Abstract

The M78 protein of murine cytomegalovirus exhibits sequence features of a G protein-coupled receptor. It is synthesized with early kinetics, it becomes partially colocalized with Golgi markers, and it is incorporated into viral particles. We have constructed a viral substitution mutant, SMsubM78, which lacks most of the M78 ORF. The mutant produces a reduced yield in cultured 10.1 fibroblast and IC21 macrophage cell lines. The defect is multiplicity dependent and greater in the macrophage cell line. Consistent with its growth defect in cultured cells, the mutant exhibits reduced pathogenicity in mice, generating less infectious progeny than wild-type virus in all organs assayed. SMsubM78 fails to efficiently activate accumulation of the viral m123 immediate-early mRNA in infected macrophages. M78 facilitates the accumulation of the immediate-early mRNA in cycloheximide-treated cells, arguing that it acts in the absence of de novo protein synthesis. We conclude that the M78 G protein-coupled receptor homologue is delivered to cells as a constituent of the virion, and it acts to facilitate the accumulation of immediate-early mRNA.

The G protein-coupled receptors (GCRs) play a key role in the transduction of extracellular signals to the intracellular environment. Upon ligand binding, GCRs activate G proteins, which in turn activate effector proteins in a cascade-like fashion. Genes encoding GCR homologues have been identified in several families of viruses, including herpesviruses. The β-herpesviruses encode multiple proteins with characteristics of GCRs. Receptor-like proteins belonging to the so-called UL78 gene family are found in five β-herpesviruses: human cytomegalovirus UL78 (1), murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) M78 (2), rat cytomegalovirus R78 (3), human herpesvirus-6 U51 (4), and human herpesvirus-7 U51 (5). The positions of the genes encoding these family members on the different viral genomes are conserved, although their overall sequence homology is modest. For example, the human cytomegalovirus and MCMV proteins are only 19% identical in their amino acid sequences.

The MCMV M78 protein contains seven predicted hydrophobic transmembrane domains and conserved cysteine residues in its first and second extracellular loops that are characteristic of all GCRs. The putative amino-terminal extracellular domain is relatively short and does not contain any potential N-linked glycosylation sites. This is a characteristic of small ligand-binding receptors, and it is in contrast to GCRs that bind peptide hormones, which usually have a larger amino-terminal extracellular domain with several N-linked glycosylation sites. The predicted M78 transmembrane domains contain conserved amino acids characteristic of GCRs: proline residues in domains IV, V, VI, and VII; glycine and valine in domain I; leucine and two alanines in domain II; isoleucine in domain III; tryptophan and the WxxxxxxxxP motif in domain IV; phenylalanine in domain VI; and tyrosine in domain VII (6). The most highly conserved intracellular sequence in all GCRs is at the carboxyl-terminal region of domain III: the aspartate-arginine-tyrosine (DRT) triplet, which has been implicated in signal transduction (7, 8). Whereas the arginine of this triplet is invariant, the aspartate and tyrosine can be conservatively substituted. In M78, the tyrosine has been replaced by a leucine. Another characteristic of GCRs that is found in M78 is a cysteine residue in the C-terminal portion of the receptor tail that can be palmitoylated and consequently membrane-associated to form an additional cytosolic loop. Most GCRs have several potential phosphorylation sites in their third cytoplasmic loop and/or carboxyl terminus, which are used to activate or desensitize the receptor (9). M78 contains the consensus sequence (RRVSP) for cAMP-dependent protein kinase (10), as well as target sites for protein kinase C and tyrosine kinase in its presumptive intracellular segments. These characteristics argue strongly that M78 is a GCR and that it likely binds to a small ligand.

Here, we show that M78 is synthesized with early kinetics, it becomes partially colocalized with Golgi markers, and it is incorporated into MCMV particles. We have constructed an MCMV substitution mutant, SMsubM78, lacking most of the M78 ORF. The mutant virus grows poorly in cultured cells and fails to efficiently activate expression of the m123 immediate-early gene, arguing that the receptor homologue delivered to cells as a constituent of the virion acts to induce mRNA accumulation.

Materials and Methods

Virus and Cells.

The Smith strain (11) of MCMV was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and the K181+ strain was obtained from E. Mocarski (Stanford); plaque-purified derivatives were used in these studies. Virus stocks were produced and titered on the 10.1 mouse embryo fibroblast cell line (12), which was propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS. Viral growth also was examined in the IC21 mouse macrophage cell line (ATCC), which was propagated in RPMI-1640 medium (ATCC 30–2001) supplemented with 10% FBS.

