Abstract

Purpose

There is uncertainty regarding Hispanic individuals' depression treatment preferences, particularly regarding antidepressant medication, the most available primary care option. We assessed whether this uncertainty reflected heterogeneity among subgroups of Hispanic persons and investigated possible mechanisms. Specifically, we examined factors associated with medication preferences in non-Hispanic white, and Spanish-speaking and English-speaking Hispanic persons.

Methods

We analyzed data from a follow-up telephone interview of 839 non-Hispanic white and 139 Hispanic respondents originally surveyed via the 2008 California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Measures included treatment preferences (for treatment plans including versus not including antidepressants); depression history and current symptoms; socio-demographics; and psychological measures.

Results

Compared to non-Hispanic white respondents (adjusting for age, gender, history of depression diagnosis, and current depression symptoms), Spanish-speaking Hispanic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.41, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.19 - 0.90) but not English-speaking Hispanic (AOR = 1.18, 95% CI 0.60-2.33) respondents had a lower preference for antidepressant inclusive options. Endorsing a biomedical explanation of depression was associated with a preference for antidepressant inclusive options (AOR = 4.76, 95% CI 3.13 - 7.14) for all respondents and accounted for the effect of Spanish language interview. Accounting for other factors did not change these relationships, although older age and history of depression diagnosis remained significant predictors of antidepressant inclusive treatment preference for all respondents.

Conclusions

Spanish language interview and less belief in a biomedical explanation for depression, not ethnicity, were associated with Hispanic respondents' lower preferences for pharmacologic treatment of depression. Understanding treatment preferences and illness beliefs could help optimize depression treatment in primary care.

Keywords: Hispanic, depression treatment preferences, illness representation models

Introduction

Disparities in depression care between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white patients, such as under-diagnosis and under-treatment, persist after adjusting for care access barriers.1-3 People of Hispanic ethnicity represent a large and growing population in the United States4 and, when compared to other groups, receive a disproportionate amount of depression care in primary care settings.5,6 Therefore, for primary care practitioners depression is a common diagnosis and depression care disparities an especially salient problem. Since antidepressants are the most commonly offered therapy in primary care,7,8 understanding Hispanic patients' attitudes toward treatment of depression with medication may facilitate optimal care.9,10

Relatively few studies have examined the attitudes of Hispanic individuals toward depression treatment. Karasz and Watkins found that Hispanic patients feel that both antidepressants and counseling would be helpful treatments, but that counseling would be more helpful.11 Cooper et al. found Hispanic and white patients mostly accepting of both treatments, but Hispanic patients relatively less accepting of antidepressants and more accepting of counseling.12 Other studies suggest that Hispanic individuals prefer a combination of antidepressants and counseling over either alone13 and prefer counseling over antidepressants,14-16 at rates equal16 to or greater15 than white individuals.

Having a clear understanding of Hispanic patients' antidepressant treatment preferences is important, because counseling may be more effective when combined with antidepressant medication for some patients,17 antidepressant therapy is far more widely available than counseling in primary care,18 and preferences for a treatment that is effectively rationed could widen disparities. While previous studies suggest that Hispanic patients may prefer counseling, mixed findings and methodological limitations temper this conclusion. First, most prior studies involved small or homogeneous samples, precluding exploration of differences among subgroups of Hispanic individuals. This is a key limitation since Hispanic identity subsumes a number of cultural, racial, nativity, and generational groups, with differing patterns of mental health care use.19,20 Language preference (English or Spanish) is a frequently measured identifier of heterogeneity among Hispanic persons in both research and clinical resource planning.14,21-23 Language is not only a marker of acculturation,24 but also correlates with other important mediators of depression care preferences such as access to care.25,26 Second, prior experiences with and current symptoms of depression (which may influence treatment attitudes16, 27) were inconsistently included in prior analyses. Third, some studies lacked a “no treatment” preference response option,12,13 potentially biasing their findings. Finally, few studies explored beliefs behind patient treatment preferences. Understanding such beliefs could be useful in guiding efforts to mitigate disparities in depression care.16

