Abstract

Until recently, patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) had limited therapeutic options once they became refractory to docetaxel chemotherapy, and no treatments improved survival. This changed in June 2010 when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved cabazitaxel as a new option for patients with CRPC whose disease progresses during or after docetaxel treatment. For most of these patients, cabazitaxel will now replace mitoxantrone (a drug that was FDA-approved because of its palliative effects) as the treatment of choice for docetaxel-refractory disease. The approval of cabazitaxel was based primarily on the TROPIC trial, a large (n = 755) randomized Phase III study showing an overall median survival benefit of 2.4 months for men with docetaxel-pretreated metastatic CRPC receiving cabazitaxel (with prednisone) compared to mitoxantrone (with prednisone). Cabazitaxel is a novel tubulin-binding taxane that differs from docetaxel because of its poor affinity for P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an ATP-dependent drug efflux pump. Cancer cells that express P-gp become resistant to taxanes, and the effectiveness of docetaxel can be limited by its high substrate affinity for P-gp. Preclinical and early clinical studies show that cabazitaxel retains activity in docetaxel-resistant tumors, and this was confirmed by the TROPIC study. Common adverse events with cabazitaxel include neutropenia (including febrile neutropenia) and diarrhea, while neuropathy was rarely observed. Thus, the combination of cabazitaxel and prednisone is an important new treatment option for men with docetaxel-refractory metastatic CRPC, but this agent should be administered cautiously and with appropriate monitoring (especially in men at high risk of neutropenic complications).

Keywords: cabazitaxel, castration-resistant prostate cancer, clinical trial, docetaxel resistance, drug development

Introduction

More than 217,000 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer and 32,000 will die of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States (US) in 2010,1 making it the second leading cause of cancer death in American men, behind lung cancer. Most patients whose disease is diagnosed at the locoregional level have an excellent prognosis, enhanced by radical prostatectomy and/or radiation therapy. About one-fifth of patients undergo watchful waiting alone. A significant fraction (20%–40%) of patients who undergo primary therapy experience biochemical relapse (prostate-specific antigen [PSA] >0.2 ng/mL), and 30%–70% of those with biochemical recurrence develop metastatic disease within 10 years after local therapy.2–5 For most patients with metastatic prostate cancer, androgen-deprivation therapy, usually with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist, improves symptoms but tumors invariably become castration-resistant and patients develop progressive disease. Until the mid 1990s, with no known life-prolonging options, castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients with progressive disease were generally treated with palliative approaches. Chemotherapy was not well tolerated by CRPC patients, who were often elderly men with limited bone marrow reserve and concurrent medical conditions.

In 1996, Tannock et al showed that mitoxantrone (with prednisone) improved quality of life and bone pain, and reduced serum PSA levels in men with CRPC,6 and this approach became the initial standard of care for such patients. Then in 2004, the TAX327 trial compared weekly and 3-weekly docetaxel (and prednisone) against mitoxantrone (and prednisone) and showed a significant survival benefit for the 3-weekly docetaxel arm.7 That same year, the Southwest Oncology Group reported significantly extended progression-free and overall survival for CRPC patients treated with docetaxel and estramustine compared to mitoxantrone and prednisone.8 On the basis of these results, docetaxel replaced mitoxantrone as the first-line standard of care for CRPC patients. Until last year, however, physicians had no life-prolonging second-line options after docetaxel failure. Notably, on June 17, 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved cabazitaxel “for the treatment of patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer previously treated with a docetaxel-containing regimen”.9 This review summarizes the preclinical and clinical data that led to the FDA-approval of this agent, and touches upon the mechanism of action and rationale for the use of this drug in docetaxel-refractory disease. Our overall intention with this review is to raise awareness of a newly available second-line treatment for metastatic CRPC that provides an overall survival benefit.

