Abstract

Increased inflammatory response plays a significant role in the vascular pathophysiology in preeclampsia. However, the mechanism for increased inflammatory response in preeclampsia is largely unknown. Interleukin (IL)-6 levels are elevated in women with preeclampsia. IL-6 and its receptors, IL-6R and glycoprotein (gp)130, play a critical role in mediating antiinflammatory response via induction of SOCS-3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling-3). However, IL-6 receptor levels and expressions have not been studied in preeclampsia. In this study, we measured IL-6 and its 2 soluble receptors, soluble IL-6R and soluble gp130, in maternal plasma from normal and preeclamptic pregnant women and found that not only IL-6 but also soluble gp130 levels were significantly higher in preeclamptic women than in normotensive pregnant controls. We further examined IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3 expressions in maternal vessels and leukocytes and found that gp130 and SOCS-3 expressions were downregulated in both vessel endothelium and leukocytes from preeclampsia. Different patterns for IL-6R and gp130 expressions were found. IL-6R expression was also downregulated in leukocytes from preeclampsia. Our results suggest that increased plasma soluble gp130/soluble IL-6R/IL-6 ratio and reduced membrane transsignaling gp130 expression could contribute to decreased SOCS-3 expression and subsequent reduction in SOCS-3 antiinflammatory activity in women with preeclampsia. Thus, reduced gp130 and SOCS-3 expressions may offer, at least in part, a plausible explanation of reduced antiinflammatory protection in the maternal vascular system in preeclampsia.

Keywords: IL-6, gp130, SOCS-3, endothelium, leukocyte, preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a multiple-system disorder unique to human pregnancy that is characterized by maternal hypertension and proteinuria. This pregnancy disorder is a leading cause of preterm delivery. It is also a major cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality in human pregnancy. Although the etiology of preeclampsia is not known, exacerbated inflammatory response is believed to play a significant role in the vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia.1,2 Normal pregnancy is an inflammatory state compared to the nonpregnant condition.1 Endothelial dysfunction,3,4 persistent leukocyte and platelet activations,5,6 and elevated inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrotic factor (TNF)α levels7–9 are all considered hallmarks of increased inflammatory response in this pregnancy disorder.4,10 Increased inflammatory response not only contributes to oxidative stress and vasoconstriction,11,12 but also leads to metabolic disorders such as increased insulin resistance.13 However, little is known about how inflammatory response is being controlled during normal pregnancy and what is responsible for the exacerbated inflammatory response in preeclampsia.

IL-6 is a key regulator of SOCS-3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling-3) induction via binding to its IL-6 receptors on the cell membrane. IL-6 has 2 receptors. One is the cognate IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and the other is the transsignal subunit glycoprotein (gp)130. Gp130-induced transsignaling is critical for the induction of negative cytokine regulator SOCS-3.14,15 Like many membrane receptors, both IL-6R and gp130 have their soluble forms, soluble (s)IL-6R and soluble (s)gp130, and their levels can be detected in the circulation and extracellular fluids. Different actions of the 2 soluble receptors have been identified. Soluble IL-6R has agonistic effects on IL-6,16,17 whereas sgp130 has been demonstrated to be an antagonist to sIL-6R/IL-6.17,18

We recently reported trophoblast IL-6R and SOCS-3 expressions were reduced from preeclamptic placentas,19 suggesting that altered IL-6 receptor and SOCS-3 expressions may account for the increased inflammatory response in preeclamptic placentas. Several studies have shown that maternal IL-6 levels are elevated in women with preeclampsia.8,20 However, sIL-6R and sgp130 levels, and IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3 expressions have never been studied in preeclampsia. Thus, in this study, we measured IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp130 levels in maternal plasma from normal and preeclamptic pregnant women. We also determined IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3 expressions in maternal vessel endothelium and leukocytes from women with normal pregnancy and preeclampsia to test our hypothesis that altered IL-6/gp130 receptor expressions may contribute to increased inflammatory response in the maternal vasculature in preeclampsia.

Methods

Patient Information and Sample Collection

Normal pregnant women were recruited during their routine prenatal visit at the perinatal center or when they were admitted to the labor and delivery unit. Normal pregnancy was defined as pregnancy with normal blood pressure (<140/90 mm Hg), no proteinuria, and absence of obstetric and medical complications. Women diagnosed with preeclampsia were recruited when they were admitted to the labor and delivery unit. Diagnosis of preeclampsia was defined as follows: sustained systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg or a sustained diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg on 2 separate readings; proteinuria measurement of 1+ or more on dipstick, or 24-hour urine protein collection with ≥300 mg in the specimen. Smokers and patients with signs of infection were excluded. To avoid clinical phenotypic differences in preeclamptic patients, patients complicated with HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme and low platelet count), diabetes, and/or renal disease were excluded. This study was approved by Institutional Review Board and conducted at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport. Signed consent was obtained at the time of enrollment. In this study, a total of 136 plasma samples were measured for IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp130 levels (64 from normal and 72 from preeclamptic pregnancies). Maternal subcutaneous fat tissue from 6 normal and 6 preeclamptic pregnant women were collected during cesarean section delivery and used to examine maternal vessel IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3 expressions. Maternal leukocyte samples from 6 normal and 5 preeclamptic pregnant women were used to determine leukocyte protein expressions for IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3.

