Abstract

A 78-year-old Hispanic woman with a medical history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidaemia and dyspepsia presented to a gastrointestinal clinic complaining of a small amount of rectal bleeding following bowel movements for 6 months. Colonoscopy demonstrated a 3×3 cm submucosal rectal mass. Pathological analysis revealed ulcerated colonic mucosa with diffuse proliferation suggestive of a lymphoproliferative process. Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry of the specimen supported a diagnosis of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. The patient was treated with amoxicillin, clarithromycin and lansoprazole for 2 weeks. A C-14 urea breath test confirmed eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Repeat colonoscopy showed no regression of the tumour. The patient received external beam radiation treatment. Subsequent positron emission tomography/CT scans demonstrated no evidence of viable tumour tissue and no regional or distant metastasis. Follow-up sigmoidoscopy with biopsy revealed no evidence of lymphoma.

Background

The concept of lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) was initially introduced by Isaacson and Wright in 1983.1 MALT lymphomas result from the malignant transformation of B cells from the marginal zone of MALT. In some cases, these lymphomas may result from MALT that exists physiologically, but in the majority of cases they arise from MALT that is acquired in sites of inflammation triggered by either infectious or autoimmune processes. In general, MALT lymphomas account for approximately 5% of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. These lymphomas can arise in a variety of sites and are found most frequently in the gastrointestinal tract. However, they can arise in a multitude of extraintestinal organs, including the salivary gland, thyroid gland, breast, lung, bladder, skin and orbit.2

In the gastrointestinal tract, the stomach is the most common site with MALT lymphomas accounting for approximately 50% of all gastric lymphomas.3 Numerous studies have confirmed the significant role of Helicobacter pylori in the development of gastric MALT lymphoma. Consequently, eradication of H pylori has been extensively examined as first-line treatment for gastric MALT lymphoma with various studies documenting successful elimination of low-grade lymphomas after treatment with antibiotics.4 5

However, the association between H pylori and MALT lymphoma arising outside of the stomach is less understood. When MALT does arise in the colon, the rectum is the most common site—accounting for approximately 60% of cases.6 Most cases of extragastric MALT-associated lymphoma are treated with either H pylori antimicrobial treatment or a combination of surgery and chemo-radiation. This case is unique in that the extragastric MALT-like lymphoma, while unresponsive to H pylori treatment, responded to radiation treatment and did not require surgical resection or chemotherapy.

