INTRODUCTION

Research with youth has shown substance use experimentation to be a problematic coping mechanism in the development of appropriate self-regulatory skills related to substance use in later adulthood (Percy, 2008), handling stress (Hebert, 2008; Silbereisen & Reitzle, 1991), and in peer relations (Engels & Knibbe, 2000). Thus, substance use experimentation affects multiple domains of an adolescent’s life. The undertaking of preventing adolescent substance use must therefore take into account the multiple processes associated with a constellation of complex psychosocial factors. Given that the most influential adolescent contexts include the family and the peer systems, these contexts should be specifically considered in developing socially-based preventative hypotheses. For example, family functioning and child-parent relations are critically relevant factors, which influence the handing of stress and which in turn affect adolescent health behaviors such as substance use (Hüsler & Plancherel, 2007). An additional influential factor is peer context, which, given its fluid nature, is continually shaped by developmental tasks such as emotional regulation and peer socialization, which then impact health behaviors (Bandura, 2005; Masten at al., 1995; Mason, Valente, Coatsworth, Mennis, Lawrence, & Zelenak, 2010; Zahn-Waxler, Crick, Shirtcliff, & Woods, 2006).

Past research has examined social networks and the association with tobacco and substance use (Ennett, et al., 2006, 2008). However, these studies have not explicitly addressed the complex mediating factor of social network quality (risk as well as protective factors) in the analysis of tobacco’s association with substance use, as well as the interrelated role of psychological trauma and parental relations in influencing tobacco use uptake. This lack of contextual dynamics in previous research prevents a fuller understanding of the role of family, mental health, and peers in influencing adolescent substance use and the attendant role of tobacco use. In the present study, we aim to integrate these contextual mechanisms within a strong theoretical framework utilizing sophisticated analytical modeling to provide a foundation for future longitudinal research. Based upon the prominence of peers in the social lives of adolescents and the salience of the familial context, the present study was designed to examine the role of peer relations within personal social networks, conceptualized along a risk/protective continuum, in mediating the association of tobacco use with alcohol and other drug use. The present study addresses gaps in the literature through examining social networks’ mediating function on tobacco’s association with alcohol and drug use. Results have the potential to inform prevention science in advancing social operational models of substance use within adolescents.

Tobacco Use and Association with Substance Use

In 2007, 12.4 percent of the U.S. population who are 12 to 17 years old (3.1 million people) used a tobacco product at least once in the month prior to being interviewed in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (SAMHSA, 2009). Adolescent smoking patterns can vary by gender, race/ethnicity, and grade in school: males, white students, and students in higher-grade levels are among those most likely to smoke (Kann et al., 2000). An important social influence on child and adolescent smoking development is from peers and family members. Both peer and parent smoking have been shown to affect youth smoking rates, though the relative influence of these factors is unclear. Additionally, basic neurological research suggest that adolescence is a critical developmental period characterized by enhanced neurobehavioral vulnerability to nicotine, in which substance use has distinct effects responsible for the development of dependence later in life (Adriani, et al., 2003).

Previous research has indicated that cigarette smoking in particular, rather than alcohol use, is associated with elevated odds of subsequent cannabis use (Korhonen et al., 2008). The gateway hypothesis (i.e. smoking leads to the use of other substances) is predicated upon a sensitivity mechanism that assumes that the use of one substance primes an organism for use of another substance, thereby making the adolescent more primed or sensitive for future substance use (Kandel, Yamaguchi, & Klein, 2006). Specifically, early initiators of cigarette smoking have a particularly high risk for subsequent use of cannabis (Golub and Johnson, 2001; Korhonen et al., 2008).

Social and Psychological Mechanisms of Substance Use

Social Networks and Substance Use

Research on social networks has suggested that peer context is a robust predictor of adolescent substance use (Mayes & Suchman, 2006; Unger, & Chen, 1999; Valente, Unger, & Johnson, 2005). Specifically, social network research focused on the processes of adolescent substance use uptake has identified two distinct social-behavioral mechanisms: (a) peer selection, in which adolescents associate with others based on their prior behaviors, such as substance use, and (b), social influence, in which substance use is a product of peer use (Bauman & Ennett, 1994; Hussong, 2002). However, recent research has integrated these mechanisms with prospective studies providing support for the influence of both mechanisms on substance use (Cotterell, 2007; Curran, Stice, & Chassin, 1997; Hoffman et al., 2007; Kirke, 2006). Our approach acknowledges both peer selection and influence as integrative constructs in understanding adolescent substance use.

