Abstract

In the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides, a transcriptional response to the reactive oxygen species singlet oxygen (1O2) is mediated by ChrR, a zinc metalloprotein that binds to and inhibits activity of the alternative sigma factor, σE. We provide evidence that 1O2 promotes dissociation of σE from ChrR to activate transcription in vivo. To identify what is required for 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, we analyzed the in vivo properties of variant ChrR proteins with amino acid changes in conserved residues of the C-terminal cupin-like domain (ChrR-CLD). We found that 1O2 was unable to promote detectable dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes when the ChrR-CLD zinc ligands (His141, His143, Glu147, and His177) were substituted with alanine, even though individual substitutions caused a 2- to 10-fold decrease in zinc affinity for this domain relative to that of wild-type ChrR (Kd ∼4.6 × 10−10 M). We conclude that the side chains of these invariant residues play a crucial role in the response to 1O2. Additionally, we found that cells containing variant ChrR proteins with single amino acid substitutions at Cys187 or Cys189 exhibited σE activity similar to those containing wild-type ChrR when exposed to 1O2, suggesting that these thiol side chains are not required for 1O2 to induce σE activity in vivo. Finally, we found that the same aspects of R. sphaeroides ChrR needed for a response to 1O2 are required for dissociation of σE/ChrR in the presence of the organic hydroperoxide, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH).

Keywords: Bacterial signal transduction, metalloproteins, Oxidative stress, Reactive oxygen species (ROS), zinc

Introduction

Oxygen (O2) has several crucial roles in biological systems. O2 can function as a terminal electron acceptor for bioenergetic pathways like aerobic respiration and serve as a signal to control gene expression 1–3. While O2 is relatively inert, it can be converted to reactive oxygen species by either electron addition (superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical) or energy transfer (singlet oxygen) reactions 1. Considerable information is available on the role of metalloproteins in the responses to superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, or organic hydroperoxides 4–6. However, much less is known about how singlet oxygen (1O2) damages proteins or cells 7–9. We are interested in determining how biological systems are altered by and respond to 1O2.

This reactive oxygen species has broad relevance since several biological processes generate 1O2 10. Photosynthetic organisms, in particular, produce significant amounts of 1O2 as a byproduct of solar energy capture 11. Our studies capitalize on what is known about a transcriptional response to 1O2 in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. In this bacterium, a transcriptional response to 1O2 12 is controlled by the alternative sigma factor, σE, and the zinc metalloprotein ChrR. In the absence of 1O2, ChrR forms a 1:1 heterodimeric complex with σE, preventing the σ factor from binding core RNA polymerase and initiating transcription of target genes 13–14. It has been proposed that the functions of this sigma factor and its metalloprotein regulator in controlling a transcriptional response to 1O2 have been conserved through evolution, as homologues of R. sphaeroides ChrR and σE, as well as some target genes of σE, are distributed across the bacterial phylogeny15. Indeed, there is emerging evidence that prokaryotes and eukaryotes activate transcription of genes encoding similar functions to R. sphaeroides σE target genes after exposure to 1O2 16.

Molecular insight into how ChrR inhibits σE activity was obtained from the 3-dimensional structure of the σE/ChrR complex 17. In the σE/ChrR complex, the ChrR N-terminal domain coordinates a zinc atom and makes extensive contacts with regions of σE predicted to bind either RNA polymerase or promoter DNA. As predicted by the structure, a truncated ChrR protein comprised of only the N-terminal domain (ChrR85) was able to inhibit σE activity in vivo and in vitro. Consequently, the ChrR N-terminal domain was termed the anti-σ domain (ChrR-ASD) 17. The ChrR N-terminus contains a zinc atom that is essential for anti-σ factor activity, as substitutions to any of three amino acid residues coordinating this zinc (His6, Cys35, or Cys38) render it unable to form a complex with and inhibit the activity of σE 17. The ChrR C-terminal domain structurally resembles the cupins, a diverse protein family containing a conserved β-barrel fold 18–19, so it has been called the ChrR cupin-like domain (ChrR-CLD). The ChrR-CLD can also bind a zinc atom via the side chains of His141, His143, Glu147, and His177 17. The affinity of the two zinc atoms within ChrR is apparently different, since dialysis in the presence of the zinc chelator DTT only removes the metal from the ChrR-CLD 17. Two additional relevant observations were made when function of σE/ChrR complexes lacking the ChrR-CLD was tested in vivo 17. First, loss of the ChrR-CLD does not prevent the ChrR-ASD from inhibiting σE activity. Second, loss of the ChrR-CLD blocked 1O2 from initiating the σE-dependent transcriptional response 17, suggesting that this domain contains one or more elements necessary for 1O2 to promote this response.

This work analyzed how the presence of 1O2 triggers this σE-dependent transcriptional response. We found that R. sphaeroides can initiate the σE-dependent transcriptional response to 1O2 in the absence of de novo protein synthesis, suggesting that this reactive oxygen species somehow promotes dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes rather than using newly synthesized σE to control the response. Based on this finding and previous observations that the ChrR-CLD is needed for 1O2 to stimulate the σE-dependent transcriptional response 17, we probed the ability of this reactive oxygen species to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes with single amino acid substitutions at invariant residues within the ChrR-CLD. We found that alanine substitutions at amino acid ligands to zinc in the ChrR-CLD prevented 1O2-mediated dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, even though these variant σE/ChrR complexes retained the ability to bind zinc. While some amino acid substitutions at conserved cysteine residues in the ChrR-CLD caused a partial defect in inhibiting σE activity or exerted an effect on the affinity for zinc by this domain (though located over 12 Å away from the zinc site), they did not prevent cells from activating σE expression during exposure to 1O2. Our results do not support previous models that zinc binding by the ChrR-CLD is necessary for 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes 17. We also present evidence that the organic hydroperoxide tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH), but not cadmium, induces σE activity in R. sphaeroides. Thus, the R. sphaeroides σE/ChrR system has similarities to and differences from the homologous Caulobacter crescentus σE/ChrR system 20.

Results

1O2 promotes dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes

We sought to distinguish between two mechanisms by which the presence of 1O2 could initiate the σE-dependent transcriptional response. 1O2 could initiate the σE-dependent transcriptional response by promoting dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes. Alternatively, 1O2 could activate this transcriptional response by preventing newly synthesized ChrR from binding σE To distinguish between these possibilities, the effect of 1O2 on the σE-dependent transcriptional response was analyzed in cells treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor chloramphenicol (Cm). We reasoned that σE-dependent transcription would increase in Cm-treated cells if 1O2 promoted dissociation of existing σE/ChrR complexes but not if de novo synthesized σE was required for this response. Results of control experiments indicated that adding 200 µg/ml Cm to exponentially growing cells for 15 min was 95% efficient at inhibiting protein synthesis relative to untreated cultures (data not shown).

We used qRT-PCR to monitor RNA levels from two known σE target genes: rpoE, the structural gene for σE, and RSP1409, annotated to encode a fasciclin-like protein of unknown function. Transcript levels from a control gene rpoZ (encoding the Ω subunit of RNA polymerase) that lacks a σE promoter and is not a known member of this 1O2 transcriptional response were measured to normalize transcriptional activity. As expected, rpoZ transcript levels did not change significantly in the absence or presence of 1O2 and/or Cm (data not shown). In the absence of 1O2, we detected a low steady-state level of rpoE and RSP1409 transcripts, as expected 12–14, 17. When cells were exposed to 1O2 in the absence of Cm, we observed an expected increase in abundance of these σE-dependent transcripts 12. After normalization to rpoZ transcript levels, there was a significant increase in the abundance of both rpoE (15-fold) and RSP1409 (32-fold) transcripts after 5 min of 1O2 exposure; the abundance of these transcripts either remained high or increased further after 15 min of continued 1O2 exposure (Figure 1). Similarly, in Cm-treated cells, the normalized levels of the rpoE and RSP1409 transcripts increased after 5 min of 1O2 exposure (12-fold and 25-fold, respectively), and remained high throughout this experiment (Figure 1). These results indicate that 1O2 can initiate the σE-dependent transcriptional response when protein synthesis is inhibited by the addition of Cm. Since new protein synthesis is not required for 1O2 to initiate the σE-dependent transcriptional response, we conclude that this reactive oxygen species promotes dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, presumably by somehow inactivating extant ChrR.

Fig. 1. Relative levels of σE target gene transcripts (RSP1409 and rpoE) before and during 1O2 stress in the absence (●) or presence (▪) of the protein synthesis inhibitor chloramphenicol (Cm).

