Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Prevention of paraplegia following repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms (TAAA) requires understanding the anatomy and physiology of the blood supply to the spinal cord. Recent laboratory studies and clinical observations suggest that a robust collateral network must exist to explain preservation of spinal cord perfusion when segmental vessels are interrupted. An anatomical study was undertaken.

METHODS

Twelve juvenile Yorkshire pigs underwent aortic cannulation and infusion of a low-viscosity acrylic resin at physiological pressures. After curing of the resin and digestion of all organic tissue, the anatomy of the blood supply to the spinal cord was studied grossly and using light and electron microscopy.

RESULTS

All vascular structures ≥ 8μm in diameter were preserved. Thoracic and lumbar segmental arteries (SAs) give rise not only to the anterior spinal artery (ASA), but to an extensive paraspinous network feeding the erector spinae, iliopsoas, and associated muscles. The ASA, mean diameter 134±20 μm, is connected at multiple points to repetitive circular epidural arteries with mean diameters of 150±26 μm. The capacity of the paraspinous muscular network is 25-fold the capacity of the circular epidural arterial network and ASA combined. Extensive arterial collateralization is apparent between the intraspinal and paraspinous networks, and within each network. Only 75% of all SAs provide direct ASA-supplying branches.

CONCLUSIONS

The ASA is only one component of an extensive paraspinous and intraspinal collateral vascular network. This network provides an anatomic explanation of the physiological resiliency of spinal cord perfusion when SAs are sacrificed during TAAA repair.

Keywords: Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm, Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm, Spinal cord blood supply, Spinal cord perfusion, Paraplegia/Paraparesis, Collateral Network, Spinal cord vascular anatomy

BACKGROUND

A thorough understanding of the anatomy of the blood supply of the spinal cord would appear to be essential for developing optimal strategies to prevent spinal cord injury during and after open surgical or endovascular repair of extensive thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms (TAA/A). But direct visualization of these vessels is difficult clinically, (1–5) and thus most surgeons continue to rely upon descriptions of the spinal cord circulation derived from a few classic anatomic studies. (6–8) The most influential of these has been the treatise by Albert W. Adamkiewicz (1850–1921), whose meticulously detailed and beautiful drawings suggest that the most important input into the anterior spinal artery is a single dominant branch of a segmental artery in the lower thoracic or upper lumbar region, with a characteristic hairpin turn, which is now often referred to as the artery of Adamkiewicz.(9)

The consensus has been that identification and then reimplantation of the segmental artery supporting this important artery during repair of TAA/A is the best possible strategy for preserving spinal cord blood supply and thereby preventing paraplegia or paraparesis.(1, 2, 4, 10–12) But despite various painstaking and inventive techniques to avoid spinal cord injury using this approach, there continues to be a definite seemingly irreducible incidence of paraplegia and paraparesis following treatment of extensive TAAA. (4, 12–14) Furthermore, reattaching the artery of Adamkiewicz or other large intercostal or lumbar arteries—already a daunting undertaking during open surgical repair—is not really possible using current endovascular techniques. So, the combined incentives of trying to avoid the rare but devastating occurrence of paraplegia following surgical repair of TAAA, and the appealing future prospect of utilizing endovascular techniques for treating extensive TAAA make it seem reasonable to reassess our understanding of the spinal cord circulation with the aim of developing a strategy which will assure postoperative spinal cord perfusion adequate to prevent paraplegia without reattaching segmental arteries.(15, 16)

We therefore undertook a series of anatomical explorations in the pig, which previous studies have documented has a spinal cord circulation very similar in its physiological responses to that of man. These anatomic studies, described here for the first time in detail, establish the presence of an extensive collateral network which supports spinal cord perfusion. Our anatomic findings buttress previous clinical and experimental observations which suggested that such a network is present both in man and in the pig.(16–18)

Putting together all our evidence to date, the collateral system involves an extensive axial arterial network in the spinal canal, the paravertebral tissues, and the paraspinous muscles, in which vessels anastomose with one another and with the nutrient arteries of the spinal cord.(19) The configuration of the arterial network—both in man and in the pig—includes inputs not only from the segmental vessels (intercostals and lumbars), but also from the subclavian and the hypogastric arteries.(20) The presence of this extensive network implies a considerable reserve to assure spinal cord perfusion if some inputs are compromised, but also presents opportunities for vascular steal. The aim of this study is to describe the collateral network in sufficient detail to allow appreciation of its potential benefits as well as vulnerabilities in order to lay a sound foundation for development of strategies to prevent paraplegia following TAA/A repair.

METHODS

Twelve female juvenile Yorkshire pigs (Animal Biotech Industries, Allentown, NJ, U.S.A.) weighing 12±2 (range: 10–13) kg underwent standard aortic cannulation and total body perfusion with a low-viscosity acrylic resin (800ml, Batsons Nr. 17, Anatomical Corrosion Kit, Polysciences Inc, Warrington, PA, www.polysciences.com) to create a vascular cast of the circulation. Perfusion was carried out using extracorporeal circulation (the cardiopulmonary bypass circuit without an oxygenator), at physiological pressures with pulsatile flow in order to achieve filling of all vessels, including capillaries.

