Abstract

Constipation is a common ailment with multiple symptoms and diverse etiology. Understanding the pathophysiology is important to guide optimal management. During the past few years, there have been remarkable developments in the diagnosis of constipation and defecation disorders. Several innovative manometric, neurophysiologic, and radiologic techniques have been discovered, which have improved the accuracy of identifying the neuromuscular mechanisms of chronic constipation. These include use of digital rectal examination, Bristol stool scale, colonic scintigraphy, wireless motility capsule for assessment of colonic and whole gut transit, high resolution anorectal manometry, and colonic manometry. These tests provide a better definition of the underlying mechanism(s), which in turn can lead to improved management of this condition. In this review, we summarize the recent advances in diagnostic testing with a particular emphasis on when and why to test, and discuss the utility of diagnostic tests for chronic constipation.

Keywords: Constipation, Diagnostic Tests, Rectal Exam, Colon Transit, Anorectal Manometry, Colonic manometry

Introduction

Constipation is a symptom based disorder that is caused by multiple mechanisms. Primary constipation involves three pathophysiologic subtypes [1, 2]. Slow Transit Constipation is characterized by prolonged delay of stool transit through the colon. Dyssynergic Defecation is characterized by either difficulty or inability to evacuate stool from the rectum. Constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome is characterized by symptoms of constipation with discomfort or pain as a prominent feature [3]. Secondary constipation is caused by a myriad of factors such as diet, drugs, behavioral, lifestyle, endocrine, metabolic, neurological, psychiatric, and other disorders [4]

Although a diagnosis of constipation is usually made on the basis of symptoms, a more precise and accurate characterization of the underlying mechanism(s) requires physiologic tests of colorectal function especially in patients who are not responding to simple measures such as fiber supplements and over the counter laxatives [5].

In this review, we discuss the role of diagnostic tests for constipation and when to order these tests and what do they provide.

Clinical Evaluation

History

A detailed medical, surgical, dietary and drug history can facilitate the recognition of common constipation.(Table 1) Patients and physicians have a different perception regarding the symptoms as constipation [6]. Hence, consensus criteria have been proposed by experts to improve the diagnosis of constipation such as the Rome III Criteria for constipation [3, 7] and the American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. The latter recommends a broader definition of unsatisfactory defecation characterized by infrequent stools, difficult stool passage, or both as constipation [8]. The Rome III Criteria for functional constipation include any two of the six symptoms of straining, lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage, digital maneuvers and less than 3 defecations per week. These should be present during at least 25% of defecations for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before the diagnosis [4].

Table 1. Components of history that are useful in evaluating a patient with constipation.

| Details of history |

|---|

| Description of subjects bowel habits |

| Onset of symptom |

| Duration of symptom |

| Severity of symptoms |

| History of precipitating events |

| Laxative use – type, number and frequency |

| Dietary history-fiber and fluid intake |

| Family history of bowel function |

Patients should be encouraged to describe their bowel habit such as, do they experience an urge to defecate, or feel or sense complete evacuation, if they need to strain or use digital maneuvers, or describe their stool consistency and stool size using the Bristol Stool Scale, or if they ignore a call to stool, or if there are any precipitating events and how their cultural beliefs and expectations affect their bowel patterns, and whether the problem started in childhood. Stool diaries and constipation questionnaires can help discern some of these symptoms, especially as patients misinterpret or feel embarrassed to describe them [9, 10].

Studies in constipated subjects showed a history of sexual abuse in 22% - 48% of subjects, particularly women and physical abuse was reported by 31% - 74% of constipated subjects. [4,10]. Hence it is important to gently elicit these components in the history.

A history of recurring problems for a long duration which is not relieved with dietary measures or laxatives suggests a functional colorectal disorder, where as a recent history of alarm symptoms like rectal bleeding, anemia, guaiac-positive stool or mass in the abdomen should prompt an enquiry to exclude organic illness and neoplastic disease.

Symptom and Stool Diary

Symptom assessment should be combined with clinical testing for optimal assessment of these patients [11,12,13]. The Bristol Stool Form Scale helps patients and physicians to identify their stool form and can be useful to assess colonic transit time because very loose or hard stools correlate with either rapid or slow colonic transit [14-16]. In patients with co-existing psychological issues, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) and Patient Assessment Constipation-Quality of Life (PAC-QOL) are also commonly used[17,18].

A food diary can be helpful to assess fiber and fluid intake and the number, frequency and nutrient content of meals. Failure to respond to the physiological urge to defecate after waking and after a meal may predispose to constipation. In the elderly, fecal incontinence may be a presenting feature of constipation [11], and therefore this group should be carefully evaluated for stool impaction. Also some children with functional fecal retention and soiling may have persistent leakage because of underlying dyssynergia [19].

Physical Examination

A comprehensive physical examination including a detailed neurological examination can help to recognize systemic diseases that may cause constipation. The abdomen must be carefully examined for the presence of stool, particularly in the left quadrant. It is important to exclude a gastrointestinal mass although, patients may commonly have a normal physical examination.

Digital Rectal Examination

A careful perianal and digital rectal examination is very important, as in many instances it is the most revealing part of clinical evaluation[20,21]. Abnormalities such as thrombosed external hemorrhoids, skin tags, rectal prolapse, anal fissure, anal warts, excoriation or evidence of pruritus ani usually from fecal soiling can be easily appreciated on anorectal inspection. Watching the perineum while the patient strains may show leakage of stool, a gaping anus or prolapse of internal hemorrhoids. If there is excruciating pain on starting the digital rectal exam, it strongly suggests the presence of an anal fissure. It is important to assess the resting sphincter tone which is predominantly (70-80%) attributable to the internal anal sphincter muscle. A high resting tone may be the cause of evacuation disorder [22]. Palpation of the rectal walls may help to identify polyps or masses and determine if there is a rectocele or intussusception. The presence of stool in the vault, its consistency and patient's awareness of it should be noted. A lack of awareness of stool may suggest rectal hyposensitivity.

