Abstract

We describe a cell-based assay for studying vitamin K–cycle enzymes. A reporter protein consisting of the gla domain of factor IX (amino acids 1-46) and residues 47-420 of protein C was stably expressed in HEK293 and AV12 cells. Both cell lines secrete carboxylated reporter when fed vitamin K or vitamin K epoxide (KO). However, neither cell line carboxylated the reporter when fed KO in the presence of warfarin. In the presence of warfarin, vitamin K rescued carboxylation in HEK293 cells but not in AV12 cells. Dicoumarol, an NAD(P)H-dependent quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) inhibitor, behaved similarly to warfarin in both cell lines. Warfarin-resistant vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR-Y139F) supported carboxylation in HEK293 cells when fed KO in the presence of warfarin, but it did not in AV12 cells. These results suggest the following: (1) our cell system is a good model for studying the vitamin K cycle, (2) the warfarin-resistant enzyme reducing vitamin K to hydroquinone (KH2) is probably not NQO1, (3) there appears to be a warfarin-sensitive enzyme other than VKOR that reduces vitamin K to KH2, and (4) the primary function of VKOR is the reduction of KO to vitamin K.

Introduction

Vitamin K hydroquinone (KH2) is a cofactor for γ-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX), which catalyzes the posttranslational carboxylation of specific glutamic acid residues to γ-carboxyglutamic acid (gla) in a variety of vitamin K–dependent proteins.1 γ-Glutamyl carboxylation is essential for the biologic functions of vitamin K–dependent proteins involved in blood coagulation, bone metabolism, signal transduction, and cell proliferation. Concomitant with γ-glutamyl carboxylation, KH2 is oxidized to vitamin K 2,3-epoxide (KO). KO must then be converted back to vitamin K (the quinone form) and then to KH2 by separate 2 electron reductions to support the carboxylation reaction. The cyclic production of KO and the conversion back to KH2 constitutes the vitamin K cycle (Figure 1). The only enzymes unequivocally identified as part of the cycle are GGCX and vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR).2

Figure 1.

Vitamin K cycle. During vitamin K–dependent carboxylation of glutamic acid to γ-carboxyglutamic acid, the reduced form of vitamin K (KH2) is oxidized to KO by GGCX. KO is reduced to vitamin K by VKOR using the enzyme's 2 active-site cysteine residues. This reaction is sensitive to warfarin inhibition. The reduction of vitamin K to KH2 is carried out in 2 pathways. One pathway is sensitive to warfarin inhibition and also involves 2 free cysteine residues in the enzyme active site (VKOR). The second pathway is resistant to warfarin and uses NAD(P)H as a cofactor.

Sherman et al first proposed that the reduction of KO to vitamin K is carried out by a sulfhydryl-dependent epoxide reductase that is sensitive to warfarin inhibition.3 This enzyme is probably VKOR, the only enzyme thus far shown to reduce KO to vitamin K. On the other hand, some reports suggest that the reduction of vitamin K to KH2 can be accomplished by at least 2 microsomal enzymes called vitamin K reductases.4 However, other studies5,6 suggest that one enzyme serves as both the epoxide reductase and the vitamin K reductase, catalyzing both the reduction of KO to vitamin K and that of vitamin K to KH2.

Wallin proposed that there are 2 enzymes that reduce vitamin K in support of vitamin K–dependent carboxylation.7 One enzyme is inhibited by anticoagulant drugs such as warfarin,8 while the other is an NADH-dependent reductase that is resistant to inhibition by warfarin.4,9–11 Consistent with the latter result, when a person ingests toxic amounts of warfarin-like drugs, thus inhibiting VKOR, the usual treatment is large doses of vitamin K. The enzyme that is not inhibited by warfarin, often called antidotal, can then convert the vitamin K to KH2 and thus reverse the toxic effects of warfarin.12,13

One candidate for the antidotal enzyme is the dicoumarol-sensitive NAD(P)H-dependent quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1, or DT-diaphorase). NQO1 catalyzes the 2-electron reduction of menadione (vitamin K3) to menadione hydroquinone, which reduces oxidative stress in vivo.14 Wallin et al11 reported that microsomes with no NQO1 have decreased carboxylation activity. Adding back purified NQO1 fully restored the ability of the microsomal extract to carboxylate the pentapeptide substrate Phe-Leu-Glu-Glu-Leu (FLEEL). On the other hand, Preusch and Smalley reported that NQO1 contributes minimally to vitamin K reduction during the carboxylation reaction.6 A melanoma cell–based study of dicoumarol inhibition suggests that NQO1 is not involved in vitamin K metabolism.15 In addition, NQO1-knockout mice do not appear to have bleeding problems.16 These results demonstrate the need to clarify the role of NQO1 and perhaps other, as yet unidentified, enzymes in the vitamin K cycle.

In addition to questions about the identity of the warfarin-resistant antidotal enzyme, there appears to be a different distribution of the warfarin-sensitive and warfarin-resistant vitamin K reductase.17–19 Ulrich et al have shown that warfarin-resistant vitamin K reductase activity is significantly lower in osteoblast-like bone cells than it is in hepatocytes.18 Therefore, vitamin K overcomes the effect of warfarin in liver cells but not in osteoblasts; this was termed the “liver-bone dichotomy” model.19

Identification of the gene encoding VKOR20,21 has made it possible to study the function of the enzyme at the molecular level. It is now clear that, in vitro, VKOR can reduce both KO to vitamin K and vitamin K to KH2. VKOR catalyzes both reactions using the same cysteine residues (132 and 135) at the active site.22,23 In addition, both reactions are sensitive to warfarin inhibition.23 It is worth noting that, in vitro, VKOR converts KO to vitamin K approximately 50 times faster than it converts vitamin K to KH2.23 Whereas we have purified and characterized both VKOR and GGCX, the enzymes have very different lipid and/or detergent requirements for activity, which makes studying the interactions and activities of the enzymes together in vitro difficult. In addition, there are other enzymes of the vitamin K cycle yet to be identified.

