, and such T cells have in the past been isolated from post-transplant blood obtained from allogeneic HCT recipients. This approach was cumbersome and often unsuccessful, perhaps due to the immunosuppressive drugs the patients were taking to impede the development of GVHD. We developed an approach for isolating minor H antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones that can be stably propagated for antigen discovery, that relies on the stimulation of naïve CD8+ T cells from unprimed donors with monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DC) from the HLA-identical sibling.54 The generation of minor H antigen-specific CTL by primary in vitro stimulation required IL-12 and gamma chain cytokines in the culture. With this approach, a large panel of CTL clones was obtained from granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilized stem cell products of ten consecutive HCT donors. This panel included CTL clones specific for novel minor H antigens that were presented in association with common HLA alleles, encoded by polymorphisms with a balanced phenotype frequency (between 26 and 78% of the population), and expressed on hematopoietic cells including leukemia.54 As proof of principle, a minor H antigen-specific CTL clone from this panel was used to discover a new minor H antigen encoded by the HEATR1 gene that is presented on AML stem cells and minimally in nonhematopoietic tissues.54 Additional minor H antigens have been identified using CTL clones derived by primary in vitro stimulation and these are currently being fully characterized.

b). Genetic and molecular tools: Genome wide association and advances in cDNA library screening

Approaches that have been used previously to identify the polymorphic genes and peptide sequences that provide minor H antigens include cDNA library screening, genetic linkage analysis, and peptide elution followed by high-performance liquid chromatography to identify immunogenic peptides and mass spectrometry to determine their sequence. These approaches have been reviewed elsewhere,7 but their broad application has been restricted to a few laboratories with the technical expertise to perform this work. The application of new genetic and molecular techniques that incorporate advances in human genomics reduces technical complexity and is accelerating the pace of minor H antigen discovery.

Genome wide association studies (GWAS) and HapMap screening

An important development in the field is the application of genome wide association studies (GWAS) and HapMap screening for minor H antigen identification. GWAS with HapMap scanning takes advantage of the publically available genotyping data from the Human Hap Map project and involves analyzing the relationship between patterns of expression of the minor H antigen phenotype (as determined by in vitro cytotoxicity or cytokine secretion assays) of B cell lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-LCL) and their patterns of SNP genotype downloaded from databases. In contrast to genetic linkage analysis, the association studies in GWAS are performed simultaneously for SNPs across the whole genome making it a potentially rapid and powerful technique. GWAS has now been used to discover three novel minor H antigens, and to retrospectively identify two others.16, 56, 72 The Akatsuka group published the first report of the use of GWAS for discovering novel minor H antigens.16 They screened minor H antigen-specific CTL clones for recognition of up to 72 HapMap B-LCL, and stratified the B-LCL into those that were clearly positive for expression of the minor H antigen and those that were clearly negative. Association scores were then calculated using the purpose designed computer program, and chromosomal regions that contained SNPs that were significantly associated with T cell recognition were identified. Candidate polymorphisms were then evaluated using synthetic peptides to identify the precise epitope. In one example reported by the Akatsuka group,16 the actual SNP that corresponded to the antigenic allele was not identified in the original GWAS because of genotyping errors for that SNP in the database, but was subsequently identified and confirmed on re-sequencing of the candidate gene. The GWAS approach is more rapid than traditional genetic linkage analysis and requires less technical expertise. However, there can be difficulties with the identification of multiple polymorphisms located in disparate regions, even different chromosomes, representing a mixture of false and true positive associations.16, 56, 72

Bacterial cDNA libraries for identification of class II MHC restricted minor H antigens

Most published work on minor H antigen discovery describes the identification of class I MHC-restricted minor H antigens recognized by CD8+ T cells. There has been renewed interest in a role for HLA class II minor H antigens in a selective GVL effect because HLA class II is not expressed on most non-hematopoietic tissues under non-inflammatory conditions, and therefore expression of a minor H antigen in non-hematopoietic tissue in the absence of its HLA restricting allele is less likely to cause GVHD. It remains to be determined whether there is sufficient HLA class II expression on leukemic cells, including leukemic stem cells to be recognized by CD4+ T cells, and if so whether leukemic cells will be susceptible to death pathways invoked in target cells by CD4+ T cells. These issues are best studied with T cells specific for molecularly characterized class II restricted minor H antigens.

Several class I MHC-restricted minor H antigens were discovered by screening cells co-transfected with pools of a cDNA library prepared from minor H antigen positive cells and with a plasmid encoding the class I MHC restricting allele. Conventional cDNA library screening by transfection into COS7 or 293T cells is not as easily applied for the discovery of class II minor H antigens, since these cells are not professional antigen presenting cells. This issue can be resolved by constructing the cDNA libraries such that the invariant chain is fused to each cDNA to direct the transport of translation products to class II processing compartments, and co-transfecting the COS cells with essential components of the class II antigen presentation pathway. 73 A subsequent improvement for discovery of class II restricted antigens relates to the expression of cDNA libraries in bacteria, and loading of bacteria containing the expressed human protein into class II MHC positive B-LCL.55, 74–75 The first example of the discovery of a minor H antigen using a bacterial cDNA library is the minor H antigen LB-P14K2B-1S encoded by the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type II β (PI4K2B) gene.75 A recombinant cDNA library was constructed from patient B-LCL by cloning randomly primed cDNAs into a pKE-1 vector, which encodes the glutathione-binding domain of GST under the control of a isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) promoter. Protein expression was induced by IPTG, and individual pools of 50 bacteria were then opsonized with complement and loaded onto aliquots of donor B-LCL. The B-LCL were then screened for T cell recognition by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay to detect interferon gamma. One bacterial pool induced a positive response and sub-cloning of this pool identified a single cDNA that was identical to the PI4K2B gene. A SNP in PI4K2B was subsequently confirmed to be the polymorphism relevant for recognition.

