Abstract

Concentrations of glutarate (GA) and its derivatives such as 3-hydroxyglutarate (3OHGA), D- (D-2OHGA) and L-2-hydroxyglutarate (L-2OHGA) are increased in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and urine of patients suffering from different forms of organic acidurias. It has been proposed that these derivatives cause neuronal damage in these patients, leading to dystonic and dyskinetic movement disorders. We have recently shown that these compounds are eliminated by the kidneys via the human organic anion transporters, OAT1 and OAT4, and the sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter 3, NaDC3. In neurons, where most of the damage occurs, a sodium-dependent citrate transporter, NaCT, has been identified. Therefore, we investigated the impact of GA derivatives on hNaCT by two-electrode voltage clamp and tracer uptake studies. None of these compounds induced substrate-associated currents in hNaCT-expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes nor did GA derivatives inhibit the uptake of citrate, the prototypical substrate of hNaCT. In contrast, D- and L-2OHGA, but not 3OHGA, showed affinities to NaDC3, indicating that D- and L-2OHGA impair the uptake of dicarboxylates into astrocytes thereby possibly interfering with their feeding of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates to neurons.

Introduction

Glutaric aciduria type I is caused by deficiency of the enzyme glutaryl CoA-dehydrogenase (GCDH) in the metabolic pathway of lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan, leading to an accumulation of glutaric acid (GA) and its derivative 3-hydroxy glutaric acid (3OHGA) (Funk et al. 2005; Harting et al. 2009; Hedlund et al. 2006; Strauss et al. 2010) in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and urine. 2-Hydoxyglutaric (2OHGA) acidurias are characterized by the presence of elevated concentrations of either L-2OHGA or its enantiomer D-2OHGA and of α-ketoglutarate (αKG) in body fluids (Read et al. 2005; Seiijo-Martinez et al. 2005; Struys 2006; Struys et al. 2007). Whereas L-2OHGA aciduria is caused by mutations of the FAD-dependent L-2OHGA dehydrogenase (Rzem et al. 2004), the underlying metabolic defects of D-2OHGA aciduria are due to mutations of the enzyme D-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (Struys et al. 2005). It is assumed that all GA derivatives are neurotoxins and cause neuronal damage.

We have recently identified the sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter 3 (NaDC3) and the organic anion transporter 1 (OAT1) to be responsible for the uptake of GA and its derivatives from the blood into renal proximal tubular cells (Hagos et al. 2008; Mühlhausen et al. 2008). Both transporters are also present in the human brain (Alebouyeh et al. 2003; Bleasby et al. 2006). Whereas OAT1 is involved in the efflux of various neurotransmitter metabolites from the cerebrospinal fluid to the blood across the choroid plexus (Alebouyeh et al. 2003), NaDC3 is restricted to astrocytes (Yodoya et al. 2006) and possibly the choroid plexus (Pajor et al. 2001). Besides NaDC3, another electrogenic sodium-dependent di- or tricarboxylate transporter, hNaCT, has been identified in the brain. NaCT is preferentially located in neurons, especially in the hippocampus, cerebellum, cerebral cortex and olfactory bulb (Inoue et al. 2002a, b; Wada et al. 2006; Yodoya et al. 2006). Since neuropathological findings observed in patients suffering from glutaric aciduria type 1 as well as from D- and L-2OHGA aciduria occur in neurons, we investigated the impact of GA derivatives on hNaCT expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes.

Materials and methods

In vitro transcription of hNaCT- and hNaDC3-cRNA

Capped cRNA from the human NaCT (GenBank Accession No. AY151833) and human NaDC3 (GenBank Accession No. AF154121) was used as a template for cRNA synthesis. Plasmids were linearized with Not I and in vitro cRNA transcription was performed using the T7 mMessage mMaschine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufactor’s instructions. The resulting cRNA was suspended in purified, RNAse-free water to a final concentration of 1 μg/μl.

