Summary

Although substantial advances have been made in behavioral and pharmacological treatments for addictions, moving treatment development to the next stage may require novel ways of approaching addictions, particularly those derived from new findings regarding of the neurobiological underpinnings of addictions, while assimilating and incorporating relevant information from earlier approaches. In this review, we first briefly review theoretical and biological models of addiction and then describe existing behavioral and pharmacologic therapies for the addictions within this framework. We then propose new directions for treatment development and targets that are informed by recent evidence regarding the heterogeneity of addictions and the neurobiological contributions to these disorders.

I. Overview

Despite intensive research and significant advances, drug addictions remain a substantial public health problem. Drug addictions cost US society hundreds of billions of dollars annually and impact not only the addicted individuals, but also their spouses, children, employers, and others (Uhl and Grow, 2004; Volkow et al., in press). Furthermore, costs may be even higher as non-drug disorders (e.g., related to food and gambling) have recently been conceptualized within an addiction framework, with neurobiological data supporting similarities across substance dependences, obesity and pathological gambling (Frascella et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2010b; Kenny, in press; Potenza, 2008). Given the additional health burdens of these conditions (e.g., obesity and tobacco consumption represent two top causes of preventable death (Danaei et al., 2009; Kenny, in press)), addictions arguably represent our nation’s (and the world’s) main health problem. Thus, the development of improved prevention and treatment strategies is of paramount importance.

In order to best prevent and treat addictions, it is important to have a clear understanding of which disorders constitute addictions, and this point has been debated considerably over time. The term addiction, derived from a Latin word meaning “bound to” or “enslaved by”, was initially not linked to substance use (Maddux and Desmond, 2000). However, over the past several hundred years, addiction became associated with excessive alcohol and then drug use such by the 1980s it was largely synonymous with compulsive drug use (O'Brien et al., 2006). However, observations that individuals with gambling problems share clinical, phenomenological, genetic and other biological similarities with people with drug dependences has prompted reconsideration of the core features of addiction, with continued performance of the behavior despite adverse consequences, compulsive engagement or diminished control over the behavior, and an appetitive urge or craving state prior to behavioral engagement representing core elements (Holden, 2001; Potenza, 2006; Shaffer, 1999). If these are considered the central elements of addictions, then behaviors like gambling may be considered from an addictions perspective. Consistent with this notion and existing clinical, pre-clinical and neurobiological data, pathological gambling is being considered for re-classification with substance use disorders into an addictions category in DSM-V (Holden, 2010).

In addition to similarities across addictive disorders, there are also differences relevant to individual addictions that are related to features like the sites of action of the drugs being abused and the social acceptability and availability of the behavior or substance, and these represent important considerations with respect to the neurobiologies and treatments of addictions. For example, while compulsivity may cut across addictions, aspects of tolerance and withdrawal may differ and reflect specific neuroadaptations related to individual substances or behaviors (Dalley et al., in press; Kenny, in press; Sulzer, in press). Thus, considering the mechanisms underlying addictions in general as well as features unique to individual disorders is important in treatment development.

Multiple, non-mutually exclusive models (e.g., incentive salience (Robinson and Berridge, 2001), allostasis (Edwards and Koob, 2010; Koob and Le Moal, 2001), reward deficiency (Blum et al., 1996)) have been proposed for addictions. While they each have unique features, they also include common features related to the proposed core elements of addiction described above. Across these models, motivational neurocircuitry functions to favor drug use (or behavioral engagement) over other aspects of life (e.g., studying for tests, going to work, or caring for one’s family). Consistently, addiction has been termed a condition of motivated behavior going awry (Volkow and Li, 2004) and neurobiological models of motivational circuitry have been proposed for addictions and addiction vulnerability (Chambers et al., 2003; Everitt and Robbins, 2005; George and Koob, 2010). In these models, cortico-striato-pallido-thalamo-cortical loops form a central feature underlying motivated behaviors (Alexander et al., 1990; Alexander et al., 1986). Other brain regions and circuits contribute importantly to motivational behaviors, with regions like the amygdala providing important affective information, the hippocampus important contextual memory information, the hypothalamus and septum important homeostatic information, and the insula important information related to interoceptive processing (Chambers et al., 2003; Everitt and Robbins, 2005; George and Koob, 2010; Naqvi and Bechara, 2009). Additionally, cingulate cortices provide important contributions, with the anterior and posterior components contributing to emotional regulation, cognitive control and stress responsiveness (Botvinick et al., 2001; Bush, 2000; Sinha, 2008). While often relatively simplistic, such models, particularly when considered from a systems perspective (i.e., these brain regions function in circuits rather than in isolation), provide a neurobiological basis for developing new treatments for addictions and investigating the mechanisms by which effective therapies for addictions work.

Aspects of the development of addictions can be understood on the basis of both positive and negative reinforcements linked to drug use. Drug experimentation typically begins during adolescence, initially resulting in hedonic experiences that generate relatively immediate positive reinforcement for use with little or no negative consequences (Rutherford et al., 2010; Wagner, 2002). Yet as drug use continues, neuroadaptations occur relating to the development of drug tolerance, resulting in a reduction in the pleasurable sensations achieved from a similar initial level of drug use. Although the precise adaptations remain a topic of current investigation, motivational neurocircuitry and multiple neurotransmitter systems, particularly dopamine, are implicated (Rutherford et al., 2010; Sulzer, in press). As this cycle continues, subjects increase the frequency and amount of drug use to gain the same rewarding experience. For many drugs, increased use also leads to withdrawal symptoms when drug use is curtailed or cut down. As withdrawal symptoms can at least be temporarily relieved by continued, and escalating, drug use, a vicious cycle is established. Over time, hedonic motivations for substance use diminish while negative reinforcement motivations increase, with drug-taking behaviors becoming less rewarding and more compulsive or habitual over time. This shift has been proposed to involve a progression of involvement of ventral to dorsal cortico-striato-pallido-thalamo-cortical circuitry (Brewer and Potenza, 2008; Everitt and Robbins, 2005; Fineberg et al., 2010; Haber and Knutson, 2010). From a molecular level, dopamine function, particularly striatal D2/D3 receptor function, appears relevant to this process and has been implicated across addictive disorders (Kenny, in press; Steeves et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009). However, multiple other neurotransmitter systems contribute and may represent better treatment targets, particularly as D2/D3 receptor antagonists have not demonstrated clinical efficacy for addictions.

From a cognitive perspective, attempts to control or eliminate addictive behaviors are usually motivated by the delayed negative consequences of use. The individual’s cognitive recognition of these negative consequences may lead to attempts to develop changed attitudes and drug-using behaviors. This process necessitates executive control which may be mediated via top-down control of the prefrontal cortex over subcortical processes promoting motivations to engage in the addictive behavior (Chambers et al., 2003; Everitt and Robbins, 2005). Both positive reinforcement processes (e.g., seeking a drug high) and negative reinforcement processes (e.g., seeking relief from stressful or negative mood states) may be linked to environmental or internal cues in fashions that are behaviorally engrained, resistant to change and linked to powerful motivational craving states (Chambers et al., 2007). Thus, therapies may be needed to target strong learned associations between drug use and immediate positive or negative reinforcements.

Phases of treatment

The treatment for addictions can be divided into three phases: detoxification, initial recovery and relapse prevention. The first phase, detoxification, has the goal of achieving abstinence that is sufficiently sustained to yield a safe reduction in immediate withdrawal symptoms. The second phase, initial recovery, has goals of developing sustained motivation to avoid relapse, learning strategies for tolerating craving induced by external or internal cues and developing new patterns of behavior that entail replacement of drug-induced reinforcement with alternative rewards. The third phase, relapse prevention, takes place after a period of sustained abstinence, and requires subjects to develop long-term strategies that will allow them to replace past drug behaviors with new, healthy behaviors.