Mechanism of action and biological rationale for cabazitaxel

Docetaxel is a widely-used second-generation taxane compound. The first taxane was paclitaxel, a drug isolated from yew tree bark in the 1960s and first approved by the FDA in 1992 for treatment of refractory ovarian cancer.10 Docetaxel is a semisynthetic and more active derivative of paclitaxel. Paclitaxel and docetaxel are both antimitotic cancer drugs that bind to intracellular microtubules, suppressing microtubule dynamics. The taxanes promote or inhibit assembly of tubulin into microtubules, impairing the natural dynamics of microtubules and leading to mitotic block and apoptosis.10

In preclinical studies using advanced human tumors in mouse xenograft models, cabazitaxel was shown to be active in both docetaxel-sensitive tumors and those that did not respond to chemotherapy including docetaxel.11 The effectiveness of paclitaxel and docetaxel is limited by the high substrate affinity of both agents for P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent drug efflux pump that decreases the intracellular concentrations of these drugs.12 It has been shown that cancer cells that express P-gp become resistant to taxanes.10,13 This resistance is conferred by overexpression of the multidrug resistance (MDR1) gene that encodes P-gp, a member of the ATP-binding cassette transporter family of proteins.14

Cabazitaxel (previously also known as XRP6258, TXD258, and RPR116258A) (Jevtana™; Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France) is a semisynthetic taxane that uses a precursor molecule extracted from yew tree needles. It was selected for clinical development due to its poor affinity for P-gp and because it was superior to paclitaxel and docetaxel in penetration of the blood-brain barrier in preclinical models.15 Cabazitaxel’s poor affinity for P-gp may or may not be the principal mechanism of action that enables its efficacy in the clinic. Multiple previous clinical trials have shown MDR1 inhibitors to lack clinical efficacy.16

Chemistry and pharmacology

Chemical structure of cabazitaxel

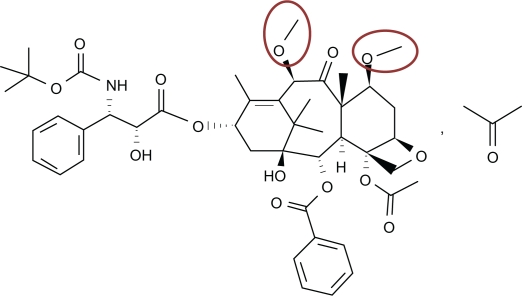

Cabazitaxel was engineered as a dimethyloxy derivative of docetaxel (Figure 1) that offers two advantages over its predecessor. The primary benefit provided by the extra methyl groups is elimination of the P-gp affinity characteristic of docetaxel, enabling cabazitaxel to be effective against docetaxel-refractory prostate cancer. The extra methyl groups also provide cabazitaxel with an uncommon capacity among chemotherapy agents; the ability to cross the blood–brain barrier, the clinical effects of which remain to be investigated.17

Figure 1.

Structure of cabazitaxel,11 a semi-synthetic taxane anticancer drug. (2α, 5β, 7β, 10β, 13α)-4-acetoxy-13-({(2R,3S)-3 [(tertbutoxycarbonyl) amino]-2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanoyl}oxy)-1-hydroxy-7,10-dimethoxy-9-oxo-5,20-epoxytax11-en-2-yl benzoat•propan-2-one(1:1); C45H57NO14•C3H6O; molecular mass = 894.01 units. The red circles highlight the methoxy side chains that represent the primary substitution for the hydroxyl groups found in docetaxel.

Pharmacokinetics of cabazitaxel

Pharmacokinetic evaluations were performed using blood sampling from 170 patients. Following a 1-hour intravenous infusion of cabazitaxel (25 mg/m2), approximately 80% of the dose was eliminated within 2 weeks,15 primarily excreted by the enterohepatic circulation. The pharmacokinetic behavior in plasma was best characterized by a triphasic model with a rapid initial-phase half-life averaging 4 minutes, followed by an intermediate-phase half-life of 2 hours, and a prolonged terminal-phase half-life averaging 95 hours. Protein binding of cabazitaxel was primarily to human serum albumin (82%) and lipoproteins;15 cabazitaxel is equally distributed between plasma and blood. Cabazitaxel is metabolized in the liver primarily by the CYP3A4/5 isoenzymes and to a lesser degree by CYP2C8. Although formal drug–drug interaction studies have not been completed, agents that induce or inhibit the activity of the CYP450 isoenzymes should be avoided because of potential interaction with cabazitaxel.18 The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of cabazitaxel in patients with solid tumors was 535 μg/L and was reached at the conclusion of a one-hour infusion of 25 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.15 Average area-under-the-curve (AUC) was 1,038 ± 299 μg-h/L, and the relationship between cabazitaxel dose and AUC0–48h was proportional, as was the relationship between dose and Cmax.15

