Abstract

Background

Efforts to improve quality of care for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are a national priority. To date, there have been few studies that have prospectively evaluated hospital quality improvement (QI) interventions.

Methods and Results

Using hospitals in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR®) ACTION Registry®–GWTG™, a cluster randomized trial of the effectiveness of targeted performance feedback to facilitate process improvement for AMI care will be conducted. ACTION Registry–GWTG hospitals with a minimum of 50 AMI patients per two quarters are eligible for randomization. The control arm receives standard performance feedback reports while the intervention arm receives standard performance feedback reports in addition to a supplemental report on the “top three” centrally-identified, hospital-specific performance gaps. The primary outcome will be improvement in a composite of all metrics, and the secondary outcome will be improvement in the targeted metrics. At study inception in January 2009, 149 sites were randomized; 76 to the intervention arm and 73 to the control arm. Intervention and control sites were well-balanced in terms of baseline performance, center characteristics, and AMI volume (~70 patients per quarter). The intervention phase will continue for 5 feedback cycles, each containing two quarters of data feedback over 18 months. A final trial outcome report will follow.

Conclusions

This randomized trial will evaluate a novel hospital-level QI intervention of targeted performance feedback for AMI, thereby demonstrating the effective use of national registries for QI and furthering our understanding of effective QI methods.

Clinical Trial Registration Information

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00952250: Targeted Feedback Reports to Improve Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACS) Care

Keywords: randomized controlled trials, quality improvement, acute myocardial infarction

The final translation of knowledge to the bedside is the consistent delivery of evidence-based practice across health care settings.1 Quality metrics and performance measures for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) care help identify best practices based on evidence.2 Centers with the highest performance on these quality measures have better patient outcomes, yet gaps remain with up to 25% of performance opportunities currently being missed.3 Performance measurement and feedback enables providers to recognize these deficiencies, or gaps in care.4 However, recognition of gaps by itself is insufficient to secure change.5, 6 Ideally, timely feedback should enable quality improvement (QI) teams to identify problem areas, and formulate an effective QI plan. Yet QI methods should be tested so ineffective strategies can be abandoned in lieu of better ones.7 A potential downfall of standard feedback is the inability for centers to extrapolate their primary deficiencies from the existing wealth of information. The Door-to-Balloon (D2B) Alliance national campaign was an example of a targeted feedback approach on a single aspect of performance.8 This effort was associated with an increase in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 90 minutes of hospital presentation for ST-segment elevation patients. The use of a similarly selective or targeted approach to a broader spectrum of performance measures, has yet to be explored.

The National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR®) ACTION Registry®–GWTG™ was created as a platform for hospitals to measure and improve their myocardial infarction (MI) care and to advance QI efforts.9 Therefore, within ACTION Registry–GWTG, a cluster randomized trial of a novel QI feedback method is currently being performed. This trial will definitively test a strategy of specific and targeted performance feedback versus standard feedback for its ability to better facilitate QI.

Methods

Data Sources

The ACTION Registry–GWTG includes detailed clinical information on >150,000 existing patients with either ST elevation or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI and NSTEMI). Participating hospitals submit data on consecutive patients with a primary diagnosis of STEMI or NSTEMI, as defined by: (1) ischemic symptoms at rest, lasting ≥ 10 minutes, occurring within 24 hours before admission or up to 72 hours for STEMI; (2) electrocardiogram (ECG) changes associated with STEMI (new left bundle-branch block [LBBB] or persistent ST segment elevation of ≥ 1 mm in two or more contiguous ECG leads); or (3) positive cardiac markers associated with NSTEMI (CK-MB or troponin I/T local laboratory upper limit of normal values) within 24 hours after initial presentation. Patients are ineligible for inclusion if they were originally admitted for clinical conditions unrelated to the STEMI or NSTEMI diagnosis. At most hospitals, patients are identified retrospectively through a review of local administrative or clinical databases. All data are entered via a secure password-protected web-based server system with programmed front-end logic and range checks to optimize data quality at the time of data entry. Data elements include patient demographics, presenting features, pre-hospital and in-hospital therapies, timing of care delivery, laboratory tests, procedure use, and inhospital patient outcomes. The ACTION Registry–GWTG case report form can be found at: www.ncdr.com.

