Abstract

Nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) is a surveillance mechanism that degrades transcripts containing nonsense mutations, preventing the translation of truncated proteins. NMD also regulates the levels of many endogenous mRNAs. While the mechanism of NMD is gradually understood, its physiological role remains largely unknown. The core NMD genes upf1 and upf2 are essential in several organisms, which may reflect an important developmental role for NMD. Alternatively, the lethality of these mutants might arise from their function in NMD-independent processes. To analyze the developmental importance of NMD, we studied Drosophila mutants of the other core NMD gene, upf3. We compare the resulting upf3 phenotype with those defects observed in upf1 and upf2 loss-of-function mutants, as well as with flies expressing a mutant Upf2 protein unable to bind Upf3. Our results show that Upf3 is an NMD effector in the fly but, unlike Upf1 and Upf2, plays a peripheral role in the degradation of most NMD targets and is not required for development or viability. Furthermore, Upf1 and Upf2 loss-of-function inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis through a Upf3-independent pathway. Accordingly, disruption of Upf2–Upf1 interaction causes death, while the Upf2–Upf3 complex is dispensable for viability. Our findings suggest that NMD is essential for cell growth and animal development, and that the lethality of upf1 and upf2 mutants is not due to disrupting their roles during NMD-independent processes, but to their function in the degradation of specific mRNAs by the NMD pathway. Furthermore, our results show that Upf3 is not always essential in NMD.

Keywords: RNA degradation, RNA processing, RNA quality control, cell growth, development

INTRODUCTION

Gene expression is tightly regulated throughout development and many post-transcriptional processes act in concert to achieve such control. Among them, several RNA decay pathways are required for the control of both the quality of RNAs and their expression levels. Nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) is an evolutionarily conserved surveillance mechanism that degrades transcripts containing a premature termination codon (PTC), preventing the translation of potentially harmful truncated proteins (Chang et al. 2007). PTCs can arise via gene mutation, aberrant mRNA splicing, directed gene rearrangements, and misexpression of genes triggered via transposons and retroviruses (He et al. 1993; Mitrovich and Anderson 2000; Gudikote and Wilkinson 2002; Alonso 2005). In addition to its quality-control function, NMD also regulates the expression levels of mRNAs with upstream open reading frames (uORFs), alternatively spliced mRNAs, and messengers that carry a stop codon in which the ribosome usually shifts the reading frame (Neu-Yilik et al. 2004). Other features not as well understood (e.g., long 3′ UTRs) also trigger decay via the same molecular pathway (for review, see Nicholson et al. 2010). Genome-wide transcriptome-profiling analyses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Drosophila melanogaster Schneider cells, and human cultured cells have revealed that the expression levels of 3%–10% of all mRNAs are affected by NMD (for review, see Nicholson et al. 2010).

The biological importance of NMD is highlighted by the fact that a quarter of all mutations causing inherited disorders are PTCs predicted to trigger NMD (Culbertson 1999). In some instances, proteins encoded by nonsense mRNAs are functional, but they are not produced in sufficient amounts due to degradation via NMD. Diseases exacerbated by NMD action include aniridia, cystic fibrosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Hutchinson et al. 2003; Vincent et al. 2003; Hillman et al. 2004; Wilkinson 2005). For such cases, clinical strategies to reduce NMD activity and increase the frequency of read-through are under evaluation (Holbrook et al. 2004). In addition, inhibition of NMD leads to a significant reduction of tumor growth (Pastor et al. 2010). There are also cases in which NMD ameliorates the effects of PTC mutations. For example, patients with a PTC-containing β-globin allele that does not trigger NMD show ineffective erythropoesis, while those with an NMD-inducing PTC are phenotypically normal. Similar cases have been described for the reduction of dominant truncated forms of the tumor-suppressor proteins BRCA1 and WT1 (for review, see Holbrook et al. 2004). However, prior to the implementation of disease-modulating clinical approaches, it is important to fully understand the biological roles of the NMD factors in vivo, especially since some of the core components of the NMD machinery participate in cellular processes that are NMD independent. Here we use D. melanogaster to investigate both the contributions of various NMD factors to NMD and the role of this RNA surveillance mechanism in cell growth and animal viability.

The key effectors of NMD include the “up-frameshift suppressor” proteins 1–3 (Upf1–3), and the “suppressor with morphological effect on genitalia,” or Smg proteins 1 and 5–9 (for review, see Nicholson et al. 2010). The Upf proteins are conserved from yeast to human, whereas the Smgs have orthologs in multicellular organisms but not in yeast. As an exception, Smg7 is not conserved in Drosophila. Based on their conservation from yeast to humans, and the fact that their depletion disrupts NMD in all of the eukaryotes studied thus far, the Upf proteins are considered the core factors that elicit NMD in diverse species. Upf1 is an ATP-dependent helicase and RNA-dependent ATPase, whose activity in human cells is stimulated by the binding of Upf2 and Upf3 (Chamieh et al. 2008). The recruitment of Upf1 and the kinase Smg1 on the target mRNA is mediated via interactions with the translation release factors eRF1 and eRF2. Transcripts carrying PTCs are promptly degraded upon contact with molecular complexes that include Upf1, Upf2, and Upf3, but the detailed mechanisms of this process are not fully understood. Upf1 activity is regulated via cycles of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, which depend on the activity of Smg1 but also require the additional Smg proteins (Ohnishi et al. 2003; Rehwinkel et al. 2006; Isken et al. 2008; Yamashita et al. 2009). Degradation is finally achieved either by the activity of the endonuclease Smg6 and/or via Smg5/Smg7, which provide a link to general cellular mRNA decay enzymes (Gatfield and Izaurralde 2004; Huntzinger et al. 2008; Eberle et al. 2009).

The importance of NMD effectors in animal development varies across species (Vicente-Crespo and Palacios 2010). In S. cerevisiae, the loss of the Upf proteins has no obvious effect on growth (Leeds et al. 1991; Cui et al. 1995), while in Caenorhabditis elegans inactivation of any of the NMD factors leads to viable worms with mild morphological abnormalities in the tail and genitalia (Hodgkin et al. 1989). In contrast, the loss of NMD factors in zebrafish and mice has serious implications for growth, development, and viability. In the case of zebrafish, morpholino-mediated knockdown of upf1, upf2, smg5, and smg6 causes embryonic lethality, whereas double depletion of upf3a and upf3b, and depletion of smg1, had little to no effect on viability (Wittkopp et al. 2009). In mice, upf1 and upf2 knockouts cause early embryonic lethality, and upf1-null blastocysts are unable to generate stable embryonic stem cell lines (Medghalchi et al. 2001; Weischenfeldt et al. 2008). This is consistent with the fact that the reduction of upf1 in human tissue culture results in cell cycle arrest (Azzalin and Lingner 2006). The existence of two paralogs of Upf3 (a and b) in vertebrates has made the study of Upf3 knockout animals difficult, and as yet no phenotypic data of this sort exists for the murine system. In humans, mutations affecting Upf3b are linked to the development of mental retardation, suggesting that even if Upf3a and Upf3b have overlapping functions in mammalian development, the loss of one of these paralogs is enough to perturb human development in a specific manner (Tarpey et al. 2007).

C. elegans and zebrafish, the only two systems that have allowed the phenotypic analysis of the full complement of NMD factors, have so far provided conflicting conclusions regarding the physiological importance of NMD. Although C. elegans is an excellent model with which to study development, most NMD factor mutants (except for Smgl-1 and Smgl-2) (Longman et al. 2007) show no obvious defects in cellular metabolism, in stark contrast to the effects observed for mammals. The situation in zebrafish better recapitulates the phenotypes observed in mice when depleting NMD factors. However, experiments in the fish rely on gene knockdowns rather than knockouts, and therefore are susceptible to fluctuations in knockdown efficiency.

Drosophila is a powerful system with which to study the physiological role of NMD, as it combines many of the strengths of the other models. The cellular phenotype of NMD-deficient Drosophila S2 cells is similar to that observed in mice, suggesting that the maintenance of cellular viability by NMD is conserved in these organisms (Rehwinkel et al. 2005). Furthermore, as in the mouse system, Drosophila Upf1 and Upf2 are required for animal development and viability (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006). However, Drosophila only has one homolog of upf3, making the study of upf3 more straightforward (Gatfield et al. 2003). This, combined with the high level of understanding of how genes control developmental processes in the fruit fly and the unique genetic manipulation tools available in fruit fly research, make of Drosophila an excellent system with which to study the biological roles of NMD.

Experiments in flies and zebrafish both suggest that the loss of NMD in these organisms causes lethality. However, the main limitation of the data concerning the importance of NMD during development is the inability to unambiguously ascribe the phenotypes seen in these organisms to a loss of NMD, and not to the perturbation of other NMD-independent molecular processes performed by NMD factors. For example, human Upf1 and Upf2 have a number of NMD-independent functions, including roles in other RNA decay pathways, control of DNA stability, and the regulation of translation (Mendell et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2002; Keeling et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2005; Azzalin and Lingner 2006; Rodriguez-Gabriel et al. 2006; Azzalin et al. 2007; Ajamian et al. 2008). Together with Upf1 and Upf2, Upf3 is described as a core component of the NMD pathway (for review, see Stalder and Muhlemann 2008). Thus, to analyze the importance of NMD in development, we decided to study the developmental effects of eliminating upf3 function in Drosophila.