In the present study, we developed a cell-based reporter assay system that enables the functional study of the complete vitamin K cycle. In this system, we expressed a vitamin K–dependent reporter protein that is easily measured and that reflects the efficiency of vitamin K–dependent carboxylation in vivo. We used protein C as the reporter for this study. For detection purposes, we replaced the gla domain of protein C with that of factor IX (FIX). This replacement allowed us to use a monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific for the carboxylated gla domain of FIX for quantitative detection purposes.24,25 We stably expressed this chimeric reporter protein, FIXgla-PC, in HEK293 cells, which are commonly used for the biosynthesis of vitamin K–dependent proteins, and in AV12 cells, which are less efficient in the carboxylation of vitamin K–dependent proteins.26 Studies have indicated that recombinant protein C produced by HEK293 cells is fully carboxylated and even more active than plasma-derived protein C. Under similar conditions, protein C produced by AV12 cells is partially carboxylated, with 20% anticoagulant activity relative to plasma protein C.26 This result indicates that HEK293 and AV12 cells might have different vitamin K pathways for making vitamin K–dependent proteins. We expected that by expressing the reporter protein in these 2 cell lines, feeding the cells KO or vitamin K with or without warfarin, expressing warfarin-resistant VKOR-Y139F, and using dicoumarol to inhibit NQO1, the contributions of the various enzymes involved in the 2-step reduction of KO could be determined.

Methods

Materials

Vitamin K1, warfarin, dicoumarol, and 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. KO was prepared as described previously.27 Vitamin K1 (10 mg/mL) for cell culture was from Abbott Laboratories. A vitamin K internal standard for VKOR activity assay, 2-methyl-3(3,7,11,15,19-pentamethyl-2-eicosenyl)-1,4-naphthalenedione, also known as vitamin K1(25), was from GLSynthesis. Protein C cDNA clone was from Open Biosystems. Mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1/hygro(+) and Lipofectamine were from Invitrogen. Mammalian expression vector pCI-neo was from Promega. HEK293 and AV12 cell lines were from ATCC. Mouse anticarboxylated FIX gla domain (α-FIXgla) mAb was a gift from GlaxoSmithKline and Green Mountain Antibodies.28 Affinity-purified sheep anti–human protein C immunoglobulin G (IgG) and its horseradish peroxidase conjugate were from Affinity Biologicals.

Construction of the FIXgla-PC reporter fusion protein

The gene encoding human protein C was amplified by polymerase chain reaction using pCMV-SPORT6-protein C as a template. The gla domain of protein C (residues 1-46) was exchanged with the gla domain of FIX. This FIXgla-PC fusion was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1/hygro(+) using the XbaI site to generate the reporter protein expression vector pcDNA3.1-FIXgla-PC.

Expression of the FIXgla-PC in HEK293 and AV12 cells

The FIXgla-PC reporter protein was stably expressed in HEK293 or AV12 cells. Cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-FIXgla-PC plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine according to the manufacturer's protocol. After selection with 300 μg/mL of hygromycin, surviving colonies were picked and screened for high stable expression. Single colonies were cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium/nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 11μM vitamin K, and 1× antibiotics-antimycotics (complete medium) in a 24-well plate for 48 hours. Cell-culture medium was collected and used directly for quantification of the secreted carboxylated FIXgla-PC by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The colony with the highest FIXgla-PC production was selected as the stable cell line to be used for reporter gene expression.

To purify carboxylated FIXgla-PC fusion proteins for use as a standard for ELISA, α-FIXgla mAb was coupled to Affi-Gel 10 (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's protocol. HEK293 cells stably expressing a high level of FIXgla-PC reporter protein were cultured in complete medium supplemented with 11μM vitamin K. The medium was collected after 48 hours of incubation. Calcium chloride was added to the collected medium to a final concentration of 5mM. Five hundred milliliters of the medium was incubated with 1.5 mL of the prepared anticarboxylated FIXgla domain affinity beads overnight at 4°C with gentle stirring. The beads were spun down and packed into a 1.5 × 10-cm column. The column was washed first with 20mM Tris-HCl, 500mM NaCl, and 5mM CaCl2, and then with 20mM Tris-HCl, 100mM NaCl, and 5mM CaCl2. Carboxylated FIXgla-PC reporter protein was eluted with 20mM Tris-HCl, 100mM NaCl, and 10mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid).

To examine the effect of vitamin K, KO, warfarin, or dicoumarol on the carboxylation of the reporter protein, HEK293 or AV12 cells stably expressing FIXgla-PC were subcultured in 24-well plates in the absence of vitamin K. When cells were 60%-70% confluent, vitamin K, KO, warfarin, or dicoumarol was added to the complete medium and incubated for 48 hours. Cell-culture medium was collected and directly used in an ELISA, as described in the following section.

FIXgla-PC measurement in cell-culture medium using ELISA

The reporter protein in the cell-culture medium was quantified by ELISA, as described previously with minor modifications.29 To assay for carboxylated FIXgla-PC, we used a conformation-specific mAb that recognizes only the fully carboxylated FIXgla domain in the presence of calcium as the coating antibody.28 ELISA plates (96-well) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μL/well of α-FIXgla mAb. The concentration of the coating antibodies was 2 μg/mL in 50mM carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). After being washed 5 times with TBS-T wash buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20), the plate was blocked with 0.2% bovine serum albumin in TBS-T wash buffer for 2 hours at room temperature. Samples and protein standards (0.12-250 ng/mL) with 5mM CaCl2 were added at 100 μL/well and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After being washed with TBS-T wash buffer containing 5mM CaCl2, sheep anti–human protein C IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (100 μL/well at 1:2500 in TBS-T wash buffer with 5mM CaCl2) was added to each well and incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature. After the unbound detecting antibody was washed off, 100 μL of 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid; ABTS) solution (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) was added to each well and the absorbance was determined at 405 nm with a ThermoMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices). The linear range for detection of carboxylated FIXgla-PC was between 0.50 and 125 ng/mL (γ = 0.9987) using the logit (OD)-log (FIXgla-PC) plot.

To assay for total reporter protein secreted into the cell-culture medium, 96-well ELISA plates were coated with 100 μL/well of mouse anti–human protein C mAb overnight at 4°C. After being washed and blocked as described in the preceeding paragraph, samples and protein standards (0.12-250 ng/mL) were added and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After the unbound samples were washed off, sheep anti–human protein C IgG was added to each well and incubated for another 2 hours at room temperature. The unbound antibody was then washed off and the plate was incubated with 100 μL/well of rabbit anti–sheep IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 45 minutes at room temperature. Color development was performed as described in the preceding paragraph.