The patient should be asked to push and bear down as if to defecate. Normally, the anal sphincter and puborectalis should relax and the perineum should descend. If the muscles paradoxically contract or if there is no perineal descent, this suggests pelvic floor dyssynergia. A hand should be placed over the abdomen to assess the push effort. Perineal descent assessed by examination correlates with descent assessed by dynamic MRI [23]. DRE can detect anismus and anterior rectocele and has high positive predictive value (95%) for obstructive defecation [24]. A carefully performed DRE has a high yield of detecting dyssynergia in patients with chronic constipation [22]. Of the 187 patients with a diagnosis of dyssynergia based on standard criteria, 134 patients were identified as having features of dyssynergia based on DRE giving a positive predictive value of 97%. The sensitivity and specificity of DRE for identifying patients with chronic constipation were 75% and 87% respectively. DRE was able to identify normal resting and normal squeeze pressure in 86% and 82% of dyssynergic patients respectively.

In a survey only 40% of final year medical students felt confident in rendering an opinion based on their DRE findings [25] and only 20% had performed more than10 procedures [26]. A recent multicenter study involving medical students, primary care and internal medicine physicians and gastroenterologists showed that gastroenterologists performed the most DREs annually, followed by primary care, and internal medicine subspecialities [27]. Since symptoms alone are poor predictors of underlying pathology of chronic constipation [12], symptoms together with DRE findings may help identify patients who may require further specialized testing for evaluation and management. Table 2 summarizes the main components of the Digital Rectal Examination.

Table 2. Components of Digital Rectal Exam (Reproduced with permission from (22).

| Exam Component | Technique | Findings & Grading of response(s) |

|---|---|---|

| I. Inspection of the anus and surrounding tissue | Place patient in the left lateral position with hips flexed to 90°. Inspect perineum under good light | Skin excoriation, skin tags, anal fissure, scars or hemorrhoids |

| II. Testing of perineal sensation and the anocutaneous reflex | Stroke the skin around the anus in a centripetal fashion, in all four quadrants, by using a stick with a cotton bud |

Normal: brisk contraction of the perianal skin, the anoderm and the external anal sphincter Impaired: no response with the soft cotton bud, but anal contractile response seen with the opposite (wooden) end Absent: no response with either end |

| III. Digital palpation and maneuvers to assess anorectal function | ||

| Digital palpation | Slowly advance a lubricated and gloved index finger into the rectum and feel the mucosa and surrounding muscle, bone, uterus, prostate and pelvic structures | Tenderness, mass, stricture, or stool and the consistency of the stool |

| Resting tone | Assess strength of resting sphincter tone | Normal, weak (decreased) or increased |

| Squeeze maneuver | Ask the patient to squeeze and hold as long as possible (up to 30 seconds) | Normal, weak (decreased) or increased |

| Pushing and bearing down maneuver | In addition to the finger in the rectum, place a hand over the patients' abdomen to assess the push effort. Ask the patient to push and bear down as if to defecate | (i) Push effort: Normal, weak (decreased), excessive (ii) Anal relaxation: normal, impaired, paradoxical contraction (iii) Perineal descent: Normal, excessive, absent |

Diagnostic Tests

A complete blood count, biochemical profile, serum calcium, glucose levels and thyroid function tests are usually sufficient for screening purposes to exclude an underlying metabolic or pathological disorder. If there is a high index of suspicion, serum protein electrophoresis, urine porphyrins, serum parathyroid hormone and serum cortisol levels may be requested. However there are no studies done to assess the clinical value of the routine use of blood tests alone and hence there is no evidence to either support or reject the utility of these tests [5]. The American College of Gastroenterology Task Force does not routinely recommend these tests in patients younger than 50 years of age and in whom there are no alarm features or signs of organic disease [28]. Alarm features include new onset or progressively worsening constipation, onset after age 50 years, bloody stools, weight loss, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting or a family history of inflammatory bowel disease or colon cancer[8]. A list of commonly performed diagnostic tests, their clinical utility and evidence-based recommendations are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Evidence-based summary of the utility of the diagnostic tests for chronic constipation(Modified from Ref (81).

| Test | Clinical Utility | Evidence | Recommendation | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strength | Weakness | (Grade) | |||

| Blood tests (thyroid, calcium, glucose, electrolytes) | Rule out metabolic disorder | Not cost-effective | No evidence | C | Not recommended routinely without alarm features |

| Imaging tests Plain abdominal X-Ray | Identify excessive amount of stool in the colon, simple, inexpensive, widely available | Lack of standardization and controlled studies | Poor | C | None |

| Barium enema | Identify megacolon, megarectum, stenosis, diverticulosis, masses | Lack of standardization, Radiation exposure. Lack of controlled studies |

Poor | C | Not recommended for routine evaluation without alarm features |

| Defecography | Identify dyssynergia, rectocele, prolapse, excessive descent, megarectum, Hirschsprung disease | Radiation exposure, embarrassment, interobserver bias, inconsistent methodology | Fair | B3 | Used as adjunct |

| Anorectal ultrasound | Visualization of the internal anal | Interobserver bias, availability. | Poor | C | Experimental |

| MRI | Simultaneously evaluate global pelvic floor anatomy, sphincter morphology and dynamic motion | Expensive, lack of standardization, availability | Fair | B3 | Used as adjunct to anorectal manometry |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy | Visualization of mucosal disease | Invasive, risks of procedure and sedation | Poor | C | Lack of prospective study regarding efficacy |

| Physiologic testing Colonic transit with radiopaque markers | Evaluate colon transit, inexpensive and widely available | Inconsistent methodology | Good | B2 | Useful to identify slow transit constipation |