As discussed above, the drug addiction cycle is maintained through repeated use and alterations to motivational neurocircuitry, including dopaminergic systems. Given the need to disengage from sustained patterns of use and related neuroadaptations, detoxification frequently requires pharmacological intervention. These initial drug treatments may involve choosing a replacement substance that has a similar mode of action on the neurobiological substrate, while having a slower and more sustained effect. Behaviorally speaking, this results in withdrawal symptoms that are made less acute but more prolonged and gradual. For example, drugs with longer half-lives than herion (e.g., methadone) can be used in addicted individuals during detoxification.

Successful resolution of detoxification requires sustained motivation to tolerate withdrawal symptoms. The second phase, initial recovery, is often aided by external, structural controls (e.g., hospitalization) which limit access to drugs once withdrawal symptoms have been alleviated. Yet, ultimately, the initial recovery phase must teach the addicted individual ways to sustain motivations to avoid relapse, learn strategies for tolerating and resisting drug cravings induced by external or internal cues and develop new patterns of behavior that entail replacement of drug-induced reinforcement with alternative rewards. Learning these new behavioral strategies can also be aided by the longer term administration of medications such as those used in the detoxification process (e.g., drugs that block or reduce drug rewards, reduce craving by substituting for drug effects) or by the additional augmentation with drugs that help to reduce mental and physical symptoms not necessarily related to drug use (e.g., independent depression or anxiety disorders).

The third phase, relapse prevention, is perhaps the most difficult to achieve given the long-term brain adaptations resulting from sustained drug abuse. Indeed, relapses often occur and many relapse prevention programs involve a continued support system (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous, etc) to aid in maintaining new behaviors developed during initial recovery. Threats to recovery involve both external and internal cues that lead to waning motivation, attenuation of external or internal controls and revival of associative learning cues linking drug use to hedonic experiences, and can be triggered by both external cues and internal cues. External cues include exposure to drugs or to people, places or things associated with drug use. Internal cues include hedonic experiences that may be enhanced by resumed drug use or dysphoric experiences that may be mediated by such factors as stress, interpersonal conflict or symptoms of comorbid mental disorders such as depression.

At all three phases, social processes can improve executive functioning through a variety of mechanisms, including enhancing motivation, reducing friction and stress, providing alternative rewards associated with avoiding drug use and providing external constraints. These factors can be conceived of as enhancing cortically mediated executive control over addictive behaviors (Volkow et al., in press).

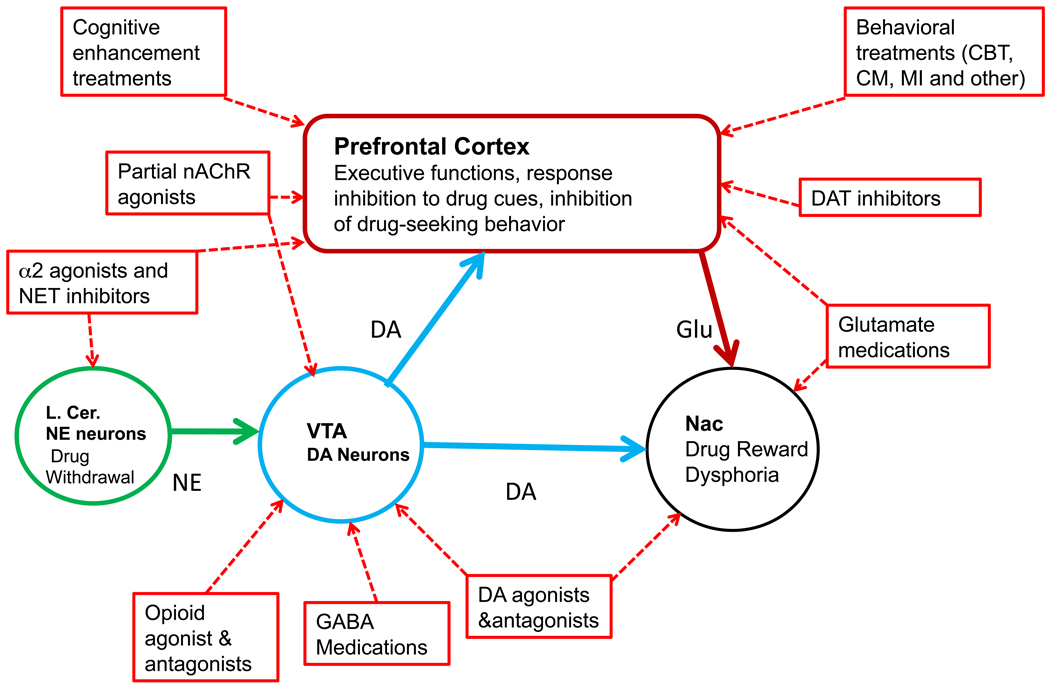

In the next sections, we will briefly review the major behavioral and pharmacological treatments for addictions and describe the targets of these treatments. In a simplified description, the neural processes targeted by treating addictions can be characterized as “top-down” or “bottom-up.” Top-down interventions attempt to change cognitions and behaviors mediated by enhanced prefrontal cortical function and altered executive control. Bottom-up interventions target the sub-cortical processes, including the striatal reward pathways, that mediate dysphoric symptoms and learned association pathways that do not require or necessarily involve cortical activity. As a broad generalization, current behavioral treatments appear strongest at changing top-down activity while pharmacological treatments tend to target bottom-up processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The brain regions proposed to mediate the behavioral and pharmacological treatments of addictions. For simplicity, only a few key brain regions are included in the figure. See text for details. Abbreviations: AD: adrenergic receptors; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; CM: contingency management: DA: dopamine; DAT: dopamine transporter; l.cer: locus ceruleus; MI: motivational interviewing; nAChR: nicotinic cholinergic receptor; NE: norepinephrine; NET: norepinephrine transporter; VTA: ventral tegmental area.

Behavioral Therapies Strategies and Targets

Compulsive drug use despite negative consequences and despite the desire to quit can be understood as entailing two processes that are targets for behavioral therapies: 1) the excessive desire to use or craving for substances; and, 2) insufficient impulse control associated with neurocognitive impairment. In the sections below we briefly review three broad categories of behavioral interventions that have achieved consistent empirical support for substance use problems through randomized controlled trials. These are (1) brief and motivational models, (2) contingency management models, and (3) cognitive behavioral models.

Brief motivational models

A surprising revelation of the past 20 years of treatment research in the addictions has been the efficacy and durability of brief behavioral therapies for many individuals with substance use problems (Burke et al., 2003; Miller and Rollnick, 2002). Relatively brief, focused interventions consisting of as little of a single session have not only been demonstrated to be effective, but in several studies been shown to be as effective as lengthier, more intensive approaches. The efficacy of brief motivational approaches appears to extend to addictions that do not involve ingested substances (Burke et al., 2003), including pathological gambling and eating disorders (Brewer et al., 2008b; Frascella et al., 2010), suggesting that similar neural mechanisms may underlie therapeutic effects across addictions. Although the precise neural mechanisms mediating the effects of brief motivational interventions are not known, processes involving the receipt of health-related information and recommendations from a professional may prompt individuals to alter their decision-making processes to focus on more future-oriented goals. Thus, brain motivational circuitry in general and specific regions implicated in risk-reward decision-making (e.g., ventromedial prefrontal cortex), cognitive control (e.g., anterior cingulate cortex), planning and executive functioning (e.g., dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) in particular may represent important brain regions for consideration (Bechara, 2003; Bush et al., 2002; Dalley et al., in press).

Contingency management models

Another major development in the treatment of substance use problems has involved findings regarding the efficacy of contingency management interventions (Dutra et al., 2008; Lussier et al., 2006). Based on principles of behavioral pharmacology and operant conditioning, contingency management approaches recognize that abused substances are powerful reinforcers, and are implemented with the idea that immediate reinforcement of abstinence (or other behaviors incompatible with substance use) can reliably, and comparatively easily, interrupt substance use for a large number of individuals. In the case of substance dependence, individuals are provided concrete rewards, often cash, that generally escalate in value and are contingent on submitting drug-free urine specimens (Higgins, 1991). Beyond producing some of the largest and most consistent effect sizes in substance abuse treatment (Dutra et al., 2008), these approaches have broad utility and can be targeted to improve treatment adherence, including medication compliance that often undercuts the efficacy of available pharmacotherapies (Carroll, 2004).