All sites receive quarterly feedback reports describing the use of guideline-indicated therapies, dosing errors, and outcomes (e.g., bleeding, transfusion, MI, congestive heart failure [CHF], or death). These results are benchmarked to national averages, hospitals with similar cardiac service capabilities, and the hospitals which provide evidence-based AMI care most consistently.

Site Selection

Eligible ACTION Registry–GWTG sites had to meet the following criteria: (1) participation from January 1, 2007 through March 31, 2008; (2) a minimum of 50 records over the prior two quarters; (3) a minimum of 10 records each for STEMI and NSTEMI; and (4) agreement to participate in the project.

Randomization

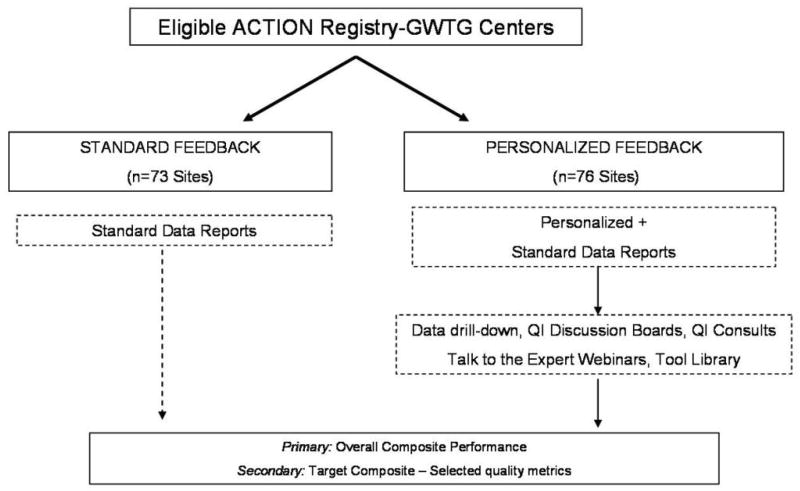

Eligible sites were randomized to control (standard feedback) or intervention (targeted feedback). Randomization was stratified by baseline quality performance score, academic status, and cardiac services (hospitals with cardiac surgery vs. other). Of the 149 eligible sites, 76 were randomized to intervention, and 73 were randomized to control (Figure 1). Institutional review board (IRB) approval for this QI project was obtained centrally by the coordinating center.

Figure 1. Cluster randomized trial design.

Eligible sites were randomized either to control or intervention and were stratified by baseline quality performance score, academic status, and cardiac services (hospitals with cardiac surgery vs. other).

Performance Measures and Quality Metrics

Performance measures undergo a rigorous process of public comment, whereas quality metrics are those of potential interest for hospital systems looking to improve their care.10 We chose performance measures and quality metrics based on the 2008 ACC/AHA Performance Measures for MI care as well as the newer ACTION Registry–GWTG metrics based on the current NSTEMI and STEMI Guidelines Updates11,12 (Table 1). In evaluating metrics for inclusion in this study, we prioritized those metrics that were the most actionable and amenable to change, as well as those with the largest anticipated impact on outcomes. These metrics are applied to the appropriate subpopulations (STEMI and NSTEMI) and population exclusions (e.g., contraindications) and are put in place where necessary. Quality performance scores on the standard reports include a composite of acute and discharge measures. Assessments for all AMI patients include: use of acute aspirin therapy, left ventricular (LV) function evaluation, discharge aspirin therapy, discharge beta blocker therapy, discharge angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy in the setting of LV dysfunction, discharge statin therapy, smoking cessation counseling for smokers, and referral to cardiac rehabilitation. Assessments for STEMI patients only include: door-to-needle ≤ 30 minutes, door-to-balloon for PCI ≤ 90 minutes, use of any reperfusion therapy, door-in to door-out time for transferred PCI patients, and door-to-balloon for non-transferred PCI patients. These composite performance scores summarize successes (e.g., number of times eligible patients received the appropriate care process) relative to all opportunities to deliver these care processes.

Table 1.