Shown are transcript levels for two known σE target genes, RSP1409 (top panel) and rpoE (bottom panel), in cells that were or were not treated with Cm before and during exposure to 1O2 (generated by exposing photosynthetic cells to oxygen in the light). The vertical arrow at zero min indicates the time when cells were exposed to 1O2. In the Cm-treated culture, Cm was added 15 min prior to exposure to 1O2. Transcript levels reported were normalized relative to those from a control σE-independent gene (rpoZ) at each time point.

Single substitutions at conserved amino acids in the ChrR-CLD do not prevent ChrR from inhibiting σE activity

Since previous studies indicated that the ChrR-CLD is required for this transcriptional response to 1O2 in vivo 17, we analyzed function of a series of variant ChrR proteins each containing amino acid substitutions at residues in the ChrR-CLD (comprised of ChrR residues 86–213) that are conserved across 73 predicted homologues 17. One set of these variant ChrR proteins contained alanine substitutions at conserved amino acid residues that function as zinc ligands in the wild type ChrR-CLD (His141, His143, Glu147 or His177). We also tested the function of ChrR variants with either alanine or serine substitutions at Cys187 or Cys189. Combined, these variant ChrR proteins contain single amino acid substitutions in six of the ten conserved residues in the CLD across 73 predicted homologues of this anti-σ factor (the other conserved residues being glycine residues and one proline residue).

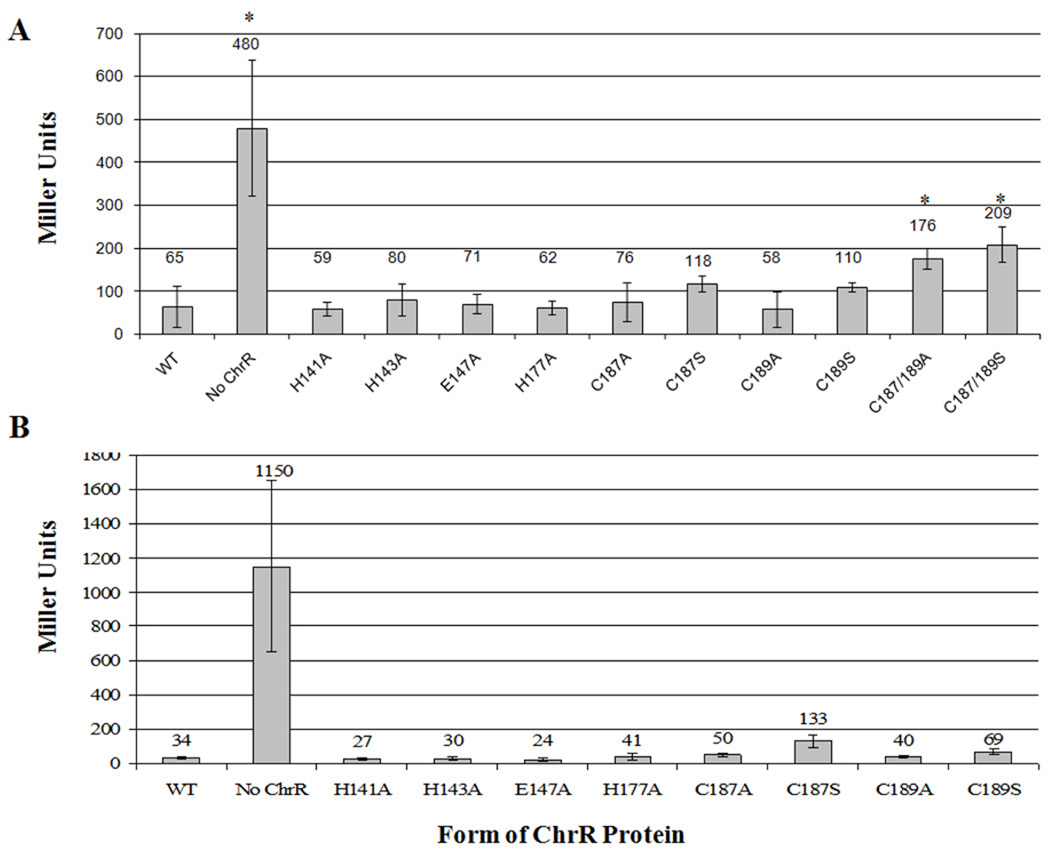

We first tested the ability of these variant ChrR proteins to inhibit σE activity in an Escherichia coli reporter strain that contains a σE-dependent promoter fused to lacZ 13–14, 21. We did not expect single substitutions in the ChrR-CLD to affect this activity since loss of the entire CLD did not prevent the ChrR-ASD from inhibiting σE 17. As predicted, when β-galactosidase activity was measured in this E. coli reporter strain we found that each of the ChrR proteins with single alanine substitutions in any of these six residues inhibited σE activity (Figure 2A). Thus, single alanine substitutions at these positions do not block the ability of ChrR to inhibit σE activity. It was also not surprising that single alanine substitutions at Cys187 or Cys189 allowed these variant ChrR proteins to inhibit σE activity since proteins containing individual serine substitutions at the same positions were previously shown to function as anti-σ factors 21. A variant ChrR protein containing alanine at both Cys187 and Cys189 was unable to inhibit σE as effectively as wild-type ChrR in this tester strain (Figure 2A), a result that was similar to that obtained when a ChrR variant contained serine substitutions at both positions 21. Thus, it appears that replacement of both Cys187 and Cys189 with alanine or serine 21 blocks the ability of ChrR to inhibit σE. One explanation for the behavior of the variant ChrR proteins with amino acid substitutions at both of these cysteine residues is that these proteins are in a conformation that favors complex dissociation rather than complex association. In contrast, variant ChrR proteins containing single alanine or serine substitutions at the cysteine residues in the ChrR-CLD are functional as anti-σ factors in this E. coli tester strain (Figure 2A).

Fig. 2. Amino acid substitutions in the ChrR-CLD do not block the ability of variant ChrR proteins to inhibit σE activity in vivo.

ChrR proteins with the indicated amino acid substitutions were tested for their ability to inhibit σE activity in E. coli (Panel A) or R. sphaeroides (Panel B). σE activity was monitored by measuring β-galactosidase activity (expressed as Miller units) from an rpoE∷lacZ operon fusion that requires this sigma factor for transcription 13–14,21.

In agreement with their behavior in E. coli, each of the singly-substituted variant ChrR proteins inhibited σE activity in R. sphaeroides though the strain expressing ChrR-C187S has somewhat higher σE activity than each of the other ChrR variants (Figure 2B, see below).

We recognize that a failure to accumulate σE/ChrR complexes containing the variant ChrR proteins could also formally explain the low levels of σE-dependent reporter gene activity. To test if the ChrR variants and σE were accumulated in R. sphaeroides, Western blot analysis was performed using a polyclonal antibody that recognizes both σE and ChrR. This analysis showed that σE and the variant ChrR proteins were accumulated in these strains (Figure 3). We conclude that each of the variant ChrR proteins containing these single amino acid substitutions in the ChrR-CLD functioned as anti-σ factors in R. sphaeroides. Thus, any effect on σE activity that we observe when cells expressing these variants are exposed to 1O2 can be attributed to the role of the corresponding amino acid in dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes.

Fig. 3. Accumulation of σE and ChrR proteins in R sphaeroides.

Shown is a Western blot analysis of cells containing either a wild type (WT) rpoEchrR operon or one that encodes the indicated variant ChrR protein as their only source of these proteins on a low-copy plasmid. The Western blot monitors accumulation of both σE (apparent MW ∼21kDa) and ChrR (apparent MW ∼23kDa; see arrows) since the antibody was raised against purified σE/ChrR complexes. Arrows indicate migration of known samples of σE and ChrR. Sizes were estimated by running protein molecular weight standards.