Clinical development

Phase I

In a Phase I study of cabazitaxel in 25 patients with advanced solid tumors, Mita et al administered intravenous doses of cabazitaxel at 10 mg/m2 (3 patients, 10 cycles), 15 mg/m2 (6 patients, 25 cycles), 20 mg/m2 (9 patients, 48 cycles), and 25 mg/m2 (7 patients, 19 cycles).15 The principal dose-limiting toxicity was neutropenia. One patient experienced prolonged grade 4 neutropenia, and a second patient experienced febrile neutropenia, both at the 25 mg/m2 dose. Other toxicities included generally mild-to-moderate nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, neurotoxicity, and fatigue. Diarrhea was observed in 14 patients (56%) during 28% of the courses of cabazitaxel; only one patient experienced grade 3 diarrhea.15 No grade 3 or 4 neurotoxicities were observed, but grade 1 neurosensory symptoms were common and manifested as acral paresthesia and diminished deep tendon reflexes as well as impaired vibratory sensation. No cumulative neurotoxicity was apparent in the nine patients receiving more than three courses at 20 or 25 mg/m2. Two patients experienced flushing, dizziness, and chest tightness (grade 1 hypersensitivity reactions); however in the setting of pre-medication this did not reoccur. Two patients treated at 25 mg/m2 experienced alopecia (grade 1/2).15

Anticancer activity was seen in two patients, both with metastatic prostate cancer.15 An 80-year-old man who received the 15 mg/m2 dose for six courses had a PSA decline from 62 to 21 ng/mL, experienced reduced disease-related bone pain, and demonstrated a reduction in a target lesion on computed tomography scan. He had previously undergone surgical castration, as well as treatment with bicalutamide, diethyl-stilbesterol, and mitoxantrone/prednisone. A 50-year-old man with castration-resistant and docetaxel-refractory metastatic prostate cancer showed a confirmed partial response in measurable disease lesions and a PSA reduction from 415 to 44 ng/mL at the 25 mg/m2 dose level, but experienced progressive disease after eight courses of chemotherapy. A partial response was also seen in one bladder cancer patient and minor responses were seen in two other patients, one of whom also had prostate cancer. Twelve patients (48%) had stable disease for greater than 4 months.15

Phase II

No Phase II study of cabazitaxel in patients with advanced prostate cancer was ever conducted, but a Phase II evaluation in breast cancer patients was central to the dosing selected for the eventual Phase III trial. Pivot et al conducted a Phase II study in 71 patients (61 evaluable) with metastatic breast cancer who were given intravenous cabazitaxel 20 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Patients received between 1 and 25 cycles of cabazitaxel, with a median of four cycles. After the first cycle, 20 patients who had experienced no adverse events (>grade 3 toxicities) had their dose increased to 25 mg/m2.19

After a median follow-up of 20 months, the median overall survival was 12.3 months and median time to progression was 2.7 months. Objective response rate was 14%, with eight partial and two complete responses seen. Eighteen patients (30%) experienced stable disease for at least 3 months. Seventy-three percent of patients experienced neutropenia, 55% experienced leucopenia, 35% fatigue, 32% nausea, 30% diarrhea, 18% vomiting, 17% sensory neuropathy, and 6% experienced hypersensitivity reactions. Two patients died within 30 days of their last on-study treatment. One death was due to shock with respiratory failure and determined to be related to the study drug. The cause of the other patient’s death was unknown.19

