Abstract

Background

A review of the literature was conducted to examine the relationship between the use of anabolic androgenic steroid (AAS) use and the use of other drugs.

Methods

Studies published between the years of 1995–2010 were included in the review.

Results

The use of AAS is positively associated with use of alcohol, illicit drugs and legal performance enhancing substances. In contrast, the relationship between AAS and the use of tobacco and cannabis are mixed.

Conclusion

Results of the review indicate that the relationship between AAS use and other substance use depends on the type of substance studied. Implications for treatment and prevention are discussed. Suggestions for future research are provided.

Keywords: Anabolic steroids, polypharmacy, performance enhancing substances, dietary supplements, drug use

1.0 Introduction

Performance enhancing substances (PES) are substances used by individuals to help improve their athletic performance or physical appearance. One of the most commonly studied PES are anabolic-androgenic steroids ([AAS], Yesalis, 2000). Although there are a number of legitimate medical uses for AAS, research suggests that some individuals use AAS for illegitimate reasons. Those who misuse AAS often do so to improve their physical appearance or athletic performance (Bahrke et al., 2000; Dodge and Jaccard, 2006). Prevalence estimates of AAS use tend to hover around 2% in studies with adolescent and college aged samples (Dodge and Jaccard, 2006; Hoffman et al., 2007), but are generally higher among those involved in power sports or weight lifting with estimates ranging from about 20% to more than 50% (Beel et al., 1998; Kanayama et al., 2009).

Misuse of AAS is believed to lead to a number of health problems like liver malfunction, problems with reproductive organs, and cardiac problems (Bolding et al., 2002; Büttner and Thieme, 2010; Nieminen et al., 1996; Salas-Ramirez et al., 2010; Santora et al., 2006; Sullivan et al., 1999). In addition to health risks, misuse of, and dependence on, AAS is associated with psychological disturbances like higher levels of aggression, depression, conduct disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder (Bolding et al., 2002; Choi and Pope, 1994; Kanayama et al., 2009).

A great deal of research has focused on identifying factors that place individuals at risk for AAS misuse (for a complete review see Bahrke et al., 2000). These risk factors include being male, participating in a strength-related sport, lifting weights at a commercial gym, and knowing an AAS user (Dodge and Jaccard, 2006; Mccabe et al., 2007; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001; Wichstrøm, 2006; Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001).

Over the past decade and a half there has been increasing interest in understanding the relationship between the use of AAS and other drugs. Some of this literature has reported that use of AAS is positively associated with the use of other substances including legal PES, alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs (DuRant et al., 1995; Kindlundh et al., 1999). However, other studies have failed to document such relationships (Dodge and Jaccard, 2006; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001) raising questions about the nature of the relationship between AAS use and the use of other substances. Furthermore, recent studies have suggested that similar physiological mechanisms may be responsible for AAS abuse and the abuse of specific types of substances. For example, Kanayama and colleagues (2003a; 2009) have found that AAS abuse and opioid abuse tend to co-occur, but AAS abuse and the abuse of other drugs (e.g., alcohol) do not.

The purpose of the present paper is twofold. One purpose is to characterize the relationship between AAS use and the use of other drugs. A second purpose is to identify whether this relationship differs by type of drug.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Selection of Studies