Performance Measures and Quality Metrics

| Metric | Eligible Patients | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Acute measures | ||

| Aspirin† | All AMI | Aspirin first 24 hours among those without contraindications |

| ECG ≤ 10 mins ‡ | Direct arrival | ECG prior to or within 10 minutes of ED arrival: includes pre-hospital ECG |

| Antiplatelet ‡ | NSTEMI only | Clopidogrel or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor first 24 hours among those without contraindications |

| Any antithrombin‡ | NSTEMI only | Heparin, LMWH, fondaparinux, or bivalarudin first 24 hours among those without contraindications |

| Discharge measure (without contraindications, exclude transfer out) | ||

| Aspirin† | All AMI | Aspirin at discharge |

| ACE/ARB for LVSD† | All AMI; EF < 40%, LV dysfunction | ACE/ARB at discharge for LVSD or signs of HF |

| Statin† | All AMI | Statin at discharge |

| Clopidogrel† | All AMI | Clopidogrel at discharge |

| In-hospital LDL† | All AMI | Assessment of LDL in-hospital |

| Cardiac rehabilitation† | All AMI | Referral to cardiac rehabilitation |

| Smoking cessation† | All AMI; Smokers | Advice to quit smoking among smokers |

| Excess dosing metrics | ||

| UFH† | Treated; exclude cath lab initiation | Initial UFH dose: bolus >70 U/kg or >4000U and/or infusion >15 U/kg/min or >1000U |

| LMWH† | Treated; exclude cath lab initiation | Initial LMWH dose 10mg over 24 hour recommended dose (2mg/kg/24 hrs if CrCl>30cc/min or 1mg/kg/24 hours if CrCl <30cc/min) or >1.05mg/dk initial dose. |

| GP2b3a † | Treated; exclude cath lab initiation | Initial GP2b3a dose: Not reduced if CrCl <50cc/min for eptifibatide, and CrCl <30cc/min for tirofiban |

| Reperfusion metrics (STEMI only; among those without contraindications) | ||

| Any reperfusion † | Chest pain onset ≤ 12 hours | Any reperfusion therapy |

| Door-to-needle ≤ 30 min † | Thrombolytic patients; direct arrival only | Time from presentation to thrombolytic therapy |

| Door-to-balloon ≤ 90 min† | Primary PCI; direct arrival only | Time from presentation to balloon |

| Door-to-balloon ≤ 90 min | Primary PCI; transfer-in only | Time from presentation to balloon |

| Transfer-in † | ||

Age and gender drill down performed for all measures. Patients with comfort measures only are excluded.

AHA/ACC Performance Measure 2008

2007 NSTEMI ACC/AHA Guidelines

ACE/ARB=angiotensin converting enzyme/angiotensin receptor blocker; AMI=acute myocardial infarction; CrCl=creatinine clearance; ECG=electrocardiogram; ED=emergency department; GP2b3a=glycoprotein 2b3a; HF=heart failure; LDL=low-density lipoprotein; LMWH=low molecular weight heparin; LVSD=left ventricular systolic dysfunction; NSTEMI=non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; UFH=unfractionated heparin

QI Intervention: Targeted Performance Reports

The data coordinating center compared each hospital’s performance on quality measure or metrics to performance of other hospitals with analyzable data. Performance was expressed as the percentage of the number of successes, relative to the number of care opportunities. For each metric, all hospitals with performance percentages were then rank-ordered from highest to lowest. Ties in performance were given the same numerical rank (e.g., 1,1,3,4,4,6, etc.). Hospitals were excluded from consideration for individual metrics if they lacked performance data. For example, some hospitals use no low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). Other hospitals exclusively perform direct PCI for STEMI; therefore no door-to-needle times from fibrinolysis are available. Rankings were used to identify three improvement targets for each site in the following way: three metrics with the worst numerical rank compared to other hospitals were identified, but any selected metric with an absolute performance ≥ 90% was excluded. There were compressed rankings within high levels of absolute performance for certain measures, like aspirin on admission (e.g., all percentages above 85%). Once selected, targets remained the same throughout the study period to allow time for meaningful changes to be assessed.

