Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) constitute an enormous burden for the society. The aim of the present study was to detect, document, assess and report the suspected ADRs and preparation of guidelines to minimize the incidence of ADRs.

METHODS:

A prospective-observational study was conducted in the Department of General Medicine of a tertiary care hospital for 12 months from April 2008 to March 2009. Detected and suspected ADRs were analyzed for causality, severity and preventability using appropriate validated scales and were reported. ADR alert card was prepared and given to patients. Therapeutic guidelines were prepared and given to the relevant departments.

RESULTS:

A total of 57 ADRs were detected, documented, assessed and reported during the study period the incidence was found to be 1.8%. Assessment of severity of the suspected ADRs revealed that 12% of suspected ADRs were severe and 49% of ADRs were moderate in severity. Causality assessment was done which revealed 63% of ADRs were possibly drug-related. The majority of patients who had suffered from ADRs were above 60 years (56%). Gastrointestinal system was most commonly affected (37%) and the drug class mostly associated with ADRs was antibiotics (23%). Preventability of ADRs was assessed; and the results revealed that 28% of ADRs were definitely preventable.

CONCLUSIONS:

Measures to improve detection and reporting of adverse drug reactions by all health care professionals is recommended to be undertaken, to ensure, and improve patient's safety. In this way, hospital/clinical pharmacists play the cornerstone role.

Keywords: Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR), Prevalence, India

World Health Organization (WHO) defines an adverse drug reaction (ADR) as “one which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs in doses normally used in human for prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological functions.1” According to the Centre for Health Policy Research, more than 50 percent of the approved drugs in the United States were associated with some type of adverse effect not detected prior to approval.2 At least one ADR has been reported to occur in 10 to 20% of hospitalized patients.3 Pharmacovigilance or ADR monitoring, launched by WHO in the 1960s in the wake of ‘thalidomide’ disaster, is currently an integrated global effort of more than 70 countries worldwide. After the “thalidomide tragedy” many countries have established drug monitoring systems for early detection and prevention of possible drug-related morbidity and mortality. The use of traditional and complementary drugs (e.g. herbal remedies) may also pose specific toxicological problems, when used alone or in combination with other drugs.2

In the United States, it has been reported that ADRs due to prescription and over the counter drugs during the period 1966 to 1996, affected 6.7% of patients with 3.2% death.4 While similar figures are not available for India, it is logical to surmise that the figures in relative and absolute numbers would be much higher in view of high levels of unmonitored and indiscriminate drug use widely prevalent in the country.

Most of the advanced countries have set up an adverse drug reaction reporting system at the national level. ADR reporting programs on an institutional basis can provide valuable information about potential problems in drug usage in that institution. Furthermore, reviewing pooled data from diverse geographic, social and medical population enhances the ability to identify rare events and to generate new signals and thus in setting up a sound pharmacovigilance system in the country. Therefore, setting up of ADR monitoring centers at a more regional or hospital level and integrating them with a sound network can reveal unusual or rare ADRs prevalent in Indian population.

ADR monitoring and reporting activity is in its infancy stage in India. Lack of well structured and effective ADR reporting and monitoring programe is a major problem in India in monitoring the drug safety in Indian populations. The clinicians who prescribe and followup on treatment outcomes are best suited to detect adverse reactions in their patients based on information gathered from the patients and their own clinical observations. However, due to the lack of interest and clinical acumen, aptitude and time, many untoward adverse incidents pass unnoticed. Moreover, many physicians are unaware that clinically important ADRs should be reported to the ADR reporting and monitoring centers. As a result, ADRs are often not detected or documented. This could be achieved through establishing or setting up more number of hospital-based or local ADR reporting and monitoring programs that can assist healthcare professionals. It may become a heavy burden on prescribers to ensure that they keep abreast of the evidence regarding ADR to improve the quality of patient care. Therefore, there is a greater and urgent need to create and enhance physicians′ awareness about detection, management, prevention and reporting of ADR. The benefits of pharmacists, pharmacy staffing and clinical pharmacy services to reduce ADRs are documented elsewhere.5 Studies from various literatures revealed that review and monitoring of prescribed medicines by pharmacists may help to improve the clinical condition of the patients and may reduce the cost of treatment.6 The aim of present study was to estimate the prevalence of adverse drug reactions at a private tertiary care hospital in south India.

