Abstract

Several studies have demonstrated higher risks of childbearing in stepfamilies, net of the total number of children stepfamily couples have. Analyzing retrospective data from a nationally representative sample of Swedish adults (Level of Living Survey 2000), we found that the risk of a second or third birth is elevated when it is the first or second child in a new union. We also found a faster pace of childbearing after stepfamily formation than after a shared birth. The risk of a second birth is only somewhat higher in a stepfamily after two years of observation. The risk of a third birth is particularly high early in the stepfamily union and remains higher than that for couples with two shared children for at least five years. The stepfamily effect was reduced after 1980 when the Swedish government introduced parental leave incentives for short birth intervals.

Keywords: Fertility, Stepfamilies, Family Demography, Family Size, Birth Timing

Introduction

The past three decades were a time of rapid family change in Europe, often referred to as the Second Demographic Transition (Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa 1986). Although fertility at below-replacement levels (2.1 children per woman) receives the bulk of scholarly and policy attention, the implications of changes in union formation and stability are equally important for family systems and the daily lives of family members. In most countries marriage is delayed or foregone, cohabitation is a precursor to and substitute for marriage, and both cohabiting and marital unions are less likely to endure through the childbearing years. As a result, young adults are increasingly likely to form new partnerships and have children with more than one partner.

Several studies demonstrate that ‘extra’ children are born in new unions, children who might not have been born if the original childbearing partnership remained intact (see review in Thomson et al. forthcoming). Although the evidence from these studies is quite compelling, they do not thoroughly deal with potential differentials in the pace as well as the probability of childbearing in new partnerships compared to those in which children have already been born. Previous studies may thus overestimate the stepfamily effect on fertility.

In this paper, we focus not only on the relative risk of childbearing in continuous parental partnerships and stepfamily partnerships but also on the implications of the timing of parental re-partnering in relation to prior births. Our analyses also provide a replication and extension (across periods and cohorts) of previous research on stepfamily childbearing in Sweden (Vikat et al. 1999).

Partnership and Parenthood in the Second Demographic Transition

The central feature of the Second Demographic Transition is the changing relationship between partnership and parenthood. Childbearing outside of marriage, in particular within cohabitation, is increasingly common, in some countries more common than childbearing in marriage (Sobotka and Toulemon 2008). Parental separation is also more common, for the most part because cohabiting parents are more likely to separate than married parents, but also because of rising divorce rates in many countries (Andersson 2002). These changes increase the pool of single parents, thus increasing the possibilities for formation of new partnerships. And because much of the partnership turnover occurs during the childbearing years, the new partnerships present opportunities for further childbearing

If individual desires for particular numbers of children were independent of the partnerships in which children are born, we would expect childbearing in stepfamilies to depend only on the number of previous children. Those who wanted two children altogether but had only one would have the second in a stepfamily; those who already had two would not. Griffith and colleagues (1985) argued, however, that new partnerships produce new motives for further childbearing. Having a child together establishes the legitimacy of the parents’ union (termed commitment value), while having a second child together provides a full sibling for the first (sibling value). Because couples in stepfamilies may already have at least one child, such motives can produce extra births when stepfamilies are formed. By specifying parity progressions in terms of shared and separate children, Thomson and colleagues (Vikat et al. 1999; Thomson et al. 2002; Vikat et al. 2004; Henz and Thomson 2005) found very strong support for the commitment value of a shared child and, in some instances, for the value of a full sibling for the first shared child in a stepfamily. Thomson (Thomson and Li 2002; Thomson 2004) demonstrated that patterns were similar for birth intentions as for observed births, supporting the underlying motivation-based theory. All of these effects are more pronounced for third and higher-order births due to the very high probability that a couple who has one shared child will also have a second.

All of these studies faced a common problem—how to estimate a stepfamily fertility differential while taking into account the fact that stepfamilies start out with at least one child while couples without stepchildren start out with none. Children born in stepfamilies will always be of higher birth order to at least one of their parents than children born to couples with only shared children. Some studies investigate parity progressions at the couple level, i.e., the effect of prior children on a couple’s first or second birth. These estimates always show that birth risks are lower or at least no greater in stepfamilies. Lower risks could be due entirely to the fact that the birth is of higher order when it occurs to a stepfamily couple than to a couple without stepchildren; equal risks may reflect the added value of a shared birth overcoming the expected negative effect of prior parity. To take into account the effect of previous parity on childbearing, one must compare stepfamilies to couples with the same number of children, all of whom are shared (Vikat et al. 1999; Thomson et al. 2002). That is, first births to couples without stepchildren do not contribute to the comparisons. Instead, the risk of a first birth to stepfamily couples is compared to the risk of a higher-order birth to couples with as many children together as the stepfamily couple has before their union.

A further problem when estimating the birth risk (as opposed to birth intentions) is how to specify the duration dependence for new stepfamilies and couples with a shared child who are at risk of another shared birth. Lillard and Panis (2003) noted that the risk of any particular event may depend on more than one duration parameter, or ‘clock’. In order to fully understand duration dependence of an event, one must identify the baseline clock and disaggregate any associated clocks that could confound estimated effects of fixed or time-varying characteristics (e.g., stepfamily status and parity) on the event’s risk.

Birth risks in partnerships may be influenced by at least three types of clocks—the prospective parent’s age, partnership duration, and the age of the youngest child. The parental age clock is likely to keep the same time for couples in stepfamilies and those with only shared children—the older the parent, the less likely she/he is fecund and the less likely she/he will want to begin a new long-term commitment to childrearing. The other two clocks may keep very different time, however, for new stepfamilies and for couples with shared children.

For couples with a shared child—whether or not they also have stepchildren—the most salient clock is the youngest child’s age. Strong preferences exist for spacing of births at two to three years and childbearing risks fall off quite steadily after the youngest child is five years old. A small part of the association between union formation and first births may be due to the selection of prospective parents into unions; but once the union is formed, duration has only small effects—positive or negative—on first birth risk (Baizan et al. 2003; 2004). Consequently, no particular incentives exist for a childless couple to have a child at any particular duration of union. Age is likely a more important clock for those without children, especially the age of the woman.

