Abstract

This study’s objective is to examine the relative effectiveness of cigarettes and waterpipe (WP) in reducing tobacco abstinence symptoms in dual cigarette/WP smokers. Sixty-one dual cigarette/WP smokers participated (mean age ± SD 22.0 ± 2.6 yrs; mean cigarettes/day 22.4 ± 10.1; mean WPs/week 5.2 ± 5.6). After 12-hour abstinence participants completed two smoking sessions (WP or cigarette), while they responded to subjective measures of withdrawal, craving, and nicotine effects administered before smoking and 5, 15, 30 and 45 minutes thereafter. For both tobacco use methods, scores on measures of withdrawal and craving were high at the beginning of session (i.e., before smoking) and were reduced significantly and comparably during smoking. Analysis of smoking and recovery (post-smoking) phases showed similarity in the way both tobacco use methods suppressed withdrawal and craving, but the recovery of some of these symptoms can be faster with cigarette use. This study is the first to show the ability of WP to suppress abstinence effects comparably to cigarettes, and its potential to thwart cigarette cessation.

Keywords: addiction, nicotine, waterpipe, cigarette, withdrawal, clinical study

1. Introduction

Waterpipe smoking (WP), also known as hookah, narghile, and shisha, involves the inhalation of smoke after passage through water. WP is a centuries-old tobacco use method associated traditionally with Middle Eastern societies, but has surged in popularity among youth worldwide in the past two decades (Maziak, 2011).

Waterpipe smoking is associated with nicotine exposure as indexed by levels of nicotine and its metabolites in blood and other bodily fluids (e.g. Eissenberg & Shihadeh, 2009). Tobacco abstinence symptoms have also been reported in WP smokers, and these symptoms were reduced by subsequent WP use (Maziak et al., 2009). Moreover, some cigarette smokers may use WP during a cigarette cessation attempts (Asfar et al., 2008), perhaps as a means of reducing the severity of tobacco abstinence effects. Tobacco abstinence symptom suppression that results from switching to WP during a cigarette cessation attempt may lead to continued WP use (i.e., through negative reinforcement, Eissenberg, 2004) or relapse to cigarettes because of lower accessibility of WP compared to cigarettes. In either case, the resulting continuation of tobacco use threatens the potential health benefit of the cessation attempt. In order to account for the cigarette replacement potential of WP in our cessation efforts, we need to understand its underlying mechanisms and nuances, especially given the difference in smoking patterns and subsequently nicotine delivery between WP (i.e. more prolonged and intermittent) and cigarettes. This study aims to examine the relative effectiveness of WP and cigarettes in reducing tobacco abstinence symptoms in dual cigarette/WP smokers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Study participants were recruited through advertisements and by word-of-mouth and were invited to the Syrian Center for Tobacco Studies (SCTS) clinical lab in Aleppo, Syria. Volunteers were included in the study if they were 18 to 55 years of age, reported smoking one or more WPs per week and 10 or more cigarettes per day during the past 6 months, and were in good general health. Volunteers were excluded if they reported any medical or psychological problems, were breastfeeding, or were pregnant. This analysis includes 61 subjects (56 male, mean age ± SD 22.0 ± 2.6 yrs, mean weekly WPs 5.2 ± 5.6; mean daily cigarettes 22.4 ± 10.1), who agreed to participate in this study and followed the IRB-approved study protocol.

2.2. Design and procedures

In this within-subject study, each participant completed two smoking sessions that differed by tobacco use method (WP or cigarette; session order was randomized). Participants were asked to abstain from all tobacco products for at least 12 hours (verified with expired air CO levels ≤ 10 ppm) prior to the start of 2 sessions (separated by at least 48 hours), where they smoked either WP or their usual cigarette brand ad libitum. For the cigarette session, participants were provided with their preferred brand of cigarette and started a 5-minute cigarette use episode. For the WP session, participants were provided with their preferred brand and flavor of WP tobacco, as well as other necessary materials, and they completed a 30 minutes ad libitum session. Both sessions were concluded 45 minutes after smoking onset. Participants who completed the entire protocol were paid 2,000 Syrian Lira (≈ 40 USD).