Contingency management for addictions can be conceptualized within a behavioral neuroeconomic framework (Glimcher and Rustichini, 2004). Individuals with addictions as compared to those without typically place comparably greater values on immediate rewards, and future rewards are more rapidly devalued, a process termed delay or temporal discounting. This rapid discounting has been observed across groups of individuals with different addictions, both substance and non-substance, in active and remitted addictions, and with respect to both drugs and money (Johnson et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2010; Petry, 2001a, b; Ross et al., 2009). From a neurobiological perspective, the selection of small immediate rewards typically activates “reward” regions like the ventral striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex whereas the selection of larger, delayed rewards activates more dorsal cortical regions (Kable and Glimcher, 2007; McClure et al., 2004). Steep temporal discounting has been associated with poor treatment outcome for addictions (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2007), may be amenable to treatment (Bickel et al., 2011), and may involve cortical and subcortical systems involved in decision-making (Bickel and Yi, 2008) (see also (Balleine et al., 2007) and related articles in the volume).

Cognitive behavioral models

Another set of approaches that has emerged with strong support from randomized trials includes cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs), which seek to help the individual recognize behavioral patterns and cognitions that maintain substance use and to learn and then implement skills and strategies to change those patterns and interrupt substance use (Dutra et al., 2008; Irvin, 1999; Magill and Ray, 2009; Tolin, in press). These approaches are based on principles of operant as well as classical conditioning, for example, seeking to heighten the individuals’ awareness of cues previously paired with substance use, reduction of exposure to such cues, and implementation of skills to be aware of and tolerate cue-induced craving. CBT approaches emphasize the development of cognitive strategies to countervail the strong drives for drugs associated with conditioned cravings, as well as to fortify behavioral controls through learning to employ alternative coping mechanisms or to seek and value alternative, socially sanctioned rewards that are incompatible with drug abuse. CBT approaches appear to have particularly durable effects in that substance use often continues to decrease even after CBT treatment concludes, so-called “sleeper effects” (Carroll et al., 1994).

As with other behavioral therapies, the neural mechanisms underlying CBT remain poorly understood and, in comparison to brief motivational interventions and contingency management, may be particularly complex given the multi-faceted nature of CBT. For example, CBT typically consists of multiple sessions or modules, with each having a specific focus (Carroll, 1998; Petry, 2005). Accordingly, different modules may preferentially induce changes in specific neural circuits. For example, modules that teach coping strategies for managing cravings may specifically influence or involve brain regions implicated in cue-induced drug craving (e.g., medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices in cocaine dependence (Childress, 1999; Wexler, 2001)) and/or work through altering functional connectivity within brain circuits related to craving. Consistent with this notion, an fMRI study investigating cue-induced craving and using instructions based on CBT cognitive strategies to focus on long-term consequences of tobacco use rather than short-term pleasurable tobacco associations found that dorsolateral prefrontal cortical regions exerted control over ventral striatal activation in the regulation of craving (Kober et al., 2010). These findings are reminiscent of a study of tobacco smokers who were exposed to tobacco cues in an emotional Stroop task and received a combination of behavioral therapy and nicotine replacement (Janes et al., 2010). Individuals who showed greater functional connectivity between prefrontal cortical regions and brain areas involved in craving and interoceptive processing (anterior cingulate cortex and insula) demonstrated greater success in treatment (Janes et al., 2010).

Other aspects of CBT may involve the recruitment and strengthening of other circuits. For example, consider the learning of alternate coping strategies. Training on a visual perception learning task led to strengthened connectivity of circuitry involved in spatial attention, and these changes were observed in brain activity during rest (Lewis et al., 2009). Restful waking brain activity has been termed the default mode network, and although changes in default mode processing have been proposed to underlie both effective behavioral and pharmacological treatment of nicotine dependence (Costello et al., 2010), the relationship between default mode processing and learning changes in CBT has not been examined.

Other CBT modules (for example, those relating to financial management in pathological gambling) may more closely involve neurocircuitry implicated in the processing of monetary rewards or financial decision-making (Kable and Glimcher, 2007; Knutson and Greer, 2008). As individuals with addictions typically differ from control subjects in the function of such circuitry (Tanabe et al., 2007; Wrase et al., 2007), it is tempting to speculate that effective CBT might “normalize” these circuits and that such normalization would be related to completion of the corresponding CBT module. CBT-related changes over a longer time period, including ‘sleeper effects’, may involve circuitry underlying cognitive function and affective control, as has been observed with CBT in other disorders like depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Goldapple, 2004; Ritchey et al., 2010; Saxena et al., 2009; Siegle et al., 2006).

The future of behavioral therapies

Several novel approaches to achieving recovery from addictions are receiving empirical support, and in some cases these may complement existing strategies through more efficient targeting of cognitive, emotional and behavioral domains or deficits, as well as their neural correlates. Novel cognitive remediation strategies, aimed at strengthening brain function, may have potential in addiction treatment. Cognitive remediation strategies involve repeated intensive exposure to computerized exercises intended to strengthen memory, attention, planning and other aspects of executive functioning. Given its novelty, this approach has promise and is consistent with adult neuroplasticity (Ersche and Sahakian, 2007) and findings in non-addicted populations. For example, cognitive remediation strategies improve not only neurocognitive functioning in individuals with schizophrenia, but also their general social and occupational functioning (Bell et al., 2001). Specifically, measures of neurocognition (assessing attention, memory and problem-solving) and measures of social cognition and adjustment were improved over a two-year period (Hogarty et al., 2004). There is preliminary evidence that computerized cognitive remediation improves cognitive functioning in substance users with neuropsychological deficits and also improves treatment engagement and outcome (Bickel et al., 2011; Grohman et al., 2006; Wexler, 2011). For example, working memory training was found to reduce impulsive choice measures of temporal discounting in substance abusers (Bickel et al., 2011). The extent to which such changes reflect increased top-down control through enhanced prefrontal cortical function requires direct investigation.

Other approaches receiving empirical support in addictions treatment are mindfulness-based therapies. Based in part on Buddhist tenets and practices, mindfulness-based therapies have been developed to target stress and negative mood states in depression and examined in preliminary studies of addictions (Brewer et al., 2010). Compared with CBT, mindfulness training demonstrated comparably efficacy on measures of retention and abstinence and was more effective in diminishing subjective and biological stress responsiveness (self-reported anxiety following personalized stress exposure and sympathetic/vagal ratios, respectively) (Brewer et al., 2009). These findings suggest that mindfulness-based therapies may be particularly helpful in targeting negative reinforcement processes, like stress-induced cravings, in addictions, and this may be of particular relevance to relapse prevention as stress-induced cravings measures predict relapse (Sinha et al., 2006). Given the neurobiology of stress responsiveness and increased cortico-striato-limbic activations to stress in addicted individuals (Koob and Zorrilla, 2010; Sinha, 2008), it is tempting to speculate that mindfulness-based therapies may normalize stress-related responses in addicted individuals. Mindfulness-based therapies may be particularly applicable to women, as cocaine dependent women as compared to cocaine dependent men demonstrate relatively increased cortico-striato-limbic activations to stress cues (Potenza et al., 2007). Changes related to mindfulness-based therapies may involve white matter changes in brain regions implicated in emotional regulation and cognitive control as meditation, a component of mindfulness-based therapies, has been reported to induce white matter integrity changes in the corona radiata, a tract connecting the anterior cingulate cortex to other brain structures (Tang et al., 2010).