Phase III

The safety and efficacy of cabazitaxel in men with metastatic prostate cancer was evaluated in a pivotal randomized, multicenter, Phase III trial, TROPIC (treatment of hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer previously treated with a docetaxel-containing regimen), that enrolled patients from January 2007 to October 2008.20 This study involved 146 centers in 26 nations, and recruited 755 men with metastatic CRPC who had progressed during (30% of patients) or after (70% of patients) receiving docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Eligible patients were at least 18 years of age with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2. Patients were required to have either rising PSA or measurable disease as documented by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST),21 and had to be receiving LHRH agonist therapy or to have undergone surgical orchiectomy. Patients were allowed to continue bisphosphonates if the dose had remained stable for over 3 months. Median age of participants was 68 years (cabazitaxel) and 67 years (mitoxantrone), and 18.5% of patients were ≥75 years of age. Sixteen percent were non-Caucasian in both arms. Patients were stratified based on the presence/absence of measurable disease and on ECOG performance status, and then randomized equally into two groups: 378 patients received cabazitaxel (25 mg/m2), and 377 received mitoxantrone (12 mg/m2). The chemotherapy agents were administered intravenously every 3 weeks for a maximum of 10 cycles. All patients concurrently received 5 mg of oral prednisone twice daily.20

The trial’s primary endpoint was overall survival, and the main secondary endpoint was composite progression-free survival (defined as the time from randomization to the first date of PSA progression, radiographic tumor progression, pain progression, or death). Other secondary endpoints included PSA response rate (≥50% reduction); PSA progression (increase by ≥25% over nadir); objective tumor response (for patients with measurable disease, based on RECIST); pain response (reduction of ≥two points from baseline pain level using the Present Pain Intensity scale); and time to radiographic progression. Impressively, median overall survival for the cabazitaxel arm was 15.1 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 14.1–16.3 months) compared to 12.7 months (95% CI: 11.6–13.7 months) in the mitoxantrone arm (P < 0.0001). Risk of all-cause mortality was reduced by 30% for men receiving cabazitaxel compared to those receiving mitoxantrone (hazard ratio 0.70, 95% CI: 0.59–0.83).20 Secondary analyses also showed significant improvements in time to tumor progression and time to PSA progression (summarized in Table 1). Overall pain reduction was similar between the two groups, with no significant differences found. However, since mitoxantrone is often used because of its favorable effects on pain reduction, these results suggest that cabazitaxel will offer patients similar palliative quality of life results.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary endpoints in the TROPIC trial: response to treatment and disease progression

| Cabazitaxel | Mitoxantrone | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | |||

| Overall survival (months) | 15.1 (95% CI: 14.1–16.3) | 12.7 (95% CI: 11.6–13.7) | <0.0001a |

| Secondary endpoints | |||

| PFS (months)b | 2.8 (95% CI: 2.4–3.0) | 1.4 (95% CI: 1.4–1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor response rate | 14.4% (95% CI: 9.6–19.3) | 4.4% (95% CI: 1.6–7.2) | 0.0005 |

| PSA response rate | 39.2% (95% CI: 33.9–44.5) | 17.8% (95% CI: 13.7–22.0) | 0.0002 |

| Pain response rate | 9.2% (95% CI: 4.9–13.5) | 7.7% (95% CI: 3.7–11.8) | 0.63 |

Notes:

Corresponds to a 30% relative reduction in risk of death (hazard ratio 0.70, 95% CI: 0.59–0.83, P < 0.0001);

Progression-free survival (PFS) is a composite endpoint defined as: the time between randomization and the first date of progression as measured by prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression, tumor progression, pain progression, or death.

The median number of treatment cycles delivered was six (95% CI: 3–10) for the cabazitaxel group and four (95% CI: 2–7) for the mitoxantrone group. Disease progression was the primary reason for treatment discontinuation in both groups. Treatment delays were reported in 28% of the cabazitaxel-treated patients and 15% of the mitoxantrone-treated patients, and dose reductions were reported in 12% and 4% of patients, respectively. The most common toxicity in both treatment arms was neutropenia (82% of men in the cabazitaxel group and 58% in the mitoxantrone group experienced ≥grade 3 toxicity). Febrile neutropenia was observed in 8% and 1% of men, respectively. Given the high rates of neutropenia, prophylactic granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor was allowed after the first chemotherapy cycle, according to physician discretion. Other adverse events are summarized in Table 2. The high rates of neutropenia and other adverse events may reflect a patient population with poor-prognosis disease (50% of men having measurable disease, 25% having visceral metastases, and all having undergone previous chemotherapy treatment). Peripheral neuropathy (all grades) was reported in 14% of patients in the cabazitaxel group and 3% of the patients in the mitoxantrone group. However, only 1% of the patients in each group experienced grade 3 peripheral neuropathy.20

Table 2.