As has previously been described, the anatomy of the pig differs from that of humans in having thirteen thoracic vertebrae. The first three thoracic segmental arteries are branches of the left subclavian; the subsequent ten thoracic and five lumbar arteries arise together from the aorta and then divide (20, 21). Previous studies suggest that the subclavian arteries and the median sacral arteries each play a major role in the perfusion of the paraspinous collateral vascular network in both species, although the iliac arteries may provide a greater proportion of the direct blood supply in humans than in pigs (20). Previous experiments with this model have demonstrated that spinal cord perfusion pressure and collateral flow in the pig behave in ways very similar to what is observed under comparable circumstances clinically in humans (18, 22, 23).

After curing of the resin and digestion of all organic tissue as described below, the anatomy of the blood supply to the spinal cord, and especially its interconnections with the vasculature of adjacent muscles, was studied grossly, and in detail using light and electron microscopy. To visualize vessels contributing to the blood supply of the spinal cord and for better comparison of the porcine vascular cast with human anatomy, selected vascular casts were scanned and processed for 3D image reconstruction in a CT scanner.

Perioperative management and anesthesia

All animals received humane care in compliance with the guidelines of ‘Principles of Laboratory Animal Care’ formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the ‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’ published by the National Institute of Health (NIH Publication No. 88–23, revised 1996). The Mount Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocols for all experiments.

After pre-treatment with intramuscular ketamine (15 mg/kg) and atropine (0.03 mg/kg), an endotracheal tube was placed. The animals were then transferred to the operating room and were mechanically ventilated. Anesthesia was induced and maintained as described previously (18). An arterial line was placed in the right brachial artery for pressure monitoring prior to and during resin perfusion.

Operative technique and acrylic resin perfusion

The chest was opened through a small left thoracotomy in the fourth intercostal space. The pericardium was opened and the heart and great vessels were identified. After heparinization (300 IU/kg), the right atrium was cannulated with a 26F single-stage cannula, and the aortic arch with a 16F arterial cannula. The CPB circuit consisted of roller heads without an oxygenator and heat exchanger. The animal was perfused and blood washout accomplished with 1,800 mL 0.9% saline and 4,000 IU heparin. The reservoir of the pump was then loaded with low-viscosity acrylic resin. After a clamp had been placed across the proximal ascending aorta to prevent leaking of resin across the aortic valve, whole body perfusion was started at physiologic pressures while exsanguination was achieved through the venous cannula. Perfusion pressures were monitored via a right axillary catheter and a pressure line connected to the aortic inflow tubing. Peak pressure was 120 to 130 mmHg, achieving complete filling of all vascular structures ≥8μm in diameter. The pump was stopped and the lines clamped after the concentration of the acrylic resin in the right atrium reached 80%.

Cast processing

The resin was allowed to cure for 24 hours at room temperature. Thereafter, the paraspinous structures were dissected en bloc, reserving all spinal and paraspinous bony, muscular and central nervous tissues. All organic tissue was dissolved in a bath of 10N KOH solution in specially designed tubs using an active stirring device to accelerate tissue dissolution. During the next 3–7 days, the acrylic casts were removed daily from the KOH bath, and organic debris was carefully removed before re-immersion. At the end of the cleaning process, all casts underwent multi-step analysis.

Cast analysis

The anatomy of the spinal cord blood supply and its connections with the vasculature of adjacent muscles was investigated grossly, and using light and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Each cast was analyzed with focus on the axial arterial network within the spinal canal and in the paraspinous muscles. Collateral anastomoses were identified and the vessel network described in detail, quantifying vessel volumes and diameters.

Light Microscopy

For visualization of the intraspinal vascular structures, the spinal canal was exposed by removing the dorsal processes and washing the intraspinal portion of the cast. Images of the intraspinal vessels (anterior spinal artery and epidural arcades) were obtained at every segmental level. The digital image files were used for measurements of intraspinal vessel diameters using ImageTool 3.0 image analysis software (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

A scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S 4300 scanning electron microscope; cold field SEM, http://www.hhtc.ca/microscopes/sem) was used to visualize the microstructure of the arterial network. Each sample was cleaned in a warm distilled water bath to remove organic remnants and calcium for a minimum of 10 days prior to gold coating for SEM using a Technics Hummer V Sputter Coater.

SEM imaging data were systematically acquired and subjected to morphometric study using ImageTool 3.0 image analysis software (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Angio CT scanning and three dimensional reconstructions of selected casts allowed for digital processing and collection of data regarding spatial configuration. The studies were designed to enable accurate quantification of the configuration and capacity of the vascular network supplying both the spinal cord and the muscles and other tissues adjacent to it.

Quantification of cast volumes

For evaluation of blood volume distribution among the different collateral systems (intraspinal, paraspinal) of a single segmental artery, five non-adjacent segments, which were representative in their macroscopic appearance and had optimal perfusion results, were dissected from the cast tissue block. Cast volume was calculated from cast weight and resin density (Density of Batson’s Nr. 17 Resin = 1.18 g/ml, calculated by polymerized resin block). The cast of the paraspinous vascular tree was separated from all vessels directly supplying the anterior spinal circulation (anterior radiculo-medullary arteries) and the epidural arcades. Intraspinal and extraspinal cast volumes were calculated by weighing each of the different parts of the disassembled vascular model.