Here we show that upf3 null mutant flies are viable and fertile and show no severe defects in development. We also demonstrate that germ-line provision of Upf1 and Upf2, but not of Upf3, is essential for embryonic development and patterning of the follicular epithelium. Furthermore, while upf3 mutant cells grow similarly to control cells, upf1 and upf2 mutant clones are unable to grow, due to a combination of increased cell death and the arrest of cell division. Our experiments also demonstrate that Drosophila Upf3 is an NMD effector in vivo; but in contrast to the central NMD roles of Upf1 and Upf2, we see that Upf3 plays a peripheral role in the degradation of most NMD targets. Based on these results and the finding that the Upf2–Upf3 interaction is required for NMD, but not for viability, we conclude that NMD is essential for cell growth and animal development, and suggest that the lethality of Drosophila upf1 and upf2 mutants is a consequence of their function in the degradation of specific RNAs.

RESULTS

Drosophila Upf3 is an NMD effector in vivo, but is not essential for animal viability

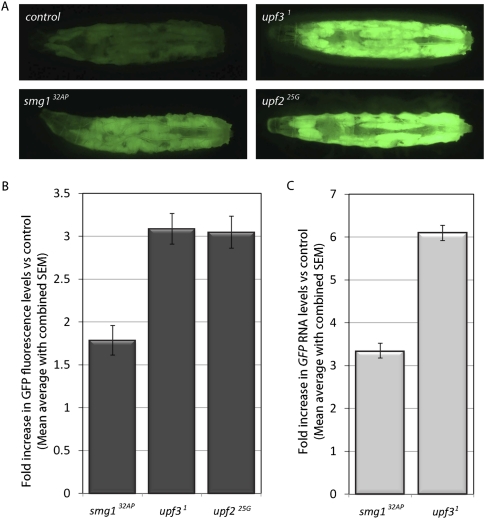

Drosophila upf3 is encoded by a single gene. Depletion of upf3 by RNAi in Drosophila cultured cells has shown that Upf3 is required for degradation of NMD targets (Gatfield et al. 2003; Rehwinkel et al. 2005). To study whether Drosophila Upf3 is an NMD effector not only in cultured cells, but also in the organism, we generated a upf3 null mutant (upf31; see Materials and Methods) and performed RT–PCR to detect the RNA levels of the NMD target mRNA for transformer (tra) in both wild-type and upf3 mutants. The levels of the PTC-containing isoform traL are higher in both upf31 and smg132AP mutants than in wild type, suggesting a role for Upf3 in NMD in the fly (Supplemental Fig. S1). Further confirmation of the role of Upf3 in NMD was obtained by analyzing the levels of expression of a GFP-based NMD reporter, GFP-SV40 3′UTR, in upf31 larvae. Previous work revealed that GFP RNA levels arising from a transgene containing 3′UTR sequences from the Simian Virus 40 (SV40) are enhanced in flies that are mutant for upf225G, a hypomorphic allele of Upf2 described as an NMD null mutant (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006). As shown in Figure 1, deletion of upf3 led to an up-regulation in GFP fluorescence levels similar to that seen in upf225G mutant larvae and greater than observed in smg132AP larvae (Fig. 1A). Image analysis illustrated that at the level of GFP fluorescence, upf31 and upf225G caused a 3.1- and 2.9-fold increase, respectively, whereas smg132AP caused only a modest 1.7-fold increase (Fig. 1B). The differences between GFP fluorescence in upf31 and smg132AP mutants mimicked the differences observed at the level of RNA, suggesting that all of the differences observed in GFP levels were most likely due to alterations in RNA stability (Fig. 1C). This result confirms Drosophila Upf3 as an NMD effector in vivo, and suggests that the requirements for NMD in the fly are similar for Upf2 and Upf3.

FIGURE 1.

A UAS-GFP-SV40-based reporter system shows that Upf3 is a NMD factor in the fly. (A) Dorsal view of control or mutant L3 larvae carrying the NMD reporter GFP-SV40 3′UTR transgene. A significant increase in fluorescence intensity is observed in smg1, upf2, and upf3 mutant larvae. (B) Quantification of GFP fluorescence intensity in smg1, upf2, and upf3 larvae. Graphs show fold increase with respect to control flies. (C) Quantification of GFP RNA levels in mutant pre-pupae by qPCR, expressed as fold increase compared with wild-type levels.

However, in marked contrast to the phenotype of strong mutant alleles for upf2 and upf1, upf31 flies are viable and fertile. This, in turn, implies that NMD might not be essential for animal viability (at least in invertebrates), and that the phenotypic lethality of the upf1 and upf2 strong alleles might be due to their activity in other developmentally essential processes, rather than because of a loss of NMD. This hypothesis is supported by the analysis of the upf225G allele. This allele appears completely compromised for NMD (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006), yet unlike upf2 null alleles, occasional upf225G mutant males survive to adulthood (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; this work). Alternatively, Upf1 and Upf2 might be essential genes due to their function in NMD. In this model, Upf1 and Upf2 would regulate developmentally essential transcripts via an NMD pathway that acts independently of Upf3. Such a pathway has been postulated to exist in human cells (Chan et al. 2007). We would also hypothesize that this pathway would be differentially affected in the hypomorph upf225G compared with the upf2 null alleles, since upf225G is a semiviable allele.

To address these questions, and to further elucidate the importance of individual factors within the process of NMD, we found that it was necessary to study the developmental and NMD phenotypes of the upf1 and upf2 strong alleles (upf126A, upf214J) and compare them with the upf225G, upf31, and smg132AP mutants.

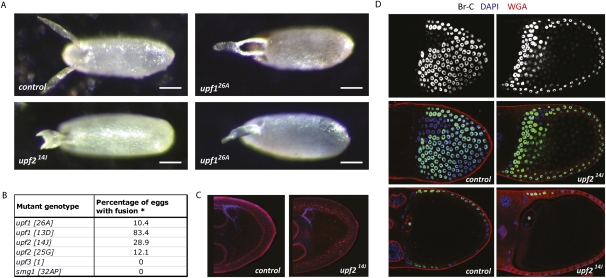

Germ-line provision of Upf1 and Upf2, but not of Upf3, is essential for embryogenesis and patterning of the follicular epithelium

To analyze the biological effects of mutating each one of the NMD factors, we collected embryos laid by mutant females (upf31 and smg132AP) as well as embryos emerging from germ-line clones (upf126A, upf214J). Phenotypic analysis of these eggs revealed that upf1 and upf2 eggs presented a dorsal appendage (DA) fusion phenotype with varying levels of phenotypic severity (Fig. 2A,B). Each of the upf1 and upf2 germ-line clones also led to the production of “normal” looking eggs, but close inspection suggested that subtle phenotypes could be observed. For example, upf126A eggs occasionally showed a “curled” phenotype, in which the ends of the DAs curled around to form a hook-like shape, while upf214J eggs exhibiting the weakest phenotype mostly had “fat-ends” (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Germ-line Upf1 and Upf2 are essential for embryonic development and patterning of the follicular epithelium. (A) Dorsal view of eggs obtained from upf1 and upf2 germ-line clones. Dorsal appendages appear partially (top, right) or totally (bottom) fused in upf1 and upf2 mutants. (B) Quantification of the percentage of eggs that show fused dorsal appendages in various mutants. (*) Dorsal appendages with abnormal morphologies (e.g., thick ends), but not fused, were excluded from this quantification. (C) The distribution of Gurken (blue) is similar in control and upf214J oocytes. Fluorescent wheat-germ agglutinin (WGA) is in red. (D) Expression of Broad Complex (Br-C, white and green at top and middle, respectively) in control (left) or upf214J mutant (right) stage 10B egg chambers. WGA is in red, DAPI is in blue. (Top) Broad Complex (Br-C) staining; (middle, bottom) WGA, Br-C, and DAPI staining merged; (bottom) section of the egg chamber showing the localization of the oocyte nucleus.

Importantly, none of the eggs produced from upf1 and upf2 germ-line clones hatched. These results show that lack of maternal upf1 or upf2 disrupts early development and causes lethality and raises the possibility that functional NMD is essential for embryogenesis. However, upf3 and smg1 mutant eggs had normal DAs and developed as wild-type eggs. This may suggest that the upf1 and upf2 phenotypes at embryogenesis are not related to NMD.

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of the DA phenotype observed in upf1 and upf2 mutant eggs, we analyzed the distribution and levels of the TGF-α-like protein Gurken in control and mutant oocytes (Fig. 2C). DA formation during Drosophila oogenesis is triggered by Gurken, which is secreted by the oocyte and activates the EGF receptor in the adjacent follicle cells to specify the two DAs and the dorsal-most cells separating them. Therefore, we hypothesized that disruption of Gurken signaling, subsequently leading to irregular follicle cell fate determination, might be a plausible cause for the DA fusion observed in upf1 and upf2 mutants. However, antibody staining for Gurken in upf126A and upf214J oocytes indicated that both the expression levels and cytoplasmic localization of Gurken were similar in control and mutant egg chambers.