| Colonic transit with scintigraphy | Evaluate slow, normal or rapid colonic transit. | Expensive, time consuming, availability, lack of standardization | Good | B2 | Facilitates classification of pathophysiological subtypes |

| Wireless Motility Capsule | Standardized evaluation of slow, normal or rapid colonic and upper gastrointestinal transit No Radiation, Validated technique | Availability | Excellent | A1 | Reliably identifies slow transit constipation and upper gut transit abnormalities |

| Anorectal Manometry | Identify dyssynergic defecation, rectal hyposensitivity, & hypersensitivity, impaired compliance, | Lack of standardization | Good | B2 | Facilitates diagnoses of dyssynergic defecation, Rectal sensory problems and Hirschsprung's disease |

| Balloon expulsion test (BET) | Bedside assessment of dyssynergic defecation | Lack of standardization | Good | B2 | Normal BET does not exclude dyssynergia. |

| Colonic manometry | Identify colonic myopathy, neuropathy Facilitates selection of patients for surgery Reproducible Clinically useful | Invasive, not widely available, lack of standardization | Good | B2 | Adjunct to colorectal function tests |

Grade A1: Excellent evidence in favor of the test based on high specificity, sensitivity, accuracy and positive predictive values

Grade B2: Good evidence in favor of the test with some evidence on specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, and predictive values

Grade B3: Fair evidence in favor of the test with some evidence on specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, and predictive values

Grade C: Poor evidence in favor of the test with some evidence on specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, and predictive values

Radiographic Studies

Plain abdominal radiograph

A plain radiograph of the abdomen is an inexpensive, frequently used test to complement clinical history and physical examination in patients with a suspicion of constipation [29]. However recent studies show a limited value for the role of plain abdominal radiography in the diagnosis of constipation [30-32]. Furthermore, in addition to considerable inter-observer variation in radiological assessment of fecal loading, there was very poor correlation with colonic transit. [33]. This suggest that plain abdominal radiographs may not be a reliable method to assess for fecal loading in constipation.

Barium enema

A barium enema may be useful to identify anatomic abnormalities such as redundant sigmoid colon, megacolon, megarectum, extrinsic compression, and intraluminal masses. However, there are limited studies evaluating its clinical utility [5,8]. In one retrospective study of 62 subjects, an organic lesion was not detected with barium enema [34]. In another retrospective study of 791 patients, constipation was reported in 22%, and was equally present in those with an abnormal study [35]. Both studies concluded that barium enema could not evaluate organic disease. Hirschsprung disease can be detected by barium enema, although manometry and histology are essential.

Defecography

Defecography involves imaging the rectum with contrast material and observation of the process, rate and completeness of rectal evacuation using fluoroscopic techniques [36]. It gives information regarding the anatomical and functional changes of the anorectum. It is performed by infusing 150 mL of contrast into the patient's rectum, and having the subject squeeze, cough, and expel the barium. The most common findings are poor activation of levator ani muscles, prolonged retention or inability to expel the barium, absence of a stripping wave in the rectum, mucosal intussusceptions, and / or rectocele [36, 37]. The prevalence of normal defecography varied between 10% and 75% [36].Although defecography revealed abnormalities in 77% of subjects, there was no relationship between symptoms and abnormalities [37]. Among 10 studies, abnormalities were reported in 25% to 90% and dyssynergia in 13% to 37% [5].

Though there are some advantages, its drawbacks include radiation exposure, embarrassment, interobserver bias, and inconsistent methodology. Hence, defecography is recommended as an adjunct to clinical and manometric assessment [36].

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI and dynamic pelvic MRI (MR defecography) can be useful for assessment of anorectal disorders [37, 38]. This is the only imaging modality that can simultaneously evaluate global pelvic floor anatomy and dynamic motion. Endoanal MRI may reveal changes in the external anal sphincter that are not identifiable by endoanal ultrasound, whereas MRI fluoroscopy directly shows the pelvic floor and viscera during rectal evacuation and squeeze maneuvers [39]. Some of the advantages are free selection of imaging planes, no radiation exposure, a good temporal resolution, and the excellent soft tissue contrast are some of the advantages. Dynamic pelvic MRI in the sitting position provides a more physiological approach than in the supine position [40].

Dynamic MRI is very useful in the diagnosis of rectal intussusceptions as it not only allows differentiation between mucosal and full-thickness prolapse, it also provides information on movements of the whole pelvic floor. In dyssynergic patients, dynamic MRI has shown that the anorectal angle becomes more acute, confirming paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis [38]. In a study, during rectal evacuation, the degree of perineal descent was decreased in 35%, normal in 44% and increased in 21% of constipated patients [23]. Increased perineal descent was associated with a hypertensive anal sphincter, a normal rectal balloon expulsion test, and a rectocele. In a study involving constipated patients with obstructed defecation symptoms, the diagnosis of combined pelvic floor disorders with dynamic MRI defecography was consistent with clinical results in 70% of patients and there were additional diagnostic parameters in 30% of patients [41]. Though MR defecography may be useful in certain diagnosis, its high cost and lack of standardization and availability limit its routine use.

Endoscopy

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy or Colonoscopy

Direct visualization of the colon is indicated in selected patients to exclude mucosal lesions such as solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, inflammation, or malignancy. According to the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, a colonoscopy is recommended in constipated patients if they have alarming features such as rectal bleeding, heme positive stool, iron deficiency anemia, weight loss, obstructive symptoms, recent onset of symptoms, rectal prolapse, or change in stool caliber, and in subjects older than 50 years who have not previously had colon cancer screening [42]. In younger patients, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be sufficient to exclude distal colonic disease. In a large retrospective study on constipated patients, the range of neoplasia found and the polyp detection rate were comparable to those expected in asymptomatic historical controls [43]. A recent review of the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative database showed that colonoscopy for constipation alone has a lower yield for significant findings compared with average-risk screening and constipation with another indication [44]. Therefore, there is little evidence to support the routine use of colonoscopy in constipated patients without alarm features.

