Abstract

Granulomatous mastitis (GM) is an uncommon benign breast lesion. Diagnosis is a matter of exclusion from other inflammatory, infectious and granulomatous aetiologies. Here, we presented an atypical GM case, which had clinical and radiologic features overlapping with inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). The disease had multiple recurrences. The patient is a 40-year-old Caucasian woman with a sudden onset of left breast swelling accompanied by diffuse skin redness, especially of the subareolar region and malodorous yellow nipple discharge from the left nipple. The disease progressed on antibiotic treatment and recurred after local resection. A similar lesion developed even after bilateral mastectomy. GM may show clinical/radiologic features suggestive of IBC. Multiple recurrences can be occasionally encountered. GM after recurrence could be much more alarming clinically. Pathology confirmation is the key for accurate diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach is important to rule out IBC.

Background

Granulomatous mastitis (GM) is a benign and uncommon entity diagnosed by exclusion of other inflammatory, infectious, granulomatous and malignant etiologies.1 2 An effective diagnostic protocol has not yet been established to differentiate GM from IBC. It can share some clinical/radiologic features of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). GM is characterised pathologically by chronic granulomatous inflammation of the lobules without necrosis. GM sometimes can recur after appropriate treatment. There is no clear data in the literature delineating multiple recurrences of GM after multiple surgeries. GM mimicking IBC clinically upon recurrence has also not been described before. Naturally, patients and physicians would get alarmed in persistent cases with multiple recurrences. Here, we presented an atypical and unique GM case with multiple recurrences mimicking IBC during recurrence period. Our aim is to share our experience with colleagues to help establish appropriate diagnostic approach and clinical management of GM, which can recur and mimic IBC.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old G2P2 (Gravida 2 para 2) Caucasian woman visited her primary physician complaining of sudden onset of left breast swelling accompanied by diffuse erythema, especially on the subareolar region. There was malodorous, yellow nipple discharge from the left breast, which started just before the swelling and erythema. She experienced sharp shooting pains localised behind the areola that radiated toward the left axilla. Her medical history was significant for major depression and dissociative identity disorder. She does not have a history of any autoimmune or infectious or granulomatous diseases. She was on a psychotropic agent, risperidone 2–6 mg/day for almost 1 year, 10 years before her presentation. She was not on any contraceptive pill. There was no history of trauma to the breast. She has no personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Physical examination revealed a palpable lesion in the left breast and slightly prominent lymph nodes in the left axilla. A presumptive diagnosis of mastitis was made and she was then treated with a 2 week regimen of sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim. Due to persistent symptoms, she was subsequently re-evaluated. A mammogram revealed an ill-defined periareolar lesion extending into the lower outer quadrant with increased density and distortion that was approximately 5 cm in diameter. No suspicious calcifications were identified. Ultrasound showed the lesion to be hypoechoic, measuring 4.6 cm×1.8 cm×4.6 cm (figure 1). Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of a left axillary lymph node demonstrated a lymphoid hyperplasia. Core needle biopsy of the left breast lesion was interpreted as consistent with ‘nonspecific mastitis’. Her antibiotic regimen was switched to clindamycin, and then ciprofloxacin. After she completed a 1-month course of antibiotics, the symptoms remained and seemed worse. At that time, the left breast was mildly tender with a large area of induration involving the entire upper outer quadrant with erythema and some extension to the lower outer quadrant. Because of the worsening symptoms, a MRI of the breast was performed and was reported as ‘highly suspicious for malignancy’. Based on these findings, the differential diagnosis included a non-neoplastic inflammatory disease versus malignant neoplasm, possible IBC. The patient then underwent excisional biopsy of the lesion and the pathology examination showed ‘terminal duct lobular units that were surrounded by mononuclear inflammatory cells including lymphocytes and plasma cells and many multinucleated giant cells’. These findings were consistent with GM (figures 2 and 3).

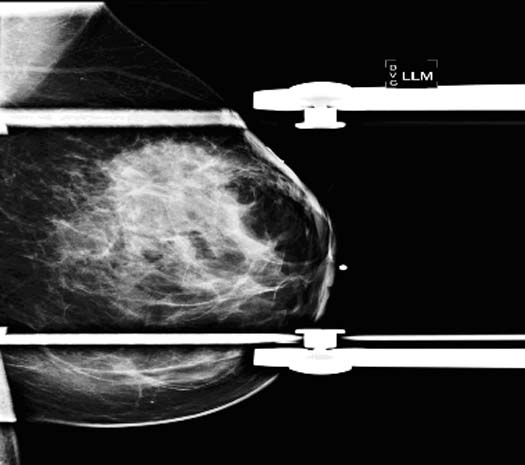

Figure 1.

