Abstract

Objective We examined whether neonatal risks and maternal scaffolding (i.e., task changes and flexibility) during a 16-month post-term play interaction moderated the association between socioeconomic status (SES), visual-spatial processing and emerging working memory assessed at 24 months post-term among 75 toddlers born preterm or low birth weight. Method SES and neonatal risk data were collected at hospital discharge and mother–child play interactions were observed at 16-month post-term. General cognitive abilities, verbal/nonverbal working memory and visual-spatial processing data were collected at 24 months. Results Neonatal risks did not moderate the associations between SES and 24-month outcomes. However, lower mother-initiated task changes were related to better 24-month visual-spatial processing among children living in higher SES homes. Mothers’ flexible responses to child initiated task changes similarly moderated the impact of SES on 24-month visual-spatial processing. Conclusion Our results suggest that mothers’ play behaviors differentially relate to child outcomes depending on household SES.

Keywords: low birth weight, neuropsychology, parenting, prematurity

Introduction

Although technological advances now allow more preterm or low birth weight infants to survive their neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) stays, there has been comparatively little progress in reducing the rates of cognitive, behavioral, and physical impairments associated with preterm (<37 weeks gestation) or low birth weight (<2,500 g) (PT LBW) births (Bhutta, Cleves, Casey, Cradock, & Anand, 2002). Anderson and colleagues (2003), for example, observed that 8-year-old children born weighing less than 1,000 g or who were born prior to 28 weeks gestation obtained significantly lower visual-spatial and working memory compared to peers born weighing more than 2,499 g. Children born PT LBW also exhibit deficits in visual-spatial processing that are related to later difficulties in math (Assel, Landry, Swank, Smith, & Steelman, 2003).

Children born PT LBW into homes characterized by low socioeconomic status (SES) are especially at risk for developmental problems (Bendersky & Lewis, 1994; Dieterich, Hebert, Landry, Swank, & Smith, 2004; McGrath & Sullivan, 2003). But there is relatively little research on the underlying proximal processes that link characteristics of the home environment, like maternal education and household income, to specific cognitive outcomes (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). In this analysis, we investigated the extent to which mother-toddler interaction quality during a 16-month post-term play interaction moderated the impact of early SES on visual-spatial processing and emerging working memory assessed at 24 months post-term in toddlers born PT LBW. We also examined the extent to which neonatal risks moderated SES influences on children’s 24-month visual-spatial processing and working memory outcomes.

Associations Between SES, Maternal Scaffolding Behaviors, and Neurocognitive Outcomes

Cognitive abilities emerge over time, in part, through interactions with more competent individuals who support the child as he or she attempts to accomplish tasks that would otherwise be outside his or her range of ability (Vygotsky, 1978; Wertsch, 1979). Mothers scaffold their young children’s development through explicit verbal direction and verbal and nonverbal behaviors that sustain children’s focus on things of interest (Dunham & Dunham, 1995; Landry, Garner, Swank, & Baldwin, 1996).

In a study of children born preterm and at term, Landry and colleagues (2000) identified positive associations between mothers’ efforts to direct and maintain their children’s attention and later cognitive and social skills. They concluded that maintaining behaviors (i.e., choice providing strategies) scaffolding 2- and 3.5-year-old childrens developing attentional and cognitive capacities because they did not require the children to shift attention. Maintaining behaviors allowed the children to participate in learning activities and gradually develop independent problem solving skills over time. In contrast, maternal directiveness (i.e., provision of structured information, but little choice) supported cognitive development when children were 2 years old, but not when children were older. Their findings suggest that continued directiveness in early childhood (ages 3.5 and 4.5 years) may reflect either less cognitive competence or greater need for structure on the part of the child (Landry, Smith, Swank, & Miller-Loncar, 2000).

Prior research indicates that play interactions provide scaffolding opportunities that may be particularly important for children experiencing neonatal risks such as prematurity. However, early child characteristics are thought to interact with contextual factors to impact later developmental competencies (Aylward, 1992; Sameroff & Chandler, 1975). For example, living in low-income homes creates a dual risk for children born PT LBW, significantly increasing the likelihood of negative developmental outcomes (e.g., Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994). Less is known about the extent to which child characteristics, such as neonatal risks, contribute to individual differences in the neurocognitive outcomes of children experiencing low SES.

Similarly, little is known about whether or how maternal scaffolding behaviors and SES interact. The Landry et al. (2000) sample was composed of full-term and preterm children, and they did not consider SES. Moreover, although Dilworth-Bart, Poehlmann, Hilgendorf, Miller, and Lambert (2010) concluded that attention and emotion scaffolding mediated an association between SES and the 24-month verbal working memory of PT LBW children using data from the same subsample reported herein, their study fell short of investigating whether specific directive and/or maintaining behaviors moderated associations between SES and neurocognitive outcomes. Nevertheless, cumulative and multiple risk research indicates that the developmental context is especially influential for children experiencing the highest SES risks (e.g., Dilworth-Bart, Khushid, & Vandell, 2007; Sameroff & Seifer, 1983), and family processes have been observed to promote positive neurodevelopmental and behavioral outcomes even in the context of SES-risk (e.g., Calkins, Blandon, Williford, & Keane, 2007; Jaffee, 2007).