To produce a mutant virus lacking the M78 gene, a plasmid was designed that would create a substitution mutation upon recombination with the viral genome in mouse cells. The M78 coding region with about 1.0 kb of flanking region on each side (110,065–113,459-bp genomic region, sequence numbers from ref. 2) was amplified by PCR and cloned into pUC19. Then, the AvrII–XhoI fragment of the M78 coding region was replaced with the enhanced green fluorescent protein EGFP cassette (XhoI–SgfI fragment) from pGET007 (13), so that the EGFP coding region controlled by the SV40 promoter and polyA site was inserted in the opposite direction to that of the M78 coding region (Fig. 1). This construct was mixed with purified wild-type Smith viral DNA (1:2) and used to transfect 10.1 cells with Lipofectamine (Boehringer Mannheim). Three rounds of plaque purification generated a pure population of virus, termed SMsubM78, carrying the substitution mutation. A revertant virus, named SMrev78, was produced by cotransfecting 10.1 cells with SMsubM78 DNA and a plasmid containing the 107,763–113,959-bp genomic region. In this plasmid, the RsrII site at 112,501 bp was disrupted with a 3-bp insertion (GTC), making it possible to distinguish the revertant from contaminating wild-type virus. SMrev78 was purified by limiting dilution.

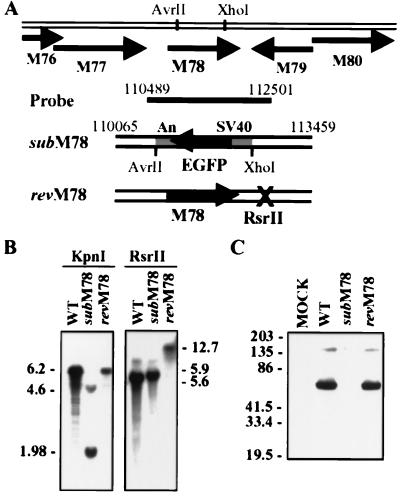

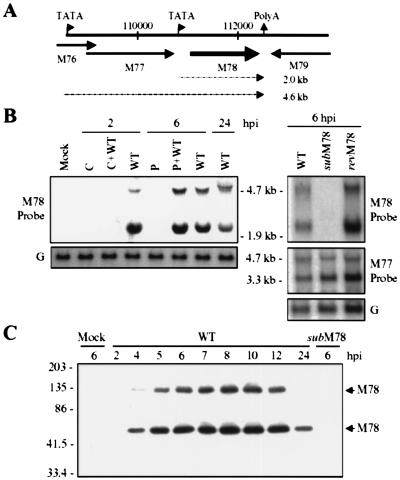

Figure 1.

Construction and physical characterization of SMsubM78 and SMrevM78. (A) Schematic representation of the MCMV M78 genomic region with open reading frames designated by arrows, plasmids used to generate the mutant (subM78) and revertant (revM78), and the probe used for Southern blot analysis. Key nucleotide sequence numbers and restriction endonuclease cleavage sites are indicated, as are the open reading frames surrounding M78. The EGFP substitution in SMsubM78 is controlled by the SV40 early promoter and polyA site (An). (B) Southern blot analysis. Viral DNA was isolated from infected 10.1 cells and digested with KpnI or RsrII. The sizes of the DNA fragments are indicated in kilobases. (C) Western blot analysis. Cell lysates were prepared at 6 h postinfection from 10.1 cells and subjected to Western blot analysis by using antibody to M78 (C-M78/2).

Analysis of Viral Nucleic Acids and Protein.

In all experiments, 10.1 or IC21 cells were infected at a multiplicity of 3 pfu/cell. Total RNA (5 μg) was subjected to Northern blot assay by using as probe double-stranded DNA that was 32P-labeled by random priming. Viral DNA was prepared by lysing infected cells in extraction buffer (0.14 M NaCl/1.5 mM MgCl2/10 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.6/0.5% Nonidet P-40/1 mM DTT), pelleting the cellular debris, and digesting the supernatant with proteinase K (50 μg/ml). After extraction with phenol-chloroform and precipitation with ethanol plus sodium acetate, ≈1-μg aliquots of DNA were subjected to Southern blot analysis by using the 32P-labeled probe described above.

