Abstract

The HIV epidemic is a health crisis in rural African American communities in the Southeast US, however to date little attention has been paid to community-academic collaborations to address HIV in these communities. Interventions that use a community-based participatory (CBPR) approach to address individual, social and physical environmental factors have great potential for improving community health. Project GRACE (Growing, Reaching, Advocating for Change and Empowerment) uses a CBPR approach to develop culturally sensitive, feasible and sustainable interventions to prevent the spread of HIV in rural African American communities. We describe a staged approach to community-academic partnership: initial mobilization; establishment of organizational structure; capacity building for action; and planning for action. Strategies for engaging rural community members at each stage are discussed, challenges faced and lessons learned are also described. Careful attention to partnership development has resulted in a collaborative approach that has mutually benefited both the academic and community partners.

Keywords: CBPR, rural communities, African American, HIV prevention

Introduction

Despite the introduction of prevention measures, the HIV epidemic has become more deeply entrenched in the US, especially among African Americans, whose HIV rates now soar above those of whites. No where is addressing this epidemic more critical than in rural African American communities in the southeastern United States. Against this backdrop, community based participatory research (CBPR) has gained increased attention as an approach to address disparities in health. A collaborative process that engages multiple partners may be particularly relevant in addressing complex problems like HIV (Turning Point, 2006).

Background

CBPR is research conducted by partnerships between academic and community researchers with the goal of increasing the value of the research product for both partners (Viswanathan, Ammerman, & Eng, 2004). CBPR acknowledges the unique strengths and insights that community and academic partners bring to framing health problems and designing solutions (Brody et al., 2004; Brody et al., 2006; Murry, Berkel, Brody, Gibbons, & Gibbons, 2007). Despite the recognized benefits to research design and implementation, relatively few HIV interventions have been designed using participatory methods, and few CBPR efforts, of any kind, have been described in rural communities (Kim, et al., 2006; Marcus et al., 2004; Rhodes, et. al, 2006; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, & Jolly, 2008; Romero et al., 2006). While the underlying and guiding principles of CBPR partnerships may be similar across collaborations, each setting provides its own unique challenges that are rooted in the social context and the nuances of that community. In this paper, we describe how the close-knit setting of a rural community and the context of HIV influenced the process of partnership development. Project GRACE (Growing, Reaching, Advocating for Change and Empowerment), a collaborative partnership that draws on the strengths of community, academic and public partners, was created to develop culturally specific prevention interventions in a rural African American community with high HIV rates. Here we describe the staged approach we used in the process of developing our community-academic partnership in Project GRACE and discuss factors to be considered in partnerships in rural communities.

One of the initial challenges of using a CBPR approach is coming to a shared definition of community among all of the partners. Communities are complex associations defined by geography, shared history, cultural identity, and other social bonds. In Project GRACE, we decided to use the defining elements of community as a group of people with existing relationships who share a common interest, living in the same geographic area or sharing similar ethnic/cultural background (Kone et al., 2000; MacQueen et al., 2001; Viswanathan et al., 2004). We also incorporate the notion of “communities of identity,” characterized by a sense of identity and emotional connection to other members, shared norms and values and commitment to meeting common needs (Steuart, 1993). (Steuart, 1993). Project GRACE defines the community we serve as rural African American communities of Edgecombe and Nash, two contiguous counties in rural North Carolina. These counties share one city, Rocky Mount; the high rate of HIV in this shared city is an important defining element and an unfortunate bridge between both counties. Edgecombe County had a three year average rate of 40.2 (per 100,000) HIV cases from 2005 to 2007, and Nash had a rate of 21.1 (NC Division of Public Health, 2009). In Nash County, 82% of people with HIV/AIDS are African American, although only 34% of the county’s population was African American; in Edgecombe County, 86% of HIV/AIDS cases are African American, where African Americans make up 58% of the county population. Nash and Edgecombe County Health Departments, 2007).