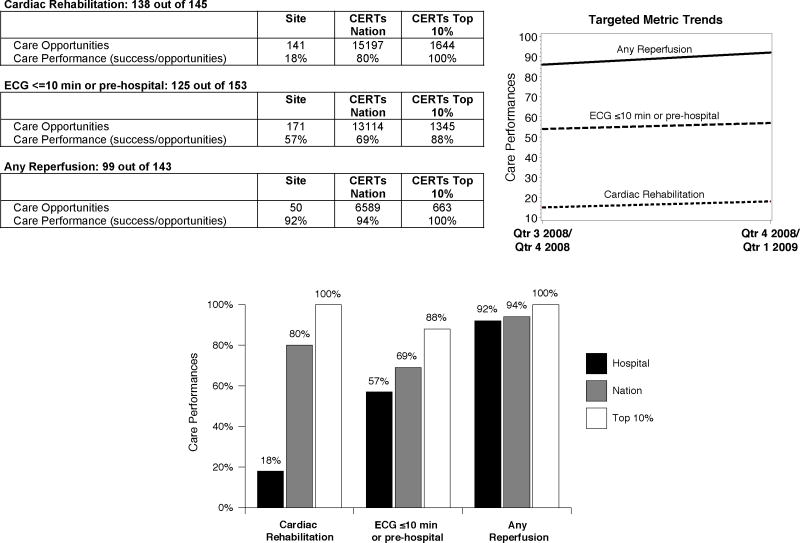

For the intervention arm, performance targets are presented on a report supplement (Figure 2). Care opportunities for each metric, along with ranking among all participating centers, called Centers for Education and Research on Therapeutics (CERTs) Nation, and top performers (CERTs Top 10%), are shown. This is to distinguish centers participating in this trial and all ACTION Registry–GWTG centers. Intervention sites will receive these special supplement reports every other quarter summarizing their performance on two quarters of AMI patients. Sites will be followed for five reporting periods. Improvement will be measured using ongoing data collection with trend graphs allowing centers to track performance over time. Supplemental data analyses provide a better understanding of performance among key subgroups (Appendix A). For example, if use of antithrombotic medications was low, then the report would provide further detailed information on antithrombotic use by clinical and process factors which might inform the gap. In addition, “outlier tables” (which list blinded identifiers for cases in the denominator, but not the numerator for each metric) are provided to the site for their internal use for hospital record review. These outlier tables are intended to help sites determine patterns that might have contributed to the omission.

Figure 2. CERTs NCDR ACTION Registry–GWTG report.

Top page of report; but not shown are supplementary analysis data for each metric and patient level outlier reports.

QI Intervention: Report Distribution

Each site was asked to provide multiple contacts for electronic report distribution. The average number of contacts per site was 2.4 (min=1, max=13). All sites had coordinator recipients and 28% of sites also had MD recipients. Reports were also posted on a secured web site for future downloading via password access. Training slides encouraged sharing of reports broadly within the institution.

QI Intervention: QI Community and Education

Intervention sites are connected via an interactive web-based community. Available by password entry, sites are able to exchange their own QI problems and solutions. Resources offered through this community also include evidence summaries, dosing guides, and order sets. Best practice tips also accompany the reports which describe successful strategies utilized in high performing centers (Appendix B). Order set review and recommendations by CERTs clinicians were offered for hospitals with dosing identified as an improvement target. Continuing medical education (CME) and continuing nursing education (CNE) modules were developed to address QI processes in general, as well as best practice recommendations for each of the target areas (e.g., acute and discharge care, reperfusion, dosing measures). These CME-certified web-based modules reviewed the evidence and outlined actionable steps for improved performance. These modules were originally delivered to sites live, but are now archived on www.cardiosource.org.

Analysis

The primary outcome of this analysis is improvement in the overall composite of all metrics. The secondary outcome is improvement in the composite of the three site-specific selected metrics. The level of observation is each performance opportunity, with potential for multiple observations per patient. Each care opportunity is coded as a binary indicator variable signifying success or failure. Each of these endpoints will be analyzed in a patient-level mixed-effects logistic regression model that includes covariates for the intervention arm, time, and the interaction between time and the intervention arm. The intervention will be considered successful if sites in the intervention arm exhibit greater improvement than sites in the control arm. We will also compare trends in patient outcomes including in-hospital bleeding and mortality. Outcomes will be assessed among all sites, and relevant performance subgroups (e.g., low performers, academic centers, cardiac services capability, and between medication vs. process metrics).