To determine whether follicle cell fates are affected in upf1 and upf2 egg chambers, we looked directly at follicle cell patterning using Broad Complex (BR-C) expression as a cell fate marker. BR-C expression in dorsal follicle cells depends on EGF signaling and dictates DA fate (Deng and Bownes 1997). In wild-type ovaries, BR-C protein expression is uniform in all follicle cells at early stages of oogenesis (data not shown), but at stage 10b, BR-C becomes strongly reduced in a T-shaped group of cells at the dorsal anterior of the oocyte, directly above the oocyte nucleus (Fig. 2D, left). In upf214J egg chambers, Br-C is detected in the dorsal-most follicle cells, and the T-shaped pattern is lost (Fig. 2D, right). The expansion of BR-C protein expression in this mutant is consistent with the observed DA defects, and strongly suggests that Upf2 is required in the oocyte to regulate EGF signaling and patterning of the somatic epithelium.

Loss-of-function of Upf1 and Upf2 inhibits clone growth through a Upf3- independent pathway

The developmental defects observed in Drosophila (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; this work) and in other organisms (Medghalchi et al. 2001; Wittkopp et al. 2009) that lack functional Upf1 and Upf2 are not surprising, considering that the inhibition of NMD in cellular systems leads to cell cycle arrest. The role of Upf1 and Upf2 in cell proliferation does not seem to be restricted to cultured cells, since deletion of the N terminus of Upf2 inhibits cell division in mice hematopoietic lineages (Weischenfeldt et al. 2008), and upf1 and upf2 mutant cells in the Drosophila eye suffer a growth disadvantage when in competition with wild-type cells (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006).

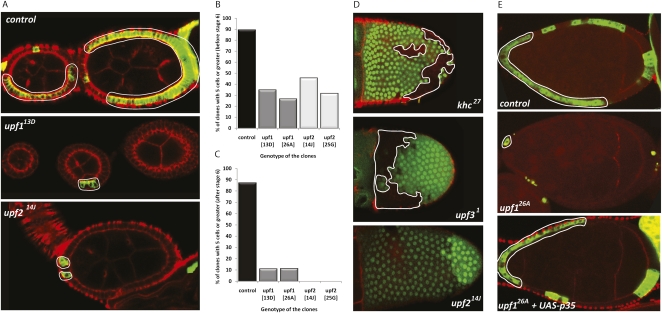

To further explore the cellular function of NMD factors in a developmentally relevant context, we generated upf1 and upf2 clones in the follicular epithelium of the egg chamber. Development of the follicle cells (FCs) is a two-staged process characterized by cell division during the early stages of oogenesis, followed by cell growth in the later stages (Supplemental Fig. S2). Mutant FC clones were induced for each of the upf1 and upf2 alleles using the MARCM system, and clone size (number of cells per clone) was recorded for early and late egg chambers (cell division and cell growth phases, respectively). As can be seen in Figure 3, all upf1 and upf2 FC clones were smaller than wild-type clones in early egg chambers, suggesting that cell division is severely impaired in mutant cells (Fig. 3A,B). Although rare, occasional early egg chambers were seen in which all FCs seemed to be mutant, suggesting that when there are no competing wild-type cells, mutant cells can divide to form a normal follicular epithelium (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Upf1 and 2, but not Upf3 are required for the growth of follicle cell clones. (A) Control or mutant follicle cell clones (outlined) were generated by the MARCM system (GFP marks the cells in the clone). (B,C) Quantification of the number of control and mutant clones with five or more cells in either (B) early, proliferating egg chambers, or (C) late, endocycling egg chambers. (D) Induction of GFP-clones that are mutant for the alleles khc27 (used as a control), upf31 or upf214J. GFP-clones are outlined. (E) Representative examples of the clone size achieved by control cells (top), upf226A cells (middle), and upf226A cells that also overexpress the Baculovirus apoptosis inhibitor p35 (bottom). F-actin is labeled by fluorescent phalloidin (red).

In a similar fashion to early oocytes, upf1 and upf2 clones were also smaller than control clones in late egg chambers (Fig. 3C). Applying the FRT/FLP technique to generate clones and using GFP absence to detect mutant cells, we found that in a few cases mutant clones could not be detected, although recombination had indeed taken place as inferred by the presence of a “twin” clone (Fig. 3D, bottom, cells with high GFP levels). While the small size of mutant clones could be explained by the low numbers of mutant cells generated during early oogenesis, late clones had even fewer cells than those seen in early egg chambers (Fig. 3, B vs. C), suggesting that a defect in cell viability is likely contributing to the small size of clones at late oogenesis. Adding weight to this argument, we observed that mutant FCs often appeared to have abnormal morphologies (Supplemental Fig. S3). In the strongest cases, a punctate GFP expression was observed, possibly indicating the formation of spherical cellular bodies. We hypothesized that these were dying cells, in which apoptosis had been triggered in response to growth complications caused by upf1/upf2 mutations (see below).

NMD factors essential for organismal viability, such as upf1 and upf2, are also essential for cellular viability. Given that upf3 mutants are viable, the cellular growth capacity of upf3 mutant cells is therefore of significant interest. As shown in Figure 3D, we frequently observed large clones of upf31 mutant FCs, and there was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of large clones between control and upf3 mutants. In addition, while upf1 and upf2 clones were rarely larger than five cells, upf3 clones were very large, matching the size of those observed in controls (data not shown). These data show that contrary to Upf1 and Upf2, Upf3 is not essential for cell growth.

Overexpression of the apoptosis inhibitor protein p35 partially rescues the upf126A cell growth phenotype

At mid-oogenesis, wild-type FCs are cuboidal in appearance (Supplemental Fig. S3). In contrast, GFP distribution in upf1 and upf2 mutant cells was often spherical, and occasionally punctated, possibly reflecting nuclear envelope breakdown (which allows GFP to enter the nucleus) and the formation of cellular bodies, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S3). We hypothesized that upf1 and upf2 mutant FCs might undergo programmed cell death, and that the inhibition of apoptosis in these cells might rescue this phenotype. To test this model we inhibited apoptosis in mutant cells by expressing the Baculovirus apoptosis inhibitor protein p35 in upf126A clones (Hay et al. 1994). Interestingly, the size of upf1 clones expressing p35 often reflected that of control clones (Fig. 3E), illustrating that expression of p35 rescued, at least partially, the cell growth phenotype caused by the loss of upf1 function. In addition, dying cells (assessed by morphological changes) were never seen in the p35-expressing upf126A clones. Our results show that although impairment of cell proliferation might still play a role in the process, cell death via apoptosis is a major factor contributing to the reduced size of upf1 and upf2 mutant clones in late egg chambers.

Upf3 has a peripheral role in the degradation of most NMD targets

One hypothesis to explain the upf1 and upf2 mutant phenotypes observed is that Upf1 and Upf2 might regulate the levels of transcripts that are crucial for cell growth and overall animal viability. This model would predict that the stability of such target mRNAs is not affected by the function of Upf3 or Smg1, since cell growth and development are normal in upf3 and smg1 mutant animals. The results obtained with the NMD reporter GFP-SV40-3′ UTR in the upf225G and upf31 alleles suggested that the requirements for NMD in the fly are similar for Upf2 and Upf3 (Fig. 1). However, it should be noted that the mechanism by which the SV40 terminator stimulates NMD is unknown, and may not be indicative of how NMD acts during the regulation of endogenous targets. To study whether Upf1 and Upf2 regulate developmentally essential transcripts via an NMD pathway that acts independently of Upf3, we studied the effects of NMD factor mutation on endogenous target levels.

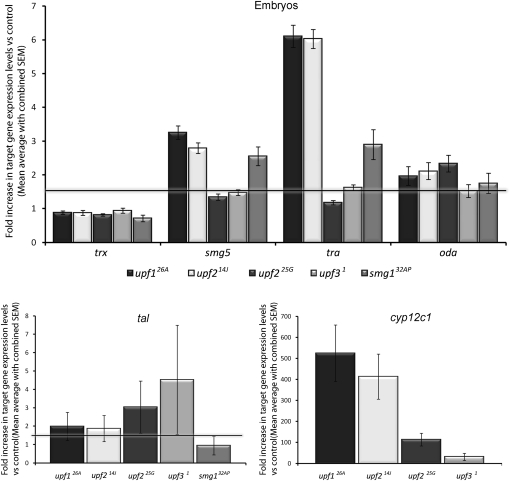

To analyze the expression levels of NMD targets in the strongest NMD factor alleles, mutant eggs obtained from homozygous females (for upf31 and smg132AP), or from germ-line clones (for upf126A, upf214J, and upf225G) were collected to be used for qPCR (see Materials and Methods). Eggs between 0 and 2 h of development were used, as zygotic gene expression does not begin until after this time window, ensuring that eggs produced from germ-line clones were free of complementary wild-type NMD factors.