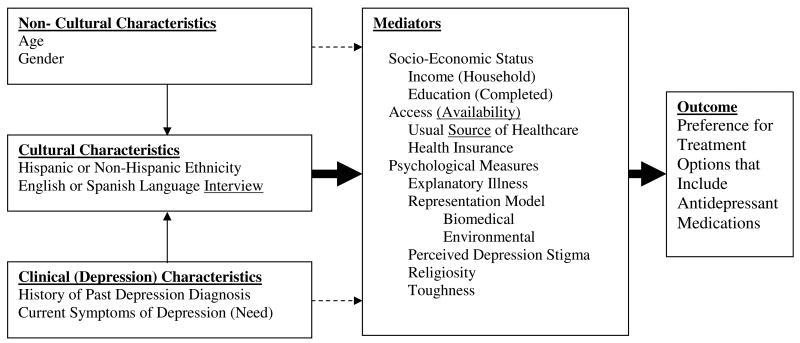

Based on the literature cited above and other previous literature on treatment attitudes16, 25-36, we proposed a conceptual model for the relationship between predictors and mediators of predictors of a preference for treatment options that include antidepressant medication to address these limitations (illustrated in Figure 1). We then resurveyed a sample of respondents to the 2008 California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to investigate two research questions in the context of the hypothesized model (Figure 1): (1) Is there significant heterogeneity in the preferences for treatment options that include antidepressants among English- or Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, after adjusting for key potential correlates of treatment preference (age, gender, depression history, and current depression symptoms)? (2) To the extent that significant heterogeneity does exist, what factors mediate the differences in Hispanic respondent language subgroups' preference for treatment options that include antidepressants? We examined the extent to which Hispanic respondents' attitudes towards antidepressants might be mediated by socio-economic, health care access-related, and psychological (depression illness representation models,28-30 perceived stigma of depression,31,32 toughness,33-35 and religiosity30,32,36) factors shown to influence attitudes toward medical treatments in prior studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Relationship of Respondent Characteristics and Mediators of Preferences for Treatment Options that Include Antidepressant Medications.

Methods

Sample

Subjects for the current follow-up study (administered July to December 2008) were sampled from respondents to the California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, originally administered from January through June 2008. Because the focus of the current survey was on attitudes toward and experience with depression and because equal probability sampling would yield too few respondents with a history of depression, subjects with a history of depression diagnosis were over-sampled (approximately threefold). Adjusting for over-sampling, we estimated that a combined study sample size of 1054 would provide 90% power to detect a difference approximating an effect size of 0.2 standard deviations (considered a small effect) on one of the study attitudinal scales (described subsequently) between those with and without a prior depression diagnosis.

Survey Procedures

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Survey

The BRFSS survey contains three components. The core component includes questions asked by all states and asks about current health-related perceptions, conditions and behaviors as well as demographic characteristics. The optional modules are sets of questions on specific topics which states elect [as edited and evaluated by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)] to use in their questionnaires. State-added questions are developed or acquired by participating states. These questions are not edited or evaluated by CDC. A detailed description of the items included in the core component, as well as the optional and state-added items specific to the California version of the BRFSS questionnaire used in 2008, is available elsewhere.37 Included in the California state survey was whether or not the respondent reported a history of a depression diagnosis. Other questions germane to this study included age, gender, the highest level of education obtained (categorized in years of schooling completed as less than 12; 12; 13-15; 16; or greater than 16), household income (categorized in dollars/year as less than 20,000; 20,000-34,999; 35,000-49,999; 50,000-74,999; 75,000-99,999; or greater than 100,000), and availability of health insurance and a usual source of medical care. Interviews were conducted in English or in Spanish as preferred by the participant. The California BRFSS survey has been administered since 1987 by the Survey Research Group, a section under the California Department of Public Health's Cancer Surveillance and Research Branch.

Follow-up Survey

We developed a 20 minute supplemental computer assisted telephone interview designed to assess participants' current depression symptoms (PHQ-9 38,39), future depression treatment preferences, depression illness representation models, perceived depression stigma, antidepressant medication beliefs, counseling beliefs, general religious attitudes, and general toughness attitudes. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, Davis. Like the BRFSS survey, this supplemental survey was administered by the Survey Research Group using the same standardized survey procedures. Sampling rates for the follow-up survey were calculated based on the standard definitions of the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR).40 Up to 15 attempts were made to contact each potentially eligible household. Excluding households of unknown eligibility (e.g. no answer or no eligibility screening completed), the response rate (RR5) was .49. The cooperation rate (COOP3), responding households excluding those in which eligible individuals did not complete the interview or were physically or mentally unable to be interviewed, was .61. Given these response rates, 2705 telephone numbers were used to generate the final sample of 1,054 completed interviews.

Treatment Preferences in the Follow-up Survey

Participants were asked their treatment preference in the event of a future diagnosis of depression. Options included: (1) taking antidepressant medication daily for at least 6 to 9 months; (2) weekly counseling for at least 2 months; (3) medication and counseling; or (4) wait and see (no treatment). To better represent the modal treatment experience, and in contrast to some other studies,12,13 options were constructed so as to include both treatment type and typical duration.