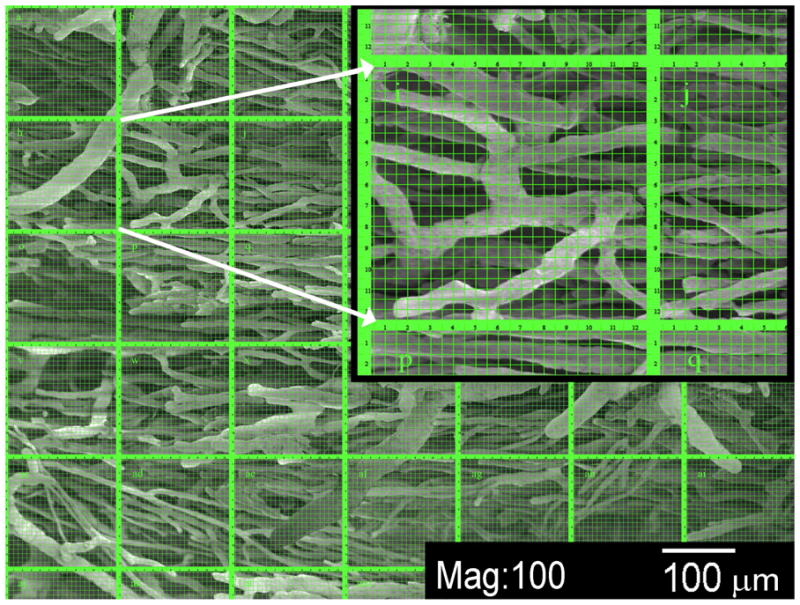

SEM quantification of vessel diameter distribution

For morphometric analysis of the vascular networks, an overview image (x80) was used to identify representative areas of the vascular cast specimen with good perfusion. Pictures were taken of these areas at various magnifications (x100, x200, x400). All image data were stored as digital files and processed for morphometric analysis. Contrast within each image file was adjusted to achieve optimal visualization of as many vessels as possible. A counting grid (35 single squares, 0.034 mm2 each, images x100) was projected onto the original image file with an x- and y- axis in every square (Adobe® Photoshop CS 2). The grid was used for spatial orientation within the image, and to assure an even and random distribution of measurements. The vessels to be measured were chosen from lists of random numbers used as coordinates within the counting grid. Two measurements per square were analyzed using ImageTool 3.0 image analysis software (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio [UTHSCSA]).

Arterial vessels were identified according to SEM morphologic criteria defining arterioles: sharply demarcated and longitudinally oriented endothelial nuclear imprints, oval in shape. The distribution of the measured vessel diameters within the paraspinous networks was systematically assessed.

Statistical Methods

Data were entered in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Wash) and transferred to an SAS file (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) for data description and analysis; data are described as percents, median (range) or means (standard deviation).

RESULTS

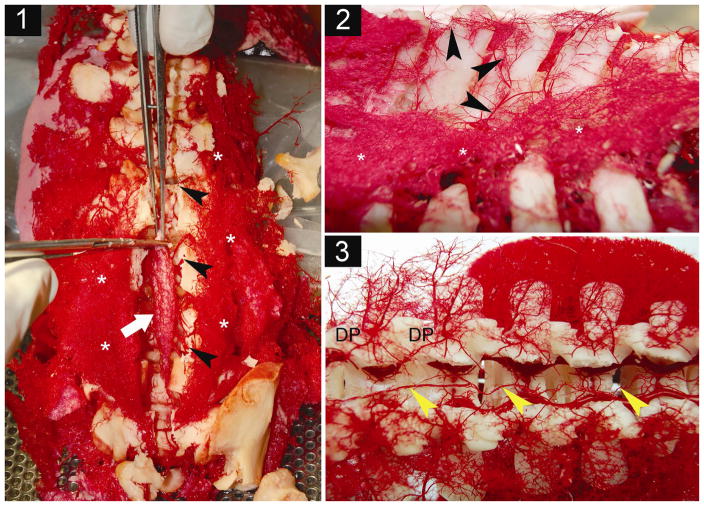

The vascular system supplying the spinal cord (including segmental arteries, radiculo-medullary arteries, and the anterior spinal artery) and its adjacent tissues (including the vertebrae, and erector spinae and psoas muscles) was cast in its entirety in each animal (Figures 1 and 2). The polymeric resin reached networks of small arterioles, capillaries (with diameters less than 7 μm) as well as venules.

Figure 1. Processing of the acrylic cast.

1.1 After soft tissue maceration and multiple cleaning steps using distilled water, the spinal canal (black arrows) is opened dorsally by cutting the pedicles of the vertebrae. The casts of spinal cord arteries (white arrow: lower lumber cord) are dissected and freed from neural and glial tissues. Asterisks: lower paraspinous musculature. 1.2: Lateral view of casts of vessels along dorsal processes show paravertebral extramuscular arcades consisting of arterioles that interconnect segmental levels longitudinally. *extensive vasculature of paraspinous muscles. 1.3: Dorsal view of the opened spinal canal onto the lower thoracic (left) and upper lumbar (right) segments. Yellow arrows show the anterior spinal artery. DP: Distribution points of single dorsal segmental arteries, where the dorsal mainstem divides into an extensive muscular paraspinous vascular tree, giving rise to the different intraspinal branches.