A glutathione S-transferase fusion protein (C-M78/GST) containing the C-terminal domain of M78 (amino acids 378 to 472) was used as immunogen to produce rabbit polyclonal (C-M78/2) and mouse monoclonal (3G6) antibodies. For immunofluorescence, infected cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS, treated with blocking solution (0.5% BSA and 10% goat serum in PBS), sequentially incubated with the primary antibody to M78 (C-M78/2) and Alexa 568-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody in blocking solution, and subjected to confocal microscopy. In colocalization studies, the M78-specific monoclonal antibody (3G6) was used together with a medial Golgi Mannosidase II-specific rabbit antibody (14) plus an Alexa 568-labeled goat anti-mouse and an Alexa 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody, respectively. Nuclei were stained with TOTO-3 (Molecular Probes). For Western blot analysis, cells were harvested in lysis buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40/150 mM NaCl/10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.2/2 mM EDTA/50 mM sodium fluoride. Because M78 appears to form aggregates when boiled, the samples were incubated for 5 min at 42°C before electrophoresis. C-M78/2 antibody was used to visualize M78 by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Virions were partially purified by centrifugation through a 15% sucrose cushion. In some cases, partially purified virions were treated with proteinase K (10 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C in the presence or absence of 1% Nonidet P-40, and the reaction was stopped by adding 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Samples were subjected to Western blot analysis by using the C-M78/2 antibody.

Pathogenesis in Mice.

Virus was concentrated by centrifugation through a 15% sucrose cushion and titered by plaque assay on 10.1 cells. Six-week-old female BALB/c, C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory), or γc/Rag2 double-knockout (Taconic) mice were injected intraperitoneally with virus. To compare the pathogenicity of different viruses, mice were infected and monitored for survival. To assay viral spread, mice were killed by CO2 inhalation, and organs were homogenized by trituration as a 10% solution in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS. The total amount of infectious virus per organ was determined by plaque assay of the homogenates. Experimental protocols were approved by the Princeton University Animal Welfare Committee and were consistent with regulations stipulated by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and those in the Animal Welfare Act.

Results

M78 Is Required for Efficient Replication in Cultured Cells and in Vivo.

To probe the role of the M78 gene, a mutant virus lacking most of the M78 coding sequence was constructed. SMsubM78 contains a substitution mutation in which the MCMV 111,124–112,106-bp domain (sequence numbers from ref. 2) was replaced by an EGFP gene controlled by the SV40 promoter and polyA site (Fig. 1A). The deletion of the M78 ORF and insertion of the EGFP cassette was confirmed by Southern blot (Fig. 1B), mutant virus stocks were shown to be free of detectable wild-type virus contamination by PCR assay (data not shown), and Western blot analysis confirmed that the M78 protein is not present in mutant virus-infected cells (Fig. 1C). To verify that potential mutant phenotypes are because of the targeted substitution mutation within the M78 ORF and not to another mutation, a revertant virus, SMrev78, was prepared. Its RsrII recognition site at position 112,501 was altered, allowing it to be distinguished from a wild-type virus contaminant (Fig. 1 A and B). M78 gene expression was restored in SMrev78 (Fig. 1C).

To test for a role of M78 in MCMV replication within cultured cells, the growth of SMsubM78 and SMrev78 was compared with that of wild-type virus at high (3 pfu/cell) and low (0.01 pfu/cell) multiplicities of infection in 10.1 fibroblast and IC21 macrophage cells (Fig. 2A). Macrophages play an important role in the spread, immune surveillance, and latency of MCMV infection (15). Although there was little difference in the growth kinetics of the viruses at the higher multiplicity, SMsubM78 replicated somewhat more slowly at the lower input multiplicity, and this defect was most pronounced in the IC21 macrophage cells. In these cells, the yield of mutant virus was reduced by a factor of ≥50 in comparison with the wild-type parent or revertant on days 4–6 after infection. M78 is not absolutely required, but it makes replication of MCMV in cultured cells more efficient.