Methods

This prospective-observational study was conducted in the Department of General Medicine at a 500-bedded multi-specialty medical institution which is one of the largest hospitals in Coimbatore. The reason for selection of the Department of General Medicine was that many studies from literature showed that a great number of Adverse Drug Reactions were seen in this department.4

The study was carried out for a period of 12 months from April 2008 to March 2009 and involved a multidisciplinary spontaneous (voluntary) reporting program that relies on both the prospective and concurrent detection of suspected adverse drug reactions and drug interactions.

All patients of either sex and of any age who developed an ADR during the above mentioned time period were included in the study and the exclusion criteria were considered as the outpatient cases, patients who developed an ADR due to intentional or accidental poisoning, ADRs due to the fresh blood/blood products, drug overdose and patients with drug abuse and intoxication.

The protocol of the study was approved by the Research and Bioethical Committee of the hospital. The authors were permitted to utilize the hospital facilities to make a follow up of the prescriptions in the selected department.

ADR Reporting

Adverse drug reaction reports were accepted from all the healthcare professionals of different specialties irrespective of their status and types of services offered. The reporter was not required to prove cause and effect prior to the reporting of “suspected” adverse drug reaction. Various modes of reporting system was adopted including use of ADR notification form, telephone reporting, direct access, referral of patients and personal meeting so as to ease the reporting of “suspected” ADRs. Once the suspected ADR was reported, patients’ medical records were reviewed and also patients and or healthcare professionals were interviewed as appropriate to collect all the necessary and relevant data pertaining to the “suspected” ADR.

The details of data collected pertaining to the reported ADR include: description of event, suspected medication, other medications including over the counter medicines and medication on admissions, presenting complaints, past medical history, allergic status, possible involvement of risk factors of an ADR and previous exposure. Later all the collected data were further reviewed and documented in a suitably designed ADR documentation form.1 Then the reported event was subjected to evaluation, and analyzed to indicate how likely it was that the implicated drug caused the “suspected” adverse reaction.

Designing of ADR Reporting System

ADR Notification Form

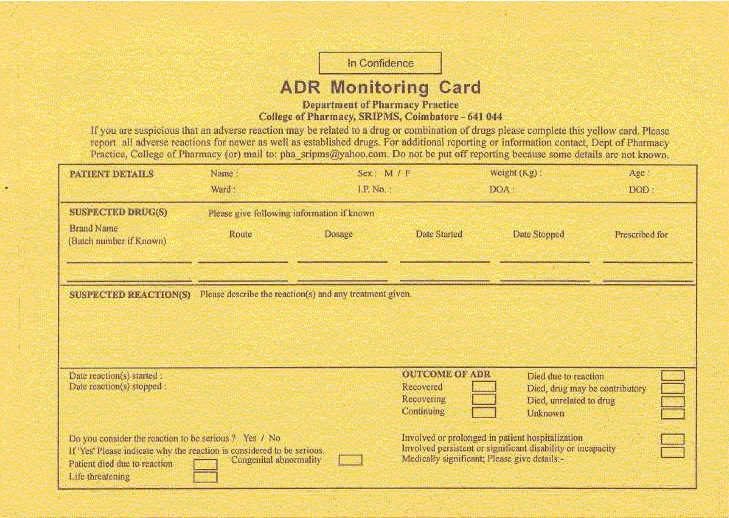

As a first step to the implementation of ADR reporting and monitoring system, a suitable “ADR notification form” (internationally known as “Yellow card”) was designed [Figures 1(a) and 1(b)]. This was prepared based on a format similar to the “Yellow card” of the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM),7 and United Kingdom (UK) and Australia's Adverse Drug Reaction Advisory Committee's (AD-RAC) “Blue card”,7 with necessary changes, to suit the present study. This notification form contained only the basic and essential information such as patient demographic details, information about the suspected medication, description of event, date and signature of the reporter.