We selected a battery of targets including (1) PTC-containing NMD targets such us ornithine decarboxylase antizyme (oda, also known as gutfeeling) and transformer (tra); (2) genes showing significant up-regulation in microarray studies of NMD-depleted S2 cells (Rehwinkel et al. 2005) and upf225G larvae (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006), which included trithorax (trx) and cytochrome P450 (cyp12c1), neither of which produces transcripts with a described PTC; and (3) smg5, a component of the NMD machinery and an NMD target in Drosophila and human cells (Rehwinkel et al. 2005; Chan et al. 2007).

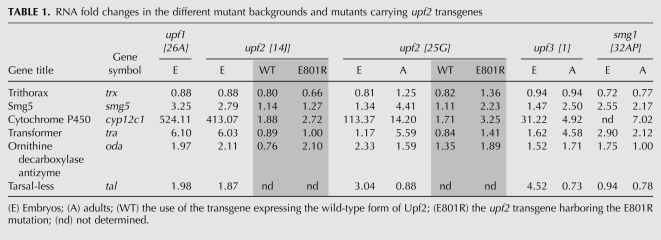

As shown in Figure 4 and Table 1, trx levels were not increased in any of the mutant embryos. In contrast to this, smg5 is increased similarly in upf126A (3.3-fold) and upf214J (2.8-fold), but is affected much less in upf31 mutants (1.5-fold). A related pattern was seen for the expression of the PTC targets tra and oda, upon which upf31 only exerted a small effect compared with the larger effects observed in upf126A and upf214J contexts.

FIGURE 4.

Target gene expression in NMD mutant embryos. Fold change in RNA levels of trithorax (trx), smg5, transformer (tra), ornithine decarboxylase antizyme (oda), tarsalless (tal), and cytochrome P450 (cyp12c1) as detected by qPCR in the different mutant backgrounds (normalized against Rp41 expression and reported as fold change vs. control). The horizontal line represents the 1.5-fold needed to denote a meaningful result.

TABLE 1.

RNA fold changes in the different mutant backgrounds and mutants carrying upf2 transgenes

Quantification of cyp12c1 mRNA levels in mutant embryos revealed a striking behavior: While cyp12c1 expression in wild-type embryos was very low and difficult to detect, cyp12c1 expression was increased over 30-fold in upf31 embryos. Even more strikingly, upf214J and upf126A mutants exhibited a several hundred-fold increase in cyp12c1 levels (Fig. 4; Table 1). These effects were never observed in control flies under identical heat-shock treatment (data not shown). These results suggest that NMD is responsible for maintaining cyp12c1 levels at near zero during embryogenesis, and that a removal of the core NMD factors at this stage releases this repression. The data also indicate that Upf3 plays a small but significant role in the degradation of cyp12c1 mRNA in embryos, whereas Upf1 and Upf2 play a much larger role and are the key mediators of this degradation.

Thus, Upf3 seems to have a peripheral role in the degradation of cyp12c1, smg5, tra, and oda mRNAs during embryogenesis. In contrast, Upf1 and Upf2 play a major role in the degradation of all targets analyzed, except for trx, which was insensitive to all mutations. It is interesting to note that the effects of upf126A and upf214J were identical for all of the targets studied. However, upf225G, which was previously described as a NMD null allele of upf2, has weaker effects on NMD targets than upf214J in embryos (Fig. 4; Table 1).

The last gene analyzed, tarsalless (tal), contains four small uORFs (Galindo et al. 2007). mRNAs with uORFs have been suggested to be NMD targets, a hypothesis recently confirmed in C. elegans (Ramani et al. 2009). We show here that transcripts with uORFs are also NMD targets in Drosophila, since tal was up-regulated in all upf1, upf2, and upf3 mutant embryos (Fig. 4; Table 1). The large error associated with tal expression suggests that the levels of this transcript vary greatly in the mutants, perhaps because it is being transiently degraded during only a small time window within the first 2 h of embryogenesis.

These results combined indicate that there is a correlation between NMD target levels and lethality phenotype in the mutant alleles of upf1, upf2, and upf3, suggesting that the differential effect on targets could explain why upf1 and upf2, but not upf3, are essential genes.

Not all of the NMD targets identified in cultured cells are necessarily similarly regulated by NMD in the organism

Our experiments show that the transcript trx—one of the most up-regulated genes in cell-based microarray studies—is not an NMD target in embryos, pre-pupae, or adults (Figs. 4, 5; Table 1; Supplemental Fig. S4). This finding prompted us to investigate whether other NMD targets identified in Drosophila cultured cells are legitimate target genes in the animal. For this we selected a subset of genes up-regulated in Drosophila S2 cells based on two main criteria: (1) significant increase in target gene expression level in cultured cells irrespective of which NMD factor had been knocked down; and (2) genes with a well-understood biological function during Drosophila development (Rehwinkel et al. 2005). The chosen targets were ago2, fat2, mgat1, and asx. Of these, none were significantly up-regulated in NMD mutant pre-pupae, except for a mild increase in levels seen in the case of ago2 (Table 1; Supplemental Fig. S4): upf31 allele caused a 1.6-fold increase in ago2 levels compared with control. However, the fact that ago2 levels are not significantly up-regulated in upf225G and smg132AP mutants suggested that this effect is limited to upf3 mutants and is mild at best, a finding in marked contrast to what has been observed in cells.

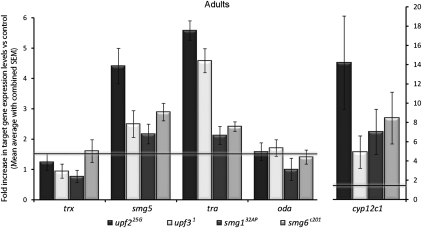

FIGURE 5.

Target gene expression in NMD mutant adults. Fold change in RNA levels of trithorax (trx), smg5, transformer (tra), ornithine decarboxylase antizyme (oda), and cytochrome P450 (cyp12c1) as detected by qPCR in the different mutant backgrounds (normalized against Rp41 expression and reported as fold change vs. control). The horizontal line represents the 1.5-fold needed to denote a meaningful result.

These findings suggest that not all of the NMD targets identified in cultured cells are necessarily similarly regulated by NMD in the organism. It is possible that the process or its targets are differentially regulated during development. For example, the cell culture system might represent a situation confined to certain developmental stages, or to certain gene isoforms. It is also plausible that indirect targets are differentially affected in cultured cells and in the animal by a protein encoded by the direct RNA target (e.g., a transcription or a splicing factor).

A mutant form of Upf2 unable to bind to Upf3 rescues NMD and lethality of upf2 alleles

Our analysis in embryos suggested that Upf3 plays a peripheral role in the degradation of most NMD targets, a hypothesis further supported by work in S2 cells (see Discussion) (Rehwinkel et al. 2005). This finding raises the possibility that the lethality observed in upf1 and upf2 mutants is due to the stabilization of specific NMD targets in these mutants, transcripts that would not be strongly affected in flies lacking upf3. Alternatively, the lethality of upf1 and upf2 strong alleles might be at least partially due to their activity in other developmentally essential processes unrelated to NMD.

To distinguish between these two hypotheses, we studied the significance of the physical interactions between Upf2–Upf3 and Upf2–Upf1 for NMD performance, cell growth, and animal viability. For this we produced transgenic flies expressing mutated versions of Drosophila Upf2 including changes in glutamic acid 801 (E801R) and in amino acids 1143-4 (FVRR). In human Upf2, the equivalent glutamic acid at position 858 is essential for the formation of the Upf2–Upf3 complex, and mutating it to arginine abolished completely the binding of Upf2 to Upf3, without affecting the interaction of Upf2 with Upf1 or Smg1 (Kadlec et al. 2004; Kashima et al. 2006). The amino acids FV are also conserved in humans and the alteration of the equivalent sequence (FVM1173ERE) completely abolishes the interaction of Upf1 and Upf2, as seen by structural and mutational analysis (Clerici et al. 2009). Similarly, the mutations E801R and 1143-4(FVRR) abolish the binding of Drosophila Upf2 to Drosophila Upf3 and Upf1, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S5). We then tested the capacity of these mutant forms of Upf2 to rescue NMD and the lethality phenotype of upf2 mutants.

We first measured the levels of the previously described NMD targets in wild-type, smg132AP, upf31, and upf225G adults (as all other mutant alleles are lethal at this developmental stage) (Fig. 5). The PTC-containing gene oda is up-regulated only a small amount in upf225G and upf31 mutant adults, but is not up-regulated at all in smg132AP mutants. tra (which also contains a PTC) was affected in a similar fashion, with levels only moderately increased in smg132AP mutants and increased considerably in upf225G and upf31 mutants. In the case of smg5 and cyp12c1, upf225G mutant adults showed a higher up-regulation than upf31 and smg132AP mutant adults, with these two alleles showing similar levels for both RNAs.

