Abstract

Cyanobacteria (83 strains and seven natural populations) were screened for content of apoptosis (cell death)-inducing activity towards neoplastic cells of the immune (jurkat acute T-cell lymphoma) and hematopoetic (acute myelogenic leukemia) lineage. Apoptogenic activity was frequent, even in strains cultured for decades, and was unrelated to whether the cyanobacteria had been collected from polar, temperate, or tropic environments. The activity was more abundant in the genera Anabaena and Microcystis compared to Nostoc, Phormidium, Planktothrix, and Pseudanabaena. Whereas the T-cell lymphoma apoptogens were frequent in organic extracts, the cell death-inducing activity towards leukemia cells resided mainly in aqueous extracts. The cyanobacteria were from a culture collection established for public health purposes to detect toxic cyanobacterial blooms, and 54 of them were tested for toxicity by the mouse bioassay. We found no correlation between the apoptogenic activity in the cyanobacterial isolates with their content of microcystin, nor with their ability to elicit a positive standard mouse bioassay. Several strains produced more than one apoptogen, differing in biophysical or biological activity. In fact, two strains contained microcystin in addition to one apoptogen specific for the AML cells, and one apoptogen specific for the T-cell lymphoma. This study shows the potential of cyanobacterial culture collections as libraries for bioactive compounds, since strains kept in cultures for decades produced apoptogens unrelated to the mouse bioassay detectable bloom-associated toxins.

Keywords: Cyanobacteria, Apoptosis, Cell death, Leukemia, Lymphoma, Mouse bioassay, Toxic

Introduction

Cyanobacteria inhabit all prevalent terrestrial and aquatic environments [43] and are a rich source of structurally diverse bioactive compounds [37]. Cyanobacteria can form toxic blooms [38], but are also a promising source of potential anticancer agents [40] and possibly of immunosuppressive compounds [27, 31, 44].

The bloom-associated toxins (see [7, 38, 42] for reviews) attack several organs, depending on the nature of their cellular target, like the neurotoxic anatoxins, depending on preferential uptake into particular cells, like the hepatotoxic microcystins, or primary contact with specific organs, like the dermatotoxin lyngbyatoxin. It should be noted that microcystins, if introduced into cells, are able to induce rapid death of all mammalian cells [12]. Toxic blooms are also associated with the production of more general cytotoxins like cylindrospermopsin [18]. The bloom-associated toxins are commonly detected by the acute mouse bioassay, which is widely used to monitor drinking and recreational waters to prevent human and animal fatalities [6, 7].

Isolation of bioactive compounds from field collections is problematic, since re-collection of the field sample is needed if an interesting compound is present in minuscule amounts. In addition, the true producer of a bioactive compound can be difficult to identify, since field collections of cyanobacteria are often an assemblage of multiple organisms. On the other hand, established cyanobacterial culture collections constitute a sustainable source of axenic culturable cyanobacteria and a reliable resource for bioactive compounds, making such collections important within research and bioprospecting [9]. Bioactive compounds isolated from cyanobacteria have potential as pharmaceuticals with diverse applications [3, 19]. So far, the most promising drug candidates from cyanobacteria are directed against cancer cells, several cyanobacterial compounds or derivatives thereof being in clinical or preclinical trials against solid cancers [30, 35].

The present study was undertaken to obtain an overview of the apoptosis-inducing activity against T-cell lymphoma and acute myelogenic leukemia (AML) cells in cultured cyanobacteria, especially in relation to other bioactivities (e.g., mouse toxicity and protein phosphatase inhibition). In addition to providing information about the effect of long-term culturing and the frequency of apoptogens in cyanobacteria from diverse climates, habitats, and genera, the study shows the potential of cyanobacterial culture collections as a resource for immunosuppressive and anti-leukemic drugs.

Materials and methods

Laboratory cultures and field samples

The cyanobacterial strains used in the investigation (Table 1A) are maintained in the NIVA Culture Collection of Algae [9]. The classification and nomenclature of the relevant strains are according to the prevailing taxonomic systems [4, 22, 23]. The strains were grown in 1.5 l Z8 medium [24] at 20°C on a shaking table that was illuminated by fluorescent lamps (Philips Tl 65 W/33) at an intensity of 60 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Cyanobacterial biomass was harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min, lyophilized, and kept at −80°C until extraction. Larger-scale production was in vertical tubular photobioreactors with injection of compressed air-CO2 mixture. Biomasses from natural cyanobacterial populations in seven selected inland lakes were collected during bloom conditions. The material represents species from five genera (Table 1B).

Table 1.

Origin and mouse toxicity of the cyanobacterial material screened

| A. Cyanobacterial strains from the NIVA Culture Collection of Algae | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | NIVA strain | Isolated | Geographical location | Biotope | Mouse toxicitya | |

| Order: Chroococcales | ||||||

| Chroococcus sp. | CYA 330 | 1995 | Holmestrandfjorden | SE. Norway | Marine Fjord | – |

| Cyanobium sp. | CYA 230 | 1987 | Östra Kyrksundet | Åland | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Cyanosarcina sp. | CYA 386 | 1996 | Plattenberg Bay | South Africa | Seepage water | n.d. |

| Cyanothece sp. | CYA 304 | 1991 | River Atna | Mid. Norway | Lotic biotope | n.d. |

| Cyanothece aeruginosa | CYA 258/2 | 1990 | Queen Maud's Land | Antarctica | Gravel, soil | n.d |

| Merismopedia punctata | CYA 16 | 1970 | L. Steinsfjord | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | n.d. |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 57 | 1978 | L. Frøylandsvatn | W. Norway | Eutrophic lake | H |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 143 | 1984 | L. Akersvatn | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | – |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 160/1 | 1985 | L. Akersvatn | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | T |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 228/1 | 1987 | L. Akersvatn | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | H |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 475 | 2003 | L. Victoria | Uganda | Eutrophic lake | n.d |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 476 | 2004 | L. Victoria | Uganda | Eutrophic lake | n.d |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 477 | 2003 | L. Victoria | Uganda | Eutrophic lake | n.d |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 478 | 2003 | L. Victoria | Uganda | Eutrophic lake | n.d |

| Microcystis botrys | CYA 264 | 1990 | L. Frøylandsvatn | W. Norway | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Microcystis cf. novacekii | CYA 431 | 2000 | L. Victoria | Uganda | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Microcystis cf. wesenbergii | CYA 172/5 | 1985 | L. Arresø | Denmark | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Microcystis ichthyoblabe | CYA 279 | 1990 | L. Østensjøvatn | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | – |

| Microcystis viridis | CYA 122/2 | 1983 | L. Finjasjön | S. Sweden | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Synechococcus sp. | CYA 379 | 1996 | Sognefjord | W. Norway | Marine fjord | n.d. |