Additional behavioral therapeutic advances might be gleaned from considering approaches to non-substance addictions. For example, imaginal desensitization has shown some efficacy in the treatment of pathological gambling (Brewer et al., 2008b; Grant et al., 2009), and this approach of controlled exposure to gambling-related cues may help uncouple cues from engagement in addictive behaviors, and thus might be anticipated to influence prefrontal control over motivation (George and Koob, 2010). Participation in 12-step programs (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous) may also induce specific neuroadaptations. Like CBT, 12-step programs have multiple components (steps) (Anonymous, 1986), and these may be differentially linked to specific brain circuits. For example, step eight involves a willingness to make amends to those harmed, and performing such behaviors may involve changes neurocircuitry implicated in social reciprocity and moral decision-making (Moll et al., 2005; Potenza, 2009a). Although 12-step program is not a behavioral therapy per se, many individuals receiving formal treatment for addictions also attend 12-step programs. Thus, considering the contributions of 12-step participation to treatment outcome and corresponding changes in neurocircuitry is important.

Pharmacological Treatments and Targets

Multiple pharmacological targets have been identified for the treatment of addictive disorders. “Classic” approaches tend to target the drug “reward” system, such as normalization of function through agonist approaches and negative reinforcement strategies. These approaches are informed by study of neurotransmitters affected by substances of abuse (Koob and Volkow, 2010; Reissner and Kalivas, 2010; Sulzer, in press), with recent approaches emphasizing the targeting of individual vulnerabilities and cognitive function (George and Koob, 2010).

Medications targeting positive reinforcement or drug reward

Positive reinforcement is defined as any stimulus that increases the probability of the preceding behavior, and typically involves a hedonic reward. Self-administration is the primary measure for drug reinforcement, and almost all reinforcing drugs induce subjective drug reward or “liking” in humans. The exact function of dopamine in addictive behavior continues to be debated (Dalley and Everitt, 2009; Kenny, in press; Lajtha and Sershen, 2010; Schultz, 2010, in press). According to Robinson and Berridge, dopamine mainly mediates incentive-salience or “wanting” while drug pleasure or “liking” is mediated by other neurotransmitters including endogenous opioids, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and endocannabinoids (Berridge et al., 2009; Horder et al., 2010; Robinson and Berridge, 1993). The hypothesis is supported by a human PET imaging study in which dopamine release by amphetamine was correlated with drug “wanting” but not with mood elevation (Leyton et al., 2002). In addition, acute phenylalanine–tyrosine depletion, which reduces the precursor levels for dopamine, resulted in attenuated cue and cocaine-induced drug craving but not euphoria or self-administration of cocaine (Leyton et al., 2005). Further, dopamine receptor antagonists do not consistently block cocaine-induced “high” in humans (Brauer and De Wit, 1997; Haney et al., 2001). Additional support also comes from the food literature where differences in dopamine-related neural responses to highly versus less palatable foods are observed (Kenny, in press). These clinical as well as other preclinical findings (Berridge et al., 2009) provide indirect evidence for a limited role of dopamine for drug “liking.” Identifying the neurotransmitter mechanism that mediate drug “wanting” and “liking” responses may facilitate development of new pharmacotherapy targets for addictive disorders.

1. Agonist approaches

Agonist medications have their main impact on the same types of neurotransmitter receptors as those stimulated by abused substances. The general strategy of agonist treatments is to substitute a safer, more long-acting drug for a more risky, short acting one. Examples of agonist treatment include methadone for opioid dependence and nicotine replacement treatment for smoking cessation (Table 1). Agonist treatment approaches have also been examined for cocaine dependence (Herin et al., 2010). Most notably, dextroamphetamine has reduced drug use in short-term clinical trials in cocaine (Grabowski et al., 2004; Shearer et al., 2003) and methamphetamine users (Longo et al., 2010; Shearer et al., 2001). Amphetamines, similar to cocaine, increase synaptic dopamine levels by inhibiting monoamine transporters and also by disrupting the storage of dopamine in intracellular vesicles (Partilla et al., 2006; Sulzer, in press). The long-term safety and abuse liability of amphetamines as a treatment for cocaine addiction remain to be determined.

Table 1.

Pharmacotherapies used for the treatment of addictive disorders

| Medication | Delivery System | Mechanism of action | Type of Addiction |

Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methadone | Oral solution or tablet | μ-opioid agonist | Opioid | Effective in retaining patients in treatment and reducing heroin use (Mattick et al., 2009) |

| Buprenorphine | Sublingual tablet alone or with naltrexone | Partial μ-opioid agonist and k-opioid antagonist | Opioid | Effective in retaining patients and reducing heroin use (Mattick et al., 2008) |

| Naltrexone | Oral tablet, Extended-release injectable suspension | Opioid antagonist | Opioid | Better opioid use outcomes in high retention groups (Johansson et al., 2006) |

| Alcohol | Significantly reduces relapses but not to drinking (Srisurapanont and Jarusuraisin, 2005) | |||

| Disulfiram | Oral tablet | Increases acetaldehyde by inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase | Alcohol | May reduce drinking in compliant patients. |

| Overall efficacy is questionable (Mann, 2004) | ||||

| Acamprosate | Oral tablet | NMDA receptor modulator | Alcohol | Two-fold increase in abstinence rates at 1 year (Mason and Heyser, 2010) |

| Nicotine Replacement Treatments | Transdermal patch, gum, lozenge, nasal spray, and oral inhaler | nAChR agonist | Nicotine | Two-fold increase in the odds of quitting smoking (Fiore et al., 2008) |

| Bupropion | Oral tablet | DA and NE reuptake blocker, and nAChR antagonist | Nicotine | Two-fold increase in the odds of quitting smoking (Eisenberg et al., 2008) |

| Varenicline | Oral tablet | Partial agonist for the α4β2 and full agonist for the α7 nAChR | Nicotine | 2- to 3-fold increase in the odds of quitting smoking at 6 months (Cahill et al., 2010) |

Abbreviations For Table 1: DA: dopamine; nAChR: nicotinic cholinergic receptor; NE: norepinephrine; NMDA: n-methyl-d-aspartate.

Another example of agonist approach for cocaine dependence is modafinil, which has stimulant-like effects. Modafinil is a weak dopamine transporter inhibitor and increases synaptic dopamine levels (Volkow et al., 2009). It also stimulates hypothalamic orexin neurons, reduces GABA release, and increases glutamate release (Martinez-Raga et al., 2008). While initial randomized clinical trials with modafinil were promising for cocaine addiction (Dackis et al., 2005), a multi-site clinical trial was negative (Anderson et al., 2009). However, modafinil may act as a cognitive enhancing agent in stimulant-dependent individuals, improving learning through neural regions (insula and ventromedial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices) implicated in learning and cognitive control (Ghahremani et al., in press).

2. Antagonist approaches

Antagonists block the effects of drugs by either pharmacological or pharmacokinetic mechanisms. Antagonist treatment approach has been especially useful for opioid drugs. An example of pharmacological antagonism is blockage of opioid effects by μ-opioid antagonist naltrexone or buprenorphine, a partial μ-opioid agonist and k-opioid antagonist. Buprenorphine and naltrexone block the rewarding effects of opioids, and are effective for the treatment for opioid addiction. Naltrexone also attenuates the rewarding effects of alcohol by presumably blocking the μ-opioid receptors (Ray et al., 2008), and this mechanism likely contributes to naltrexone’e efficacy for the treatment of alcohol addiction (Sulzer, in press). Similarly, varenicline, a partial agonist for the alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors, attenuates the rewarding effects of nicotine (Patterson et al., 2009; Sofuoglu et al., 2009; West et al., 2008) and is effective for the treatment of nicotine dependence (Table 1).