Functional study of warfarin-resistant VKOR-Y139F in established cell lines

To study the contribution of VKOR to the vitamin K cycle, a warfarin-resistant VKOR mutant, VKOR-Y139F, was cloned into the mammalian expression vector pCI-neo. The resulting plasmid was transiently or stably transfected into the established cell line FIXgla-PC/HEK293 or FIXgla-PC/AV12. The culture medium on the cells transiently expressing VKOR was changed 30 hours after transfection to complete medium containing 5μM KO or 5μM KO + 2μM warfarin. Cell-culture medium was collected after 48 hours incubation and directly used for ELISA. The stably transfected colony that expressed the highest level of VKOR-Y139F was selected for further study. The effect of overexpressing the VKOR-Y139F mutant on reporter protein carboxylation under different conditions was tested as described in “Expression of the FIXgla-PC in HEK293 and AV12 cells.”

GGCX activity assay

GGCX activity was determined by the incorporation of 14CO2 into the pentapeptide substrate FLEEL in the presence of propeptide.30 1 × 106 of HEK293 or AV12 cell pellets were mixed with 115 μL of ice-cold lysis buffer containing 0.5% CHAPS, 25mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500mM NaCl, 4μM FIX propeptide, 1.25mM FLEEL, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. Samples were placed on ice for 30 minutes with occasional vortexing. The carboxylation reaction was started by the addition of 10 μL of an ice-cold mixture of NaH14CO3 (40 μCi/mL) and KH2 (222μM) to bring the volume to 125 μL. The reaction mixture was immediately transferred to a 20°C water bath and incubated for 45 minutes. The amount of 14CO2 incorporation was determined as described previously.31

VKOR activity assay

VKOR activity was determined as described previously with minor modifications.21,32 HEK293 or AV12 cells (1 × 107) were collected and resuspended in 200 μL of ice-cold assay buffer containing 25mM N-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]-3-aminopropane-sulfonic acid (pH 8.6), 150mM NaCl, 30% glycerol, 50μM KO, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were lysed by sonication on ice. The reaction was started by adding 5mM (final concentration) freshly prepared dithiothreitol and incubated at 30°C in the dark for 45 minutes. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 500 μL of isopropanol. The reaction mixture was extracted with 500 μL of n-hexane containing 2.52μM vitamin K1(25) as an internal standard. The upper organic phase containing the vitamins was transferred to a 2-mL brown vial and dried with nitrogen. A total of 500 μL of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) mobile phase was added to dissolve the vitamins, and the sample was analyzed by HPLC.32

Results

FIXgla-PC chimera as a reporter protein for vitamin K–dependent carboxylation efficiency in living cells

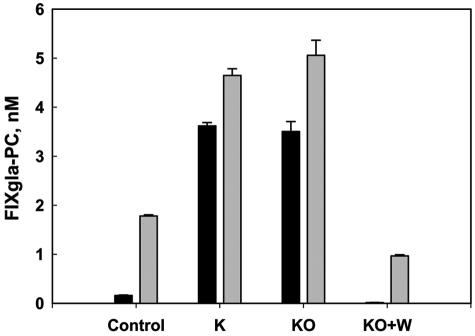

To study the vitamin K cycle in vivo, we expressed the chimeric reporter protein FIXgla-PC as a tool for determining the efficiency of in vivo vitamin K–dependent carboxylation. We felt this would allow us to study the function of the enzymes of the vitamin K cycle. The results shown in Figure 2 support this idea. As expected based on our present understanding of the cycle, in the presence of vitamin K or KO, secretion of carboxylated reporter protein increased approximately 25-fold (Figure 2) compared with no additions. Warfarin, an inhibitor of VKOR, eliminated KO-supported carboxylation. In addition, similar levels of carboxylated reporter were secreted independently of the substrate (vitamin K or KO) fed to the cells, which allowed us to differentiate some of the functions of the various enzymes involved in the cycle.

Figure 2.

Effect of vitamin K, KO, and warfarin on FIXgla-PC carboxylation and secretion. Carboxylated (■) and total ( ) FIXgla-PC secreted from HEK293 cells under different culture conditions was measured by ELISA as described in “FIXgla-PC measurement in cell-culture medium using ELISA.” Control, complete medium (no added vitamin K); K, complete medium with 11μM vitamin K; KO, complete medium with 5μM KO; KO + W, complete medium with 5μM KO + 2μM warfarin

) FIXgla-PC secreted from HEK293 cells under different culture conditions was measured by ELISA as described in “FIXgla-PC measurement in cell-culture medium using ELISA.” Control, complete medium (no added vitamin K); K, complete medium with 11μM vitamin K; KO, complete medium with 5μM KO; KO + W, complete medium with 5μM KO + 2μM warfarin