Tests for Colonic Function

Detailed physiological testing should be performed in patients whose constipation is refractory to laxatives and dietary changes, and in those with a suspected evacuation disorder.

Colonic Transit Study

An assessment of the speed at which stool moves through the colon can provide an objective measurement of infrequent defecation, as the patients recall of stool habit is often inaccurate(9). Colon Transit Time can be measured by three general methods:

Ingestion of radiopaque markers followed by abdominal radiographs[45,46]

Ingestion of pressure, pH capsule (Wireless Motility Capsule)and tracking its movement[49]

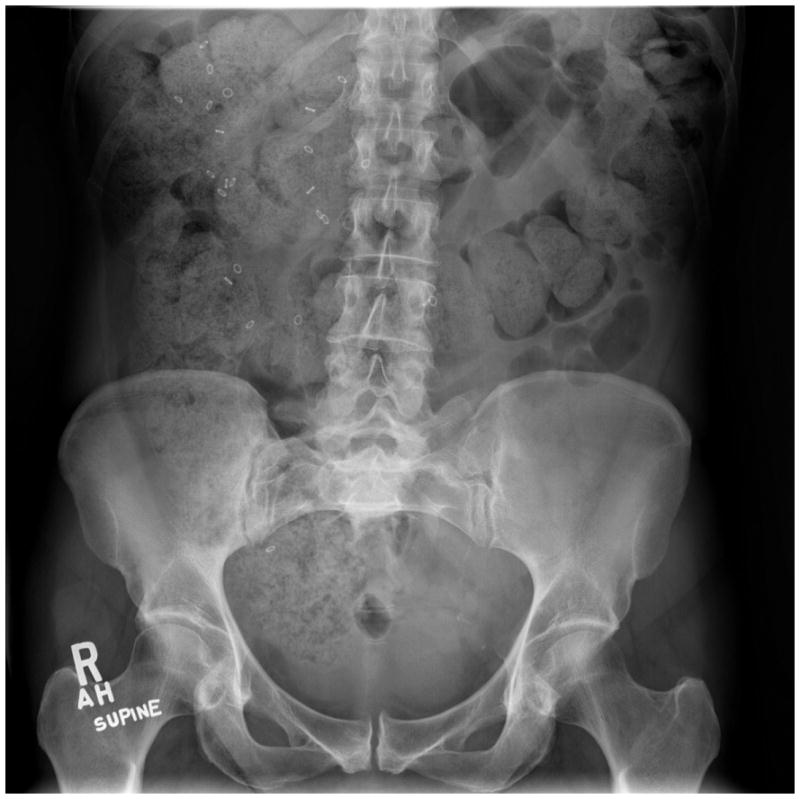

The radiopaque marker test is typically performed by administering a single capsule containing 24 plastic markers on day 1 and by obtaining plain abdominal radiographs on day 6 (120h later)[36,50,51]. Retention of atleast 20% of markers (more than six markers) on day 6 (120 h) is considered abnormal[45,51] and is indicative of Slow Transit Constipation. Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Abnormal colonic transit study with large amount of stool and retention of more than five radioopaque markers mostly in the right colon in a subject with constipation.

60% of patients with dyssynergic defecation have excessive retention of markers [52]. Hence it is important to exclude this condition before making a diagnosis of slow transit constipation [5,21]. Several studies have assessed the utility of colonic transit in the evaluation of constipation [5,50] and it can be used as a preliminary test to evaluate constipation.

Colonic transit scintigraphy is a non-invasive and quantitative method of evaluation of total and regional colonic transit [29,47]. Here, an isotope (111In or 99Tc) is administered either in a coated capsule that dissolves in the colon or terminal ileum or encapsulated in a non-digestive capsule with a test meal. Subsequently, gamma-camera images are obtained at specific time points. Assessment and interpretation of the colonic transit time varies among centers. The primary variable of interest is the geometric center at 24 h (normal range 1.7-4.0). A high geometric center represents greater than normal retention of isotope and a slower colonic transit time.

Abnormal transit has been documented with scintigraphy in a cohort of 287 patients [53] and segmental variations in colon transit have been studied using scintigraphy [54,47]. In a study of 32 patients with idiopathic constipation using indium-111-labeled polystyrene pellets, it was possible to differentiate between slow transit constipation and pelvic outlet obstruction [55]. Awareness about scintigraphic studies and their utility has been increasing. Although scintigraphic studies have been validated, and are reliable and reproducible, they are expensive and time consuming and limited to a handful of institutions [56].

Wireless Motility Capsule (WMC)