| Synechococcus sp. | CYA 388 | 1996 | Hadelandstjern | SE. Norway | Freshwater | n.d. |

| Synechococcus elongatus | CYA 187 | 1985 | Queen Maud's Land | Antarctica | Detritus | n.d. |

| Synechococcus nidulans | CYA 20 | <1973 | No information | T | ||

| Order: Nostocales | ||||||

| Anabaena circinalis | CYA 82 | 1980 | L. Steinsfjord | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | – |

| Anabaena flos-aquae | CYA 269/6 | 1990 | L. Frøylandsvatn | W. Norway | Eutrophic lake | H |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | CYA 83/1 | 1980 | L. Edlandsvatn | W. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | H |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | CYA 281/1 | 1990 | L. Storavatn | W. Norway | Oligotrophic lake | – |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | CYA 298 | 1990 | L. Storavatn | W. Norway | Oligotrophic lake | – |

| Anabaena spiroides | CYA 358 | 1996 | L. Balaton | Hungary | Mesotrophic lake | T |

| Anabaena subcylindrica | CYA 323 | 1993 | Fuggdalen | E. Norway | Minerval spring | n.d. |

| Anabaenopsis arnoldii | CYA 135/2 | 1984 | L. Turkana | Kenya | Great Rift Valley Lake | – |

| Aphanizomenon gracile | CYA 338 | 1994 | L. Balaton | Hungary | Mesotrophic lake | – |

| Aphanizomenon cf. klebahnii | CYA 372 | 1996 | L. Balaton | Hungary | Mesotrophic lake | n.d. |

| Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii | CYA 225 | 1984 | L. Balaton | Hungary | Mesotrophic lake | T |

| Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii | CYA 399 | 1997 | L. Balaton | Hungary | Mesotrophic lake | T |

| Cylindrospermum sp. | CYA 245 | 1988 | Spydeberg | SE. Norway | Agricultural soil | n.d. |

| Dichothrix sp. | CYA 518 | 2004 | Disko Island | Greenland | Melt water puddle | n.d. |

| Nodularia cf. harveyana | CYA 227 | <1986 | No information | – | ||

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 124 | 1983 | L. Steinsfjord | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | – |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 195 | 1985 | Queen Maud's Land | Antarctica | Lotic biotope | – |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 295 | 1990 | Ny Ålesund | Spitsbergen | Limestone gravel | n.d. |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 308 | 1990 | Ny Ålesund | Spitsbergen | Epiphytic on moss | T |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 309 | 1990 | Ny Ålesund | Spitsbergen | Epiphytic on moss | n.d. |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 512 | 2004 | Disko Island | Greenland | Melt water puddle | n.d. |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 520 | 2005 | Spydeberg | SE. Norway | Garden pool | n.d. |

| Scytonema sp. | CYA 345 | 1993 | Queen Maud's Land | Antarctica | Gravel, soil | – |

| Order: Oscillatoriales | ||||||

| Arthrospira sp. | CYA 447 | n.d. | L. Paracas | Peru | Freshwater | (T) |

| Leptolyngbya foveolarum | CYA 54 | 1975 | Spydeberg | SE. Norway | Air sample | – |

| Limnothrix redekei | CYA 106 | 1982 | L. Mälaren | Sweden | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Lyngbya major | CYA 173 | 1987 | Kajiki, Kagoshima | Japan | Garden pond | n.d. |

| Oscillatoria curviceps | CYA 149 | 1984 | Bjørndalen | Spitsbergen | Melt water | – |

| Phormidium breve | CYA 76 | 1956 | Dax | SW. France | Lake | n.d. |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 181 | 1985 | Queen Maud's Land | Antarctica | Sandfield | T |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 184 | 1985 | Queen Maud's Land | Antarctica | Melt water | T |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 203 | 1984 | Coraholmen | Spitsbergen | Moraine soil | T |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 210 | 1985 | Grumant | Spitsbergen | Boggy soil | – |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 315 | 1993 | Lier, Buskerud | SE. Norway | Greenhouse soil | – |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 448 | 1990 | Eidsvoll | SE. Norway | Seepage water | n.d. |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 454 | 2000 | Sandebukta | SE. Norway | Marine fjord | n.d. |

| Phormidium cf. formosum | CYA 110 | 1977 | River Saka | Japan | Lotic biotope | n.d. |

| Phormidium cf. subfuscum | CYA177 | 1985 | Queen Maud's Land | Antarctica | Gravel, soil | T |

| Phormidium formosum | CYA 92 | 1981 | L. Levrasjön | S. Sweden | Mesotrophic lake | N |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 21 | 1973 | Gulf of Finland | SE. Finland | Brackish water | – |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 29 | 1968 | L. Gjersjøen | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | H |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 116 | 1983 | L. Årungen | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | – |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 126 | 1984 | L. Långsjön | Åland | Dystrophic lake | H |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 127 | 1984 | L. Vesijärvi | Finland | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 11 | 1964 | L. Akersvatn | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | H |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 406 | 1998 | L. Steinsfjord | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | n.d. |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 98 | 1982 | L. Steinsfjord | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | H |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 97/3 | 1982 | L. Steinsfjord | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | H |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 407 | 1998 | L. Steinsfjord | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | n.d. |

| Prochlorothrix sp. | CYA 8/90 | 1990 | L. Mälaren | E. Sweden | Eutrophic lake | T |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 93 | 1981 | L. Gjersjøen | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | – |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 94 | 1982 | River Glåma | SE. Norway | Lotic biotope | – |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 167 | 1968 | Lough Neagh | N. Irland | Eutrophic lake | – |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 435 | 2000 | L. Victoria | Uganda | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 452 | 2000 | Sandebukta | SE. Norway | Marine fjord | n.d. |

| Pseudanabaena limnetica | CYA 80 | 1976 | L. Windermere | England | Mesotrophic lake | T |

| Pseudanabaena limnetica | CYA 276/6 | 1990 | L. Mälaren | E. Sweden | Eutrophic lake | n.d. |

| Symploca sp. | CYA 316 | 1993 | Lier, Buskerud | SE. Norway | Greenhouse soil | – |

| Tychonema bornetii | CYA 114/1 | 1983 | River Glåma | SE. Norway | Lotic biotope | – |

| Tychonema bourrellyi | CYA 33/1 | 1976 | L. Mjøsa | SE. Norway | Mesotrophic lake | T |

| B. Natural cyanobacteria populations from Norwegian inland waters collected during bloom conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant species | Natural sample | Isolated | Geographical location | Biotope | Mouse toxicitya | |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | NWS 43 | 1992 | L. Storavatn | W. Norway | Oligotrophic lake | T |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | NWS 44 | 1991 | L. Storavatn | W. Norway | Oligotrophic lake | N |

| Aphanizomenon cf. flos-aquae | NWS 46 | 1998 | L. Akersvatn | SE. Norway | Eutrophic lake | T |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | NWS 48 | 1988 | L. Frøylandsvatn | W. Norway | Eutrophic lake | H |

| Phormidium cf. formosum | NWS 45 | 1990 | Dammenbekken, Larvik | Norway | Brook | H |

| Planktothrix agardhii | NWS 49 | 1991 | L. Kalvsjøtjern | Mid. Norway | Eutrophic lake | H |

| Planktothrix agardhii | NWS 51 | 1980 | L. Helgetjern | SE. Norway | Eutrophic/mixotrophic | – |

aCode mouse bioassay: H hepatotoxic, T toxicity, N neurotoxic, – not toxic, n.d. not determined

