Abstract

Objective

To evaluate association with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) of 295 variants in 39 genes central to metabolic insulin signaling and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) regulation, followed by replication efforts.

Design

Case-control association study, with discovery and replication cohorts.

Setting

Subjects were recruited from reproductive endocrinology clinics, controls were recruited from communities surrounding the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Erasmus Medical Center.

Patients

273 cases with PCOS and 173 controls in the discovery cohort; 526 cases and 3585 controls in the replication cohort. All subjects were Caucasian.

Interventions

Phenotypic and genotypic assessment.

Main Outcome Measures

295 SNPs, PCOS status.

Results

Several SNPs were associated with PCOS in the discovery cohort. Four insulin receptor (INSR) SNPs and three insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) SNPs associated with PCOS (P<0.05) were genotyped in the replication cohort. One INSR SNP (rs2252673) replicated association with PCOS. The minor allele conferred increased odds of PCOS in both cohorts, independent of body mass index (BMI).

Conclusions

A pathway-based, tagging SNP approach allowed us to identify novel INSR SNPs associated with PCOS, one of which confirmed association in a large replication cohort.

Keywords: PCOS, INSR, replication, SNP

Introduction

Insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia are frequent findings in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), affecting ~70% of cases (1). The fact that insulin-sensitizing agents ameliorate features of PCOS points to insulin resistance as a key pathophysiologic factor (2).

Not only is PCOS itself heritable, but within PCOS, insulin resistance is under significant genetic control (3). First degree relatives of women with PCOS exhibit an increased prevalence of insulin resistance, whether or not they have PCOS (4). For these reasons, some of the earliest candidate genes examined for PCOS were components of the insulin signaling pathway (5). However, insulin signaling, which starts with insulin binding to the insulin receptor (INSR) on the cell surface, is a complex system that interacts with other signaling pathways (6). INSR initiates metabolic effects (e.g. stimulation of glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis) via two main pathways, the phosphatidylinositol-3 (PI3) kinase cascade and the Cbl/CAP pathway (7); it also promotes cell proliferation via the mitogenic MAP kinase cascade. These are the best-understood immediate systems activated by the INSR. Given the considerable number of components of these systems, insulin signaling pathways have been incompletely examined to date. Examples of studied genes include AKT2, INSR, IRS1, IRS2, GSK3B, PTP1B, PPP1R3, and SORBS1 (8).