The Current Study

We extended previous research by examining maternal play behaviors and neonatal risk as possible moderators of the impact of socioeconomic risk on neurocognitive outcomes in a sample of PT LBW toddlers. We tested two study hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that neonatal risk would moderate the association between socioeconomic risk and 24-month verbal and nonverbal visual-spatial processing and working memory (Hypothesis 1). Consistent with the literature on cumulative and multiple risks, children with higher neonatal risks who also lived in lower SES homes were expected to have the lowest neurocognitive scores because they experienced dual risk (Belsky, 2005; Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994). Conversely, children from lower SES homes with lower neonatal risks were expected to show higher neurocognitive scores. This hypothesis differs somewhat from seminal work indicating a moderating role for SES on child outcomes (i.e., Sameroff & Chandler, 1975) in that we propose neonatal risks as a moderator of SES effects. Our hypothesis is based on research and theory suggesting that some children are differentially susceptible to contextual influences due to their underlying biologic characteristics (e.g., Belsky, 2005). Rather than testing the full differential susceptibility model, however, we focused on testing the vulnerability or dual risk part of the model.

We also hypothesized that mothers’ behaviors during a 16-month post-term interaction would moderate associations between SES and verbal and nonverbal working memory and visual spatial processing assessed at 24 months post-term (Hypothesis 2). Extending Landry et al.’s (2000) finding of positive associations between directiveness and cognitive outcomes at 2 years of age, we expected that more directive behaviors during the 16-month play interaction (i.e., mother-initiated task changes) would moderate the association between SES and 24-month outcome scores (Hypothesis 2a). We further expected that behaviors consistent with maintaining child attention at 16 months (i.e., mothers’ flexibility in response to child initiated task changes) would moderate an association between socioeconomic risk and 24-month working memory and visual-spatial processing (Hypothesis 2b). We expected that the higher SES-risk children’s outcome scores would approximate those of lower risk children if their mothers engaged in more directive and maintaining behaviors. Given our previous findings that attention and emotion scaffolding mediated associated between SES and verbal working memory (Dilworth-Bart et al., 2010), we also explored whether mother-initiated task changes and/or maternal flexibility similarly mediated associations between SES and neurocognitive outcomes.

Methods

Sample

The study included 75 infant–mother dyads derived from a larger longitudinal study (Poehlman, Schwichtenberg, Bolt, & Dilworth-Bart, 2009) focusing on the development of self-regulation in infants born preterm or low birth weight (N = 181). The larger study investigates early social and physiological processes involved in the development of self-regulation and its relation to infant–mother attachment and cognitive development in high risk infants who vary in their level of neonatal medical risk. This longitudinal study followed infants from hospital discharge until they were 2 years (corrected for gestational age) and involved data collected from children and families using multiple methods in multiple contexts.

Participants were recruited into the larger study using five criteria: (a) infants were born less than 36 weeks gestation OR weighing less than 2,500 g, (b) infants had no known congenital malformations or prenatal drug exposures, (c) mothers were at least 17 years old, (d) mothers could read English, and (e) mothers identified themselves as the infant’s primary caregiver. Families were enrolled in the study through three hospitals in southeastern Wisconsin, following Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Wisconsin and each of the hospitals. Consent was obtained from the mothers at hospital discharge. If mothers gave birth to multiples, one child was randomly selected to participate in the study. The 181 (97%) study participants came from a total of 186 who signed consent forms at hospital discharge. We are unable to calculate a participation rates or provide descriptive information about mothers who chose not participate in the study because hospitals would not allow us to be “first contact” with eligible families nor would they provide demographic information about families who chose not to participate.

Mother, child, and dyadic data were collected at hospital discharge as well as at 4, 9, 16, and 24 months post-term. Although there was 14% attrition between the hospital discharge and the 24-month assessment, there were no differences in neonatal risk between infants who remained in the study and those whose families discontinued [multivariate F(6,172) = 1.36, p = .23]. However, mothers lost to attrition were younger [F(1,173) = 5.51, p < .05], had less education [F(1, 173) = 5.88, p < .05], and a marginally higher sociodemographic risk index score [F(1,173) = 3.23, p < .08] [multivariate F(7,167) = 1.90, p < .08]. Single mothers [χ2(1) = 4.68, p < .05] and mothers who were not White [χ2(1) = 5.57, p < .05] were also more likely to be lost to attrition.

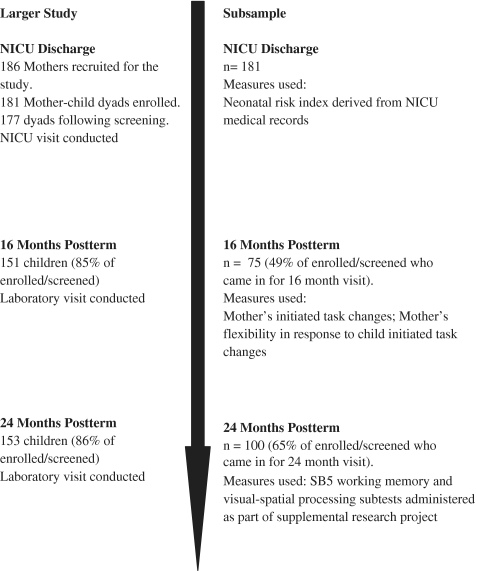

Subsample Selection

The subsample of 75 infant–parent dyads analyzed in this study were dyads who completed both the 16- and 24-month assessments of the larger longitudinal study. The working memory and visual-spatial processing tasks were added to the end of a larger research battery midway through the 24-month assessment wave as part of a supplemental research project (added to the end of the protocol so the other portions remained unchanged). Of the 153 children who completed the 24-month assessment, 100 were administered the working memory and visual-spatial processing tasks. Of the 100 children who completed the 24-month working memory and visual-spatial processing tasks, 75 also participated in the 16-month post-term play interaction, thereby limiting the size of our subsample to 75 dyads. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study design as well as the attrition at each time point.