At the start of a stepfamily union, the youngest-child clock is set not at zero but on average at about five years. If the effect of the youngest stepchild’s age on childbearing risks after stepfamily formation is the same as the effect of the age of a shared child in continuing unions, very few children would be born in stepfamilies. The youngest stepchild’s age will be salient to the timing of births after a stepfamily union primarily in connection with the sibling relationship; a new baby may provide less sibling value, the older the youngest stepchild, i.e., the larger the gap in age between a child and her/his prospective half-sibling. Thus, the most salient clock becomes the duration of the stepfamily union because it parallels further increases in the youngest stepchild’s age. Furthermore, to the extent that the first shared child holds commitment value, the birth may be of high priority early in the relationship. Thus the pace of childbearing can be expected to be faster in the first one to two years of observation for stepfamily first births than in the first one to two years after a shared birth for couples of the same combined parity. As noted above, those who want (more) children may be more likely to form unions, including stepfamily unions. But such predispositions do not appear to be a source of a faster pace of childbearing following union formation.

Previous studies of the potential extra births produced by stepfamilies specified duration dependence in different ways. Vikat and colleagues (1999) used a discrete-time model in which both union duration and age of youngest child (shared or step) were included. This specification does not enable us to identify differences in either of these two duration dependencies for those with and without shared children. Thomson and colleagues (Thomson et al. 2002; Henz and Thomson 2005) specified the baseline clock as age of youngest child after a shared birth but as union duration in a new stepfamily, i.e. assuming that the pace of childbearing was the same after stepfamily formation as after the birth of a shared child. They did not consider effects of the age of youngest child in stepfamilies or effects of union duration for a second- or higher-order shared birth. Henz (2002) tested the interaction between duration and whether a spell began with a birth or the formation of a stepfamily union. She found in West Germany that couples with one child were more likely to have a second child if the first was not shared, but only during the first three years of the union. Using a large data set from the United States, Li (2006) demonstrated that the pace of childbearing in new marital stepfamilies was faster than the pace of childbearing after a marital birth. Once stepfamily couples had a common child, however, they exhibited the same duration dependence in having subsequent children as couples without stepchildren.

Although most of the previous research on stepfamily childbearing controls for period effects on fertility, none examine possible changes in the level or pace of childbearing in stepfamilies across time. Delays in family formation produce later separations and re-partnering, therefore making it harder for stepfamily couples to have one or two children together, even if they would like to do so (Thomson et al. forthcoming). In addition, in 1980, the Swedish government formalized a parental leave policy that encouraged closer spacing of second- and higher-order births and thereby not only reduced birth intervals but also increased the risk of second and third births (Hoem 1993; Andersson 2004). Because most stepchildren are more than two years old at the time of stepfamily formation, very few stepfamily couples could benefit from the spacing incentive. This means that in the later decades any extra incentive to have a second child who would be the first in a union would be counterbalanced by strong incentives to have a second shared child at a rapid rate after the first.

On the basis of arguments above, we identified and tested the following hypotheses:

Birth risks are elevated if a prospective child would be the first in a new partnership.

Birth risks are elevated if a prospective child would be the first full sibling to the couple’s shared child.

Elevated birth risks in new stepfamilies will be greater when the prospective birth is the third rather than the second.

The elevated risk of first stepfamily births will be less in policy contexts that favour close spacing of shared births.

Data and Methods

Data

We used data from the 2000 Swedish Level of Living Survey (LNU). The LNU is a 1/1000 random sample of the Swedish population between 15 and 75 years of age, drawn from Swedish population registers. The LNU was first conducted in 1968. In 1974, 1981, 1991 and 2000, panel members were followed (to age 75) and new random samples were drawn of populations coming of age for the survey or immigrating to Sweden since the previous survey. In the last two waves the lower age limit was increased to 18 and complete birth and union histories were collected. In the 2000 survey, 5412 individuals were interviewed, producing a response rate of 77 per cent.

We restricted our sample to Swedish-born respondents with only singleton births who did not report an adopted or a deceased child and did not report births less than six months apart. A handful of respondents who did not report the year of each birth were also excluded. In two instances the birth month was missing; we assigned the birth to June. The final analytic sample consisted of 2,985 respondents and 3,197 unions at risk for a second birth and 2,254 respondents and 2,452 unions at risk for a third birth. The LNU did not provide sufficient observations to obtain robust estimates for stepfamily effects on the risk of a fourth or higher-order birth.

We combined union and birth histories in order to assign each birth to the respondent’s union(s) or periods of living alone. In some cases union start- and end-months were reported by quarter rather than month or were missing altogether. We assigned events reported by quarter to the middle month (for example, February for first quarter). Otherwise, our rule depended on the number of union events reported during the year. If only one, we assigned the missing month to June. If two events occurred, we assigned months to equally space unions across possible months. For example, if we knew a union ended in June and the subsequent union began in the same year but was missing a starting month, we assigned the start month of the subsequent union to October, the middle month between the previous union’s end date and the end of the year. In the rare case that two events occur in the same year and both are missing the month, we assigned the events to one-third and two-thirds into the year, i.e. the first event is assigned to April, the second to August.

We assigned month of an event to 776 unions and 432 respondents. Spells after a shared birth are at least twice as likely as spells after stepfamily formation to have an assigned month. Sensitivity analyses (not shown) indicated that spells with assigned months are more likely to produce a second birth, but not a third. Inclusion of the assignment indicator did not change other parameters of our models. We do not, therefore, present models with the assignment indicator.

Children were assigned to a union if they were born within nine months of the union’s end. Children not assigned to previous unions but born within twelve months before a new union were assigned to that union. Only children born more than nine months after a union and more than twelve months before a subsequent union were considered to be born out of any union. This means that when a stepfamily is formed, the youngest stepchild is at least 13 months old. Further, the few stepfamilies in this situation contribute to the risk of a second shared child only from the child’s 13th month. Note that all the respondent’s children were counted whether or not they lived with the respondent and stepparent. Although parents incur greater costs for coresident than nonresident children, differences in their effects on future childbearing are relatively small (Vikat et al. 2004).