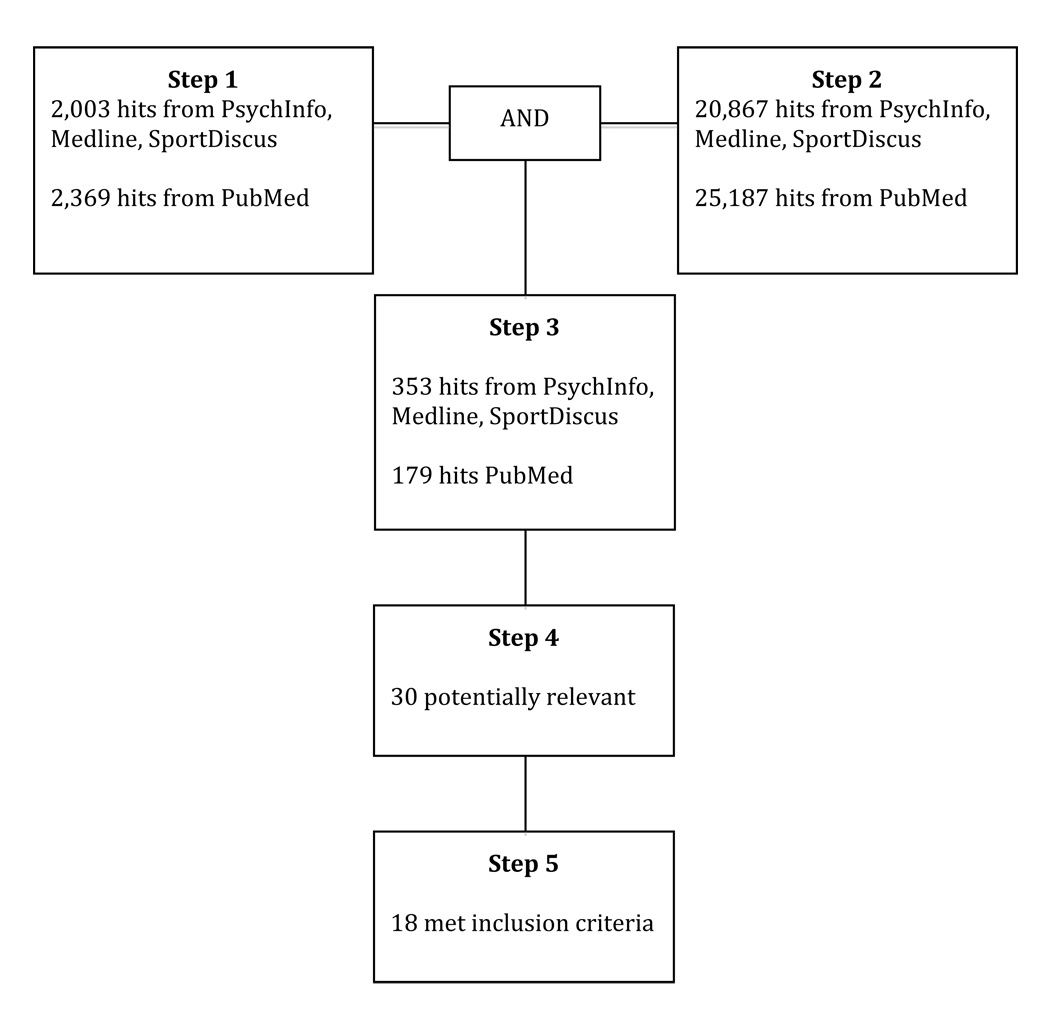

Relevant studies were identified by searching the following databases: Medline, PubMed, PsychInfo and SportDiscus (from April 2010 to August 2010). The search was restricted to peer-reviewed empirical studies, with human subjects, published in the English language between the years 1995–2010.1 The first step was to search the terms “anabolic steroids” or doping or “anabolic androgenic steroids” or “anabolic-androgenic steroids”. The second step was to search using the following terms with operator or: “alcohol use”, “binge drinking”, “illicit drugs”, heroin, cocaine, “performance enhancers”, “performance enhancing substances”, “ergogenic aids”, and “nutritional supplements”. The third step was to combine the two searches which yielded a total of 353 studies from Medline, PsychInfo and SportDiscus. Using PubMed the search yielded 179 studies. The titles and abstracts of these studies were reviewed to determine whether the study was relevant. At this step 30 studies were identified as potentially relevant. The final step involved reading the manuscript to determine whether the study met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the number of hits encountered at each step.

Figure 1.

Pictorial representation of steps involved in the literature search.

2.2 Inclusion Criteria

To be included, studies must have assessed AAS use and other drug use, provided a description of the measures used and must have tested for a relationship between AAS use and the use of other drugs. Of the 30 studies identified at the first stage as potentially relevant, a total of 18 studies were retained for review.2

2.3 Study Characteristics

2.3.1 Sample and Design

A majority of the studies (88.9%) relied on adolescents sampled from high schools (n=13) or college campuses (n=3). Nearly 56% of the studies (n=10) used samples from the US, and the remaining 44% (n=8) included non-US samples. Table 1 lists the sample characteristics. All of the studies, except one (Wichstrøm, 2006), were cross-sectional.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Authors | Title | Sample | Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denham, B. E. (2009) | Association between narcotic use and anabolic-androgenic steroid use among American adolescents | 2,489 high school seniors; gender was not reported | US |

| Dodge, T. L. and Jaccard, J. J. (2006) | The effect of high school sports participation on the use of performance enhancing substances in young adulthood | 15,000 school based sample of adolescents and young adults; grades 7–12; 50.8% male | US |

| Durant, R. H., Escobedo, L. G., and Heath, G. W. (1995) | Anabolic-steroid use, strength training, and multiple drug use among adolescents in the United States | 12,267 students in grades 9–12; 48.8% male | US |

| Hoffman, J. R., Faigenbaum, A. D., Ratamess, N. A., Ross, R., Kang, J. and Tenenbaum, G. (2007) | Nutritional supplementation and anabolic steroid use in adolescents | 3,248 students in grades 8–12; 48% male | US |

| Kanayama, G., Pope, H. G., Cohane, G., and Hudson, J. I. (2003b) | Risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid use among weightlifters: a case-control study | 93 males ages 18–65 weightlifters recruited from gyms and nutrition stores; 48 who had used AAS for at least 2 months and 45 who had never used AAS | US |

| Kanayama, G., Hudson, J. I., and Pope, H. G. (2009) | Features of men with anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: A comparison with nondependent AAS users and with AAS nonusers | 134 males with history weight lifting ages 18–40 years; no history of AAS use dependence n=72, used AAS nondependent n=42, meet DSM-IV criteria dependence on AAS n=20 | US |

| Kindlundh, A. M. S., Isacson D. G., L., Berglund, L., and Nyberg, F. (1999) | Factors associated with adolescent use of doping agents: anabolic-androgenic steroids | 2,742 senior high school students; included males and females, but gender distribution was not reported | Sweden |

| Kokkevi, A., Fotiou, A., Chileva, A., Nociar, A., and Miller, P. (2008) | Daily exercise and anabolic steroids use in adolescents: A cross-national European study | 18,430 high school students 16-years of age; included males and females, but gender distribution was not reported | Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Slovak Rep. and U.K. |

| Luetkemeier, M. J., Bainbridge, J. W., Brown, D. B., and Eisenman, P. A. (1995) | Anabolic-androgenic steroids: Prevalence, knowledge, and attitudes in junior and senior high school students | 1,907 junior and senior high school students; grades 7–12; 69.5% male | US |

| McCabe, S. E., Brower, K. J., West, B. T., Nelson, T. F., and Wechsler, H. (2007) | Trends in non-medical use of anabolic steroids by U.S. college students: Results from four national surveys | Four samples of college students from the years, 1993, 1997, 1999, 2001; Sample sizes ranged from 10,904 in 2001 to 15,282 in 1993; included males and females, but gender distribution was not reported | US |

| Meilman, P. W., Crace, R. K., Presley, C. A., and Lyeria, R. (1995) | Beyond performance enhancement: Polypharmacy among collegiate users of steroids | 55,175 college students; included males and females, but gender distribution was not reported | US |

| Miller, K. E., Hoffman, J. H., Barnes, G. M., Sabo, D., Melnick, M. J., and Farrell, M. P. (2005) | Adolescent anabolic steroid use, gender, physical activity, and other problem behaviors | 16,183 adolescents in grades 9–12; included males and females, but gender distribution was not reported | US |

| Nilsson, S., Spak, F., Marklund, B., Baigi, A. and Allebeck, P. (2005) | Attitudes and behaviors with regards to androgenic anabolic steroids among male adolescents in a county of Sweden | 3,730 male adolescents aged 14, 16, and 18 | Sweden |

| Pallesen, S., Jøsendal, O., Hohnsen, B. H., Larsen, S., and Molde, H. (2006) | Anabolic steroid use in high school students | 1,351 high school students; 11–13th grade; 52% male | Norway |

| Papadopoulos, F. C., Skalkidis, I., Parkkari, J. and Petridou, E. (2006) | Doping use among tertiary education students in six developed countries | 2,650 tertiary students; included males and females, but gender distribution was not reported | Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, and Israel |

| Pedersen, W. and Wichstrøm, L. (2001) | Adolescents, doping agents, and drug use: A community study | 10,828 adolescents 14–17 years sampled from schools; 50.8% boys | Norway |

| Wichstrøm, L. (2006) | Predictors of future anabolic androgenic steroid use | 2,924 high school students; 15–19 years; 43% male | Norway |

| Wichstrøm, L. and Pedersen, W. (2000) | Use of anabolic-androgenic steroids in adolescence: Winning, looking good or being bad? | 8,877 high school students grades 7–12; 42.6% male | Norway |

2.3.2 Measures of Drug Use

Table 2 shows the measures of drug use included in each study. A majority of studies included specific measures of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis. With respect to the use of illicit drugs, the use of a variety of drugs was assessed and, occasionally, the studies combined different drugs into an overall assessment of drug involvement (See Table 2). Results are presented for each of the following categories of substances: alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, illicit drugs, and legal PES. When describing the results, we use the term ‘recent use’ to mean use of a substance within the past year or sooner (e.g., with the past 30-days).