Several other autosomal minor H antigens have now been discovered using bacterial cDNA libraries including LB-LY75-1K, LB-MR1-1R, LB-PTK2B-1Y and LB-MTHFD1-1Q.55, 75 A minor H antigen of particular interest is LB-LY75-1K (sequence GITYRNKSLM), which is encoded by the lymphocyte antigen 75 (LY75) gene, and arises from a non-synonymous SNP (rs12692566, G/T, lysine/asparagine) in exon 29. LY75 is also known as DEC205 and functions as a scavenger receptor in DC.76,77 LY75 is expressed on both normal lymphoid and myeloid hematopoietic cells with the highest level of expression on DC. LB-LY75-1K positive AML cells but not fibroblasts (a representative non-hematopoietic cell) induced interferon gamma (IFNγ) release by the LB-LY75-1K-specific CD4+ T cell clone suggesting that targeting LB-LY75-1K could potentially induce a GVL effect without GVHD.55 One caveat for targeting LB-LY75-1K to induce a selective GVL effect is that it is also expressed on cortical thymic epithelial cells which, unlike most non-hematopoietic cells, do express HLA class II molecules.78 Thymic damage is considered to be a factor in the development of chronic GVHD by allowing thymocytes to escape deletion of T cells with self-reactive TCRs. Cortical thymic epithelial cells (EC) contribute to tolerance, thus the elimination of recipient thymic EC by targeting LY-75 could theoretically contribute to chronic GVHD.

c). Revisiting old tools: screening candidate polymorphic peptides using reverse immunology

There has been renewed interest in using reverse immunology for minor H antigen discovery with the wealth of available data on human genetic polymorphism. Reverse immunology involves screening candidate peptides selected from the sequence of a gene product of interest often based on computer algorithms that predict binding to HLA molecules. This approach has the potential for high-throughput analysis and allows the selective analysis of peptides encoded by genes that are known to be preferentially expressed in hematopoietic cells. Reverse immunology has been used extensively to discover tumor associated antigens, and in the past has facilitated the identification of additional epitopes in genes such as HMHA-1, and HB-1 that encode minor H antigens previously discovered by ‘forward’ immunology.34 Reverse immunology has recently been used by the Ritz group to identify potentially immunogenic novel Y chromosome associated minor H antigens after HLA-identical transplant between sex mismatched individuals. A large panel of Y chromosome derived peptide sequences were screened for recognition by T cells obtained from short-term cultures of PBMC obtained from patients following allogeneic HCT using IFNγ release as a readout. T cell responses to a subset of the peptides were observed, although only a small number of patients responded to any given peptide. Studies demonstrating that these putative novel HY antigens are processed and presented by leukemic cells have not yet been reported.79

Our lab has performed an in silico analysis that incorporated gene expression and SNP databases, and peptide prediction algorithms to assemble a library of candidate minor H antigen peptides derived from genes that are predominantly expressed in hematopoietic cells. This library of peptides will enable screening for T cell responses that might develop in allogeneic HCT recipients who are appropriately discordant at the putative antigenic allele with the donor, and can be used for in vitro priming of T cell responses from the donor naïve T cell repertoire.

Adoptive T cell therapy targeting minor H antigens

The Challenges

The adoptive transfer of donor T cells specific for viral antigens is effective for preventing cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein Barr virus (EBV) disease after allogeneic HCT without causing GVHD,80–84 and the transfer of autologous tumor-reactive T cells has been employed successfully in a subset of patients with melanoma and EBV related malignancies.85–89 The molecular characterization of minor H antigens that are expressed by leukemic cells but not on non-hematopoietic tissues provides the opportunity to use adoptive transfer of minor H antigen-specific T cells to augment the GVL effect after HCT without GVHD. There are several significant challenges to be met before this complex approach can be routinely employed. These include the need to develop efficient methods for isolating and expanding rare donor T cells that are specific for relevant minor H antigens, to define the appropriate cells and conditions that promote persistence of transferred T cells in vivo, and to implement strategies to ensure that transferred T cells do not cause toxicity to normal tissues.

The Progress

Steady progress has been made in defining principles for isolating, expanding and re-infusing T cells to treat human infections and malignancy, 84, 90–91 including the use of gene transfer techniques to introduce TCR αβ genes and confer specificity for a target antigen, and to introduce genes that will enhance safety.92–93 Another important advance is the recognition that cell intrinsic qualities of effector T cells (TE) that are selected for adoptive transfer play a critical role in their ability to persist in vivo and establish long-lived memory responses. Here, we discuss how these advances are being applied to adoptive T cell therapy targeting minor H antigens.