Figure 1.

Overview of study design and attrition at NICU discharge, 16- and 24-month post-term.

Mean gestational age for this subset was 31.61 weeks (SD = 3.15; range = 25–36.43 weeks), and mean birth weight was 1,734.09 g (SD = 580.40; range = 680–3,328 g). Of the 75 participants, 33 (44%) were male. The subsample was predominantly White (n = 58, 77.3%). The remainder of the children were African-American (n = 8, 10.7%), Latino (n = 1; 1.3%), or Mulitracial/Other (n = 8; 10.7%). Average household income for the subsample was $60,939.24 (SD = $40,407.11; range = $0–200,000), and the mean maternal education was 14.55 years (SD = 2.63; range = 8–21 years). The subsample did not differ from the remainder of the full sample in terms of maternal education, t(179) = –95, p = .34, household income, t(178) = –.20, p = .84, gestational age, t(179) = –.86, p = .39, or birth weight, t(179) = .39, p = .69.

Measures

General Cognitive Abilities

Children’s general cognitive abilities were estimated with the Abbreviated Battery IQ scale (ABIQ) from the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, 5th edition (SB5; Roid, 2003a) and used as a control variable in regression analyses. ABIQ scores are derived from the Object Series/Matrices and Verbal Knowledge routing subtests of the SB5. The Object Series/Matrices routing items provide an estimate of respondents’ cognitive flexibility, fluid reasoning, inductive and deductive reasoning, as well as their abilities to sequence and concentrate (α = .81; Roid, 2003b). The Verbal Knowledge routing subtest items assess word knowledge, verbal fluency, and conceptual thinking (α = .93; Roid, 2003b). The total ABIQ score has a coefficient α of .90, and the correlation with the full scale IQ for 2- to 5-year-olds was .81 (Roid, 2003b). The ABIQ scale also correlates with the WISC-III (r = .69; Roid, 2003b). The routing subtest allows the SB5 to be adapted to participants’ function levels and is a self-contained task that does not use items from the 10 SB5 subscales (Roid, 2003b). Use of the ABIQ along with the working memory and visual-spatial processing subscales was deemed appropriate because they rely on different items (Roid, 2003b). The SB5 subtests were administered by trained graduate student research assistants who were supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist.

SES

Years of maternal education and household income at the child’s birth for the subsample were standardized and summed to create the socioeconomic risk variable. Standardized scores were then reversed so that higher scores indicated higher risk. Chronbach’s α for this risk index was .70 for the subsample analyzed in the current study.

Neonatal Risk

Infant medical records from the child’s NICU stay provided the data for our neonatal health risk variable. Infant birth weight and gestational age were highly correlated in the subsample (r = .87, p < .001), so we standardized and combined them to create a prematurity composite. We then reverse scored the composite so that higher scores reflected more prematurity. We then created a neonatal health risk index combining the reversed prematurity composite with 11 other risk variables (scored as 1 if the risk was present): grades I–III intraventricular hemorrhage, diagnosis of apnea, respiratory distress syndrome, chronic lung disease, gastroesophageal reflux, multiple birth, whether infants had 5-min Apgar scores of less than 6, spent more than 30 days in the NICU, were discharged with an apnea monitor, and whether they were still receiving oxygen at hospital discharge. Chronbach’s α for the subsample examined in the current study was .72.

Maternal Behavior During Play

Mother–child interactions during an approximately 15-min free play interaction at 16-months post-term were coded for the number of mother-initiated task changes and mothers’ flexibility. Three 2-member coding teams coded the video-taped interaction. Four 2-min interactions were coded for each tape for a total of eight coded minutes of play. Segments corresponding to min 0–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–11 were coded for each tape. Scores were summed across the four segments. Coding in 2-min intervals allowed us to gather data about interaction behaviors over an extended time period without fatiguing raters by having them code the full play interaction. We were also unable to code the full 15-min interaction for several dyads because the interactions concluded early. We stopped coding at the end of the 11th minute of taping because that was the earliest end time for an interaction in our subsample. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for nine (12.5%) of the tapes. The conservative Fleiss’ κ coefficient was used to establish reliability among the three coding groups for each of the four segments (Fleiss, 1971).

The mother-initiated task changes code is conceptually similar to directiveness as defined by Landry and colleagues (2000), in that mothers’ tasks changes reduce the child’s ability to choose activities during play. The mother-initiated task changes code was used to record the total number of times mothers chose a new activity or toy with which to play. Possible scores for this item ranged from 1 task change to 5 or more changes. Inter-rater reliability (κ) was .53 for segment 1, .64 for segment 2, .70 for segment 3, and .64 for segment 4.

The mother flexibility code is conceptually similar to the Landry et al. (2000) maintaining code, in that mothers high in flexibility followed the child’s interests during play. This item was used to record mother’s responsiveness to child-initiated task changes, ranging from 1 (does not follow child’s lead during play) to 5 (follows child’s lead and transitions to new activity with ease). Kappa reliability .59 for segment 1, .35 for segment 2, .48 for segment 3 and .73 for segment 4.