Psychological Measures in the Follow-up Survey

Psychological measures were multi-item scales. Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement to each item on a 5 point Likert scale (1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree) for all of the measures except religiosity, which was measured on a 4 point Likert scale. Responses were reverse-coded if necessary so that higher scale scores indicated greater levels of the given psychological construct. Two illness representation models were examined, the biomedical and environmental explanatory models. Items for each explanatory model measure were based on the Illness Representation Model and adapted from previous work.41-43 Factor analysis (results not shown) of the Illness Representation Model-based items supported our treatment of the items as two distinct constructs and scales were subsequently produced. The biomedical explanatory model scale included 6 items and Cronbach's alpha in this sample was 0.73. The environmental explanatory model scale included 2 items and Cronbach's alpha in this sample was 0.62. In order to compare explanatory models to each other, given the differing number of items in each scale, mean scores were used (range 1-5). For the other psychological measures, scores were summed. The depression stigma scale (3 items, range of scores 3-15; Cronbach's alpha 0.54) was adapted from Fogel and Ford.44 The religiosity scale (4 items, range of scores 4-16; alpha=0.87) was adapted from Rohrbaugh and Jessor.45 The toughness scale (4 items, range of scores 4-20; alpha=0.63), which reflects projections of independence, toughness, and denial of needs, was adapted from Fischer et al.46 The male-specific wording of the original items was modified to make them gender neutral. Individual items for all scales are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Individual Items Included in the Scales of Psychological Measures.

Biomedical Explanatory Illness Representation Model of Depression (alpha = 0.73)

|

Environmental Explanatory Illness Representation Model of Depression (alpha = 0.62)

|

Perceived Depression Stigma (alpha = 0.54)

|

Religiosity (alpha = 0.87)

|

Toughness (alpha = 0.63)

|

Note: Level of agreement with each item was rated on a 5 point Likert scale (1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree) for all of the measures except religiosity. Responses were reverse coded if necessary so that higher scale scores indicated greater levels of the given psychological construct.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata (version 11.0, College Station, TX) and accounted for the complex survey design of both the BRFSS and the subsample of the current survey (which over-sampled persons with a depression history) to yield appropriate standard errors and population parameter estimates. Subjects for the current study were sampled from 2 strata: those with and those without a depression history. California BRFSS weights47 were used, but further adjusted for the over-sampling of subjects with a depression history. The current analysis was restricted to those persons specifying either Hispanic ethnicity of any race or non-Hispanic ethnicity of white race, reducing the sample size for analysis from 1054 to 978 individuals.

For the purpose of analysis, treatment preferences were dichotomized into options that included antidepressants (taking antidepressants alone or combined with counseling) versus other treatment options (counseling only or wait and see). A series of logistic regression models were constructed to examine this dichotomized preference (dependant variable). To address the first question (treatment preference by ethnicity/interview language), respondents were categorized into non-Hispanic white, English-speaking Hispanic, and Spanish-speaking Hispanic groups (based on interview language). All analyses were adjusted for age, gender, prior history of depression diagnosis, and depression symptoms (PHQ-9 score). To address the second question (mediation), clusters of putative mediators (independent variables) were separately included in the regression analysis. The clusters were comprised of socio-economic variables (household income and education), health care access variables (availability of a personal healthcare practitioner and health insurance, both dichotomized as available or not), and each of the psychological variables: explanatory illness representation model (biomedical and environmental); stigma; toughness; and religiosity. Mediation was assessed by comparing regression coefficients between the models with and without the putative mediation cluster included. Coefficients were compared using the method of Clogg et al.,48 and implemented in Stata using the suest program. Confidence intervals around percent mediation effects were derived using Fieller's method.49 Finally, all potential mediators were included together to examine possible cumulative effects.

Results

Description of the Sample

The population-weighted characteristics (socio-demographic, clinical, attitudinal, and health care access) of the Spanish-speaking Hispanic, English-speaking Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white respondent subgroups are shown in Table 2. Compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, Hispanic respondents were significantly younger, less likely to be male, less likely to endorse a biomedical explanatory illness representation model, more likely to be religious, more likely to endorse toughness, and have completed fewer years of education. Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents, specifically, were more likely to report higher levels of depressive symptoms on the PHQ-9 and lower household incomes, and less likely to report having a personal healthcare practitioner or health insurance coverage.

Table 2. Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample, by Ethnicity and Interview Language.

| Characteristic | Ethnicity, Interview Language % (Standard Error) or Mean / Sums (Standard Error)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | Hispanic, English | Hispanic, Spanish | P** | |

| Total | N = 839, 73 % | N = 92, 15 % | N = 47, 11 % | NA |

| Age (years) | 50.9 (1) | 44.1 (2.5) | 42 (3.5) | <0.01 |

| Male Gender | 46.5 (2.6) | 39.9 (7.9) | 21.5 (7.5) | 0.03 |

| History of depression diagnosis | 15.4 (1.2) | 18.4 (4.1) | 11.5 (3.9) | 0.46 |