Mouse bioassay

Female mice (Bom:NMRI) weighing 15–25 g were fed ad libitum on standard chow and treated in accordance with Norwegian law and FELASA guidelines. For toxicity testing, 50 mg of lyophilized cyanobacterial biomass was suspended in 1 ml of sterile 0.9% NaCl solution and injected intraperitoneally. Routinely, each extract was tested on two mice. Symptoms were observed and registered during the following 48 h. Hepatotoxicity and neurotoxicity were judged as previously described [1, 39].

Extraction of cyanobacterial biomass

Extraction of cyanobacterial biomass for analytical purposes was performed as described [17]. Briefly, 20 mg of freeze-dried cyanobacterial biomass was extracted sequentially in water (A extract), 70% aqueous methanol (B extract), and 1/1 (v/v) methanol:dichloromethane (C extract). The extracts were dried in a centrifugal vacuum concentrator and resuspended in 0.2 ml of water (A and B extract) or in 0.05/0.15 (v/v) ml of DMSO/water (C extract).

Cell culturing and experimental conditions

IPC-81 rat promyelocytic leukemia suspension cells [25] were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium (EuroClone® Life Sciences Division, Milan, Italy) with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated horse serum (EuroClone® Life Sciences Division, Milan, Italy). Jurkat human T-cell lymphoma suspension cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, US) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco®invitrogen cell culture, Invitrogen AS, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (EuroClone® Life Sciences Division, Milan, Italy). Culturing density was between 1 × 105 and 8 × 105 cells/ml and adjusted by dilution in fresh medium every 2–3 days. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2.

The cells were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates (0.1 ml cell suspension/well, 1.5 × 105 cells/ml) and incubated with cyanobacterial extracts or vehicle for 18 h, when the cells were fixed (1:1) in 2% buffered formaldehyde (pH 7.4) containing 0.01 mg/ml of the DNA specific fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from male Wistar rats (80–150 g) by in vitro collagenase perfusion as previously described [29, 33]. The experimental conditions were as described in [17].

Scoring of apoptotic and necrotic cell death was by microscopic (Axiovert 35 M, Zeiss) evaluation of surface and nuclear morphology [17, 32, 41]. Each extract was tested in triplicate at dilutions from a starting point corresponding to 4 mg original dryweight biomass/ml (4 mg/ml), and the LC50 (concentration needed to induce 50% cell death) determined (Table 2A, B). The extract apoptogenicity was classified as high (LC50 < 2 mg/ml), intermediate (LC50: 2–4 mg/ml), low (LC50 > 4 mg/ml; 25–49% death at 4 mg/ml), or as absent (<25% cell death at 4 mg/ml). The potency of extracts from various cyanobacterial orders and genera was compared by two-way ANOVA, and least significance difference post hoc tests with the SPSS software (Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 2.

Potency of cyanobacterial extracts to induce cell death in myelogenic leukemia cells and T-lymphoma cells

| A. Cyanobacterial strains from the NIVA Culture Collection of Algae | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | NIVA strain | Myelogenic leukemia cells (IPC-81)a | T-lymphoma cells (jurkat)a | ||||

| A extract | B extract | C extract | A extract | B extract | C extract | ||

| Order: Chroococcales | |||||||

| Chroococcus sp. | CYA 330 | – | – | – | – | – | 2.8 ± 0.04 |

| Cyanobium sp. | CYA 230 | – | – | 2.8 ± 0.17 | >4 | >4 | 1.9 ± 0.06 |

| Cyanosarcina sp. | CYA 386 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cyanothece sp. | CYA 304 | – | – | – | >4 | >4 | >4 |

| Cyanothece aeruginosa | CYA 258/2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Merismopedia punctata | CYA 16 | >4 | – | – | 4.0 ± 0.21 | >4 | – |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 57 | 2.4 ± 0.11 | – | – | – | 1.6 ± 0.49 | 2.3 ± 0.41 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 143 | 2.6 ± 0.11 | – | – | – | – | >4 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 160/1 | – | – | – | – | >4 | >4 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 228/1 | 0.34 ± 0.00 | – | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.10 | 2.8 ± 0.11 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 475 | >4 | – | – | >4 | 1.39 ± 0.15 | 1.27 ± 0.11 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 476 | >4 | – | 2.83 ± 0.22 | 2.50 ± 0.12 | >4 | >4 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 477 | 2.46 ± 0.16 | – | – | 2.05 ± 0.25 | 2.34 ± 0.38 | >4 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 478 | 2.60 ± 0.12 | – | >4 | >4 | – | 2.16 ± 0.13 |

| Microcystis botrys | CYA 264 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | >4 | – | 3.8 ± 0.18 | – | – |

| Microcystis cf. novacekii | CYA 431 | – | – | – | – | >4 | – |

| Microcystis cf. wesenbergii | CYA 172/5 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | – | – | 0.32 ± 0.00 | – | 2.4 ± 0.52 |

| Microcystis ichthyoblabe | CYA 279 | 0.37 ± 0.00 | – | 2.5 ± 0.11 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | >4 | 1.8 ± 0.07 |

| Microcystis viridis | CYA 122/2 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 2.5 ± 0.12 | – | >4 | – | >4 |

| Synechococcus sp. | CYA 379 | – | – | – | – | – | >4 |

| Synechococcus sp. | CYA 388 | 3.0 ± 0.21 | – | – | – | 2.4 ± 0.15 | 2.2 ± 0.03 |

| Synechococcus elongatus | CYA 187 | 2.4 ± 0.22 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Synechococcus nidulans | CYA 20 | – | – | – | – | >4 | 2.6 ± 0.05 |

| Order: Nostocales | |||||||

| Anabaena circinalis | CYA 82 | 2.4 ± 0.16 | >4 | – | >4 | – | >4 |

| Anabaena flos-aquae | CYA 269/6 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | >4 | – | 0.36 ± 0.00 | 2.1 ± 0.43 | 3.2 ± 0.59 |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | CYA 83/1 | >4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | CYA 281/1 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | – | – | 0.89 ± 0.16 | – | 2.6 ± 0.17 |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | CYA 298 | 0.66 ± 0.01 | – | – | 1.0 ± 0.00 | 2.2 ± 0.05 | – |

