Abstract

Synthesis of the poly(A) tail of mRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires recruitment of the polymerase Pap1 to the 3′ end of cleaved pre-mRNA. This is made possible by the tethering of Pap1 to the Cleavage/Polyadenylation Factor (CPF) by Fip1. We have recently reported that Fip1 is an unstructured protein in solution, and proposed that it might maintain this conformation as part of CPF, when bound to Pap1. However, the role that this feature of Fip1 plays in 3′ end processing has not been investigated. We show here that Fip1 has a flexible linker in the middle of the protein, and that removal or replacement of the linker affects the efficiency of polyadenylation. However, the point of tethering is not crucial, as a fusion protein of Pap1 and Fip1 is fully functional in cells lacking genes encoding the essential individual proteins, and directly tethering Pap1 to RNA increases the rate of poly(A) addition. We also find that the linker region of Fip1 provides a platform for critical interactions with other parts of the processing machinery. Our results indicate that the Fip1 linker, through its flexibility and protein/protein interactions, allows Pap1 to reach the 3′ end of the cleaved RNA and efficiently initiate poly(A) addition.

Keywords: Pap1; Fip1, polyadenylation; mRNA 3′ end processing

INTRODUCTION

Polyadenylation is an essential post-transcriptional modification of pre-mRNA in eukaryotic cells and consists of a tightly coupled two-step reaction (Mandel et al. 2008; Millevoi and Vagner 2009). The first step is a site-specific endonucleolytic cleavage of the pre-mRNA, and is followed by processive synthesis of a poly(A) tail onto the 3′ end of the upstream cleavage product, while the downstream product is degraded. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, this tail is 50–90 adenosines in length and is added by the poly(A) polymerase, Pap1 (Patel and Butler 1992). The polyadenylation reaction can be reconstituted in vitro from three purified factors. These factors are Cleavage Factor I (CF I), Cleavage/Polyadenylation Factor (CPF), and poly(A) binding protein, either Pab1 or Nab2. The proteins that comprise these factors are for the most part conserved in all eukaryotes, from yeast to mammals (Mandel et al. 2008; Millevoi and Vagner 2009). CF I binds to UA-rich and A-rich positioning sequences upstream of the cleavage site, and has been proposed to stabilize the interaction of CPF on the pre-mRNA (Fig. 1A). CPF contains Pap1, the endonuclease, and other proteins involved in cleavage and polyadenylation, and interacts with short stretches of uridines that flank the cleavage site (Preker et al. 1997; Mandel et al. 2008).

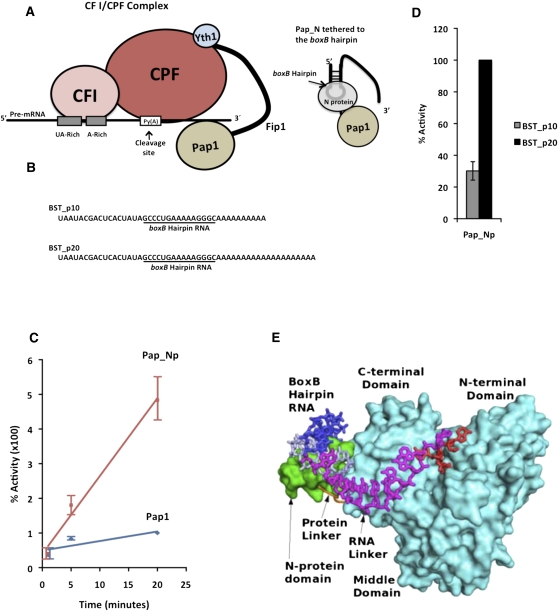

FIGURE 1.

Tethering of RNA to Pap1 increases the efficiency of polyadenylation. (A) The yeast 3′ end processing complex showing the Fip1 as a flexible protein and the tethered Pap-Np model. (B) RNA sequences of the substrates used in poly(A) addition reactions. The boxB hairpin sequence is underlined. (C) The rate of polyadenylation using BST_p20 RNA as substrate. Polyadenylation activity of Pap1 and Pap_Np was determined by incorporation of [∝-32p] ATP into the growing poly(A) at 30°C, with time points taken at 1, 5, and 20 min, followed by measurement of TCA-precipitable counts. The experiments were done in triplicate and standard error is indicated. One hundred percent activity is the activity of Pap1 after 20 min of incubation at 30°C. (D) Polyadenylation activity of the Pap_Np on BST_p10 and BST_p20 RNA substrates performed as described in C. One hundred percent activity is the activity of Pap_Np on the BST_20 substrate after 20 min of incubation at 30°C. (E) Molecular depiction of the Pap_Np–RNA interaction. The crystal structure of the boxB RNA/N–protein complex (blue/green) (Scharpf et al. 2000) was modeled at the C-terminal end of the Pap1 structure (cyan). Five nucleotides were present in the crystal structure of Pap1 with RNA (red), but not all are visible in this orientation (Balbo and Bohm, 2007). The nucleotides colored purple were modeled to span the space between those observed bound to the N-protein and Pap1.

Pap1 is linked to CPF through a direct interaction with Fip1 (Preker et al. 1995). The interaction between both proteins is conserved in humans and plants (Kaufmann et al. 2004; Forbes et al. 2006), but the atomic details of this interaction are not (Meinke et al. 2008). Fip1 in turn is held in the 3′ end complex through its interaction with Yth1 (Barabino et al. 2000). Isolated Pap1 is a distributive enzyme that releases its RNA substrate after each round of catalysis, but after recruitment by Fip1 into CPF, Pap1 behaves processively (Preker et al. 1997). Little is known about how Pap1 gains access to the 3′ end of the pre-mRNA immediately after cleavage, and the role that Fip1 plays in this process. We have found that Fip1 adopts an extended conformation in solution and maintains this conformation when bound to Pap1, suggesting that very little of Fip1 folds into an ordered structure (Meinke et al. 2008). While the structure of Pap1 with the Pap1-interaction domain of Fip1 has been determined (Meinke et al. 2008), the conformation of the rest of Fip1 when it is bound to Pap1 as part of CPF is unknown.

The goal of the current study is to better understand how Pap1 gains access to the 3′ end of pre-mRNA through its interaction with Fip1 and how it changes from a distributive to a processive enzyme when incorporated into CPF. We report here that polyadenylation is much more efficient when Pap1 is artificially tethered to the RNA substrate. We also show that a fusion protein of Pap1 and Fip1 can rescue loss of both proteins in yeast, and finally, we show that Fip1 provides a flexible linker that bridges the Pap1 and the Yth1 interaction sites of the protein.

RESULTS

Tethering of RNA to Pap1 increases the efficiency of polyadenylation

To study the role of the CPF complex in holding Pap1 on the RNA during polyadenylation, we generated a simplified model system where the RNA substrate is tethered directly to Pap1 by fusing the bacteriophage λ N protein to the C terminus of Pap1 (Fig. 1A). Tethering models of this sort have been successfully used in the study of other mRNA–protein interactions (Coller and Wickens 2007). The bacteriophage λ N protein has an arginine-rich motif that binds to the boxB hairpin RNA sequence (Scharpf et al. 2000). The Pap1-bacteriophage λ N fusion protein (Pap_Np) exhibited polyadenylation activity comparable to the untagged enzyme on an oligo A18 substrate (data not shown), indicating that the N-protein tag did not compromise enzyme function. To determine the effect of tethering on Pap1 activity, the rate of polyadenylation was measured by the incorporation of radioactive ATP onto an RNA substrate, BST_p20, which contains a boxB hairpin sequence inserted directly upstream of a 20-adenosine tract (Fig. 1B). Pap_Np added adenosines to this substrate at a rate that was 18-fold greater than that of Pap1 (Fig. 1C). This is consistent with Pap_Np having a higher affinity for the boxB hairpin loop on the BST_p20 RNA substrate.

