Abstract

1. The basis of decreased cooperativity in substrate binding in the cytochrome P450 3A4 mutants F213W, F304W and L211F/D214E was studied with fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and absorbance spectroscopy.

2. Whereas in the wild type enzyme the absorbance changes reflecting the interactions with 1-pyrenebutanol exhibit a Hill coefficient (nH) around 1.7 (S50 = 11.7 μM), the mutants showed no cooperativity (nH ≤ 1.1) with unchanged S50 values.

3. Contrary to the premise that the mutants lack one of the two binding sites, the mutants exhibited at least two substrate binding events. The high affinity interaction is characterized by a dissociation constant (KD) ≤ 1.0 μM, whereas the KD of the second binding has the same magnitude as the S50.

4. Theoretical analysis of a two-step binding model suggests that nH values may vary from 1.1 to 2.2 depending on the amplitude of the spin shift caused by the first binding event.

5. Alteration of cooperativity in the mutants is caused by a partial displacement of the “spin-shifting” step. Whereas in the wild type the spin shift occurs in the ternary complex only, the mutants exhibit some spin shift upon binding of the first substrate molecule.

Keywords: P450 allostery, fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET), α-naphthoflavone, 1-pyrenebutanol, spin shift, phenylalanine cluster

Introduction

The major human drug-metabolizing enzyme, cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), represents the most prominent example of homo- and heterotropic cooperativity among cytochromes P450 (see (Davydov and Halpert, 2008; et al., 2009) for review). Cooperativity was originally explained assuming that a single ligand molecule is only loosely bound in the active site, making it necessary for multiple ligands to bind before efficient catalysis can occur (Harlow and Halpert, 1998; Korzekwa et al., 1998). Although simultaneous occupancy of the active site by multiple ligands is now well established (Cupp-Vickery et al., 2000; Hosea et al., 2000; Dabrowski et al., 2002; Baas et al., 2004; Ekroos and Sjogren, 2006), there is increasing evidence that the mechanisms of cooperativity are more complex and involve a ligand-induced conformational transition and possible alteration of P450 oligomerization in the membrane (see (Davydov and Halpert, 2008; Denisov et al., 2009) for review).

Previous studies in this laboratory involved construction and characterization of a series of CYP3A4 mutants that were designed to alter cooperativity (Domanski et al., 1998; Domanski et al., 2001). Of particular interest are the mutants F213W, F304W, and L211F/D214E. These lack homotropic cooperativity of progesterone hydroxylation yet still exhibit activation of both progesterone and testosterone hydroxylation by α-naphthoflavone (ANF). The larger side chains of the substituted residues were originally proposed to mimic effector binding and result in a loss of cooperativity (Harlow and Halpert, 1998; Domanski et al., 2000; Domanski et al., 2001). However, subsequent crystal structures (Williams et al., 2004) indicate that these residues generally point away from the active site. The residues substituted in F213W and F304W are involved in the formation of the so-called phenylalanine cluster at the proximal surface of CYP3A4 that involves Phe213, Phe215, Phe219, Phe220, Phe241, and Phe304. The finding that this cluster is disrupted in the complex of CYP3A4 with ketoconazole (Ekroos and Sjogren, 2006) suggests that this region is involved in the substrate-induced conformational transitions of the enzyme.

Detailed exploration of the altered cooperativity in the mutants F304W, F213W and L211F/D214E may provide important information on the role of the phenylalanine cluster in the molecular mechanisms of cooperativity and related conformational dynamics in CYP3A4. Therefore, in the present study we probe the interactions of these mutants with the substrates ANF, bromocriptine, and 1-pyrenebutanol (1-PB). For this purpose we employed a combination of detection of substrate binding by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) or absorbance spectroscopy with a “titration-by-dilution” approach (Fernando et al., 2006). This allowed us to probe the effect of the mutations on the individual substrate-binding events in the interactions of these mutants with 1-PB, a substrate exhibiting prominent cooperativity with the wild type enzyme.

Our results indicate that, contrary to the initial premise that the mutants lack one of the two substrate binding sites, the mutants exhibited at least two substrate binding events. Alteration of cooperativity in the mutants is caused by a partial displacement of the “spin-shifting” step from the final step of the formation of ternary complex, as it takes place in the wild type, to intermediate step of the binary complex formation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

1-PB was from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), ANF was from Indofine Chemical Company (Hillsbrough, NJ), and bromocriptine mesylate and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin were from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). All other chemicals were of the highest grade available from commercial sources and were used without further purification.

Expression and purification of the CYP3A4 mutants F213W, L211F/D214E and F304W

The enzymes were expressed as the His-tagged protein in Escherichia coli TOPP3 (Harlow and Halpert, 1998). The proteins were purified with a three-column procedure, which includes ion-exchange chromatography on Macro-Prep CM Support as previously described (Tsalkova et al., 2007; Davydov et al., 2010).