Amino acid side chains that ligate zinc in the ChrR-CLD are required for 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes

For those variant ChrR proteins that retained their ability to function as anti-σ factors, we tested whether 1O2 promoted dissociation of the corresponding σE/ChrR complexes. To test the ability of 1O2 to stimulate the σE-dependent transcriptional response in R. sphaeroides, we measured the differential rates of β-galactosidase synthesis from a σE-dependent rpoE P1∷lacZ reporter fusion prior to and during exposure to 1O2 12. We found that R sphaeroides cells containing a wild-type ChrR protein had a low rate of β-galactosidase synthesis from this reporter gene in the absence of 1O2 but, as expected 12, this rate increased (∼8 to 11-fold) after 1O2 exposure (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE-ChrR complexes in cells containing amino acid substitutions in the ChrR-CLD in vivo1.

| Photosynthetic to Aerobic Shift | Aerobic Cultures Treated with Methylene Blue | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChrR Protein |

Before 1O2 |

During 1O2 |

Fold Change |

Before 1O2 |

During 1O2 |

Fold Change |

| WT | 12 ± 1 | 76 ± 16 | 6.3 | 8 ± 2 | 81 ± 8 | 10.0 |

| None | 1529 ± 389 | 1208 ± 30 | 0.8 | 1285 ± 106 | 789 ± 174 | 0.6 |

| H141A | 16 ± 2 | 23 ± 6 | 1.4 | 25 ± 7 | 20 ± 3 | 0.8 |

| H143A | 28 ± 14 | 21 ± 5 | 0.8 | 25 ± 6 | 19 ± 5 | 0.8 |

| E147A | 14 ± 1 | 15 ± 4 | 1.0 | 19 ± 7 | 12 ± 3 | 0.6 |

| H177A | 35 ± 1 | 24 ± 8 | 0.7 | 39 ± 5 | 25 ± 10 | 0.6 |

| C187A | 38 ± 14 | 97 ± 9 | 2.5 | 38 ± 6 | 98 ± 1 | 2.5 |

| C189A | 27 ± 7 | 134 ± 41 | 5.0 | 34 ± 5 | 223 ± 9 | 6.6 |

| C187S | 109 ± 19 | 112 ± 10 | 1.0 | 72 ± 19 | 279 ± 64 | 3.9 |

| C189S | 39 ± 13 | 212 ± 15 | 5.4 | 47 ± 15 | 561 ± 67 | 11.9 |

Shown are the differential rates of β-galactosidase synthesis measured from an rpoE∷lacZ operon fusion that requires σE in cells containing the indicated ChrR protein as their sole source of this anti-σ factor before or during exposure to 1O2. The column labeled fold change reports the ratio of these rates during and before exposure to 1O2. The left half of the table shows data obtained when 1O2 was generated by exposing photosynthetically grown cells to 30% oxygen in the presence of light (10W/m2). The right half of the table shows data obtained when 1O2 was generated by adding light and methylene blue (1µM) to aerobically grown cells (30% oxygen).

When we tested the effect of 1O2 on cells containing variant ChrR proteins with single alanine substitutions at each of the four amino acid residues that function as zinc ligands in the ChrR-CLD (H141A, H143A, E147A and H177A), we saw no significant increase in the rate of β-galactosidase synthesis regardless of whether this reactive oxygen species was generated from methylene blue or the photosynthetic apparatus (Table 1). In the absence of 1O2, R. sphaeroides cells expressing the H143A or H177A variant ChrR proteins reproducibly have a slightly higher basal rate of σE activity compared to those containing wild-type ChrR, suggesting there is less binding of these variant proteins to σE. Regardless, there is no increase in σE activity when cells expressing the H141A, H143A, E147A or H177A variant ChrR proteins are exposed to 1O2. Thus, we conclude that 1O2 is unable to inactivate ChrR proteins containing an alanine at any one of the four amino acid residues that ligate zinc in the ChrR-CLD (His141, His143, Glu147 or His177).

Loss of one amino acid side chain involved in zinc binding in the ChrR-CLD does not prevent zinc occupancy

If zinc binding to the ChrR-CLD were required for 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, then loss of metal binding by variant ChrR proteins with alanine substitutions in these ligands might explain the inability of this reactive oxygen species to elicit the σE-dependent transcriptional response. To test this hypothesis, we purified σE/ChrR complexes containing each of these variant ChrR proteins and measured their zinc content by two assays (ICP-MS or PCMB/PAR). We know that the zinc atom in the ChrR-CLD can be removed by dialysis in the presence of DTT 17, so the metal content of the σE/ChrR complexes was analyzed both under conditions where ChrR should contain only a single (N-terminal) zinc (purification and subsequent dialysis in buffers containing DTT) as well as under conditions where the ChrR-CLD binds zinc (purification and subsequent dialysis in buffers lacking DTT) 17.

We found that σE/ChrR complexes containing either wild type or the H141A, H143A, E147A or H177A ChrR proteins contained the expected ∼1 molar equivalent of zinc per mole of complex when treated with DTT (Table 2). Thus, we conclude that none of the single amino acid substitutions in zinc ligands of the ChrR-CLD has a strong effect on binding of the essential zinc atom in the ChrR-ASD. This was not surprising because deleting the entire ChrR-CLD has no effect on zinc occupancy of the ChrR-ASD 17. As expected, we found that σE/ChrR complexes containing a wild-type ChrR protein contained a second zinc atom if samples were prepared in the absence of DTT (Table 3–2). Surprisingly, we found that σE/ChrR complexes containing variant ChrR proteins with single alanine substitutions at the zinc ligands contained a second zinc atom when they were prepared in the absence of DTT (Table 2). Thus, the failure of 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes containing single alanine substitutions in the zinc ligands of the ChrR-CLD is not due to the inability of these variant ChrR proteins to bind zinc.

Table 2.

Zinc content of σE-ChrR complexes containing wild-type or variant ChrR proteins1

| ChrR Protein |

+ DTT |

− DTT |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 1.0 ± 0.4 (1) | 1.9 ± 0.2 (2) |

| H141A | 1.0 ± 0.2 (1) | 2.1 ± 0.4 (2) |

| H143A | 1.2 ± 0.3 (1) | 1.6 ± 0.2 (2) |

| E147A | 1.0 ± 0.4 (1) | 2.1 ± 0.5 (2) |

| H177A | 1.0 ± 0.3 (1) | 1.8 ± 0.7 (2) |

| C187A | 0.9 ± 0.2 (1) | 1.8 ± 0.2 (2) |

| C189A | 1.3 ± 0.4 (1) | 1.8 ± 0.3 (2) |

| C187S | 0.8 ± 0.3 (1) | 1.9 ± 0.3 (2) |

| C189S | 0.6 ± 0.1 (1) | 1.9 ± 0.1 (2) |

| CLD-HHE | 0.9 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.9 ± 0.3 (1) |

| CLD-HHH | 1.0 ± 0.2 (1) | 1.1 ± 0.2 (1) |

Ratio of the zinc per σE/ChrR complex (expressed as moles of metal per mole of σE/ChrR complex) after samples containing the indicated ChrR protein were dialyzed against buffer with or without dithiothreitol (DTT). The numbers in parentheses indicate the ratio of zinc per σE/ChrR complex to the nearest whole number. CLD-HHE: ChrR variant with alanine substitutions at His141, His143, and Glu147. CLD-HHH: ChrR variant with alanine substitutions at His141, His143, and His177.

Table 3.

Apparent dissociation constants (Kd) for the dialyzable zinc in σE/ChrR complexes containing wild type or variant ChrR proteins1

| ChrR Protein |

Kd (M) |

Relative Affinity |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 4.6 × 10−10 | 1.00 |

| H141A | 9.7 × 10−10 | 0.48 |

| H143A | 5.6 × 10−9 | 0.08 |

| E147A | 1.6 × 10−8 | 0.03 |

| H177A | 5.1 × 10−9 | 0.09 |

| C187A | 3.9 × 10−10 | 1.16 |

| C189A | 3.9 × 10−10 | 1.16 |

| C187S | 5.1 × 10−9 | 0.09 |

| C189S | 1.1 × 10−9 | 0.04 |

Apparent Kd values were calculated based on the dissociation constant of Zinbo-5 (Kd = 1.3 × 10−9 M), as described in materials and methods. Values in “Relative Affinity” column were calculated by dividing Kd value of σE/ChrR complexes containing wild type ChrR to those measured for those containing the indicated variant ChrR protein. Experiments were conducted in three separate trials with separate protein preparations. Results shown are representative data from one experimental trial. In each trial, similar trends in relative affinity for zinc were observed between samples.

Other proteins that contain four-coordinate zinc binding sites, including the ChrR-ASD, can often bind a metal if one of the protein ligands is removed 17, 21–23. However, in these cases loss of one of the four protein ligands can alter the zinc-protein interactions. Consequently, we tested if any of the single amino acid substitutions in the zinc ligands of the ChrR-CLD altered the apparent dissociation constant of this domain for zinc.