Social network research on adolescent substance abuse has been largely approached through single settings to acquire full network data, such as within school systems. These studies have contributed to our understanding of network structure, and size and the association with tobacco and substance use, yet this approach has rarely taken account of the varying contexts beyond the school setting from which these relations develop and are nurtured, e.g., work, non-school sports and activities, religious activities, neighborhoods, and interacting with peers from other schools. Toward this end we are utilizing egocentric social network analysis which allows the free-listing of peers in their network regardless if they attend the same school as the ego (participant). Egocentric social network analysis has shown to be a reliable indicator of youth social network characteristics at the aggregate level (number of friends, test-retest reliability (Cronbach’s .90) and behavioral level (drug use, sexual partners) with test-retest reliability (Cronbach’s .89 and .86 respectively) (Clair, Schensul, Raju, Stanek, & Pino, 2003).

The role of gender is related to social networks and substance use. Studies have explained increases in substance use in girls in terms of disturbances in their social relationships that may influence substance use in the form of self-medication (Wills et al., 2002; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2006). This research suggests that girls are more likely than boys to derive psychologically relevant information about themselves and others through interpersonal relationships. Hence, they are more vulnerable when they encounter interpersonal distress and often experience increased disturbance when their relational ties, such as friends, are threatened. Our recent research has highlighted gender and age differences, demonstrating that younger adolescents’ protective social networks (less substance using peers and high risk behaviors) reduced their likelihood of substance use relative to older males, indicating that social processes of risk and protection may be operating differently among male and female younger and older adolescents (Mason et al., 2010; Mennis and Mason, in press).

Mental Health and Adolescent Substance Use

A substantial body of research documents the relationship between mental health and the use of substances among adolescents (Costello, Erkanli, & Federman, 1999; Kandel et al., 1999; Grella, Hser, Joshi, & Rounds-Bryant, 2001). Of particular relevance to the present study, many urban youth are disproportionately exposed to trauma (e.g., violence, crime), which increases vulnerability to tobacco use (Feldner, Leen-Feldner, Trainor, Blanchard, & Monson, 2008; Hebert, 2008) and to other substance use (Costello, Erkanli, Fairbank, & Angold, 2002; Acierno, Kilpatrick, Resnick, Saunders, Arellano, Best, 2003). Specifically, early exposure to trauma and subsequent development of PTSD symptoms can interfere with emotional regulatory tasks and lead to further internalizing problems (Lubit, 2005; Mayes & Suchman, 2006). Research on the unique stressors that are placed upon urban youth who reside or are active in high-risk settings suggests that coping with these stressors can lead to smoking uptake which can then lead to substance use initiation (Costello et al., 2002). These negative coping strategies increase the likelihood of associating with peers who have similar coping strategies, lack adherence to conventional societal norms, and are more accepting of substance use as a coping or social activity (Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, Cleary, & Shinar, 2001; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992).

Coping Strategies and Family Relationships

One of the most critical resources for external protection from trauma events during times of vulnerability are family-related, such as close family relationships, parental warmth, and increased attention from family. These family resources reduce PTSD levels and act as protective factors against negative outcomes (Bokszczanin, 2008), whereas emotionally strained family environments can serve as contributing factors to psychological challenges resulting from trauma exposure (Cohen Berliner, & Mannarino, 2000). Additionally, the level of conflict within the family (perceived by the child as a lack of family support) impedes the child’s recovery from trauma (Kaniasty, 2005). Pertinent to the current study, there is evidence for the relationship between family functioning and adolescent tobacco use. Family factors such as positive family relations, parental monitoring and closeness to parents act as protective factors against substance use and smoking behaviors (Hüsler & Plancherel, 2007; Picotte, Strong, Abrantes, Tarnoff, Ramsey, Kazura, & Brown, 2006). In particular, poor family relations predict initiation of experimental smoking for adolescent girls (Van Den Bree, Whitmer, & Pickworth, 2004).

