Abstract

Purpose

To measure electric current in human corneal wounds and test the feasibility of pharmacologically enhancing the current to promote corneal wound healing.

Methods

Using a noninvasive vibrating probe, corneal electric current was measured before and after wounding of the epithelium of donated postmortem human corneas. The effects of drug aminophylline and chloride-free solution on wound current were also tested.

Results

Unwounded cornea had small outward currents (0.07 μA/cm2). Wounding increased the current more than 5 fold (0.41 μA/cm2). Monitoring the wound current over time showed that it seemed to be actively regulated and maintained above normal unwounded levels for at least 6 hours. The time course was similar to that previously measured in rat cornea. Drug treatment or chloride-free solution more than doubled the size of wound currents.

Conclusions

Electric current at human corneal wounds can be significantly increased with aminophylline or chloride-free solution. Because corneal wound current directly correlates with wound healing rate, our results suggest a role for chloride-free and/or aminophylline eyedrops to enhance healing of damaged cornea in patients with reduced wound healing such as the elderly or diabetic patient. This novel approach offers bioelectric stimulation without electrodes and can be readily tested in patients.

Keywords: cornea, epithelium, wound, healing, electric, current, field

Delayed and nonhealing wounds remain significant medical and economic problems.1–4 Despite extensive research, simple and effective approaches to augment wound healing are still not available. Electric signaling has recently emerged as a very powerful modality in epithelial wound healing in the laboratory setting.5–9 Experiments have suggested that electric signals are the major directional cues overriding other directional signals such as free edge, contact inhibition release, wound void, population pressure, and so on, that are the generally accepted directional cues for guiding cells into wounds. However, current approaches using electrodes to deliver electric stimulation to enhance wound healing have produced inconsistent results.10–13 The physical application of electrodes is associated with many uncontrollable factors, including (1) difficulties designing optimal electrode–tissue interface and minimizing toxic electrolyte formation, (2) heterogeneity in electric resistance of live tissue causing variation in field, (3) different types of cells that are supposed to undertake different jobs, experience the same global electric field. These are problems not easy to resolve using electrodes. Are there practical approaches to exploit electric signaling in wound healing without electrodes?

We explored and developed a novel approach to enhance endogenous wound electric fields pharmacologically and thus stimulate wound healing. We have previously demonstrated the efficacy of this in rat corneal wound healing.8,9,14 In the present report, we tested this approach in donor human corneas.

The corneal epithelium has multiple functions including transport of electrolytes, mechanical protection from pathogens, and refraction of incoming light. The active transport of electrolytes contributes to the control of corneal hydration.15–17 Significantly, and much less recognized, this electrolyte transport underlies the naturally occurring endogenous electric fields at corneal wounds.8,9,14 Analogous to the membrane potential of a cell, generated by directional transport of ions, the corneal epithelium generates a transepithelial potential difference (TEPD) of about 25–45 mV. This electrical potential is generated by the epithelium pumping chloride from the stroma out to the tears and sodium from the tears to the stroma. Tight junctions between the epithelial cells form a barrier of high electrical resistance, which maintains the TEPD. Wounding the corneal epithelium disrupts this barrier and short-circuits the TEPD locally at the wound. Positive potential under the surrounding intact epithelium drives ion currents into the wound producing endogenous wound electric currents and laterally oriented electric fields projecting from all around the wound into the wound center. Chiang et al18 measured average fields of 42 mV per millimeter close to wound edges in bovine cornea. Following on from this, Sta Iglesia and Vanable19 showed that endogenous electric fields in the vicinity of bovine corneal wounds are necessary for normal rates of wound epithelization. Decreasing field strengths retard epithelization, whereas healing can be enhanced at field strengths that are greater than normal.