Methods

We estimated second- and third-birth risks for respondents who reported, respectively, a first or second birth. For the second birth risk we generated two types of spells: (1) intervals after the first birth in a union without stepchildren; and (2) intervals after a respondent with one child enters a new partnership. For the third birth risk we generated three types of spells: (1) intervals after the second birth in a union without stepchildren; (2) intervals after the first birth in a union with one stepchild; and (3) intervals after a respondent with two children enters a new partnership. Spell types (1) for first births and (1) and (2) for second births begin six months after a birth. The risk of a subsequent live birth is functionally zero during this six-month period. We used six months rather than nine months to allow for preterm births. Spell types (2) for first births and (3) for second births begin with a union. Consequently, for these spells pre-union conceptions were included, even though conceptions may precipitate coresidence. We view the decision to carry a child to term and to live together as part of the commitment value of the child. All spells were censored at union dissolution, interview, and at the end of the childbearing years: age 45 for women and age 50 for men. In total, the 2,985 respondents with a first birth produce 2,275 second births, while the 2,254 respondents with a second birth produce 814 third births.

We modelled the risk of a birth in continuous time using Cox proportional hazards models (Cox 1972; Blossfeld et al. 2006). The duration variable is not parameterized, thus there is no assumption about the underlying relationship between the hazard function and time. The model takes the form

The subscript for an individual is suppressed for simplicity. In this model, h(t) is the hazard rate of a birth for an individual at time t and h0 is the baseline hazard function. Our central interest is the relationship between the union status of prior births and the risk of a subsequent birth (β1 Relationship).

Because the data do not include information on the number of children born to prior partners, we could not estimate a full parity model as in several previous analyses. For example, Thomson and colleagues (2002) controlled for the combined number of children (hers, his, theirs) at the beginning of a union or birth spell and specified stepfamily effects with categories for theoretically relevant types of stepfamilies (with/without shared children; stepchildren of man, woman or both). Thomson (2004) interacted combined parity with the stepfamily status of each child. Lack of information on partners’ children means that some couples identified as not having stepchildren do in fact have stepchildren through the respondent’s partner, and some of the stepfamilies have more stepchildren than we identified through the respondent. If repartnering is random with respect to partners’ children, these differences would cancel each other out. But if parents are more likely to repartner with other parents, we have underestimated the negative effect of combined parity on the risk of stepfamily births. Because the larger combined family size of stepfamilies suppresses the potential for extra births, failure to include children of the partner in our models means that the stepfamily effects may also be underestimated. This is the same limitation faced by Vikat and colleagues (1999) in their previous analysis for Sweden. At this point, no better survey data exist for Sweden and administrative registers cannot identify spells of cohabitation that do not produce common children.

We tested for differences in the pace of childbearing after union formation and after a shared birth by specifying interactions between union type and categories of union duration, (β2 (Relationship * Duration)). We allowed for differential effects among couples with no shared children at union durations of 0 to 24 months, 25 to 36 months, 37 to 60 months, and 61 months or more. This specification captures the differential risk profiles across union types, in particular the expected earlier peak in fertility among unions without shared births.

We controlled for respondent’s sex and age, the latter specified with time-varying linear splines. The spline specification and the particular nodes chosen were based on the estimated AIC and BIC selection criterion from several specifications (continuous, dummy variable, splines with alternative nodes), not shown here. Due to sample size limitations, we were unable to estimate separate models for men and women. We tested for interactions between age and sex of respondent, but including the interaction did not change the main effects nor did it improve the fit of our models. For the first birth in stepfamilies, we included a measure of the age of the youngest stepchild (β6(Relationship * Age of Youngest Child)). Note that this specification assumes that the age of the child at stepfamily formation has a constant proportional effect on the birth risk, even as the child ages further over the period observed; union duration captures the effect of the child’s advancing age and increasing age gap between prospective half siblings. We took into account the period of observation (categorical variables indicating 1950s and 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s) and tested for changes over time in the pace of childbearing after union formation by specifying a three-way interaction, differentiating time periods before and after 1980 (β3(Relationship * Duration * Period)). We tested the full interaction using five ten-year periods, but found that the shift in effects occurred between the 1970s and 1980s. The more detailed interaction was less robust because of a limited number of observations.