Experimental setup

The fluorometric measurements were performed with a combination of either an Edinburgh Instruments FLS920 (Edinburgh Instruments, Edinburgh, UK) or a computerized Hitachi F-2000 spectrofluorometer (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with an S2000 fiber optic CCD spectrometer (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL), which was used to monitor the changes in the transmittance of the sample during the experiment. Both Hitachi and Edinburgh Instruments spectrofluorometers were equipped with a custom-made thermostated cell holder with a direct-path window used to attach the CCD spectrometer via a fiber-optic light guide. This design permitted instant correction of the spectra of fluorescence to compensate for the internal filter effect. The excitation wavelength was set to 331 nm. The spectra of absorbance were measured with an S2000 rapid scanning CCD spectrometer (Ocean Optics, Inc., Dunedin, FL, USA) equipped with an L7893 UV-VIS fiber-optics light source (Hamamatsu Photonics K. K., Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka, Japan) and a custom-made thermostated cell holder with magnetic stirrer. In fluorescence dilution experiments, a 100-μl aliquot of enzyme-substrate mixture of desired stoichiometry was placed in a fluorescence quartz ultra-micro cell with 2 × 10 mm optical chamber (HELLMA GmbH, Müllheim, Germany, Product #105.250). Small aliquots of the buffer were added to the cell up to the maximal volume of the cell (1600 μl). The spectra were recorded after each addition. The experiments were performed at 25° C in 0.1 M Na-Hepes buffer, pH 7.4. All experiments with 1-PB were carried out in the presence of 0.6 mg/ml 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPCD), which was used to increase the solubility of this substrate and prevent the formation of the pyrene excimers. Control experiments showed that the addition of HPCD resulted in a modest increase (~30%) in the values of S50 or KD observed in the absorbance titration experiments but had no effect on the cooperativity (Hill coefficient), spin state of the substrate-free enzyme, or amplitudes of the substrate-induced spin shift (data not shown).

Data Processing

The series of absorbance and fluorescence spectra obtained in titration experiments were analyzed using principal component analysis (PCA) as described previously (Davydov et al., 1995; Renaud et al., 1996). To interpret the spectral transitions in terms of the concentration of P450 species we used a least-squares fitting of the spectra of principal components to the set of spectral standards of pure low-spin, high-spin and P420 species of CYP3A4 (Fernando et al., 2006). Application of PCA to the series of emission spectra obtained in FRET experiments resulted in the first principal component corresponding to the changes in substrate fluorescence and covering over 99% of the total spectral changes. The changes in the loading factor of the first principal component during the experiment were used to calculate the relative changes in the intensity of fluorescence of the substrate. All data treatment procedures and curve fitting were performed using our SPECTRALAB software package (Davydov et al., 1995).

The dependence of the fraction of the high spin heme protein (in absorbance titration experiments) or the loading factor of the first principal component (in FRET studies) on the substrate concentration was used to determine the parameters of the interactions from the fitting of these curves to an appropriate equation using a combination of Marquardt and Nelder-Mead non-linear least squares algorithms as described previously (Davydov et al., 1995). To analyze the results of titration and dilution experiments in those cases when the interpretation of the results did not require an assumption of the involvement of multiple binding events, we used the equation for the equilibrium of bimolecular association ((Segel, 1975), p 73, eq. II-53):

| (1) |

Results

Spin state of the substrate-free F213W, L211F/D214E and F304W mutants

Relative to wild type CYP3A4, all three mutants were characterized by slight displacement of the spin equilibrium of the heme iron towards the high-spin state. Accordingly, the high-spin content in F213W, F304W and L211F/D214E mutants at 25 °C was 16.3 ± 1.7%, 24.2 ± 4.0%, and 24.2 ± 4.0% respectively, compared with 10.9 ± 0.5% in the wild-type. Furthermore, in contrast to what was previously observed with the triple mutant L211F/D214E/F304W (Fernando et al., 2007), the position of the spin equilibrium of the substrate-free F213W, F304W and L211F/D214E mutants did not exhibit any considerable displacement toward high-spin with increasing content of the apo-protein in the enzyme preparations (data not shown).