Injury currents are not only present in cornea but are generated in many tissues. Large electric currents enter injured spinal cord,20 and skin wounds produce large and long-lasting electric fields.21,22 We have shown that electric currents are produced upon partial amputation of Xenopus tadpole tails and seem to influence tail regeneration.23 Electric fields are also important during embryo development and wound healing,24 and electric currents seem to influence ocular lens regeneration after surgery.25 The feasibility of using bioelectric stimulation to promote skin wound healing7 and spinal cord repair26 have also been studied. The links between electrical activity and wound healing have been reviewed recently by Zhao et al.27

Application of electric fields of physiological strength directs corneal epithelial cells and keratinocytes to migrate toward the cathode.28–30 This electric signal is so powerful that it can even drive cells at the wound edge to move away from the wound in a monolayer culture of corneal epithelial cells and organ-cultured corneas.8,9,31 Translating this discovery into the clinical field proves to be technically challenging. We therefore developed a novel approach—targeting the mechanisms by which the wound electric fields are generated. We achieved this by modulating ion transport by corneal epithelial cells chemically and pharmacologically. We have shown previously that placing rat corneas in chloride-free solution significantly enhanced corneal wound currents and that increasing or decreasing wound currents with pharmacological drugs that enhance or inhibit ion transport also increased or decreased wound healing, respectively.14

Extending this approach toward more clinical use, we employed donor human corneas and tested our hypothesis that endogenous currents generated at human corneal wounds can be significantly modulated chemically and pharmacologically. This forms a basis for future clinical studies to enhance corneal wound healing electrically without using electrodes.

Materials and Methods

Donor Corneas

Postmortem isolated human corneas deemed unsuitable for organ donation or transplantation were obtained from Sierra Eye & Tissue Donor Services, Sacramento, CA. All tissues were screened for human immunodeficiency virus, human T-lymphotropic virus, and hepatitis B and C, per standard eye banking protocol. They were transported in chilled Optisol corneal storage medium (Bausch & Lomb, Inc, Rochester, NY). Most corneas were 3 days postmortem. We found that corneas preserved up to 4 days had viable corneal epithelium, but by 5 days, the corneal epithelium had begun to slough, and measurable currents were not present.

Vibrating Probe Measurement

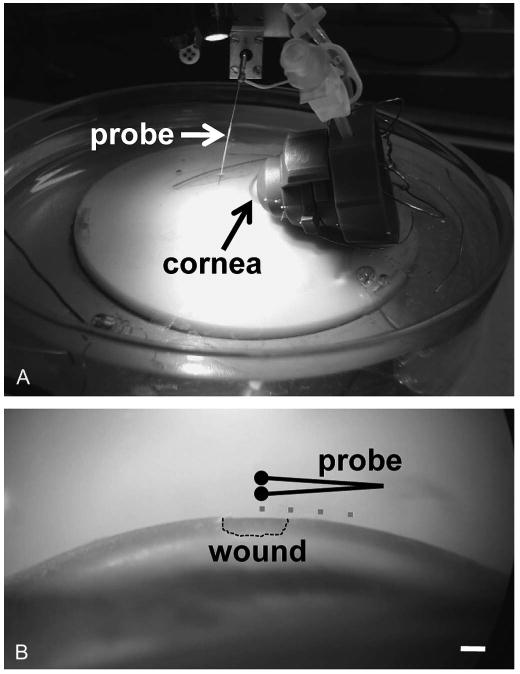

Corneas were mounted on a Barron artificial anterior chamber (Katena Products, Inc, Denville, NJ) in a custom-made dish (Fig. 1A). The solution inside the anterior chamber and in the dish was balanced salt solution enriched with bicarbonate, dextrose, and glutathione (BSS Plus Intraocular Irrigating Solution; Alcon Laboratories, Inc, Fort Worth, TX). For drug treatment, 10 mM aminophylline (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added to the BSS solution. Chloride-free solution contained (in millimolar): 2.96 Na2HPO4, 25 NaHCO3, 122.18 NaOH, 5.1 KOH, 1.05 Ca(NO3)2.4H2O, 0.98 MgSO4.7H2O, 0.3 glutathione disulphide, 131.34 methanesulfonic acid, and 5 glucose (Sigma-Aldrich). Vibrating probes were prepared and were used as described in detail previously.32 Briefly, the probe is an insulated stainless-steel needle with a platinum ball approximately 30 μm in diameter electroplated to the tip. The probe, mounted on a 3-dimensional micromanipulator, is vibrated in solution about 50 μm from the corneal surface by a piezoelectric bender at a set frequency. If an electric (ionic) current is present, the charge on the platinum ball oscillates in proportion to the size of the current and at the frequency of vibration. The probe is attached to a lock-in amplifier that locks onto the probe's frequency signal, filtering out all other “noise” frequencies. The probe is calibrated in a current density of 1.5 μA/cm2 at the start and end of experiments. Measurements were made at room temperature. Wounds were made as described previously14 by scraping away a rectangular portion of the corneal epithelium approximately 2 mm wide with a 15-degree ophthalmologic scalpel (Medical Sterile Products, Rincon, PR) (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Mounting and measuring from cornea. A, Cornea mounted in artificial anterior chamber for measurements with vibrating probe. B, Microscope view of wound on corneal surface. Dots show the different measuring positions which are plotted in Figure 2B. Scale bar, 1 mm.