Visual-Spatial Processing

Visual-spatial processing skills were assessed using the verbal and nonverbal visual-spatial processing subtests of the SB5 (Roid, 2003a). The nonverbal subtests include increasingly difficult form-board and pattern activities. The verbal subtests assess knowledge of spatial concepts using position and direction activities. Reliability coefficients for the nonverbal and verbal subtests are .87 and .82, respectively, for the normative sample (Roid, 2003b). The correlation between SB5 visual-spatial processing and the abstract reasoning subscale of the SB4 is .69 (Roid, 2003b).

Working Memory

Working memory was assessed using the standardized and normed verbal working memory (VWM) and nonverbal working memory (NVWM) subtests of the SB5 (Roid, 2003a). The NVWM subtest includes increasingly difficult items ranging from finding a hidden object to repeating a block tapping sequence. The alpha reliability coefficient for this subtest is .89 for the normative sample (Roid, 2003b). The VWM subtest includes sentence memory items in levels 2 and 3, followed by “last word” items in levels 4 through 6. The SB5 working memory subtests correlate .61 with the working memory scale of the Woodcock-Johnson III Test of Cognitive Abilities (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001). Items from the visual-spatial and working subtests are separate from those used in the SB5 routing scales used to calculate Abbreviated IQ.

Procedure

Following a family’s enrollment into the study, mothers completed a demographic questionnaire and nurses completed a history of hospitalization form by reviewing the infant’s medical records at the time of infants’ NICU discharge. Mother–child dyads were invited to the Infant–Parent Interaction Lab at 16-months post-term, and mothers were instructed to play with their toddlers as they did at home prior to engaging in other assessments. Dyads were provided an assortment of age-appropriate toys with which to play, and they were allowed free use of the playroom. The interactions were video-recorded while the experimenter observed through a one-way mirror for the duration of the free-play. Dyads returned to the lab at 24-months post-term and children were administered the SB5 Abbreviated IQ, verbal and nonverbal visual-spatial processing, and verbal and nonverbal working memory subtests as well as other assessments that are described elsewhere (Poehlmann et al., 2009). Assessments lasted up to 2 hr including rest breaks for the children.

Analysis Plan

We tested the study hypotheses in two stages. First, we calculated descriptive means and standard deviations followed by scale intercorrelations (Table I). We converted all predictor and moderator variables to z-scores, and we created continuous interaction terms by multiplying the standardized variables of interest (e.g., SES risk, mother-initiated task changes). Second, we followed Aiken and West’s steps for identifying statistical interactions using continuous interaction terms. We ran a series of three-step hierarchical regression models, one for each outcome variable. We entered mother-initiated task changes and maternal flexibility as moderators in separate models to preserve statistical power. Child IQ was partialled in the first step of all the models in order to reduce its possible confounding effects, followed by the independent and moderator variables in step 2, and the continuous interaction term in step 3. We included conducted separate analyses for each play behavior main effect and interaction. Statistically significant interactions were then plotted using conditional values (±1 SD from the mean) of the moderator variable (e.g., neonatal risk, mother-initiated task changes) and probed by examining the slopes of the simple regression of the 24-month outcome variables onto SES Risk at the conditional values of the moderator (Aiken & West, 1991) (Table III).

Table I.

Scale Intercorrelations, Descriptive Means, and Standard Deviations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | General cognitive abilitya | – | 79.39 (17.02) | ||||||||

| 2 | Neonatal risk | −.16 | – | 3.40 (4.10) | |||||||

| 3 | SES | .44*** | −.04 | – | −.06 (1.77) | ||||||

| 4 | Mother initiated task changes | −.19 | .06 | −.28* | – | 5.22 (2.57) | |||||

| 5 | Mothers’ flexibility | .25* | −.02 | .30* | −.09 | – | 10.63 (4.09) | ||||

| 6 | Nonverbal VSP | .35** | −.04 | .24* | −.19 | .19 | – | 6.84 (1.85) | |||

| 7 | Nonverbal WM | .32** | −.11 | .23* | −.21 | −.05 | .08 | – | 6.96 (2.56) | ||

| 8 | Verbal VSP | .37** | −.13 | .38** | −.19 | .22 | .34** | .16 | – | 5.35 (2.51) | |

| 9 | Verbal WM | .53*** | −.29* | .26* | −.01 | .06 | .33** | .15 | .28* | – | 5.59 (2.68) |

VSP: Visual-spatial processing; WM: working memory.

aSB5 Abbreviated IQ.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table III.

Regression Results for SES × Mother-Initiated Task Changes (Hypothesis 2a)

| Step | Nonverbal VSP |

Nonverbal WM |

Verbal VSP |

Verbal WM |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | ||

| 1 | Neonatal risk | .05 (.21) | .03 | −.16 (.31) | −.06 | −.14 (.26) | −.06 | −.57 (.26)* | −.22 |

| General cognitive ability | .77 (.21)** | .40 | .87 (.31)** | .32 | 1.10 (.26)*** | .45 | 1.30*** | .49 | |

| R2 | .16** | .11* | .21** | .32*** | |||||

| 2 | SES | .03 (.13) | .03 | .02 (.19) | .02 | .21 (.16) | .15 | .11 (.16) | .08 |

| Mother-initiated task changes | −.21 (.22) | –.11 | −.40 (.32) | −.15 | −.18 (.27) | −.07 | .32 (.27) | .12 | |

| ΔR2 | .01 | .02 | .03 | .02 | |||||

| 3 | SES × mother-initiated task changes | .04 (.14) | .04 | −.21 (.20) | −.13 | −.38 (.16)* | −.25 | −.08 | −.05 |

| ΔR2 | .00 | .01 | .06* | .00 | |||||

VSP: Visual-spatial processing; WM: working memory.

