Abstract

Objectives:

Preparedness and response at the time of pandemic range from writing programs to conducting procedures as well as informing the target population. The present study was conducted to evaluate the awareness of general practitioners in Tehran, at the time of H1N1 pandemic. It also aimed to identify the main sources used for gathering information at each alert level.

Methods:

Two telephone surveys were conducted with a 4 month interval, at the beginning of H1N1 pandemic alert level 5 and 6, on 90 and 100 general practitioners, respectively. The knowledge of these physicians on the symptoms of H1N1 flu, the transmission methods, the preventative measures, and existing treatments along with the sources used for gathering information were assessed.

Results:

While mass media was the main source of gathering information in the H1N1 pandemic alert level 5, more professional sources were used at the H1N1 pandemic alert level 6. Despite the acceptable improvement noted in the knowledge of the physicians during the two phases of the study, their understanding of the disease was believed to be less than the expected level based on H1N1 pandemic alert level.

Conclusions:

The routine use of mass media as one of the main sources of information gathering at the two stages of the study points out its importance in providing physicians with the required information at the time of H1N1 pandemic. Using adequate, up-to-date, but non-specialized media can fill the gap in information gathering, required for fighting pandemic.

Keywords: Influenza, Media, Knowledge, Iran

INTRODUCTION

Pandemic preparedness is an attempt through which the healthcare system can have a better understanding about different aspects of the pandemic. It aims to lower the rate of transmission and mortality caused by the disease.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) has urged all the countries to establish a national preparedness program based on five main aspects: the healthcare system, laboratory facilities, collaborations, providing the required care in the society, and producing and providing the necessary drugs and vaccines at the time of H1N1 pandemic.2 These guidelines are developed depending on the epidemic alert level, in a way that the action plans focus on establishing the preparedness and response programs at the time of H1N1 pandemic alert level 1 to 3, when no human to human transmission is reported. When the level of influenza pandemic alert is increased from phase 4 to 6, however, the focus is shifted to the response as the risk of spreading and human to human transmission increase during this time.3 Apart from accurate communications, the development of well planned and coordinated action plans, healthcare system, public health interventions, health system responses along with the maintenance of essential services and operation capacity are needed for preparing the society against a pandemic.4 Communication and informing strategies are considered as the most important epidemic management programs which can reduce the unwanted and unpredicted economic and social burden of the pandemic. Such strategies should differ based on the social condition and needs as well as the alert level. In this approach, not only the healthcare system but also its subgroups, ranging from policymakers and healthcare providers to the general public and media are of great importance and therefore, should receive the required information in various manners.1,3 Swine flu cases were detected in different parts of the world in less than two months after the first patient was diagnosed with the disease in April 2009.2 In June 2009, the level of influenza pandemic alert was increased from phase 5 to the highest phase, indicating that the human to human transmission of the disease was seen in all parts of the world.5,6 In Iran, the first case of the disease was detected within a week after H1N1 pandemic alert level 6 was declared by WHO.7 Soon after, in line with other parts of the world, the number of the infected cases started to increase rapidly; hence, the number of the affected cases increased from 1194 in 22 October 2009 to 3762 cases in mid December.6,7 The present study is the first such research conducted to assess the knowledge of physicians regarding H1N1 and the related issues at the time of the pandemic. In this regard, the knowledge of the physicians who lived in Tehran along with the source through which they had gathered their information about H1N1 flu was recorded at the H1N1 pandemic alert level 5 and thereafter, within four months. The results of this study can provide the policymakers in the Iranian Center of Disease Management with the appropriate information needed for designing suitable interventional educational programs.