| PHQ 9 Score (range of sums 0-27) |

3.3 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.4) | 6.7 (1) | <0.01 |

| Biomedical Explanatory Model (range of means 1-5) |

4 (<0.1) | 3.8 (<0.1) | 3.5 (<0.1) | <0.01 |

| Environmental Explanatory Model (range of means 1-5) |

4 (<0.1) | 4 (<0.1) | 4.1 (0.1) | 0.81 |

| Stigma Scale (range of sums 3-15) | 7.6 (0.1) | 8.1 (0.4) | 7.9 (0.3) | 0.33 |

| Religiosity Scale (range of sums 4-16) |

9.4 (0.2) | 10.9 (0.5) | 11.5 (0.6) | <0.01 |

| Toughness Scale (range of sums 4-20) |

12.3 (0.1) | 12.7 (0.4) | 13.9 (0.6) | 0.02 |

| Education (years completed) | ||||

| <12 | 2.3 (0.8) | 14.2 (7.4) | 56.9 (10.2) | <0.01 |

| 12 | 14.5 (2.1) | 26.5 (7.7) | 12.0 (4.8) | |

| 13-15 | 28.5 (2.3) | 27.5 (5.9) | 21.4 (10.2) | |

| 16 | 29.8 (2.3) | 14.0 (4.4) | 1.5 (1.2) | |

| >16 | 24.9 (2.1) | 17.8 (5.9) | 8.2 (5.1) | |

| Income (dollars) | ||||

| <20,000 | 8.4 (1.2) | 9.7 (2.9) | 50.1 (10.2) | <0.01 |

| 20,000-34,999 | 10.0 (1.6) | 15.6 (4.7) | 25.1 (7.9) | |

| 35,000-49,999 | 11.4 (1.6) | 5.6 (2.5) | 7.9 (3.8) | |

| 50,000-74,999 | 18.3 (2.1) | 28.5 (7.8) | 16.9 (8.4) | |

| 75,000-99,999 | 20.1 (2.1) | 25.3 (8.0) | 0 (0) | |

| >100,000 | 31.8 (2.5) | 15.3 (5.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Has Personal Healthcare Practitioner | 85.3 (2.1) | 86.9 (4.1) | 41.8 (9.6) | <0.01 |

| Has Health Insurance | 94.2 (1.6) | 91.4 (3.5) | 68.4 (9.2) | <0.01 |

Notes:

Means/sums and percentages are population-weighted

P values are for Chi-Square or regression comparisons of all groups to each other

The population-weighted characteristics (socio-demographic, clinical, attitudinal, and healthcare access) of all respondents by their preference for depression treatment options are shown in Table 3. Those that preferred treatment options that included antidepressants were significantly less likely to be Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents and endorse toughness, and significantly more likely to be of older age, have a history of depression diagnosis, endorse a biomedical explanatory illness representation model, and report having a personal healthcare practitioner or health insurance coverage.

Table 3. Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample, by Depression Treatment Preferences.

| Characteristics | Treatment Preferences, % (Standard Error)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Only | Medication and Counseling | Counseling Only | Wait and See | |

| Total Sample (N = 976) | 9.4 (1.4) | 39.6 (2.3) | 36.5 (2.5) | 14.5 (2.1) |

| Ethnicity, Interview Language | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white (N = 837) | 9.1 (1.3) | 42.5 (2.5) | 34.5 (2.6) | 13.7 (1.9) |

| Hispanic, English (N = 92) | 11.8 (5.5) | 39.9 (7.5) | 31.8 (7.8) | 16.5 (6.5) |

| Hispanic, Spanish (N = 47) | 8.2 (5.2) | 20.9 (6.6) | 54.5 (10.2) | 16.4 (9.7) |

| Dichotomized Treatment Preferences, % (Standard Error) or Mean/Sums (Standard Error)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Options Including Medications | Options Other Than Medications | P** | |

| Total Sample | N = 588, 49.1 % | N = 388, 50.9 % | NA |

| Ethnicity, Interview Language | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 77.2 (3.1) | 69.5 (4.2) | 0.05 |