Figure 1(a).

Adverse Drug Reaction monitoring card (front view)

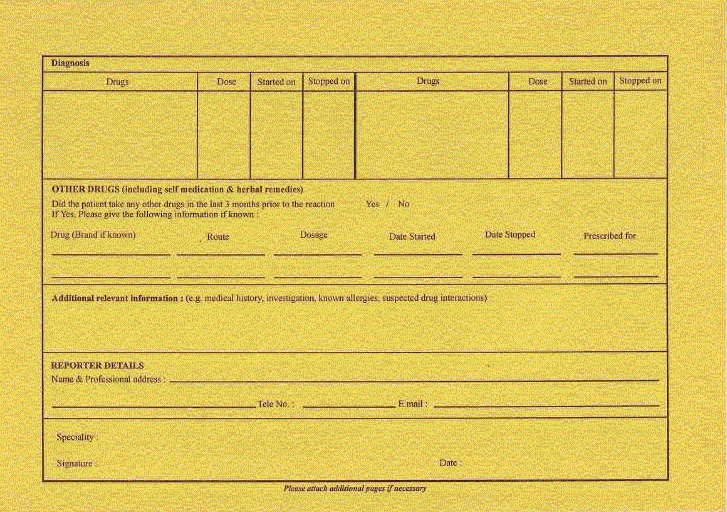

Figure 1(b).

Adverse Drug Reaction monitoring card (backside view)

ADR Documentation Form

Similarly, a suitable ADR documentation form was designed to gather and document as much relevant data as possible pertaining to the reported reaction. The ADR documentation form was tailormade by the authors according to the need. The designed ADR documentation form contained the specific details regarding patient demography, description of event, medications suspected, medication used prior to the reaction with their complete dosing regimens, comorbidities, risk factors involved, patient allergic status, causality category, severity, predictability, preventability, management of reported adverse reaction, outcome of management and follow up details.

A “thank you note” was specially designed and basically meant to thank the reporters for participating in the program and also acknowledge the receipt of the report. Further, the information regarding percentage incidence, mechanism and management of reported ADRs were provided and personalized to each reporter with information pertaining to the ADR reported by the individual.

