Abstract

Background and objective. Out-of-hours services for primary care provision are increasing in policy relevance. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore service users’ recent experiences of out-of-hours services and to identify suggestions for improvement for services and practitioners involved.

Methods. We used data from a cross-sectional survey of service users’ self-reported experiences of 13 out-of-hours centres in Wales. Three hundred and forty-one respondents provided free-text comments focusing on suggestions for improvement within the survey instrument (the Out-of-hours Patient Questionnaire). A coding framework was based on previous literature focusing on patients’ experiences of out-of-hours services, built upon and refined as it was systematically applied to the data. Emergent themes and subthemes were charted and interpreted to comprise the findings.

Results. Central themes emerged from users’ perspectives of the structure of out-of-hours services, process of care and outcomes for users. Themes included long waiting times, perceived quality of service user–practitioner communication, consideration for parents and children and accessibility of the service and medication. Suggestions for improving care were made across these themes, including triaging patients more effectively and efficiently, addressing specific aspects of practitioners’ communication with patients, reconsidering the size of areas covered by services and number of professionals required for the population covered, extending GP and pharmacy opening times and medication delivery services.

Conclusions. It is important to consider ways to address service users’ principal concerns surrounding out-of-hours services. Debate is required about prioritizing and implementing potential improvements to out-of-hours services in the light of resource constraints.

Keywords: Framework analysis, improvements, out-of-hours care, patients’ experiences, qualitative

Background

Evaluation of out-of-hours primary care in the UK is increasingly important due to the changing nature of service provision,1 the differences between provision across both rural and urban settings2 and the increasing political attention on quality and safety of these services (particularly in the UK). Assessments of the quality of service provision may be informed by considering users’ experiences of out-of-hours care, which are important to ensure the implementation of user-centred services3 and to promote the active participation of citizens and communities in service development. Improvements to services may be based on patient-led designs, which are informed by considering people’s views of existing services.4 Whenever change is planned, service users and staff should have the strongest voice in identifying what is required.4

Service users’ varying levels of awareness of what constitutes standard provision within out-of-hours care, and their expectations of the services,2 may influence their perceptions of the care received. Studies of users’ evaluations of out-of-hours services have researched users’ preferences,5 expectations of care,6–8 satisfaction with care,9,10 perceived quality of practitioner–patient communication5,11 and factors relating to follow-up care by user’s own GPs after contact with an out-of-hours service.12

A study examining geographical variations in the delivery of out-of-hours care suggests that variation in access to care may be affected by a combination of factors, which include the time of day the service is contacted, how the service is organized, the level of demand, user characteristics (such as age and access to transport) and the size of the area covered by a service.13 Furthermore, users’ individual circumstances may present possible additional factors and influence their reason for accessing the service or their experience of the service. For example, a study in the Netherlands found that most parents consulted out-of-hours primary care services for their children because they were motivated more to prevent or rule out serious disease rather than in response to presenting conditions themselves.14 In another study, older people demonstrated reluctance to use out-of-hours and telephone advice services based around less personal models of care, preferring contact with a familiar doctor.15

Whether a service meets patients’ expectations may reflect their satisfaction with a service, yet not necessarily the quality of the service received. Differences in satisfaction between forms of service delivery have been identified.10 When patients expected a treatment centre consultation or a home visit but only received a nurse telephone consultation, they were less satisfied overall9 and more negative about the accessibility of the service and the nurse telephone consultation, specifically.8 Furthermore, those who wait longer for a consultation may be less satisfied.9 It has been suggested that if people are more enabled, they may be less likely to use unscheduled care services or different services in the same and subsequent illness episodes.3

A systematic review identified reduced user satisfaction when in-person consultations are replaced by telephone consultations.1 Increased information needs and help-seeking behaviour during the week following the out-of-hours consultation were reported by service users who received telephone advice.10 In order to identify why such issues occur and vary across out-of-hours service models, we need to explore service users’ experiences. Users’ appraisals of both new and pre-existing out-of-hours services and their practitioners need to be understood to inform which aspects of out-of-hours care need to be improved.