*p < .05; **p < .01; *** p < .001.

In addition to testing the study hypotheses, we used a joint significance test to determine whether mother-initiated task changes and/or maternal flexibility mediated associations between SES and 24 neurocognitive outcomes. Joint significance testing establishes the existence of indirect associations between independent and dependent variables using individual regression models to test each mediation pathway (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Testing for mediation in our analyses required two additional sets of hierarchical models. We first regressed mother-initiated task changes and maternal flexibility onto SES in separate models to establish the association between independent and mediator variables. We then regressed the 24-month visual-spatial processing and working memory outcomes onto the maternal play behavior variables in separate models to identify associations between the proposed mediator and dependent variables. We entered mother-initiated task changes and maternal flexibility as mediators in separate models to preserve statistical power. We entered abbreviated IQ scores and neonatal risks as control variables in step 1 of all of the hierarchical models.

Results

Separate regressions were calculated for maternal flexibility and mother-initiated task changes and the four neurocognitive outcomes. First, we present the regression analysis testing our hypothesis that neonatal risk would moderate an association between SES and 24-month outcomes (Hypothesis 1). Results corresponding with Hypothesis 2 are organized in the text and tables by mothers’ parenting behaviors. We focus our discussion of the analyses on the interaction terms in step 3 of the regression models. Effects of the control variables, and the main effects of the independent and moderator variables, can be found in Tables II, III, and IV.

Table II.

Regression Results for SES × Neonatal Risk Interaction (Hypothesis 1)

| Step | Nonverbal VSP |

Nonverbal WM |

Verbal VSP |

Verbal WM |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | ||

| 1 | General cognitive ability | .76 (.21)*** | .40 | .90 (.30)** | .33 | 1.12 (.26)*** | .46 | 1.39 (.26)*** | .53 |

| R2 | .16*** | .11** | .21*** | .28*** | |||||

| 2 | SES | .06 (.13) | .05 | .08 (.19) | .05 | .24 (.16) | .17 | .07 (.16) | .05 |

| Neonatal risk | .05 (.21) | .02 | −.16 (.31) | −.06 | −.15 (.26) | −.06 | −.57 (.26)* | −.22 | |

| ΔR2 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .05 | |||||

| 3 | SES × neonatal risk interaction | .03 (.12) | .03 | .03 (.18) | .02 | −.02 (.15) | –.01 | −.14 (.15) | −.10 |

| ΔR2 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | |||||

VSP: Visual-spatial processing; WM: working memory.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table IV.

Regression Results for SES × Maternal Flexibility (Hypothesis 2b)

| Step | Nonverbal VSP |

Nonverbal WM |

Verbal VSP |

Verbal WM |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | ||

| 1 | Neonatal risk | .05 (.21) | .03 | −.16 (.31) | −.06 | −.14 (.26) | −.06 | −.57 (.26)* | −.22 |

| General cognitive ability | .77** | .40 | .87 (.31)** | .32 | 1.10 (.26)*** | .45 | 1.30 (.26) | .49 | |

| R2 | .16** | .11* | .21*** | .32** | |||||

| 2 | SES | .04 (.13) | .04 | .13 (.19) | .09 | .216 | .16 | .11 (.17) | .07 |

| Mothers’ flexibility | .15 (.23) | .08 | −.45 (.32) | −.17 | .168 | .07 | −.28 (.28) | −.11 | |

| ΔR2 | .01 | .03 | .03 | .01 | |||||

| 3 | SES risk × mothers flexibility | −.03 (.13) | −.03 | .00 (.18) | .00 | .31 (.15)* | .22 | −.06 (.16) | −.04 |

| ΔR2 | .00 | .00 | .05* | .00 | |||||

VSP: visual-spatial processing; WM: working memory.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

The regression analyses testing our hypothesis that neonatal risk would moderate the association between SES and 24-month verbal and nonverbal visual-spatial processing and working memory (Hypothesis 1) was not supported by the analyses (Table II).

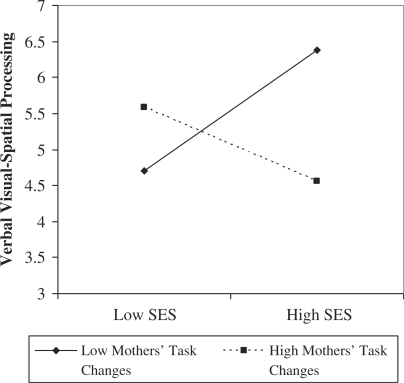

Hypothesis 2, that mothers’ behaviors during a 16-month post-term interaction would moderate associations between SES and verbal and nonverbal working memory and visual spatial processing assessed at 24-months post-term, was partially supported (Table III). We observed that mother-initiated task changes moderated the effect of SES risk on verbal visual-spatial processing (Hypothesis 2a). The interaction term in step 3 accounted for 6% of outcome score variance (p = .02, Cohen’s f2 = .09; B = –.38, SE = .16, p = .02). However, post hoc testing did not reveal statistical significance for the associations between SES and verbal visual-spatial processing at low (1 SD below the mean) (B = .98, SE = .50, p = .08; model R2 = .29, p = .08, Cohen’s f2 = .41) or high (1 SD above the mean) (B = −.01, SE = .30, p = .97; model R2 = .00, p = .97) values of mother-initiated task changes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Significant SES × mother-initiated task changes effect on 24-month verbal visual-spatial processing.