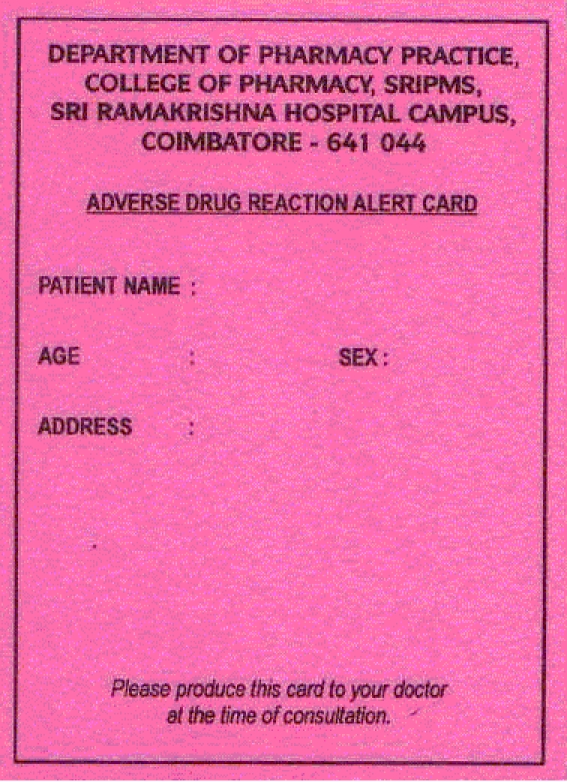

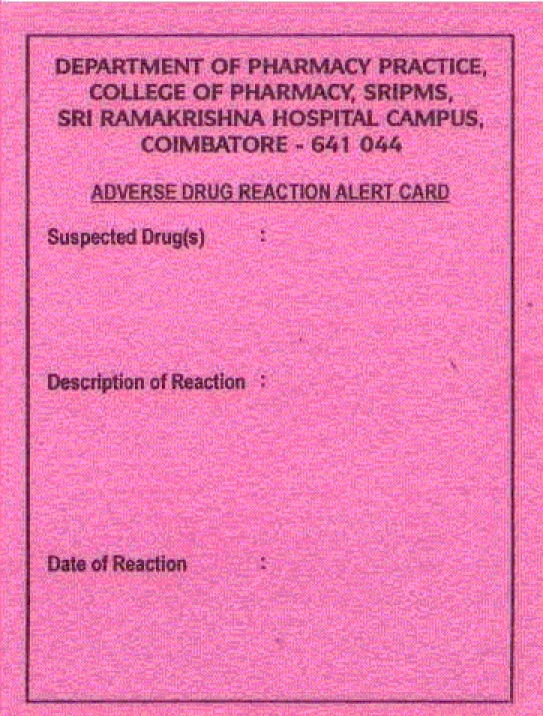

An ADR “alert card” was designed and provided to patients who developed an ADR. The “alert car”′ was designed on a similar format as that used in other countries like Australia. The “alert card” provided the details of suspected ADR, suspected medication, and date of onset of reaction on one side while other side of the “alert card” contained the demography and address of the patient. The size of the “alert card” was handy and had the appearance of a visiting card [Figures 2(a) and 2(b)].

Figure 2.

Adverse Drug Reaction alert card (front view)

Figure 2(b).

Adverse Drug Reaction alert card (backside view)

Criteria for Reportable ADR

In the present study, the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of an ADR was adopted as a criterion for reporting any suspected reaction. The WHO defines an adverse drug reaction as “one which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological function.1”

Assessment of ADR Reports

All the reported events were evaluated, after collecting adequate data from appropriate sources, as to explore the likely involvement of suspected drug in causing the reported event. In assessing the causality, concerned clinician and/or unit chief opinion was obtained. After having assessed the causal relationship between the suspected drug and the adverse reaction, irrespective of their causality category, the reports were subjected to further analysis including their severity, predictability and preventability of reported reactions.

Causality Assessment

The causality relationship between suspected drug and reaction was established by using WHO and Naranjo's causality assessment scales. The causality of reported reactions was categorized to any one of the following categories based on the scale used:

WHO Assessment Scale:8 Certain, probable, possible, unassessable/unclassifiable, unlikely, conditional/unclassified.

Naranjo's Assessment Scale:9 Definite, probable and possible;

Assessment of Severity

The severity of reported reactions was assessed by using Hartwig scale10 and was categorized into mild, moderate and severe.

Assessment of Predictability

The predictability of the reported ADRs was assessed by using developed criterion for determining predictability of an ADR and was categorized as predictable or not predictable based on the incidence rate of reported adverse drug reaction.

Assessment of Preventability

The preventability of reported ADRs was assessed by using Modified Schumock and Thornton scale11 and was categorized as definitely preventable, probably preventable and not preventable. When an event was reported, all patients who experienced an ADR were followed from the day of reporting of an ADR until the discharge of patients to gather updated information regarding the changes and the progress in the patients’ condition and management. Also, at the time of discharge “alert card” was provided to those patients who met the criteria for the issue of alert card.

Feedback to Reporters

Feedback on reported adverse drug reaction was provided to all reporters after analyzing the reported reaction. The feedback was personalized to each reporter with all necessary information pertaining to the reported ADR such as its percentage incidence, mechanism of ADR and management of reported adverse drug reaction. The feedback on reported ADR was provided by means of issue of “thank you note”.