Using qualitative data from a cross-sectional survey of out-of-hours service consultations [the Out-of-hours Patient Questionnaire (OPQ)],16 the aim of this study was to explore, via their free-text comments, a large number of service users’ self-reported experiences and suggestions for improvements following a recent out-of-hours service encounter in the UK. The focus was to identify areas where problems have arisen, which, in turn, may identify suggestions for improvement, both for the services and for the practitioners involved. This was a secondary analysis of the survey’s qualitative data, following the principal quantitative analysis from the OPQ.17,18

Method

This study was a secondary analysis of the survey data, the primary aim being to analyse the OPQ. The primary data from the questionnaire have been reported by Kinnersley et al.18 and Kelly et al.17 Face-to-face interviews are an effective qualitative methodology to the address the research question in depth;19 however, analysis of the free-text comments from the survey instrument also provide opportunity to obtain the views of a more extensive sample.

Setting

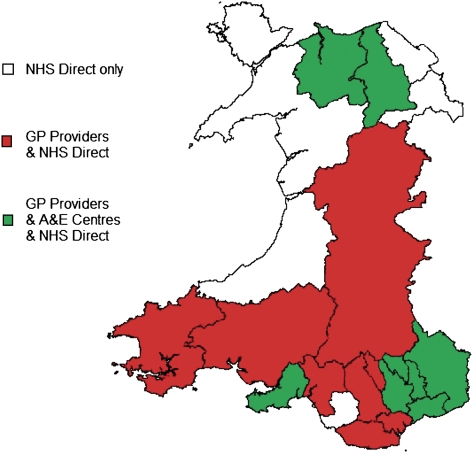

Recent service users were recruited from 13 sites. These comprised 9 of the 13 GP out-of-hours service providers in Wales (the remaining 4 declining to participate), NHS Direct and three A and E centres (see Fig. 1). NHS Direct (all Wales) and A and E centres within three geographical areas were chosen for their urban, mixed and rural characteristics (in Swansea, Gwent and Conwy and Denbighshire, respectively). The GP out-of-hours services are different in terms of whether they are provided by GP cooperatives, trusts (i.e. NHS hospitals) or for-profit companies, but each GP service provides the options of telephone advice, a treatment centre consultation or a home visit. NHS Direct provides telephone advice only and the A and E centres provide face-to-face consultations as necessary.

FIGURE 1.

The geographical area covered by the participating providers.

Participants

Out-of-hours providers were asked to identify users of their services during the previous month. For patients ≤10 years old, their parents or guardians were contacted to take part in the survey. Users were excluded if they were known to have died, were terminally ill, were aged 11–15 years (for confidentiality reasons) or known to be unable to participate in surveys. For GP out-of-hours providers who deliver telephone advice, treatment centre care and home visits, a random sample of 250 users was chosen (randomization by remote random number generation, applied to consecutive eligible user lists). These comprised 100 who had telephone advice, 90 who had attended a treatment centre and 60 who had a home visit.16 The sample size was sufficient for parallel quantitative analysis of the OPQ instrument and provided a large dataset for qualitative research. For providers only providing treatment centre care (NHS A and E centres) or only providing telephone advice (NHS Direct), a random sample of 250 service users was chosen. As this was a secondary analysis, users were not sampled according to qualitative methodologies, i.e. to identify subjects to capture a range of experiences.

Data collection

Sampling took place following out-of-hours contacts in 2007–08. Three thousand two hundred and fifty surveys were administered from the 13 participating centres. Respondents were asked to provide free-text comments focusing on suggestions for improvement within the survey instrument (the OPQ).16 Information about the study, an invitation to participate and the questionnaire were mailed to the selected service users by the providers with a return stamped addressed envelope. After 2 weeks, a single reminder was sent.

Data analysis

This study was set up to be a secondary analysis, using thematic analysis, with techniques from the framework approach developed in the UK for applied policy research.20 This qualitative method of analysis is a five-stage process, which includes familiarization with the data and previous literature, identifying a thematic framework, indexing (applying the thematic framework systematically to all the data), charting (devising charts for each theme across all respondents) and mapping and interpretation.20 This approach was adopted because a review of existing literature relating to patients’ experiences of out-of-hours care provided a relevant basis for an initial framework within which the free-text comments could be coded. All the data were coded, including responses relating to pharmacies. This thematic framework was built upon and refined as it was systematically applied to the data by one researcher (RP) using NVivo 8 computer software. Emergent themes, subthemes and potential relationships between themes were charted and consequently interpreted to comprise the findings, including interpretation according to the type of service or setting that the user had experienced. A quarter of the data were double-coded to check for consistency, for which there was >90% agreement between researchers (RP and AG). Quotes are presented in the results to illustrate the themes and subthemes identified.

