Abstract

Objectives:

Abuse against women causes a great deal of suffering for the victims and is a major public health problem. Measuring lifetime abuse is a complicated task; the various methods that are used to measure abuse can cause wide variations in the reported occurrences of abuse. Furthermore, the estimated prevalence of abuse also depends on how abuse is culturally defined. Researchers currently lack a validated Arabic language instrument that is also culturally tailored to Arab and Middle Eastern populations. Therefore, it is important to develop and evaluate psychometric properties of an Arabic language version of the newly developed NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionnaire (NORAQ).

Design and methods:

The five core elements of the NORAQ (emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, current suffering of the abuse, and communication of the history of abuse to the general practitioner) were translated into Arabic, translated back into English, and pilot tested to ensure cultural sensitivity and appropriateness for adult women in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Participants were recruited from the Jordanian Ministry of Health-Maternal and Child Health Care Centers in two large cities in Jordan.

Results:

A self administered NORAQ was completed by 175 women who had attended the centers. The order of factors was almost identical to the original English and Swedish languages questionnaire constructs. The forced 3-factor solution explained 64.25% of the variance in the measure. The alpha reliability coefficients were 0.75 for the total scale and ranged from 0.75 to 0.77 for the subscales. In terms of the prevalence of lifetime abuse, 39% of women reported emotional abuse, 30% physical abuse, and 6% sexual abuse.

Conclusion:

The Arabic version of the NORAQ has demonstrated initial reliability and validity. It is a cost-effective means for screening incidence and prevalence of lifetime domestic abuse against women in Jordan, and it may be applicable to other Middle East countries.

Keywords: domestic violence, Middle East, Jordan, instrumentation

Introduction

Domestic violence against women (gender-based violence) is a human rights crime and a costly public health problem throughout the world.1,2 Globally, up to 6 out of every 10 women experience physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime. No country is immune to the devastating physical and emotional effects of violence. Each year, it results in over 1.6 million deaths worldwide – over 90% of which occur in low- and middle-income countries. Most of the victims are women. Violence is among the leading causes of death and disability in all parts of the world for women of age 15 to 44.2 A World Health Organization study of 24,000 women in 10 countries found that the prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence by a partner varied from 15% in urban Japan to 71% in rural Ethiopia, with most areas in the 30% to 60% range.2

Domestic violence against women is still a high public health concern, especially as it continues to be accepted as “normal” within many societies.1–5 The World Health Organization’s 2002 World Report on Violence and Health defines intimate partner violence (IPV) as “any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, or sexual harm to those in the relationship”.5 The traumatic consequences of IPV against women have repercussions far beyond the immediate harm. Women enduring violence are more likely to suffer physical, mental, and reproductive health problems.4,5 Violence leads to unwanted pregnancies, high-risk pregnancies, and pregnancy-related problems, including miscarriage, pre-term labor, and low birth weight.6–10 Furthermore, IPV against pregnant women before and during pregnancy has serious health consequences for both mother and child. Women who have experienced sexual violence are at higher risk of contracting HIV and sexually transmitted diseases. Fear of violence may also prevent women from accessing HIV/AIDS information and receiving treatment and counselling.7,11,12 Unfortunately, the consequences of gender-based violence do not only affect women; they also impact the children who witness such violence. Often, children growing up in families where there is violence suffer from feelings of helplessness, low self-esteem, anger, shame, and guilt and are more likely to become abusers or victims themselves.11,12

Methodological consideration in intimate partner violence research

A key consideration in measuring IPV is related to the way IPV is defined. So in order to assess the prevalence of IPV, it is important to determine or identify the crucial factors. The definition of IPV is certainly one. For example, a behavior that is labeled as abusive by one person might not seem abusive to someone else.13 When asking about a woman’s experiences with wife abuse, one can either ask her to define if she was abused or not or to give specific examples of abusive acts. There are various types of abuse: sexual, physical, or emotional. Any experiences of abuse can also include all these three components. For example, the definition of sexual abuse might vary from oral, vaginal, or anal penetration, to any unwanted sexual activity, to contact and no contact, including threats in varying degrees, or in combination with other kinds of abuse. The definition also may be very detailed, including age limits of the victim. The time aspects of abuse also have to be defined, eg, occurrence ever in life, during the past year, during pregnancy, or if the abuse happened once or was repeated.