| Anabaena spiroides | CYA 358 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Anabaena subcylindrica | CYA 323 | 2.3 ± 0.37 | – | 2.5 ± 0.14 | >4 | – | 2.2 ± 0.08 |

| Anabaenopsis arnoldii | CYA 135/2 | 0.67 ± 0.01 | – | – | 2.2 ± 0.03 | >4 | – |

| Aphanizomenon gracile | CYA 338 | 0.92 ± 0.17 | >4 | – | >4 | – | >4 |

| Aphanizomenon cf. klebahnii | CYA 372 | 1.7 ± 0.28 | – | – | – | – | >4 |

| Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii | CYA 225 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | – | 4.1 ± 0.12 | 2.5 ± 0.11 | – | 2.5 ± 0.13 |

| Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii | CYA 399 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 2.5 ± 0.11 | >4 | 2.0 ± 0.12 | 3.3 ± 0.02 | 2.4 ± 0.15 |

| Cylindrospermum sp. | CYA 245 | 2.4 ± 0.19 | – | >4 | – | – | 4.1 ± 0.61 |

| Dichothrix sp. | CYA 518 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nodularia cf. harveyana | CYA 227 | >4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 124 | >4 | – | – | >4 | – | 2.5 ± 0.13 |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 195 | – | – | – | – | – | >4 |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 295 | 1.5 ± 0.04 | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.11 | >4 | 2.4 ± 0.15 |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 308 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 309 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 512 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nostoc sp. | CYA 520 | – | – | – | >4 | – | – |

| Scytonema sp. | CYA 345 | – | – | – | – | – | >4 |

| Order: Oscillatoriales | |||||||

| Arthrospira sp. | CYA 447 | 1.0 ± 0.03 | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.11 | – | – |

| Leptolyngbya foveolarum | CYA 54 | 2.8 ± 0.11 | 2.5 ± 0.11 | – | – | – | >4 |

| Limnothrix redekei | CYA 106 | 2.3 ± 0.12 | 2.5 ± 0.11 | – | – | 3.1 ± 0.04 | >4 |

| Lyngbya cf. major | CYA 173 | – | – | 1.7 ± 0.08 | – | – | 2.2 ± 0.09 |

| Oscillatoria curviceps | CYA 149 | 2.2 ± 0.13 | – | – | – | – | >4 |

| Phormidium breve | CYA 76 | 3.0 ± 0.08 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 181 | >4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 184 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 203 | 2.1 ± 0.12 | – | – | – | >4 | 2.5 ± 0.14 |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 210 | – | – | – | >4 | – | – |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 315 | – | – | – | – | – | 3.4 ± 0.58 |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 448 | – | – | – | >4 | – | – |

| Phormidium sp. | CYA 454 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Phormidium cf. formosum | CYA 110 | 2.0 ± 0.07 | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.13 | 2.4 ± 0.15 | – |

| Phormidium cf. subfuscum | CYA177 | – | – | – | – | – | >4 |

| Phormidium formosum | CYA 92 | 1.1 ± 0.13 | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.12 | 2.5 ± 0.14 | 2.4 ± 0.14 |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 21 | >4 | – | – | >4 | – | >4 |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 29 | 1.9 ± 0.02 | – | – | – | – | 3.8 ± 0.74 |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 116 | >4 | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.10 | – | – |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 126 | 2.8 ± 0.17 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 127 | 1.8 ± 0.07 | – | 4.1 ± 0.49 | 2.5 ± 0.10 | – | 2.7 ± 0.45 |

| Planktothrix agardhii | CYA 11 | 2.4 ± 0.05 | – | – | >4 | – | – |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 406 | >4 | – | – | 2.3 ± 0.10 | – | – |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 98 | 2.1 ± 0.17 | – | – | 3.0 ± 0.16 | – | – |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 97/3 | 3.5 ± 0.26 | – | – | – | – | 3.2 ± 0.46 |

| Planktothrix rubescens | CYA 407 | – | – | – | >4 | – | >4 |

| Prochlorothrix sp. | CYA 8/90 | 2.3 ± 0.11 | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.10 | 2.5 ± 0.14 | – |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 93 | 2.6 ± 0.12 | >4 | – | – | 2.9 ± 0.30 | >4 |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 94 | 0.85 ± 0.14 | – | – | – | 2.3 ± 0.16 | 2.1 ± 0.17 |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 167 | 1.9 ± 0.15 | 2.5 ± 0.10 | – | 3.9 ± 0.29 | >4 | – |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 435 | >4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 452 | 2.8 ± 0.33 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pseudanabaena limnetica | CYA 80 | 0.91 ± 0.12 | – | – | – | 2.4 ± 0.18 | 1.8 ± 0.13 |

| Pseudanabaena limnetica | CYA 276/6 | 2.4 ± 0.29 | – | – | – | >4 | 3.1 ± 0.41 |

| Symploca sp. | CYA 316 | 3.1 ± 0.10 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tychonema bornetii | CYA 114/1 | 2.2 ± 0.18 | >4 | – | – | 3.5 ± 0.11 | >4 |

| Tychonema bourrellyi | CYA 33/1 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | >4 | – | 2.1 ± 0.03 | 2.5 ± 0.12 | 2.5 ± 0.13 |

| B. Natural cyanobacteria populations from Norwegian inland waters collected during bloom conditions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant species | Natural sample | Myelogenic leukemia cells (IPC-81)a | T-lymphoma cells (jurkat)a | ||||

| A extract | B extract | C extract | A extract | B extract | C extract | ||

| Anabaena lemmermannii | NWS 43 | – | >4 | – | – | – | 2.7 ± 0.53 |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | NWS 44 | – | 2.5 ± 0.13 | – | – | >4 | 4.0 ± 0.60 |

| Aphanizomenon cf. flos-aquae | NWS 46 | – | 2.5 ± 0.13 | – | – | – | 3.1 ± 0.11 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | NWS 48 | 2.0 ± 0.16 | 2.4 ± 0.11 | – | – | >4 | 2.4 ± 0.12 |

| Phormidium cf. formosum | NWS 45 | 3.2 ± 0.25 | >4 | – | >4 | – | >4 |

| Planktothrix agardhii | NWS 49 | >4 | – | – | – | 4.0 ± 0.28 | >4 |

| Planktothrix agardhii | NWS 51 | 2.4 ± 0.13 | – | – | – | 2.7 ± 0.04 | >4 |

aCells were incubated with various concentrations of cyanobacterial extracts (A aqueous, B 70% methanol, C methanol:dichloromethane) for 18 h and scored for cell death. Values are concentration (mg original dryweight biomass/ml) of extract required to induce 50% death (mean ± SEM, n = 3). >4 signifies 25–50% cell death at 4 mg dw/ml, and – signifies <25% cell death at 4 mg dw/ml