Reporting Suspected ADRs

The suspected ADRs were reported to the pharmacovigilance center [Regional Pharma-covigilance Center (South)] through online (email: adr@jipmer.org.) and by direct mailing also.

Results

A total of 57 documented ADRs were identified in 3117 General Medicine ward admissions during the study period. The results of the age categorization revealed that the patients of 60 years and above age group experienced maximum ADRs which were about 56%, followed by 33% in age group between 30-59 years old and 11% in 18-29 years age group.

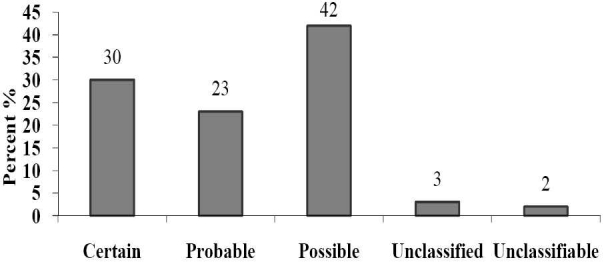

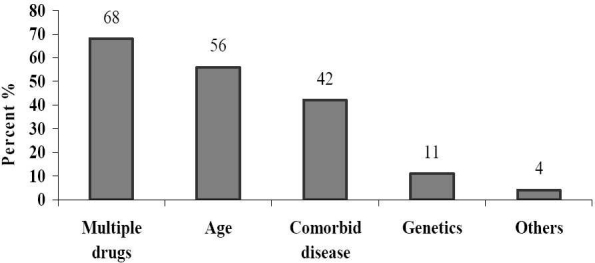

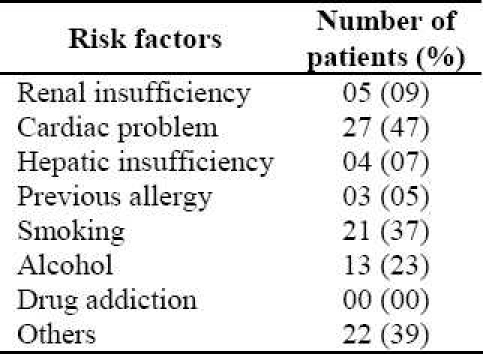

The present study revealed that 8 (14%) patients were admitted due to an ADR compared to 49 (86%) who were affected by ADR after hospital admission. Of the patients who experienced ADR during the study period 35 (61%) were male and 22 (39%) were female. Causality assessment through WHO scale indicated that 42% of them were possible (Figure 3). Causality assessment of suspected ADRs using Naranjo's scale showed that 63% of them were probable and the rest of them categorized as possible. The severity of 49% of reactions (using Hartwig scale) was reported as moderate and 12% considered as severe. On the basis of Modified Schumock and Thornton scale, 16 (28%) and 4 (7%) reactions of the suspected ADRs were definitely and probably preventable, respectively. In 21 (37%) of cases the ADR was managed by withdrawal of drug and in 12 (21%) patients the dose of drug was altered. While in 14 (25%) of cases the severity of ADR was safely decreased, 43 (75%) patients recovered from the reaction. No fatal cases were reported. Dechallange was done in 21 (37%) and the affected patients were not subjected to rechallenge. Multiple drug therapy, age and comorbid diseases were identified as the major predisposing factors for occurrence of ADRs (Figure 4). The major risk factors for causing ADRs were identified as cardiac problems, smoking, alcohol intake, etc. (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Causality assessment of suspected Adverse Drug Reactions (WHO scale)

Figure 4.

Predisposing factors for adverse drug reactions

Table 1.