To do this, we used a zinc-specific chelator to measure the apparent dissociation constant (Kd) for zinc from σE/ChrR complexes containing two moles of zinc under conditions where the zinc in the ChrR-ASD is not removed 24. Under these conditions, we measured a Kd for the zinc in the wild-type ChrR-CLD of ∼4.6 × 10−10 M (Table 3). It has been noted previously that dithiothreitol (DTT), commonly used as a reductant, can act as a metal chelator and has a Kd for transition metals, including zinc, of ∼10−10 M 25–27. Thus, the measured Kd for zinc in the CLD of wild type ChrR explains why this metal is removed from this domain during dialysis against buffers containing DTT. When compared to wild-type ChrR, the measured Kd for zinc in the ChrR-CLD of σE/ChrR complexes containing the H141A protein was ∼2-fold higher, suggesting that loss of this imidazole side chain did not have a large effect on metal binding affinity (Table 3).

In contrast, σE/ChrR complexes containing the H143A, E147A or H177A variant ChrR protein had apparent dissociation constants for zinc that were over 10-fold higher than that of the wild type protein, implying that these substitutions weakened the affinity of this domain for zinc (Table 3). As a control, we assayed zinc occupancy of variant ChrR proteins containing multiple alanine substitutions in the zinc ligands: H141A–H143A–E147A (CLD-HHE) and H141A–H143A–H177A (CLD-HHH). In both the CLD-HHE and CLD-HHH ChrR proteins, we were unable to detect binding of a second zinc atom, presumably because zinc coordination in the ChrR-CLD is dramatically altered by loss of three ligands (Table 2). Therefore, the observed zinc binding to the CLD variants with single amino acid substitutions in individual ligands does not reflect non-specific metal association.

When these observations are considered together, we conclude that multiple substitutions in the zinc site of the ChrR-CLD are needed to abolish metal binding, and that the H141A, H143A, E147A and H177A ChrR proteins are capable of specific, albeit weakened in some cases, zinc coordination. The data also indicate that the inability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of the corresponding σE/ChrR complexes was not correlated with a loss of metal binding, as the H141A variant coordinates zinc with an affinity for zinc only two-fold higher than the wild type protein (Table 3) but cells expressing H141A exhibited no detectable activation of σE-dependent transcription in the presence of 1O2 (Table 1). From studies probing the interaction of 1O2 with model compounds, this reactive oxygen species can modify imidazole rings 8, 28. Thus, it is possible that one or more of the individual alanine substitutions in the ChrR-CLD zinc ligands alter either the number or nature of zinc ligands and lead to a defect in the ability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes even though these variant ChrR proteins can still bind metal (see Discussion).

The conserved cysteine residues in the ChrR-CLD are not required for 1O2 to induce σE activity

Studies probing the interaction of 1O2 with model compounds, including individual amino acids, have shown that thiols are also subject to rapid oxidation by this reactive oxygen species 7–8, 29–32. Variant ChrR proteins form a complex with σE when either of the two conserved cysteines (residues 187 or 189) is changed to alanine or serine (Figure 2). Consequently, we also tested the ability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of the σE/ChrR complexes containing variant ChrR proteins with substitutions at these conserved cysteine residues in the ChrR-CLD.

When we assayed the ability of 1O2 to stimulate the σE-dependent transcriptional response, cells expressing C187A showed a ∼2.5 fold increase in σE activity during exposure to 1O2, which is ∼3–6 times lower than that observed (8- to 11-fold increase) when wild-type cells are exposed to 1O2 (Table 1). Similarly, when cells containing a variant ChrR protein with a serine substitution at Cys187 were exposed to 1O2, there is only a 1- to 4-fold increase in σE activity. The decreased fold increase in σE activity in cells containing the C187A or C187S variant ChrR proteins reflects a higher rate of β-galactosidase synthesis from this reporter gene in the absence of 1O2 (Table 1). Thus, the loss of the cysteine side chain in the C187A or C187S variant ChrR proteins appears to alter the ability of these proteins to form a complex with σE in vivo (see Discussion). Thus, the data suggests that the thiol side chain at Cys187 does not necessarily play a role in stimulating the σE-dependent response in vivo.

We found that cells containing ChrR C189A or C189S variant proteins exhibited a greater fold increase in the rate of β-galactosidase synthesis after exposure to 1O2 compared to cells expressing C187A, C187S or wild type ChrR (Table 1). Cells expressing the C189A variant increase σE activity 5- to 7-fold and cells expressing the C189S variant increase activity 5- to 11-fold (compared to the wild type rate increase of 8- to 11-fold). The increase in β-galactosidase synthesis rates observed in cells containing variant ChrR proteins with alanine or serine substitutions at Cys189 suggest that this side chain has no significant negative effect of the ability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of this σE/ChrR complex. Indeed, the rate of β-galactosidase synthesis observed in cells when exposed to 1O2 is 3- to 7-fold higher in cells containing the C189A or C189S ChrR variants than that found in strains containing wild type ChrR (Table 1), suggesting that these substitutions render the resulting σE/ChrR complexes more susceptible to dissociation when cells are exposed to 1O2. In summary, evidence suggests that neither cysteine side chain in the ChrR-CLD is essential for 1O2 to promote dissociation of the corresponding σE/ChrR complexes in vivo, suggesting that oxidation of these cysteine thiols is not a driving force in the dissociation. This suggestion is supported by our ability to modify two thiols with 5-5′’-Dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), a sulfhydryl-modifying agent 33, before and after wild-type σE/ChrR complexes are exposed to 1O2 (data not shown). The side chains of Cys187and Cys189 are the only free thiols in the σE/ChrR complex 17, so it appears that these thiols are not direct targets for modification when pure σE/ChrR complexes are exposed to 1O2 in vitro. However, the nature of the side chain at positions 187 and 189 play some role in dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, since single serine substitutions at each residue have a higher rate of β-galactosidase synthesis relative to wild type when cells are exposed to 1O2.

Amino acid substitutions at Cys187 or Cys189affect zinc binding to the ChrR-CLD

When we analyzed zinc occupancy of σE/ChrR complexes with alanine or serine substitutions at either Cys187 or Cys189, the metal content of these variants were indistinguishable from the wild-type ChrR protein (Table 2). These results were not surprising given that these cysteine side chains are over 12 Å away from the zinc site in the ChrR-CLD and thus were not expected to have a direct role in zinc coordination 17. However, we were surprised to find that the apparent affinity for the C-terminal zinc of σE/ChrR complexes containing the C187S or C189S proteins was reduced ∼10- to 20-fold compared to one containing a wild type ChrR protein (Table 3). Given the distance of these side chains from this metal site, we propose that the reduced affinity of σE/ChrR complexes containing the C187S or C189S proteins for zinc in the ChrR-CLD is an indirect effect of the amino acid substitutions. The effects of these substitutions on zinc affinity in vitro coupled with the in vivo effects observed in cells expressing these variants when exposed to 1O2 will be incorporated into a working model for how 1O2 promotes dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes (see Discussion).

The ability of other agents to promote dissociation of R. sphaeroides σE/ChrR complexes

It was recently shown that activity of the C. crescentus σE homologue is increased by treating cells with 1O2, the organic hydroperoxide t-BOOH, or cadmium 20. Consequently, we sought to determine whether treatment of R. sphaeroides with t-BOOH or cadmium would promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes.

To do this, we tested if activity of the σE-dependent reporter gene was increased when wild type R. sphaeroides cells were exposed to either cadmium or t-BOOH. When aerobically grown R. sphaeroides cells were treated with 20 µM, 100 µM, or 1 mM CdSO4 for up to 3 hours, no increase in the rate of β-galactosidase synthesis from this reporter gene was observed (Table 4), unlike what is found in C crescentus where addition of 25 µM exogenous cadmium increased σE activity ∼2.5-fold 20. In contrast, the addition of 100 µM t-BOOH increased the rate of β-galactosidase synthesis from this σE-dependent reporter gene in either wild type cells (Table 4) or cells containing a wild type copy of ChrR as their only source of this anti-σ factor (Table 5). Thus, t-BOOH but not cadmium is able to promote dissociation of R. sphaeroides σE/ChrR complexes in vivo, suggesting there are differences between the behavior of this system in this bacterium and C. crescentus (see Discussion).

Table 4.

Effects of t-BOOH or cadmium on dissociation of σE-ChrR complexes in vivo1

| Cadmium (µM) |

Before Cadmium |

After Cadmium |

Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 1.8 | 1.1 |

| 20 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 100 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | 1.2 |

| 1000 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 0.9 |

| t-BOOH (µM) |

Before t-BOOH |

After t-BOOH |

Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 17.6 ± 0.9 | 3.9 |

Shown are the differential rates of β-galactosidase synthesis measured from an rpoE∷lacZ operon fusion that requires σE in wild type R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 cells before or after addition of the indicated concentration of cadmium sulfate or t-BOOH. The column labeled fold change reports the ratio of these rates before and after cadmium sulfate addition.

