Abstract

Most genome transactions are favored by DNA (−) torsional stress, i.e., unconstrained unwinding or supercoiling of DNA. A question raised here is whether DNA (+) torsional stress, which precludes DNA unwinding, could also be relevant in gene regulation. Such DNA twist dynamics could be determined by chromatin architecture.

Key words: DNA topology, topoisomerase, silencing, DNA twist, DNA unwinding, positive supercoil, chromatin architecture

In 1992, Gartenberg and Wang reported that (+) supercoiling of DNA greatly diminishes mRNA synthesis in budding yeast.1 This former study has been recently extended by Joshi et al. who examined the effects of DNA overtwisting across the yeast transcriptome.2 The results confirmed that DNA (+) torsional stress produces a massive impairment of transcription, by affecting over 80% of yeast genes. Intriguingly, those genes that escaped from the transcription stall were all located at less than 100 kb from the chromosomal ends. This positional effect, which was independent of telomeric silencing, suggested that DNA torsional stress dissipates near chromosomal ends, either by axial rotation of DNA inside the telomeric region or by revolving the full telomere. Both possibilities have implications for the conformation and nuclear organization of telomeric chromatin. The gradual escape from the transcription stall, which was identical in all the chromosomal arms, suggested also that kinetic restrictions to DNA twist diffusion, rather than tight topological domains, suffice to confine DNA torsional stress across eukaryotic chromatin. Besides the above inferences, these studies also raised another issue: the plausible role of DNA (+) torsional stress to modulate gene expression.

In the above experiments, DNA (+) torsional stress was induced in yeast cells by enforcing an unbalanced relaxation of the twin domains of (+) and (−) supercoiling produced in transactions that demand axial rotation of the DNA, such as gene transcription.3 Asymmetric relaxation is accomplished by expressing E. coli topoisomerase I [that relaxes (−) DNA supercoiling] in yeast cells deprived of their eukaryotic topoisomerase I and II activities [that relax both (+) and (−) DNA supercoiling]. With these conditions, intracellular DNA reaches supercoiling densities above +0.04,4 which means that the linking number of the double helix is >4% higher to that in the relaxed state (linking number of relaxed DNA increases 1 unit every 10.5 bp). Since typical nucleosomal organization constrains ∼1 negative helical turn of DNA per nucleosome (i.e., linking number decreases 1 unit every 200 bp), DNA supercoiling density in eukaryotic chromatin is about −0.05 (i.e., linking number is reduced 5% relative to relaxed state). Therefore, to change DNA supercoiling density from −0.05 to +0.04, average DNA linking number had to increase by 9%, which means introducing ∼1 overtwisting turn every 100 bp. Remarkably, histones are not displaced from the in vivo overtwisted DNA. Yeast minichromosomes regained their native nucleosomal organization when (+) torsional stress accumulated in vivo was relaxed with topoisomerases in vitro.4 This observation is consistent with in vitro studies that had revealed the extraordinary elasticity and plasticity of chromatinized DNA to accommodate (+) torsional stress.5 Unwrapping of nucleosomal DNA, flipping the nucleosome entry and exit DNA crossing, or inducing a nucleosome-reversome transition, in which the histone path for DNA changes its chirality to constrain one (+) DNA helical turn per nucleosome, allow eukaryotic chromatin to accommodate DNA supercoiling densities above +0.05 without bucking plectoneme supercoils.5,6

Although the supercoiling density +0.04 reached by manipulating cellular topoisomerases does not reflect a physiological condition, this value gives an estimate of the torsion against which DNA-revolving ensembles (i.e., RNA polymerases) are able to operate in vivo. At some higher degree of DNA overtwisting, transcription should become impracticable, either because RNA elongation complexes are stalled or because transcription initiation cannot be settled. To this regard, Gartenberg and Wang observed a decrease of RNA polymerase density along the genes under (+) torsional stress,1 and Joshi et al. noticed that the gradual escape of genes located at the chromosome flanks was independent of their transcription orientation (inward or outward the chromosomal end).2 Both observations indicated that (+) torsional stress inhibited transcription initiation, rather than transcription elongation. This conclusion can be reasoned given the DNA topology alterations associated to the initiation process. After binding of RNA polymerase holoenzyme (RNAP) to promoter DNA, RNAP unwinds 12–14 DNA base pairs surrounding the transcription start site to yield a catalytically competent RNAP-promoter open complex. Promoter unwinding and the stability of the open complex highly depends on the DNA torsional state.7 In the subsequent step, RNA synthesis begins by engaging in several abortive cycles of synthesis and release of short RNA segments. Each cycle proceeds through a DNA-scrunching mechanism and eventually, the elastic energy associated to a polymerization of >10 RNA nucleotides allows RNAP to break its interactions with promoter elements and enter into processive RNA synthesis as an RNAP-DNA elongation complex.8,9 The torsional state of DNA might affect both the formation of the RNAP open complex and for the RNAP escape from the promoter, which requires extra unwinding of the initial DNA bubble.