Ion-selective Microelectrodes

The ion-selective probe system, kindly loaned by Ebenezer Yamoah (University of California Davis Department of Otolaryngology), was obtained from the Biocurrents Research Center (Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA). Borosilicate glass capillaries (TW150-4; World Precision Instruments) were heat pulled in a Sutter P-97 electrode puller. They were heated to 200°C and silanized with silanization solution I (Fluka). Electrodes were back filled with 100 mM NaCl and tip filled with a 50–100 μm length of chloride ionophore I coctail A (Fluka). Reference electrodes contained 2% agar in 100 mM NaCl. Electrodes were calibrated in standard solutions containing 10, 100, and 200 mM NaCl. For chloride ion flux measurement in human corneal epithelial (HCE) cell monolayer, the electrode was used in self-referencing mode, where the electrode moves between 2 points 30 μm apart at low frequency (0.3 Hz) near the wound edge.33 If a chloride flux is present, the electrode detects a difference in ion concentration. The electrode was controlled and data recorded using IonView32 software (Biocurrents Research Center).

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Differences between mean values were compared using a 2-sample Student t test, performed with equal or unequal variance according to an f test. In graphs, symbols * or # indicate significant difference (P < 0.05). All procedures were approved by the University of California Davis's Institutional Review Board (protocol number 200816682-1).

Results

First, to determine that the postmortem human corneas were still viable, we measured the corneal surface electrical activity before and after wounding. Unwounded cornea had a very small outward current (0.07 ± 0.04 μA/cm2; n = 14), whereas wounding the cornea produced a significantly larger outward current (wound edge, 0.41 ± 0.07 μA/cm2; n = 14) (Fig. 2A). The wound currents were relatively small compared with about 4 μA/cm2 in rat cornea (Reid et al,14 2005) probably because these human corneas were approximately 3 days postmortem. As we observed previously in rat cornea, maximum current was seen at the wound edge (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Wound currents. A, Wounding cornea induces significantly increased outward currents (n = 14; *P < 0.002). B, Current is maximal at wound edge, dropping significantly outside wound (#P < 0.004).