Most frequent adverse events observed in the TROPIC study

| Toxicity |

Cabazitaxel (n = 371) |

Mitoxantrone (n = 371) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade ≥ 3 (%) | All grades (%) | Grade ≥ 3 (%) | All grades (%) | |

| Neutropenia | 82% | 94% | 58% | 88% |

| Diarrhea | 6% | 47% | <1% | 11% |

| Fatigue | 5% | 37% | 3% | 27% |

| Back pain | 4% | 16% | 3% | 12% |

| Nausea | 2% | 34% | <1% | 23% |

| Vomiting | 2% | 23% | 0% | 10% |

| Hematuria | 2% | 17% | 1% | 4% |

| Abdominal pain | 2% | 12% | 0% | 4% |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1% | 14% | 1% | 3% |

During the conduct of the TROPIC study, 74% of men on the mitoxantrone group and 61% on the cabazitaxel group died. In the mitoxantrone arm, three patients (1%) died due to adverse events: neutropenia/sepsis (one patient), dyspnea (one patient), and motor vehicle accident (one patient). In the cabazitaxel arm, 18 patients (5%) died from adverse effects: neutropenia/sepsis (seven patients), cardiac events (five patients), renal failure (three patients), dehydration (one patient), cerebral hemorrhage (one patient), and unknown cause (one patient).20

Table 3 collates and contrasts toxicity data from the TROPIC trial and the prior TAX327 study,7 which compared mitoxantrone/prednisone against docetaxel/prednisone as first-line therapy for metastatic CRPC. The table shows that the side effect profile of cabazitaxel may not be as favorable as that of mitoxantrone. The table also offers data on the toxicity of docetaxel. Given the caveats associated with cross-trial comparisons, direct comparison of cabazitaxel and docetaxel toxicity must await a future head-to-head study, but the data in Table 3 support a preliminary claim that cabazitaxel may be more problematic than docetaxel with respect to anemia and neutropenia.

Table 3.

Selected grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities in the TAX327 and TROPIC trials

| Toxicity |

Docetaxel |

Cabazitaxel |

Mitoxantrone |

Mitoxantrone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAX327 (n = 332) | TROPIC (n = 371) | TAX 327 (n = 335) | TROPIC (n = 371) | |

| Anemia | 5% | 10% | 2% | 5% |

| Neutropenia | 32% | 82% | 22% | 58% |

| Febrile neutropenia | 2.7% | 7.5% | 1.8% | 1.3% |

| Septic death | 0% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0% |

Critical appraisal

The five cardiac-related deaths (one from ventricular fibrillation, one from sudden cardiac death, and three from cardiac arrest)22 combined with high incidence of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia bring into sharp focus the question of dose reduction strategies and personalization of cabazitaxel dosing for each patient. Multiple researchers recommended that the cabazitaxel dose level be lowered to 20 mg/m2.20,23,24 Their concerns with the high dose are supported both by the 20 mg/m2 recommended dose from the Phase I study of cabazitaxel15 as well as by the lower cardiac risk population of younger women with metastatic breast cancer recruited in the only Phase II study on the basis of which the Phase III dose was chosen.19 Based on our current data, the FDA label recommends the use of growth factor support as the primary prophylaxis in patients who are clinically considered at high risk for myelosuppression.11,25

An equally vexing question is whether and when to begin cabazitaxel treatment. Despite the FDA approval of cabazitaxel, some authors argue that further studies are needed before physicians routinely prescribe this expensive and toxic new drug. It has been pointed out that the inclusion criteria chosen by the TROPIC investigators biased the population toward healthier patients who received a lower cumulative dose of docetaxel thereby causing a meaningful enrichment of taxoid-responsive patients and favoring cabazitaxel over mitoxantrone.26

Finally, the approval of cabazitaxel by the FDA in June 2010 was contingent upon several additional investigations that the manufacturer was required to conduct in the postmarketing setting.9 These requirements are summarized below. Some of these studies are ongoing while others are currently in the planning phases.