Results

Three hundred and forty-one respondents provided free-text comments within the survey instrument (the OPQ), describing their satisfaction with their experiences and suggestions for improvement to services. This was 39.9% of the 855 returned surveys in total and 10.5% of the overall 3250 surveys issued. Many of those who responded had definite views about the service they received, and it is possible that the many more who did not respond did not have suggestions for improvement. The following central themes were identified within the data (see Table 1) and will be presented with their corresponding subthemes alongside quotations as examples. The central themes, which emerged were accessibility (subthemes: waiting time, problems receiving home visits, difficulty accessing a service, difficulty accessing medication and difficulty accessing a face-to-face consultation), ineffective and inefficient triaging, quality of service user–practitioner communication, lack of consideration for parents and children, satisfaction with treatment and users’ ability to cope with condition and health outcomes. These central themes will be presented in order of their corresponding contexts: structure of services, process of care and outcomes for patients and service users (see Table 1). Following these themes, a summary of service users’ recommendations for out-of-hours services will be presented.

Table 1.

Table of themes

| Central theme | subtheme | Context |

| Accessibility | Waiting time—too long for a service response | Structure of services |

| Problems receiving home visits | Structure of services and process of care | |

| Difficulty accessing a service | Structure of services | |

| Difficulty accessing medication | Structure of services | |

| Difficulty accessing a face-to-face consultation | Structure of services and process of care | |

| Ineffective and inefficient triaging | Process of care | |

| Quality of service user–practitioner communication | Process of care | |

| Lack of consideration for parents and children | Process of care | |

| Satisfaction with treatment | Outcomes for patients and service users | |

| Users’ ability to cope with condition and health outcomes | Outcomes for patients and service users | |

Positive comments relating to out-of-hours services and practitioners accounted for a small proportion of responses within the data, and almost all consisted of one word, such as ‘good’ oxr ‘satisfactory’. As the focus of this research was to explore experiences and identify suggestions for improvements, the positive responses lacked sufficient detail for analysis.

Structure of services

Within the context of the structure of services, the overarching theme identified was accessibility, with five subthemes. These are waiting time—too long for a service response, problems receiving home visits, difficulty accessing a service or medication and difficulty accessing a face-to-face consultation.

Waiting time—too long for a service response

Eighty-one comments related to service users’ feeling that they had waited too long for a service response. Some waited a long time between their initial telephone call to the service and their subsequent appointment time. Parents with young children found a long wait to see a doctor particularly difficult and distressing for them and their children.

Many service users who called services to speak to a doctor over the telephone reported waiting between half an hour to 3 hours and felt that they should have been told by the initial call handler to expect this. It was suggested that employing more staff to handle users’ telephone queries would reduce the waiting time for doctors to return telephone calls. Additionally, some service users recommended that calls need to be answered sooner, reporting that they were ‘put on hold’ for 10–15 minutes.

I phoned up at 09:00 to be told the doctor would call me back. Doctor rang after an hour and said they couldn’t give me anything without seeing me. My appointment was made for 19:40 that evening when all the chemists are shut. Treatment centre user, age 45, Private sector provider, South Wales [valleys (‘valleys’ refers to the South Wales valleys, characterised by post-industrialised towns and smaller communities, formerly mining, steel and heavy industry based) and rural].

Many patients reported waiting for a home visit for up to 8 hours, which was deemed unacceptable—especially for older patients. Six patients who reported waiting too long for an ambulance waited between 5 hours and all day. When some out-of-hours service users were instructed to contact their GP the next day, they viewed it as unhelpful—especially if they required immediate attention.

Eighteen service users recommended that the out-of-hours service employ more doctors and general staff. Most felt that this measure may reduce waiting times for patients, although others felt that employing more doctors would enable doctors to spend more time with patients. A specific suggestion from six service users was that more specialist doctors are needed out-of-hours. Three service users who needed emergency treatment from a dentist out-of-hours could not be seen because there were no out-of-hours dentists.

I was unable to get an emergency appointment at my dentist for four days. Due to the extent of the pain (now diagnosed as infected wisdom tooth) I had been to A&E 36 hours prior. A&E doesn’t treat dental pain. The [Health Board] should look at emergency cover for such things. North Wales A&E Treatment Centre user, aged 24.

Problems receiving home visits

Forty service users reported a preference for receiving a home visit from a doctor. Eleven of these reported that the doctor refused to come out see to the patient and a further 10 complained of doctors’ reluctance to visit patients. There were no reflections from service users that indicated an understanding of why they were unable to receive a home visit.