We then assessed the capacity of the two Upf2 mutant forms to rescue the lethality in upf2 mutants by expressing the Upf2(E801R) or Upf2(FVRR) transgenes in upf225G or upf214J flies (see Materials and Methods). The hypomorphic allele upf225G produces occasional escaper adults, while upf214J causes complete lethality, as mutant adults are never seen in this allele. These semi-lethal and lethal phenotypes did not seem to be rescued when expressing Upf2(FVRR) in flies mutant for the two upf2 alleles, since we never observed adults in the case of upf214J (0/40), and only a few escapers in the case of upf225G (2/29). Contrary to Upf2(FVRR), Upf2(E801R) rescued the lethal phenotype for both alleles, since we often obtained upf214J and upf225G mutant adults expressing Upf2(E801R) (7/42 and 12/33, respectively). The Upf2 expression levels of the Upf2(E801R) and Upf2(FVRR) transgenes (assessed by qPCR) were very similar (data not shown).

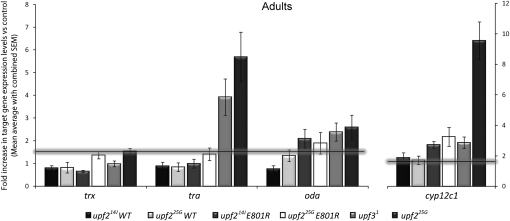

These results show that the interaction of Upf2 with Upf3 is not essential for animal viability, whereas the binding of Upf2 to Upf1 is. This result suggests that the upf1 and upf2 lethality phenotype is probably due to a function of these proteins that requires the formation of the Upf1–Upf2 complex, as is the case for NMD. If this hypothesis is correct, the interaction of Upf2 and Upf3 would not be essential for NMD, and the levels of NMD targets in upf2 mutants flies expressing the Upf2(E801R) transgene should be similar to upf3 mutant flies. To analyze the function of Upf2(E801R) in NMD, we studied the levels of the NMD targets oda, cyp12c1, tra, and smg5 in upf225G and upf214J adult flies that expressed Upf2(E801R) or a wild-type (WT) version of Upf2 (Fig. 6; data not shown). We found that for all RNAs, except for tra, the expression of Upf2(E801R) in upf2 mutant flies rescued NMD to levels similar to upf3 mutants. These levels are always lower than in upf225G mutants and higher than in upf2 mutants that also express the Upf2(WT) transgene. The Upf2 expression levels of the Upf2(E801R) and Upf2(WT) transgenes (assessed by qPCR) were very similar (Supplemental Fig. S6). Furthermore, Upf2(E801R) was not only able to rescue the animal lethality phenotype of upf214J, but also the cell growth defects observed in this mutant allele (Supplemental Fig. S7). We thus conclude that a mutant form of Upf2 unable to interact with Upf3 partially rescues the expression levels of NMD target genes in upf2 mutants and is also capable of rescuing cell and animal lethality in these organisms.

FIGURE 6.

Target gene expression in upf2 and upf3 flies, as well as in upf2 mutants that express various upf2 transgenes. Fold change in RNA levels of trithorax (trx), transformer (tra), ornithine decarboxylase antizyme (oda), and cytochrome P450 (cyp12c1) as detected by qPCR in upf2 and upf3 mutants, and in upf2 mutants expressing a wild-type Upf2 (WT) or a version unable to bind Upf3 (E801R) (normalized against Rp41 expression and reported as fold change vs. control). The horizontal line represents the 1.5-fold needed to denote a meaningful result.

DISCUSSION

NMD is a surveillance mechanism that establishes a quality checkpoint during gene expression and eliminates mRNAs harboring PTCs. Mutations introducing PTCs have been attributed to causing or exacerbating many human diseases, including Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and cancer, which stresses the importance of animal studies in the pursuit of potential therapies. In addition to the elimination of potentially harmful RNAs, NMD also regulates a broad range of endogenous transcripts. In combination, these findings highlight the importance of analyzing the impact of NMD for the regulation of proper development as well as the possible consequences of modifying its efficiency. To this end, we have employed the use of Drosophila melanogaster in order to take advantage of the versatile genetic manipulations afforded by this system. Altogether, our data significantly advances the current understanding of Drosophila NMD factor function and indicates that the role of NMD effectors during Drosophila development is very similar to that described so far in mammals and other vertebrates (further discussed below). Based on our findings, we would like to suggest that NMD is essential for cell growth and animal viability, that Upf1 and Upf2 are essential genes due to their central function in NMD, and that upf3 mutants are viable due to the peripheral role played by Upf3 in the degradation of many target transcripts.

Function of Drosophila Upf3 in NMD and development

Flies that are mutant for the NMD core components upf1 and upf2 die before reaching adulthood, but the loss of function of smg1 function does not generate obvious developmental defects (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; our work). Since Smg1 seems to only play a peripheral role in NMD in the fly (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; our work), it is plausible that upf1 and upf2 are essential genes due to the central role of these factors in NMD. On the other hand, it is important to note that neither in mice, zebrafish, nor Drosophila has it been established that the lethality associated with upf1 and upf2 mutations is due to their role as NMD effectors. In fact, the analysis of the allele upf225G suggested the opposite, since the allele appeared completely compromised for NMD, but produced viable adults (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006).

To analyze whether NMD is essential for development, we generated a complete loss-of-function allele of the other core component of NMD, upf3. We find that unlike the other core NMD factors, Upf1 and Upf2, Upf3 is not an essential gene in Drosophila. The upf31 allele is caused by a deletion that removes over 90% of the upf3 ORF, and the mRNA for upf3 was undetectable in these mutants by RT–qPCR, suggesting that this allele is a null mutation (data not shown). Mutants for upf1 and upf2 die during larval development, whereas a loss of upf3 causes only mild phenotypic effects, the most severe of which is a delay in the speed of development. These results indicate that at the developmental level, upf3 mutants share a similar phenotype with smg1 mutants and not with upf1 and upf2 mutants. Surprisingly, this similarity between Smg1 and Upf3 also seems to apply to NMD targets. The results from our studies on RNA levels by qPCR are consistent with a model in which the phenotypic differences observed in the various upf mutants are indicative of the relative importance of each factor for NMD, with Upf1 and Upf2 contributing the most and Upf3 playing a more ancillary role in the process in vivo, as has been suggested for Smg1 (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006). In agreement with this, recent work in zebrafish has shown that Upf1 and Upf2 are required for embryonic viability, whereas Upf3 and Smg1 are not (Wittkopp et al. 2009). Furthermore, Upf3b-independent branches of the NMD pathway have been suggested to exist in human cells (Gehring et al. 2005; Chan et al. 2007).

Our characterization of several RNA targets in the fruit fly confirms that the central role for Drosophila Upf3 in NMD should be revisited. The complex gene tarsalless, transcribed as a unique mRNA containing five ORFs, is the only endogenous target stabilized in upf3 mutant embryos to the same extent as in upf1 and upf2 mutants. In other PTC-containing RNAs, such as oda and tra, and in other NMD targets with uncharacterized PTC such as smg5 and cyp12c1, the defects found in upf3 mutants were much smaller than in upf1 and upf2. Although these are a reduced number of targets, our findings are supported by the fact that Upf3 regulates the expression of significantly less transcripts than Upf1 and Upf2 in Drosophila S2 cells (Rehwinkel et al. 2005). Furthermore, all NMD targets validated by Northern blot analysis in this S2 cells study were not as strongly up-regulated after depletion of Upf3 than after depletion of Upf1 or Upf2 (Rehwinkel et al. 2005). An unbiased genomic analysis in embryos mutant for loss-of-function alleles of all NMD factors would help to fully elucidate whether most NMD targets are weakly affected by Upf3, or whether Upf3 behaves as a core component for some targets. In any case, there seems to be a conserved NMD pathway in flies, fish, and mammals, in which Upf3 seems to have less of a central role than Upf1 and Upf2.

Roles of Upf1 and Upf2 in Drosophila development

Although upf1 and upf2 mutants die before they reach pupae state (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; this work), we have found that the relatively late effects of upf1 and upf2 mutations are explained by maternal contribution, which can mask phenotypes as late as the third larval stage of development in Drosophila. The effects of maternal deposition can be subverted via the generation of homozygous mutant germ line in an otherwise heterozygous female. When eggs produced from upf1 and upf2 mutant germ-line clones are fertilized with wild-type male sperm, the resulting embryos fail to develop and hatch, suggesting that the true phenotype of upf1 and upf2 mutant flies is lethality considerably earlier than during larval development. The fact that upf1 and upf2 mutant eggs are laid indicates that oogenesis is not completely arrested. However, it should be noted that the number of eggs laid by females with mutant germ-line clones is lower than by control females, and that in the most severe cases clonal females laid very few eggs, suggesting that the loss of function of upf1 and upf2 disrupts oogenesis to some extent.

All of the lethal alleles of upf1 and upf2 produced eggs exhibiting varying degrees of dorsal appendage abnormality. In the weakest cases this constituted hooking or thickening of dorsal appendage ends in a way not observed in wild-type eggs. At their most severe, these mutations led to dorsal appendage thickening, fusion, and shortening, often producing eggs with fully fused appendages. The penetrance of the fully fused dorsal appendage phenotype varied in a reproducible manner between the mutants, ranging from 10% in upf126A and 30% in upf214J to 80% in upf113D (dorsal appendages with abnormal morphologies, but not fused were excluded from this quantification). It is plausible that the protein produced by upf126A still has some function, as this mRNA produces a truncated form of Upf1 that includes a domain likely to be important for its interaction with Upf2, suggesting that it may still have residual NMD activity (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006). The upf113D allele is characterized by a point mutation in this domain, which alters a conserved cysteine residue that is essential for the Upf1–Upf2 interaction in yeast, producing a Upf1 protein unable to participate in NMD (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006). Thus, there is a correlation between the strength of the dorsal appendage phenotype and the effect of the mutant allele on NMD.