Assay of protein serine/threonine phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity

PP2A was purified from rabbit muscle following the previously described protocol [8]. Protein phosphatase activity was measured by the release of radiolabeled phosphate from [32P]-labeled phosphohistones as previously described [13]. In brief, 0.1 ml 50 mM Hepes containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM EGTA, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM DTT, 1.25 mM MnCl2 was added either cyanobacterial extract, MC-LR or vehicle together with PP2A (8 nM). [32P]-histone (500 nM) was then added and samples were left to incubate for 10 min at 30°C before stopping the reaction by addition of TCA to 7%. The supernatant was added 0.15 ml 1 N H2SO4 containing 1 mM K2HPO4 and 0.2 ml 6% ammonium heptamolybdate in 1.4 N H2SO4. After 5 min of incubation, 0.6 ml of isobutanol was added and samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 1,100 × g for 2 min. The isobutanol fractions were collected and measured for content of [32P] by liquid scintillation.

Purification of apoptosis-inducing compounds: extraction, solid phase extraction (SPE), and reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Biomass (300 mg dryweight) was added to 25 ml water (4°C) and homogenized 6 × 30 s pulses (Polytron®Typ PT10/35, Kinematica, Switzerland). The homogenate was incubated 2 h on ice in the dark before centrifugation (40,000 × g for 15 min) and washing with 12.5 ml of water.

The strong anion exchange SPE cartridge (Sep-Pak®Accell™Plus QMA; 360 mg; Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) was conditioned with 5.5 ml of methanol, equilibrated with 5.5 ml of water, loaded with 1 ml of water extract (corresponding to 6 mg original dryweight biomass), and washed with 2.5 ml water. The load and wash eluates were pooled.

Analytes in the non-retained fractions from the anion-exchange SPE of the cyanobacterial strains CYA 225, CYA 399, CYA 94, or CYA 80 were separated on a reversed phase chromatography column with nonpolar endcapping (Kromasil®KR100-5-C18; 250 × 4.6 mm) coupled to a Merck-Hitachi LaChrom HPLC system (VWR, West Chester, USA) with a L-7455 diode array detector. The flow rate was 0.8 ml/min and a 6-min run in isocratic mode with 94/6 (v/v %) water/acetonitrile was followed by a 24-min linear gradient to 100% acetonitrile. Analytes in selected HPLC fractions were further separated isocratically with water as solvent on a reversed phase column with polar endcapping (Aquasil C18; 150 × 3 mm) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min.

Mass spectrometry (MS)

Mass spectrometry was performed on a Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-ToF) Ultima Global Mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK) equipped with a nanoflow z-spray source. Compounds in 0.5% formic acid were infused into the mass spectrometer at a flow rate of 1–2 μl/min. MS spectra were acquired in positive ion electrospray mode with a source temperature at 80°C and a capillary voltage of 3 kV. MS/MS analysis was with collision energy of 20–40 V, but otherwise had similar parameters.

Results and discussion

Apoptosis-inducing activity is frequent in cyanobacteria and is independent of their geographical origin

The cyanobacterial strains studied represented 27 genera from the orders Chroococcales, Nostocales, and Oscillatoriales harvested from various biotopes located in areas spanning polar, via temperate to tropical geographical zones (Table 1A). Seven natural populations from Norwegian freshwater blooms (Table 1B) were also studied. To assess the apoptogenic activity in the cyanobacteria, extracts of decreasing polarity were tested against jurkat T-cell lymphoma and IPC-81 rat promyelogenic leukemia cells. The jurkat T-cells are widely used to screen for immunosuppressive agents [5, 14, 21, 34], whereas the IPC-81 cells originate from the BNML rat model, which is used for studying human AML and is known to be a reliable predictor of the potential of anti-leukemic drugs (reviewed by [28]). Unlike normal cells of the myeloid lineage the IPC-81 cells can be grown in conventional medium, have very little spontaneous apoptosis [16, 25], and are sensitive to commonly used anti-leukemic drugs [15]. These cells were therefore used to assess the presence of compounds with potential to be developed as drug candidates for acute myelogenic leukemia. Both cell lines were exposed for 18 h to aqueous (A), 70% methanol (B), or dichloromethane/methanol (C) extracts of the cyanobacterial strains/populations. All but 18 of the 90 cyanobacterial samples showed apoptogenic activity towards the T-cell lymphoma (Table 2). Nine of them induced apoptosis with high potency, and 41 with intermediate potency (Table 2). We detected apoptogenic activity against AML cells in all but 23 of the 90 cyanobacteria samples tested. Twenty-two of them induced apoptosis with high potency, and 32 with intermediate potency (Table 2).

We reasoned that the variety of genera, geographical zone of origin, and biotope would reveal any correlation between these parameters and the expression of apoptosis-inducing activity in vitro. Much of the past research has been into identification of bioactive cyanobacterial compounds from tropical and sub-tropical environments. We found no correlation between the apoptogenic activity and the geographical location where the cyanobacteria had been sampled (Tables 1, 2). However, we noted that there was a correlation between cyanobacterial genera and the amount of apoptogenic activity; the seven strains with the most potent activity against T cells were all from the genera Microcystis (4) or Anabaena (3). In contrast, these genera accounted for only two of the 18 non-apoptogenic strains (Table 2). The genera Anabaena and Microcystis had also more anti-leukemic activity than Nostoc, Phormidium, Planktothrix, and Pseudanabaena (p < 0.05).

In conclusion, the apoptosis-inducing activity appears to be abundant in cyanobacteria, in particular of the genera Microcystis or Anabaena, and is independent of geographical localization.

The apoptosis-inducing activity did not correlate with the outcome of the mouse toxicity assay

The present cyanobacterial culture collection has been created mainly to chart potentially toxic blooms and 47 of the selected strains and all the natural populations had been tested in the mouse bioassay just after their isolation. Of the tested strains, 24 were negative (no toxicity observed 48 h after injection) and 30 were positive (56%). Of the positive samples, two induced signs of neurotoxicity, 12 caused liver damage, and 16 exhibited toxicity that could not be described as neurotoxic or hepatotoxic (Table 1). The outcome of the mouse bioassay was similar between Chroococcales (14 positive, 12 negative) and Oscillatoriales (16 positive, 12 negative).