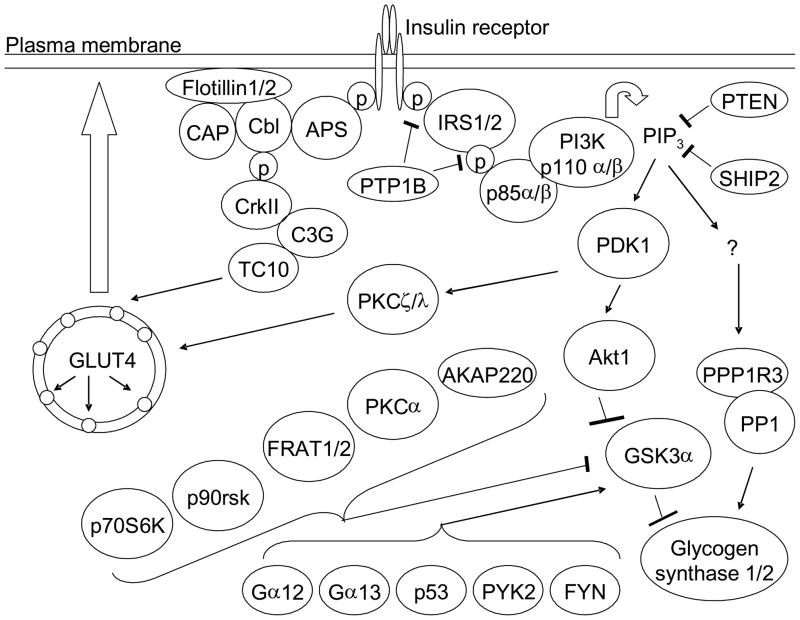

What has been needed is an analysis that considers all of the key components of the insulin signaling pathway, using a tagging SNP approach to encompass the majority of genetic variation across the target regions. Advances in high-throughput genotyping have made this possible. Therefore, to fully interrogate the insulin signaling pathway for susceptibility loci for PCOS, we genotyped the INSR gene plus 27 genes coding for pathway components related to metabolic effects (PI3-kinase and CAP/Cbl pathways) (Figure 1). We also genotyped 11 genes that have been described as regulators of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (9), given our prior genetic and physiologic results implicating this factor and its upstream regulator AKT2 in PCOS (10–12). The genes with the most significant SNPs associated with PCOS in the discovery phase were INSR and IRS2. Therefore, four SNPs in INSR and three SNPS in IRS2 were genotyped and analyzed in a larger replication cohort. One of the INSR SNPs replicated association with PCOS.

Figure 1.

Metabolic insulin signaling pathway genes genotyped in the discovery cohort. The protein products of the thirty nine genes that were genotyped in the discovery cohort are indicated. Names containing a slash indicate two isoforms encoded by two different genes. p = phosphate group. IP3 = phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Phenotyping

Discovery cohort

We studied 275 unrelated White PCOS patients and 173 White control women recruited at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). Study subjects were premenopausal, non-pregnant, on no hormonal therapy, including oral contraceptives or insulin-sensitizing agents, for at least three months, and met 1990 NIH criteria for PCOS (13). Parameters for defining hirsutism, hyperandrogenemia, ovulatory dysfunction, and exclusion of related disorders were previously reported (14). Supplemental Table 1 presents clinical characteristics.

Controls were healthy women, with regular menstrual cycles and no evidence of hirsutism, acne, alopecia, or endocrine dysfunction and had not taken hormonal therapy (including oral contraceptives) for at least three months. Controls were recruited by word of mouth and advertisements calling for “healthy women.”

All subjects gave written informed consent. The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Boards of UAB and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Replication cohort

Replication efforts were carried out in an independent cohort consisting of 526 Caucasian PCOS women and 3585 unselected controls from the general population. The replication cohort included patients with oligo- (menstrual cycle ≥35 days) or amenorrhea (absence of vaginal bleeding for at least 6 months), serum FSH levels within the normal limits (1–10 U/l), i.e. normogonadotropic anovulation (classification according to the World Health Organization), and PCOS. PCOS was diagnosed according to the 2003 revised Rotterdam criteria (15). Patients with non-Caucasian ethnic background were excluded.

Controls were drawn from the Rotterdam Study, the design of which was described previously (16). In brief, this is a large population-based study of elderly subjects from a specific area near Rotterdam (Ommoord). All women with age of menopause >45 years and available DNA were included in the present analysis, providing a reference group of allele frequencies reflective of the local general Caucasian population (rather than a control group wherein PCOS was specifically excluded).

The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Erasmus Medical Center and informed consent was obtained from all patients as well as controls.

Genotyping

SNPs were selected using data from the Caucasian (CEU) subjects in the International HapMap database (release 24, http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with the aim of exploiting linkage disequilibrium (LD) for the study of each gene. For all 39 genes, we selected SNPs to tag (r2>0.8) the majority of variation in each gene plus 10 kb upstream and 3 kb downstream or 5% upstream and 5% downstream (depending on gene size), resulting in a total of 341 SNPs. Supplemental Table 2 displays gene statistics; Supplemental Table 3 displays SNP statistics. The average SNP coverage was 74%. 338 of the 341 SNPs were genotyped using the oligo ligation assay (GoldenGate chemistry) on an Illumina (San Diego, CA) BeadStation (17). Six of the SNPs were not polymorphic, and one failed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P<0.001); these SNPs were not considered further. SNPs were clustered in a single project that included all samples and utilized Illumina’s BeadStudio clustering algorithm. Each SNP was then manually reviewed to remove individual samples from each cluster plot that were not clearly assigned to one cluster (major or minor allele homozygotes or heterozygotes). SNPs that did not clearly form three clusters for each genotype group were removed from the analysis. Thirty-nine SNPs were removed because they failed this quality control. Thus, 292 SNPs were ultimately analyzed of the 338 genotyped on this platform. The genotyping success rate for these 292 SNPs was 93.6%. Duplicate genotyping of 10 subjects yielded 100% concordance.