When an RNA substrate containing only 10 adenosines beyond the boxB hairpin (BST_p10) (Fig 1D) is used, the efficiency of polyadenylation by Pap_Np is greatly reduced. As both substrates contain the boxB hairpin sequence, they should bind with the same affinity to the enzyme. Thus, the difference observed in the polyadenylation activity is most likely due to the difference in length between the hairpin sequence and the 3′ end of the RNA. To determine if this difference in activity makes physical sense, we built a molecular model of the Pap_Np fusion protein with a bound boxB hairpin and a 3′ poly(A) sequence (Fig. 1E). We placed the existing structure of the RNA-bound N-protein (Scharpf et al. 2000) near the C-terminus of the structure of Pap1 in a complex with its RNA substrate (Balbo and Bohm 2007). In this model, 15 nucleotides (nt) are needed to span the distance between the Pap1 active site and the N-protein domain to which the RNA is bound. Thus, BST_p10, which has only 10 adenosines beyond the binding site, is a poor substrate until it has been extended by additional adenosines.

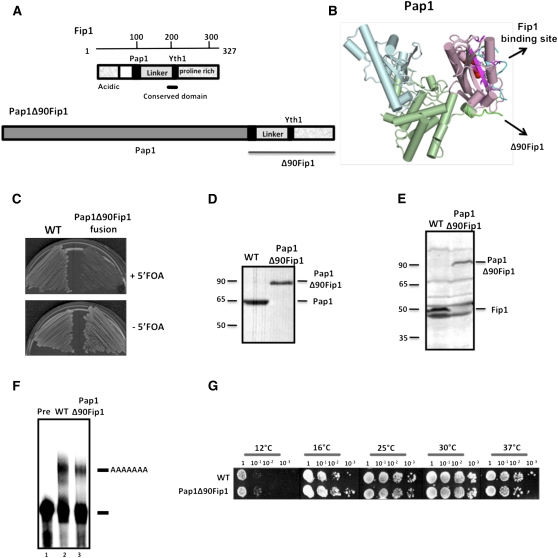

The Pap1Δ90Fip1 fusion protein restores wild-type activity in yeast strains lacking the PAP1 and FIP1 genes

To investigate the role of tethering in Pap1 activity in the context of the CPF complex, we created a yeast strain in which Pap1 is fused covalently to a truncated version of Fip1 (Fig. 2A), and expressed as a single protein in a yeast strain background where the individual PAP1 and FIP1 genes have been disrupted. Fip1 binds to the outer surface of the C-terminal domain of Pap1 through an interaction interface located within amino acids 80–105 of Fip1, with amino acid 105 of Fip1 positioned near the top of the Pap1 C-terminal domain (Fig. 2B; Meinke et al. 2008). We designed a plasmid encoding a truncated Fip1 protein lacking the N-terminal 90 amino acids (Δ90Fip1), which includes the nonessential first 80 amino acids and part of the essential Pap1 interaction domain (Fig. 2A; Helmling et al. 2001). Like the Fip1 truncation lacking the first 105 amino acids, this construct could not rescue a FIP1 gene deletion (data not shown), confirming the prediction from the structure that amino acids between positions 80 and 90 would be crucial for Pap1 interaction. The Δ90Fip1 was fused to the C-terminus of Pap1, which is located near the bottom of the C-terminal domain (Fig. 2B), and tested for viability in yeast strains that contained either a disrupted PAP1 or FIP1 gene. Both knockouts were rescued by this construct.

FIGURE 2.

The Pap1Δ90Fip1 fusion protein restores wild-type (WT) activity in yeast strains lacking the individual PAP1 and FIP1 genes. (A) Schematic diagram of Fip1 showing the Pap1 and Yth1 interaction domains, the conserved region of the protein and the flexible linker. Also shown is the Pap1Δ90Fip1 fusion protein, with Δ90Fip1 attached covalently at the C terminus of Pap1. (B) Structure of Pap1 based on Meinke et al. 2008 showing the Fip1 binding site, and the Δ90Fip1 fusion site at the C-terminus. (C) Pap1Δ90Fip1 rescues a double deletion of FIP1 and PAP1 genes. The yeast strain containing Pap1Δ90Fip1 on a URA3 plasmid and disruption of the chromosomal FIP1 and PAP1 genes were grown on medium in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 5-FOA, which forces the loss of URA3 plasmid. No growth is observed on 5-FOA in the absence of Pap1Δ90Fip1. As would be expected, a ura3 strain with intact FIP1 and PAP1 genes (WT) grows in both conditions. (D) The Pap1Δ90Fip1 fusion protein is expressed in the yeast strain. Western blotting using Pap1 monoclonal antibody performed on yeast extracts shows the loss of individual Pap1 protein, and the presence of the fusion protein. (E) Western blotting using Fip1 polyclonal antibody on yeast extracts shows the loss of individual Fip1 protein and the presence of the fusion protein in Pap1Δ90Fip1 extract. (F) In vitro poly(A) addition assay at 30°C using a precleaved GAL7 RNA substrate ending at the poly(A) site. Unreacted precursors are shown in the lane marked “Pre,” and the position of polyadenylated RNA is indicated on the right. (G) Thermosensitivity tests on the wild-type and yeast strains containing the Pap1Δ90Fip1 fusion protein. The URA3 plasmid carrying Pap1Δ90Fip1 was introduced into the yeast strain as described in Materials and Methods. The yeast strains were grown overnight in liquid culture, and their cell densities were normalized to an OD of 1. Serial dilutions of the liquid cultures by a factor of 10 were spotted on YPD medium and incubated at the indicated temperatures for up to 120 h.

To test whether this fusion can cover the loss of the chromosomal copies of the essential PAP1 and FIP1 genes together, yeast strains containing the double knockout of both genes were made by mating individual haploid strains with each single gene disrupted by a different selectable marker. The resulting diploid cells were transformed with a URA3-marked plasmid carrying the PAP1Δ90FIP1 construct and then sporulated and the tetrads were dissected. After sporulation, the viable haploid cells with both the FIP1 and PAP1 gene disruptions all contained the PAP1Δ90FIP1 plasmid. No cells survived the double gene disruption without a plasmid, indicating as expected that a double disruption of PAP1 and FIP1 is lethal to yeast. To confirm that the PAP1Δ90FIP1 construct rescues the double deletion of PAP1 and FIP1, the double knockout cells were tested for growth on a medium containing 5-FOA, a reagent that is toxic to yeast cells expressing URA3 (Fig. 2C). The yeast strains carrying the PAP1Δ90FIP1 construct cannot grow on 5-FOA, when loss of the covering plasmid is forced.