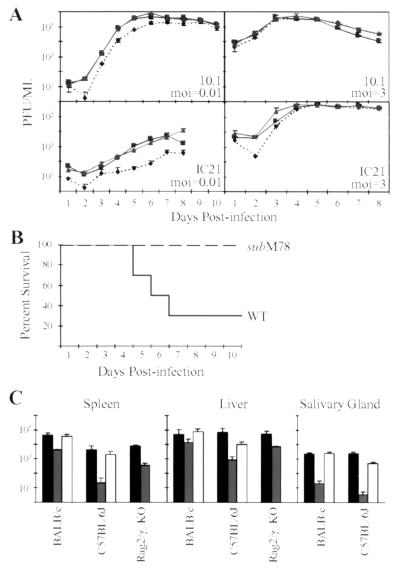

Figure 2.

Growth properties of SMsubM78 and SMrevM78. (A) 10.1 or IC21 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 0.01 or 3 pfu/cell with wild-type virus (■), SMsubM78 (⧫), or SMrevM78 (▴). Supernatants were harvested at the indicated times, and virus was quantified by plaque assay on 10.1 cells. Three independently infected cultures were assayed for each time point. (B) Survival curves. Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with wild-type virus (WT) or SMsubM78 (3 × 106 pfu) and monitored for survival. (C) Accumulation of infectious virus in spleen, liver, and salivary gland. Six-week-old mice were injected intraperitoneally with 3 × 106 pfu (BALB/c and C57BL/6J) or 3 × 105 pfu (Rag2/γc KO in a C57BL/6J background). Animals were killed, and total virus in homogenates of spleen and liver (3 days after infection) or in salivary glands (14 days after infection) was determined by plaque assay on 10.1 cells. Wild-type virus is represented by black bars, SMsubM78 by gray bars, and SMrevM78 by white bars; each data point represents the average plus standard deviation for at least three animals.

To determine whether M78 is required for viral growth in its natural host, 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally with mutant or wild-type virus (3 × 106 pfu/animal), and survival was monitored (Fig. 2B). After 11 days, all SMsubM78-infected mice survived, whereas 70% of wild-type virus-infected mice had died. To monitor growth and spread of the virus, 6-week-old female mice were infected (3 × 106 pfu/animal), organs were harvested 3 days later, and virus was quantified by plaque assay (Fig. 2C). A reduction in SMsubM78 yield in comparison to wild-type virus was observed for the spleen and liver in BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice. Persistently infected salivary glands were harvested on day 14 after infection, and the mutant exhibited a ≥100-fold reduced yield relative to the wild-type virus. Rag2/γc knockout mice (16, 17), lacking B cells, T cells, natural killer, and natural killer T cells, also were infected with mutant and wild-type virus (3 × 105 pfu/animal). Accumulation of virus in the liver and spleen of knockout mice was similar to what was observed in the parental C57BL/6J animals (Fig. 2C), arguing that the reduced replication and pathogenicity observed for SMsubM78 is not because of increased sensitivity to one or more components of the immune system missing in these mice.

In sum, SMsubM78 exhibits a growth defect in cultured cells that are infected at relatively low input multiplicities, and it fails to replicate efficiently in normal and immunodeficient mice. These results argue that M78 is required for efficient replication at the level of the individual infected cell and during the acute and persistent phases of infection within mice.

M78 Protein Is Present in Purified Virions.

For the closely related human cytomegalovirus, Golgi markers have been shown to colocalize with a variety of viral structural proteins (18), and they might mark an assembly site where a capsid-containing structure acquires some of the tegument proteins plus an envelope with associated membrane proteins. The localization of the M78 protein in MCMV-infected 10.1 or IC21 cells was examined by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 3A). The protein accumulated in cytoplasmic structures with the appearance of vacuoles in both 10.1 and IC21 cells, colocalized with a medial Golgi marker, Mannosidase II (Fig. 3A), and a peripheral Golgi protein (data not shown). The association of M78 with Golgi markers raised the possibility that the GCR homologue is packaged into MCMV particles. Accordingly, partially purified virions were subjected to Western blot assay (Fig. 3B). M78 protein was detected in two wild-type strains of MCMV but not in purified SMsubM78 particles. To show that the protein was present in the virion envelope, purified virions were treated with proteinase K in the presence or absence of 1% Nonidet P-40 (Fig. 3C). When virions were not disrupted with Nonidet P-40, an ≈33-kDa C-terminal fragment of M78 survived the treatment; when virions were solubilized in Nonidet P-40, the M78 protein was completely degraded. Because the antibody recognizes the C terminus of M78, we can conclude that the GCR homologue is localized in the virion envelope with its C terminus facing the tegument.