a). Isolation and expansion of minor H antigen-specific T cells

Donor T cells specific for minor H antigens including hematopoietic-restricted antigens such as HA-1H, ACC-1Y and ACC-2D and LRH-1 are already amplified in some HCT recipients, 23, 30, 35, 38, 40, 47, 57, 60–61 although their ability to eliminate leukemia may be compromised by the administration of immunosuppressive drugs to prevent GVHD. Such T cells can be isolated post-transplant and expanded in vitro for adoptive transfer to magnify the endogenous response and potentially improve the GVL effect. T cell clones rather than polyclonal T cells are preferred for immunotherapy in the allogeneic HCT setting to avoid infusing other potentially alloreactive T cells, and to facilitate analysis of safety and efficacy. A phase I clinical trial of adoptive immunotherapy has been performed by our group in which T cell clones that were specific for minor H antigens that exhibited preferential expression on hematopoietic cells by in vitro assays were adoptively transferred to patients with leukemia relapse.94 Prior to infusion, the T cell clones were expanded to several billion cells using culture methods that employ antibodies to the CD3 signaling complex to activate T cells, ‘feeder’ cells to provide co-stimulation, and IL-2 to promote T cell proliferation and survival. This study demonstrated that generating minor H antigen-specific T cells for therapy was feasible in a significant subset of patients, and showed that the transferred T cells infiltrated the bone marrow and mediated antileukemic activity in vivo. However, some treated patients experienced reversible pulmonary toxicity at high T cell doses that was subsequently shown to reflect the unexpected expression of the targeted minor H antigen in pulmonary epithelial cells. This “on-target” toxicity emphasized the need to focus on immunotherapy targeting molecularly characterized minor H antigens with a well defined tissue distribution for future clinical trials.94 A second problem observed in this trial was the short duration of persistence of transferred T cells, which is commonly observed in adoptive T cell therapy trials for malignancy and correlates with lack of a sustained antitumor effect.95 The basis for poor T cell persistence is beginning to be elucidated and strategies to improve cell persistence are discussed later in this review.

An alternative approach is to isolate minor H antigen-specific T cells directly from the donor before transplant and administer them either as part of the stem cell graft or early post-transplant when the tumor burden is low. Early therapy may be especially important after non-myeloablative HCT because of the limited anti-tumor activity of the conditioning regimen. Specialized culture conditions employing DC that are either pulsed with immunogenic peptides, transfected with the gene encoding the antigen, or derived from monocytes isolated from the HCT recipient (and thereby naturally expressing the relevant minor H antigens) have been developed to isolate donor T cells specific for leukemia-associated minor H or non-polymorphic antigens.54, 96–99 Techniques have been established for the isolation of human T cell clones and involve plating T cells directly from polyclonal cultures at limiting dilution or after selection using tetramers or cytokine capture, and screening colonies to identify those with the desired reactivity.47, 100 Potential problems with this approach include the technical difficulty of priming and expanding rare T cells from the naïve repertoire of the donor, and the possibility that TE cells derived from naïve T cell precursors in vitro may not be appropriately programmed for survival in vivo.

b). TCR αβ gene transfer to derive T cells for adoptive immunotherapy

While culture conditions for the isolation of minor H antigen-specific T cells for GVL therapy have improved, novel strategies to generate T cells may prove more efficient and ultimately more effective. One potential approach is to engineer donor T cells for antigen specificity by the introduction of genes that encode the TCR α and β chains from previously isolated minor H antigen specific T cell clones. TCR gene transfer has been successful for generating antigen-specific T cells that are effective in murine models of adoptive immunotherapy,101–103 and the first human clinical trials of T cells modified by TCR gene transfer to treat metastatic melanoma have been performed with some success. 104–105

TCR gene transfer has the advantage of providing “off the shelf” reagents that could be used to target minor H antigens in HCT recipients that are appropriately discordant at specific loci. The availability of TCR genes for multiple minor H antigens would increase the applicability of minor H antigen-specific immunotherapy, requiring only that the donor and recipient be genotyped prior to transplant to select the appropriate targets for therapy. The TCRs would need to be inserted into donor T cells that lack the ability to cause GVHD, which could potentially be accomplished by introducing the genes into virus (CMV or EBV)-specific T cells. 103, 106–111 For example, the minor H antigen HA-2 has a favorable tissue distribution and CTL specific for HA-2 have been observed in patients with relapsed leukemia responding to DLI. However, 95% of the population expresses the antigenic HA-2v allele and therefore naturally mismatched recipient donor pairs are infrequent. The transfer of HA-2-specific TCRs into T cells from HLA-A*0201 positive, HA-2-negative individuals using retroviral vectors has been demonstrated to successfully redirect cytolytic activity against HA-2 positive target cells, including leukemia.103 Furthermore, the introduction of an HLA-A*0201-restricted HA-2-specific TCR into HLA-A*0201 negative lymphocytes also transferred HA-2-specific anti-leukemic reactivity in vitro, and only against HLA-A*0201 positive target cells.103 Thus, this approach could also be applied to T cell therapy in non-HLA matched HCT where the donor lacks the HLA restricting allele for a minor H antigen that both the donor and recipient share.