The GP is very reluctant to visit at home—they say come to the surgery. I can hardly walk, besides what was wrong with me at the time. Telephone advice, healthcare helpline user, age 76.

It was felt that consideration should be given to service users’ individual circumstances—those who reported a preference to see the doctor at home were mostly parents with young children but also middle aged and older people, sole carers and people with a disability. Parents felt that for unwell children, the doctor should not refuse to visit the home. Parents report difficulty with getting small children ready to visit the surgery and with taking them out late at night when they are ill. Other reasons for service users needing a doctor to visit the home were because the patient was too ill to travel, the distance for the patient to travel was too far and patients had no access to transport.

More consideration should be given to individual circumstances, i.e. emergency treatment was needed but receptionist unwilling to get doctor to visit at home. I had four children at home and no vehicle to get to the hospital. Treatment could have been delayed or compromised. Treatment centre user (parent), GP Co-operative, North East Wales (town & rural)

Difficulty accessing a service

Service users who had difficulty accessing out-of-hours care were mostly parents of young children and those without access to transport. Home visits would have been these service users’ preferred mode of consultation; alternatively, it was suggested that out-of-hours treatment centres should provide transport so that they may attend.

Provide transport for sick people who do not have their own transport. Evening public service buses for sick people is not acceptable when having to make a journey to the out-of-hours service. Open service at [city] Hospital for [locality] residents. A taxi to [town] and back could cost so much for a pensioner. They fail to get immediate treatment because of distance and cost. Treatment centre user, age 49, Private sector provider, South Wales (valleys and rural).

Thirty-one comments were from service users complaining that the distance travelled to access care from the out-of-hours service was too far due to the size of the area covered by a service. The average distance travelled by service users to see a doctor was 21 miles, and some travelled 30 miles to access a rural service. Service users related the difficulty of travelling long distances to see a doctor, especially for appointments late at night or when needing an ambulance and the need for improved area coverage of a service.

Many service users living outside the catchment area of their nearest out-of-hours centre expressed a preference for seeing a doctor at a local hospital, which was nearer to their home. It was also suggested that local surgeries, which are closer than their nearest out-of-hours centre, should have extended opening times, such as evenings, Saturday mornings and for emergencies at weekends. Service users who had to travel much further than their local hospital or A and E centre felt that more doctors should be employed locally out-of-hours at a hospital or treatment centre.

More doctors! Our nearest A&E ([town]) is closed during out-of-hours due to lack of doctors! It's disgraceful. We had to travel to ([city)] hospital where we had a three hour wait due to the fact there was only one doctor in the whole department! South West Wales A&E Treatment Centre user (parent).

Some mismatches of service provision and users’ preferences were identified. Some service users reflected on continuity of care regarding a preference for seeing one’s own doctor and for discussing matters locally rather than with NHS Direct or visiting a surgery at a distance from the home. A few who preferred to be seen by an out-of-hours GP were told to make contact with emergency services (999 and A and E); however, they felt that dialling 999 made use of a service that may have been needed more urgently by someone else. Other specific issues relating to access included suggestions that parking arrangements at treatment centres could be improved and that free parking, clear signposting and an emergency bell within the car park would be helpful—especially for those with cardiac or respiratory problems, where the entrance is at a distance from the parking space.

Difficulty accessing medication

Twenty-two comments from service users described their difficulty in obtaining their medication out-of-hours. Service users had to travel long distances to arrive at a pharmacy (often >20 miles) to find that the pharmacy was shut or medication was not readily available, and some doctors prescribed medication that was no longer available. Many service users had to wait 2 days to receive medication. It was stressed that patients should be able to receive medication at the same time they receive a prescription, and pharmacies should be open out-of-hours and near to treatment centres. For some service users, those without means of transport, with a disability, or the elderly needing assistance to access a pharmacy, it was suggested that those without assistance would benefit from a medication delivery service.

Difficulty accessing a face-to-face consultation

Some service users experienced difficulty in accessing a face-to-face consultation with a doctor when wanted:

It was difficult to get [healthcare helpline] to let my child see a doctor. They insisted on just giving advice. I eventually had to drive to the out-of-hours GP and demand to be seen. I felt their advice was poor as my child's symptoms were difficult to describe (due to age and inability to describe pain). South West Wales A&E Treatment Centre user (parent).

Process of care

Within the context of the process of care, the main themes of ineffective and inefficient triaging, quality of service user–practitioner communication and lack of consideration for parents and children were identified.