Mammogram (above picture) showed a large ill-defined 5 cm area of increased density with distortion at 12:00 position. No suspicious calcifications were identified.

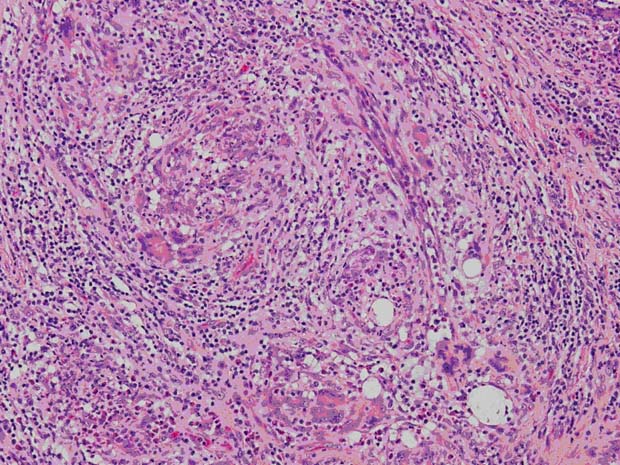

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph, H&E specimen. Fibrohistiocytic proliferation with prominent multinucleated giant cells (magnification 400×).

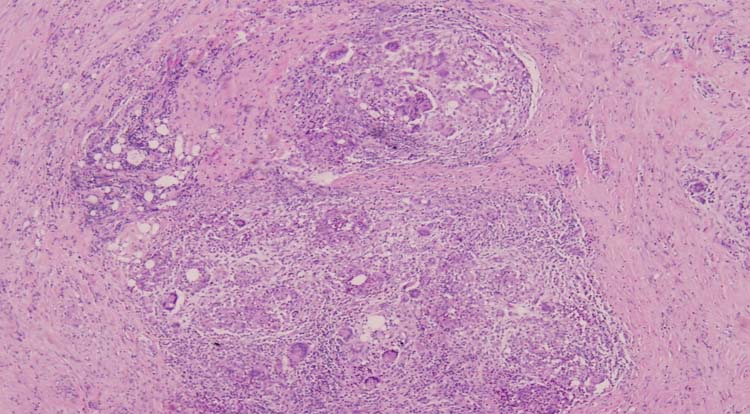

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph, H&E specimen. Granulomas and multinucleated giant cells in the mammary glandular tissue are shown (magnification 200×).

Four weeks later, the patient noticed a new growth in the site of the previous surgical resection. She was then self-referred to MD Anderson Cancer Center for further evaluation. On physical examination, she was found to have skin changes in the form of erythema and minimal peau d'orange, particularly in the medial aspect of left breast. The size of the breast was not increased (figure 4). There was a 2–3 cm area of induration and a few palpable lymph nodes in the left axilla. An ultrasound revealed a postsurgical organising seroma and an ill-defined vague hypoechoiec area. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT showed a 3 cm hypoattenuating region compatible with postoperative seroma; however, inferiorly, there was an area of abnormal metabolic activity within anatomically unremarkable breast tissue raising a concern for malignancy (figure 5). FNA sample of the area showed ‘fibrohistiocytic proliferation with prominent multinucleated giant cells’. She was further worked up for tuberculosis (TB), brucellosis and histoplasmosis. This workup included a PPD skin test, Brucella Wright test and complement fixation test for histoplasma antibody in blood. All the tests were negative. Chest x-ray and CT chest were also unremarkable. After all this long and troublesome evaluation for the persistent/recurrent lesion, the patient decided to undergo a bilateral skin sparing mastectomy at a local hospital 6 months after being evaluated at MD Anderson. Although there was no lesion on the contralateral breast, bilateral mastectomy was her personal preference. Pathological diagnosis of the mastectomy specimen of the left breast was again GM. Special stains (Acid-Fast and Grocott's Methylamine Silver stains) were negative, virtually excluding mycobacteria and fungi-related infection. Two years after the mastectomy, we received a feedback from the patient that a new pinkish area appeared in the lower inner quadrant of the left chest wall, which continued to grow with peau d’ orange appearance.

Figure 4.

Clinical picture of the patient 4 weeks after excisional biopsy which shows induration, nipple retraction and skin changes in the form of erythema and minimal peau d'orange on medial aspect of left breast, which are explained in detail in the text.