Table 5.

Ability of t-BOOH to promote dissociation of σE-ChrR complexes containing wild type or variant ChrR proteins in vivo1.

| ChrR Protein |

Before t-BOOH |

After t-BOOH |

Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 19 ± 3 | 173 ± 64 | 9.1 |

| ChrR85 | 34 ± 6 | 45 ± 7 | 1.3 |

| H141A | 25 ± 2 | 44 ± 9 | 1.7 |

| H143A | 31 ± 4 | 38 ± 2 | 1.2 |

| E147A | 20 ± 4 | 25 ± 6 | 1.3 |

| H177A | 40 ± 8 | 50 ± 9 | 1.3 |

| C187A | 44 ± 6 | 82 ± 14 | 1.9 |

| C189A | 27 ± 8 | 64 ± 12 | 2.4 |

| C187S | 109 ± 26 | 256 ± 75 | 2.3 |

| C189S | 60 ± 9 | 262 ± 83 | 4.4 |

Shown are the differential rates of β-galactosidase synthesis measured from an rpoE∷lacZ operon fusion that requires σE in cells containing the indicated ChrR protein as their sole source of this anti-σ factor before or after addition of 100 µM t-BOOH. The column labeled fold change reports the ratio of these rates before and after addition of 100 µM t-BOOH.

To further analyze aspects of ChrR required for t-BOOH to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, we tested the ability of this compound to increase target gene activity in cells containing variant ChrR proteins. We found that the rate of β-galactosidase synthesis cells containing the truncated ChrR85 protein was not increased in the presence of 100 µM t-BOOH (Table 5). From this, we conclude that the ChrR-CLD was required for t-BOOH to promoter dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes.

Since the ChrR-CLD is needed for both 1O2 and t-BOOH to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, we also tested the ability of this organic hydroperoxide to alter activity of the σE-dependent target gene in cells containing variant ChrR proteins with single amino acid substitutions in the CLD. We found that the rate of the rate of β-galactosidase synthesis in cells containing either the H141A, H143A, E147A or H177A variant ChrR proteins was the comparable before and after addition of 100 µM t-BOOH. From this we conclude that the histidine or glutamate side chains at these positions in wild type ChrR are required for t-BOOH in promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes, similar to what was found when cells containing these variant ChrR proteins were exposed to 1O2 (Table 1). We also found that replacing the cysteine residue at ChrR positions 187 or 189 with either a serine or an alanine produced similar effects on dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes in cells containing each of these variant proteins in the presence of t-BOOH (Table 5) as was found with 1O2 (Table 1). Thus, it appears that there are similar effects of these single amino acid substitutions in the ChrR-CLD in the presence of 1O2 and t-BOOH (see Discussion).

Discussion

1O2 is one of several reactive oxygen species that can destroy biomolecules and kill cells 7–10, 28–29, 34–38. Prokaryotes and eukaryotes mount a transcriptional response to 1O2 12, 15, 36–37, 39–40 but little is known about the mechanisms by which these responses are initiated. Previous work has shown that the transcriptional response to 1O2 in R. sphaeroides is regulated by ChrR, a zinc metalloprotein which forms a complex with the Group IV sigma factor, σE, that prevents this sigma factor from binding RNA polymerase in vitro 12–13, 17, 21. However, it was not known whether 1O2 activated the σE-dependent transcriptional response by promoting disassociation of σE/ChrR complexes or by preventing newly-synthesized ChrR from forming this inhibitory complex with σE. We found that 1O2 stimulated the σE-dependent transcriptional response when cells were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor chloramphenicol. Since 1O2 was able to increase σE activity in the absence of de novo protein synthesis, we conclude that this reactive oxygen species somehow causes dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes to initiate the transcriptional response. Stimulatory signals cause dissociation of complexes between other Group IV sigma factors and their cognate anti-a factors 22, 41–49. Thus, the process by which 1O2 stimulates the σE-dependent transcriptional response is similar to that used for increasing activity of many Group IV sigma factors. In many cases, the inducing signal activates one or more proteases and stimulates turnover of the anti-a factor 43–45. This appears to be true for R. sphaeroides σE/ChrR as well, since the presence of either 1O2 or t-BOOH promotes to turnover of the anti-σ factor ChrR (Nam, unpublished). However, the mechanism and other proteins needed for these inducers to stimulate dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes are unknown.

Previous work demonstrated that ChrR is composed of an N-terminal domain that is sufficient for binding σE and a C-terminal cupin-like domain (CLD) that is needed for 1O2 to promote this transcriptional response in vivo 17. To acquire insight into how 1O2 might stimulate release of σE from ChrR, we tested the role of six conserved amino acids (His141, His143, Glu147, His177, Cys187 and Cys189) in the ChrR-CLD for a role in the σE -dependent transcriptional response to 1O2. While little is known about the reactivity of 1O2 with proteins, each of these amino acids is conserved in 73 ChrR homologues and studies with amino acids or model compounds predict that cysteine and histidine side chains are potential sites of modification by this reactive oxygen species 7, 29, 32, 38, 50.

We found that 1O2 was unable to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes containing variant ChrR proteins with single alanine substitutions at His141, His143, Glu147, or His177, the amino acid side chains that comprise the 4-coordinate zinc binding site in the wild type ChrR-CLD. It was possible that a defect in metal binding could explain the inability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes containing alanine substitutions at these residues. When studies were performed on the response of a Caulobacter crescentus σE/ChrR homologue to 1O2 and other agents, the authors found that 1O2 was unable to increase target gene expression in cells containing variant proteins with alanine substitutions at the analogous positions of the CLD 20. Based on this data and amino acid similarity to the R. sphaeroides ChrR protein, it was proposed that the C. crescentus ChrR protein may be able to coordinate zinc at the analogous residues. However, it was recognized that further studies were needed to determine if there is a physiological role for this C-terminal zinc in the ChrR-dependent response in either organism 20. Unfortunately, no experiments had been performed in the C. cresentus study to monitor zinc binding of mutant ChrR proteins relative to the wild type protein.

Indeed, our data indicate that the inability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of complexes containing these variant R. sphaeroides ChrR proteins (H141A, H143A, E147A, or H177A) is not associated with a defect in zinc occupancy in the CLD since all four of these σE/ChrR complexes bound zinc when purified (Table 3–2). In addition, the CLD of the H141A ChrR protein binds zinc with an affinity within 2-fold of that of its wild type counterpart and the CLD of the H143A, E147A and H177A ChrR proteins each had an affinity for zinc in vitro that was 10- to 20-fold higher relative to wild type (Table 3). Thus, previous predictions that the zinc atom in the ChrR-CLD was somehow linked to the σE-dependent transcriptional response 17 seem unlikely since 1O2 was unable to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes containing variant ChrR proteins that have affinities for zinc comparable to a wild type protein. Instead, our data support a model in which zinc binding by the ChrR-CLD is not necessary for 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes. However, it is likely that the H141A, H143A, E147A, or H177A substitutions shift the number of protein ligands to the zinc in the ChrR-CLD from 4 to 3, so it is possible that features of the zinc-protein interaction are needed for 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes.

This model is not contradicted by the observation that the C187S and C189S ChrR variants, which allow cells to respond to 1O2, have an effect on the ChrR-CLD zinc affinity even though these side chains are ∼12 Å from this metal. The C187S and C189S ChrR variants exhibit a 20-fold higher affinity for zinc relative to wild type but cells expressing C187S or C189S can still increase σE activity when exposed to 1O2. The changes in zinc affinity for the C187S and C189S ChrR proteins also indicate that these amino acid substitutions exert an effect on the properties of the zinc binding site in the ChrR-CLD even though these substitutions are not in proximity to the amino acid residues that coordinate this metal. When the metal binding properties and the ability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of the ChrR H141A, C187S and C189S proteins are considered together, it leads us to propose that the presence of zinc in the ChrR-CLD is not obligately linked to the ability of this reactive oxygen species to release σE.