Effect of substrate and/or warfarin on FIXgla-PC carboxylation in HEK293 cells

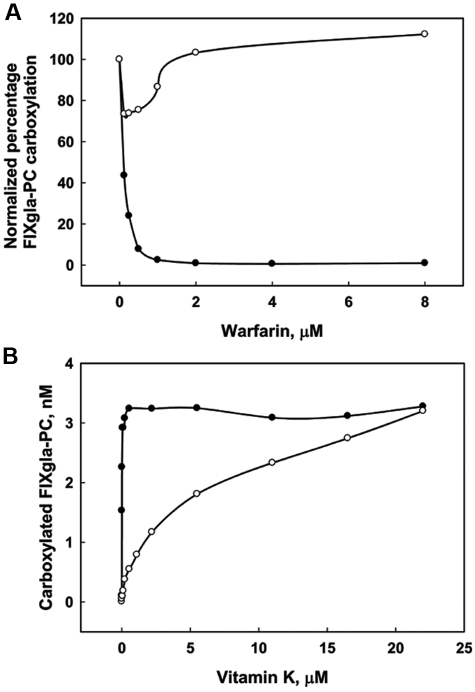

With KO as the substrate, FIXgla-PC carboxylation was completely inhibited by 2μM warfarin and 50% inhibition occurred with 0.1μM warfarin (Figure 3A). Thus, VKOR, the molecular target for warfarin, is responsible for the reduction of KO in vivo. Whereas warfarin totally inhibited FIXgla-PC carboxylation when HEK293 cells were fed KO, HEK293 cells fed vitamin K produced high (unaffected) levels of carboxylated protein in the presence of warfarin (Figure 3A). This result suggests that as long as there is enough vitamin K in the medium, inactivation of VKOR by warfarin does not affect the conversion of vitamin K to KH2 in HEK293 cells. This was confirmed by the results shown in Figure 3B, which shows the amount of the carboxylated FIXgla-PC secreted as a function of vitamin K concentration in the presence and absence of warfarin. In the absence of warfarin, carboxylation occurred maximally at 1μM vitamin K. However, in the presence of warfarin, less than 20% of the carboxylated reporter protein was detected in the medium at 1μM vitamin K, and maximal carboxylation was detected in the medium at 22μM vitamin K. The decreased carboxylation efficiency observed at lower vitamin K concentrations in the presence of warfarin might have been because of the inability of cells to recycle KO or to a low affinity/catalytic efficiency of the warfarin-resistant vitamin K reductase in cells. These results suggest that at high vitamin K concentrations, HEK293 cells efficiently support vitamin K–dependent carboxylation, even when VKOR is inactivated by warfarin. Therefore, there must be a warfarin-resistant enzyme that reduces vitamin K to KH2 in HEK293 cells. This enzyme might be the antidotal enzyme that allows patients poisoned with warfarin to be rescued with high doses of vitamin K.33,34

Figure 3.

Effect of warfarin on FIXgla-PC carboxylation in HEK293 cells. (A) Cells grown in culture medium with either 11μM vitamin K (○) or 5μM KO (●) were incubated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of warfarin. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the medium was measured by ELISA. The data are presented as percentages to make the first concentration points of vitamin K and KO coincide. (B) Cells were grown with (○) or without (●) 2μM warfarin in increasing concentrations of vitamin K for 48 hours. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the culture medium was measured by ELISA.

Expression of FIXgla-PC in AV12 cells

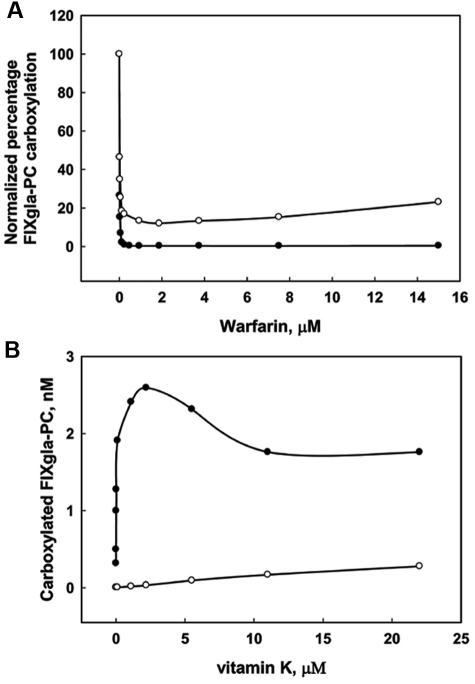

We stably expressed the FIXgla-PC in AV12 cells, which carboxylate vitamin K–dependent proteins less efficiently than HEK293 cells.26 Under similar conditions, AV12 cells produced only approximately half as much carboxylated reporter protein as HEK293 cells (data not shown). We then tested the effect of warfarin on FIXgla-PC carboxylation in AV12 cells using KO or vitamin K as the vitamin K source. When KO was used as a substrate, the inhibition curve of warfarin on reporter protein carboxylation (Figure 4A) was similar to that observed in HEK293 cells (Figure 3A). In contrast to HEK293 cells, in AV12 cells, the production of carboxylated reporter protein was significantly inhibited by warfarin when vitamin K was used as a substrate (Figure 4A). In addition, high concentrations of vitamin K did not rescue warfarin inhibition in AV12 cells (Figure 4B). These results suggest that warfarin-sensitive VKOR is responsible for KO reduction and that the amount of warfarin-resistant antidotal enzyme that reduces vitamin K is dramatically less in AV12 cells than in HEK293 cells.

Figure 4.

Effect of warfarin on FIXgla-PC carboxylation in AV12 cells. (A) Cells grown in culture medium with either 11μM vitamin K (○) or 5μM KO (●) were incubated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of warfarin. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the medium was detected by ELISA. The data are presented as percentages to make the first concentration points of vitamin K and KO coincide. (B) Cells were grown with (○) or without (●) 2μM warfarin in increasing concentrations of vitamin K for 48 hours. The concentration of carboxylated reporter protein in the culture medium was measured by ELISA.

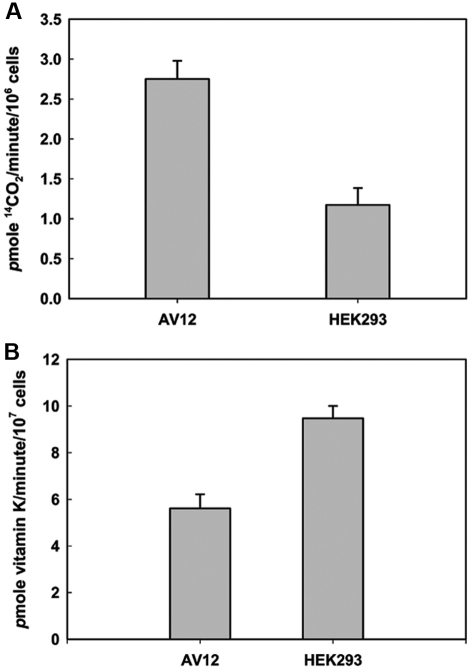

To understand the reason for the differences in carboxylation efficiency between HEK293 and AV12 cells, we tested the in vitro activity of the endogenous VKOR and GGCX in the 2 cell types (Figure 5). We found that GGCX activity was approximately 3-fold higher in AV12 cells than in HEK293 cells. However, the in vitro VKOR activity of AV12 cells was approximately 66% of that observed in HEK293 cells. The difference between these 2 cell lines in endogenous VKOR activity correlates with our observation that AV12 cells produce less carboxylated reporter protein than do HEK293 cells. The endogenous GGCX and VKOR activity results agree with our previous observation35 that the rate of KH2 production rather than the rate of vitamin K–dependent carboxylation can be the rate-limiting step for in vivo vitamin K–dependent protein carboxylation.