Western blot analysis with a monoclonal Pap1 antibody (Fig. 2D) and a polyclonal Fip1 antibody (Fig. 2E) showed that the individual Pap1 and Fip1 proteins found in isogenic wild-type cells had been replaced by the fusion protein in the Pap1Δ90Fip1 strain. Thermosensitivity testing showed no growth defects at different temperatures compared to the wild-type control (Fig. 2G), confirming that having Pap1 and Fip1 combined into one polypeptide is functionally equivalent to the individual Pap1 and Fip1 proteins found in wild-type cells. In support of this conclusion, analysis of the in vitro processing activity of extract made from cells expressing Pap1Δ90Fip1 showed a slightly reduced polyadenylation efficiency, but normal tail length, when compared to the wild-type (Fig. 2F). In these assays, a radiolabeled GAL7 RNA substrate ending at the GAL7 poly(A) site was incubated with extract and ATP. Analysis of total RNA from these yeast strains using a previously described method to specifically visualize poly(A) tails (Preker et al. 1995; Kessler et al. 1997) also showed that poly(A) tails formed in vivo were normal in length (data not shown). From these results, we conclude that disruption of the Fip1/Pap1 interaction is not needed at any time during 3′ end processing, and that the precise point of contact on the Pap1 C-terminal domain is not important. Consistent with this model, the residues that mediate the interaction between yeast Pap1 and Fip1 are not conserved in higher eukaryotes (Meinke et al. 2008).

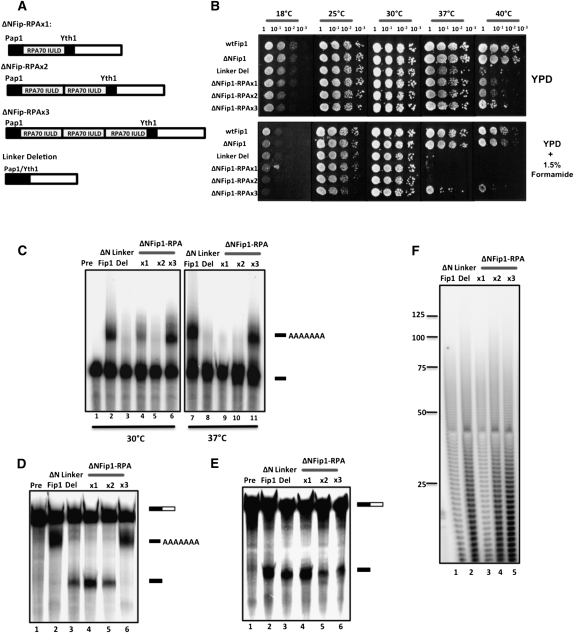

An intrinsically unstructured linker domain is important for Fip1 function in polyadenylation

Our previous biochemical data have shown that Fip1 adopts an extended conformation in solution and also maintains this conformation when bound to Pap1 (Meinke et al. 2008). These observations suggest that very little of Fip1, except the small parts directly contacting Pap1 and Yth1, folds into an ordered structure, which is characteristic of intrinsically unstructured proteins (IUPs) (Fink 2005). IUPs are proteins or regions of proteins that have no compact globular domains. In one class of these proteins, an intrinsically unstructured linker domain (IULD) tethers flanking folded domains and allows the mobility needed for these domains to interact with other proteins and nucleic acids (Jacobs et al. 1999). These proteins show no sequence conservation in the linker, but mobility is conserved across different species (Daughdrill et al. 2007). The resemblance of Fip1 to these proteins can help explain how Pap1 gains access to the 3′ end of the pre-mRNA after cleavage.

To test if Fip1 acts as a flexible tether when bound on one end to Pap1 and on the other to Yth1 in the intact CPF complex (Fig. 1A), amino acid residues 106–190 of Fip1, which is the region between the Pap1 and Yth1 interaction sites, was replaced with a similar-sized segment containing the IULD of the human replication protein A (RPA70) (Fig. 3A). Previous studies have used the 72 amino acid IULD of RPA70 as a model for studying intrinsic unstructured proteins (Daughdrill et al. 2007). For this study, we used the ΔNFip1 construct, which lacks the nonessential 80 amino acids at the N terminus, and behaves like full-length Fip1 (Helmling et al. 2001). Extra copies of the RPA70 IULD linker were also introduced to study the effect of increasing the length of this putative flexible linker, and a Fip1 construct lacking the linker region and juxtaposing the Pap1 and Yth1 interaction sites was made to test the consequence of losing the linker all together (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

An intrinsically unstructured linker domain is important for Fip1 function in polyadenylation. (A) Schematic diagram of modified ΔNFip1 showing the substitution of Fip1 sequence between the Pap1 and Yth1 interaction domains with copies of the RPA70 IULD. (B) Thermosensitivity tests on the wild-type Fip1 (wtFip1), ΔNFip1, and the modified ΔNFip1-RPA70 yeast strains on YPD media, and YPD media supplemented with 1.5% formamide, performed as described in Fig. 2G. Plasmids carrying the indicated constructs of FIP1 were introduced into the PJP22 yeast strain by plasmid shuffling (Helmling et al. 2001). (C) In vitro poly(A) addition assays at 30°C and 37°C using precleaved 32P-labeled GAL7 RNA ending at the poly(A) site and extracts from the indicated strains were performed as described (Helmling et al. 2001). (D) In vitro coupled cleavage and poly(A) addition assays at 30°C using an uncleaved 32P-labeled GAL7 RNA substrate, which contains a poly(A) site and flanking sequence and the same extracts used in C. (E) In vitro cleavage assays at 30°C using an uncleaved 32P-labeled GAL7 RNA substrate, which contains a poly(A) site and flanking sequence and the same extracts used in C. (F) Poly(A) tail length in ΔNFip1p and the modified ΔNFip1p-RPA70 yeast strains were normal when grown at 30°C. ΔNFip1 yeast strains grown overnight in YPD were diluted to an OD of 0.1, and grown at 30°C for ∼6 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at an OD of 0.8 and total yeast RNA was isolated from cells using a modification of the hot phenol method (Köhrer and Domdey 1991). Labeling, RNAse digestion, and visualization of poly(A) tails were performed as described previously (Preker et al. 1995, Kessler et al. 1997).

All of the ΔNFip1 constructs were viable in the absence of the wild-type Fip1 protein (Fig. 3B). Thermosensitivity tests on the constructs showed normal growth at all temperatures, except 40°C where slower growth is observed in all constructs except wild-type Fip1 and ΔNFip1 (Fig. 3B). In the presence of 1.5% formamide, which is thought to further destabilize protein/protein interactions within cells (Hampsey 1997), thermosensitivity tests showed a growth defect at 37°C in the absence of the Fip1 linker, which persisted if the linker was replaced with one or two copies of the RPA70 IULD (Fig. 3B). The growth defect was however partially rescued in the presence of three copies of the RPA70 IULD. These results indicate that the linker region of Fip1 is important for cell growth, but that it cannot simply be replaced by an IULD of similar length.