Given the efficiency of induced DNA (+) torsional stress to stall in vivo transcription, one could ask now whether mechanisms that preclude DNA unwinding could operate in physiological conditions to regulate gene expression. Such possibility is hard to envisage due to the prevalence of DNA (−) supercoiling in genome biology. Bacterial chromosomes are organized into topological domains, in which average DNA supercoiling density ∼−0.06 is partially constrained by structural proteins.10,11 Unconstrained DNA (−) torsional stress results from topoisomerase activities relaxing positive (DNA gyrase and topo IV) and negative (topo I and topo IV) torsional waves generated during DNA tracking processes and from the unique contribution of DNA gyrase that can catalyze per se (−) supercoiling of DNA.12,13 The unconstrained DNA (−) torsional stress found in bacterial chromosomes is tuned to regulate transcriptional activity and its relaxation results in broad changes of gene expression.14,15 In eukaryotic chromosomes, DNA (−) supercoiling density comparable to that found in bacteria is largely constrained by the nucleosome organization of chromatin and, therefore, no significant amount of DNA torsional stress is detected.16 Unlike bacteria, there is no evidence of a gyrase-like activity catalyzing supercoiling of DNA. Instead, the abundant topoisomerases I and II appear to relax promptly the (+) and (−1) supercoiling generated by DNA revolving processes. Therefore, nucleosome assembly and disassembly (with the concomitant constrain or release of ∼1 negative helical turn of DNA) and sequence-specific transitions of the B-DNA conformation had been for long envisioned as the eukaryotic mechanism for generating and modulating local levels of DNA (−) torsional stress.17 This former conception, however, is only a small part of the equation that determines the torsional state of DNA. As indicated below, chromatin architecture provides many possibilities to favor (or disfavor) local unwinding of DNA: by buffering torsional stress, by modulating DNA twist diffusion and by regulating topoisomerase activities.

The extraordinary plasticity and elasticity of chromatin to accommodate (+) torsional stress is so far the best indicator of its occurrence in physiological conditions.5 The response of chromatin architecture to DNA torsional stress can be tuned with the relative contributions of nucleosomal and linker DNA regions and their corresponding protein dosages. Histone composition and their biochemical modifications can deviate nucleosome conformational equilibriums concerning wrapping of DNA, juxtaposition of entry and exit DNA segments and potential nucleosome-reversome transition. Similarly, histone H1-like and non-histone proteins, which interact with linker DNA regions, can stabilize DNA crossings in order to constrain (−) supercoils (as broadly occurs in bacterial chromosomes),18 but could also do the same for (+) supercoil crossings in order to accommodate (+) torsional stress.

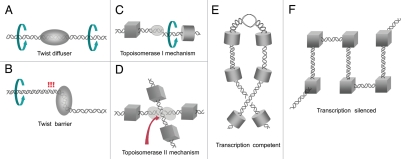

The dissipation of torsional stress by DNA twist diffusion also depends on chromatin architecture. In naked DNA, since axial spinning of the duplex can be very quick, DNA overtwisting waves are promptly diluted and have little impact on the local DNA conformation. In chromatin, instead, DNA spinning motion is severely hindered by the huge rotational drag inflicted by the many bends and molecular interactions of the duplex.19,20 Sharp DNA bends produced by numerous transcription factors and tight juxtaposition angles between entry and exit nucleosomal DNA segments can be used to establish permanent or kinetic barriers to axial rotation of DNA. Other elements that regulate high order folding of chromatin domains, such as CTCF,21 could also achieve their functional effects by establishing barriers to axial spinning of DNA. The entrapment and release of DNA overtwisting waves can be then specified by chromatin architectures that modulate DNA twist diffusion (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Role of chromatin architecture to determine the torsional state of DNA. Spinning motion of DNA is severely hindered by the rotational drag of chromatin. Accordingly, entrapment and release of DNA overtwisting waves at specific loci can be specified by chromatin elements that facilitate (A) or delay (B) DNA twist diffusion. Eukaryotic topoisomerase I relieves torsional stress by transiently cleaving one strand of the duplex and allowing its rotation in either direction around the uncleaved strand. Therefore, chromatin configurations that preclude axial rotation of DNA would be immune to relaxation with the topoisomerase I mechanism (C). Topoisomerase II removes supercoil crossings by transporting one segment of duplex DNA through a transient double-strand break in another. Hence, configurations that neglect proper DNA juxtaposition would be immune to relaxation by topoisomerase II (D). Chromatin structure could modulate then gene expression by setting architectures that favor or disfavor local unwinding of DNA, independently to global condensation or decondensation states. A conformation that facilitates DNA twist diffusion and topoisomerase activities would be transcriptionally competent (E). Conversely, architectures that block DNA twist diffusion and preclude topoisomerase mechanisms would be transcriptionally silenced (F). Solid blocks illustrate any chromatin element that, by bending the axial trajectory of the duplex or by interacting with other subcellular structures, determines the dynamics of DNA twist diffusion and DNA segment juxtaposition. Cylindrical and cubical blocks represent elements that allow and preclude axial rotation of DNA, respectively.