Ineffective and inefficient triaging

Many service users attributed their long wait to speak to a doctor to the triaging process. Frustrations with repeating oneself to different members of staff who asked the same questions were commonly expressed. Additionally, the relevance of the type of information sought in different circumstances was criticized—not least because it was felt that such unnecessary questions delayed receiving immediate help in an emergency. For some, their condition meant that it was very difficult to repeat answers to these questions.

Receptionists were also reported to misinform service users by offering medical advice, and some users complained about their apparent role in deciding which patients they considered to require priority treatment. In some cases, the receptionist delayed passing on information to the doctor, which, in one instance, resulted in adverse consequences for the patient who needed an emergency operation.

Equally, triage nurses were criticized for not recognizing symptoms that require emergency treatment and their consequent reluctance to enable users to consult a doctor. Many users would have preferred to speak with a doctor directly.

Not having used Out-of-Hours I was dismayed as the triage nurse indicated that due to my age I did not fulfil the criteria for a house call! Absurd when absolutely housebound—i.e. E-coli—acute infective colitis. However I was given the opportunity to speak to a doctor. The doctor attended and delivered an exceptional standard of care. I was admitted immediately via a '999' ambulance—very quickly due to significant blood loss. Home visit, GP co-operative user, age 58.

Twenty service users described problems with the exchange of patient information. It was distressing to service users when they had to make many phone calls to access a service, having too many telephone numbers to manage, especially in one instance where the user suffered seizures. It was suggested that the receptionist should manage contact numbers. Some service users recommended that information regarding users’ medical history and medication should be provided for out-of-hours services—this would also enable services to quickly identify ‘at risk’ users. Incorrect details for users were noted by three respondents.

Quality of service user–practitioner communication

A high proportion of service users commented on their perceptions of user–practitioner communication. In some instances, practitioners were praised for their communication skills, whereas in other instances, improvements in communication were recommended. Doctors were criticized for not explaining matters clearly, not listening to patients, lack of empathy and poor spoken English and comprehension. Eleven users reported problems with doctors of a non-English-speaking background. Users found practitioners with poor or broken English difficult to understand due to both language skills and accent. Because of this language barrier, patients could not understand the diagnosis or advice given and felt that the practitioner did not understand them. Additionally, in three of these encounters, the doctor appeared rushed.

The doctor who rang me back had broken English and was very rushed. We had to phone back to be clear as to what was happening next. The actual doctor who visited was excellent. This could have caused problems for elderly [citizens] etc. Home visit, GP Co-operative user, aged 32, North East Wales (town & rural).

Thirteen respondents highlighted the need for practitioners to explain to users what they may be suffering from in simple terms and provide information on illnesses, repeat prescriptions and support groups. Furthermore, some users felt that they were given inaccurate advice by practitioners who did not listen to them, and 12 suggested that longer consultations are needed for practitioners to take more time with users and to be able to understand what the user tells them. Eleven service users felt that practitioners showed a lack of understanding, care or concern, and some felt that the practitioner did not respect their reasons for contacting the service and reported that they were made to feel ‘like a nuisance’ or ‘like an overanxious parent’.

They need to listen to their patients more and give them a chance to voice their problems. Also, they need to take a little more time with the patient before rushing them out. North Wales A&E Treatment Centre user, aged 20

Lack of consideration for parents and children

Thirty service users indicated that services and practitioners should demonstrate more consideration for parents and children. Parents identified issues relating to the care received, which relate to the aforementioned themes of accessibility, ineffective and inefficient triaging and quality of service user–practitioner communication.

Outcomes for patients and service users

Many service users commented that the care received within the out-of-hours service consultation impacted upon patients’ health outcomes. Within the context of outcomes for patients and service users, the main themes of satisfaction with treatment and users’ ability to cope with condition and health outcomes were identified.

Satisfaction with treatment

Twenty-five service users specifically noted that they found the out-of-hours treatment they received to be unsatisfactory. A few service users were given inaccurate advice or no advice regarding what to do if symptoms worsened. Others were disappointed with a lack of treatment or a lack of after care. Some service users felt that a thorough examination by the doctor was required, but not received, so they were dissatisfied with the quality of care. Nine users reported that the doctor they consulted appeared inexperienced, unprofessional or reacted inappropriately towards the patient (for example, appearing reluctant to touch a patient who had motor neurone disease and unacquainted with the illness, as in one instance).