Assays for IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp130

Maternal venous blood was obtained from 136 pregnant women. Blood sample was collected into sodium heparin tube and plasma was obtained by centrifugation. Plasma samples were aliquot and stored at −80 °C until assay. Plasma IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp130 levels were measured by ELISA. DuoSet ELISA development kits of IL-6 (DY206), sIL-6R (DY227), and sgp130 (DY228) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The assay procedures followed the instructions of the manufacturer. The range of a standard curve was 0.5 to 600 pg/mL for IL-6, 1 to 1000 pg/mL for sIL-6R, and 10 pg/mL to 10 ng/mL for sgp130. All samples were measured in duplicate. Within and between assay variations were less than 6% and 8% for all three ELISA assays, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Fresh subcutaneous tissue was fixed immediately with 10% formalin and then embedded with paraffin. A standard immunohistochemistry staining procedure was performed. Briefly, a series of deparaffinization was done with xylene and ethanol alcohol. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling tissue slides with 0.01 mol/L citric buffer. Hydrogen peroxide was used to quench the endogenous peroxidase activity. After blocking, the sections were incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies specific against human IL-6R (C-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, San Diego, CA), gp130 (H-255) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and SOCS-3 (ab16030) (Abcam Inc, Cambridge, MA) overnight at 4°C. Corresponding biotinylate-conjugated secondary antibodies and ABC staining system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Stained slides were counterstained with Gill’s formulation hematoxylin. Tissue sections stained with isotype IgG were used as controls. All slides stained with the same antibody were processed at the same time. Stained tissue slides were reviewed under an Olympus microscope (Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan), and images were captured by a digital camera and recorded into a microscope-linked PC computer.

Leukocyte Protein Expression

Leukocyte expressions for IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3 were examined by Western blot in 6 normal and 5 preeclamptic samples. Total cellular protein was extracted by lysis of leukocytes with ice cold protein lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris, 0.5% NP40, and 0.5% Triton X-100 with protease inhibitors of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, dithiothreitol, leupeptein, and aprotinin. An aliquot of total cellular protein (10 µg of each sample) was subject for electrophoresis (Bio-Rad) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were then probed with a primary antibody against IL-6R. The same primary antibody was used as the immunostaining study stated above. The bound antibody was visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) detection Kit (Amersham Corp, Arlington Heights, IL). Nitrocellulose membrane was stripped and blocked before it was probed with different primary antibodies, gp130, or SOCS-3. In addition, antibody-binding specificity was also examined by specific blocking peptide for IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3. β-Actin expression was determined and used as the internal control for each sample (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The density was scanned and analyzed by NIH Image 1.16. Relative densities for IL-6R, gp130, and SOCS-3 expressions were normalized by β-actin expression for each sample.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means±SE. Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney test or ANOVA by computer software StatView (Cary, NC). Student–Newman–Keuls test was used as a post hoc test. A probability level of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Clinical Data

The clinical information including maternal age, racial status, gravida, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, gestational age at blood draw and delivery, and delivery mode was obtained by chart review. The clinical characteristics for blood sample studies are shown in Table 1. The demographic data for maternal vessel and leukocyte studies are provided in Table S1A and S1B (see the online Supplement available at http://hyper.ahajournals.org). There were no significant differences in maternal age, racial status, gestational age at blood draw, and BMI between the normal and the preeclamptic groups at <34, 34 to 37, and >37 weeks of gestation (Table 1). Maternal systolic and diastolic blood pressures were significantly higher in the preeclamptic than in the normal groups, P<0.01. The percentage of primigravida and cesarean section deliveries were higher in the preeclamptic than in the normal groups.

Table 1.

Demographic Data of Normal and Preeclamptic Pregnant Women From Whom Blood Samples Were Used in the Study

| ≤34 Weeks | >34–37 weeks | >37 weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Normal (n=19) | PE (n=36) | Normal (n=18) | PE (n=18) | Normal (n=27) | PE (n=18) |

| Maternal Age (yr) | 24±5 (17–34) | 24±7 (15–38) | 22±4 (16 –30) | 23±6 (17– 41) | 22±4 (15–32) | 21±6 (16–41) |

| Racial status (n) | ||||||

| Black | 16 | 22 | 15 | 9 | 20 | 15 |

| White | 3 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 3 |

| Other | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Gestational age (mo) | ||||||

| At blood draw | 32±2 (28–34) | 30±4 (24–34) | 35±1 (34–37) | 36±1 (34–37) | 39±1 (37–41) | 39±1 (37–41) |

| At delivery | 39±2 (37–41) | 30±4 (24–34) | 39±2 (36–41) | 36±1 (34–37) | 40±1 (37–41) | 39±1 (37–41) |

| Primigravida (n) | 8 | 13 | 6 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| BMI (at blood draw) | 30±11 (20–47) | 34±8 (24–55) | 31±6 (24–41) | 36±8 (23–48) | 33±8 (22–57) | 36±12 (22–67) |

| Blood pressure | ||||||

| Systolic | 116±10 (104–136) | 169±15* (140–198) | 125±10 (111–134) | 171±18* (148–203) | 118±13 (92–136) | 168±16* (152–199) |

| Diastolic | 70±7 (56–80) | 104±10* (95–120) | 71±9 (52–84) | 100±11* (91–121) | 70±11 (46–89) | 101±9* (87–118) |

| Delivery Mode | ||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 13 | 10 | 16 | 11 | 20 | 9 |

| Cesarean section | 6 | 26 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 9 |

PE indicates preeclamptic. Data are expressed as means±SD (range).