Interactions of F213W, F304W and L211F/D214E with bromocriptine, 1-PB, and ANF

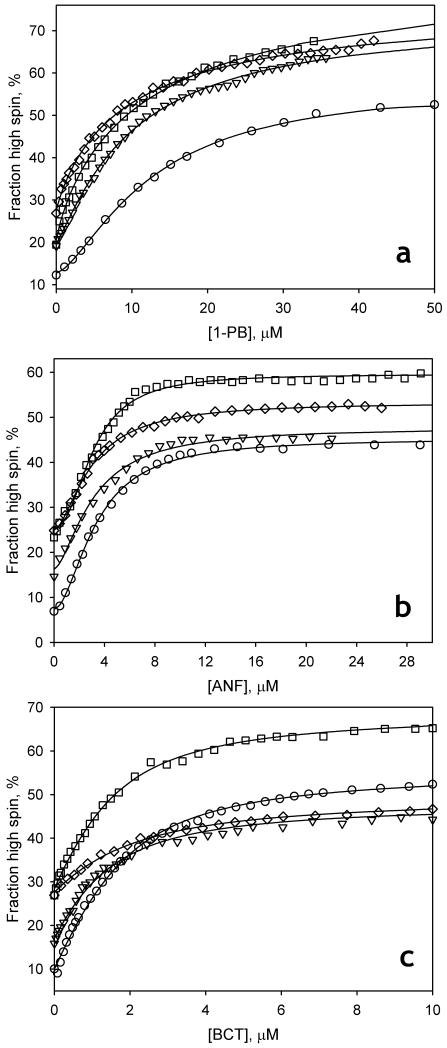

Similar to observations with the wild type enzyme (Fernando et al., 2007; Tsalkova et al., 2007), the interactions of the mutants with all three substrates resulted in a Type I spectral transition corresponding to a shift to high spin. Importantly, all three mutants exhibit a prominent decrease in the homotropic cooperativity with 1-PB, whereas the cooperativity observed with ANF is retained (Fig. 1, Table 1). The interaction of the enzyme with the non-allosteric substrate bromocriptine is not altered in F213W or F304W, whereas the mutant L211F/D214E exhibits decreased affinity and lowered amplitude of the spin shift with this substrate (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Interactions of CYP3A4 wild type (circles), and its F213W (triangles), F304W (squares), and L211F/D214E (diamonds) mutants with ANF (a), 1-PB (b) and bromocriptine (c) monitored by a substrate-induced spin shift. Solid lines show the results of fitting of the data sets with the Hill equation (panels a and b) or the equation for the equilibrium of binary association (equation (1), panel c). Conditions: 1-1.5 μM cytochrome P450 in 0.1 M Na-Hepes, pH 7.4, 25 °C. In the experiments with 1-PB (a) the buffer also contained 0.6% HPCD.

Table 1.

Position of spin equilibrium and the parameters of substrate binding monitored by substrate-induced spin shift for CYP3A4 wild type and its F213W ,F304W and L211F/D214E mutants.*

| Substrate | Parameter | CYP3A4 variant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | F213W | F304W | L211F/D214E | ||

| None | h0,%a | 10.9 ± 0.5 | 16.3 ± 1.7 | 24.2 ± 4.1 | 26.8 ± 1.0 |

| 1-PB |

S50, μM nH Δhmax,%b |

11.7 ± 2.4 1.67 ± 0.18 46.7 ± 4.9 |

12.6 ± 4.6 1.07 ± 0.16 57.0 ± 5.9 |

10.7 ± 2.0 1.07 ± 0.12 57.7 ± 5.6 |

12.1 ± 1.8 1.07 ± 0.17 39.4 ± 5.1 |

| ANF |

S50, μM nH Δhmax,% |

3.66 ± 0.70 2.04 ± 0.30 40.0 ± 2.5 |

3.50 ± 1.36 1.52 ± 0.30 33.5 ± 2.1 |

3.63 ± 1.46 2.10 ± 0.20 36.0 ± 5.2 |

3.67 ± 1.16 1.68 ± 0.16 27.9 ± 2.2 |

| Bromocriptine |

KD, μM Δhmax,% |

0.83 ± 0.11 49.0 ± 3.3 |

0.86 ± 0.27 30.2 ± 8.0 |

0.64 ± 0.12 41.0 ± 4.0 |

1.50 ± 0.37 23.6 ± 3.6 |

The values given in the table represent the averages of 3-7 individual measurements and the “±” values show the confidence interval calculated for p = 0.05.

The fraction of the high spin heme protein at 25 °C at no substrate added.

The amplitude of the substrate-induced spin shift, %.

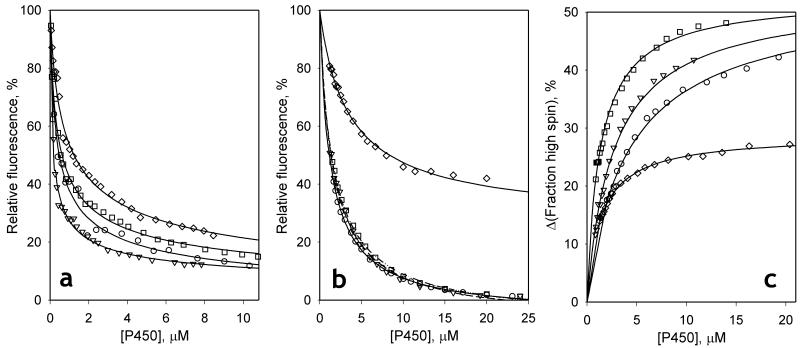

Resolution of individual substrate-binding events in the interactions of 1-PB with CYP3A4 and its mutants in “titration-by-dilution” experiments with substrate binding monitored by FRET

Our approach to studying the individual steps involved in the mechanism of cooperativity is based on examining the dissociation of the enzyme-substrate complex upon dilution of enzyme-substrate mixtures of various stoichiometry (Davydov et al., 2006; Fernando et al., 2006). In the present study, substrate binding was determined either by FRET from 1-PB to the heme of the enzyme, or by the substrate-induced spin shift monitored by absorbance spectroscopy.

As demonstrated earlier (Fernando et al., 2006), the formation of the complexes of CYP3A4 with 1-PB resulted in a considerable decrease in the intensity of fluorescence of the substrate due to FRET to the heme. Similar behavior is observed in our experiments with the F213W, F304W, and L211F/D214E mutants. The dependence of the normalized intensity of fluorescence on the concentration of equimolar mixtures of 1-PB with either wild type CYP3A4 or its mutants obeys the equation for the equilibrium of bimolecular association (1) (Fig 2a). Although the values of the dissociation constant (KD1) obtained from these experiments were in all cases considerably lower than the corresponding S50 values, the values of KD1 exhibit considerable variation among the mutants. The KD1 of L211F/D214E for 1-PB was notably higher than the value obtained with the wild type enzyme, whereas F213W exhibited a decreased KD1 value (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Interactions of 1-PB with CYP3A4 wild type (circles) and its F213W (triangles) and F304W (squares) and L211F/D214E (diamonds) mutants in dilution experiments. Changes in the normalized intensity of fluorescence upon dilution of a 1:1 mixture of 1-PB and enzyme are shown in panel (a). The results of a similar set of experiments performed at excess substrate are shown in panel (b). In the experiments with F304W and L211F/D214E the enzyme:substrate ratio was equal to 1:6, while the data sets shown for the wild type enzyme and F213W were obtained with a ratio of 1:4 and 1:5 respectively. Panel (c) illustrates the dilution experiments performed at 1:5 enzyme:substrate ratio with registration of absorbance. Solid lines represent the results of fitting of the data set to equation (1).