Theoretical Framework

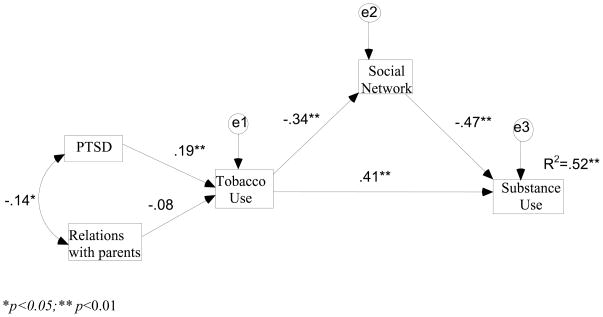

To summarize, our theoretical model which is based upon the present review of the literature and our own work, is as follows: Adolescents exposed to chronic urban environmental stress can exhibit PTSD symptoms which influence their relationship with their parents. The quality of parental relations can either exacerbate or suppress PTSD symptoms. These mental health problems can then increase the likelihood of using coping strategies such as smoking tobacco to deal with trauma and stress. The social operation of substance use uptake then occurs in two steps, much like a two-stage model of peer influence (Urberg, et al., 2003). First, smoking can lead to the selection of a like-minded high-risk peer group, one that has less pro-social group norms and is more likely to support the use of tobacco. Next, within the context of this high-risk peer group, influence to use other substances use can be understood through peer modeling of ways to cope with mental health issues such as PTSD symptoms and poor relations with parents. Substance use (alcohol and marijuana, e.g.) behaviors can be interpreted as being constituted within a selected social network that influences through peer modeling of this behavior and supported opportunities to cope with mental health and familial issues (Bandura, 1996). Thus, as a reaction to stress, mental health and parental relations influence the use of tobacco as a coping mechanism. This behavioral choice operates on the selection and subsequent influence of peers who use tobacco as well as other substances. Figure 1 shows a model representing our theoretical explanation, with the timing of pathways as well as the placement of moderating and mediating variables.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of variable relationships and timing of hypothesized progression of outcome.

Based upon the literature reviewed and the proposed theoretical model, this study investigated whether social network quality (level of risk or protection) would mediate the affects of tobacco use, accounting for PTSD symptoms and relations with parents, on substance use. We have several specific hypotheses:

PTSD symptoms and Tobacco Use are negatively correlated with Relations with Parents.

PTSD is positively correlated with higher Tobacco Use.

Tobacco Use is positively correlated with Substance Use.

The relationship between Tobacco Use and Substance Use is mediated by Social Network Quality, where greater Tobacco Use is associated with riskier Social Network Quality.

The mediating effect of Social Network Quality would differ across gender and age groups.

METHODS

Participants

The sample comprised 301 adolescent primary care patients at a Philadelphia Department of Public Health, health care center. The sample was 87% African American and 13% self-identified as mixed or other race/ethnicity, with the majority (60%) female, and a mean age of 17. The high rate of African American teens is representative of the urban area served by the health care center. Nearly one third- 32% - of subjects were living below the poverty line and 14 % were on public assistance. Participants were eligible for the study if they met the requirements of age (13–20 years), Philadelphia residence, freedom from major mental health disturbance (active psychosis would exclude a patient from completing the interviews), literacy or fluency in English, and for minor patients, be accompanied by a parent or legal guardian capable of providing informed consent.

Procedure

Parents or guardians of all adolescent patients were approached in the clinic waiting area, the study was explained, and eligibility screening questions were asked. Families who met eligibility requirements were recruited to participate in the study. Adolescents over 18 were approached directly while they waited for their appointments. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents and/or adolescent participants. Nominal incentives ($20.00 gift card) were used to acknowledge participants’ time and effort and the study’s consent rate was 90%. Measures were administered in private (i.e., in a separate room from parents to protect patient confidentiality and obtain more valid data) and the procedure generally lasted 45 minutes or less. The first author’s university and the city of Philadelphia Health Department’s institutional review boards approved the research protocol and the study received a federal certificate of confidentiality.

Measures

All assessments were conducted by trained interviewers who completed a training protocol that included role-play training and ongoing weekly supervision to ensure the collection of high-quality data. Individual background characteristics such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and social economic status of all participants were assessed.

Substance Involvement Measure

Substance involvement was measured with the Adolescent Alcohol and Drug Involvement Scale (AADIS) (Moberg, & Hahn, 1991). The AADIS has favorable internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha .94), correlates highly with self-report measures of substance use (r =.72) and with clinical assessments (r = .75), with subjects’ perceptions of the severity of their own drug use problem (r = .79), and had a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 for the present study. Higher scores represent greater levels of alcohol and drug involvement, with scores of 37 and above indicating increased likelihood of a DSM-IV-TR criteria being met for abuse or dependency.