Probable risk factors for incidence of Adverse Drug Reactions in studying patients

Discussion

The incidence of suspected ADRs was found to be 1.82% and is comparable with the study done by Rao et al,3 which evaluated the reports of ADRs in the inpatients at a south Indian hospital for their incidence and pattern and found that the incidence of ADRs was 2.8% in hospitalized patients. Pirmohamed et al12 concluded from a prospective analysis of about 18,820 patients in UK in which about 1225 admissions were related to ADRs giving a prevalence of 6.5%. This is consistent with the findings of Arulmani et al.13

Pirmohamed et al have shown a greater percentage of geriatric population suffering from adverse reactions which is consistent with the present results that mentioned before.12

According to the present findings the ADRs in the hospital patients were more documented in males which is consistent with the earlier report by Gupta et al.14 Sex ratio in admitted patients might be an intervening factor but does not seem to be a major determinant.

Causality assessment was done by using WHO and Naranjo scale. The assessment done by using WHO scale reveals that 42% of ADRs were possibly drugrelated, 23% of ADRs were probably drug-related, whereas 30% were classified as certainly related to drug. Assessment by Naranjo scale showed that 63% of ADRs were possibly drug-related, whereas 37% were classified as probably or definitely related to the drug. These results matches with Davies et al15 study which had assessed the feasibility and established the methodology for conducting a large prospective study to fully assess the impact of ADRs on inpatients. Causality assessment showed that 63% of ADR were possibly drug-related whereas 37% were classified as probably or definitely related to the drug and almost two-thirds of reactions were potentially avoidable.

Severity of the suspected ADRs assessed using Modified Hartwig and Siegel Scale, revealed that 12% of suspected ADRs were severe, 49% of ADRs were moderate and 39% of ADRs were mild in severity. These were comparable with the review conducted by Shuster16 in reporting ADR from the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) in cooperation with the FDA's MEDWATCH program during the month of June 2005 in a 200-bedded community hospital which reported 36 distinct admissions due to ADRs, with 9% of the cases categorized as severe, and 76% of the events were regarded as moderate.

Systems most commonly affected were gastrointestinal in 37% of patients, dermatological in 25% of patients, central nervous system in 14% of patients, followed by cardiovascular in 12% of patients. The results were comparable with an international study conducted by Suh et al, which revealed that the system most badly affected was the dermatological and gastrointestinal system.17 The drug class mostly associated with ADR was antibiotics in 23% of cases, followed by NSAIDs in 19% in the present study. Murphy and Frigo developed and implemented an ADR reporting program in Loyola University Medical Center, a 563-bed tertiary care teaching hospital located in the western suburbs of Chicago. This study revealed that the most common adverse reactions were rash; and antibiotics were the most commonly implicated drug class.18 The results were also comparable with other studies like one done by Classen et al19 which indicated that NSAIDs have caused extensive damage to human health.

Preventability of suspected ADRs were assessed by using Modified Schumock and Thornton scale, revealed that 28% of ADRs were definitely preventable while 7% of ADRs were probably preventable. This study revealed that an increased risk of ADRs is suspected in elderly patients, and that almost one-thirds of reactions were preventable. Knowledge of pharmacological principles and how aging affects drug kinetics and response were essential if we are to promote safe prescribing practices.20

The provision of “alert card” was aimed at preventing the occurrence of the similar ADR to the same drug and/or other drug(s) belonging to similar class or other classes of drugs which shows cross sensitivity reaction with suspected drug(s) in the same patient in the future.

Under-reporting is a major problem even in western countries where the pharmacovigilance system is well established. In India the major problem is a lack of proper system of pharmacovigilance. Our ability to anticipate and prevent such ADRs can be facilitated by the establishment of standardized approaches and active reporting of suspected ADRs by all healthcare professionals including physicians, dentists, nurses and pharmacists. This could be further improved by pharmacist involvement for encouraging them through conducting educational programs on pharmacovigilance, lectures, newsletters, personalized letters, etc to aid and increase reporting of ADR.