Solutions

A standard oocyte Ringer solution (ORi) was used for oocyte preparation, storage, and for the uptake as well as for the electrophysiologic measurements. ORi contained (in mM): 110 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 5 HEPES/Tris, adjusted to pH 7.5. Citrate, succinate, glutarate (GA), its derivatives, 3-hydroxyglutarate (3OHGA), D- (D-2OHGA), and L-2-hydroxyglutarate (L-2OHGA), and glutamate were added to ORi in the concentrations indicated in the figure legends and pH was adjusted to 7.5. All chemicals, including those for ORi, for oocyte preparation and storage, as well as for the uptake and electrophysiologic experiments were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). 3OHGA was obtained from C. Mühlhausen (UKE, Hamburg, Germany).

Oocyte preparation and storage

Stage V and VI oocytes from Xenopus laevis (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI, USA) were separated by an overnight treatment with collagenase (Typ CLS II; Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), subsequent washings in calcium-free ORi and maintained at 16–18°C in ORi containing a calcium concentration of 2 mM. One day after removal from the frog, oocytes were injected with 23 nl cRNA coding either for hNaCT or hNaDC3, or an equivalent amount of water (mocks) and maintained at 16–18°C in ORi supplemented with 50 μM gentamycin and 2.5 mM sodium pyruvate. After 3–4 days of incubation with daily medium changes, oocytes were used for tracer uptake studies.

Transport experiments

Uptake of [14C]citrate (14C[1,5]citric acid; GE Health Care, Freiburg, Germany) or [14C]glutarate (14C[1,5]glutaric acid; MP Biomedicals, Heidelberg, Germany) in hNaCT- or of [14C]succinate (14C[2,3]succinic acid; Perkin Elmer, Rodgau, Germany) in hNaDC3-expressing oocytes was assayed at room temperature. Inhibition of citrate uptake was determined by simultaneous application of 12 μM 14C-citrate and ORi containing 1 mM of GA, 3OHGA, D- or L-2OHGA, respectively, for 30 min. 14C-glutarate was used at a concentration of 20 μM. Inhibition of succinate uptake was determined by simultaneous application of 18 μM 14C-succinate plus 40 μM sodium succinate and ORi containing 1 mM glutamate. After incubation in the respective solutions, radioactivity was aspirated and the oocytes were washed twice in ice-cold ORi. Oocytes were dissolved by gently shaking for 2 h in 100 μl 1 N NaOH, neutralized with 100 μl 1 N HCl, and their 14C-contents were determined by liquid scintillation counting (Tricarb 2900TR; Perkin Elmer). Mocks were treated in a similar manner to serve as controls. Inhibition experiments were performed at least in duplicate with 8–10 oocytes for each experimental condition.

Electrophysiologic analysis

These studies were carried out 3–4 days after cRNA injection at room temperature. Oocytes were placed into a 0.5-ml chamber on the stage of a microscope and impaled under direct view with borosilicate glass microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl (BioMedical Instruments, Zöllnitz, Germany). Current-voltage (I-V) recordings were performed using a two-electrode voltage clamp device (OC725A; Warner, Hambden, CT, USA) in the voltage clamp mode. Substrate-associated currents were obtained by subtraction of the currents in the presence from those in the absence of the substrate of interest.

Statistics and calculations

Data are provided as means ± SEM. Paired Student’s t test was used to show statistically significant difference of citrate uptake in the absence and presence of the GA derivatives or of succinate uptake in the absence and presence of glutamate. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.01. Michaelis-Menten constants (KM) for 3OHGA, D- and L-2OHGA were determined by SigmaPlot software (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA, USA) using the Michaelis-Menten equation I = Imax · [S]/(KM + [S]), where I is the current, Imax is the maximum current observed at saturating substrate concentrations, KM is the substrate concentration at half-maximal current, and S is the substrate concentration.