More recently, immunotherapies have been developed for the treatment of cocaine, methamphetamine, and nicotine addictions (Orson et al., 2008). Immunotherapies antagonize drug effects via pharmacokinetic mechanisms (LeSage et al., 2006). The antibodies produced by immunotherapies sequester the drug in the circulation and reduce the speed at which, and the amount of, drug that is reaching the brain. This results in attenuated rewarding effects of the drug of abuse (Haney et al., 2010). While initial clinical trials suggest some promise (Martell et al., 2005; Martell et al., 2009), to date the efficacy of vaccines has been undercut by a substantial induction period required to achieve clinically significant levels of circulating antibodies and only partial blockade of drug effects even when antibody levels are maximized. An important limitation of vaccines is that the antibodies produced are specific for a given drug of abuse, a characteristic that will limit their clinical efficacy in poly-drug abusers. The most promising use of vaccine may be to prevent relapse in individual whose drug use is limited to a single agent.

A potentially promising target for agonist and antagonist treatment of cocaine addiction is the D3 dopamine receptor (Heidbreder and Newman, 2010). Like the D2 dopamine receptor, the D3 dopamine receptor is expressed at high levels in the striatum, but compared to the D2 dopamine receptor, it is particularly highly expressed in the ventral striatum. While D3 agonists partially reproduce cocaine reinforcement, D3 antagonists or partial agonists attenuate cocaine reinforcement (Achat-Mendes et al., 2010). D3 partial agonists (CJB090, BP 897 and others) can act like agonists and stimulate dopamine receptors when endogenous levels of dopamine are low, as in cocaine withdrawal. In contrast, when dopamine receptors are stimulated following cocaine use, D3 partial agonists can act like antagonists in blocking the effects of cocaine (Martelle et al., 2007). However, drugs with D2 and D3 antagonistic properties have not demonstrated clinical efficacy for drug or non-substance addictions (Fong et al., 2008), D2/D3 antagonists have been associated with promoting of gambling-related motivations in pathological gambling (Zack and Poulos, 2007), and dopamine agonists (including D3-preferring drugs) have been associated with non-substance addictions like pathological gambling in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (Weintraub et al., 2010). As such, the efficacies and tolerabilities of D3 partial agonists need careful examination in people with addictions. Additionally, drugs that target striatal dopamine function through indirect manners (e.g., through serotonin 1B receptors) also warrant consideration for treatment development (Hu et al., 2010).

3. Medications targeting negative reinforcement of drugs

Drug addiction is associated with adaptive changes in multiple neurotransmitter systems in the brain including dopamine, norepinephrine, corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH), GABA, and glutamate (Chen et al., 2010; Koob and Le Moal, 2005). These adaptive changes are thought to underlie the negative reinforcing effects of abstinence from drug use that are clinically observed as withdrawal symptoms, craving for drug use, and negative mood states like anhedonia and anxiety. Increased norepinephrine activity is associated especially with opioid and alcohol withdrawal states. Development of sensitization to drug-related cues, perceived as craving induced by drug cues, likely involve adaptive changes in the dopamine, GABA, and glutamate systems (Schmidt and Pierce, 2010). Reduction in dopamine levels in the “reward” circuit is thought to mediate anhedonia commonly observed following abstinence from drugs (Treadway and Zald, 2010). Examples of medications targeting negative reinforcement of drugs include methadone or buprenorphine, drugs which relieve opioid withdrawal symptoms. Nicotine replacement products, bupropion, and the partial nicotinic agonist varenicline relieve nicotine withdrawal symptoms and attenuate the negative mood states following smoking cessation (Patterson et al., 2009; Sofuoglu et al., 2009). Acamprosate, an approved medication for the treatment of alcohol dependence, attenuates withdrawal symptoms and craving for alcohol (Gual and Lehert, 2001).

Medications targeting the noradrenergic system have shown promising results for treatments targeting withdrawal or relapse. Preclinical and human laboratory studies suggest that lofexidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist, may attenuate stress-induced relapse in cocaine and opioid users (Highfield et al., 2001; Sinha et al., 2007). Cocaine users with more severe withdrawal symptoms respond more favorably to propranolol, a beta-adrenergic antagonist (Kampman et al., 2006). Clinical trials are underway to test the efficacies of carvedilol, an alpha and beta-adrenergic antagonist, and guanfacine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist, in treating cocaine or methamphetamine addiction.

Several agents targeting glutamate system are also under investigation as potential treatment medications. Memantine, a non-competitive n-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor antagonist has also shown efficacy in reducing cue-induced craving for alcohol in alcohol dependent patients (Krupitsky et al., 2007). In pathological gambling, memantine may be efficacious and operate by reducing cognitive measures of compulsivity (Grant et al., 2010a). However, clinical trials with memantine have demonstrated negative findings for alcohol (Evans et al., 2007) and cocaine dependence (Bisaga et al., 2010). A neutraceutical that targets the glutamate system is N-acetyl cysteine, a natural compound used for the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. N-acetyl cysteine’s proposed anti-addictive effects include normalization of reduced extracellular glutamate levels in nucleus accumbens by stimulating the cystine–glutamate antiporter (Baker et al., 2003). N-acetyl cysteine has shown some positive results in small clinical trials for cocaine and nicotine addiction and pathological gambling (Grant et al., 2007; Knackstedt et al., 2009; Mardikian et al., 2007). Larger studies are underway to test its efficacy in these disorders. In addition, compounds targeting metabotropic glutamate receptors have shown efficacy in blocking reinstatement of drug use behavior in animal models for relapse. For example, LY379268, an agonist of the group II metabotropic glutamate receptors, reduces self-administration and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior for nicotine (Liechti et al., 2007), alcohol (Sidhpura et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2006), and cocaine (Adewale et al., 2006; Baptista et al., 2004). Several metabotropic glutamate agonists are available for human use and should be evaluated for the treatment of addictive disorders.

Medications targeting individual vulnerability factors to addiction

Individuals vary in their vulnerability to addiction. For example, among those who had tried cocaine, only about 17% become addicted (Wagner, 2002). For alcohol, about 15% of those who drink eventually become dependent, while 30 % of those who try smoking become addicted smokers. These proportions are similar to those observed in pre-clinical models of addiction (Belin et al., 2008). The individual factors contributing to vulnerability to addiction are complex and have not yet been fully elucidated (George and Koob, 2010; Kreek et al., 2005; Le Moal, 2009; Sinha, 2008; Uhl et al., 2009). Comorbid psychiatric conditions and cognitive deficits are two examples individual vulnerability factors that could be targeted by pharmacotherapies.

1. Treatments targeting comorbid psychiatric conditions

Comorbidity exists between drug addiction and primary psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, mood and anxiety disorders, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Hasin et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 2005). For example, among individuals with schizophrenia, 40 to 60 percent abuse drugs or alcohol and over 90 percent smoke cigarettes (George, 2002). Addicted individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders tend to have poorer outcomes than those without comorbidity (Brady and Sinha, 2005; Havassy et al., 2004; Potenza, 2007). One of the possible mechanisms underlying this high comorbidity is self-medication, which posits that individual with primary psychiatric disorders use drugs or alcohol to relieve specific symptoms (e.g., negative affect) or side effects of their treatment medications (e.g., sedation). Alternatively, common genetic and other neurobiolgical factors may lead to high comorbidity between drug addictions and other psychiatric disorders (Chambers, 2001; Potenza et al., 2005). Common vulnerability factors may include increased impulsivity, reward sensitivity, and cognitive deficits. One implication of comorbidity is that effective treatment of psychiatric disorders may also reduce substance use, although existing clinical trials indicate mixed results in this regard (Nunes and Levin, 2004).