To study the role of the Fip1 linker in polyadenylation, in vitro assays were performed using radiolabeled GAL7 RNA substrates ending at the GAL7 poly(A) site. Extract from the yeast strain expressing a deletion of the Fip1 linker showed very low polyadenylation activity at 30°C and 37°C, and few of the tails reached the normal length seen in the ΔNFip1 extract (Fig. 3C, lanes 3,8). Low polyadenylation activity is also observed in extract from yeast strains in which the Fip1 linker was replaced with one or two copies of RPA70 (Fig. 3C, lanes 4,5,9,10), while full polyadenylation activity is restored when the linker is substituted with three copies of RPA70 (Fig. 3C, lanes 6,11). In this case, the size of the poly(A) tail is normal, indicating that the tether is probably not functioning as a ruler for tail length. An in vitro cleavage and polyadenylation assay using uncleaved radiolabeled GAL7 RNA was used to test the effect of the Fip1 modifications on the cleavage step, when cleavage and polyadenylation are coupled. A cleaved, unadenylated product accumulates in extracts containing constructs with the linker deletion, or with the one and two RPA70 replacements, while polyadenylation is restored with three RPA70 replacements (Fig. 3D). Cleavage was also normal in all constructs (Fig. 3E). This result confirms that CF I and CPF polyadenylation factors in the extracts are competent for cleavage, the Fip1 linker is not involved in cleavage, and modification of the Fip1 linker has inhibited polyadenylation. Yeast containing the ΔNFip1, ΔNFip1-RPAx1, ΔNFip1-RPAx2, ΔNFip1-RPAx3, and the linker deletion forms of Fip1 produced normal poly(A) tail lengths in vivo at 30°C (Fig. 3F), in agreement with the normal growth at this temperature (Fig. 3B).

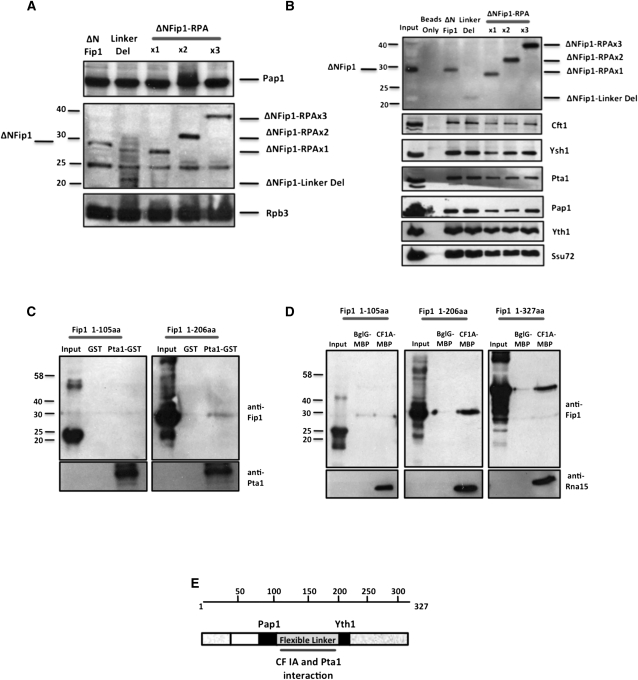

Western analysis was used to detect the modified forms of Fip1 in the extract, the absence of the wild-type Fip1 protein, and the presence of normal levels of Pap1, showing that the low polyadenylation efficiency observed in some of the extracts in the in vitro assays was not due to a lack of Pap1 or poor expression of the mutant Fip1 proteins (Fig. 4A). To confirm that the Fip1 modifications did not affect recruitment of Pap1 into the CPF complex in these samples, immunoprecipitation using anti-Fip1 antibodies showed that the association of Pap1 and other selected subunits of CPF with Fip1 did not change as a consequence of alterations, which caused poor poly(A) addition (Fig. 4B). In summary, these experiments show that the linker region of Fip1 between the Pap1 and Yth1 interaction sites is important for polyadenylation, and that three copies of a flexible RPA 70 IULD can reconstitute the polyadenylation function of this linker.

FIGURE 4.

The flexible linker of Fip1 interacts with components of CPF. (A) Western blot analysis showing the presence of Pap1 and the mutant Fip1 proteins in yeast extract. Rpb3 was used as a loading control. The band at 25 kDa is a nonspecific protein, which is detected with the polyclonal Fip1 antibody. (B) Immunoprecipitation of Fip1 and associated proteins from extract with anti-Fip1 rabbit polyclonal antibody followed by Western blot detection of Fip1 and the indicated CPF proteins. For immunoprecipitation reactions, 100 μL of protein A-agarose was incubated with extracts (200 μg total protein) from ΔNFip1 yeast strains and incubated overnight at 4°C as described previously (Helmling et al. 2001). Input contains 20 μg total protein of ΔNFip1 yeast extract. (C) The flexible linker of Fip1 interacts with Pta1. Western blot analysis of pull-downs using purified recombinant GST-Pta1 and purified recombinant Fip1 truncations containing 1–105 amino acids (without Fip1 linker) and 1–206 amino acids (with Fip1 linker). Control pull-downs used GST only. (D) The flexible linker of Fip1 interacts with CF 1A. Western blot analysis of pull-downs using CF IA made from recombinant Rna14, Rna15, Pcf11, and MBP-tagged Clp1. CF IA was mixed with the Fip1 truncations or full-length Fip1 (1-327), followed by purification of complexes on amylose resin. MBP-tagged BglG, an E. coli protein, was used in control pull-downs. Western blot of Rna15 is used to detect the amount of CF IA in each pull-down. (E) Schematic diagram of Fip1 showing the Pap1 and Yth1 interaction domains, and the flexible linker of Fip1, which interacts with CF IA and Pta1.

The function of the Fip1 linker region could not be restored by one or two copies of the RPA IULD, suggesting that this region may have additional roles, such as interaction with other subunits of the processing complex. Since Fip1 has been reported to interact with Rna14 of CF I and Pta1 of CPF in vitro (Preker et al. 1995; Ghazy et al. 2009), we tested whether these interactions were dependent on the flexible linker of Fip1. For these assays, we used two C-terminal truncations of Fip1—one which included the linker region (Fip1, 1-206) and one which completely lacked it (Fip1, 1-105)—in pull-downs with either GST-tagged Pta1 or MBP-tagged CF IA, which is a subcomplex of CF I that contains Rna14, Rna15, Clp1, and Pcfll, but lacks the Hrp1 protein (Kessler et al. 1996). Interaction between Pta1 and CF IA was detected with the longer Fip1 construct, but lost with the 1–105 form (Fig. 4C,D). This suggests that the linker interacts with other subunits of mRNA 3′ end processing complex to appropriately position Pap1 for efficient poly(A) addition.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated how Pap1 gains access to the 3′ end of pre-mRNA through its interaction with Fip1 and how it changes from a distributive to processive enzyme when part of the CPF complex. We created a simplified model of CPF by fusing Pap1 to the λ phage N-protein domain, which then recognized the boxB hairpin on the RNA substrates used in our experiments. By increasing the affinity of Pap1 for the RNA, this artificial tethering increased the efficiency of polyadenylation (Fig. 1C). This is similar to the processive activity observed when human PAP is in a complex with hFip1 and RNA (Kaufmann et al. 2004). Like its yeast homolog, hFip1 binds to PAP, but unlike the yeast Fip1, it has a C-terminal RNA binding domain that is sufficient to tether PAP to an RNA precursor and initiate polyadenylation (Kaufmann et al. 2004). In yeast, RNA interactions provided by other subunits of the processing complex are needed to lock Pap1 onto the RNA substrate for processive polyadenylation.