Strategies

Project GRACE used a staged approach to partnership development, guided by a developmental model (Florin, Mitchell, & Stevenson, 1993; VanDevanter et al., 2002). In this manuscript, we focus on the early stages of partnership development: initial mobilization; establishment of organizational structure; capacity building for action; and planning for action. All Project GRACE activities occurred in parallel with the intended result of reinforcing and strengthening the Consortium through a cyclical and iterative process of partnership development (Viswanathan et al., 2004). We focus here on these first four stages because attention to these early developmental stages has been critical to the long term goal of design and implementation of successful and sustainable interventions (Brewster, 1993; Ku, Sonenstein, & Pleck, 1993; South, 2000). In addition this focus on the process of partnership development can highlight the challenges and successful strategies of implementing building CBPR partnerships in rural settings.

Stage 1: Initial Mobilization

Establishing the Project GRACE Consortium began as an outgrowth of writing a planning proposal for funding (NIH, 2005). University investigators reached out to the communities of interest through a series of open meetings to discuss the funding mechanism, health problems of interest to the community, and the expectations of established community based organizations (CBOs) to work in tandem with university investigators to address the problem. During these early meetings community members and leaders identified HIV as an important health issue of concern.

As we developed our Consortium, we paid particular attention to identifying and inviting key stakeholders to join in order to ensure a range of community perspectives. Members of organizations in attendance at the initial meeting were encouraged to “spread the word” in their communities to solicit participation from other organizations, agencies and community activists. Since those initial meetings, Project GRACE has grown from 15 members to include more than 94 individual community members and representatives of local community based organizations, health, social service and faith based organizations.

In our initial grant writing we applied the principles of CBPR by developing the proposal using teams of investigators and community members who provided insight into the feasibility of the proposed approach, funding and design of the proposed planning activities to ensure full participation of all of the initial members of the partnership. Once funded by a grant from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities to UNC-Chapel Hill, we used subcontracts to community based organizations to ensure that financial resources were divided equitably between university and community partners. A community outreach specialist (COS) was hired from the community to work with the university based project coordinator and representatives of the various subcontracting organizations to develop a matrix of community service providers, local leaders and influential persons within both communities. The COS contacted potential Consortium members to describe the project and invite him or her to one of the quarterly Consortium meetings. We have found that personal contact is an essential element to successful recruitment of Consortium members. In addition, we have encouraged Consortium members to recruit new members into the Consortium. We have also created an email listserv that can be accessed by Consortium members to share information about upcoming community events, professional development activities, and provide updates about Project GRACE through a weekly newsletter. The listserv is designed to increase the sense of connectedness among community organizations, institutions, and activists.

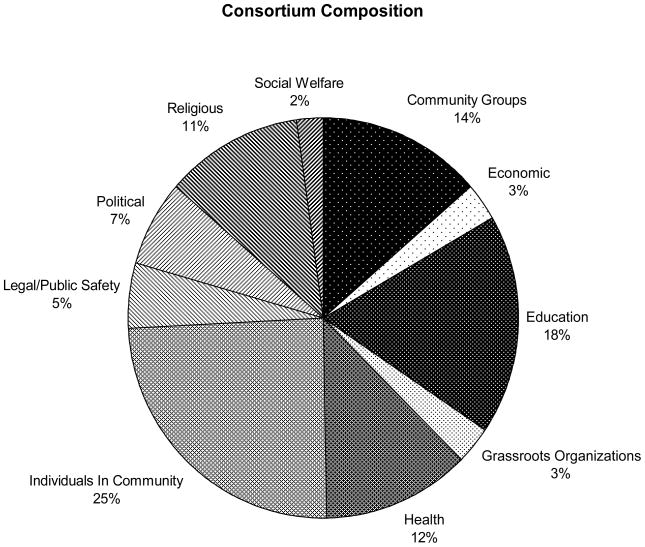

Broad and appropriate representation in the Consortium has been essential to ensuring the relevance and acceptability of the intervention in the community. Consortium members drew on their knowledge of the community, professional and social networks to extend invitations to stakeholders that represented a broad range of community viewpoints. While some of the organizations in our partnership have a health focus, there are others that have missions that are not explicitly health related. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Composition of Project GRACE Consortium

Early on, we acknowledged that communities change and evolve as does the leadership and membership of community organizations. Thus, we have employed an ongoing process of reflecting on the current Consortium membership, considering potential gaps in our community representation and extending invitations to new Consortium members.