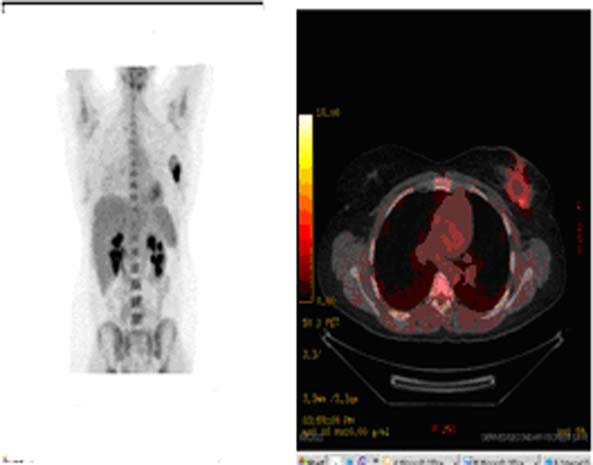

Figure 5.

PET/CT imaging demonstrating abnormal uptake in the left breast.

Discussion

GM, also known as granulomatous lobular mastitis or granulomatous lobulitis, is a rare chronic breast disease of uncertain aetiology. Galactorrhea, inflammation, breast mass, tumorous indurations and ulcerations of the skin can be the presenting symptoms.1 2

GM was originally described by Kessler and Wolloch in 1972.1 It is a diagnosis of exclusion, and pathologic examination remains the most important diagnostic tool to document the granulomatous nature and distinguish it from malignancy. Aetiology is still unknown in most patients. Some authors reported an association with autoimmune disorders, infection and trauma,3–5 while others have suggested an association with contraceptive pills, breast feeding, ethnicity and prolactinoma.3–6 The age range at diagnosis ranges from 17 to 42 years.7 GM typically appears during pregnancy, lactation or within 6 years of the most recent pregnancy but can develop up to 15 years postpartum.8 9 In our patient, GM was found 15 years postpartum.

Regarding the infectious aetiology of this disease, there have been some case reports implicating TB mastitis and Corynebacterium spp.3 The most significant differential pathological feature is the presence of caseating necrosis and acid-fast bacilli that can sometimes be isolated in TB cases, although absence of caseating necrosis does not exclude the diagnosis of TB. Shinde et al reported the most extensive case description of TB mastitis.10 They showed that a lump in the breast with or without an ulcer was the characteristic presentation, while other forms presented with diffuse nodularity and multiple sinuses. However, TB mastitis is a rare entity. Isolated breast involvement is much rarer. Our patient did not have any risk factors for TB mastitis and presentation was not typical of TB mastitis given the signs and symptoms. Microbiological and skin tests also did not show any evidence of TB.

Another bacteria involved in the aetiology of GM is corynebacteria spp. A clinico-pathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynobacteria infection and GM showed that 27 of 34 had histological or cytologic features of GM, and gram-positive bacilli were present in the tissue sections of 15 of the women.3 In our case, Gram stains and microbiological cultures did not show any evidence of corynobacteria infection.

Aside from infection, in almost all cases, GM is associated with lactational change either because of pregnancy and/or they had hyperprolactinemia associated with prolactinomas or phenothaizines. Moreover, hyperprolactinemia has also been suggested as a cause of GM.3 4 6 8 11 12 Cserni G and Szajki4 reported cases of GM following drug-induced galactorrea and trauma. Prolactin is thought to be a noxious stimulus to the breast tissue inducing granulomatous inflammation formation, but the exact mechanism is not known. Our patient had symptoms suggestive of hyperprolactinemia. It is unclear whether it was related to secondary to antipsychotic drug use or not. GM secondary to antipsychotics can be considered as a late reaction due to prolactin insult, which was likely seen in this case despite the antipsychotic use 10 years ago. This is similar to the cases of GM related to pregnancy or lactational change, which can be seen 15 years after the occurrence.

The diagnostic approach to GM should include FNA and core biopsy that can facilitate the diagnosis,13 avoiding unnecessary surgery for suspected breast cancer. Characteristic findings include multinucleated Langerhans giant cells, epithelioid hystiocytes, non-caseating granulomas, lymphocytes and neutrophils.14 Microorganism cultures and special stains are frequently negative. Among large series describing FNA features of GM in literature regarding GM, usefulness of FNA has been debated; however, authors believe that FNA biopsy plays an important role in GM diagnosis.15 Others claim that various causes of GM cannot be confidently differentiated by FNA biopsy.16 Mote et al were not able to make a definitive diagnosis of GM via FNA due to features overlapping with other diseases, including TB mastitis. Excision biopsy was required to confirm the diagnosis.17

GM patients often present with a distinct firm, hard mass involving any part of the breast; however, it tends to spare the subareolar region. Bilateral involvement is uncommon, although it has been reported in the literature.16–19 In a literature review of 49 cases, lesions were described in every quadrant of breast but the subareolar region.20 However, contrary to previous reports, Lee et al21 reported 3 out of 12 studied cases presented with subareolar involvement. In our case, the subareolar region was initially involved.