2.3. Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of this study were subjective measures of tobacco abstinence and nicotine effects that were translated into Arabic, computerized, and pilot tested in a previous study (Maziak et al., 2009). Participants were trained to use a computer keyboard and mouse to respond to the following measures which were administered in both sessions before smoking and exactly at 5, 15, 30 and 45 minutes after smoking onset. 1) The Hughes–Hatsukami Withdrawal scale (HH, adapted from Buchhalter, Acosta, Evans, Breland, & Eissenberg, 2005) consists of 11 items presented as visual analog scales anchored with not at all on the left and with extremely on the right. 2) The Tiffany–Drobes Questionnaire on Smoking Urges (QSU-brief, adapted from Cox, Tiffany, & Christen, 2001) consists of 10 items (and two factors - intention to smoke, and - anticipation of relief from withdrawal) that are rated on a scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). 3) The Direct Effects of Nicotine scale (DENS, adapted from Kleykamp, Jennings, Sams, Weaver, & Eissenberg, 2008) consists of 10 visual analog scale items (scales’ details in Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the repeated model ANOVA for the whole smoking session (waterpipe, cigarettes)

| Type | Time | Type * Time | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | ω2* | F | Sig. | ω2 | F | Sig. | ω2 | |

| Hughes-Hatsukami Withdrawal scale | |||||||||

| 1- Urges to smoke | 15.5 | 0.000 | 0.206 | 29.6 | 0.000 | 0.331 | 6.6 | 0.000 | 0.100 |

| 2- Irritability/frustration/anger | 4.1 | 0.048 | 0.063 | 25.5 | 0.000 | 0.299 | 1.8 | 0.147 | 0.030 |

| 3- Anxious | 5.3 | 0.024 | 0.082 | 19.0 | 0.000 | 0.241 | 0.6 | 0.604 | 0.010 |

| 4- Difficulty concentrating | 1.2 | 0.280 | 0.019 | 10.6 | 0.000 | 0.150 | 0.7 | 0.538 | 0.012 |

| 5- Restlessness | 14.5 | 0.000 | 0.195 | 21.2 | 0.000 | 0.261 | 0.8 | 0.471 | 0.014 |

| 6- Hunger | 3.0 | 0.088 | 0.048 | 4.1 | 0.018 | 0.064 | 3.6 | 0.013 | 0.057 |

| 7- Impatient | 4.8 | 0.032 | 0.075 | 37.5 | 0.000 | 0.384 | 2.2 | 0.095 | 0.036 |

| 8- Craving a cigarette/waterpipe/nicotine | 7.6 | 0.008 | 0.113 | 28.9 | 0.000 | 0.325 | 10.5 | 0.000 | 0.149 |

| 9- Drowsiness | 4.8 | 0.033 | 0.074 | 3.5 | 0.021 | 0.055 | 1.1 | 0.337 | 0.019 |

| 10- Depression/feeling blue | 1.0 | 0.312 | 0.017 | 9.3 | 0.000 | 0.134 | 0.9 | 0.428 | 0.015 |

| 11- Desire for sweets | 0.6 | 0.454 | 0.009 | 0.8 | 0.464 | 0.013 | 0.7 | 0.532 | 0.012 |

| The Tiffany-Drobes Questionnaire of Smoking Urges | |||||||||

| 1- Intention to smoke | 30.7 | 0.000 | 0.338 | 29.6 | 0.000 | 0.330 | 26.8 | 0.000 | 0.308 |

| 2- Anticipation of relief from withdrawal | 15.1 | 0.000 | 0.201 | 22.0 | 0.000 | 0.268 | 18.4 | 0.000 | 0.235 |

| The Direct Effects of Nicotine scale | |||||||||

| 1- Nauseous | 1.0 | 0.325 | 0.016 | 2.3 | 0.087 | 0.037 | 7.0 | 0.000 | 0.105 |

| 2- Dizzy | 0.1 | 0.722 | 0.002 | 15.5 | 0.000 | 0.206 | 20.7 | 0.000 | 0.257 |

| 3- Lightheaded | 0.2 | 0.642 | 0.004 | 5.9 | 0.001 | 0.090 | 7.9 | 0.000 | 0.116 |

| 4- Nervous | 0.4 | 0.540 | 0.006 | 12.5 | 0.000 | 0.173 | 1.0 | 0.393 | 0.017 |

| 5- Sweaty | 0.2 | 0.695 | 0.003 | 1.2 | 0.324 | 0.019 | 1.8 | 0.142 | 0.029 |

| 6- Headache | 0.4 | 0.537 | 0.006 | 1.4 | 0.256 | 0.022 | 1.7 | 0.168 | 0.028 |