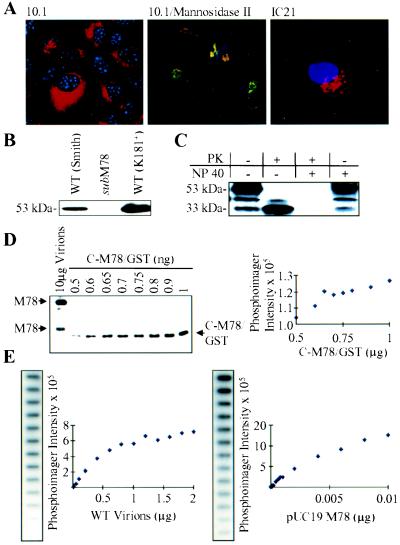

Figure 3.

M78 is a constituent of the MCMV envelope. (A) M78 colocalizes with the Golgi apparatus. 10.1 (Left and Center) or IC21 cells (Right) were infected at a multiplicity of 3 pfu/cell with wild-type virus, harvested 6 h later, and processed for immunofluorescence by using antibody to M78 (Left and Right; red signal) or to M78 plus the Mannosidase II Golgi marker (Center, M78 signal is green, Mannosidase II signal is red, and M78/Mannosidase II coincident signal is yellow). Nuclei are stained blue with TOTO-3. (B) Detection of M78 in virions by Western blot assay. Virions from two wild-type (WT) strains of MCMV (Smith and K181+) were partially purified and assayed by using an M78-specific antibody (C-M78/2). The apparent molecular weight of M78 is indicated. (C) Accessibility of virion-associated M78 to proteinase. Partially purified virions with intact or solubilized (Nonidet P-40) envelopes were digested with proteinase K (PK), and M78 was assayed by Western blot by using M78-specific antibody. The apparent molecular weights of M78 and a C-terminal digestion product are indicated. (D) Number of M78 molecules per quantity of virions. The M78 signal for wild-type virions (10 μg) was compared with known amounts of a purified M78 fusion protein (C-M78/GST) by Western blot by using M78-specific antibody. (E) Number of viral genomes per quantity of virions. The copy number of DNA containing the M78 coding region in different amounts of virions was compared with known amounts of a plasmid (pUC19/M78) containing the M78 ORF by Southern blot by using an M78-specific probe DNA. Slot blot autoradiograms are shown to the left of graphs displaying the quantitative data produced by phosphorimager analysis.

We next determined the approximate number of M78 molecules per viral genome in partially purified virion preparations. We compared the amount of the two M78-specific protein bands in a virion sample with known amounts of the C-M78/GST fusion protein (37.8 kDa) by Western blot analysis by using an M78-specific polyclonal antibody (Fig. 3D). We found that 10 μg of virions contains the same number of M78 molecules as the number of molecules in 2 ng of C-M78/GST protein (i.e., ≈3.2 × 1010 molecules). By comparing the amount of M78 DNA in virions and in a plasmid containing the M78 ORF in a Southern blot by using an M78-specific probe DNA (Fig. 3E), we ascertained that there are ≈7.9 × 109 viral genomes in 10 μg of virions. Therefore, there are ≈4 M78 molecules per viral genome, and, because the pfu/viral genome ratio is ≈500 (19), there are ≈2,000 M78 molecules per infectious unit in purified preparations of MCMV particles.

M78 Facilitates Accumulation of Immediate-Early mRNA.

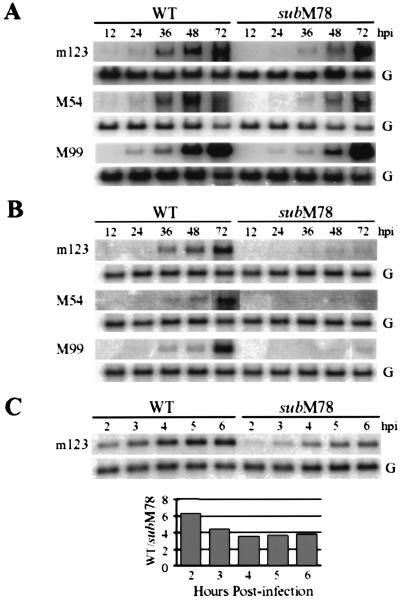

Because M78 in the virion envelope would presumably be delivered to newly infected cells and have the opportunity to influence events at the start of the infectious process, we asked whether M78 influences the accumulation of viral mRNAs. Northern blot analysis revealed that the accumulation of the m123 immediate-early, the M54 early, and the M99 late mRNAs were somewhat delayed in SMsubM78 as compared with wild-type virus-infected 10.1 cells (Fig. 4A). The reduction was much more severe in IC21 macrophages, where little viral mRNA was detected after infection with SMsubM78 (Fig. 4B). The mutant also accumulated 4–6-fold less m123 immediate-early mRNA when IC21 macrophages were infected in the presence of cycloheximide (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that M78 can enhance mRNA accumulation in the absence of protein synthesis.