Table 2.

Measures Reported in Each Study

| Study | AAS | Alcohol | Tobacco | Cannabis | Illicit Drugs | Legal PES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denham, 2009 | Use of AAS* | Number of occasions during lifetime been drunk | - | Number of occasions used marijuana or hashish during lifetime | Ever used crack or cocaine; Used heroin, club drugs (GHB Ketamine, Rohypnol), heroin, OxyContin, Ritalin, Vicoden | - |

| Dodge and Jaccard, 2006 | Past year use of AAS or other illegal PES for athletes | In the past 12-months engaged in binge drinking | - | - | Past 12-months used illegal drugs (e.g., LSD, PCP); injected any illegal drug | Past 12-months used legal PES for athletes |

| DuRant et al., 1995 | During life, number of times taken AAS; multivariate analyses used dichotomous variable | Frequency during past 30-days had at least one alcoholic drink | Frequency during past 30-days: smoked cigarettes; used chewing tobacco or snuff | Frequency during past 30-days used marijuana | Frequency during past 30 days used cocaine; illegal drugs (e.g., LSD, PCP, ecstasy) | - |

| Hoffman et al., 2007 | Checked whether used AAS in lifetime | - | - | - | - | Checked from a list substances used in lifetime to gain muscle |

| Kanayama et al., 2003b | Used AAS for at least 2 months at some point vs. never used | Verbal interview determined history alcohol use | - | - | Verbal interview determined history of, non-alcohol substance use and any illicit substance | - |

| Kanayama et al., 2009 | Never used AAS vs. used but not dependent on AAS vs. AAS dependent | Verbal interview determined alcohol dependence | - | Verbal interview determined cannabis dependence | Verbal interview determined dependence on, cocaine; opiods; non-alcohol dependence | - |

| Kindlundh et al., 1999 | Whether ever used AAS, peptide hormones, or testosterone without doctor’s prescription | Alcohol consumption defined as at least half bottle of spirits, one bottle of wine, four bottles of beer on same occasion* | Smoking and snuff combined* | - | Use of psychotropics (combined use of cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines)* | - |

| Kokkevi, et al., 2008 | Checked substances used during lifetime and AAS use was one option | Current alcohol use (i.e., drank on at least 10 occasions in last 30-days) | Daily smoker (i.e., smoked 6 or more cigarettes per day in the last month) | Lifetime use of cannabis use | Lifetime use of tranquilizers or sedatives | - |

| Luetkemeier et al., 1995 | Lifetime use of AAS | Past or present use of alcohol | - | Past or present use of cannabis | Past or present use of cocaine | - |

| McCabe et al., 2007 | Lifetime non-medical use of AAS | Binge drinking in past 2-weeks | Cigarette use in past 30 days | Past year use of cannabis | Past year use of, cocaine; ecstasy; tranquilizers; sedatives; stimulants; opioids; other illicit drugs (e.g., LSD, heroin) | - |

| Meilman et al., 1995 | Users defined as having used AAS at least 6 times in the previous year | Average number drinks consumed each week; binge drinking past 2-weeks | Past 12-months used tobacco at least once a week | Past 12-months used cannabis once a week | Past 12-months used, cocaine, amphetamines; sedatives; hallucinogens, opiates, inhalants; designer drugs | - |

| Miller et al., 2005 | Lifetime use of AAS | Number of times past 30-days engaged in binge drinking | In past 30 days, average number of cigarettes smoked per day; number of days used smokeless tobacco | Number of times past 30-days used cannabis | Number of times past 30-days used cocaine | - |

| Nilsson et al., 2005 | Lifetime use of AAS | During lifetime, regular use of alcohol; drink home-made alcohol; been drunk; get drunk every time drink alcohol | Smoke cigarettes daily | Lifetime use of cannabis | Lifetime use of, amphetamines; heroin, morphine; cocaine, LSD; Ecstasy; Benzodiazepines; inhalants | - |

| Pallesen et al., 2006 | Ever, in the past or presently, use AAS | Harmful alcohol use (assed with Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Scale); lifetime alcohol use | Regular smoker | Ever used illegal drugs | ||

| Papadopoulos et al., 2006 | Ever used substance to enhance sport performance (e.g., beta blockers, stimulants, hormones, anabolics) | Often been drunk during life | Smoke tobacco* | Use nutritional performance enhancing substances* | ||

| Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001 | Ever used doping agents | Number times in past 4-weeks had 5+ units of alcohol; Frequency of alcohol use; Amount of Alcohol problems (measured by Rutger’s Alcohol Problem Index) | Daily smoking or use of smokeless tobacco | Drug involvement past 12-months (categories: no illegal use; only cannabis; amphetamine & cannabis; MDMA, cannabis & amphetamine; heroin, cannabis, amphetamine & MDMA | ||

| Wichstrøm, 2006 | Ever used AAS was asked at two time points separated by 5 years | Number of times past 12-months intoxicated from drinking (i.e., as feeling intoxicated) | Number times past 12-months used cannabis | Number times past 12-months used hard drugs | ||

| Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001 | Ever used AAS | In the past 12-months number of times experienced intoxication (i.e., felt intoxicated) | Number of times past 12-months used cannabis | Number of times past 12-months used, solvents; hard drugs |