2. Medications targeting cognitive deficits

A large body of evidence has documented cognitive deficits in chronic alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine, and cannabis users (Ersche et al., 2006; Ersche and Sahakian, 2007; Goldstein and Volkow, 2002). Cognitive deficits may represent a particular challenge for treatment-seeking users who require intact cognitive functioning in order to engage in treatment and learn new behavioral strategies in order to stop their drug use. As demonstrated previously, cognitive deficits are associated with higher rates of attrition and poor treatment outcome (Aharonovich et al., 2006; Bates et al., 2006). Cognitive enhancement strategies may be especially important early in the treatment by improving their ability to learn, remember, and implement new skills and coping strategies. The range of deficits that is found in addicted individuals includes attention, working memory, and response inhibition, functions that are attributed to the prefrontal cortex. Cognitive functioning in the prefrontal cortex is modulated by many neurotransmitters, including glutamate, GABA, acetylcholine, and monoamines: dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine (Robbins and Arnsten, 2009). Many cognitive enhancers targeting these neurotransmitters are in different stages of development.

In a recent proof-of-concept study, we examined the efficacy of galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, as a cognitive enhancer in abstinent cocaine users (Sofuoglu et al., 2011). Cholinesterase inhibitors, including tacrine, rivastigmine, donepezil, and galantamine, have been used for the treatment of dementia and other disorders characterized by cognitive impairment, including Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, and schizophrenia (Giacobini, 2004). Cholinesterase inhibitors increase the synaptic concentrations of acetylcholine (ACh), which leads to increased stimulation of both nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Galantamine is also an allosteric modulator of the α7 and α4β2 nicotinic ACh receptor (nAChR) subtypes ((Schilström et al., 2007). In our study, 10-day treatment with galantamine, compared to placebo, improved the attention and working memory functions in abstinent cocaine users (Sofuoglu et al., 2011). These findings support the promise of galantamine as a cognitive enhancer among cocaine users. This study did not examine treatment effect on cocaine use because participants had to be abstinent of drug use to allow accurate assessment of galantamine on cognitive performance. Additional clinical trials are underway to test the efficacy of galantamine in the treatment of cocaine-addicted individuals.

Another promising medication for cognitive enhancement is atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine transporter (NET) inhibitor used for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In prefrontal cortex, the NET is responsible for the reuptake of norepinephrine as well as dopamine into presynaptic nerve terminals (Kim et al., 2006). As a result, atomoxetine increases both NE and dopamine levels in the PFC, and both actions may contribute to the cognitive-enhancing effects of atomoxetine (Bymaster, 2002). Consistent with preclinical studies (Jentsch et al., 2009; Seu et al., 2009), atomoxetine improves attention and response inhibition functions in healthy controls and patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Chamberlain et al., 2007; Chamberlain et al., 2009; Faraone et al., 2005). Attention and response inhibition functions are essential in optimum cognitive control needed to prevent drug use, and atomoxetine in preclinical models diminished drug-seeking behaviors (Economidou et al., 2011). Both attention and response inhibition are impaired in cocaine users (Li et al., 2006; Monterosso et al., 2005). Whether these cognitive functions can be improved and drug use curtailed with atomoxetine remains to be determined in cocaine users.

In addition to cholinesterase inhibitors and atomoxetine, there are many other potential cognitive enhancers include modafinil, amphetamines, partial nAChR agonists, like varenicline, and metabotropic glutamate agonists (Olive, 2010). The safety and efficacy of these medications remain to be tested in clinical studies with addicted individuals.

Combined behavioral and pharmacological treatment approaches

While great progress has been made in identification of effective pharmacotherapies and behavioral therapies for the addictions, no existing treatment, delivered alone, is completely effective (Carroll and Onken, 2005; Vocci et al., 2005). Thus, an important strategy to enhance the efficacy of monotherapies is to combine them with one or more alternative treatments (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2007). The results of combined treatments can be additive, interactive, non-additive (adding a second treatment neither adds nor subtracts) or subtractive. Strategies for choosing treatments to combine include (1) use of complementary efficacious treatments that address weakness in either therapy alone, (2) use of efficacious treatments that target the same processes in different ways and (3) use of treatments that are not efficacious alone but catalyze each other. Frequently, these strategies involve combining a top-down approach with a bottom-up intervention, such as combinations of behavioral and pharmacotherapies (Figure 1).

There are multiple examples of behavioral and pharmacological treatments having complementary effects. A classic example is the combination of methadone maintenance with behavioral therapies (McLellan, 1993; Peirce et al., 2006). Without behavioral treatments, provision of methadone was associated with early treatment failure and dropout (Ball and Ross, 1991). Another example of this strategy involves antidepressant medications and cognitive behavioral therapy, each of which has been demonstrated to reduce depression in depressed smokers (Hall et al., 2002). Antidepressants are targeted at neurotransmitter systems thought to underlie depression symptoms while CBT attempts to change behaviors and cognitions associated with maintaining depression (DeRubeis et al., 1999; DeRubeis et al., 2008). An example of catalytic, or synergistic treatment effects is provided by studies which combine contingency management with tricyclic antidepressants for cocaine abuse in methadone maintained patients (Kosten, 2003; Poling, 2006). In both of these trials, neither tricyclics nor contingency management were efficacious alone but the combination yielded superior results compared to a standard treatment condition. Behavioral therapies may also work in a complementary fashion, particularly in different stages of treatment. For example, motivational interventions may help engage individuals in treatment, contingency management may help maintain individuals in treatment, and CBT may help with long-term abstinence through relapse prevention and “sleeper effects.” Although not linked to a specific therapy, there are data to suggest that these different aspects of treatment outcome are differentially associated with specific neural circuits. For example, in cocaine dependent individuals, pre-treatment fMRI measures of cognitive control were differentially associated with outcome measures of retention and abstinence, with retention correlating with activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (implicated in executive functioning) and abstinence with activation in striatal and ventromedial prefrontal cortical regions (implicated in reward processing and decision-making) (Brewer et al., 2008a). As this study involved a small sample of subjects receiving combinations of behavioral and pharmacological therapies, additional larger controlled studies involving pre- and post-treatment imaging are needed to assess more directly the relationships between specific treatments, outcome measures and neural functions.

Although it is tempting to speculate that specific combinations of treatments (e.g., behavioral and pharmacological therapies that theoretically engage top-down processes and bottom-up processes, respectively (Figure 1)) may have complementary mechanisms of action, the precise mechanisms for synergism between behavioral and pharmacotherapies are not well understood and require direct investigation. Existing data offer some insight. For example, consistent with the notion of pharmacotherapies working in a bottom-up fashion, bupropion treatment of tobacco smokers was associated with less craving and diminished limbic activation to smoking cues when attempting to resist craving, whereas placebo treatment did not demonstrate changes in limbic activations (Culbertson et al., 2011). However, in a study of tobacco smokers receiving treatment with bupropion, practical group counseling, or pill placebo, individuals receiving either active treatment differed from those receiving placebo by showing greater reduction in glucose metabolism post-treatment in the posterior cingulate cortex (Costello et al., 2010). The decreased metabolism was not related to cigarette use measures and appeared largely similar across the behavioral and pharmacological therapies. As the posterior cingulate is an integral component of the default mode network, the authors speculated that effective treatments for nicotine dependence may improve default mode network functioning, moving individuals towards better goal-oriented states (Costello et al., 2010). As children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder show suppression of default mode processing in response to stimulant treatment (Peterson et al., 2009), the findings suggest that improved default mode processing function may represent an important treatment target across disorders characterized by impaired impulse control. Moreover, as posterior cingulate activation during drug craving has been associated with treatment outcome for cocaine dependence (Kosten et al., 2006), the findings also suggest an important role for posterior cingulate function for treatment outcome across addictions, and one that may also relate to the involvement of the posterior cingulate in circuits related to emotional and motivational processing (Sinha, 2008). Such possibilities warrant direct examination.

Using Neuroscience to Investigate Treatment Mechanisms

As reviewed above, traditional pharmacologic approaches to addiction have focused on exploiting our understanding of the specific actions of various neurotransmitters in the brain (e.g., dopamine for reward, opioids for pleasure, and adrenergic neurochemicals for excitement) (Potenza, 2008). While continuing to increase our understanding of the neurochemical underpinnings of addictions remains important (particularly for pharmacotherapy development), approaches to understanding brain function related to addictions are increasingly focusing on neural systems in the pathophysiologies of addictions. Thus, incorporating pre- and post-treatment neuroimaging measures into randomized clinical trials for addictions is particularly important if we are to identify neural predictors and correlates of effective treatments for these disorders.