Tobacco Use Measure

Tobacco use was collected using the tobacco history section of the AADIS that measures smoking tobacco (cigarettes and cigars) use with a single item and eight possible responses: Never used, (0) tried but quit, (1) several times per year, (2) several times a month, (3) weekends only, (4) several times per week, (5) daily, (6) several times per day, (7). Higher scores represent greater levels of tobacco use.

Social Network Measure

Social network data was gathered using the Adolescent Social Network Assessment (ASNA) (Mason, Cheung, & Walker, 2004). The ASNA captures information on each person’s close personal contacts, their strong ties which constitute their social networks. The ASNA has favorable internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha .84) and correlates significantly in the expected direction with self-report measures of substance use (r =.−64), with self-report alcohol use (r = −66), and with self-reported marijuana use (r =. −54). Adolescents are asked to name the people with whom they have contact at least once per month and with whom they have a “meaningful relationship.” Respondents provided health risk information on up to five alters, which research has shown to be an average number (Mason, et al., 2004). Subjects are asked whether they know if each alter uses substances and how often and whether they have been directly or indirectly influenced to use or not to use substances by each alter. This item has been shown in past research to be an important influence on behavior (Valente, et al., 1997). Subjects are asked about positive activities such as receiving help with school, work, or transportation and talking through problems or providing support. Negative activities include substance use, illegal activities, violence, or high risk sexual activity (sex with no condom, sex with a person with HIV/AIDS or of unknown HIV status). These procedures follow those widely used and accepted in the social network field (Burt, 1984, 1992; Brewer, 2000; Cotterell, 2007; Liebow, et al, 1995; Marsden, 1990; Valente, 2003; Vehovar, et al., 2008).

Responses are given weighted values of 1–6 forming a possible range of −70 to 70, with higher scores indicating more protection and lower scores indicating more risk. Weights were based upon research that has shown risk for substance use increases with one substance user in a network, and risk for mental health problems is elevated with one daily substance user in a network (e.g., three-fold increase) (Mason, 2009; Mason, et al., 2004). Given these data, the following weighted scoring procedure was developed: Risk quality: substance user = −1, daily user = −3, negative activity = −4, influence to use =−6 and Protective Quality: non-substance user =4, absence of negative activities =4, influence not to use =6. The potential total score per alter is ± 14, for grand total per adolescent of ± 70 (± 14 × 5= ±70).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) measure

Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms were measured with Primary Care- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PC-PTSD) Scale. The PC-PTSD is a four-item screen (Cronbach’s alpha .93) that was designed for use in primary care and other medical settings. The PC-PTSD has a test-retest Pearson’s correlation coefficient of .83 (p<.001), correlates highly with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) .83 (p<.001), and has an overall diagnostic accuracy of 85% (Prins et al., 2004).

Relationship with Parents Measure

The Relations with Parents scale within the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC-2) Self-Report of Personality was used to used to measure adolescents’ perception of being important in the family, the status of the parent-child relationship, and the teen’s perception of the degree of parental trust and concern (Cronbach’s alpha .89) (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). For the present study, the general, combined-sex norm group was used. Reliability is strong with the BASC having internal consistency scores of composites with alpha coefficients ranging from the low to mid 0.90s. The scale produces continuous data with higher scores indicating better family relationships; lower scores indicate a greater level of family problems.

Analytic Plan

The overall goal of the analysis was to test whether social network quality mediates tobacco affects on alcohol and drug use (referred to as substance use), while accounting for PTSD symptoms and relations with parents. Zero order correlations were conducted among the primary variables of interest. To determine whether the association of tobacco use with substance use was mediated by social network quality, a path model was tested using AMOS (Version 17) employing Maximum Likelihood estimation. The data were tested for multivariate normality with AMOS Mardia’s measure of multivariate kurtosis procedure and produced a coefficient of 2.623, indicating no violation of the assumption of multivariate normality.