P<0.01, PE vs normal matched with gestational age group.

Elevated IL-6 and sgp130 Levels and Increased Ratio of sgp130/sIL-6R/IL-6 in Preeclampsia

Maternal plasma IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp130 levels are shown in Table 2. IL-6 levels were significantly higher in women with preeclampsia than in gestational age-matched normal pregnant controls. Maternal sgp130, but not sIL-6R, levels were significantly different between normal and preeclamptic groups, P<0.05, respectively. The ratio of sgp130/sIL-6R/IL-6 was significantly higher in preeclampsia than in gestational age-matched normal pregnant controls: <34 weeks. P<0.01; 34 to 37 weeks, P<0.01; and >37 weeks, P<0.01, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Maternal Plasma Levels for IL-6, Soluble IL-6R, and Soluble Gp130 and Ratios of Soluble Gp130/Soluble IL-6R/IL-6 in Normal and Preeclamptic Pregnant Women

| <34 Weeks | 34–37 Weeks | >37 Weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assays | Normal (n=19) | PE (n=36) | Normal (n=18) | PE (n=18) | Normal (n=27) | PE (n=18) |

| IL-6, pg/mL (range) | 1.80±0.43 (0–6) | 8.92±1.64* (0 –38) | 4.44±1.19 (0 –18) | 12.57±2.78† (2–36) | 4.98±0.81 (0 –16) | 20.76±4.94† (3–57) |

| sIL-6R, ng/mL (range) | 20.09±1.51 (12–36) | 18.86±1.02 (11–32) | 17.39±0.93 (13–25) | 20.21±1.49 (13–36) | 18.10±1.04 (12–34) | 16.73±1.07 (11–24) |

| sgp130, ng/mL (range) | 167.47±9.82 (66–212) | 180.41±7.54 (127–258) | 145.79±7.12 (87–195) | 182.37±12.15* (126–287) | 152.68±5.32 (100–194) | 177.85±9.16* (133–241) |

| sgp130/sIL-6R/IL-6, ratio | 15.52±4.02 | 77.22±14.42† | 39.38±10.81 | 109.88±24.20† | 42.95±6.44 | 193.11±48.72† |

Data are means±SE.

P<0.05,

P<0.01, preeclamptic (PE) vs normal matched with gestational age group.

Differential IL-6R and gp130 Expressions Between Maternal Vessel Endothelium and Leukocytes

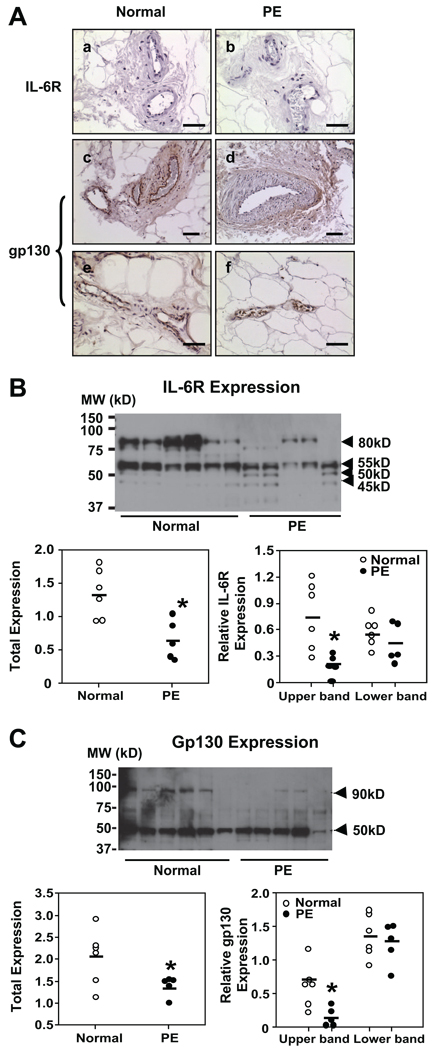

Maternal vessel IL-6R and gp130 immunostaining was examined in subcutaneous tissue sections from 6 normal and 6 preeclamptic pregnancies. The results are shown in Figure 1A. We found that IL-6R expression was not detectable in vessel endothelium, which is consistent with previous published works.21,22 In contrast, intensive gp130 immunostaining was detected in endothelium of vessels from normal pregnant women compared to vessels from preeclampsia (Figure 1A). No staining was seen in sections stained with isotype IgG (data not shown). Gp130 was not expressed in vessel smooth muscle cells (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