Figure 5.

Endogenous VKOR and GGCX activity in HEK293 and AV12 cells as measured by in vitro enzymatic activity assay. (A) Endogenous GGCX activity of 1 × 106 HEK293 or AV12 cells was determined as described in “GGCX activity assay” using FLEEL as a substrate in the presence of propeptide. (B) Endogenous VKOR activity of 1 × 107 HEK293 or AV12 cells was determined as described in “VKOR activity assay” using K1(25) as the HPLC internal standard.

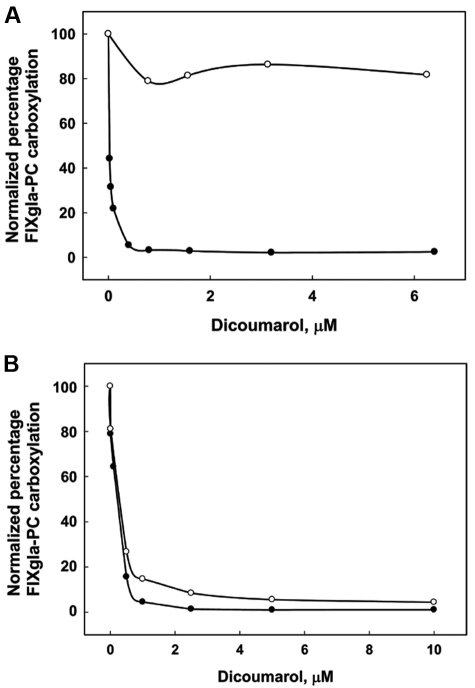

Contribution of NQO1 to vitamin K reduction

Dicoumarol-sensitive NQO1 was originally isolated as a vitamin K reductase.36 Subsequently, it was reported that NQO1 can accomplish the 2-electron reduction of vitamin K to KH2 in vitro.11,37 Therefore, we examined the contribution of NQO1 to the conversion of vitamin K to KH2 in vivo by adding increasing concentrations of dicoumarol to the cell-culture medium with either vitamin K or KO as a substrate in HEK293 cells. Figure 6A shows that, as with warfarin, dicoumarol significantly inhibited reporter protein carboxylation when KO was the vitamin K source. This result demonstrates that dicoumarol is a strong inhibitor for VKOR, as expected. However, when cells were fed vitamin K, only minimal inhibition was observed. Results from the in vitro assay show that the inhibition constant of dicoumarol for NQO1 was 0.5nM, whereas 1.6μM was required to reach 50% inhibition of NQO1 in the cell-based assay.38 When we treated the cells with 20μM dicoumarol, a level reported to almost completely inactivate overexpressed NQO1 in intact cells,38 60% of the reporter protein was carboxylated (data not shown). Lewis et al reported that cell viability decreases to 60% when incubated with 100μM dicoumarol for 48 hours.39 These results suggest that NQO1 contributes minimally to the reduction of vitamin K to KH2 in the vitamin K cycle. Therefore, another, still-unidentified dicoumarol/warfarin-insensitive enzyme must be the major antidotal enzyme that reduces vitamin K in HEK293 cells.

Figure 6.

Effect of dicoumarol on the carboxylation of the FIXgla-PC in HEK293 and AV12 cells. Increasing concentrations of dicoumarol were added to the cell-culture medium with either 11μM K (○) or 5μM KO (●) and incubated with HEK293 (A) or AV12 (B) cells for 48 hours. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the medium was measured by ELISA. The data are presented as percentages to make the first concentration points of vitamin K and KO coincide.

We then tested the effect of dicoumarol on reporter protein carboxylation in AV12 cells. Figure 6B shows that when KO was the vitamin K source, the inhibition of reporter protein carboxylation by dicoumarol was similar to that in HEK293 cells (Figure 6A). A significant difference between AV12 cells and HEK293 cells was observed when the cells were grown in the presence of vitamin K; in this case, dicoumarol completely inhibited reporter protein carboxylation in AV12 cells. Moreover, the inhibition curve was similar to that when KO was used as the substrate (Figure 6B). This supports the results shown in Figure 4A indicating that, unlike HEK293 cells, AV12 cells have very little antidotal enzyme. The ∼ 20% residual activity observed when vitamin K was used as the substrate (Figure 4A) may have been because of NQO1 activity, which is inhibited by dicoumarol but not by warfarin. These data suggest that NQO1 plays a limited role in converting vitamin K to KH2 in the vitamin K cycle in vivo.

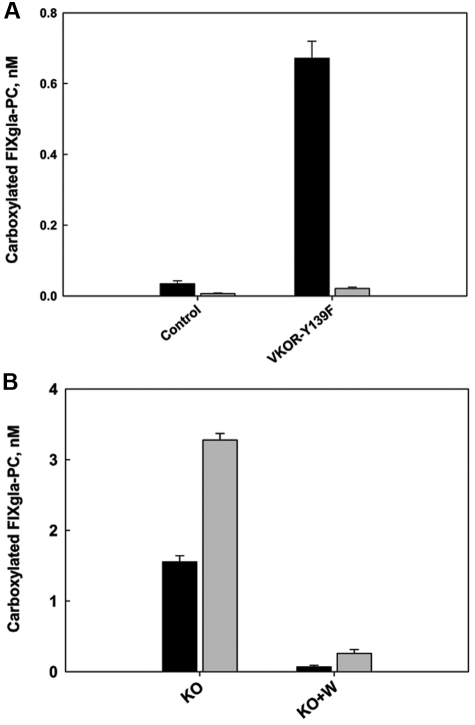

Contribution of VKOR to the reduction of vitamin K to KH2

Our results confirm that VKOR is responsible for the reduction of KO to vitamin K. To test the ability of VKOR to reduce vitamin K to KH2 in vivo, we mutated tyrosine 139 to phenylalanine (Y139F), which converts VKOR to a warfarin-resistant form.20 This permitted the inactivation of endogenous VKOR by warfarin while testing the in vivo function of the VKOR-Y139F.