The remaining 3 of the 341 SNPs (from the IRS1 gene) were genotyped using Applied Biosystems Taqman Assays-On-Demand (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The overall genotyping success rate was 93.4%.

Four INSR and three IRS2 SNPs were genotyped in the replication study. For the PCOS cases, Taqman Allelic Discrimination (Applied Biosystems) was used for the INSR SNPs. For the Rotterdam Study controls, genotypes from two INSR SNPs (rs12459488, rs12971499) were extracted from the imputed genotypes GWAS database, while INSR SNPs rs2252673 and rs10401628 were genotyped using Taqman Allelic Discrimination. The IRS2 SNPs (rs7997595, rs7987237, rs1865434) were extracted from the imputed genotypes GWAS database.

We also genotyped 127 ancestry informative markers (18) (listed in Supplemental Table 4) in the discovery cohort and examined the cohort for population structure by generating principal components in Eigenstrat implemented in Golden Helix (Bozeman, MT). Plotting the first and second most informative principal components revealed that the cases and controls were of similar ancestry (Supplemental Figure 1), with the exception of two control subjects, who were excluded from analysis. None of the principal components were associated with PCOS status.

Statistical Analysis

Unpaired t-tests and chi-square tests were used to compare clinical characteristics between cases and controls; quantitative traits were log- or square-root-transformed as appropriate to reduce non-normality. Data are presented as median (interquartile range).

In the discovery cohort, allelic analyses were conducted using chi-square tests to compare allele frequencies between cases and controls for 295 SNPs. The same allelic analyses were carried out in the replication cohort (7 SNPs). We targeted for replication 7 SNPs in the genes with the most SNPs associated with PCOS at P<0.05. In the replication stage, SNPs were considered significantly associated with PCOS if the P-value was below 0.007 (0.05/7 ≈ 0.007).

To assess whether the effects of the seven associated SNPs were independent of BMI, adjusted analyses were conducted with logistic regression; the dependent variable was PCOS status, and the independent variables were genotype (dominant model) and BMI. Furthermore, we directly evaluated the seven SNPs for an effect on BMI by conducting linear regression wherein BMI was the dependent variable. Meta-analyses were conducted on the logistic regression results of the discovery and replication cohorts using the program METAL (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/metal/).

The discovery cohort sample size has good power (≥80%) to detect association of risk alleles of frequency ≥0.2 with PCOS at odds ratio ≥1.75 and moderate power (40–60%) to detect association at odds ratio 1.5; the power to detect association of rare risk alleles (frequency ≤0.1) with PCOS at odds ratios of ≤1.5 is limited (19).

Results

In the discovery cohort (275 cases and 171 controls [2 controls excluded based on principal component analysis]), we analyzed 295 SNPs for association with PCOS (Supplemental Table 3). SNPs with allelic association with PCOS (P<0.05) are listed in Table 1. The gene with the largest number of SNPs significantly associated with PCOS in the discovery phase was INSR. IRS2 also contained several associated SNPs at the top of the list. These observations, and the key importance of INSR and IRS2 in the initial steps of insulin signaling, prompted us to attempt replication of the four INSR SNPs (rs12459488, rs12971499, rs2252673, rs10401628) and three IRS2 SNPs (rs7997595, rs7987237, rs1865434) most associated with PCOS in the discovery cohort. These seven SNPs were not associated with BMI, either in the entire discovery cohort (linear regression, adjusted for age and diagnosis) or in the PCOS women only (adjusted for age).

Table 1.

Allelic association results in the discovery cohort

| Name | Gene | Chr | Alleles (major/minor) | Associated Allele | Case Frequency | Control Frequency | Chi square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs7997595 | IRS2 | 13 | C:G | C | 0.881 | 0.795 | 11.281 | 0.001 |