By comparing the content of apoptogens against T-cell lymphoma and AML-cells and with the outcome of the mouse bioassay we expected to reveal if toxin-producing cyanobacteria were more or less likely to produce other cell death-inducing compounds. No overall correlation was observed between the outcome of the mouse bioassay and content of apoptogenic activity against either cell line (Tables 1, 2). The lacking predictive value of the mouse bioassay is illustrated by comparing the nine extracts with the strongest anti-T-cell lymphoma activity with the 18 non-apoptogenic extracts. Of the isolates in the first group, three of the six tested in the mouse assay were positive, while five of the seven isolates tested in the second group were positive (Tables 1, 2). The same was observed regarding the anti-AML activity. Among the 22 samples with high apoptogenic activity, 16 had been tested by mouse bioassay, and of these, nine were positive, while of the 23 without apoptogenic activity, 11 had been tested in mouse bioassay and six of these were positive (Tables 1, 2).

Still, we considered whether microcystin or similarly acting protein phosphatase inhibitors could be responsible for some of the anti-AML activity in the aqueous extracts, since these toxins target major protein phosphatases that are abundant in all eukaryotic cells. The hepatocytes are primary targets due to their efficient microcystin uptake [11, 26], but other cells can also be targeted at higher concentration of microcystin [2], and microinjected microcystin induces apoptosis within a few minutes in all mammalian cells tested [12]. We found that the LC50 for microcystin-LR was 200 μM for the T-cell lymphoma and 150 μM for the AML cells and we have previously shown that microcystins have a 20-fold higher apoptosis-inducing activity towards hepatocytes than towards leukemia cells, even if the leukemia cells were incubated with toxin for 18 h compared to the 1-h incubation of hepatocytes [17]. Twelve of the extracts with the highest anti-AML activity were therefore assayed for content of microcystin-like activity by the PP2A assay and some were also analyzed by HPLC/MS (Table 3). The anti-AML activity did not correlate with the microcystin content, which, as expected, correlated closely with hepatotoxicity in the mouse bioassay and the induction of apoptosis in primary hepatocytes (Table 3). The lower-than-expected activity of Microcystis CYA 264 towards hepatocytes could be explained by the content of a novel nostocyclopeptide inhibitor of microcystin-induced hepatocyte apoptosis [20]. Furthermore, the extract with the highest PP2A inhibitory content would maximally contribute 13 μM microcystin to the AML cells, and the type of apoptotic cell death observed (not shown) differed from the one induced by protein phosphatase inhibitors, which typically induce strongly polarized blebbing in various cell types [12].

Table 3.

Content of phosphatase inhibitor, toxicity to mice and apoptosis induction in hepatocytes, and AML cells in cyanobacterial extracts

| Species | NIVA strain | MC-LR equivalents (μM) | Microcystin | Toxic to mice | Apoptosis induction in primary hepatocytes | Apoptosis induction in AML cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcystis aeruginosa | CYA 228/1 | 930 | + | H | ++++ | ++++ |

| Microcystis botrys | CYA 264 | 1300 | + | n.d. | ++ | ++++ |

| Microcystis cf. wesenberghii | CYA 172/5 | 3.5 | − | n.d. | − | ++++ |

| Microcystis ichthyoblabe | CYA 279 | <0.1 | − | – | − | ++++ |

| Microcystis viridis | CYA 122/2 | 4.0 | − | n.d | − | ++++ |

| Anabaena flos-aquae | CYA 269/6 | 270 | + | H | ++++ | ++++ |

| Anabaena lemmermannii | CYA 281/1 | <0.1 | n.d. | – | − | ++++ |

| Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii | CYA 225 | <0.1 | n.d. | T | − | ++++ |

| Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii | CYA 399 | <0.1 | n.d. | T | − | ++++ |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | CYA 94 | 0.3 | n.d. | – | − | ++++ |

| Pseudanabaena limnetica | CYA 80 | <0.1 | n.d. | T | − | ++++ |

| Tychonema bourrellyi | CYA 33/1 | 3.6 | n.d. | T | − | ++++ |

Water extracts from 12 cyanobacterial isolates were assayed for content of PP2A inhibitory activity and expressed as MC-LR equivalents. Toxicity to mice and the presence of microcystin was determined in some strains by HPLC and MS. Induction of apoptosis in AML cells and primary hepatocytes by the 12 water extracts was also investigated. The scores signify: −, <10% apoptosis; +, 10–25% apoptosis; ++, 25–50% apoptosis; +++, 50–75% apoptosis; ++++, 75–100% apoptosis

We conclude that the apoptogenic activity against T-cell lymphoma and/or AML-cells could not be ascribed to known phosphatase inhibitors and that the mouse bioassay has little ability to predict the presence of AML and T-cell apoptogens. This is not unexpected if the apoptogens are targeted against the immune system or the myeloid lineage of the hematopoetic system, since life-threatening symptoms from the elimination or paralysis of these cells will not be apparent during the short period of the acute mouse bioassay. A negative response in the mouse bioassay predicts a lack of acutely acting toxins, and this might therefore be a positive trait in the search for therapeutic lead compounds.

Cyanobacterial apoptogen diversity resulted from differences between strains and the presence of more than one activity in the same strain

Several of the cyanobacteria contained more than one apoptogenic compound, since activity was detected in both the aqueous (A) and the organic (C) extract, whereas no activity was detected in the intermediate methanol (B) extract (Table 2). In addition, A and C extracts often produced apoptosis with different phenotypes (not shown).

Apoptogens against AML cells were about as prevalent as apoptogens against T-lymphoma cells. However, apoptosis-inducing activity towards AML cells was almost completely confined to the aqueous (A) extracts, whereas the apoptosis-inducing activity towards T-lymphoma cells were generally found in the organic extract (Table 2). Interestingly, we found that several strains contained both activities. For instance, the Planktothrix strains CYA 29 and 97/3 contained an apoptogen specific towards AML cells in the aqueous (A) extract and another apoptogen specific towards T-cell lymphoma cells in the organic (C) extract. In addition, two strains, Microcystis CYA 228/1 and Anabaena CYA 269/6, were proven to contain hepatotoxic microcystin in addition to apoptogens specific towards T-cell lymphoma and/or AML-cells (Tables 2, 3).

Based on the difference in polarity of the A extract and C extract, we conclude that the apoptosis-inducing activity against T-cell lymphoma and AML-cells often resided in different molecules.

The biosynthetic production of apoptogenic compounds are preserved in cyanobacteria even after long-term culturing

A potential problem in bioprospecting is the loss of biosynthetic capability for the substances of interest upon culturing of the producing organism. We noted apoptogenic activity in strains maintained in culture for several years (Tables 1, 2). For instance, Phormidium CYA 76, isolated in 1956, exhibited apoptosis-inducing activity and Microcystis CYA 264, isolated in 1990, produced substantial amounts of microcystin. When we compared the apoptogenicity of old and recent cultures, we found no indications that the recently collected strains contained more apoptogens than the formerly collected. This suggests that the cyanobacteria maintain their original biosynthetic capability after isolation and culturing, and underlines the importance of culture collections.