IL-6R and gp130 expressions in maternal vessels and leukocytes from normal and preeclamptic pregnant women. A, Immunostaining of IL-6R and gp130 expressions in maternal vessels. a and b, IL-6R. c through f, Gp130. Normal: a, c, and e; preeclampsia (PE): b, d, and f. c and d are arteries; e and f, veins. Gp130, but not IL-6R, immunostaining is detectable in maternal vessels. Gp130 immunostaining is markedly reduced in endothelium of vessels from PE compared to normal pregnant controls. Bar=50 µm for a, b, e, and f; bar=100 µm for c and d. B, Top, Western blot of IL-6R expression in leukocytes. Bottom, Scatter graphs of relative IL-6R expression after normalization with β-actin expression. Four bands are shown with molecular masses of 80, 55, 50, and 45 kDa. Total expression includes all bands; the upper band represents the 80-kDa band, and the lower bands include the 45- to 55-kDa bands, respectively. The densities of total IL-6R and 80-kDa IL-6R were significantly reduced in PE leukocyte samples. *P<0.05. C, Western blot of gp130 expression in leukocytes. Two bands are shown with molecular masses of 90 and 50 kDa. Bottom, Scatter graphs of relative gp130 expression after normalization with β-actin expression. Total expression includes both 90- and 50-kDa bands; the upper band represents the 90-kDa band, and the lower band represents the 50-kDa band. The total gp130 expression and the 90-kDa gp130 expression were significantly reduced in leukocyte samples from PE compared to normal control samples, *P<0.05.

Leukocyte IL-6R and gp130 expressions are shown in Figure 1B and 1C, respectively. For IL-6R expression, there are two intense bands shown in the normal samples, one with molecular mass of 80 kDa and the other with 55 kDa (Figure 1B). In the preeclamptic samples, the 80-kDa band is significantly reduced, P<0.05. Two smaller bands approximately of 45- to 50-kDa (Figure 1B) also showed up in preeclamptic samples. The 80-kDa and 45- to 55-kDa bands could be blocked by IL-6R blocking peptide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-661P, data not shown). Previous studies have shown that the 80-kDa molecular mass is the mature form of IL-6R and 45- to 55-kDa molecular masses are the soluble forms of IL-6R.23,24 Alternative splicing produces 45- to 50-kDa sIL-6R and proteolytic cleavage produces 50- to 55-kDa sIL-6R.23,24 Two bands (≈45 to 50 kDa) were detected in preeclamptic leukocyte samples. These results suggest that increased alternative splicing might occur in leukocytes from women with preeclampsia. Relative protein expressions for IL-6R, total, upper band (80-kDa mature form) and lower bands (45- to 55-kDa splicing and cleavage form) in leukocytes after normalization by β-actin expression are shown in Figure 1B (scatter plots). Reduced IL-6R expression in preeclamptic leukocytes (total preeclampsia [PE] versus normal: 0.65±0.13 versus 1.34±0.15; P<0.05) is mainly attributable to downregulation of the 80 kDa (PE versus normal: 0.20±0.05 versus 0.76±0.16, P<0.05), the mature form, of IL-6R.

At least 3 different forms of soluble gp130 were reported in human serum samples with molecular weights of 50, 90, and 130 kDa.25–27 We detected the 50- and 90-kDa but not 130-kDa forms of sgp130 in leukocyte samples (Figure 1C). Both 50 and 90-kDa bands could be blocked by gp130 blocking peptide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-656P, data not shown). These results indicate that leukocytes express soluble form of gp130. Leukocyte gp130 expression is reduced in preeclamptic compared to normal pregnancies (total PE versus normal: 1.38±0.10 versus 2.05±0.25, P<0.05) and the reduced 90-kDa molecular mass (PE versus normal: 0.14±0.07 versus 0.70±0.16, P<0.05) accounts for the total gp130 reduction in leukocytes from preeclampsia, Figure 1C (scatter plots).

Downregulation of SOCS-3 Expression in Maternal Vessel Endothelium and in Leukocytes From Preeclampsia