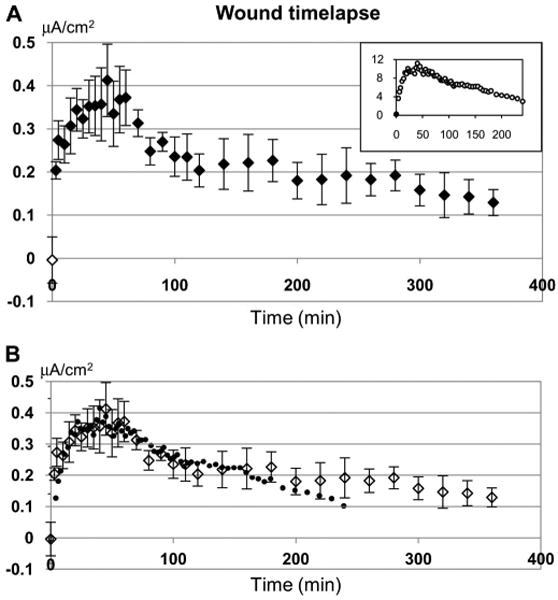

To characterize the dynamic changes of wound current over time, we measured the wound edge current for several hours after wounding. Currents before wounding were very small (−0.004 ± 0.05 μA/cm2; n = 3). After wounding, the current showed a pattern of change very similar to that observed in fresh rat cornea (Fig. 3A). After wounding, the current rose rapidly, leveled off after about 30 minutes, then began to decline slowly after about 60 minutes. Only 3 minutes after wounding, the current had increased 50 fold to 0.2 ± 0.02 μA/cm2 (P < 0.02). The current continued to increase until 30 minutes, peaking at 0.41 ± 0.08 μA/cm2 (at 45 minutes). The current magnitude reached a plateau between 30 and 60 minutes, staying at around 0.35 μA/cm2. After 60 minutes, the current began to decline slowly. However, even 6 hours after wounding, the wound edge current was still significantly greater (0.13 ± 0.03 μA/cm2) than the unwounded current (P < 0.04). Overlaying the human and rat time course data demonstrates that they have a very similar pattern of change over time (Fig. 3B; rat data from Reid et al14). The corneas used in this study were 3–5 days post mortem. The wound currents were therefore much smaller than would be seen in fresh tissue, and wound-healing rates were very slow. We were therefore unable to detect differences in wound healing rates in different treatments, which increased wound currents (see below).

FIGURE 3.

Time-dependent changes in wound current. A, Wound edge currents are actively modulated. Open symbol at time zero shows current before wounding. After wounding current rises rapidly, levels off for a time, then declines slowly (n = 3). The pattern of change is very similar to that in rat cornea (inset; data from Reid et al,14 2005). B, Overlaying human (open diamond symbols) and rat (closed circles) time course data shows the similar pattern of change over time. The rat data were scaled in the x axis to match the human data time points and scaled in the y axis so that the prewound (time zero) time points overlapped, and the maximum value from each trace (human: 0.41 mA at 45 minutes; rat: 11.19 mA at 40 minutes) were at the same level.

To determine if wound currents could be increased with pharmacological drugs or ion substitution, we placed corneas in solution with aminophylline or in chloride-free solution. Aminophylline is a nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor that is commonly prescribed medically as a bronchodilator to treat asthma. It also enhances ion pumping by elevating cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels and has been shown to increase short circuit current in frog cornea by increasing chloride transport from the aqueous humor to the tear side.34 In rat cornea the transcorneal potential difference in the presence of 10 mM aminophylline is more than twice normal size.35 We have also shown that 10 mM aminophylline significantly increases wound electric current in rat cornea in vitro, and in turn, significantly enhances rat cornea wound healing in vivo.14 Chloride ions seem to be a major carrier of the corneal wound current, and we have shown previously that chloride substitution significantly increases (more than doubles) wound current in rat cornea.14 In human cornea, we found that both these treatments more than doubled the size of the corneal wound edge current (Fig. 4) (P < 0.004). Using an ion-selective self-referencing microelectrode, we measured a significant influx of chloride ions at the edge of a scratch wound in a monolayer of cultured HCE cells (data not shown). So, in human cornea, as in rat,14 chloride is a major carrier of the wound electric current and therefore, a suitable target for pharmacological enhancement of corneal wound current (and corneal healing) in the patient.

FIGURE 4.

Enhancing wound currents. Wound edge current was significantly increased in chloride-free solution (n = 6) or aminophylline (10 mM; n = 4). * and # P < 0.004.

Discussion

The present study illustrates the feasibility of stimulating wound healing electrically without electrodes. We demonstrate that (1) the human cornea generates endogenous wound electric fields upon wounding; (2) the endogenous electric fields seem to be actively regulated; (3) either chloride replacement or aminophylline significantly enhances corneal wound electric current pharmacologically; and (4) as we have shown in rat cornea, this will correlate with an increased healing rate.

Human Corneal Wounds Generate Endogenous Electric Fields

Endogenous electric fields are generated at rat corneal wounds, and depletion of chloride or application of various drugs that enhance ion transport significantly increases endogenous wound electric fields and wound healing.9,14,36,37 To develop a potentially clinically applicable approach, we first confirmed the presence of endogenous electric currents at human corneal wounds because significant differences exist between species. For example, specific ionic fluxes that account for ion transport in corneal epithelium are different in mammals and amphibians. In amphibians, it is essentially chloride flux.38 In mammals, it is accounted for by approximately equal contributions of inwardly directed sodium transport toward the stroma and outwardly directed chloride transport into the tear film.39

Measurement of wound electric currents in human donor corneas confirmed that there are endogenous wound electric fields. Unwounded corneas had a very small outward current (0.07 μA/cm2), and wounding the cornea increased this almost 6 times to 0.41 μA/cm2 (Fig. 2). Time lapse experiments provided evidence that these currents are actively regulated because if the currents were passive leakage, they would reach a peak very soon after wounding and then decrease. In fact, it took 45 minutes for the currents to reach a peak, which indicates that the wounded cornea must regulate ion transport to increase the ionic flux. The time course of wound current change was remarkably similar to what we have seen in rat cornea14 (Fig. 3).