There are potential limitations of the TCR transfer approach including a) mispairing of the gene-transferred TCR and native TCR chains leading to the development of dysfunctional or potentially autoreactive TCRs, b) competition for the CD3 co-receptor between the gene-transferred TCR with the native TCR or mixed TCR dimers leading to reduced function of the introduced antigen-specific TCR, and c) inefficient gene transfer and unstable transgene expression. Potentially harmful neoreactivity, including HLA class I and II alloreactivity and autoreactivity, has been observed in human T cells in vitro as a consequence of mispairing of the gene-transferred minor H antigen or viral-specific TCR α or β chains and native TCR chains112, and a lethal GVHD syndrome (‘TCR gene transfer-induced GVHD’) has been observed in murine models as a result of mispairing of endogenous and introduced TCRs.113 Efforts to make TCR transfer safer include modifications of the introduced α and β chains to increase correct pairing,112, 114–117 and/or to prevent expression of the endogenous TCR by the introduction of a zinc finger nuclease specific for the endogenous TCR beta chain or the use of small interfering RNA (siRNA), thereby avoiding the opportunity for mispairing 118–119 A further option to prevent mispairing of the introduced and endogenous αβ chains is to introduce the αβ TCR genes together with the requisite CD4 and CD8 co-receptors into γ/δ T cells which lack endogenous αβ chains. The γ/δ T cell approach has been studied using the HA-2 minor H antigen TCR as a model and the HA-2 αβ transduced γ/δ T cells showed good functional activity in vitro.107, 120

c). Promoting persistence of adoptively transferred antigen-specific T cells

The optimal regimen for promoting persistence of transferred T cells in humans has not yet been defined. Several factors have been suggested to interfere with T cell persistence including terminal differentiation from prolonged culture of T cells before infusion, the use of excessive cytokines in vitro, and the absence of a CD4+ helper T cell response in vivo.81, 121 Strategies for improving in vivo survival of transferred T cells that have been evaluated in animal models include the addition of exogenous cytokines such as IL-2 or IL-15, or cytokine transduction of the CTL; co-stimulation via CD28 or 4-1BB; and transferring T cells when the recipient is lymphopenic and homeostatic regulatory mechanisms that promote T cell expansion and survival are invoked.85–86, 122–125 The use of IL-2 or IL-15 is likely to be difficult in the allogeneic HCT setting as these cytokines may provoke GVHD by inducing the proliferation of donor alloreactive T cells present in the stem cell graft.

The importance of heritable cell intrinsic qualities of transferred T cells is increasingly being recognized as a factor for the persistence of transferred T cells. T cells for adoptive transfer could be isolated from the naïve (TN CD45RA+ CD45RO− CD62L+), central memory (TCM CD45RO+ CD62L+), or the effector memory (TEM CD45RO+, CD62L−) T cell subsets.126 After in vitro activation and expansion, T cells acquire a uniform TE phenotype and lack most memory T cell markers.127 Studies in our lab in a non-human primate model have demonstrated that clonally derived TE cells obtained from TCM precursors have a greatly superior capacity to persist in vivo after adoptive transfer compared to those derived from TEM precursors, and reacquire memory markers, and respond to antigenic challenge in vivo.128 This finding is consistent with studies in murine models showing that TCM confer superior anti-tumor protection after adoptive transfer compared to TEM.129 These results suggest that the transfer of TCRs specific for minor H antigens to target leukemia would best be accomplished by purifying TCM cells with a native TCR specific for a persistent virus to facilitate their survival and function after adoptive transfer. A recent study performed in a transgenic mouse model suggests that TE cells derived from TN are also superior to those derived from TEM cells in their ability to persist in vivo after adoptive T cell transfer, providing they are not extensively cultured.130

d). Preventing toxicity associated with adoptive T cell transfer

The adoptive transfer of minor H antigen-specific T cells to augment the GVL effect has the potential to cause GVHD or toxicity to normal tissues that express the target antigen, as illustrated by the results of the first clinical trial of this approach.94 The use of gene transfer to engineer T cell specificity would impose an additional risk of insertional oncogenesis.131 If the therapy is effective in eliminating leukemia, some limited toxicity may be acceptable. However, it would be advantageous to be able to eliminate transferred T cells if serious toxicity developed. The introduction of a conditional suicide gene, such as the HSV thymidine kinase (TK) gene has been effective for controlling GVHD after polyclonal DLI to treat relapse or EBV lymphoproliferation in HCT recipients, but this approach can be limited by the immunogenicity of the viral TK, which can result in premature elimination of transferred effector cells.93, 132–134 Alternative suicide genes based on the expression of chimeric human proteins such as Fas or caspase 9 that can be activated by a synthetic nontoxic drug to induce cell death are being investigated by several groups.135–136 Another approach is to express a surface molecule such as CD20 that can be targeted by a monoclonal antibody. Preliminary studies indicate that virus (CMV)-specific T cells co-transduced with CD20 and the minor H antigen HA-2 TCR exhibit high level HLA-restricted cytotoxicity against HA-2+ targets in vitro and can be efficiently destroyed with the αCD20 mAb Rituximab by complement-dependent cytotoxicity.137 These developments suggest that more sophisticated approaches to augmenting GVL activity by the adoptive transfer of minor H antigen-specific T cells will be feasible in the future.

Future Directions -- Vaccination Against Minor H Antigens

Vaccination of HCT recipients against minor H antigens could represent an alternative approach to adoptive immunotherapy, or a complementary strategy for augmenting the GVL effect. However, despite considerable effort to elicit tumor-reactive T cell responses in cancer patients, most studies have yielded poor results. Additional challenges to priming or boosting immune responses in HCT recipients are posed by the pharmacologic immunosuppression that is administered to prevent or treat GVHD, and by the delayed immune reconstitution that occurs after HCT. Conversely, there are grounds for optimism about the potential of vaccines targeting minor H antigens to augment the GVL effect. In contrast to solid tumors, hematological malignancies may be more susceptible to vaccine-induced T cell responses because the tumor environment is more accessible physically and immunologically. Several clinical trials of peptide or DC vaccines targeting non-polymorphic leukemia-associated antigens have now been conducted and immunologic and clinical responses have been demonstrated.138–151 Minor H antigens are foreign to the donor T cells and therefore should have the potential to induce high affinity responses, in contrast to most non-polymorphic tumor-associated antigens.