The crucial part of the differential diagnosis of GM is the similarity of the disease to IBC, because of mimicry of presentation clinically. In a case series of 20 patients with pathologically proven GM reported by Baslaim et al,12 8 patients had peau d'orange and 9 patients had nipple retraction. Moreover, 11 patients had a painful ill-defined mass, while 8 patients had skin erythema, all of which are suggestive of IBC. In a retrospective review of nine women with GM, 100% of women presented with a palpable breast mass.22 In keeping with these findings, our patient had erythema on the subareolar area, which progressed to left upper quadrant with an induration and palpable breast mass with peau d'orange appearance.

In our case, GM recurred even after local excision and, more importantly, the lesion spread on the left breast and clinical features had evolved to look like IBC at the time the patient presented to us. After being worked up for GM in our center and in other centers by infectious diseases and rheumatology departments for another couple of months, she had bilateral mastectomy upon her own wish because of the bothersome nature of the problem. Patient took this decision 6 months after her evaluation in our center when she was not feeling depressed and had been cleared by psychiatry for her competency at decision making. Two years after this surgery, she reported a new pinkish area with peau d'orange appearance on her skin of the left chest wall. We do not have a pathological diagnosis of the new lesion. However, given the similarity of the new lesion described by the patient to the skin changes before mastectomy, it is likely that this was another recurrence of GM. Recurrence of GM has been previously reported. In a retrospective review of 43 patients with histologically proven GM, 10 (23%) had recurrence of GM.23 In another review of 21 patients, the recurrence rate was 9.5 %.18 Although recurrence is common and initial presentation can be similar to IBC, evolution towards mimicking IBC, even after resection, has not been described before in the literature.

In this case, the workup included an ultrasound, chest x-ray, MRI, abdominal and chest CT, bone and PET/CT scans, FNA and excisional biopsies, all of which did not reveal evidence of invasive breast cancer. Findings of GM with ultrasound and mammography have been well described. Although findings on mammography and ultrasonography are usually suggestive of benign breast disease, a malignancy can not be excluded in some cases.19 Although MRI can provide more sophisticated image evaluation,18 it is not always specific enough to rule out malignancy, either. There is also no case report in the literature evaluating the recurrent GM with a thorough metastatic workup to rule out inflammatory breast cancer.

There is no clear consensuses regarding optimal management of GM. Antibiotics, steroids and surgery are the options from least to most aggressive. Treatment should be directed according to the aetiology of the GM. Triple assessment, which consists of clinical assessment, histology including FNA and/or excisional biopsy and radiological evaluation, is very useful for the final diagnosis.24 In view of the inconclusive findings with clinical and radiological evaluation in some patients, pathological diagnosis should be made since it is the cornerstone of the evaluation. Antibiotics are widely used; however, there is no proven benefit in studies. In a study of 54 GM cases only 5% of patients showed improvement with empiric antibiotics. In the same study, the most effective non-invasive treatment was corticosteroids with 77% of patients showing improvement.25 Steroids are preferred by some for severe cases of GM25 and/or for recurrent disease after surgery.17 Nevertheless, a tissue culture and stain is always necessary to exclude an infectious process, to guide antibiotic treatment, and to be able to start steroid treatment. Surgical treatment options are limited excision or wide local excision. More aggressive surgery is not recommended in the literature given the fact that the disease process is mostly self-limited. In a study evaluating the conservative management of GM patients, 4 out of 8 patients had spontaneous resolution with no medications or surgical intervention.22 Al-Khaffaf et al24 evaluated 18 patients with GM and they grouped patients under treatment categories. They found that the overall outcomes were not related to any combination of treatment options. All of the patients involved in the study spontaneously resolved regardless of treatment. This data indicated that surveillance and reassurance would be the appropriate management for most patients with GM after triple assessment to preclude unnecessary surgeries, side effects of steroid treatment and to reduce patient anxiety. In our case, the frustration that the patient experienced in association with the prolonged disease course and multiple recurrences ultimately led to a bilateral mastectomy. It might not have happened if expectant management had been undertaken after triple assessment.