We also found that the length of the RNA substrate affects the efficiency of polyadenylation when Pap1 is tethered to the RNA. Our results show a threefold decrease in polyadenylation activity with a substrate that has only 10 nt between the tethering site and the 3′ end, compared to one in which this distance is extended to 20 nt. The 3′ end of an RNA with only 10 nt from the binding site probably cannot easily reach the Pap1 active site, thereby significantly reducing the initial extension of the poly(A) tail when compared to the longer substrate. This distance is consistent with our molecular model of the tethered Pap1–RNA interaction (Fig. 1E), which suggests that ∼15 nt are needed to span this distance. CPF is thought to define the cleavage site by recognizing short U-rich tracts that flank the poly(A) site. The upstream tract is generally 10 nt or closer to the cleavage site (Preker et al. 1997; Graber et al. 1999). Structural analysis of the ternary complex of Pap1, RNA, and ATP has shown that 4 nt are needed to reach from the active site of Pap1 to the surface of the enzyme (Balbo and Bohm 2007). Together, these findings suggest that at some poly(A) sites, maintaining an RNA contact with CPF in a post-cleavage complex may not be sterically compatible with Pap1 initiating polyadenylation on the new 3′ end. In such situations, the interaction of CF I with RNA sites further upstream, paired with cross-factor connections to CPF, may become more important in holding Pap1 on the RNA. The addition of adenosines would then allow CPF to re-engage the substrate and enhance processivity.

We also examined other parameters that might affect Pap1 activity at the 3′ end of the pre-mRNA when it is complexed with CPF. We showed that Pap1 covalently linked to a shortened, unviable form of Fip1 was able to rescue a combined deletion of the individual PAP1 and FIP1 genes, and extract from this strain was active for polyadenylation in vitro (Fig. 2F). Previous studies have shown that Fip1 holds Pap1 in CPF (Barabino et al. 2000; Helmling et al. 2001). Our data suggest that the attachment point of Pap1 to Fip1 is not as important in the cell as the recruitment of Pap1 onto the RNA, which allows efficient initiation of polyadenylation. This is consistent with our simplified CPF model and with the mammalian and plant systems, where Fip1 contains RNA-binding domains (Kaufmann et al. 2004; Forbes et al. 2006.)

The ability of Pap1 to gain access to the 3′ end of the freshly cleaved RNA substrate in the 3′ end processing complex has always been a puzzle. The number of proteins needed for pre-mRNA cleavage is quite large, and one might expect that this bulky complex would occlude Pap1 from the 3′ end. One solution to this problem might lie in the flexibility conferred by the extended linker between the Pap1 and Yth1 interaction sites on Fip1, which behaves like an IULD. An analogous protein is RPA70, whose IULD tethers two high-affinity single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding domains to an amino-terminal protein interaction domain. This tethering provides the mobility needed for simultaneous interactions with ssDNA and other proteins, and helps ssDNA compete with p53 for binding to the amino terminus of RPA70 (Miller et al. 1997; Jacobs et al. 1999; Daughdrill et al. 2001). Studies on the behavior of IULDs have shown that even though their sequence is not conserved, their dynamic behavior as tethers, which offer backbone flexibility to proteins, is evolutionarily conserved across most species (Daughdrill et al. 2007).

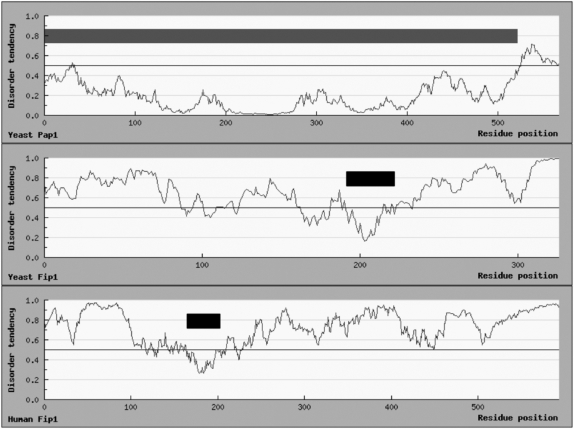

Close examination of human Fip1 reveals properties that are consistent with an IULD-containing protein. Like Fip1, hFip1 displays very low sequence conservation across species, has an apparent size by gel mobility that is higher than that predicted from amino acid sequence, and parts of the protein are very susceptible to proteolysis (Kaufmann et al. 2004). Furthermore, prediction of the domain structure of yeast Fip1, hFip1, and Arabidopsis Fip1 using IUPred (Dosztányi et al. 2005), indicate a high degree of unstructured regions in the proteins (Fig. 5). The predicted globular domains in the Fip1 proteins correspond to the conserved regions, which interact with CPSF 30 in hFip1 and its homolog, Yth1, in Fip1.

FIGURE 5.

Prediction of the domain compositions of yeast Pap1, yeast Fip1, and human Fip1 using IUPred (Dosztányi et al. 2005). Protein sequences were entered into the IUPred web server, which generated the disorder tendency of different regions of the proteins. Yeast Pap1 was used to test the accuracy of the predicted domains. The gray box represents the predicted globular domain of yeast Pap1, which corresponds to the published Pap1 structure (Bard et al. 2000), and the short region at the C-terminus known to be unstructured. The black boxes represent the predicted globular domains of yeast and human Fip1.

Surprisingly, a yeast strain expressing a mutant Fip1 completely missing the linker region exhibited wild-type growth at 30°C (Fig. 3B). This is consistent with our conclusion that initiation of polyadenylation in vivo depends mostly on adequate tethering of Pap1 to the RNA, and that once primed, mRNAs can become sufficiently polyadenylated for cell survival. However, this minimal Fip1 functioned poorly in polyadenylation in vitro, with little precursor receiving a tail, and with a few of those tails reaching a normal length, suggesting that the linker is necessary for efficient initiation of poly(A) addition in our processing extract. This is reflected by an inability to grow at 37°C in the presence of 1.5% formamide (Fig. 3B). We propose that the linker in Fip1 not only tethers Pap1 to the CPF complex, but also provides the flexibility needed to effectively access the 3′ end of the cleaved pre-mRNA.

However, the observation that one or two copies of the similar-sized RPA70 IULD cannot restore the function of the Fip1 linker in vivo or in vitro suggests that this region has additional roles. We have shown that the Fip1 linker interacts in vitro with other proteins of mRNA 3′ end processing apparatus, including the CF IA complex and the Pta1 subunit of CPF (Fig. 4E), and it is likely that these interactions facilitate Fip1 activity in the cell. This interaction between Fip1 and CF IA is conserved across species. CstF 77, which is the homolog of the Rna14 subunit of CF IA, interacts with Fip1 in humans (Kaufmann et al. 2004), and plants (Forbes et al. 2006; Addepalli and Hunt 2008). Unlike the Fip1/Yth1 interaction, these contacts are not needed to hold Fip1/Pap1 in the CPF complex (Fig. 4B). However, when the normal nuclear environment is disturbed by the presence of formamide and a higher than optimal growth temperature or by the preparation of processing extracts, such interactions may become more critical, leading to the thermosensitive growth and the poor polyadenylation that we have observed in vitro. Nevertheless, three copies of the RPA70 IULD were sufficient to partially suppress the thermosensitive growth phenotype, and gave wild-type activity in processing extract, indicating that the need for these additional interactions can be overcome if the linker is flexible and sufficiently long.