| 7- Excessive salivation | 0.3 | 0.585 | 0.005 | 3.5 | 0.015 | 0.056 | 2.9 | 0.031 | 0.047 |

| 8- Heart pounding | 1.1 | 0.296 | 0.018 | 5.2 | 0.002 | 0.080 | 8.8 | 0.000 | 0.128 |

| 9- Confused | 0.0 | 0.860 | 0.001 | 8.8 | 0.000 | 0.127 | 1.5 | 0.204 | 0.025 |

| 10- Weak | 1.1 | 0.298 | 0.018 | 3.3 | 0.020 | 0.052 | 6.1 | 0.000 | 0.092 |

ω2* Partial eta-squared

F and P were calculated according to Greenhouse-Geisser modification.

Score results on repeated model ANOVA with two within-factors; Type with 2 levels (cigarette and waterpipe) and time with 5 levels (pre-smoking, at 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, and 45 minutes after start smoking).

2.4. Data Analysis

In order to compare the effects of smoking cigarette and WP, subjective data were entered into a repeated model ANOVA with two within-subject factors: time (presmoking, 5, 15, 30 and 45 minutes after start of smoking) and condition (cigarette or WP). We report F, P and partial eta-squared for the repeated model ANOVA for the whole session analysis. F and P were calculated according to the Greenhouse-Geisser method, which corrects for any violation of the sphericity assumption. Partial eta-squared is an indicator of the proportion of total variability attributable to a factor. Results of the repeated model ANOVA analysis are listed in Table 1.

To compare the effects of smoking between cigarette and WP for relatively similar segments of the smoking sessions (because cigarette smoking lasted 5 min, while WP smoking lasted 30 min), we ran a series of contrast analyses using Least Squares means (LS means) as follows: 1) Condition main effects (for each time point) to detect the differences between two sessions at each time point. 2) Specific comparisons of particular session phases; Smoking phase analysis: (0 to 5 minutes cigarette vs. 0 to 5 minutes WP) to compare score changes during equal times of smoking, and (0 to 5 minutes cigarette vs. 0 to 30 minutes WP) to compare score changes during the whole smoking time; Recovery phase analysis: (5 to 15 minutes cigarette vs. 30 to 45 minutes WP) to compare score changes for the first recovery period during almost equal times, and (5 to 45 minutes cigarette vs. 30 to 45 minutes WP) to compare changes for the whole recovery period. Results of LS means comparisons are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the contrast analysis comparisons of LS means for the repeated model ANOVA

| Time comparisons | Smoking comparisons |

Recovery comparisons |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | |

| Hughes-Hatsukami | |||||||||

| 1- Urges to smoke | 0.004 | 0.765 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.267 | 0.424 | 0.001 |

| 2- Irritability/frustration/anger | 0.173 | 0.791 | 0.076 | 0.004 | 0.054 | 0.314 | 0.865 | 0.996 | 0.294 |

| 3- Anxious | 0.095 | 0.537 | 0.036 | 0.079 | 0.171 | 0.197 | 0.755 | 0.258 | 0.598 |

| 4- Difficulty concentrating | 0.347 | 0.789 | 0.208 | 0.720 | 0.169 | 0.320 | 0.482 | 0.271 | 0.309 |

| 5- Restlessness | 0.329 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.069 | 0.001 | 0.201 | 0.272 | 0.802 | 0.885 |

| 6- Hunger | 0.635 | 0.507 | 0.102 | 0.147 | 0.001 | 0.309 | 0.377 | 0.152 | 0.013 |

| 7- Impatient | 0.737 | 0.790 | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.631 | 0.716 | 0.413 | 0.054 |

| 8- Craving a cigarette/waterpipe/nicotine | 0.558 | 0.527 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.898 | 0.019 | 0.395 | 0.029 |

| 9- Drowsiness | 0.891 | 0.049 | 0.070 | 0.219 | 0.045 | 0.074 | 0.017 | 0.421 | 0.183 |

| 10- Depression/feeling blue | 0.900 | 0.659 | 0.443 | 0.304 | 0.068 | 0.634 | 0.317 | 0.695 | 0.445 |

| 11- Desire for sweets | 0.972 | 0.432 | 0.926 | 0.236 | 0.278 | 0.456 | 0.509 | 0.879 | 0.553 |