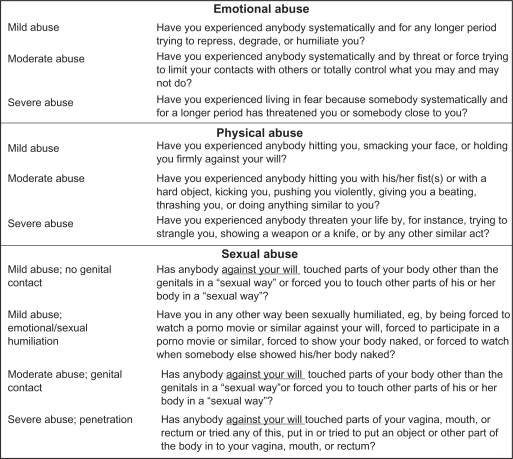

In 2003, the original NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionnaire (NORAQ) psychometric evaluation of the Scandinavian version was established. The NORAQ measurement purpose was to develop and to operationalize gender violence.13–15 As it includes detailed questions with several examples of abusive acts (Figure 1) the specificity of the questionnaire concerning emotional and sexual abuse was 98%. The specificity of the physical abuse was only 85%. The NORAQ has good test–retest reliability.13,14 The NORAQ measure was developed with a white, western, middle class population.15

Figure 1.

Questions about abuse in the NORAQ.

Abbreviation: NORAQ, NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionaire. Data from Swahnberg and Wijma13,15

The authors have recommended that the NORAQ be used in estimating prevalence with populations of more diverse socioeconomic levels and cultural backgrounds to evaluate construct validity and establish norms for various population subgroups.13,14

Domestic violence against women in Jordan

Jordan is a developing, low-income country that is adapting to the present trends of a modern economy. It is geographically situated between Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Israel, and Syria in the Middle East. Administratively, Jordan has three regions with twelve governorates. The gross domestic product is US$8.9 billion, which yields a mean of US$1,744 per capita.16 Ninety-six percent (96%) of the Jordanian citizens are Muslims, and the rest are Christians. Recently, IPV has become a more recognized public health issue in Jordan due to the openness of the Jordanian community to democratization. Moreover, different governmental organizations have played a role in increasing public awareness of these issues. The Jordanian government has established a family protection unit within the local police department to deal with cases of gender-based violence.16,17

Recently, there has been an increased recognition of IPV in Jordan and rapid expansion of research. Additionally, numerous new measures of IPV have been adopted; however, no validation studies have been published about the used questionnaires.

If the measurement basis is equivalent, a uniform presentation facilitates comparison of prevalence estimates between studies. In the following two Jordanian prevalence studies, each has its own definition and estimates of IPV. In both of these studies there is neither an estimate on childhood nor lifetime sexual, physical, or emotional abuse.

The first study reported that approximately one in four women were at risk of physical violence committed primarily by husbands, fathers, and brothers. This makes physical violence the most prevalent form of domestic violence experienced by Jordanian women.18 In the other study, spousal abuse was the most prevalent form of IPV, with a 44.7% rate of lifetime abuse.19

A recent report by the United Nations Development Fund for Women17 found that women who are victims of IPV were often reluctant to report the violence to police or authorities out of fear of social unacceptability and shame. Battered women may also be pressured by their families to drop the charges.20,21 In Jordanian culture, violence against women is considered a private and sensitive family matter.22 Often women found themselves bound to social and cultural rules shaped by male dominance over women.23,24 The Jordanian Department of Statistics revealed a widespread acceptance of IPV in society in general and that 87% of Jordanian women justified wife beating under at least one circumstance.17,18 This suggests that estimating prevalence in Jordan is a complex area with many methodological problems and obstacles.