Figure 4.

M78 facilitates viral mRNA accumulation. (A) 10.1 cells were infected at a multiplicity of 0.01 pfu/cell with wild-type virus (WT) or SMsubM78, harvested at the indicated hours postinfection (hpi), and assayed for accumulation of an immediate-early (m123), early (M54), and late (M99) mRNA by Northern blot. Cellular glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA (G) was assayed as a control. (B) IC21 cells were infected and processed as described in A. (C) IC21 cells were infected in the presence of cycloheximide (30 μg/ml) and processed as described in A. The graph below presents the ratio of the amount of wild-type (WT) relative to SMsubM78 m123 mRNA, determined by quantification of band intensities in the autoradiograph by using a phosphorimager.

Although the cycloheximide experiment indicated that virion-associated M78 protein contributed to m123 mRNA accumulation, it seemed possible that newly synthesized M78 protein might also contribute to this accumulation. Therefore, we examined the time at which M78 mRNA and protein are expressed from the viral genome to ascertain when newly synthesized protein would be available to contribute to the enhanced accumulation of immediate-early mRNAs. The kinetic class of M78-specific mRNAs was determined by Northern blot analysis of RNA from 10.1 cells infected in the presence of cycloheximide (immediate-early genes are expressed), phosphonoacetic acid (immediate-early and early genes are expressed), or no drug (all kinetic classes are expressed). An M78-specific probe identified two RNAs migrating at about 1.9 and 4.7 kb (Fig. 5B, Left). There is a TATA box upstream of the M78 ORF and another upstream of M77, but there is only one consensus poly(A) site downstream of the two open reading frames (Fig. 5A). This arrangement of motifs suggested that the larger transcript includes M77 and M78 sequences, whereas the smaller transcript contains only M78 sequences. This expectation was confirmed by probing the wild-type RNA with an M77-specific probe (Fig. 5B, Right). This probe did not detect the 1.9-kb RNA species; rather, it identified an M77-specific 3.3-kb RNA. The 1.9- and 4.7-kb transcripts are not synthesized in cycloheximide-treated cells but accumulated in the presence of phosphonoacetic acid, indicating that M78 is an early gene (Fig. 5B, Left).

Figure 5.

M78 is an early gene. (A) Schematic representation of the MCMV M78 genomic region. TATA and polyadenylation motifs are indicated. Open reading frames are designated by thick arrows, and presumptive M78-encoding mRNAs (2.0- and 4.6-kb predicted sizes) are represented by thin arrows. (B) M78 is an early gene. 10.1 cells were mock- or wild-type (WT) virus-infected at a multiplicity of 3 pfu/cell. Beginning 1 h before infection and continuing until cells were harvested, cultures were treated with 30 μg/ml cycloheximide (C) to identify immediate-early mRNAs, which are made in the absence of protein synthesis, or 200 μg/ml phosphonoacetic acid (P) to block DNA replication and identify early genes, which are made in the absence of DNA replication but not in the absence of protein synthesis, or no drug to identify late mRNAs, which are not made in the presence of either drug. Cells were harvested at the indicated times (hpi) and subjected to Northern blot analysis by using an M78-specific probe or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G) probe (Left). Cells infected (WT, SMsubM78, or SMrevM78) without drug treatment and harvested at 6 hpi also were assayed by Northern blot by using an M77- and M78-specific probes (Right). The apparent sizes of RNA species are indicated. (C) M78 protein expression. 10.1 cells were mock-, wild-type (WT)-, or SMsubM78-infected at a multiplicity of 3 pfu/cell; cell lysates were prepared at indicated times postinfection (hpi) and analyzed by Western blot by using an M78-specific antibody (C-M78/2). The positions at which marker proteins migrated are indicated (kDa), and M78 bands are identified.