| rs10401628 | INSR | 19 | G:A | G | 0.919 | 0.856 | 8.298 | 0.004 |

| rs2274490 | SORBS1 | 10 | T:C | C | 0.430 | 0.334 | 7.428 | 0.006 |

| rs7987237 | IRS2 | 13 | C:T | C | 0.884 | 0.817 | 7.398 | 0.007 |

| rs12459488 | INSR | 19 | C:G | C | 0.760 | 0.674 | 7.335 | 0.007 |

| rs12971499 | INSR | 19 | T:C | T | 0.635 | 0.543 | 6.932 | 0.009 |

| rs2252673 | INSR | 19 | C:G | G | 0.178 | 0.112 | 6.479 | 0.011 |

| rs1865434 | IRS2 | 13 | A:G | A | 0.875 | 0.814 | 5.875 | 0.015 |

| rs4952834 | RHOQ | 2 | G:C | C | 0.338 | 0.261 | 5.500 | 0.019 |

| rs3753242 | PRKCZ | 1 | C:T | C | 0.953 | 0.913 | 5.432 | 0.020 |

| rs2267922 | PIK3R2 | 19 | C:G | C | 0.539 | 0.460 | 5.002 | 0.025 |

| rs3736328 | PIK3R2 | 19 | C:G | G | 0.523 | 0.444 | 4.978 | 0.026 |

| rs7207345 | PRKCA | 17 | T:C | C | 0.281 | 0.212 | 4.902 | 0.027 |

| rs6510949 | INSR | 19 | G:T | T | 0.070 | 0.034 | 4.858 | 0.028 |

| rs7641983 | PIK3CA | 3 | C:T | C | 0.832 | 0.772 | 4.610 | 0.032 |

| rs7646409 | PIK3CA | 3 | T:C | T | 0.833 | 0.774 | 4.527 | 0.033 |

| rs3094127 | FLOT1 | 6 | T:C | C | 0.262 | 0.199 | 4.328 | 0.038 |

| rs6020608 | PTPN1 | 20 | C:T | C | 0.764 | 0.702 | 3.923 | 0.048 |

| rs13420857 | RHOQ | 2 | C:G | G | 0.391 | 0.323 | 3.905 | 0.048 |

| rs6443624 | PIK3CA | 3 | C:A | C | 0.771 | 0.711 | 3.848 | 0.050 |

| rs7651265 | PIK3CA | 3 | A:G | A | 0.906 | 0.862 | 3.832 | 0.050 |

SNPs are displayed in order of significance. P values are for allelic association with PCOS (no covariate adjustment). INSR and IRS2 SNPs that were selected for genotyping in the replication cohort are indicated in bold.

Chr, chromosome

These seven SNPs were genotyped in the replication cohort consisting of 526 Caucasian PCOS women and 3585 controls. Association results are presented in Table 2. SNP rs2252673 replicated association with PCOS (P=0.002). Logistic regression analyses revealed that the association of rs2252673 was independent of BMI (Table 3). Carriers of the minor G allele at rs2252673 had an increased odds of PCOS in both the discovery cohort (BMI-adjusted odds ratio (OR)=2.06, 95%CI: 1.21–3.52, P=0.008) and the replication cohort (BMI-adjusted OR=1.32, 95%CI: 1.08–1.60, P=0.006). P-value meta-analysis of the two cohorts for this SNP revealed a combined P=0.00058 (Table 3). The significant associations utilizing the dominant model (Table 3) exhibited similar significance in the additive model.

Table 2.

Allelic association of four INSR and three IRS2 SNPs with PCOS in the replication cohort

| SNP | Gene | Case MAF | Control MAF | Chi Square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs12459488 | INSR | 0.292 | 0.288 | 0.58 | 0.81 |

| rs12971499 | INSR | 0.432 | 0.412 | 1.38 | 0.24 |

| rs2252673 | INSR | 0.209 | 0.170 | 9.56 | 0.002 |

| rs10401628 | INSR | 0.127 | 0.125 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| rs7997595 | IRS2 | 0.173 | 0.166 | 0.186 | 0.666 |

| rs7987237 | IRS2 | 0.151 | 0.153 | 0.039 | 0.842 |

| rs1865434 | IRS2 | 0.153 | 0.153 | 0.014 | 0.907 |

Allelic P values are derived from chi-square testing.

MAF, minor allele frequency

Table 3.