Aims of the study

Clear, accurate, and appropriate assessment of gender-based violence incidence and prevalence among Jordanian Arab women is essential for Jordanian social and health policy makers. A reliable, valid, and culturally appropriate IPV assessment tool will enable health professionals in Jordan and other Arab countries to estimate the suffering that stems from IPV. In addition, this cross-cultural adaptation of the NORAQ should facilitate cross-cultural comparison in order to identify differences attributable to cultures in providing not only setting-specific data but allowing for comparison across settings and sites. Validated research instruments about abuse in the Arab countries are scarce, but they are urgently required. This is the first validation study of an instrument in a Middle Eastern country. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe the psychometric evaluation of an Arabic language version of the NORAQ in Jordan, a dissimilar culture and society from that of Scandinavian countries, where the NORAQ was developed. The evaluation process included the translation procedure, confirmation of content and construct validity, estimation of reliability, and estimation of prevalence.

Methods

Setting and population

Data were collected from a convenient sample of 175 women recruited from urban and rural areas in two major governorates in Jordan (Amman in the center and Irbid in the north). Participants were recruited from the Jordanian Ministry of Health-Maternal and Child Health Care Centers. The Ministry of Health (MOH) is the main provider of primary health care (PHC) services in Jordan. The MOH provides PHC services through a network of health care centers that are distributed all over the country. These centers reach 95% of the urban and the rural population and offer general practice and maternal child health care (MCH) services. Physicians, nurses, and midwives usually provide MCH services. The most important functions of the MCH are childhood immunizations, prenatal care, and dental care.17 Furthermore, it is culturally common in those centers and in Jordan that the mother, not the father, takes the child to the immunization clinics. On rare occasions both parents may take the child to the clinic. All the participants met the following inclusion criteria: 1) age above 18 years; 2) are able to read and write Arabic (literate); and 3) willing to complete the questionnaire.

Procedure and human participation protection

Formal permission to conduct the study in the MOH centers was obtained from the Jordan University of Science and Technology Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the ethical committee at MOH. Ethical codes were addressed in the cover letter of the questionnaire. The researcher explained the purpose of the research to all participants. The assurance of anonymity was addressed prior to the request for participation, and only aggregated data were reported. Furthermore, participants were assured that their participation in the study was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. The investigators and research assistants explained the purpose of the study to individuals and groups at the various health centers and informed them that participation was voluntary and anonymous. The Arabic language questionnaire, a demographic data sheet, and a cover letter were distributed to all volunteer study participants, who were encouraged to complete all items. Investigators were available to answer questions and provide clarification as needed during data collection sessions. The participation refusal rate was 2.0%.

NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionnaire

The NORAQ measures four types of abuse: emotional, physical, sexual, and abuse in the health care system. The NORAQ includes detailed questions with several examples of abusive acts (Figure 1). Figure 1 has a detailed definition and examples of abuse in the NORAQ questionnaire. The questions in the NORAQ were tested for validity and reliability against an interview and two validated questionnaires.13 NORAQ showed good test–retest reliability. The specificity of the NORAQ regarding emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and abuse in the health care system is 98%. The specificity for physical abuse is 85%, and that was probably due to the definition of mild physical abuse.13 For the purpose of this study, the category “abuse in the health care system” was not used.

The full NORAQ,13 except for the section on abuse in the health care system, was translated into Arabic. The Arabic version of the questionnaire was examined for accuracy and piloted to assure its clarity and understanding. The NORAQ-Arabic version was composed of the following parts: 1) nine general physical and mental health assessment questions; 2) measurements of the three kinds of lifetime abuse – emotional (12 items), physical (11 items), and sexual abuse (12 items); and 3) general detailed abuse questionnaire. The content of the questions ranged from mild to severe lifetime abuse. Women who reported more than one degree of a specific kind of abuse were categorized according to the most severe abusive act. Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse were defined by a positive answer to one or several of the three or four questions about each kind of abuse in NORAQ.

If a woman had experienced abuse, she was instructed to go on answering more detailed 6-item questions, eg, who the perpetrator was, when the abuse occurred, and if she ever had told anyone about what happened. She was also asked to estimate how much she currently suffers from the abusive experiences. Current suffering is measured on a 10-point scale: “0 = no suffering, 10 = suffering terribly”. The answers from the suffering variables were dichotomized in the analysis: no suffering (0) and suffering (1–10). The questionnaire closes with specific questions about abuse, such as having reported abuse to the police or fearing that one will become a victim of abuse in future.