We learned early that repeated invitations issued in a variety of formats leads to sustained attendance at Consortium meetings. For example, the COS assists with publicizing quarterly Consortium meetings through local media outlets, extending both written and verbal invitations, and visiting local churches and community gatherings to raise awareness about the project and notify attendees about upcoming meetings. Initial attempts to communicate primarily through email yielded less than favorable attendance at early Consortium meetings, and subsequent conversations with community members led us to change our communication methods to reflect preferred communication patterns within the community. Personal invitations are highly valued and have yielded higher attendance at meetings and greater involvement in project activities.

Initial meetings were devoted to sharing information about the aims of the study, the principles of community-based participatory research, and the expectations for mutual participation, decision-making and benefit. As the project began its needs and assets assessment, we originally attempted to share our findings using very didactic approaches. However, we soon realized that we needed a more interactive approach to sharing information. In order to create an inclusive atmosphere, we asked small groups from the community to work with the project coordinator to develop agendas for Consortium meetings. The result was an approach that allowed for brief presentations of information by the principal investigator accompanied by more lengthy discussion sessions moderated by community members. This approach helped us sustain the momentum generated in those early meetings by providing a concrete way to engage Consortium members and provided a fuller context for the qualitative data we were gathering in the needs and assets assessment. For example, when we presented information about area youth’s feelings about the current state of sex education in schools, Consortium members engaged in a lively and informative discussion about previous efforts to improve the quality of sex education and what had and had not worked for their community.

Stage 2: Establishing Organizational Structure

Establish Steering Committee

Project GRACE uses the governing structure of a steering committee, comprised of representatives from all contracting and subcontracting partner organizations and community leaders in each county (See Table 1). The steering committee is primarily charged with the management and conduct of all project related activities. We have chosen a steering committee rather than a Community Advisory Board to emphasize equal partnership, collective decision-making and active participation of all members.

TABLE 1.

Composition of Steering Committee

| Service Area | Seats Allotted | Organizations Represented |

|---|---|---|

| Community Based Organizations (CBOs) | 7 |

|

| Health Departments/Agencies | 4 |

|

| Academic Institutions | 4 |

|

| At-Large Representatives | 4 |

|

| Ex-Officio Members | 10 |

|

The steering committee was initially made up of representatives from subcontracting organizations and volunteers who attended the proposal-writing sessions. These representatives recruited others from within the community to fill the seats on the steering committee. The original structure of the steering committee allowed for 19 members of the committee. As the steering committee expanded, we realized that we needed to accommodate the community’s growing interest in our project. We had anticipated that the greater community would only want to be involved in the quarterly Consortium meetings, but we soon found that attendance at our monthly steering committee meetings consistently exceeded the number of seats on the committee. In order to recognize and give voice to the individuals and organizations who attended the steering committee meetings despite their not having a seat on the committee, we created ex-officio memberships. This strategy allowed us to acknowledge the interest of these organizations and individuals while limiting the number of seats on the steering committee to a manageable number that allowed the committee to conduct regular business. The creation of ex-officio memberships has had the additional advantage of providing the steering committee with ready and willing members when seated individuals and organizations have been unable to continue in their positions.

Steering Committee Functions

The steering committee meets on a monthly basis. Early meetings were devoted to identifying other community members to be included in the Consortium, development of operating principles and guidelines and defining roles. The steering committee is also responsible for defining job descriptions, interviewing and making recommendations for key staff positions. During periods of data collection and analysis a portion of the steering committee meetings are devoted to reviewing data and findings and collectively refining the conceptual framework of influences on the spread of HIV based on data gathered in the needs and assets assessment, described below.

In addition to working committee meetings and monthly steering committee meetings, Project GRACE also has an annual retreat that includes all Consortium members and staff involved in the project. During this annual retreat we review progress and identify goals for the coming year. The annual retreats provide an opportunity to first identify then strengthen priorities and a shared vision for change (Schulz et al., 2001). During both the annual retreats and monthly meetings, there are opportunities to identify needed areas for further co-learning, training and education.

Working Committees

We created working committees to conduct the business of Project GRACE. Currently, we have 6 working committees that address key methodological and logistical aspects of the project (See Table 2). Five committees are chaired or co-chaired by community partners and all Consortium members are able to sign up for one or more working committees.

TABLE 2.