Table 2.

Parameters of the individual substrate binding transitions found in dilution experiments with detection of 1-PB binding to CYP3A4 and its mutants by FRET and substrate-induced spin shift.*

| CYP3A4 variant |

Titration-by-dilution with an equimolar enzyme-substrate mixture monitored by FRET |

Titration-by-dilution at excess substrate monitored by FRET |

Titration-by-dilution at excess substrate monitored by spin shift |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD1, μM | Efficiency of FRET, % |

KD2, μM | Efficiency of FRET, % |

KD2, μM | Δhmax, %a | |

| Wild Type | 0.25 ± 0.11 | 95.2 ± 5.7 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 108.0 ± 1.2 | 10.2 ± 1.2 | 49.7 ± 7.3 |

| F213W | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 80.8 ± 26.4 | 7.0 ± 0.05 | 109.0 ± 2.0 | 14.4 ± 1.5 | 40.0 ± 16 |

| F304W | 0.26 ± 0.08 | 99.6 ± 7.8 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 109.0 ± 1.6 | 11.4 ± 1.1 | 23.2 ± 14.0 |

| L211F/D214E | 0.82 ± 0.43 | 108.4 ± 12.9 | 16.4 ± 16.5 | 83.4 ± 16.4 | 7.3 ± 2.9 | 18.2 ± 7.1 |

The values given in the table represent the averages of 2-4 individual measurements and the “±” values show the confidence interval calculated for p = 0.05.

Maximal amplitude of the spin shift deduced from the fitting of the titration curves.

Results of FRET dilution studies performed at excess substrate (Fig 2b) do not exhibit any qualitative difference between the wild type and the mutants. In all four cases the titration curves obey equation 1 with values for the dissociation constant (KD2) about one order of magnitude higher than those found in 1:1 dilution experiments (Table 2). However, as with KD1, the KD2 observed with L211F/D214E was notably higher than the estimates obtained with either the wild type or the F213W and F304W mutants. It is also noteworthy that in all four cases the fitting of titration curves to equation 1 results in an apparent efficiency of FRET slightly exceeding 100% (Table 2). These anomalously high values may be caused by incomplete resolution of the two substrate binding events, as far as a decrease in the degree of saturation of the high-affinity binding site at low concentrations of the enzyme-substrate mixture may affect the apparent FRET amplitude.

“Titration-by-dilution” experiments at excess substrate with monitoring of the substrate-induced spin shift

The formation of the final, productive complex of CYP3A4 with 1-PB is evidenced by the spin-shift and may therefore be detected by absorbance spectroscopy in dilution experiments at excess substrate. Results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 2c. The data points shown in this figure represent the difference between the high-spin content at each concentration of the enzyme-substrate mixture and the value that would be observed at infinite dilution according to the extrapolation of the fitting curves. Similar to the curves obtained in FRET titrations at excess substrate, these data sets may be adequately approximated by equation (1) with the values of dissociation constant (KD2) over an order of magnitude higher that the values of KD1 found in 1:1 dilution experiments. In all cases except for the L211F/D214E mutant, the estimates of KD2 found here were approximately 2-times higher than the values deduced from FRET experiments. However, the mutant L211F/D214E represents the opposite case, with the FRET-based estimate being higher that the estimate found in spin-shift experiments (Table 2).

Analysis of the amplitudes of the substrate-induced spin shift observed in these experiments reveals an important difference between the wild type and the mutants. In the case of the wild type, the amplitude estimated from dilution experiments (50 ± 7%) is similar to the value observed in absorbance titrations (47 ± 5%). In contrast, the amplitudes obtained in dilution experiments with the mutants are lower than the corresponding values found in titration experiments (cf. Table 1 and Table 2). This difference is especially important in the case of L211F/D214E, where the amplitude found in dilution titration (18 ± 7%) is approximately 2-times lower than the value found in absorbance titrations (40 ± 3%). This finding may suggest that the requirement of the binding of the second substrate molecule for spin shift to occur in the ternary complex only, according to our initial sequential model of interactions (Fernando et al., 2006) is compromised in the mutants. In particular, an initial spin shift which may take place in the mutants upon formation of the 1:1 complex would not be detected in dilution curves measured at excess substrate, inasmuch as the high affinity binding site would be substrate-saturated throughout these experiments. In the following section we probe the hypothesis that explanation of altered cooperativity may be found if we allow for displacement of the spin equilibrium in both the ES and SES complexes, although not necessarily to the same extent.