Two bands were recognized by M78-specific polyclonal antibody when Western blots were performed (Fig. 5C). The bands were judged to be M78 specific because they were not detected in extracts of mock- or SMsubM78-infected cells. The faster migrating band migrated at a position consistent with the protein's molecular weight. The more slowly migrating species is either posttranslationally modified M78, an aggregate of M78, or a protein with M78 sequences fused to another ORF. Accumulation of M78 protein reached a peak at about 6–8 h and then decreased until 24 h postinfection (Fig. 5C), consistent with the assignment of its mRNA to the early class of viral transcripts.

M78 is an early viral gene, the m123 immediate-early mRNA is expressed inefficiently in SMsubM78-infected cells, and the M78 dependence is evident in the absence of protein synthesis. Consequently, virion-associated M78 must facilitate the accumulation of immediate-early mRNA. Newly synthesized M78 might contribute to further activation of MCMV mRNA accumulation as the infection proceeds into the early phase.

Discussion

M78 is present in MCMV particles at a level of about 2,000 molecules per infectious unit (Fig. 3 B, D, and E). Another GCR homologue, UL33, has been detected in human cytomegalovirus particles (20). M78 protein synthesized from the genome during the early phase of the infection accumulates primarily in a perinuclear region, within or very near the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 3A), and this localization likely positions it to be incorporated into the virus particle. We did not observe M78 on the cell surface by immunofluorescence during the early phase of infection. However, the human herpesvirus-6 M78 homologue, U51, has been observed on the surface of infected cells (21), so it is possible that a small amount of newly synthesized M78 protein accumulates and functions at the cell surface.

We generated a derivative of MCMV, SMsubM78, lacking the M78 coding region (Fig. 1). The mutant replicates inefficiently when used to infect cultured cells at a relatively low input multiplicity, and it exhibits reduced pathogenicity in mice (Fig. 2). The rat cytomegalovirus M78 homologue, which is termed R78, also has been shown to grow poorly in cultured cells and to be less pathogenic than wild-type virus (22). SMsubM78 fails to efficiently activate viral mRNA accumulation in IC21 macrophage cells (Fig. 4), where its growth is most severely restricted (Fig. 2A). Because M78 is an early gene (Fig. 5) and we observe an effect of M78 on an earlier class of gene (i.e., the immediate-early m123 gene) (Fig. 4 A and B), virion-associated M78 must mediate the effect. Indeed, wild-type virus induces immediate-early mRNA accumulation more efficiently than SMsubM78 in the presence of cycloheximide (Fig. 4C), arguing the M78-mediated effect does not require protein synthesis within the newly infected cell.

Presumably, virion-associated M78 is delivered to the plasma membrane of the newly infected cell and generates a signal that favors immediate-early mRNA accumulation. Proteinase treatment of virions indicates that the C terminus of M78 is on the inner side of the virion envelope, facing the tegument (Fig. 3C). Consequently, the M78 protein will be transferred in the proper orientation for a GCR to the plasma membrane of the newly infected cell. As yet, we do not know the nature of the signal that is transmitted. Perhaps it serves to stimulate transcription or acts posttranscriptionally to influence mRNA stability. The M78 human herpesvirus-6 homologue, U51, has been shown to inhibit transcription of the cellular RANTES gene (23), so it is possible that M78 initiates a signal that modulates transcriptional regulatory systems, repressing some genes (e.g., RANTES) and activating others (e.g., the m123 immediate-early gene). Alternatively, M78 could influence any step of the viral infection before the synthesis of immediate-early mRNA.

M78 is the first cytomegalovirus GCR homologue shown to influence the accumulation of viral mRNAs. The other cytomegalovirus GCR to be assigned functions is US28, which is encoded by human cytomegalovirus. US28 responds to RANTES and other β-chemokines by inducing a calcium flux (24, 25), whose immediate consequence is unknown. US28 also mediates the internalization of RANTES and other β-chemokines (26–28), and this has been hypothesized to enable the virus to control the extracellular β-chemokine environment of infected cells. Finally, US28 has been shown to induce smooth muscle cells to migrate, an activity that is consistent with the possible role of cytomegalovirus as a cofactor in vascular disease (29).