Clinical trials of HA-1 or HA-2 vaccination of the transplant recipient to augment the GVL effect following allogeneic HCT have been initiated or are planned at several centers, but results have not yet been reported. Vaccination of the immune competent transplant donor prior to transplant is an intriguing alternative approach that could increase the frequency T cells specific for leukemia-associated antigens in the stem cell graft and facilitate the GVL effect. The feasibility of inducing immune responses with vaccination and transferring them with adoptive immunotherapy post-transplant in humans has been demonstrated in the autologous HCT setting,152 and transfer of vaccine induced T cell responses to a tumor antigen (idiotype) through the HCT graft has also been demonstrated in HCT between HLA-identical siblings.153 Donor vaccines targeting minor H antigens may pose a theoretical risk of inducing autoimmunity by virtue of cross-reactivity with the “non-immunogenic” allele. However, the observation that multiparous women remain healthy in spite of being primed to minor H antigens from the fetus suggests this is unlikely.154–155

Conclusions

It is now fifteen years since the first molecular characterization of human minor H antigens and significant strides in minor H antigen discovery are now being made as a consequence of advances in cellular, genetic and molecular techniques. Much has been learned about the mechanisms of minor H antigen immunogenicity, their expression on normal and malignant cells, and their role in GVL responses. As discussed in this review, the challenges in translating these findings to improve the outcome of allogeneic HCT have been substantial. The first report of the adoptive transfer of minor H antigen-specific T cell clones to patients with leukemia relapse in 2010 illustrates the potential for manipulation of alloreactivity for therapeutic benefit. Concurrent progress in defining the basic requirements for effective adoptive T cell immunotherapy, such as the transfer of T cell subsets with a high intrinsic capacity for prolonged survival and in the use of gene transfer to confer specificity promise to hasten the clinical translation of cellular therapeutics targeting minor H antigens.