Case presentation

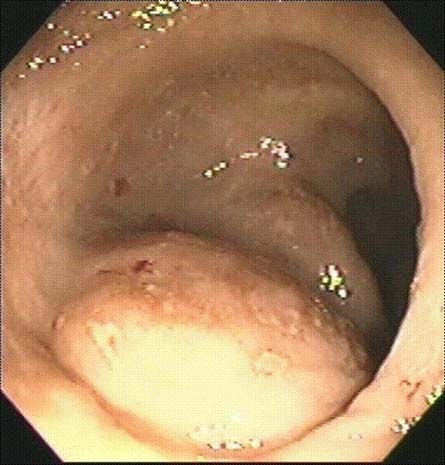

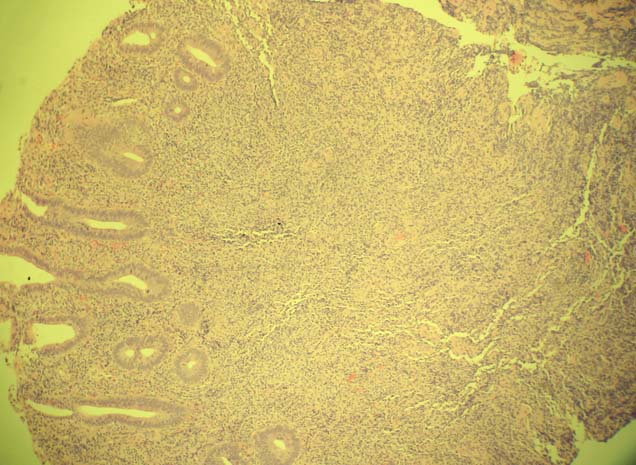

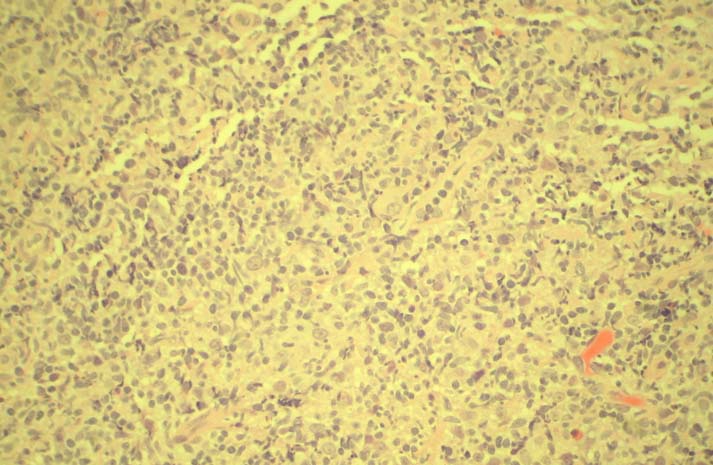

The patient was a 78-year-old Hispanic woman with a medical history significant for osteoarthritis, hyperlipidaemia and dyspepsia who presented to our gastroenterology clinic complaining of a small amount of rectal bleeding following bowel movements for 6 months. There was no obvious bleeding on exam. There was no family history of colon cancer and the social history was non-contributory. The patient subsequently underwent a colonoscopy, which demonstrated a 3×3 cm submucosal rectal mass (figure 1). The pathology report revealed ulcerated colonic mucosa with diffuse proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells suggestive of a lymphoproliferative process (figure 2, 3). The immunohistochemical stain was positive for CD20, BCL-2, CD45, CD79A and CD43. The stain was negative for CD10, BCL-1 and BCL6. Plasma cells were positive for κ and λ. Focal reactive T cells were positive for CD3, CD5 and CD43. Flow cytometric studies were performed on repeat rectal tissue biopsies, which demonstrated a monoclonal λ B cell population lacking CD5/CD10, confirming the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which showed a normal appearing squamocolumnar junction and mild gastric erythema. Random biopsies of the gastric erythema revealed severe chronic active gastritis, inflammatory atypia and the presence of H pylori. Pathologically, no H pylori organism could be identified in the rectal MALT tissue.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view: mass at colonoscopy.

Figure 2.

Low power view of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

Figure 3.

High power view of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

The patient was treated for 2 weeks with amoxicillin, clarithromycin and lansoprazole. A C-14 urea breath test performed subsequently confirmed eradication of H pylori. However, a repeat colonoscopy 2 months later showed no internal regression in the tumour and a repeat rectal biopsy continued to show diffuse infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells. A bone marrow biopsy was performed and revealed no evidence of lymphoma or any other malignant process.

The patient received external beam radiation treatment over the course of 2 months for a total dose of 45 Gy (figure 4). Subsequent to the radiation treatment, there was resolution of signal on repeat positron emission tomography (PET) scan. In addition, a PET/CT was performed, which demonstrated no evidence of viable tumour tissue and no regional or distant metastasis. After radiation treatment, the patient had occasional rectal bleeding. A repeat colonoscopy demonstrated rectal arteriovenous malformations and internal haemorrhoids without an active bleeding source. Rectal biopsy of the previous MALT lymphoma site demonstrated rectal mucosa with chronic inflammatory reactive changes and mucosal fibrosis; however, there was no evidence of residual atypical lymphocytes.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic view: area after external beam radiation.

Investigations

Colonoscopy demonstrated a 3×3 cm submucosal rectal mass. A pathology report revealed ulcerated colonic mucosa with diffuse proliferation suggestive of a lymphoproliferative process. Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry confirmed low-grade MALT-associated lymphoma.

Differential diagnosis

Adenocarcinoma of the rectum, infectious proctitis, inflammatory process—for example, ulcerative colitis.