Results

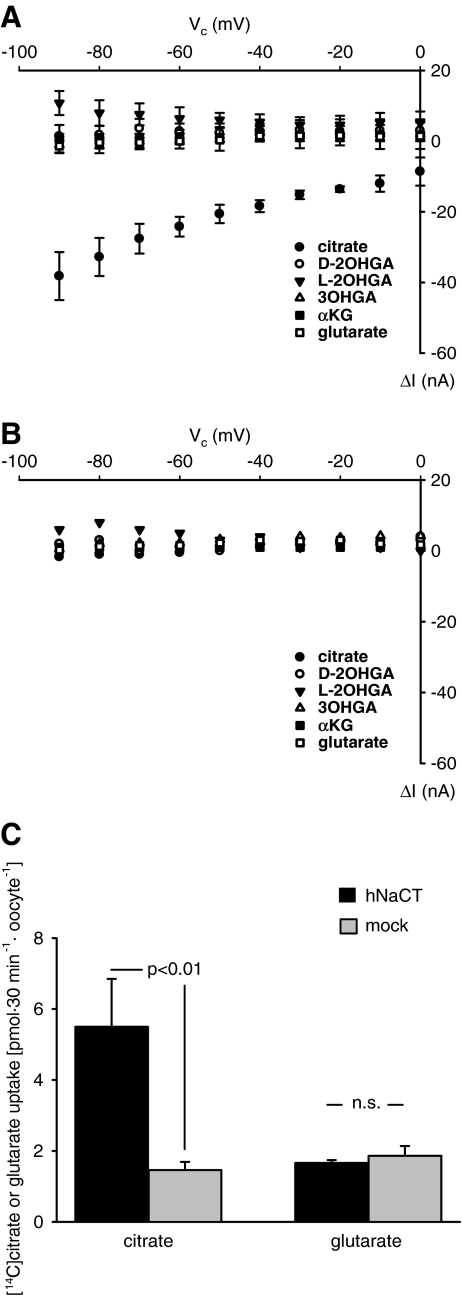

In hNaCT-expressing oocytes (5 oocytes from 4 donors), application of 1 mM citrate led to potential-dependent inward currents showing larger current amplitudes at –90 mV than at more depolarizing potentials (Fig. 1a, closed circles). The inward currents were abolished upon substitution of all sodium by N-methyl-D-glucamine (data not shown). In contrast to citrate, the GA derivatives 3OHGA, D-2OHGA, L-2OHGA, and GA itself, did not evoke any potential-dependent inward currents. The individual currents induced by these compounds were similar in hNaCT-expressing oocytes (Fig. 1a) and in mocks (Fig. 1b). Increasing the concentration of GA up to 5 mM did not change this result (data not shown), indicating that GA and GA derivatives are either not transported by hNaCT or transport is electroneutral. To discriminate between these possibilities, the uptake of [14C]citrate was compared to the uptake of [14C]glutarate within 30 min in the same batch of hNaCT-expressing oocytes (Fig. 1c). Whereas citrate uptake increased by a factor of 3.76 ± 0.63 (three independent experiments) as compared to mocks, the uptake of GA in hNaCT-expressing oocytes and in mocks was virtually identical.

Fig. 1.

Effects of GA derivatives on hNaCT-expressing oocytes. Current-voltage (I-V) relations of substrate-associated currents in hNaCT-expressing oocytes are shown in (a), (c) and mocks (b). Oocytes were superfused first with ORi and subsequently with ORi to which 1 mM of the respective GA derivative was added. Subtraction of the currents obtained in the presence from those in the absence of the respective substrate revealed the substrate-associated currents, ΔI. Oocytes were first tested for the current induced by the prototypical substrate, citrate, to test for successful expression and only oocytes showing citrate-associated currents >20 nA at −90 mV were used in this study. Afterwards, 3OHGA, D-, L-2OHGA, αKG, and GA were applied at random order. a, b Means ± SEM of 5 oocytes from 4 donors and of 3 oocytes from 3 donors, respectively. c Comparison of the uptake of labeled citrate and glutarate in the same batch of oocytes. Whereas the hNaCT-expressing oocytes (3 independent experiments with 10 oocytes for each experimental condition) took up citrate (12 μM), no uptake of glutarate (20 μM) was observed.