The Fip1 linker might also be an important target for the nuclear mRNA surveillance machinery. Saguez et al. (2008) have shown that mutation of the THO complex or Sub2 leads to the degradation of Fip1 through a mechanism dependent on the proteasome (Saguez et al. 2008). The resulting slow-down of polyadenylation is thought to make it easier for the nuclear exosome to degrade the defective mRNPs assembled in these mutants. We had previously found that prolonged depletion of the Glc7 phosphatase caused loss of poly(A) addition, as well as Fip1 depletion (He and Moore 2005). In both cases, Pap1 levels were normal. These findings suggest that Fip1 is particularly susceptible to degradation. One of the features of intrinsically disordered proteins is their potential for rapid degradation (Fink 2005), and indeed, natively unfolded proteins like tau and unmodified alpha-synuclein can be directly processed by the proteasome without a requirement for ubiquitination (Tofaris et al. 2001; David et al. 2002). Other evidence indicates that increased phosphorylation of CPF causes a weakened association of Fip1, which might expose the linker and facilitate its degradation (He and Moore 2005). Pap1 is a target for post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and sumoylation, which either inhibit its activity or change its cellular localization (Colgan et al. 1996, 1998; Mizrahi and Moore 2000; Vethantham et al. 2008). Together, the research on Fip1 suggests that controlling Fip1 levels may be another way for the cell to regulate its polyadenylation capacity.

Our results extend our understanding of the functions of Pap1 and Fip1 as part of the 3′ end-processing complex. We show that Fip1 is a flexible linker that facilitates the access of Pap1 to the 3′ end of substrate mRNA and also provides a platform for critical interactions with other parts of the processing machinery. Further work on the Fip1 function is needed to define the role that its unstructured domain plays in the regulation of 3′ end processing and mRNA surveillance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmid preparation

All the yeast strains used in this study were derived from strain PJP22 (MATα leu2-3, 112, ura3-53 trp1 his4 fip1∷LEU2 pIA34 [CEN4 URA3 FIP1]), which was described previously (Helmling et al. 2001). The Pap1Δ90Fip1∷PAP1/FIP1 strain was made by mating a SH1A yeast strain (PJP22 fip1∷LEU2, pRS314/FIP1(TRP)) with ATCC 200868 (MATα ade2Δ∷hisG his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 met15Δ0 trp1Δ63) to create an appropriately marked strain. The cells were then sporulated, dissected, and selected for a Leu+, Trp+, Ura−, His− phenotype, and then mated with W303 (MATα {leu2-3, 112 trp1-1 can1-100 ura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11, 15} [phi+]). The resulting diploid cells were transformed with a SacI/PvuII Pap1 fragment in which the portions from SnaBI to StuI were replaced with a HIS3 gene to disrupt the PAP1 gene. Disruption of the PAP1 gene was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. These diploid cells, which contained a disruption of one copy of FIP1 and one copy of PAP1, were transformed with the pHCP50/PAP1Δ90FIP1 (URA3) plasmid, sporulated, and dissected to identify haploid cells with the knockouts of FIP1 and PAP1 covered by the pHCP50/PAP1Δ90FIP1 (URA3) plasmid. An isogenic wild-type strain was made by transforming the SH1A strain with two plasmids containing wild-type FIP1 and PAP1 (YCp50/PAP1 and RS314/FIP1), and plating on selective medium containing 5-FOA. The yeast colonies that grew on this medium were then tested on medium lacking tryptophan and leucine, which confirmed the presence of the two plasmids. ΔNFip1-RPA constructs were made by introducing a 72 amino acid section of RPA 70 into p314ΔNFip1 (Helmling et al. 2001). The RPA sequence was obtained by PCR from the p11dtRPA plasmid. The three RPA strains were made sequentially from one to three using three sets of primers for PCR on the p11dtRPA plasmid. They are as follows: For ΔNFip1-RPAx1, RPA1-5′: CGGCGGGTAGCTAGCGGAGTGAAGATTGGCAATCCAGTG, and RPA1-3′: ATAATCACTTAAGTTGGCCCCCGGTTGCCTCCACATATGCCATGGCTGTGTTCCCCCAGAAGTGTG. For ΔNFip1-RPAx2, RPA2-5′: CGGCGGGTACCATGGGGAGTGAAGATTGGCAATCCAGTG, RPA2-3′: ATAATCACTTAAGTTGGCCCCCGGTTGCCTCCACTGTGTTCCCCCAGAAGTGTG. For ΔNFip1-RPAx3, RPA3-5′: CGGCGGGTACATATGGGAGTGAAGATTGGCAATCCAGTG and RPA3-3′: ATAATCACTTAAGTTGGCCCCCGGTTGCCTCCACTGTGTTCCCCCAGAAGTGTG. ΔNFip1-RPAx1 was made by ligation, after cutting p314ΔNFip1 and the PCR #1 with NheI and NdeI. ΔNFip1-RPAx3 was made by ligation after cutting ΔNFip1-RPAx1 and the PCR #3 with NdeI and AflII. ΔNFip1-RPAx2 was made by ligation after cutting ΔNFip1-RPAx3 and PCR #2 with NcoI and NdeI. The ΔNFip1 linker-deletion construct was made by introducing an NheI site at position 340 of the ΔNFip1-RPAx1 sequence by site-directed mutagenesis using the Quick-change protocol (Stratagene). The plasmid was cut with NheI, separated from the released linker region fragment by gel electrophoresis, and ligated to itself.

The ΔNFip1-RPA yeast strains were obtained by plasmid shuffling. Plasmids containing variations of ΔNFip1-RPA were introduced into PJP22 by transformation using the lithium acetate method (Becker and Guarente 1991), and plated on a complete medium lacking uracil and tryptophan. Transformants were isolated, grown in liquid media, and plated on a synthetic complete medium containing 1 mg/mL of 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA). Colonies growing on 5-FOA were re-examined to confirm loss of the URA3 plasmid, and the presence of the correct construct was verified by Western blotting using polyclonal Fip1 antibody as described (Helmling et al. 2001). Monoclonal Pap1 antibody at a 1:100 dilution was used for detecting Pap1 (Kessler et al. 1995). To compare growth rates, cells were grown overnight at 30°C in liquid media. Cell densities were normalized by dilution with fresh media, and equal volumes of 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted on YPD plates or on YPD plates supplemented with 1.5% formamide, and incubated as indicated in the figure legends.

Yeast poly(A) polymerase tethered to bacteriophage λ N protein (Pap_Np) was constructed using the PAP1Δ10-His6 plasmid (Balbo et al. 2005). The PAP1Δ10-His6 plasmid encodes yeast Pap1 with a 32 amino acid truncation at the C-terminal end and a C-terminal His6 tag for purification purposes. Deletion of the C-terminus and addition of the His6 tag does not compromise enzymatic activity and results in a more soluble, better behaved protein than the wild-type enzyme. PCR was used to generate a bacteriophage λ N protein DNA with a C-terminal His6 tag, which contained the BlpI/BpuI restriction site at the 5′ end, and the XhoI restriction site at the 3′ end. The primers used for the PCR were 5′ TATTATCTCGAGGCCGCCATGGATGCACAAACACGCCGCCGCG-3′ (NPFXX1) and 5′ AATATTGCTCAGCGGAGGTGGTGTGGTGGTGGTGGGGATTTGCTGCTTTCCATTGAGCCTG-3′ (NPRXX1). The PCR product and the PAP1Δ10-His6 plasmid were cleaved with Blp1 and XhoI, and ligated to create the PAP1_N-His6 plasmid. Sequencing confirmed the presence of the PAP1 sequence followed by a short double alanine linker, the N protein and a His6 tag (Pap_Np).