Treatment

The patient received treatment with amoxicillin, clarithromycin and lansoprazole for 2 weeks. However, repeat colonoscopy showed no regression in the tumour. The radiation treatment led to eradication of the MALT-associated lymphoma.

Outcome and follow-up

Our patient has remained tumour free for approximately 3 years based on sigmoidoscopy with biopsy as well as PET scans.

Discussion

Although it is widely accepted that the development of gastric MALT lymphoma is related to antigen stimulation by persistent H pylori infection, the relation between rectal MALT lymphoma and H pylori infection remains poorly understood. In the literature, limited reports of rectal MALT lymphoma and its treatment are available. There have been some case reports of response of colorectal MALT lymphoma following eradication of H pylori. Raderer et al3 presented a case of a patient with gastric and colonic MALT lymphoma in whom the colonic lymphoma regressed completely in response to successful eradication of H pylori. Matsumoto et al5 presented a case of regression of rectal MALT following eradication of H pylori. However, there have been other cases where the elimination of H pylori resulted in no change in the progression of MALT lymphoma. Studies have suggested there may be other microorganisms involved in the pathogenesis of extragastric MALT lymphoma—for example, Campylobacter jejuni in small intestinal lymphoma, Chlamydia psittaci in orbital lymphoma and Borrelia burgdorferi in cutaneous lymphoma.9 Thus far, identity of the organism, if any, which is responsible for the development of extragastric MALT lymphoma, is unknown.

Our case is unconventional regarding its method of management. While radiotherapy alone has been described in the management of rectal MALT lymphoma, the typical treatment for rectal MALT lymphoma includes endoscopic mucosal resection, surgical excision, chemotherapy with radiation and, more recently, the addition of anti CD-20 chimeric monoclonal antibody treatment in cases of relapse.6 As described earlier, treatment of rectal-associated MALT lymphoma with antibiotics is controversial.4 7 8 10

Learning points.

-

▶

While MALT-associated lymphoma is most commonly found in the stomach, it can also occur in extragastric sites—for example, the small intestine, colon and rectum, kidney, orbits, thyroid and breast tissue.

-

▶

While H pylori infection is believed to be integral to the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma, the association of H pylori and extragastric MALT lymphoma is controversial.

-

▶

When MALT-associated lymphoma is found in the large bowel, the rectum is the most common location.

-

▶

Treatment for extra-gastric MALT-associated lymphoma is variable. Occasionally, antimicrobial treatment against H pylori is sufficient; however, a combination of surgical excision, endoscopic mucosal resection, chemotherapy or radiation is usually required.

-

▶

Rarely, external beam radiation is sufficient for treatment.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: A distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer 1983;52:1410–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlawat S, Kanber Y, Charabaty-Pishvaian A, et al. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma occurring in the rectum: a case report and review of the literature. South Med J 2006;99:1378–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raderer M, Pfeffel F, Pohl G, et al. Regression of colonic low grade B cell lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut 2000;46:133–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamada M, Kawahara H, Shiroeda H. Successful rituximab monotherapy for API2-MALT1 fusion positive mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the transverse colon in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008;43:761–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsumoto T, Iida M, Shimizu M. Regression of mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma of rectum after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 1997;350:115–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grünberger B, Wöhrer S, Streubel B, et al. Antibiotic treatment is not effective in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori suffering from extragastric MALT lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1370–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus Foo, Chao MW, Gibbs P, et al. Successful treatment of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue of the rectum with radiation therapy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51(11):1719–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka S, Ohta T, Kaji E, et al. EMR of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the rectum. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:956–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong GL, Lee S, Han SW, et al. A case of multiple mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the colon identified as simple mucosal discoloration. J Kor Med Sci 2005;20:325–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakase H, Okazaki K, Ohana M, et al. The possible involvement of micro-organisms other than Helicobacter pylori in the development of rectal MALT lymphoma in H. pylori-negative patients. Endoscopy 2002;34:343–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]