METHODS

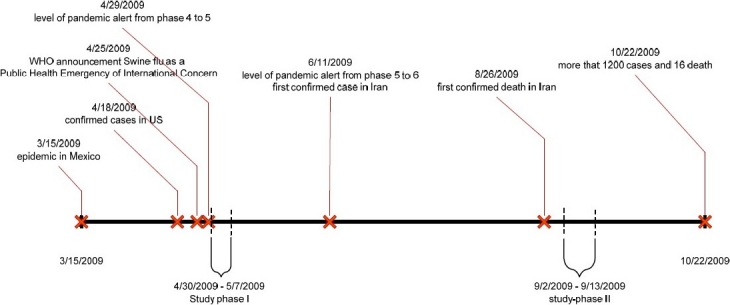

In this cross-sectional study, two telephone surveys were conducted on the physicians living in Tehran, the capital of Iran (Figure 1). The first step was conducted in 6 consecutive days from 2 to 7 May 2009, soon after H1N1 pandemic alert level 5 was announced. The second step, though, was conducted in 12 consecutive days from 2 to 13 September 2009, shortly after WHO had announced H1N1 pandemic alert level 6 and the first case of death from the disease was reported in Iran. The phone number of physicians was collected from the White book, Tehran's book of doctors. The inability to contact a physician after three calls was considered as a noresponse. A 21-item questionnaire on the epidemiology, the transmission methods, the symptoms, the preventative measures, and the treatment of swine flu were filled out for each physician. At the end of the interview, the physicians were also asked about the source through which they had gathered their information about the disease. The questionnaire was filled out through a telephone interview by a trained technician. During the data analysis, the frequency of the correct answers for each question was first calculated in each step; thereafter, the risk ratio and the 95% confidence interval was calculated by estimating the risk ratio of picking the correct answer by chance in the second phase to that in the first phase. Considering the importance of the study, the first step was started after receiving the approval of the Vice Chancellor of Research of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). As for the second phase, however, the protocol of the study was approved by the Ethical Board Committee of TUMS. An oral informed consent was obtained from the physicians who were vulnerable of participating in the study. The technician in charge of interviewing would provide the physicians with the correct answers at the end of the interview in case they asked for it.

Figure 1.

The study timetable based on the characteristics of the epidemic

RESULTS

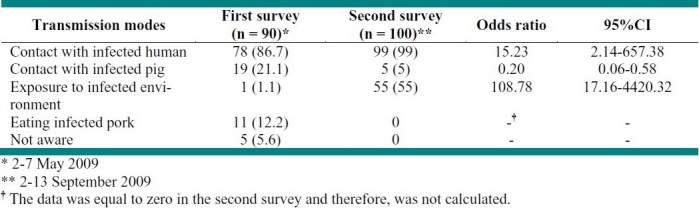

About 90 physicians (from 106 phone calls) in the first round and 100 physicians (from 100 phone calls) in the second round accepted to take part in the study. Male physicians accounted for 78.9% (71) and 71% (71) of the physicians participating in each round of the study, respectively. From among the studied physicians only 26 (28.9%) and 7 (7%) were accurately aware of the H1N1 pandemic alert level in the two phases of the study, correspondingly. The knowledge of the studied physicians about the H1N1 transmission methods is shown in Table 1. Based on this table, 86.7% of the physicians in the first step and 99% of them in the second phase believed that human to human transmission is the most important method of transmission (OR = 15.23, 95%CI: 2.14-657.38). Close contact with an infected pig (21% vs. 5%, respectively, OR = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.06-0.58) as well as getting exposed to an infected environment (1.1% vs. 55%, respectively, OR = 108.78, 95%CI: 17.164420.32) were considered as the next most common methods of transmission in this study.

Table 1.

The physician's point of view regarding the transmission modes of H1N1 flu

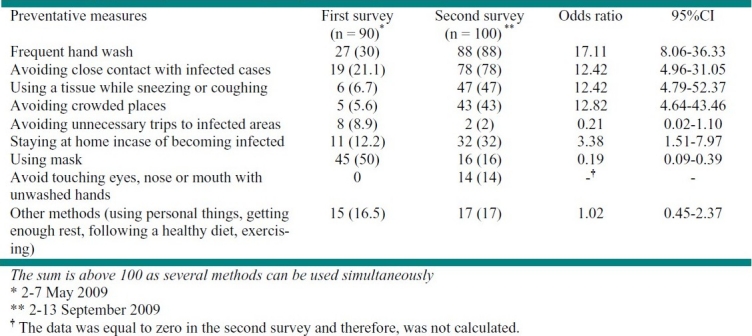

Table 2 shows the physicians′ point of view about the possible preventative measures which could be adopted against influenza. A considerable improvement was noted in the knowledge of the studied physicians regarding the possible preventative measures in the two phases of the study. The most important preventative measures including hand washing (OR = 7.11, 95%CI: 8.06-36.33), avoiding close contact with infected cases (OR = 12.42, 95%CI: 4.96-31.05), using a tissue at the time of sneezing (OR = 12.42, 95%CI: 4.79-52.37) and avoiding crowded places (OR = 12.82, 95%CI: 4.64-43.46) were named by less than 30% of the physicians in the first step of the study; more physicians, however, named these simple measures as effective strategies in fighting H1N1 flu in the second step.

Table 2.