Dorsal appendage defects are not observed in upf3 or smg1 mutants, suggesting that this phenotype could be due to the regulation of targets strongly affected by Upf1 and Upf2 in the oocyte, but weakly affected by Upf3 and Smg1. How the regulation of these putative transcripts might influence the EGF-dependent patterning of the follicular epithelium and dorsal appendage formation is currently unknown, since the levels or localization of Gurken protein seems unaffected in upf1 and upf2 mutant oocytes. We would like to suggest a role for Upf1 and Upf2 in the oocyte in producing a fully functional Gurken protein, maybe by regulating a transcript involved in the post-translational modification and/or secretion of Gurken. However, more work is needed to elucidate the precise role of Upf1 and Upf2 in the activation of the EGF pathway, patterning of the epithelium, and formation of the dorsal appendages.

Function of Upf1 and Upf2 in cell growth

D. melanogaster Schneider cells depleted of Upf1 and Upf2 are arrested at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Rehwinkel et al. 2005), and in cultured human cells depletion of Upf1 also inhibits cell cycle progression (Azzalin and Lingner 2006). In mice, hematopoietic-specific production of a truncated Upf2 led to the extinction of all hematopoietic progenitor (but not differentiated) cells, suggesting that NMD is mainly essential for proliferating cells (Weischenfeldt et al. 2008). In the fly, upf1 and upf2, but not upf3 mutant cells generate very small clones in the follicular epithelium. Follicle cells are actively dividing in early egg chambers, but division stops after stage 6 of oogenesis. Mutant clones were much smaller than those generated by control cells in early egg chambers, indicating that Upf1 and Upf2 are required for cell proliferation, a finding consistent with the observations in mammals and cultured cells. In addition, the fact that upf1 and upf2 mutant clones in late stages were even smaller than mutant clones in early stages suggested an important role for Upf1 and Upf2 in cell survival. We confirmed this hypothesis by partially rescuing upf1 and upf2 mutant clone size with the overexpression of the Baculovirus apoptosis inhibitor p35. This result shows for the first time that the lack of Upf1 and Upf2 function does not only block cell proliferation, but also leads to cell death by apoptosis. In agreement with these results, the depletion of Upf1 and Upf2 induces neuronal cell death in zebrafish, and mouse Upf2 is required for the survival of proliferating cells (Weischenfeldt et al. 2008; Wittkopp et al. 2009).

NMD has been shown to play a role in carcinogenesis (Pastor et al. 2010, and references therein). PTCs in several tumor suppressor genes (e.g., BRAC1 and WT1) have been reported to result in reduced abundance of their mRNAs, and a strategy known as “gene identification by NMD inhibition” has identified tumor suppressor genes. Tumor suppressor proteins have a repressive effect on the cell cycle and/or promote apoptosis. Therefore, it is possible that the regulation of the same transcript(s) is responsible for the inhibition of cell division and induction of apoptosis that we observe in upf1 and upf2 mutant clones: inhibition of NMD in the mutant cells would result in the higher expression of a tumor-suppressor gene, and, consequently, a reduction in cell division and an enhancement in apoptosis. For example, one mutant p53 transcript found in breast cancer shows increased mRNA stability with the inhibition of NMD, and the truncated p53 is more stable than the wild-type protein (Anczukow et al. 2008). These interesting correlations may warrant further attention in the future and imply that Drosophila is a good model with which to study the therapeutic advantages of manipulating the activity of NMD in overproliferating cells.

Function of NMD in development

From the results we have presented so far, together with the work of other groups (Medghalchi et al. 2001; Rehwinkel et al. 2005; Azzalin and Lingner 2006; Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; Weischenfeldt et al. 2008; Wittkopp et al. 2009), we can conclude that upf1 and upf2 are essential genes for animal and cellular viability in most organisms. The severity of the phenotypes resulting from the loss-of-function of NMD factors correlates with the overall complexity of the organism, which suggests that NMD factors may have gained additional functions over evolutionary time. These functions could be simply a diversification of targets but may also be independent of their role in NMD. One possible explanation is that the accumulation of aberrantly spliced mRNAs and the resulting production of detrimental C-terminally truncated proteins may be the cause of the observed phenotypes. On the other hand, it may be possible that NMD regulates the expression of an essential protein in mice and flies, but not in yeast and worms.

Drosophila upf3 and smg1 are not essential genes, and upf3 and smg1 mutant flies develop as wild-type flies. These genes are also not required for cell proliferation and viability (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; this work). These findings might suggest that the upf1 and upf2 mutant phenotypes seen in most organisms might be due to the perturbation of NMD-independent functions of Upf1 and Upf2. Contrary to this argument, we have shown that the previously described peripheral role of Smg1 in regulating tra mRNA (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006) seems to be a general rule in the fly. We have also shown that Drosophila Upf3 plays a peripheral role in the degradation of various targets, which is further supported by results in S2 cells (Rehwinkel et al. 2005). Thus, the lethal phenotype in upf1 and upf2 mutants could be due to the regulation of targets that are not as sensitive to the loss of upf3 and smg1 than to the loss of upf1 and upf2. In addition, we have shown that the partially viable upf2 allele, upf225G, is not fully compromised for NMD when compared with stronger alleles of upf2 or upf1 mutants, further supporting a correlation between NMD target levels and the strength of lethality phenotype in the various mutant alleles of upf1, upf2, and upf3, and suggesting that the differential effect on targets could explain why upf1 and upf2, but not upf3, are essential genes.

The strongest argument supporting the relevance of NMD in development comes from the rescue experiments using mutated Upf2 transgenes. When we expressed a mutant version of Upf2 unable to interact with Upf3 in flies carrying the lethal upf214J allele, both the animal/cell lethality and the NMD defects were rescued. Only mild NMD defects in the levels of NMD target genes similar to those found in upf3 mutant flies were detected. On the other hand, a mutant version of Upf2 unable to interact with Upf1, and therefore completely compromised for NMD, did not rescue the lethal phenotype of the upf214J mutant allele. Thus, the essential function of Upf1 and Upf2 requires the formation of the Upf1–Upf2 complex. As far as is currently understood, NMD is the only function of either Upf1 or Upf2 that depends on the interaction of these proteins. In conclusion, these arguments suggest that a functional NMD pathway is essential for cell growth and animal development.

Our data suggest that the differential nature of the targets, or the differential effect of the NMD effectors on the targets, might explain why upf1 and upf2 are essential genes in some organisms, but not in others. This differential requirement in NMD across species seems to also apply to the regulation of Upf1 activity. Upf1 phosphorylation by Smg1 is thought to be essential for pathway activity in C. elegans and mammals. In flies, Smg1 is not an essential gene and seems to play a peripheral role in the degradation of all NMD targets analyzed (Rehwinkel et al. 2005; Metzstein and Krasnow 2006; this work). The viable smg132AP mutant allele used in the fly truncates the Smg1 protein before most of the conserved domains, including the kinase domain, and smg132AP over deficiency shows the same GFP-SV40 enhancement as smg132AP mutants, implying that smg132AP is an amorphic (null) allele (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006). In combination, these results suggest both that the phosphorylation of Upf1 by Smg1 is not absolutely required for NMD in the fly and that it is possible that the Drosophila genome encodes another kinase capable of regulating Upf1 activity via phosphorylation. Similarly, zebrafish development is severely affected in Upf2- and Upf1-depleted embryos, whereas no phenotype was observed in embryos depleted of Smg1 (Wittkopp et al. 2009).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks

BM followed by a number indicates the Bloomington Stock number. The fly stocks used in this work are as follows: y w; P{w+mC y+mDint2 = EPgy2}upf3EY03241 (BM 16558), w; e dys3/TM3, P{w+mC = GAL4-Kr.C}DC2, P{w+mC = UAS-GFP.S65T}DC10, Sb (BM 9591). w;; ry Dr1 P{ry+t7.2 = Delta2-3}99B/TM6 (BM 3612). w; P{w+mC = UAS-p35.H}BH1 (BM 5072), UAS-p35 and w; ; P{w+mC = UAS-p35.H}BH2 (BM 5073). y w FRT19A upf113D/FM7c, y w FRT19A upf126A/FM7i Act-GFP, y w FRT19A upf225G/FM7i Act-GFP, y w smg132AP/FM7c and y w FRT19A upf214J/FM7i Act-GFP from Metzstein and Krasnow (2006). w; upf31/SM6a, y w FRT101 upf113D/FM7i Act-GFP, y w FRT101 upf126A/FM7i Act-GFP, y w FRT101 upf214J/FM7i Act-GFP. P{ry+] neoFRT19A}19A, P{w[+ tubP-GAL80} L1, P{ry[+ hsFLP}1, w; P{w[+ UAS-nucZ}20b, P{w[UAS-CD8:GFP} LL5 ; TM6, Tb, Hu/P{w[+ tubP-GAL4} LL7 (from Alex Gould). y w P{ry+;hs:FLP122}; FRTG13-nlsGFP/CyO, w; FRTG13 khc27/CyO, y, w; PBacsmg6c201 (BM 16301).