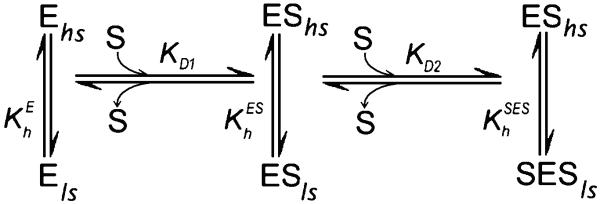

Analysis of the substrate-induced spin shift in the mutants with a two-step sequential model

According to the sequential model (Fig. 3) introduced in our earlier study (Fernando et al., 2006), the binding at one of the two substrate binding sites in the enzyme requires a prior substrate association at another, higher-affinity site. This property results in cooperativity in the formation of the final ternary complex (SES). It was also hypothesized that modulation of the spin equilibrium is observed only in the ternary complex, so that . To probe the applicability of this scheme to the interactions of F213W, F304W, and L211F/D214E with 1-PB we attempted to fit the absorbance titration curves with the relationship describing the formation of the ternary complexes SES. In the general case, when the concentration of the enzyme is comparable with the concentrations of the substrate and changes in free substrate concentration cannot be neglected, the two-step sequential mechanism (Fig. 3) may be described with the following relationships (Fernando et al., 2006):

| (2) |

Although the explicit analytical solution of this system is intricate, the concentrations [ES] and [SES] may be found from a numerical solution of (2), as previously described (Davydov et al., 2005; Fernando et al., 2006). In the case when the spin shift is observed only upon the formation of the complex SES, the spin state of the heme protein at each given concentration of substrate (Fhs) is determined as:

| (3) |

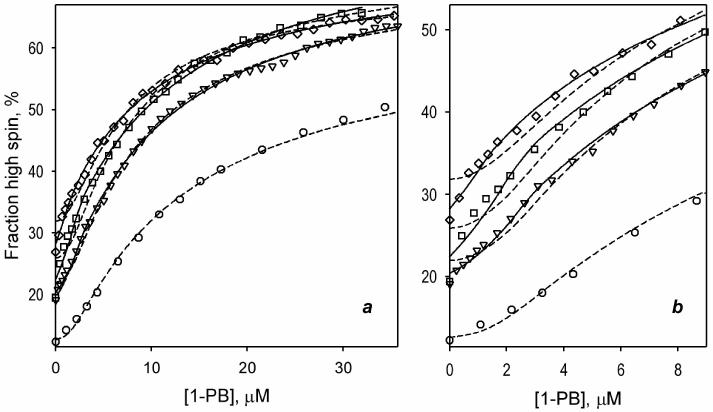

where h0 is the fraction high spin in the substrate-free enzyme, Δhmax is the maximal amplitude of the spin shift, [SES] is determined according to (2), and [E]0 is the total concentration of the heme protein. In our fitting of the titration curves to this equation with the non-linear least-square regression (see Data Processing in Materials and Methods) we optimized the values of h0, Δhmax and KD2, while the KD1 was fixed to the experimentally determined value of this constant (Table 2) (Davydov et al., 2005; Fernando et al., 2006). The results of this fitting are shown in Fig. 4 in dashed lines. Similar to the previous study (Fernando et al., 2006), the sequential model (Fig. 3) adequately describes the titration curves reflecting the interactions of 1-PB with wild type CYP3A4. The fitting shown in Fig. 4 (circles, dashed line) is characterized by the square correlation coefficient (ρ2) of 0.9984 and yields the estimates of KD2, h0 and Δhmax of 12.6 μM, 12.6%, and 51.1%, respectively. At the same time, the fitting of the data sets obtained with the three mutants reveal an important systematic deviation from the experimental results. As seen from the Fig 4b, these deviations are especially important at low concentrations of the ligand.

Fig. 3.

Sequential two-state binding mechanism of substrate binding with two substrate binding sites and linked spin equilibria.

Fig. 4.

Approximation of the results of the absorbance titration experiments of CYP3A4 mutants F213W (triangles) F304W (squares) and L211F/D214E (diamonds) with the sequential model of substrate binding (Fig. 3). The data points represent the same data sets as shown in Fig. 1b. Dashed lines show the results of approximation of the data sets with the initial sequential model, where the spin shift is observed in the ternary complex only. The solid lines represent the results of fitting to improved sequential model, where the substrate-induced displacement of the spin equilibrium in the complex ES is allowed. The fitting of the data set for the wild type enzyme with improved model is not shown, as it yields FES = 0 and results in the approximation identical to that given by the initial model (dashed line). Panel b shows the initial part of the same curves zoomed in.

Therefore, the initial model, where the spin shift takes place upon the formation of SES complex only, is insufficient to explain the altered cooperativity in the mutants. The attempts to use the parallel model, where the binding of the substrate is allowed to either of the two binding sites in the substrate-free enzyme (Fernando et al., 2006), the experimentally determined values of KD1 and KD2 were found incompatible with this mechanism (data not shown). Accordingly, we analyzed the behavior of the sequential model with the additional allowance for displacement of the spin equilibrium in both the ES and SES complexes. In this case the increase in the fraction of the high-spin enzyme observed in the titrations would reflect a combination of the concentrations of ES and SES:

| (4) |

Here and are the amplitudes of the spin shift (relative to the substrate-free state) observed upon the formation of the complexes ES and SES respectively, . The concentrations [ES] and [SES] are determined according to (2), and the parameter FES is equal to the ratio of the amplitude of the spin shift exerted by the complex ES to the total spin shift amplitude, :

This parameter signifies the fraction of the total signal that is caused by the displacement of the spin equilibrium in the binary complex. The case when FES=0 corresponds to the initial model, where the spin shift is observed in the ternary complex only. The situation when the full-amplitude spin shift takes place upon the formation of the complex ES and the binding of the second molecule has no further effect on the spin state corresponds to FES =0.5. The intermediate situation, when the binding of the first substrate molecule results in some partial spin shift, although the full amplitude requires the formation of the ternary complex, is observed when 0 ≤ FES ≤ 0.5. The case when FES>0.5 represent the situation where the formation of the ternary complex results in a backward (high-to-low) displacement of the spin equilibrium relative to that observed in the binary complex.