Conclusions

This study strongly suggests that there is greater need for streamlining of hospital based ADR reporting and monitoring system to create awareness; and to promote the reporting of ADR among healthcare professionals of the country. Measures to improve detection and reporting of ADR by all health care professionals should be undertaken, to ensure patient's safety. The present study hints that pharmacists’ involvement may not only greatly increase the reporting rate but also quality of reporting. It is suggested that the most appropriate approach of medication control to minimize the incidence of ADR is screening the total medication of the individual patient by a hospital/clinical pharmacist and by taking history of allergy as well as past medication and medical history. Hospital/clinical pharmacists have also a greater role to play in the area of pharmacovigilance to strengthen the national pharmacovigilance program. Developing and maintaining electronic documentation of patients’ medical records may serve as a valuable tool to detect early signals of potential ADRs. In addition, creating intranet facilities within a hospital may help in easy access for healthcare professionals to updated patients’ medical records resulting in possible detection and prevention of ADRs. Also, the implementation of a computerized reporting system in hospital setup may hasten reporting of ADRs and is suggested.

Conflict of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contributions

SS developed and wrote the protocol, and was responsible for the data analysis, and interpretation of results. AGh was responsible for data gathering, and detection and documentation of ADRs. RR was responsible for the assessment of severity and reporting of ADRs. MD was responsible for the assessment of causality assessment through standard scales. RB prepared and submitted the ADR alert card. TKR had valuable suggestions for guideline preparations. AMS prepared the manuscript and reviewed the data analysis and interpretation of results. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge the medical/nursing staff of Sri Ramakrishna Hospital, Coimbatore, for their constant support and encouragement throughout the study.

References

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. World Health Organization. Safety of medicines - A guide to detecting and reporting adverse drug reactions - Why health professionals need to take actions. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2992e/6.html . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabbur RSM, Emmerton L. An introduction to adverse drug reaction reporting system in different countries. Int J Pharm Prac. 2005;13(1):91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao PGM, Archana B, Jose J. Implementation and results of an adverse drug reaction reporting programme at an Indian teaching hospital. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38(4):293–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1200–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond CA, Raehl CL. Clinical pharmacy services, pharmacy staffing, and adverse drug reactions in United States hospitals. Pharmacother. 2006;26(6):735–47. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Society of Hospital Pharmacy. ASHP guidelines on adverse drug reaction monitoring and reporting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1995;52(4):417–9. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/52.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reporting suspected adverse drug reactions. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. [Accessed October 10, 2009]. Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Reportingsafetyproblems/Medicines/index.htm .

- 8.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1972. World Health Organization. Technical Report Series No. 498. International drug monitoring: the role of national centers. Available at: www.who-umc.org/graphics/9277.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schneider PJ. Preventability and severity assessment in reporting adverse drug reactions. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49(9):2229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau PM, Stewart K, Dooley MJ. Comment: hospital admissions resulting from preventable adverse drug reactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(2):303–4. doi: 10.1177/106002800303700229. author reply 304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admissions to hospital: prospective analysis of 18820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):15–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arulmani R, Rajendran SD, Suresh B. Adverse drug reaction monitoring in a secondary care hospital in South India. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65(2):210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan D, Anderson HR. Increasing hospital admissions for systemic allergic disorders in England: analysis of national admissions data. BMJ. 2003;327(7424):1142–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies EC, Green CF, Mottram DR, Pirmohamed M. Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: a pilot study. J Clin Phar Ther. 2006;31(4):335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shuster J. ISMP adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm. 2009;44(8):658–61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh DC, Woodall BS, Shin SK, Hermes-De Santis ER. Clinical and economic impact of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(12):1373–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy BM, Frigo LC. Development, implementation, and results of a successful multidisciplinary adverse drug reaction reporting program in a university teaching hospital. Hosp Pharm. 1993;28(12):1199–204. 1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, JP Burke. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients.Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277(4):301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jose J, Rao PG. Pattern of adverse drug reactions notified by spontaneous reporting in an Indian tertiary care teaching hospital. Pharmacol Res. 2006;54(3):226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]