The specificity of topoisomerase activities is another potential determinant of local levels of DNA torsional stress. In eukaryotic cells, topoisomerase I relieves torsional stress by transiently cleaving one strand of the duplex and allowing its rotation in either direction around the uncleaved strand, and topoisomerase II removes supercoil crossings by transporting one segment of duplex DNA through a transient double-strand break in another (Fig. 1C and D).12,13 Both enzymes relax (+) and (−) torsional stress generated during intracellular DNA transactions and are able to compensate for each other in this task.22,23 However, little is known about how topoisomerases are regulated and about their potential specificity to remove (or perhaps generate) DNA torsional stress. To this regard, in vitro studies have uncovered that topoisomerase II relaxes DNA (+) supercoiling in native chromatin much faster that topoisomerase I.3

Therefore, topoisomerase II could have a main role removing DNA torsional stress ahead of DNA traversing complexes. In turn, topoisomerase I could play a dominant role relaxing (−) torsional stress behind transcribing ensembles, given that the formation of R-loop has been recently found markedly increased in yeast Δtop1 mutants.24,25 These observations suggest that chromatin architecture could modulate local levels of torsional stress by directing topoisomerase activities. The DNA strand-rotation mechanism of topoisomerase I could be more efficient behind the RNA polymerase, where chromatin is unfolded and axial rotation of the duplex can be fast. The DNA cross-inversion mechanism of topoisomerase II could be facilitated ahead the RNA polymerase, where chromatinized DNA stalls twist diffusion but favors the juxtaposition of DNA segments. Accordingly, configurations that preclude axial rotation of DNA would be immune to relaxation with topoisomerase I activity and configurations that neglect proper DNA juxtaposition angles or distances would be immune to relaxation by topoisomerase II.

The potential capacity of chromatin to either buffer, constrain, dilute or stack DNA torsional stress, as well as to control its relaxation by topoisomerases, could be exploited to preclude DNA unwinding for critical aspects of the genome biology. For instance, DNA (+) torsional stress generated ahead replications forks can be partially relaxed by topoisomerases but equally allowed to diffuse forward with the purpose to avoid unwanted transcription initiation of downstream genes. DNA (+) torsional stress could be also relevant in the establishment of transcriptional silencing. So far, silencing is mechanistically explained by the linear spread of proteins that condensate chromatin and impede the access of transcriptional machinery to DNA. Yet, apparent condensed-decondensed states of chromatin do not always correlate to the transcription capability of embedded genes.26 Perhaps a more subtle mechanism for silencing is reshaping chromatin in a conformation that disfavors DNA unwinding. Namely, silencing proteins, rather than compacting chromatin, could be just setting a periodic architecture that blocks DNA twist diffusion or precludes topoisomerase activity (Fig. 1E and F).

To test the above, suitable techniques to examine the twist dynamics of intracellular DNA should be developed. One possibility is psoralen-DNA photobinding probability, which can be used genomewide to compare regional levels of DNA torsional stress.27 Another strategy is the use of site-specific recombination for excising chromosomal regions as a covalently closed DNA rings.28 Yet, the DNA linking number of excised circles does not inform about local DNA twist and the excision reactions can be biased by the topology of the targeted region (i.e., recombination might not be efficient in overtwisted DNA). An ideal procedure would be capturing DNA conformational transitions induced by torsional stress. This approach has shown the dynamics of DNA (−) torsion generated during in vivo transcription.29 Unfortunately, no distinctive transitions of the DNA appear likely to be driven by physiological levels of (+) torsional stress. In this case, capturing its associated chromatin conformations could be the alternative (i.e., nucleosome-reversome transition). At some point, we should not be surprised to find out that, in the chromosomal landscape dominated by DNA (−) supercoils, DNA overtwisting also plays a role in regulating genome transactions.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Spanish grants BFU2008-00366, AGAUR 2009 SGR01222 and by Xarxa de Referencia en Biotecnologia de la Generalitat de Catalunya.