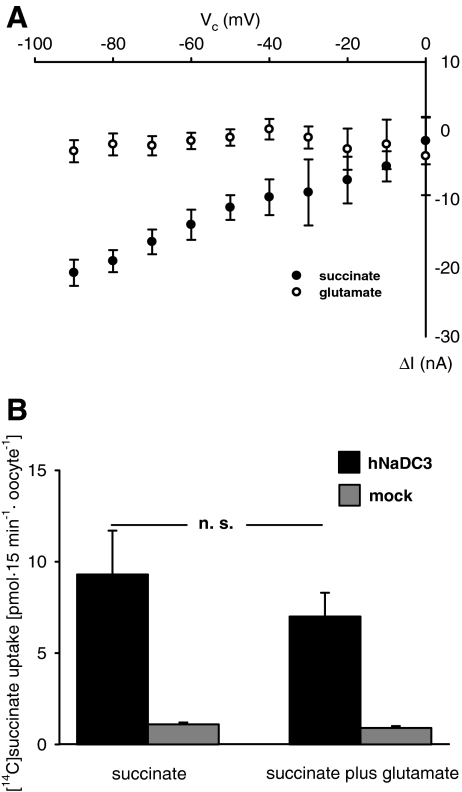

In hNaDC3-expressing oocytes (4 oocytes from four donors), succinate (1 mM) evoked substrate-dependent inward currents at all potentials tested (Fig. 2a, closed circles). Subsequent application of glutamate (1 mM) did not give rise to such currents (Fig. 2a, open circles). Neither succinate- nor glutamate-associated currents were observed in mocks (data not shown). In addition, succinate uptake was only marginally inhibited by 1 mM glutamate during an incubation time of 15 min (Fig. 2b, two independent experiments with 8–10 oocytes per experimental condition).

Fig. 2.

Effect of succinate and glutamate on hNaDC3. a Current-voltage (I-V) relations as a function of membrane potential (Vc) in hNaDC3-expressing oocytes were obtained by substraction of the currents in the presence of 1 mM succinate in ORI (●) or of 1 mM glutamate (○) in ORI from those measured in ORI alone. Data present mean values ± SEM of 4 oocytes from 4 donors. b Succinate uptake in the absence and presence of 1 mM glutamate in hNaDC3-expressing oocytes (black columns) and mocks (grey columns) as obtained in two independent experiments with 8–10 oocytes for each experimental condition. Uptake of succinate in the absence and presence of glutamate was not significantly different.

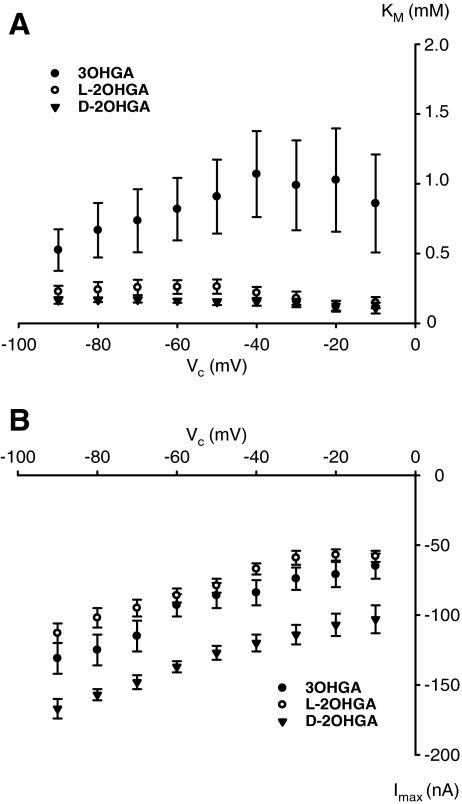

At −60 mV, hNaDC3 mediates translocation of 3OHGA, D-, and L-2OHGA with low affinity (Hagos et al. 2008). These kinetic measurements were now extended to a broader potential range (−90 to 0 mV), because, in the disease, astrocytes might have lower membrane potentials and the transporter may change its affinity to the GA derivatives. At all potentials tested, the KM for 3OHGA was larger than the KM for D- and L-2OHGA. Whereas the KM values for D- and L-2OHGA were similar and decreased with depolarizing membrane potential, the KM for 3OHGA increased at depolarization (Fig. 3a). The maximal currents observed for each compound increased with hyperpolarization (Fig. 3b). The largest current amplitudes were observed for D-2OHGA (3 oocytes from 3 donors); the amplitudes measured for 3OHGA (7 oocytes from 3 donors) and L-2OHGA (6 oocytes from 5 donors) were similar in magnitude at all potentials tested (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Michaelis-Menten constants (KM (mM)) (a) and maximal substrate-inducible currents (Imax (nA)) (b) of the GA derivatives as a function of membrane potential (Vc). hNaDC3-expressing oocytes were subsequently superfused with increasing substrate concentrations of 3OHGA: 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mM; D- and L-2OHGA: 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mM in ORi at pH 7.5. Values were calculated using the SigmaPlot Systat program. Data were obtained at the end of a 10-s perfusion with the respective solution at the indicated Vc and were calculated from 7 oocytes of 3 donors for 3OHGA, for D-2OHGA from 3 oocytes from 3 donors, and for L-2OHGA from 5 oocytes from 4 donors.