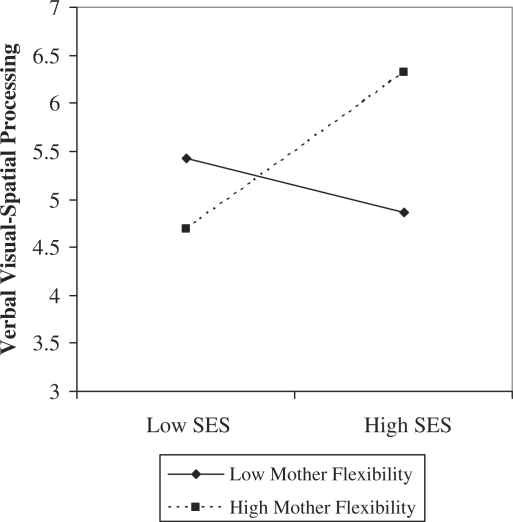

We also found that mothers’ flexibility in response to child-initiated task changes moderated the association between SES and 24-month verbal visual-spatial processing scores after entry of the individual predictors in step 2 (Hypothesis 2b; Table IV). The interaction term accounted for 5% of verbal visual-spatial processing score variance (p = .04, Cohen’s f2 = .07; B = .31, SE = .15, p = .04). The interaction term was significant at high values of mothers’ flexibility (B = .94, SE = .34, p = .02; model R2 = .44, p = .02, Cohen’s f2 = .79), but not at low values (B = .49, SE = .38, p = .22; model R2 = .10, p = .22, Cohen’s f2 = .11). That is, higher SES was associated with higher verbal visual-spatial processing when mothers displayed high levels of flexible responding at 16 months post-term (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Significant SES × mother flexibility effect on 24-month verbal visual-spatial processing.

Neither mother-initiated task changes nor maternal flexibility mediated associations between SES and any of the 24-month outcome variables. Abbreviated IQ and neonatal risks did not predict either mother-initiated task changes (p = .22) or maternal flexibility (p = .05) in step 1 of the models used to assess associations between SES and maternal play behaviors. Similarly, SES did not account for significant variance in mother-initiated task changes (p = .07) or maternal flexibility (p = .09) in step 2 of either of the models.

Our tests of the associations between the maternal play behavior mediators and the neurocognitive outcomes were also nonsignificant. Abbreviated IQ and neonatal risks accounted for 16–32% of 24-month outcome score variance in step 1 of the models (all p’s < .05). Mother-initiated task changes did not contribute significantly to the variance in nonverbal visual-spatial processing (p = .30), nonverbal working memory (p = .18), verbal visual-spatial processing (p = .34), or verbal working memory (p = .28). Maternal flexibility was similarly unrelated to nonverbal visual-spatial processing (p = .47), nonverbal working memory (p = .20), verbal visual-spatial processing (p = .37), or verbal working memory (p = .36).

Discussion

Our analyses did not support our first hypothesis, that neonatal risk would moderate associations between SES and 24-month neurocognitive skills in this sample of children born PT LBW. This is surprising given previous research suggesting that low SES children born PT LBW experience elevated risk for negative outcomes (e.g., Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994). Rather, we found a main effect for neonatal risk as a predictor of verbal working memory, with infants who experienced more neonatal health risks showing less optimal verbal working memory at 24 months post-term. These findings highlight the importance of neonatal health for developmental outcomes in PT LBW children from both high and low SES backgrounds and confirm previous research indicating that cognitive outcomes in PT LBW infants are related to neonatal risk factors (Aylward, 2005; Bhutta et al., 2002).

Neither mother-initiated task changes nor maternal flexibility mediated associations between SES and the neurocognitive outcomes. Instead, we observed partial support for our second hypothesis in that higher SES was associated with more optimal verbal visual-spatial processing when mothers displayed high levels of flexible responding at 16 months post-term. This is consistent with Landry et al.’s (2000) observation that term and preterm children whose mothers engaged in more maintaining behaviors exhibited higher cognitive and language skills when they were 2 and 3.5 years old. Our findings extend those of Landry et al. (2000) because of our focus on children’s neurocognitive skills rather than general cognitive abilities and our examination of this effect within the context of family SES. These results provide provisional evidence that SES may have greater effects on PT LBW children when mothers were more flexible during play. However, based on our analyses, SES appeared to have fewer effects when mothers engaged in low flexibility during play interactions with their PT LBW children.

We also found a significant interaction between mother-initiated task changes and SES risk on children’s verbal visual-spatial processing. Although post-hoc testing was not statistically significant, children experiencing higher SES and fewer mother-initiated task changes obtained the most optimal verbal visual-spatial processing scores. Mothers who initiate fewer task changes during unstructured play in higher SES homes may be facilitating their children’s skill development, whereas this association may not be present in lower SES homes. This finding may point to a distinction between maternal scaffolding and maternal intrusiveness as it pertains to neurocognitive development; it is possible that more task changes may appear like intrusiveness in high SES but not low SES homes, although additional research is needed to examine this possibility. However, this speculation should be viewed with caution due to the nonsignificant post hoc tests and may warrant additional research with a larger, more sociodemographically diverse sample.