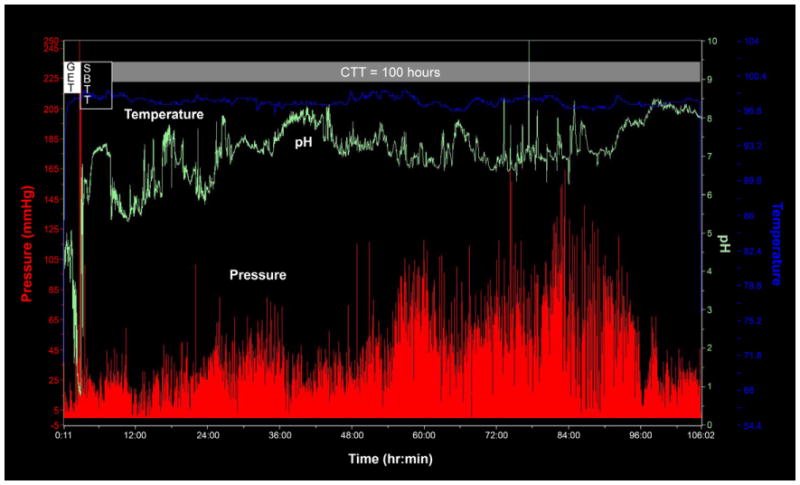

Assessment of colonic transit using a novel, ambulatory, capsule technique, WMC, provides a non-invasive method of measuring not only colonic transit but also gastric emptying and small bowel transit time [49]. By utilizing the pH change as it travels through the gut, colonic transit and whole gut transit can be assessed. Rao et al. demonstrated that the WMC has good sensitivity and specificity for evaluating colonic transit [49]. In 158 patients with chronic constipation who underwent simultaneous colon transit (Figure 2) time measurement using radiopaqe markers and WMC, there was 87 % agreement validating wireless motility capsule relative to radiopaque markers in differentiating slow verses normal colon transit time in constipation [57]. Colonic and whole gut transit with WMC correlates well with radiopaque markers and has higher specificity in diagnosing slow transit in constipation [49]. Another study showed that constipated patients with normal or moderately delayed transit show increased motor activity and that different constipation subtypes have variations in transit and motility[58]. A recent study showed that WMC has good diagnostic utility in lower gastrointestinal disorder and can detect 51% of patients with generalized motility disorder [59, 60]. It influenced management in 30% of Lower GI and 88% of Upper GI subjects, and directed treatment plan [59]. In another study, WMC lessened the need for further invasive motility tests [60]. Thus, WMC can be useful for assessing colonic motility and transit.

Figure 2.

Assessment of colonic transit with a wireless motility capsule in a subject with chronic constipation. Time is represented on the horizontal axis. The blue line represents temperature changes, the green line represents the pH changes, and the red line represents the pressure changes. GET, gastric emptying time; SBTT, small –bowel transit time; CTT, colonic transit time. The colonic transit time is delayed in this subject (normal CTT, < 59 h).

Colonic manometry

Colonic manometry provides a complete assessment of overall motor activity at rest, during sleep, after waking, after meals, and after provocative stimulation such as drugs, meal, or balloon distensions [61,62]. It is performed by using solid-state probes and portable recorders or water-perfused stationary systems [61-63]. It provides reproducible and reliable information regarding the pathophysiology of constipation [62] and can be used to explore the mechanisms and motor effects of pharmacological agents on the colon. Colonic manometry catheter is placed using one of 3 methods: nasal intubation with migration of probe into the colon, guide wire-assisted water-perfused probe placement and retrograde direct probe placement [64]. Prolonged recordings over 24 h are favored to completely understand the comprehensive colonic motor profile. Recent studies have confirmed that patients with slow transit constipation exhibit a significant reduction of phasic colonic motor activity, the gastrocolonic and morning waking responses, and the number of high-amplitude propagated contractions [62,65]. Colonic manometry thus may help to diagnose an underlying myopathy or neuropathy and differentiate slower transit due to neuromuscular function.

Tests for Anorectal Function

Anorectal Manometry

Anorectal Manometry provides an assessment of pressure activity in the anorectum and provides comprehensive information regarding rectal sensation, rectoanal reflexes and anal sphincter function, at rest and during defecatory maneuvers [36,66-68]. It is an established and widely used investigatory tool for defecatory disorders. Manometry can detect defecatory disorders (dyssynergia) and Hirschsprung disease[69]. Normally, when a balloon is distended in the rectum, there is reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter. This rectoanal inhibitory reflex is mediated by the myenteric reflex and is absent in Hirschsprung disease [70]. Qualitative assessment of RAIR may be valuable in the diagnosis of constipation as this reflex is impaired in most patients with constipation [71].

Normally when healthy subjects attempt to defecate they generate an adequate propulsive force synchronized with relaxation of the puborectalis and the external anal sphincter. The inability to perform this coordinated maneuver represents the chief pathophysiological abnormality in dyssynergic defecation [21,52].

Four Patterns of dyssynergic defecation has been described using anorectal manometry [72].

Type 1 is characterized by a paradoxical increase in the residual anal pressure in the presence of adequate propulsive pressure, that is, increase in intrarectal pressure (≥ 45mm Hg)

Type 2, characterized by an inability to generate adequate expulsive forces, ie, no increase in intrarectal pressure, together with a paradoxical increase in residual intraanal pressure

Type 3, characterized by generation of adequate expulsive forces, but absent or incomplete (< 20%) reduction in intraanal pressure and

Type 4, characterized by an inability to generate adequate expulsive forces, that is, no increase in intrarectal pressue and absence of incomplete reduction in residual intraanal pressure.

Upto 20% of asymptomatic healthy adults also cannot produce a normal relaxation during attempted defecation [66]. The body position, whether sitting or lying down, the presence of stool-like sensation, and the consistency of stool may each influence the occurrence of dyssynergia and the ability of expel artificial stools [73]. Hence the finding of a dyssynergic pattern alone should not be considered as diagnostic of dyssynergic defecation.

In a study, it was found that in addition to dyssynergic pattern, a combined abnormality of colonic transit, balloon expulsion and defecography was seen in only 13% to 38% of patients; but a single abnormal physiologic test together with dyssynergia was seen in 71% to 91% of patients. Rectal sensory testing may reveal rectal hyposensitivity. Anorectal manometry is useful for the diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation and altered rectal sensation and identifies subjects who could benefit from biofeedback therapy.