In order to empirically test model invariance by gender and age groups (13–16 and 17–20 years of old), multi-group path analyses were conducted, to determine our model’s fit with each group. Four separate data sets were created based on gender and age groups. Each data set was tested twice, where initially all parameters were fixed to be invariant across gender and age groups. Following, all parameters were free to vary across all groups (Byrne, 2004). If the chi-square difference statistic did not reveal a significant difference between the original and the constrained-equal models, then we would reasonably conclude that the model has structural invariance across groups, that is, the model applies equally across groups (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). All missing data (<1% of cases by group) were imputed through AMOS regression imputation maximum likelihood procedure (Blunch, 2008). Bootstrapping employing 1000 samples was used for testing significance of the mediated effects and to produce bias-corrected percentile confidence intervals (MacKinnon, 2008).

RESULTS

Model Invariance

The initial multi-group test of invariance (constrained) examined both the gender and then the age models to determine whether regression structural weights for variables were the same in value across groups. The test on the gender model revealed a very good fit to the data, with a nonsignificant chi-square [χ2 (13, N= 301) = 13.78, p =0.389] indicating no significant difference between the hypothesized model and the data. Based upon Hu and Bentler’s (1999) recommendations, the fit indices selected for further evaluation of the model included root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA, recommended level <0.10; obtained = 0.01), the normed fit index (NFI, recommended level >.0.90; obtained = 0.95) and the comparative fit index CFI, recommended level >.0.95; obtained = 0.99). The test on the age model also revealed a very good fit to the data, [χ2 (13, N= 301) = 18.39, p =0.143], RMSEA (0.02), NFI (0.97) and the CFI (0.99). Next, models were examined without restrictions on parameters. The test on the gender model revealed a very good fit to the data, [χ2 (8, N= 301) = 9.14, p =.330], RMSEA (0.02), NFI (0.97) and the CFI (0.99). The test on the age model also revealed a very fit good to the data, [χ2 (8, N= 301) = 11.93, p =.154], RMSEA (0.04), NFI (0.95) and the CFI (0.98). Finally, a test of differences between groups showed no significant differences between free and fixed models, assuming the free model to be correct for gender [Δχ2 (5) = 6.458, p>.05] or for age [Δχ2 (5) = 4.644, p>.05], indicating that these groups are statistically indistinguishable. Based on these results one path model was used for testing with the entire sample.

Descriptive Statistics & Correlations

Substance use scores ranged from 0–67, with a mean score of 18.5, (SD=18.3) with 11% reporting weekly or daily use, and 18% reporting at-risk levels of substance use, that is, likely to qualify for substance abuse or dependency. Tobacco use scores ranged from 0–7, with an overall mean score of 1, and a mean score of .96 (SD= 2.0). PTSD scores ranged from 0 to 4, with a mean score of 1.5 (SD= 1.4), with 51% in the at-risk range (90th percentile) as determined by the PC-PTSD measure. Social Network Quality scores ranged from −70 to 70, with a mean score of 36.3 (SD=26.8). Relations with Parents scores ranged from 24 to 68, with a mean of 47.2, (SD= 10.5) with 25% in the at-risk range (90th percentile).

Zero order correlational analysis produced significant coefficients among path model variables in the expected direction . Table 1 displays all correlations and significance levels. PTSD and Relations with Parents was negatively correlated, confirming our first hypothesis. Only Relations with Parents and Tobacco Use was not significant, although the sign was in the expected direction (negative).

Table 1.

Inter-correlations among model variables, controlling for gender and age

| Substance Use | Social Network Quality | Tobacco Use | PTSD | Relations with Parents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Use | - | ||||

| Social Network Quality | −.530** | - | |||

| Tobacco Use | .504** | −.254** | - | ||

| PTSD | .164** | −.166* | .183** | - | |

| Relations With Parents | −.137* | .070 | −.112* | −.137* | - |

p<0.05;

p<0.001

Path Model

Results of path modeling analyses showed that our model provided a very good overall fit to the data and demonstrated partial mediation affects of social network quality on substance use. Figure 2 shows the path model with direct standardized coefficients. The chi-square was not significant [χ2 (4, N= 301) = 6.619, p =0.157]. Fit indices included root-mean-square error of approximation (0.047), the normed fit index (.97), and the comparative fit index (0.99). The direct standardized effect of tobacco use on substance use was .41 (p <0.01). The standardized mediated effect of tobacco use on substance use, mediated by social network quality was 0.16 (p <0.01; 95% confidence interval [CI] =.107, .225). Fifty-two percent of the variance in substance use was accounted for by the model. An effect-size measure was applied to determine what proportion of the total effect is mediated by the intervening (social network quality) variable. This effect size measure is adequate if all estimates are statistically significant and is used with a single mediator model (MacKinnon, 2008). Referred to as the R2 proportion, it represents the squared correlation between X (predictor variable tobacco use) and M (mediating variable social network quality, −.34), times the squared partial correlation between M and Y (dependent variable substance use, −.47), divided by the total amount of variance in the Y explained by both M and X (R2=.52). The R2 proportion was calculated and produced an effect size of 0.31, indicating a moderate effect of social network quality on tobacco influence on substance use.