| The Tiffany- Drobes Questionnaire of Smoking Urges | |||||||||

| 1- Intention to smoke | 0.000 | 0.891 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.180 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| 2- Anticipation of relief from withdrawal | 0.013 | 0.415 | 0.064 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.102 | 0.079 | 0.005 |

| The direct effects of nicotine scale | |||||||||

| 1- Nauseous | 0.895 | 0.011 | 0.229 | 0.006 | 0.050 | 0.013 | 0.403 | 0.172 | 0.017 |

| 2- Dizzy | 0.421 | 0.000 | 0.142 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| 3- Lightheaded | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.458 | 0.013 | 0.518 | 0.496 | 0.839 | 0.151 | 0.018 |

| 4- Nervous | 0.256 | 0.917 | 0.946 | 0.581 | 0.200 | 0.298 | 0.540 | 0.476 | 0.625 |

| 5- Sweaty | 0.078 | 0.553 | 0.933 | 0.575 | 0.468 | 0.135 | 0.060 | 0.325 | 0.897 |

| 6- Headache | 0.166 | 0.185 | 0.946 | 0.168 | 0.928 | 0.772 | 0.601 | 0.794 | 0.551 |

| 7- Excessive salivation | 0.126 | 0.446 | 0.439 | 0.066 | 0.580 | 0.487 | 0.266 | 0.398 | 0.790 |

| 8- Heart pounding | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.645 | 0.064 | 0.076 | 0.596 | 0.729 | 0.036 | 0.005 |

| 9- Confused | 0.421 | 0.272 | 0.253 | 0.469 | 0.965 | 0.898 | 0.465 | 0.025 | 0.064 |

| 10- Weak | 0.205 | 0.001 | 0.817 | 0.193 | 0.424 | 0.078 | 0.474 | 0.125 | 0.026 |

Results of comparisons of LS means (contrast analysis) from the repeated model ANOVA

P1: Cigarette versus waterpipe at start

P2: Cigarette versus waterpipe at 5 minutes

P3: Cigarette versus waterpipe at 15 minutes

P4: Cigarette versus waterpipe at 30 minutes

P5: Cigarette versus waterpipe at 45 minutes

P6: (0 to 5 minutes cigarette) versus (0 to 5 minutes waterpipe)

P7: (0 to 5 minutes cigarette) versus (0 to 30 minutes waterpipe)

P8: (5 to 15 minutes cigarette) versus (30 to 45 minutes waterpipe)

P9: (5 to 45 minutes cigarette) versus (30 to 45 minutes waterpipe)

Because we employed a series of significance tests, and to avoid increasing the familywise error rate above 0.05, we applied a Bonferroni adjustment and considered results significant only if the P was less than 0.05 divided by the number of comparisons.

We used STATISTICA Version 8.0 for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Session analysis (45-minute session