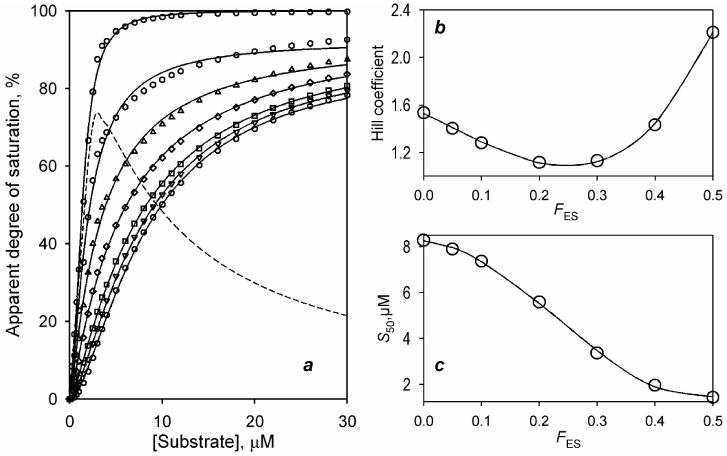

To probe how the change in the parameter FES may affect the experimentally determined values of the Hill coefficient and S50 we built a series of modeling curves for FES changing from 0 to 0.5. In these calculations we used a linear combination of the concentrations of ES and SES as determined by the expression (4) in (Fernando et al., 2006) and substituted KD1 and KD2 with the values of 0.25 μM and 7.5 μM respectively, which were chosen according to the estimates found for the wild type enzyme. The calculated data sets along with the results of their fitting are shown in Fig. 5a. Although the increase in FES results in a significant alteration of the shape of the curves, the quality of their fitting to Hill equation remains appropriate (ρ2 of 0.997 – 0.9998). As illustrated in Fig. 5b, the initial increase in FES results in a decrease in the Hill coefficient (nH) from 1.54 to 1.097 and the minimal value of nH is observed at FES =0.25. Further increase in FES boosts nH up to value of 2.21, which is observed at FES =0.5.

Fig. 5.

The effect of the parameter FES on the behavior of the improved sequential model and the effective values of nH and S50 determined from the fitting of the simulated titration curves to the Hill equation. Data sets shown in the panel a were calculated for KD1=0.25 μM, KD2=7.5 μM, the enzyme concentration of 1.5 μM and FES equal to 0 (circles), 0.05 (inverted triangles), 0.1 (squares), 0.2 (diamonds), 0.3 (triangles), 0.4 (hexagons) and 0.5 (circles). The dashed line shows the dependence calculated for FES =1 (i.e., reflecting the changes in the concentration of the binary complex only). Solid lines show the fitting of the calculated data sets to the Hill equation. The effect of FES on the values of nH and S50 found from this fitting is illustrated on the panels b and c. The solid lines shown on these panels represent the approximation of the dependencies with a third-order polynomial. These approximations have no interpretative meaning and are shown only to illustrate the general trend.

Fitting of the absorbance titration curves obtained with mutants with the improved sequential model is shown on Fig. 4 in solid lines. Here again we fixed the value of KD1 at the experimentally determined estimate and allowed the program to optimize the values of KD2, h0, Δhmax, and FES. The changes in the value of KD2 in the optimization procedure never exceeded 30% of the initial estimate, which was set to the mean of the values found by two different experimental approaches (see Table 2). As seen from Fig 4, the modification of the model increased the quality of fitting dramatically. No systematic deviations were observed in this case (ρ2 >0.996). The values of the parameter FES obtained for F213W, F304W, and L211F/D214E comprise 7.9 ±1.0%, 15.1 ± 0.8% and 21.0 ± 5.7% respectively. At the same time, the fitting of the titration curve obtained with the wild type enzyme results in FES =0, confirming that the substrate-induced spin shift in the wild type is observed in the ternary complex only.

Discussion

Our studies of the binding of three substrates to the CYP3A4 mutants F304W, F213W, and L211F/D214E revealed no considerable effect on the spin shift caused by bromocriptine, a non-allosteric substrate, or any substantial decrease in the cooperativity with ANF, a heterotropic activator. Strikingly, although homotropic cooperativity with 1-PB is abolished (Table 1), according to the results of our dilution experiments, none of the substitutions eliminates either binding site for 1-PB (Table 2). Our analysis of these results in terms of the two-step sequential model (Fig. 3) suggests that the probed mutations do not affect formation of the enzyme-substrate complexes but rather alter how the individual substrate binding events affect the spin equilibrium. This finding contradicts the initial premise that one binding site is lacking in the mutants. Our results are consistent with a model where the substrate-induced spin shift occurs in the ternary complex for the wild type enzyme, but the mutants reveal some partial spin shift upon the interactions with the first substrate molecule. We also demonstrate that variation in the fraction of the total signal that is caused by the displacement of the spin equilibrium in the binary complex (FES) can account for variation of the experimentally determined values of the Hill coefficient from ~1.1 to ~2.2 without any modification of the number of binding sites or the sequence of binding events. This observation indicates that the two-step sequential model complemented with the allowance for the substrate-induced spin shift in both ES and SES complexes may explain other cases of homotropic cooperativity in CYP3A4.