| Hispanic, English | 15.9 (2.8) | 14.3 (3.2) | |

| Hispanic, Spanish | 6.9 (1.9) | 16.2 (3.4) | |

| Age (years) | 53.2 (1.1) | 44.6 (1.4) | <.01 |

| Male Gender | 42.0 (3.9) | 42.4 (3.9) | 0.92 |

| History of depression diagnosis | 23.0 (1.6) | 8.6 (1.2) | <.01 |

| PHQ-9 Score (range of sums 0-27) |

4.1 (0.3) | 3.4 (0.4) | 0.14 |

| Biomedical Explanatory Model (range of means 1-5) |

4.1 (<0.1) | 3.7 (<0.1) | <.01 |

| Environmental Explanatory Model (range of means 1-5) |

2.0 (<0.1) | 2.0 (<0.1) | 0.92 |

| Stigma (range of sums 3-15) |

7.6 (0.2) | 7.8 (0.2) | 0.23 |

| Religiosity (range of sums 4-16) |

9.8 (0.2) | 9.9 (0.3) | 0.83 |

| Toughness (range of sums 4-20) |

12.2 (0.2) | 12.8 (0.2) | 0.03 |

| Education (years completed) | |||

| <12 | 7.4 (1.9) | 13.1 (3.4) | 0.20 |

| 12 | 14.9 (2.5) | 17.0 (3.3) | |

| 13-15 | 25.9 (2.6) | 29.1 (3.4) | |

| 16 | 26.5 (2.6) | 21.8 (2.9) | |

| >16 | 25.2 (2.7) | 18.9 (2.6) | |

| Income (dollars) | |||

| <20,0000 | 10.7 (1.6) | 16.2 (3.4) | 0.08 |

| 20,000-34,999 | 14.8 (2.4) | 10.6 (2.2) | |

| 35,000-49,999 | 10.1 (1.8) | 10.0 (2.0) | |

| 50,000-74,999 | 18.0 (2.6) | 21.3 (3.6) | |

| 75,000-99,999 | 15.8 (2.2) | 21.1 (3.4) | |

| >100,000 | 30.5 (2.9) | 20.7 (2.9) | |

| Has Personal Healthcare Practitioner | 84.8 (2.6) | 76.3 (3.8) | 0.05 |

| Has Any Health Insurance | 94.1 (1.7) | 87.6 (2.9) | 0.04 |

Notes:

Means/sums and percentages are population-weighted

P values are for Chi-Square or regression comparisons of all groups to each other

Options Including Medications = Medication Only taken for at least 6-9 months + Medication with Counseling

Options Other Than Medications = Counseling Only weekly for at least 2 months + Wait and See

Adjusted Predictors of Preference for Depression Treatment Options that Include Antidepressant Medications

The adjusted relationships between a preference for treatment options that included antidepressant medications (adjusted odds ratios) and respondent characteristics are shown in Table 4 (Models I-III). In the model adjusting only for age, gender, ethnic/interview language groupings, prior history of depression diagnosis, and current depression symptoms (Model I), a preference for treatments that included antidepressants was significantly more likely for older persons and those with a prior history of depression. Furthermore, addressing the first research question (possible differences between Hispanic respondents), a preference for treatment options that included antidepressants was significantly less likely for Spanish-speaking, but not English-speaking, Hispanic respondents when each were compared to non-Hispanic white respondents.

Table 4. Adjusted Predictors of Preferring Treatment Options that Include Antidepressant Medications in Non-Hispanic White and Hispanic Survey Respondents.

| Variables | MODEL I | MODEL II | MODEL III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Demographics and Depression History) | (Model I plus Illness Representations) | (Model II plus other Psychological, Socio-Economic, and Health Care Access variables) | ||||

| AOR | (95% CI) | AOR | (95% CI) | AOR | (95% CI) | |

| Age (per year) | 1.03 | (1.02-1.04)* | 1.03 | (1.02-1.04)* | 1.03 | (1.02-1.05)* |

| Men (Referent Group: Women) | 0.97 | (0.65-1.45) | 1.25 | (0.81-1.92) | 1.16 | (0.75-1.82) |

| History of depression diagnosis (Referent Group: no history) |

2.78 | (1.75-4.35)* | 2.17 | (1.39-3.33)* | 2.17 | (1.37-3.45)* |

| PHQ-9 Score (per unit) | 1.04 | (0.98-1.10) | 1.04 | (0.99-1.09) | 1.05 | (1.00-1.11) |

| Ethnicity/Language (Referent Group: Non-Hispanic White) |

||||||

| Hispanic-English Interview | 1.18 | (0.60-2.33) | 1.72 | (0.77-3.85) | 1.82 | (0.81-4.00) |

| Hispanic-Spanish Interview | 0.41 | (0.19-0.90)* | 0.84 | (0.35-2.00) | 0.68 | (0.28-1.69) |

| Biomedical Explanatory Model (per unit) | 4.76 | (3.13-7.14)* | 4.76 | (2.94-7.69)* | ||

| Environmental Explanatory Model (per unit) | 1.12 | (0.80-1.56) | 1.08 | (0.78-1.49) | ||

| Stigma (per unit) | 0.95 | (0.87-1.04) | ||||

| Religiosity (per unit) | 0.99 | (0.93-1.05) | ||||

| Toughness (per unit) | 0.99 | (0.92-1.06) | ||||

| Education (Referent Group:<12 years) | ||||||

| 12 years | 1.72 | (0.55-5.56) | ||||

| 13-15 years | 1.30 | (0.49-3.45) | ||||

| 16 years | 0.85 | (0.45-1.61) | ||||

| >16 years | 1.22 | (0.65-2.27) | ||||

| Income (dollars) (Referent Group: <20,000) | ||||||

| 20,000-34,999 | 1.96 | (0.85-4.55) | ||||

| 35,000-49,999 | 1.22 | (0.55-2.70) | ||||

| 50,000-74,999 | 1.59 | (0.74-3.45) | ||||

| 75,000-99,999 | 1.04 | (0.47-2.27) | ||||

| >100,000 | 2.13 | (1.00-4.55) | ||||

| Has Personal Healthcare Practitioner (Referent Group: no personal practitioner) |