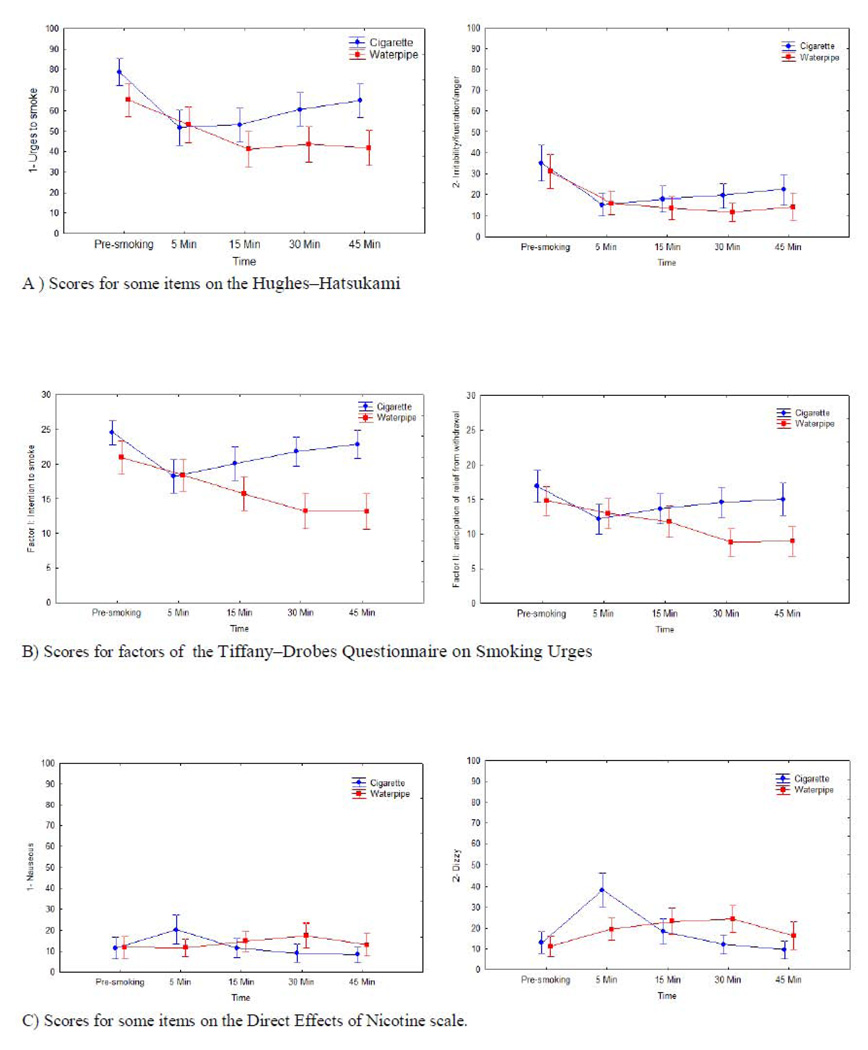

Analyses of data across the entire session revealed that the expression of withdrawal and craving symptoms was marked at the beginning of session (pre-smoking) for the two tobacco use conditions (WP and cigarettes), and that these symptoms decreased significantly during smoking in both conditions. Figure 1 displays data from several representative measures which demonstrate the dynamics of subjective results across session time for the two tobacco use methods. The figure generally shows comparable craving/withdrawal suppression (HH and QSU-brief) across conditions. On the DEN, scores increased with smoking but results were generally similar across conditions. We observed that withdrawal/craving symptoms began to recover at the 5-minute point for cigarettes but not for WP, mainly due to the difference in smoking periods between the two conditions (see Figure 1 and Table 1 for details). The analysis below addresses this point.

Figure 1.

Shows some items of the scores: A) Hughes-Hatsukami Withdrawal scale, B) Tiffany-Drobes questionnaire of smoking urges, and C) direct effects of nicotine scale. Score are presented in mean and with 95% confidence interval.

3.2. Smoking phase analysis

For the smoking phase, we tested condition main effects in each time point (P1 through P5 in Table 2) and condition by time interactions in the first five minutes of all sessions when all participants were smoking (P6 in Table 2), and for the whole smoking period (P7 in Table 2) . Analysis of these data revealed that, in general, there was no significant main condition effect (cigarette vs. WP) or condition by time interactions (changes in scores from pre-smoking to the end of first 5 minutes of the session did not depend upon condition), though there were significant main effects of time for most items in both conditions.

3.3. Recovery phase analysis

For the recovery phase, we tested the condition by time interaction for the first available period immediately after smoking ceased (P8). This period corresponded to minutes 5–15 of the cigarette session (a 10-minute period) and minutes 30–45 of the WP session (a 15-minute period). We also tested the interaction for the whole recovery period (5–45 minutes for cigarettes vs. 30–45 minutes for WP: P9). Analysis of these data revealed that, in general, there is no significant condition by time interaction for most of the items, indicating a similar pronounced recovery of abstinence/craving symptoms in the cigarette compared to WP conditions. It also shows a consistent time effect on both craving (urges) and nicotine effects (DEN) and a more pronounced recovery of craving symptoms across time with cigarettes compared to WP. Generally, Figure 1 shows that that recovery of several withdrawal/craving symptoms was more pronounced with cigarettes compared to WP.