timeframe not specified

Some studies only reported results of bivariate analyses between AAS use and other drug use, some only reported multivariate analyses whereas other studies reported both types of analyses. In multivariate analyses authors controlled for a variety of variables that have a long history of predicting AAS use such as gender, age, and participation in sports or strength training. Additionally, nearly all of these studies also controlled for the use of all drugs simultaneously.3 Covariates that were used in the multivariate analyses are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Alcohol, Tobacco and Marijuana

| Covariates | Alcohol | Tobacco | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate | Mulitvariate | Bivariate | Mulitvariate | ||

| Denham, 2009 | Race, gender, media exposure, socializing with friends, frequency of recreational sports participation, drug use+ | Positive | Positive | - | - |

| Dodge and Jaccard, 2006 | Race, gender, age | NS | - | - | - |

| DuRant et al., 1995 | Gender, strength exercises, sports teams, school achievement, age, drug use+ | Positive | Positive | Positive | NS |

| Hoffman et al., 2007 | Gender | - | - | - | - |

| Kanayama et al., 2003b | NS | - | - | - | |

| Kanayama et al., 2009 | Age, study site, ethnicity | - | NS | - | - |

| Kindlundh et al., 1999 | Age, strength training, living alone, truancy, drug use+ | Positive | NS | Positive | Positive |

| Kokkevi, et al., 2008 | Country, sports participation, gender, perceived effectiveness of AAS, drug use+ | Positive | Positive | Positive | NS |

| Luetkemeier et al., 1995 | Positive | - | - | - | |

| McCabe et al., 2007 | Gender, race, age, marital status, living arrangement, grade point average, sports participation, geographical region, commuter status and urbanicity, intercollegiate athlete | - | Positive | - | Positive |

| Meilman et al., 1995 | Positive | - | Positive | - | |

| Miller et al., 2005 | Gender, race, age, parental education, sports participation, strength conditioning, sexual risk taking, fighting, drug use+ | - | Positive | - | NS |

| Nilsson et al., 2005 | Positive | - | Positive | - | |

| Pallesen et al., 2006 | Gender, anxiety, depression, rural/urban place of residence, drug use+ | Positive | Positive | Positive | NS |

| Papadopoulos et al., 2006 | Country, gender, age, BMI, school type (biomedical/other) | Positive | Positive | NS | NS |

| Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001 | Gender, parental characteristics, evenings in town center, days training in athletic club, days in commercial gym, drug use+ | Positive | Positive | Positive | Mixed^ |

| Wichstrøm, 2006 | Age, gender, past AAS use, offers of AAS use | - | Positive | - | - |

| Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001 | Gender, sexual intercourse, disordered eating, conduct problems, offered marijuana, involvement in power sports, drug use+ | Positive | NS | - | - |

NS = statistically non-significant

some assessment of drug use was entered as a covariate in multivariate analyses (often all of the drugs assessed in the study were entered simultaneously as covariates)

use of anabolic steroids positively associated with use of smokeless tobacco, but not statistically significantly associated with cigarette smoking

3.0 Results

3.1 Alcohol

3.1.1 Bivariate Relationships

A total of 13 studies reported bivariate relationships between alcohol use and AAS use. Eleven of the studies reported positive relationships between the two substances. The studies indicate that lifetime use of AAS use is positively associated with recent alcohol use (DuRant et al., 1995; Kindlundh et al., 1999; Kokkevi et al., 2008;), lifetime alcohol use (Luetkemeir et al., 1995; Nilsson et al., 2005; Pallesen, et al., 2006), lifetime drunkenness (Papdopoulos, et al., 2006), amount of alcohol consumed in the previous 4-weeks (Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001) and harmful/problem drinking (Pallesen et al., 2006; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001, Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2000). Denham (2009) reported that use of AAS was positively associated with the number of occasions during one’s life s/he had been drunk. Finally, one study reported that recent AAS use was associated with recent use of alcohol and binge drinking (Meilman et al., 1995).

Although a majority of the studies reported a positive relationship between AAS and alcohol use, there were two exceptions. Dodge and Jaccard (2006) reported a statistically non-significant relationship between the use of AAS and binge drinking within the previous 12-months. Kanayama and colleagues (2003b) failed to find statistically significant differences between AAS users and non-users with respect to alcohol dependence. Thus, nearly 85% (n=11) of the studies reported positive bivariate relationships between AAS use and alcohol use while about 15% (n=2) reported no statistically significant relationships between the two substances. These results are shown in Table 3.

3.1.2 Multivariate Analyses

Twelve of the studies included multivariate analyses and nine reported positive relationships between AAS use and alcohol use. In these studies, lifetime use of AAS was predicted by recent alcohol use (DuRant et al., 1995; Kokkevi, 2008), recent binge drinking (McCabe et al. 2007; Miller et al., 2005), problem drinking (Pallesen et al., 2006; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001), and the number of times ever having been drunk (Papadopoulos, et al., 2006). Dedham (2009) reported that the likelihood one had used AAS was predicted by the number of times one had been drunk during their lifetime. One study reported that frequent drunkenness predicted AAS use 5-years later (Wichstrøm, 2006).

While nine studies reported positive relationships between AAS and alcohol use, three reported no statistically significant relationship between AAS use and alcohol dependence (Kanayama et al., 2009), alcohol consumption (Kindlundh, et al., 1999) and frequent drunkenness (Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001). Thus, about 75% (n=9) of the multivariate analyses indicate a positive relationship between AAS use and alcohol use with the remaining 25% (n=3) reporting no statistically significant relationship between the two substances. These results are shown in Table 3.

3.2 Tobacco

3.2.1 Bivariate Relationships

Eight studies that examined the AAS-tobacco use relationship reported results of bivariate analyses, and all but one reported a positive relationship between use of the two substances. The exception was a study by Papadopoulos et al. (2006), which failed to find a statistically significant difference in smoking habits between those who had used AAS before and those who had not.

Of the seven studies reporting a positive relationship between AAS and tobacco use, six reported a positive relationship between lifetime use of AAS and tobacco such that those who had ever used AAS were more likely than those who never used AAS to be smokers (DuRant et al., 1995; Kokkevi et al., 2008; Nilsson et al., 2005; Pallesen et al., 2006; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001), use smokeless tobacco (Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001) or do both (Kindlundh et al., 1999). One study reported that those who had used AAS within the past 12-months were more likely than those who did not use AAS to use tobacco within that same timeframe (Meilman et al., 1995). Thus, about 88% (n=7) of the studies that reported bivariate analyses documented a positive relationship between the use of AAS and tobacco while about 12% (n=1) reported no statistically significant relationship between the two substances. These results are shown in Table 3.