There exist multiple considerations when integrating neuroimaging and clinical trials for addictions. While some are practical (e.g., a relatively short time frame between evaluation/randomization and scanning requiring coordination between an interdisciplinary research team, questions as to how best to manage and consider recency of drug use (and potentially intoxication or withdrawal) with respect to scanning), others are theoretical (e.g., selecting measures that are theoretically related to the therapies’ proposed mechanisms of action, a notion consistent with selecting evaluative measures in clinical trials in general (Walker, 2006)). An important advantage of fMRI in this respect is the ability to monitor brain activity (via blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal) during task performance. As such, specific fMRI paradigms may offer particular insights into the mechanisms of action of particular therapies. For example, effective contingency management, involving the delivery of small immediate rewards based on positive short-term behaviors (e.g., drug abstinence) may be expected to involve changes in reward processing that can be assessed through fMRI paradigms like the monetary incentive delay task(Andrews et al., 2010). Alternatively, specific aspects of CBT, such as developing skills to cope with drug cues or triggers, might involve changes in brain circuitry underlying regulation of craving or cognitive control that may be assessed through different fMRI paradigms (Brewer et al., 2008a; Janes et al., 2010; Kober et al., 2010). Other fMRI paradigms (e.g., those probing stress responsiveness) may be particularly well suited for investigating mechanisms underlying mindfulness-based therapies (Brewer et al., 2009; Sinha et al., 2005). Additionally, advances in fMRI technology that facilitate real-time feedback of regional brain activation may be used to investigate features relevant to specific therapies (e.g., control of craving in CBT and meditational states in mindfulness-based therapies) (deCharms, 2008).

Conversely, novel methods of treatment delivery, such as computer-assisted delivery of CBT (Carroll et al., 2008; Carroll, 2009), may facilitate understanding of treatment mechanisms through neuroimaging studies. Given the consistency with which it is delivered, computerized treatment offers a more robust and standardized form of treatment. The consequent reduction in variance in the treatment variable may increase the power of fMRI paradigms to detect processes that are specific to this form of treatment, offering an advantage in small-sample fMRI studies (Frewen, 2008). Also, components of computer-delivered treatments could conceivably be studied directly using fMRI.

Future Directions: Individual Differences, Endophenotypes, and Treatment Matching

One current focus in optimizing treatment involves identifying individual differences related to addiction treatment outcome to guide the selection of therapies. While the consideration of individual differences is not new (e.g., Project MATCH investigated individual differences and treatment specificity with arguably limited success (Cutler and Fishbein, 2005)), recent approaches have considered individual differences from a different perspective (e.g., as possible endophenotypes (Gottesman, 2003)). Some individual differences may represent important targets for treatment development (e.g., potential endophenotypes like impulsivity or compulsivity (Dalley et al., in press)), whereas others (e.g., developmental stages, sex differences, stage of the addiction process) may represent important considerations when targeting or matching specific treatments to specific individuals.

Endophenotypes represent particularly attractive therapeutic targets as they may associate more closely to biological mechanisms than do heterogeneous psychiatric disorders like addictions (Fineberg et al., 2010; Gottesman, 2003). One potential endophenotype relevant to addiction treatment is impulsivity (Dalley et al., in press). Pre-clinical data indicate that impulsive tendencies prior to drug exposure both are linked to ventral striatal dopamine function and predict the development of addictive behaviors (Belin et al., 2008; Dalley et al., 2007). Studies also link midbrain to ventral striatal dopamine pathways to impulsivity in people (Buckholtz et al., 2010). Clinical data suggest that impulsivity is associated with addiction severity, and that changes in addiction severity during treatment correlate with changes in impulsivity (Blanco et al., 2009). Thus, targeting impulsivity through behavioral or pharmacological mechanisms that promote self-control warrants consideration. As elevated impulsivity may pre-date addictive problems, such interventions may be considered at early points in either the addictive process or in development. This latter point seems particularly salient as individual differences in self-control during childhood predict important measures of functioning during adolescence and into adulthood (Lehrer, 2009; Mischel et al., 1989). Furthermore, as substance exposure during adolescence may lead to greater impulsivity in adulthood (Nasrallah et al., 2009), early intervention appears particularly important.

Targeting of specific factors may be complicated by the complexities of the constructs. For example, impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct that factors into two or more domains (Meda et al., 2009; Moeller et al., 2001). Two domains repeatedly identified include those related to choice/decision-making and response disinhibition, and each appears relevant to addiction (de Wit, 2008; Perry and Carroll, 2008; Potenza and de Wit, 2010; Reynolds et al., 2006; Verdejo-Garcıa et al., 2008). The specific domains of impulsivity may relate differentially to other relevant psychobiological processes (e.g., reward processing and cognitive control appear theoretically and biologically linked to choice and response impulsivity, respectively) and thus combinations of therapies that preferentially target each domain may be needed to optimize treatments.

As self-report and behavioral measures of impulsivity have been found to factor separately (Meda et al., 2009) and behavioral and self-reported measures of the same constructs (e.g., temporal discounting) may not correlate with one another and be differentially related to treatment outcome (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2007), a broad range of self-report, behavioral and biological assessments (including neurocognitive ones) may provide the deep phenotyping that will be vital to treatment developments for addictions. Additionally, as brain circuits underlying motivation, reward responsiveness, decision-making and behavioral control are undergoing significant changes during periods of increased addiction vulnerability such as adolescence (Casey et al., 2010; Chambers et al., 2003; Rutherford et al., 2010; Somerville et al., 2010), developmental considerations are important in this process.

Potential endophenotypes may underlie multiple kinds of addictions (Frascella et al., 2010). However, specific drugs are also associated with unique short- and long-term effects, including potential neurotoxicities. Drug exposure may have specific influences on brain structure and function, and such changes warrant particular attention as they relate to treatment development. For example, cocaine use has been associated with metabolic impairments, with increasing chronicity of use progressively influencing cortical regions from more ventral and medial regions to more dorsal and lateral ones (Beveridge et al., 2008). These findings are consistent with a broad range of cognitive deficits observed in cocaine dependent individuals, including on tasks associated with ventromedial prefrontal cortical function (Bechara, 2003) as well as ones linked to dorsolateral prefrontal cortical function and associated with treatment outcome measures of retention (Brewer et al., 2008a; Streeter et al., 2007). Other brain differences, such as white matter integrity (Lim, 2002; Lim et al., 2008; Moeller et al., 2005; Moeller et al., 2007), have been observed in cocaine dependence and associated with disadvantageous decision-making (Lane et al., 2010) and treatment outcome (Xu et al., 2010). Both pharmacological (Harsan et al., 2008; Schlaug et al., 2009) and behavioral (Tang et al., 2010) approaches may alter white matter integrity. Thus, white matter integrity may represent an under-examined therapeutic target in addictions. Additionally, investigating means for altering synaptic connections, including rapid mechanisms related to brief exposure to anti-glutamatergic drugs (Li et al., 2010), may aid addiction treatment development efforts, particularly as related to stress or other negative reinforcement processes. These considerations underscore the promise of developing and testing (both singly and in combination) pharmacological and behavioral treatments aimed at improving cognitive functions such as attention, working memory, decision-making and self-control. Relating the results of these treatments to measures of impulsivity and brain function can provide evidence for mechanisms of these treatments.