In vitro mRNA 3′ end processing assays

Preparation of yeast whole cell extract was done as described (Zhao et al. 1999). After ammonium sulfate precipitation, the protein was resuspended in 200 μL of Buffer D (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 2 μM pepstatin A, 0.6 μM leupeptin), and dialyzed twice against 2 L of the same buffer for 2 h, and then overnight. Processing assays using full-length and precleaved 32P-labeled RNA were done as described (Helmling et al. 2001). dATP was used for cleavage only reactions, whereas ATP was used for the poly(A) addition and the coupled cleavage and poly(A) addition reactions.

In vivo RNA analysis

For the analysis of poly(A) tails, ΔNFip1 yeast strains were grown in YPD overnight to an approximate OD600 of 26.0. The yeast strains were diluted using prewarmed YPD to an OD of 0.1, and grown at 30°C for ∼6 h Cells were harvested by centrifugation at OD 0.8 and stored at −20°C. Total yeast RNA was isolated from cells using a modification of the hot phenol method (Köhrer and Domdey 1991). Labeling, RNAse digestion, and visualization of poly(A) tails were performed as described previously (Preker et al. 1995, Kessler et al. 1997).

Protein expression and purification

The Pap_Np- His6 plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL-21 (DE3) cells, over-expressed, and purified as described for PAP1Δ10 (Balbo et al. 2005). The purified protein was concentrated using a Millipore 30-kDa centrifugation filter. A buffer (40 mL), consisting of 15% glycerol, 30 mM potassium phosphate of pH 6.8, 20 mM NaCl, and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, was used to wash and replace the previous buffer. Pap_Np was further concentrated using a 10-kDa Millipore centrifugation filter at 12,000 rpm until the volume was 300 μL. Small aliquots of 50 μL were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Protein expression and in vitro protein–protein interaction assays

Immunoprecipitation reactions using processing extracts (200 μg total protein) from ΔNFip1 yeast strains and 100 μL of protein A-agarose (Gibco) were performed as described (Helmling et al. 2001). The Fip1 1–105 amino acid and the Fip1 1-206 amino constructs have been described previously (Helmling et al. 2001). All protein expression was performed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3), and expression and purification was performed as described (Zhelkovsky et al. 1995). GST pull-downs were performed using a modification of the protocol described by Ghazy et al. (2009). GST-tagged proteins were incubated with previously washed glutathione-Sepharose beads in 200 μL of buffer IP-150 (10 mM Tris [pH 7.9], 150 mM NaCl, 0.25M EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1M DTT, 1% NP-40, and protease inhibitors) for 2 h at 4°C, with gentle shaking. After incubation, the beads were pelleted at slow speed and washed four times with buffer IP-150. The samples were then incubated with the recombinant protein of interest in buffer IP-150 for 2 h at 4°C. After incubation, the beads were pelleted at slow speed and washed four times with buffer IP-150. To elute the proteins, beads were incubated with buffer IP-150 containing 50 mm glutathione at 4°C for 1 h with gentle shaking. The CF IA complex was incubated with MBP beads at 4°C for 2 h in buffer IP-300, which contains all the components of buffer IP 150 except for 300 mM NaCl. After incubation, the beads were pelleted at slow speed and washed four times with buffer IP-300. Pull-downs with the wild-type Fip1 and Fip1 truncations were performed for 2 h at 4°C with gentle shaking. After incubation, the beads were pelleted at slow speed and washed four times with buffer IP-150. To elute the proteins, the beads were resuspended in 1X SDS buffer, boiled for 5 min, and pelleted. The eluted proteins were either frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C or run on SDS PAGE gels, and analyzed by Western blotting.

Western blot analyses

Proteins expression and protein–protein interactions were analyzed using Western blotting. Extracts used for Western blots were made by growing the yeast in 10 mL of YPD overnight. The sample was then pelleted, and resuspended in 300 μL of lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES at pH 7.4, 100 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 10% glycerol and protease inhibitors) in a 1.5 mL eppendorf tube. Three hundred microliters of glass beads were added to the sample and vortexed for 5 min at a maximum speed at 4°C. After vortexing, the samples were pelleted at maximum speed, and the supernatant containing the protein was removed, and used for Western analysis. Extracts were resolved on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel, and proteins were transferred onto Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride (Millipore) membranes. A 1:100 dilution of monoclonal mouse Pap1 antibody was used for analyzing Pap1 samples. For Fip1 analysis, a 1:100,000 dilution of monoclonal mouse Fip1 antibody was used. The rest of the antibody dilutions are as follows: Cft1—1:6000 dilution of polyclonal rabbit antibody; Brr5—1:6000 dilution of polyclonal rabbit antibody; Pta1—1:16,000 dilution of monoclonal mouse antibody; Cft1—1:6000 dilution of polyclonal rabbit antibody; Yth1—1:6000 dilution of polyclonal rabbit antibody; and Ssu72—1:6000 dilution of polyclonal rabbit antibody. A glutathione S-transferase (GST) antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences-Pharmingen, and a GAL4-DBD (RK5C1) antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Polyadenylation kinetics

The specific activity of Pap_Np was determined as described by Balbo et al. (2005). The boxB hairpin loop RNA (Fig. 1A) were obtained from Dharmacon, Inc (Thermo Scientific) and deprotected according to directions. All reactions were conducted at 30°C using an assay that measured incorporation of [α-32p] ATP (PerkinElmer) into the growing poly(A) tail. The components of the reaction were equilibrated at room temperature for 15 min, and each sample contained 2 μL of 5X T3/T7 buffer solution (Promega), 2 μL of BSA (10 mg/mL), 0.2 μL MgCl2 (1 M), 0.2 μL spermidine (0.1 M), 1 mM ATP, 20 μCi of [α-32P] ATP and autoclaved distilled water for a total of 10μL. The reaction was initiated by adding a 10 μL mix containing Pap1 or Pap_Np (50 ng) and the RNA substrates (0.015 μM). After incubation for the indicated times at 30°C, the reaction was stopped with 150 μL of ice-cold 15% TCA. A control reaction that contained the same components without poly(A) polymerase was performed to determine the background signal. Samples were then incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 16,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The precipitated pellet was washed with ice-cold 15% TCA and dissolved in 10 mM NaOH and 0.1% SDS. Using liquid scintillation counting, [α-32P] levels were measured in counts per minute. The experiments were done in triplicate and the final results were obtained by subtracting the background signal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant no. GM041752 for C.L.M. We thank Dr. Peter Bullock (Biochemistry Department, Tufts University) for the p11dtRPA plasmid, Dr. Andrew Wright (Microbiology Department, Tufts University) for the BglG-MBP protein, Dr. James Gordon (Biochemistry Department, Tufts University) for the purified CF IA complex, Dr. Gretchen Meinke (Biochemistry Department, Tufts University) for making the molecular model, and Dr. Paul Balbo (Biochemistry Department, Tufts University) for his help in generating the Pap_Np protein. We also thank members of the Moore and Bohm labs for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2273111.