Results

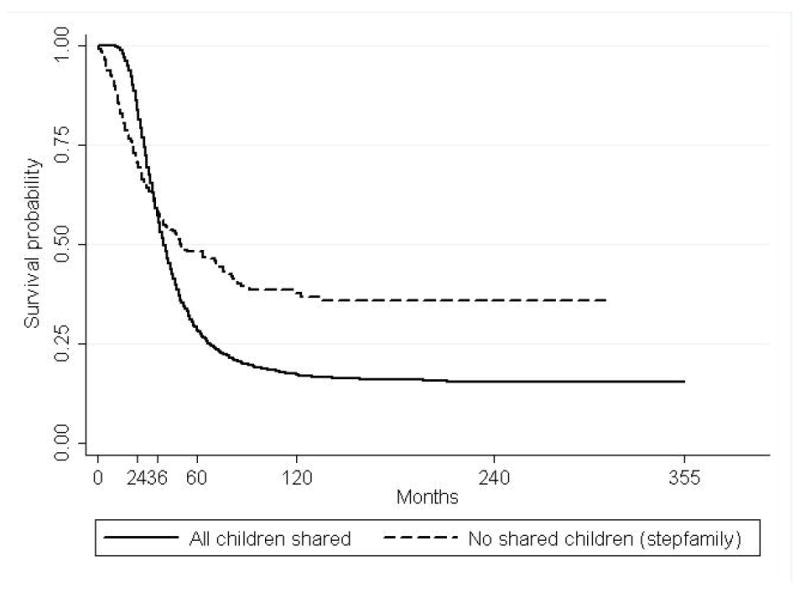

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for spells at risk for a second birth. Spells where the first birth was in the current union are more likely to end in a birth than stepfamily spells (74 per cent and 51 per cent, respectively). This is consistent with the strong preference of Swedish couples for two or more children and suggests that one-child stepfamilies are not at greater risk of having a child because it would be the first in the union. It is also likely due to other differences between stepfamilies and one-child families, differences explored in greater depth in multivariate analyses presented below. Duration also varies by spell type (Figure 1). Approximately one-quarter of spells where the first birth take place in the same union last 24 months or less, 25 to 36 months, 37 to 60 months or 61 months or more. On the other hand, spells beginning with stepfamily formation are both shorter and longer; 38 per cent of spells last 24 months or less, 30 per cent more than 60 months. This suggests a bifurcation of new stepfamily unions—those in which children will be born produce children relatively quickly, while a larger proportion of respondents who form stepfamilies will have no child with the new partner. The sex ratio of respondent is balanced across the two types of spells. In stepfamily spells, respondents are older on average than in spells after a first shared birth. Respondents are over 30 in 71 per cent of stepfamily spells, but only 52 per cent of spells representing the second birth interval in intact unions. Stepfamily spells are differentiated by the age of youngest child at the start of the spell. Almost half of youngest stepchildren are between one and five years old. Spells after a first shared birth are more common in earlier decades relative to spells after stepfamily formation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of spells for the second birth risk in Sweden, 1950-1999

| Number of births in current union |

Total Per cent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| One Per cent | None Per cent | ||

| Proportion of spells | 89.3 | 10.7 | 100.0 |

| Proportion of spells ending in birth | 73.6 | 51.0 | 71.2 |

| Spell duration | |||

| 24 months or less | 21.4 | 38.5 | 23.2 |

| 25 – 36 months | 27.5 | 15.5 | 26.2 |

| 37 – 60 months | 28.3 | 15.7 | 26.9 |

| 61 or more months | 22.8 | 30.3 | 23.6 |

| Female | 52.3 | 52.2 | 52.3 |

| Age | |||

| <25 | 18.4 | 10.6 | 17.5 |

| 25 to <30 | 29.7 | 18.9 | 28.5 |

| 30 to <35 | 22.5 | 19.6 | 22.1 |

| 35+ | 29.4 | 51.0 | 31.9 |

| Age youngest stepchild at spell start | |||

| 13 – 36 months1 | - | 26.9 | - |

| 37 – 60 months | - | 18.5 | - |

| 61 – 120 months | - | 31.8 | - |

| 121 months or more | - | 22.9 | - |

| Historical period | |||

| 1950s, 1960s | 31.4 | 15.2 | 29.6 |

| 1970s | 28.1 | 19.8 | 27.1 |

| 1980s | 23.0 | 34.7 | 24.3 |

| 1990s | 17.5 | 30.3 | 19.0 |

| Number of spells | 2,854 | 343 | 3,197 |

Source: Swedish Level of Living Survey 2000.

Note: Spells for those with no children born in union start at union; spells for couples with a shared birth start six months after the birth.

Children born up to 12 months before a union are counted as shared births.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of the risk of a second birth by family type in Sweden, 1950-1999

Source: As for Table 1

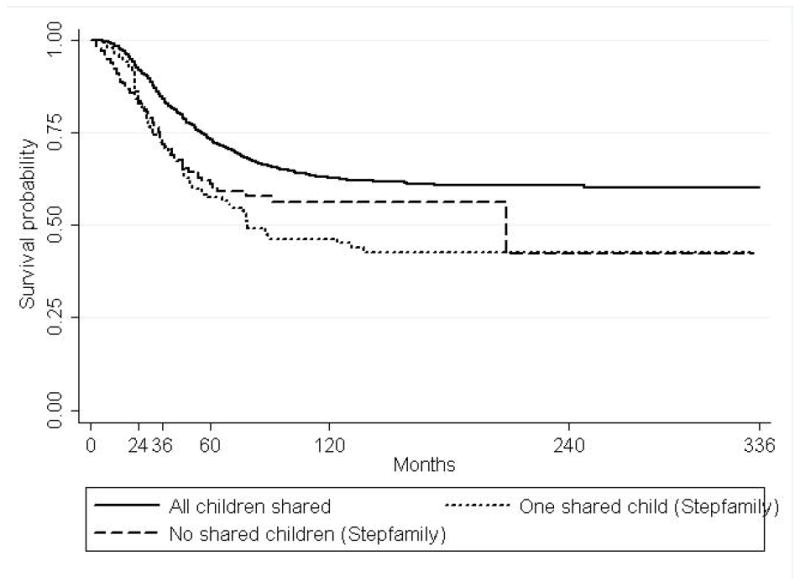

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for spells at risk for a third birth. For third birth risk, spells can be divided into three types spells in which both the first and second children are born in the current union (84 per cent); spells where the second birth occurs in the current union but the first birth occurred before the current union (7 per cent); and spells where all children are born before the current union (9 per cent). Both the second and third types of spell are considered stepfamily spells, but only in the third type is union duration the underlying clock. Spells where the previous birth was in the current union but the first birth before the union are most likely to end in a birth (46 per cent), while approximately 30 per cent of spells with both of the children or none of the children born in the current union end in births. Again, these simple results seem contrary to the hypothesis that stepfamily couples without shared children are especially likely to have a child. However, underlying differences between types of families could drive these findings. Spells following the second birth in a union are the longest, 63 per cent lasting more than 60 months (Figure 2), likely driven by the majority of two-child parents who will not have a third. Among stepfamily spells following the first shared birth, 46 per cent last more than 60 months, again likely consisting mostly of those who will never have a second shared child. Among spells following stepfamily formation (both children born before the union), duration is more equally distributed; as for second births to couples with one stepchild, there appears to be a bifurcation of stepfamilies—those who will have a child relatively quickly and those who will have no shared child at all.