Description of Working Committees

| Committee | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Membership & By-Laws |

|

| Nominating |

|

| Research Design |

|

| Communications & Publications |

|

| Events Planning |

|

| Fiscal/Budget |

|

Operating Guidelines and By-laws

A critical early activity was the establishment of the governing structure, operating guidelines and by-laws, developed jointly by all members of the steering committee and approved by the Consortium. The establishment of the core values of the Consortium was the guiding principles upon which all activities have been built. These core values and operating guidelines reinforce the key principles of CBPR (i.e., co-learning about issues of concern; sharing of decision making power and mutual ownership of products and processes of research) and emphasize the Consortium’s commitment to the use of those principles to address racial disparities in health (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Viswanathan et al., 2004).

Stage 3: Capacity Building for Action

Build Partnership Capacity

All of the above activities are designed to support the development of strong, trusting working relationships between all Consortium members. As part of the initial steps of establishing the Consortium, all current and invited members took part in the workshop, Changing Racism and Other “Isms” - A Personal Approach to Multiculturalism, conducted by VISIONS, Inc. VISIONS, Inc is an African American-owned company based in Rocky Mount, North Carolina which provides consultation, training and support to community development projects confronting and challenging oppression at the institutional, cultural, interpersonal and personal levels. Racial, economic and other forms of oppression are the underpinnings for many of the environmental and contextual determinants of the spread of HIV in the African American community. At the outset, community partners strongly urged the inclusion of initial training with VISIONS and ongoing consultation. We included this type of training both to build the capacity of our partnership to recognize and address forms of oppression external to our collaboration that may be major influences on the spread of HIV and also to see how different forms of oppression operate with and between partnership members.

The 4-day workshop was designed to allow Consortium members 1) to come to a shared understanding of the role oppression plays in creating the environmental and contextual factors undergirding racial disparities, and 2) to identify characteristics of the structure and climate of organizations within the community that may contribute to the spread of HIV. This workshop has played a pivotal role in all partners coming to a shared understanding of structural factors in the spread of HIV in African American communities. In addition, the workshop has given us communication and problem solving tools that have been invaluable in terms of identifying and addressing partnership conflicts and celebrating successes in a manner that advances the work of the partnership. The 4 day workshop is repeated periodically to ensure that new staff, steering committee or consortium members all have a shared vision and similar orientation to our partnership and work. The annual retreats also use the VISIONS multiculturalism and organizational learning model and tools, and they provide both an opportunity for introducing the tools to new members and also practice for experienced learners in the process of meeting organizational objectives.

Evaluation of the CBPR process

Documenting adherence to CBPR principles has been noted to be important in determining the quality of reports of CBPR projects (Lantz, Viruell-Fuentes, Israel, Softley, & Guzman, 2001; Naylor, Wharf-Higgins, Blair, Green, & O'Connor, 2002; Patton, 1990; Viswanathan et al., 2004). Prior to each Project GRACE annual retreat, consultants evaluate the extent and ways in which CBPR principles have been adhered to throughout the course of the planning project using semi-structured interviews. The process evaluation focuses on the following areas: a) knowledge of the project and content area; b) facilitators, barriers and recommendations; c) “–isms” and cultural differences; and d) empowerment. During the annual retreat, the results of the evaluation are presented to the steering committee and used as a basis for strategic planning and changes in Consortium activities, procedures and policies.

Stage 4: Planning for Action

Project GRACE chose to conduct both a needs and assets assessment to identify community needs, resources, goals and objectives, and to guide the choice of strategies and plan for intervention implementation. The process of identifying both community needs and resources or assets, underscores our view of Project GRACE and its activities as facilitators of social change and community empowerment. In recent years, there has been an increasing call to use strengths-based rather than deficit-based approaches to health, representing a reorientation in our approach to health promotion. Strengths-based approaches have great appeal, because they do not emphasize what is wrong but rather identify that which is helpful and can be learned. We believe that rather than seeing minority or underserved communities as deficient or needing services, it is important to recognize that all communities have unique strengths and resources that should be supported and built upon as a starting point for building community capacity and designing sustainable interventions. The rationale behind the proposed methods of community needs and assets assessment is that information is needed for change and community empowerment (Hancock & Minkler, 1997). Therefore, our assessment a) identified key informants’ and stakeholders’ perceptions of the needs, strengths and resources in Edgecombe-Nash counties using semi-structured interviews; and b) described community members’ perceptions of contributors to the spread of HIV in their communities and possible targets for intervention through focus group interviews.

