Abstract

The authors describe the case of a now 19-year-old girl who after a traumatic childhood, began to deliberately self-harm at the age of 13, often by cutting her forearms. More recently, however, swallowing inanimate objects has been her method of choice. At the time of writing, she has had over 150 accident and emergency department (A&E) attendances, over 10 gastroscopies and a laparotomy. Knives, razors and six-inch sewing pins have all been removed from her gastrointestinal tract. So far, psychiatrists have been unable to stop her and her risk of accidental death rises every time she deliberately self-harms. The authors include the patient's personal views on her illness and discuss borderline personality disorder as a condition.

Background

Deliberate self-harm in psychiatric illness is common, especially in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). The importance of self-harm is often overlooked. These patients often make numerous visits to emergency departments and psychiatric hospitals but can be very difficult to manage.

Case presentation

Childhood and personal history

The patient is a 19-year-old Caucasian girl, who was born in a British army base in Germany but moved to the UK at the age of 3 where she has lived since. Her family consists of her mother, who works as a catering assistant, her father, who is a businessman, and two older brothers, now aged 23 and 26. Her developmental milestones were normal and she was a bright and clever child who liked horse riding and reading. At an early age, she witnessed her parents fighting and her father was often violent towards her mother. She was systematically physically and sexually abused over several months by her eldest brother starting when she was 7 years old. This abuse mostly occurred while her parents were at work and she was alone at home with her brother. Her grandfather also died around this time, and her mother began drinking heavily to cope with her bereavement. Her parents divorced when she was 8 years old. Her father moved away with the eldest son and the patient and her other brother stayed with their mother, who went on to have a string of violent and abusive partners. She attended mainstream schooling and was predicted to do well in her GCSE exams, but she was bullied and her state of mind adversely affected her ability to study. She began abusing aerosols on a daily basis at school when she was 13 years old and binged on alcohol sometimes up to the point of unconsciousness. She ran away from home when she was 14 and at this time it became apparent that she was cutting her arms and legs. She became angry, stopped enjoying school and eventually only managed to obtain two B grades and two C grades at GSCE level. Around this time, she tried to file charges against her eldest brother for the abuse, but the case was eventually dropped due to a lack of evidence.

Deliberate self-harm

She was first admitted to a psychiatric hospital when she was 15 years old as the frequency of her self-harm increased. Her behaviour included banging her head against a wall, deeply cutting her forearms, pouring hot water over herself, overdosing on over-the-counter analgesics such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, and swallowing inanimate objects such as screws and glass. She spent 2 ½ years in various secure adolescent units, and was briefly placed under section 3 of the Mental Health Act. Over the 2 ½ years, the frequency of her self-harm decreased, but emotional stresses would often bring it on, such as when she heard that the police had closed the investigation against her brother. By the end of this 2 ½ year period, she had 79 A&E attendances. She had a great deal of difficulty in dealing with her sexual abuse, was reluctant to discuss it with psychologists and would often freeze as soon as the topic was mentioned. She was offered intensive therapy sessions but unfortunately only engaged in them briefly. Several medications were tried, including antipsychotics (risperidone 0.5 mg twice daily, quetiapine 300 mg once daily), antidepressants (fluoxetine 20 mg once daily) and mood stabilisers (lamotrigine 200 mg once daily, topiramate 25 mg once daily). None of these helped her behaviour and all medications were eventually stopped. As she approached 18 years of age, she had been off all medication for several months, her behaviour had improved and she had not self-harmed for over 4 months. She was discharged to temporary sheltered accommodation, which specifically supports individuals who aim to move on into independent living. There she started misusing alcohol and began to self-harm again and the staff found it increasingly difficult to manage her – she attended A&E 23 times in one particular month and she was eventually removed from her accommodation. When she was 19 years old she was admitted to an acute adult psychiatric ward. For a short period of time she was placed under section 2, but has mostly been an informal patient (a patient who voluntarily accepts admission). During this admission, she has attended A&E a further 51 times in 3 months, bringing her total number of recorded A&E attendances to date to 152. Her behaviour has included deeply cutting open her forearms with blades, razors, CD edges, screws, tin lids or any sharp object. After having her wounds stitched up by A&E doctors, she often then picks at the stitches until the wound is raw, bleeding or infected. She has also overdosed on over-the-counter analgesics such as paracetamol and ibuprofen (four times) and once tried to ligature her neck, but increasingly, her preferred method of self-harm has been to swallow household objects, such as whole forks, cutlery knives, lighters, sewing pins, glass shards, razor blades, pens and pencils, in fact anything that is available to hand and fits into her mouth. These objects are often sharp or pointed, putting her at risk of bowel perforation and she has had over 30 abdominal radiographs (figures 1 and 2), a CT of the neck for an imbedded safety pin (figure 3) and over 12 flexible and rigid oesophagoscopies to date (figure 4) to try and remove these objects. During her most recent rigid oesophagoscopy to remove four open safety pins just distal to the pylorus, the rigid scope was too short and the grasper would not allow their removal through the oesophagus, so the procedure was converted to an open laparotomy by thoracic surgeons using an upper midline incision and via an anterior gastrostomy, which was successful.