3.2.2 Multivariate Analyses

Eight studies reported multivariate analyses, and in all eight studies the dependent variable was lifetime use of AAS. Five studies reported that neither current smoking status (DuRant et al., 1995; Kokkevi et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2005; Nilsson et al., 2005; Pallesen et al., 2006) nor current use of smokeless tobacco (DuRant et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2005) were statistically significant predictors of lifetime AAS use.

Two studies reported a statistically significant positive relationship between AAS use and use of tobacco. These studies reported that smoking (McCabe et al., 2007) and that the combination of cigarette and smokeless tobacco use (Kindlundh et al., 1999) predicted whether one had tried AAS. A study by Pedersen and Wichstrøm (2001) reported mixed results whereby smokeless tobacco predicted lifetime use of AAS, but cigarette smoking did not. Thus, about 62.5% (n=5) of the studies failed to find a statistically significant relationship between use of tobacco and AAS, 25% (n=2) found a statistically significant positive relationship while 12.5% (n=1) reported mixed results. These results are shown in Table 3.

3.3 Cannabis

Two studies included cannabis in a combined drug use variable and are not reported here but are reported in the illegal substances section (Kanayama et al., 2003b; Kindlundh et al., 1999).

3.3.1 Bivariate Relationships

Eleven studies reported results of bivariate analyses testing the relationship between use of cannabis and AAS use, and a positive relationship was reported in every study except one (Kanayama et al., 2003b). The exception reported no statistically significant differences between AAS users and non-users in cannabis use.

The remaining studies reported that those who had used AAS during their life were statistically significantly more likely than those who had not used AAS to report lifetime (Kokkevi et al., 2008; Luetkemeier et al., 1995; Nilsson et al., 2005; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001) and recent (DuRant et al., 1995; Meilman et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2005; Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001) use of cannabis. One study reported that the use of AAS was positively associated with the number of times one had used marijuana during their lifetime (Denham, 2009) and another reported that use of AAS was predicted from cannabis use 5-years earlier (Wichstrøm, 2006). Thus, almost 91% (n=10) of the studies reported a positive relationship between AAS use and use of cannabis, while 9% (n=1) reported no statistically significant relationship between the two substances. These results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Cannabis, Illicit Drugs and Legal PES

| Cannabis | Illicit Drugs | Legal PES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate | Mulitvariate | Bivariate | Mulitvariate | Bivariate | Multivariate | |

| Denham, 2009 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Mixed^ | - | - |

| Dodge and Jaccard, 2006 | - | - | Mixed+ | - | Positive | |

| DuRant et al., 1995 | Positive | NS | Positive | Positive | - | - |

| Hoffman et al., 2007 | - | - | - | - | - | Positive |

| Kanayama et al., 2003b | NS | - | Mixed* | - | - | - |

| Kanayama et al., 2009 | - | NS | - | Mixed++ | - | - |

| Kindlundh et al., 1999 | - | - | Positive | Positive | - | - |

| Kokkevi, et al., 2008 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | - | - |

| Luetkemeier et al., 1995 | Positive | - | Positive | - | - | - |

| McCabe et al., 2007 | - | Positive | - | - | - | - |

| Meilman et al., 1995 | Positive | - | Positive | - | - | - |

| Miller et al., 2005 | Positive | NS | Positive | Positive | - | - |

| Nilsson et al., 2005 | Positive | - | Positive | - | - | - |

| Pallesen et al., 2006 | - | - | Positive | Positive | - | - |

| Papadopoulos et al., 2006 | - | - | - | - | Positive | Positive |

| Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001 | Positive | Negative | Positive | Positive | - | - |

| Wichstrøm, 2006 | Positive | NS | NS | NS | - | - |

| Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001 | Positive | Positive | Positive | NS | - | - |

Note: Covariates for multivariate analyses are shown in Table 3.

AAS use positively associated with use of an injectable drug, but not with drug use

anabolic steroid use positively associated with any non-alcohol substance use, marginally significant positive relationship between anabolic steroid use and any illicit drug

use of crack, vicodin and GHB predicted use of AAS. Neither use of heroin, OxyContin, Ritalin, Ketamine nor Rohypnol predicted AAS use

those dependent on AAS more likely to be dependent on opiods than non-AAS users or non-dependent users; differences in cocaine dependence between groups of AAS users was small

3.3.2 Mulitvariate Analyses

Nine studies conducted multivariate analyses to examine the relationship between cannabis and AAS use. Three reported that lifetime AAS use was predicted by lifetime (Kokkevi et al., 2008) and recent (McCabe et al., 2007; Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001) cannabis use. One reported that use of AAS was predicted by the number of times during one’s life they had used marijuana (Denham, 2009).

Two studies documented that having used cannabis before was not a statistically significant predictor of whether one had used AAS during one’s lifetime (DuRant et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2005). One study reported that those who were dependent on AAS were no more or less likely than those who never used AAS to be dependent on cannabis (Kanayama et al., 2009). Another study failed to find a statistically significant relationship between cannabis use and use of AAS 5-years later (Wichstrøm, 2006). While Pedersen and Wichstrøm (2001) found a positive bivariate relationship between lifetime AAS use and lifetime cannabis use, this relationship became statistically significantly negative when controlling for factors like gender, participation in strength training and use of other drugs.

Of the nine studies reporting multivariate analyses, about 44.4% (n=4) reported a positive relationship between the two substances. About 44.4% (n=4) of the studies failed to find a statistically significant relationship between AAS and cannabis use while 11.1% (n=1) reported an inverse relationship between the two substances. The results of these studies are shown in Table 4.

3.4 Illicit Substances

3.4.1 Bivariate Relationships

Fourteen studies reported results from bivariate analyses and almost all reported that those who had used AAS at some point during their lives were more likely than those who never used AAS to have used other illicit drugs including, but not limited to, recent and lifetime use of, inhalants (Meilman et al., 1995; Nilsson et al., 2005; Wichstrøm and Pedersen, 2001), amphetamines (Kindlundh et al., 1999; Meilman et al., 1995; Nilsson et al., 2005), cocaine (DuRant et al., 1995; Luetkemeier et al., 1995; Meilman et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2005; Nilsson et al., 2005), tranquilizers and sedatives (Kokkevi et al., 2008) and hallucinogens (Kindlundh et. al., 1999; Meilman et al., 1995; Nilsson et al., 2005). One study reported that the use of AAS was positively associated with the use cocaine, crack, GHB, heroin, ketamine, OxyContin, Ritalin, Rohypnol and Vicodin during one’s lifetime (Denham, 2009).