Lessons Learned and Discussion

As described by others that have adhered to the principles of participatory research, our attention to process in Project GRACE has led to deep engagement of all partners (Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003). All data collection, analysis and interpretation have been conducted collaboratively. Community and academic partners have co-led the development of the intervention materials and evaluation tools. All products for dissemination are generated collaboratively and reviewed by a team of steering committee members before any presentations or submissions. The need to build in more time for this collaborative effort has also been described (Baker, Homan, Schonhoff, & Kreuter, 1999; Schulz et al., 2001). However, there are lessons that we could not find ready answers to in the CBPR literature. Much of the CBPR literature has described the application of this methodology in partnership with communities in urban centers (Higgins & Metzler, 2001; Israel et al., 2001; Marcus et al., 2004; Merzel et al., 2007). We found little in the scholarly literature to guide our work in rural communities and of the application of CBPR in HIV prevention (Kim et al., 2006; Marcus et al., 2004; Rhodes et al., 2007; Romero et al., 2006). The use of CBPR to address the spread of HIV in rural African American communities posed some unique challenges and opportunities.

The backdrop of HIV

HIV in rural African American communities in the south was the galvanizing force for starting the partnership. The profound impact of HIV morbidity and mortality on our communities has maintained the momentum of our partnership. Several members of the partnership had family members or friends that were HIV positive; all members were passionate about the need to reduce the impact of HIV on the African American community. This unifying commitment was critical in forming the partnership before we received grant funding and an important shared concern we relied on when we faced inevitable challenges. It is likely that our resolve was heightened due to the intense HIV related stigma that is present in small rural towns in the South. Conversely, HIV related stigma was likely our main barrier to engagement to some sectors of the community. While we have partnered on individual outreach events, members of the faith community have not been as widely or consistently represented as we would have hoped.

Close knit and geographically isolated communities

While it is important to acknowledge that there are challenges to CBPR that are universal across partnerships, the social and geographic context of rural settings also provides a unique set of issues. The dense and overlapping social networks of African American communities coupled with geographic isolation of rural areas revealed both strengths and challenges. Because of the smaller populations and the overlap between social and professional networks, the small community setting afforded us greater certainty in our goal of ensuring that a wide range of views and perspectives were represented in the members of our Consortium. However, we also saw that the density and overlapping nature of these networks, at times, became problematic in the workings of the Steering committee. For example, in our efforts to be inclusive and egalitarian in the decision making of the Steering committee, Project GRACE has inadvertently flattened or inverted social and professional hierarchies, creating unanticipated problems. In one instance an employee of one community based organization chaired a Project GRACE working committee that his supervisor was a part of, requiring him to be directive about the completion of tasks of the committee. This inversion of a professional hierarchy, where the employee in one setting takes on a leadership role within the partnership, was exacerbated by the relatively small number of agencies and organizations to draw from in a rural setting.

We also found that prior and existing social relationships could both facilitate and hinder the work of the partnership and interagency collaboration. Unlike in more urban environments, individuals in our communities seldom rotate in or out of social, professional, or geographic circles, generating a sense of connectedness that is unique to rural communities. We learned that professional relationships and personal lives often intersect in communities that have such dense social networks, complicating the work of the project. For example, spouses and significant others often work for the same or complementary organizations within the community. When their personal relationships became difficult, the partnering organizations were often aware of the difficulties and had to actively work at avoiding being drawn into them or allowing them undue weight when making decisions about the project. Issues of trust and trustworthiness were also magnified due to the overlapping relationships. Unlike in more metropolitan areas where individuals or agencies might be known solely on the basis of their professional reputations, our partners had extensive knowledge of one another’s professional and family histories, their relationships, personalities, religious preferences, and many other deeply personal details that both aided in creating trust between partners and, at times, hindered it.

The challenge of context and overlapping social and professional networks required us to pay particular attention to how reporting structures and power dynamics in one setting could negatively influence the work in another. VISIONS, Inc provided support in negotiating these types of conflicts so that the work of the project could continue despite difficulties between individuals or within organizations. We chose to have the VISIONS process consultant at each steering committee meeting to facilitate discussions around sensitive issues and address tension and conflict. Having a consultant skilled at conflict resolution that understands and is respected by members of the community was critical to our success. Through careful and deliberate attention to the process of partnership development and coalition building, we were able to explicitly address tensions and the unintended consequences of the CBPR methods in this rural community.