M78 has not yet been proven to function as a GCR, but its sequence characteristics are consistent with such a role. Cells expressing the human herpesvirus-6 M78 homologue, U51, bind RANTES and compete for the binding of other β-chemokines (23). Obviously, these are attractive candidates for the ligands that bind M78 and thereby facilitate MCMV immediate-early mRNA accumulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Enquist and B. Wing for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank S. Park for assistance with studies of Rag2/γc mice, J. Goodhouse for help with confocal microscopy, A. Levine for 10.1 cells, E. Mocarski for MCMV strain K181+, and K. Moremen (University of Georgia) for Mannosidase II-specific antibody. This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grants CA82396 and CA85786. S.A.O. was supported by a Ph.D. fellowship (BD/13342/97), granted by PRAXIS XXI through Programa Gulbenkian de Doutoramento em Biologia e Medicina.

Abbreviations

- GCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- MCMV

murine cytomegalovirus

References

- 1.Chee M S, Bankier A T, Beck S, Bohni R, Brown C M, Cerny R, Horsnell T, Hutchison C A, III, Kouzarides T, Martignetti J A, et al. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;154:125–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawlinson W D, Farrell H E, Barrell B G. J Virol. 1996;70:8833–8849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8833-8849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vink C, Beuken E, Bruggeman C A. J Virol. 2000;74:7656–7665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7656-7665.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gompels U A, Nicholas J, Lawrence G, Jones M, Thomson B J, Martin M E, Efstathiou S, Craxton M, Macaulay H A. Virology. 1995;209:29–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholas J. J Virol. 1996;70:5975–5989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5975-5989.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Probst W C, Snyder L A, Schuster D I, Brosius J, Sealfon S C. DNA Cell Biol. 1992;11:1–20. doi: 10.1089/dna.1992.11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser C M, Chung F Z, Wang C D, Venter J C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5478–5482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C D, Buck M A, Fraser C M. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:168–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hargrave P A, McDowell J H, Siemiatkowski J E C, Fong S L, Kuhn H, Wang J K, Curtis D R, Mohana R J K, Argos P, Feldmann R J. Vision Res. 1982;22:1429–1438. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark R B, Friedman J, Dixon R A, Strader C D. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith M G. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1954;86:435–440. doi: 10.3181/00379727-86-21123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey D M, Levine A J. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2375–2385. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tullis G E, Shenk T. J Virol. 2000;74:11511–11521. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11511-11521.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moremen K W, Touster O. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6654–6662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanson L K, Slater J S, Karabekian Z, Virgin H W IV, Biron C A, Ruzek M C, Van Rooijen N, Ciavarra R P, Stenberg R M, Campbell A E. J Virol. 1999;73:5970–5980. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5970-5980.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao X, Shores E W, Hu-Li J, Anver M R, Kelsall B L, Russell S M, Drago J, Noguchi M, Grinberg A, Bloom E T, et al. Immunity. 1995;2:223–238. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam K P, Oltz E M, Stewart V, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall A M, Alt F W. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez V, Greis K D, Sztul E, Britt W J. J Virol. 2000;74:975–986. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.975-986.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurz S, Steffens H P, Mayer A, Harris J R, Reddehase M J. J Virol. 1997;71:2980–2987. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2980-2987.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Margulies B J, Browne H, Gibson W. Virology. 1996;225:111–125. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menotti L, Mirandola P, Locati M, Campadelli-Fiume G. J Virol. 1999;73:325–333. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.325-333.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beisser P S, Grauls G, Bruggeman C A, Vink C. J Virol. 1999;73:7218–7230. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7218-7230.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milne R S, Mattick C, Nicholson L, Devaraj P, Alcami A, Gompels U A. J Immunol. 2000;164:2396–2404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao J L, Murphy P M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28539–28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billstrom M A, Johnson G L, Avdi N J, Worthen G S. J Virol. 1998;72:5535–5544. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5535-5544.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michelson S, Dal Monte P, Zipeto D, Bodaghi B, Laurent L, Oberlin E, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier J L, Landini M P. J Virol. 1997;71:6495–6500. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6495-6500.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodaghi B, Jones T R, Zipeto D, Vita C, Sun L, Laurent L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier J L, Michelson S. J Exp Med. 1998;188:855–866. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Billstrom M A, Lehman L A, Scott Worthen G. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:163–167. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.2.3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streblow D N, Soderberg-Naucler C, Vieira J, Smith P, Wakabayashi E, Ruchti F, Mattison K, Altschuler Y, Nelson J A. Cell. 1999;99:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]