The discussed mechanisms may also explain the loss of cooperativity in steroid hydroxylation observed in the mutants (Domanski et al., 1998; Domanski et al., 2001). Although the interrelationship between the substrate-induced spin shift and the efficiency of P450-catalysis is not straightforward, a conversion from the hexa-coordinated low-spin to the penta-coordinated high-spin state has an important impact on the catalytic efficiency and coupling of the P450 (see (Hlavica, 2007) for review). This link is demonstrated clearly, for example, in studies with CYP2B4 and a series of benzphetamine analogs (Blanck et al., 1983; Schwarze et al., 1985; Blanck et al., 1991). Those results reveal a strict correlation between the rate of substrate N-demethylation and its coupling to NADPH oxidation with the amplitude of the substrate-induced spin shift. Furthermore, the low-to-high spin transition is known to increase the rate of electron transfer to cytochromes P450 (Tamburini et al., 1984; Backes et al., 1985; Backes and Eyer, 1989) due to a considerable decrease in the reorganization energy associated with the reduction process (Honeychurch et al., 1999; Denisov et al., 2005) along with a positive displacement of the P450 redox potential (Fisher and Sligar, 1985). This has been demonstrated with CYP3A4 (Das et al., 2007) in particular. Therefore, mechanisms of the cooperativity in the substrate-induced spin shift and substrate hydroxylation are tightly interrelated, so far as the spin state of the enzyme in the complex ES is commensurate to the rate of hydroxylation observed in this complex. Our analysis also suggests that, contrary to common expectations (see (Denisov et al., 2009) for discussion), cases of P450 interactions with substrates where the Hill coefficient exceeds 2 (Domanski et al., 2001; Davydov et al., 2002; Baas et al., 2004; Jushchyshyn et al., 2005; Davydov et al., 2010) do not necessarily suggest an involvement of more than 2 substrate binding sites in the mechanism.

There might be at least two fundamentally different mechanistic bases for the variation in the effect of the first substrate binding event on the amplitude of the spin shift. If, following the long-established hypothesis (Domanski et al., 1998; Korzekwa et al., 1998), we assume that the two binding sites are both located in close proximity of the heme and the cooperativity mechanism does not involve any effector-induced conformational changes, the variation may simply reflect some (possibly quite subtle) changes in the geometry of the active site. These changes may augment the ability of the first bound substrate molecule to displace the water that serves as a heme ligand in the low-spin state.

A completely different mechanism may take place if the cooperativity mechanism involves a remote binding site, where interaction with the substrate triggers a conformational transition (see (Davydov et al., 2008) for review). In this case, although the high affinity binding event may reflect the binding of the substrate in close proximity to the heme, the second (remote) binding is required for the wild type enzyme to adapt an active conformation, where the substrate-induced spin shift (and the catalysis) takes place. Accordingly, the probed mutations may compromise this modulatory mechanism by partial displacement of the conformational equilibrium towards the “activated” conformer even without effector bound at the second site.

Discrimination between the two possibilities requires use of advanced methods for detection of enzyme-substrate interactions, which would allow us to locate the position of the respective substrate binding sites in CYP3A4. In particular, these studies may utilize site-directed modification of the enzyme with a fluorescent probe in order to establish a FRET donor/acceptor pair with an appropriate substrate fluorophore.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interests