Limitations

There are several factors that limit our ability to speak definitively about the roles of mother-initiated task changes and flexible responding in moderating the impact of SES on PT LWB children’s outcomes. First, our inability to calculate nonparticipant rates and participant attrition across timepoints limits our ability to offer definitive conclusions. We were unable to collect demographic information about mothers and children who did not enroll in the larger study at NICU discharge because hospitals did not allow us to make initial contact with families. We are, therefore, unable to determine whether the lowest SES dyads and or the children with the highest neonatal risks were differentially excluded at the recruitment phase of the study. These results should also be viewed as preliminary because many of the participants from the lowest SES homes were lost as the result of attrition between the hospital discharge and 24-month post-term time points. Lack of this information raises the possibility that our findings may only apply to children on the higher functioning ends of the SES-risk spectra. Nevertheless, our SES composite is comprised of a wide range of incomes ($0–$200,000) and maternal education levels (8 –21 years). Our observations of SES effects in this and previous research with this sample (i.e., Dilworth-Bart et al., 2010), suggests that these findings may have significant implications for continued research with a larger, more income diverse sample that is assessed over multiple time points.

Second, study participants included only children born PT LBW and, while this characteristic of our sample allows us to examine the impacts of SES and parenting on the neurocognitive outcomes of medically fragile children, the sample may have lacked the necessary variability in neonatal risk (i.e., all infants were PT or LBW) to identify an SES × neonatal risk interaction. Furthermore, our finding of only one neonatal risk main effect (predicting verbal working memory, Table II) may have occurred because our sample consists of only high neonatal risk children (i.e., no healthy full-term infants). In a similar vein, the limited ethnic diversity in our sample precludes examination of possible cultural influences on mothers’ play behaviors. This is an important caveat to our research because of the significantly greater risk for preterm and/or low birth weight births among women from ethnic minority groups even after controlling for income (Foster et al., 2000; Teitler, Reichman, Nepomnyaschy, & Martinson, 2007).

Third, the subsample used in these analyses was relatively small for identifying moderation effects. Nevertheless, we did observe interaction effects that accounted for modest, yet statistically significant, proportions of 24-month verbal visual-spatial score variance. The small, yet significant, effects we observed may have resulted from our use of a snapshot of mothers’ play behaviors during the 16-month play interaction and child outcomes at 24-months post-term (McCartney and Rosenthal, 2000). Small effects remain important, however, especially when viewed within the overall developmental context of children born PT LBW. The 16-month play interaction provided a discrete assessment of one aspect of children’s everyday lives, and our ability to identify larger effects was, undoubtedly, impacted by limitations of applying statistical models to complex developmental and family processes (McCartney & Rosenthal, 2000; Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003). Moreover, the large number of regression analyses relative to our sample size of 75 increases the probability of Type 1 error.

Implications and Future Directions

Despite these caveats, the small, yet significant effects we observed shed light on family processes that may promote or inhibit emerging competencies and may several implications for future research and possible intervention with children born PT LBW. Our first, additional longitudinal research is needed to both confirm and to further delineate the direction of the association between mothers’ play behaviors and children’s visual-spatial processing skills. Research that includes full child neuropsychological assessments and observations of parent-child interactions across multiple time points and with more income and ethnically diverse participants will also help identify important developmental and parenting trajectories as children born PT LBW transition into preschool and early elementary school.

Second, future research should focus on distinguishing neonatal risk and familial pathways to general cognitive abilities from the pathways to the development of specific neurocognitive skills such as visual-spatial processing. General cognitive abilities independently accounted for 11–28% of outcome score variance (Table II), raising the possibility that mothers’ play behaviors and children’s neonatal risks may indirectly affect children’s neurocognitive skills through their impacts on general cognitive development. However, we are unable to make any inferences about these pathways in the current study because we assessed cognitive abilities, visual-spatial processing, and working memory at the same time points. Distinguishing pathways to specific neurocognitive skills from pathways to general intelligence remains important for the purposes of understanding how developmental context impacts PT LBW children’s development, and subsequently, intervening with this high risk group. However, this is a particularly challenging area of research because of the ongoing debate about the reification of intelligence as well as the lack of identified cortical structures underlying psychometric g (Blair, 2006; Dennis, 2009).

Third, although our findings should be viewed as preliminary, they may point to a need for intervention with PT LBW children and their parents that targets specific parenting behaviors as well as addresses structural aspects of children’s early contexts (e.g., the Infant Health and Development Program) (Ramey & Ramey, 1998). Our finding that mother initiated task changes (i.e., directive behaviors) and flexible responding (i.e., maintaining behaviors) were influential only in higher SES homes is consistent with previous research findings (e.g., Dilworth-Bart et al., 2010; Jaffee, 2007). These findings may indicate that the risks associated with lower SES contexts overwhelm mothers’ best efforts at parenting (McLoyd & Flanagan, 1990). Therefore, meeting practical needs such as providing adequate housing, job training, nutritional resources, and child care; although challenging, may help reduce life stressors that hinder positive interactions and promote negative ones (Dearing, 2004; Youngblut et al., 2001). Intervention with families living in lower SES homes could also focus on helping caregivers identify when their children may benefit from more directiveness or flexibility during interactions. This may be a particularly important area for intervention because parents tend to have greater difficulty reading the cues of infants born PT LBW (Macey et al., 1987).

Finally, while future research in this area should include participants with greater sociodemographic variability to help clarify interactions between parenting behaviors and SES risk, additional research focusing on resilience processes within lower SES families is also needed. Such information can help inform the creation of culturally and contextually relevant interventions designed to promote effective parenting among mothers of PT LBW infants.