REFERENCES

- Addepalli B, Hunt AG 2008. The interaction between two Arabidopsis polyadenylation factor subunits involves an evolutionarily-conserved motif and has implications for the assembly and function of the polyadenylation complex. Protein Pept Lett 15: 76–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbo PB, Bohm A 2007. Mechanism of poly(A) polymerase: structure of the enzyme-MgATP–RNA ternary complex and kinetic analysis. Structure 15: 1117–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbo PB, Meinke G, Bohm A 2005. Kinetic studies of yeast poly(A) polymerase indicate an induced fit mechanism for nucleotide specificity. Biochemistry 44: 7777–7786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabino SM, Ohnacker M, Keller W 2000. Distinct roles of two Yth1p domains in 3′-end cleavage and polyadenylation of yeast pre-mRNAs. EMBO J 19: 3778–3787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard J, Zhelkovsky AM, Helmling S, Earnest TN, Moore CL, Bohm A 2000. Structure of yeast poly(A) polymerase alone and in complex with 3′-dATP. Science 289: 1346–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Guarente L 1991. High efficiency transformation of yeast by electroporation. Methods Enzymol 194: 183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan DF, Murthy KG, Prives C, Manley JL 1996. Cell-cycle related regulation of poly(A) polymerase by phosphorylation. Nature 384: 282–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan DF, Murthy KG, Zhao W, Prives C, Manley JL 1998. Inhibition of poly(A) polymerase requires p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation of multiple consensus and non-consensus sites. EMBO J 17: 1053–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller J, Wickens M 2007. Tethered function assays: an adaptable approach to study RNA regulatory proteins. Methods Enzymol 429: 299–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughdrill GW, Ackerman J, Isern NG, Botuyan MV, Arrowsmith C, Wold MS, Lowry DF 2001. The weak interdomain coupling observed in the 70 kDa subunit of human replication protein A is unaffected by ssDNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 3270–3276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughdrill GW, Narayanaswami P, Gilmore SH, Belczyk A, Brown CJ 2007. Dynamic behavior of an intrinsically unstructured linker domain is conserved in the face of negligible amino acid sequence conservation. J Mol Evol 65: 277–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David DC, Layfield R, Serpell L, Narain Y, Goedert M, Spillantini MG 2002. Proteasomal degradation of tau protein. J Neurochem 83: 176–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I 2005. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on energy content. Bioinformatics 21: 3433–3434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink AL 2005. Natively unfolded proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 15: 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes KP, Addepalli B, Hunt AG 2006. An Arabidopsis Fip1 homolog interacts with RNA and provides conceptual links with a number of other polyadenylation factor subunits. J Biol Chem 281: 176–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazy MA, He X, Singh BN, Hampsey M, Moore C 2009. The essential N terminus of the Pta1 scaffold protein is required for snoRNA transcription termination and Ssu72 function but is dispensable for pre-mRNA 3′-end processing. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2296–2307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JH, Cantor CR, Mohr SC, Smith TF 1999. Genomic detection of new yeast pre-mRNA 3′-end-processing signals. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 888–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampsey M 1997. A review of phenotypes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13: 1099–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Moore C 2005. Regulation of yeast mRNA 3′ end processing by phosphorylation. Mol Cell 19: 619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmling S, Zhelkovsky A, Moore CL 2001. Fip1 regulates the activity of poly(A) polymerase through multiple interactions. Mol Cell Biol 21: 2026–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DM, Lipton AS, Isern NG, Daughdrill GW, Lowry DF, Gomes X, Wold MS 1999. Human replication protein A: global fold of the N-terminal RPA-70 domain reveals a basic cleft and flexible C-terminal linker. J Biol NMR 14: 321–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann I, Martin G, Friedlein A, Langen H, Keller W 2004. Human Fip1 is a subunit of CPSF that binds to U-rich RNA elements and stimulates poly(A) polymerase. EMBO J 23: 616–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler MM, Zhelkovsky AM, Skvorak A, Moore CL 1995. Monoclonal antibodies to yeast poly(A) polymerase (PAP) provide evidence for association of PAP with Cleavage Factor I. Biochemistry 34: 1750–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler MM, Zhao J, Moore CL 1996. Purification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cleavage/polyadenylation Factor I. Separation into two components that are required for both cleavage and polyadenylation of mRNA 3′ ends. J Biol Chem 271: 27167–27175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler MM, Henry MF, Shen E, Zhao J, Gross S, Silver PA, Moore CL 1997. Hrp1, a sequence-specific RNA-binding protein that shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, is required for mRNA 3′-end formation in yeast. Genes Dev 11: 2545–2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhrer K, Domdey H 1991. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol 194: 398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel CR, Bai Y, Tong L 2008. Protein factors in pre-mRNA 3′-end processing. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 1099–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinke G, Ezeokonkwo C, Balbo P, Stafford W, Moore C, Bohm A 2008. Structure of yeast poly(A) polymerase in complex with a peptide from Fip1, an intrinsically disordered protein. Biochemistry 47: 6859–6869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SD, Moses K, Jayaraman L, Prives C 1997. Complex formation between p53 and replication protein A inhibits the sequence-specific DNA binding of p53 and is regulated by single-stranded DNA. Mol Cell Biol 17: 2194–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millevoi S, Vagner S 2009. Molecular mechanisms of eukaryotic pre-mRNA 3′ end processing regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 2757–2774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi N, Moore C 2000. Posttranslational phosphorylation and ubiquitination of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase at the S/G(2) stage of the cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol 20: 2794–2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, Butler JS 1992. Conditional defect in mRNA 3′ end processing caused by a mutation in the gene for poly(A) polymerase. Mol Cell Biol 12: 3297–3304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preker PJ, Lingner J, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Keller W 1995. The FIP1 gene encodes a component of a yeast pre-mRNA polyadenylation factor that directly interacts with poly(A) polymerase. Cell 81: 379–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preker PJ, Ohnacker M, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Keller W 1997. A multisubunit 3′ end-processing factor from yeast containing poly(A) polymerase and homologues of the subunits of mammalian cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor. EMBO J 16: 4727–4737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saguez C, Schmid M, Olesen JR, Ghazy MA, Qu X, Poulsen MB, Nasser T, Moore C, Jensen TH 2008. Nuclear mRNA surveillance in THO/sub2 mutants is triggered by inefficient polyadenylation. Mol Cell 31: 91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schärpf M, Sticht H, Schweimer K, Boehm M, Hoffmann S, Rösch P 2000. Antitermination in bacteriophage λ: The structure of the N36 peptide-boxB RNA complex. Eur J Biochem 267: 2397–2408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofaris GK, Layfield R, Spillantini MG 2001. Alpha-synuclein metabolism and aggregation is linked to ubiquitin-independent degradation by the proteasome. FEBS Lett 509: 22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vethantham V, Rao N, Manley JL 2008. Sumoylation regulates multiple aspects of mammalian poly(A) polymerase function. Genes Dev 22: 499–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Kessler M, Helmling S, O'Connor J, Moore C 1999. Pta1, a component of yeast CFII, is required for cleavage and poly(A) addition of mRNA precursor. Mol Cell Biol 19: 7733–7740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhelkovsky AM, Kessler MM, Moore CL 1995. Structure-function relationships in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase. Identification of a novel RNA binding site and a domain that interacts with specificity factor(s). J Biol Chem 270: 26715–26720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]