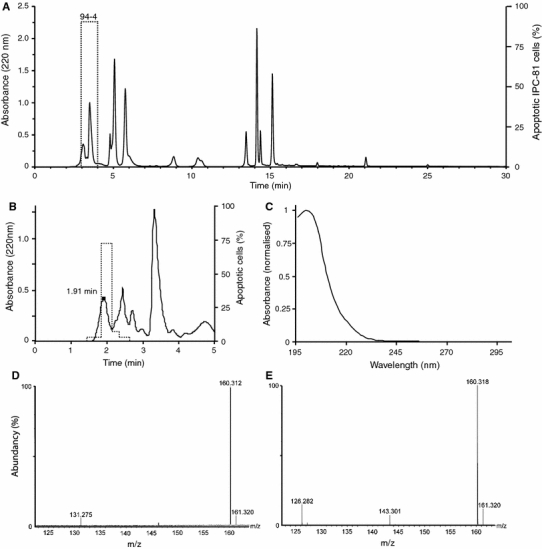

To further study the apoptogenic activity in some of the highly potent anti-AML extracts (Table 3), we performed bio-guided isolation of the water extract. After extraction and anion-exchange solid-phase extraction the apoptosis-inducing activity was highly recovered (data not shown) in four strains collected at different time-points and locations (CYA225, CYA399, CYA94, CYA80). These four strains had similar HPLC profiles, as shown for CYA94 in Fig. 1a, as well as toxin profiles (not shown). The anti-AML fraction in the beginning of the chromatogram (Fig. 1a) was further separated and the apoptosis-inducing activity found to reside in one peak (Fig. 1b) with a UV-spectrum exhibiting a λmax at 199 nm (Fig. 1c). This highly polar compound was common for both the Cylindrospermopsis strains (CYA 225 and CYA 399) and the Pseudanabaena strains (CYA 80 and CYA 94), as determined by retention time, absorbance spectra, and MS analysis. The molecular mass of the compound was 159.3 Da (Fig. 1d). This mass differs from that of known bloom-associated cyanobacterial toxins. Upon MS/MS, two fragments (m/z: 143 and m/z: 126) were created, corresponding to the loss of one and two masses of 17 Da (Fig. 1e). The fragmentation pattern was similar to that seen in some amines [36].

Fig. 1.

Analysis of apoptosis-inducing compounds by HPLC and mass spectrometry. a Analytes in anion-exchange SPE fraction of CYA 94 were separated by reversed phase HPLC. Fractions were collected and tested for the ability to induce cell death in AML cells. A major death-inducing activity eluted in fraction 4 (3–4 min) and was termed 94-4 (boxed). b The 94-4 fraction was further fractionated by polar endcapped reversed C18 phase HPLC chromatography. The bioactivity (dotted line) eluted with a peak with retention time of 1.91 min. c–e The peak (94-4-1.91) was analyzed by UV spectroscopy (c), and mass spectrometry (MS) (d) and MS/MS (e)

This demonstrates that cultured cyanobacteria, even after long-term culturing under axenic conditions, constitute a renewable source for toxins and interesting apoptogenic compounds.

Concluding remarks

This study demonstrates that cyanobacteria kept in culture not only give toxicological information but also represent a renewable source for other bioactive compounds.

There was no correlation between mouse toxicity and induction of apoptosis neither in T-cell lymphoma nor in AML-cells, which indicates that cyanobacteria produce a diversity of still uncharacterized bioactive compounds. The present findings indicate that cyanobacteria in addition to production of specific toxins like microcystin, were able to produce high levels of other cell death-inducing compounds, irrespective if collected from blooms or not.

The biosynthetic capability of cyanobacteria [10] offers an opportunity for finding novel useful compounds, as illustrated by several cyanobacterial anti-cancer agents currently under development [30, 35]. The negative mouse bioassay for many strains with high content of activity against T-cell lymphoma or AML-cells (Tables 1, 2) is in this context an advantage since it suggests that the compounds have only limited acute toxicity in the intact organism. In fact, 23 cyanobacterial strains and one natural population that were non-toxic to mice contained apoptogens. This suggests that culture collections of cyanobacteria without toxicity against mammals constitute a valuable source for bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical potential.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Norwegian Research Council (157338), Oslo, Norway, and by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority. The authors thank Nina Lied Larsen at the Institute of Biomedicine, Bergen, for culturing and preparation of cells, Randi Skulberg, curator at the NIVA Culture Collection, Oslo, for maintenance of cyanobacterial strains and Einar Solheim at PROBE, Institute of Biomedicine, Bergen, for assistance with mass spectrometry.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Berg K, Carmichael WW, Skulberg OM, Benestad C, Underdal B. Investigation of a toxic water-bloom of Microcystis aeruginosa (Cyanophyaceae) in Lake Akersvatn, Norway. Hydrobiologia. 1987;144(2):97–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00014522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botha N, Gehringer MM, Downing TG, van de Venter M, Shephard EG. The role of microcystin-LR in the induction of apoptosis and oxidative stress in Caco2 cells. Toxicon. 2004;43:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burja AM, Banaigs B, Abou-Mansour E, Burgess JG, Wright PC. Marine cyanobacteria—a prolific source of natural products. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9347–9377. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00931-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castenholz RW. Cyanobacteria. In: Garrity GM, editor. Bergey`s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 1, the Archaea and the deeply branching phototrophic Bacteria. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 473–599. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang W, McClain CJ, Liu MC, Barve SS, Chen TS. Effects of 2(rs)-n-propylthiazolidine-4(r)-carboxylic acid on 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-induced apoptotic cell death. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chorus I, Falconer IR, Salas HJ, Bartram J. Health risks caused by freshwater cyanobacteria in recreational waters. J Toxicol Environ Health. 2000;3:323–347. doi: 10.1080/109374000436364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Codd GA, Lindsay J, Young FM, Morrison LF, Metcalf JS. Harmful cyanobacteria. In: Huisman J, Matthijs HCP, Visser PM, editors. Harmful cyanobacteria. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen P, Alemany S, Hemmings BA, Resink TJ, Strålfors P, Tung HY. Protein phosphatase-1 and protein phosphatase-2a from rabbit skeletal muscle. Methods Enzymol. 1988;159:390–408. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)59039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edvardsen B, Skulberg R, Skulberg OM. NIVA Culture Collection of Algae—microalgae for science and technology. Nova Hedwig Beih. 2004;79:99–114. doi: 10.1127/0029-5035/2004/0079-0099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer WJ, Altheimer S, Cattori V, Meier PJ, Dietrich DR, Hagenbuch B. Organic anion transporting polypeptides expressed in liver and brain mediate uptake of microcystin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;203:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fladmark KE, Brustugun OT, Hovland R, Boe R, Gjertsen BT, Zhivotovsky B, Doskeland SO. Ultrarapid caspase-3 dependent apoptosis induction by serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fladmark KE, Serres MH, Larsen NL, Yasumoto T, Aune T, Doskeland SO. Sensitive detection of apoptogenic toxins in suspension cultures of rat and salmon hepatocytes. Toxicon. 1998;36(8):1101–1114. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(98)00083-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foulds LM, Boysen RI, Crane M, Yang Y, Muir JA, Smith AI, de Kretser DM, Hearn MT, Hedger MP. Molecular identification of lysoglycerophosphocholines as endogenous immunosuppressives in bovine and rat gonadal fluids. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:525–536. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gausdal G, Gjertsen BT, McCormack E, Van Damme P, Hovland R, Krakstad C, Bruserud O, Gevaert K, Vanderkerckhove J, Doskeland SO. Abolition of stress-induced protein synthesis sensitizes leukemia cells to anthracycline-induced death. Blood. 2008;111:2866–2877. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gjertsen BT, Cressey LI, Ruchaud S, Houge G, Lanotte M, Doskeland SO. Multiple apoptotic death types triggered through activation of separate pathways by cAMP and inhibitors of protein phosphatases in one (IPC leukemia) cell line. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 12):3363–3377. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herfindal L, Oftedal L, Selheim F, Wahlsten M, Sivonen K, Doskeland SO. A high proportion of Baltic Sea benthic cyanobacterial isolates contain apoptogens able to induce rapid death of isolated rat hepatocytes. Toxicon. 2005;46(3):252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoeger SJ, Shaw G, Hitzfeld BC, Dietrich DR. Occurrence and elimination of cyanobacterial toxins in two Australian drinking water treatment plants. Toxicon. 2004;43:639–649. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaspars M, Lawton LA. Cyanobacteria-a novel source of pharmaceuticals. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 1998;1:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jokela J, Herfindal L, Wahlsten M, Permi P, Selheim F, Vasconcelos V, Doskeland SO, Sivonen K (2010) Chem Biochem 11:1594–1599 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Jun DY, Kim JS, Park HS, Song WS, Bae YS, Kim YH. Cytotoxicity of diacetoxyscirpenol is associated with apoptosis by activation of caspase-8 and interruption of cell cycle progression by down-regulation of Cdk4 and cyclin B1 in human Jurkat T cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;222:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komárek J, Anagnostidis K (1999) Cyanoprokaryota, 1st part: Chroococcales. In: Ettl H, Gärtner G, Heynig H, Mollenhauer D (eds). Gustav Fisher, Jena, pp 1–548