Endophenotypes may track closely with genetic factors, and individual differences related to addictions and their treatments may be influenced by genetic, environmental or interactive influences (Goldman et al., 2005; Renthal and Nestler, 2008). As commonly occurring allelic variants have been variably linked to treatment outcomes for addictions (e.g., a functional variant of the gene encoding the mu-opioid receptor has been associated with opioid antagonist treatment outcome in some (Oslin et al., 2003) but not other (Arias et al., 2008) studies of alcohol dependence or heavy drinking) and specific environmental exposures in conjunction with commonly occurring allelic variants may shift the risk for developing and treating addictions (e.g., stress exposure and serotonin-transporter-encoding genetic variants interact to influence alcohol intake in young adults and may be linked to ondansetron response in alcohol dependence (Johnson et al., 2008; Laucht et al., 2010; Sinha, 2009)), it will be important to carefully assess multiple environmental and genetic measures as related to treatment outcome. Furthermore, as timing of environmental exposures may differentially impact individuals (e.g., influences of trauma early vs. later in life) and do so in a sex- or culture-specific fashion, thorough assessments and large samples involving targeted recruitment may be necessary to optimize treatment strategies for individuals.

Drug-Related Brain Changes: Consideration of Non-substance Addictions

Given the potential neurotoxic and neuroadaptation effects of abused substances, understanding the neuroscience of addictive processes may be enhanced by focusing on addictions that do not necessarily involve use of psychoactive substances. For example, obesity shares similarities with drug addictions at neurobiological levels (e.g., with respect to striatal D2/D3 dopamine receptor function), and these similarities may inform treatment and policy strategies (Gearhardt et al., in press; VanBuskirk and Potenza, 2010). Pathological gambling also demonstrates clinical and biological similarities with drug addictions (Holden, 2010; Potenza, 2006; Potenza, 2008). Consistently, treatments, particularly those with proposed mechanisms of action (e.g., modulation of neurotransmission in the meso-limbic dopamine pathway by opioid receptor antagonists like naltrexone or nalmefene or enhancing cognitive function via glutamatergic agents like memantine) that target features observed across addictions, appear efficacious for both substance and gambling addictions (Brewer et al., 2008b; Cheon et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2010a; Potenza, 2008). Furthermore, among individuals with pathological gambling, response to an opioid receptor antagonist appears strongly related to a family history of alcoholism (Grant et al., 2008), suggesting a possible endophenotype common to pathological gambling and alcoholism. However, other features, such as executive processes involving dorsal prefrontal cortical function, appear more impaired in individuals with alcoholism than in those with gambling problems, consistent with neurotoxic influences of alcohol (Lawrence et al., 2009; Potenza, 2009b). As pathological gambling is unhindered by drug-on-brain-substrate effects that may complicate the treatment of substance addictions, it represents an important disorder for better understanding substance addictions and their treatments.

V. Summary

Although significant advances have been made over the past several decades in the development of effective treatments for addictions, they remain a substantial public health problem. The development of neuroscience methodologies for assessing brain structure and function provides an exciting opportunity for applying these tools to understand and improve treatment. Additional research efforts should define novel targets for treatment (e.g., cognitive function, control of craving, impulsivity, compulsivity and/or self-control), implement tools for assessing these targets over time (including self-report, behavioral, neurocognitive/neural measures), and identify clinically relevant individual differences that may be used to guide the selections of therapies, including combinations of therapies that may operate in complementary or synergistic fashions. As effects of drug use on brain and brain function may be a major factor underlying ability to benefit from treatment, direct investigation of drug-related influences on brain structure and function are warranted in translational and longitudinal studies. Concurrent investigation of substance and non-substance addictions should be especially informative.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants P50-DA09241, P50-DA016556, P20-DA027844, R37-DA015969, K02-DA021304, R01-DA020908, RC1-DA028279, R01-DA018647, R21 DA029445, and R01-DA019039, the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse grant RL1-AA017539, the VISN 1 Mental Illness Educational, Research, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), and a Center of Excellence in Gambling Research from the National Center for Responsible Gaming.

Dr. Potenza has received financial support or compensation for the following: Dr. Potenza has consulted for and advised Boehringer Ingelheim; has consulted for and has financial interests in Somaxon; has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Veteran’s Administration, Mohegan Sun Casino, the National Center for Responsible Gaming and its affiliated Institute for Research on Gambling Disorders, and Forest Laboratories, Ortho-McNeil, Oy-Control/Biotie and Glaxo-SmithKline pharmaceuticals; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders or other health topics; has consulted for law offices and the federal public defender’s office in issues related to impulse control disorders; provides clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program; has performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; has guest-edited journal sections; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors report that they have no financial conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript.

References

- Achat-Mendes C, Grundt P, Cao J, Platt DM, Newman AH, Spealman RD. Dopamine D3 and D2 receptor mechanisms in the abuse-related behavioral effects of cocaine: studies with preferential antagonists in squirrel monkeys. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2010;334:556–565. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.167619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adewale AS, Platt DM, Spealman RD. Pharmacological stimulation of group ii metabotropic glutamate receptors reduces cocaine self-administration and cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in squirrel monkeys. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2006;318:922–931. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, Liu X, Bisaga A, Nunes EV. Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD, DeLong MR. Basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: Parallel substrates for motor, oculomotor, "prefrontal" and "limbic" functions. Prog Brain Res. 1990;85:119–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, Delong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Reid MS, Li SH, Holmes T, Shemanski L, Slee A, Smith EV, Kahn R, Chiang N, Vocci F, et al. Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;104:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews MM, Meda SA, Thomas AD, Potenza MN, Krystal JH, Worhunsky P, Stevens MC, O’Malley SS, Book GA, Pearlson GD. Individuals Family History Positive for Alcoholism Show fMRI Abnormalities in Reward Sensitivity that are Related to Impulsivity Factors. Biol Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.049. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous A. Twelve steps and twelve traditions. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc.; 1986. Vol 32nd Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Arias AJ, Armeli S, Gelernter J, Covault J, Kallio A, Karhuvaara S, Koivisto T, Mäkelä R, Kranzler HR. Effects of opioid receptor gene variation on targeted nalmefene treatment in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Expt Res. 2008;32:1159–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, Shen H, Toda S, Kalivas PW. N-acetyl cysteine-induced blockade of cocaine-induced reinstatement. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1003:349–351. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball JC, Ross A. The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Doya K, O'Doherty J, Sakagami M. Introduction: Current trends in decision-making. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1104:xi–xv. doi: 10.1196/annals.1390.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista MA, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Preferential effects of the metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 on conditioned reinstatement versus primary reinforcement: comparison between cocaine and a potent conventional reinforcer. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:4723–4727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0176-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates ME, Pawlak AP, Tonigan JS, Buckman JF. Cognitive impairment influences drinking outcome by altering therapeutic mechanisms of change. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:241–253. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Risky business: Emotion, decision-making, and addiction. J Gambling Stud. 2003;19:23–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1021223113233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science. 2008;320:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1158136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, Bryson G, Greig T, Corcoran C, Wexler BE. Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with work therapy: Effects on neuropsychological test performance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:763–768. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW. Dissecting components of reward: 'liking', 'wanting', and learning. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge TJR, Gill KE, Hanlon CA, Porrino LJ. Parallel studies of cocaine-related neural and cognitive impairment in humans and monkeys. Phil Trans Royal Soc B. 2008;363:3257–3266. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R. Temporal discounting as a measure of executive function: insights from the competing neuro-behavioral decision system hypothesis of addiction. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2008;20:289–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C. Remember the Future: Working Memory Training Decreases Delay Discounting Among Stimulant Addicts. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaga A, Aharonovich E, Cheng WY, Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Raby WN, Nunes EV. A placebo-controlled trial of memantine for cocaine dependence with high-value voucher incentives during a pre-randomization lead-in period. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2010;111:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Potenza MN, Kim SW, Ibanez A, Zaninelli R, Saiz-Ruiz J, Grant JE. A pilot study of impulsivity and compulsivity in pathological gambling. Psychiatric Res. 2009;167:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum K, Cull JG, Braverman ER, Comings DE. Reward deficiency syndrome. Am Scientist. 1996;84:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Cohen JD. Conflict Monitoring and Cognitive Control. Psychological Review. 2001;108:624–652. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]