Logistic regression association of four INSR and three IRS2 SNPs in the discovery and replication cohorts

| SNP | Gene | Discovery cohort | Replication cohort | Meta-analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | P value | ||

| rs12459488 | INSR | 0.62 | 0.39–0.98 | 0.04 | 1.11 | 0.92–1.34 | 0.30 | 0.71 |

| rs12971499 | INSR | 0.68 | 0.42–1.11 | 0.12 | 1.05 | 0.86–1.28 | 0.067 | 0.21 |

| rs2252673 | INSR | 2.06 | 1.21–3.52 | 0.008 | 1.32 | 1.08–1.60 | 0.006 | 0.00058 |

| rs10401628 | INSR | 0.45 | 0.25–0.79 | 0.006 | 1.00 | 0.80–1.25 | 0.99 | 0.40 |

| rs7997595 | IRS2 | 0.54 | 0.33–0.89 | 0.015 | 1.09 | 0.84–1.41 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| rs7987237 | IRS2 | 0.54 | 0.33–0.90 | 0.019 | 1.03 | 0.79–1.35 | 0.84 | 0.58 |

| rs1865434 | IRS2 | 0.58 | 0.35–0.95 | 0.032 | 1.05 | 0.80–1.37 | 0.73 | 0.72 |

Logistic regression models included PCOS status as the dependent variable, and genotype (dominant model) and BMI as independent variables. The P value meta-analysis was conducted on logistic regression models in the discovery and replication cohorts.

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

We also analyzed the association of the INSR SNP in the replication cohort with inclusion of only the 286 cases meeting the NIH 1990 definition of PCOS. With the halving of the number of cases in this analysis, statistical significance was diminished, but the odds ratio of association with PCOS for rs2252673 (BMI-adjusted OR=1.34, 95%CI: 1.03–1.74, P=0.03) was identical to that in the entire replication cohort.

Discussion

We have replicated association with PCOS of an INSR variant that predisposes to the syndrome. This result sheds light on the origins of PCOS as an inherited condition characterized by insulin resistance in many affected individuals.

Genetic variation in INSR may affect PCOS risk via an effect on insulin signaling. This was recognized as a possibility early in the field of PCOS genetics. Initial studies screening exons of the INSR gene (typically by polymerase chain reaction and single-stranded conformational polymorphisms, PCR-SSCP) found missense/nonsense mutations only in isolated cases of women with PCOS-like phenotypes (5). Such screens commonly identified only a silent C/T variation in codon His1058, leading many to conclude that INSR variation was not a major factor in PCOS.

In subsequent years, several genetic association studies of INSR in PCOS case/control cohorts were published, most of which focused on His1058 C/T variant; a recent meta-analysis of these studies revealed a non-significant trend (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.88–1.85) for association of this silent variant with PCOS (5). In Chinese subjects, a Cys1008Arg variant in exon 17 was associated with PCOS and lower insulin sensitivity index (20); however, the frequency of this variant in other populations has not been determined (not available in dbSNP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/). A Korean study that genotyped nine variants (initially found by sequencing) found association of a novel intron 21 variant with PCOS; this is another variant not yet listed in dbSNP (21). Thus, we cannot determine whether our replicated INSR SNP is in LD with either of these variants. The microsatellite D19S884, a replicated PCOS locus, was initially selected based on proximity to INSR; however, it resides in a different gene (FBN3) over 850 kb from INSR and therefore likely represents an independent susceptibility locus (22).

The Korean study genotyped rs2252673, and found that carriers of the G allele (major allele in Koreans, minor allele in Caucasians) exhibited a trend to increased PCOS (OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.53–2.26) (21), consistent with our findings for this SNP. This suggests that this variant might influence PCOS risk across three continents (North America, Europe, Asia). If PCOS is an ancient disorder, as recently proposed, one would predict shared susceptibility variants across the globe (23). Further studies of this variant are needed to establish whether rs2252673 is such a universal risk factor for PCOS.

How the replicated variant affects INSR function and/or expression is unknown. SNP rs2252673 is not in LD (r2 > 0.8) with any other SNP in the INSR gene in the HapMap Caucasian database (24). As an intronic variant, it may be in LD with unknown functional (or not yet genotyped in HapMap) variants elsewhere in the gene. Sequencing may identify coding variants in LD with the associated variant. Alternatively, the variant itself may influence INSR transcription or mRNA splicing. In the TESS database (Transcription Element Search System, http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/tess), rs2252673 results in alternative possible transcription factor binding sites. Two forms of the INSR arise from alternative splicing of exon 11 (excluded from the A isoform and included in the B isoform). The A isoform, expressed mainly during fetal development and the adult brain, has low affinity for insulin but high affinity for insulin like growth factor 2; the B isoform has high affinity for insulin and is expressed in insulin responsive tissues such as muscle, liver and adipose (25). Whether the replicated INSR SNP affects INSR splicing and/or transcription must be determined by biochemical studies. Tissue-specific effects (e.g. muscle, liver, ovary) could also be evaluated.