There were two studies that provided mixed results with respect to the relationship between AAS use and illicit drug use. In a study by Dodge and Jaccard (2006) use of AAS in the past year was unrelated to use of illicit drugs during the same timeframe (a combined measure), but did show a small positive relationship to injectable drug use. Kanayama et al. (2003b) reported that those who used AAS were statistically significantly more likely to report non-alcohol substance use but a marginally significant difference between users and non-users emerged with respect to use of any illicit drug. Wichstrøm (2006) reported that use of hard drugs was not statistically significantly related to use of AAS 5-years or 7-years later. Thus, nearly 78.6% (n=11) of the studies that reported bivariate analyses indicated a positive relationship between use of AAS and illicit substances, about 14.3% (n=2) reported mixed results and about 7% (n=1) reported no statistically significant relationships between the two substances.

3.4.2 Multivariate Analyses

Ten studies reported the results of multivariate analyses that examined the relationship between AAS use and use of other drugs. In six studies the dependent variable was lifetime AAS use. In these studies lifetime AAS use was positively predicted by recent use of a variety of illicit drugs including, but not limited to, cocaine, tranquilizers, stimulants and heroin (McCabe et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2005; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001). Other studies reported that lifetime AAS use was positively predicted by lifetime use of a variety of illicit drug including, but not limited to, tranquilizers, sedatives, and cocaine (Kindlundh et al., 1999; Kokkevi et al., 2008; Pallesen et al., 2006). One study found that use of illegal drugs and injectable drugs within the past 30-days predicted the likelihood that one had used AAS during their lifetime (DuRant et al., 1995).

Although a majority of the studies that reported multivariate analyses reported a positive relationship between AAS use and illicit substance use, there were several exceptions. In one study, dependent AAS users were statistically significantly more likely than nondependent AAS users to be dependent on opioids, but the differences between these groups on cocaine dependence were small (Kanayama et al., 2009). In another study, lifetime use of narcotics, crack, and Vicodin predicted likelihood to use AAS, but use of OxyContin, Ritalin and GHB did not (Denham, 2009). In a study by Wichstrøm (2006) illicit drug use failed to predict changes in AAS drug use over a 5-year period. Finally, in a study by Wichstrøm and Pedersen (2001) use of hard drugs and solvents within the previous 12-months were not statistically significant predictors of AAS use. Thus, 60% (n=6) of the studies reported a positive relationship between use of AAS and illicit drug use, 20% (n=2) reported mixed results, and 20% (n=2) failed to find statistically significant relationship between AAS and illicit drug use. These results are displayed in Table 4.

3.5 Legal Performance Enhancing Substances

Four studies included measures of legal PES (Dodge and Jaccard, 2006; Hoffman et al., 2007; Kanayama et al., 2003b; Papadopoulos et al., 2006), but only three reported testing the relationship between use of AAS and legal PES (Dodge and Jaccard, 2006; Hoffman et al., 2007; Papadopoulos et al., 2006).

3.5.1 Bivariate Relationships

Only one study reported bivarate associations. In this study those who reported having used AAS were more likely than those who had never used AAS to report having used legal PES (Papadopoulos et al., 2006).

3.5.2 Multivariate Analyses

All three studies reported results of multivariate analyses. The dependent variable in two studies was lifetime use of AAS, and results of the analyses indicated that use of a legal PES during one’s life increased the likelihood that an individual had used AAS during their lifetime (Hoffman et al., 2007; Papadopoulos et al., 2006). The other study reported that use of legal PES within the past year was a statistically significant positive predictor of the use of AAS within that same time frame (Dodge and Jaccard, 2006). Thus, 100% of the studies reporting multivariate analysis documented a positive relationship between use of AAS and legal PES. These results are shown in Table 4.

4.0 Summary

The present review indicates that the relationship between the use of AAS and other drugs depends on the type of substance assessed. Results of both bivariate and multivariate analyses suggest that the use of AAS is positively associated with use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and legal PES.

In contrast, the relationship between AAS and the use of tobacco and cannabis are mixed. Results of bivariate analyses imply that AAS users are more likely than non-users to have used tobacco and cannabis. However, a less clear picture emerges when inspecting the multivariate analyses. After controlling for other predictors of AAS use, tobacco and cannabis use remained a statistically significant positive predictor of AAS use in fewer than half of the studies.

4.1 Alcohol, Illicit Drugs, and Legal PES

Results of the studies reviewed herein beg the question, why would alcohol, illicit drugs, and legal PES be associated with the use of AAS? This question is probably most easily answered for legal PES. That is, those individuals who want to improve muscle mass may be willing to try any substance that claims to offer such assistance. It may be that the drive to improve muscle mass serves as the common cause for using both legal PES and AAS. Another possibility is that individuals who wish to improve their muscle mass try a legal PES first and then progress to the use of AAS. To distinguish which explanation is accurate requires longitudinal investigations that allow us to examine temporal associations between AAS use and legal PES. Because all of the studies examining the AAS-legal PES relationship are cross-sectional, it is difficult to distinguish between these explanations.

Why AAS use is associated with alcohol or other illicit drug use is less clear. A number of studies have suggested that individuals who are likely to try or experiment with drugs will experiment with many different types of drugs, including AAS (Miller et al., 2005; Nilsson et al., 2005; Pallesen et al., 2006). A majority of the measures in the studies reviewed herein relied on measures of AAS use that reflect experimental AAS use (i.e., whether one has ever used AAS during one’s life) and, thus, are consistent with this explanation.

However, the relationship between habitual AAS use and alcohol and other drug use remains less clear. This is because a majority of the published studies to date do not speak to the relationship between habitual AAS use and the use of other drugs, despite evidence suggesting that habitual AAS users differ from experimental users (Kanayama et al., 2006; Kanayama et al., 2009).