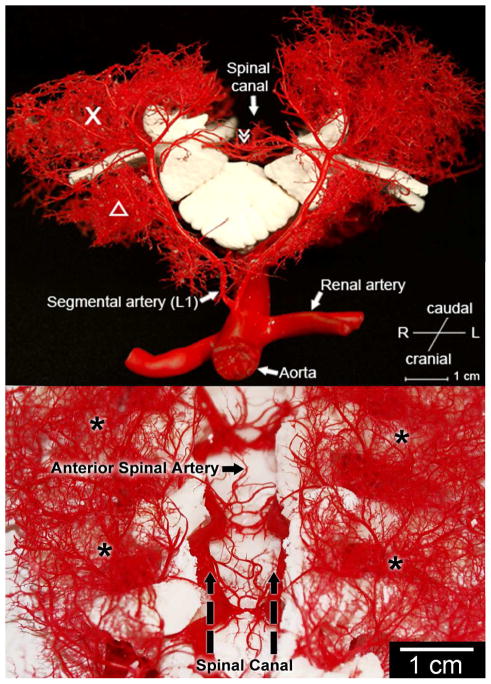

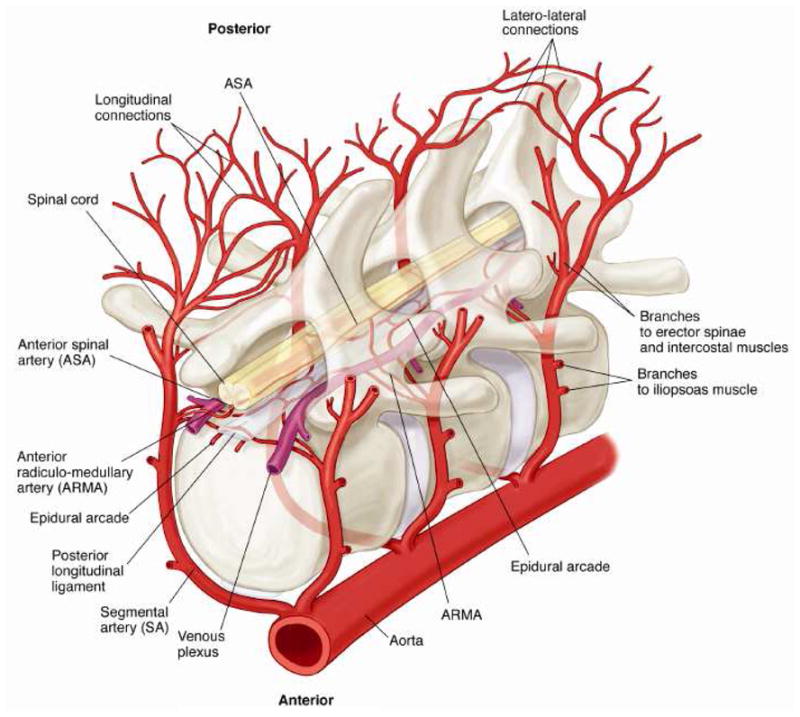

Figure 2. Anatomy of the collateral network : sagittal (A) and dorsal (B) view.

The macroscopic appearance of casts of a pair of dorsal segmental vessels at L1. The dorsal process is removed. X designates the paraspinous muscular vasculature providing extensive longitudinal arterio-arteriolar connections. Δ iliopsoas muscle. ≫ Anterior spinal artery.

Thoracic and lumbar segmental arteries and types of intersegmental connections

The thoracic and lumbar segmental arteries (SAs) give rise to the three major vessel groups which anastomose extensively within each group and with one another, Figures 2 and 3. The first group consists of the intrathecal vessels: the anterior spinal artery (ASA) and a longitudinal chain of epidural arcades lying between the spinal cord and the vertebral bodies, Figures 2 and 3. The second is a group of interconnecting vessels lying outside the spinal canal along the dorsal processes of the vertebral bodies, Figure 1. The third is a massive collection of interconnecting vessels supplying the paraspinous muscles, including the iliopsoas anteriorly and the erector spinae posteriorly.

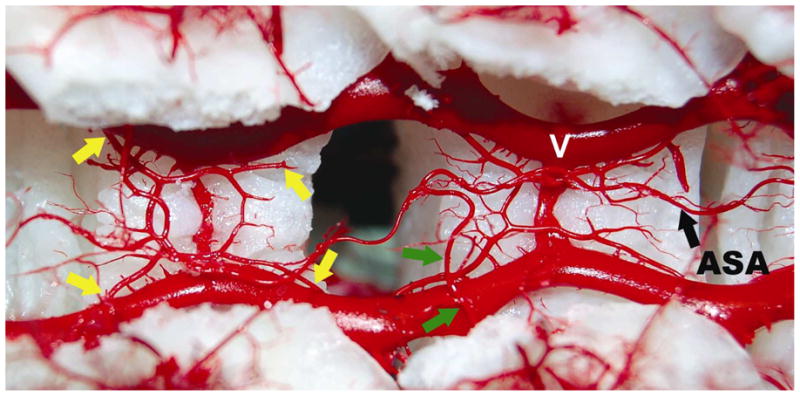

Figure 3. Relationship of anterior spinal artery (ASA) and repetitive epidural arcades.