Statistical power is based on the anticipated effect of the intervention on individual metrics. We assumed that at the end of the study, the intervention would increase composite performance by at least 7%, compared to the control arm. We considered within-hospital correlation and secular linear trends in the control arm up to 5% per year with baseline adherence rates of 40%, 60%, or 80%. Despite these assumptions, there was ≥ 84% power for all scenarios. Metrics with a baseline performance rate greater than 80% had anticipated power close to 100%.

Results

The trial randomization resulted in balanced allocation between the two arms for hospital size, academic affiliation, cardiac surgery facilities, and baseline performance (Table 2). One in five hospitals are academically affiliated, and over 80% have full cardiac surgical services. The hospitals are moderate to large in size (median ~350 beds), and report MI care on between 50 and 70 patients per quarter. In addition, the overall performance at baseline was high across centers, with a median composite adherence on all metrics of 93.2%. The baseline composite adherence scores were also balanced between intervention and control arms, with lower overall quality adherence hospitals (<90%) comprising approximately one-third of the hospitals within each arm.

Table 2.

Hospital Characteristics

| Overall N=149 | Intervention N=76 | Control N=73 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic affiliation | 20.8 (31) | 21.1 (16) | 20.6 (15) |

| Cardiac services (%) | |||

| Cath lab only/none | 6.7 (10) | 5.2 (4) | 8.1 (6) |

| PCI (no surgery) | 10.1 (15) | 10.5 (8) | 9.6 (7) |

| Cardiac surgery | 83.2 (124) | 84.2 (64) | 82.2 (60) |

| Bed size† | 347 (244, 523) | 356 (254, 526) | 331 (231, 481) |

| STEMI patients per year † | 96 (68,162) | 88 (62, 142) | 104 (70, 184) |

| NSTEMI patients per year† | 140 (92, 220) | 136 (84, 195) | 148 (100, 240) |

| Composite guideline score† | 93.2 (88.2, 96.2) | 92.8 (89.3, 95.8) | 93.7 (87.8, 96.5) |

| Low composite adherence* | 36.2% | 35.5% | 37.0% |

| Region | |||

| West | 16.1 (24) | 18.4 (14) | 13.7 (10) |

| Northeast | 8.7 (13) | 10.5 (8) | 6.9 (5) |

| Midwest | 34.2 (51) | 30.3 (23) | 38.4 (28) |

| South | 40.9 (61) | 40.8 (31) | 41.1 (30) |

| Targeted metrics £ %, n | |||

| Acute measures | 73.8 (110) | 73.7 (56) | 74.0 (54) |

| Discharge measure | 84.6 (126) | 82.9 (63) | 86.3 (63) |

| Dosing measure | 36.9 (55) | 35.5 (27) | 38.4 (28) |

| Reperfusion measure | 28.9 (43) | 34.2 (26) | 23.3 (17) |

Low adherence is <90% composite

Median, 25th and 75th percentile

Centers with any acute, discharge, dosing or reperfusion metrics selected as targets Cath=catheterization; NSTEMI=non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