Translation and back translation

Investigators translated the questionnaire into Arabic with permission from the original authors. The procedure’s denotation and connotation also were used to maintain the instrument’s integrity. The Arabic version was back-translated into English by a native Jordanian bilingual linguistics expert who had not seen the original English version. The investigators compared the back-translated copy to the original English NORAQ to recognize incongruities. The Arabic translation was then adjusted with corrective re-translation as necessary.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Participants’ ages ranged between 19 and 60 years with a mean age of 30 years (SD ± 2). Ninety percent (90%) of the sample were Muslim while 9.3% were Christian; 60% grew up in urban homes, and 40% came from rural backgrounds. Seventy percent (70%) of participants had a high school degree while 22.9% had secondary education, and 8% had not completed secondary school education. The results showed that 60% were homemakers, 24.1% worked in clerical positions, and 13% were teachers. The remaining 2% were college students. Nearly one third (27.2%) reported annual household incomes between US$840 and $1,671 US, 25% reported an income of US$1,689 and $2,450 US, 8.5% reported earning less than $840 US, and 16.6% made more than $4,200 US annually. The majority of the participants (80.6%) reported being healthy and stated that they did not have any medically diagnosed diseases. Finally, 81.9% of subjects reported having health insurance. 82% of the participants were married, and the rest were single.

Validity testing

Content validity was ascertained by asking four independent experts to evaluate the translated version of the NORAQ. The Arabic NORAQ was presented to an expert panel whose members were selected for their experience in public health and nursing education in Jordan. Each expert was given a content validity index form for rating each item of the NORAQ. The content validity index contained a four-option rating scale. Each item in the instrument presented four choices: 1) not relevant, 2) somewhat relevant, 3) quite relevant but needs minor alteration, and 4) very relevant. A score for each item on the four subscales was determined by the proportion of experts who rated the item as relevant (a rating of 3 or 4). All items with a score of at least 0.75 were retained if at least three out of four experts rated the item favorably.

The content validity index (CVI) for the entire instrument is the proportion of the total number of items judged to be content-valid. The Arabic NORAQ total content validity index is 0.90, indicating an acceptable level of content validity and cross-cultural validity equivalence. The CVI was needed to provide quantifiable answers to the following questions: 1) Are items relevant to or representative of the content universe? 2) Are the following items clearly written? 3) Is the final back-translated instrument conceptually equivalent within Arab culture? Following content validation procedures, the NORAQ was revised and refined according to the suggestions and opinions of the experts.

A factor analysis using principal components extraction followed by oblique rotation was performed to ascertain whether the Arabic version NORAQ items would load in a pattern similar to the one found previously in the English data sets. Any item with factor loadings below 0.30 was omitted from the analysis. Oblique rotation was selected because the initial factor axes are allowed to rotate to best summarize any clustering of variables. With oblique rotation the factors are allowed to be correlated if such correlations exist in the data. The forced, 3-factor solution obtained by principal component extraction and oblique rotation explained 64.2% of the variance in the measure. The eigenvalues and percent of variance explained by each factor are shown in Table 1. The loadings and factor structure of the items are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Variance explained by three factors on the Arabic NORAQ (N = 171)

| Factor | Eigenvalue | % of variance | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 2.80 | 28.0 | 28.0 |

| Physical abuse | 2.16 | 21.6 | 49.7 |

| Sexual abuse | 1.4 | 14.4 | 64.2 |

Abbreviation: NORAQ, NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Factor loadings and factor structures for the Arabic NORAQ (N = 171)

| Abuse question | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild sexual abuse; no genital contact | 0.89 | ||

| Mild sexual abuse; sexual humiliation | 0.78 | ||

| Moderate sexual abuse; genital contact | 0.76 | ||

| Mild emotional abuse | −0.41 | ||

| Severe physical abuse | 0.78 | ||

| Moderate physical abuse | 0.69 | −0.46 | |

| Severe sexual abuse; penetration | 0.56 | 0.62 | |

| Mild physical abuse | −0.51 | 0.54 | −0.48 |

| Moderate emotional abuse | 0.79 | ||

| Severe emotional abuse | 0.46 | 0.50 |

Abbreviation: NORAQ, NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionnaire.