0.74 | (0.38-1.43) | ||||

| Has Any Health Insurance (Referent Group: no health insurance) |

0.85 | (0.36-2.04) | ||||

| Comparisons of Parameter Estimates Model I versus Model II for Spanish-speaking Hispanics: F (1,972) = 21.41, p = <0.01 Model II versus Model III for Spanish-speaking Hispanics: F (1,971) = 0.43, p = 0.51 Model II versus Model III for Biomedical Explanatory Model: F (1,971) = 0.01, p = 0.93 | ||||||

Notes:

Includes responses for the whole sample (N = 978)

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

For all comparisons of categorical variables, the “Referent Group” as specified in the table have an AOR = 1 to which other categories for that variable are compared. These referent groups' AORs are not shown for simplicity.

For all comparisons of continuous variables, AORs are per unit (year, mean or sum)

* Denotes significant AOR (95% CI does not include 1)

Addressing the second research question (possible mediation of differences in Hispanic respondents' treatment preference), when the illness representation models were added (Model II), those who endorsed a biomedical explanatory illness representation model were significantly more likely to prefer treatment options that included antidepressants and the effect for Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents was attenuated (became non-significant). The attenuation of the effect for Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents was significant; that is, addition of the biomedical explanatory illness representation model explained 73% (95% confidence interval = 39%-100%) of the effect for Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents. Of the remaining variables in Model II, gender, level of current depression symptoms, and the environmental explanatory illness representation model exhibited no significant effect on preferences for treatment options that included antidepressants, while older age and a prior history of depression diagnosis remained significant. Furthermore, none of the other putative mediators (income, education, stigma, religiosity, toughness, having a personal healthcare practitioner, and having health insurance) that were separately included in the analysis exhibited any significant mediation of the relationships between either Spanish language interview, older age, or prior history of depression diagnosis, and preference for treatment options that included antidepressants (data not shown).

When the remaining variables (income, education, stigma, religiosity, toughness, having a personal healthcare practitioner, and having health insurance) were collectively added to the model (Model III) to examine for possible cumulative effects, the relationships between the variables already in the model (Model II) were not significantly altered. None of the variables (putative mediators) added in Model III from Model II made a statistically significant contribution.

Taken together, Models I-III in Table 4 show that for all respondents, only older age, a prior history of depression diagnosis, and endorsing a biomedical explanatory illness representation model were associated with higher odds of preferring treatment options that included antidepressants. Spanish language interview was also associated with significantly lower odds of preferring treatment options that included antidepressants, an effect observed only when the biomedical explanatory illness representation model was not included in the analytic model.

Discussion

Using data from a statewide population-based survey, we found significant heterogeneity within the Hispanic population in preferences for the most commonly offered depression treatment options in primary care.18 Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents were less likely to indicate preferences for options that included antidepressants than English-speaking Hispanic and non-Hispanic white respondents. Additionally, a biomedical explanatory illness representation model of depression was a powerful predictor of preference for treatment options that included antidepressants in all interview language/ethnicity groups (along with age and a history of depression diagnosis), and mediated the effect of interview language on treatment preference among Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents.

Language preference (Spanish versus English) is a subgroup-defining characteristic commonly used by researchers examining heterogeneity in and clinicians delivering care to the Hispanic population. Similarly, the focus of our study was not to investigate how language itself influences preferences for treatment options that include antidepressants. Rather, language preference may be viewed as a readily assessed marker for more complex, less easily defined and measured social characteristics that predict behavior.26 For example, some have argued that language preference is essentially a marker for access to health care,25 yet others have shown that differences in antidepressant use persist for Spanish-speaking Hispanic persons despite controlling for access.50 More often than as a marker for health care access, preferred language is viewed as a proxy for acculturation that subsumes other equally important Hispanic population characteristics such as race, socioeconomic status, nativity and generation. 14,22-24

To investigate these complex relationships, we examined possible mediators of attitudes toward antidepressant medication preference, adjusting for characteristics other than language/ethnicity associated with treatment preferences (history of depression diagnosis, current depression symptoms, age and gender). While a history of depression diagnosis (possibly due to treatment experience) and older age (possibly due to higher likelihood of depression diagnosis with increasing age) were associated with a preference for antidepressant-containing treatment options for all respondents, only a biomedical explanatory illness representation model of depression was found to mediate the effect of Spanish language interview on the lower preference for pharmacologic treatment options in Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents. Furthermore, this illness representation model itself was found to be an important predictor of these preferences in all groups when accounting for other factors. Variations in depression illness representations between ethnic groups51 and within the Hispanic population52 have been previously demonstrated. Illness representations have been identified as important predictors of treatment in other medical conditions28,29 and, more specifically, have been postulated as an important mediator of depression treatment in Hispanics.53,54 Our study adds to the limited existing evidence for this connection between illness representation models and depression treatment preference.15,30,55

Antidepressants are the most commonly available depression treatment in primary care,7 in part due to provider attitudes56 and barriers limiting access to counseling services.8 Furthermore, the addition of antidepressants to counseling may be more effective in treating depression than counseling alone in selected patients.17 Therefore, among Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients presented with antidepressant inclusive treatment plans, resistance to such plans created by lower preference for antidepressants may represent one important barrier to initiating or adhering to effective depression care in the primary care setting. Though our findings may apply at the population level, the clinical implications should be assessed cautiously.