Multiple roles of partners

As in other partnerships, community members often held multiple professional roles in our community. As we thought about the needs of the partnership we explicitly drew on the skills available among our partners to ensure community leadership. In the initial formation of the working committees, rather than asking for volunteers, our steering committee chair explicitly asked community members to serve as chairs of working committees, taking into account the unique needs of the committee and the existing skills of potential chairpersons. For example, the chair of the bylaws committee is an executive director of a community based organization with prior experience drafting bylaws for non-profit organizations. She was able to draw on that expertise in her role as chair. This deliberate and early attention to community leadership in the working committees set a positive tone for the partnership in decision-making for the project and allowed Project GRACE to benefit from the expertise of individuals and organizations within the community.

In addition, as might be expected, steering committee members are advocates for social change in a variety of settings. Many of the steering committee members are community leaders that hold either formal positions as elected officials and/or informal roles as community activists and many are advocates for HIV prevention and treatment. While the shared values and vision for change were essential to effective partnership, we found that at times lines could be blurred when community organizing and advocacy work was involved. As a steering committee, we found we were faced with answering complicated questions such as: When did advocacy for the goals of the project begin and end? Were there potential conflicts of interests between individual’s advocacy work and efforts to accomplish project goals and how could we resolve such conflicts? How important was it to make distinctions between individual’s personal ideals and the goals of the partnership? How would we account for the multiple roles of some community members who serve as both Steering Committee members and project staff? How would we position ourselves for effective advocacy while avoiding being unwittingly drawn into local political issues? These types of issues become magnified in smaller communities where there may be considerable overlap between professional and social roles and networks. For example, several steering committee members have run for political office and used the data collected in Project GRACE to support their political platform. The need to address environmental factors in HIV/STI prevention became a prominent issue in the last election cycle in Edgecombe and Nash counties. We see this type of social action as an expected outcome of CBPR research and have chosen to make these data as available as possible to all members of the Consortium and broader community for their use in striving for social change.

Conclusions

Using a staged approach to partnership development provided a systematic and transparent way to ensure that all partners were informed about and engaged in the progression of the partnership development. Each stage reinforced the goals of the partnership and provided clear guidance for practical implementation of the principles of participatory research. This structure also allowed us to take advantage of the unique opportunities available to address challenges specific to community-academic partnerships in rural settings. Our early attention to the process of partnership development has provided a strong foundation for intervention development and evaluation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of all steering committee members in the development of Project GRACE Consortium: Larry Auld, Reuben Blackwell, Hank Boyd, III, John Braswell, Angela Bryant, Cheryl Bryant, Don Cavellini, Trinette Cooper, Dana Courtney, Eugenia Eng, Jerome Garner, Vernetta Gupton, Davita Harrell, Shannon Hayes-Peaden, Stacey Henderson, Doris Howington, Clara Knight, Gwendolyn Knight, Taro Knight, Patricia Oxendine-Pitt, Donald Parker, Reginald Silver, Doris Stith, Jevita Terry, Cynthia Worthy.

This work was funded by grants from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24MD001671) and the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (UNC CFAR P30 AI50410). Dr. Corbie-Smith is a Health Disparities Scholar with the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

The final, definitive version of the article is available at http://hpp.sagepub.com/content/early/2010/08/03/1524839909348766