The physician's point of view regarding the H1N1 preventative measures

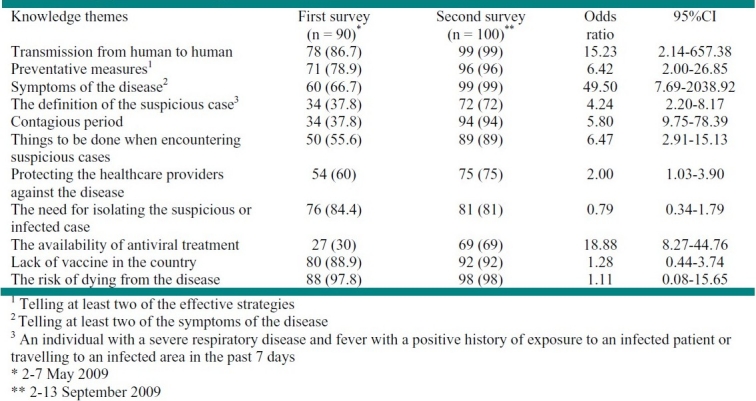

On the other hand, avoiding unnecessary trips to the infected areas (OR = 0.21, 95%CI: 0.02-1.10) and using masks (OR = 0.19, 95%CI: 0.09-0.39) were less commonly mentioned in the second phase of the survey. At the first step, more than 70% of the physicians were aware of the human to human transmission of the disease, the need for isolating the patient, lack of effective vaccine in the country, and the risk of dying from the disease. Less than 40% of them, however, accurately knew the symptoms of the disease, the characteristics of the suspicious cases, the time during which the disease was contagious, and the effective antiviral treatment.

Based on the results of the second round of interviews, more than 70 percent of the physicians were aware of the abovementioned issues, except for the need for isolating the suspicious and confirmed cases (Table 3). The physicians′ knowledge about the medical treatment increased from 30% in the first step to 69% in the second step (OR = 18.88, 95%CI: 8.27-44.76).

Table 3.

The physician's point of view regarding the H1N1 preventative measures

Table 4 revealed that national television (60%), media (36.7%), radio (21.1%) and internet (17.8%) were the most common sources used for gathering the required knowledge in the first stage of the study. Medical books and journals (69%, OR = 47.85, 95%CI: 15.57-190.68), television (61%, OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 0.56-1.95), educational pamphlets (36%), and internet (33%, OR = 2.28, 95%CI: 1.1-4.83) were more frequently used in the second step of the study.

DISCUSSION

During the time in which a pandemic is predictable until the occurrence and extension of the deadly disease (the H1N1 pandemic alert level 5 and 6), programs should focus on preparing the society and the healthcare system for response and mitigation efforts needed for reducing the complications of the disease.7 Based on the findings of the first step of the study, the physicians‘ knowledge was not compatible with the response and mitigation efforts needed for controlling a pandemic at the beginning of the alert level 5. Despite the fact that a considerable improvement was reported in the physicians’ knowledge at the second step of the study, the adopted preparedness strategies failed to achieve their final goal in lowering the complication rate due to the delay found in gathering the required information on time.3 Similar to other telephone surveys, the present study suffered from certain limitations, particularly in gathering the required information. The authors, however, tried to overcome the majority of these limitations through training suitable interviewers, preparing certain guidelines for the interview and modifying the questionnaire after the pilot study. Moreover, lack of information on many of the new physicians may have limited the number of general practitioners recruited in this study; the sampling technique used in this study, however, have lowered the risk of possible selection bias. Improving the physicians’ knowledge on the existing preventative measures (Table 2) and H1N1 influenza (Table 3) within the four-month period of the study revealed that many of the studied general practitioners have improved their understanding of the topic during the study period. The delay in gathering the required information on time, though, disturbed the accurate transfer of the essential knowledge to the society, preventing the occurrence of the necessary and prompt changes in the social behavior, required for the improvement of the outcome of the study. For instance, only one third of the studied physicians were aware of the correct definition of suspicious cases, the time during which the disease is contagious, and the availability of antiviral treatments. Understanding the accurate definition of the disease at the time of an epidemic had long been considered as one of the most important components needed for developing an efficient healthcare program for preventing possible health problems faced during this time.1,8 Knowing the accurate laboratory and clinical definitions as well as developing the required collaborations between the healthcare providers can also improve the chain of care offered in the society.9 As a result, physicians should be not only aware of these definitions but also updated about the changes made in these definitions at the time of an epidemic. Not being up to date therefore, is a problem which can interfere with the strategies adopted by both the national and regional healthcare systems for fighting the problem. Updating the knowledge of different classes of the society about non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) in the first stages of an epidemic is of great importance especially for infections such as H1N1 which is believed to spread rapidly but has no effective vaccine and the majority of the populations do not have any access to the upcoming vaccines due to socioeconomic problems.10 While WHO has considered mass media as an important mediator of epidemic control, the results of the first step of the study also revealed television, journals, satellite and radio as important sources of information for many physicians.1,3,11 The frequent use of such media even by physicians at the time when WHO had announced the highest H1N1 pandemic alert level should urge policy-makers to focus more on the accuracy of the information provided by such media. Many physicians continued to use mass media besides medical journals and textbooks in the second phase of the study, pointing out the importance of media in gathering information at the time of an epidemic.