Factor 1, the structure of sexual abuse, is the strongest factor and explained the greatest percentage of the variance and had the highest average loadings on the Arabic version NORAQ. However, items “mild emotional abuse” and “mild physical abuse” had cross loadings on both factor 1 (sexual) and 3, which could be explained by the mild emotional and mild physical abuse possibly reflecting some sexual abuse too.

For factor 2, physical abuse, items also loaded clearly at a level of 0.52 or higher. However, two items related to emotional and sexual abuse had cross-loading with both sexual and physical abuse.

For factor 3, emotional abuse, two out of three items loaded at levels of 0.50 and 0.79. The 4-factor solution was examined, but the findings were ambiguous, not readily interpretable, and not meaningful according to a Scree criterion of interpretability. Therefore, the 3-factors solution was retained.

Reliability testing

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of internal consistency for the total Arabic version NORAQ questionnaire and the three subscales were computed as shown in Table 3; coefficients ranged from 0.75 to 0.77. The total scale was found to have high internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient of 0.75. These coefficients indicated that three subscales have moderate to strong degrees of internal consistency reliability. Item-total correlations on the total scale ranged from a low of 0.77 for “moderate emotional abuse”, followed by “mild emotional abuse”, to a high of “mild sexual abuse, sexual humiliation” (0.80). Finally, it was not possible to conduct a test–retest to measure or include other instruments as parallel measures or as a measure of the same construct.

Table 3.

Internal consistency of the Arabic-NORAQ and its subscales (N = 171)

| Subscale | # of items | Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 3 | 0.77 |

| Physical abuse | 3 | 0.75 |

| Sexual abuse | 4 | 0.76 |

| Total scale | 10 | 0.75 |

Abbreviation: NORAQ, NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionnaire.

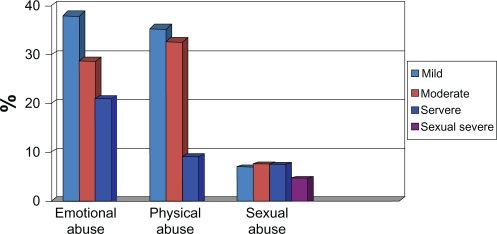

Life time prevalence

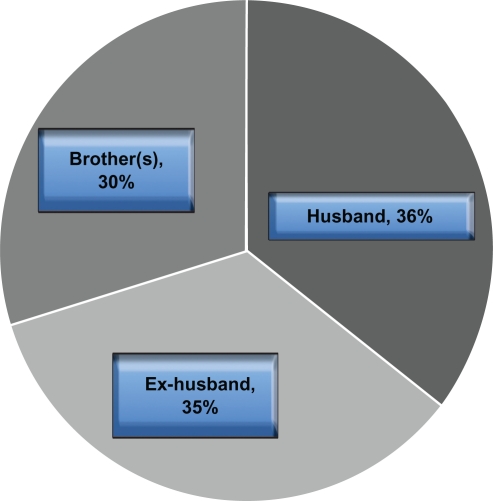

Figure 2 summarizes the lifetime prevalence of abuse. It indicates that 30% of women in this sample have been emotionally abused by their husbands, exhusbands, and/or brothers. Twenty of those were exposed to severe emotional abuse. Figure 3 indicates the identity of the abusers. In addition to the husband, the women in the sample indicated that they were abused by their brothers prior to marriage. Six percent of the women were subjected to sexual abuse. When asked to whom they talked about their abuse, 90% of the abused women said they had never talked to anyone. Also 6% of the women who been abused by their brothers were later abused by their husbands or exhusbands.

Figure 2.

Abuse prevalence (N = 174).

Figure 3.

Abuse prevalence (N = 174).

Table 4 presents the correlation coefficient between mental health outcome variables and being abused. Feelings of depression were significantly correlated with all kinds of abuse, insomnia (r = 0.43, P < 0.01), and numbed feelings (r = 0.34, P < 0.01), and were significantly correlated with overall abuse.

Table 4.