We transiently expressed VKOR-Y139F in HEK293 and AV12 cells that stably expressed the FIXgla-PC. We grew cells transfected and not transfected with VKOR-Y139F in complete medium containing 5μM KO with 2μM warfarin. As shown in Figure 7A, 2μM warfarin inactivated the endogenous VKOR present in the nontransfected cells of both cell lines. Therefore, almost no carboxylated reporter protein was secreted into the medium (control). In cells transiently expressing VKOR-Y139F, significant amounts of carboxylated reporter protein were produced in HEK293 cells (∼ 20-fold increase compared with the control) but not in AV12 cells. We reasoned that this was because the transiently expressed VKOR-Y139F converted KO to vitamin K in the presence of warfarin. In HEK293 cells, the endogenous warfarin-resistant antidotal enzyme further reduced vitamin K to KH2 for the carboxylation reaction. Because there is very little antidotal enzyme present in AV12 cells, warfarin also inactivates the reduction of vitamin K to KH2 (Figure 4A). However, if VKOR were the major contributor to the conversion of vitamin K to KH2, AV12 cells transiently expressing the VKOR-Y139F mutant should produce significant amounts of carboxylated reporter protein, as observed in HEK293 cells. Therefore, this result indicates that the contribution of VKOR to the reduction of vitamin K to KH2 in vivo is small, which agrees with our previous in vitro results.23 In addition, these results suggest that in AV12 cells, a warfarin-sensitive enzyme different from VKOR converts vitamin K to KH2.

Figure 7.

Effect of the warfarin-resistant VKOR mutant on FIXgla-PC carboxylation. (A) The warfarin-resistant VKOR-Y139F mutant was transiently expressed in HEK293 (■) and AV12 cells ( ). Thirty hours after transfection, cells were cultured in medium containing 5μM KO and 2μM warfarin for 48 hours. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the medium was measured by ELISA. The control was the cell line transfected with empty vector, representing endogenous VKOR. (B) AV12 cells (■) or AV12 cells that were stably expressing the warfarin-resistant VKOR-Y139F mutant (

). Thirty hours after transfection, cells were cultured in medium containing 5μM KO and 2μM warfarin for 48 hours. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the medium was measured by ELISA. The control was the cell line transfected with empty vector, representing endogenous VKOR. (B) AV12 cells (■) or AV12 cells that were stably expressing the warfarin-resistant VKOR-Y139F mutant ( ) were cultured in medium containing 5μM KO (KO) or 5μM KO + 2μM warfarin (KO + W) for 48 hours. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the medium was measured by ELISA.

) were cultured in medium containing 5μM KO (KO) or 5μM KO + 2μM warfarin (KO + W) for 48 hours. The concentration of carboxylated FIXgla-PC in the medium was measured by ELISA.

An alternative explanation for why no carboxylated reporter protein was secreted from AV12 cells that transiently expressed VKOR-Y139F could be that VKOR-Y139F is not highly expressed in the cells or that the expressed protein is unable to convert KO to vitamin K. To clarify this, we stably expressed VKOR-Y139F in AV12 cells. The colony exhibiting the highest level of VKOR-Y139F expression was chosen for further study. As shown in Figure 7B, overexpression of VKOR-Y139F increased reporter protein carboxylation approximately 2-fold when KO was used as the substrate in the culture medium. This suggests that VKOR-Y139F is a functional protein that is able to reduce KO in AV12 cells. Warfarin also abolished reporter protein carboxylation in this cell line, which stably overexpressed VKOR-Y139F. This evidence further implies that VKOR has a limited ability to convert vitamin K to KH2 in vivo.

Discussion

Our initial goal in this study was to develop an in vivo assay that would allow us to study the function of enzymes involved in the vitamin K cycle and to identify other, perhaps unknown, enzymes that are important. Our results indicate that this assay is a good model system for these studies.

We could study the 2 reductions in the vitamin K cycle by feeding the cells either KO or vitamin K. Cells cultured in medium containing KO and warfarin produced significantly less carboxylated reporter protein (Figures 2–4). Because VKOR is the primary target of warfarin, this indicates that the in vivo reduction of KO is mainly carried out by VKOR. In addition, the fact that the cells produce a similar amount of carboxylated protein when fed vitamin K, even in the presence of warfarin, shows that there is a so-called antidotal enzyme in the HEK293 cells. This is important because the antidotal enzyme has yet to be identified.

The reduction of vitamin K to KH2 has been proposed to be carried out by 2 pathways,7,40 one accomplished by VKOR, which is sensitive to warfarin inhibition, and the other by NQO1, which is resistant to warfarin inhibition. Whether NQO1 is the antidotal enzyme for vitamin K reduction has been debated.6,11 To clarify the role of NQO1 in the vitamin K cycle, we tested the effect of dicoumarol, an inhibitor of NQO1, on reporter protein carboxylation. When vitamin K was used as the substrate, carboxylation of the reporter protein was decreased by only ∼ 20%. This result suggests that NQO1 is not the antidotal enzyme, which agrees with previous reports.6,15,16 Forthoffer et al described a membrane-bound, NQO1-like protein41 that could be a candidate for the warfarin/dicoumarol-insensitive pathway of vitamin K reduction. It is a dicoumarol-insensitive quinone reductase that reduces quinones by a 2-electron reduction and uses NADH more efficiently than NAD(P)H as the reducing agent.

Unlike in HEK293 cells, warfarin inhibited FIXgla-PC carboxylation in AV12 cells when vitamin K was used as the substrate. High concentrations of vitamin K could not rescue the inhibition. Different cell types have different mechanisms of vitamin K uptake and metabolism, which could affect the amount of reporter protein carboxylation.42,43 However, in HEK293 cells, maximum carboxylation of FIXgla-PC occurs at 1μM, whereas in AV12 cells, it occurs at 2.5μM (Figures 3B and 4B, respectively). Therefore, it is unlikely that these 2 cell lines have significant differences in vitamin K uptake. Furthermore, we used a saturated concentration of vitamin K (11μM) in our experiments. This suggests that with vitamin K as a substrate, the different warfarin sensitivities of these 2 cells are likely because of a lack of antidotal enzyme in AV12 cells; it also implies that the majority of vitamin K reduction in AV12 cells is carried out by a warfarin-sensitive pathway.