Table 2.

Characteristics of spells for the third birth risk in Sweden, 1950-1999

| Number of births in current union |

Total Per cent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two Per cent | One Per cent | None Per cent | ||

| Proportion of spells | 84.0 | 6.8 | 9.2 | 100.0 |

| Proportion of spells ending in birth | 32.4 | 45.5 | 31.1 | 33.2 |

| Spell duration | ||||

| 24 months or less | 8.8 | 14.4 | 34.7 | 11.6 |

| 25 – 36 months | 11.0 | 21.6 | 18.2 | 12.4 |

| 37 – 60 months | 17.4 | 18.6 | 18.2 | 17.5 |

| 61 or more months | 62.8 | 45.5 | 28.9 | 58.5 |

| Female | 52.0 | 58.1 | 56.4 | 52.9 |

| Age | ||||

| <25 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 1.6 | 3.5 |

| 25 to <30 | 16.6 | 21.9 | 6.0 | 16.4 |

| 30 to <35 | 26.7 | 26.8 | 19.6 | 26.4 |

| 35+ | 53.4 | 44.2 | 72.8 | 53.7 |

| Age youngest stepchild at spell start | ||||

| 13 – 36 months1 | - | - | 15.0 | - |

| 37 – 60 months | - | - | 16.1 | - |

| 61 – 120 months | - | - | 32.1 | - |

| 121 months or more | - | - | 36.8 | - |

| Historical period | ||||

| 1950s, 1960s | 17.4 | 17.0 | 5.7 | 16.9 |

| 1970s | 27.7 | 31.0 | 16.9 | 27.4 |

| 1980s | 31.2 | 31.4 | 40.2 | 31.6 |

| 1990s | 23.7 | 20.5 | 37.2 | 24.1 |

| Number of spells | 2,060 | 167 | 225 | 2,452 |

Source: As for Table 1.

Note: Spells for those with no children born in union start at union; spells for couples with a shared birth start six months after the birth.

Children born up to 12 months before a union are counted as shared births.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier survival estimates of the risk of a third birth by family type in Sweden, 1950-1999

Source: As for Table 1

Women contribute a marginally higher proportion of stepfamily spells with either one or no children born in the current union. Differences attributable to the respondent’s sex likely arise from differences in assortative mating patterns among men and women. Respondents are older in stepfamily spells begun with two children rather than one, or spells begun with a second shared birth. When spells begin with a union, the younger stepchild tends to be older on average than in the case of second birth risks, only 31 per cent of youngest stepchildren being under age five. Finally, about 45 per cent of spells following a birth—whether the first (with a stepchild) or second in a union—were observed before 1980 while 77 per cent of spells beginning with union formation—after the birth of two children to the respondent—are observed after 1980.

Estimates for the risk of a second lifetime birth are presented in Table 3. Model 1 estimates the differential in the birth risk between those entering a stepfamily with one child and those having had their first child in the same union. Consistent with data in Table 1, the estimated birth risk is lower in stepfamilies than for couples with one shared child. Controlling for characteristics associated with stepfamilies and for the age of the youngest stepchild (Model 2), the estimated birth risk for stepfamilies is no different from that for a second shared birth to couples without stepchildren. That is, births may be inhibited by the fact that couples in new stepfamilies are older and they may have school-age or teen-age children. Net of those differences, they are equally likely to produce a second child for the respondent as couples whose first birth was shared. Keep in mind that the estimated relative birth risks for stepfamily couples with one stepchild and no shared children and couples with one shared child depends on the assumption that the pace of childbearing is the same for couples that just formed a stepfamily union or just experienced a first shared birth.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard models predicting the risk of a second birth in Sweden, 1950-1999: hazard ratios (confidence intervals)

| Model 1 (hazard ratios) | Model 2 (hazard ratios) | Model 3 (hazard ratios) | Model 4 (hazard ratios) | Model 5 (hazard ratios) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship characteristics (time varying) | |||||

| 1st birth in union | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1st birth before union | 0.64 *** (0.54 – 0.76) | 0.92 (0.70 – 1.21) | - | - | - |

| Duration 0 – 24 months | - | - | 1.05 (0.84 – 1.31) | 1.45 ** (1.10 – 1.93) | 1.84 *** (1.32 – 2.55) |

| Duration 25 – 36 months | - | - | 0.48 *** (0.34 – 0.68) | 0.69 + (0.46 – 1.02) | 0.88 (0.55 – 1.41) |

| Duration 37 – 60 months | - | - | 0.33 *** (0.22 – 0.49) | 0.47 *** (0.30 – 0.73) | 0.77 (0.44 – 1.36) |

| Duration 61 or more months | - | - | 0.59 * (0.37 – 0.92) | 0.84 (0.50 – 1.39) | 1.17 (0.58 – 2.36) |

| 1st birth before union * period | - | - | - | - | - |

| Duration 0 – 24 months, 1980+ | - | - | - | - | 0.47 *** (0.29 – 0.73) |

| Duration 25 – 36 months, 1980’s-1990’s | - | - | - | - | 0.47 * (0.23 – 0.92) |

| Duration 37 – 60 months, 1980’s-1990’s | - | - | - | - | 0.29 ** (0.13 – 0.66) |

| Duration 61 or more months, 1980’s-1990’s | - | - | - | - | 0.46 + (0.19 – 1.11) |

| Female | - | 0.91 * (0.84 – 0.99) | - | 0.91 * (0.84 – 0.99) | 0.91 * (0.83 – 0.99) |

| Age (time-varying, slopes) | |||||

| <25 | - | 1.01 (0.97 – 1.05) | - | 1.01 (0.96 – 1.05) | 1.01 (0.97 – 1.05) |

| 25 to <30 | - | 0.98 (0.95 – 1.01) | - | 0.98 (0.95 – 1.01) | 0.98 + (0.95 – 1.00) |