Stereotyping Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients as “reluctant” to consider antidepressants without addressing individual depression explanatory models (as our mediation findings highlight) or treatment preferences could worsen disparities in depression care by denying antidepressant treatments to individuals for whom it might be both welcome and effective. Clinicians should avoid making assumptions based on population-level data and consider age, past history of depression treatment, and each individual patient's depression explanatory model (significant predictors in this analysis) along with culturally-based treatment beliefs, as part of developing a therapeutic plan. Similarly, those involved in clinical resource planning should consider these factors along with population characteristics such as ethnicity when allocating treatment resources. Ameliorating antidepressant medication reluctance may be achieved through health education and provider communication interventions implemented in primary care offices.9,10 The role of cross-cultural education for both primary care practitioners57,58 and designers of mental health care delivery systems may be essential to such targeted efforts.

Our study has some limitations. Data were drawn from a cross-sectional survey, so causal pathways cannot be established. Although results were weighted for non-response and telephone availability, the findings may be biased by telephone access, self-selection of call back participation, recall bias, and the low response rate of the BRFSS. Despite being a population-based study, there were also only small numbers of respondents in each of the analytic subgroups of Hispanic respondents, which could have led to false negative results. Furthermore, as discussed, dimensions of cultural identity other than language among Hispanic persons that might influence treatment attitudes, such as length of residence in the U.S., nativity, and race, were either unavailable or measured insufficiently due to small sample size for inclusion in our analyses. These two inter-related limitations to the generalizability of the findings may be especially relevant to our results for depression stigma, which has been shown in previous studies of Hispanic individuals to have a robust association with depression treatment preferences.59,60 Additionally, our attitudinal measures were adaptations of previously developed scales. Finally, given the format of our depression treatment choices, options such as spirituality-based interventions which may be important in some populations61 could not be fully explored.

In conclusion, we found that Spanish-speaking Hispanic respondents participating in the California BRFSS were less likely to endorse treatment with antidepressants than English-speaking Hispanic and non-Hispanic white respondents, and that this difference may be due to differences in underlying depression explanatory illness representation models. Greater understanding of factors leading to barriers to depression treatment in the settings where that treatment most frequently occurs can help direct targeted interventions to overcome these barriers effectively. Such coordinated steps may lead to improving depression outcomes. Therefore, our study suggests that understanding the mechanisms of depression treatment barriers to improve depression care for the Hispanic patients would benefit from further, larger studies in this heterogeneous population.

Acknowledgments

Support: This project was conducted with support from a National Institute of Mental Health Grant titled “Targeting and Tailoring Messages to Enhance Depression Care” (3R01MH079387). Erik Fernandez y Garcia received additional support from a Diversity Supplement to this parent grant (3R01MH079387-02S1).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: There are no potential financial or non-financial conflicts of interest for any of the authors. However, both Drs. Fernandez y Garcia and Kravitz received support from an unrelated and unrestricted research grant from Pfizer, Inc., which ended one year prior to the commencement of the work reported in this manuscript.

Prior Presentations: None

References

- 1.Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Miranda J, et al. Disparities in depression treatment for Latinos and site of care. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(12):1517–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Census Bureau Facts for Features CBO7-FF. 14. Hispanic Heritage Month 2007: Sept 15-Oct 15, 2007. [August 25, 2010]; Available at http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/010327.html.