There seems to be little doubt that VKOR can reduce vitamin K to KH2.2,23 However, our previous study with purified VKOR indicated that the rate of conversion of vitamin K to KH2 was considerably slower than the rate of the conversion of KO to vitamin K.23 In the present study, to test the contribution of VKOR to the reduction of vitamin K to KH2 in vivo, we expressed a warfarin-resistant VKOR mutant (Y139F). When fed KO in the presence of warfarin, HEK293 (Y139F) cells produced carboxylated reporter protein. However, under similar conditions, AV12 (Y139F) cells failed to produce significant carboxylated reporter protein. VKOR-Y139F is expressed and active in AV12 (Y139F) cells, because the amount of carboxylated reporter protein doubled in the absence of warfarin when these cells were fed KO. Therefore, only the HEK293 (Y139F) cells that have antidotal enzyme can support the complete vitamin K cycle in the presence of warfarin.

Because, in vitro, both KO to vitamin K and vitamin K to KH2 reactions of VKOR are inhibited by warfarin,22,23 the most straightforward conclusion from this result is that the in vivo function of VKOR is to convert KO to vitamin K and that a second enzyme is required to convert vitamin K to KH2.

A second implication of these results is that there must be a warfarin-sensitive enzyme other than VKOR that converts vitamin K to KH2 in AV12 cells. The existence of a second warfarin-sensitive enzyme is unexpected, because Cooper et al did a retrospective study using 550 000 SNPs from 181 patients and found that only polymorphisms in VKOR and cytochrome P450 2C9 affected warfarin dose requirements. Based on that result, they concluded that it was unlikely that another enzyme affecting warfarin sensitivity would be found.44 On the other hand, at present, polymorphisms in VKOR and cytochrome P450 2C9 combine to account for only 30%-60% of the variance in the stabilized warfarin dose distribution.45

One might speculate that the methods described in this study will be important for further studies of the vitamin K cycle. For example, cell utilization of different forms of vitamin K (menaquinones vs phylloquinones) may account for some of the hepatic and peripheral carboxylation differences in warfarin sensitivity and response to vitamin K as an antidote to warfarin.46 On the other hand, it is possible that the cells that do not respond to vitamin K treatment during warfarin poisoning may have lower levels of the warfarin-resistant vitamin K reductase (antidotal enzyme). In addition, there are indications that long-term warfarin therapy may cause unwanted effects of bone fracture and vascular calcification. These problems are apparently due to the inhibition of carboxylation of regulator proteins such as matrix gla protein (MGP) and the growth arrest specific gene 6 product (Gas-6).47–50 Our cell-based system will be useful in studying these and other questions relating to the vitamin K cycle.

In summary, we have established an in vivo assay system for the functional study of the vitamin K cycle. The 2-step reduction of vitamin K can be studied separately using this system by feeding the cells either KO or vitamin K. We present evidence of a warfarin-sensitive enzyme that converts vitamin K to KH2 that is different from VKOR and the warfarin-resistant antidotal enzyme. This antidotal enzyme for vitamin K reduction is probably not NQO1. Finally, we show that the main function of VKOR is to convert KO to vitamin K, not vitamin K to KH2.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL077740, HL048318, and HL06350 (to D.W.S.)

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.-K.T. designed and performed research, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; D.-Y.J. performed experimental work and analyzed the data; D.L.S. and D.W.S. designed research, supervised the study, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors critically reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Part of the results in this paper and the cell-based assay for studying the function of vitamin K cycle enzymes have been submitted for patent application. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Darrel W. Stafford, Department of Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3280; e-mail: dws@email.unc.edu.