4. Discussion

Overall, this study shows that WP smoking can suppress abstinence-induced withdrawal and craving in a comparable fashion to cigarettes in people who smoke both cigarettes and WP. The observed ability of WP to suppress abstinence effects may at least partly underlie cigarette-replacement by WP that was observed in cigarette quitters (Asfar et al., 2008). WP’s effects on abstinence symptoms may also be mediated, at least partly, by nicotine delivery as judged by the comparative increase in nicotine-related symptoms (DEN) during the smoking phase for both WP and cigarettes. These results corroborate the circumstantial evidence from both quantitative and qualitative studies alluding to the interchangeable use of the two tobacco use methods and suggest a plausible explanation for such behavior in some smokers (Asfar et al., 2008; Hammal, Mock, Ward, Eissenberg, & Maziak, 2008). The importance of understanding what prompts such switching between tobacco use methods stems from its potential to undermine tobacco control by thwarting quitting attempts among cigarette smokers and by providing a gateway to cigarette smoking among WP smokers (Maziak, 2011). The latter risk (gateway to cigarettes) is particularly relevant given that WP use is timeconsuming and mobility-limiting (i.e., it is mostly practiced in a seated setting for 30 minutes or more). Such attributes may lead dependent WP smokers to seek abstinence suppression using more convenient tobacco smoking methods, such as cigarettes.

The observed differences between the two smoking methods in terms of their withdrawal/craving/nicotine effects may be due mainly to longer smoking sessions of WP and hence a more gradual delivery of potentially larger doses of nicotine compared to cigarette smoking sessions. For example, during the smoking and recovery phases, suppression and recovery of the two factors of the QSU-brief (intention to smoke, and anticipated relief of withdrawal) were faster and more pronounced in the cigarette condition. This was mirrored by the pattern of change in some nicotine effect (DEN) items, which suggests differences in nicotine delivery between the two smoking methods as a potential explanation. In fact, research done by our team has already established a more gradual but larger exposure to nicotine during a WP session compared to a cigarette session (Eissenberg & Shihadeh, 2009). The other factor that may potentially influence faster and more pronounced recovery of craving/urges in the cigarette compared to WP conditions is the difference in smoking patterns of the two tobacco methods among our subjects (participants smoked on average 22 cigarettes/day but only 5 WP/week) (Schuh & Stitzer, 1995).

The main limitation of this study lies with the timing of questionnaires’ administration (at 0, 5, 15, 30, 45 minutes) and the fact that the recovery phase for cigarettes is shorter (10 minutes) than that for WP (15 minutes). It is unlikely that this difference substantially undermined the analysis of the recovery phase, as we could still capture a faster and more pronounced recovery of indices of smoking urges for cigarettes consistent with its fast nicotine delivery and other aforementioned use patterns. Finally, we could only speculate that nicotine exposure can provide the underlying mechanism for some of the withdrawal/craving dynamics observed based on nicotine-related symptoms of DEN.

This study highlights the cigarette-replacement potential of WP, and provides a plausible mechanism for switching between tobacco use methods in some users as a way to deal with unpleasant symptoms of abstinence. As such WP smoking may thwart tobacco cessation efforts, and should be addressed in all prevention and cessation programs, especially those targeting youth and in regions where WP use is widespread.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (DA024876 and CA120142).

Funding for this study was provided by U.S. National Institutes of Health (DA024876 and CA120142).

Maziak and Eissenberg designed the study. Rastam and Ibrahim conducted the study and performed the analysis. Maziak wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Asfar T, Weg M, Maziak W, Hammal F, Eissenberg T, Ward K. Outcomes and adherence in Syria's first smoking cessation trial. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:146–156. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchhalter AR, Acosta MC, Evans SE, Breland AB, Eissenberg T. Tobacco abstinence symptom suppression: the role played by the smoking-related stimuli that are delivered by denicotinized cigarettes. Addiction. 2005;100(4):550–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox L, Tiffany S, Christen A. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T. Measuring the emergence of tobacco dependence: the contribution of negative reinforcement models. Addiction. 2004;99 Suppl 1:5–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammal F, Mock J, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Maziak W. A pleasure among friends: how narghile (waterpipe) smoking differs from cigarette smoking in Syria. Tobacco Control. 2008;17(2):e3–e3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleykamp B, Jennings J, Sams C, Weaver M, Eissenberg T. The influence of transdermal nicotine on tobacco/nicotine abstinence and the effects of a concurrently administered cigarette in women and men. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16(2):99–112. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maziak W. The global epidemic of waterpipe smoking. Addict Behav. 2011;36(1–2):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maziak W, Rastam S, Ibrahim I, Ward K, Shihadeh A, Eissenberg T. CO exposure, Puff Topography, and Subjective Effects in Waterpipe Tobacco Smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(7):806–811. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh K, Stitzer M. Desire to smoke during spaced smoking intervals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120(3):289–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02311176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]