The wound electric currents here are significantly smaller than those we measured in rat corneal wounds. The peak value we measured in human corneal wounds averaged approximately 0.4 μA/cm2, which is much less than the maximum currents of about 11 μA/cm2 we measured in rat.14 This, again, may be because of the freshness of the corneas. The rat corneas were from freshly euthanized animals. All the corneas used in this study were those deemed nontransplantable for various reasons and were several days postmortem. A significant number of corneas had no measurable electric signals at all and were discarded. Fresh human corneas, if available, would most likely produce significantly larger currents.

Chemical and Pharmacological Enhancement of Endogenous Electric Fields

In rat corneal wound healing experiments, we demonstrated that the rate of wound healing is directly related to the size of the wound current; increasing or decreasing the current accelerates or slows down wound healing, respectively.14 HCE cells respond to an applied electric field within 10 minutes, actively migrating toward the cathode.28,30 Corneal wound healing in vivo is at least partially mediated by the guidance and stimulation of corneal epithelial migration and proliferation, possibly including stimulated nerve growth.9,14,36,40

Because the chloride ion is a major determinant of TEPD and wound electric currents,14,35 we determined the effect of modulating chloride concentration and stimulation of chloride transport on wound electric currents. As we found in rat cornea,14 we were able to increase (more than double) the size of wound currents significantly using chloride-free solution or the pharmacological drug aminophylline (Fig. 4). This raises the exciting possibility of developing a special topical agent (eg, low-chloride and/or aminophylline eyedrops) that might enhance corneal wound current and promote healing after injury or surgery. This is especially important in the neurotrophic or elderly patient or the patient with diabetes who may have reduced wound-healing ability.41

In conclusion, this report confirms for the first time that there are endogenous electric fields at human corneal wounds that are dynamically regulated. Substitution of chloride or stimulation of chloride transport pharmacologically significantly increased endogenous wound electric fields. Special eyedrops with low chloride and/or ion transportation–stimulating drugs may offer a new approach to stimulate corneal wound healing electrically without electrodes. This approach may also apply to other slow-healing epithelial wounds such as leg skin ulcers in elderly patients or patients with diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mrs Abby Hegler at Sierra Eye & Tissue Donor Services for help with obtaining human corneas.

M. Zhao is supported by grants from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine RB1-01417, National Science Foundation MCB-0951199, and NIH National Eye Institute grant 1R01EY019101. M. Zhao is also supported by University of California Davis Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science, and Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