Dorsal view into the opened spinal canal showing the dorsal surface of two vertebral bodies. The spinal cord is removed to clarify the anatomic location of the epidural circular arcades and anterior spinal artery (ASA). V: epidural venous plexus. Anterior to the extensive venous plexus, four arteriolar branches (yellow arrows) contribute to one circular epidural arcade. This pattern is repeated at the level of each vertebral segment. These vascular structures connect the segments side-to-side as well as longitudinally. They connect with the main stems of the segmental arteries, and can therefore be considered to contribute indirectly to the ASA. Green arrows designate the anterior radiculo-medullary artery, which connects directly with the anterior spinal artery.

Intrathecal vessels, Figures 3 and 4

Figure 4. Schematic Diagram of the Blood Supply to the Spinal Cord.

Schematic diagram demonstrating the relationships, relative sizes and interconnections among the segmental arteries (SA), the anterior radiculomedullary arteries (ARMA) the epidural arcades, and the anterior spinal artery (ASA). Longitudinal anastomoses along the dorsal processes of the spine as well as dorsal communications (interstitial connections) between right and left branches of the SA are also shown.

The intrathecal vessels consist of the anterior spinal artery (ASA), with an average diameter of 134.0 ±20 μm, and the epidural arcades, which have a mean diameter of 150.0 ±26 μm. The ASA is supplied primarily by the anterior radiculo-medullary arteries (ARMAs), filled principally by the left-sided branches of the SAs: 60% of the SAs in the thorax and 82% in the lumbar region provide a direct branch to the ASA.

The epidural arcades consist of a series of circular or polygonal structures at the level of each vertebral body. They form a longitudinal as well as a side-to-side anastomotic network, and connect extensively to the ASA via the ARMAs and branch points from the segmental arteries. Branches from the segmental vessels to the arcades are present at each level from both sides. The combined volume of all the intrathecal vessels--the ASA, the epidural arcades, and the connecting vessels--is 5 μl/segment.

Extrathecal vessels

The first group consists primarily of small branches of the dorsal limbs of the SAs. It is not possible to separate these branches distinctly from the muscular vessels, except for the fact that they are particularly rich in connecting along the long axis of the spine, and also from one side to the other around and posterior to the spinous processes of the vertebral bodies. The plexus of interconnected vessels within the paraspinous muscles-- including the iliopsoas anteriorly and the erector spinae and assorted muscles posteriorly (quadratus lumborum, ileocostalis lumborum, longissimus thoracis)-- dominate the segmental circulation, Figure 2. The volume of these extrathecal vessels is 125 μl/segment, 25-fold the volume of the intrathecal vessels.