| 30 to <35 | - | 0.95 ** (0.91 – 0.98) | - | 0.95 ** (0.91 – 0.98) | 0.95 ** (0.91 – 0.98) |

| 35+ | - | 0.80 *** (0.76 – 0.85) | - | 0.81 *** (0.76 – 0.85) | 0.81 *** (0.77 – 0.85) |

| Age of youngest stepchild | |||||

| 13 – 36 months1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| 37 – 60 months | - | 0.93 (0.60 – 1.43) | - | 0.96 (0.65 – 1.43) | 1.15 (0.78 – 1.70) |

| 61 – 120 months | - | 0.74 (0.48 – 1.13) | - | 0.75 (0.50 – 1.11) | 0.97 (0.64 – 1.48) |

| 121 months or more | - | 0.45 * (0.22 – 0.92) | - | 0.45 * (0.23 – 0.91) | 0.56 + (0.29 – 1.08) |

| Historical period (time-varying) | |||||

| 1950s, 1960s | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| 1970s | - | 1.05 (0.95 – 1.17) | - | 1.05 (0.94 – 1.17) | 1.04 (0.93 – 1.15) |

| 1980s | - | 1.43 *** (1.27 – 1.61) | - | 1.45 *** (1.29 – 1.63) | 1.53 *** (1.36 – 1.73) |

| 1990s | - | 1.49 *** (1.32 – 1.69) | - | 1.50 *** (1.32 – 1.69) | 1.58 *** (1.40 – 1.79) |

| Log likelihood | -16726.41 | -16569.31 | -16709.27 | -16553.06 | -16539.92 |

| AIC | 33454.81 | 33162.63 | 33426.54 | 33136.12 | 33117.84 |

| BIC | 33464.81 | 33282.66 | 33466.54 | 33286.16 | 33307.88 |

| df | 1 | 12 | 4 | 15 | 19 |

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

N individuals = 2,985; N unions = 3,197; N events = 2280.

Children born up to 12 months before a union are counted as shared births.

Source: As for Table 1.

In Model 3, we relax the assumption of common duration dependence by distinguishing the stepfamily difference at different durations. During the first 24 months of a stepfamily union, the risk of a birth is as high as during the first 6 to 30 months of a shared child’s life. Thereafter, the birth risk for stepfamilies is half the risk for couples whose child is 31 months old and above. Again, in the model with control variables, the stepfamily birth risk is 1.5 times as high during the first 24 months of observation, but after 24 months, the differential reverses with lower second birth risks in stepfamilies.

Note that in both Models 2 and 4 the risk of second births was greater in the 1980s and 1990s than in previous decades. The increase is consistent with the introduction of a ‘speed premium’ in parental leave formalized in 1980 and the resulting decrease in second birth intervals and increase in second births overall (Hoem 1993; Andersson 2004). As noted above, the speed premium would not likely influence birth risks in stepfamilies because by the time a stepfamily is formed, the first child would be too old for the mother or father to claim the premium. Thus, we might expect differences in the birth risk to be reduced in later periods when strong incentives existed for short birth intervals among couples with shared children. In Model 5 we present results in which period (before 1980, 1980, and later) interacts with the duration-specific stepfamily parameters. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, the birth risk for stepfamilies during the first 24 months of their union was 1.8 times that of the risk for couples with a child under 30 months; the differential was reduced to about 0.85 (1.84 × 0.47) for the 1980s and 1990s. Between 24 and 36 months, stepfamilies were equally likely to have a child as were couples with a child 30 and 42 months old in the earlier period, but half as likely during the later period. Similar patterns are found for the relative risks at later durations (Table 4), providing clear support for Hypothesis 4.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard models predicting the risk of a second birth in Sweden, 1950-1999 (Model 5)

| Months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-24 (hazard ratios) | 25-36 (hazard ratios) | 37-60 (hazard ratios) | 61+ (hazard ratios) | |

| One Shared Birth | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No Shared Births | ||||

| Pre-1980 | 1.84 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 1.17 |

| Post-1980 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.54 |

N individuals = 2,985; N unions = 3,197; N events = 2280.

Note: Model (5) includes indicators for female, age, age of youngest stepchild and period.

Source: As for Table 1.

Table 5 presents models for the risk of a third lifetime birth. In Model 1, we find higher birth risks for stepfamily couples, whether they have no child or one child together. Controlling for parental age, sex, age of youngest child, and period (Model 2), the higher risk of a third birth remains. All of these estimates, however, depend on the assumption that the baseline hazard is the same for new stepfamilies as for couples after a shared birth. Model 3 relaxes that assumption by specifying an interaction between stepfamily status (new stepfamily versus other couples) and the period of observation. The model does not specify an interaction with duration for stepfamily couples with one shared child because the baseline hazard after that child’s birth is virtually identical to the hazard for couples who have had a second child together (See also: Henz 2002; Li 2006). As for second births, the risk of a first birth is particularly high for couples with no shared children during the first 24 months of their union. It drops to the level of couples with one shared child during the succeeding year and is essentially the same as that for couples with two shared children after three years of observation.

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazard models predicting the risk of a third birth in Sweden, 1950-1999: hazard ratios (confidence intervals)

| Model 1 (hazard ratios) | Model 2 (hazard ratios) | Model 3 (hazard ratios) | Model 4 (hazard ratios) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship characteristics (time varying) | ||||

| Same union 1st, 2nd birth | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Same union 2nd birth; 1st birth before union | 1.76 *** (1.39 – 2.24) | 1.73 *** (1.35 – 2.22) | 1.77 *** (1.39 –2.25) | 1.73 *** (1.35 – 2.22) |

| 1st, 2nd birth before union | 1.58 *** (1.21 – 2.06) | 2.80 *** (1.78 – 4.40) | - | - |

| Duration 0 – 24 months | - | - | 2.37 *** (1.63 – 3.44) | 3.90 *** (2.46 – 6.19) |

| Duration 25 – 36 months | - | - | 1.60 + (0.98 – 2.59) | 2.89 *** (1.58 – 5.30) |