High-Resolution Manometry

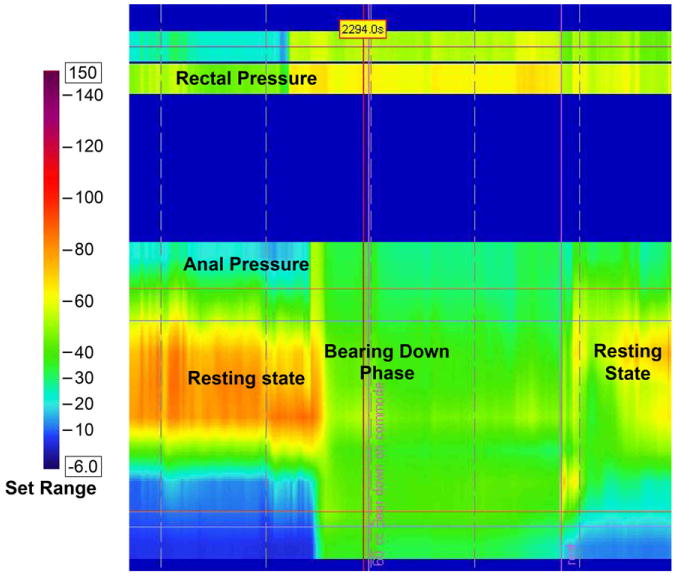

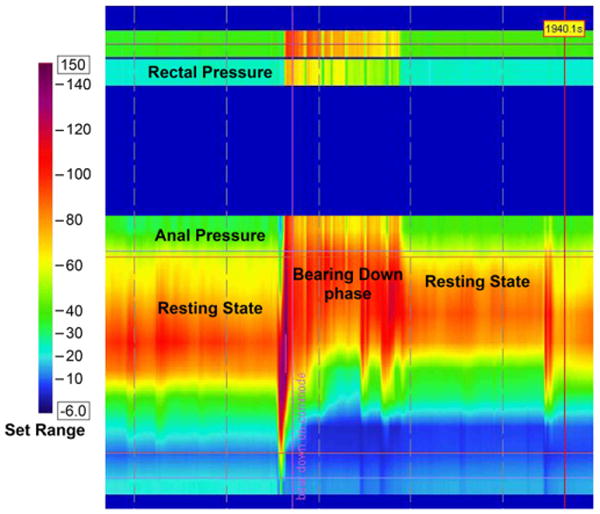

High Resolution Manometry involves a solid-state manometric assembly with 12 circumferential sensors spaced at 1-cm intervals (4.2 mm outer diameter) (Sierra Scientific Instruments, Los Angeles, CA). This device uses proprietary pressure transduction technology (TactArray) that allows each pressure sensing element to detect pressure over a length of 2.5mm in each of 12 radially dispersed sectors. The sector pressures are then averaged, making each sensor a circumferential pressure detector with the extended frequency response characteristic of solid-state manometric systems. The large numbers of closely spaced sensors provides greater detail of the pressure plots, and ensures more accuracy, especially when compared to 2-4 sensor water perfused manometry that can miss important findings. Recent studies have shown that high-resolution manometry may provides greater resolution of the intraluminal pressure environment of the anorectum and thus can help to better characterize dyssynergia [74, 75].(Figure 3a, 3b)

Figure 3.

High Resolution Manometry images showing normal pattern of defecation in a healthy subject (3 a) and an incoordinated or dyssynergic pattern of defecation in a subject with constipation and dyssynergic defecation(3 b). In the normal subject the anal pressure decreases (Green color-Pressure=20 mm Hg), whereas in the dyssynergic subject there is paradoxical increase in anal sphincter pressure (Red color-Pressure=100mm Hg). The rectal pressure increases in both subjects.

Also, a high-definition manometry system with 256 circumferentially arrayed sensors that provides anal sphincter pressure profiles and topographic changes in three dimensions is available. This system is found to be feasible, well tolerated and provides comparable information to that obtained with ARM. It provides vector manometry profile and its 3D display provides both functional and anatomical information of anal sphincter [76].

Balloon expulsion test

The balloon expulsion provides a simple, bedside assessment of a subject's ability to expel an artificial stool. There is no standard approach and several techniques have been used, including 25 ml or 50 ml balloons filled with warm water or air, 18mm spheres, silicone-filled artificial stool or weights attached to a pulley to assess the extra force required to expel a metal sphere in a lying position [77]. Most experts recommend a 50 ml water filled balloon or a silicone-filled stool-like device (Fecom) [5], which is placed in the rectum and the patient is asked to expel the device in the sitting position in privacy. Most normal subjects can expel this balloon within 1 minute [66].

The prevalence of a positive test in favor of constipation varied between 23% and 67% [5]. One study suggested a specificity of 89%, negative predictive value of 97%, sensitivity of 88% and positive predictive value of 67%. However many dyssynergics can expel the balloon, hence the test itself is insufficient to make a diagnosis [21, 72]. Thus, although the failure to expel a balloon strongly suggests dyssynergia, a normal test does not exclude this possibility. Nine studies of balloon expulsion showed impaired expulsion in 23%-67% [5]. Hence this test should be interpreted along with other physiologic tests.

Rectal barostat test

Barostat comprises of a highly compliant balloon that is placed in the rectum and connected to a computerized pressure-distending device (barostat). It can be used to assess rectal sensation, tone and compliance. The test can be useful for identifying patients with a normal, impaired or hyper compliant rectum and can help to detect megarectum. Several studies have revealed rectal hyposensitivity in patients with constipation [77-79]. Rectal barostat studies revealed rectal hyposensitivity in up to 50% of patients with IBS-C [80].

Conclusions

In conclusion, a careful history and stool diary is the initial step in the diagnosis of constipation. DRE can provide useful information on sphincter pressure, presence of dyssynergia and fecal impaction. There is little evidence to support the use of routine blood tests or endoscopy in constipated patients without alarm features. Though colonic transit studies are not standardized, there is good evidence to show its benefits. Anorectal manometry is the preferred method for diagnosis of dyssynergia and identifies patients who would benefit from biofeedback therapy. Defecography and MR defecography is useful in patients with suspected rectal prolapse or poor rectal evacuation. The balloon expulsion test can confirm impaired evacuation, but should not be used alone for diagnosis. These diagnostic tests can identify structural or functional causes of constipation, and to confirm a clinical suspicion or identify a cause for refractory bowel symptoms. However, no single test can provide a pathophysiological basis for constipation, because it is a heterogeneous condition that requires several tests to identify the underlying mechanisms.