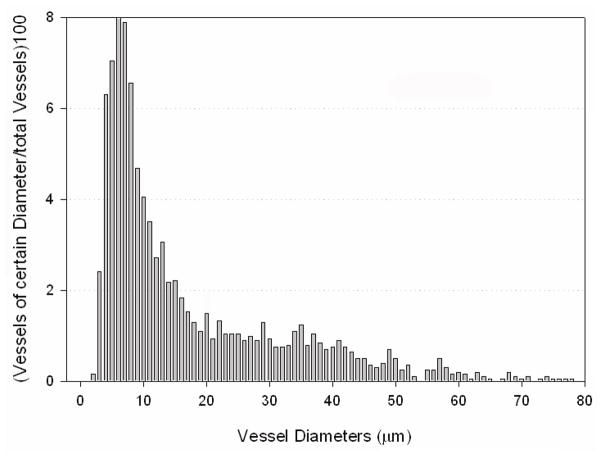

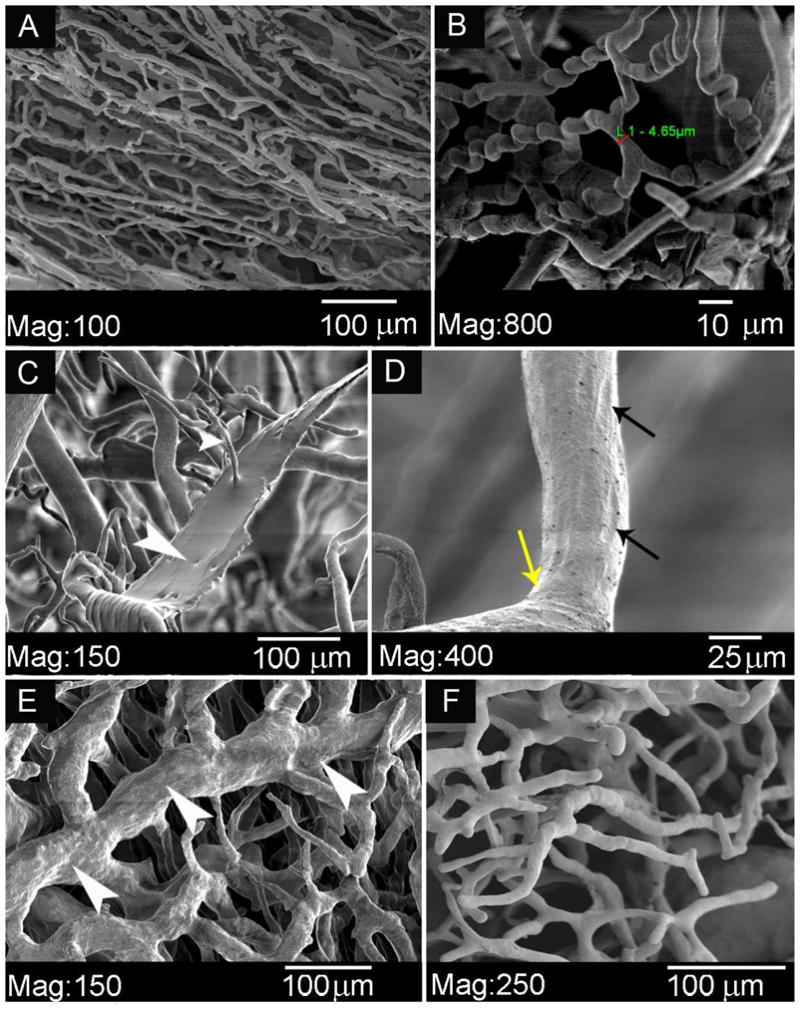

The microanatomy of the intramuscular network is depicted in Figure 6. Arteries and arterioles, veins and venules, and capillaries can be readily distinguished from each other (and from perfusion artifacts). The predominant arterial structures are arterioles between 10 and 40 μm in diameter. The most frequent vessels encountered overall are capillaries, vessels < 10 μm in diameter. Since the emphasis of this study was on the arterial blood supply of the cord, veins and venules were not quantified.

Figure 6. Microanatomy of the collateral network.

An overview of casts of paraspinous vascular structures. A : A capillary micromesh. B : Detail of typical «corkscrew- shaped» capillaries. C: Artifact of acrylic resin which has leaked through a damaged vessel wall. D : Endothelial nuclear imprints on a precapillary arteriole. E : A network of venules, in comparison to F, an arteriolar network.

DISCUSSION

The studies described in this report provide a more detailed anatomic basis than has heretofore been available to substantiate what we have previously described as the collateral network hypothesis of spinal cord blood flow, based chiefly on physiological observations both in man and in the pig (17). The cast studies demonstrate quite dramatically that the previously hypothesized collateral network includes the segmental arteries and the spinal cord circulation, but is dominated by the much more extensive dense, rich vasculature of the paraspinous muscles. It shows that the arteries to the spinal cord, the muscles and the other paravertebral tissues are all interconnected, with multiple longitudinal anastomoses all along the vertebral column.

Although these studies are purely anatomic, and carried out in young pigs for practical reasons, their relevance to the clinical situation is supported by numerous previous physiological studies in which patterns of response in the pig model have proven remarkably similar to observations in patients with aortic disease (16) (24).

The human spinal cord circulation, outlined by quite similar techniques in the commercial exhibit Bodies, shows a convincingly close resemblance to these pig cast studies, but images from that exhibit cannot be published. In 1976 Crock et al. published the results of an anatomical cadaver study describing arterial supply to the vertebral column, cord and nerve roots, in the human (25). Parallels can be drawn between human and porcine segmental blood supply and collateralization when comparing our results to the results described by Crock. For example, as is only shortly described in their article, a repetitive ring-shaped arterial pattern on the dorsal surface of the vertebral bodies is present in man as well, however it has hardly been noticed before and not been systematically described as a, possibly vital, part of a backup-system to restore flow to the cord after loss of direct segmental inflow.

Although it can be argued that the collateral circulation in patients with aneurysms has undergone modifications which may make its response different from that of a young and healthy pig, reliable data regarding these pathological changes and their impact upon physiology are lacking, so this objection to extrapolating from the pig model remains speculative.

The implications of these findings are quite profound. The studies reinforce the idea that the spinal cord circulation is a longitudinally continuous and flexible system, so that input from any single segmental artery along its length is unlikely to be critical. Thus the quest to identify and reattach the elusive artery of Adamkiewicz is a quixotic endeavor (17). Various studies have already demonstrated that the total number of segmental arteries sacrificed during TAAA repair is a more powerful predictor of the risk of paraplegia than the loss of any individual specific SA (13, 26). In fact, systematic attempts to identify and reimplant the putative artery of Adamkiewicz have thus far not succeeded in eliminating paraplegia (4, 12). Furthermore, intercostal patch aneurysms appear to be a significant complication of this approach (27).

The participation of the subclavian and iliac arteries in the spinal cord perfusion network has been confirmed in previous studies, and the explanation for their physiological importance is readily found in the context of the collateral network concept (17, 28). The related possible collateral pathways from the internal thoracic and epigastric arteries providing reversed anterior-posterior flow via the intercostal and lumbar arteries were not visualized in these studies, but probably also contribute collateral flow to the spinal cord and back muscles. The rationale for preserving even distant inputs to the collateral system to assure spinal cord integrity following segmental artery sacrifice is reinforced by understanding the dependence of spinal cord perfusion upon this extensive interconnected collateral network.