- 5.Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Help seeking for mental health problems among Mexican Americans. J Immigr Health. 2001;3(3):133–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1011385004913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olfson M, Shea S, Feder A, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and substance abuse disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(9):876–83. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson WD, Geske JA, Prest LA, Barnacle R. Depression treatment in primary care. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(2):79–86. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Reimbursement of mental health services in primary care settings. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin P, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, et al. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Ann of Behav Med. 2005;30(2):164–73. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper LA, Brown C, Vu HT, et al. Primary care patients' opinions regarding the importance of various aspects of care for depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(3):163–73. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karasz A, Watkins L. Conceptual models of treatment in depressed Hispanic patients. Ann of Fam Med. 2006;4(6):527–33. doi: 10.1370/afm.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and White primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(4):479–89. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Aisenberg E, Hay J. Using conjoint analysis to assess depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):934–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabassa LJ, Lester R, Zayas LH. “It's like a labyrinth”: Hispanic immigrants' perceptions of depression and attitudes toward treatments. J Immigr Health. 2007;9(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Givens JL, Houston TK, Van Voorhees BW, Ford DE, Cooper LA. Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(3):182–91. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):527–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Trivedi M, Rush AJ. Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: which monotherapy or combined treatment? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):455–68. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rust G, Daniels E, Bacon J, Satcher D, Strothers H, Bornemann T. Research Letter: Ability to obtain mental health services for uninsured patients by community health centers. JAMA. 2005;293(5):554–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.554-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Catalano R. Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(6):928–34. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guarnaccia PJ, Pincay IM, Alegria M, Shrout P, Lewis-Fernandez R, Canino G. Assessing diversity among Latinos: Results from the NLAAS. Hisp J of Behav Sci. 2007;29(4):510–34. doi: 10.1177/0739986307308110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz P. Spanish, English, and mental health services. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1133–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07050853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folsom DP, Gilmer T, Concepcion B. A longitudinal study of the use of mental health services by persons with serious mental illness: Do Spanish-speaking Latinos differ from English-speaking Latinos and Caucasians? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1173–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06071239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on U.S. Hispanics. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(5):973–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(7):983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Stable EJ. Language access and Latino health care disparities. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1009–11. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815b9440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Schaik DJ, Klijn AF, van Hout HP, et al. Patients' preferences in the treatment of depressive disorder in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(3):184–89. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haggar MS, Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representation. Psychology and Health. 2003;18(2):141–84. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrie KJ, Jago LA, Devich DA. The role of illness perceptions in patients with medical illness. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(2):163–67. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328014a871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown C, Battista DR, Sereika SM, Bruehlman RD, Dunbar-Jacob J, Thase ME. Primary care patients' personal illness models for depression: relationship to coping behavior and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(6):492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):479–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):431–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cochran SV, Rabinowitz FE. Gender-sensitive recommendations for assessment and treatment of depression in men. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34:132–40. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Addis ME. Gender and depression in men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15(3):153–68. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, et al. Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2003;34:132–40. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayalon L, Young MA. Racial group differences in help-seeking behaviors. J Soc Psychol. 2005;145(4):391–403. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.145.4.391-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81(1):61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The American Association for Public Opinion Research Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. [August 25, 2010];2009 Available online at http://www.aapor.org/Standard_Definitions/1818.htm.

- 41.Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D. The Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychology and Health. 2002;17:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown C, Dunbar-Jacob J, Palenchar DR, et al. Primary care patients' personal illness models for depression: a preliminary study. Family Practice. 2001;18(3):314–20. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss-Morris R, Horne R. The Illness Perception Questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychology and Health. 1996;11:431–45. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fogel J, Ford DE. Stigma beliefs of Asian Americans with depression in an internet sample. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(8):470–8. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rohrbaugh J, Jessor R. Religiosity in youth: a personal control against deviant behavior. J Pers. 1975;43(1):136–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1975.tb00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischer AR, Tokar DM, Good GE, Snell AF. More on the structure of male role norms. Exploratory and multiple sample confirmatory analyses. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22:135–55. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) BRFSS Annual Survey Data. Survey Data and Documentation. BRFSS Weighting Formula. [May 14, 2010]; Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/BRfss/technical_infodata/weighting.htm.

- 48.Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A. Statistical Methods for Comparing Regression Coefficients between Models. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100(5):1261–93. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fieller EC. Some problems in interval estimation. (B).Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1954;16:175–83. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez HM, Tarraf W, West BT, et al. Antidepressant use in a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling US Latinos with and without depressive and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(7):674–81. doi: 10.1002/da.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1625–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karasz A, Sacajiu G, Garcia N. Conceptual models of psychological distress among low-income patients in an inner-city primary care clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(6):475–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cabassa LJ, Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Hansen MC, Xie B. Measuring Latinos' perceptions of depression: a confirmatory factor analysis of the Illness Perception Questionnaire. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14(4):377–84. doi: 10.1037/a0012820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cabassa LJ, Hansen MC, Palinkas LA, Ell K. Azucar y nervios: explanatory models and treatment experiences of Hispanics with diabetes and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(12):2413–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karasz A. The development of valid subtypes for depression in primary care settings: a preliminary study using an explanatory model approach. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(4):289–96. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816a496e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daniels ML, Linn LS, Ward N, Leake B. A study of physician preferences in the management of depression in the general medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1986;8(4):229–35. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(86)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural Humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–25. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Interian A, Ang A, Gara MA, Link BG, Rodriguez MA, Vega MA. Stigma and depression treatment utilization among Latinos: utility of four stigma measures. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(4):373–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.4.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born Black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(12):1547–54. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Mental health care preferences among low-income and minority women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(2):93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]