To address the concerns of toxicities seen in patients receiving 25 mg/m2 of cabazitaxel, and to determine how cabazitaxel compares to docetaxel as a first-line treatment, a Phase III randomized controlled trial in patients with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer is required that compares a) 75 mg/m2 of docetaxel, b) 25 mg/m2 of cabazitaxel, and c) 20 mg/m2 of cabazitaxel. This study should be powered to detect a 25% difference in overall survival, and should be designed to drop one of the cabazitaxel arms based on interim analysis of overall survival and safety.

To address the concerns of toxicities seen in patients receiving 25 mg/m2 of cabazitaxel, a Phase III randomized controlled trial in patients with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer previously treated with docetaxel is required, comparing a) 20 mg/m2 of cabazitaxel and b) 25 mg/m2 of cabazitaxel, powered to preserve 50% of the treatment effect of cabazitaxel 25 mg/m2.

A trial examining the effect of cabazitaxel on corrected QT (QTc) interval prolongation is required.

A trial to determine the pharmacokinetics and safety of cabazitaxel in patients with hepatic impairment is required. Two drug interaction trials are required to evaluate the effect of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (eg, ketoconazole) and strong CYP3A inducers (eg, rifampin) on the pharmacokinetics of cabazitaxel.

Current treatment options, new agents, and future directions

Cabazitaxel is one of a series of drugs currently being evaluated by the FDA and is not the only treatment to be approved for CRPC in 2010. Sipuleucel-T (Provenge, Dendreon Corporation, Seattle, WA), the first therapeutic immunotherapy available for any cancer, was approved by the FDA on April 29, 2010 for men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic metastatic CRPC, on the basis of improved median survival observed in a pivotal placebo-controlled Phase III trial (overall survival 25.8 months versus 21.7 months for placebo) and an increase in 3-year survival (31.7% versus 23.0%).27 Thus, sipuleucel-T provides a second option beyond docetaxel for the treatment of men with metastatic CRPC. Of note, although the majority of patients in that study were chemotherapy-naïve, a number of men (about 15%) had received prior treatment with docetaxel.27 In addition, in October 2010, overall survival results were presented from a Phase III placebo-controlled clinical trial of abiraterone acetate, a CYP17 inhibitor that impairs extra-gonadal androgen synthesis, demonstrating an overall survival advantage in men with metastatic docetaxel-pretreated CRPC randomized to abiraterone or placebo (median survival 14.8 versus 10.9 months).33 These are examples of an encouragingly large variety of new agents that have made their way into Phase III clinical trials in metastatic CRPC, and have added to the therapeutic arsenal in this disease. Table 4 summarizes efficacy and toxicity data for some of the new agents described above, and also highlights several other promising drugs which are also currently in Phase III development.

Table 4.

New agents for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

| Drug (trade name, manufacturer) | Mechanism | Toxicities | Target population | Outcomes from completed trials | Ongoing trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabazitaxel (Jentava, Sanofi-Aventis) | Tubulin-binding taxane | Neutropenia, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea | mCRPC, docetaxel-refractory | (Phase III study) OS 15.1 vs 12.7 months for mitoxantrone (HR = 0.7; P < 0.001)20 | See “Critical appraisal” section above |

| MDV3100 (Medivation) | Androgen receptor antagonist | Fatigue, seizure in 3 patients | mCRPC, docetaxel-refractory or docetaxel-naïve | (Phase I/II study) PSA responses in 56% of men; radiographic responses in 22% of men; stable bone disease for 12 weeks in 56% of men32 | Phase III AFFIRM trial: MDV3100 vs. placebo in docetaxel-pretreated men with metastatic CRPC [NCT00974311] |

| Abiraterone (Cougar/Johnson and Johnson) | Androgen biosynthesis inhibitor that blocks CYP17 | Edema, hypokalemia, LFT elevation | mCRPC, docetaxel-refractory | (Phase III study) OS 14.8 vs 10.9 months for placebo (P < 0.0001). TTPP 10.2 vs 6.6 months (P < 0.0001). PSA response rate 38% vs 10% (P < 0.0001)33 | Phase III study of abiraterone vs. placebo in men with metastatic CRPC, chemotherapy-naïve [NCT00887198] |