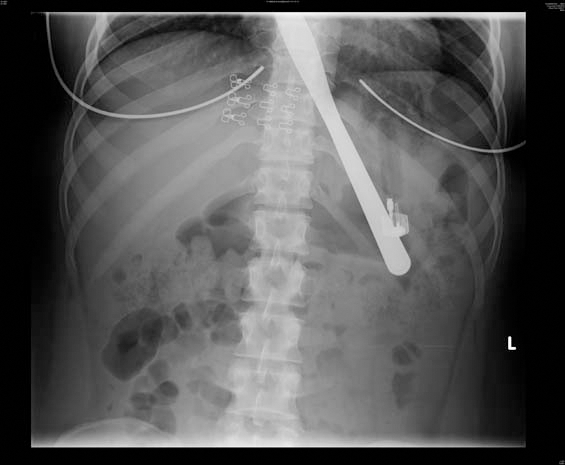

Figure 1.

Abdominal radiograph showing a lighter, multiple sewing needles and pieces of glass in the bowel.

Figure 2.

Abdominal radiograph showing a knife and a lighter in the stomach.

Figure 3.

CT of the neck showing the right limb of an open safety pin extending through the posterior wall of the pharynx and lying just 7 mm away from the internal carotid artery.

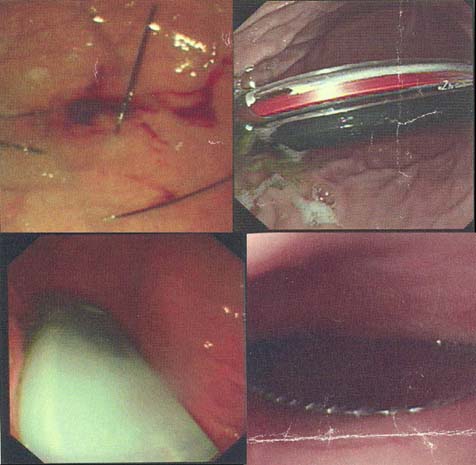

Figure 4.

Endoscopy photographs clockwise from top left, showing sewing needles in the fundus of the stomach, a pen in the cardia of the stomach, a knife in the distal oesophagus, and a cigarette lighter in the fundus of the stomach.

Patient perceptions

The patient describes her feelings as follows:

I keep having flashbacks of the abuse I suffered at the hands of my brother when I was seven. I cut myself as a way of releasing blood. My self-harm is a way of discharging negative emotions and coping because my parents were not able to support me emotionally when I revealed the abuse. I cannot guarantee I will not do it again in future.

Outcome and follow-up

At the moment, she remains an informal patient on an acute adult psychiatric ward. She has voluntarily accepted an antidepressant (citalopram 20 mg once daily) and an antipsychotic depot injection (depixol 40 mg every 2 weeks), but these have not had much effect. Her admission does not seem to have benefited her and she continues to be at risk of self-harm if not constantly monitored. She has declined all further psychotherapy and counselling sessions, but has agreed to a care plan where after an incident of self-harm, she is placed on 24 h constant one-to-one nursing with the level of nursing observation gradually reducing as her feelings of self-harm diminish. Although she does not appear to have the intention of actually killing herself, the possibility of death by misadventure is always present. She is awaiting placement at a unit that specialises in assessing and treating young adults with personality disorder. The aim in the long term is to eventually manage her in the community.

Discussion

This patient has a diagnosis of BPD combined with a lesser element of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Personality disorder is a common psychiatric condition, and although it has been associated with several reported cases of deliberate self-harm associated,1 there have been no cases to date of a single patient self-harming with such frequency and regularity.

Diagnosis and epidemiology of BPD

Personality disorder is defined as an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the culture of the affected individual2 and BPD is defined as a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image and marked impulsivity beginning in early adulthood.3 Diagnosis requires five or more of the following features to be present: identity disturbance, impulsivity, unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment, recurrent suicidal behaviour, chronic feelings of emptiness, inappropriate often intense anger or difficulty controlling anger.4 Prevalence in the UK is 0.7%5 and it is also present in the developing world. Males and females are equally affected, but females are more likely to seek help and hence more females are diagnosed with the condition. Many people with BPD are able to live a fulfilling life, but they are more likely than the general population to self-harm, have eating problems and misuse alcohol or illicit substances. PTSD is linked with BPD in two ways. Firstly, patients with BPD and a history of abuse in childhood can go onto develop PTSD and secondly, as a result of the interpersonal difficulties patients with BPD face, they are at risk of putting themselves in situations in which they are more likely to be harmed and suffer PTSD as a consequence of the harm suffered.3