Combining information from the 3-dimensional structure of the σE/ChrR complex 17 with data from this study allows us to refine previous models for how 1O2 triggers the σE-dependent transcriptional response to this reactive oxygen species. We propose that the chemical nature of the His141, His143, Glu147, or His177 side chains in the ChrR-CLD is required for 1O2 to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes. 1O2 is known to modify imidazole-containing compounds 7, 29, 32, 38, so proper positioning of one or more of these side chains in the ChrR-CLD is likely crucial for 1O2 to directly or indirectly promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes. The side chains of His141, His143, Glu147, or His177 (as well as Cys189) are each solvent-exposed on one face of the ChrR-CLD in the σE/ChrR structure (Figure 4B), so it is possible that modification of one or more of these side chains helps to initiate a conformational change in the ChrR-CLD that promotes dissociation of the σE/ChrR complex. Changes in the position of amino acid side chains within the ChrR-CLD brought about by alterations in the zinc coordination state could also explain why the H141A, H143A, E147A, or H177A amino substitutions prevented 1O2 from promoting dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes.

Fig. 4. Position of conserved amino acid residues in ChrR-CLD.

(A) Stereo view of three overlaid structures of the ChrR-CLD. In green is the structure of the ChrR-CLD that contains zinc, in peach and purple are two structures of the ChrR-CLD solved in the absence of zinc. Conserved amino acid residues investigated in this study are labeled and shown as stick figures, with backbone carbons color coded according to above scheme. Side chain atoms are colored as follows: nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; and sulfur, orange. Zinc is forest-green. (B) Space-fill model of the ChrR-CLD showing solvent-accessibility of the conserved residues. In green is the structure of the ChrR-CLD that contains zinc. Side chain atoms are colored as described above. This view shows the positions and accessibility of the side chains of His141, His143, Glu147, His177, and Cys189, as well as the zinc atom (colored in grey). Structure forms from crystals were accessed from the Protein Data Bank under ID codes 2Q1Z and 2Z2S.

Indeed, significant alterations in the positions of the His141, His143, Glu147 or His177 side chains, as well as Cys187, were observed between the 3-dimensional structures of σE/ChrR complexes that lacked or contained a C-terminal zinc even though the backbone positions of the ChrR-CLD were similar in these two complexes (maximum rmsd of 0.63 Å2 over 85 a-carbons in the ChrR-CLD; Figure 4A) 17.Thus, there is structural evidence for metal-dependent alterations in the positions of His141, His143, Glu147, and His177 side chains, and even at residues Cys187 or Cys189 that are ∼12Å away from the C-terminal zinc ligand 17. Cysteine thiols are modified by organic hydroperoxides 6, so it is possible that changes in the position of the Cys187 or Cys189 can alter the ability of these variant σE/ChrR complexes to respond to t-BOOH. However, experiments to determine how 1O2 or t-BOOH promotes dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes in vitro are needed to test the predictions of this model.

While this paper was being prepared, results of experiments to analyze the response of the C. crescentus σE/ChrR system to 1O2 and other stimuli were published 20. The C. crescentus σE/ChrR system can respond to 1O2, t-BOOH, UV-A radiation, and cadmium, though it was proposed that the mechanism by which cadmium induces σE activity is distinct from the other agents 20. We found that the R. sphaeroides σE/ChrR system also responds t-BOOH. However, σE activity is not induced when cells are exposed to concentrations of cadmium that activated C. crescentus σE activity. Thus, our data suggest there are differences in the response of R. sphaeroides σE/ChrR to cadmium when compared to other agents and between these two bacteria to this compound.

If we further compare the σE/ChrR systems of both organisms, we observe that neither R. sphaeroides Cys187 nor C. crescentus Cys186 are necessary for the σE-dependent transcriptional response to 1O2, as cells containing variant ChrR proteins with substitutions at either position induce a σE-dependent response to 1O2 similar to the wild-type σE/ChrR systems of each bacterium. While the ChrR-CLD cysteine residues are not important in either organism for promoting complex dissociation when cells encounter 1O2, in C. crescentus the cysteine residues are reported to be important for transient increases in σE activity when cadmium is added to cells 20. This does not appear to be the case in R. sphaeroides since the addition of 1mM cadmium sulfate did not promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes even in wild type cells.

It has been reported that addition of cadmium can deplete E. coli cells for zinc 51 and it is known that zinc limitation can increase R. sphaeroides σE activity 12, 52. However, if the concentrations of cadmium added in this study interfered with zinc homeostasis, and zinc limitation contributed to the ability of cadmium to increase σE activity, we would have observed increased σE activity in R. sphaeroides in cadmium-treated cells.

One obvious difference between the R. sphaeroides and C. crescentus ChrR proteins is that the latter homolog lacks side chains that coordinate zinc in the R. sphaeroides ChrR-ASD. We know that three of four zinc ligands in the R. sphaeroides ChrR-ASD (His6, Cys35, and Cys38) are essential for it to form a complex with and inhibit σE activity 17. Thus, the absence of zinc in the C. crescentus ChrR-ASD may allow the system to respond to alternate stimuli, such as cadmium, relative to R. sphaeroides ChrR, and vice versa. Further investigation is warranted to distinguish the mechanistic differences on the ability of 1O2 and other agents versus cadmium or other yet identified stimuli to promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes in vitro and in vivo between these homologous systems.

In summary, we have shown that 1O2 stimulates the σE-dependent transcriptional response by promoting dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes. We have also presented evidence that t-BOOH will increase σE activity in R. sphaeroides. Finally, we identified amino acid side chains in the ChrR-CLD that play important roles in the process by which 1O2 or t-BOOH promotes release of σE from ChrR. Our data indicate that the ability of 1O2 to promote dissociation of several variant σE/ChrR complexes is not linked to a failure of each anti-σ factor to bind zinc in the C-terminal CLD. We are currently developing systems to test the predictions of our results for how 1O2 and t-BOOH promote dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes. For example, experiments are in progress to test whether these reactive oxygen species chemically modify ChrR, if dissociation of σE/ChrR complexes caused by 1O2 or t-BOOH require additional proteins in vivo and in vitro, and how these and other amino acid changes in ChrR alter its structure and zinc-protein interactions in the CLD.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

E.coli strain VH1000 (ΦλJDN1), containing an rpoEP1∷lacZ fusion, was used to assay ChrR function in this host 13–14, 21. Plasmids were maintained in E. coli DH5α, E. coli S17-1 was used as a donor for plasmid conjugation into R. sphaeroides, and E. coli strains M15(pREP4) and BL21(DE3) were utilized for protein expression. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani growth media 53 supplemented with 100 µg/ml ampicillin, 25 µg/ml kanamycin, and/or 10 µg/ml tetracycline to maintain plasmids where necessary. R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 (wild type) and TF18 (ΔrpoEchrR-1∷drf) were grown at 30°C in Sistrom’s succinate-based minimal medium A 54. Media used for growth of R. sphaeroides strains containing low-copy rpoE P1∷lacZ reporter plasmids 14, 21, 55 were supplemented with 25 µg/ml kanamycin and 1 µg/ml tetracycline where necessary. R. sphaeroides strains grown by aerobic respiration were bubbled with 69% N2, 30% O2, and 1% CO2 in the dark. Photosynthetic cultures were grown by bubbling with 95% N2 and 5% CO2 using a light intensity of 10 W/m2 12. 1O2 was generated for experiments with R. sphaeroides as previously described 12, 17.

Mutagenesis of chrR

Variant ChrR proteins were generated via site-directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with chrR genes contained on plasmids pJDN48 21 or pLC37 17. Each mutant chrR gene was sequenced to confirm that only the desired change was present before testing ChrR function 13, 21. To determine if the variant ChrR proteins inhibited σE activity, β-galactosidase assays were performed in E. coli strain VH1000 (ΦλJDN1). To assay function of variant ChrR proteins in R. sphaeroides before or during exposure to 1O2, each mutant chrR gene was cloned into pJDN18, transformed into S17-1 and mated into R. sphaeroides strain TF18 containing the low-copy rpoEP1∷lacZ reporter plasmid, pJDN30 13, 21.

β-galactosidase Assays

β-galactosidase assays were performed as previously described. Data is presented in Miller units for experiments using E. coli 14 and R. sphaeroides when testing the ability of ChrR variants to inhibit σE activity, and as the differential rate of β-galactosidase synthesis to assay σE activity when R. sphaeroides cells were treated with 1O2 12,17.