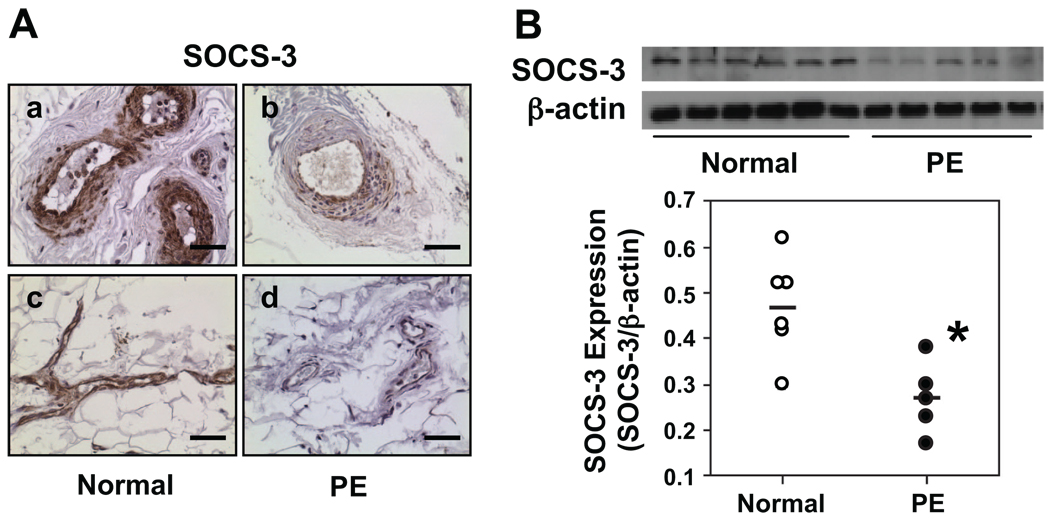

Because the IL-6 receptors IL-6R and gp130 play key roles in the induction of SOCS-3 expression, we examined SOCS-3 expression in maternal vessels and leukocytes from normal and preeclamptic pregnant women. Results are shown in Figure 2. We found intensive SOCS-3 staining in vessel endothelium both in arteries and veins in tissue sections from normal pregnant women. The smooth muscle layer also shows intensive SOCS-3 staining. In contrast, SOCS-3 expression was markedly reduced in vessel endothelium both in arteries and veins in tissues from women with preeclampsia. SOCS-3 expression was also reduced in smooth muscle layers of vessels from preeclampsia (Figure 2A). No staining was seen in sections stained with isotype IgG (data not shown). Consistent with maternal vessels, relative SOCS-3 expression was also reduced in leukocytes from preeclampsia (n=5) compared to those from normal (n=6) pregnant women, 0.27±0.04 versus 0.47±0.05, P<0.05 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

SOCS-3 expression in maternal vessels and leukocytes from normal and preeclamptic pregnant women. A, Immunostaining of SOCS-3 in maternal vessels. Normal: a and c; preeclampsia (PE): b and d. a and b are arteries; c and d are veins. SOCS-3 immunostaining is markedly reduced in endothelium and underlying smooth muscle cells in vessels from PE compared to those from normal pregnant women. Bar=50 µm. B, SOCS-3 expression in leukocytes. Scatter graph shows relative SOCS-3 expression after normalization with β-actin expression. SOCS-3 expression was significantly downregulated in leukocytes from PE (n=5) compared to those from normal (n=6) pregnant controls. *P<0.05, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we found that: (1) maternal IL-6 and sgp130, but not sIL-6R, levels were increased in women with preeclampsia compared to normal pregnant controls; (2) IL-6R expression was downregulated in leukocytes from preeclampsia; and (3) gp130 expression was downregulated in both vessel endothelium and leukocytes from preeclampsia. These observations indicate that IL-6 and its receptor regulation are altered in women with preeclampsia compared to normal pregnant controls.