BPD and self-harm

A wide array of self-harm behaviour has been reported in the literature, with objects not just swallowed but also inserted into the abdomen, the heart, the airway, the bladder, the breast, the ear, legs, arms and even the cranium.1 Self-harm in BPD is often used, not with the intention of committing suicide, but to provide relief from acute distress, anxiety or feelings of emptiness or anger. In our patient's case, after each episode of self-harm she alerts a member of staff. If nobody is around, she will phone an ambulance herself and tell paramedics what she has done. Recently after taking an overdose of 16 paracetamol tablets, she informed staff that prior to taking the tablets, she had researched on the internet as to how many paracetamol tablets would be dangerous and had then deliberately taken a lower dose which she perceived to be a safer amount. These actions suggest that she does not want to kill herself and has the ability to assume responsibility for her actions. A psychologist who recently assessed her described her as an “emotionally immature girl, behaving like an adolescent but being expected to assume adult responsibilities. Her lack of life experiences and lack of what responsibility means strongly affects her behaviour. Her difficult childhood, no clear boundaries and an absence of a loving safe environment impacts on her ability to regulate her emotions and she is acting out in the only way she knows how”. In these patients, the act of swallowing objects has a combined function of self-punishment, the punishment of others (those perceived to have harmed them or whom they may blame for their feeling of despair or rejection), as well as forcing others to provide care. Once the ingestion is reported, radiographs are usually required, often followed by the medical necessity of retrieving the object. Patients who might otherwise be feeling powerless are suddenly able to exert enormous leverage.1 This process of struggling for power may be one of the unconscious motivations for the behaviour. At the same time, the counter-transference anger that doctors often feel in these situations speaks to their own sense of powerlessness at being controlled by the patient.1 This process of frustrating and challenging doctors may also be a motivation.

Up to 60–70% of people with BPD will self-harm at some point in their lives and 10% will go onto kill themselves.6 This equates to a rate of suicide 400 times that of the general population.7 People with BPD make more extensive use of intensive treatments such as emergency department visits and psychiatric hospital services, resulting in higher related healthcare costs compared with people with other psychiatric disorders.8 In 2008/2009 deliberate self-harm in England alone accounted for 101 670 A&E attendances, constituting 0.8% of all A&E attendances that year.9 Interestingly, self-harm is not a behaviour confined to humans alone. In macaque monkeys, incidents of self-harm have been well documented in the literature. Laboratory rearing and isolation, particularly in infancy, have been noted to be important predisposing factors.10 Captive birds have also been observed to feather pluck, sometimes severely damaging or removing all of their feathers.11 Lower mammals are also known to mutilate themselves under laboratory conditions after administration of sympathetic drugs such as amphetamines.12

Aetiology of BPD

The aetiology of BPD is complex, but involves genetic factors, neurotransmitters and psychosocial factors. Essentially, individuals who are constitutionally vulnerable (genetic factors) who are exposed to influences that undermine their psychological development such as abuse (psychosocial factors) at a young age, may undergo changes in their developing brains (neurotransmitters).3 Twin studies have found that the heritability factor for BPD is 0.69, however it is likely that personality traits such as impulsivity and mood dysregulation are inherited rather than BPD itself.13 Lower levels of the neurotransmitter 5-HT 1A have been found in women with BPD.14 A history of physical, sexual or emotional abuse is well associated with the development of BPD and 84% of people with BPD have described some kind of parental neglect and emotional abuse as a child.15 In our patient's case she experienced the divorce of her parents, her grandfather's death, her mother's grief and alcohol abuse, and sexual abuse at the hands of her brother, and witnessed violence at home during her early childhood. The critical factor, however, in the development of BPD after abuse is thought to be the family environment.16 A sound family environment that encourages communication and is supportive of a child following abuse, is more likely to facilitate successful adjustment, something which this patient lacked.

Management and prognosis of BPD

The management of BPD requires a multidisciplinary approach, includes medication and psychological therapies and can be very challenging.

Depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD, substance misuse disorder and psychosis are all more prevalent in people with BPD than in the general population and respond to appropriate medication. In one American study, 61% of patients with BPD had been prescribed an antidepressant at some point during their treatment, 35% an anxiolytic, 27% a mood stabiliser and 10% an antipsychotic.8 Such treatment is often started during periods of crisis and the placebo response rate is high. The initial crisis usually resolves itself irrespective of drug treatment. No psychotropic drug is specifically licensed for the management of BPD and there is always the risk of overdose.3

There are several psychological therapies for people with BPD3 which have been shown to lower rates of attempted suicide.7 Patients must consent to these therapies willingly, and their benefits will not be seen if this does not occur, such as in the case of our patient. If patients do consent, therapy is often still extremely challenging because they often will express their suicidality in ways that evoke empathy from therapists. These reactions, in turn, escalate suicidal behaviours to evoke further caring reactions from the therapist. There is also a danger if the patient's distress signals are ignored, which can then cause the patient to feel neglected, thus increasing the risk of further self-harm.17

Psychological therapies can be delivered by psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, social workers and other mental health therapists in many different ways such as one-to-one therapy sessions, group work or telephone support to patients at home. Cognitive therapy can be helpful in people with a co-existing mental disorder such as depression. Dialectical behaviour therapy aims to develop emotion regulation strategies. Cognitive analytic therapy aims to address interpersonal difficulties. Arts therapies that involve art, dance, drama or music can help those who find it hard to express thoughts and feelings verbally. Therapeutic communities are another method. These are consciously designed social environments and programmes within a residential or day unit in which the social and group process is harnessed with therapeutic intent. Our patient is currently awaiting placement at one of these units. In group analytic psychotherapy, the relationships between the members, and between the members and the therapist comprise the main therapeutic tool. Systemic therapy is used with families where the affected patient is a child. Patients with concurrent PTSD can also benefit from specific trauma-focused psychological therapy.

The role of hospital admission is controversial. Although necessary in some severe cases, psychiatric hospital admissions are expensive, and may be ineffective and counterproductive.17 Brief psychiatric hospitalisation may be justified for protection against suicide, psychotic or dissociative symptoms, to save others from harm or when the patient is experiencing an acute stressful life event.18 However, many psychiatrists believe that hospitalisation has little proven value in preventing suicide among these patients19 21 and a history of repeated hospitalisation is actually associated with a higher rate of completed suicide.17 This is because the patient may perceive themselves to be in a place of safety and then they often increase the level of the severity and the nature of the risks that they take.20 In our patient's case, there has been no evidence to suggest that psychiatric containment has reduced her risk of self-harm and she continues to self-harm while on an acute ward.

The prognosis for patients with BPD is usually poor, owing to poor access to mental health services for many, a discontinuity of care, for example, if the patient drops out of services, poor communication during therapy, a lack of social support and non-compliance with treatment.21

Learning points.

-

▶

Self-harm in borderline personality disorder (BPD) is common, with 60–70% of patients deliberately harming themselves and 10% eventually going on to kill themselves.

-

▶

The management of BPD can be slow, complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach.

-

▶

The role for psychiatric hospitalisation is controversial, and has actually increased the rate of completed suicide.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Gitlin DF, Caplan JP, Rogers MP, et al. Foreign-body ingestion in patients with personality disorders. Psychosomatics 2007;48:162–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth edition (text revision). (DSM-IV-TR) Arlington, VA: APA; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.NICE Guidelines for Borderline Personality Disorder, 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/Borderline%20personality%20disorder%20full%20guideline-published.pdf

- 4.APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth edition (DSMIV) Washington, DC: APA; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, et al. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:423–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oldham JM. Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:20–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oumaya M, Friedman S, Pham A, et al. [Borderline personality disorder, self-mutilation and suicide: literature review]. Encephale 2008;34:452–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health and Social Care Information Centre Accident and Emergency Attendances in England, 2009. http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=1271-

- 10.Jones IH, Barraclough BM. Auto-mutilation in animals and its relevance to self-injury in man. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1978;58:40–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins JR. Feather picking and self-mutilation in psittacine birds. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract 2001;4:651–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller K, Nyhan WL. Clonidine potentiates drug induced self-injurious behavior in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1983;18:891–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torgersen S, Lygren S, Oien PA, et al. A twin study of personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2000;41:416–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinne T, Westenberg HG, den Boer JA, et al. Serotonergic blunting to meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (m-CPP) highly correlates with sustained childhood abuse in impulsive and autoaggressive female borderline patients. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47:548–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Biparental failure in the childhood experiences of borderline patients. J Pers Disord 2000;14:264–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz AV, Widom CS, McLaughlin J, et al. The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: a prospective study. J Health Soc Behav 2001;42:184–201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis T, Gunderson JG, Myers M. Borderline personality disorder. In: Jacobs DG, ed. The Harvard Medical School Guide to Suicide Assessment and Intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1999:311–31 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter GL, Lewin TJ, Stoney C, et al. Clinical management for hospital-treated deliberate self-poisoning: comparisons between patients with major depression and borderline personality disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005;39:266–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linehan M. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY: Guildford; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paris J. Chronic suicidality among patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53:738–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storey P, Hurry J, Jowitt S, et al. Supporting young people who repeatedly self-harm. J R Soc Promot Health 2005;125:71–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]