- 23.Komárek J, Anagnostidis K (2005) Cyanoprokaryota, 2nd part: Oscillatoriales. In: Büdel B, Gärtner G, Krienitz L, Schagerl M (eds). Elsevier, München, pp 1–759

- 24.Kotai J (1972) Instructions for preparation of modified nutrient solution Z8 for algae. Blindern, Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Institute for Water Research. Report nr B-11/69

- 25.Lacaze N, Gombaud-Saintonge G, Lanotte M. Conditions controlling long-term proliferation of Brown Norway rat promyelocytic leukemia in vitro: primary growth stimulation by microenvironment and establishment of an autonomous Brown Norway ‘leukemic stem cell line’. Leuk Res. 1983;7(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(83)90005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu H, Choudhuri S, Ogura K, Csanaky IL, Lei XH, Cheng XG, Song PZ, Klassen CD. Characterization of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1b2-null mice: essential role in hepatic uptake/toxicity of phalloidin and microcystin-LR. Toxicol Sci. 2008;103:35–45. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann J. Natural products as immunosuppressive agents. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18:417–430. doi: 10.1039/b001720p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCormack E, Bruserud O, Gjertsen BT. Animal models of acute myelogenous leukaemia-development, application and future perspectives. Leukemia. 2005;19:687–706. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellgren G, Vintermyr OK, Doskeland SO. Okadaic acid, cAMP, and selected nutrients inhibit hepatocyte proliferation at different stages in G1: modulation of the cAMP effect by phosphatase inhibitors and nutrients. J Cell Physiol. 1995;162(2):232–240. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Marine natural products and related compounds in clinical and advanced preclinical trials. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1216–1238. doi: 10.1021/np040031y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasool M, Sabina EP. Appraisal of immunomodulatory potential of Spirula fusiformis: an in vivo and in vitro study. Nat Med (Tokyo) 2009;63:169–175. doi: 10.1007/s11418-008-0308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandal T, Aumo L, Hedin L, Gjertsen BT, Doskeland SO. Irod/Ian5: an inhibitor of gamma-radiation and okadaic acid-induced apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3292–3304. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seglen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. In: Prescott DM, editor. Methods in cell biology. New York: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 29–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen C, Maerten P, Geboes K, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P, Ceuppens JL. Infliximab induces apoptosis of monocytes and T lymphocytes in human-mouse chimeric model. Clin Immunol. 2005;115:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmons TL, Andrianasolo E, McPhail K, Flatt P, Gerwick WH. Marine natural products as anticancer drugs. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simo C, Moreno-Arribas MV, Cifuentes A. Ion-trap versus time-of-flight mass spectrometry coupled to capillary electrophoresis to analyze biogenic amines in wine. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1195(1–2):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivonen K, Börner T. Bioactive compounds produced by cyanobacteria. In: Herrero A, Flores E, editors. The cyanobacteria. Molecular biology, genomics and evolution. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press; 2008. pp. 159–197. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivonen K, Jones G. Cyanobacterial toxins. In: Chorus I, Bartram J, editors. Toxic cyanobacteria in water. A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring and management. London: E & FN Spon; 1999. pp. 41–111. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skulberg OM, Carmichael WW, Andersen RA, Matsunaga S, Moore RE, Skulberg R. Investigation of a neurotoxic Oscillatoriales strain (Cyanophyceae) and its toxin. Isolation and characterization of homoanatoxin-a. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1992;11:321–329. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620110306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan LT. Bioactive natural products from marine cyanobacteria for drug discovery. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:958–979. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tronstad KJ, Gjertsen BT, Krakstad C, Berge K, Brustugun OT, Doskeland SO, Berge RK. Mitochondrial-targeted fatty acid analog induces apoptosis with selective loss of mitochondrial glutathione in promyelocytic leukemia cells. Chem Biol. 2003;10(7):609–618. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00142-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Apeldoorn ME, van Egmond HP, Speijers GJ, Bakker GJ. Toxins of cyanobacteria. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:7–60. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitton BA, Potts M. The ecology of cyanobacteria: their diversity in time and space. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang LH, Longley RE. Induction of apoptosis in mouse thymocytes by microcolin A and its synthetic analog. Life Sci. 1999;64:1013–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]