Discussion

To date, the brain is the only mammalian tissue from which NaCT has been cloned (Inoue et al. 2002a, b). Subsequent studies have shown that its expression is restricted to neurons (Wada et al. 2006; Yodoya et al. 2006). Therefore, we reasoned that hNaCT might be able to accept GA derivatives which were suggested to induce the neuronal damage observed in patients suffering from glutaric aciduria type 1 and D, L-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. However, these compounds neither induced substrate-associated currents nor did they inhibit the uptake of citrate, the prototypical substrate of hNaCT, in hNaCT-expressing oocytes. In addition, we found no interaction of hNaCT with αKG, a compound recently described to be taken up by neurons (Shank and Bennett 1993). Consequently, uptake of the GA derivatives into neurons by NaCT is not the cause of the observed neurodegeneration.

Particularly for glutaric aciduria type 1, it is suggested that glutaryl-CoA, GA, and 3OHGA accumulating in the synaptic cleft is involved in the pathogenesis of the disease (Kölker et al. 2004; Strauss et al. 2010). Because these compounds do not readily cross the blood-brain barrier, they accumulate within the brain (Kölker et al. 2002a, b; Junqueira et al. 2003, 2004; Porciuncula et al. 2004; Wajner et al. 2004; Gerstner et al. 2005; Sauer et al. 2006), where they may inhibit the delivery of neurometabolic precursors.

Due to the absence of pyruvate carboxylase (Cesar and Hamprecht 1995; Hassel 2001), neurons lack the capacity to perform de novo synthesis of tricarboxylic cycle constitutents (TCA) and therefore depend on extracellular sources of TCA intermediates to replenish intracellular pools of neurotransmitters, such as glutamate and γ-aminoisobutyrate (GABA). Astrocytes, which in contrast to neurons, express pyruvate carboxylase (Shank et al. 1985), play a major role in feeding TCA constituents to the neurons. Since NaCT is localized in neurons, we assumed that NaCT is responsible not only for the uptake of citrate but also for the uptake of other tri- and dicarboxylic acid derivatives into neurons. This, however, was not the case: GA and αKG were not accepted by NaCT.

The synaptic action of glutamate is terminated by its uptake into astrocytes and or into presynaptic neurons. Uptake of glutamate into astrocytes occurs by distinct excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) and possibly by low affinity sodium-dependent transport systems (Danboldt 2001; Holten et al. 2008). One such candidate transporter may be NaDC3, recently localized to astrocytes (Yodoya et al. 2006). However, glutamate neither induced inward currents nor inhibited succinate uptake in hNaDC3-expressing oocytes, and 1 mM glutamate reduced succinate uptake only by 19.9 ± 8.5 % (N.S.). Therefore, hNaDC3 can be excluded as a transporter facilitating glutamate uptake into astrocytes as opposed to recent speculation (Frizzo et al. 2004; Holten et al. 2008).

At –60 mV, hNaDC3 carries αKG and GA with high and the other GA derivatives with moderate affinity (Hagos et al. 2008). In the present study, we found that the affinities for D- and L-2OHGA increased whereas that of 3OHGA decreased at depolarized potentials. Besides KM, Imax was also influenced by the membrane potential. The different GA derivatives also differ in their Imax being largest for D-2OHGA, indicating that D-2OHGA can be taken up into astrocytes at high rates and may interfere with the uptake of αKG which is needed by astrocytes for the synthesis of glutamine (Peng et al. 1991) and other metabolic purposes.