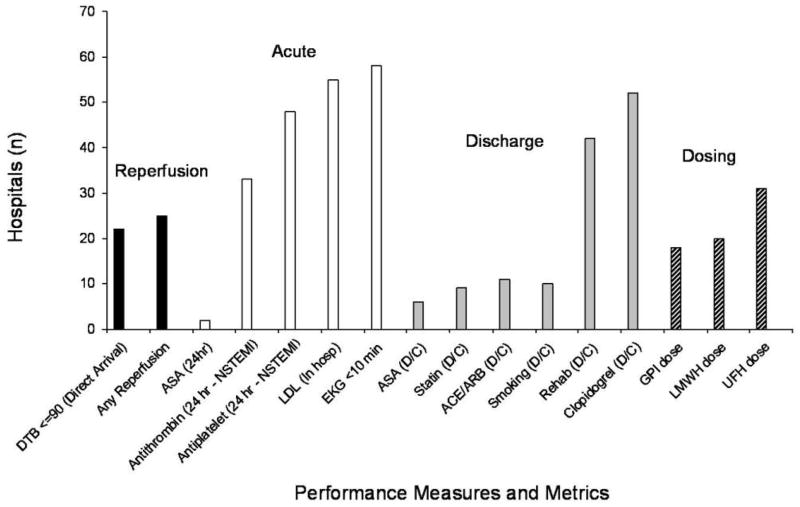

The baseline distribution of the centrally-selected “top three” performance targets is shown in Figure 3. Acute and discharge measures were selected for three-quarters of the hospitals, and reperfusion and dosing measures were selected for one-third of the hospitals; again evenly balanced between arms. Newer measures such as time-to-ECG ≤ 10 min, in-hospital low-density lipoprotein (LDL) assessment, and clopidogrel at discharge, were most common. Of note, door-to-needle times ≤ 30 minutes and door-to-balloon times ≤ 90 minutes for transfer patients were not selected for any hospital.

Figure 3. Distribution of top three performance targets.

The number of centers selected for each metric is shown by cluster (reperfusion, acute, discharge, dosing). Note: No centers selected for door-to-PCI among transfer patients or for door-to-needle.

To date, three report cycles have been completed. Site contacts note the level of detail in the reports is manageable and helpful.

Discussion

This trial evaluated the role of targeted feedback versus standard feedback for improving AMI care. We found that hospital-level performance gaps are evenly distributed across categories of care (e.g., acute and discharge metrics, reperfusion and dosing), and vary within each center. Although overall performance was higher in top centers, three targets for improvement were identified for every hospital. In addition, new quality measures (e.g., time-to-ECG, dosing excess) were more often selected for improvement targets, compared to those which have longer been a focus of QI efforts (e.g., aspirin at discharge). This observation supports the importance of selecting site-specific targets from an evolving expanded panel of performance metrics. Building on prior experience, this intervention combines feedback with best practice tips from the community, QI discussion boards, and educational support. The trial duration was selected to enable adequate time to observe a change in response to the intervention;13 therefore, we will definitively test the value of hospital-specific targeted performance feedback to facilitate improvements in hospital MI care.

Prior QI Interventions

Early feedback for myocardial infarction care using simple administrative data was successful in improving performance and mortality among participating hospitals.14 Since that time, large registries have been established to retrospectively collect more detailed information directly from the medical record.9, 15, 16 This data, which is provided as standard feedback to participating hospitals, has narrowed performance gaps further—even among high-risk populations.17, 18 Over time, high performance in measures has enabled their retirement, while gaps in others still remain.19 Although few in number, randomized interventions for QI strategies have furthered our understanding of effective methods for improving AMI care. One trial found that a single episode of administrative feedback was ineffective, underscoring the need for ongoing feedback.20 Another found no difference in mailed versus in-person delivery of performance reports, enabling centralized distribution to a variety of centers.21 An important trial also found that achievable benchmarks for performance clarified and motivated improvement.22 Foremost, the elements necessary for QI are reliable data feedback, coupled with physician-led efforts.13, 23

Current QI Intervention

The current intervention builds on prior works in QI. First, the ACTION Registry–GWTG is the largest national registry of AMI care, and provides rapid and credible feedback as a dynamic platform for QI research. In addition, target identification and ranking provides hospitals with achievable performance goals. The panel of metrics used in this study is also more comprehensive than in prior works, including performance measures and quality metrics. This comprehensive panel revealed that performance within each hospital is variable across this broader group of measures, with high performance coexisting with low performance. This underscores the idea that performance on QI measures should be independently assessed, and also bypasses a pitfall that centers may be reassured by performance on some metrics, undervaluing efforts to improve others.24

Only three targets were selected for the supplemental reports, but they are supported by additional data analysis and outlier reports. We hope target selection will focus efforts at the hospital level, thereby activating QI processes (with the use of feedback being left up to the center’s discretion). Nevertheless, feedback in the absence of administrative support or leadership may be ineffective.5 Therefore, the ability of targeted feedback to motivate hospital-level QI will be tested. If no differences are found between the intervention and control groups, further work on understanding the role of the local environment may be necessary. However, if the intervention is successful, this strategy can be promptly implemented in the ACTION Registry–GWTG.