| Duration 37 – 60 months | - | - | 1.15 (0.67 – 1.99) | 2.42 ** (1.27 – 4.62) |

| Duration 61 or more months | - | - | 0.74 (0.31 – 1.79) | 1.34 (0.54 – 3.32) |

| Female | - | 0.72 *** (0.63 – 0.83) | - | 0.72 *** (0.63 – 0.83) |

| Age (time-varying, slopes) | ||||

| <25 | - | 0.89 (0.78 – 1.03) | - | 0.89 (0.78 – 1.03) |

| 25 to <30 | - | 1.00 (0.95 – 1.07) | - | 1.00 (0.94 – 1.06) |

| 30 to <35 | - | 0.89 *** (0.85 – 0.94) | - | 0.89 *** (0.85 – 0.94) |

| 35+ | - | 0.82 *** (0.77 – 0.86) | - | 0.82 *** (0.78 – 0.87) |

| Age of youngest stepchild | ||||

| 13 – 36 months1 | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| 37 – 60 months | - | 0.77 (0.37 – 1.62) | - | 0.76 (0.38 – 1.50) |

| 61 – 120 months | - | 1.93 * (1.03 – 3.62) | - | 1.83 * (1.04 – 3.23) |

| 121 months or more | - | 0.57 * (0.21 – 1.54) | - | 0.54 (0.21 – 1.41) |

| Historical period (time-varying) | ||||

| 1950s, 1960s | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| 1970s | - | 0.62 *** (0.51 – 0.75) | - | 0.62 *** (0.51 – 0.75) |

| 1980s | - | 1.00 (0.83 – 1.20) | - | 1.00 (0.83 – 1.20) |

| 1990s | - | 0.84 (0.67 – 1.04) | - | 0.84 (0.68 – 1.04) |

| Log likelihood | -6043.76 | -5928.50 | -6039.09 | -5925.29 |

| AIC | 12091.52 | 11883.00 | 12088.19 | 11882.58 |

| BIC | 12112.32 | 12018.17 | 12140.18 | 12048.96 |

| df | 2 | 13 | 5 | 16 |

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

N individuals = 2,254; N unions = 2,452; N events = 820.

Children born up to 12 months before a union are counted as shared births.

Source: As for Table 1.

When we add additional covariates, we find that the relative risk of childbearing for new stepfamilies increases, especially during the first 24 months. That is, net of their older age and older stepchildren, couples forming a new stepfamily are especially likely to have a shared child early in the union. We also tested the interaction between the two types of stepfamilies and period but found no significant differences. That is, the extra third births produced by stepfamilies in the first five years of their union, were as common in the later as in the earlier period.

Conclusions

Our results are consistent with previous research on stepfamily childbearing in Sweden and many other countries. We found an increased birth risk when the prospective child is the first or second shared child, demonstrating the commitment and sibling values of such births (Hypotheses 1 and 2). Consistent with hypothesis three, the stepfamily differential is greater for third births than second births, in large part due to the very high proportion of one-child couples that have a second child together. The stepfamily differential is, however, conditioned upon the pace of childbearing, as well as other underlying clocks, age of parent and age of youngest stepchild. Consistent with previous work (Henz 2002; Li 2006), we found a faster pace of childbearing after stepfamily formation than after a shared birth. After two years, the birth risk for new stepfamilies is only somewhat lower than that for couples with a shared child. Keep in mind that these differences are net of the negative influence of parental and stepchild’s ages for the new stepfamilies. They are theoretically relevant for understanding stepfamily lives but do not necessarily imply that separation and repartnering will produce more children than stable unions.

We found a similar increased pace of childbearing for stepfamilies with no shared children at risk for a third lifetime birth. When we disaggregated these spells by duration and included covariates, we found that the risk of a third birth is particularly high early in the stepfamily union and remains higher than that for couples with two shared children for at least five years. The differences again reinforce the commitment value of a first shared child, and effects are stronger than for second births (Hypothesis 3) due to the relatively low likelihood of third births in stable childbearing unions.

Henz (2002) suggested that childbearing shortly after the formation of a stepfamily union indicates that union formation is endogenous to the couple’s decision to have children together. This does not negate, but is in fact consistent with the concept of commitment value. As couples—with or without stepchildren—move their relationship toward cohabitation or marriage, they are also likely to be deciding about having a shared child as part of the commitment process. Whether they conceive shortly before or shortly after union formation, the underlying motivation is the same: a future together and, net of the costs associated with higher parity, another child.

Our findings are consistent with arguments that union instability works to maintain relatively high (just below or at replacement) fertility through the extra children that are born in stepfamilies, especially the extra third births. Working in the opposite direction is the fact that birth risks are very low among persons not in a coresident union, i.e., during the partner search, and not everyone finds a new partner. Repartnering should increase aggregate fertility, but may not fully compensate for the negative effects of union disruption (Thomson et al. forthcoming).

Our results highlight the importance of disaggregating the multiple clocks underlying birth risks in different types of partnerships and at different points in the life course. As expected, we found that the risk of a birth is inversely related to the age of the parents. Age of youngest child operates independently of union duration for families with no shared births, generally reducing the risk of both a second and third birth. Second and third birth risks drop substantially once the youngest child is at least ten years old; the potential age gap between a new child and the youngest child is large enough that the two children would not identify as (half-)siblings and the couple would effectively be “starting over” with respect to childbearing. For third births, we found an elevated risk when the youngest child is between six and ten years old. When the youngest child is less than six years old, it is likely that there are two relatively young children who must be incorporated into a new partnership; having a baby right away may be too costly in terms of time, energy, and emotional work. Those who enter new partnerships with older children (where the youngest is aged six to ten) may find a new baby to be more manageable.