References

- 1.Barnes DW, Corp MJ, Loutit JF, Neal FE. Treatment of murine leukaemia with X rays and homologous bone marrow; preliminary communication. Br Med J. 1956;2:626–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4993.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiden PL, Flournoy N, Thomas ED, Prentice R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, et al. Antileukemic effect of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of allogeneic-marrow grafts. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1068–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905103001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiden PL, Sullivan KM, Flournoy N, Storb R, Thomas ED. Antileukemic effect of chronic graft-versus-host disease: contribution to improved survival after allogeneic marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1529–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198106183042507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, Storb R, Witherspoon RP, Fefer A, Fisher L, et al. Influence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease on relapse and survival after bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical siblings as treatment of acute and chronic leukemia. Blood. 1989;73:1720–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, Goldman JM, Kersey J, Kolb HJ, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75:555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appelbaum FR. Haematopoietic cell transplantation as immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411:385–9. doi: 10.1038/35077251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleakley M, Riddell SR. Molecules and mechanisms of the graft-versus-leukaemia effect. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:371–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parham P, McQueen KL. Alloreactive killer cells: hindrance and help for haematopoietic transplants. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:108–22. doi: 10.1038/nri999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Burchielli E, Capanni M, Carotti A, Aloisi T, et al. NK cell alloreactivity and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Parkman, Robertson U19 CA100265/CA/NCI NIH HHS/United States Research Support, NIH, Extramural Review United States Blood cells, molecules & diseases. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008 Jan–Feb;40(1):91–3. Epub 2007 Sep 17. 2008;40:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velardi A, Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Aversa F, Christiansen FT. Natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation: a tool for immunotherapy of leukemia. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill S, Olson JA, Negrin RS. Natural killer cells in allogeneic transplantation: effect on engraftment, graft- versus-tumor, and graft-versus-host responses. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:765–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vago L, Perna SK, Zanussi M, Mazzi B, Barlassina C, Stanghellini MT, et al. Loss of mismatched HLA in leukemia after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:478–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0811036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan M, Diekhans M, Lien S, Liu Y, Karchin R. LS-SNP/PDB: annotated non-synonymous SNPs mapped to Protein Data Bank structures. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1431–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murata M, Warren EH, Riddell SR. A human minor histocompatibility antigen resulting from differential expression due to a gene deletion. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1279–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamei M, Nannya Y, Torikai H, Kawase T, Taura K, Inamoto Y, et al. HapMap scanning of novel human minor histocompatibility antigens. Blood. 2009;113:5041–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terakura S, Murata M, Warren EH, Sette A, Sidney J, Naoe T, et al. A single minor histocompatibility antigen encoded by UGT2B17 and presented by human leukocyte antigen-A*2902 and -B*4403. Transplantation. 2007;83:1242–8. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259931.72622.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarroll SA, Bradner JE, Turpeinen H, Volin L, Martin PJ, Chilewski SD, et al. Donor-recipient mismatch for common gene deletion polymorphisms in graft-versus-host disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1341–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brickner AG, Evans AM, Mito JK, Xuereb SM, Feng X, Nishida T, et al. The PANE1 gene encodes a novel human minor histocompatibility antigen that is selectively expressed in B-lymphoid cells and B-CLL. Blood. 2006;107:3779–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brickner AG, Warren EH, Caldwell JA, Akatsuka Y, Golovina TN, Zarling AL, et al. The immunogenicity of a new human minor histocompatibility antigen results from differential antigen processing. J Exp Med. 2001;193:195–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spierings E, Brickner AG, Caldwell JA, Zegveld S, Tatsis N, Blokland E, et al. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-3 arises from differential proteasome-mediated cleavage of the lymphoid blast crisis (Lbc) oncoprotein. Blood. 2003;102:621–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.den Haan JM, Meadows LM, Wang W, Pool J, Blokland E, Bishop TL, et al. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1: a diallelic gene with a single amino acid polymorphism. Science. 1998;279:1054–7. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholls S, Piper KP, Mohammed F, Dafforn TR, Tenzer S, Salim M, et al. Secondary anchor polymorphism in the HA-1 minor histocompatibility antigen critically affects MHC stability and TCR recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3889–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900411106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spierings E, Gras S, Reiser JB, Mommaas B, Almekinders M, Kester MG, et al. Steric hindrance and fast dissociation explain the lack of immunogenicity of the minor histocompatibility HA-1Arg Null allele. J Immunol. 2009;182:4809–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torikai H, Akatsuka Y, Miyazaki M, Tsujimura A, Yatabe Y, Kawase T, et al. The human cathepsin H gene encodes two novel minor histocompatibility antigen epitopes restricted by HLA-A*3101 and -A*3303. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:406–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slager EH, Honders MW, van der Meijden ED, van Luxemburg-Heijs SA, Kloosterboer FM, Kester MG, et al. Identification of the angiogenic endothelial-cell growth factor-1/thymidine phosphorylase as a potential target for immunotherapy of cancer. Blood. 2006;107:4954–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Bergen CA, Kester MG, Jedema I, Heemskerk MH, van Luxemburg-Heijs SA, Kloosterboer FM, et al. Multiple myeloma-reactive T cells recognize an activation-induced minor histocompatibility antigen encoded by the ATP-dependent interferon-responsive (ADIR) gene. Blood. 2007;109:4089–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-043935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.den Haan JM, Sherman NE, Blokland E, Huczko E, Koning F, Drijfhout JW, et al. Identification of a graft versus host disease-associated human minor histocompatibility antigen. Science. 1995;268:1476–80. doi: 10.1126/science.7539551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce RA, Field ED, Mutis T, Golovina TN, Von Kap-Herr C, Wilke M, et al. The HA-2 minor histocompatibility antigen is derived from a diallelic gene encoding a novel human class I myosin protein. J Immunol. 2001;167:3223–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torikai H, Akatsuka Y, Miyauchi H, Terakura S, Onizuka M, Tsujimura K, et al. The HLA-A*0201-restricted minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1H peptide can also be presented by another HLA-A2 subtype, A*0206. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:165–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mommaas B, Kamp J, Drijfhout JW, Beekman N, Ossendorp F, Van Veelen P, et al. Identification of a novel HLA-B60-restricted T cell epitope of the minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1 locus. J Immunol. 2002;169:3131–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolstra H, Fredrix H, Preijers F, Goulmy E, Figdor CG, de Witte TM, et al. Recognition of a B cell leukemia-associated minor histocompatibility antigen by CTL. J Immunol. 