Assessment of the viability of upf1 and upf2 mutants

It was previously reported that mutations in upf1 and upf2 cause lethality during larval development (Metzstein and Krasnow 2006). We have observed that upf126A larvae die at an early stage of development, developing to the L2 stage, but with a size comparable to L1 (data not shown). The upf214J null mutation causes lethality at a later stage of larval development (L3). Wild-type larvae pupate after 5 d of larval development, whereas upf214J L3 can live for up to 13 d before dying. Occasionally, these larvae attempt to pupate (∼10%), but normal head inversion fails to occur. In addition, upf214J larvae that are close to death often exhibit small, black areas of tissue, possibly indicative of necrotic lesions (data not shown). These lesions are also observed in upf225G hypomorphic L3 larvae and pupal cases. In the case of upf225G hypomorphs, these mutants often successfully manage to pupate, but most adults die before full eclosion. The source of weakness in these adults is unknown, but superficially they appear to have normal adult body morphology, suggesting that metamorphosis is not affected.

Creation of upf31 mutant allele

We generated upf3 mutants via imprecise excision of the P{Epgy2}EY03241 element, which is inserted in the first intron of the upf3 ORF. Screening by PCR revealed that one new upf3 allele was produced (upf31), characterized by a deletion that removes 1675 bp (92.5%) of the upf3 coding region including the start codon, as well as DNA sequence upstream of upf3 in which one would expect to find areas responsible for transcriptional regulation (Supplemental Fig. S1A). This allele was used for all upf3 functional analysis. Although this deletion also removes sequences of the gene CG17658, we do not believe this to be responsible for any observed phenotypes in upf31 animals, since CG17658 codes for a protein with no domains related to RNA metabolism and is only conserved among drosophilids (http://flybase.org/). Given the strong evolutionary conservation of the NMD factors, we are convinced that the defects observed in upf31 animals are due to the lack of a functional Upf3.

Assessment of NMD activity using a GFP-SV40-based reporter system

NMD mutant L3 larvae expressing the NMD target transcript encoded by the UAS-GFP-SV40 transgene were collected and pictures taken using a Leica DFC500 camera mounted on a Leica MZFLIII fluorescence stereomicroscope. These images were analyzed using Image J (Moodley and Murrell 2004; Sheffield 2007) and the average fluorescence intensity of a 100 × 100 pixel square area of the central fat body of each larva measured and recorded. In addition, mutant pre-pupae expressing UAS-GFP-SV40 were collected and RNA extracted for qPCR as described below. In the case of upf225G, these larvae died before they could pupate, and, subsequently, were not included in the RNA analysis.

Induction and analysis of germ-line and follicle cell clones

Germ-line clones were generated by the FLP/FRT recombinase system (Chou et al. 1993; Chou and Perrimon 1996) using the ovoD1 system, in which only homozygous mutant oocytes develop further than stage 4 of oogenesis. In order to induce recombination, second-third instar larvae were heat-shocked at 37°C for 2 h on three consecutive days. Females were either fattened for 20 h on yeast and dissected to harvest the ovaries, or mated with wild-type males to lay fertilized eggs. The ovaries were stained as described below. The mutant eggs were collected over a 2-h time period (representing a population of 0–2-h embryos) and their collective RNA extracted for use in qPCR experiments. Follicle cell clones were induced using the MARCM system (Lee and Luo 2001), or the FLP system with the lack of GFP as a marker for clones. The protocol for heat-shocking, fattening, and ovary collection was as described above. Dissected ovaries were fixed in 4% PFA with 0.2% Tween for 20 min and either stained with Texas Red-X Phalloidin (Invitrogen) in PBS with 2% Tween, or immunostained (as described in Palacios and St Johnston 2002). After washing with PBS, samples were mounted in Vectashield medium for fluorescent microscopy and analyzed using Leica SP confocal microscopes (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Immunostainings were performed using 1:10 monoclonal anti-Gurken (DHSB 1D12) or 1:100 monoclonal anti-Broad-core (DHSB 25E9.D7).

Yeast Two-Hybrid interactions, Upf2 transgenes, and rescue experiments

Yeast Two-Hybrid assays using the pGAD and pGBD vectors were performed using the pJ69-4A strain (MATa trp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4delta gal80delta GAL2-ADE2 LYS2∷GAL1-HIS3 met2∷GAL7-lacZ).

Drosophila upf2 cDNA was cloned into the Drosophila expression vector pUASg (Rorth 1998). Point mutations were introduced into this sequence using the QuickChange Lightening Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Flies were transformed using P-element-mediated integration. Individual insertions were double balanced over Sco/Cyo ; MKRS/TM6b and out-crossed to females carrying either the upf225G/FM7 or upf214J/FM7 mutations, as well as a constitutive tubulin-GAL4 driver on the third chromosome. Male progeny of this cross were screened for those lacking FM7, indicating that they were carrying a upf2 mutant allele. Mutant males expressing tubulin-GAL4 and transgenic upf2 (either wt or E801R) were collected and RNA extracted for qPCR as described below. These mutant males were also used for the analysis of clone growth (in combination with the MARCM system, using the same analysis as described above).

qPCR of NMD target levels

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using cDNA libraries generated from RNA extracted from ovaries, embryos, pre-pupal larvae, and adults. RNAs were extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Micro (ovaries and embryos) or Mini (pre-pupae and adults) kits, with DNAase on-column treatment to remove possible sources of genomic DNA contamination. cDNA was produced using the Invitrogen Superscript III reverse transcriptase system with oligodT primers, using between 300 and 1500 ng of RNA per reaction, dependent on the developmental stage. For each sample, triplicate biological replicates were obtained and gene expression levels assessed using primers designed to specifically amplify single products from NMD target genes. qPCR reactions were performed using the Roche Lightcycler 480 system. Reactions were repeated in triplicate for each sample, with each containing 10 ng of cDNA template and gene-specific primers at a concentration of 500 nM. The expression level of each target gene was first normalized against the constitutively expressed ribosomal gene Rp41, and then the fold change in expression of mutant samples versus controls was calculated. In all cases, Rp41 expression remained relatively constant regardless of mutant background, and preliminary analyzes using a second ribosomal protein, Rp49, indicated that either could be used as a reliable internal reference gene. Data are given as a change in fold expression in comparison to control, with SEM error bars taking into account the SEM of both control and target gene expression levels (using the formula DX = (√{(DA/A)2 + (DB/B)2}) × X), where DX is the combined error, X is the fold difference, DA is the standard error of sample A, A is the mean of sample A, DB is the standard error of sample B, and B is the mean of sample B).

The horizontal line in Figures 4–6 and Supplemental Figure S4 represents the 1.5-fold needed to indicate a meaningful result. In the literature, an increase of 1.5-fold or greater is commonly denoted as a significant change in gene expression.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Elisa Izaurralde and Javier Caceres for comments on the manuscript, discussions, and DNAs, and Mark Metzstein, Alex Gould, and Jose Casal for their generous gifts of DNA, fly stocks, and antibodies. We also thank James Tollervey, Katrina Gold, and Fan Cheung Wu for work that induced the project.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2404211.