Inhibition of Protein Synthesis

R. sphaeroides cultures were treated with chloramphenicol (Cm) to inhibit protein synthesis. To assay protein synthesis, 10 ml of exponential-phase R. sphaeroides cultures (∼2 × 108 cells/ml) were split, and one flask was treated with 200 µg/ml Cm for 15 min. After 15 min, 50 µCi of EasyTag EXPRE35S35S Protein Labeling Mix (Perkin-Elmer) was added to each culture for 1 min followed by a 2 min exposure to a mixture of 1 M cysteine and 1 M methionine. Ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (5% final concentration) was added, proteins were harvested by centrifugation (13,000 × g for 10 min), the supernatant was aspirated and the pellet washed twice with ice-cold 80% acetone. After evaporation of residual acetone, the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of TBS-Tween and radioactivity measured via a scintillation counter. The ratio of the 35S incorporated into acid-precipitable material in Cm-treated versus Cm-untreated cells was used to monitor protein synthesis. In three replicate experiments, treatment of R. sphaeroides with 200 µg/ml Cm for 15 min was 95% efficient at arresting protein synthesis.

Monitoring transcript levels before and during 1O2 exposure

RNA was isolated, with slight modification, as previously described 56. Photosynthetic R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 cultures (500 ml) were grown to a density of ∼2 × 108 cells per ml, and 25 ml samples were taken at time points prior to and during exposure to 1O2. To digest DNA, the samples were treated with RNase-free DNase (Sigma, Woodlands, TX) in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 50 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM DTT for 20 min at room temperature. The RNA was further purified using an RNeasy CleanUp kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was assayed (i.e., A260/A280 ratio ∼1.8–2.0) and quantitated spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE).

cDNA synthesis

For cDNA synthesis, 5 µg of RNA was mixed with 3 µl of random hexamer primers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a final volume of 30 µl. The mixture was incubated at 70°C for 10 min, then at 25°C for 1 hr. Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase and recommended buffers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were added, the mixture was incubated for 1 hr at 37°C, followed by 1 hr at 42°C. To digest the RNA after cDNA synthesis, 20 µl of 1N NaOH was added before placing samples at 65°C for 30 min. After 20 µl of 1N HCl was added, the cDNA was purified using a PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and resuspended in 30 µl of buffer. The concentrations of cDNA generated were quantitated spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE).

qRT-PCR

Real-time PCR was used to measure expression from known σE target genes (rpoE and RSP1409 12, 15) and rpoZ (encoding the Ω subunit of RNA polymerase) as a σE-independent control gene using a Bio-Rad iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Primers used were: rpoZ forward (5’-TTG AAG ACT GCG TTG ACA AGG TCC-3’),rpoZ reverse (5’-GTT CTT GTC ATT GTC GCG GTC GAT-3’), rpoE 110F (5’-TGA AGG GCT TCC TGA TGA AAT CCG-3’), rpoE 210R (5’- ATC GAA GAG ATG AGC CTT CTG CCA-3’), RSP_1409F (5’- GAT CTG CTG AAG CCC GAG AAC AAG-3’), and RSP_1409R (5’- CTT CCG TCA GAT CCG AGG ACA TCA-3’). Triplicate assays were performed in reactions containing 12.5 µl of the IQ SYBR Green Super-mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), 20 ng of cDNA (diluted to 4ng/µl), 5 pmol of each primer, and water to 25 µl. The PCR cycling conditions were: denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C. To assay amplification products for each target gene, a melting curve was generated by treating for 1 min at 95°C, then incubating at 55°C for 1 min and increasing the temperature 0.5°C every 10 s up to 95°C. Real-time PCR efficiencies were determined by 5-fold serial dilutions of the cDNA template from 20 ng down to 0.16 ng. Data were analyzed by comparative Ct method 57. To report the relative change in RNA abundance, the value was compared to that prior to the generation of 1O2 stress (time equals zero).

Analysis of purified σE/ChrR complexes

σE/ChrR complexes containing one or two zinc atoms per complex were prepared as previously described 17. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assays 58. To assay metal content of σE/ChrR complexes, samples were either analyzed by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS; UW Soil and Plant Analysis Lab, Madison, WI, and Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene, Madison, WI) or spectrophotometrically via a 4-(2-pyridylazo) resorcinol (PAR) assay 21 using the organomecurial agent p-chloromercuribenzoic acid (PCMB) to form mercaptide bonds with cysteine residues and ensure the release of all zinc atoms from ChrR denatured by guanidine-HCl (described below).

Zinc Affinity Measurements

Total zinc content ([ChrRtotalZn]) was determined after treating σE/ChrR complexes (5 µM) with guanidine hydrochloride and PCMB (10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 40 µM PCMB, 4.5 M guanidine hydrochloride), incubating with 200 µM PAR at 70 °C for 20 min, and measuring A490 as an indicator of zinc binding to PAR. Zinc occupancy was calculated by comparing the sample A490 to ZnSO4 standards in the same buffer. The apparent dissociation constants for the dialyzable zinc in σE/ChrR complexes were estimated by competition with the fluorescent zinc competitor Zinbo-5 (2-(4,5-Dimethoxy-2-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(2-pyridylmethyl)aminomethylbezoxazole) 24. To determine the apparent dissociation constants, σE/ChrR complexes (2.5 µM – 5 µM) were incubated in 50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and Zinbo-5 (2.5 µM – 5 µM) for 10 min at 23 °C. Zinc binding by Zinbo-5 (as assessed by increases in A376) reached equilibrium within 5 min, while incubations longer than 15 min caused protein aggregation. The extinction coefficient of Zinbo-5 in this buffer was determined by measuring the absorption of 5 µM Zinbo-5 incubated with increasing concentrations of ZnSO4 at 376 nm, and calculated values (ε = 1.70 × 104- 2.10 × 104 M−1 cm−1 ) were consistent with the previously published value (ε =1.9 × 104 M−1 cm−1) 24. After the concentration of zinc-bound Zinbo-5 was measured, the concentration of free Zinbo-5 ([Zinbo-5free] = [Zinbo-5total] – [Zinbo-5·Zn]) was determined. Assuming that the N-terminal Zn in the ChrR ASD is not released in the presence of Zinbo-5, concentrations of ChrR with 2 Zn ([ChrR·Zn2] = [ChrRtotalZn] – [ChrRtotal] – [Zinbo-5·Zn]) or 1 Zn ([ChrR·Zn] = [ChrRtotal] – [ChrR· Zn2]) were calculated. Based on the published dissociation constant of Zinbo-5 at pH 7.2 with 100 mM ionic strength (KD = 1.3 × 10−9 M) 24, the binding constant of the dialyzable zinc in ChrR was calculated according to the equation below:

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins from exponential-phase cells (∼2 × 108 cells/ml) expressing wild type or variant ChrR proteins were collected by TCA precipitation (5% final concentration, see above). Precipitated proteins were resuspended in 100 µl of 1X LDS loading dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 20µl of each sample was loaded onto a NuPAGE acrylamide gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) that was run in 1X MES running gel at 130 volts for ∼90 min. Proteins were transferred to a charged Invitrolon PVDF membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using a Hoefer Mighty Small Transfer Tank (Hoefer, Holliston, MA) at 200 mA for 3 hr. The membranes were incubated overnight in 1x TBS, 0.05% NP40, and 6% milk protein before being incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against σE/ChrR complexes (Cocalico Biologicals, Reamstown, PA). A goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was used for detection using a Pierce ECL Western Blot Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Treatment of cells with t-BOOH or cadmium