The important role of well-organized collaboration in different phases of preparedness and alert made WHO officials design a 5-item guideline based on development, confidence, clearance, announcing early and listening for the time of an epidemic. It should be stressed that publishing simple information and recommendations about the disease is not sufficient due to the complexity of the risk factors and the disease itself.3 In other words, besides the speed of the media in contributing the news, its nature is also of great importance. The rapid increase in the H1N1 pandemic alert level (less than 2 months) also points out the need for using more rapid sources of information transfer.2 Compared with other officials, many individuals consider physicians as a more reliable source of information; they therefore, play an important role in teaching the general public about the existing preventative measures and subsequently, in controlling the epidemic.10,12,13

Recommendations

Detecting, treating and taking care of the infected cases are the main challenges faced during a H1N1 pandemic.14,15 Non-pharmacological treatment and ontime transfer of knowledge to the target populations ranging from general public to healthcare providers, therefore, are considered as important and effective strategies in fighting the disease in many countries. Considering the importance of on-time informing, identifying the best media for announcing the target population about more information in a shorter time is of great importance.16 The present study revealed that many physicians preferred to use mass media along with medical books for remaining up to date, pointing out the importance of mass media at the time of epidemic.17 The high speed of epidemic spreading in different populations and the fact that the majority of educational programs, such as publishing a brochure and guidelines, holding seminars and educational courses, used to inform the healthcare providers about the disease are time consuming, points out the need for providing the physicians with the required information through educational courses presented in mass media such as television, radio and newspaper.

Conflict of interest statement:

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Source of funding:

Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Philadelphia: World Health Organization; 2005. WHO checklist for influenza pandemic preparedness planning. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan SI, Akbar SM, Hossain ST, Mahtab MA. Swine influenza (H1N1) pandemic: developing countries’ perspective. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(3):1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, Global Influenza Program. Philadelphia: World Health Organization; 2009. Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mensua A, Mounier-Jack S, Coker R. Pandemic influenza preparedness in Latin America: analysis of national strategic plans. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(4):253–0. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns SM. H1N1 influenza is here. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(3):200–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coker R. Swine flu. Fragile health systems will make surveillance and mitigation a challenge. BMJ. 2009;338:b1791. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Islamic Republic of Iran [Online] Available from: URL: http://www.behdasht.gov.ir/.

- 8.Baden LR, Drazen JM, Kritek PA, Curfman GD, Morrissey S, Campion EW. H1N1 influenza A disease--information for health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(25):2666–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0903992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald DA. Human swine influenza A [H1N1]: practical advice for clinicians early in the pandemic. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2009;10(3):154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eastwood K, Durrheim D, Francis JL, d’Espaignet ET, Duncan S, Islam F, et al. Knowledge about pandemic influenza and compliance with containment measures among Australians. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(8):588–94. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paek HJ, Hilyard K, Freimuth VS, Barge JK, Mindlin M. Public support for government actions during a flu pandemic: lessons learned from a statewide survey. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(4 Suppl):60S–72S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908322114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balkhy HH, Abolfotouh MA, Al Hathlool RH, Al Jumah MA. Awareness, attitudes, and practices related to the swine influenza pandemic among the Saudi public. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan B. How the media reported the first days of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009: results of EU-wide media analysis. Euro Surveill. 2009;14(30):19286. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.30.19286-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hebert PC, MacDonald N. Preparing for pandemic (H1N1) 2009. CMAJ. 2009;181(6-7):E102–E10. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lurie N. H1N1 influenza, public health preparedness, and health care reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):843–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0905330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham T. Risk and outbreak communication: lessons from alternative paradigms. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(8):604–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.058149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNab C. What social media offers to health professionals and citizens? Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(8):566. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.066712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]