One of the initially startling but ultimately unsurprising findings of this study is just how dramatically the muscular arterial component dominates the anatomy of the network when compared to the small arteries which feed the spinal cord directly. This is a reminder of the precarious nature of the spinal cord blood supply: despite the powerful physiological mechanisms which are present to safeguard the integrity of spinal cord perfusion, cord blood supply can be seriously threatened by steal phenomena. The anatomic imbalance between the vascular input to muscle and spinal cord gives us a clear rationale to be meticulous about minimizing the activity of paravertebral muscles during and immediately following TAAA surgery. This can be effected by liberal use of anesthesia and muscle relaxants, and by insistence upon at least moderate hypothermia, which dramatically reduces metabolic rate (in both muscle and spinal cord) and is known to prolong spinal cord ischemic tolerance. Steal from the spinal cord circulation because of demand from muscles is a potent postoperative threat which needs to be added to an already developed awareness of the intraoperative danger of steal from bleeding from open intercostal and/or lumbar arteries. The threat of steal is particularly relevant during the first 12 hours after SA sacrifice, when critical spinal cord ischemia most often occurs (24).

Various adjuncts such as somatosensory and motor evoked potential (SSEP/MEP) monitoring and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage are currently being utilized to maximize spinal cord protection during open and endovascular TAA/A repair, and they have succeeded in reducing the rate of spinal cord injury (14, 16, 29–31). But although the rate of paraplegia/paraparesis after TAAA repair has declined significantly during the past decade, spinal cord injury remains a uniquely devastating complication whose elimination has a high priority in many aortic centers. The recent trend toward an increase in the proportion of cases of delayed rather than immediate neurological injury following surgery for TAAA has highlighted the particular vulnerability of spinal cord perfusion during the first 24 hours postoperatively, a time when monitoring of spinal cord function is difficult (24). The precariousness of spinal cord perfusion during the early hours after surgery has been documented in both the pig model and in patients by direct pressure recordings from vessels in the collateral circuit: this measurement of spinal cord perfusion pressure is a relatively recent and potentially useful additional monitoring technique (18, 19, 23, 24). Ways of minimizing demand from muscles competing for a share of reduced collateral network flow after TAAA repair-- such as postponing rewarming and inhibiting shivering-- may prove effective in improving spinal cord perfusion during this vulnerable interval early postoperatively, and may help to reduce the occurrence of delayed paraplegia.

The importance of the venous circulation within the spinal canal is also apparent from the current anatomical studies (see Figure 3), which show prominent epidural venous channels. Previous clinical observations have suggested that elevated venous pressures can interfere with adequate spinal cord perfusion (24), and certainly the cast pictures make it seem plausible that distended epidural veins within the fixed constraints of the spinal canal could physically obstruct the small arteries in addition to the direct hemodynamic effect of reducing net perfusion pressure.

Although the cast studies thus emphasize vulnerabilities associated with spinal cord perfusion, they also provide reason for optimism with regard to the eventual success of endovascular therapy for extensive TAAA. The existence of a continuous network with multiple potential sources of inflow— rather than the traditional view of a system which depends upon fixed sources which may fall within a region of aortic pathology requiring resection or exclusion— should enable preservation of spinal cord integrity by manipulation of the existing vascular collateral network without requiring technological solutions to restore lost segmental sources of input. Monitoring of pressures within the collateral network suggests that precariously low perfusion pressures only prevail for 24–72 hours postoperatively, with return to preoperative levels of perfusion thereafter (18, 32). Further studies in this promising pig model should clarify how the vascular collateral network compensates to provide a stable increase in spinal cord blood flow, and may furnish clues for shortening the interval of postoperative vulnerability during which, at present, spinal cord ischemia sometimes results in delayed paraplegia.

Conclusions

Cast studies of the perfusion of the spinal cord confirm the existence of a continuous collateral arteriolar network feeding directly and indirectly into the anterior spinal artery along its entire length. The network is dominated by the rich vasculature of the paraspinous muscles, and features multiple longitudinal interconnections as well as input from the intersegmental,. subclavian and iliac arteries.

Figure 5. Cast analysis using scanning electron microscopy.

SEM of paraspinous vascular cast specimens after soft tissue maceration and multiple cleaning steps. The image shows an arteriolar intramuscular network, and the counting grid used for vessel diameter distribution analysis within the collateral network is superimposed upon it. The inset shows detail of a single counting grid, one of a total of 35 per image. The vessels shown have diameters of small precapillary arterioles down to 15 – 20 μm.

Figure 7. Size distribution of capillary and arterioles within the paraspinous collateral network.