To determine if addition of t-BOOH or cadmium would induce σE activity, β-galactosidase assays were performed in exponential phase aerobic cultures of either wild type R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 or TF18 (ΔrpoEchrR-1∷drf) cells containing a wild type or mutant chrR gene on a low copy plasmid (see above). For these experiments, cells were grown by shaking (10 ml in a 125 ml flask) and exposed to either the indicated concentrations of CdSO4 or 100 µM t-BOOH. Samples were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity from the low-copy rpoEP1∷lacZ reporter plasmid, pJDN30 13, 21 to calculate the differential rate of the β-galactosidase synthesis. Data shown are the averages of three separate cultures.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bethany Rader and Eva Ziegelhoffer for assistance with the qRT-PCR, and Margaret McFall-Ngai for use of the Bio-Rad iCycler. We would like to thank Tom O’Halloran for the Zinbo-5 reagent used for the zinc affinity measurements. We would also like to thank Ana Misic, Andrew Berti, Amber Pollack-Berti, Sarah Studer, Eva Ziegelhoffer, and Gary Roberts for their comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by grants DE-FG02-05ER15653 (DOE) and GM075273 (NIGMS) to TJD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Scandalios JG. Oxygen Stress and Superoxide Dismutases. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:7–12. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeilstra-Ryalls JH, Kaplan S. Oxygen intervention in the regulation of gene expression: the photosynthetic bacterial paradigm. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:417–436. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3242-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner PD. The biology of oxygen. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:887–890. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00155407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Flecha B, Demple B. Genetic responses to free radicals. Homeostasis and gene control. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;899:69–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mates JM. Effects of antioxidant enzymes in the molecular control of reactive oxygen species toxicology. Toxicology. 2000;153:83–104. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuangthong M, Helmann JD. The OhrR repressor senses organic hydroperoxides by reversible formation of a cysteine-sulfenic acid derivative. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6690–6695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102483199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clennan EL. Persulfoxide: key intermediate in reactions of singlet oxygen with sulfides. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:875–884. doi: 10.1021/ar0100879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies MJ. Reactive species formed on proteins exposed to singlet oxygen. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:17–25. doi: 10.1039/b307576c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies MJ. The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703:93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinalducci S, Pedersen JZ, Zolla L. Formation of radicals from singlet oxygen produced during photoinhibition of isolated light-harvesting proteins of photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1608:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cogdell RJ, Howard TD, Bittl R, Schlodder E, Geisenheimer I, Lubitz W. How carotenoids protect bacterial photosynthesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355:1345–1349. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anthony JR, Warczak KL, Donohue TJ. A transcriptional response to singlet oxygen, a toxic byproduct of photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6502–6507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502225102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anthony JR, Newman JD, Donohue TJ. Interactions between the Rhodobacter sphaeroides ECF sigma factor, σE, and its anti-sigma factor, ChrR. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:345–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman JD, Falkowski MJ, Schilke BA, Anthony LC, Donohue TJ. The Rhodobacter sphaeroides ECF sigma factor, σE, and the target promoters cycA P3 and rpoE P1. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:307–320. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dufour YS, Landick R, Donohue TJ. Organization and evolution of the biological response to singlet oxygen stress. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:713–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziegelhoffer EC, Donohue TJ. Bacterial responses to photo-oxidative stress. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:856–863. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell EA, Greenwell R, Anthony JR, Wang S, Lim L, Das K, Sofia HJ, Donohue TJ, Darst SA. A conserved structural module regulates transcriptional responses to diverse stress signals in bacteria. Mol Cell. 2007;27:793–805. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunwell JM, Culham A, Carter CE, Sosa-Aguirre CR, Goodenough PW. Evolution of functional diversity in the cupin superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:740–746. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01981-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunwell JM, Purvis A, Khuri S. Cupins: the most functionally diverse protein superfamily? Phytochemistry. 2004;65:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lourenço RF, Gomes SL. The transcriptional response to cadmium, organic hydroperoxide, singlet oxygen and UV-A mediated by the σE-ChrR system in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:1159–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman JD, Anthony JR, Donohue TJ. The importance of zinc-binding to the function of Rhodobacter sphaeroides ChrR as an anti-sigma factor. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:485–499. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paget MS, Bae JB, Hahn MY, Li W, Kleanthous C, Roe JH, Buttner MJ. Mutational analysis of RsrA, a zinc-binding anti-sigma factor with a thiol-disulphide redox switch. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1036–1047. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemba M, Regan L. Characterization of metal binding by a designed protein: single ligand substitutions at a tetrahedral Cys2His2 site. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10094–10100. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taki M, Wolford JL, O’Halloran TV. Emission ratiometric imaging of intracellular zinc: design of a benzoxazole fluorescent sensor and its application in two-photon microscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:712–713. doi: 10.1021/ja039073j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cornell NW, Crivaro KE. Stability constant for the zinc-dithiothreitol complex. Anal Biochem. 1972;47:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90293-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gracy RW, Noltmann EA. Studies on phosphomannose isomerase. II. Characterization as a zinc metalloenzyme. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:4109–4116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krezel A, Lesniak W, Jezowska-Bojczuk M, Mlynarz P, Brasun J, Kozlowski H, Bal W. Coordination of heavy metals by dithiothreitol, a commonly used thiol group protectant. J Inorg Biochem. 2001;84:77–88. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies MJ. Singlet oxygen-mediated damage to proteins and its consequences. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:761–770. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright A, Bubb WA, Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. Singlet oxygen-mediated protein oxidation: evidence for the formation of reactive side chain peroxides on tyrosine residues. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;76:35–46. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)076<0035:sompoe>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devasagayam TP, Sundquist AR, Di Mascio P, Kaiser S, Sies H. Activity of thiols as singlet molecular oxygen quenchers. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1991;9:105–116. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(91)80008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Mascio P, Devasagayam TP, Kaiser S, Sies H. Carotenoids, tocopherols and thiols as biological singlet molecular oxygen quenchers. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990;18:1054–1056. doi: 10.1042/bst0181054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clennan EL, Hightower SE, Greer A. Conformationally induced electrostatic stabilization of persulfoxides: a new suggestion for inhibition of physical quenching of singlet oxygen by remote functional groups. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11819–11826. doi: 10.1021/ja0525509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanofsky JR. Singlet oxygen production by biological systems. Chem Biol Interact. 1989;70:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kochevar I. Singlet oxygen signaling: from intimate to global. Science Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment. 2004 doi: 10.1126/stke.2212004pe7. DOI: 10.1126/stke.2212004pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lupinkova L, Komenda J. Oxidative modifications of the Photosystem II D1 protein by reactive oxygen species: from isolated protein to cyanobacterial cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;79:152–162. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2004)079<0152:omotpi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piette J. Biological consequences associated with DNA oxidation mediated by singlet oxygen. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1991;11:241–260. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(91)80030-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright A, Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. Singlet oxygen-mediated protein oxidation: evidence for the formation of reactive peroxides. Redox Rep. 2000;5:159–161. doi: 10.1179/135100000101535573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glaeser J, Klug G. Photo-oxidative stress in Rhodobacter sphaeroides: protective role of carotenoids and expression of selected genes. Microbiology. 2005;151:1927–1938. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishiyama Y, Allakhverdiev SI, Yamamoto H, Hayashi H, Murata N. Singlet oxygen inhibits the repair of photosystem II by suppressing the translation elongation of the D1 protein in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11321–11330. doi: 10.1021/bi036178q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braatsch S, Moskvin OV, Klug G, Gomelsky M. Responses of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides transcriptome to blue light under semiaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7726–7735. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7726-7735.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell EA, Tupy JL, Gruber TM, Wang S, Sharp MM, Gross CA, Darst SA. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli σE with the cytoplasmic domain of its anti-sigma RseA. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ades SE, Connolly LE, Alba BM, Gross CA. The Escherichia coli σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-sigma factor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2449–2461. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ades SE, Grigorova IL, Gross CA. Regulation of the alternative sigma factor σE during initiation, adaptation, and shutoff of the extracytoplasmic heat shock response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2512–2519. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2512-2519.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alba BM, Gross CA. Regulation of the Escherichia coli σE-dependent envelope stress response. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:613–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bae JB, Park JH, Hahn MY, Kim MS, Roe JH. Redox-dependent changes in RsrA, an anti-sigma factor in Streptomyces coelicolor: zinc release and disulfide bond formation. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ilbert M, Graf PC, Jakob U. Zinc center as redox switch--new function for an old motif. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:835–846. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang JG, Paget MS, Seok YJ, Hahn MY, Bae JB, Hahn JS, Kleanthous C, Buttner MJ, Roe JH. RsrA, an anti-sigma factor regulated by redox change. Embo J. 1999;18:4292–4298. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li W, Bottrill AR, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Paget MS, Kleanthous C. The role of zinc in the disulphide stress-regulated anti-sigma factor RsrA from Streptomyces coelicolor. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gracanin M, Hawkins CL, Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Singlet-oxygen-mediated amino acid and protein oxidation: formation of tryptophan peroxides and decomposition products. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graham AI, Hunt S, Stokes SL, Bramall N, Bunch J, Cox AG, McLeod CW, Poole RK. Severe zinc depletion of Escherichia coli: roles for high affinity zinc binding by ZinT, zinc transport and zinc-independent proteins. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18377–18389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.001503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newman JD. Rhodobacter sphaeroides. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2001. The sigma factor/anti-sigma factor pair, σE/ChrR in. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd edit. 3 Volumes vols. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sistrom WR. A requirement for sodium in the growth of Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. J Gen Microbiol. 1960;22:778–785. doi: 10.1099/00221287-22-3-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schilke BA, Donohue TJ. ChrR positively regulates transcription of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1929–1937. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1929-1937.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tavano CL, Podevels AM, Donohue TJ. Identification of genes required for recycling reducing power during photosynthetic growth. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5249–5258. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5249-5258.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]