1997;158:560–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolstra H, Fredrix H, Maas F, Coulie PG, Brasseur F, Mensink E, et al. A human minor histocompatibility antigen specific for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Exp Med. 1999;189:301–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dolstra H, de Rijke B, Fredrix H, Balas A, Maas F, Scherpen F, et al. Bi-directional allelic recognition of the human minor histocompatibility antigen HB-1 by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2748–58. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2748::AID-IMMU2748>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akatsuka Y, Nishida T, Kondo E, Miyazaki M, Taji H, Iida H, et al. Identification of a polymorphic gene, BCL2A1, encoding two novel hematopoietic lineage-specific minor histocompatibility antigens. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1489–500. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawase T, Nannya Y, Torikai H, Yamamoto G, Onizuka M, Morishima S, et al. Identification of human minor histocompatibility antigens based on genetic association with highly parallel genotyping of pooled DNA. Blood. 2008;111:3286–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warren EH, Vigneron NJ, Gavin MA, Coulie PG, Stroobant V, Dalet A, et al. An antigen produced by splicing of noncontiguous peptides in the reverse order. Science. 2006;313:1444–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1130660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Rijke B, van Horssen-Zoetbrood A, Beekman JM, Otterud B, Maas F, Woestenenk R, et al. A frameshift polymorphism in P2X5 elicits an allogeneic cytotoxic T lymphocyte response associated with remission of chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3506–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI24832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overes IM, de Rijke B, van Horssen-Zoetbrood A, Fredrix H, de Graaf AO, Jansen JH, et al. Expression of P2X5 in lymphoid malignancies results in LRH-1-specific cytotoxic T-cell-mediated lysis. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:799–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norde WJ, Overes IM, Maas F, Fredrix H, Vos JC, Kester MG, et al. Myeloid leukemic progenitor cells can be specifically targeted by minor histocompatibility antigen LRH-1-reactive cytotoxic T cells. Blood. 2009;113:2312–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawase T, Akatsuka Y, Torikai H, Morishima S, Oka A, Tsujimura A, et al. Alternative splicing due to an intronic SNP in HMSD generates a novel minor histocompatibility antigen. Blood. 2007;110:1055–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fontaine P, Roy-Proulx G, Knafo L, Baron C, Roy DC, Perreault C. Adoptive transfer of minor histocompatibility antigen-specific T lymphocytes eradicates leukemia cells without causing graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:789–94. doi: 10.1038/89907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goulmy E, Gratama JW, Blokland E, Zwaan FE, van Rood JJ. A minor transplantation antigen detected by MHC-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes during graft-versus-host disease. Nature. 1983;302:159–61. doi: 10.1038/302159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Irle C, Beatty PG, Mickelson E, Thomas ED, Hansen JA. Alloreactive T cell responses between HLA-identical siblings. Detection of anti-minor histocompatibility T cell clones induced in vivo. Transplantation. 1985;40:329–33. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198509000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irle C, Chapuis B, Jeannet M, Kaestli M, Montandon N, Speck B. Detection of anti-non-MHC-directed T cell reactivity following in vivo priming after HLA-identical marrow transplantation and following in vitro priming in limiting dilution cultures. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:2674–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voogt PJ, Goulmy E, Veenhof WF, Hamilton M, Fibbe WE, Van Rood JJ, et al. Cellularly defined minor histocompatibility antigens are differentially expressed on human hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 1988;168:2337–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.6.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warren EH, Greenberg PD, Riddell SR. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-defined human minor histocompatibility antigens with a restricted tissue distribution. Blood. 1998;91:2197–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Falkenburg JH, Goselink HM, van der Harst D, van Luxemburg-Heijs SA, Kooy-Winkelaar YM, Faber LM, et al. Growth inhibition of clonogenic leukemic precursor cells by minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:27–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Harst D, Goulmy E, Falkenburg JH, Kooij-Winkelaar YM, van Luxemburg-Heijs SA, Goselink HM, et al. Recognition of minor histocompatibility antigens on lymphocytic and myeloid leukemic cells by cytotoxic T-cell clones. Blood. 1994;83:1060–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonnet D, Warren EH, Greenberg PD, Dick JE, Riddell SR. CD8+ minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones eliminate human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8639–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinsmoen NL, Kersey JH, Bach FH. Detection of HLA restricted anti-minor histocompatibility antigen(s) reactive cells from skin GVHD lesions. Hum Immunol. 1984;11:249–57. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(84)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Bueger M, Bakker A, Van Rood JJ, Van der Woude F, Goulmy E. Tissue distribution of human minor histocompatibility antigens. Ubiquitous versus restricted tissue distribution indicates heterogeneity among human cytotoxic T lymphocyte-defined non-MHC antigens. J Immunol. 1992;149:1788–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niederwieser D, Grassegger A, Aubock J, Herold M, Nachbaur D, Rosenmayr A, et al. Correlation of minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes with graft-versus-host disease status and analyses of tissue distribution of their target antigens. Blood. 1993;81:2200–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bleakley M, Otterud BE, Richardt JL, Mollerup AD, Hudecek M, Nishida T, et al. Leukemia-associated minor histocompatibility antigen discovery using T-cell clones isolated by in vitro stimulation of naive CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2010;115:4923–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-260539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stumpf AN, van der Meijden ED, van Bergen CA, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH, Griffioen M. Identification of 4 new HLA-DR-restricted minor histocompatibility antigens as hematopoietic targets in antitumor immunity. Blood. 2009;114:3684–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spaapen RM, Lokhorst HM, van den Oudenalder K, Otterud BE, Dolstra H, Leppert MF, et al. Toward targeting B cell cancers with CD4+ CTLs: identification of a CD19-encoded minor histocompatibility antigen using a novel genome-wide analysis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2863–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kircher B, Stevanovic S, Urbanek M, Mitterschiffthaler A, Rammensee HG, Grunewald K, et al. Induction of HA-1-specific cytotoxic T-cell clones parallels the therapeutic effect of donor lymphocyte infusion. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:935–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kircher B, Wolf M, Stevanovic S, Rammensee HG, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Gastl G, et al. Hematopoietic lineage-restricted minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1 in graft-versus-leukemia activity after donor lymphocyte infusion. J Immunother. 2004;27:156–60. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jedema I, van der Werff NM, Barge RM, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. New CFSE-based assay to determine susceptibility to lysis by cytotoxic T cells of leukemic precursor cells within a heterogeneous target cell population. Blood. 