Occasionally doctors come to see our service users for catheter issues—on two occasions comments passed that ‘if nursing home, nurses should do’. Fair comment when patient has ‘normal’ history, but doctors should appreciate nurses would not call them out unnecessarily—only when ‘special’ circumstances like catheter etc. Home visit, user aged 53, Private sector provider, North Wales (rural).

Users’ ability to cope with condition and health outcomes

The comments relating to users’ ability to cope with their condition and health outcomes result from users’ perceived failures of the service to offer the right care to enable them to cope. Thirty-two service users noted that they felt that their condition had worsened following the out-of-hours consultation. On occasions, users reported that their condition had deteriorated due to not receiving a home visit. Some service users reported being misinformed when receiving telephone advice for the symptoms, and others complained that the out-of-hours doctor they saw did not prescribe medication for the presenting illness. Consequently, users reported suffering further until an appointment could be made with a local GP surgery within regular hours.

I had to take my child back to GP on following Monday and was prescribed two weeks of penicillin for the same illness. My child suffered two days without treatment! Treatment centre user (parent), Private sector provider, North Wales (rural).

Had I been given antibiotics when I went to see the doctor on call I feel that my asthma would not get as bad. I had to visit my own GP and I was given antibiotics and had to have two weeks off work. Treatment centre user, aged 46, Health Board GP Co-operative, South West Wales (rural).

Summary of service users’ recommendations for out-of-hours services

A number of problems relating to structure of services, process of care and outcomes for users have been identified; however, respondents also recommended several potential solutions relating to the issues of accessibility, communication, visiting patients and triaging patients. These are summarized in Table 2. Potential suggestions included extended opening hours for local GP surgeries and pharmacies, more doctors and dentists employed out-of-hours (including at local hospitals and treatment centres not currently providing out-of-hours services), doctors to take more time to listen to patients and explain matters in simple terms and a re-examination of the triage process.

Table 2.

Summary of service users’ recommendations for out-of-hours (OOH) services

| Structure of services | Process of care |

| Accessibility | Communication |

| • Reduce waiting times for service response | • Provide information and updates on waiting times |

| • Provide more home visits | |

| • Extend opening times of local GP surgeries and pharmacies | Doctors |

| • Consider service users’ preference for receiving a local service | • Provide more information on illnesses, actions to take if symptoms worsen, repeat prescriptions, patient support groups and after care |

| • Provide transport for those otherwise unable to attend a treatment centre | |

| • Reduce the size of the area covered by an OOH service | |

| • Provide OOH pharmacies near to OOH treatment centres | • Listen to patients and understand what they say |

| • Provide a medication delivery service for patients otherwise unable to access medication | • Explain illnesses in simple terms |

| • Improve spoken English and comprehension | |

| • Ensure diagnosis or advice given is understood | |

| • Take more time with patients and never ‘rush the patient out’ | |

| • Demonstrate better understanding, care and respect towards patients | |

| Visiting patients | |

| • Provide free parking at OOH centres and emergency bells in remote OOH centre car parks | Address doctors’ refusal or reluctance to visit patients |

| • Access patients’ medical histories and medications | |

| • Employ more OOH doctors, general staff and specialist practitioners (especially dentists) | Consider patients’ individual circumstances and review indications for home visits for parents with young children, older patients, sole carers, disabled patients, patients too ill to travel, patients who would otherwise travel too far and patients without access to transport |

| • Employ OOH doctors at local hospitals and treatment centres currently without an OOH service | |

| Triaging patients | |

| • Consider more appointments to see an OOH doctor for service users receiving telephone advice | |

| • Eliminate question repetition within the triaging process | |

| • Re-examine the relevance of information sought within the triaging process for different circumstances | |

| • Ensure that receptionists do not give medical advice | |

| • Ensure that triage nurses and receptionists refer patients with symptoms that require emergency attention and pass on important information from patient to doctor immediately | |

| • Enable the patient to consult a doctor directly rather than another member staff, if requested |

Discussion

Main findings

The main themes identified within this study, which reflect service users’ experiences of out-of-hours care include accessibility (specifically: waiting times, problems receiving home visits and difficulties accessing a service or medication or getting a face-to-face consultation), ineffective and inefficient triaging, quality of service user–practitioner communication, lack of consideration for parents and children, satisfaction with treatment and users’ ability to cope with condition and health outcomes.