The large size of the INSR gene (>180 kb) has challenged its investigation as a candidate gene. Prior studies only looked at one or a few variants in the gene, leading to incomplete coverage of its genetic variation. This is the first study that tagged the entire INSR region using information from HapMap (24). This was critical to allow the discovery phase to detect INSR variants potentially associated with PCOS.

Efforts to replicate genetic association results have been infrequent in the field of PCOS genetics. Examples include replication studies of HSD17B5 (26), HSD17B6 (27), CYP11A1 (28), the insulin gene (29), and others (22, 30). A key factor in our successful replication was that the replication cohort was substantially larger than the discovery cohort. Genetic effect size is typically overestimated in initial studies, a phenomenon known as the “winner’s curse” (31). Therefore, replication cohorts should be larger than discovery cohorts to have sufficient power to detect the association at a lower effect size. This proved to be true in our study, wherein the odds ratio for association with PCOS was higher in the discovery cohort than the replication cohort. Another possible explanation for the different effect sizes is that PCOS was excluded from the discovery cohort controls (increasing power for discovery), whereas the replication cohort controls consisted of an unselected sample representative of the general population. The latter large (>3500 subjects) population-based sample may indicate broad generalizability of our findings.

Ideally, both the discovery cohort and replication cohort PCOS cases would have been diagnosed using the same criteria. This was not the case because these are pre-existing cohorts. Fortunately, this did not hinder our ability to replicate at least one SNP association with PCOS. We ruled out BMI disparity between cases and controls as a cause of spurious SNP association with PCOS by directly ruling out SNP association with BMI and by adjusting for BMI as a covariate.

We did not adjust the results in the discovery cohort for multiple testing (e.g. Bonferroni correction) because we planned to follow-up with a replication effort. Replication is the optimal solution to multiple testing. We corrected for multiple testing in the replication phase. Given their central roles in insulin signaling and preponderance of significant SNPs in the discovery phase (Table 1), we first attempted to replicate variants in INSR and IRS2. In the future, we will attempt to replicate SNPs in other loci associated with PCOS in the discovery cohort. We hope that this publication inspires other investigators to also examine these loci in their cohorts.