REFERENCES

- Ajamian L, Abrahamyan L, Milev M, Ivanov PV, Kulozik AE, Gehring NH, Mouland AJ 2008. Unexpected roles for UPF1 in HIV-1 RNA metabolism and translation. RNA 14: 914–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso CR 2005. Nonsense-mediated RNA decay: A molecular system micromanaging individual gene activities and suppressing genomic noise. Bioessays 27: 463–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anczukow O, Ware MD, Buisson M, Zetoune AB, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Sinilnikova OM, Mazoyer S 2008. Does the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay mechanism prevent the synthesis of truncated BRCA1, CHK2, and p53 proteins? Hum Mutat 29: 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzalin CM, Lingner J 2006. The human RNA surveillance factor UPF1 is required for S phase progression and genome stability. Curr Biol 16: 433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzalin CM, Reichenbach P, Khoriauli L, Giulotto E, Lingner J 2007. Telomeric repeat containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends. Science 318: 798–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamieh H, Ballut L, Bonneau F, Le Hir H 2008. NMD factors UPF2 and UPF3 bridge UPF1 to the exon junction complex and stimulate its RNA helicase activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WK, Huang L, Gudikote JP, Chang YF, Imam JS, MacLean JA 2nd, Wilkinson MF 2007. An alternative branch of the nonsense-mediated decay pathway. EMBO J 26: 1820–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YF, Imam JS, Wilkinson MF 2007. The nonsense-mediated decay RNA surveillance pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 76: 51–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TB, Perrimon N 1996. The autosomal FLP-DFS technique for generating germline mosaics in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 144: 1673–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T-B, Noll E, Perrimon N 1993. Autosomal P[ovoD1] dominant female-sterile insertions in Drosophila and their use in generating germ-line chimeras. Development 119: 1359–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M, Mourao A, Gutsche I, Gehring NH, Hentze MW, Kulozik A, Kadlec J, Sattler M, Cusack S 2009. Unusual bipartite mode of interaction between the nonsense-mediated decay factors, UPF1 and UPF2. EMBO J 28: 2293–2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Hagan KW, Zhang S, Peltz SW 1995. Identification and characterization of genes that are required for the accelerated degradation of mRNAs containing a premature translational termination codon. Genes Dev 9: 423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson MR 1999. RNA surveillance. Unforeseen consequences for gene expression, inherited genetic disorders and cancer. Trends Genet 15: 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng WM, Bownes M 1997. Two signalling pathways specify localized expression of the Broad-Complex in Drosophila eggshell patterning and morphogenesis. Development 124: 4639–4647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle AB, Lykke-Andersen S, Muhlemann O, Jensen TH 2009. SMG6 promotes endonucleolytic cleavage of nonsense mRNA in human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo MI, Pueyo JI, Fouix S, Bishop SA, Couso JP 2007. Peptides encoded by short ORFs control development and define a new eukaryotic gene family. PLoS Biol 5: e106 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D, Izaurralde E 2004. Nonsense-mediated messenger RNA decay is initiated by endonucleolytic cleavage in Drosophila. Nature 429: 575–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D, Unterholzner L, Ciccarelli FD, Bork P, Izaurralde E 2003. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in Drosophila: at the intersection of the yeast and mammalian pathways. EMBO J 22: 3960–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring NH, Kunz JB, Neu-Yilik G, Breit S, Viegas MH, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE 2005. Exon-junction complex components specify distinct routes of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay with differential cofactor requirements. Mol Cell 20: 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudikote JP, Wilkinson MF 2002. T-cell receptor sequences that elicit strong down-regulation of premature termination codon-bearing transcripts. EMBO J 21: 125–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay BA, Wolff T, Rubin GM 1994. Expression of baculovirus P35 prevents cell death in Drosophila. Development 120: 2121–2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Peltz SW, Donahue JL, Rosbash M, Jacobson A 1993. Stabilization and ribosome association of unspliced pre-mRNAs in a yeast upf1- mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci 90: 7034–7038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman RT, Green RE, Brenner SE 2004. An unappreciated role for RNA surveillance. Genome Biol 5: R8 doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J, Papp A, Pulak R, Ambros V, Anderson P 1989. A new kind of informational suppression in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 123: 301–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook JA, Neu-Yilik G, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE 2004. Nonsense-mediated decay approaches the clinic. Nat Genet 36: 801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E, Kashima I, Fauser M, Sauliere J, Izaurralde E 2008. SMG6 is the catalytic endonuclease that cleaves mRNAs containing nonsense codons in metazoan. RNA 14: 2609–2617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S, Furger A, Halliday D, Judge DP, Jefferson A, Dietz HC, Firth H, Handford PA 2003. Allelic variation in normal human FBN1 expression in a family with Marfan syndrome: a potential modifier of phenotype? Hum Mol Genet 12: 2269–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isken O, Kim YK, Hosoda N, Mayeur GL, Hershey JW, Maquat LE 2008. Upf1 phosphorylation triggers translational repression during nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Cell 133: 314–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadlec J, Izaurralde E, Cusack S 2004. The structural basis for the interaction between nonsense-mediated mRNA decay factors UPF2 and UPF3. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima I, Yamashita A, Izumi N, Kataoka N, Morishita R, Hoshino S, Ohno M, Dreyfuss G, Ohno S 2006. Binding of a novel SMG-1-Upf1-eRF1-eRF3 complex (SURF) to the exon junction complex triggers Upf1 phosphorylation and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev 20: 355–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling KM, Lanier J, Du M, Salas-Marco J, Gao L, Kaenjak-Angeletti A, Bedwell DM 2004. Leaky termination at premature stop codons antagonizes nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in S. cerevisiae. RNA 10: 691–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Furic L, Desgroseillers L, Maquat LE 2005. Mammalian Staufen1 recruits Upf1 to specific mRNA 3′UTRs so as to elicit mRNA decay. Cell 120: 195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L 2001. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci 24: 251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeds P, Peltz SW, Jacobson A, Culbertson MR 1991. The product of the yeast UPF1 gene is required for rapid turnover of mRNAs containing a premature translational termination codon. Genes Dev 5: 2303–2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longman D, Plasterk RH, Johnstone IL, Caceres JF 2007. Mechanistic insights and identification of two novel factors in the C. elegans NMD pathway. Genes Dev 21: 1075–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medghalchi SM, Frischmeyer PA, Mendell JT, Kelly AG, Lawler AM, Dietz HC 2001. Rent1, a trans-effector of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, is essential for mammalian embryonic viability. Hum Mol Genet 10: 99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JT, ap Rhys CM, Dietz HC 2002. Separable roles for rent1/hUpf1 in altered splicing and decay of nonsense transcripts. Science 298: 419–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzstein MM, Krasnow MA 2006. Functions of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway in Drosophila development. PLoS Genet 2: e180 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovich QM, Anderson P 2000. Unproductively spliced ribosomal protein mRNAs are natural targets of mRNA surveillance in C. elegans. Genes Dev 14: 2173–2184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodley K, Murrell H 2004. A colour-map plugin for the open source, Java based, image processing package, ImageJ. Comput Geosci 30: 609–618 [Google Scholar]

- Neu-Yilik G, Gehring NH, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE 2004. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: from vacuum cleaner to Swiss army knife. Genome Biol 5: 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson P, Yepiskoposyan H, Metze S, Zamudio Orozco R, Kleinschmidt N, Muhlemann O 2010. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in human cells: mechanistic insights, functions beyond quality control and the double-life of NMD factors. Cell Mol Life Sci 67: 677–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi T, Yamashita A, Kashima I, Schell T, Anders KR, Grimson A, Hachiya T, Hentze MW, Anderson P, Ohno S 2003. Phosphorylation of hUPF1 induces formation of mRNA surveillance complexes containing hSMG-5 and hSMG-7. Mol Cell 12: 1187–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios IM, St Johnston D 2002. Kinesin light chain-independent function of the Kinesin heavy chain in cytoplasmic streaming and posterior localization in the Drosophila oocyte. Development 129: 5473–5485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor F, Kolonias D, Giangrande PH, Gilboa E 2010. Induction of tumour immunity by targeted inhibition of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature 465: 227–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramani AK, Nelson AC, Kapranov P, Bell I, Gingeras TR, Fraser AG 2009. High resolution transcriptome maps for wild-type and nonsense-mediated decay-defective Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol 10: R101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehwinkel J, Letunic I, Raes J, Bork P, Izaurralde E 2005. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay factors act in concert to regulate common mRNA targets. RNA 11: 1530–1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehwinkel J, Raes J, Izaurralde E 2006. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: Target genes and functional diversification of effectors. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 639–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Gabriel MA, Watt S, Bahler J, Russell P 2006. Upf1, an RNA helicase required for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, modulates the transcriptional response to oxidative stress in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 26: 6347–6356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P 1998. Gal4 in the Drosophila female germline. Mech Dev 78: 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield JB 2007. ImageJ, a useful tool for biological image processing and analysis. Microsc Microanal 13: 200–201 [Google Scholar]

- Stalder L, Muhlemann O 2008. The meaning of nonsense. Trends Cell Biol 18: 315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpey PS, Raymond FL, Nguyen LS, Rodriguez J, Hackett A, Vandeleur L, Smith R, Shoubridge C, Edkins S, Stevens C, et al. 2007. Mutations in UPF3B, a member of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay complex, cause syndromic and nonsyndromic mental retardation. Nat Genet 39: 1127–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Crespo M, Palacios IM 2010. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and development: shoot the messenger to survive? Biochem Soc Trans 38: 1500–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent MC, Pujo AL, Olivier D, Calvas P 2003. Screening for PAX6 gene mutations is consistent with haploinsufficiency as the main mechanism leading to various ocular defects. Eur J Hum Genet 11: 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chang YF, Hamilton JI, Wilkinson MF 2002. Nonsense-associated altered splicing: a frame-dependent response distinct from nonsense-mediated decay. Mol Cell 10: 951–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weischenfeldt J, Damgaard I, Bryder D, Theilgaard-Monch K, Thoren LA, Nielsen FC, Jacobsen SE, Nerlov C, Porse BT 2008. NMD is essential for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and for eliminating by-products of programmed DNA rearrangements. Genes Dev 22: 1381–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MF 2005. A new function for nonsense-mediated mRNA-decay factors. Trends Genet 21: 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp N, Huntzinger E, Weiler C, Sauliere J, Schmidt S, Sonawane M, Izaurralde E 2009. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay effectors are essential for zebrafish embryonic development and survival. Mol Cell Biol 29: 3517–3528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A, Izumi N, Kashima I, Ohnishi T, Saari B, Katsuhata Y, Muramatsu R, Morita T, Iwamatsu A, Hachiya T, et al. 2009. SMG-8 and SMG-9, two novel subunits of the SMG-1 complex, regulate remodeling of the mRNA surveillance complex during nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev 23: 1091–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]