Practice Points.

Constipation has multiple symptoms, mechanisms and etiopathology.

A detailed history, stool diary, Digital Rectal Exam and Colonic transit study are the important preliminary steps in diagnosis.

Anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion test are useful for the diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation.

Colonic manometry helps to rule out underlying neuromuscular pathology and facilitate selection of patients for colon surgery.

Wireless Motility Capsule is a novel technique for assessment of colonic, whole gut and regional gastrointestinal transit.

Research Agenda.

Criteria for classification of constipation into subtypes should be well-defined.

Colonic Transit Studies should be standardized with well established normal ranges.

Further studies are needed to be done to define the utility and role of high definition colonic manometry.

Acknowledgments

Dr Rao's effort is supported in part by grant R01DK 57100-03 National Institute of Health. The authors also acknowledge the excellent secretarial support of Mrs Sara Allen.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr.Rao serves on the advisory board for SmartPill Corporation and has received research support.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- *(1).Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349:1360–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Rao SSC. Constipation: evaluation and treatment of colonic and anorectal motility disorders. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am clinics of North America. 2009;19:117–39. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rao SSC. Principles of Clinical Gastroenterology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. Approach to the Patient with Constipation; pp. 373–398. [Google Scholar]

- *(5).Rao SSC, Ozturk R, Laine L. Clinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Jul;100(7):1605–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S, et al. Constipation: a different entity for patients and doctors. Fam Pract. 1996;13:156–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1510–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EMM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100 1:S5–S21. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ashraf W, Park F, Lof J, Quigley EM. An examination of the reliability of reported stool frequency in the diagnosis of idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rao SSC, Tuteja AK, Vellema T, et al. Dyssynergic defecation: demographics, symptoms, stool patterns, and quality of life. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:680–5. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000135929.78074.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Leung FW, Rao SSC. Fecal incontinence in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:503–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Koch A, Voderholzer WA, Klauser AG, Müller-Lissner S. Symptoms in chronic constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:902–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02051196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Dinning PG, Jones M, Fuentealba SE, et al. S1276 In Patients with Severe Constipation, Can We Predict Delayed Colonic Transit On the Basis of Symptoms? Gastroenterology. 2008;134:A-216. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Saad RJ, Rao SSC, Koch KL, et al. Do stool form and frequency correlate with whole-gut and colonic transit? Results from a multicenter study in constipated individuals and healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:403–11. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *(15).Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–4. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Heaton KW, O'Donnell LJ. An office guide to whole-gut transit time. Patients' recollection of their stool form. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:540–51. doi: 10.1080/00365520510012208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wang J, Duan L, Ye H, et al. Assessment of psychological status and quality of life in patients with functional constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;47:460–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bongers ME, van Wijk MP, Reitsma JB, Benninga MA. Long-term prognosis for childhood constipation: clinical outcomes in adulthood. Pediatrics. 2010;126:156–62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Talley NJ. How to do and interpret a rectal examination in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:820–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rao SS. Dyssynergic defecation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:97–114. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *(22).Tantiphlachiva K, Rao P, Attaluri A, Rao SSC. Digital Rectal Examination Is a Useful Tool for Indentifying Patients With Dyssynergia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;8:955–960. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Seide B, et al. Phenotypic variation in functional disorders of defecation. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1199–210. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Iasci AL, Saltarelli P, Necozioni S, et al. Predictive Value of Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) Dig Liver Dis. 2008;3;40:S23–S23. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lawrentschuk N, Bolton DM. Experience and attitudes of final-year medical students to digital rectal examination. Med J Aust. 2004;181:323–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Turner KJ, Brewster SF. Rectal examination and urethral catheterization by medical students and house officers: taught but not used. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;86:422–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wong RK, Drossman DA, Bharucha AE, et al. T1029 The Utility of the Digital Rectal Exam (DRE) Amongst Physicians and Students: A Multi-Center Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;138:S-472. [Google Scholar]