Correlation of abuse by mental health variables (N = 173)

| Anguish feelings | Depression feelings | Insomnia | Numbed feelings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 0.43** | 0.41** | 0.45** | 0.40** |

| Physical abuse | 0.32** | 0.36** | 0.37** | 0.23** |

| Sexual abuse | – | 0.16* | – | – |

| Overall abuse | 0.39** | 0.42** | 0.43** | 0.34** |

Notes:

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Discussion

The study revealed that the Arabic language version of the NORAQ has good reliability and validity. The tool would help in assessing gender-based violence among women in countries in the Middle East that share the Arabic Islamic culture.

The data for the Arabic language version of the NORAQ set in Jordan revealed some patterns of factors that differed from those in the original tool.13–15 The emotional factor was loaded in both the sexual and physical factors. This suggests that emotional abuse shared two indicators instead of one, thus further suggesting that it was influenced by two concepts. In other words, the emotional factor was a less defined factor. Furthermore, previous studies18–21 have reported that in intimate relationships physical abuse is often accompanied with emotional abuse, which could explain the loading under the physical factor in the findings.

The results indicated a strong alpha value for the three subscales (emotional, physical, and sexual), which shows that these three subscales and the total scale are reliable enough for a Jordanian or Arab sample. The alpha findings of these sub-scales are the same as those obtained by previous studies.13–15 It is worth noticing that the emotional subscale had the lower item-scale correlations. This could be explained by the fact that emotional abuse is integrated into other kinds of abuse in Islamic Arabic cultures. Or it could be explained by the fact that emotional abuse against women has been practiced as normal phenomena, evidenced by the fact that emotional abuse had the highest prevalence level of reported abuse in the sample. The mild physical abuse subscale may conflict with the Islamic cultural religion, in which the husband is asked to discipline his wife. However, it is worth mentioning that wife discipline in Islam does not involve severe physical forms; accordingly, physical abuse has been culturally accepted as a form of discipline by the Jordanian and Arabic society in general.26,29–31

The results of this study suggest a need for a replication with an inclusion of ethnographic design to identify additional culturally Arabic/Islamic specific behaviors that may not be included in this current NORAQ. The Quran states that a husband is not allowed to hurt a woman to the extent where she is left bruised, even if she has committed a sin. “As to those women on whose part you see ill-conduct, admonish them (first), (next), refuse to share their beds, (and last) beat them (lightly, if it is useful), but if they return to obedience, seek not against them means (of annoyance). Surely, Allah is Ever Most High, Most Great”. (Surah Nisa, Quran 4:34).32 This Quran verse has been abused and misinterpreted by many Muslim men and women to the extent that we believe a specific item needs to be added in this regard.

The most important findings from this study confirm that domestic abuse of women is associated with negative health outcomes. Findings similar to these have been consistently replicated in other Middle East and Western culture abuse studies.20,30 Unfortunately, most of the women may not consider mild physical illness as part of the abuse, and they may endure it in silence. They will not approach the health care system as an abuse victim since abuse is often an accepted situation in Jordanian culture.

It is noticeable that 30% of the lifetime abuse came from the woman’s brother; this could be explained by the patriarchal society and culture that was not reported in any other literature to our knowledge.

Estimating time life prevalence of women abuse

Studies on the prevalence of gender-based violence are complex and difficult to measure due to the cultural differences in defining terms such as abuse and violence, which have been very subjective for a long time. In our study we presented prevalence estimates of abuse based on our definition of abuse, which is exemplified by concrete examples in NORAQ. Thus we do not have a generally accepted definition with a clear cutoff level upon which to rely, as is the case with tobacco smoking. Furthermore, we also did not refer to the participants’ own subjective determinations as to whether or not they were abused. It might be necessary to validate the Islamic cultural context in this definition of abuse. Unfortunately, we could not assess the accuracy of the current study prevalence estimates of abuse by comparing them to other recent Jordanian studies, as in these studies there is either an estimate of lifetime IPV, or physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

Conclusion

Tools with adequate validity and reliability to measure gender-based violence in the Middle East are essential before further studies can be carried out to identify the prevalence of violence against women and measure the degree of present suffering from violence. Also, highly sensitive and specific tools could help women disclose abuse to health care workers, which would positively impact prevention and counseling services. Adding the violence screening question as part of the MOH assessment protocol will help to make women more comfortable addressing the issue and in mapping the geography of abuse across Jordan. In summary, we believe that the NORAQ-Arabic version has a very good reliability and validity. The questionnaire is ready to be adapted as a clinical tool to measure domestic abuse against women in Jordan and other Arab countries.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Jordan University of Science and Technology; Deanship of the research grant was part of LH’s sabbatical leave grant. The authors would like to acknowledge Kevin Banner for entering the raw data. Dr Todd Starkweather assisted in the English language editing of the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this paper.