2004;103:2677–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marijt WA, Heemskerk MH, Kloosterboer FM, Goulmy E, Kester MG, van der Hoorn MA, et al. Hematopoiesis-restricted minor histocompatibility antigens HA-1- or HA-2-specific T cells can induce complete remissions of relapsed leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2742–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530192100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kloosterboer FM, van Luxemburg-Heijs SA, van Soest RA, Barbui AM, van Egmond HM, Strijbosch MP, et al. Direct cloning of leukemia-reactive T cells from patients treated with donor lymphocyte infusion shows a relative dominance of hematopoiesis-restricted minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1 and HA-2 specific T cells. Leukemia. 2004;18:798–808. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goulmy E, Schipper R, Pool J, Blokland E, Falkenburg JH, Vossen J, et al. Mismatches of minor histocompatibility antigens between HLA-identical donors and recipients and the development of graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:281–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mutis T, Gillespie G, Schrama E, Falkenburg JH, Moss P, Goulmy E. Tetrameric HLA class I-minor histocompatibility antigen peptide complexes demonstrate minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in patients with graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 1999;5:839–42. doi: 10.1038/10563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin MT, Gooley T, Hansen JA, Tseng LH, Martin EG, Singleton K, et al. Absence of statistically significant correlation between disparity for the minor histocompatibility antigen-HA-1 and outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:3172–3. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilke M, Dolstra H, Maas F, Pool J, Brouwer R, Falkenburg JH, et al. Quantification of the HA-1 gene product at the RNA level; relevance for immunotherapy of hematological malignancies. Hematol J. 2003;4:315–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujii N, Hiraki A, Ikeda K, Ohmura Y, Nozaki I, Shinagawa K, et al. Expression of minor histocompatibility antigen, HA-1, in solid tumor cells. Transplantation. 2002;73:1137–41. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200204150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torikai H, Akatsuka Y, Yatabe Y, Morishima Y, Kodera Y, Kuzushima K, et al. Aberrant expression of BCL2A1-restricted minor histocompatibility antigens in melanoma cells: application for allogeneic transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:467–73. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dickinson AM, Wang XN, Sviland L, Vyth-Dreese FA, Jackson GH, Schumacher TN, et al. In situ dissection of the graft-versus-host activities of cytotoxic T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Nat Med. 2002;8:410–4. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nagy B, Lundan T, Larramendy ML, Aalto Y, Zhu Y, Niini T, et al. Abnormal expression of apoptosis-related genes in haematological malignancies: overexpression of MYC is poor prognostic sign in mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:434–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nishida T, Akatsuka Y, Morishima Y, Hamajima N, Tsujimura K, Kuzushima K, et al. Clinical relevance of a newly identified HLA-A24-restricted minor histocompatibility antigen epitope derived from BCL2A1, ACC-1, in patients receiving HLA genotypically matched unrelated bone marrow transplant. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spierings E, Hendriks M, Absi L, Canossi A, Chhaya S, Crowley J, et al. Phenotype frequencies of autosomal minor histocompatibility antigens display significant differences among populations. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spaapen RM, de Kort RA, van den Oudenalder K, van Elk M, Bloem AC, Lokhorst HM, et al. Rapid identification of clinical relevant minor histocompatibility antigens via genome-wide zygosity-genotype correlation analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7137–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang RF, Wang X, Atwood AC, Topalian SL, Rosenberg SA. Cloning genes encoding MHC class II-restricted antigens: mutated CDC27 as a tumor antigen. Science. 1999;284:1351–4. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van de Corput L, Chaux P, van der Meijden ED, De Plaen E, Frederik Falkenburg JH, van der Bruggen P. A novel approach to identify antigens recognized by CD4 T cells using complement-opsonized bacteria expressing a cDNA library. Leukemia. 2005;19:279–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Griffioen M, van der Meijden ED, Slager EH, Honders MW, Rutten CE, van Luxemburg-Heijs SA, et al. Identification of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type II beta as HLA class II-restricted target in graft versus leukemia reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3837–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712250105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shrimpton RE, Butler M, Morel AS, Eren E, Hue SS, Ritter MA. CD205 (DEC-205): a recognition receptor for apoptotic and necrotic self. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1229–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang B, Kuroiwa JM, He LZ, Charalambous A, Keler T, Steinman RM. The human cancer antigen mesothelin is more efficiently presented to the mouse immune system when targeted to the DEC-205/CD205 receptor on dendritic cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1174:6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rouse RV, Parham P, Grumet FC, Weissman IL. Expression of HLA antigens by human thymic epithelial cells. Hum Immunol. 1982;5:21–34. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(82)90028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ofran Y, Kim HT, Brusic V, Blake L, Mandrell M, Wu CJ, et al. Diverse patterns of T-cell response against multiple newly identified human Y chromosome-encoded minor histocompatibility epitopes. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1642–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riddell SR, Watanabe KS, Goodrich JM, Li CR, Agha ME, Greenberg PD. Restoration of viral immunity in immunodeficient humans by the adoptive transfer of T cell clones. Science. 1992;257:238–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1352912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walter EA, Greenberg PD, Gilbert MJ, Finch RJ, Watanabe KS, Thomas ED, et al. Reconstitution of cellular immunity against cytomegalovirus in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow by transfer of T-cell clones from the donor. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1038–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heslop HE, Ng CY, Li C, Smith CA, Loftin SK, Krance RA, et al. Long-term restoration of immunity against Epstein-Barr virus infection by adoptive transfer of gene-modified virus-specific T lymphocytes. Nat Med. 1996;2:551–5. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leen AM, Myers GD, Sili U, Huls MH, Weiss H, Leung KS, et al. Monoculture-derived T lymphocytes specific for multiple viruses expand and produce clinically relevant effects in immunocompromised individuals. Nat Med. 2006;12:1160–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berger C, Turtle CJ, Jensen MC, Riddell SR. Adoptive transfer of virus-specific and tumor-specific T cell immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:224–32. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16168–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hunder NN, Wallen H, Cao J, Hendricks DW, Reilly JZ, Rodmyre R, et al. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with autologous CD4+ T cells against NY-ESO-1. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2698–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bollard CM, Aguilar L, Straathof KC, Gahn B, Huls MH, Rousseau A, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy for Epstein-Barr virus+ Hodgkin’s disease. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1623–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heslop HE, Slobod KS, Pule MA, Hale GA, Rousseau A, Smith CA, et al. Long-term outcome of EBV-specific T-cell infusions to prevent or treat EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease in transplant recipients. Blood. 2010;115:925–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.June CH. Principles of adoptive T cell cancer therapy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1204–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI31446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gattinoni L, Powell DJ, Jr, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:383–93. doi: 10.1038/nri1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]