| Custirsen (OGX-011, OncoGenex) | Apoptosis-inducing agent; targeting clusterin | Rash, fever, rigors, diarrhea, leucopenia, elevated creatinine | mCRPC, chemotherapy-naïve | (Phase II study) OS 23.8 months for custirsen and docetaxel vs 16.9 months for docetaxel alone (P = 0.06), but study not powered for OS34 | Phase III trial of docetaxel retreatment ± custirsen for men with docetaxel-refractory mCRPC [NCT01083615] |

| ProstVac-VF (Bavarian Nordic) | Poxviral-based immunotherapy | Injection-site reactions, fatigue, chills, nausea | mCRPC, chemotherapy-naïve | (Phase II study) Three-year OS 30% vs 17% in placebo group Median survival 25.1 vs 16.6 months (HR = 0.56, P = 0.006)35, but study was not powered for OS | Randomized Phase II trial of docetaxel ± ProstVac-VF in men with metastatic CRPC, chemo-naïve [NCT01145508] |

| Sipuleucel T (Provenge, Dendreon) | Autologous APC-based cellular immunotherapy | Chills, fever, headaches | mCRPC, chemotherapy-naïve (and some chemotherapy-pretreated) | (Phase III IMPACT trial) Median OS 25.8 vs 21.7 months for placebo (P = 0.03); 3-year OS 31.7% vs 23%27 | Phase III study in newly-diagnosed hormone-naïve patients with mCRPC, examining hormone therapy ± sipuleucel-T [currently being planned] |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; TTPP, time to PSA progression; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PFS, progression free survival; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; HR, hazard ratio; APC, antigen-presenting cell; LFT, liver function tests.

At present, cabazitaxel is confined to post-docetaxel second-line therapy, but an upcoming head-to-head comparison against docetaxel could change that situation.23 In addition, two trials of cabazitaxel in combination with other agents have been launched. These trials combine cabazitaxel with cisplatin (NCT00925743) and cabazitaxel with gemcitabine (NCT01001221), both in the Phase I/II setting in advanced solid tumors. Even more promising in the post-docetaxel space may be trials that will combine cabazitaxel with the next generation of androgen-inhibiting agents such as abiraterone and MDV3100. If cabazitaxel also acts through androgen receptor signaling (as does docetaxel), there could be synergistic effects from such combinations.23 Finally, other investigators are planning a Phase I trial combining cabazitaxel with mitoxantrone and prednisone in patients with metastatic CRPC who have not previously been treated with chemotherapy for metastatic disease. This strategy relies on the fact that these two chemotherapeutic agents have nonoverlapping patterns of toxicity.

Financial considerations for cabazitaxel

The market for docetaxel was $2.6 billion in 2009, accounting for more than half of the $4.6 billion market for plant-derived anticancer agents. Between 2004 and 2009, the market for all plant-derived anticancer drugs grew at 3% per year.28 Because many CRPC patients become refractory to docetaxel chemotherapy or develop grade 3/4 toxicities within 4–6 months of docetaxel treatment, the eventual market for cabazitaxel may be expected to be comparable to that of docetaxel. Furthermore, the price per cycle for cabazitaxel is US$5, 598,29 which is more than twice the cost per cycle of docetaxel (US$2, 483),30 underpinning financial analysts’ estimates that cabazitaxel sales may grow to US$300 million by 2013 and US$500 million by 2016.31 Because these estimates only reflect the second-line use of cabazitaxel, the market for this agent could rise even further if it is also approved for first-line use in men with CRPC.