References

- 1.Presnell SR, Stafford DW. The vitamin K–dependent carboxylase. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87(6):937–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oldenburg J, Marinova M, Muller-Reible C, Watzka M. The vitamin K cycle. Vitam Horm. 2008;78:35–62. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(07)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman PA, Sander EG. Vitamin K epoxide reductase: evidence that vitamin K dihydroquinone is a product of vitamin K epoxide reduction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;103(3):997–1005. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)90908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallin R, Hutson S. Vitamin K–dependent carboxylation. Evidence that at least 2 microsomal dehydrogenases reduce vitamin K1 to support carboxylation. J Biol Chem. 1982;257(4):1583–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardill SL, Suttie JW. Vitamin K epoxide and quinone reductase activities. Evidence for reduction by a common enzyme. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40(5):1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90493-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preusch PC, Smalley DM. Vitamin K1 2,3-epoxide and quinone reduction: mechanism and inhibition. Free Radic Res Commun. 1990;8(4-6):401–415. doi: 10.3109/10715769009053374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallin R. Vitamin K antagonism of coumarin anticoagulation. A dehydrogenase pathway in rat liver is responsible for the antagonistic effect. Biochem J. 1986;236(3):685–693. doi: 10.1042/bj2360685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fasco MJ, Principe LM. Vitamin K1 hydroquinone formation catalyzed by a microsomal reductase system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;97(4):1487–1492. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(80)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maerki F, Martius C. Vitamin K reductase, preparation and properties [in German]. Biochem Z. 1960;333:111–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasco MJ, Principe LM. Vitamin K1 hydroquinone formation catalyzed by DT-diaphorase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;104(1):187–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91957-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallin R, Gebhardt O, Prydz H. NAD(P)H dehydrogenase and its role in the vitamin K (2-methyl-3-phytyl-1,4-naphthaquinone)-dependent carboxylation reaction. Biochem J. 1978;169(1):95–101. doi: 10.1042/bj1690095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjornsson TD, Blaschke TF. Vitamin K1 disposition and therapy of warfarin overdose. Lancet. 1978;2(8094):846–847. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shearer MJ, Barkhan P. Vitamin K1 and therapy of massive warfarin overdose. Lancet. 1979;1(8110):266–267. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross D, Kepa JK, Winski SL, Beall HD, Anwar A, Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): chemoprotection, bioactivation, gene regulation and genetic polymorphisms. Chem Biol Interact. 2000;129(1-2):77–97. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brar SS, Kennedy TP, Whorton AR, et al. Reactive oxygen species from NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase constitutively activate NF-kappaB in malignant melanoma cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280(3):C659–C676. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong X, Gutala R, Jaiswal AK. Quinone oxidoreductases and vitamin K metabolism. Vitam Horm. 2008;78:85–101. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(07)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thijssen HH, Baars LG. Tissue distribution of selective warfarin binding sites in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42(11):2181–2186. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulrich MM, Knapen MH, Herrmann-Erlee MP, Vermeer C. Vitamin K is no antagonist for the action of warfarin in rat osteosarcoma UMR 106. Thromb Res. 1988;50(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(88)90171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price PA, Kaneda Y. Vitamin K counteracts the effect of warfarin in liver but not in bone. Thromb Res. 1987;46(1):121–131. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rost S, Fregin A, Ivaskevicius V, et al. Mutations in VKORC1 cause warfarin resistance and multiple coagulation factor deficiency type 2. Nature. 2004;427(6974):537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature02214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Chang CY, Jin DY, Lin PJ, Khvorova A, Stafford DW. Identification of the gene for vitamin K epoxide reductase. Nature. 2004;427(6974):541–544. doi: 10.1038/nature02254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin DY, Tie JK, Stafford DW. The conversion of vitamin K epoxide to vitamin K quinone and vitamin K quinone to vitamin K hydroquinone uses the same active site cysteines. Biochemistry. 2007;46(24):7279–7283. doi: 10.1021/bi700527j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu PH, Huang TY, Williams J, Stafford DW. Purified vitamin K epoxide reductase alone is sufficient for conversion of vitamin K epoxide to vitamin K and vitamin K to vitamin KH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(51):19308–19313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609401103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugo T, Mizuguchi J, Kamikubo Y, Matsuda M. Anti-human factor IX monoclonal antibodies specific for calcium ion-induced conformations. Thromb Res. 1990;58(6):603–614. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang M, Furie BC, Furie B. Crystal structure of the calcium-stabilized human factor IX Gla domain bound to a conformation-specific anti-factor IX antibody. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(14):14338–14346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan SC, Razzano P, Chao YB, et al. Characterization and novel purification of recombinant human protein C from three mammalian cell lines. Biotechnology (N Y) 1990;8(7):655–661. doi: 10.1038/nbt0790-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tishler M, Fieser LF, Wendler NL. Hydro, oxido and other derivatives of vitamin K1 and related compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 1940;62:2866–2871. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aktimur A, Gabriel MA, Gailani D, Toomey JR. The factor IX gamma-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) domain is involved in interactions between factor IX and factor XIa. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):7981–7987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gui T, Lin HF, Jin DY, et al. Circulating and binding characteristics of wild-type factor IX and certain Gla domain mutants in vivo. Blood. 2002;100(1):153–158. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tie JK, Zheng MY, Hsiao KL, Perera L, Stafford DW, Straight DL. Transmembrane domain interactions and residue proline 378 are essential for proper structure, especially disulfide bond formation, in the human vitamin K–dependent gamma-glutamyl carboxylase. Biochemistry. 2008;47(24):6301–6310. doi: 10.1021/bi800235r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris DP, Soute BA, Vermeer C, Stafford DW. Characterization of the purified vitamin K–dependent gamma-glutamyl carboxylase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(12):8735–8742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thijssen HH, Soute BA, Vervoort LM, Claessens JG. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) warfarin interaction: NAPQI, the toxic metabolite of paracetamol, is an inhibitor of enzymes in the vitamin K cycle. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92(4):797–802. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schurgers LJ, Shearer MJ, Hamulyak K, Stocklin E, Vermeer C. Effect of vitamin K intake on the stability of oral anticoagulant treatment: dose-response relationships in healthy subjects. Blood. 2004;104(9):2682–2689. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowenthal J, Taylor JD. A method for measuring the activity of compounds with an activity like vitamin K against indirect anticoagulants in rats. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1959;14(1):14–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00922.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun YM, Jin DY, Camire RM, Stafford DW. Vitamin K epoxide reductase significantly improves carboxylation in a cell line overexpressing factor X. Blood. 2005;106(12):3811–3815. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martius C. On the biochemistry of vitamin K [in German]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1963;93:1264–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martius C, Ganser R, Viviani A. The enzymatic reduction of K-vitamins incorporated in the membrane of liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1975;59(1):13–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee YY, Westphal AH, de Haan LH, Aarts JM, Rietjens IM, van Berkel WJ. Human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase inhibition by flavonoids in living cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis A, Ough M, Li L, et al. Treatment of pancreatic cancer cells with dicumarol induces cytotoxicity and oxidative stress. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(13):4550–4558. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallin R, Patrick SD, Martin LF. Vitamin K1 reduction in human liver. Location of the coumarin-drug-insensitive enzyme. Biochem J. 1989;260(3):879–884. doi: 10.1042/bj2600879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forthoffer N, Gomez-Diaz C, Bello RI, et al. A novel plasma membrane quinone reductase and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 are upregulated by serum withdrawal in human promyelocytic HL-60 cells. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2002;34(3):209–219. doi: 10.1023/a:1016035504049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shearer MJ, Newman P. Metabolism and cell biology of vitamin K. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100(4):530–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suhara Y, Murakami A, Nakagawa K, Mizuguchi Y, Okano T. Comparative uptake, metabolism, and utilization of menaquinone-4 and phylloquinone in human cultured cell lines. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14(19):6601–6607. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooper GM, Johnson JA, Langaee TY, et al. A genome-wide scan for common genetic variants with a large influence on warfarin maintenance dose. Blood. 2008;112(4):1022–1027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamali F, Wynne H. Pharmacogenetics of warfarin. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:63–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.070808.170037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spronk HM, Soute BA, Schurgers LJ, Thijssen HH, De Mey JG, Vermeer C. Tissue-specific utilization of menaquinone-4 results in the prevention of arterial calcification in warfarin-treated rats. J Vasc Res. 2003;40(6):531–537. doi: 10.1159/000075344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danziger J. Vitamin K–dependent proteins, warfarin, and vascular calcification. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1504–1510. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00770208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schurgers LJ, Cranenburg EC, Vermeer C. Matrix Gla-protein: the calcification inhibitor in need of vitamin K. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100(4):593–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato Y, Honda Y, Jun I. Long-term oral anticoagulation therapy and the risk of hip fracture in patients with previous hemispheric infarction and nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29(1):73–78. doi: 10.1159/000256650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murshed M, Schinke T, McKee MD, Karsenty G. Extracellular matrix mineralization is regulated locally; different roles of 2 gla-containing proteins. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(5):625–630. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]