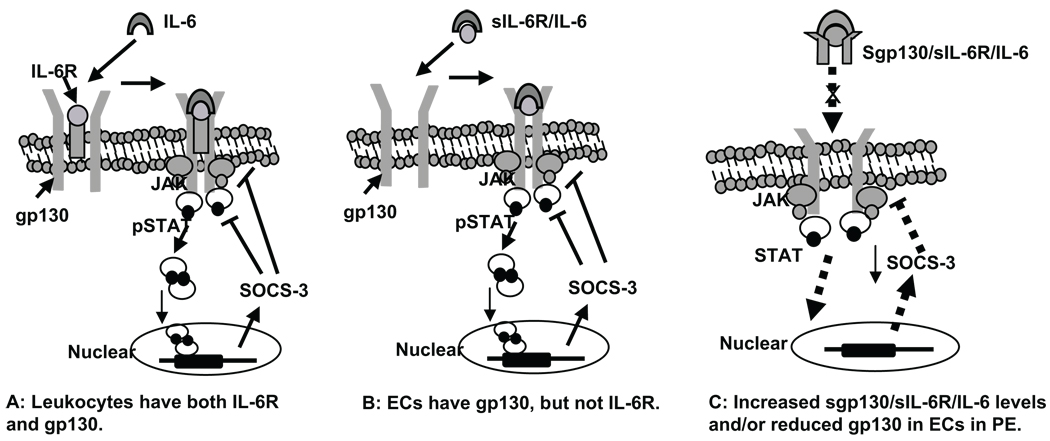

IL-6 is an intriguing cytokine and studies have shown that IL-6 acts as both a proinflammatory and an antiinflammatory cytokine. It signals through a cell surface type I cytokine receptor complex consisting of the ligand-binding IL-6Rα chain and the signal-transducing component gp130 (IL-6Rβ) chain. IL-6 binds to IL-6R and forms a ligand receptor complex, IL-6/IL-6R, which then induces receptor dimerization and Janus kinases (JAKs) phosphorylation of the signal transducing subunit gp130. Phosphorylated JAK further induces STAT3 phosphorylation, and dimeric STAT3 migrates to the nucleus, where it recognizes specific elements in the promoter of SOCS-3 gene and induces SOCS-3 expression. Once induced, SOCS-3 acts as a negative feedback regulator on the JAK-STAT pathway to temper signal transduction, attenuate cytokine-activated signaling, and suppress cytokine generation and cytokine-induced inflammatory responses.28,29 Actually, all members of the IL-6 family cytokines including IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor, oncostatin M, and ciliary neurotrophic factor use gp130 as a common signal transducer after binding to their specific receptors. Thus, gp130 is considered critical in regulation of IL-6 cytokine family induced cellular response. Soluble IL-6R and sgp130 are biologically active, but exert opposite functions.16–18 In the extracellular compartment, sIL-6R acts as an agonist to IL-6 by forming sIL-6R/IL-6 complex, which can bind to membrane gp130 and initiate the signal transduction. The sIL-6R/IL-6 complex plays a major role in initiating the signal transduction in cells without IL-6R, such as endothelial cells. In contrast, sgp130 is considered an antagonist to the sIL-6R/IL-6 complex. Soluble gp130 binds to sIL-6R/IL-6 complex and forms a double receptor complex, sgp130/sIL-6R/IL-6, which is no longer able to bind to membrane gp130. As a result, sgp130 prevents sIL-6R/IL-6 from binding to the membrane receptor, and consequently affects SOCS-3 induction. The proposed mechanisms in which IL-6 induced SOCS-3 induction are presented in Figure 3A and 3B in cells with or without IL-6R.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanisms of IL-6 and its receptor signaling pathway in SOCS-3 induction in cells with or without IL-6R. A, Cells have both IL-6R and gp130 receptors such as in leukocytes. IL-6 binds to IL-6R on the cell membrane and forms a receptor complex with gp130. The binding process induces receptor dimerization and Janus kinase (JAK) phosphorylation of the signal transducing subunit gp130. Phosphorylated JAK further induces STAT3 phosphorylation, and dimeric STAT3 migrates to the nucleus, where it recognizes specific elements in the promoter of SOCS-3 gene and induces SOCS-3 expression. Once induced, SOCS-3 acts back on the JAK/STAT pathway to inhibit signal transduction, attenuate cytokine-activated signal transduction pathway, and suppress cytokine generation and cytokine-induced inflammatory responses. B, Cells have gp130, but not IL-6R, such as in endothelial cells. In the extracellular compartment such as in the blood circulation, IL-6 cannot directly bind to gp130 on the cell membrane. Instead, IL-6 binds sIL-6R and forms receptor/ligand complex, sIL-6R/IL-6. The complex could then bind to gp130 on the cell membrane and induce gp130 phosphorylation and SOCS-3 induction. Therefore, sIL-6R is considered as an agonist to IL-6 and plays a critical role in IL-6–induced gp130 activation, and the integrity of the cell membrane gp130 receptor is critical for signal transduction and SOCS-3 induction. C, Proposed mechanism of reduced antiinflammatory activity in vascular endothelial cells in preeclampsia (PE): a condition of increased sgp130 levels, increased ratio of sgp130/sIL-6R/IL-6, and decreased membrane gp130 receptor expression in cells without IL-6R. In this condition, sgp130 binds to sIL-6R/IL-6 and forms a double-receptor complex, sgp130/sIL-6R/IL-6, which prevents sIL-6R/IL-6 binding to membrane receptor gp130. Reduced membrane gp130 receptor expression then leads to less receptor binding activity. As a result, the JAK/STAT pathway signaling and SOCS-3 induction would be significantly impaired. Consequently, endogenous antiinflammatory SOCS-3 activity would be reduced, which possibly is the case of vascular endothelial cells in preeclampsia.

Study has shown that gp130 is expressed in almost all cells, whereas IL-6R expression is found only in few cell types.17 We observed that IL-6R was strongly expressed in leukocytes, but undetectable in maternal vessel endothelium in both normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. In contrast, gp130 is intensively expressed in endothelium of vessels from normal pregnant women, but reduced gp130 expression was observed in vessel endothelium in preeclampsia. Leukocytes express both IL-6R and gp130, which is consistent with previous published work.22,30,31 However, both IL-6R and gp130 expressions were significantly reduced in leukocytes from women with preeclampsia. The different patterns of IL-6R and gp130 expressions between vessel endothelium and circulating leukocytes indicate that a distinct IL-6 receptor signaling regulation does exist between endothelial cells and leukocytes.

Both soluble forms of IL-6 receptors, sIL-6R and sgp130, were detected in leukocyte samples. For IL-6R, it seems that increased alternative splicing occurs in leukocytes from preeclampsia because alternative splicing produces 45- to 50-kDa sIL-6R.23 For gp130, the mature form (130 kDa) of gp130 was not shown in leukocyte samples, instead two truncated (soluble) forms, 50 and 90 kDa, were detected. The 90-kDa form was significantly reduced in preeclamptic samples. Previous studies have shown that the 50-kDa soluble form is produced by alternative splicing mRNA,26 and can be detected in human plasma and urine samples.27 The 50-kDa sgp130 probably contains only the hemopoietin domain.27 The reason for increased maternal sgp130 levels in preeclampsia is not known, but decreased gp130 expression in both vessel endothelium and leukocytes clearly indicate that the integrity of gp130 is impaired in endothelial cells and leukocytes in preeclampsia. Chalaris et al reported that increased sIL-6R shedding was associated with reduced cellular IL-6R expression in Ba/F3 cells, a murine pro-B cell line.31 The reason for reduced gp130 expression in preeclamptic leukocytes is not known, but increased plasma sgp130 levels suggest that reduced cellular receptor expressions could be as a result from increased soluble receptor shedding in preeclampsia.