Figure 2.

Path model predicting substance use (n=301).

DISCUSSION

The findings from the present study suggest that for these urban adolescents, social network quality partially mediates the affects of tobacco use on alcohol and drug use, while accounting for PTSD symptoms and relations with parents. Unique to this study is the analysis of urban adolescents’ social network quality in detail and the inclusion of multiple domains of adolescent life (psychological, family, and social) within a path model. These findings support the social operational hypothesis that the effects of tobacco use on substance use can be at least partially mediated by social networks. The finding concluded by the multi-group analysis contradicted our hypothesis of group differences by gender and age, indicating no significant difference between groups. However, the robust fit of the path model adds confidence to the claim that a social approach to addressing the linkage between tobacco and substance use for urban youth is warranted.

In examining the exogenous variables first, a significant negative correlation exists between PTSD symptoms and Relations with Parents variables. Recall that this sample’s elevated level of PTSD symptoms is likely indicative of living in a highly stressful urban environment. One half of the sample (51.5%) endorsed two out of four PTSD items, compared to estimates of six-month PTSD prevalence rates of 4–6% for the U.S. adolescent population, based upon DSM-IV criteria (Kilpatrick, et al., 2003). While not proven longitudinally in our study, the significant negative correlation between PTSD and the Relations with Parents variable, suggest increased PTSD symptoms are associated with a worsening child-parent relationship. We speculate that the quality of parental relations may exacerbate PTSD symptoms and may lead to the negative coping behavior of tobacco use. A highly significant coefficient between PTSD and tobacco use provides some support to our theory. In contrast, it appears that the relationship between the relations with parents variable and tobacco use is very weak and insignificant for this sample. PTSD may serve as a moderating variable between relations with parents and tobacco use. This is an empirical question that we did not model at this time. However, given the elevated PTSD symptoms for this sample, these findings could suggest that these adolescents are using tobacco as a way to cope with their stress. It is important to note however, that this speculation, while theoretically sound, was not directly tested within study design.

The significant negative coefficient between tobacco use and social network quality could be illustrative of selection effects of social networks on substance use. While these data cannot demonstrate direction of our model, it is reasonable that smoking is related to teens’ social network quality (level of risk and protection). For example, we speculate that the more adolescents smoke, the more risky their network becomes. In contrast, the less they smoke, the more their networks are protective. So, smokers are selecting risky, more anti-social networks, and the teens who are smoking less are selecting more protective, pro-social networks. The next step in our theory is peer influence. One explanation of the large and significant coefficient between social network quality and substance use, is that this pathway is illustrative of peer influence effects. For example, consider that smoking is a behavioral mechanism that operates on the selection effects for their social networks. Perhaps these adolescents are more likely to select a group of peers based upon similarities that include tobacco use status. This then serves as an entrance criterion into a peer group that will either support more substance use to cope with PTSD and family-based stressors or will support and provide opportunities to cope in a more pro-social manner. In either case, we speculate that modeling-based influence is occurring at this point in the pathway, exerting effects for or against substance use.

Perhaps the most interesting finding is related to the small-to-moderate mediational effect on substance use. One explanation is that because smoking begins within the context of stress (PTSD symptoms), the urban adolescent social network serves a unique place of stress relief through a combination of smoking and peer support which has significant mediating affects on substance use. We speculate that these adolescents may be smoking to cope with their PTSD symptoms and the associated feelings of stress may be reduced through nicotine’s immediate and unique effects on the reward system within the adolescent brain (Adriani, et al., 2003). Future research is needed to directly test this theorizing.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings from this study. First, the study design was cross-sectional and therefore cannot fully test the causal hypotheses that were advanced. In particular, when examining adolescents, being able to estimate the duration and malleability of these findings across developmental periods would be beneficial. Second, the social network assessment, while extensive in many regards, was limited to the adolescent report of their peers’ substance use. If full network data were available, linking self-reporting substance use status of peers to the adolescent would provide a stronger determination of peer substance use. Research with adolescents outside of school settings makes capturing full network data extremely difficult and could not be done with our sample located within a primary health care setting. Third, we cannot say definitively whether the differential influence of the peer and family variables was due to true differences of influence between these variables or because of measurement differences. While the family variable assessed teen perceptions of support and warmth, the network measure primarily assessed risky behavior. The different focus could be confounding the results. Finally, we used one item to measure tobacco use, clearly having more data on tobacco initiation, detailed counts of use quantity, and intentions for future use would strengthen the study.