Finally, we were able to estimate risks of stepfamily and continuous family births across a longer time period than in previous studies. We identified a change in the relationship between union type and risks for second births. Before 1980 we observed a dramatically increased risk for a stepfamily birth in the first 24 months of the union relative to the risk after a first shared birth. After 1980, the magnitude of this difference is greatly reduced. At longer durations, the birth risk in new stepfamilies is half that experienced in stable unions, while the two risks were equal before 1980. This finding is consistent with the introduction of a “speed premium” in Sweden, allowing parents to receive a higher level of leave compensation if they more closely spaced the birth of their children. The calculus of birth timing for couples with one shared child was altered, while that for most new stepfamilies was not. It is notable, however, that despite the increased pace of fertility after a shared birth, new stepfamilies continued to have a higher birth risk during the first two years of the union, consistent with the commitment value of a shared child.

We expect that our estimates of the commitment value of a first shared birth to stepfamily couples are conservative because we were unable to take into account the children of previous partners. Some stepfamilies may have been wrongly categorized as families where all children are shared, thus somewhat diminishing the difference in birth risk after the first or second shared births and births to new stepfamilies or stepfamilies with one shared child. But we may also have classified some stepfamilies with fewer stepchildren than they actually had, i.e., who would have been at risk of having a third rather than a second, a fourth rather than a third child if both partners’ children had been taken into account. The couple’s combined number of children exerts downward pressure on childbearing and thus suppresses the stepfamily effect. If we had been able to control for the couple’s combined number of shared and stepchildren, there would be stronger evidence for the meaning of first and second births in stepfamilies as well as for other couples.

Footnotes

Jennifer Holland is a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, a guest researcher at Statistics Norway, and an international collaborator with the Linnaeus Center for Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe, Stockholm University. Elizabeth Thomson is Professor of Demography, Department of Sociology, Stockholm University, and Professor Emerita, Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison. She directs the Stockholm University Demography Unit and the Linnaeus Center for Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe. Direct all correspondence to Jennifer Holland, Center for Demography and Ecology, Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA or to jholland@ssc.wisc.edu.

Earlier versions of the paper and some analyses have been presented and benefited from discussions at meetings of the Population Association of America (2009), the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (2009), the Nordic Demographic Symposium (2008), University of Wisconsin—Madison’s Center for German and European Studies, and the Stockholm University Demography Unit and Linnaeus Center for Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe. Support for the research was provided by the Swedish Research Council, Stockholm University, and the University of Wisconsin—Madison’s Center for Demography and Ecology (Center Grant R24 HD047873 and NICHD Training Grant T32 HD07014). We also thank the Swedish Institute for Social Research for access to and documentation of the Swedish Level of Living Survey.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Holland, University of Wisconsin—Madison

Elizabeth Thomson, Stockholm University and University of Wisconsin—Madison.

References

- Andersson Gunnar. Children’s experience of family disruption and family formation: evidence from 16 FFS countries. Demographic Research. 2002;7(7):343–364. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson Gunnar. Childbearing developments in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden from the 1970s to the 1990s: a comparison. Demographic Research. 2004;S3(7):155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Baizán Pau, Aassve Arnstein, Billari Francesco C. Cohabitation, marriage, first birth: the interrelationship of family formation events in Spain. European Journal of Population. 2003;19:147–69. [Google Scholar]

- Baizán Pau, Aassve Arnstein, Billari Francesco C. The interrelations between cohabitation, marriage and first birth in Germany and Sweden. Population and Environment. 2004;25(6):531–61. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld Hans-Peter, Golsch Katrin, Rohwer Götz. Event History Analysis with Stata. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cox David R. Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1972;34(2):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith Janet D, Koo Helen P, Suchindran CM. Childbearing and family in remarriage. Demography. 1985;22(1):73–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henz Ursula. Childbirth in East and West German stepfamilies: estimated probabilities from hazard rate models. Demographic Research. 2002;7(6):307–42. [Google Scholar]

- Henz Ursula, Thomson Elizabeth. Union stability and stepfamily fertility in Austria, Finland, France & West Germany. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie. 2005;21(1):3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem Jan M. Public policy as the fuel of fertility: effects of a policy reform on the pace of childbearing in Sweden in the 1980s. Acta Sociologica. 1993;36(1):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe Ron, van de Kaa Dirk J. Twee demografishe transities? [Two demographic transitions?] In: Lesthaeghe R, v d Kaa DJ, editors. Bevolking: Groei en Krimp [Population: Growth and Decline] Deventer: Van Loghum Slaterus; 1986. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Li Jui-Chung Allen. The institutionalization and pace of fertility in American stepfamilies. Demographic Research. 2006;14(12):237–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard Lee, Panis Constantijn WA. aML Multilevel Multiprocess Statistical Software, Version 2.0. Los Angeles: EconWare; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka Tomáš, Toulemon Laurent. Changing family and partnership behaviour. common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demographic Research. 2008;19(6):85–138. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth. Step-families and childbearing desires in Europe. Demographic Research. 2004;S3(5):117–34. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth, Hoem Jan M, Vikat Andres, Buber Isabella, Fuernkranz-Prskawetz Alexia, Toulemon Laurent, Henz Ursula, Godecker Amy L, Kantorova Vladimira. Childbearing in stepfamilies: whose parity counts? In: Klijzing E, Corijn M, editors. Fertility and Partnership in Europe: Findings and Lessons from Comparative Research Volume II. Geneva/New York: United Nations; 2002. pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth, Li Jui-Chung Allen. NSFH Working Paper. Madison, WI: Center for Demography and Ecology; 2002. Her, his and their children: childbearing intentions and births in stepfamilies. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth, Winkler-Dworak Maria, Spielauer Martin, Prskawetz Alexia. Union instability as an engine of fertility? A micro-simulation model for France. Demography. Forthcoming doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0085-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikat Andres, Thomson Elizabeth, Hoem Jan M. Stepfamily fertility in contemporary Sweden: the impact of childbearing before the current union. Population Studies. 1999;53(2):211–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vikat Andres, Thomson Elizabeth, Prskawetz Alexia. Childrearing responsibility and stepfamily fertility in Finland and Austria. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie. 2004;20(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]