References

- 1.Gartenberg MR, Wang JC. Positive supercoiling of DNA greatly diminishes mRNA synthesis in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11461–11465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi R, Piña B, Roca J. Positional dependence of transcriptional inhibition by DNA torsional stress in yeast chromosomes. EMBO J. 2010;29:740–748. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu LF, Wang JC. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salceda J, Fernandez X, Roca J. Topoisomerase II, not topoisomerase I, is the proficient relaxase of nucleosomal DNA. EMBO J. 2006;25:2575–2583. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavelle C, Victor JM, Zlatanova J. Chromatin fiber dynamics under tension and torsion. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:1557–1579. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bancaud A, Wagner G, Conde ESN, Lavelle C, Wong H, Mozziconacci J, et al. Nucleosome chiral transition under positive torsional stress in single chromatin fibers. Mol Cell. 2007;27:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revyakin A, Ebright RH, Strick TR. Promoter unwinding and promoter clearance by RNA polymerase: Detection by single-molecule DNA nano-manipulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4776–4780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307241101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapanidis AN, Margeat E, Ho SO, Kortkhonjia E, Weiss S, Ebright RH. Initial transcription by RNA polymerase proceeds through a DNA-scrunching mechanism. Science. 2006;314:1144–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.1131399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tchernaenko V, Halvorson HR, Kashlev M, Lutter LC. DNA bubble formation in transcription initiation. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1871–1884. doi: 10.1021/bi701289g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinden RR, Pettijohn DE. Chromosomes in living Escherichia coli cells are segregated into domains of supercoiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:224–228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postow L, Hardy CD, Arsuaga J, Cozzarelli NR. Topological domain structure of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1766–1779. doi: 10.1101/gad.1207504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Champoux JJ. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang JC. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerase: molecular perspective. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:430–449. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peter BJ, Arsuaga J, Breier AM, Khodursky AB, Brown PO, Cozzarelli NR. Genomic transcriptional response to loss of chromosomal supercoiling in Escherichia coli. Genome Biol. 2004;5:87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vijayan V, Zuzow R, O'Shea EK. Oscillations in supercoiling drive circadian gene expression in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22564–22568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912673106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinden RR, Carlson JO, Pettijohn DE. Torsional tension in the DNA double helix measured with trimethylpsoralen in living E. coli cells: analogous measurements in insect and human cells. Cell. 1980;21:773–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kouzine F, Levens D. Supercoil-driven DNA structures regulate genetic transactions. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4409–4423. doi: 10.2741/2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. A common topology for bacterial and eukaryotic transcription initiation? EMBO Rep. 2007;8:147–151. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson P. Transport of torsional stress in DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14342–14347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stupina VA, Wang JC. DNA axial rotation and the merge of oppositely supercoiled DNA domains in Escherichia coli: effects of DNA bends. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8608–8613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402849101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohlsson R, Bartkuhn M, Renkawitz R. CTCF shapes chromatin by multiple mechanisms: The impact of 20 years of CTCF research on understanding the workings of chromatin. Chromosoma. 2010;119:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s00412-010-0262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uemura T, Yanagida M. Isolation of type I and II DNA topoisomerase mutants from fission yeast: single and double mutants show different phenotypes in cell growth and chromatin organization. EMBO J. 1984;3:1737–1744. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saavedra RA, Huberman JA. Both DNA topoisomerases I and II relax 2 micron plasmid DNA in living yeast cells. Cell. 1986;45:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90538-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Hage A, French SL, Beyer AL, Tollervey D. Loss of Topoisomerase I leads to R-loop-mediated transcriptional blocks during ribosomal RNA synthesis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1546–1558. doi: 10.1101/gad.573310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.French SL, Sikes ML, Hontz RD, Osheim YN, Lambert TE, El Hage A, et al. Distinguishing the roles of Topoisomerase I and II in relief of transcription-induced torsional stress in yeast rDNA genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:482–489. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00589-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng TH, Gartenberg MR. Yeast heterochromatin is a dynamic structure that requires silencers continuously. Genes Dev. 2000;14:452–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bermúdez I, García-Martínez J, Pérez-Ortín JE, Roca J. Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal DNA topology by means of psoralen-DNA photobinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:182. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gartenberg MR, Wang JC. Identification of barriers to rotation of DNA segments in yeast from the topology of DNA rings excised by an inducible site-specific recombinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10514–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kouzine F, Sanford S, Elisha-Feil Z, Levens D. The functional response of upstream DNA to dynamic supercoiling in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:146–154. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]