Suggestions from service users for the improvement of these out-of-hours services in the UK principally concern accessibility, practitioner communication, lack of home visits and ineffective and inefficient triage. Service users want reduced waiting times for service response, more home visits and do not want to travel long distances to receive out-of-hours care. They suggest that local GP surgeries and pharmacies should have extended opening hours and more doctors and dentists should be employed out-of-hours, including at local hospitals and treatment centres not currently providing out-of-hours services. Service users suggest that doctors should listen to patients more, explain matters in simple terms, improve their spoken English and not ‘rush the patient out’. Many service users felt that doctors’ reluctance or refusal to visit patients should be addressed and that their individual circumstances should be considered, especially for parents with young children. Finally, service users suggest a re-examination of the triage process regarding question repetition, the relevance of information sought, inappropriate advice given by some receptionists and the authority of triage nurses and receptionists to decide whether or not a patient is a ‘priority’ and should consult a doctor.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study has a large sample size for qualitative research. Despite this, there was a low response rate, so it is unlikely to include the full range of service users’ views. Sampling was undertaken for quantitative representativeness, for the primary questionnaire analysis rather than seeking sample variation. However, inspection of the data suggests that although responses were mostly negative or advisory in nature, there were other positive and neutral perspectives. Many of those who responded had definite views about the service they received, and it is possible that the many more who did not respond did not have suggestions for improvement. The findings can be interpreted alongside both quantitative analyses17,18 and in depth qualitative interviews with a smaller sample,19 providing user perspectives on the areas that need improvement—and specifically—some of the ways that a range of users feel these areas can be improved.

A limitation of this study is that the small proportion of positive responses, which lacked sufficient detail regarding the nature of experiences, were not subsequently followed up to elicit further information. This highlights a limitation of the analysis of free-text comments in this context as it does not allow the opportunity to probe respondents for further detail. Ideally, following up service users who provided very brief positive remarks could provide insight into what worked well and balance possible negative bias in the reported findings.

Free-text comments in the questionnaire also do not prompt respondents to explore any potential contradictions or trade-offs within their suggestions for improvements (for example, a service user may suggest that more home visits are needed yet also acknowledge that this may result in longer waiting times at the treatment centre). We acknowledge that there may have been cases where users’ judgement of the process of care or structure of services was biased by a negative health outcome, which may or may not have been possible to change at the time they consulted the out-of-hours service.

Context of other literature

These findings are consistent with a recent policy review issued by the Department of Health on out-of-hours services, which makes recommendations for Primary Care Trusts (PCT) to review their commissioning and performance management of out-of-hours services, the selection, induction, training and use of out-of-hours clinicians and the management and operation of Medical Performers Lists (including guidance to assess whether a doctor has necessary knowledge of English).21 The match between user expectations and what is provided as an important determination of satisfaction is consistent with other studies.3,8 Our finding that the quality of user–practitioner communication is of particular importance to service users resonates with findings elsewhere that ‘whether the doctor seemed to listen’ was considered the most important attribute to users,5 and an assessment of the communication skills of telephone triagists at Dutch out-of-hours centres revealed specific shortcomings and learning points to improve the quality of communication11—the researchers suggest training should be more patient-centred and that sufficient time is needed for the consultation.11 In addition to these key considerations for service improvements, findings from our sample of service providers in Wales, UK, provide several more specific recommendations (Table 2) about how the services might be improved. The analysis of the free-text comments supported findings from the quantitative analysis about problems at the interface between out-of-hours care and either in-hours or self-care;18 it also supported findings on the implications of unsatisfactory care in terms of subsequent re-accessing services or re-consulting for the same episode from the analysis of telephone interviews with patients.19 In addition, the findings from the free-text responses show several specific aspects relating to service accessibility, communication, visiting and triage that can be considered in service development and training for staff. The data emphasize the inefficiency of repeated questioning and delays between each stage of triage and advice. However, users’ perceptions of repeated questioning may not necessarily be in their best interests as clinicians may need to repeat questions to ensure correct treatment.

Implications for practice and research

If out-of-hours services can be improved, we may see a reduction in further in-hours or out-of-hours service contacts for the same illness episode after the initial out-of-hours contact.3 If we take into account service users’ suggestions for improvements of out-of-hours service provision, it may enable patients to access out-of-hours treatment when and where care is needed, may increase service users’ satisfaction with the treatment received and reduce stress and frustration. High levels of user satisfaction with out-of-hours services may increase user confidence and adherence to clinical advice and improve clinical outcomes.7 If practitioners and service providers take steps to ensure effective communication skills, users are likely to feel more reassured, respected and cared for; will be more likely to receive safe appropriate care when listened to; will better understand diagnoses and will be more able to follow advice. Interventions to make such improvements all require evaluation of their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Future research may need to examine the barriers to implementing some of the recommendations suggested and how these may be overcome within existing service models.