Despite these limitations, this study was based upon a sound theoretical model, utilized strong analytic strategie, s and therefore has value in advancing the theoretically driven literature. These findings have promise to inform future prevention research efforts in the direction of social network quality and its meditational effects with urban teens. The present cross-sectional research indicates that more sophisticated designs addressing causation related to PTSD, parental relations, tobacco use, and peer influence/selection on substance use are warranted so that causal hypotheses regarding these mechanisms may be longitudinally tested. Based on the present study, future investigations into social networks’ effects could confirm the specific risk and protective mechanisms that interact with desired outcomes within a social operational model. These findings in turn, could specify targeted prevention programming that could tailor interventions to address substance use and abuse among adolescents.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Mason, Education & Human Services, Villanova University, Villanova, PA

Jeremy Mennis, Email: Jmennis@temple.edu, Geography & Urban Studies, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA.

Christopher D. Schmidt, Email: Christopher.schmidt@villanova.edu, Education & Human Services, Villanova University, Villanova, PA

References

- Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Arellano MD, Best CL. Assault, PTSD, family substance use, and depression as risk factors for cigarette use in youth: Findings from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:381–396. doi: 10.1023/A:1007772905696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriani W, et al. Evidence for Enhanced Neurobehavioral Vulnerability to Nicotine during Periadolescence in Rats. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(11):4712–4716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04712.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. The primacy of self-regulation in health promotion. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2005;54:245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Cognitive Theory of Human Development. In: Husen T, Postlethwaite TN, editors. International encyclopedia of education. 2. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1996. pp. 5513–5518. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman K, Ennett S. On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: Commonly neglected considerations. Addictions. 1996;91:185–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blunch N. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling Using SPSS and AMOS. Sage Press; Los Angeles, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bokszczanin A. Parental support, family conflict, and overprotectiveness: Predicting PTSD symptom levels of adolescents 28 months after a natural disaster. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2008;21(4):325–335. doi: 10.1080/10615800801950584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS. Network items and the general social survey. Social Networks. 1984;6:293–339. [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS. Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer DD. Forgetting in the recall-based elicitation of personal and social networks. Social Networks. 2000;22:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. Testing for Multigroup Invariance Using AMOS Graphics: A Road Less Traveled. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2004;11(2):272–300. [Google Scholar]