There are limitations to the generalizability of this trial. The ACTION Registry-GWTG sites are high performing centers with sufficient infrastructure to participate in a national registry. They are also likely to prioritize QI more than non-participating centers. From among these, we further selected centers with high volume consistent reporting. Therefore, these hospitals are mature in their QI process and infrastructure and may not represent the average center. In addition, how the feedback is used at each center is not proscribed or evaluated. Accordingly, local environmental factors may impact the results, yet randomization should balance unmeasured factors between intervention and control sites. Finally, these measures, although new and expanded, remain granular in their ability to identify highest AMI quality of care.

The gap between ideal and actual performance requires identification of gaps, as well as the tools, to fix them. Research in QI is necessary to optimize the final translation of knowledge to the bedside. This randomized QI feedback trial within the ACTION Registry–GWTG will test the ability of selected targets to rapidly facilitate hospital improvement in MI care. This effort is also evidence to the ACTION Registry–GWTG’s ability to serve as a data platform and dynamic community for such studies. Future trials that build upon the results of this study will surely be needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Erin LoFrese for her editorial contributions to this manuscript, and Alex Briskman, Susan Rogers, Kim Hustler, Renee Laughlin Rubin, Christina Chadwick, Karen Thompson, Melissa Valentine, Kelly LeTard, and Jack O’Brien, for their contributions on specific aspects of project implementation.

Funding Sources: This project was supported by grant number U18HS010548 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The ACTION Registry®–GWTG™ is an initiative of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association, with partnering support from Society of Chest Pain Centers, The Society of Hospital Medicine, and The American College of Emergency Physicians. The registry is sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: TY Wang - Research grant: Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Pharmaceuticals, Heartscape Technologies, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering Plough Corporation, The Medicines Company; education activities or lectures: Heartscape Technologies. MT Roe - Research grant: Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co., Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough Corporation; consulting: AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, Glaxo SmithKline, Merck & Co., Novartis Pharmaceutical Company, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough Corporation. JS Rumsfeld - Chief Science Officer for the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR). CP Cannon - Research grant: Acumetrics, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Intekrin Therapeutis, Merck, Takeda; advisory board (but funds donated to charity): Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi, Novartis, Alnylam; honorarium for development of independent educational symposia: Pfizer, AstraZeneca; clinical advisor and equity in: Automedics Medical Systems. ED Peterson - Research grant: American College of Cardiology, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, Johnson & Johnson, Merck & Co., Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough Corporation, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Heart Association; consulting: Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck & Co., Tethysbio, Astra Zeneca