In conclusion, in a survey of 39 genes coding for the central components of metabolic insulin signaling pathways, we identified SNPs in the INSR and IRS2 genes that were associated with PCOS. One of these SNPs replicated association with PCOS in a larger, independent cohort. These data should reinvigorate interest in INSR as a genetic susceptibility factor for PCOS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported in part by NIH grants R01-HD29364 and K24-HD01346 (to RA), R01-DK79888 (to M.O.G.), and M01-RR00425 (General Clinical Research Center Grant from the NCRR), the Winnick Clinical Scholars Award (to M.O.G.), and an endowment from the Helping Hand of Los Angeles, Inc. The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission (DG XII), and the Municipality of Rotterdam. The generation and management of GWAS genotype data for the Rotterdam Study is supported by the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research NWO Investments (nr. 175.010.2005.011, 911-03-012). This study is funded by the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (014-93-015; RIDE2), the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (nr. 050-060-810).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: M.O.G, Y.V.L., K.D.T., M.R.J., J.C., S.K., Y-D.I.C., X.G., L.S., A.G.U., and R.A. have nothing to declare. J.S.E.L. has received grants from Genovum, Merck Serono, Organon, SheringPlough, MSD and Serono.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DeUgarte CM, Bartolucci AA, Azziz R. Prevalence of insulin resistance in the polycystic ovary syndrome using the homeostasis model assessment. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1454–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palomba S, Falbo A, Zullo F, Orio F. Evidence-based and potential benefits of metformin in the polycystic ovary syndrome: a comprehensive review. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:1–50. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodarzi MO. Looking for polycystic ovary syndrome genes: rational and best strategy. Semin Reprod Med. 2008;26:5–13. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-992919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legro RS, Bentley-Lewis R, Driscoll D, Wang SC, Dunaif A. Insulin resistance in the sisters of women with polycystic ovary syndrome: association with hyperandrogenemia rather than menstrual irregularity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2128–33. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ioannidis A, Ikonomi E, Dimou NL, Douma L, Bagos PG. Polymorphisms of the insulin receptor and the insulin receptor substrates genes in polycystic ovary syndrome: A Mendelian randomization meta-analysis. Mol Genet Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lizcano JM, Alessi DR. The insulin signalling pathway. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R236–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumann CA, Saltiel AR. Spatial compartmentalization of signal transduction in insulin action. Bioessays. 2001;23:215–22. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200103)23:3<215::AID-BIES1031>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simoni M, Tempfer CB, Destenaves B, Fauser BC. Functional genetic polymorphisms and female reproductive disorders: Part I: Polycystic ovary syndrome and ovarian response. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:459–84. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1175–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang W, Goodarzi MO, Williams H, Magoffin DA, Pall M, Azziz R. Adipocytes from women with polycystic ovary syndrome demonstrate altered phosphorylation and activity of glycogen synthase kinase 3. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:2291–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodarzi MO, Antoine HJ, Pall M, Cui J, Guo X, Azziz R. Preliminary evidence of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta as a genetic determinant of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:1473–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodarzi MO, Jones MR, Chen YD, Azziz R. First evidence of genetic association between AKT2 and polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2284–7. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zawadzki J, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine FP, Merriam GR, editors. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Boston: Blackwell Scientific; 1992. pp. 377–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofman A, Breteler MM, van Duijn CM, Krestin GP, Pols HA, Stricker BH, et al. The Rotterdam Study: objectives and design update. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:819–29. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunderson KL, Steemers FJ, Ren H, Ng P, Zhou L, Tsan C, et al. Whole-genome genotyping. Methods Enzymol. 2006;410:359–76. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)10017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosoy R, Nassir R, Tian C, White PA, Butler LM, Silva G, et al. Ancestry informative marker sets for determining continental origin and admixture proportions in common populations in America. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:69–78. doi: 10.1002/humu.20822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:149–50. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin L, Zhu XM, Luo Q, Qian Y, Jin F, Huang HF. A novel SNP at exon 17 of INSR is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity in Chinese women with PCOS. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:151–5. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee EJ, Oh B, Lee JY, Kimm K, Lee SH, Baek KH. A novel single nucleotide polymorphism of INSR gene for polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart DR, Dombroski BA, Urbanek M, Ankener W, Ewens KG, Wood JR, et al. Fine mapping of genetic susceptibility to polycystic ovary syndrome on chromosome 19p13.2 and tests for regulatory activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4112–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azziz R, Dumesic DA, Goodarzi MO. Polycystic ovary syndrome: an ancient disorder? Fertil Steril. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.032. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The International HapMap Consortium. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–96. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belfiore A, Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor isoforms and insulin receptor/insulin-like growth factor receptor hybrids in physiology and disease. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:586–623. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodarzi MO, Jones MR, Antoine HJ, Pall M, Chen YD, Azziz R. Nonreplication of the type 5 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene association with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:300–3. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones MR, Mathur R, Cui J, Guo X, Azziz R, Goodarzi MO. Independent confirmation of association between metabolic phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome and variation in the type 6 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:5034–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaasenbeek M, Powell BL, Sovio U, Haddad L, Gharani N, Bennett A, et al. Large-scale analysis of the relationship between CYP11A promoter variation, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and serum testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2408–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell BL, Haddad L, Bennett A, Gharani N, Sovio U, Groves CJ, et al. Analysis of multiple data sets reveals no association between the insulin gene variable number tandem repeat element and polycystic ovary syndrome or related traits. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2988–93. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ewens KG, Stewart DR, Ankener W, Urbanek M, McAllister JM, Chen C, et al. Family-based analysis of candidate genes for polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2306–15. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraft P. Curses--winner’s and otherwise--in genetic epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2008;19:649–51. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318181b865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.