- Clair S, Schensul J, Raju M, Stanek E, Pino R. Will you remember me in the morning? Test-retest reliability of a social network analysis examining 355 HIV-related risky behavior in urban adolescents and young adults. Connections. 2003;25(2):88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Berliner L, Mannarino AP. Treating traumatized children: A research review and synthesis. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse: A Review Journal. 2000;1:29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: Effect of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Alaattin E, Fairbank JA, Angold A. The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:99–112. doi: 10.1023/A:1014851823163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterell J. Social Networks in Youth and Adolescence. New York: Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Stice E, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent alcohol use and peer alcohol use: A longitudinal random coefficients model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:130–140. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RCME, Knibbe RA. Young people’s alcohol consumption from a European perspective: Risks and benefits. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;54 (Suppl 1):s52–s55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cail L, Durant RH. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Faris R, Hipp J, Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Cai L. Peer smoking, other peer attributes, and adolescent cigarette smoking: A social network analysis. Prevention Science. 2008;9(2):88–98. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Leen-Feldner EW, Trainor C, Blanchard L, Monson CM. Smoking and posttraumatic stress symptoms among adolescents: Does anxiety sensitivity matter? Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1470–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. Variation in youthful risks of progression from alcohol and tobacco to marijuana and to hard drugs across generations. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:225–232. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella C, Hser Y, Joshi V, Rounds-Bryant J. Drug treatment outcomes for adolescents with comorbid mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2001;189:384–392. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins D, Catalano R, Miller J. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert R. What’s new in Nicotine & Tobacco Research? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(7):1113–1119. doi: 10.1080/14622200802239298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B, Monge P, Chou C, Valente T. Perceived peer influence and peer selection on adolescent smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1546–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hüsler G, Plancherel B. Social integration of adolescents at risk: Result from a cohort study. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2007;2(3):215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Differentiating peer contexts and risk for adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Grunbaum JA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance-United States, State and local YRBSS Coordinators. Journal of School Health. 2000;70(7):271–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Johnson J, Bird H, Weissman MM, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, et al. Psychiatric co-morbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: Findings from the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent General Psychiatry. 1999;57:261–269. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Klein LC. Testing the gateway hypothesis. Addiction. 2006;101:470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K. Social support and traumatic stress. PTSD Research Quarterly. 2005;16(2) [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirke DM. Teenagers and substance use: social networks and peer influence. London: Kluwer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen T, Huizink AC, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Role of individual, peer and family factors in the use of cannabis and other illicit drugs: a longitudinal analysis among Finnish adolescent twins. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebow E, McGrady G, Branch K, Vera M, Klovdahl A, Lovely R, Mueller C, Mann E. Eliciting social network data and ecological model-building: Focus on choice of name generators and administration of random-walk study procedures. Social Networks. 1995;17:257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lubit R. Diagnosis and treatment of trauma in children. In: Cheng K, Myers K, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry: The essentials. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden PV. Network data and measurement. Annual Review of Sociology. 1990;16:435–463. [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ. Social Network Characteristics of Urban Adolescents in Brief Substance Abuse Treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2009;18:1. [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Cheung I, Walker L. Substance Use, Social Networks and the Geography of Urban Adolescents. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39:10–12. 1751–1778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Valente T, Coatsworth JD, Mennis J, Lawrence F, Zelenak P. Place-Based Social Network Quality and Correlates of Substance Use Among Urban Adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Neeman J, Gest SD, Tellegen A, Gramezy N. The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Development. 1995;66:1635–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes L, Suchman N. Developmental pathways to substance abuse. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology. Risk, Disorder, & Adaptation. Vol. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 599–619. [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Mason M. Social and Geographic Contexts of Adolescent Substance Use: The Moderating Effects of Age and Gender Social Networks. Social Networks in press. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg DP, Hahn L. The adolescent drug involvement scale. Journal of Adolescent Chemical Dependency. 1991;2:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Percy A. Moderate adolescent drug use and the development of substance use. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Picotte DM, Strong DR, Abrantes AM, Tarnoff G, Ramsey SE, Kazura AN, Brown RA. Family and peer influences on tobacco use among adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194(7):518–523. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000224927.64723.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, et al. The Primary Care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2004;9(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. Behavior Assessment System for Children. 2. Bloomington: Pearson Assessments; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silbereisen RK, Reitzle M. On the constructive role of problem behaviour in adolescence: Further evidence on alcohol use. In: Lipsitt LP, Mitnick LL, editors. Self-regulatory behaviour and risk taking: Causes and consequences. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1991. pp. 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2009. NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Chen X. The role of social networks and media receptivity in predicting age of smoking initiation: A proportional hazards model of risk and protective factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg K, Luo Q, Pilgrim C, Degirmencioglu S. A two-stage model of peer influence in adolescent substance use: Individual and relationship-specific differences in susceptibility to influence. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1243–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Watkins S, Jato MN, Van der Straten A, Tsitsol LM. Social network associations with contraceptive use among Cameroonian women in voluntary associations. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente T. Social networks’ influence on adolescent substance use: An introduction. Connections. 2003;25(2):11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Valente T, Unger J, Johnson A. Do popular students smoke? The association between popularity and smoking among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 2000;3:4–69. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bree MBM, Whitmer MD, Pickworth WB. Predictors of smoking development in a population-based sample of adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(3):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehovar V, Manfreda K, Koren G, Hlebec V. Measuring ego-centered social networks on the web: Questionnaire design issues. Social Networks. 2008;30:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, Shinar O. Coping dimensions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:309–323. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM. Stress and smoking in adolescence: A test of directional hypotheses. Health Psychology. 2002;21(2):122–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Crick N, Shirtcliff E, Woods K. The origins and development of psychopathology in females and males. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology. Theory & Method. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 76–138. [Google Scholar]