References

- 1.United Nations Development Fund for Women. New York: 2000. Domestic violence against women and girls report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Division for the Advancement of Women; Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. General recommendation no 19: Violence against women. 1992. 2002. Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/recommendations/recomm.htm#recom19. Accessed 14 Feb 2011.

- 3.World Health Organization. 1996. (Document FRH/WHD/96.27). Violence against women. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1996/FRH_WHD_96.27.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2011.

- 4.Berry DB. The Domestic Violence Sourcebook. Los Angeles, CA: Lowell House; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heise L, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, et al., editors. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Åsling-Monemi K, Peña R, Ellsberg MC, Ake Persson L. Violence against women increases the risk of infant and child mortality: a case-referent study in Nicaragua. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:10–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonomi A, Thompson RS, Anderson M, et al. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical, mental and social functioning. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, et al., editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending Violence Against Women. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell J, Snow Jones A, Dienemann J, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swahnberg K, Wijma B. The NorVold Abuse Questionnaire: validation of new measures of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and abuse in the health care system among women. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13:361–366. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swahnberg K, Wijma B. Validation of the Abuse Screening Inventory (ASI) Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:330–334. doi: 10.1080/14034940601040759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijma B, Schei B, Swahnberg K, et al. Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in patients visiting gynaecology clinics: a Nordic cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2003;361:2107–2113. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13719-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Jordan Department of Statistics. The Criminal Statistical Report. Amman, Jordan: The Jordanian Department of Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Development Fund for Women Amman, Jordan. The Status of Jordanian Women Report. WHO Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Available from: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/en/index.html. Accessed 14 Feb 2011.

- 19.Badayneh T. National Plan for Protection of the Jordanian Family from Violence. Amman Jordan: The National Council for Family Affairs; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Btoush R, Haj-Yahia Attitudes of Jordanian society toward wife abuse. J Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(11):1531–1554. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linos N, Khawaja M, Al-Nsour M. Women’s autonomy and support for wife beating: findings from a population-based survey in Jordan. Violence Victims. 2010;25(3):409–419. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oweis A, Gharaibeh M, Alhourani R. Prevalence of violence during pregnancy: findings from a Jordanian survey. J Maternal Child Health. 2010;14:437–445. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark CJ, Silverman JG, Shahrouri M, Everson-Rose S, Groce N. The role of the extended family in women’s risk of intimate partner violence in Jordan. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oweis A, Al-Natour A, Froelicher E. Violence against women: unveiling the suffering of women with a low income in Jordan. J Transcultural Nurs. 2009;20:69–76. doi: 10.1177/1043659608325848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muhlbauer V. Domestic Violence in Israel Changing Attitudes. New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulwicki A. The practice of honor crimes: a glimpse of domestic violence in the Arab world. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2002;23:77–87. doi: 10.1080/01612840252825491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammoury N, Khawaja M. Injuries, violence, disasters: screening for domestic violence during pregnancy in an antenatal clinic in Lebanon. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(6):605–606. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Usta J, Farver J, Pashayan N. Domestic violence: the Lebanese experience. Public Health. 2007;121:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boy A, Kulczycki A. What we know about intimate partner violence in the Middle East and North Africa. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(1):53–70. doi: 10.1177/1077801207311860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haj-Yahia M. Wife abuse and battering in socio cultural context of Arab society. Family Process. 2002;39(2):237–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haj-Yahia M. The incidence of wife abuse and battering and some socio-demographic correlates as revealed in two national surveys in Palestinian society. J Family Violence. 2000;15:347–374. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Holy Quran. Cairo, Egypt: Al-Azhar; English version. [Google Scholar]