The graph shows the distribution of vessels of different diameters (up to 80 μm) within the paraspinous vascular network. The number of times a vessel of a certain diameter was measured is shown as a percentage of the number of all analyzed vessels (n = 2030 total).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Heinemann MK, Brassel F, Herzog T, Dresler C, Becker H, Borst HG. The role of spinal angiography in operations on the thoracic aorta: myth or reality? Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65(2):346–51. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kieffer E, Richard T, Chiras J, Godet G, Cormier E. Preoperative spinal cord arteriography in aneurysmal disease of the descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aorta: preliminary results in 45 patients. Ann Vasc Surg. 1989;3(1):34–46. doi: 10.1016/S0890-5096(06)62382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams GM, Perler BA, Burdick JF, Osterman FA, Jr, Mitchell S, Merine D, et al. Angiographic localization of spinal cord blood supply and its relationship to postoperative paraplegia. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13(1):23–33. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.25611. discussion -5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams GM, Roseborough GS, Webb TH, Perler BA, Krosnick T. Preoperative selective intercostal angiography in patients undergoing thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(2):314–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawaharada N, Morishita K, Fukada J, Yamada A, Muraki S, Hyodoh H, et al. Thoracoabdominal or descending aortic aneurysm repair after preoperative demonstration of the Adamkiewicz artery by magnetic resonance angiography. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21(6):970–4. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazorthes G, Poulhes J, Bastide G, Roulleau J, Chancholle AR. Research on the arterial vascularization of the medulla; applications to medullary pathology. Bull Acad Natl Med. 1957;141(21–23):464–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazorthes G, Poulhes J, Bastide G, Roulleau J, Chancholle AR. Arterial vascularization of the spine; anatomic research and applications in pathology of the spinal cord and aorta. Neurochirurgie. 1958;4(1):3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazorthes G, Gouaze A, Zadeh JO, Santini JJ, Lazorthes Y, Burdin P. Arterial vascularization of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg. 1971;35(September):253–62. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.35.3.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamkiewicz A. Die Blutgefaesse des menschlichen Rueckenmarks. S B Heidelberg Akad Wiss. 1882;Theil I + II(85):101–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams HD, Van Geertruyden HH. Neurologic complications of aortic surgery. Ann Surg. 1956;144(4):574–610. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195610000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svensson LG, Hess KR, Coselli JS, Safi HJ. Influence of segmental arteries, extent, and atriofemoral bypass on postoperative paraplegia after thoracoabdominal aortic operations. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20(2):255–62. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acher CW, Wynn MM, Mell MW, Tefera G, Hoch JR. A quantitative assessment of the impact of intercostal artery reimplantation on paralysis risk in thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):529–40. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318187a792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safi HJ, Miller CC, 3rd, Carr C, Iliopoulos DC, Dorsay DA, Baldwin JC. Importance of intercostal artery reattachment during thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70292-7. discussion -8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cambria RP, Davison JK, Carter C, Brewster DC, Chang Y, Clark KA, et al. Epidural cooling for spinal cord protection during thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: A five-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(6):1093–102. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.106492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griepp RB, Ergin MA, Galla JD, Lansman S, Khan N, Quintana C, et al. Looking for the artery of Adamkiewicz: a quest to minimize paraplegia after operations for aneurysms of the descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112(5):1202–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(96)70133-2. discussion 13–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etz CD, Halstead JC, Spielvogel D, Shahani R, Lazala R, Homann TM, et al. Thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: is reimplantation of spinal cord arteries a waste of time? Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(5):1670–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griepp RB, Griepp EB. Spinal cord perfusion and protection during descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic surgery: the collateral network concept. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(2):S865–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.092. discussion S90–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etz CD, Homann TM, Plestis KA, Zhang N, Luehr M, Weisz DJ, et al. Spinal cord perfusion after extensive segmental artery sacrifice: can paraplegia be prevented? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31(4):643–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etz CD, Homann TM, Luehr M, Kari FA, Weisz DJ, Kleinman G, et al. Spinal cord blood flow and ischemic injury after experimental sacrifice of thoracic and abdominal segmental arteries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33(6):1030–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauch JT, Lauten A, Zhang N, Wahlers T, Griepp RB. Anatomy of spinal cord blood supply in the pig. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(6):2130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazorthes AGG, Zadeh JO, Santini JJ, Lazorthes Y, Burdin P. Arterial vascularization of the spinal cord: recent studies of the anatomic substitution pathways. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:253–62. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.35.3.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etz CD, Homann TM, Luehr M, Kari FA, Weisz DJ, Kleinman G, et al. Spinal cord blood flow and ischemic injury after experimental sacrifice of thoracic and abdominal segmental arteries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Etz CD, Di Luozzo G, Zoli S, Lazala R, Plestis KA, Bodian CA, et al. Direct spinal cord perfusion pressure monitoring in extensive distal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(6):1764–73. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.101. discussion 73–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Etz CD, Luehr M, Kari FA, Bodian CA, Smego D, Plestis KA, et al. Paraplegia after extensive thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: does critical spinal cord ischemia occur postoperatively? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135(2):324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crock HV, Yoshizawa H. The blood supply of the lumbar vertebral column. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;(115):6–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coselli JS, LeMaire SA, de Figueiredo LP, Kirby RP. Paraplegia after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: is dissection a risk factor? Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01029-6. discussion -6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulik A, Allen BT, Kouchoukos NT. Incidence and management of intercostal patch aneurysms after repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138(2):352–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strauch JT, Spielvogel D, Lauten A, Zhang N, Shiang H, Weisz D, et al. Importance of extrasegmental vessels for spinal cord blood supply in a chronic porcine model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24(5):817–24. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estrera AL, Rubenstein FS, Miller CC, 3rd, Huynh TT, Letsou GV, Safi HJ. Descending thoracic aortic aneurysm: surgical approach and treatment using the adjuncts cerebrospinal fluid drainage and distal aortic perfusion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(2):481–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coselli JS, LeMaire SA, Schmittling ZC, Koksoy C. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage in thoracoabdominal aortic surgery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2000;13(4):308–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weigang E, Hartert M, von Samson P, Sircar R, Pitzer K, Genstorfer J, et al. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: interplay of spinal cord protecting modalities. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30(6):624–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etz CD, Di Luozzo G, Zoli S, Lazala R, Plestis KA, Bodian CA, et al. Direct spinal cord perfusion pressure monitoring in extensive distal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.101. in print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]