The high level of political attention to the quality and safety of GP out-of-hours services, particularly in the UK, makes the need to identify effective and cost-effective interventions to improve services paramount. It is important to consider ways to address service users’ principal concerns surrounding out-of-hours services. Solutions for many of the concerns raised require more funding, and some may not be realistic or affordable. Debate is required about prioritizing and implementing selected potential improvements to out-of-hours services in the light of resource constraints.

Declaration

Funding: Wales Office of Research and Development (06/2/216).

Ethical approval: Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee approval (05/MRE09/35).

Conflict of interest: none.

Acknowledgments

We thank the respondents to the survey and staff from the participating centres or services for assistance with administration of surveys and invitation to participate. The authors also thank other members of the research group who participated in the planning, delivery, analysis and interpretation of research findings: Prof. Paul Kinnersley, Kerry Hood, Helen Snooks, Mrs Sue Bowden, Drs Chris Shaw, Lori Button, Mark Kelly and Eleri Owen-Jones.

References

- 1.Leibowitz R, Day S, Dunt D. A systematic review of the effect of different models of after-hours primary medical care services on clinical outcome, medical workload, and patient and GP satisfaction. Fam Pract. 2003;20:311–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell J, Roland M, Richards S, et al. Users’ reports and evaluations of out-of-hours health care and the UK national quality requirements: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:e8–15. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X394815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egbunike JN, Shaw C, Bale S, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Understanding patient experience of out-of-hours general practitioner services in South Wales: a qualitative study. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:649–54. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.052001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wales Assembly Government. Designed for Life: Creating World Class Health and Social Care for Wales in the 21st Century. National Assembly for Wales, Cardiff, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott A, Watson MS, Ross S. Eliciting preferences of the community for out of hours care provided by general practitioners: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:803–14. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKinley RK, Stevenson K, Adams S, Manku-Scott TK. Meeting patient expectations of care: the major determinant of satisfaction with out-of-hours primary medical care? Fam Pract. 2002;19:333–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson K, Parahoo K, Farrell B. An evaluation of a GP out-of-hours services: meeting patient expectations of care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10:467–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2004.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giesen P, Charante EMv, Mokkink H, et al. Patients evaluate accessibility and nurse telephone consultations in out-of-hours GP care: determinants of a negative evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;65:131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salisbury C. Postal survey of patients’ satisfaction with a general practice out of hours cooperative. BMJ. 1997;314:1594–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7094.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shipman C, Payne F, Hooper R, Dale J. Patient satisfaction with out-of-hours services; how do GP co-operatives compare with deputizing and practice-based arrangements? J Public Health Med. 2000;22:149–54. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derkx HP, Rethans J-JE, Maiburg BH, et al. Quality of communication during telephone triage at Dutch out-of-hours centres. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:174–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uden CJTv, Zwietering PJ, Hobma SO, et al. Follow-up care by patient’s own general practitioner after contact with out-of-hours care. A descriptive study. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pooley CG, Briggs J, Gatrell T, et al. Contacting your GP when the service is closed: issues of location and access. Health Place. 2003;9:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(02)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hugenholz M, Bröer C, Daalen Rv. Apprehensive parents: a qualitative study of parents seeking immediate primary care for their children. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:173–9. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X394996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster J, Dale J, Jessopp L. A qualitative study of older people’s views of out-of-hours services. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:719. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell JL, Dickens A, Richards SH, et al. Capturing users’ experience of UK out-of-hours primary medical care: piloting and psychometric properties of the Out-of-hours Patient Questionnaire. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:462–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.020172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly M, Egbunike JN, Kinnersley P, et al. Delays in response and triage times may reduce patient satisfaction and enablement after using out-of-hours services. Fam Pract. 2010;27:652–663. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinnersley P, Egbunike JN, Kelly M, et al. The need to improve the interface between in-hours and out-of-hours GP care and between out-of-hours care and self-care. Fam Pract. 2010;27:664–672. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egbunike JN, Shaw C, Porter A, et al. Exploring patient experience of out-of-hours care across Wales: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:e83–97. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. London: Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colin-Thomé D, Field S. General Practice Out-of-Hours Services: Project to Consider and Assess Current Arrangements. London: Department of Health. 2010. [Google Scholar]