Conclusion

Treatment with cabazitaxel and prednisone was approved by the FDA in June 2010 as the first therapy that offers a survival benefit in men with metastatic CRPC whose disease progresses during or after docetaxel treatment. The TROPIC trial showed a significant overall survival advantage of 2.4 months using second-line cabazitaxel over mitoxantrone in such patients. Because of the large incidence of febrile neutropenia (and neutropenic deaths), this agent should be administered cautiously and with appropriate monitoring. To this end, careful patient selection, and use of concurrent growth factor support, is paramount for the safe prescribing of this novel taxane agent. Dose-reductions to 20 mg/m2 may often be necessary, and this lower dose will now be incorporated into future trials. The modest survival benefit observed with cabazitaxel may be even greater if combined judiciously with other targeted therapies, ultimately resulting in a cumulative improvement in the lifespan of metastatic CRPC patients. Finally, the comparative effectiveness of cabazitaxel versus docetaxel in the first-line setting remains to be defined.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1999;281(17):1591–1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchio EM, Aslan M, Wells CK, Calderone J, Concato J. Impact of biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer among US veterans. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1390–1395. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonarakis ES, Trock BJ, Feng Z, et al. The natural history of metastatic progression in men with PSA-recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: 25-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl) abstract 5008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Amico AV, Cote K, Loffredo M, Renshaw AA, Schultz D. Determinants of prostate cancer-specific survival after radiation therapy for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(23):4567–4573. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tannock IF, Osoba D, Stockler MR, et al. Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer: a Canadian randomized trial with palliative end points. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(6):1756–1764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1513–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Approval Package for: Jevtana. Jun 17, 2010. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/201023s000Approv.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2011.

- 10.Jordan MA, Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(4):253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanofi-Aventis Jevtana prescribing information. Jun 17, 2010. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/201023lbl.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2011.

- 12.Bradshaw DM, Arceci RJ. Clinical relevance of transmembrane drug efflux as a mechanism of multidrug resistance. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(11):3674–3690. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. A family of drug transporters: the multidrug resistance-associated proteins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(16):1295–1302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowinsky EK, Smith L, Wang YM, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of paclitaxel in combination with biricodar, a novel agent that reverses multidrug resistance conferred by overexpression of both MDR1 and MRP. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(9):2964–2976. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mita AC, Denis LJ, Rowinsky EK, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of XRP6258 (RPR 116258A), a novel taxane, administered as a 1-hour infusion every 3 weeks in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(2):723–730. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates SF, Chen C, Robey R, Kang M, Figg WD, Fojo T. Reversal of multidrug resistance: lessons from clinical oncology. Novartis Found Symp. 2002;243:83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingston DG. Tubulin-interactive natural products as anticancer agents. J Nat Prod. 2009;72(3):507–515. doi: 10.1021/np800568j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkes G. Cabazitaxel, a taxane for men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2010;24(10 Suppl):46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pivot X, Koralewski P, Hidalgo JL, et al. A multicenter phase II study of XRP6258 administered as a 1-h i.v. infusion every 3 weeks in taxane-resistant metastatic breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(9):1547–1552. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomized open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Bono JS, Sartor O. Cabazitaxel for castration-resistant prostate cancer – author’s reply. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):122–123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sartor O, Halstead M, Katz L. Improving outcomes with recent advances in chemotherapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2010;8(1):23–28. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2010.n.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shigeta K, Miura Y, Naito Y, Takano T. Cabazitaxel for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):121. 122–123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60012-3. author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pal SK, Twardowski P, Sartor O. Critical appraisal of cabazitaxel in the management of advanced prostate cancer. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:395–402. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S14570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froehner M, Wirth MP. Cabazitaxel for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):121–122. 122–123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60013-5. author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.IMS MIDAS IMS Health. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manifold C. Cabazitaxel (Jevtana): another arrow in the prostate cancer quiver. Informulary. 2010;3(6):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsey SD, Clarke L, Kamath TV, Lubeck D. Evaluation of erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: impact on the budget of a US health insurance plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12(6):472–478. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.6.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baum A. Sanofi-Aventis Sales Model for 2009–2016. In: Paller C, editor. Private correspondence from Morgan Stanley Smith Barney, October 6, 2010 detailing the Sanofi-Aventis Sales Model for 2009–2016, prepared by Andrew Baum, European Pharmaceutical Analyst. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, et al. Antitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1–2 study. Lancet. 2010;375(9724):1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus low-dose prednisone improves overall survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have progressed after docetaxel-based chemotherapy: results of COU-AA-301, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase III study. Ann Oncol; 35th ESMO Congress; 2010 Oct 8–12; Milan, Italy. 2010. p. viii. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chi KN, Hotte SJ, Yu EY, et al. Randomized phase II study of docetaxel and prednisone with or without OGX-011 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4247–4254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kantoff PW, Schuetz TJ, Blumenstein BA, et al. Overall survival analysis of a phase II randomized controlled trial of a Poxviral-based PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1099–1105. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]