References

- Baker EA, Homan S, Schonhoff R, Kreuter M. Principles of practice for academic/ practice/community research partnerships. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16(3 Suppl 1):86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster K. Social Context and Adolescent Behavior: The Impact of the Community on the Transition to Sexual Activity. Social Forces. 1993;71(3):713–740. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, McNair L, et al. The strong African American families program: prevention of youths' high-risk behavior and a test of a model of change. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43) 2006;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, et al. The Strong African American Families Program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75(3):900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin P, Mitchell R, Stevenson J. Identifying training and technical assistance needs in community coalitions: a developmental approach. Health Education Research. 1993;8(3):417–432. doi: 10.1093/her/8.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock T, Minkler M. Community health assessment: Whose community? Whose health? Whose assessment? In: Minkler M, editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DL, Metzler M. Time for a National Agenda to Improve the Health of Urban Populations. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2001;78(3):488–494. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Lichtenstein R, Lantz P, McGranaghan R, Allen A, Guzman JR, Softley D, Maciak B. The Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center: development, implementation, and evaluation. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice: JPHMP. 2001;7(5):1–19. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200107050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Linnan L, Campbell MK, Brooks C, et al. The WORD (Wholeness, Oneness, Righteousness, Deliverance): A Faith-Based Weight-Loss Program Utilizing a Community-Based Participatory Research Approach. Health Education and Behavior. 2006;35 doi: 10.1177/1090198106291985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kone A, Sullivan M, Senturia KD, Chrisman NJ, Ciske SJ, Krieger JW. Improving collaboration between researchers and communities. Public Health Reports. 2000;115(2–3):243–248. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, Sonenstein F, Pleck J. Neighborhood, family, and work: Influences on the premarital behaviors of adolescent males. Social Forces. 1993;72(2):479–503. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Viruell-Fuentes E, Israel BA, Softley D, Guzman R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community-based participatory research partnership in Detroit. Journal of Urban Health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2001;78(3):495–507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Strauss RP, Scotti R, Blanchard L, Trotter RT., 2nd What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(12):1929–1938. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus MT, Walker T, Swint JM, Smith BP, Brown C, Busen N, et al. Community-based participatory research to prevent substance abuse and HIV/AIDS in African American adolescents. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2004;18(4):347–359. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzel C, Burrus G, Davis J, Moses N, Rumley S, Walters D. Developing and Sustaining Community–Academic Partnerships: Lessons From Downstate New York Healthy Start. Health Promotion Practice. 2007;8(4):375–383. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Berkel C, Brody GH, Gibbons M, Gibbons FX. The Strong African American Families Program: Longitudinal pathways to sexual risk reduction. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2007;41(4):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash County Health Department. Nash County Statistical Analysis Query Report. 2007. Retrieved on April 1, 2007, from Nash County Health Department database. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor PJ, Wharf-Higgins J, Blair L, Green L, O'Connor B. Evaluating the participatory process in a community-based heart health project. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(7):1173–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NC Division of Public Health. NC DHHS Publication. North Carolina: N.C. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. North Carolina 2008 HIV/STD Surveillance Report. [Google Scholar]

- NIH. NCMHD Community Participation in Health Disparities Intervention Research. 2005 Retrieved July 9, 2008 from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-MD-05-002.html.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. California: Sage Publication; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montaño J, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Bowden P. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Develop an Intervention to Reduce HIV and STD Infections Among Latino Men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(5):375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin AM, Jolly C. Visions and Voices: Indigent Persons Living With HIV in the Southern United States Use Photovoice to Create Knowledge, Develop Partnerships, and Take Action. Health Promotion Practice. 2008;9(2):159–169. doi: 10.1177/1524839906293829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Wallerstein NB, Lucero J, Fredine HG, Keefe J, O'Connell J. Woman to Woman: Coming Together for Positive Change--using empowerment and popular education to prevent HIV in women. AIDS Education and Prevention: official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2006;18(5):390–405. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Lantz P. Instrument for evaluating dimensions of group dynamics within community-based participatory research partnerships. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2003;26(3):249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Parker EA, Lockett M, Hill Y, Wills R. The East Side Village Health Worker Partnership: integrating research with action to reduce health disparities. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(6):548–557. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50087-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South S, Baumer E. Deciphering community and race effects on adolescent premarital childbearing. Social Forces. 2000;78:1379–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Steuart GW. Social and cultural perspectives: community intervention and mental health. 1978. Health Education Quarterly, Supplement. 1993;1:S99–111. doi: 10.1177/10901981930200s109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turning Point. Turning Point-Collaborating for a New Century in Public Health. 2006 Feb 01; Retrieved n.d., from http://www.turningpointprogram.org/

- VanDevanter N, Hennessy M, Howard JM, Bleakley A, Peake M, Millet S, Cohall A, Levine D, Weisfuse I, Fullilove R. Developing a collaborative community, academic, health department partnership for STD prevention: the Gonorrhea Community Action Project in Harlem. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice: JPHMP. 2002;8(6):62–68. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 99. AHRQ Publication Number 04-E022-1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2004. Community-Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]