References

- 1.Bjarnsholt T, Kirketerp-Moller K, Jensen PO, et al. Why chronic wounds will not heal: a novel hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broughton G, Janis JE, Attinger CE. Wound healing: an overview. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1e-S–32e-S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000222562.60260.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinh TL, Veves A. Treatment of diabetic ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:348–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCaig CD, Rajnicek AM, Song B, et al. Controlling cell behavior electrically: current views and future potential. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:943–978. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nuccitelli R. A role for endogenous electric fields in wound healing. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2003;58:1–26. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)58001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ojingwa JC, Isseroff RR. Electrical stimulation of wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao M. Electrical fields in wound healing—an overriding signal that directs cell migration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao M, Song B, Pu J, et al. Electrical signals control wound healing through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase-gamma and PTEN. Nature. 2006;442:457–460. doi: 10.1038/nature04925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hampton S, Collins F. Treating a pressure ulcer with bio-electric stimulation therapy. Br J Nurs. 2006;15:S14–S18. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.Sup1.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kloth LC. Electrical stimulation for wound healing: a review of evidence from in vitro studies, animal experiments, and clinical trials. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005;4:23–44. doi: 10.1177/1534734605275733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravaghi H, Flemming K, Cullum N, et al. Electromagnetic therapy for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002933.pub3. CD002933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart S, Rojas-Muñoz A, Belmonte JCI. Bioelectricity and epimorphic regeneration. BioEssays. 2007;29:1133–1137. doi: 10.1002/bies.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid B, Song B, McCaig CD, et al. Wound healing in rat cornea: the role of electric currents. FASEB J. 2005;19:379–386. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2325com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candia OA. Electrolyte and fluid transport across corneal, conjunctival and lens epithelia. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischbarg J, Diecke FP, Iserovich P, et al. The role of the tight junction in paracellular fluid transport across corneal endothelium. Electro-osmosis as a driving force. J Membr Biol. 2006;210:117–130. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0850-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinach PS, Capó-Aponte JE, Mergler S, et al. Roles of corneal epithelial ion transport mechanisms in mediating responses to cytokines and osmotic stress. In: Tombran-Tink J, Barnstable CJ, editors. Ocular Transporters in Ophthalmic Diseases and Drug Delivery. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 2008. pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiang M, Robinson KR, Vanable JW. Electrical fields in the vicinity of epithelial wounds in the isolated bovine eye. Exp Eye Res. 1992;54:999–1003. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90164-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sta Iglesia DD, Vanable JW. Endogenous lateral electric fields around bovine corneal lesions are necessary for and can enhance normal rates of wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 1998;6:531–542. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1998.60606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuberi M, Liu-Snyder P, Ul Haque A, et al. Large naturally-produced electric currents and voltage traverse damaged mammalian spinal cord. J Biol Eng. 2008;2:17. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuccitelli R, Nuccitelli P, Ramlatchan, et al. Imaging the electric field associated with mouse and human skin wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:432–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo A, Song B, Reid B, et al. Effects of physiological electric fields on migration of human dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.96. Advance online publication 2010, 22 April. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid B, Song B, Zhao M. Electric currents in Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Dev Biol. 2009;335:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuccitelli R. Endogenous electric fields in embryos during development, regeneration and wound healing. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2003;106:375–383. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lois N, Reid B, Song B, et al. Electric currents and lens regeneration in the rat. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shapiro S, Borgens R, Pascuzzi R, et al. Oscillating field stimulation for complete spinal cord injury in humans: a phase 1 trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:3–10. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.1.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao M, Penninger J, Isseroff RR. Electrical activation of wound-healing pathways. In: Sen CK, editor. Advances in Wound Care. Vol 1. New Rochelle, NY: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc; 2009. pp. 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farboud B, Nuccitelli R, Schwab IR, et al. DC electric fields induce rapid directional migration in cultured human corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2000;70:667–673. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimura KY, Isseroff RR, Nuccitelli R. Human keratinocytes migrate to the negative pole in direct current electric fields comparable to those measured in mammalian wounds. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:199–207. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao M, McCaig CD, Agius-Fernandez A, et al. Human corneal epithelial cells reorient and migrate cathodally in a small applied electric field. Curr Eye Res. 1997;16:973–984. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.10.973.9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huttenlocher A, Horwitz AR. Wound healing with electric potential. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:303–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr066496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid B, Nuccitelli R, Zhao M. Non-invasive measurement of bioelectric currents with a vibrating probe. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:661–669. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith PJS, Hammar K, Porterfield DM, et al. Self-referencing, non-invasive, ion selective electrode for single cell detection of trans-plasma membrane calcium flux. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;46:398–417. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990915)46:6<398::AID-JEMT8>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zadunaisky JA, Lande MA, Chalfie M, et al. Ion pumps in the cornea and their stimulation by epinephrine and cyclic-AMP. Exp Eye Res. 1973;15:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(73)90069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song B, Zhao M, Forrester JV, et al. Electrical cues regulate the orientation and frequency of cell division and the rate of wound healing in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13577–13582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202235299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin MH, Kim JK, Hu J, et al. Potential difference measurements of ocular surface Na+ absorption analyzed using an electrokinetic model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:306–316. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song B, Gu Y, Pu J, et al. Application of direct current electric fields to cells and tissues in vitro and modulation of wound electric field in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1479–1489. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zadunaisky JA, Lande MA. Active chloride transport and control of corneal transparency. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:1837–1844. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.6.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klyce SD. Transport of Na, Cl, and water by the rabbit corneal epithelium at resting potential. Am J Physiol. 1975;228:1446–1452. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.228.5.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song B, Zhao M, Forrester J, et al. Nerve regeneration and wound healing are stimulated and directed by an endogenous electrical field in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4681–4690. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mustoe T. Understanding chronic wounds: a unifying hypothesis on their pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Am J Surg. 2004;187:65S–70S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(03)00306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]