References

- 1.Dougherty D, Conway PH. The “3T’s” Road Map to Transform US Health Care: The “How” of High-Quality Care. JAMA. 2008;299:2319–2321. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Bachelder BL, Fesmire FM, Fihn SD, Foody JM, Ho PM, Kosiborod MN, Masoudi FM, Nallamothu BK. ACC/AHA 2008 Clinical Performance Measures for Adults with ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a Report of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Performance Measures for ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;118:2596–2648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Mulgund J, De Long ER, Lytle BL, Brindis RG, Smith SC, Pollack CV, Newby LK, Harrington RA, Gibler WB, Ohman EM. Association between Hospital Process Performance and Outcomes Among Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295:1912–1920. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.16.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Williams OD, Person SD, Weaver MT, Weissman NW. Improving quality improvement using achievable benchmarks for physician feedback: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2871–2879. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Mattera JA, Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Frederick P, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Quality Improvement Efforts and Hosptial Performance: Rates of Beta-blocker Prescription after acute myocardial infarction. Med Care. 2005;43:282–292. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Data feedback efforts in quality improvement: lessons learned from US hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:26–31. doi: 10.1136/qhc.13.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The Tension between Needing to Improve Care and Knowing How to Do It Sounding Board. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:608–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb070738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, Herrin J, Ting HH, Stern AF, Nembhard IM, Yuan CT, Green JC, Kline-Rogers E, Wang Y, Curtis JP, Webster TR, Masoudi FA, Fonarow GC, Brush JE, Jr, Krumholz HM. National efforts to improve door-to-balloon time results from the Door-to-Balloon Alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2423–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Rumsfeld JS, Shaw RE, Brindis RG, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP. A Call to ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) A National Effort to Promote Timely Clinical Feedback and Support Continuous Quality Improvement for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:491–499. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.847145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonow RO, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, DeLong E, Estes M, Goff DC, Grady K, Green LA, Loth AR, Peterson ED, Piña IL, Radford MJ, Shahian DM. ACC/AHA Classification of Care Metrics: Performance Measures and Quality Metrics A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2113–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, Jr, King SB, 3rd, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DJ, Jr, Green LA, Hochman JS, Jacobs AK, Krumholz HM, Morrison DA, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Peterson ED, Sloan MA, Whitlow PL, Williams DO. 2009 Focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on PCI: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2009;120:2271–2306. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, Chavey WE, II, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:652–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson TB, Peterson ED, Coombs LP, Eiken MC, Carey ML, Grover FL, DeLong ER. Use of Continuous Quality Improement to Increase Use of Process Measures in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2003;290:49–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, Kresowik TF, Gold JA, Krumholz HM, Kiefe CI, Allman RM, Vogel RA, Jencks SF. Cooperative Cardiovascular Project: Results From the Improving the Quality of Care for Medicare Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 1998;279:1351–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta RH, Montoye CK, Faul J, Nagle DJ, Kure J, Raj E, Fattal P, Sharrif S, Amlani M, Changezi HU, Skorcz S, Bailey N, Bourque T, LaTarte M, McLean D, Savoy S, Werner P, Baker PL, DeFranco A, Eagle KA American College of Cardiology Guidelines Applied in Practice Steering Committee. Enhancing quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: shifting the focus of improvement from key indicators to process of care and tool use: the American College of Cardiology Acute Myocardial Infarction Guidelines Applied in Practice Project in Michigan: Flint and Saginaw Expansion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2166–2173. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoekstra JW, Pollack CV, Jr, Roe MT, Peterson ED, Brindis R, Harrington RA, Christenson RH, Smith SC, Ohman EM, Gibler WB. Improving the care of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes in the emergency department: the CRUSADE initiative. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1146–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander KP, Roe MT, Chen AY, Lytle BL, Pollack CV, Foody JM, Boden WE, Smith SC, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED for the CRUSADE Investigators. Evolution in cardiovascular care for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE National Quality Improvement Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1479–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta RH, Roe MT, Chen AY, Lytle BL, Pollack CV, Jr, Brindis RG, Smith SC, Jr, Harrington RA, Fintel D, Fraulo ES, Califf RM, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED. Recent trends in the care of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the CRUSADE initiative. Arch Int Med. 2006;166:2027–2034. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee TH. Eulogy for a Quality Measure. JAMA. 2007;357:1175–1177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck CA, Hugues R, Tu JV, Pilote L. Administrative Data Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment: AFFECT, a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;294:309–317. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauaia A, Ralston D, Schluter WW, Marciniak TA, Havranek EP, Dunn TR. Influencing care in acute myocardial infarction: a randomized trial comparing 2 types of intervention. Am J Med Qual. 2000;15:197–206. doi: 10.1177/106286060001500503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Williams OD, Person SD, Weaver MT, Weissman NW. Improving Quality Improvement Using Achievable Benchmarks for Physician Feedback. JAMA. 2001;285:2871–2875. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Gurwitz JH, Guadagnoli E, Hauptman PJ, Borbas C, Morris N, McLaughlin B, Gao X, Willison DJ, Asinger R, Gobel F. Effect of local medical opinion leaders on quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1358–1363. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang TY, Fonarow GC, Hernandez AF, Liang L, Ellrodt G, Nallamothu BK, Shah BR, Cannon CP, Peterson ED. The dissociation between door-to-balloon time improvement and improvements in other acute myocardial infarction care processes and patient outcomes. Arch of Int Med. 2009;169:1411–1419. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.