In conclusion, we reported an unusual presentation of GM which had subareolar involvement and an unusual progression after excisional biopsy and, possibly, after bilateral mastectomy. There was also a possible relationship with remote risperidone use and pregnancy. The recurrent lesion was very suspicious for IBC, although a final diagnosis of GM was made after clinical assessment, a complete malignancy workup and pathological diagnosis. Therefore, clinicians should be aware that subareolar erythema is an unusual, but possible, location for GM. Ruling out IBC should be an integral part of the workup of GM with triple assessment in a multidisciplinary approach. Eventually, expectant management with a conservative treatment approach may be more expedient to preclude unnecessary surgeries, side effect of steroids and to reduce patient anxiety. Management options and clinical outcomes should be shared with the patient to ease the patient's decision process and to prevent unfavorable outcomes. Expectant management should be considered in most patients.

Learning points.

-

▶

Granulomatous mastitis, also known as granulomatous lobular mastitis, is a rare chronic breast disease of unknown aetiology. Galactorrhea, inflammation, breast mass, tumorous indurations and ulcerations of the skin are the presenting symptoms. GM can be seen in every quadrant of the breast, including subareolar region.

-

▶

GM can show clinical/radiologic features mimicking inflammatory breast cancer, in either initial presentations or/and recurrent disease.

-

▶

Distinction of GM from inflammatory breast cancer is necessary. A multidisciplinary approach with triple assessment (including clinical, radiological and pathology) evaluation is the key for the correct diagnosis.

-

▶

Antibiotics, steroids, and surgery are the options from least to most aggressive depending on the severity of the lesion; however, conservative approach with watchful waiting has similar outcomes due to self-limiting nature of the problem.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Kessler E, Wolloch Y. Granulomatous mastitis: a lesion clinically simulating carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1972;58:642–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diesing D, Axt-Fliedner R, Hornung D, et al. Granulomatous mastitis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2004;269:233–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor GB, Paviour SD, Musaad S, et al. A clinicopathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynebacteria infection and granulomatous mastitis. Pathology 2003;35:109–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cserni G, Szajki K. Granulomatous Lobular Mastitis Following Drug-Induced Galactorrhea and Blunt Trauma. Breast J 1999;5:398–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown KL, Tang PH. Postlactational tumoral granulomatous mastitis: a localized immune phenomenon. Am J Surg 1979;138:326–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy MS. Granulomatous mastitis and lipogranuloma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol 1973;60:432–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Ongeval C, Schraepen T, Van Steen A, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur Radiol 1997;7:1010–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erhan Y, Veral A, Kara E, et al. A clinicopthologic study of a rare clinical entity mimicking breast carcinoma: idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Breast 2000;9:52–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han BK, Choe YH, Park JM, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: mammographic and sonographic appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;173:317–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinde SR, Chandawarkar RY, Deshmukh SP. Tuberculosis of the breast masquerading as carcinoma: a study of 100 patients. World J Surg 1995;19:379–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schelfout K, Tjalma WA, Cooremans ID, et al. Observations of an idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001;97:260–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baslaim MM, Khayat HA, Al-Amoudi SA. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a heterogeneous disease with variable clinical presentation. World J Surg 2007;31:1677–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tse GM, Poon CS, Ramachandram K, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: a clinicopathological review of 26 cases. Pathology 2004;36:254–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marriott DA, Russell J, Grebosky J, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis masquerading as a breast abscess and breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 2007;30:564–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez-Parra D, Nevado-Santos M, Meléndez-Guerrero B, et al. Utility of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of granulomatous lesions of the breast. Diagn Cytopathol 1997;17:108–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakurai T, Oura S, Tanino H, et al. A case of granulomatous mastitis mimicking breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer 2002;9:265–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mote DG, Gungi RP, Satyanarayana V, et al. Granulomatous mastitis, a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Surg 2008;70:241–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akcan A, Akyildiz H, Deneme MA, et al. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: a complex diagnostic and therapeutic problem. World J Surg 2006;30:1403–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heer R, Shrimankar J, Griffith CD. Granulomatous mastitis can mimic breast cancer on clinical, radiological or cytological examination: a cautionary tale. Breast 2003;12:283–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imoto S, Kitaya T, Kodama T, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1997;27:274–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JH, Oh KK, Kim EK, et al. Radiologic and clinical features of idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis mimicking advanced breast cancer. Yonsei Med J 2006;47:78–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai EC, Chan WC, Ma TK, et al. The role of conservative treatment in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Breast J 2005;11:454–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kok KY, Telisinghe PU. Granulomatous mastitis: presentation, treatment and outcome in 43 patients. Surgeon 2010;8:197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Khaffaf B, Knox F, Bundred NJ. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a 25-year experience. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:269–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hovanessian Larsen LJ, Peyvandi B, Klipfel N, et al. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:574–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]