- (28).American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).van den Bosch M, Graafmans D, Nievelstein R, Beek E. Systematic assessment of constipation on plain abdominal radiographs in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:224–6. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-0065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Moylan S, Armstrong J, Diaz-Saldano D, et al. Are abdominal x-rays a reliable way to assess for constipation? J Urol. 2010;184:1692–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Pensabene L, Buonomo C, Fishman L, et al. Lack of utility of abdominal x-rays in the evaluation of children with constipation: comparison of different scoring methods. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:155–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181cb4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Reuchlin-Vroklage LM, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Benninga MA, Berger MY. Diagnostic value of abdominal radiography in constipated children: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:671–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Cowlam S, Vinayagam R, Khan U, et al. Blinded comparison of faecal loading on plain radiography versus radio-opaque marker transit studies in the assessment of constipation. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:1326–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Patriquin H, Martelli H, Devroede G. Barium enema in chronic constipation: is it meaningful? Gastroenterology. 1978;75:619–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Gerson DE, Lewicki AM, McNeil BJ, et al. The barium enema; evidence for proper utilization. Radiology. 1979;130:297–301. doi: 10.1148/130.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:735–60. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *(37).Savoye-Collet C, Koning E, Dacher J. Radiologic evaluation of pelvic floor disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:553–67. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:399–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bolog N, Weishaupt D. Dynamic MR imaging of outlet obstruction. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:293–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bertschinger KM, Hetzer FH, Roos JE, et al. Dynamic MR imaging of the pelvic floor performed with patient sitting in an open-magnet unit versus with patient supine in a closed-magnet unit. Radiology. 2002;223:501–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232010665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Elshazly WG, El Nekady AEa, Hassan H. Role of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging in management of obstructed defecation case series. Int J Surg. 2010;8(4):274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila RE, et al. ASGE guideline: guideline on the use of endoscopy in the management of constipation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:199–201. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Pepin C, Ladabaum U. The yield of lower endoscopy in patients with constipation: survey of a university hospital, a public county hospital, and a Veterans Administration medical center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:325–32. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Gupta M, Holub J, Knigge K, Eisen G. Constipation is not associated with an increased rate of findings on colonoscopy: results from a national endoscopy consortium. Endoscopy. 2010;42:208–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Evans RC, Kamm MA, Hinton JM, Lennard-Jones JE. The normal range and a simple diagram for recording whole gut transit time. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7:15–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01647654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lin HC, Prather C, Fisher RS, et al. Measurement of gastrointestinal transit. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:989–1004. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2694-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Stivland T, Camilleri M, Vassallo M, et al. Scintigraphic measurement of regional gut transit in idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;101:107–15. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).van der Sijp JR, Kamm MA, Nightingale JM, et al. Radioisotope determination of regional colonic transit in severe constipation: comparison with radio opaque markers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;34:402–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *(49).Rao SSC, Kuo B, McCallum RW, et al. Investigation of Colonic and Whole Gut Transit with Wireless Motility Capsule and Radioopaque Markers in Constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Nam YS, Pikarsky AJ, Wexner SD, et al. Reproducibility of colonic transit study in patients with chronic constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:86–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02234827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Hinton JM, Lennard-Jones JE, Young AC. A new method for studying gut transit times using radioopaque markers. Gut. 1969;10:842–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.10.10.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Rao SS, Welcher KD, Leistikow JS. Obstructive defecation: a failure of rectoanal coordination. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1042–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Manabe N, Wong BS, Camilleri M, et al. Lower functional gastrointestinal disorders: evidence of abnormal colonic transit in a 287 patient cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:293–e82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Lundin E, Karlbom U, Westlin JE, et al. Scintigraphic assessment of slow transit constipation with special reference to right- or left-sided colonic delay. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:499–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Eising EG, von der Ohe MR. Differentiation of prolonged colonic transit using scintigraphy with indium-111-labeled polystyrene pellets. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1062–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Update on gastrointestinal scintigraphy. Semin Nucl Med. 2006;36:110–8. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *(57).Camilleri M, Thorne NK, Ringel Y, et al. Wireless pH-motility capsule for colonic transit: prospective comparison with radiopaque markers in chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:874–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Hasler WL, Saad RJ, Rao SS, et al. Heightened colon motor activity measured by a wireless capsule in patients with constipation: relation to colon transit and IBS. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1107–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00136.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Rao SSC, Mysore KR, Attaluri A, Valestin J. Diagnostic Utility of wireless motility capsule in gastrointestinal motility. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181ff0122. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lee A, Michalek W, Wiener SM, Kuo B. T1067 Clinical Impact of a Wireless Motility Capsule – A Retrospective Review. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S-481. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Rao SS, Sadeghi P, Beaty J, Kavlock R. Ambulatory 24-h colonic manometry in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G629–39. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.4.G629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Rao SSC, Sadeghi P, Beaty J, Kavlock R. Ambulatory 24-hour colonic manometry in slow-transit constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2405–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Bassotti G, Betti C, Imbimbo BP, et al. Colonic motor response to eating: a manometric investigation in proximal and distal portions of the viscus in man. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *(64).Rao SSC, Singh S. Clinical utility of colonic and anorectal manometry in chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:597–609. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181e88532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Hagger R, Kumar D, Benson M, Grundy A. Colonic motor activity in slow-transit idiopathic constipation as identified by 24-h pancolonic ambulatory manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:515–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Rao SS, Hatfield R, Soffer E, et al. Manometric tests of anorectal function in healthy adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:773–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Sun WM, Rao SS. Manometric assessment of anorectal function. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;30:15–32. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Karlbom U, Lundin E, Graf W, Påhlman L. Anorectal physiology in relation to clinical subgroups of patients with severe constipation. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:343–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Tobon F, Reid NC, Talbert JL, Schuster MM. Nonsurgical test for the diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1968;278:188–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196801252780404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Reid JR, Buonomo C, Moreira C, et al. The barium enema in constipation: comparison with rectal manometry and biopsy to exclude Hirschsprung's disease after the neonatal period. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:681–4. doi: 10.1007/s002470000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Xu X, Pasricha PJ, Sallam HS, et al. Clinical significance of quantitative assessment of rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) in patients with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;42:692–8. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31814927ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Rao SSC, Mudipalli RS, Stessman M, Zimmerman B. Investigation of the utility of colorectal function tests and Rome II criteria in dyssynergic defecation (Anismus) Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:589–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Rao SSC, Kavlock R, Rao S. Influence of body position and stool characteristics on defecation in humans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2790–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *(74).Rao SSC. Advances in Diagnostic Assessment of Fecal Incontinence and Dyssynergic Defecation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:910–919. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Jones MP, Post J, Crowell MD. High-resolution manometry in the evaluation of anorectal disorders: a simultaneous comparison with water-perfused manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:850–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Tantiphlachiva K, Attaluri A, Rao SSC. Is high-definition manometry a comprehensive test of anal sphincter function? Comparative study with manometry and ultrasound. Neurogastroenterol motil. 2008;20:28. [Google Scholar]

- *(77).Gladman MA, Aziz Q, Scott SM, et al. Rectal hyposensitivity: pathophysiological mechanisms. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:508–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Gladman MA, Scott SM, Chan CLH, et al. Rectal hyposensitivity: prevalence and clinical impact in patients with intractable constipation and fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:238–46. doi: 10.1097/01.DCR.0000044711.76085.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Gladman MA, Lunniss PJ, Scott SM, Swash M. Rectal hyposensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1140–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Delvaux MM. Visceral sensitivity in explaining functional bowel disorders: from concepts to clinical practice. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2001;64:272–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Remes-Troche JM, Rao SSC. Diagnostic testing in patients with chronic constipation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:416–24. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]