Funding

University of Wisconsin (PI to J.D.B.); Center for the Study of Cultural Diversity in Healthcare (National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, MD000506); the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (PI, HD044163 to J.P.).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Doyle L, Callanan C, The Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group Neurobehavioral outcomes of school-age children born extremely low birth weight or very preterm in the 1990s. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(24):3264–3272. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assel M, Landry S, Swank P, Smith K, Steelman L. Precursors to mathematical skills: Examining the roles of visual-spatial skills, executive processes, and parenting factors. Applied Developmental Science. 2003;7(1):27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aylward G P. The relationship between environmental risk and developmental outcome. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1992;13(3):222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylward G P. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born prematurely. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005;26(6):427–440. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200512000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Differential susceptibility to rearing influence: An evolutionary hypothesis and some evidence. In: Ellis B J, Bjorklund D F, editors. Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard K E, Bee H L, Hammond M A. Developmental changes in maternal interactions with term and preterm infants. Infant Behavior & Development. 1984;7(1):101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith L, Rodning C. Dyadic processes between mothers and preterm infants: Development at ages 2 to 5 years. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1996;17:322–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky M, Lewis M. Environmental risk, biological risk, and developmental outcome. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(4):484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta A, Cleves M, Casey P, Cradock M, Anand K. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: A meta-analysis. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(6):728–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. How similar are fluid cognition and general intelligence? A developmental neuroscience perspective on fluid cognition as an aspect of human cognitive ability. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2006;29(2):109–160. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X06009034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci S. Nature-Nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: a bioecological model. Psychological Review. 1994;101(4):568–586. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins S D, Blandon A Y, Williford A P, Keane S P. Biological, behavioral, and relational levels of resilience in the context of risk for early childhood behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(3):675–700. doi: 10.1017/S095457940700034X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Taylor B A, McCartnery K. Implications of family income dynamics for women's depressive symptoms during the first three years after childbirth. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1372–1377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Francis D J, Cirino P T, Barnes M A, Fletcher J M. Why IQ is not a covariate in cognitive studies of neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15(3):331–343. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich S E, Hebert H M, Landry S H, Swank P R, Smith K E. Maternal and child characteristics that influence the growth of daily living skills from infancy to school age in preterm and term children. Early Education and Development. 2004;15(3):283–303. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Bart J E, Khurshid A, Vandell D L. Do maternal stress and home environment mediate the relation between early income-to-need and 54-months attentional abilities? Infant and Child Development. 2007;16(5):525–552. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Bart J E, Poehlmann J, Hilgendorf A E, Miller K, Lambert H. Maternal scaffolding and preterm toddlers’ visual-spatial processing and emerging working memory. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35(2):209–220. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham P J, Dunham F. Optimal social structures and adaptive infant development. In: Moore C, Dunham P J, editors. Joint attention: Its origins and role in development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 159–188. [Google Scholar]

- Foster H W, Wu L, Bracken M B, Semenya K, Thomas J, Thomas J. Intergenerational effects of high socioeconomic status on low birthweight and preterm birth in African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92(5):213–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee S R. Sensitive, stimulating caregiving predicts cognitive and behavioral resilience in neurodevelopmentally at-risk infants. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(3):631–647. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry S H, Garner P, Swank P, Baldwin C. Effects of maternal scaffolding during joint toy play with preterm and full-term infants. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1996;42(2):177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Landry S, Smith K E, Swank P R, Miller-Loncar C L. Early maternal and child influences on children's later independent cognitive and social functioning. Child Development. 2000;71(2):358–375. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw F, Brooks-Gunn J. Cumulative familial risks and low-birthweight children's cognitive and beahvioral development. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23(4):360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Macey T J, Harmon R J, Easterbrooks M A. Impact of premature birth on the development of the infant in the family. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55(6):846–852. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.6.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D, Lockwood C, Hoffman J, West S, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney K, Rosenthal R. Effect size, practical importance, and social policy for children. Child Development. 2000;71(1):173–180. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath M M, Sullivan M. Testing proximal and distal protective processes in preterm high-risk children. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2003;26(2):59–76. doi: 10.1080/01460860390197835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V, Flanagan C. The impact of economic hardship on families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Schwichtenberg A J M, Bolt D, Dilworth-Bart J. Predictors of depressive symptom trajectories in mothers of preterm or low birth weight infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(5):690–704. doi: 10.1037/a0016117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey C T, Ramey S L. Prevention of intellectual disabilities: Early interventions to improve cognitive development. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27(2):224–232. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid G. (2003a) Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, 5th ed. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Roid G. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, 5th ed., Technical Manual. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A J, Chandler M J. Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaking causality. In: Horowitz F D, editor. Review of child development research. Vol. 4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1975. pp. 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A J, MacKenzie M J. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15(3):613–640. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A J, Seifer R. Familial risk and child competence. Child Development. 1983;54(5):1254–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitler J O, Reichman N E, Nepomnyaschy L, Martinson M. A cross-national comparison of racial and ethnic disparities in low birth weight in the United States and England. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):E1182–E1189. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky L S. Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wertsch J V. From social interaction to higher psychological processes: A clarification and application of Vygotsky’s theory. Human Development. 1979;22(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock R, McGrew K, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement III. Itasca IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Youngblut J M, Brooten D, Singer L T, Standing T, Lee H, Rodgers W L. Effects of maternal employment and prematurity on child outcomes in single parent families. Nursing Research. 2001;50(6):346–355. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]