Reduced SOCS-3 expression found in both maternal vessel endotelium and leukocytes in preeclampsia is another significant finding in our study. SOCS-3 belongs to a family of molecules involved in inhibiting the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. SOCS-3 is an antiinflammatory mediator28,32,33 and plays a critical role in inhibiting inflammatory response via negative regulation of several cytokine pathways, particularly the IL-6 induced receptor-associated JAK/STAT pathway.32,34 The finding of reduced SOCS-3 expression in maternal vasculature in preeclampsia supports the concept of reduced antiinflammatory activity and increased inflammatory response in women with preeclampsia.

Increased inflammatory response and adiposity are related to each other. Women with obesity or insulin resistance have a higher incidence of developing preeclampsia during pregnancy. However, in our study population, as shown in Table 1 (subjects for maternal plasma measurement), Table S1A (subjects for maternal vessel IL-6R, gp130 and SOCS-3 staining), and Table S1B (subjects for maternal leukocyte IL-6R, gp130 and SOCS-3 expressions), difference in BMI was only seen in Table S1B leukocyte studies, which only limited subjects were involved. It seems that increased maternal IL-6 and sgp130 levels might not be directly related to the maternal BMI, at least in our study population.

It has been well accepted that placenta-derived factors play a significant role in inducing vessel endothelium and leukocyte activation/dysfunction2,35–37; however, the mechanism of increased inflammatory response in preeclampsia is not fully understood. Little is known about how the cellular endogenous defense mechanism functions in the vascular system against inflammatory stimulus challenge. Our findings of downregulation of SOCS-3 expression in both vessel endothelium and leukocytes suggest that antiinflammatory activity/function of gp130/STAT/SOCS-3 signaling pathway is impaired in the maternal vascular system in preeclampsia, which, at least in part, offers a plausible explanation of increased inflammatory response in this pregnancy disorder.

Perspective

Although we did not directly examine the responses of leukocytes and endothelial cells to IL-6 stimulation and SOCS-3 induction, our results do suggest that different regulatory mechanisms exist in response to IL-6 between endothelial cells and leukocytes in the systemic vasculature. In the case of endothelial cells, because they are lacking IL-6R,21,22 soluble receptor–ligand complex sIL-6R/IL-6 could be the active form that binds to membrane gp130 and initiates gp130/STAT signaling and SOCS-3 induction, as proposed in Figure 3B, whereas in the case of leukocytes, circulating IL-6 can directly act on leukocytes and initiate the signaling cascade, because leukocytes express IL-6R, as proposed in Figure 3A. Therefore, it is logical to expect that in preeclampsia, elevated levels of IL-6 and sgp130 and increased ratio of sgp130/sIL-6R/IL-6 combined with reduced gp130 expression could result in less SOCS-3 induction and, subsequently, aberrant antiinflammatory activity/function in leukocytes and vessel endothelium, as proposed in Figure 3C. Further study of sIL-6R and sgp130 function and status of these soluble receptors, as well as SOCS-3 regulation, are warrant and would provide insight into mechanisms at the cellular and molecular levels as to how inflammatory response is being controlled during normal pregnancy and what failed mechanisms occur that lead to increased inflammatory response in preeclampsia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant HD36822 and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL65997).

Footnotes

Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at http://www.lww.com/reprints