This research was supported by grant GM054995 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- Baas BJ, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Homotropic cooperativity of monomeric cytochrome P450 3A4 in a nanoscale native bilayer environment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;430:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backes WL, Eyer CS. Cytochrome P-450 LM2 reduction. Substrate effects on the rate of reductase-LM2 association. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:6252–6259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backes WL, Tamburini PP, Jansson I, Gibson GG, Sligar SG, Schenkman JB. Kinetics of cytochrome P-450 reduction: evidence for faster reduction of the high-spin ferric state. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5130–5136. doi: 10.1021/bi00340a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck J, Ristau O, Zhukov AA, Archakov AI, Rein H, Ruckpaul K. Cytochrome P-450 spin state and leakiness of the monooxygenase pathway. Xenobiotica. 1991;21:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00498259109039456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck JR,H, Sommer M, Ristau O, Smettan G, Ruckpaul K. Correlations between spin equilibrium shift, reduction rate, and N-demethylation activity in liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 and a series of benzphetamine analogs as substrates. Biochem. Pharm. 1983;32:1683–1688. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupp-Vickery J, Anderson R, Hatziris Z. Crystal structures of ligand complexes of P450eryF exhibiting homotropic cooperativity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3050–3055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050406897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski MJ, Schrag ML, Wienkers L, Atkins WM. Pyrene-pyrene complexes at the active site of cytochrome P450 3A4: Evidence for a multiple substrate binding site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11866–11867. doi: 10.1021/ja027552x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Redox potential control by drug binding to cytochrome p450 3A4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13778–13779. doi: 10.1021/ja074864x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Botchkareva AE, Davydova NY, Halpert JR. Resolution of two substrate-binding sites in an engineered cytochrome P450eryF bearing a fluorescent probe. Biophys. J. 2005;89:418–432. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Davydova NY, Halpert JR. Allosteric transitions in cytochrome P450eryF explored with pressure-perturbation spectroscopy, lifetime FRET, and a novel fluorescent substrate, Fluorol-7GA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11348–11359. doi: 10.1021/bi8011803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Deprez E, Hui Bon Hoa G, Knyushko TV, Kuznetsova GP, Koen YM, Archakov AI. High-pressure-induced transitions in microsomal cytochrome P450 2B4 in solution - evidence for conformational inhomogeneity in the oligomers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995;320:330–344. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Femando H, Halpert JR. Variable path length and counter-flow continuous variation methods for the study of the formation of high-affinity complexes by absorbance spectroscopy. An application to the studies of substrate binding in cytochrome P450. Biophys. Chem. 2006;123:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Halpert JR. Allosteric P450 mechanisms: multiple binding sites, multiple conformers or both? Expert Opin. Drug Met. 2008;4:1523–1535. doi: 10.1517/17425250802500028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Kumar S, Halpert JR. Allosteric mechanisms in P450eryF probed with 1-pyrenebutanol, a novel fluorescent substrate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;294:806–812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00565-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DR, Sineva EV, Sistla S, Davydova NY, Frank DJ, Sligar SG, Halpert JR. Electron transfer in the complex of membrane-bound human cytochrome P450 3A4 with the flavin domain of P450BM-3: the effect of oligomerization of the heme protein and intermittent modulation of the spin equilibrium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:378–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denisov IG, Frank DJ, Sligar SG. Cooperative properties of cytochromes P450. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;124:151–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denisov IG, Macris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Structure and chemistry of cytochrome P450. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2253–2277. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanski TL, He YA, Harlow GR, Halpert JR. Dual role of human cytochrome P450 3A4 residue Phe-304 in substrate specificity and cooperativity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanski TL, He YA, Khan KK, Roussel F, Wang Q, Halpert JR. Phenylalanine and tryptophan scanning mutagenesis of CYP3A4 substrate recognition site residues and effect on substrate oxidation and cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10150–10160. doi: 10.1021/bi010758a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanski TL, Liu J, Harlow GR, Halpert JR. Analysis of four residues within substrate recognition site 4 of human cytochrome P450 3A4: role in steroid hydroxylase activity and alpha- naphthoflavone stimulation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;350:223–232. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekroos M, Sjogren T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13682–13687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando H, Davydov DR, Chin CC, Halpert JR. Role of subunit interactions in P450 oligomers in the loss of homotropic cooperativity in the cytochrome P450 3A4 mutant L211F/D214E/F304W. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;460:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando H, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Resolution of multiple substrate binding sites in cytochrome P450 3A4: The stoichiometry of the enzyme-substrate complexes probed by FRET and Job’s titration. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4199–4209. doi: 10.1021/bi052491b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MT, Sligar SG. Control of heme protein redox potential and reduction rate-Linear free energy relation between potential and ferric spin state equilibrium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:5018–5019. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow GR, Halpert JR. Analysis of human cytochrome P450 3A4 cooperativity: construction and characterization of a site-directed mutant that displays hyperbolic steroid hydroxylation kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6636–6641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavica P. Control by substrate of the cytochrome p450-dependent redox machinery: Mechanistic insights. Curr. Drug Metab. 2007;8:594–611. doi: 10.2174/138920007781368881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeychurch MJH, Hill AO, Wong LL. The thermodynamics and kinetics of electron transfer in the cytochrome P450(cam) enzyme system. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:351–353. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosea NA, Miller GP, Guengerich FP. Elucidation of distinct ligand binding sites for cytochrome P450 3A4. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5929–5939. doi: 10.1021/bi992765t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jushchyshyn MI, Hutzler JM, Schrag ML, Wienkers LC. Catalytic turnover of pyrene by CYP3A4: Evidence that cytochrome b(5) directly induces positive cooperativity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;438:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzekwa KR, Krishnamachary N, Shou M, Ogai A, Parise RA, Rettie AE, Gonzalez FJ, Tracy TS. Evaluation of atypical cytochrome P450 kinetics with two-substrate models: evidence that multiple substrates can simultaneously bind to cytochrome P450 active sites. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4137–4147. doi: 10.1021/bi9715627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud JP, Davydov DR, Heirwegh KPM, Mansuy D, Hui Bon Hoa G. Thermodynamic studies of substrate binding and spin transitions in human cytochrome P-450 expressed in yeast microsomes. Biochem J. 1996;319:675–681. doi: 10.1042/bj3190675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze W, Blanck J, Ristau O, Janig GR, Pommerening K, Rein H, Ruckpaul K. Spin state control of cytochrome P-450 reduction and catalytic activity in a reconstituted P-450 LM2 system as induced by a series of benzphetamine analogs. Chem Biol Interact. 1985;54:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(85)80158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segel IH. Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-State Enzyme Systems. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Tamburini PP, Gibson GG, Backes WL, Sligar SG, Schenkman JB. Reduction kinetics of purified rat liver cytochrome P-450. Evidence for a sequential reaction mechanism dependent on the hemoprotein spin state. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4526–4533. doi: 10.1021/bi00315a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsalkova TN, Davydova NY, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Mechanism of interactions of alpha-naphthoflavone with cytochrome p450 3A4 explored with an engineered enzyme bearing a fluorescent probe. Biochemistry. 2007;46:106–119. doi: 10.1021/bi061944p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PA, Cosme J, Vinkovic DM, Ward A, Angove HC, Day PJ, Vonrhein C, Tickle IJ, Jhoti H. Crystal structures of human cytochrome P450 3A4 bound to metyrapone and progesterone. Science. 2004;305:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]