There are several possibilities that emerge with respect to the relationship between habitual AAS use and the use of other drugs. One possibility is that habitual AAS users are individuals who are likely to try or experiment with a variety of drugs, which is consistent with the rationale described above. Another possibility, however, is that the relationship between habitual AAS use and other drug use varies based on the type of other drug studied. For example, those who are habitual users of AAS often begin using AAS because they are dissatisfied with their physique (Kanayama et al., 2003a; Kanayama et al., 2006). This dissatisfaction may lead them to use drugs that will help escape such feelings while having minimal impact on physical performance. Furthermore, habitual AAS users may be more likely than non-users to use drugs that mask the pain of strenuous physical workouts. The study by Kanayama et al., (2009) lend further support to the idea that the relationship between habitual AAS use and other drug use varies by drug type as those who were dependent on AAS showed a greater proclivity toward dependence on opioids, but not other drugs (e.g., alcohol, cocaine) than did those individuals who were not dependent on AAS.

The relationship between habitual AAS use and other drug use is critical to understand because without such an understanding the best approach to prevention and treatment will remain unclear. If habitual use of AAS is associated with the use of other drugs, it may be possible for prevention and treatment efforts to target the use of multiple substances. It also suggests that existing drug treatment programs may be effective for the treatment of AAS abuse. However, if habitual AAS use is not associated with the use of other drugs it may be necessary to focus on prevention and treatment programs that specifically target habitual AAS users.

4.2 Tobacco and Cannabis

While univariate analyses are consistent with the idea that users of AAS are more likely than non-users to use tobacco and cannabis, results of multivariate analyses are mixed. In those studies reporting multivariate analyses, tobacco and cannabis use were statistically significant predictors of AAS use in fewer than half. Future research should continue to investigate the relationships between AAS use and the use of tobacco and cannabis.

4.3 Limitations

There are several limitations that must be mentioned. One limitation is with the measurement of AAS use in anonymous surveys that used ambiguous questions about "steroids." For example, two studies that were included in the review (DuRant et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2005) relied on an assessment of AAS use that may be problematic (Thompson et al., 1993; Kanayama et al., 2007). These studies asked adolescents whether they had ever used steroids without a doctor’s prescription. This wording may lead to an exaggerated number of false positives because it does not distinguish between the illegal use of steroids and use of legal steroids like hydrocortisone for poison ivy (Thompson et al., 1993). The wording may also lead to false positives if adolescents used over-the-counter supplements that they inaccurately assumed were steroids (Kanayama et al., 2007). Several other studies included in this review used similarly worded items that failed to distinguish among use of illegal AAS to improve athletic performance and use of steroids for other health reasons (Kokkevi et al., 2008; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001). However, most of these studies report that involvement in sport or weightlifting is positively associated with the AAS use measure (DuRant et al., 1995; Kokkevi et al., 2008; Pedersen and Wichstrøm, 2001), which at least suggests that adolescents in the sample are using AAS to improve physical performance and not solely for other health reasons. Nonetheless overestimations of AAS use would bias magnitude estimations of the relationship between AAS use and use of other drugs. Moving forward, it is critical for researchers to design measures to circumvent this problem.

Another limitation is that the measures of drug use often varied even for the same type of drug. For example, the measures of alcohol use ranged from ever having had a drink (Kindlundh et al., 1999; Luetkemeier et al., 1995) to frequency of drunkenness (Denham 2009; Papadopoulos et al., 2006) and alcohol dependence (Kanayama et al., 2009). This makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the relationship between AAS use and specific types of drinking behavior. Furthermore, many of the studies relied on analysis of data that was collected for purposes other than testing for an AAS-drug use relationship highlighting the need for more a priori, theory-driven research. Researchers should begin to develop hypotheses about which types of drinking behaviors are expected to be related to AAS use as well as those not expected to be related to AAS use and design specific tests of these hypotheses. A similar logic extends to the use of other drugs (e.g., illicit drugs). Results of the present paper can aid in generating these hypotheses.

As mentioned earlier, a majority of the items used to assess AAS use were relatively crude and failed to capture fine differences between frequency or amount of AAS use and other drug use. In addition, a majority of the studies relied almost exclusively on adolescent school-based samples, so the extent to which the results of the studies generalize to other populations is not clear. In many studies AAS use was predicted from recent drug use, and all but one of the studies reviewed above were cross-sectional in nature, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions about temporal associations between AAS and the use of other drugs.

4.4 Conclusions

Despite the limitations mentioned above, the existing studies on AAS and other drug use provide a number of conclusions and offer directions for future research. For example, the studies reviewed above indicate that the relationship between AAS use and other drug use differs based on the type of drug studied. The studies reviewed suggest that those who experiment with AAS are more likely than those who do not experiment with AAS to use alcohol, legal PES, and illicit drugs. However, the relationship between experimental use of AAS and use of tobacco and cannabis is less clear. The measures of AAS use included in the studies tended to reflect experimental use of AAS rather than habitual use. Thus, there is very little data that can inform us of whether habitual AAS use serves as a risk factor for the use of other drug use or vice versa. Taken together the literature reviewed above highlight the need to develop studies tailored to specifically study the link between habitual AAS use and the use of other drugs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

A review of risk factors for adolescent AAS use, conducted by Barhke et al. (2000), included a section on polypharmacy. We decided to go back to the year 1995 so that we could identify articles that assessed legal PES use in addition to other drugs, something that was absent in the Barhke et al. (2000) review.

Two studies that met inclusion criteria were excluded (Miller et al., 2002a; Miller et al., 2002b) because they used the same data set (1997 Youth Risk Behaivor Survey) as a study that was retained for the review (Miller et al. 2005). Four studies that met the inclusion criteria were excluded because the measure of AAS use was a composite measure of AAS use and use of other drugs that were either legal or not necessarily used to enhance performance (e.g., creatine, stimulants, narcotics, diuretics; Buckman et al., 2009; Kartakoullis et al., 2008; Laure and Binsinger 2007; Striegel, et al., 2006).

In the study by McCabe et al. (2007) they conducted multi-level analyses that controlled for gender, marital status, age, sport status, and commuter/non-commuter school. The level 2 analyses did not control for use of other drugs. In the study by Denham (2009), lifetime alcohol use was the drug entered as a covariate across analyses.