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Redman CWG, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:499–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borzychowski AM, Sargent IL, Redman CW. Inflammation and preeclampsia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Gu Y, Zhang Y, Lewis DF. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia: decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression is associated with increased cell permeability in endothelial cells from preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:817–824. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rodgers GM, Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK. Preeclampsia: An endothelial cell disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1200–1204. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konijnenberg A, Stokkers EW, van der Post JA, Schaap MC, Boer K, Bleker OP, Sturk A. Extensive platelet activation in preeclampsia compared with normal pregnancy: enhanced expression of cell adhesion molecules. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:461–469. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryu S, Huppmann AR, Sambangi N, Takacs P, Kauma SW. Increased leukocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium in preeclampsia is inhibited by antioxidants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:400.e1–400.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vince GS, Starkey PM, Austgulen R, Kwiatkowski D, Redman CWG. Interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor and soluble tumour necrosis factor receptors in women with pre-eclampsia. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:20–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupferminc MJ, Peaceman AM, Aderka D, Wallach D, Socol ML. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors and interleukin-6 levels in patients with severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:420–427. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakabayashi M, Sakura M, Takeda Y, Sato K. Elevated IL-6 in midtrimester amniotic fluid is involved with the onset of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1998;39:329–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker GA, Sibai BM. Etiology and pathogenesis of preeclampsia: current concepts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1359–1375. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meziani F, Tesse A, David E, Martinez MC, Wangesteen R, Schneider F, Andriantsitohaina R. Shed membrane particles from preeclamptic women generate vascular wall inflammation and blunt vascular contractility. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1473–1483. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah TJ, Walsh SW. Activation of NF-kappaB and expression of COX-2 in association with neutrophil infiltration in systemic vascular tissue of women with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:48.e41–48.e48. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rademacher TW, Gumaa K, Scioscia M. Preeclampsia, insulin signaling and immunological dysfunction: a fetal, maternal or placental disorder? J Reprod Immunol. 2007;76:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taga T, Kishimoto T. Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:797–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones SA, Richards PJ, Scheller J, Rose-John S. IL-6 transsignaling: the in vivo consequences. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:241–253. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaillard J, Pugnière M, Tresca J, Mani J, Klein B, Brochier J. Interleukin-6 receptor signaling. II. Bio-availability of interleukin-6 in serum. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1999;10:337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knüpfer H, Preiss R. sIL-6R: more than an agonist? Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:87–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jostock T, Müllberg J, Ozbek S, Atreya R, Blinn G, Voltz N, Fischer M, Neurath MF, Rose-John S. Soluble gp130 is the natural inhibitor of soluble interleukin-6 receptor transsignaling responses. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:160–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao S, Gu Y, Dong Q, Fan R, Wang Y. Altered IL-6 receptor, IL-6R and gp130, production and expression and decreased SOCS-3 expression in placentas from women with preeclampsia. Placenta. 2008;29:1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opsjon SL, Novick D, Wathen NC, Cope AP, Wallach D, Aderka D. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors and soluble interleukin-6 receptor in fetal and maternal sera, coelomic and amniotic fluids in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies. J Reprod Immunol. 1995;29:119–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(95)00940-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romano M, Sironi M, Toniatti C, Polentarutti N, Fruscella P, Ghezzi P, Faggioni R, Luini W, van Hinsbergh V, Sozzani S, Bussolino F, Poli V, Ciliberto G, Mantovani A. Role of IL-6 and its soluble receptor in induction of chemokines and leukocyte recruitment. Immunity. 1997;6:315–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modur V, Li Y, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM. Retrograde inflammatory signaling from neutrophils to endothelial cells by soluble interleukin-6 receptor alpha. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2752–2756. doi: 10.1172/JCI119821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horiuchi S, Koyanagi Y, Zhou Y, Miyamoto H, Tanaka Y, Waki M, Matsumoto A, Yamamoto M, Yamamoto N. Soluble interleukin-6 receptors released from T cell or granulocyte/macrophage cell lines and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells are generated through an alternative splicing mechanism. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1945–1948. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horiuchi S, Ampofo W, Koyanagi Y, Yamashita A, Waki M, Matsumoto A, Yamamoto M, Yamamoto N. High-level production of alternatively spliced soluble interleukin-6 receptor in serum of patients with adult T-cell leukaemia/HTLV-I-associated myelopathy. Immunology. 1998;95:360–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narazaki M, Yasukawa K, Saito T, Ohsugi Y, Fukui H, Koishihara Y, Yancopoulos GD, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Soluble forms of the interleukin-6 signal-transducing receptor component gp130 in human serum possessing a potential to inhibit signals through membrane-anchored gp130. Blood. 1993;82:1120–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka M, Kishimura M, Ozaki S, Osakada F, Hashimoto H, Okubo M, Murakami M, Nakao K. Cloning of novel soluble gp130 and detection of its neutralizing autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:137–144. doi: 10.1172/JCI7479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang JG, Zhang Y, Owczarek CM, Ward LD, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ, Yasukawa K, Nicola NA. Identification and characterization of two distinct truncated forms of gp130 and a soluble form of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor alpha-chain in normal human urine and plasma. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10798–10805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, Wormald S, Willson TA, Stanley EG, Robb L, Greenhalgh CJ, Förster I, Clausen BE, Nicola NA, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Roberts AW, Alexander WS. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:540–545. doi: 10.1038/ni931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diehl S, Rincón M. The two faces of IL-6 on Th1/Th2 differentiation. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLoughlin RM, Hurst SM, Nowell MA, Harris DA, Horiuchi S, Morgan LW, Wilkinson TS, Yamamoto N, Topley N, Jones SA. Differential regulation of neutrophil-activating chemokines by IL-6 and its soluble receptor isoforms. J Immunol. 2004;172:5676–5683. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chalaris A, Rabe B, Paliga K, Lange H, Laskay T, Fielding CA, Jones SA, Rose-John S, Scheller J. Apoptosis is a natural stimulus of IL6R shedding and contributes to the proinflammatory trans-signaling function of neutrophils. Blood. 2007;110:1748–1755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-067918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krebs DL, Hilton DJ. SOCS proteins: negative regulators of cytokine signaling. Stem Cells. 2001;19:378–387. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-5-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qasimi P, Ming-Lum A, Ghanipour A, Ong CJ, Cox ME, Ihle J, Cacalano N, Yoshimura A, Mui AL. Divergent mechanisms utilized by SOCS3 to mediate interleukin-10 inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha and nitric oxide production by macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6316–6324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexander WS, Hilton DJ. The role of suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins in regulation of the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:503–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.091003.090312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cockell AP, Learmont JG, Smarason AK, Redman CWG, Sargent IL, Poston L. Human placental syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membranes impair maternal vascular endothelial function. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:235–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Adair CD, Weeks JW, Lewis DF, Alexander JS. Increased neutrophil-endothelial adhesion induced by placental factors is mediated by platelet-activating factor in preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1999;6:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(99)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Gu Y, Philibert L, Lucas MJ. Neutrophil activation induced by placental factors in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies in vitro. Placenta. 2001;22:560–565. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.