Although our findings did not elucidate the mechanisms by which the GA derivatives induce the neuronal damage observed in the affected patients, we can definitely exclude NaCT as a transporter facilitating the uptake of D- and L-2OHGA as well as 3OHGA into neurons. The impaired uptake of αKG due to the efficient interactions of D- and L-2OHGA with NaDC3 could interfere with the astrocytes ability to produce TCA derivatives and to feed neurons with these compounds needed for synthesis of neurotransmitters. As, during brain development, energy requirements are increasing (Harting et al. 2009), the metabolic support of astrocytes may be limited due to accumulating GA derivatives in the synaptic cleft. This in turn may induce the observed neuronal damage due to shortage of fuels when the brain is in a most vulnerable phase as recently discussed by Strauss et al. (2010).

Acknowledgments

The hNaCT clone was a generous gift of V. Ganapathy, PhD, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, USA. We also thank C. Mühlhausen, MD, Dept. Pediatrics, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany for the generous gift of 3OHGA. The authors are grateful for financial support by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (P22/07 // A19/07). The technical assistance of I. Markmann is gratefully acknowledged.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Competing interest:

None declared.

References

- Alebouyeh M, Takeda M, Onozato ML, Tojo A, Noshiro R, Hasannejad H, Inatomi J, Narikawa S, Huang X-L, Khamdang S, Anzai N, Endou H. Expression of human organic anion transporters in the choroid plexus and their interactions with neurotransmitter metabolites. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003;93:430–436. doi: 10.1254/jphs.93.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleasby K, Castle JC, Roberts CJ, Cheng C, Bailey WJ, Sina JF, Kulkarni AV, Hafey MJ, Evers R, Johnson JM, Ulrich RG, Slatter JG. Expression profiles of 50 xenobiotic transporter genes in humans and pre-clinical species: a resource for investigations into drug disposition. Xenobiotica. 2006;36:963–988. doi: 10.1080/00498250600861751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesar M, Hamprecht B. Immunocytochemical examination of neural rat and mouse primary cultures using monoclonal antibodies raised against pyruvate carboxylase. J Neurochem. 1995;64:2312–2318. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danboldt NC. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frizzo MES, Schwarzbold C, Prociuncula LO, et al. 3-Hydroxyglutaric acid enhances glutamate uptake into astrocytes from cerebral cortex of young rats. Neurochem Inter. 2004;44:345–353. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0186(03)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CBR, Prasad AN, Frosk P, et al. Neuropathological, biochemical and molecular findings in a glutaric academia type 1 cohort. Brain. 2005;128:711–722. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner B, Gratopp A, Marcinkowski M, Sifringer M, Obladen M, Bührer C. Glutaric acid and its metabolites cause apoptosis in immature oligodendrocytes: a novel mechanism of white matter degeneration in glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:771–776. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000157727.21503.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagos Y, Krick W, Braulke T, Mühlhausen C, Burckhardt G, Burckhardt BC. Organic anion transporters OAT1 and OAT4 mediate the high affinity transport of glutarate derivatives accumulating in patients with glutaric acidurias. . Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2008;457:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting I, Neumaier-Probst, Seitz A, et al. Dynamic changes of striatal and extrastriatal abnormalities in glutaric aciduria type I. Brain. 2009;132:1764–1782. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassel B. Pyruvate carboxylation in neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:755–762. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund GL, Longo N, Pasquali M. Glutaric academia Type 1. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C:86–94. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holten AT, Danboldt NC, Shimamoto S, Vidar G. Low-affinity excitatory amino acid uptake in hippocampal astrocytes: a possible role of Na+/dicarboxylate cotransporters. Glia. 2008;65:990–997. doi: 10.1002/glia.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Zhuang L, Ganapathy V. Human Na+-coupled citrate transporter: primary structure, genomic organization, and transport function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299:465–471. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Zhuang L, Maddox DM, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Structure, function, and expression pattern of a novel sodium-coupled citrate transporter (NaCT) cloned from mammalian brain. J Bio Chem. 2002;277:39469–39476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira D, Brusque AM, Prociuncula LO, et al. Effects of L-2-hydroxyglutaric acid on various parameters of the glutamatergic system in cerebral cortex of rats. Metab Brain Dis. 2003;18:233–243. doi: 10.1023/A:1025559200816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira D, Brusque AM, Prociuncula LO, et al. In vitro effects of D-2-hydroxyglutaric acid on glutamate binding, uptake and release in cerebral cortex of rats. J Neurol Sci. 2004;15:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölker S, Okun JG, Ahlemeyer B, et al. Ca2+ and Na+ dependence of 3-hydroxyglutarate-induced excitotoxicity in primary neuronal cultures from chick embryo telencephalons. Pediatr Res. 2002;52:199–206. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000023176.89966.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölker S, Pawlak V, Ahlemeyer B, et al. NMDA receptor activation and respiratory chain complex V inhibition contribute to neurodegeneration in D-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:21–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölker S, Koeller DM, Okun JG, Hoffmann GF. Pathomechanisms of neurodegeneration in glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:7–12. doi: 10.1002/ana.10784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlhausen C, Burckhardt BC, Hagos Y, et al. Membrane translocation of glutaric aciduria and its derivatives. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:188–193. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0825-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajor AM, Gangula R, Yao X. Cloning and functional characterization of a high-affinity Na+/dicarboxylate cotransporter from mouse brain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1215–C1223. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng LA, Schousboe A, Hertz L. Utilization of alpha-ketoglutarate as a precursors for transmitter glutamate in cultured cerebellar granule cells. Neurochem Res. 1991;16:29–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00965824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porciuncula LO, Emanuell T, Tavares RG, et al. Glutaric acid stimulates glutamate binding and astrocytic uptake and inhibits vesicular glutamate uptake in forebrain from young rats. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read MH, Bonamy C, Laloum D, et al. Clinical, biochemical, magnetic resonance and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) findings in a fourth case of combined D- and L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28:1149–1150. doi: 10.1007/s10545-005-4565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzem R, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Noel G, et al. A gene encoding a putative FAD-dependent L-2-2hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase is mutate in L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16849–16854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404840101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer SW, Okun JG, Fricker G, et al. Intracerebral accumulation of glutaric and 3-hydroxyglutaric acids secondary to limited flux across the blood-brain barrier constitute a biochemical risk factor for neurodegeneration in glutary-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Neurochem. 2006;97:899–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiijo-Martinez M, Navarro C, Castro del Rio M, et al. L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:666–670. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.4.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shank RP, Bennet GS, Freytag SO, Campell GLM. Pyruvate carboxylase: an astrocyte-specific enzyme implicated in the replenishment of amino acid neurotransmitter pools. Brain Res. 1985;329:364–367. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shank RP, Bennet DJ. 2-Oxoglutarate transport: a potential mechanism for regulating glutamate and tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates in neurons. Neurochem Res. 1993;18:401–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00967243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss KA, Donnelly P, Wintermark M. Cerebral haemodynamics in patients with glutaryl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. Brain. 2010;133:76–92. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struys EA, Salomons GS, Achouri Y, et al. Mutations in the D-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase gene cause D-2-hydroxglutaric aciduria. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:358–360. doi: 10.1086/427890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struys EA. D-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria: Unravelling the biochemical pathway and the genetic defect. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struys EA, Gibson KM, Jakobs C. Novel insights into L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria: mass isotopomer studies reveal 2-oxoglutaric acid as the metabolic precursor of L-2-hydroxyglutaric acid. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:690–693. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0697-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada M, Shimada A, Fujita T. Functional characterization of Na+-coupled citrate transporter NaC/NaCT expressed in primary cultures of neurons from mouse cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 2006;1081:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajner M, Kölker S, Souza DO, Hoffmann GF, De Mello CF. Modulation of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission in glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2004;27:825–828. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000045765.37043.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yodoya E, Wada M, Shimada A, et al. Functional and molecular identification of sodium-coupled dicarboxylate transporters in rat primary cultured cerebrocortical astrocytes and neurons. J Neurochem. 2006;97:162–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]