References

- Bahrke MS, Yesalis CE, Kopstein AN, Stephens JA. Risk factors associated with anabolic-androgenic steroid use. Sports Med. 2000;29:397–405. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200029060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beel A, Maycock B, McClean N. Current perspectives on anabolic steroids. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1998;17:87–103. doi: 10.1080/09595239800187631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolding G, Sherr L, Elford J. Use of anabolic steroids and associated health risks among gay men attending London gyms. Addiction. 2002;97:195–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman JF, Yusko DA, White HR, Pandina RJ. Risk profile of male college athletes who use performance-enhancing substances. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:919–922. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner A, Thieme D. Side effects of anabolic androgenic steroids: Pathological findings and structure-activity relationships. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2010;195:459–484. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79088-4_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi PYL, Pope HG. Violence toward women and illicit androgenic-anabolic steroid use. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 1994;6:21–25. doi: 10.3109/10401239409148835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham BE. Association between narcotic use and anabolic-androgenic steroid use among American adolescents. Subst. Use Misuse. 2003;44:2043–2061. doi: 10.3109/10826080902848749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge TL, Jaccard JJ. The effect of high school sports participation on the use of performance-enhancing substances in young adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health. 2006;39:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham BE. Association between narcotic use and anbolic-androgenic steroid use among American adolescents. Subst. Use Misuse. 2009;44:2043–2061. doi: 10.3109/10826080902848749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Escobedo LG, Heath GW. Anabolic-steroid use, strength training, and multiple drug use among adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1995;96:23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JR, Faigenbaum AD, Ratamess NA, Ross R, Kang J, Tenenbaum G. Nutritional supplementation and anabolic steroid use in adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007;40:15–24. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Cohane GH, Weiss RD, Pope HG. Past anabolic-androgenic steroid use among men admitted for substance abuse treatment: an unrecognized problem. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2003a;64:156–160. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Pope HG, Jr, Cohane G, Hudson JI. Risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid use among weightlifters: A case-control study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003b;71:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Barry S, Hudson JI, Pope HG. Body image and attitudes toward male roles in anabolic-androgenic steroid users. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:697–703. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Boynes M, Hudson JI, Field AE, Pope HG. Anabolic steroid abuse among teenage girls: An illusory problem? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Hudson JI, Pope HG. Features of men with anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: A comparison with nondependent AAS users and with AAS nonusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartakoullis NL, Phellas C, Pouloukas S, Petrou M, Loizou C. The use of anabolic steroids and other prohibited substances by gym enthusiasts in Cyprus. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport. 2008;43:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kindlundh AMS, Isacson DGL, Berglund L, Nyberg F. Factors associated with adolescent use of doping agents: Anabolic-androgenic steroids. Addiction. 1999;94:543–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9445439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkevi A, Fotiou A, Chileva A, Nociar A, Miller P. Daily exercise and anabolic steroids use in adolescents: A cross-national European study. Subst. Use Misuse. 2008;43:2053–2065. doi: 10.1080/10826080802279342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetkemeier MJ, Bainbridge CN, Walker J, Brown DB, Eisenman PA. Anabolic-androgenic steroids: Prevalence, knowledge, and attitudes in junior and senior high school students. J. Health Educ. 1995;26:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Brower KJ, West BT, Nelson TF, Wechsler H. Trends in non-medical use of anabolic steroids by U.S. college students: Results from four national surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meilman PW, Crace RK, Presley CA, Lyerla R. Beyond performance enhancement: Polypharmacy among collegiate users of steroids. J. Am. Coll. Health. 1995;44:98–104. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1995.9939101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Barnes GM, Sabo D, Melnick MJ, Farrell MP. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use and other adolescent problem behaviors: rethinking the male athlete assumption. Sociol. Perspect. 2002a;45:467–489. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Barnes GM, Sabo D, Melnick MJ, Farrell MP. A comparison of health risk behavior in adolescent users of anabolic-androgenic steroids, by gender and athlete status. Sociol. Sport J. 2002b;19:385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Hoffman JH, Barnes GM, Sabo D, Melnick MJ, Farrell MP. Adolescent anabolic steroid use, gender, physical activity, and other problem behaviors. Subst. Use Misuse. 2005;40:1637–1657. doi: 10.1080/10826080500222727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen MS, Rämö MP, Viitasalo M, Heikkilä P, Karjalainen J, Mäntysaari M, Heikkilä J. Serious cardiovascular side effects of large doses of anabolic steroids in weight lifters. Eur. Heart J. 1996;17:1576–1583. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Spak F, Marklund B, Baigi A, Allebeck P. Attitudes and behaviors with regards to androgenic anabolic steroids among male adolescents in a county of Sweden. Subst. Use Misuse. 2005;40:1–12. doi: 10.1081/ja-200030485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S, Jøsendal O, Johnsen B, Larsen S, Molde H. Anabolic steroid use in high school students. Subst. Use Misuse. 2006;41:1705–1717. doi: 10.1080/10826080601006367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos FC, Skalkidis I, Parkkari J, Petridou E. Doping use among tertiary education students in six developed countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2006;21:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-0018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen W, Wichstrøm L. Adolescents, doping agents, and drug use: A community study. J. Drug Issues. 2001;31:517–542. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Ramirez K, Montalto PR, Sisk CL. Anabolic steroids have long-lasting effects on male social behaviors. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;208:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santora LJ, Marin J, Vangrow J, Minegar C, Robinson M, Mora J, Friede G. Coronary calcification in body builders using anabolic steroids. Prev. Cardiol. 2006;9:198–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2006.05210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel H, Simon P, Frisch S, Roecker K, Dietz K, Dickhuth HH, Ulrich R. Anabolic ergogenic substance users in fitness-sports: A distinct group supported by the health care system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;81:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ML, Martinez CM, Gallagher EJ. Atrial fibrillation and anabolic steroids. J. Emerg. Med. 1999;17:851–857. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PD, Zmuda JM, Catlin DH. Use of anabolic steroids among adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:888–889. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309163291219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrøm L. Predictors of future anabolic androgenic steroid use. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1578–1583. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000227541.66540.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrøm L, Pedersen W. Use of anabolic-androgenic steroids in adolescence: Winning, looking good or being bad? J. Stud. Alcohol. 2001;62:5–13. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesalis CE, editor. Anabolic steroids in sport and exercise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2000. [Google Scholar]